Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

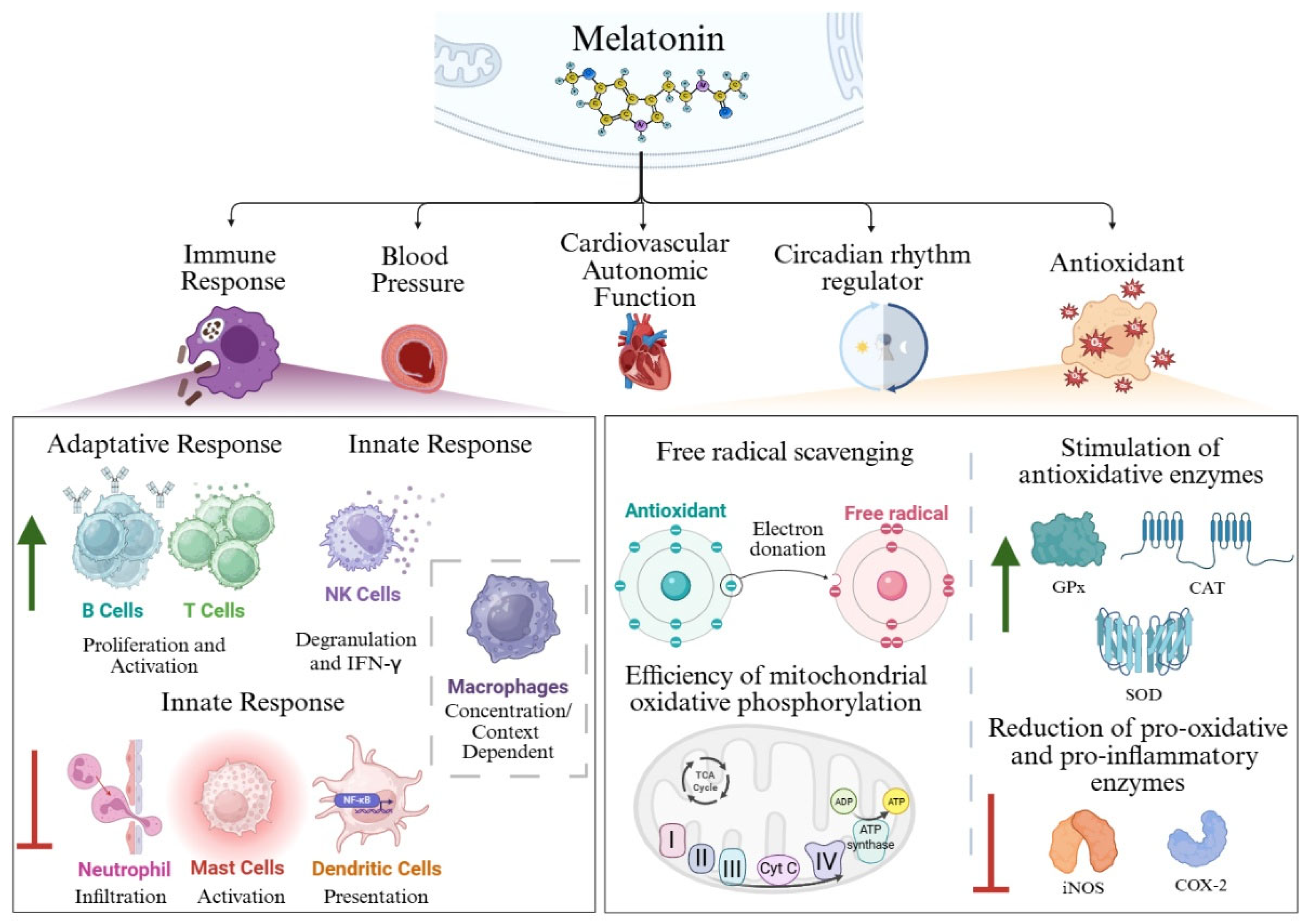

2. Antioxidant Function of Melatonin

2.1. Free radical Scavenging

2.2. Stimulation of Antioxidative Enzymes

2.3. Efficiency of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation

3. Immunomodulatory and Anti-inflammatory Actions of Melatonin

3.1. Adaptative Immune Response

3.1.1. T Cells

3.1.2. B Cells

3.2. Innate Immune Response.

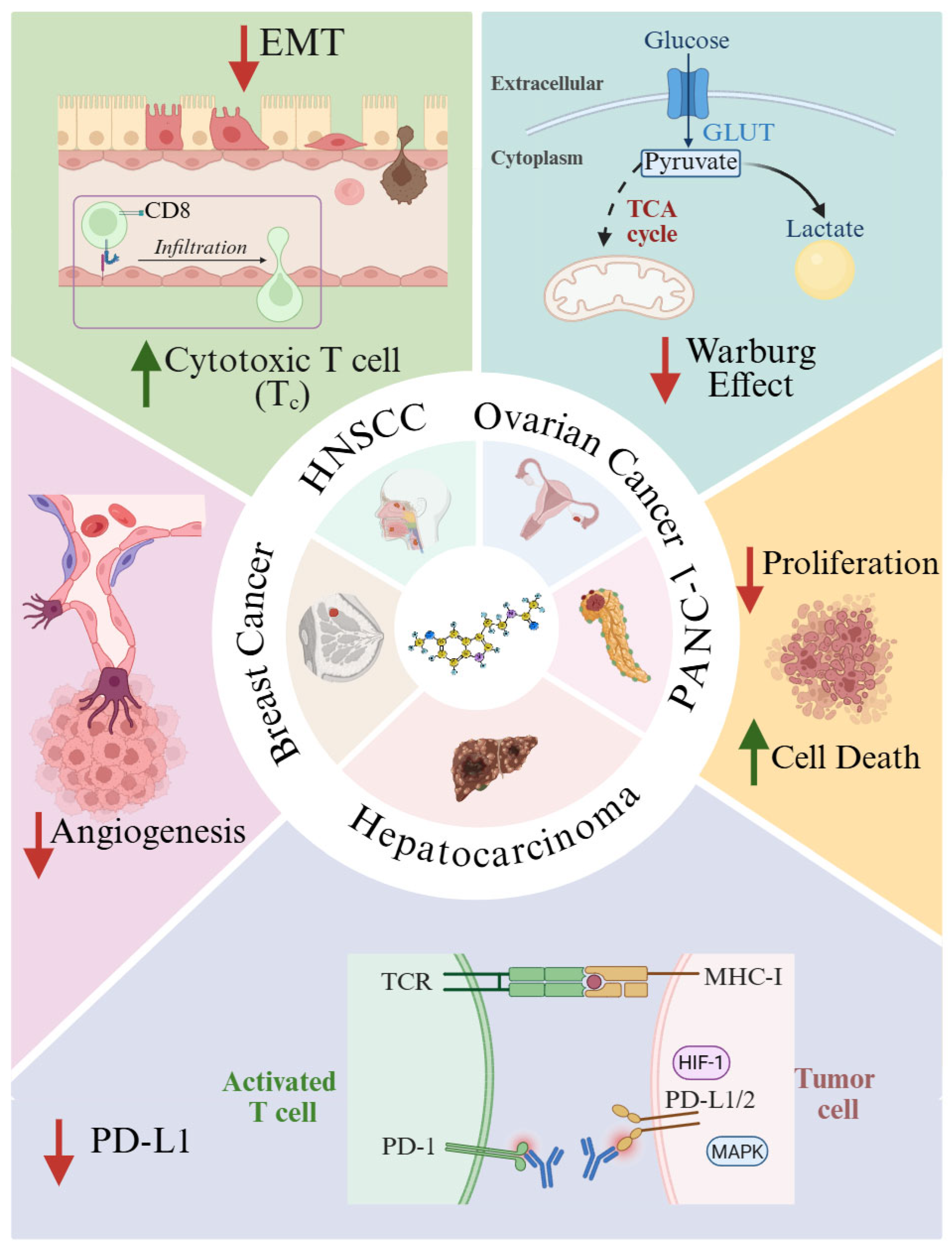

4. Melatonin in Cancer: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential

5. Modulation of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment

- Elimination. Innate and adaptive immune components act to eradicate emerging tumor cells.

- Equilibrium. Tumor cells with low immunogenicity survive immune pressure and continue unchecked proliferation.

- Escape. Tumor cells downregulate major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) expression, impairing immune recognition and culminating in the emergence of clinically detectable tumors.

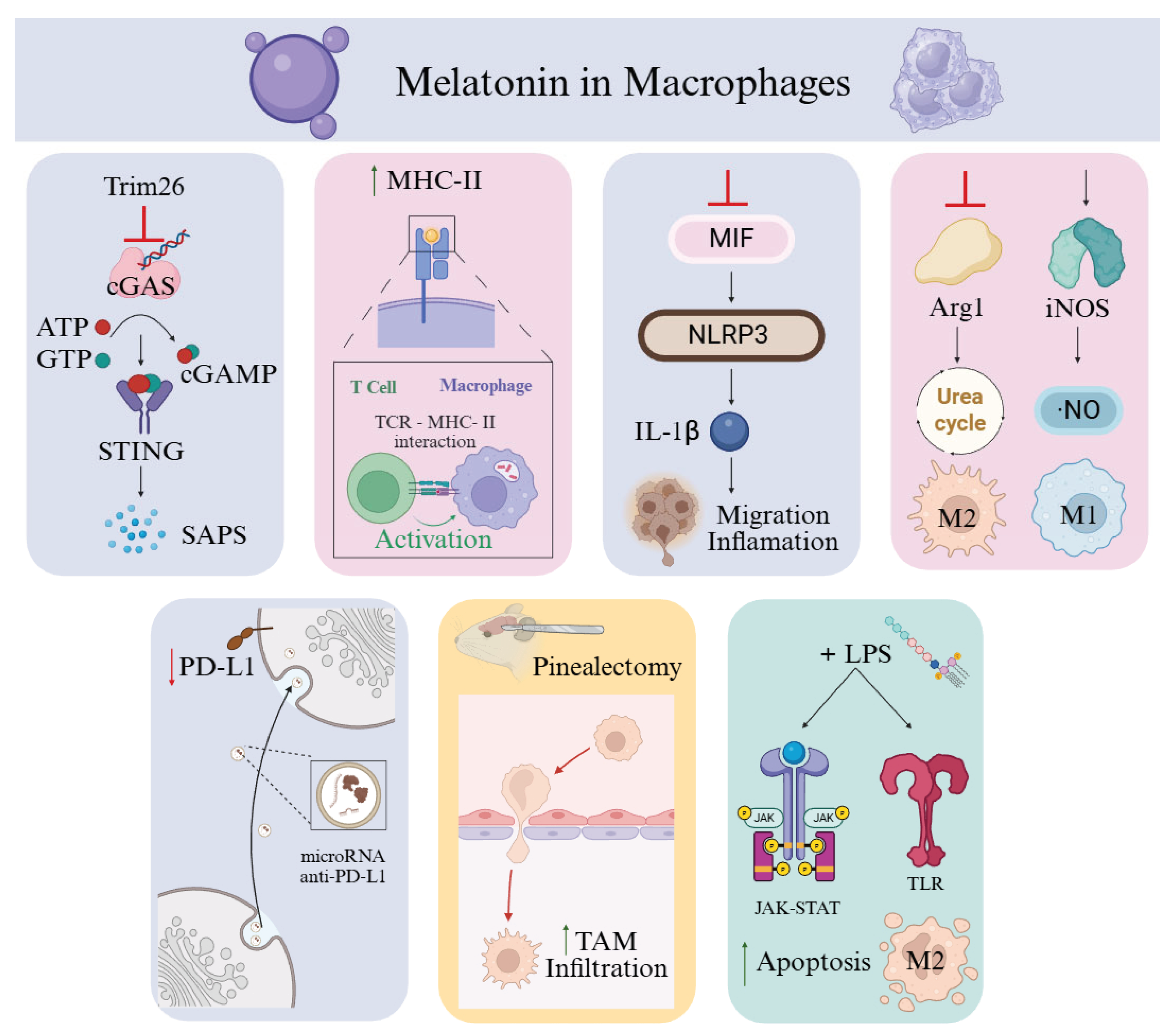

6. Macrophages as a Therapeutic Target of Melatonin in Cancer

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AANAT | Aralkylamine N-Acetyltransferase |

| ABST | 2,2′-Azino-Bis(3-Ethylbenzthiazoline-6-Sulfonic Acid) |

| ADCC | Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity |

| AFMK | N-Acetyl-N-Formyl-5-Methoxyquinuramine |

| AMK | N-Acetyl-5-Methoxyquinuramine |

| Arg1 | Arginase 1 |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| Bcl-2 | B-Cell Lymphoma 2 |

| BCR | B Cell Receptor |

| bFGF | Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| BMAL1 | Brain And Muscle ARNT-Like Protein 1 |

| BReg | Regulatory B Cells |

| CAFs | Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts |

| CAT | Catalase |

| cGAMP | Cyclic GMP–AMP |

| cGAS | Cyclic GMP–AMP Synthase |

| CD8 | Cluster Of Differentiation 8 (Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Marker) |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CRF | Cancer-Related Fatigue |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 12 |

| Cyt C | Cytochrome C |

| DC | Dendritic Cells |

| EAE | Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis |

| EC | Endothelial Cells |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition |

| ERK1/2–FOSL1 | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinases 1 And 2 – Fos-Like Antigen 1 |

| FasL | Fas Ligand (CD95 Ligand) |

| GLUT | Glucose Transporter |

| GLUT1 | Glucose Transporter 1 |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte–Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| GPx | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| GR | Glutathione Reductase |

| GSH | Reduced Glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized Glutathione |

| GTP | Guanosine Triphosphate |

| GzmB | Granzyme B |

| HIF | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor |

| HNSCC | Head And Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| HUVECs | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| JAK-STAT | Janus Kinase And Signal Transducer And Activator Of Transcription |

| Ki67 | Proliferation Marker Protein Ki-67 |

| KIR | Killer Immunoglobulin-Like Receptors |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MCF-7 | Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells |

| MHC-I/II | Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I/II |

| MiaPaCa-2 | Human Pancreatic Cancer |

| MIF | Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor |

| MT1R | Melatonin Receptor Type 1 |

| NKG2D | Natural Killer Group 2, Member D |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| NKp30 | Natural Killer Cell P30-Related Protein (NCR3) |

| NLRP3 | NOD-Like Receptor Family Pyrin Domain-Containing 3 |

| ·NO | Nitric Oxide Radical |

| ·NO/NO | Nitric Oxide |

| O2- | Superoxide Anions |

| ·OH | Hydroxyl Radicals |

| ONOO- | Peroxynitrite Anions |

| PANC-1 | Human Pancreatic Carcinoma Cell Line |

| PCNA | Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen |

| PDC | Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PDCA | Programmed Cell Death Activator |

| PDGFC | Platelet Derived Growth Factor C |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PD-L1/2 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1/2 |

| PEPT1/2 | Peptide Transporter 1/2 |

| RFA | Radiofrequency Ablation |

| RNS | Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| ROR-α | Retinoic Acid-Related Orphan Receptor Alpha |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RZR-β | Orphan Receptor Retinoid Z Receptor Beta |

| SAPS | Serum Amyloid P Component |

| SIRT3 | Stimulates Sirtuin 3 |

| siRNA | Small Interfering RNA |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| STRING | Search Tool For The Retrieval Of Interacting Genes/Proteins |

| TAM | Tumor-Associated Macrophage |

| TANs | Tumor-Associated Neutrophils |

| TCA Cycle | Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle (Krebs Cycle) |

| TCR | T-Cell Receptor |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| THP-1 Cells | Human Monocytic Cell Line Derived From A Patient With Acute Monocytic Leukemia |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| TRAIL | TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand |

| TRIM26 | Tripartite Motif-Containing Protein 26 |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cells |

| TSCM | Memory Stem T Cells |

| TFH | Follicular Memory T Cells |

| TEM | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TEM | Effector Memory T Cells |

| TM | Memory T Cells |

| TRM | Resident Memory T Cells |

| UCP | Uncoupling Proteins |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| VEGFA | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A |

| Δψ | Membrane Potential |

| ¹O₂ | Singlet Oxygen |

References

- Minich, D. M.; Henning, M.; Darley, C.; Fahoum, M.; Schuler, C. B.; Frame, J. Is Melatonin the “Next Vitamin D”?: A Review of Emerging Science, Clinical Uses, Safety, and Dietary Supplements. Nutrients. MDPI October 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, A. B.; Case, J. D.; Takahashi, Y.; Lee, T. H.; Mori, W. ISOLATION OF MELATONIN, THE PINEAL GLAND FACTOR THAT LIGHTENS MELANOCYTES1. J Am Chem Soc 2002. 80 (10), 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LERNER, A. B.; CASE, J. D.; TAKAHASHI, Y. Isolation of Melatonin and 5-Methoxyindole-3-Acetic Acid from Bovine Pineal Glands. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1960, 235 (7), 1992–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, A. B.; Case, J. D.; Mori, W.; Wright, M. R. Melatonin in Peripheral Nerve. Nature 1959, 183 (4678). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D. X.; Manchester, L. C.; Esteban-Zubero, E.; Zhou, Z.; Reiter, R. J. Melatonin as a Potent and Inducible Endogenous Antioxidant: Synthesis and Metabolism. Molecules, MDPI AG October 2015, pp 18886–18906. [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R. J.; Mayo, J. C.; Tan, D. X.; Sainz, R. M.; Alatorre-Jimenez, M.; Qin, L. Melatonin as an Antioxidant: Under Promises but over Delivers. J Pineal Res 2016, 61, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R. J.; Sharma, R. N.; Chuffa, L. G. de A.; Silva, D. G. H. da; Rosales-Corral, S. Intrinsically Synthesized Melatonin in Mitochondria and Factors Controlling Its Production. Histology and Histopathology, Histology and Histopathology March 2025, pp 271–282. [CrossRef]

- Arnao, M. B.; Giraldo-Acosta, M.; Castejón-Castillejo, A.; Losada-Lorán, M.; Sánchez-Herrerías, P.; El Mihyaoui, A.; Cano, A.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Melatonin from Microorganisms, Algae, and Plants as Possible Alternatives to Synthetic Melatonin. Metabolites 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Choi, G. H.; Back, K. Functional Characterization of Serotonin N-Acetyltransferase in Archaeon Thermoplasma Volcanium. Antioxidants 2022, 11(3), 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Kurth, S.; Pugin, B.; Bokulich, N. A. Microbial Melatonin Metabolism in the Human Intestine as a Therapeutic Target for Dysbiosis and Rhythm Disorders. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordjman, S.; Chokron, S.; Delorme, R.; Charrier, A.; Bellissant, E.; Jaafari, N.; Fougerou, C. Melatonin: Pharmacology, Functions and Therapeutic Benefits. Curr Neuropharmacol 2017, 15, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Sharma, R.; Reiter, R. J. Melatonin Synthesis and Function: Evolutionary History in Animals and Plants. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2019, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieri, C.; Marra, M.; Moroni, F.; Recchioni, R.; Marcheselli, F. Melatonin: A Peroxyl Radical Scavenger More Effective than Vitamin E. Life Sci 1994, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R. J.; Carneiro, R. C.; Oh, C. S. Melatonin in Relation to Cellular Antioxidative Defense Mechanisms. Hormone and Metabolic Research, Georg Thieme Verlag 1997, pp 363–372. [CrossRef]

- Poeggeler, B.; Thuermann, S.; Dose, A.; Schoenke, M.; Burkhardt, S.; Hardeland, R. Melatonin’s Unique Radical Scavenging Properties – Roles of Its Functional Substituents as Revealed by a Comparison with Its Structural Analogs. J Pineal Res 2002, 33, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S. B.; Ali, A.; Bilal, M.; Rashid, S. M.; Wani, A. B.; Bhat, R. R.; Rehman, M. U. Melatonin and Health: Insights of Melatonin Action, Biological Functions, and Associated Disorders. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, Springer August 2023, pp 2437–2458. [CrossRef]

- Calvo, J. R.; Maldonado, M. D. Immunoregulatory Properties of Melatonin in the Humoral Immune System: A Narrative Review. Immunol Lett 2024, 269, 106901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajwa, V. S.; Shukla, M. R.; Sherif, S. M.; Murch, S. J.; Saxena, P. K. Role of Melatonin in Alleviating Cold Stress in Arabidopsis Thaliana. J Pineal Res 2014, 56, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitimus, D. M.; Popescu, M. R.; Voiculescu, S. E.; Panaitescu, A. M.; Pavel, B.; Zagrean, L.; Zagrean, A. M. Melatonin’s Impact on Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Reprogramming in Homeostasis and Disease. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Xin, Y.; Hou, Y.; Xiang, X.; Deng, Y.; Yang, B.; Yu, W. Melatonin-Derived Carbon Dots with Free Radical Scavenging Property for Effective Periodontitis Treatment via the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 8307–8324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Reiter, R.; Manchester, L.; Yan, M.; El-Sawi, M.; Sainz, R.; Mayo, J.; Kohen, R.; Allegra, M.; Hardelan, R. Chemical and Physical Properties and Potential Mechanisms: Melatonin as a Broad Spectrum Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenger. Curr Top Med Chem 2005, 2, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, C. E.; Steketee, J. D.; Saphier, D. Antioxidant Properties of Melatonin—an Emerging Mystery. Biochem Pharmacol 1998, 56, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocheva, G.; Bakalov, D.; Iliev, P.; Tafradjiiska-Hadjiolova, R. The Vital Role of Melatonin and Its Metabolites in the Neuroprotection and Retardation of Brain Aging. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafati-Chaleshtori, R.; Shirzad, H.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M.; Soltani, A. Melatonin and Human Mitochondrial Diseases. J Res Med Sci 2017, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, Y.; Honma, S.; Goto, S.; Todoroki, S.; Iida, T.; Cho, S.; Honma, K.; Kondo, T. Melatonin Induces γ-Glutamylcysteine Synthetase Mediated by Activator Protein-1 in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999, 27 (7–8), 838–847. [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R. J.; Rosales-Corral, S.; Tan, D. X.; Jou, M. J.; Galano, A.; Xu, B. Melatonin as a Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant: One of Evolution’s Best Ideas. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, Birkhauser Verlag AG November 2017, pp 3863–3881. [CrossRef]

- Suofu, Y.; Li, W.; Jean-Alphonse, F. G.; Jia, J.; Khattar, N. K.; Li, J.; Baranov, S. V.; Leronni, D.; Mihalik, A. C.; He, Y.; Cecon, E.; Wehbi, V. L.; Kim, J. H.; Heath, B. E.; Baranova, O. V.; Wang, X.; Gable, M. J.; Kretz, E. S.; Di Benedetto, G.; Lezon, T. R.; Ferrando, L. M.; Larkin, T. M.; Sullivan, M.; Yablonska, S.; Wang, J.; Minnigh, M. B.; Guillaumet, G.; Suzenet, F.; Richardson, R. M.; Poloyac, S. M.; Stolz, D. B.; Jockers, R.; Witt-Enderby, P. A.; Carlisle, D. L.; Vilardaga, J. P.; Friedlander, R. M. Dual Role of Mitochondria in Producing Melatonin and Driving GPCR Signaling to Block Cytochrome c Release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E7997–E8006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D. X.; Manchester, L. C.; Qin, L.; Reiter, R. J. Melatonin: A Mitochondrial Targeting Molecule Involving Mitochondrial Protection and Dynamics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. MDPI AG December 2016. [CrossRef]

- Galano, A.; Medina, M. E.; Tan, D. X.; Reiter, R. J. Melatonin and Its Metabolites as Copper Chelating Agents and Their Role in Inhibiting Oxidative Stress: A Physicochemical Analysis. J Pineal Res 2015, 58, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galano, A.; Tan, D. X.; Reiter, R. J. On the Free Radical Scavenging Activities of Melatonin’s Metabolites, AFMK and AMK. J Pineal Res 2013, 54, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. M.; Zhang, Y. Melatonin: A Well-Documented Antioxidant with Conditional pro-Oxidant Actions. Journal of Pineal Research, 2014, pp 131–146. [CrossRef]

- POEGGELER, B.; SAARELA, S.; REITER, R. J.; TAN, D. -X; CHEN, L. -D; MANCHESTER, L. C.; BARLOW-WALDEN, L. R. Melatonin--a Highly Potent Endogenous Radical Scavenger and Electron Donor: New Aspects of the Oxidation Chemistry of This Indole Accessed in Vitro. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1994, 738, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, K. K. A. C.; Shiroma, M. E.; Damous, L. L.; Simões, M. de J.; Simões, R. dos S.; Cipolla-Neto, J.; Baracat, E. C.; Soares-Jr, J. M. Antioxidant Actions of Melatonin: A Systematic Review of Animal Studies. Antioxidants 2024, Vol. 13, Page 439 2024, 13. (4), 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C. K.; Chhabra, G.; Ndiaye, M. A.; Garcia-Peterson, L. M.; MacK, N. J.; Ahmad, N. The Role of Sirtuins in Antioxidant and Redox Signaling. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling, Mary Ann Liebert Inc. March 2018, pp 643–661. [CrossRef]

- Urata, Y.; Honma, S.; Goto, S.; Todoroki, S.; Iida, T.; Cho, S.; Honma, K.; Kondo, T. Melatonin Induces γ-Glutamylcysteine Synthetase Mediated by Activator Protein-1 in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells. Free Radic Biol Med 1999, 27, (7–8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okatani, Y.; Wakatsuki, A.; Reiter, R. J.; Enzan, H.; Miyahara, Y. Protective Effect of Melatonin against Mitochondrial Injury Induced by Ischemia and Reperfusion of Rat Liver. Eur J Pharmacol 2003, 469, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.; Ustoyev, Y. Cancer and the Immune System: The History and Background of Immunotherapy. Semin Oncol Nurs 2019, 35. (5), 150923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillion, S.; Arleevskaya, M. I.; Blanco, P.; Bordron, A.; Brooks, W. H.; Cesbron, J. Y.; Kaveri, S.; Vivier, E.; Renaudineau, Y. The Innate Part of the Adaptive Immune System. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology, Springer April 2020, pp 151–154. [CrossRef]

- Ruterbusch, M.; Pruner, K. B.; Shehata, L.; Pepper, M. In Vivo CD4+ T Cell Differentiation and Function: Revisiting the Th1/Th2 Paradigm. Annual Review of Immunology, Annual Reviews Inc. April 2020, pp 705–725. [CrossRef]

- Zefferino, R.; Di Gioia, S.; Conese, M. Molecular Links between Endocrine, Nervous and Immune System during Chronic Stress. Brain and Behavior. John Wiley and Sons Ltd February 2021. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühlwein, E.; Irwin, M. Melatonin Modulation of Lymphocyte Proliferation and Th1/Th2 Cytokine Expression. J Neuroimmunol 2001, 117, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestroni, G. J. M.; Conti, A.; Pierpaoli, W. Role of the Pineal Gland in Immunity. Circadian Synthesis and Release of Melatonin Modulates the Antibody Response and Antagonizes the Immunosuppressive Effect of Corticosterone. J Neuroimmunol 1986, 13, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelzer, I. A.; Arck, P. C. Immunity and the Endocrine System. In Encyclopedia of Immunobiology; Elsevier Inc., 2016; Vol. 5, pp 73–85. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Su, Y.; Jiao, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B. T Cells in Health and Disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. Springer Nature December 2023. [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Vico, A.; Lardone, P. J.; Álvarez-Śnchez, N.; Rodrĩguez-Rodrĩguez, A.; Guerrero, J. M. Melatonin: Buffering the Immune System. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14. (4), 8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Liu, G.; Chen, S.; Yin, J.; Wang, J.; Tan, B.; Wu, G.; Bazer, F. W.; Peng, Y.; Li, T.; Reiter, R. J.; Yin, Y. Melatonin Signaling in T Cells: Functions and Applications. J Pineal Res 2017, 62. (3), e12394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaji, A. V.; Kulkarni, S. K.; Agrewala, J. N. Regulation of Secretion of IL-4 and IgG1 Isotype by Melatonin-Stimulated Ovalbumin-Specific T Cells. Clin Exp Immunol 1998, 111, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Niu, C.; Sun, C.; Ma, Y.; Guo, R.; Ruan, Z.; Gao, Y.; Lu, X.; Li, H.; Lin, Y.; Lin, J.; Li, Z. Melatonin Exerts Immunoregulatory Effects by Balancing Peripheral Effector and Regulatory T Helper Cells in Myasthenia Gravis. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12. (21), 21147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Araghi-Niknam, M.; Liang, B.; Inserra, P.; Ardestani, S. K.; Jiang, S.; Chow, S.; Watson, R. R. Prevention of Immune Dysfunction and Vitamin E Loss by Dehydroepiandrosterone and Melatonin Supplementation during Murine Retrovirus Infection. Immunology 1999, 96, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künzli, M.; Masopust, D. CD4+ T Cell Memory. Nat Immunol 2023, 24. (6), 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Sánchez, N.; Cruz-Chamorro, I.; López-González, A.; Utrilla, J. C.; Fernández-Santos, J. M.; Martínez-López, A.; Lardone, P. J.; Guerrero, J. M.; Carrillo-Vico, A. Melatonin Controls Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Altering the T Effector/Regulatory Balance. Brain Behav Immun 2015, 50, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, R. L. E.; Lopera, H. D. E. Introduction to T and B Lymphocytes. 2013.

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Burrows, P. D.; Wang, J. Y. B Cell Development and Maturation. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer, 2020; Vol. 1254, pp 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Miller, S. C.; Osmond, D. G. Melatonin Inhibits Apoptosis during Early B-Cell Development in Mouse Bone Marrow. J Pineal Res 2000, 29, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Song, J.; Chen, X.; Huang, J.; Lin, X.; Zhou, R. Effect of Melatonin on T/B Cell Activation and Immune Regulation in Pinealectomy Mice. Life Sci 2020, 242, 117191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Song, R.; Zhang, J.; Yao, J.; Guan, Z.; Zeng, X. Melatonin Enhances NK Cell Function in Aged Mice by Increasing T-Bet Expression via the JAK3-STAT5 Signaling Pathway. Immunity and Ageing 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, E. M. Human Natural Killer Cells: Form, Function, and Development. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantoni, C.; Falco, M.; Vitale, M.; Pietra, G.; Munari, E.; Pende, D.; Mingari, M. C.; Sivori, S.; Moretta, L. Human NK Cells and Cancer. Oncoimmunology 2024, 13. (1), 2378520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krystel-Whittemore, M.; Dileepan, K. N.; Wood, J. G. Mast Cell: A Multi-Functional Master Cell. Front Immunol 2016, 6. (JAN), 165675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, C.; Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Han, D.; Gu, Q.; Su, R.; Liu, Y.; Reiter, R. J.; Liu, G.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H. Melatonin Alleviates Lung Injury in H1N1-Infected Mice by Mast Cell Inactivation and Cytokine Storm Suppression. PLoS Pathog 2023, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K. Dendritic Cells. Encyclopedia of Cell Biology 2015, 3, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. H.; Hong, Z. J.; Chen, M. F.; Tsai, M. W.; Chen, S. J.; Cheng, C. P.; Sytwu, H. K.; Lin, G. J. Melatonin Inhibits the Formation of Chemically Induced Experimental Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis through Modulation of T Cell Differentiation by Suppressing of NF-ΚB Activation in Dendritic Cells. Int Immunopharmacol 2024, 126, 111300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungelrath, V.; Kobayashi, S. D.; DeLeo, F. R. Neutrophils in Innate Immunity and Systems Biology-Level Approaches: An Update. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 2019, 12. (1), e1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, S. H.; Hsu, H. H.; Huang, S. Y.; Chen, Y. N.; Chen, L. Y.; Lee, A. H.; Lee, A. C.; Lee, E. J. Melatonin Promotes B-Cell Maturation and Attenuates Post-Ischemic Immunodeficiency in a Murine Model of Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A. F. U. H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G. G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in Immunoregulation and Therapeutics. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunna, C.; Mengru, H.; Lei, W.; Weidong, C. Macrophage M1/M2 Polarization. European Journal of Pharmacology. Elsevier B.V. June 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Tumor Immunity. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 583084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Pergañeda, A.; Guerrero, J. M.; Rafii-El-Idrissi, M.; Paz Romero, M.; Pozo, D.; Calvo, J. R. Characterization of Membrane Melatonin Receptor in Mouse Peritoneal Macrophages: Inhibition of Adenylyl Cyclase by a Pertussis Toxin-Sensitive G Protein. J Neuroimmunol 1999, 95, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, S.; Zeng, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Deng, B.; Zhu, G.; Yin, Y.; Wang, W.; Hardeland, R.; Ren, W. Melatonin in Macrophage Biology: Current Understanding and Future Perspectives. J Pineal Res 2019, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Choi, W. S. Use of Melatonin in Cancer Treatment: Where Are We? MDPI April. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. MDPI April 2022. [CrossRef]

- Morrey, K. M.; McLachlan, J. A.; Serkin, C. D.; Bakouche, O. Activation of Human Monocytes by the Pineal Hormone Melatonin. J Immunol 1994, 153, 2671–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muxel, S. M.; Pires-Lapa, M. A.; Monteiro, A. W. A.; Cecon, E.; Tamura, E. K.; Floeter-Winter, L. M.; Markus, R. P. NF-ΚB Drives the Synthesis of Melatonin in RAW 264.7 Macrophages by Inducing the Transcription of the Arylalkylamine-N-Acetyltransferase (AA-NAT) Gene. PLoS One 2012, 7. (12), e52010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, W.; Pan, K.; Tao, L.; Zhu, Y. Melatonin Induces RAW264.7 Cell Apoptosis via the BMAL1/ROS/MAPK-P38 Pathway to Improve Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Bone Joint Res 2023, 12, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Today. https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/en/dataviz/bars?types=0_1&mode=population (accessed 2025-09-30).

- Schwartz, S. M. Epidemiology of Cancer. Clin Chem 2024, 70, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, S. H.; Dehghani, M. Review of Cancer from Perspective of Molecular. Journal of Cancer Research and Practice 2017, 4, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaupel, P.; Multhoff, G.; Bennet, L.; Chan, J.; Vaupel, P.; Multhoff, G.; Physiol, J. Revisiting the Warburg Effect: Historical Dogma versus Current Understanding. J Physiol 2021, 599, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laborda-Illanes, A.; Sánchez-Alcoholado, L.; Castellano-Castillo, D.; Boutriq, S.; Plaza-Andrades, I.; Aranega-Martín, L.; Peralta-Linero, J.; Alba, E.; González-González, A.; Queipo-Ortuño, M. I. Development of in Vitro and in Vivo Tools to Evaluate the Antiangiogenic Potential of Melatonin to Neutralize the Angiogenic Effects of VEGF and Breast Cancer Cells: CAM Assay and 3D Endothelial Cell Spheroids. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 157, 114041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppa, L.; Aguzzi, C.; Morelli, M. B.; Marinelli, O.; Amantini, C.; Giangrossi, M.; Santoni, G.; Fanelli, A.; Luongo, M.; Nabissi, M. In Vitro and In Vivo Effects of Melatonin-Containing Combinations in Human Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J Pineal Res 2024, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. K.; Lin, Z.; Tidwell, W. J.; Li, W.; Slominski, A. T. Melatonin and Its Metabolites Accumulate in the Human Epidermis in Vivo and Inhibit Proliferation and Tyrosinase Activity in Epidermal Melanocytes in Vitro. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2014, 404, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayahara, G. M.; Valente, V. B.; Pereira, R. B.; Lopes, F. Y. K.; Crivelini, M. M.; Miyahara, G. I.; Biasoli, É. R.; Oliveira, S. H. P.; Bernabé, D. G. Pineal Gland Protects against Chemically Induced Oral Carcinogenesis and Inhibits Tumor Progression in Rats. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 1816–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Q.; Dong, C.; Xu, H.; Khan, B.; Jin, J.; Liu, Q.; Shi, J.; Hou, Y. PD-L1 Degradation Pathway and Immunotherapy for Cancer. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Rao, P. G.; Liao, B. Z.; Luo, X.; Yang, W. W.; Lei, X. H.; Ye, J. M. Melatonin Suppresses PD-L1 Expression and Exerts Antitumor Activity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, Y. C.; Lee, K. Y.; Wu, S. M.; Kuo, D. Y.; Shueng, P. W.; Lin, C. W. Melatonin Downregulates Pd-L1 Expression and Modulates Tumor Immunity in Kras-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Chen, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, H.; Jiang, E.; Shao, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhou, X.; Shang, Z. Melatonin Inhibits EMT and PD-L1 Expression through the ERK1/2/FOSL1 Pathway and Regulates Anti-Tumor Immunity in HNSCC. Cancer Sci 2022, 113, 2232–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Hou, Y.; Long, M.; Jiang, L.; Du, Y. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 α in Metabolic Reprogramming in Renal Fibrosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucielo, M. S.; Cesário, R. C.; Silveira, H. S.; Gaiotte, L. B.; Dos Santos, S. A. A.; de Campos Zuccari, D. A. P.; Seiva, F. R. F.; Reiter, R. J.; de Almeida Chuffa, L. G. Melatonin Reverses the Warburg-Type Metabolism and Reduces Mitochondrial Membrane Potential of Ovarian Cancer Cells Independent of MT1 Receptor Activation. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucielo, M. S.; Freire, P. P.; Emílio-Silva, M. T.; Romagnoli, G. G.; Carvalho, R. F.; Kaneno, R.; Hiruma-Lima, C. A.; Delella, F. K.; Reiter, R. J.; Chuffa, L. G. de A. Melatonin Enhances Cell Death and Suppresses the Metastatic Capacity of Ovarian Cancer Cells by Attenuating the Signaling of Multiple Kinases. Pathol Res Pract 2023, 248, 154637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas-Romero, S.; Saderi, N.; Ramirez-Plascencia, O. D.; Baez-Ruiz, A.; Flores-Sandoval, O.; Briones, C. E.; Salgado-Delgado, R. C. Melatonin Prevents Tumor Growth: The Role of Genes Controlling the Circadian Clock, the Cell Cycle, and Angiogenesis. J Pineal Res 2025, 77. (4), e70064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I.; Elbe, H.; Bicer, Y.; Karayakali, M.; Onal, M. O.; Altinoz, E. Therapeutic Role of Melatonin on Acrylamide-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Pinealectomized Rats: Effects on Oxidative Stress, NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway, and Hepatocellular Proliferation. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2023, 174, 113658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hao, B.; Zhang, M.; Reiter, R. J.; Lin, S.; Zheng, T.; Chen, X.; Ren, Y.; Yue, L.; Abay, B.; Chen, G.; Xu, X.; Shi, Y.; Fan, L. Melatonin Enhances Radiofrequency-Induced NK Antitumor Immunity, Causing Cancer Metabolism Reprogramming and Inhibition of Multiple Pulmonary Tumor Development. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6. (1), 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedighi Pashaki, A.; Sheida, F.; Moaddab Shoar, L.; Hashem, T.; Fazilat-Panah, D.; Nemati Motehaver, A.; Ghanbari Motlagh, A.; Nikzad, S.; Bakhtiari, M.; Tapak, L.; Keshtpour Amlashi, Z.; Javadinia, S. A.; Keshtpour Amlashi, Z. A Randomized, Controlled, Parallel-Group, Trial on the Long-Term Effects of Melatonin on Fatigue Associated With Breast Cancer and Its Adjuvant Treatments. Integr Cancer Ther 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, N. D.; Khorasanchi, A.; Pandey, S.; Nemani, S.; Parker, G.; Deng, X.; Arthur, D. W.; Urdaneta, A.; Fabbro, E. Del. Melatonin Supplementation for Cancer-Related Fatigue in Patients With Early Stage Breast Cancer Receiving Radiotherapy: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Oncologist 2024, 29, E206–E212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, D.; Gubin, M. M.; Schreiber, R. D.; Smyth, M. J. New Insights into Cancer Immunoediting and Its Three Component Phases — Elimination, Equilibrium and Escape. Curr Opin Immunol 2014, 27. (1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, G. P.; Old, L. J.; Schreiber, R. D. The Immunobiology of Cancer Immunosurveillance and Immunoediting. Immunity 2004, 21, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Lei, Y.; Li, J.-K.; Du, W.-X.; Li, R.-G.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Tan, H.-B. Immune Cells within the Tumor Microenvironment: Biological Functions and Roles in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Lett 2020, 470, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K. E.; Joyce, J. A. The Evolving Tumor Microenvironment: From Cancer Initiation to Metastatic Outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paget, S. THE DISTRIBUTION OF SECONDARY GROWTHS IN CANCER OF THE BREAST. The Lancet 1889, 133, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Vescio, G.; De Paola, G.; Sammarco, G. Therapeutic Targets and Tumor Microenvironment in Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, W. Tumor Microenvironment-Mediated Immune Tolerance in Development and Treatment of Gastric Cancer. Front Immunol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, C. U.; Haining, W. N.; Held, W.; Hogan, P. G.; Kallies, A.; Lugli, E.; Lynn, R. C.; Philip, M.; Rao, A.; Restifo, N. P.; Schietinger, A.; Schumacher, T. N.; Schwartzberg, P. L.; Sharpe, A. H.; Speiser, D. E.; Wherry, E. J.; Youngblood, B. A.; Zehn, D. Defining ‘T Cell Exhaustion. ’ Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montauti, E.; Oh, D. Y.; Fong, L. CD4+ T Cells in Antitumor Immunity. Trends Cancer 2024, 10, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D. B.; Nixon, M. J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D. Y.; Castellanos, E.; Estrada, M. V.; Ericsson-Gonzalez, P. I.; Cote, C. H.; Salgado, R.; Sanchez, V.; Dean, P. T.; Opalenik, S. R.; Schreeder, D. M.; Rimm, D. L.; Kim, J. Y.; Bordeaux, J.; Loi, S.; Horn, L.; Sanders, M. E.; Ferrell, P. B.; Xu, Y.; Sosman, J. A.; Davis, R. S.; Balko, J. M. Tumor-Specific MHC-II Expression Drives a Unique Pattern of Resistance to Immunotherapy via LAG-3/FCRL6 Engagement. JCI Insight 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talib, W. H.; Alsayed, A. R.; Abuawad, A.; Daoud, S.; Mahmod, A. I. Melatonin in Cancer Treatment: Current Knowledge and Future Opportunities. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortezaee, K.; Potes, Y.; Mirtavoos-Mahyari, H.; Motevaseli, E.; Shabeeb, D.; Musa, A. E.; Najafi, M.; Farhood, B. Boosting Immune System against Cancer by Melatonin: A Mechanistic Viewpoint. Life Sci 2019, 238, 116960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, F.; Casares, N.; Martín-Otal, C.; Lasarte-Cía, A.; Gorraiz, M.; Sarrión, P.; Llopiz, D.; Reparaz, D.; Varo, N.; Rodriguez-Madoz, J. R.; Prosper, F.; Hervás-Stubbs, S.; Lozano, T.; Lasarte, J. J. Overcoming T Cell Dysfunction in Acidic PH to Enhance Adoptive T Cell Transfer Immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs-Canner, S. M.; Meier, J.; Vincent, B. G.; Serody, J. S. B Cell Function in the Tumor Microenvironment. Annual Review of Immunology Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org. Guest 2025, 44, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I, R.; E, K. Granzyme B-Induced Apoptosis in Cancer Cells and Its Regulation (Review). Int J Oncol 2010, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrén, I.; Orrantia, A.; Vitallé, J.; Zenarruzabeitia, O.; Borrego, F. NK Cell Metabolism and Tumor Microenvironment. Front Immunol 2019, 10. (SEP), 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillerey, C. NK Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1273, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curti, A.; Ruggeri, L.; D’Addio, A.; Bontadini, A.; Dan, E.; Motta, M. R.; Trabanelli, S.; Giudice, V.; Urbani, E.; Martinelli, G.; Paolini, S.; Fruet, F.; Isidori, A.; Parisi, S.; Bandini, G.; Baccarani, M.; Velardi, A.; Lemoli, R. M. Successful Transfer of Alloreactive Haploidentical KIR Ligand-Mismatched Natural Killer Cells after Infusion in Elderly High Risk Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients. Blood 2011, 118, 3273–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Saxena, S.; Singh, R. K. Neutrophils in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1224, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadas, A. K.; Dilmac, S.; Aytac, G.; Tanriover, G. Melatonin Decreases Metastasis, Primary Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis in a Mice Model of Breast Cancer. Hum Exp Toxicol 2021, 40, 1545–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Shi, H.; Zhang, B.; Ou, X.; Ma, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shu, P.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells as Immunosuppressive Regulators and Therapeutic Targets in Cancer. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2021 6:1 2021, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Chen, J. Melatonin: A Natural Guardian in Cancer Treatment. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1617508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, I.; Manic, G.; Coussens, L. M.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Macrophages and Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab 2019, 30, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haston, S.; Gonzalez-Gualda, E.; Morsli, S.; Ge, J.; Reen, V.; Calderwood, A.; Moutsopoulos, I.; Panousopoulos, L.; Deletic, P.; Carreno, G.; Guiho, R.; Manshaei, S.; Gonzalez-Meljem, J. M.; Lim, H. Y.; Simpson, D. J.; Birch, J.; Pallikonda, H. A.; Chandra, T.; Macias, D.; Doherty, G. J.; Rassl, D. M.; Rintoul, R. C.; Signore, M.; Mohorianu, I.; Akbar, A. N.; Gil, J.; Muñoz-Espín, D.; Martinez-Barbera, J. P. Clearance of Senescent Macrophages Ameliorates Tumorigenesis in KRAS-Driven Lung Cancer. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 1242–1260e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumitomo, R.; Hirai, T.; Fujita, M.; Murakami, H.; Otake, Y.; Huang, C.-L. M2 Tumor-Associated Macrophages Promote Tumor Progression in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Exp Ther Med 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Luo, J.; Guo, W.; Sun, L.; Lin, L. Targeting M2-like Tumor-Associated Macrophages Is a Potential Therapeutic Approach to Overcome Antitumor Drug Resistance. NPJ Precis Oncol 2024, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; Ding, J.; Czyz, D.; Hu, R.; Ye, Z.; He, M.; Zheng, Y. G.; Shuman, H. A.; Dai, L.; Ren, B.; Roeder, R. G.; Becker, L.; Zhao, Y. Metabolic Regulation of Gene Expression by Histone Lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhu, B. Metabolic Regulatory Crosstalk between Tumor Microenvironment and Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Theranostics 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmatirad, S.; Moloudizargari, M.; Fallah, M.; Rahimi, A.; Poortahmasebi, V.; Asghari, M. H. Cancer-Associated Immune Cells and Their Modulation by Melatonin. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2023, 45, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yue, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, C.; Wu, W.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Cheng, Q.; Luo, P.; Liu, G. Define Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) in the Tumor Microenvironment: New Opportunities in Cancer Immunotherapy and Advances in Clinical Trials. Mol Cancer 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Shi, K.; Fu, M.; Chen, F. Melatonin Indirectly Decreases Gastric Cancer Cell Proliferation and Invasion via Effects on Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Life Sci 2021, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talib, W. H.; Alsayed, A. R.; Abuawad, A.; Daoud, S.; Mahmod, A. I. Melatonin in Cancer Treatment: Current Knowledge and Future Opportunities. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, J.-J.; Xu, D.-P.; Li, H.-B. Melatonin for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 39896–39921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, X.; Yu, X.; Tao, J.; Liu, X. Melatonin-Mediated CGAS-STING Signal in Senescent Macrophages Promote TNBC Chemotherapy Resistance and Drive the SASP. J Biol Chem 2025, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, J. K.; Bakhoum, S. F. The Cytosolic DNA-Sensing CGAS-STING Pathway in Cancer. Cancer Discov 2020, 10, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioli, C.; Caroleo, M. C.; Nistico’, G.; Doriac, G. Melatonin Increases Antigen Presentation and Amplifies Specific and Non Specific Signals for T-Cell Proliferation. Int J Immunopharmacol 1993, 15, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Tao, Z.; Zhu, W.; Su, Y.; Choi, W. S. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Facilitate Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas Migration and Invasion by MIF/NLRP3/IL-1β Circuit: A Crosstalk Interrupted by Melatonin. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2023, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Syeda, S.; Rawat, K.; Kumari, R.; Shrivastava, A. Melatonin Modulates L-Arginine Metabolism in Tumor-Associated Macrophages by Targeting Arginase 1 in Lymphoma. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2024, 397, 1163–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K. M. R.; França, D. C. H.; de Queiroz, A. A.; Fagundes-Triches, D. L. G.; de Marchi, P. G. F.; Morais, T. C.; Honorio-França, A. C.; França, E. L. Polarization of Melatonin-Modulated Colostrum Macrophages in the Presence of Breast Tumor Cell Lines. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Cai, R.; Fei, S.; Chen, X.; Feng, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Song, J.; Zhou, R. Melatonin Enhances Anti-Tumor Immunity by Targeting Macrophages PD-L1 via Exosomes Derived from Gastric Cancer Cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2023, 568–569, 111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Qureshi, M. Z.; Tahir, F.; Yilmaz, S.; Romero, M. A.; Attar, R.; Farooqi, A. A. Role of Melatonin in Carcinogenesis and Metastasis: From Mechanistic Insights to Intermeshed Networks of Noncoding RNAs. Cell Biochem Funct 2024, 42. (4), e3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan Gao; Lin, Y. ; Zhang, M.; Niu, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, W.; Xia, H.; Lin, H.; Guo, Z.; Du, G. The Combination of LPS and Melatonin Induces M2 Macrophage Apoptosis to Prevent Lung Cancer. http://www.xiahepublishing.com/ 2022, 7, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).