1. Introduction

A challenge in human history has been the development of human cognition, specifically the ability to perceive geometric and topological patterns in more than three dimensions. Depending on the topological spaces involved, especially those close to tangent surfaces that approach infinity, great difficulty arises, since human perception is not naturally equipped to conceptualize topological structures with multiple degrees of freedom and complex spatial symmetries.

In the development of mathematical thinking and projective notions, Poncelet [

36] observed that the general equation for a conic section may be expressed as:

When examining the special case where

and

, the formula becomes a sum of squares:

which yields the trivial solution

, an isolated point. Alternatively, the expression

defines imaginary lines, intersecting the

-plane only at the origin. In this context, Poncelet aimed to characterize the geometric properties of imaginary elements, proposing that projections could occur even without intersection with the real plane, thus producing imaginary elements in geometry.

Chaves and Grimberg [

7] discussed the work of 19

th-century mathematicians such as Poncelet, Chasles, and others, who sought to give geometric meaning to expressions such as “infinite points” and “imaginary elements,” in accordance with Poncelet’s principles from 1820 [

35], 1864 [

37], and 1866 [

38], often referred to as the principle of permanence or continuity of mathematical relations. While this idea parallels Carnot’s, Poncelet extended it by proposing the existence of points at infinity, a concept previously hinted at by Kepler and Descartes. Consequently, it became acceptable to say that two lines always intersect: either at a real point or, in the case of parallel lines, at a point at infinity, which Poncelet called the point at infinity.

Poncelet argued that, to generalize geometric reasoning, both imaginary and ideal points must be admitted into synthetic geometry. Under this framework, any circle and any straight line will always intersect. Chasles [

6] and Loud [

26] demonstrated that points at infinity could not physically exist on geometric figures, as they are impossible to construct. Nonetheless, they used the principle of continuity to define the concept of an imaginary point. Thus, Poncelet’s concept of continuity can be fruitfully extended to mathematical analysis within the realm of pure geometry.

As a result, Corrêa et al. [

10,

11] proposed the Alpha group theory, based on the notion of multiple types of infinities grounded in group theory and Cantor’s ideas [

5]. In Cantor set theory, a hierarchy of infinities is established. While infinity is often treated as an indeterminate concept, under a geometric and topological perspective, it can be associated with specific types of structured infinity. Cantor distinguished between potential infinity and actual infinity. The Alpha group, particularly through the introduction of the imaginary number

, relates to actual infinity, where geometric and topological structures are preserved.

Actual (or complete) infinity refers to infinity as a finished, completed quantity. It is treated as a concrete object or entity, one that exists as a complete “whole”, like a set that already contains an infinite number of elements [

4,

25].

[

10,

11], starting from group theory, demonstrated that the interaction of two infinite planes forms the Alpha group. These planes are connected by a transformation of the division operation, creating a third element with a morphism that preserves the algebraic structure of both. This construction yields a topological and geometric representation of infinity.

The hypercomplex quaternion structure defined in the Alpha group consists of four components: a real term , a complex term , a third term , and a fourth term , where and represent two distinct imaginary components. The division operation, formulated using two De Moivre arrays, results in a matrix involving tangent and cotangent relationships. This matrix varies topologically as the angle ranges from 0 to , inducing changes in the geometry.

At , the topology corresponds to the Euclidean space, whereas at , which corresponds to the Alpha group structure. Geometrically, at the infinite plane , a natural extension arises, revealing a higher-complexity structure where the local (Euclidean) space “opens up” to exhibit novel geometric behavior. A relevant characteristic of the Alpha group is its role as an asymptotic attractor, a concept that describes how systems evolve, often stabilizing into specific configurations or behaviors. In curved spaces, as studied in differential geometry, the tangent plane is a crucial tool for analyzing local curvature and its relationship to global spatial structure. The transition from local Euclidean space to infinite configuration implies that the tangent plane is acquiring a new geometry, one that is both topologically and symmetrically regular and capable of describing the transition to infinity.

2. Theoretical Framework

The imaginary number can capture properties associated with singularities, such as characterizing geometric symmetries through rotations induced by changes in the angle . These symmetry transformations can be invariant (conservative), as their topology may correspond to Euclidean topology locally and to the topology associated with the Alpha group globally. In the topology of the space defined by the Alpha group, the behavior varies according to the angle in the interval , suggesting a transition between local and global descriptions of space. At , the space is locally Euclidean, corresponding to a classical flat-space description. In contrast, at , the space becomes “infinite", approaching a global structure, such as the formation of a tangent plane.

This transition can be interpreted as an example of gauge theory [

41,

43,

45,

47]. Furthermore, the resulting matrix exhibits geometric properties associated with rotations and Lie algebra in four dimensions [

17,

19,

44].

In this work, we aim to explore the properties that arise from switching between rotations in four-dimensional space and rotations in two-dimensional planes (2D), as represented by the matrix

. We will present the symmetric and antisymmetric relationships of these rotations, as well as examine how combinations of shear and dilation change within a four-dimensional space (4D) in the context of the Alpha group. Additionally, within the context of the Alpha group, we conjecture a connection with gauge theory [

17].

3. Matrix Development and Properties

3.1. Foundations

De Moivre’s theorem served as the foundation for Murnaghan’s 1944 introduction of the quaternion theory. A complex number x+yi can be represented as a 2×2 square matrix using the following transformation [

30]:

As a result, De Moivre’s theorem can be expressed as follows:

The tensor division operation involving two matrices based on De Moivre’s formula can be used to generate elements of the Alpha group, even though the quaternion in the Alpha group can be composed of two complex planes using the equation in matrix form (2), which can be composed by dividing two matrices of type (2). Equation (

3) by Weyl [

49] [

12] illustrates how the division strategy is constructed in a similar way to the Kronecker product. There might be several methods to describe this operation; however, the solution of Equation (

3) naturally came from the relationship between the operators.

The matrix

can represent the dynamics of complex conjugate eigenvalues; consequently, this structure characterizes the existence of two coupled Hopf bundles. These results are a consequence of the representation of De Moivre’s matrix form of a classical complex number, in which the division operation generates the structure of its matrix

and the algebra of the Alpha group. The derivation can be demonstrated, starting from the matrix of De Moivre’s Theorem (2) ([

10] [

12] [

13] [

14]).

The matrix

, with its terms on the main diagonal

, concretely represents the algebra of the Alpha group. The diagonal elements anchor the essence of each "mode" of the system with its intrinsic properties (including imaginary aspects and the topological invariant

). This represents two simultaneous dynamics: one real (rotation) and the other imaginary (distortion or bifurcation). The matrix M(

) appears to be a non-Hermitian structure, with explicit dependence on the angular parameter

, and can be seen to generate internal vector variations. In the formulation of the Alpha group algebra, which can be defined as the multiplication of an angular matrix A(

) by another phase/amplitude matrix B(

).

The Alpha group matrix

can be interpreted as a structure that exhibits a coherent dynamic associated with the fibers of its complex eigenvalues. At certain critical points, especially for:

Regular discontinuities (smooth bifurcations or transitions), qualitative changes in the topological structure, and the emergence of dominant complex oscillatory solutions occur, coherently organizing space. These points function as natural rhythms of coherent alignment of fibers in higher-dimensional space.

3.2. Topological and Projective Definition of the Imaginary Number

We define as a novel mathematical entity, a topological and projective construct that emerges from the compactification of space in four dimensions. Unlike the classical imaginary unit i, which arises from the field of complex numbers and satisfies , the entity is not a number in the traditional algebraic sense, but rather a topological direction vector associated with the boundary of a compactified manifold.

In projective geometry, points at infinity serve to close the space, making parallel lines intersect and transforming open geometries into closed, homogeneous structures. Inspired by this principle, we introduce as a directional component representing the asymptotic behavior of space, the geometric "flow" as it approaches its ideal boundary.

The number

is defined by its behavior under angular transformations, which naturally manifests in the quaternionic formulation.

and interacts non-commutatively with

i, satisfying

. It represents a kind of imaginary axis that encodes the transition between local (Euclidean) and global (compactified) structure.

Geometrically, corresponds to a compactified radial direction, a vector field projected onto the boundary at infinity. Its projective nature allows it to be treated not just as a symbolic placeholder but as a carrier of structural information in higher-dimensional algebra. In this framework, serves as an asymptotic marker, characterizing deformations, attractors, and transitions in the global topology of space.

Therefore,

functions as a bridge between classical coordinate-based geometry and a new asymptotic structure geometric algebra, allowing the construction of the Alpha group and its associated transformations in

. We define

as an extended imaginary unit with hybrid topological-projective properties. Algebraically, it satisfies

and

, positioning it as a non-commutative and idempotent imaginary unit. Topologically,

serves as a projector in the compacted directions in

, representing a radial vector pointing to the ideal limit at infinity, consistent with Alexandroff compactification [

29] and projective closure. This endows

with dual functionality: it is simultaneously an algebraic generator and a topological operator, forming the backbone of the Alpha group structure. The operator

acts as a

topological projector, identifying all points in

that recede to infinity and collapsing the asymptotic boundary

into a single ideal point. Under this action,

is extended by this point and, by the Alexandroff compactification [

21][

29][

46], becomes homeomorphic to

. In this sense,

simultaneously performs the topological closure and the global projection

, establishing the compact structure required for the geometric and dynamical analysis developed in this work.

3.3. Verification of Quaternion Structure

To justify the term hypercomplex quaternion, we demonstrate that the proposed structure satisfies the fundamental properties.

3.3.1. Multiplication Rules

We define the relations between the imaginary units:

is an imaginary operator that acts on .

The non-commutativity with

i creates an algebra richer than that of complex numbers. It is possible to consider the algebra generated by

, where

i is the imaginary unit with

, and

introduces twists or projections. The structure of

as

performs a projective compactification of

into

, where

acts as a boundary operator. This echoes Weyl’s principle that global invariants emerge from local symmetries [

48][

12]. Interpreting

as an operator that, in the limit

, performs the projective closure of the four-dimensional Euclidean space into the four-sphere, one observes that the space imposes on the internal variables a direct perception of compactification. In the interior, symmetries manifest locally and are defined pointwise, but upon reaching the boundary through the action of

, invariant constraints arise that no longer depend on position, but solely on the global topology of the space. In this sense,

acts as a boundary operator that translates local structures in the interior into global topological features on the compactified boundary. This transition, in which local symmetries give rise to global invariants, is precisely the essence of Weyl’s principle: the overall structure emerges inevitably from the consistent extension and reconciliation of local symmetries across the entire compactified space.

3.4. Motivation for the Operator and Its Algebraic Rules

The operator plays a central role in defining the dynamic and topological structure of the Alpha group. Unlike standard imaginary units in classical complex analysis or quaternion algebra, is introduced with specific algebraic relations that reflect the nontrivial topology and geometric constraints of the underlying space.

Its algebraic rules are designed to encode a projective boundary operation, bridging the local geometry with global topological properties. These rules differ from classical imaginaries by producing emergent phenomena such as variable effective light speeds and nontrivial fiber bundle structures in the space.

Formally, satisfies postulates imposing anti-commutativity and nilpotency under certain compositions, distinguishing it from the quaternionic units . This gives rise to a novel group structure, the Alpha group, which generalizes and extends familiar algebraic frameworks, enabling the modeling of complex physical phenomena through its representation.

3.5. Comparative Analysis: The Alpha Group and Known Algebraic Structures

To better understand the uniqueness and role of the Alpha group, it is insightful to compare its properties with classical groups and algebraic structures, particularly the quaternion group and related Lie groups.

Table 1 summarizes key aspects such as algebraic relations, dimensionality, and topological characteristics.

This comparison highlights the distinct algebraic and topological features of the Alpha group, situating it within the landscape of well-studied mathematical structures while emphasizing its novel contributions to modeling complex topological dynamics.

3.5.1. Algebra Generated by

Consider the algebra generated by the set , where the elements satisfy the following relations:

From these, the multiplication table of algebra is:

Notably the relation or is consistent with the idempotent and non-commuting properties of and i.

This algebraic structure reflects the underlying metric properties, particularly the inverse relation between the components

and

of the metric tensor [

11], ensuring the compatibility of the operator

with the bilinear form preserved by the system associated with the matrix

. The bilinear form

associated with the metric tensor exhibits an antisymmetric component in the off-diagonal entries, particularly in the elements

and

:

This sign difference implies that the matrix is not symmetric, reflecting a structure with antisymmetric or skew-symmetric contributions.

Such antisymmetry plays a crucial role in defining the algebraic relations of the operators involved, notably impacting the preservation conditions of the bilinear form under the action of and the associated Clifford algebra structure.

In particular, the presence of inverse elements in these positions ensures consistency with the idempotent and non-commutative properties of the algebra generators, such as and i, linking the metric structure with the algebraic framework.

3.5.2. Matrix Representation

The matrix representation of the quaternion must satisfy:

where the matrices

satisfy:

3.5.3. Verification Example

For

and

, the product is given by:

3.5.4. Norm and Multiplicativity

Norm of the Alpha group Quaternion [

12], let the quaternion be defined as

with the respective components

, and imaginary numbers

i and

, where

3.6. Alpha Group Matrix Construction

In terms of trigonometric relationships, the tangent function, , is defined as the ratio of to , while its inverse function is the cotangent, . Alternatively, the tangent of an angle in a right triangle can be defined as the ratio between the length of the side opposite to and the length of the adjacent side.

These trigonometric relations can also be employed to substitute or represent division procedures in mathematical contexts. Specifically, the division of two complex planes results in matrix (3), which can be interpreted as a transformation into a matrix that belongs to a hypercomplex space.

The tensor division operation produces the following

an angular matrix A(

):

3.7. Symmetric and Antisymmetric Decomposition

Matrix (11) can be decomposed into a symmetric matrix

S and an antisymmetric matrix

. The symmetric matrix

S is given by the sum of matrix

M (5) and its transpose

. Thus, matrix

M itself decomposes into symmetric (

S) and antisymmetric (

) parts.

4. Rotations in Different Dimensions

4.1. 2D Rotations

In two dimensions (2D), the rotation of a vector can be described by a rotation matrix.

In matrix (8), theta () is the rotation angle; this matrix is orthogonal and preserves the norm of the vectors, rotating around the origin.

4.2. 3D Rotations

In three dimensions (3D), rotations occur on specific planes, such as the XY, YZ, or XZ plane. Each rotation can be described by a 3 x 3 matrix, such as:

This matrix (9) generates a rotation in the XY plane along the Z axis.

4.3. 4D Rotations in Alpha Group

We obtain, as a result, the decomposition of the original matrix

into the sum of a symmetric matrix

S and an antisymmetric matrix

, such that:

as shown in [

15]. This decomposition represents the structure of the original matrix

M.

The complete 4D transformation matrix:

The matrix

results in a hyperboloid, in this case for a hyperbolic geometry topology, in which its asymptotes close at infinity and its lines and surfaces behave differently from Euclidean geometry, especially in terms of negative curvature. The concept of closed hyperbole deals with a geometry in which the asymptotes, instead of spreading infinitely openly, "close" at infinity. This can be interpreted as a special compactification of hyperbolic space, where the asymptotic behavior is treated in a manner that preserves the system’s symmetry. These enhanced asymptotes create a specific topological structure, where the emerging symmetries have both global and local characteristics. The idea of an infinity-closed hyperbole suggests a type of compactification that preserves local properties of hyperbolic geometry but at the same time closes the system topologically at the asymptotic limit, [

20,

33], and [

28]. This may be related to topologies such as the anti-de-sitter space ([

22,

50], and [

39]), where the negative curvature of space creates specific asymptotic behavior and global symmetries are preserved even at infinity. Moreover, this compactification may allow the global characteristics of space to be treated continuously and homogeneously, without uniqueness or divergent behaviors, which is common in theories that involve infinity, as in cosmological models or string theory ([

1,

34], and [

3]). The topology that characterizes the numerical space of the Alpha group is generated by the variation of the angular ratio

within the hypercomplex quaternion. The definition of an abstract geometric point is linked to the existence of the imaginary number

at infinity. In our case, this existence induces an asymptotic global attractor in the topology, represented by the general expression:

where

.

The Alpha group features a transformation nucleus, described by matrix (3), which defines a tensor. Additionally, the presence of the imaginary number has significant implications for geometry and topology, especially at the critical points and radians. Projective compactification is a powerful method for treating infinity in geometry, bringing points at infinity to the boundary of a finite domain. In the context of the Alpha group, this approach rigorously formalizes the number as a boundary operator, encapsulating the asymptotic behavior of the space. In the intervals between these points, the number is not infinite but behaves as a polynomial function associated with the asymptote of a hyperbola, where the hyperbola geometrically closes at the point of infinity. In the framework of Lie algebras, the rotations induced by the operator depart from the classical structure due to the presence of non-orthogonal components, such as terms involving and the introduction of a non-commutative operator . This operator plays a central algebraic and topological role, particularly at the critical value , where the condition emerges. This relation defines a topological idempotent and introduces a fixed-point structure in the extended space. Consequently, becomes compactified into a projective manifold, establishing topological invariants that transcend the boundaries of classical Lie group frameworks such as .

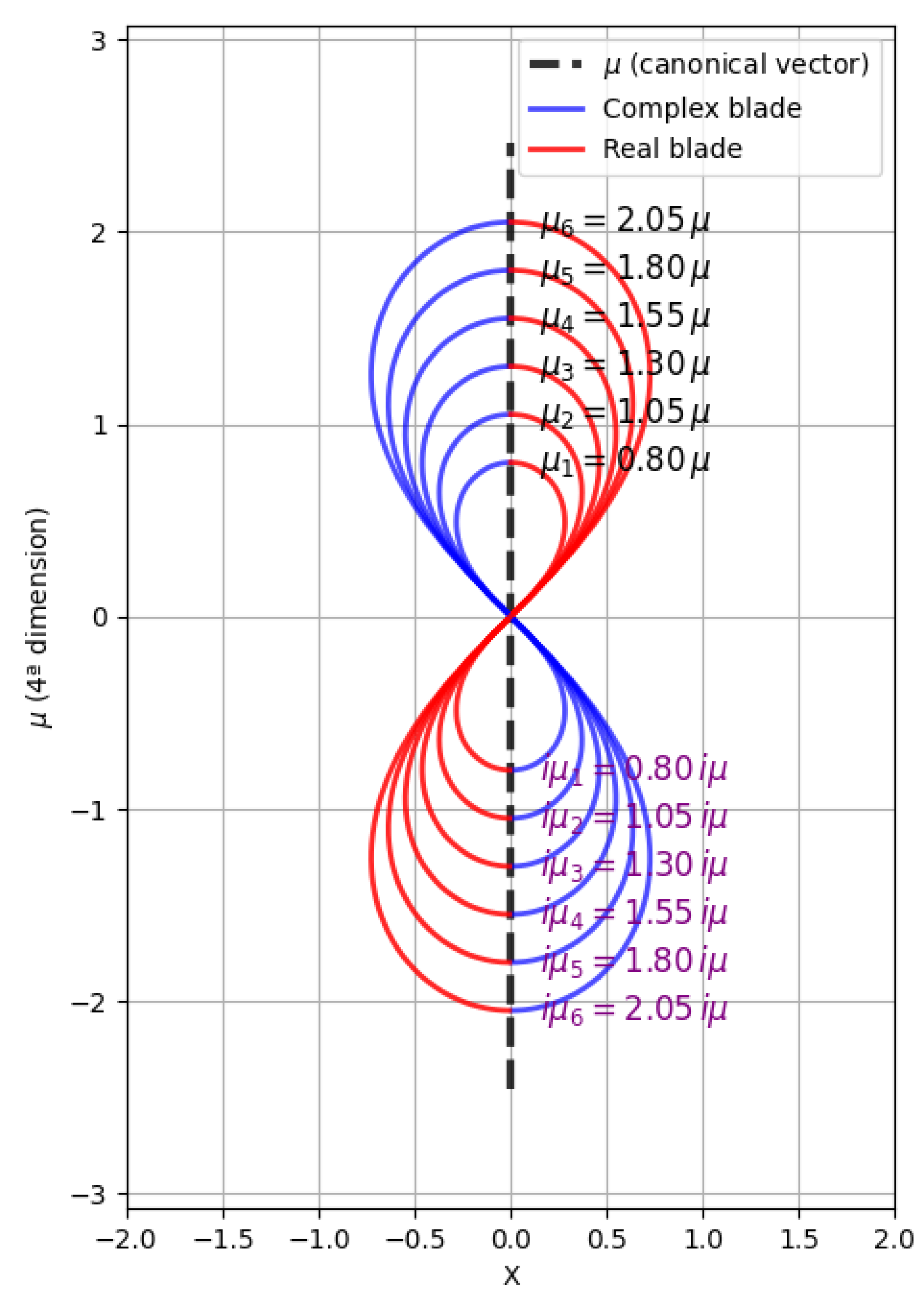

The imaginary number can be interpreted as a mathematical artifact that encapsulates transformations occurring at singular points. These deformations are associated with a canonical imaginary vector , which generates a revolving surface, a type of attractor in , associated with the tangent plane at radians.

This kind of transformation may be related to concepts such as vibrated and complex varieties. Nevertheless, when approaching the angles radians, the topology exhibits characteristics of the Euclidean metric space (locally). In contrast, near radians, a tangent plane emerges with the global topology defined by the Alpha group.

This geometric structure of the Alpha Group, characterized by a hyperbolic topology, is illustrated in

Figure 1. It shows a visualization of how the topology of a space manifests under the influence of a canonical vector, where the shape and connectivity of the "sheets" depend on the direction and magnitude of

, characterizing an anisotropic topology.

4.4. Dynamical Behavior of the Alpha Group Matrix

[

14] investigates the dynamical behavior of a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) governed by the Alpha group matrix

. An algebraic structure that combines geometric and topological properties in four-dimensional spaces.

Through numerical simulations using the Runge-Kutta method in Python, the authors demonstrate how the rotational parameter controls transitions between distinct topological regimes: a stable Euclidean space () and a global attractor at infinity (), associated with hyperbolic deformations and the imaginary number .

The results, analyzed through Poincaré maps, Lyapunov functions, and bifurcation diagrams [

14], suggest connections with gauge theories and local/global symmetries. These findings highlight the role of the matrix

as a generator of complex geometric transformations in high-dimensional spaces. The Alpha group functions as an algebraic operator, which, when acting on

, generates a fiber bundle structure with deep topological dynamics. This creates a conceptual bridge with fiber bundle constructions in differential geometry, Penrose’s twistor theory [

31] [

32], and Maldacena’s holographic correspondences [

28], placing the Alpha group within a contemporary research context in mathematical physics, geometry, and field theories.

4.5. Relation of the parameter to known mathematical structures

The parameter introduced in our model plays a crucial role in defining the algebraic and topological properties of the dynamic matrix . To contextualize its originality and mathematical foundation, it is useful to relate to known objects in algebra and geometry.

In particular,

can be interpreted in analogy with idempotent elements in Clifford algebras, which serve as projectors onto specific subspaces and encode geometric information in noncommutative settings [

40] [

27]. Clifford algebras provide a rich algebraic framework where such idempotents correspond to minimal ideals, enabling the decomposition of complex geometric structures.

Furthermore, the role of

resonates with concepts in noncommutative geometry, where deformation parameters modulate the algebraic relations and give rise to novel topological invariants. This connection suggests that

acts as a deformation or coupling parameter, influencing the emergent topological features captured by persistent homology and the associated dynamical behavior [

8] [

18].

By situating within these well-established mathematical frameworks, our approach gains both a rigorous grounding and a pathway to explore extensions in the context of algebraic topology, operator algebras, and geometry. This highlights the originality of our model in bridging dynamic systems with advanced algebraic structures, paving the way for novel insights in topological dynamics. In contrast to the Clifford algebra, where the angles between generating vectors are fixed and determined by a constant quadratic form, the algebra of the Alpha group exhibits a richer geometric structure with angle relations that vary dynamically as a function of a parameter . Specifically, in the Alpha group algebra, the angles between the generators are not constant but depend continuously on , reflecting a non-trivial topology that undergoes compactification at critical values , with . This results in an anisotropic topology where geometric properties vary with position in parameter space, contrasting with the isotropic and homogeneous geometry associated with Clifford algebras. Such topological anisotropy introduces novel algebraic and geometric features, enabling the Alpha group algebra to generalize and extend the classical framework of Clifford algebras.

4.6. Generalization of Classical Rotations

The matrix generalizes classical rotational transformations in by extending beyond the orthogonal structure of the Lie group . Unlike classical rotations, which preserve inner products and obey strict commutation relations, incorporates non-orthogonal components, particularly through terms such as and interacts with the non-commutative operator . This structure exhibits self-coherent dynamics that give rise to a topological regime, where classical rotational symmetries are replaced by a geometry dependent on the fiber structure. As , the transformation deviates maximally from orthogonality, and the system transitions into a topologically compact phase governed by the condition .

5. Methodology

To analyze the dynamic behavior of the system governed by the Alpha group matrix, we developed a numerical simulation framework in Python, following the methodology described below. We define a parameterized matrix

, based on trigonometric relations involving the angle

. This matrix incorporates the imaginary unit

i and a projective imaginary component

, as proposed in the Alpha group theory. Its structure is given by:

where

,

, and

. In the simulations, we adopt

as a representative case.

5.0.1. Symmetric and Antisymmetric Decomposition

To better understand the geometric structure of

, we perform a decomposition into Hermitian (symmetric) and anti-Hermitian (antisymmetric) parts:

where

denotes the conjugate transpose of

M. This decomposition separates dilation/shear components (

S) from rotational dynamics (

A) in the four-dimensional space.

5.0.2. Monte Carlo Simulation

The Monte Carlo analysis was performed by systematically varying the parameter

in a symmetric range around zero and, for each value, generating multiple stochastic realizations of the system dynamics. For each

, the associated transition matrix

was constructed and used to evolve a complex-valued 4-dimensional state vector under additive Gaussian noise. The resulting trajectories, normalized at each step to control growth, were downsampled and projected to three dimensions via Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to preserve the dominant geometric features while reducing computational cost. The one-dimensional Betti number

was then estimated from the embedded point cloud using persistent homology (via the

Ripser library), quantifying the loop-like structures in the state-space geometry. By repeating the process for multiple independent trajectories per

, the Monte Carlo approach yielded statistical estimates of the mean and standard deviation of

, thus capturing the topological variability of the dynamics across parameter values. Concurrently, the Lyapunov exponent was computed from the same transition matrices to characterize the average exponential rate of divergence or convergence of nearby trajectories. This dual analysis provides a comprehensive view of the system’s geometric and dynamical complexity as a function of

. We simulate the evolution of a state vector

, starting from a random initial condition. At each time step, the matrix

is applied, along with stochastic perturbations:

where

is Gaussian noise, and

denotes the real part. To prevent divergence due to repeated amplification, the state vector is normalized at every step:

where

is a small constant to avoid division by zero, [

2,

42] and [

24].

This process is iterated over time steps to capture long-term behavior and asymptotic tendencies. This Python script uses the NumPy and Matplotlib libraries to simulate and visualize the properties of the Alpha Group. The main functions and libraries are:

numpy as np: Used for numerical operations, such as creating matrices, handling complex numbers, and manipulating vectors. NumPy is essential for defining and decomposing the matrix , as well as for Monte Carlo simulations.

matplotlib.pyplot as plt: Used to create trajectory plots, including three-dimensional visualizations.

mpl_toolkits.mplot3d.Axes3D: Provides the necessary tools for plotting graphs in three dimensions.

matplotlib.cm: Allows the use of colormaps, such as plasma, to color trajectories based on time evolution.

def monte_carlo_simulation(theta, steps=100000): defines a function that performs a Monte Carlo simulation based on a given parameter . The optional argument steps sets the number of iterations (default: 100,000). This function typically generates random trajectories or samples according to a stochastic process, allowing the study of dynamic behavior or statistical properties of a system as a function of .

5.0.3. 3D Projection and Visualization

Although the simulation occurs in four dimensions, we project the trajectory into 3D space for visualization. The projection is performed using the first three components of the vector , and colored temporally to emphasize the system’s evolution. The initial and final points of the trajectory are also highlighted to provide insight into attractor behavior.

5.0.4. Parameter Sweep and Boundary Regimes

We conduct simulations for multiple values of , capturing different topological regimes:

: approximates a locally Euclidean structure,

: intermediate topology with rotational coupling,

: represents the compactified boundary, associated with hyperbolic topology and attractor-like behavior.

6. Results

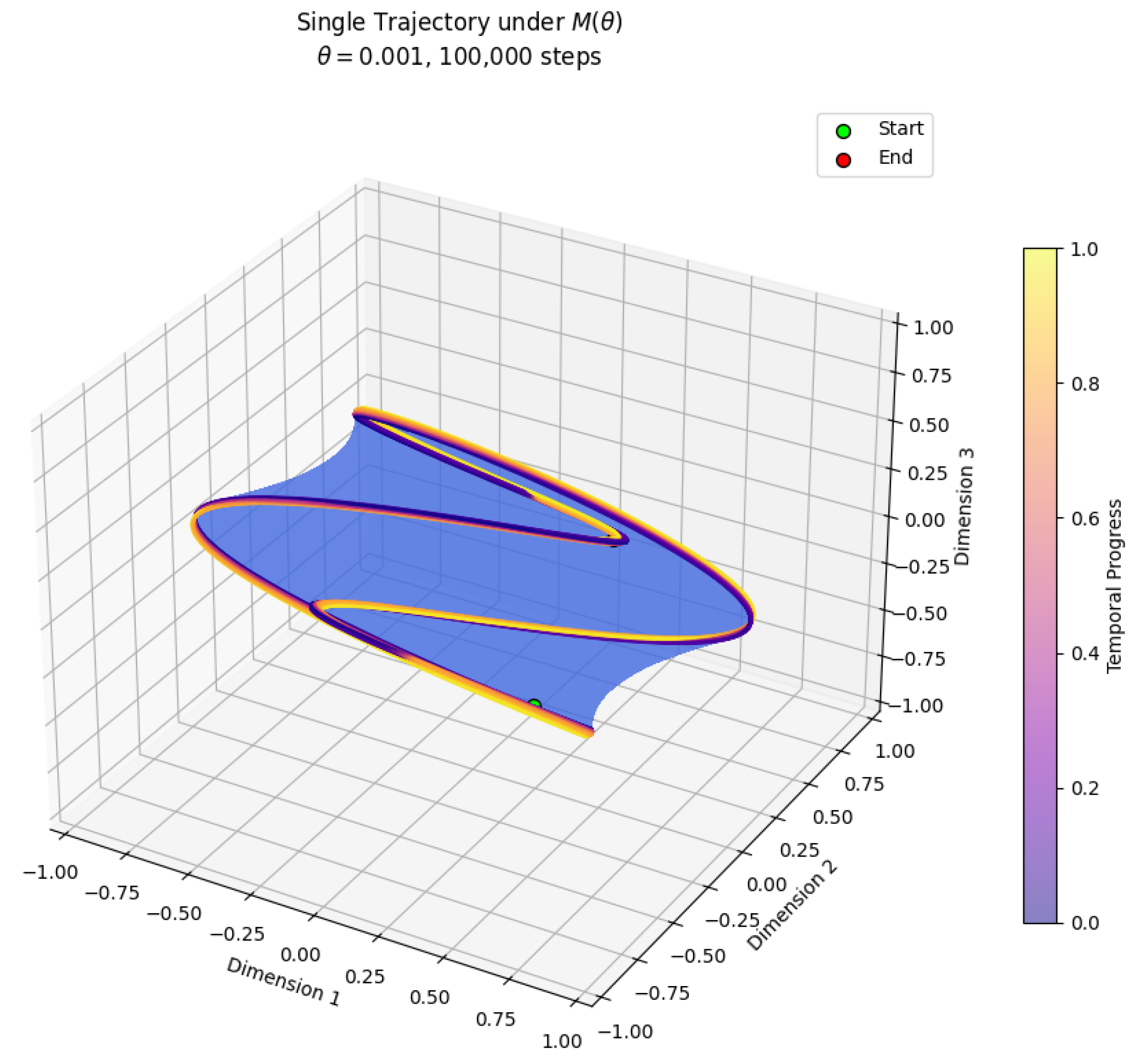

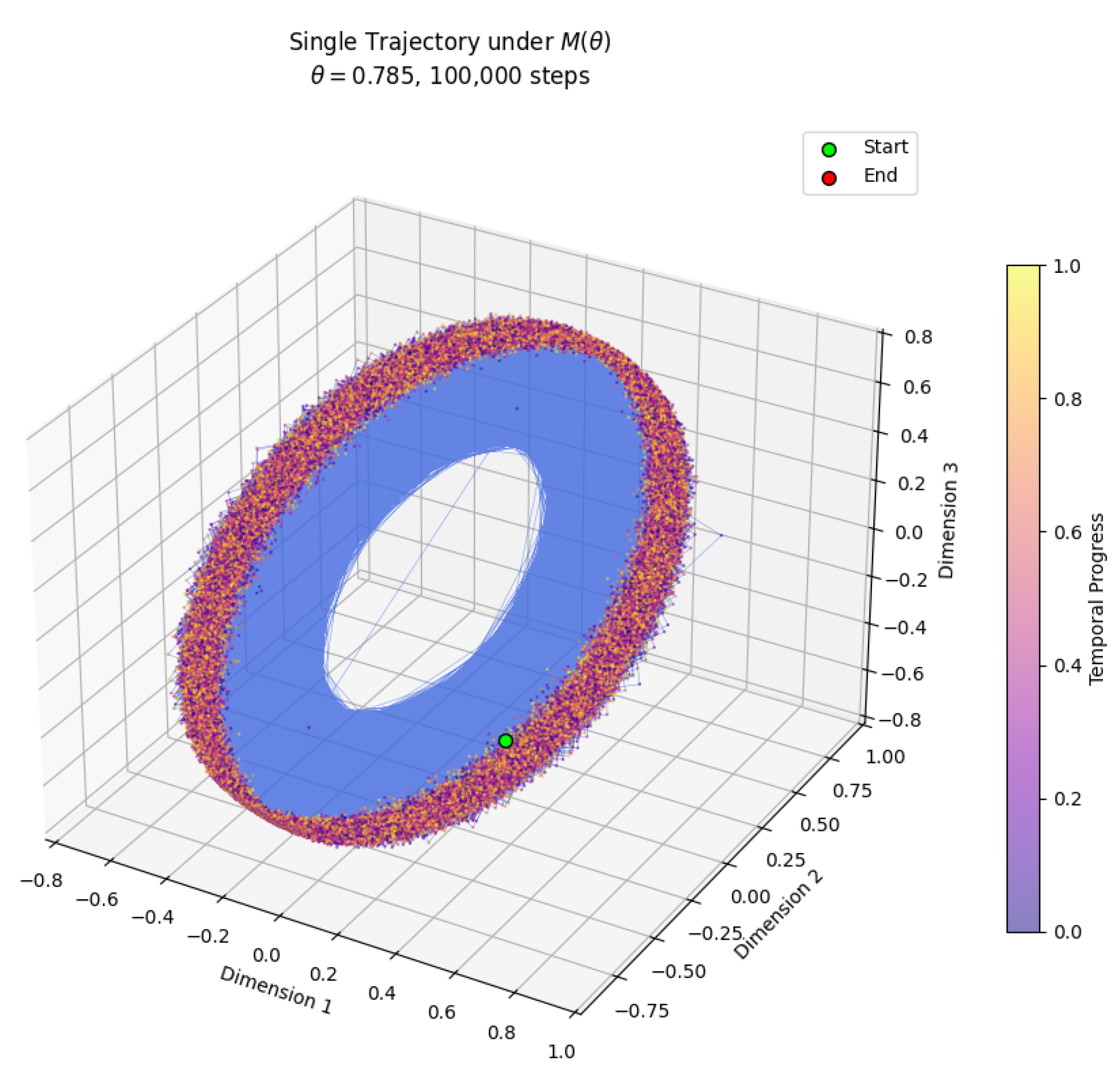

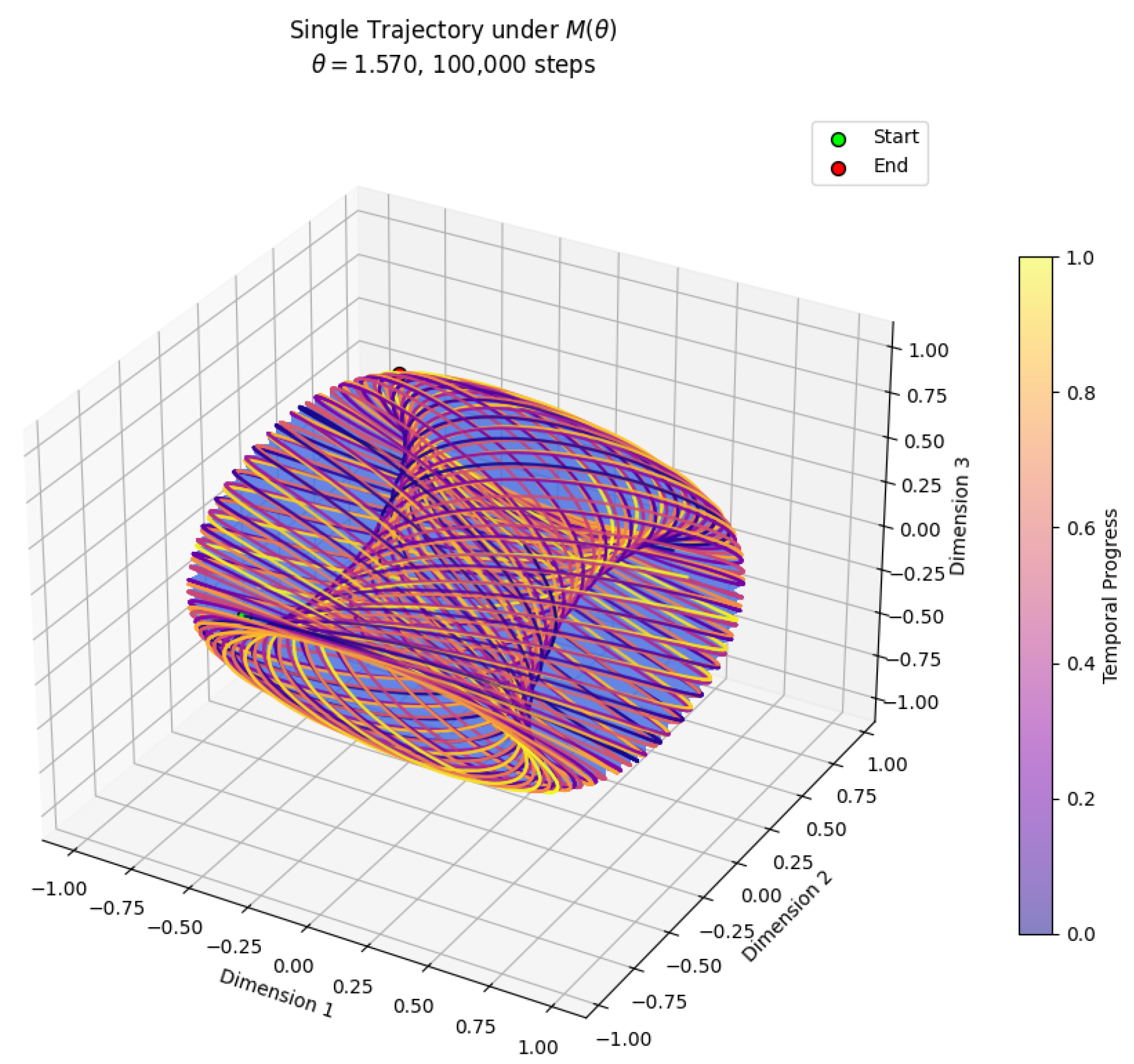

To illustrate the dynamic behavior induced by the matrix

, we present the results of the Monte Carlo simulations for three representative values of the parameter

: near zero (

), intermediate (

), and near the asymptotic boundary (

). In all cases, the simulation was performed with 100,000 steps, using a normalized 4D state vector perturbed by Gaussian noise. The results of the Monte Carlo simulation can be seen in

Figure 2.

6.1. Singularity at and the Topology Transformation

At

, the Alpha Group matrix

reaches a

controlled singularity, where the trigonometric terms diverge as:

This singularity is not treated as a mathematical anomaly, but rather as a fundamental topological transition point between two distinct four-dimensional configurations.

6.2. The Role of the Vector as an Infinity Operator

The imaginary number

introduced in the Alpha Group formulation plays a central role as a

topological operator of infinity. It’s an algebraic property of idempotence,

makes it act as a

topological projector, selectively identifying and compactifying directions that tend toward infinity within

. In the conventional Clifford algebra framework [

16][

27][

23], the operator

satisfies the relation

, consistent with its role as an imaginary generator in a real four-dimensional space. However, within the internal dynamic geometry introduced in this work, the behavior of

becomes dependent on the coherence parameter

. Notably, in the limit

, the algebraic identity transitions to

, indicating a breakdown of the Clifford structure and the emergence of an idempotent, topologically invariant phase. This change reflects a compactification mechanism whereby the geometry ceases to be locally Euclidean and instead projects into a globally coherent manifold characterized by a universal topological constant.

Topological Bundles

Bundle over (local): For small , the geometry reflects Euclidean behavior and quaternionic symmetry, consistent with -based fiber bundles.

Bundle over (global): At , the vector induces a compactification along a radial dimension, effectively transforming the ambient space from into the 4-sphere by the inclusion of a single point at infinity.

This compactification process aligns with classical topological methods that transform infinite domains into bounded manifolds while preserving continuity and differentiable structures (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

6.3. Regime Change Analysis in

Numerical analysis reveals that, for values of

close to

, the dynamic matrix

exhibits a particularly rich regime. In this range, the eigenvalues become complex, and the imaginary part dominates the complex vector dynamics, indicating the activation of resonant oscillatory modes. This condition leads to the occurrence of two coupled Hopf bifurcations, producing states of high coherence in the system’s temporal evolution (

Figure 5).

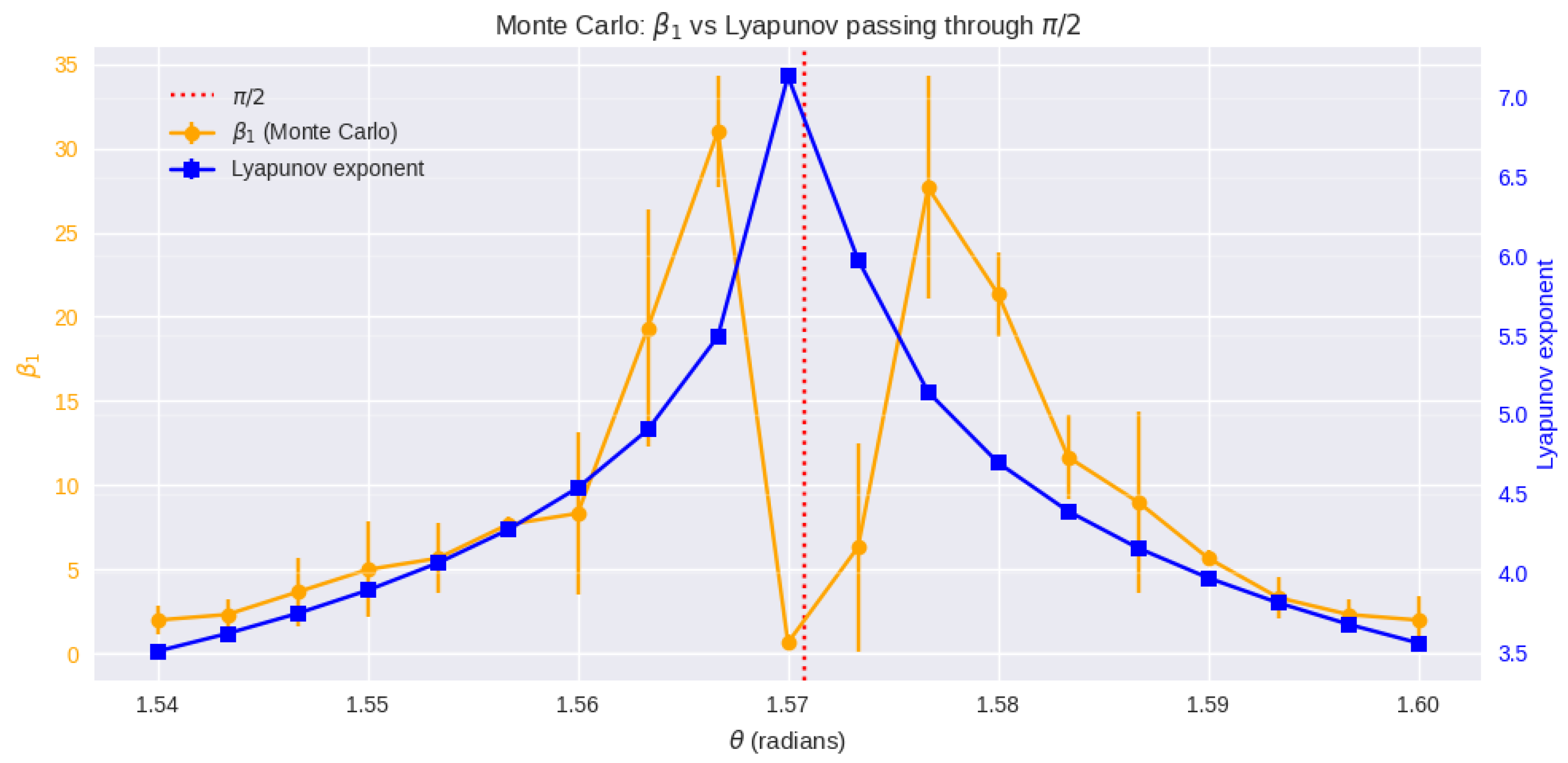

The interval of around in which this resonance is observed is relatively narrow. However, exactly at and slightly above , the Lyapunov exponent shows a significant increase, evidencing exponential sensitivity to initial conditions and characterizing the transition to a chaotic regime. Remarkably, as moves further away from , the system transitions back from chaos to a coherent resonant state, revealing a window of restored coherence after the chaotic burst.

Thus, the point

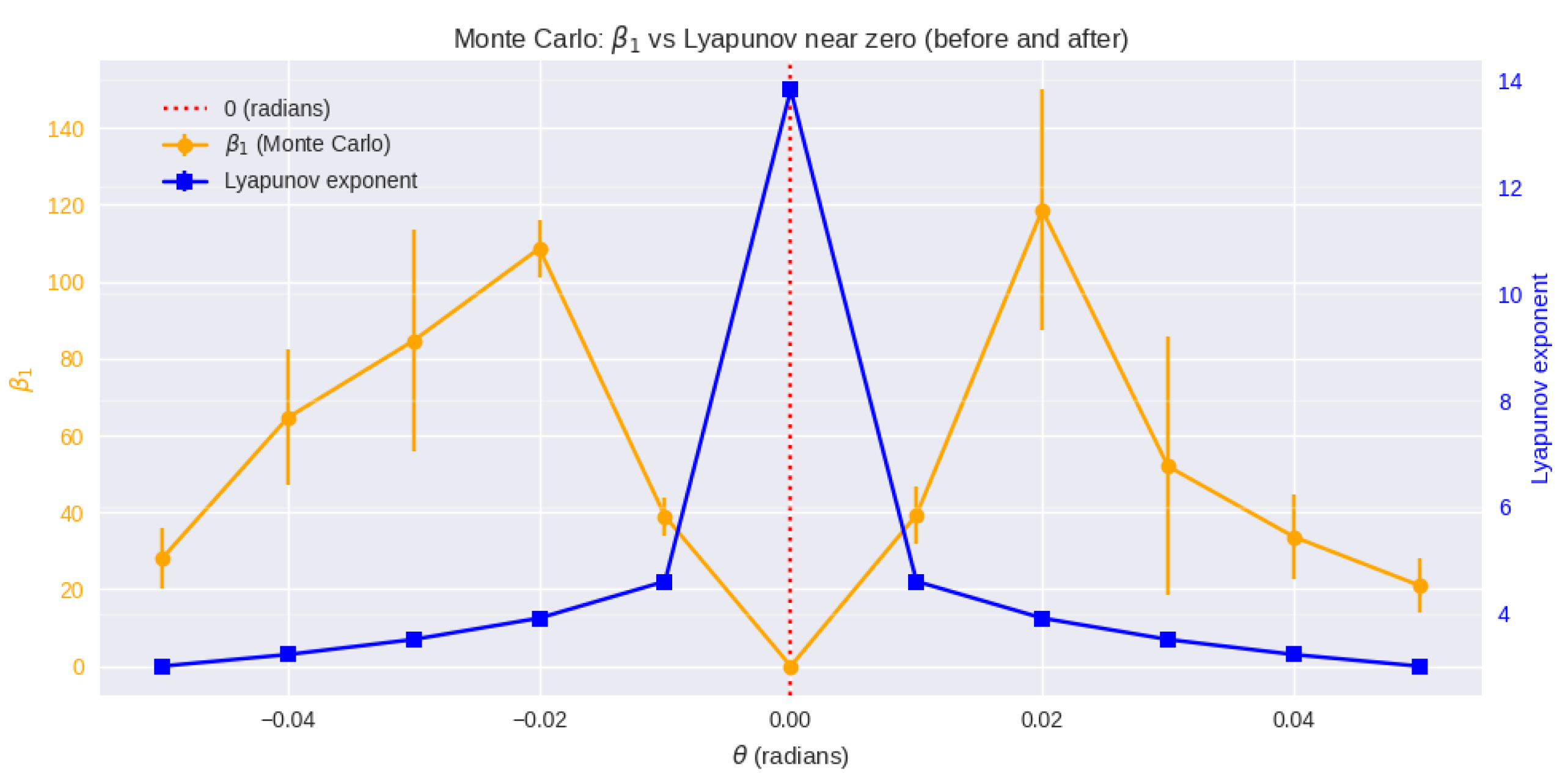

acts as a topological–dynamical threshold, marking the passage from a coherent resonant state to chaos, and then back to coherence, with amplified instability in the chaotic phase. As illustrated in

Figure 6, the Monte Carlo simulation at zero radians reveals a clear relationship between the Lyapunov exponent and the Betti number

. This comparison highlights the presence of chaotic yet dynamically stable behavior confined to planar subspaces.

In the regime near , the system exhibits a strange attractor characterized by chaotic behavior, as evidenced by a positive Lyapunov exponent. However, it displays globally stable dynamics confined to linear subspaces, or flat planes, reflecting the locally Euclidean topology of the space. This dynamical stability despite chaos implies that the system tends to evolve within a compact and coherent domain, where trajectories remain organized into simple structures.

On the other hand, for , the system corresponds to the Alpha group, which exhibits a globally nontrivial topological structure. In this regime, the attractor also manifests chaotic behavior, but with an extended and global dynamics that propagates throughout the entire dynamical space, reflecting the global characteristics and topological complexity of the Alpha group. This results in more dispersed trajectories and a dynamical field with variable directions, evidencing that the dynamics is less confined and structurally richer than in the locally Euclidean case near zero, including the presence of internal geometric vector dynamics such as resonance and coupled Hopf bifurcations (complex eigenvalues with imaginary part dynamics dominate).

6.4. Numerical Validation and Error Analysis

The Monte Carlo simulations presented were tested for numerical stability and convergence. Temporal discretization was performed with a time step chosen to ensure that the oscillatory modes induced by the complex eigenvalues of were adequately resolved. Convergence tests were carried out by halving and verifying that the Lyapunov exponent and the spectral properties of varied by less than .

Statistical convergence was verified by increasing the sample size N of the Monte Carlo ensemble from to realizations, showing stabilization of the mean and variance within the statistical error bounds. The sensitivity to initial conditions was tested by perturbing initial states by , confirming the robustness of the observed Hopf bifurcations and chaotic regimes.

7. Conclusion

From the main characteristics of the matrix , we can interpret the following considerations: the values 1 and on the main diagonal indicate expansions or contractions along the corresponding coordinate axes.

When , there are no additional expansions or contractions in the other directions. However, if , then an expansion or contraction occurs in the direction corresponding to the axis associated with this diagonal entry.

The elements outside the main diagonal with 1 and -1 indicate a shear (or distortion) of the space. This means that by applying the transformation represented by the S matrix, vectors that are not aligned with the main axes will be distorted or sloped. Changing your topology. Therefore, the symmetric transformation S does not represent a pure rotation. A pure rotation is usually represented by an orthogonal matrix (in the actual case, with the entry that preserves the vector pattern). However, symmetrical matrices, such as the matrix we have obtained, are not orthogonal and therefore do not represent pure rotations. The matrix S represents a combination of shear and dilation in a four-dimensional (4D) space. The formation of the Alpha Group is driven by rotations within the matrix , which occur between planes at angles radians.

It is possible to modify the metric deformations of the tensor by selecting different internal angles during the construction of hyper-complex quaternions. In such spaces, rotation can be visualized as a transformation that preserves the complex structure, maintaining the relationship between the real and imaginary components of the coordinates.

Inclusion of the imaginary unit introduces additional complexity, where complex topology and geometry become essential elements. The geometry of the Alpha group incorporates the new topological and geometric properties that emerge from these transformations, offering a novel framework for understanding rotations and deformations in higher-dimensional spaces.

8. Final Considerations

This framework could unify classical geometry with a model in which the matrix represents dilations, contractions, and shears, as it could connect linear algebra and geometric transformations with deeper symmetry structures, such as those found in Gauge theory and Lie groups. Conformal transformations can be seen as representations of symmetry groups that act on a geometric space. These transformations would allow one to continuously map geometric objects, preserving certain properties (such as angles or lengths) or modifying them in a controlled manner (as in dilations or contractions). This development could be related to the principal fiber bundles in gauge theory, in which their local transformations would be applied in a geometric space. Matrix (3), in this sense, could act as an algebraic tool to connect the symmetry of classical geometry to the most general transformations that occur in Gauge spaces. The number leads to a global attractor within a stable, closed hyperbolic geometry, where the asymptote of the hyperbola converges at infinity. This suggests a novel topological structure and rich in symmetrical structures. This configuration is directly connected to the concepts of topological compactification, global asymptotic behavior, and stable field solutions, offering a new framework for understanding both geometry and field theory on large scales.

In this work, we propose the notion of a dynamic internal vectorial geometry as a necessary condition for the emergence of a topological structure homeomorphic to near . In this regime, the operator satisfies the identity , thus acting as a topologically invariant and idempotent element, which we interpret as a universal topological constant characterizing the projected manifold. This approach can provide a deeper geometric interpretation of physical phenomena by unifying concepts from differential geometry with the algebraic structure of associated symmetry and antisymmetry transformations, encompassing both local variations and global topological structures. These results may lay the foundation for clarifying and understanding the algebraic and topological structures underlying the dynamics of the Alpha group. Although this work establishes the fundamental framework, numerous possibilities remain open for further exploration, including a more detailed characterization of the Clifford algebra structure and its automorphisms for variable parameters. These possible directions promise valuable insights and will certainly be the subject of future research.

References

- BAILIN, David; LOVE, Alexander. Cosmology in gauge field theory and string theory. Taylor & Francis, 2004.

- BINDER, Kurt (Ed.). Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations in polymer science. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- BLUMENHAGEN, Ralph; LÜST, Dieter; THEISEN, Stefan. Basic concepts of string theory. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- BROWN, Anne; MCDONALD, M.; WELLER, Kirk. Step by step: Infinite iterative processes and actual infinity.

CBMS Issues in Mathematics Education, v. 16, p. 115-141, 2010.

- CANTOR, Georg. Contributions to the Founding of the Theory of Transfinite Numbers (No. 1). Open Court Publishing Company, 1915.

- CHASLES, Michel. Aperçu historique sur l’origine et le développement des méthodes en géométrie: particulièrement de celles qui se rapportent à la géometrie moderne, suivi d’un mémoire de géométrie sur deux principes généreaux de la science, la dualité et l’homographie. M. Hayez, 1837.

-

CHAVES, Jansley Alves; GRIMBERG, Gerard Emile. Os pontos imaginários nas obras de Poncelet, Chasles e Lague. Llull: Revista de la Sociedad Española de Historia de las Ciencias y de las Técnicas, v. 43, n. 87, p. 69-98, 2020. [CrossRef]

- CONNES, Alain; CUNTZ, Joachim; RIEFFEL, Marc A. Noncommutative geometry. Oberwolfach Reports, v. 6, n. 3, p. 2271-2334, 2010.

- CORRÊA, C. S. The-Alpha-group: Numerical Simulations and Data, GitHub repository, 2025. Available at: https://github.com/CleberCorrea15/The-Alpha-group.

- CORRÊA, Cleber, S.; de MELO, Thiago, B.; CUSTODIO, Diogo. M.. Proposing the Alpha Group. International Journal for Research in Engineering Application & Management (IJREAM). Volume 08, Issue 05. 2022. [CrossRef]

- CORRÊA, Cleber, S.; de MELO, Thiago, B.; CUSTODIO, Diogo. M.. The Alpha Group Tensorial Metric. Revista Brasileira de História da Matemática (RBHM), v. 24, nº 48, p. 51-57, 2024. [CrossRef]

- CORRÊA, Cleber, S. & MELO, Thiago, B. N. de. (2025). Division as a radial vector relationship – Alpha group. STUDIES IN ENGINEERING AND EXACT SCIENCES, 6(1), e16083. [CrossRef]

- CORRÊA, Cleber Souza; DE MELO, Thiago Braido Nogueira. Multiscale topology and dynamic internal vectorial geometry-alpha group. Studies in Engineering and Exact Sciences, v. 6, n. 1, p. e17403-e17403, 2025. [CrossRef]

- CORRÊA, Cleber, S. & MELO, Thiago, B. N. de. (2025). The Alpha Group Dynamic Mapping. 2507.18303. arXiv, math.DG. https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.18303.

- DAS, Ashok; OKUBO, Susumu. Lie groups and Lie algebras for physicists. World Scientific, 2014.

- DELANGHE, R.; SOMMEN, F.; SOUCEK, V. Clifford algebra and spinor-valued functions, vol. 53 of Mathematics and its Applications. 1992.

- GILMORE, Robert. Lie groups, Lie algebras, and some of their applications. Courier Corporation, 2006.

- GRACIA-BONDÍA, José M.; VÁRILLY, Joseph C.; FIGUEROA, Héctor. Elements of noncommutative geometry. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- HALL, Brian C. Lie groups, Lie algebras, and representations. Springer New York, 2013.

- HAWKING, Stephen W.; ELLIS, George FR. The large-scale structure of space-time. Cambridge University Press, 2023.

- HAYASHI, Eiichi. One-point expansion of topological spaces. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, v. 34, n. 2, p. 73-75, 1958.

- HENNEAUX, Marc; TEITELBOIM, Claudio. Asymptotically anti-de Sitter spaces. Communications in Mathematical Physics, v. 98, p. 391-424, 1985.

- HESTENES, David; SOBCZYK, Garret. Clifford algebra to geometric calculus: a unified language for mathematics and physics. Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- LANDAU, David; BINDER, Kurt. A guide to Monte Carlo simulations in statistical physics. Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- LEON, Antonio. Infinity, Language, and Non-Euclidean Geometries. The General Science Journal, v. 173, p. 174, 2023.

- LOUD, F. H. “A Construction for the Imaginary Points and Branches of Plane Curves.” Annals of Mathematics 8, no. 1/6 (1893): 29–37. [CrossRef]

- LOUNESTO, Pertti. Clifford algebras and spinors. In: Clifford algebras and their applications in mathematical physics. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2001. p. 25-37.

- MALDACENA, Juan. The large-N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. International journal of theoretical physics, v. 38, n. 4, p. 1113-1133, 1999.

- MUNKRES,J. R. Topology, 2nd Edition, Prentice Hall, 2000.

- MURNAGHAN, F.D. An elementary presentation of the theory of quaternions, Scripta Math., 10, 37-49.1944.

- PENROSE, Roger. Twistor algebra. Journal of Mathematical Physics, v. 8, n. 2, p. 345-366, 1967.

- PENROSE, Roger; MACCALLUM, Malcolm AH. Twistor theory: an approach to the quantisation of fields and space-time. Physics Reports, v. 6, n. 4, p. 241-315. 1973.

- PENROSE, Roger. Republication of: Conformal treatment of infinity. General Relativity and Gravitation, v. 43, n. 3, p. 901-922, 2011.

- POLCHINSKI, Joseph. What is string theory?. arXiv preprint hep-th/9411028, 1994.

- PONCELET, Jean Victor. Essai sur les propriétés projectives des sections coniques. Présenté à Académie des Sciences de Paris, 1820.

- PONCELET, Jean Victor. Applications d’analyse et de géométrie: traité des propriétés projectives des figures. Mallet-Bachelier, 1862.

- PONCELET, Jean Victor. Applications d’analyse et de géometrie, qui ont servi, en 1822, de principal fondement au Traité des propriétés projectives des figures... comprenant la matière de sept cahiers manuscrits redigés à Saratoff... annotés par l’auteur et suivis d’additions par MM. Mannheim et Moutard. 1864.

- PONCELET, Jean Victor. 1866 Traite des proprietes projectives des figures: ouvrage utile `a ceux quis’ occupent des applications de la geometrie descriptive et d’operations geometriques sur le terrain, Vol. 2, Gauthier-Villars.

- PORRATI, Massimo. Higgs phenomenon for 4-D gravity in anti-de Sitter space. Journal of High Energy Physics, v. 2002, n. 04, p. 058, 2002.

- PORTEOUS, Ian R. Clifford algebras and the classical groups. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- QUIGG, Chris. Gauge theories of strong, weak, and electromagnetic interactions. CRC Press, 2021.

- ROSENBLUTH, Marshall N.; ROSENBLUTH, Arianna W. Monte Carlo calculation of the average extension of molecular chains. The Journal of Chemical Physics, v. 23, n. 2, p. 356-359, 1955.

- ROTHE, Heinz J. Lattice gauge theories: an introduction. World Scientific Publishing Company, 2012.

- SAN MARTIN, Luiz AB. Lie groups. Cham: Springer, 2021. ISBN 978-85-268-1356-4.

- TAYLOR, John C. Gauge theories. Gauge Theories in the Twentieth Century, p. 381, 2001.

- WASILESKI, J. S. On Alexandroff base compactifications. Canadian Journal of Mathematics, v. 29, n. 1, p. 37-44, 1977.

- WEYL, Hermann. Gravitation und elektrizität. Sitzungsber. Preuss. Akad. Wiss, v. 26, p. 465-478, 1918.

- WEYL, Hermann. Space–time–matter. Dover Publications Incorporated, 1922.

- WEYL, Hermann. Algebraic theory of numbers. Princeton University Press, 1998.

- WITTEN, Edward. Anti-de Sitter space and holography. arXiv preprint hep-th/9802150, 1998.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).