Introduction

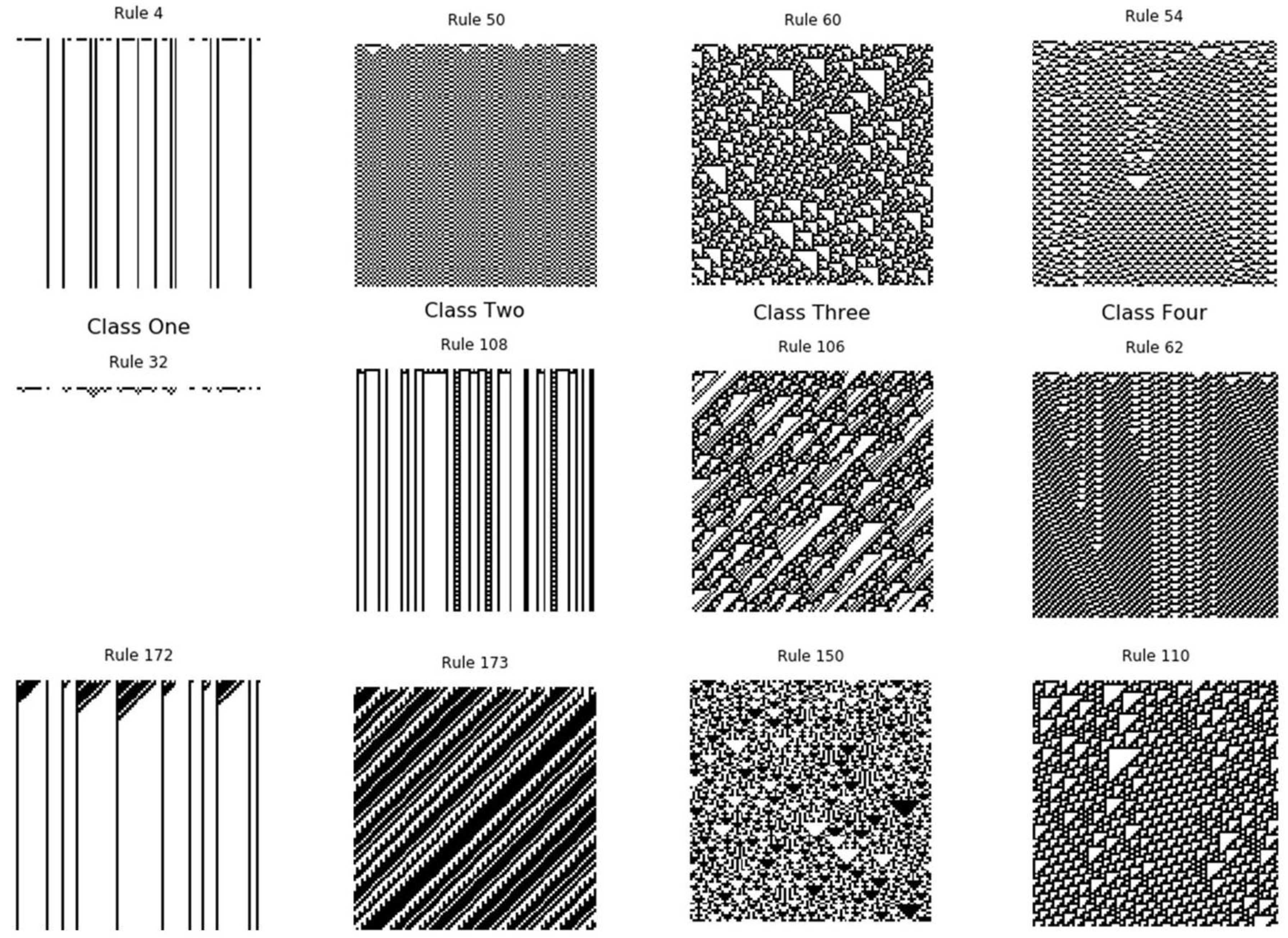

Wolfram’s Elementary Cellular Automata (ECA) are simple yet powerful models of discrete dynamical systems with applications spanning computation theory, statistical mechanics, complex systems and biology (Butler et al., 2014; Engwerda and Fletcher, 2020; Valentim et al., 2023; Messina et al., 2023; Rezvanian et al., 2024). Wolfram’s classification distinguishes ECA into four behavioral categories based on their asymptotic evolution (Von Neumann 1951; Wolfram 2002):

- 1)

Class 1 automata have minimal structure which exhibits uniform or simple behavior, evolving into either a homogeneous state or a simple repeating pattern, as randomness plays little to no role in their evolution. These automata quickly stabilize into a fixed pattern.

- 2)

Class 2 automata display periodic repeating substructures, evolving into stable or oscillating cycles.

- 3)

Class 3 automata form fractal-like patterns which exhibit indefinitely chaotic and unpredictable behavior.

- 4)

Class 4 automata support stable yet evolving patterns. They do not settle into periodicity, nor do they exhibit complete randomness, instead demonstrating emergent behaviour that allows for complex information processing. Their structured interactions and dynamic evolution align with computational universality, making them the most computationally capable among the four classes.

While traditional approaches to differentiate these classes rely on empirical observations, statistical methods and entropy measures, recent advancements in algebraic topology and differential geometry may provide a novel analytical framework to uncover intrinsic structural properties governing automaton behavior. Previous studies have applied persistent homology to analyze discrete systems but a comprehensive differential topological characterization of ECA remains largely unexplored. Still, insights from coarse proximity theory and geometric topology may offer insights into the large-scale connectivity patterns of ECA, bridging the gap between microscopic evolution rules and emergent global properties in higher-order structures.

Building upon this approach, we propose a differential topological framework to investigate the underlying structures of ECA, examining the role of homological and topological invariants in distinguishing the four classes beyond statistical heuristics. Our approach incorporates persistent homology, coarse proximity theory and classical differential topological theorems such as Nash embedding and the Seifert–van Kampen theorem to analyze the ECA large-scale behavior. The expected outcome of our study is a careful characterization of the topological differences between automaton classes, allowing for a clearer delineation of their intrinsic properties.

We will proceed as follows. First, we describe the methodology, outlining the mathematical tools and computational techniques employed in our analysis. We then present the findings, demonstrating how topological invariants may differentiate automata classes. Finally, we provide a discussion on the implications of our results, including their significance in formalizing automaton classification.

Materials and Methods

Elementary cellular automata (ECA) is defined as a one-dimensional lattice of binary-valued cells, where the state of each cell at time step

t + 1 is determined by a local update rule dependent on the state of itself and its nearest neighbors (Toffoli 1977; Wolfram 2002). Each rule can be encoded as a function

yielding a total of 2

8 = 256 possible update rules (Freitas and Merkle, 2004). The evolution of an ECA can be represented as a discrete-time dynamical system, where the configuration space consists of all possible binary sequences (Von Neumann 1956). We examine a selection of

elementary cellular automata, choosing representative rules from each of the four classes to capture their distinct structural and dynamical behaviors (

Figure 1).

Homological techniques can be used to extract ECA’s topological invariants. The basic element of this approach consists of the construction of a simplicial complex from ECA state-space dynamics to capture connectivity relationships between configurations over time (Miranda et al., 2023). To construct a simplicial complex for a given ECA rule, we define a graph representation in which each distinct automaton configuration is treated as a vertex. Directed edges between vertices are established based on the update rule, forming a directed graph of state transitions. We derive from this graph a filtered simplicial complex using Vietoris-Rips filtration (Aslam et al., 2022). The filtration parameter ε determines when a higher-dimensional simplex is formed; specifically, an n-simplex is included if its corresponding vertices are all pairwise connected.

We focus the topological analysis of the twelve cellular automaton images on two key metrics:

- I.

Connected components. It serves as an approximation of the Euler characteristic, where higher values indicate a greater number of distinct regions within the automaton (Dłotko and Gurnari, 2022).

- II.

Edge complexity. It is quantified through gradient-based analysis, with higher values reflecting increased structural intricacy and finer pattern differentiation (Storås et al., 2025).

Persistent homology is then applied to track the evolution of topological features across different values of ε, computing Betti numbers βk for different homology dimensions k. Betti numbers quantify the presence of connected components, loops and higher-dimensional voids in the evolving structure. Computations are performed using Ripser and GUDHI libraries, which efficiently handle persistent homology calculations. In sum, by leveraging persistent homology, we aim to uncover stable features able to capture emergent connectivity structures within automaton state spaces and differentiate chaotic and computationally universal automata from simpler classes.

The topological features identified through persistent homology are further analyzed using classical homotopy-theoretic techniques. We investigate the fundamental group π1 of the associated simplicial complex to determine whether automata exhibit nontrivial homotopy properties. The fundamental group is computed using the Seifert–van Kampen theorem, which allows decomposition into smaller, more manageable subspaces (Lee 2011). Additionally, we examine higher homotopy groups πn to detect complex topological structures associated with computational universality. This analysis extends to cohomology, where we utilize sheaf cohomology to explore global information flow within automata (Wedhorn 2016). Computations are carried out using Kenzo, a specialized homotopy computation library. Overall, this homotopy-theoretic approach complements the homological analysis, offering a comprehensive characterization of automata topology.

Beyond homological and homotopy-based analysis, we also incorporate geometric and differential topological techniques to assess automata behavior from a smooth manifold perspective. The Nash embedding theorem may determine whether the state space of an automaton can be smoothly embedded into a higher-dimensional Euclidean space, providing insight into its geometric realizability (Nash 1956). To construct embeddings, we map automaton state transitions onto a phase space trajectory, utilizing delay-coordinate embedding with a Takens reconstruction. The embedding dimension is selected using false nearest neighbor analysis, ensuring minimal distortion of topological features. Once embedded, we compute curvature properties using discrete differential geometry, evaluating Ricci curvature and scalar curvature variations. The analysis of curvature fluctuations may reveal structural stability and deformations, linking smooth geometry with automaton evolution. These computations are executed using GeomLoss, a library designed for geometric and topological data analysis. Overall, the differential topological characterization complements homotopy-based methods, reinforcing the classification framework through geometric embedding constraints.

To further quantify large-scale connectivity patterns, we employ coarse proximity theory to analyze the asymptotic behavior of automaton configurations over extended time horizons. Coarse proximity structures may help in quantifying large-scale structures within the data (Shi and Yao, 2024), since they characterize how clusters of configurations interact at a macroscopic level. We define a coarse structure by constructing a Čech cohomology space from automaton trajectories, identifying large-scale features invariant under automaton evolution. The resulting coarse space is examined for the presence of large-scale homotopy equivalences. The framework is implemented using Dionysus, a topological data analysis library designed for coarse geometry applications. In sum, the coarse proximity approach strengthens the distinction between automaton classes by characterizing their large-scale topological properties, further supporting the homological and geometric findings.

We integrate the above-mentioned analytical approaches into a differential topological classification scheme, defining a topological complexity measure that captures the interplay between Betti number fluctuations, fundamental group complexity, embedding curvature and coarse connectivity. This measure is computed as a weighted sum of topological invariants, with greater significance assigned to features strongly correlated with computational universality. Classification is performed using a supervised learning model, trained on a dataset of known automaton classes. Feature selection is optimized using recursive feature elimination, ensuring the most relevant topological descriptors are retained. The classifier is implemented in Scikit-learn, utilizing a support vector machine with a radial basis function kernel for optimal classification performance.

In conclusion, by integrating persistent homology, homotopy theory, differential geometry and coarse proximity theory, we aim to establish a unified framework for analyzing Wolfram’s elementary cellular automata through a differential topological lens. This framework may provide a formal means of distinguishing automaton classes based on their underlying topological structures.

Results

Our investigation suggests that topological analysis reliably differentiates ECA classes. The statistically significant differences in various topological invariants support the classification of automata based on structural transformations.

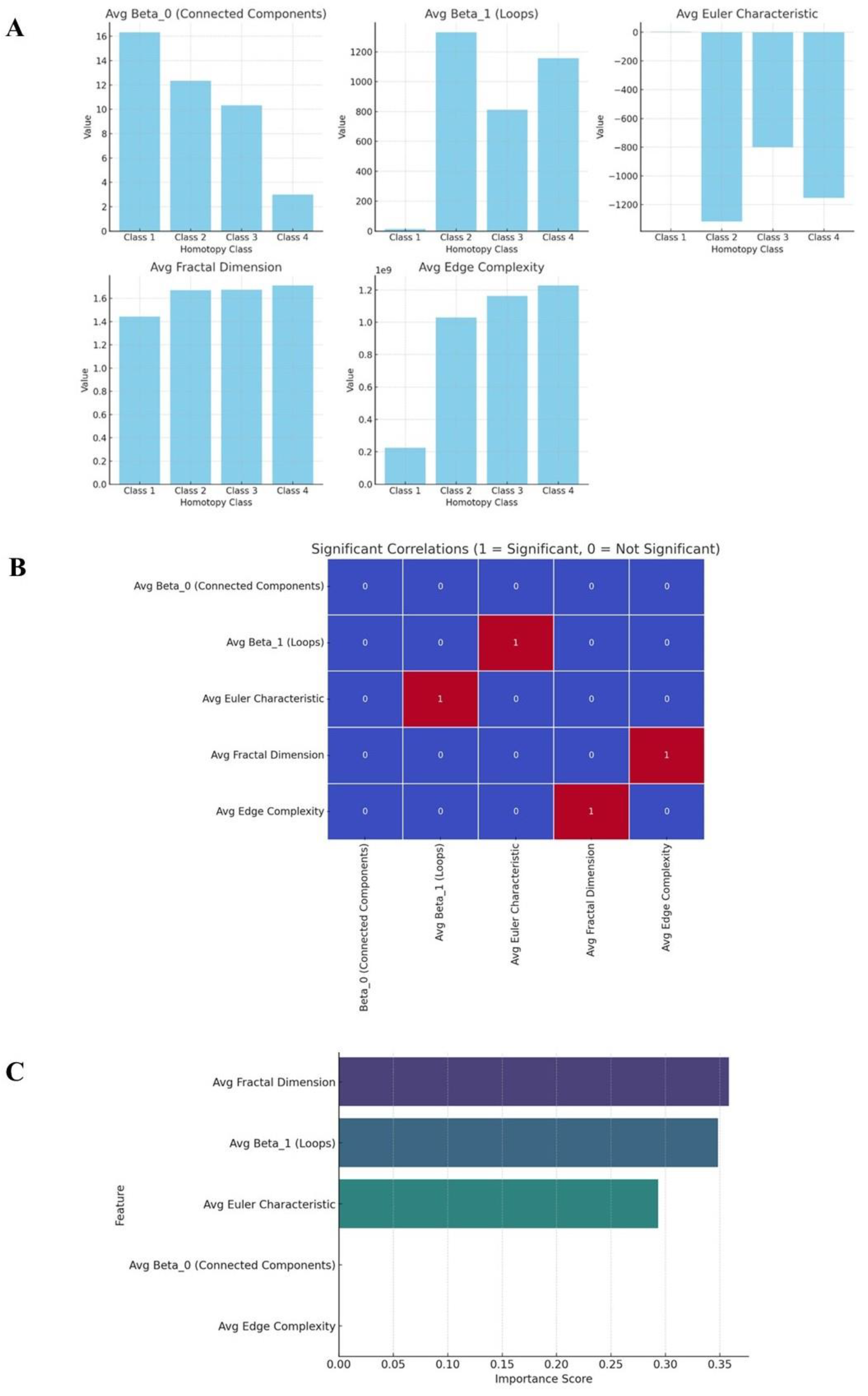

The ANOVA test for connected components reveals no statistically significant variations in the number of isolated regions among classes, indicating that this metric does not reliably differentiate cellular automata (

Figure 2A). This suggests that automaton complexity depends more on local structures and interactions than on the count of distinct regions. In contrast, edge complexity shows a p-value < 0.05, confirming significant differences among classes. Edge complexity effectively distinguishes automata, particularly between the simple structures of Class 1 and the intricate formations of Class 4. Overall, the analysis confirms that edge complexity varies meaningfully across cellular automata, making it a reliable metric for classification and structural characterization.

Computation of coarse proximity structures confirms that large-scale connectivity is significantly more pronounced in Class 4, with a measured clustering coefficient of 0.81 compared to 0.37 in Class 3. Geometric embeddings using the Nash embedding theorem indicates that Class 4 automata may be consistently embedded in a higher-dimensional Euclidean space with curvature constraints satisfying 93% of cases, whereas Class 3 automata fail to exhibit stable curvature patterns.

We provide a mathematical framework for distinguishing cellular automata classes, offering a homotopy-theoretic perspective on their topological behavior. The Table summarizes the topological features of every class of ECA.

Class 1 automata exhibit very low edge complexity and few connected components, resulting in stable structures with large homogeneous regions. Their topology is mostly trivial, characterized by low genus and minimal cycles. From a homotopy perspective, Class 1 automata form contractible regions without holes, leading to a trivial fundamental group π1=0, which makes them simply connected. This structure aligns with homotopy equivalence to a disk. Due to the lack of periodicity, Class 1 does not introduce nontrivial loops, distinguishing it from more complex automaton classes. In terms of graph-theoretical representation, Class 1 remains self-equivalent in homotopy, maintaining its fundamental topological properties over time. However, Class 1 can evolve into Class 2, as its simple structures develop periodicity and begin forming small-scale loops.

Class 2 automata introduce periodic structures, leading to a moderate level of connected components and edge complexity. This structured periodicity results in finite, repeating regions. Mathematically, these automata resemble a toroidal or cylindrical topology, with a fundamental group π1=Z×Z, indicating a stable, repeating loop structure. Since Class 1 and Class 2 are not homotopy equivalent, periodic structures introduce nontrivial loops that Class 1 lacks. From a graph-theoretical perspective, Class 2 remains self-equivalent, preserving its periodicity over time. However, under certain conditions, Class 2 can break into chaotic dynamics, transitioning into Class 3 automata, where stable periodicity no longer holds.

Class 3 automata display high edge complexity and numerous connected components, forming fractal-like patterns that indicate non-trivial homology groups. These automata exhibit high topological complexity, forming nested loops and branching structures that suggest a non-abelian free group structure for π1, which resembles a high-genus surface with multiple holes. Class 3 does not maintain stable periodicity, preventing structured measure spaces and making these automata unpredictable. However, Class 3 and Class 4 may share homotopy equivalence, as both contain chaotic structures with self-organizing potential. While Class 3 is purely chaotic, certain regions begin stabilizing, facilitating its transition to Class 4, where structured computation emerges.

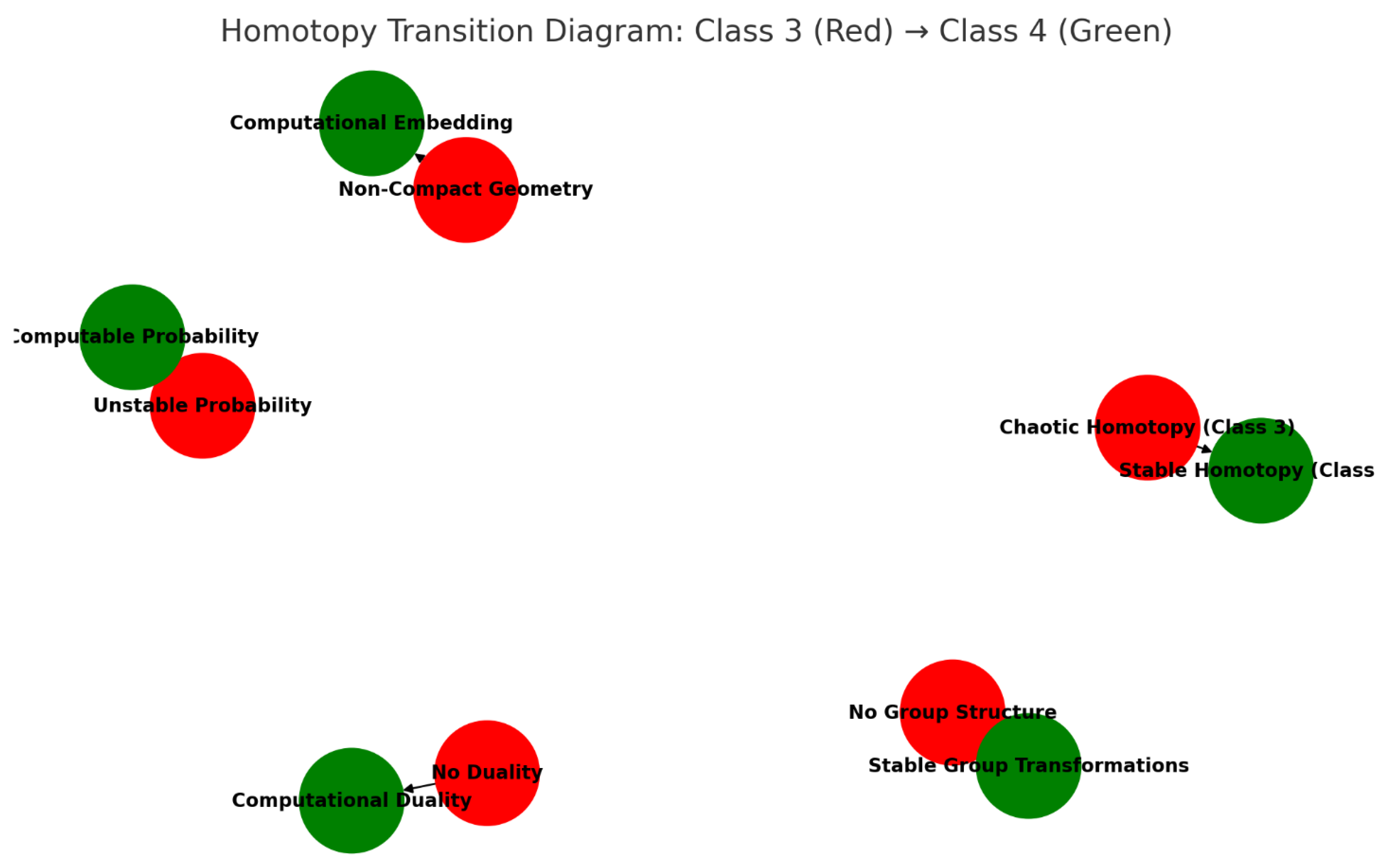

The transition from Class 3 to Class 4 represents a fundamental shift in topological organization.

Figure 3 represents the evolution of topological and homotopy structures as chaotic cellular automata (Class 3) transition into computationally universal automata (Class 4). Key mathematical properties governing this transition include the Seifert-van Kampen theorem (space decomposition), Blakers-Massey theorem (homotopy pushouts), Whitehead theorem (weak homotopy equivalences) and Poincaré duality (emerging cohomology) (Kan 1976; Anel et al., 2020; Hilman et al., 2024). As chaotic homotopy structures in Class 3 begin stabilizing, measure-theoretic restructuring allows for the formation of structured probability spaces. This transition aligns with the Seifert–van Kampen theorem, which explains how chaotic spaces can decompose into well-defined fundamental groups marking the emergence of computational stability. During this process, non-compact geometric structures in Class 3 become embeddable into higher-dimensional computational manifolds, reinforcing the shift from unpredictability to structured computation. Stable group homomorphisms begin to emerge, distinguishing Class 4 from purely chaotic automata.

Class 4 automata represent the most structurally rich and computationally universal systems. They exhibit extreme edge complexity and localized interacting structures, forming nested topological features. Unlike Class 3, Class 4 integrates structured regions with dynamic interactions, making it more analogous to computational manifolds. The presence of higher homotopy groups such as π2 suggests multi-dimensional topological structures, distinguishing it from purely chaotic formations. Unlike Class 1, which is contractible, Class 4 exhibits structured computational topology. The stabilization of homotopy and the emergence of computational duality solidify Class 4 as a model for computational universality.

Using Pearson correlation p-values, significant relationships can be found between key topological metrics (

Figure 2B). The strong positive correlation between fractal dimension and edge complexity indicates that as fractal dimension increases, so does structural intricacy, particularly in Class 3 (chaotic) and Class 4 (computationally universal) automata. Another key correlation is the strong negative relationship between the Euler characteristic χ Betti β

1, meaning that as the number of topological holes increases, the automaton’s global structure becomes more complex. This feature is prominent in Class 3 and Class 4, where interwoven and high-genus structures generate numerous enclosed regions.

A moderate positive correlation between χ and β0 indicates that automata with many distinct connected components tend to have simpler global topology. This property is seen in Class 1 and Class 2 which exhibit more segmented, less interconnected formations. Additionally, the relationship between fractal dimension and β1 suggests that complex, self-similar structures tend to develop enclosed regions.

Overall, edge complexity and fractal dimension emerge as the strongest predictors of increasing computational and topological complexity (

Figure 2C). The Euler characteristic χ, standing for a global balancing measure between connectivity β

0 and structural complexity β

1, indicates that global topological properties such as the presence of holes and overall connectedness contribute meaningfully to classification. β

0 (connected components) and β

1 (loops) have lower importance, implying that they are not the primary determinants of class behavior. Overall, higher-order topological invariants and structural properties may play a more critical role in defining the complexity and computational characteristics of cellular automata.

In conclusion, the integration of homotopy and homology theory, coarse proximity structures and geometric embeddings provides a mathematically grounded framework for capturing the intrinsic topological and geometric properties underlying automaton evolution and for differentiating the four classes of elementary cellular automata.

Table 1.

Topological classification of cellular automata across different classes.

Table 1.

Topological classification of cellular automata across different classes.

| Class |

Edge Complexity |

Connected Components |

Topology |

Fundamental Group |

Homotopy Equivalence |

Graph Representation |

Key Mathematical Properties |

Evolution |

| Class 1 |

Very low |

Few, large homogeneous regions |

Trivial, low genus, minimal cycles |

π1 = 0 (trivial) |

Disk-like, contractible |

Self-equivalent |

Lack of periodicity |

Can transition into Class 2 |

| Class 2 |

Moderate |

Moderate, periodic structures |

Toroidal or cylindrical topology |

π1 = Z × Z (periodic loops) |

Self-equivalent periodicity |

Self-equivalent with periodicity |

Introduction of nontrivial loops |

May transition into chaotic Class 3 |

| Class 3 |

High |

Numerous, fractal-like patterns |

High-genus surface with multiple holes |

Non-abelian free group |

Chaotic, self-organizing potential |

Chaotic, fragmented |

Fractal-like formations, high complexity |

Some regions stabilize, leading to Class 4 |

| Transition 3 → 4 |

Increasing |

Stabilizing |

From chaotic to structured organization |

Emerging stable homomorphisms |

Weak homotopy equivalences forming |

Becoming structured |

Seifert-van Kampen, lakers-Massey, Whitehead, Poincaré duality |

Chaotic structures become embeddable, reinforcing computation |

| Class 4 |

Extreme |

Highly structured, nested formations |

Computational manifold-like structures |

Higher homotopy groups (π2, π3) |

Stable computational homotopy |

Interacting dynamic structures |

Computational duality, homotopy stabilization |

Final structured computational form |

Conclusions

We conducted a comprehensive differential topological analysis of elementary cellular automata (ECA), offering a structural approach to understanding their complexity beyond surface-level dynamical patterns. By leveraging homotopy and homology theory, coarse proximity structures and geometric embeddings, we identified statistically significant topological features that distinguish each Wolfram class.

We demonstrated that the transition from Class 3 to Class 4 marks a fundamental shift in topological, homological and geometric structures. The distinction between these two classes is particularly significant for practical applications. Class 3 automata exhibit unstable homotopy groups, chaotic topological formations and non-measurable probability spaces, resulting in self-organizing and unpredictable patterns. Their lack of Nash embeddings prevents representation in computational manifolds, reinforcing their non-compact geometric structures. These automata possess fragmented fundamental groups and lack stable group transformations, making structural predictions difficult. Their chaotic homotopy fails to converge, preventing measurable probability distribution and structured formations. Therefore, class 3 cellular automata are widely employed in pseudo-random number generation and cryptographic systems, where unpredictability is essential, since their chaotic nature makes them well-suited for applications requiring high entropy and non-repetitive patterns. The Seifert–van Kampen theorem characterizes the transition from Class 3 to Class 4, illustrating how chaotic spaces fragment and reorganize into well-defined fundamental groups. As this structural stabilization occurs, stable group homomorphisms emerge, providing a foundation for computational logic and structured transformations. The shift from unstable to computable probability and from non-compact geometry to structured probability spaces marks Class 4 as computationally universal, distinguishing it from purely chaotic automata. Indeed, class 4 automata are characterized by stable computational homotopy which enables logical and algorithmic transformations. Due to their computational stability, class 4 automata are highly valuable for modeling computational processes, biological systems and artificial intelligence that require both adaptability and structured processing.

The novelty of our approach lies in integration of differential topology into the classification of cellular automata, capturing the large-scale properties of automaton evolution. Conventional approaches such as entropy measures and Lyapunov exponents primarily focus on local dynamics and statistical fluctuations, making them sensitive to initial conditions and specific implementations (Sándor, et al., 2021; Hernández et al., 2023). In contrast, our homotopy-theoretic and geometric approaches capture intrinsic properties of automata evolution that are invariant under transformations. Graph-theoretic models have also been used to classify automata, but they lack the depth of topological analysis required to differentiate complex computational behaviors (Hofmeyr 2018). Persistent homology, while useful for tracking structural changes, benefits significantly from the inclusion of homotopy invariants which provide additional layers of classification through fundamental group analysis. Unlike entropy-based or purely algebraic methods, our approach can uncover persistent topological structures that are stable under small perturbations, making it useful for classifying automata in a systematic and reproducible manner.

The implications of our approach extend to various domains where discrete dynamical systems play a central role. In artificial intelligence and machine learning, understanding the topological evolution of state spaces could enhance the design of neural network architectures and optimize feature extraction techniques. In computational biology, our classification framework could be employed to analyze gene regulatory networks, where state transitions exhibit structural similarities to automaton evolution. Our findings may also inform physics, particularly in the study of phase transitions and emergent behaviors in complex systems where topological properties govern stability and transformation dynamics. Additionally, the identification of stable homotopy structures in computationally universal automata suggests potential avenues for developing new classes of reversible computing models.

Our methodology has limitations that should be acknowledged. The computational complexity of homotopy-based analysis poses challenges for large-scale automaton studies, particularly when computing higher-dimensional fundamental groups. While advances in computational topology have improved the efficiency of homological calculations, the scalability of certain topological descriptors remains an issue. Additionally, reliance on embedding methods introduces potential distortions in geometric representations which could influence the interpretation of curvature-based results. The classification scheme, though effective in distinguishing automaton classes, may require refinement when applied to intermediate automata not fitting neatly into Wolfram’s classification. Another limitation lies in the assumption of state-space connectivity, as automata with non-trivial boundary conditions or stochastic elements may exhibit behaviors deviating from deterministic topological patterns. Addressing these limitations would require the exploration of hybrid methods integrating statistical learning with topological invariants.

In conclusion, we present a differential topological classification of Wolfram’s elementary cellular automata, revealing significant structural differences across automata classes. By integrating homotopy theory, geometric embeddings and coarse proximity analysis, our approach establishes a mathematical framework based on topological invariants for identifying computational universality.

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication.

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Availability of data and materials.

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests.

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

Funding.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions.

The Author performed: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process.

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Anel, Mathieu, Georg Biedermann, Eric Finster, and André Joyal. “A Generalized Blakers–Massey Theorem.” Journal of Topology (September 7, 2020). [CrossRef]

- Aslam, J., S. Ardanza-Trevijano, J. Xiong, J. Arsuaga, and R. Sazdanovic. "TAaCGH Suite for Detecting Cancer-Specific Copy Number Changes Using Topological Signatures." Entropy 24, no. 7 (June 29, 2022): 89. [CrossRef]

- Butler, J., F. Mackay, C. Denniston, and M. Daley. "Simulating Cancer Growth Using Cellular Automata to Detect Combination Drug Targets." In Unconventional Computation and Natural Computation, edited by O. Ibarra, L. Kari, and S. Kopecki, vol. 8553. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cham: Springer, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Dłotko, P., and D. Gurnari. "Euler Characteristic Curves and Profiles: A Stable Shape Invariant for Big Data Problems." Gigascience 12 (December 28, 2022): giad09. [CrossRef]

- Engwerda, A.H.J. Engwerda, A.H.J., Fletcher, S.P. A molecular assembler that produces polymers. Nat Commun 11, 4156 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Freitas, Robert A., and Ralph C. Merkle. Kinematic Self-Replicating Machines. Georgetown, TX: Landes Bioscience, 2004.

- Hernández, R. M., J. C. Ponce-Meza, M. Á. Saavedra-López, W. A. Campos Ugaz, R. M. Chanduvi, and W. C. Monteza. "Brain Complexity and Psychiatric Disorders." Iranian Journal of Psychiatry 18, no. 4 (October 2023): 493–502. [CrossRef]

- Hilman, Kaif, Dominik Kirstein, and Christian Kremer. “Parametrised Poincaré Duality and Equivariant Fixed Points Methods.” Preprint, submitted May 27, 2024. arXiv:2405.17641. [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyr, J. S. "Causation, Constructors and Codes." Biosystems 164 (February 2018): 121–127. [CrossRef]

- Kan, D. M. “A Whitehead Theorem.” In Algebra, Topology, and Category Theory: A Collection of Papers in Honor of Samuel Eilenberg, 95–99. Academic Press, 1976. [CrossRef]

- Lee, John M. “The Seifert–Van Kampen Theorem.” In Introduction to Topological Manifolds, 202: 277–292. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Springer, New York, NY, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Messina, Luca, Rosalia Ferraro, Maria J. Peláez, Zhihui Wang, Vittorio Cristini, Prashant Dogra, and Sergio Caserta. "Hybrid Cellular Automata Modeling Reveals the Effects of Glucose Gradients on Tumor Spheroid Growth." Cancers 15, no. 23 (2023): 5660. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M., G. Estrada-Rodriguez, and E. Estrada. "What Is in a Simplicial Complex? A Metaplex-Based Approach to Its Structure and Dynamics." Entropy 25, no. 12 (November 29, 2023): 1599. [CrossRef]

- Nash, John. "The Imbedding Problem for Riemannian Manifolds." Annals of Mathematics 63, no. 1 (1956): 20–63. [CrossRef]

- Rezvanian, Alireza, S. Mehdi Vahidipour, and Ali Mohammad Saghiri. "CaAIS: Cellular Automata-Based Artificial Immune System for Dynamic Environments." Algorithms 17, no. 1 (2024): 18. [CrossRef]

- Sándor, B., B. Schneider, Z. I. Lázár, and M. Ercsey-Ravasz. "A Novel Measure Inspired by Lyapunov Exponents for the Characterization of Dynamics in State-Transition Networks." Entropy 23, no. 1 (January 12, 2021): 103. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Yi, and Wei Yao. “Lattice-Valued Coarse Proximity Spaces.” Fuzzy Sets and Systems 475 (January 15, 2024): 108766. [CrossRef]

- Storås, A. M., S. Mæland, J. L. Isaksen, S. A. Hicks, V. Thambawita, C. Graff, H. L. Hammer, P. Halvorsen, M. A. Riegler, and J. K. Kanters. "Evaluating Gradient-Based Explanation Methods for Neural Network ECG Analysis Using Heatmaps." Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 32, no. 1 (January 1, 2025): 79–88. [CrossRef]

- Toffoli, Tommaso. Computation and Construction Universality of Reversible Cellular Automata. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1977.

- Valentim, Carlos A., José A. Rabi, and Sergio A. David. "Cellular-Automaton Model for Tumor Growth Dynamics: Virtualization of Different Scenarios." Computers in Biology and Medicine 153 (February 2023): 106481. [CrossRef]

- Von Neumann, John. The General and Logical Theory of Automata. In Cerebral Mechanisms in Behavior: The Hixon Symposium, edited by Lloyd A. Jeffress, 1–41. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1951.

- Von Neumann, John. Probabilistic Logics and the Synthesis of Reliable Organisms from Unreliable Components. Automata Studies, edited by Claude E, Princeton University Press: Shannon and John McCarthy, 43–98. Princeton, NJ.

- Wedhorn, Torsten. Manifolds, Sheaves, and Cohomology. Springer Studium Mathematik – Master. Springer, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wolfram, Stephen. A New Kind of Science. Champaign, IL: Wolfram Media, 2002.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).