Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Biochemical Measurements

2.3. Dietary Added Sugar Consumption

2.4. RT-qPCR

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

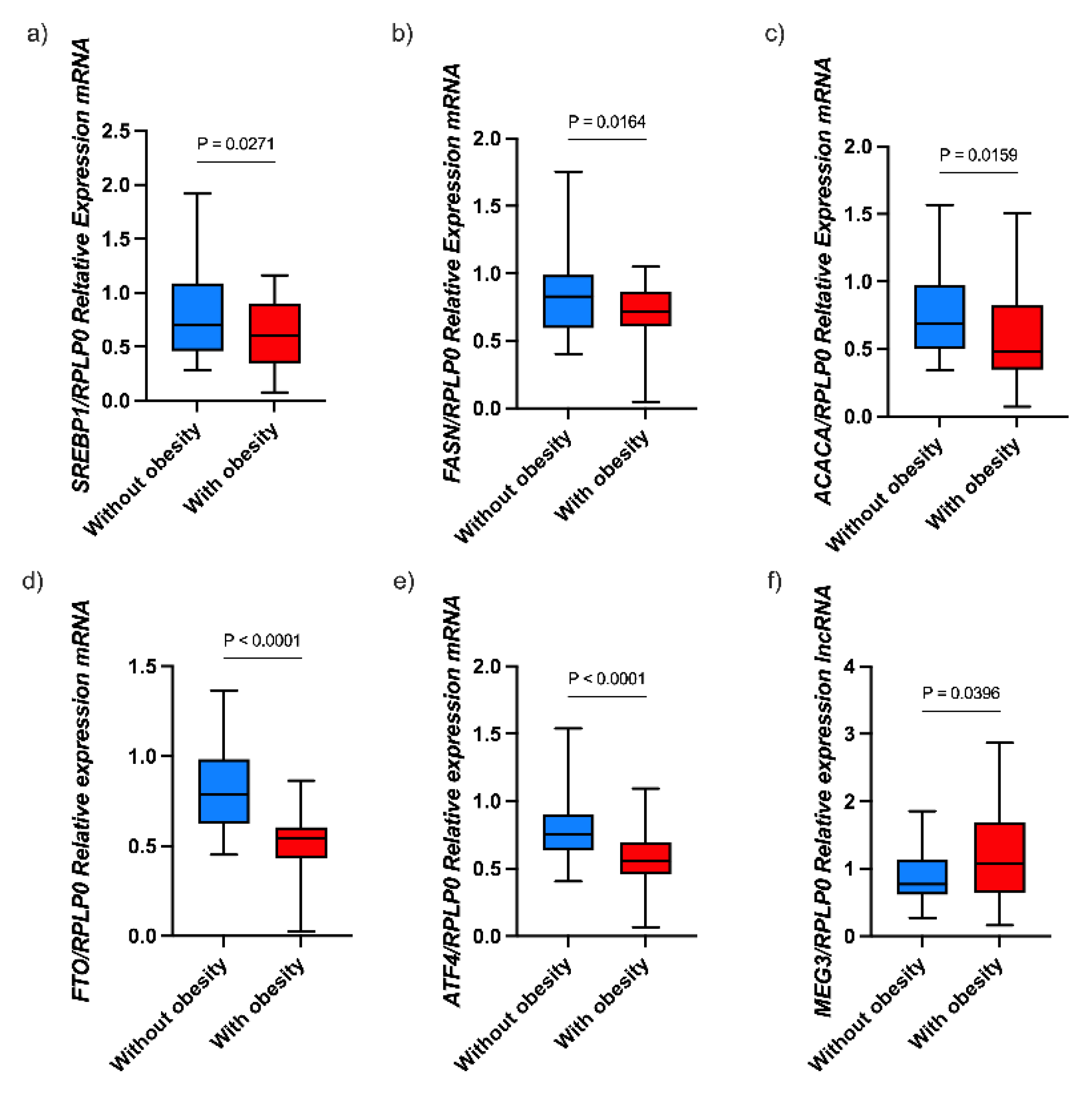

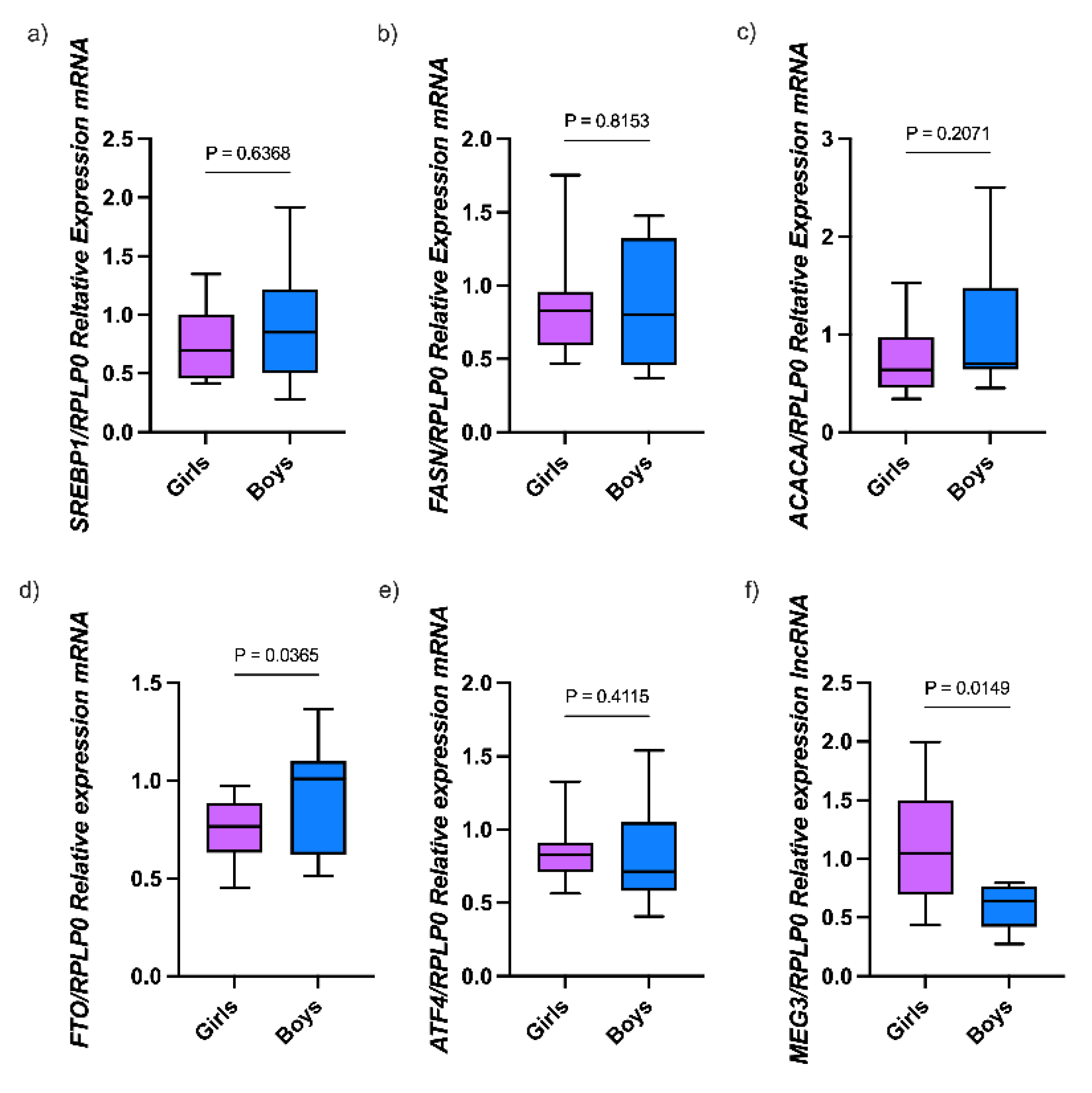

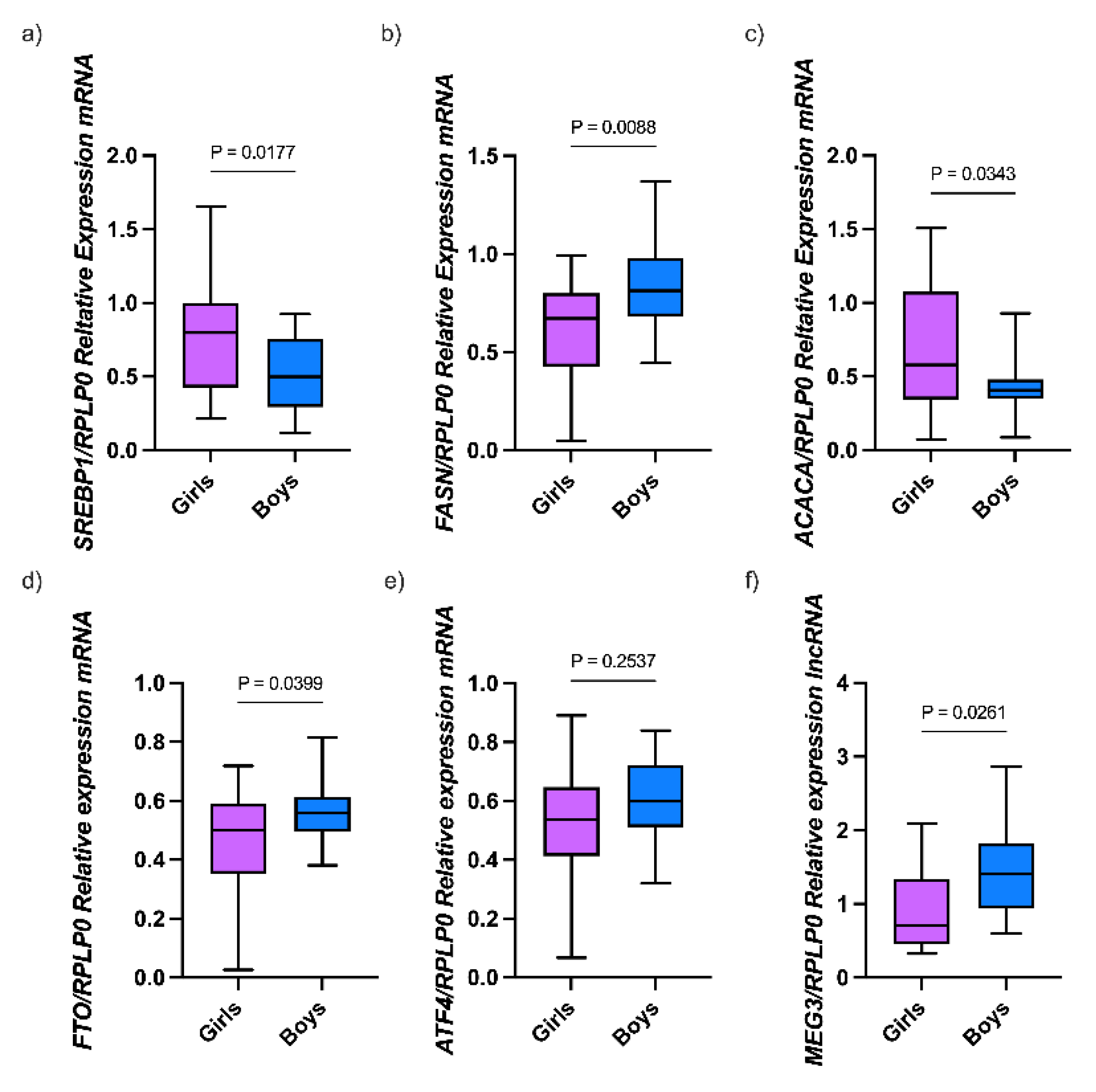

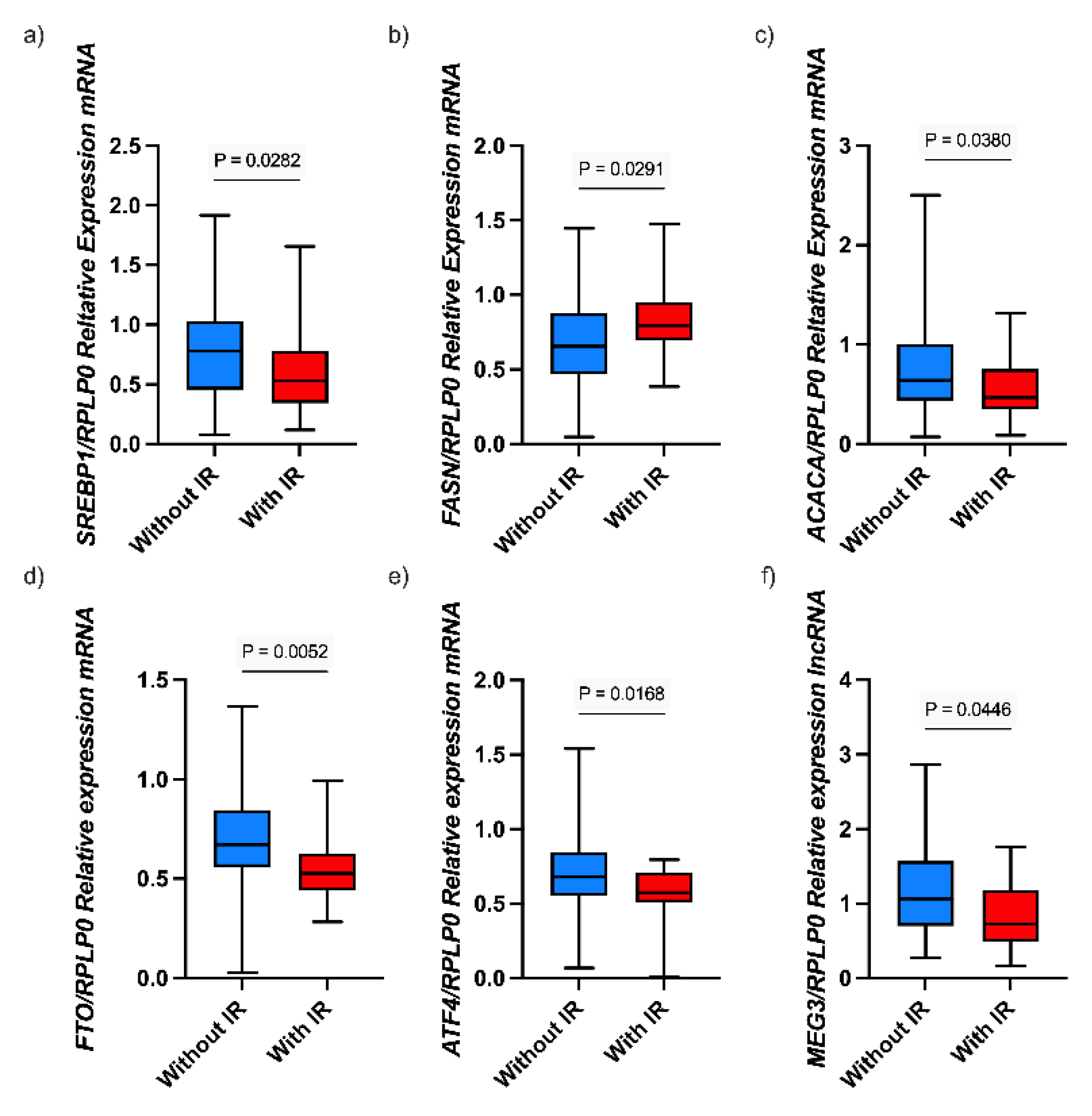

3.2. Expression of Genes Involved in Lipid Metabolism in Children with Obesity

3.2. Associations Between lncRNA MEG3 and Gene Expression and Biochemical Parameters

3.3. Association Between Added Sugar Intake and Molecular and Biochemical Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACACA | Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase ALPHA |

| ATF4 | Activating Transcription Factor 4; |

| BAM | Mexican Food Composition Table |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CDC | Disease Control and Prevention |

| CHO | Cholesterol |

| ENSANUT | Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey |

| FASN | Fatty Acid Synthase |

| FFQ | food frequency questionnaire |

| FTO | Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Gene |

| HDL-C | High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance |

| IR | Insulin resistance |

| LDL-C | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| MEG3 | Maternally Expressed Gene 3 |

| PBMCs | peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ |

| SREBP1 | Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1 |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| TG | Triglycerides |

References

- Kerr, J.A.; Patton, G.C.; Cini, K.I.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbas, N.; Abd Al Magied, A.H.A.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; Abdollahi, A.; Abdoun, M.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Prevalence of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity, 1990–2021, with Forecasts to 2050: A Forecasting Study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet 2025, 405, 785–812. [CrossRef]

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Morales-Ruan, C.; Valenzuela-Bravo, D.G.; Humarán, I.M.G.; Ávila-Arcos, M.A. Prevalencias de Sobrepeso y Obesidad En Población Escolar y Adolescente de México. Ensanut Continua 2020-2022. Salud Publica Mex 2023, 65, s218–s224. [CrossRef]

- Mercado-Mercado, G. Childhood Obesity in Mexico: A Constant Struggle and Reflection for Its Prevention on the Influence of Family and Social Habits. Obes Med 2023, 44, 100521. [CrossRef]

- Rasool, A.; Mahmoud, T.; Mathyk, B.; Kaneko-Tarui, T.; Roncari, D.; White, K.O.; O’Tierney-Ginn, P. Obesity Downregulates Lipid Metabolism Genes in First Trimester Placenta. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 19368. [CrossRef]

- Shettigar, V.K.; Garikipati, V.N.S. Role of LncRNAs in Pathophysiology of Obesity. Curr Opin Physiol 2025, 44, 100832. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Klibanski, A. MEG3 Noncoding RNA: A Tumor Suppressor. J Mol Endocrinol 2012, 48, R45–R53. [CrossRef]

- Zavhorodnia, N.Yu. The Clinical and Pathogenetic Role of LncRNA MEG3 and MiRNA-421 in Obese Children with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Zaporozhye Medical Journal 2022, 24, 293–300. [CrossRef]

- Parvar, S.N.; Mirzaei, A.; Zare, A.; Doustimotlagh, A.H.; Nikooei, S.; Arya, A.; Alipoor, B. Effect of Metformin on the Long Non-Coding RNA Expression Levels in Type 2 Diabetes: An in Vitro and Clinical Trial Study. Pharmacological Reports 2023, 75, 189–198. [CrossRef]

- Heydari, N.; Sharifi, R.; Nourbakhsh, M.; Golpour, P.; Nourbakhsh, M. Long Non-Coding RNAs TUG1 and MEG3 in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Their Association with Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Markers. J Endocrinol Invest 2023, 46, 1441–1448. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Long, M.; Yue, N.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhao, H.; Deng, W. LncRNA MEG3 Restrains Hepatic Lipogenesis via the FOXO1 Signaling Pathway in HepG2 Cells. Cell Biochem Biophys 2024, 82, 1253–1259. [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Huang, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T.; Yang, M.; Sun, C. LncRNA MEG3 Functions as a CeRNA in Regulating Hepatic Lipogenesis by Competitively Binding to MiR-21 with LRP6. Metabolism 2019, 94, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Qie, D.; Yang, F.; Wu, J. LncRNA MEG3 Aggravates Adipocyte Inflammation and Insulin Resistance by Targeting IGF2BP2 to Activate TLR4/NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 121, 110467. [CrossRef]

- Endy, E.J.; Yi, S.-Y.; Steffen, B.T.; Shikany, J.M.; Jacobs, D.R.; Goins, R.K.; Steffen, L.M. Added Sugar Intake Is Associated with Weight Gain and Risk of Developing Obesity over 30 Years: The CARDIA Study. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2024, 34, 466–474. [CrossRef]

- Magriplis, E.; Michas, G.; Petridi, E.; Chrousos, G.P.; Roma, E.; Benetou, V.; Cholopoulos, N.; Micha, R.; Panagiotakos, D.; Zampelas, A. Dietary Sugar Intake and Its Association with Obesity in Children and Adolescents. Children 2021, 8, 676. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Guo, Q.; Chang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wei, W. Effects of Maternal High-Fructose Diet on Long Non-Coding RNAs and Anxiety-like Behaviors in Offspring. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 4460. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huang, Z.; Du, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, S.; Guo, F. ATF4 Regulates Lipid Metabolism and Thermogenesis. Cell Res 2010, 20, 174–184. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Zhang, T.; Yu, S.; Lee, S.; Calabuig-Navarro, V.; Yamauchi, J.; Ringquist, S.; Dong, H.H. ATF4 Protein Deficiency Protects against High Fructose-Induced Hypertriglyceridemia in Mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 25350–25361. [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Chen, X.; Cheng, S.; Shu, L.; Yan, M.; Yao, L.; Wang, B.; Huang, S.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Z.; et al. FTO Promotes SREBP1c Maturation and Enhances CIDEC Transcription during Lipid Accumulation in HepG2 Cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2018, 1863, 538–548. [CrossRef]

- Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Mejía-Rodríguez, F.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Gómez-Acosta, L.M.; Rangel-Baltazar, E.; Flores-Aldana, M.E. Dietary Intake and Adequacy of Energy and Nutrients in Mexican Adolescents: Results from Ensanut 2012. Salud Publica Mex 2018, 60, 404–413. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Silva I; Barragán-Vázquez S; Mongue-Urrea A; Mejía-Rodríguez F; Rodríguez-Ramírez S; Rivera-Dommarco J Base de Alimentos de México 2012 (BAM): Compilación de La Composición de Los Alimentos Frecuentemente Consumidos En El País. Versión 18.1.2 2023 Available online: https://insp.mx/informacion-relevante/bam-bienvenida (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Ramírez-Silva, I.; Jiménez-Aguilar, A.; Valenzuela-Bravo, D.; Martinez-Tapia, B.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, S.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Angulo-Estrada, S.; Shamah-Levy, T. Methodology for Estimating Dietary Data from the Semi-Quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire of the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012. Salud Publica Mex 2016, 58, 629. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Wu, W.; Zhao, J.; Li, X.; Xiong, R.; Ding, X.; Yuan, D.; Yuan, C. LncRNA MEG3: Targeting the Molecular Mechanisms and Pathogenic Causes of Metabolic Diseases. Curr Med Chem 2024, 31, 6140–6153. [CrossRef]

- Daneshmoghadam, J.; Omidifar, A.; Akbari Dilmaghani, N.; Karimi, Z.; Emamgholipour, S.; shanaki, M. The Gene Expression of Long Non-coding RNAs (LncRNAs): MEG3 and H19 in Adipose Tissues from Obese Women and Its Association with Insulin Resistance and Obesity Indices. J Clin Lab Anal 2021, 35. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Long, M.; Yue, N.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhao, H.; Deng, W. LncRNA MEG3 Restrains Hepatic Lipogenesis via the FOXO1 Signaling Pathway in HepG2 Cells. Cell Biochem Biophys 2024, 82, 1253–1259. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yang, G.; Wang, W. LncRNA MEG3 Promotes Hepatic Insulin Resistance by Serving as a Competing Endogenous RNA of MiR-214 to Regulate ATF4 Expression. Int J Mol Med 2018. [CrossRef]

- Di, F.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Hong, Y.; Chen, Z.-J.; Du, Y. Activating Transcriptional Factor 4 Correlated with Obesity and Insulin Resistance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Gynecological Endocrinology 2019, 35, 351–355. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, Z.; Nie, Y.; Li, M.; Mo, D.; et al. ATF4 Regulates SREBP1c Expression to Control Fatty Acids Synthesis in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes Differentiation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 2016, 1859, 1459–1469. [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Maksoud, R.S.; Zidan, H.E.; Saleh, H.S.; Amer, S.A. Visfatin and SREBP-1c MRNA Expressions and Serum Levels Among Egyptian Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2020, 24, 409–419. [CrossRef]

- Heydari, N.; Sharifi, R.; Nourbakhsh, M.; Golpour, P.; Nourbakhsh, M. Long Non-Coding RNAs TUG1 and MEG3 in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Their Association with Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Markers. J Endocrinol Invest 2023, 46, 1441–1448. [CrossRef]

- Szpigel, A.; Hainault, I.; Carlier, A.; Venteclef, N.; Batto, A.F.; Hajduch, E.; Bernard, C.; Ktorza, A.; Gautier, J.F.; Ferré, P.; et al. Lipid Environment Induces ER Stress, TXNIP Expression and Inflammation in Immune Cells of Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 399–412. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, J.; Liu, B.; Lv, Z.; Xia, T.; Xiao, F.; Chen, S.; Guo, F. Central Activating Transcription Factor 4 (ATF4) Regulates Hepatic Insulin Resistance in Mice via S6K1 Signaling and the Vagus Nerve. Diabetes 2013, 62, 2230–2239. [CrossRef]

- Kitakaze, K.; Oyadomari, M.; Zhang, J.; Hamada, Y.; Takenouchi, Y.; Tsuboi, K.; Inagaki, M.; Tachikawa, M.; Fujitani, Y.; Okamoto, Y.; et al. ATF4-Mediated Transcriptional Regulation Protects against β-Cell Loss during Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in a Mouse Model. Mol Metab 2021, 54, 101338. [CrossRef]

- Yagan, M.; Najam, S.; Hu, R.; Wang, Y.; Dickerson, M.; Dadi, P.; Xu, Y.; Simmons, A.J.; Stein, R.; Adams, C.M.; et al. Atf4 Protects Islet β-Cell Identity and Function under Acute Glucose-Induced Stress but Promotes β-Cell Failure in the Presence of Free Fatty Acid. Diabetes 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, T. Regulation of Activating Transcription Factor 4 (Atf4) Expression by Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated (Fto) in Mouse Hepatocyte Cells. Acta Endocrinologica (Bucharest) 2021, 17, 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Berulava, T.; Horsthemke, B. The Obesity-Associated SNPs in Intron 1 of the FTO Gene Affect Primary Transcript Levels. European Journal of Human Genetics 2010, 18, 1054–1056. [CrossRef]

- Doaei, S.; Kalantari, N.; Izadi, P.; Salonurmi, T.; Jarrahi, A.M.; Rafieifar, S.; Azizi Tabesh, G.; Rahimzadeh, G.; Gholamalizadeh, M.; Goodarzi, M.O. Interactions between Macro-Nutrients’ Intake, FTO and IRX3 Gene Expression, and FTO Genotype in Obese and Overweight Male Adolescents. Adipocyte 2019, 8, 386–391. [CrossRef]

- Lappalainen, T.; Kolehmainen, M.; Schwab, U.; Pulkkinen, L.; de Mello, V.D.F.; Vaittinen, M.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Poutanen, K.; Uusitupa, M.; Gylling, H. Gene Expression of FTO in Human Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue, Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells and Adipocyte Cell Line. Lifestyle Genom 2010, 3, 37–45. [CrossRef]

- Doaei, S.; Kalantari, N.; Keshavarz Mohammadi, N.; Izadi, P.; Gholamalizadeh, M.; Eini-Zinab, H.; Salonurmi, T.; Mosavi Jarrahi, A.; Rafieifar, S.; Najafi, R.; et al. The Role of FTO Genotype in the Association Between FTO Gene Expression and Anthropometric Measures in Obese and Overweight Adolescent Boys. Am J Mens Health 2019, 13. [CrossRef]

- Yuzbashian, E.; Asghari, G.; Hedayati, M.; Zarkesh, M.; Mirmiran, P.; Khalaj, A. The Association of Dietary Carbohydrate with FTO Gene Expression in Visceral and Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue of Adults without Diabetes. Nutrition 2019, 63–64, 92–97. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Huang, W.; Rao, J.; Yan, D.; Yuan, J. Demethylase FTO-Mediated M6A Modification of LncRNA MEG3 Activates Neuronal Pyroptosis via NLRP3 Signaling in Cerebral Ischemic Stroke. Mol Neurobiol 2024, 61, 1023–1043. [CrossRef]

- Bravard, A.; Veilleux, A.; Disse, E.; Laville, M.; Vidal, H.; Tchernof, A.; Rieusset, J. The Expression of FTO in Human Adipose Tissue Is Influenced by Fat Depot, Adiposity, and Insulin Sensitivity. Obesity 2013, 21, 1165–1173. [CrossRef]

- Taneera, J.; Khalique, A.; Abdrabh, S.; Mohammed, A.K.; Bouzid, A.; El-Huneidi, W.; Bustanji, Y.; Sulaiman, N.; Albasha, S.; Saber-Ayad, M.; et al. Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated (FTO) Gene Is Essential for Insulin Secretion and β-Cell Function: In Vitro Studies Using INS-1 Cells and Human Pancreatic Islets. Life Sci 2024, 339, 122421. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total (n= 71) | Without obesity (n= 27) |

With obesity (n= 44) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 8.94 ± 1.680 | 9.111 ± 1.740 | 8.84 ± 1.660 | 0.514a |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 28 (39.44) | 9 (32.14) | 19 (67.86) | 0.410b |

| Female | 43 (60.56) | 18 (41.86) | 25 (58.14) | |

| Waist circ (cm) | 74.338 ± 13.462 | 60.833 ± 7.302 | 82.625 ± 8.831 | < 0.001a |

| Hip circ (cm) | 82.047 ± 12.037 | 70.940 ± 6.962 | 88.863 ± 9.031 | < 0.001a |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | 22.725 (16.405— 25.184) | 16.113 (15.527—16.645) | 24.292 (23.787—25.410) | < 0.001c |

| BMI percentile | 76.352 ± 30.283 | 41.555 ± 20.905 | 97.704 ± 1.373 | < 0.001a |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 87.288 ± 7.991 | 88.185 ± 6.314 | 86.738 ± 8.890 | 0.463a |

| Insulin (µIU/ml) | 14.430 (8.400—21.400) | 8.400 (7.200—9.550) | 17.880 (15.000—22.100) | < 0.001c |

| HOMA-IR | 3.066 (1.767—4.796) | 1.794 (1.596— 2.092) | 3.726 (3.123—4.801) | < 0.001c |

| ≥3, n (%) | 36 (50.70) | 6 (22.22) | 30 (68.18) | < 0.001b |

| Total CHO (mg/dL) | 164.253 ± 27.204 | 164.185 ± 31.027 | 164.295± 24.953 | 0.986a |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 47.983 ± 10.577 | 52.981 ± 8.716 | 44.915 ± 10.529 | < 0.001a |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 85.982 ± 25.146 | 86.937 ± 28.916 | 85.396 ± 22.866 | 0.804a |

| TG (mg/dL) | 129.7 (89.100—219.300) | 100.600 (85.345—137.136) | 157.050 (123.967—200.893) | 0.009c |

| Added sugar (g) | 73.724 ± 36.195 | 71.751 ± 44.585 | 74.934 ± 30.710 | 0.766a |

| ≥ 50 g, n (%) | 58 (81.69) | 20 (74.07) | 38 (86.36) | 0.194b |

| Total energy intake (Kcal) | 2383.5 (1983—2787) | 2340 (1908—2698) | 2490 (2085—2870) | 0.294c |

| BMI: Body mass index; HOMA-IR: Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; CHO: Cholesterol; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG: Triglycerides. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or the median (interquartile range) for parametric and nonparametric data, respectively. aStudent’s t test; bChi-square test; cMann-Whitney test. | ||||

| Gene | Rho | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| SREBP1 | 0.408 | 0.001 |

| FASN | 0.238 | 0.025 |

| ACACA | 0.130 | 0.307 |

| FTO | 0.389 | 0.001 |

| ATF4 | 0.422 | < 0.001 |

| SREBP1: Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1; FASN: Fatty Acid Synthase; ACACA: Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase Alpha; FTO: Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Gene; ATF4: Activating Transcription Factor 4. Rho values correspond to the Spearman correlation coefficients. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. | ||

| Variable | SREBP1c | FASN | ACACA | FTO | ATF4 | MEG3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rho | P-value | Rho | P-value | Rho | P-value | Rho | P-value | Rho | P-value | Rho | P-value | ||

| BMI percentile | -0.194 | 0.107 | -0.084 | 0.469 | -0.347 | 0.003 | -0.452 | < 0.001 | -0.383 | < 0.001 | 0.069 | 0.585 | |

| Waist circ (cm) | -0.223 | 0.062 | -0.023 | 0.852 | -0.408 | < 0.001 | -0.497 | < 0.001 | -0.340 | 0.003 | 0.029 | 0.816 | |

| Hip circ (cm) | -0.185 | 0.124 | -0.002 | 0.981 | -0.307 | 0.009 | -0.466 | < 0.001 | -0.293 | 0.012 | 0.020 | 0.874 | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | -0.260 | 0.029 | 0.304 | 0.012 | -0.187 | 0.117 | -0.074 | 0.536 | 0.137 | 0.253 | -0.006 | 0.956 | |

| Insulin (µIU/ml) | -0.354 | 0.003 | 0.223 | 0.073 | -0.425 | < 0.001 | -0.426 | < 0.001 | -0.267 | 0.026 | -0.168 | 0.193 | |

| HOMA-IR | -0.373 | 0.001 | 0.254 | 0.040 | -0.438 | < 0.001 | -0.419 | < 0.001 | -0.241 | 0.046 | -0.193 | 0.135 | |

| Total CHO (mg/dL) | -0.071 | 0.558 | -0.082 | 0.507 | 0.105 | 0.381 | -0.064 | 0.592 | -0.078 | 0.517 | 0.110 | 0.289 | |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 0.046 | 0.701 | -0.168 | 0.172 | 0.302 | 0.010 | 0.202 | 0.090 | 0.127 | 0.288 | -0.066 | 0.606 | |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | -0.042 | 0.725 | -0.024 | 0.843 | 0.163 | 0.174 | -0.010 | 0.929 | -0.119 | 0.320 | 0.090 | 0.479 | |

| TG (mg/dL) | -0.039 | 0.743 | 0.090 | 0.465 | -0.276 | 0.019 | -0.209 | 0.079 | -0.077 | 0.518 | 0.036 | 0.774 | |

| BMI: Body Mass Index; HOMA-IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance; CHO: Cholesterol; HDL-C: High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; LDL: Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol; TG: Triglycerides; SREBP1: Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1; FASN: Fatty Acid Synthase; ACACA: Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase Alpha; FTO: Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Gene; ATF4: Activating Transcription Factor 4; MEG3: Maternally Expressed Gene 3. Rho values correspond to the Spearman correlation coefficients. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. | |||||||||||||

| Gene | Rho | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| SREBP1 | -0.317 | 0.026 |

| FASN | -0.003 | 0.979 |

| ACACA | -0.314 | 0.026 |

| FTO | -0.355 | 0.011 |

| ATF4 | -0.113 | 0.451 |

| MEG3 | -0.084 | 0.599 |

| SREBP1: Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1; FASN: Fatty Acid Synthase; ACACA: Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase Alpha; FTO: Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Gene; ATF4: Activating Transcription Factor 4; MEG3: Maternally Expressed Gene 3. Rho values correspond to the Spearman correlation coefficients. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).