Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Nutritional Evaluation

2.3. Anthropometric Evaluation

2.4. Biochemicals

Plasma Amino Acids

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Biochemical Parameters

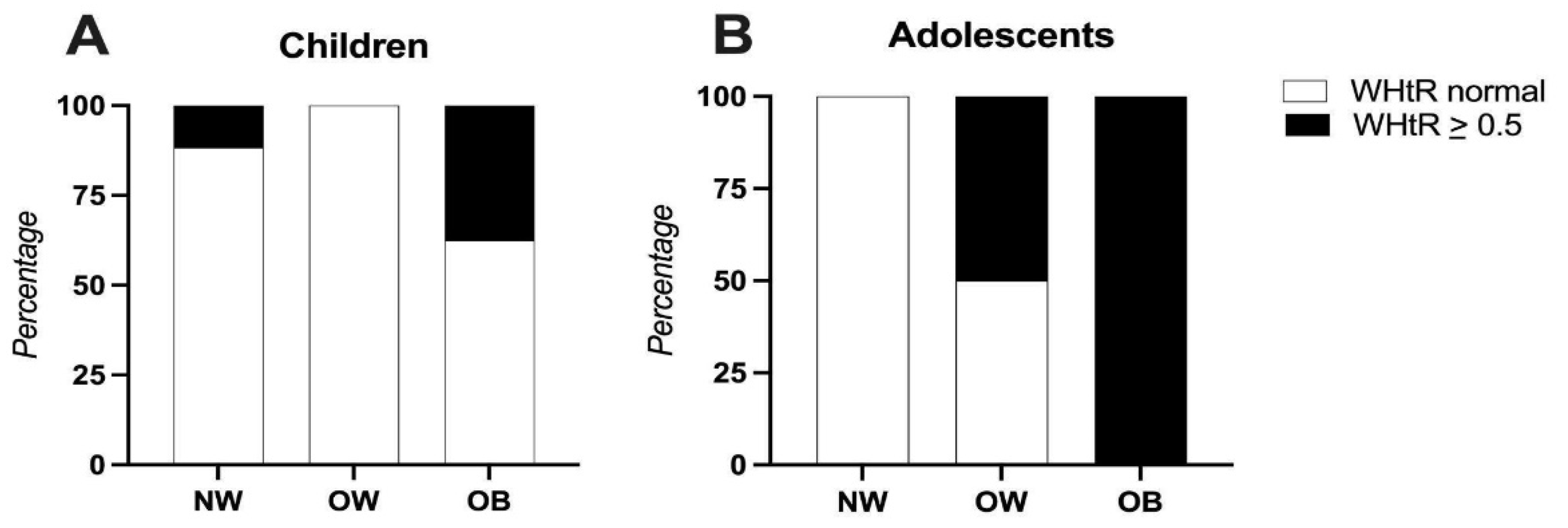

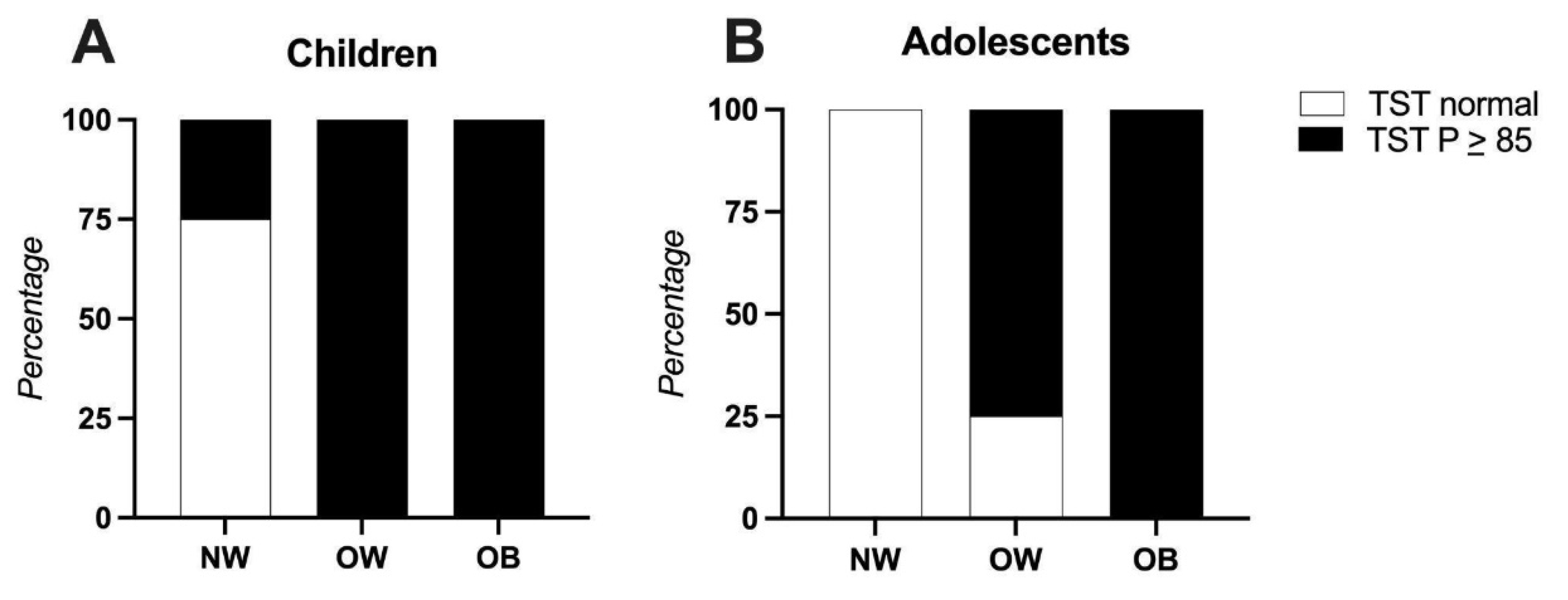

3.3. Anthropometric Indicators

3.4. Family Medical History

3.5. Differences in Adequacy Percentage of Nutrients Between Children and Adolescents

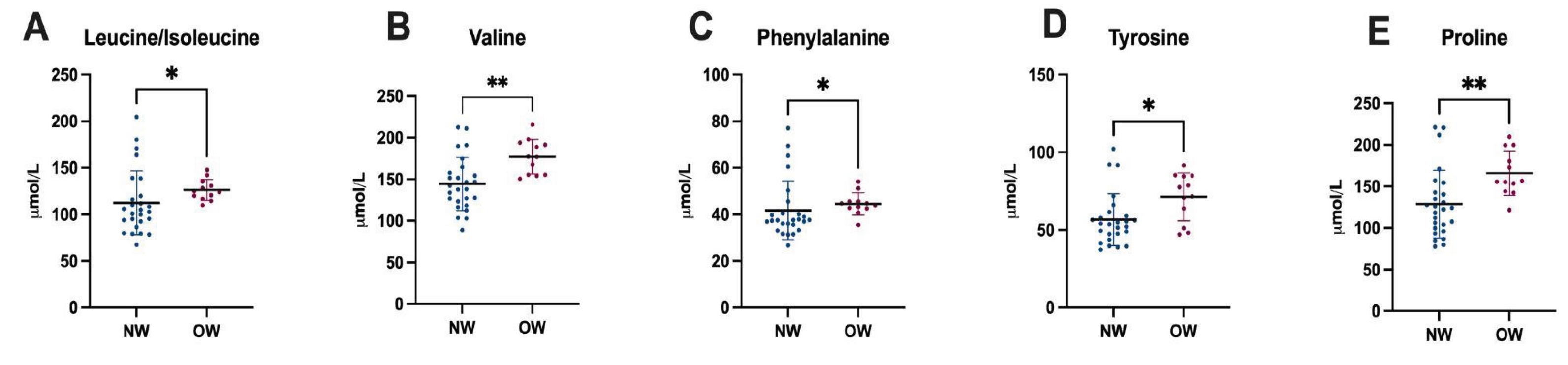

3.6. Plasma Amino Acid Levels

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| AP | Adequacy Percentage |

| RDA | Recommended Dietary Allowance |

| WHtR | Waist-to-Height Ratio |

| TST | Triceps Skinfold Thickness |

| NW | Normal Weight |

| OW | Overweight |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Morales-Ruan, C.; Humaran, I.M.-G.; A Ávila-Arcos, M.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; Valenzuela-Bravo, D.G. Prevalencias de sobrepeso y obesidad en población escolar y adolescente de México. Ensanut Continua 2020-2022. Salud Publica De Mex. 2023, 66, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Ávila-Arcos, M.A.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, S.; Morales-Ruán, M.D.C.; Gómez-Acosta, L.M.; García-Feregrino, R.; Gaona-Pineda, E.B.; González-Castell, L.D.; Rivera-Dommarco, J. Desnutrición crónica en población infantil de localidades con menos de 100 000 habitantes en México. Salud Publica De Mex. 2019, 61, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Romero-Martínez, M.; Vielma-Orozco, E.; Heredia-Hernández, O.; Mojica-Cuevas, J.; Rivera-Dommarco, J. Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición 2018-19: metodología y perspectivas. Salud Publica De Mex. 2019, 61, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicios de Salud de Morelos. (2021a). Diagnóstico estatal de salud 2021: Fichas técnicas de centros de salud por municipio [PDF file]. Servicios de Salud de Morelos. https://ssm.gob.mx/portal/diagnostico-estatal-en-salud/2021/Diagnostico%20Estatal%20de%20Salud%2C%20Ed%202021.pdf.

- E Moreno-Saracho, J.; Gatica-Domínguez, G.; Cortés, J.D.; Henao-Moran, S.A.; A Rivera, J. Condición física de escolares tras intervención educativa para prevenir obesidad infantil en Morelos, México. Salud Publica De Mex. 2019, 61, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyele, T.K. Food Choice and Nutritional Intake of Children and Adolescents. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Anal. 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, M.; Petriczko, E.; Raducha, D.; Kostrzeba, E.; Berus, E.; Ratajczak, J. Assessment of Biochemical Parameters in 8- and 9-Year-Old Children with Excessive Body Weight Participating in a Year-Long Intervention Program. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjoo, S.; Bradley, M.; Melchor, J.; Carr, R. Obesity and malnutrition in children and adults: A clinical review. Obes. Pillars 2023, 8, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todisco, C.F.; Agostinelli, M.; La Mendola, A.; Verduci, E.; Calcaterra, V.; Zuccotti, G.; Dolor, J.; Tosi, M.; Milanta, C.; Bona, F. Micronutrient Deficiency in Children and Adolescents with Obesity—A Narrative Review. Children 2023, 10, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztefko, K.; Wójcik, M.; Berska, J.; Bugajska, J. Amino acid profile in overweight and obese prepubertal children – can simple biochemical tests help in the early prevention of associated comorbidities? Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1274011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Wall, M.; Sherwood, N.E.; Corbeil, T.; French, S.A.; Berge, J.M. Obesity in Adolescence Predicts Lower Educational Attainment and Income in Adulthood: The Project EAT Longitudinal Study. Obesity 2018, 26, 1467–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genetic Metabolic Dietitians International. (2025). MetabolicPro. https://www.gmdi.org/MetabolicPro.

- Bourges, H.; Casanueva, E.; Rosado, J. L. (2009). Recomendaciones de ingestión de nutrimentos para la población mexicana (Tomo 1 y 2). Editorial Médica Panamericana.

- World Health Organization. Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry. World Health Organization: Geneva, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatrica. Supplement 2006, 95, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisancho, R. Anthropometric standards. An interactive nutritional reference of body size and body composition for children and adults; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio: Report of a WHO expert consultation. World Health Organization: Geneva, 8–11 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- International Diabetes Federation. (2007). The IDF consensus definition of the metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation.

- Pietrobelli, A.; Heo, M.; Bedogni, G.; Brambilla, P. Waist circumference-to-height ratio predicts adiposity better than body mass index in children and adolescents. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 943–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra-González, I.; Belmont-Martínez, L.; Fernández-Lainez, C.; Guillén-López, S.; López-Mejía, L.; Nieto-Carrillo, R.I.; Vela-Amieva, M. Importance of Studying Older Siblings of Patients Identified by Newborn Screening: a Single-Center Experience in Mexico. J. Inborn Errors Metab. Screen. 2021, 9, e20210001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle-Leal, J.; Abundis-Castro, L.; Hernández-Escareño, J.; Flores-Rubio, S. Índice cintura-estatura como indicador de riesgo metabólico en niños. Revista Chilena de Pediatría 2015, 87, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejero, M.E.; Galván, M.; Fernández, J.C.; López-Rodríguez, G.; Suárez-Diéguez, T.; Estrada-Neria, A. Common polymorphisms in MC4R and FTO genes are associated with BMI and metabolic indicators in Mexican children: Differences by sex and genetic ancestry. Gene 2020, 754, 144840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Paredez, B.; León-Reyes, G.; Argoty-Pantoja, A.D.; Velázquez-Cruz, R.; Flores, Y.N.; Salmerón, J.; Hidalgo-Bravo, A. Interaction between SIDT2 and ABCA1 Variants with Nutrients on HDL-c Levels in Mexican Adults. Nutrients 2023, 15, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Kido, J.; Shimizu, K.; Matsumoto, S. Associations among amino acid, lipid, and glucose metabolic profiles in childhood obesity. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coarfa, C.; Sharma, S.; Puyau, M.; Kanchi, R.; Bacha, F.; El-Ayash, H.; Mohamad, M. Distinct Amino Acid Profile Characterizes Youth With or at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2024, 73, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootha, V.K.; Grinspoon, S.K.; Shaham, O.; McCarthy, M.A.; McCormack, S.E.; Clish, C.B.; Deik, A.A.; Gerszten, R.E.; Fleischman, A.; Wang, T.J. Circulating branched-chain amino acid concentrations are associated with obesity and future insulin resistance in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Obes. 2012, 8, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, E.-G. Waist-to-height ratio as a screening tool for obesity and cardiometabolic risk. Korean J. Pediatr. 2016, 59, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endocrinology, T.L.D. &. Redefining obesity: advancing care for better lives. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025, 13, 236–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.; Holder, S.M.; Schmalz, D.L.; Fipps, D.C. Family history of obesity and the influence on physical activity and dietary adherence after bariatric surgery. J. Perioper. Pr. 2021, 32, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.S.; Bell, W.; Charrondiere, U.R. Measurement Errors in Dietary Assessment Using Self-Reported 24-Hour Recalls in Low-Income Countries and Strategies for Their Prevention. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2017, 8, 980–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrestal, S.G. Energy intake misreporting among children and adolescents: a literature review. Matern. Child Nutr. 2010, 7, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2015). Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children. Recommendations and remarks. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285525/.

- Gimenez Blasi, N.; Antonio Latorre, J.; Martinez Bebia, M.; Olea Serrano, F.; Mariscal Arcas, M. Comparison of diet quality between young children and adolescents in the Mediterranean basin and the influence of life habits. Nutrición Hospitalaria 2019, 36, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosa, V.L.; Vencato, P.H.; Ufrgs, B.; Rockett, F.C.; Corrêa, R.d.S. Padrões alimentares de escolares: existem diferenças entre crianças e adolescentes? Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2017, 22, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapparova, K.M.; Lapik, I.A.; Galchenko, A.V. Micronutrient status in obese patients: A narrative review. Obes. Med. 2020, 18, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Characteristics of the Population | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Children n = 38 |

Adolescents n = 17 |

|

| Age ± SD | 6.9 ± 0.9 | 10.1 ± 1.2 |

| Gender, n (%) (Female) (Male) |

20 (52.6) 18 (47.4) |

10 (58.8) 7 (41.2) |

| Z Score BMI interpretation, n (%) (Underweight) (Normal) (Overweight) (Obese) |

0 26 (68.4) 4 (10.5) 8 (21.1) |

2 (11.8) 7 (41.2) 4 (23.5) 4 (23.5) |

| Biochemical and metabolic alterations | ||

| Anemia, n (%) | 12 (31.6) | 4 (26.5) |

| High Glucose levels, n (%) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (5.9) |

| Elevated Total Cholesterol, n (%) | 7 (18.4) | 4 (23.5) |

| Elevated LDL Cholesterol, n (%) | 4 (10.5) | 3 (17.6) |

| HDL, n (%) (Low) (Borderline low) (Optimal) |

12 (31.6) 22 (57.9) 4 (10.5) |

5 (29.4) 11 (64.7) 1 (5.9) |

| Elevated Triglycerides, n (%) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (11.8) |

| Elevated AST, n (%) | 11 (28.9) | 2 (11.8) |

| Elevated ALT, n (%) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Z Score Height for age interpretation, n (%) | ||

| (Normal) | 36 (97.3) | 15 (88.2) |

| (Stunted) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (11.8) |

| Mid-arm-circumference interpretation, n (%) | ||

| (Normal) | 25 (65.8) | 13 (76.5) |

| (Underweight risk) | 10 (26.3) | 3 (17.6) |

| (Obesity risk or muscle hypertrophy) | 3 (7.9) | 1 (5.9) |

| Triceps skinfold thickness interpretation, n (%) | ||

| (MM - depletion) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (11.8) |

| (MM below media - Risk) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (5.9) |

| (Average MM) | 12 (31.6) | 5 (29.4) |

| (MM above media - At risk) | 7 (18.4) | 2 (11.8) |

| (MM Excess - obesity) | 17 (44.7) | 7 (41.2) |

| Waist circumference, (cm) | 61.1 ± 11 | 69 ± 13 |

| Waist circumference interpretation, n (%) | ||

| At risk | 8 (21.1) | 4 (23.5) |

| Waist-to-height ratio (media) | 0.49 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.07 |

| Waist-to-height ratio interpretation, n (%) | ||

| At risk | 15 (39.8) | 6 (35.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).