1. Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in gynaecological cancer patients and is the leading cause of death after the cancer itself [

1]. The risk of VTE in gynecological cancer differs according to the site and type of cancer, ranging from 6% in endometrial cancers to 43% in clear cell cancer of the ovary [

2,

3,

4]. Cancer surgery is a major contributor to VTE risk; the first post-operative week is the peak time for VTE, with 75% of VTE occurring in the first 7 days due to the direct effect of surgery [

5]. While VTE occurring from day 8 till day 90 is attributed to the effect of recovery from surgery and adjuvant treatment. Gynecological cancer surgery can be complex and may involve extended hospital stay, factors which contribute to the risk of postoperative VTE [

5]. For this reason, extended thromboprophylaxis for 28 days with Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH) is recommended for all patients undergoing major pelvic-abdominal surgery for cancer [

6]. Although meta-analysis has shown that this approach was successful in significantly reducing VTE risk post-surgery [

6,

7] Observational studies, particularly in endometrial cancer, suggest that the risk of surgery following minimally invasive surgery is low (0.57%) and does not support the use of extended thromboprophylaxis. This suggests that risk assessment is required to identify cases which may benefit from extended prophylaxis [

8,

9,

10].

Lymph node dissection (LND) is an important part of the gynaecological cancer surgery and includes pelvic with or without paraaortic lymph nodes (LN) [

11]. LND is commonly performed in endometrial, vulvar and cervical cancer surgeries and is important in planning adjuvant treatment, particularly in endometrial cancer. The role of routine LND in ovarian cancer is controversial; systemic LND does not improve the overall survival [

12,

13]. According to the LION (Lymphadenectomy in ovarian neoplasms) study, systematic LND in advanced ovarian cancer with clinically negative lymphadenopathy is associated with higher morbidity and mortality [

14]. Sentinel LND is becoming a more common practice to reduce risks of LND, especially in endometrial, cervical, and vulval cancers [

11,

15].

In a large study of mixed cancer types, LN metastasis was reported to have a strong association with increased VTE risk [

16]. The risk varies depending on the type of cancer [

17,

18]. In a large study of prostate cancer, patients who had LND had a significantly higher risk of VTE (6-8 fold) compared with those who did not require the procedure. [

19]. In a large study of early-stage endometrial cancer (stage I-II), [

18]. LND increased the postoperative VTE rate. Patients who underwent open surgery had a VTE rate of 4.3% compared with those who had minimally invasive surgery (MIS), who had a VTE rate of 2.87%. However, the effect of different LND sites on the risk of VTE in gynaecological cancer patients was not explored.

In this study, we investigated the relationship between post-operative VTE risk and the site of LND (pelvic and or para-aortic) in gynaecological cancer patients. We also examined the impact of lymph node metastasis on the risk of VTE within the first 90 days following gynecological cancer surgery

2. Materials and Methods

This study was a retrospective cohort studies and using data collected as part of the Trinity College Dublin (TCD) Gynaecological Cancer Bioresource in Dublin, Ireland. Patients who underwent gynaecological cancer surgery (excluding diagnostic procedures) in St. James Hospital, Dublin, between January 2006 and June 2019 and who consented to take part in the Trinity College Gynaecological Cancer Bioresource were included in the study. The TCD gynaecological cancer bioresource is an extensive bioresource of serum, blood and plasma from gynaecological cancer patients which has been running since 2004. The bioresource invites patients undergoing treatment for gynaecological cancer in St. James's Hospital (SJH) Gynaecology-oncology unit (a tertiary referral centre) in Dublin, Ireland, to donate blood, tissue, and medical data for research. All patients participating in the biobank gave full and informed written consent, and the biobank and the resulting studies are approved by the Tallaght University Hospital / St. James's Hospital Joint Research Ethics Committee. Blood samples are obtained preoperatively. All clinicopathological details are extracted from the hospital records, and patient follow-up is recorded on a dedicated database. Diagnostic histology and radiology are reviewed by the multidisciplinary group at the tumour board at our tertiary cancer care centre prior to and after surgical staging. Patients with prior documented VTE within the last 5 years were excluded from the study. Also, patients with any history of significant haemorrhage outside of a surgical setting within the last 5 years, familial bleeding diathesis, or currently receiving long term anticoagulant therapy were excluded.

Since June 2012, all gynecological cancer patients undergoing cancer surgery (including both open and MIS approaches) routinely receive postoperative thromboprophylaxis for 28 days post-surgery in accordance with the guidelines [

20]. Patients with a BMI < 40 were prescribed 4,500 IU of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Tinzaparin) once daily, while those with a BMI ≥ 40 were prescribed a weight-adjusted dose of 75 IU/kg daily. Anti-embolic compression stocking was provided to all postoperative patients during hospital stay and post discharge as part of the hospital thromboprophylaxis protocol. All patients were followed up for a minimum of 90 days post-surgery; duration of follow-up was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of last follow-up, VTE event, or death.

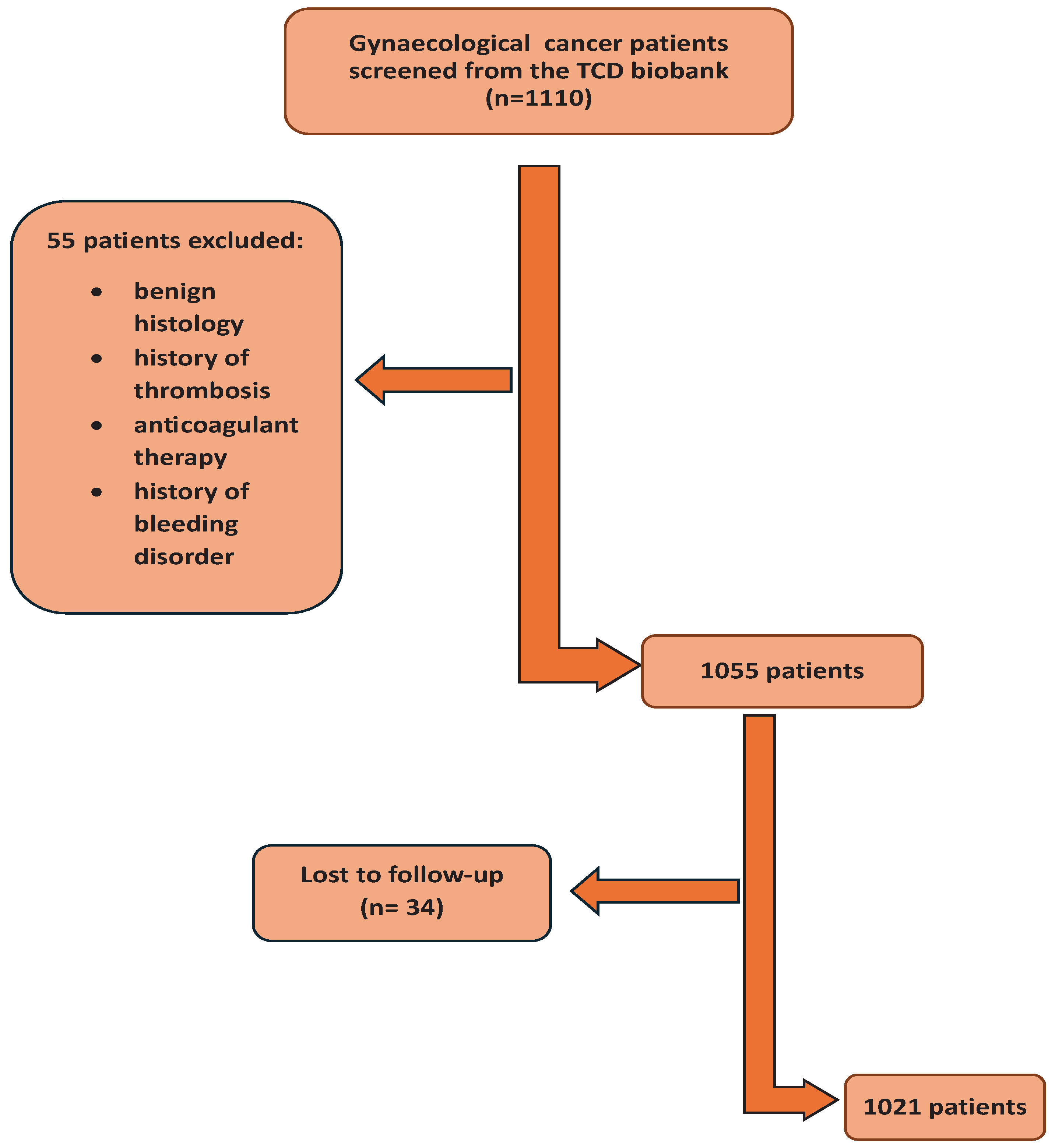

1110 patients who met the inclusion/exclusion criteria were identified the Trinity College Gynaecological cancer bioresource; 55 did not fulfil the inclusion criteria and 34 patients were lost to follow up (

Figure 1). 1021 patients were included in the final analysis

Patient age, body mass index (BMI), final histological diagnosis, tumour origin, FIGO stage, and grade of cancer [

21], surgical approach (open/laparoscopic), surgical complexity (calculated according to a modification of the Aletti score ( Supplementary table 1) [

22]), duration of hospital stay, chemotherapy (neoadjuvant and adjuvant) and radiotherapy (adjuvant), were recorded. Details of LN status were determined by reviewing surgical notes and histopathology reports; the location and number of LN removed were recorded. The location and number of LN positive for metastasis was recorded from the histology reports.

VTE events were confirmed by documented objective testing (compression ultrasonography, venography, or computed tomography and pulmonary angiogram). Asymptomatic thrombotic events (eg PE detected in a routine computerized tomography) were also included when these events were considered clinically significant.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics (Table 1). For each variable, median and inter-quartile range (IQR: 25th to 75th percentiles), and counts (expressed as percentages) were used to describe continuous and categorical variables respectively. Differences in categorical variables were evaluated in univariate analysis using a chi-squared test, and continuous variables were analysed using an unpaired Student t-test.

Univariate analysis (chi-squared) was used to determine the association of LND with post operative VTE. LN parameters which showed a statistically significant association with VTE from the univariate analysis were taken forward to a multivariate Cox regression analysis to determine hazard ratios (HR) and cumulative incidence of VTE adjusted for confounding factors. In all cases P<0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS data system version 26 (IBM corporation).

3. Results

Patient demographics

Ovarian cancer was the dominant tumour site with 488 patients, followed by 389 patients with endometrial cancer, 99 patients with cervical cancer and 36 patients with other types of cancer synchronous pathology. The majority of patients (n=622) underwent open laparotomy and were treatment naïve at the time of surgery. 775 patients received extended thromboprophylaxis. Full demographic details are provided in

Table 1.

41 patients developed VTE in the first 90 days post-surgery. PE was the commonest type of VTE reported in 22 patients, followed by DVT in 14 patients. DVT and PE combined were reported in 2 patients. The remaining patients had different types of thrombosis, including renal, ovarian vein, right arm, and internal jugular vein thrombosis.

There was a significant association between tumour site and VTE within 90 days post-surgery (P=0.031). Patients with ovarian cancer had the highest rate of VTE with 27 events during the follow-up period (65.8% of VTE events recorded), followed by endometrial cancer patients (21.9%), cervical cancer patients (4.8%) and 3 patients who had other types of gynaecological cancer including synchronous cancer (7.3%).

Surgical approach, surgical complexity and duration of hospital stay were all significantly associated with VTE (P=0.0089 <0.001, <0.001 respectively) with the highest rates in patients undergoing open surgery of intermediate to high complexity with associated longer hospital stay.

Of the 41 patients who developed VTE, 12 patients had surgery prior to 2012 and did not receive extended prophylaxis. 28 patients who developed post operative VTE were prescribed extended thromboprophylaxis. Extended prophylaxis did not significantly affect VTE rates (P=0.341).

Stage and grade of cancer were also associated with VTE (P= 0.022; 0.021); however, BMI and histology were not significantly associated with VTE. Effect of LND on VTE rates post surgery

Data on LN status was available in 1006 out of the 1021 patients. 729 patients had pelvic LND, of which 28 (3.84%) developed VTE within 90 days of surgery compared with 13 (4.7%) patients who did not have LND and developed VTE post-surgery.

176 patients had 1-5 LND. 197 patients had 6-10 dissected LN and 356 patients had >10 LN removed There was no significant association between the number of pelvic LN removed and post-operative VTE (P = 0.652) (

Table 2).

452 patients underwent para-aortic LND of which over half had 1-5 nodes removed. Removal of the para-aortic LN was significantly associated with VTE (P < 0.001), with highest rates (14.6%) occurring in patients who had > 10 para-aortic LN removed (

Table 3).

Lymph node metastasis and VTE post surgery

Of the 729 patients who had pelvic LND, 131 patients had pelvic LND positive for metastasis (

Table 4). Significantly higher rates of VTE were observed in patients who had more than 5 pelvic LN positive for metastasis (21.1%) compared with those who had pelvic LND who had pelvic nodes negative for metastasis (3%)(P=0.0000) (

Table 4).

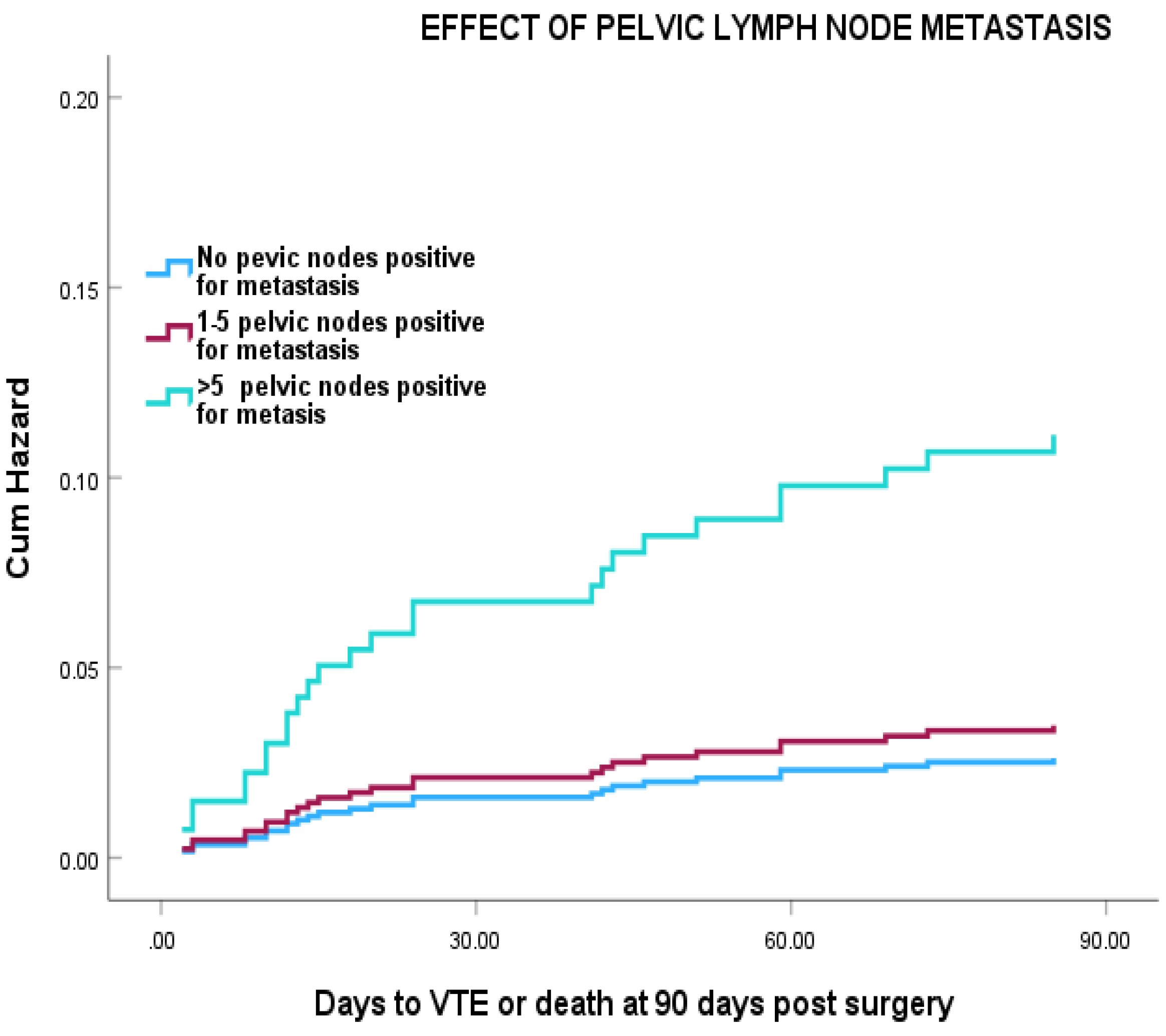

Cox regression analysis showed that, patients with more than 5 positive pelvic LN has a > 7 fold increased risk of VTE compared with node negative patients with the greatest changes occurring in the first 30 days post-surgery (

Figure 2), (HR =7.80 (95% CI 2.64-23.06) (P=0.001). However, this was reduced to HR =4.83 (95% CI: 0.99- 13.9) after adjustment for age, duration of hospital stay and surgical approach.

97 (22.2%) of the 452 patients who had para-aortic LND were positive for metastasis (

Table 3). Higher rates of VTE (27.3%) were found in those with >5 para aortic LN positive for metastasis compared with those who had < 5 positive for metastasis (P=0.0000).

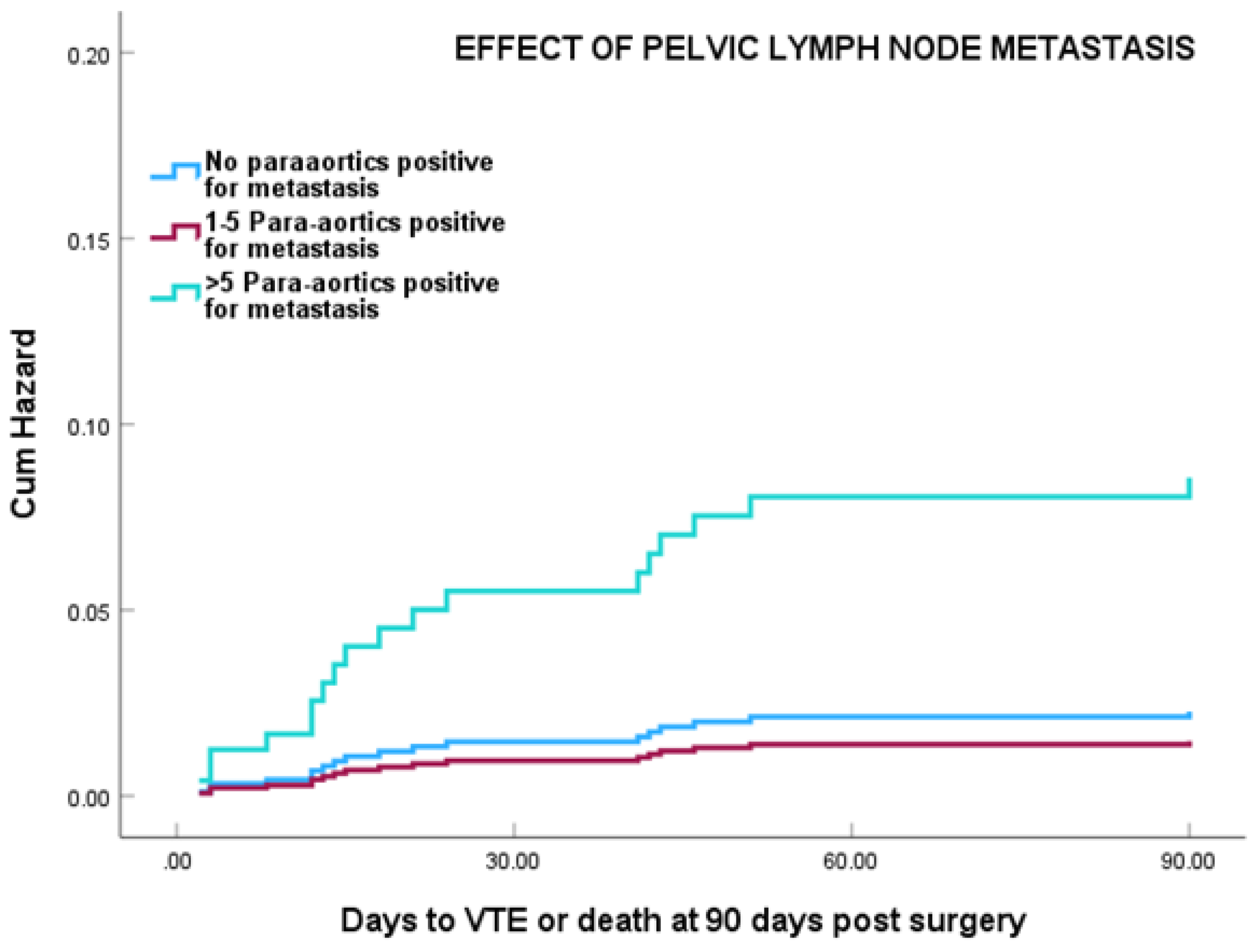

Cox regression analysis showed that patients with more than 5 para-aortic LN positive for metastasis showed a marked increased risk of VTE, particularly in the first 21 days post surgery HR 9.47 (95% CI 2.67-33.6) (P0.0001) (

Figure 3). This was still significant at HR=3.79 (95% CI 1.44-14.23) after adjustment for age, duration of hospital stay, and surgical approach (P= 0.011).

4. Discussion

Our study found that the site and the number of LND significantly influenced VTE risk in gynaecological cancer patients. Removing > 5 para-aortic nodes is associated with the highest risk. In contrast, the removal of pelvic LN was not significantly associated with VTE risk. Additionally, we found that the presence of metastasis in both para-aortic and pelvic LN was a significant risk factor for VTE even after adjustment for age, duration of hospital stay and surgical approach.

Our study demonstrates that para-aortic LND is a significant risk factor for VTE. This association can be explained through Virchow’s triad, which encompasses hypercoagulability, venous stasis, and vascular damage [

23]. Enlarged para-aortic LN exerts external pressure on vessels, leading to vascular stasis. Additionally, para-aortic LND involves operating near major vessels (aorta and inferior vena cava), which increases the risks of vascular injury, significant bleeding, and prolonged operative time [

24]. In a study of patients with endometrial cancer undergoing para-aortic LND, the rate of VTE was notably higher among patients who experienced vascular injury, excessive bleeding, or operative times exceeding 80 minutes [

24].

Our findings confirm the study of Konno et el who reported; 4.9% risk of VTE in patients undergoing pelvic and paraaortic LND compared to 2.2 % in patients undergoing only pelvic LND. This may be due to longer operation time (on average 226 minutes longer) and higher blood loss (~ 500ml) in cases including paraaortic LND [

25].

Our study further demonstrates that the presence of both pelvic and para-aortic LN metastasis significantly increases the risk of VTE. This elevated risk remains significant even after adjusting for tumour site, patient age, surgical approach, and duration of hospital stay. Metastasis in LN typically indicates an advanced cancer stages, such as stage III or higher, which is directly associated with an increased risk of thrombosis [

26]. Advanced cancer stage induces hypercoagulability and causes endothelial damage [

27]. Furthermore, LN metastases cause node enlargement, resulting in physical pressure on adjacent vessels and consequent venous stasis [

28]. We found an association between the number of metastatic LN and the risk of VTE. Though the effect was noted in both pelvic and paraaortic LND, it was more significant in paraaortic LND.

VTE remains a critical consideration in gynaecological cancer care, particularly in the postoperative setting. The evolution in surgical techniques, such as minimal access surgery and sentinel lymph node sampling, has reshaped clinical practices and raised questions about the necessity of extended thromboprophylaxis in certain patient groups. To address this issue effectively, understanding the pathophysiology of VTE and associated risk factors in gynaecological cancer is essential for tailoring prophylaxis to individual needs.

These findings provide valuable insights for cancer surgeons, enabling them to identify patients at the highest risk of postoperative VTE and implement targeted prophylactic measures.

There is ongoing controversy regarding the use of extended prophylaxis in minimally invasive surgery (MIS) cases, with no definitive guidelines to support or refute its use, leaving the decision to the surgeon's judgment [

29]. The risk of DVT is thought to be higher than PE in MIS patients who undergo LND [

30]. This can be attributed to the steep Trendelenburg position and the extended operative time required for LND, which increases the risk of blood stasis [

31]. Lateif et al. reported an increased risk of VTE associated with LND, regardless of the surgical approach, with LND carrying a 1.7-fold increased risk of VTE in gynaecologic cancer patients [

18]. However in prostate cancer, MIS is associated with only one-third the risk of VTE compared with open surgery [

19].

In our cohort, the majority of patients who developed VTE were already on extended thromboprophylaxis, suggesting that patients undergoing LND may require either higher doses or longer durations of prophylaxis as has been suggested by our previous studies [

32]. We cannot exclude the possibility that not all patients were compliant with extended prophylaxis, and it was also noted that patients with a lower quality of life were the least likely to adhere to extended prophylaxis. This underscores the importance of careful patient selection and individualized management.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) can be considered as an alternative to LMWH in patients facing adherence challenges. DOACs are effective for treating VTE in cancer patients and have recently been proposed as a safe alternative to LMWH for extended prophylaxis in high-risk cancer patients and studies suggest that an oral form of prophylaxis would be preferred by the patient [

33]. However, caution is required in elderly patients due to the increased risk of bleeding, particularly if they are also taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), antiplatelets, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [

34].

The interpretation of our study results must account for certain limitations. This was a single centre retrospective study, and as with all retrospective studies, there are inherent challenges such as missing data. However, it remains the largest published study specifically examining the role of LND and VTE. During the study, from 2006 to 2019, the surgical approach and extent of surgery have evolved, and we cannot exclude that the effects of changes in surgical practice over time may have influenced our results. Additionally, the possibility that some patients may have experienced asymptomatic VTE, which went undetected, cannot be excluded. We could not confirm patient adherence to extended thromboprophylaxis post-hospital discharge. Furthermore, comorbidities were not included in our statistical analysis, and we cannot rule out the possibility that differences in comorbid conditions between the cohorts may have influenced the findings. Future studies should address these limitations to provide a more comprehensive understanding.

5. Conclusions

para-aortic LND is significantly associated with an increased risk of VTE. The presence of metastatic LN further elevates this risk, although determining LN metastasis status intraoperatively remains challenging, we recommend that patients undergoing para-aortic LND, receive extended thromboprophylaxis. Further studies are warranted to determine the optimal dose and duration of thromboprophylaxis, as high-risk cohorts may benefit from weight-adjusted dosing to effectively reduce VTE risk [

32].

References

- Fernandes CJ, Morinaga LT, Alves Jr JL, Castro MA, Calderaro D, Jardim CV, et al. Cancer-associated thrombosis: the when, how and why. European Respiratory Review. 2019;28(151).

- Abu Saadeh, F.; Norris, L.; O’tOole, S.; Gleeson, N. Venous thromboembolism in ovarian cancer: incidence, risk factors and impact on survival. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2013, 170, 214–218. [CrossRef]

- Barbera L, Thomas G. Venous thromboembolism in cervical cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(1):54-60.

- Pin, S.; Mateshaytis, J.; Ghosh, S.; Batuyong, E.; Easaw, J. Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism in Endometrial Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2020, 27, 198–203. [CrossRef]

- Peedicayil, A.; Weaver, A.; Li, X.; Carey, E.; Cliby, W.; Mariani, A. Incidence and timing of venous thromboembolism after surgery for gynecological cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 121, 64–69. [CrossRef]

- Falanga, A.; Ay, C.; Di Nisio, M.; Gerotziafas, G.; Jara-Palomares, L.; Langer, F.; Lecumberri, R.; Mandala, M.; Maraveyas, A.; Pabinger, I.; et al. Venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 452–467. [CrossRef]

- Guo Q, Huang B, Zhao J, Ma Y, Yuan D, Yang Y, et al. Perioperative pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of surgery. 2017;265(6):1087-93.

- Bouchard-Fortier, G.; Geerts, W.H.; Covens, A.; Vicus, D.; Kupets, R.; Gien, L.T. Is venous thromboprophylaxis necessary in patients undergoing minimally invasive surgery for a gynecologic malignancy?. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 134, 228–232. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Mills, K.A.; Fehniger, J.; Liao, C.; Hurteau, J.A.; Kirschner, C.V.; Lee, N.K.; Rodriguez, G.C.; Yamada, S.D.; Moore, E.S.D.; et al. Venous Thromboembolism in Patients Receiving Extended Pharmacologic Prophylaxis After Robotic Surgery for Endometrial Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 1774–1782. [CrossRef]

- Kahr, H.S.; Christiansen, O.B.; Høgdall, C.; Grove, A.; Mortensen, R.N.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Knudsen, A.; Thorlacius-Ussing, O. Endometrial cancer does not increase the 30-day risk of venous thromboembolism following hysterectomy compared to benign disease. A Danish National Cohort Study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 155, 112–118. [CrossRef]

- Concin, N.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Vergote, I.; Cibula, D.; Mirza, M.R.; Marnitz, S.; Ledermann, J.; Bosse, T.; Chargari, C.; Fagotti, A.; et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 12–39. [CrossRef]

- Chiyoda, T.; Sakurai, M.; Satoh, T.; Nagase, S.; Mikami, M.; Katabuchi, H.; Aoki, D. Lymphadenectomy for primary ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 31, e67. [CrossRef]

- Tzanis, A.A.; Antoniou, S.A.; Zacharoulis, D.; Ntafopoulos, K.; Tsouvali, H.; Daponte, A. The role of systematic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in the management of patients with advanced epithelial ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2023, 285, 198–203. [CrossRef]

- Harter, P.; Sehouli, J.; Lorusso, D.; Reuss, A.; Vergote, I.; Marth, C.; Kim, J.W.; Raspagliesi, F.; Lampe, B.; Landoni, F.; et al. LION: Lymphadenectomy in ovarian neoplasms—A prospective randomized AGO study group led gynecologic cancer intergroup trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 5500. [CrossRef]

- Oonk, M.H.; Planchamp, F.; Baldwin, P.; Bidzinski, M.; Brännström, M.; Landoni, F.; Mahner, S.; Mahantshetty, U.; Mirza, M.; Petersen, C.; et al. European Society of Gynaecological Oncology Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Vulvar Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 832–837. [CrossRef]

- van Es, N.; Di Nisio, M.; Cesarman, G.; Kleinjan, A.; Otten, H.M.; Mahé, I.; Wilts, I.T.; Twint, D.C.; Porreca, E.; Arrieta, O.; et al. Comparison of risk prediction scores for venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: A prospective cohort study. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1494–1501. [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.C.; Papa, N.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Bolton, D.; Sengupta, S. Incidence and risk factors of venous thromboembolism after pelvic uro-oncologic surgery – a single center experience. BJU Int. 2015, 117, 50–53. [CrossRef]

- Latif, N.; Oh, J.; Brensinger, C.; Morgan, M.; Lin, L.L.; Cory, L.; Ko, E.M. Lymphadenectomy is associated with an increased risk of postoperative venous thromboembolism in early stage endometrial cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 130–134. [CrossRef]

- Tyritzis, S.I.; Wallerstedt, A.; Steineck, G.; Nyberg, T.; Hugosson, J.; Bjartell, A.; Wilderäng, U.; Thorsteinsdottir, T.; Carlsson, S.; Stranne, J.; et al. Thromboembolic Complications in 3,544 Patients Undergoing Radical Prostatectomy with or without Lymph Node Dissection. J. Urol. 2015, 193, 117–125. [CrossRef]

- Lyman, G.H.; Carrier, M.; Ay, C.; Di Nisio, M.; Hicks, L.K.; Khorana, A.A.; Leavitt, A.D.; Lee, A.Y.Y.; Macbeth, F.; Morgan, R.L.; et al. American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prevention and treatment in patients with cancer. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 927–974. [CrossRef]

- Prat J, Oncology ftFCoG. Staging Classification for Cancer of the Ovary, Fallopian Tube, and Peritoneum: Abridged Republication of Guidelines From the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2015;126(1):171-4.

- Aletti, G.; Dowdy, S.C.; Podratz, K.C.; Cliby, W.A. Relationship among surgical complexity, short-term morbidity, and overall survival in primary surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 197, 676.e1–676.e7. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.R.; Hanlin, E.; Glurich, I.; Mazza, J.J.; Yale, S.H. Virchow's Contribution to the Understanding of Thrombosis and Cellular Biology. Clin. Med. Res. 2010, 8, 168–172. [CrossRef]

- Chai X, Zhu T, Chen Z, Zhang H, Wu X. Improvements and challenges in intraperitoneal laparoscopic para-aortic lymphadenectomy: The novel “tent-pitching” antegrade approach and vascular anatomical variations in the para-aortic region. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2024;103(9):1753-63.

- Konno, Y.; Todo, Y.; Minobe, S.; Kato, H.; Okamoto, K.; Sudo, S.; Takeda, M.; Watari, H.; Kaneuchi, M.; Sakuragi, N. A Retrospective Analysis of Postoperative Complications With or Without Para-aortic Lymphadenectomy in Endometrial Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2011, 21, 385–390. [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, H.; Shimada, M.; Osaku, D.; Deura, I.; Sato, S.; Oishi, T.; Harada, T. Deep vein thrombosis and serum D-dimer after pelvic lymphadenectomy in gynecological cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 860–864. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Guo, L.; Wu, L.; Hu, T. Relationship between Hypercoagulable State and Circulating Tumor Cells in Peripheral Blood, Pathological Characteristics, and Prognosis of Lung Cancer Patients. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- D'ANdrea, V.; Qian, Z.(.; Yim, K.; Egan, J.; Magnani, C.J.; Feldman, A.; Salari, K.; Tewari, A.; Steele, G.; Mossanen, M.; et al. Anticoagulation prophylaxis patterns following retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for testis cancer. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2023, 41, 489.e1–489.e6. [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, H.; Aljebori, Q.; Lockart, D.; Moulton, L. Risk of Venous Thromboembolism After Laparoscopic Surgery for Gynecologic Malignancy. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2016, 23, 1057–1062. [CrossRef]

- Ackroyd, S.; Rubin, S.; Houck, K.; Chu, C.; Mantia-Smaldone, G.; Hernandez, E. Lymph node dissection at the time of hysterectomy for uterine cancer is associated with venous thromboembolism: An analysis of the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 159, 326–327. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Cronan, M.; Braley, S.; Rivers, R.; Wolfe, B. Duplex ultrasound assessment of femoral venous flow during laparoscopic and open gastric bypass. Surg. Endosc. 2003, 17, 285–290. [CrossRef]

- Abu Saadeh, F.; Marchocki, Z.; O'TOole, S.; Ibrahim, N.; Gleeson, N.; Norris, L. Extended thromboprophylaxis post gynaecological cancer surgery; the effect of weight adjusted and fixed dose LMWH (Tinzaparin). Thromb. Res. 2021, 207, 25–32. [CrossRef]

- Marchocki, Z.; Norris, L.; O'TOole, S.; Gleeson, N.; Abu Saadeh, F. Patients’ experience and compliance with extended low molecular weight heparin prophylaxis post-surgery for gynecological cancer: a prospective observational study. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29, 802–809. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Oh, I.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kwon, S.S.; Yang, H.-J.; Kim, Y.-K.; Bang, S.-M. The increased risk of bleeding due to drug-drug interactions in patients administered direct oral anticoagulants. Thromb. Res. 2020, 195, 243–249. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).