Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. A Brief Overview of Pediatric MASLD Pathophysiology

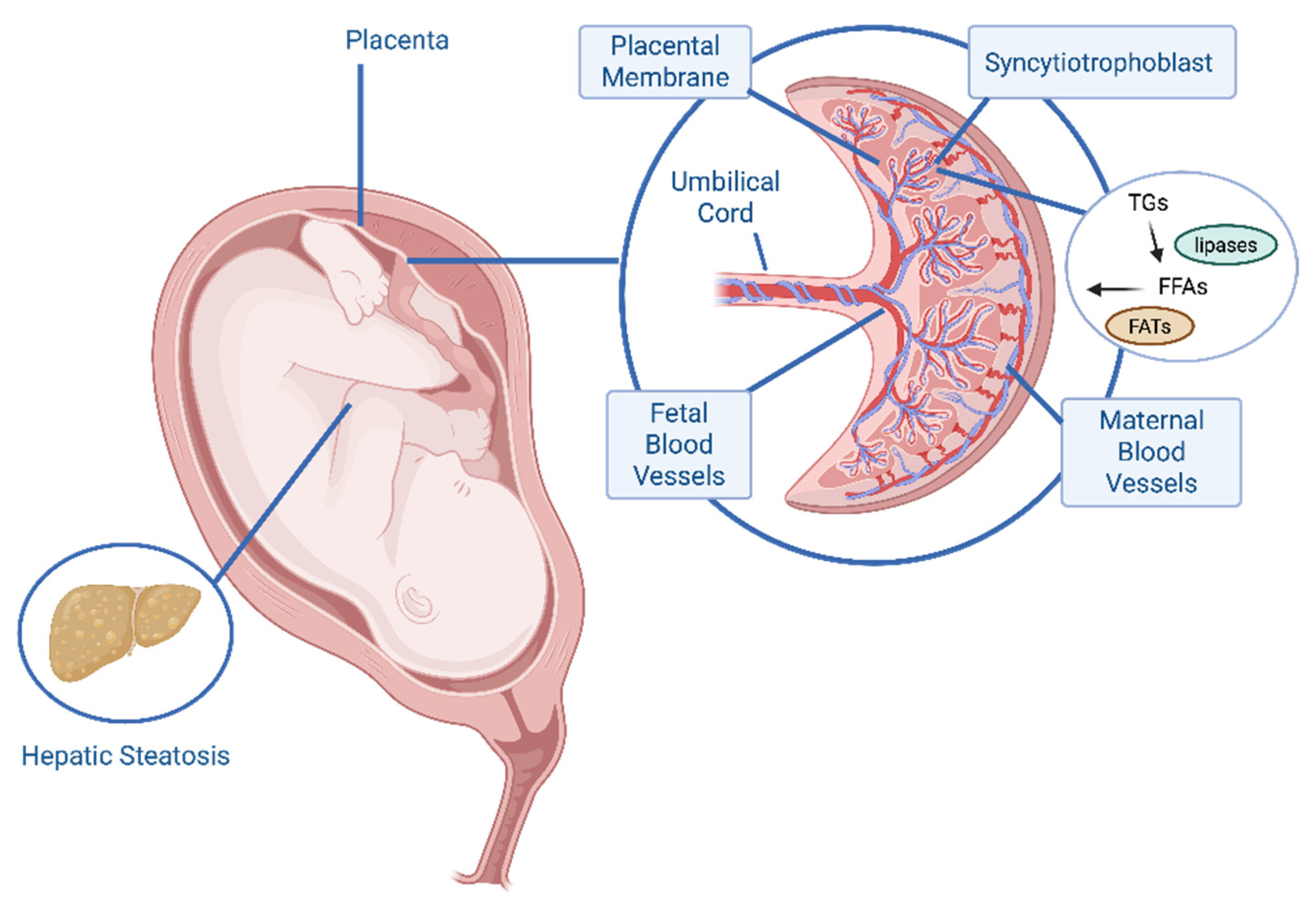

4. Maternal Nutrition and Offspring Hepatic Steatosis

4.1. Connecting Human Observational Findings and Mechanisms

4.2. Insights from Animal Models

4.3. Macronutrient Composition and Hepatic Steatosis Risk

4.4. Modifiability

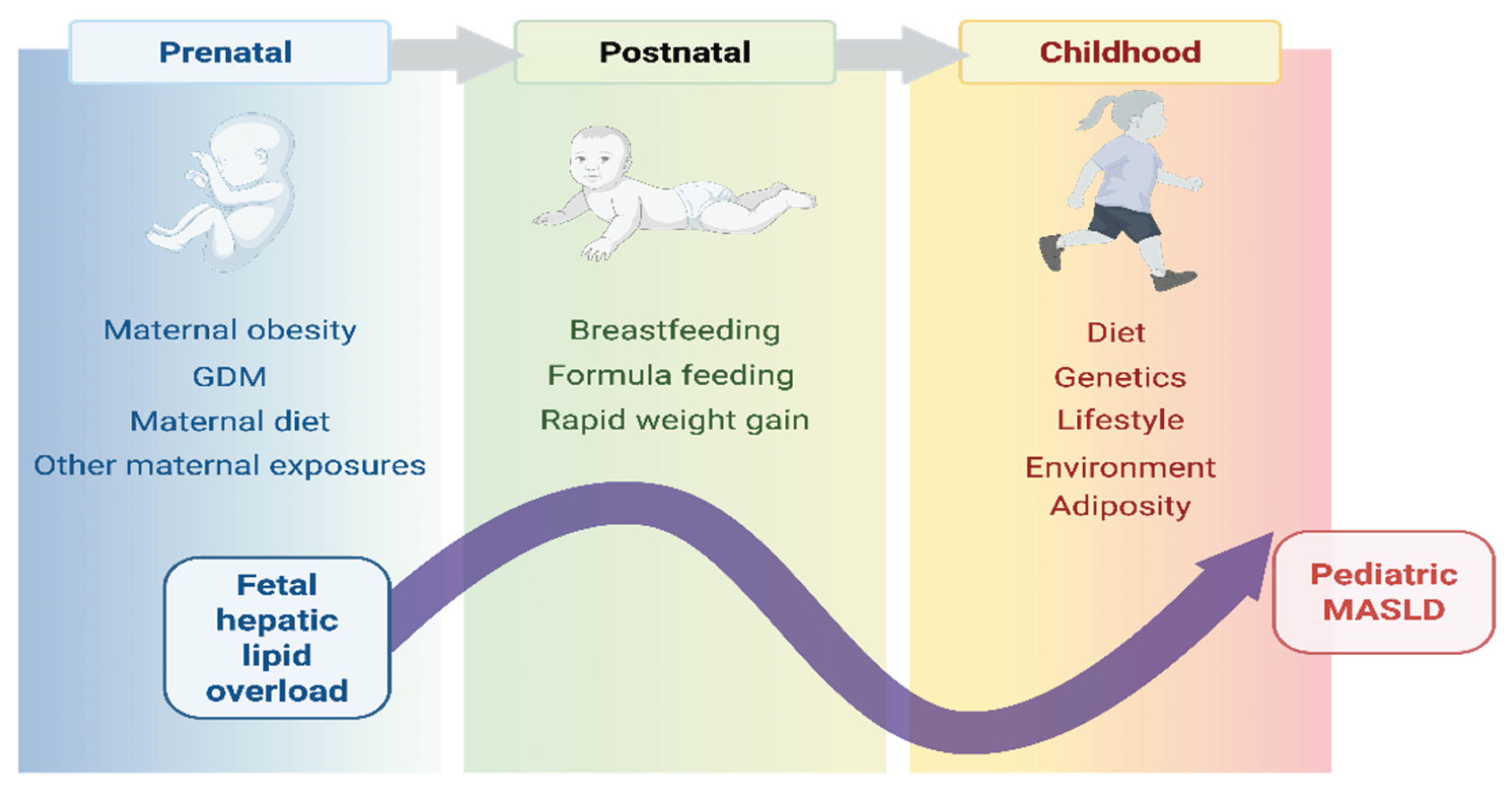

4.5. The DOHaD Framework

5. Early Childhood Nutrition and Liver Fat Accretion

5.1. Postnatal and Infant Dietary Factors

5.2. Childhood and Early Adolescent Dietary Influences

6. Conclusions

6.1. Conclusions: A Life Course Developmental Continuum

6.2. Methodological Limitations and Future Directions

6.3. Opportunities for Prevention and Intervention

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC2 | acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2 |

| ALSPAC | Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| aOR | adjusted odds ratio |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CD36 | cluster of differentiation 36 |

| CI | confidence interval |

| DAMPs | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DII | Dietary Inflammatory Index |

| EPOCH | Exploring Perinatal Outcomes Among Children |

| ESPRESSO | Epidemiology Strengthened by Histopathology Reports in Sweden |

| FABP | fatty acid binding protein |

| FATP | fatty acid transport protein |

| FATs | fatty acid transporters |

| FFAs | free fatty acids |

| FIB-4 | fibrosis-4 index |

| GCKR | glucokinase regulatory protein |

| GDM | gestational diabetes mellitus |

| IHCL | intra-hepatocellular lipid |

| MAFLD | metabolic associated fatty liver disease |

| MASH | metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| MASLD | metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MRS | magnetic resonance spectroscopy |

| NAFLD | nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NASH | nonalcoholic steatohepatitis |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| OR | odds ratio |

| PNPLA3 | patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 |

| SPCS | Shanghai Prenatal Cohort Study |

| SREBP-1c | sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c |

| TGs | triglycerides |

| TM6SF2 | transmembrane 6 superfamily 2 |

| TLF4 | toll-like receptor 4 |

| VLDL | very low-density lipoprotein |

References

- Jia, S.; Ye, X.; Wu, T.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J. Global prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease in children and adolescents with overweight and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterology 2025, 25, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Kalligeros, M.; Henry, L. Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2025, 31, S32–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P. , et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Allen, A.M.; Wang, Z.; Prokop, L.J.; Murad, M.H.; Loomba, R. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015, 13. 643-654 e641-649; quiz e639-640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draijer, L.; Voorhoeve, M.; Troelstra, M.; Holleboom, A.; Beuers, U.; Kusters, M.; Nederveen, A.; Benninga, M.; Koot, B. A natural history study of paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease over 10 years. JHEP Rep 2023, 5, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, V.P.V.; Mouzaki, M.; Xanthakos, S.A.; Zhang, B.; Tkach, J.A.; Ouyang, J.; Dillman, J.R.; Trout, A.T. Longitudinal evaluation of pediatric and young adult metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease defined by MR elastography. Eur Radiol 2025, 35, 2474–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthakos, S.A.; Lavine, J.E.; Yates, K.P.; Schwimmer, J.B.; Molleston, J.P.; Rosenthal, P.; Murray, K.F.; Vos, M.B.; Jain, A.K.; Scheimann, A.O. , et al. Progression of Fatty Liver Disease in Children Receiving Standard of Care Lifestyle Advice. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1731–1751.e1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwimmer, J.B.; Biddinger, S.B.; Ibrahim, S.H. MASLD in children: integrating epidemiological trends with mechanistic and translational advances. J Clin Invest 2025, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, A.E.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P.; Treeprasertsuk, S.; Benson, J.T.; Enders, F.B.; Angulo, P. The natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: a follow-up study for up to 20 years. Gut 2009, 58, 1538–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwimmer, J.B.; Thai, N.Q.N.; Noon, S.L.; Ugalde-Nicalo, P.; Anderson, S.R.; Chun, L.F.; David, R.S.; Goyal, N.P.; Newton, K.P.; Hansen, E.G. , et al. Long-term mortality and extrahepatic outcomes in 1096 children with MASLD: A retrospective cohort study. Hepatology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, T.G.; Roelstraete, B.; Hartjes, K.; Shah, U.; Khalili, H.; Arnell, H.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children and young adults is associated with increased long-term mortality. J Hepatol 2021, 75, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, P.; Mouzaki, M.; Hassan, S.; Kehar, M.; Mysore, K.R.; Mauney, E.; Nonga, D.; Karjoo, S.; Sood, S.; Tou, A. , et al. Call to action-Pediatric MASLD requires immediate attention to curb health crisis. Hepatology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Africa, J.A.; Behling, C.A.; Brunt, E.M.; Zhang, N.; Luo, Y.; Wells, A.; Hou, J.; Belt, P.H.; Kohil, R.; Lavine, J.E. , et al. In Children With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Zone 1 Steatosis Is Associated With Advanced Fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018, 16, 438–446.e431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwimmer, J.B.; Behling, C.; Newbury, R.; Deutsch, R.; Nievergelt, C.; Schork, N.J.; Lavine, J.E. Histopathology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 42, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahota, A.K.; Shapiro, W.L.; Newton, K.P.; Kim, S.T.; Chung, J.; Schwimmer, J.B. Incidence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: 2009-2018. Pediatrics 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, E.L.; Schwimmer, J.B. Epidemiology of Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2021, 17, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumpail, B.J.; Manikat, R.; Wijarnpreecha, K.; Cholankeril, G.; Ahmed, A.; Kim, D. The prevalence and predictors of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and fibrosis/cirrhosis among adolescents/young adults. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2024, 79, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.X.; Qian, Y.S.; Jiang, C.M.; Liu, Z.Z.; Yang, X.; Xu, Y.W.; Jin, S.S.; Chu, J.G.; Qian, G.Q.; Yang, N.B. Prevalence of steatotic liver disease (MASLD, MetALD, ALD) and clinically significant fibrosis in US adolescents : Authors’ name. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 25724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, T.; Paik, J.M.; Biswas, R.; Alqahtani, S.A.; Henry, L.; Younossi, Z.M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Prevalence Trends Among Adolescents and Young Adults in the United States, 2007-2016. Hepatol Commun 2021, 5, 1676–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.L.; Golshan, S.; Harlow, K.E.; Angeles, J.E.; Durelle, J.; Goyal, N.P.; Newton, K.P.; Sawh, M.C.; Hooker, J.; Sy, E.Z. , et al. Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children with Obesity. J Pediatr 2019, 207, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mischel, A.K.; Liao, Z.; Cao, F.; Dunn, W.; Lo, J.C.; Newton, K.P.; Goyal, N.P.; Yu, E.L.; Schwimmer, J.B. Prevalence of Elevated ALT in Adolescents in the US 2011-2018. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2023, 77, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, J.K.; Gerhard, G.S. NAFLD in normal weight individuals. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2022, 14, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cheung, R. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Children: Where Are We? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 20, 2210–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, F.; Hagstrom, H.; Sun, J.; Bergman, D.; Shang, Y.; Yang, W.; Roelstraete, B.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Familial coaggregation of MASLD with hepatocellular carcinoma and adverse liver outcomes: Nationwide multigenerational cohort study. J Hepatol 2023, 79, 1374–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chang, K.M.; Yu, J.; Loomba, R. Unraveling Mechanisms of Genetic Risks in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Diseases: A Pathway to Precision Medicine. Annu Rev Pathol 2025, 20, 375–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Costanzo, A.; Pacifico, L.; Chiesa, C.; Perla, F.M.; Ceci, F.; Angeloni, A.; D’Erasmo, L.; Di Martino, M.; Arca, M. Genetic and metabolic predictors of hepatic fat content in a cohort of Italian children with obesity. Pediatr Res 2019, 85, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zusi, C.; Mantovani, A.; Olivieri, F.; Morandi, A.; Corradi, M.; Miraglia Del Giudice, E.; Dauriz, M.; Valenti, L.; Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. , et al. Contribution of a genetic risk score to clinical prediction of hepatic steatosis in obese children and adolescents. Dig Liver Dis 2019, 51, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudert, C.A.; Selinski, S.; Rudolph, B.; Blaker, H.; Loddenkemper, C.; Thielhorn, R.; Berndt, N.; Golka, K.; Cadenas, C.; Reinders, J. , et al. Genetic determinants of steatosis and fibrosis progression in paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int 2019, 39, 540–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccio, S.; Melone, R.; Vitulano, C.; Guida, P.; Maddaluno, I.; Guarino, S.; Marzuillo, P.; Miraglia Del Giudice, E.; Di Sessa, A. Advances in pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: From genetics to lipidomics. World J Clin Pediatr 2022, 11, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faienza, M.F.; Baima, J.; Cecere, V.; Monteduro, M.; Farella, I.; Vitale, R.; Antoniotti, V.; Urbano, F.; Tini, S.; Lenzi, F.R. , et al. Fructose Intake and Unhealthy Eating Habits Are Associated with MASLD in Pediatric Obesity: A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. Nutrients 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.Y.; Lim, J.H.; Joung, H.; Yoon, D. Association Between Ultraprocessed Food Consumption and Metabolic Disorders in Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nier, A.; Brandt, A.; Conzelmann, I.B.; Ozel, Y.; Bergheim, I. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Overweight Children: Role of Fructose Intake and Dietary Pattern. Nutrients 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.C.; Li, K.W.; Alazraki, A.L.; Beysen, C.; Carrier, C.A.; Cleeton, R.L.; Dandan, M.; Figueroa, J.; Knight-Scott, J.; Knott, C.J. , et al. Dietary sugar restriction reduces hepatic de novo lipogenesis in adolescent boys with fatty liver disease. J Clin Invest 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.F.; Varady, K.A.; Wang, X.D.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tayyem, R.; Latella, G.; Bergheim, I.; Valenzuela, R.; George, J. , et al. The role of dietary modification in the prevention and management of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international multidisciplinary expert consensus. Metabolism 2024, 161, 156028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mager, D.R.; Patterson, C.; So, S.; Rogenstein, C.D.; Wykes, L.J.; Roberts, E.A. Dietary and physical activity patterns in children with fatty liver. Eur J Clin Nutr 2010, 64, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandel, P.; Ma, L.; Wang, H.; Pasman, E.A. You Are What You Eat: A Review on Dietary Interventions for Treating Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, A.; Chivese, T.; Elshaikh, U.; Sendall, M. Efficacy of the Mediterranean diet in treating metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, M.; Arenaza, L.; Migueles, J.H.; Rodriguez-Vigil, B.; Ruiz, J.R.; Labayen, I. Associations of physical activity and fitness with hepatic steatosis, liver enzymes, and insulin resistance in children with overweight/obesity. Pediatr Diabetes 2020, 21, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jin, S.; Fang, P.; Pan, C.; Huang, S. Association between excessive screen time and steatotic liver disease in adolescents: Findings from the 2017-2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Pediatr Obes 2025, 20, e70010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Li, L.; Cheng, L.; Gu, Z.; Hong, Y. Maternal obesity and offspring metabolism: revisiting dietary interventions. Food Funct 2025, 16, 3751–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzaki, M.; Woo, J.G.; Divanovic, S. Gestational and Developmental Contributors of Pediatric MASLD. Semin Liver Dis 2024, 44, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, N.; Yki-Jarvinen, H.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: heterogeneous pathomechanisms and effectiveness of metabolism-based treatment. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2025, 13, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabl, B.; Damman, C.J.; Carr, R.M. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and the gut microbiome: pathogenic insights and therapeutic innovations. J Clin Invest 2025, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturbe-Rey, S.; Maccali, C.; Arrese, M.; Aspichueta, P.; Oliveira, C.P.; Castro, R.E.; Lapitz, A.; Izquierdo-Sanchez, L.; Bujanda, L.; Perugorria, M.J. , et al. Lipotoxicity-driven metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Atherosclerosis 2025, 400, 119053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.H. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: molecular mechanisms for the hepatic steatosis. Clin Mol Hepatol 2013, 19, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunny, N.E.; Bril, F.; Cusi, K. Mitochondrial Adaptation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Novel Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2017, 28, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brankovic, M.; Jovanovic, I.; Dukic, M.; Radonjic, T.; Opric, S.; Klasnja, S.; Zdravkovic, M. Lipotoxicity as the Leading Cause of Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krahmer, N.; Walther, T.C.; Farese, R.V., Jr. The pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis in MASLD: a lipid droplet perspective. J Clin Invest 2025, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomba, R.; Friedman, S.L.; Shulman, G.I. Mechanisms and disease consequences of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell 2021, 184, 2537–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R. DAMPs and DAMP-sensing receptors in inflammation and diseases. Immunity 2024, 57, 752–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, E.; Schwabe, R.F. Hepatic inflammation and fibrosis: functional links and key pathways. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, N.; Murgasova, D.; Ruager-Martin, R.; Thomas, E.L.; Hyde, M.J.; Gale, C.; Santhakumaran, S.; Dore, C.J.; Alavi, A.; Bell, J.D. The influence of maternal body mass index on infant adiposity and hepatic lipid content. Pediatr Res 2011, 70, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumbaugh, D.E.; Tearse, P.; Cree-Green, M.; Fenton, L.Z.; Brown, M.; Scherzinger, A.; Reynolds, R.; Alston, M.; Hoffman, C.; Pan, Z. , et al. Intrahepatic fat is increased in the neonatal offspring of obese women with gestational diabetes. J Pediatr 2013, 162, 930–936.e931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayonrinde, O.T.; Oddy, W.H.; Adams, L.A.; Mori, T.A.; Beilin, L.J.; de Klerk, N.; Olynyk, J.K. Infant nutrition and maternal obesity influence the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adolescents. J Hepatol 2017, 67, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Lawlor, D.A.; Callaway, M.; Macdonald-Wallis, C.; Sattar, N.; Fraser, A. Association of maternal diabetes/glycosuria and pre-pregnancy body mass index with offspring indicators of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Pediatr 2016, 16, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekkarie, A.; Welsh, J.A.; Northstone, K.; Stein, A.D.; Ramakrishnan, U.; Vos, M.B. Associations of maternal diet and nutritional status with offspring hepatic steatosis in the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. BMC Nutr 2021, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagstrom, H.; Simon, T.G.; Roelstraete, B.; Stephansson, O.; Soderling, J.; Ludvigsson, J.F. Maternal obesity increases the risk and severity of NAFLD in offspring. J Hepatol 2021, 75, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Shen, F.; Zou, Z.Y.; Yang, R.X.; Jin, Q.; Yang, J.; Chen, G.Y.; Fan, J.G. Association of maternal obesity and gestational diabetes mellitus with overweight/obesity and fatty liver risk in offspring. World J Gastroenterol 2022, 28, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.C.; Perng, W.; Sauder, K.A.; Shapiro, A.L.B.; Starling, A.P.; Friedman, C.; Felix, J.F.; Kupers, L.K.; Moore, B.F.; Hebert, J.R. , et al. Maternal Diet Quality During Pregnancy and Offspring Hepatic Fat in Early Childhood: The Healthy Start Study. J Nutr 2023, 153, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.R.; White, F.V.; Deutsch, G.H. Hepatic steatosis is prevalent in stillborns delivered to women with diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015, 60, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, L.A.; Hernandez, T.L. Maternal Lipids and Fetal Overgrowth: Making Fat from Fat. Clin Ther 2018, 40, 1638–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easton, Z.J.W.; Regnault, T.R.H. The Impact of Maternal Body Composition and Dietary Fat Consumption upon Placental Lipid Processing and Offspring Metabolic Health. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.F.; Harrall, K.K.; Sauder, K.A.; Glueck, D.H.; Dabelea, D. Neonatal Adiposity and Childhood Obesity. Pediatrics 2020, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amati, F.; McCann, L.; Castaneda-Gutierrez, E.; Prior, E.; van Loo-Bouwman, C.A.; Abrahamse-Berkeveld, M.; Oliveros, E.; Ozanne, S.; Symonds, M.E.; Chang, C.Y. , et al. Infant fat mass and later child and adolescent health outcomes: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child 2024, 109, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, N.; Salas-Perez, F.; Ortiz, M.; Alvarez, D.; Echiburu, B.; Maliqueo, M. Rodent models in placental research. Implications for fetal origins of adult disease. Anim Reprod 2022, 19, e20210134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sloboda, D.M.; Vickers, M.H. Maternal obesity and developmental programming of metabolic disorders in offspring: evidence from animal models. Exp Diabetes Res 2011, 2011, 592408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, D.; Tejero, M.E.; Comuzzie, A.G.; Higgins, P.B.; Cox, L.; Werner, S.L.; Jenkins, S.L.; Li, C.; Choi, J.; Dick, E.J., Jr. , et al. Feto-placental adaptations to maternal obesity in the baboon. Placenta 2009, 30, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, A.M. Animal models of human pregnancy and placentation: alternatives to the mouse. Reproduction 2020, 160, R129–R143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzetta, C.A.; Rudel, L.L. A species comparison of low density lipoprotein heterogeneity in nonhuman primates fed atherogenic diets. J Lipid Res 1986, 27, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCurdy, C.E.; Bishop, J.M.; Williams, S.M.; Grayson, B.E.; Smith, M.S.; Friedman, J.E.; Grove, K.L. Maternal high-fat diet triggers lipotoxicity in the fetal livers of nonhuman primates. J Clin Invest 2009, 119, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppala, S.; Li, C.; Glenn, J.P.; Saxena, R.; Gawrieh, S.; Quinn, A.; Palarczyk, J.; Dick, E.J., Jr.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Cox, L.A. Primate fetal hepatic responses to maternal obesity: epigenetic signalling pathways and lipid accumulation. J Physiol 2018, 596, 5823–5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, S.R.; Baquero, K.C.; Newsom, S.A.; El Kasmi, K.C.; Bergman, B.C.; Shulman, G.I.; Grove, K.L.; Friedman, J.E. Early life exposure to maternal insulin resistance has persistent effects on hepatic NAFLD in juvenile nonhuman primates. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2702–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, M.J.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Al-Juboori, S.I.; Janssen, R.C.; Fernandes, J.; Argabright, A.; D’Alessandro, A.; Kirigiti, M.A.; Kievit, P.; Aagaard, K.M. , et al. Maternal Western Diet Programmes Bile Acid Dysregulation and Hepatic Fibrosis in Fetal and Juvenile Macaques. Liver Int 2025, 45, e16236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, M.J.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Janssen, R.C.; Lovell, M.A.; Schady, D.A.; Levek, C.; Jones, K.L.; D’Alessandro, A.; Kievit, P.; Aagaard, K.M. , et al. Maternal Western diet is associated with distinct preclinical pediatric NAFLD phenotypes in juvenile nonhuman primate offspring. Hepatol Commun 2023, 7, e0014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesolowski, S.R.; Mulligan, C.M.; Janssen, R.C.; Baker, P.R., 2nd; Bergman, B.C.; D’Alessandro, A.; Nemkov, T.; Maclean, K.N.; Jiang, H.; Dean, T.A. , et al. Switching obese mothers to a healthy diet improves fetal hypoxemia, hepatic metabolites, and lipotoxicity in non-human primates. Mol Metab 2018, 18, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ye, T.; Liu, C.; Fang, F.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Y. Maternal high-fat diet during pregnancy and lactation affects hepatic lipid metabolism in early life of offspring rat. J Biosci 2017, 42, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kereliuk, S.M.; Brawerman, G.M.; Dolinsky, V.W. Maternal Macronutrient Consumption and the Developmental Origins of Metabolic Disease in the Offspring. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayol, S.A.; Simbi, B.H.; Fowkes, R.C.; Stickland, N.C. A maternal “junk food” diet in pregnancy and lactation promotes nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease in rat offspring. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjaergaard, M.; Nilsson, C.; Rosendal, A.; Nielsen, M.O.; Raun, K. Maternal chocolate and sucrose soft drink intake induces hepatic steatosis in rat offspring associated with altered lipid gene expression profile. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2014, 210, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Zeng, J.J.; Kjaergaard, M.; Guan, N.; Raun, K.; Nilsson, C.; Wang, M.W. Effects of a maternal diet supplemented with chocolate and fructose beverage during gestation and lactation on rat dams and their offspring. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2011, 38, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloboda, D.M.; Li, M.; Patel, R.; Clayton, Z.E.; Yap, C.; Vickers, M.H. Early life exposure to fructose and offspring phenotype: implications for long term metabolic homeostasis. J Obes 2014, 2014, 203474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, M.H.; Clayton, Z.E.; Yap, C.; Sloboda, D.M. Maternal fructose intake during pregnancy and lactation alters placental growth and leads to sex-specific changes in fetal and neonatal endocrine function. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 1378–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegmann, S.K.; Vohlen, C.; Im, N.G.; Niehues, J.; Selle, J.; Janoschek, R.; Kuiper-Makris, C.; Lang, S.; Demir, M.; Steffen, H.M. , et al. Perinatal obesity primes the hepatic metabolic stress response in the offspring across life span. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 6416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, L.I.; Jensen, R.I.; Waterstradt, M.S.; Quistorff, B.; Lauritzen, L. Acute and perinatal programming effects of a fat-rich diet on rat muscle mitochondrial function and hepatic lipid accumulation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014, 93, 1170–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soderborg, T.K.; Clark, S.E.; Mulligan, C.E.; Janssen, R.C.; Babcock, L.; Ir, D.; Young, B.; Krebs, N.; Lemas, D.J.; Johnson, L.K. , et al. The gut microbiota in infants of obese mothers increases inflammation and susceptibility to NAFLD. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, M.S.; Heerwagen, M.J.; Friedman, J.E. Developmental programming of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: redefining the”first hit”. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2013, 56, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfrey, K.M.; Reynolds, R.M.; Prescott, S.L.; Nyirenda, M.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Eriksson, J.G.; Broekman, B.F. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017, 5, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Vigliotti, C.; Witjes, J.; Le, P.; Holleboom, A.G.; Verheij, J.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Clement, K. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020, 17, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandala, A.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Janssen, R.C.; Fiehn, O.; D’Alessandro, A.; Friedman, J.E.; Jonscher, K.R. Maternal Pyrroloquinoline Quinone Supplementation Improves Offspring Liver Bioactive Lipid Profiles throughout the Lifespan and Protects against the Development of Adult NAFLD. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.F.; Gillingham, M.B.; Batra, A.K.; Fewkes, N.M.; Comstock, S.M.; Takahashi, D.; Braun, T.P.; Grove, K.L.; Friedman, J.E.; Marks, D.L. Maternal high fat diet is associated with decreased plasma n-3 fatty acids and fetal hepatic apoptosis in nonhuman primates. PLoS One 2011, 6, e17261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, M.J.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Newsom, S.A.; Messaoudi, I.; Janssen, R.C.; Aagaard, K.M.; McCurdy, C.E.; Gannon, M.; Kievit, P.; Friedman, J.E. , et al. Maternal Western diet exposure increases periportal fibrosis beginning in utero in nonhuman primate offspring. JCI Insight 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, D.J. Maternal nutrition, fetal nutrition, and disease in later life. Nutrition 1997, 13, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.J. The origins of the developmental origins theory. J Intern Med 2007, 261, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querter, I.; Pauwels, N.S.; De Bruyne, R.; Dupont, E.; Verhelst, X.; Devisscher, L.; Van Vlierberghe, H.; Geerts, A.; Lefere, S. Maternal and Perinatal Risk Factors for Pediatric Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 20, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobili, V.; Bedogni, G.; Alisi, A.; Pietrobattista, A.; Alterio, A.; Tiribelli, C.; Agostoni, C. A protective effect of breastfeeding on the progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Arch Dis Child 2009, 94, 801–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelezang, S.; Santos, S.; van der Beek, E.M.; Abrahamse-Berkeveld, M.; Duijts, L.; van der Lugt, A.; Felix, J.F.; Jaddoe, V.W.V. Infant breastfeeding and childhood general, visceral, liver, and pericardial fat measures assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Clin Nutr 2018, 108, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, C.; Thomas, E.L.; Jeffries, S.; Durighel, G.; Logan, K.M.; Parkinson, J.R.; Uthaya, S.; Santhakumaran, S.; Bell, J.D.; Modi, N. Adiposity and hepatic lipid in healthy full-term, breastfed, and formula-fed human infants: a prospective short-term longitudinal cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 2014, 99, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purkiewicz, A.; Pietrzak-Fiecko, R. Determination of the Fatty Acid Profile and Lipid Quality Indices in Selected Infant Formulas. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrard, S.D.; Yonke, J.A.; Seymour, K.A.; Sunny, N.E.; El-Kadi, S.W. Feeding medium-chain fatty acid-rich formula causes liver steatosis and alters hepatic metabolism in neonatal pigs. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2023, 325, G135–G146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurtsen, M.L.; Santos, S.; Gaillard, R.; Felix, J.F.; Jaddoe, V.W.V. Associations Between Intake of Sugar-Containing Beverages in Infancy With Liver Fat Accumulation at School Age. Hepatology 2021, 73, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler Mis, N.; Braegger, C.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; Domellof, M.; Embleton, N.D.; Hojsak, I.; Hulst, J.; Indrio, F.; Lapillonne, A. , et al. Sugar in Infants, Children and Adolescents: A Position Paper of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017, 65, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rips-Goodwin AR, J.D. , Griebel-Thompson A, Kang KL, Fazzino TL. US infant formulas contain primarily added sugars: An analysis of infant formulas on the US market. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2025, 141, 107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J.; Russell, C.G.; Laws, R.; Fowler, C.; Campbell, K.; Denney-Wilson, E. Infant formula feeding practices associated with rapid weight gain: A systematic review. Matern Child Nutr 2018, 14, e12602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisaka, O.; Ichikawa, G.; Koyama, S.; Sairenchi, T. Childhood obesity: rapid weight gain in early childhood and subsequent cardiometabolic risk. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol 2020, 29, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breij, L.M.; Kerkhof, G.F.; Hokken-Koelega, A.C. Accelerated infant weight gain and risk for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in early adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014, 99, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiStefano, J.K.; Shaibi, G.Q. The relationship between excessive dietary fructose consumption and paediatric fatty liver disease. Pediatr Obes 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Softic, S.; Gupta, M.K.; Wang, G.X.; Fujisaka, S.; O’Neill, B.T.; Rao, T.N.; Willoughby, J.; Harbison, C.; Fitzgerald, K.; Ilkayeva, O. , et al. Divergent effects of glucose and fructose on hepatic lipogenesis and insulin signaling. J Clin Invest 2017, 127, 4059–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distefano, J.K.; Gerhard, G.S. Effects of dietary sugar restriction on hepatic fat in youth with obesity. Minerva Pediatr (Torino) 2024, 76, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, J.M.; Noworolski, S.M.; Erkin-Cakmak, A.; Korn, N.J.; Wen, M.J.; Tai, V.W.; Jones, G.M.; Palii, S.P.; Velasco-Alin, M.; Pan, K. , et al. Effects of Dietary Fructose Restriction on Liver Fat, De Novo Lipogenesis, and Insulin Kinetics in Children With Obesity. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.C.; Perng, W.; Sauder, K.A.; Ringham, B.M.; Bellatorre, A.; Scherzinger, A.; Stanislawski, M.A.; Lange, L.A.; Shankar, K.; Dabelea, D. Associations of Nutrient Intake Changes During Childhood with Adolescent Hepatic Fat: The Exploring Perinatal Outcomes Among CHildren Study. J Pediatr 2021, 237, 50–58.e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, D.; Rousso, I.; Malindretos, P.; Makedou, A.; Moudiou, T.; Pidonia, I.; Pantoleon, A.; Economou, I.; Mavromichalis, I. Are saturated fatty acids and insulin resistance associated with fatty liver in obese children? Clin Nutr 2008, 27, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papandreou, D.; Karabouta, Z.; Pantoleon, A.; Rousso, I. Investigation of anthropometric, biochemical and dietary parameters of obese children with and without non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Appetite 2012, 59, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenaza, L.; Medrano, M.; Oses, M.; Huybrechts, I.; Diez, I.; Henriksson, H.; Labayen, I. Dietary determinants of hepatic fat content and insulin resistance in overweight/obese children: a cross-sectional analysis of the Prevention of Diabetes in Kids (PREDIKID) study. Br J Nutr 2019, 121, 1158–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.N.; Le, K.A.; Walker, R.W.; Vikman, S.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Weigensberg, M.J.; Allayee, H.; Goran, M.I. Increased hepatic fat in overweight Hispanic youth influenced by interaction between genetic variation in PNPLA3 and high dietary carbohydrate and sugar consumption. Am J Clin Nutr 2010, 92, 1522–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, P.S.; Lang, S.; Gilbert, M.; Kamat, D.; Bansal, S.; Ford-Adams, M.E.; Desai, A.P.; Dhawan, A.; Fitzpatrick, E.; Moore, J.B. , et al. Assessment of Diet and Physical Activity in Paediatric Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Patients: A United Kingdom Case Control Study. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9721–9733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.L.; Howe, L.D.; Fraser, A.; Macdonald-Wallis, C.; Callaway, M.P.; Sattar, N.; Day, C.; Tilling, K.; Lawlor, D.A. Childhood energy intake is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adolescents. J Nutr 2015, 145, 983–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perng, W.; Harte, R.; Ringham, B.M.; Baylin, A.; Bellatorre, A.; Scherzinger, A.; Goran, M.I.; Dabelea, D. A Prudent dietary pattern is inversely associated with liver fat content among multi-ethnic youth. Pediatr Obes 2021, 16, e12758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, F.; Moludi, J.; Jouybari, T.A.; Ghasemi, M.; Sharifi, M.; Mahaki, B.; Soleimani, D. Relationship between dietary inflammatory index and metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease in children. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, U.E.; Isik, I.A.; Atalay, A.; Eraslan, A.; Durmus, E.; Turkmen, S.; Yurttas, A.S. The effect of a Mediterranean diet vs. a low-fat diet on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: a randomized trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2022, 73, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurtdas, G.; Akbulut, G.; Baran, M.; Yilmaz, C. The effects of Mediterranean diet on hepatic steatosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation in adolescents with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Obes 2022, 17, e12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanvig, M.; Vinter, C.A.; Jorgensen, J.S.; Wehberg, S.; Ovesen, P.G.; Beck-Nielsen, H.; Christesen, H.T.; Jensen, D.M. Effects of lifestyle intervention in pregnancy and anthropometrics at birth on offspring metabolic profile at 2.8 years: results from the Lifestyle in Pregnancy and Offspring (LiPO) study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015, 100, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanvig, M.; Vinter, C.A.; Jorgensen, J.S.; Wehberg, S.; Ovesen, P.G.; Lamont, R.F.; Beck-Nielsen, H.; Christesen, H.T.; Jensen, D.M. Anthropometrics and body composition by dual energy X-ray in children of obese women: a follow-up of a randomized controlled trial (the Lifestyle in Pregnancy and Offspring [LiPO] study). PLoS One 2014, 9, e89590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cohort | Loc | n | Age | Modality | Main Findings | Ref |

| Children’s Hospital CO | USA | 25 | 1-3 wks | MRS | Greater IHCL content in neonates born to obese diabetic mothers | [53] |

| Chelsea & Westminster Hospital | UK | 105 | 11.7 d | MRS | 8.6 % IHCL increase per BMI unit | [52] |

| Raine | Aus | 1170 | 17 y | USS | Maternal obesity increases adolescent MASLD risk, breastfeeding > 6 months confers protection | [54] |

| ALSPAC | UK | 1,215 | 17-18 y | USS | Offspring adiposity mediates maternal obesity/diabetes steatosis risk | [55] |

| ALSPAC | UK | 3,353 | 24 y | TE | [56] | |

| ESPRESSO | Sweden | 165 | <25 y | Biopsy | Maternal obesity increases MASLD/severe MASLD in young adults | [57] |

| SPCS | China | 430 | 8 y | TE | Offspring steatosis aOR 8.26 for maternal obesity and GDM | [58] |

| Healthy Start | USA | 278 | 4-8 y | MRI | Poor maternal diet increases offspring steatosis susceptibility | [59] |

| Factor | Association with pediatric MASLD risk | Potential role in DOHaD programming |

| Maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity | Consistently identified as a modifiable risk factor | Programs fetal liver for high lipid storage due to nutrient oversupply |

| Breastfeeding (≥6 months) | Frequently associated with duration-dependent protective effect | Promotes a slower, healthier growth trajectory and provides bioactive factors that modulate metabolism |

| Rapid post-natal catch-up growth | May contribute to later hepatic steatosis | Exacerbates metabolic stress on an in utero-programmed liver, accelerating fat accumulation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).