3.2. Collective Behavior of a Small Ensemble

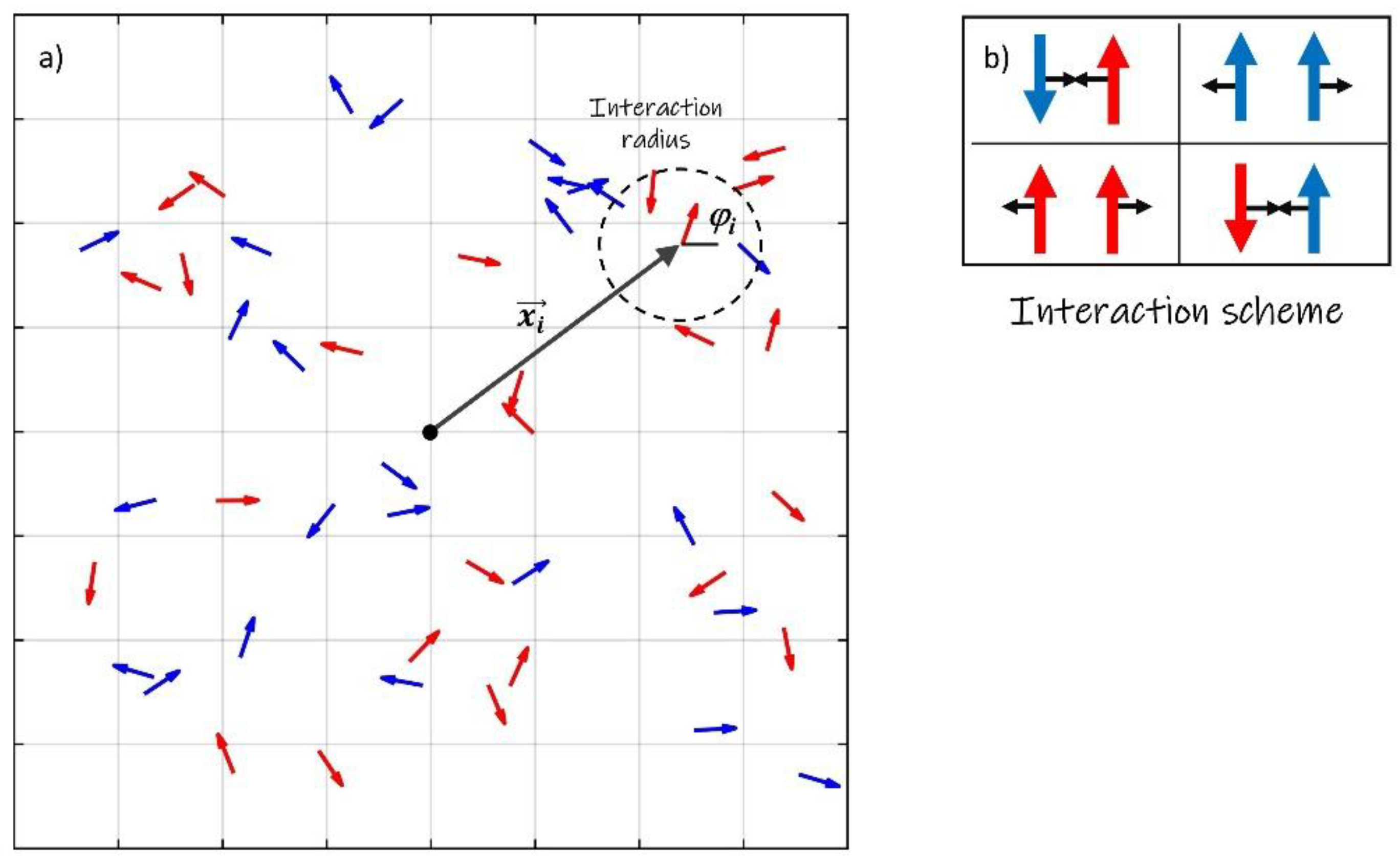

In this subsection I report on numerical simulations concerning an ensemble of N = 80 c-spins for increasing values of the control parameter Δ.

Weak anisotropy

I have numerically integrated, by means of a standard method, Eqs. (1)-(2) for N = 80 c-spins with Δ = 0.1, i.e. well inside the stable locking range Δ < ½. The initial conditions are random spin angles with uniform distribution between 0 and 2π, and random spin positions uniformly distributed in a square box; the size of the box is chosen equal to

so that the c-spin density inside the box is equal to 1. As discussed in previous works [

17,

18,

19] this density choice is not critical, but if the units are too sparse they tend to separate in non-interacting clusters, whereas if too compressed, the collective flow discussed later are hindered and struggle to emerge.

The resulting spatiotemporal dynamics is shown in Movie S1 and the regime configuration is reported in

Figure 3.

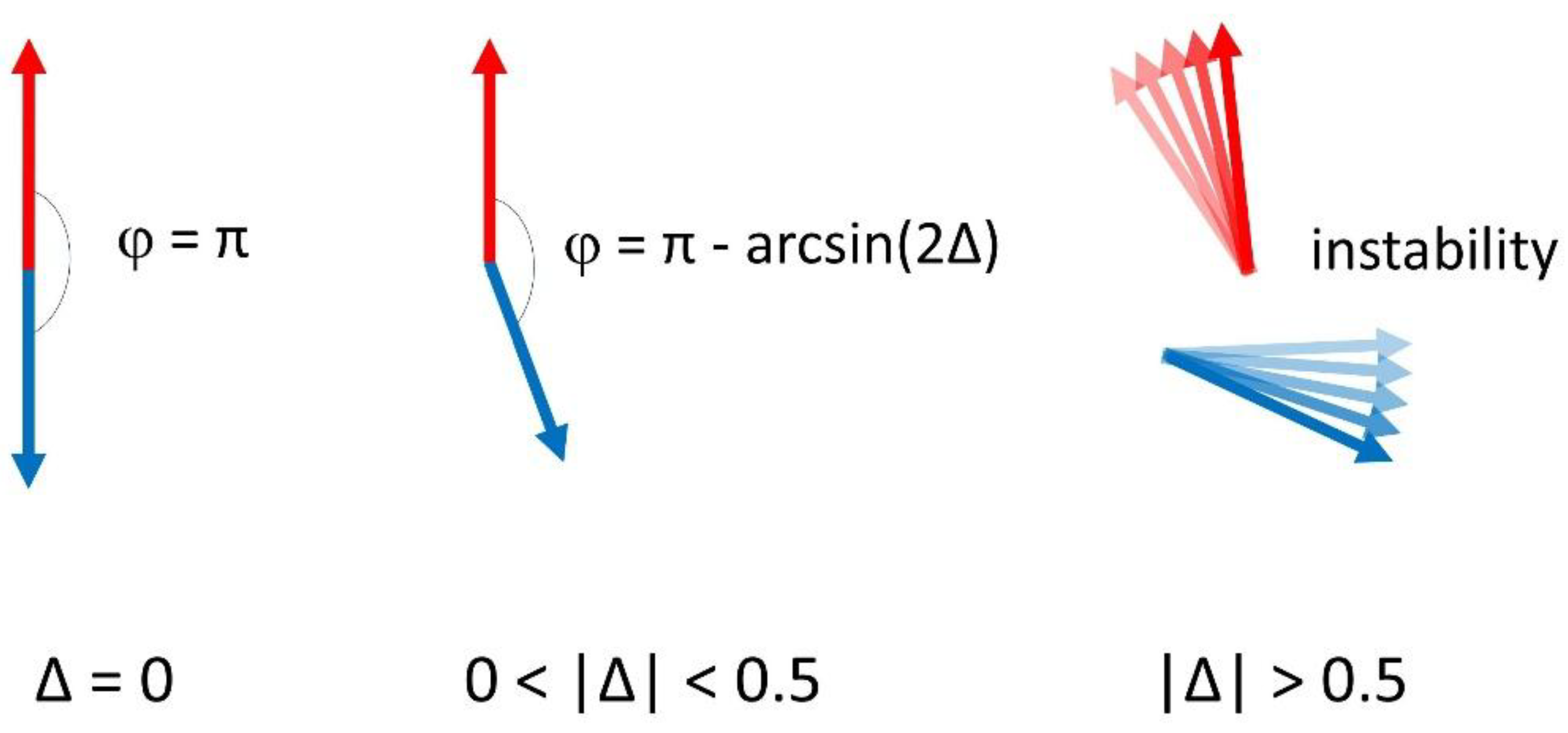

The pattern reported in

Figure 3 is made of (quasi) regularly spaced c-dipoles, each of which fulfils the local stability properties of the single c-dipole (see

Figure 2b). The pattern of

Figure 3 represents an equilibrium state associated to the spontaneous breaking of a continuous circular symmetry, like in ferromagnetic systems or in collective synchronization, the c-dipoles are forced to align at a specific angle, randomly determined by the initial conditions. This kind of pattern is referred to hereafter as a Type ① solution. The spatial regularity is due to a weak repulsive dipole-dipole force, which is proportional to Δ2 and pushes the pattern to expand. The expansion rate is logarithmic; consequently, for practical purposes, it vanishes when it attains approximately three times the interaction length.

Moderate anisotropy

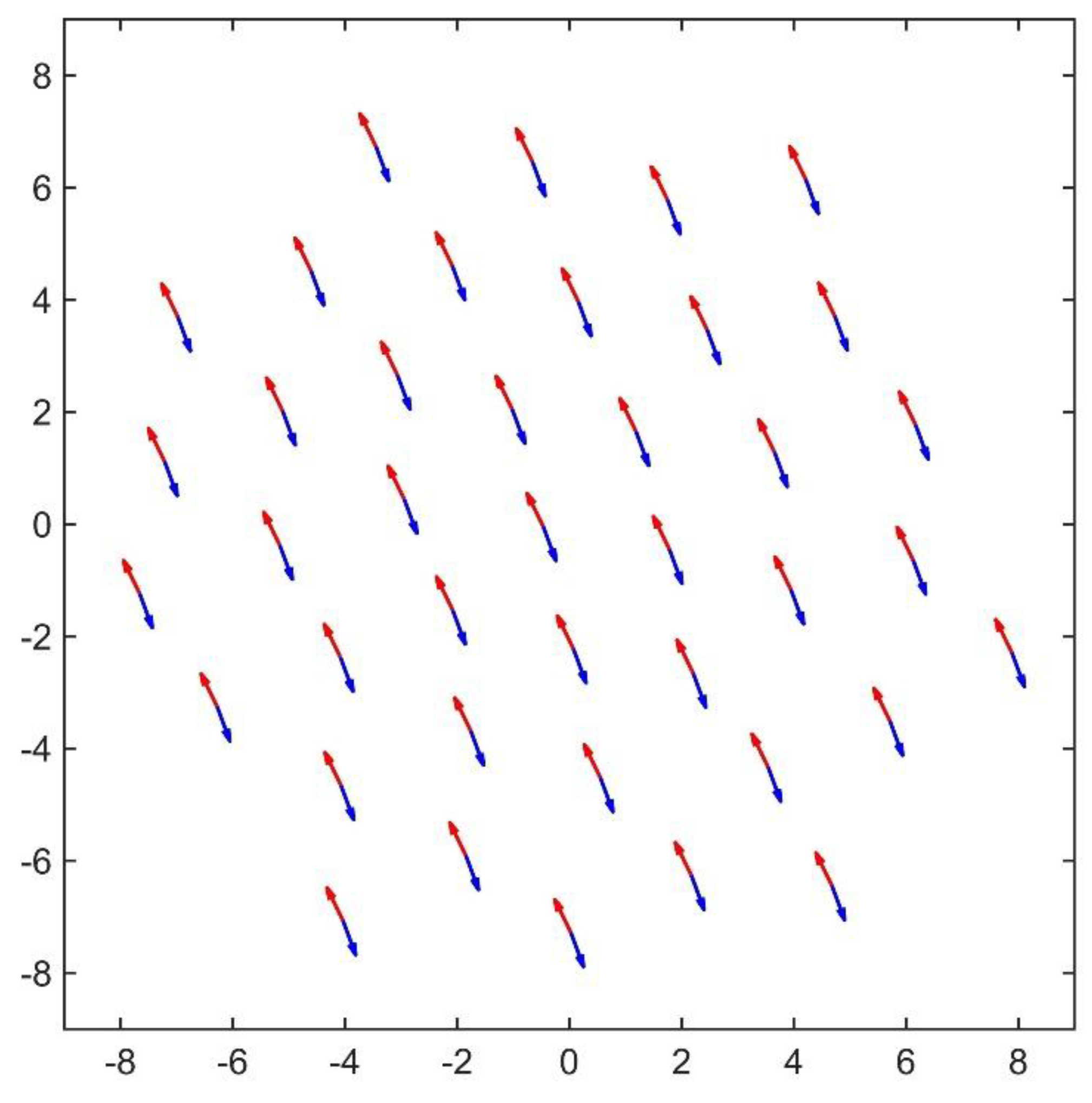

Increasing Δ without crossing the local stability threshold, a different collective behavior shows up, bistable with type ①. The Movie S2 shows the spatiotemporal evolution of N = 80 c-spins with Δ = 0.2. After the transient has expired, the movie displays the appearance of a topological vortex complex exhib-iting a peculiar twofold structure: a static texture, where the c-dipoles curl around a central core, sur-rounding a dynamic state made by two trains of equidistant counterpropagating c-spins that insist on the same loop trajectory. The distance between adjacent c-spins of the same color in the loop is equal to 1 in average, with very small deviation; the orientational and the positional motions are synchronized in a Spin-Momentum locked state, i.e. one full rotation in spin correspond to one full rotation in the space loop. Surprisingly, the red and blue c-spin trains slide over each other “frictionless”, despite the value of Δ (smaller than the locking threshold) would require that c-spins of different colors attract and lock in the same position. I have called that vortex complex (static texture + dynamic loop) a type ② solution.

Emergent Type ② solutions are topological point defects driven by phase singularity, and represent a dynamic balance between alignment interactions and “spin-orbit” coupling. They appear in two forms, for the same parameter values, as illustrated in a superimposition of video frames (akin to a long-exposure photograph, shown in

Figure 4). These forms are classified (see

Table 1) based on their winding number (or topological charge, Q), which measures the net rotation of the c-dipoles orientation along a counterclockwise (CCW) closed path around the defect core. These complexes constitute a whole new class of non-equilibrium dissipative states.

Diversity of attractors and topological invariants

The attractors emerging from repeated simulations of Eqs. (1)-(2), within the locking region and for a given system size (N = 80), show a wide range of morphological diversity; still, all them can be ascribed to one out of three distinct types based on their topological properties: type ① solutions (equilibrium states with Q = 0), type ② vortex (

Figure 5 a, d and e) with Q = 1, or type ② antivortex (

Figure 5 b and f) with Q = -1. The emerging type ② solutions display a high degree of variability in terms of: the number of elements involved in the internal loop; the phase singularity position in the plane; the vorticity and the velocity of the transport motion (momentum); and the spin rotation velocity in the loops. Rarely, a double loop with a daughter loop branching off from the main formation (see

Figure 5d) appear, providing evidence of the system’s capacity for morphological complexity, as discussed in a later section; however, even that “strange” configuration belongs to the Q = +1 topological class.

Above the locking threshold, numerical simulations for Δ > ½ show spatiotemporal chaotic dynamics in both position and orientation, a form of active turbulence, a global consequence of the local unlocking transition. I call type ③ this kind of supercritical patterns. Increasing further Δ the behavior becomes more erratic and finally no trace of order is left.

Robustness against perturbations

The primary implication of a topological invariant is robustness. In a topological state, the value of the invariant remains unchanged under continuous deformations, minor perturbations, or the high degree of diversity in spatial arrangements. In fact, the complementary regime structures obtained in the previous subsection, made of vortex and antivortex complexes, proved to be highly resilient with respect to different kinds of perturbations. First, the structures persist stable under the addition of Langevin white noise terms to Eqs. (1)-(2) even at high levels of noise. Second, I perturbed the structure emerged in Movie S2 in the following way: after the structure is formed, I removed one red spin from a c-dipole forming the external texture and place into the vortex, close to the center, the result in reported in Movie S3. The displaced red element is quickly absorbed in the vortex and, after a short time, a red spin is expelled from the internal loop so that it can couple back with the blue spin left uncoupled and reform a c-dipole to restore the original topology. This observed self-repairing capability is a direct consequence of the non-local topological protection inherent to these complexes.

The reported results suggest that a relatively small ensemble of N = 80 c-spin shows a rich multi-stable scenario that requires a systematic analysis. Moreover, the type ② patterns are non-local solutions that cannot be understood in terms of a local stability analysis, they are therefore hard to tackle analytically moving from Eqs. (1)-(2), so I have relied on a statistic analysis based on extensive numerical simulations.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Considering the system (1)-(2), I have performed reiterated numerical simulations and Δ spanning from 0 to 1, with different realizations for each value of Δ, starting from random initial conditions with the same statistical properties: random positions in a box with spin density equal to 1 and uniform random orientations in [0, 2π]. I have taken as a reference a collective parameter: the total time averaged kinetic energy

Tav

that account for spatial fluctuations;

stands for temporal average. The results for

Tav, versus Δ are shown in

Figure 6a.

Panel (a) of

Figure 6, shows T

av ≈ 0 for low values of Δ, approximately 0 < Δ < Δ

low with Δ

low ≈ 0.18. In this region the equilibrium type ① patterns appear, stably. For Δ

low < Δ < Δ

th the values of T

av separates in two branches. The lower branch is a continuation of the type ① pattern branch from the previous interval, and is bistable with a second branch containing the twofold type ② patterns discussed in the previous subsection. The upper branch follows approximately a Δ

2 dependence (orange fitting line in

Figure 6a) and contains an infinite number of different attractors, separated in two families classified via Q). For Δ > Δ

th, local instabilities take places as predicted by Eq. (4), all the c-dipoles unlock destroying both type ① and ② attractors, and chaotic dynamics (type ③ attractors) appear, increasingly turbulent as Δ increases further. Close after Δ

th small vortices may still be present, together with other dynamic patterns and floating spins, whereas for high values of Δ any trace of positional and orientational order is finally lost.

The transition from type ① to type ③ patterns is understood in terms of the breaking of a local circular symmetry, parallel to the transition to a ferromagnetic state, or to the Kuramoto transition to collective synchronization. It is a “classical” spontaneous symmetry breaking phase transition of the Landau type. Indeed, it can be described by means of the Kuramoto order parameter, modified as in previous works [

17,

18,

19]

The time averaged absolute value

is bounded between 0 and 1, where 1 means total phase synchronization and 0 total phase desynchronization. Panel (b) of

Figure 6 shows the typical Kuramoto-like phase transition behavior when

is computed versus Δ.

Figure 6b concerns the transition type ① to type ③, obtained by making the system start from initial conditions close to the basin of attraction of type ① solution.

It is worth noticing that the point Δ = Δ

th organizes a double phase transition, a Kuramoto-like and a topological one. As already mentioned, the emergence of type ② attractors is not related to a spontaneous symmetry breaking of a local symmetry, it displays the characteristic features of a topological phase. Such features are: the robustness and the non-local character, the topological invariants, the dissipationless transport and the spin-momentum locking. Those type ② patterns contain features surprisingly parallel to those of quantum states of matter. Specifically, the patterns exhibit features that parallel the spin helical transport regime found in topological insulators [

21], showcasing robust, counterpropagating dissipationless flow, also found here, within a dynamical non-equilibrium system, for the first time to the best of my knowledge. However, together with similarities with other systems, the c-spin model shows consistent peculiarities. In particular, the scenario grows increasingly complex and peculiar when more c-spins are considered.

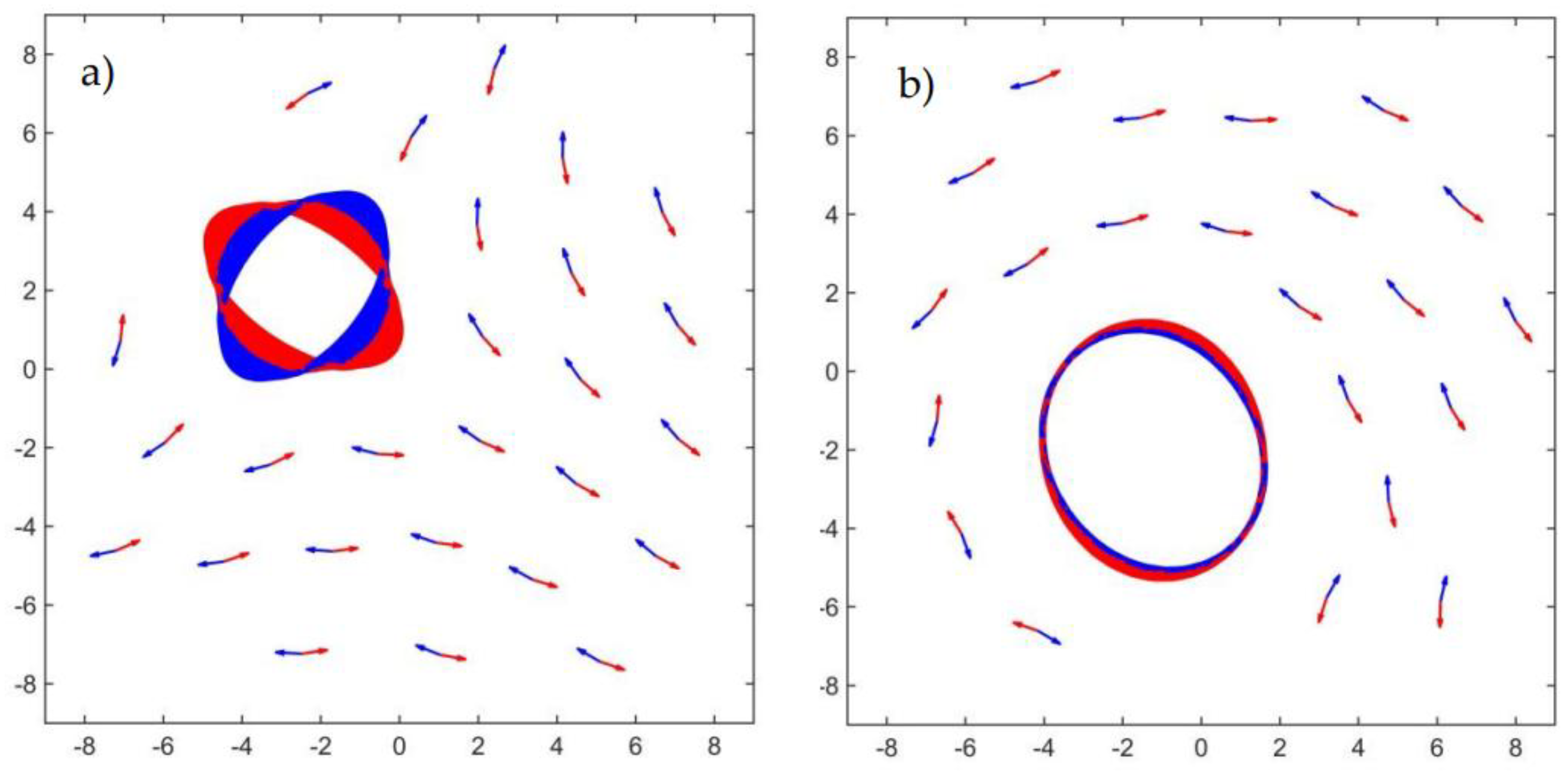

3.4. Larger Systems

In this subsection, the evolution of type ② solutions is examined as the system size N increases by means of a few examples. As a general remark, the single loop patterns observed in smaller systems are replaced by a flexible, morphogenetic flow that generates dynamic compartments and a progressively more intricate spin-momentum locked flows as N increases, displaying both long-range order and topological protection.

Figure 7 illustrates the progression from N=200 (simple figure-eight shape) to N=500 (more convoluted boundary loops) to N=1000 (highly intricate, compartmentalized network). A detailed analysis of the N = 1000, Δ = 0.01 case is provided in reference [

18]. The Movie S4 shows the regime behavior for N = 500 and Δ = 0.1. The c-dipoles static texture is an antivortex with Q = -1, and the locked spin-momentum flow percolates the whole system size. The spin-momentum relationship is still a kind of synchronization, but more intricate respect to the simple 1:1 locking displayed by smaller systems.

Figure 7c also shows instabilities in the c-dipole textures, witnessing a weakening of the topological protection. Indeed, in [

18] it is reported that such network is only marginally stable and has a finite lifetime; a possible reason for it is unveiled in the next section.

The big sizes are numerically hard to tackle, the flow stabilizes after a long, non-exponential “glassy” transient with power-low frequency spectrum [

18]. Many scenarios open, that will be the object of future research.

3.3. Phase Diagram

By exploring different system sizes, ranging from N = 80 to N = 1000, I have observed that the values of Δ required to obtain type ② solutions decrease as the system size N increases. To highlight the transition between the stability region of type ① and the bistable region containing both type ① and ②, I performed extensive numerical simulations across the (N, Δ) parameter plane. The result is reported in

Figure 8, where white dots indicate the presence of a type ① uniform solution and black dots denote the emergence of type ② vortex complexes. The analysis reveals that as N increases, the transition value of Δ (previously termed Δ

low) decreases following the empirical scaling relationship

with

is a fitting parameter. Repeated simulations consistently yielded similar results, and data from single runs at higher values of remained consistent with the scaling behavior described by Eq. (9). As an addendum to previous results, what was called “network death” in [

18] can understood in the light of Eq. (9). In [

18], the emergence of a complex spin-momentum locked network with N = 1000 and Δ = 0.01 (sketched

Figure 7c) was reported. The network revealed not to be stable in the very long run. In fact, Eq. (9) gives Δ

low(N=1000) = 0.012 as the lower stability threshold for those kind of solutions; so, being close to threshold but outside the stability region, the network was marginally stable and did not endure.

Since the density is fixed, N (the number of c-spins) also represents the area of the squared box where the dynamics initiate (see inset in

Figure 8). Consequently, the significant value is the product of the anisotropy Δ and the system size N. This product NΔ

low effectively acts as a minimum ‘quantum’ necessary to assist the formation of the topological phase, and, since Δ cannot exceed Δ

th= 0.5 which would activate chaotic behavior, the minimum size for having vortex/antivortex complexes is N = 24.

The number N = 24 appears to be the smallest number of c-spins that can structurally support the complex arrangement required for a stable, self-organized vortex or antivortex composite, it represents the point where the behavior transitions from single-unit interactions to collective organization: the onset of collective behavior: Below N = 24, the local interactions dominate, and complex collective structures cannot “nucleate” effectively.