Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Voters as Bayesian Learners: Voters possess prior beliefs that are updated through the processing of noisy signals, received with a certain probability. They iteratively refine their understanding of political performance based on available, albeit imperfect, information.

- Politicians as Strategic Actors: Motivated by career advancement, politicians operate within a repeated game framework characterized by moral hazard. Their prospects for re-election are contingent upon past performance, with first-term politicians exhibiting heightened effort due to their greater electoral vulnerability.

2. Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Sequential Rationality and Cumulative Knowledge

2.2. The Base Model

2.2.1. Notation and Assumptions

- : The population’s prior belief that the elite is of high type before any interaction occurs.

- : A noisy signal about the elite’s type observed by the population before the first election. The quality of the signal is determined by the likelihood .

- : The level of electoral fraud chosen by the elite, where 0 means no fraud and 1 means maximum fraud.

- : campaign promises made by the elite, which can be a vector or a scalar quantity.

- : The probability that the incumbent elite wins the first election. This probability increases with the level of fraud, the population’s updated belief about the elite being a high type, and the attractiveness of promises :

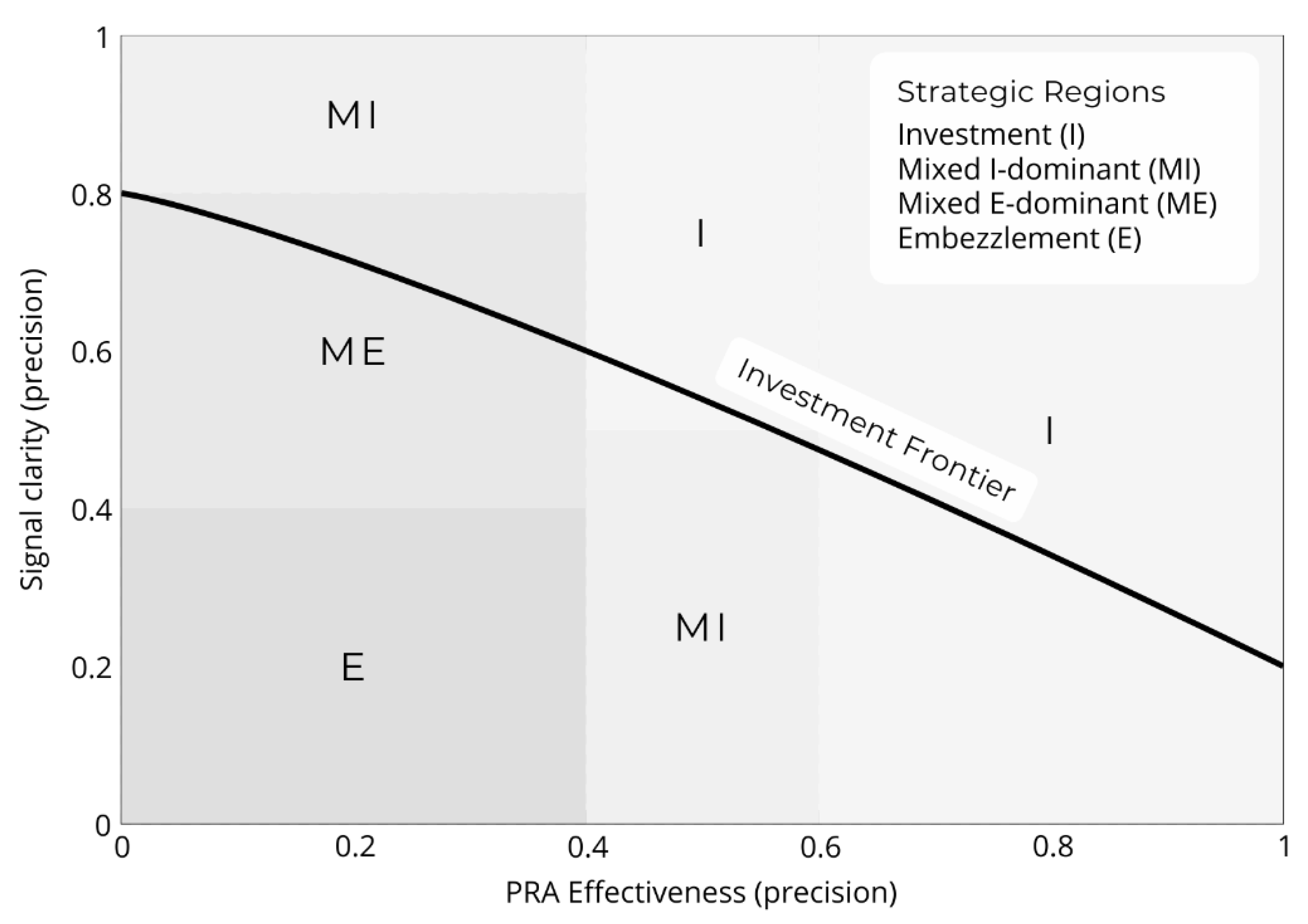

- : elite action — pure investment in public goods, pure embezzlement of public funds, mixed strategy-investment dominant (the elite invests primarily in public goods but engages in some level of corruption with probability .) and mixed strategy-embezzlement dominant (the elite mainly embezzles funds but invests a fraction in public goods with probability )

- : A noisy signal about the elite’s chosen action , with likelihood . This signal helps the population to imperfectly learn about the elite’s behavior in office.

- : The discount factor, indicating how much elites and the population value future payoffs compared with current payoffs. A higher means that future outcomes (such as re-election) are more relevant.

- : payoffs to the elite and population, respectively at stage

2.2.2. Stages of the Game

2.3. Introduction of a Political Rating Agency (PRA)

- ➢

- Providing Accessible and Credible Information: PRAs would meticulously collect and analyze comprehensive data on political candidates, encompassing their backgrounds, voting records, policy positions, campaign promises, and any history of corruption. This in-depth research would offer voters readily accessible, fact-based insights that are otherwise difficult and time-consuming to gather independently, enabling more informed decisions based on verifiable data.

- ➢

- Reducing Adverse Selection: By publicly rating candidates before elections, PRAs would help voters distinguish between qualified individuals and those who may be problematic. This transparency would minimize the risk of electing unsuitable candidates – those who might be corrupt, incompetent, or misaligned with the electorate's values. This pre-election evaluation acts as a crucial safeguard against "bad actors" and promotes accountability.

- ➢

- Mitigating Moral Hazard: Through ongoing monitoring and rating of incumbents during their terms, PRAs would serve as continuous checks. This incentivizes politicians to remain diligent, act transparently, and deliver public goods, as poor ratings could jeopardize their re-election prospects.

- ➢

- Enhancing Voter Decision-Making: PRAs empower voters by simplifying complex political information. Easy-to-understand scorecards or grades would distill governance data into accessible formats, enabling all voters, regardless of their political expertise, to make more informed choices at the ballot box.

- ➢

- Supporting Institutional Trust: By operating as non-partisan, expert bodies, PRAs would foster greater institutional trust. In an era of polarized media and partisan division, they would offer a credible, objective source of information, thereby strengthening the foundations of democratic governance.

2.4. Augmented Model

3. Results

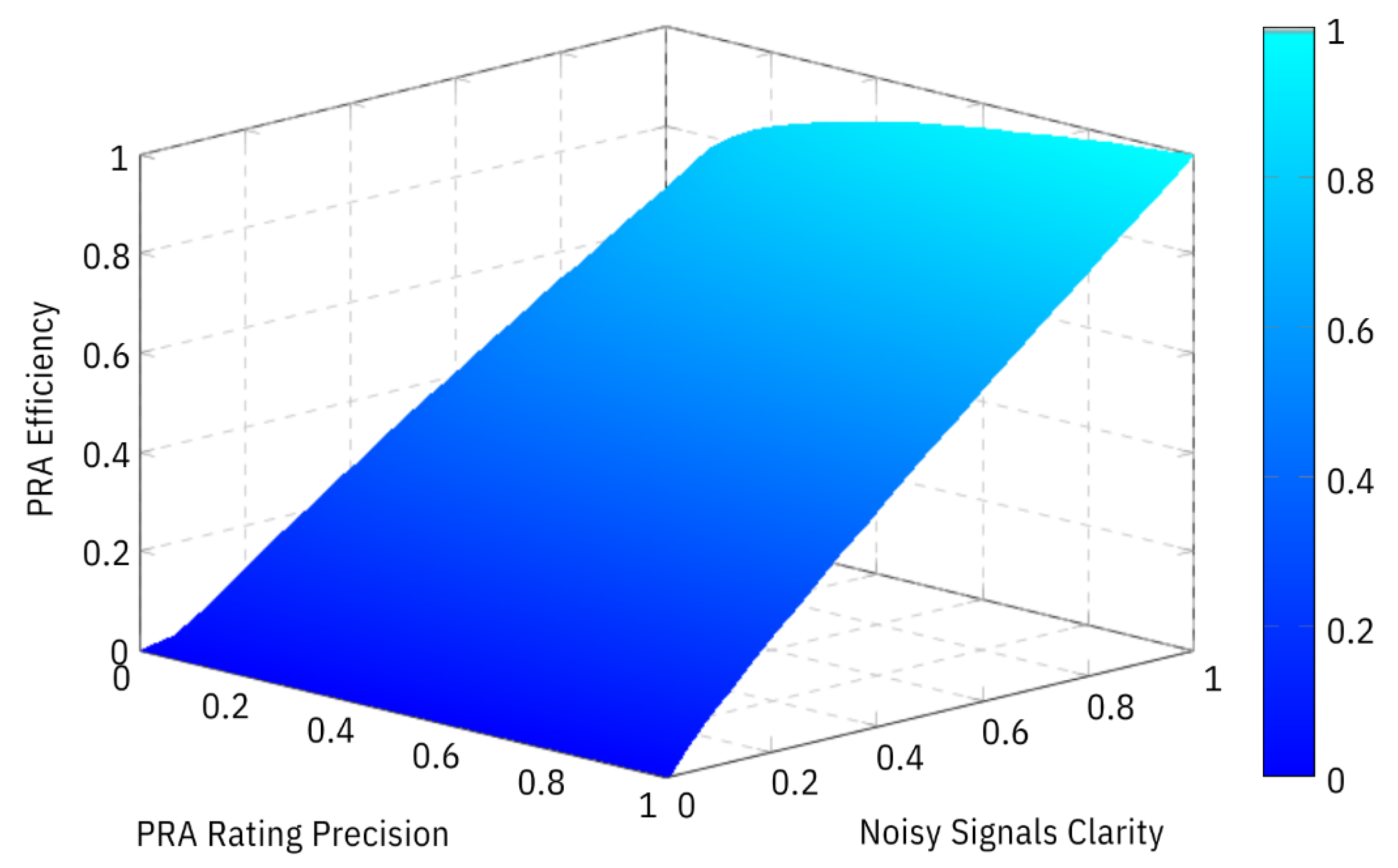

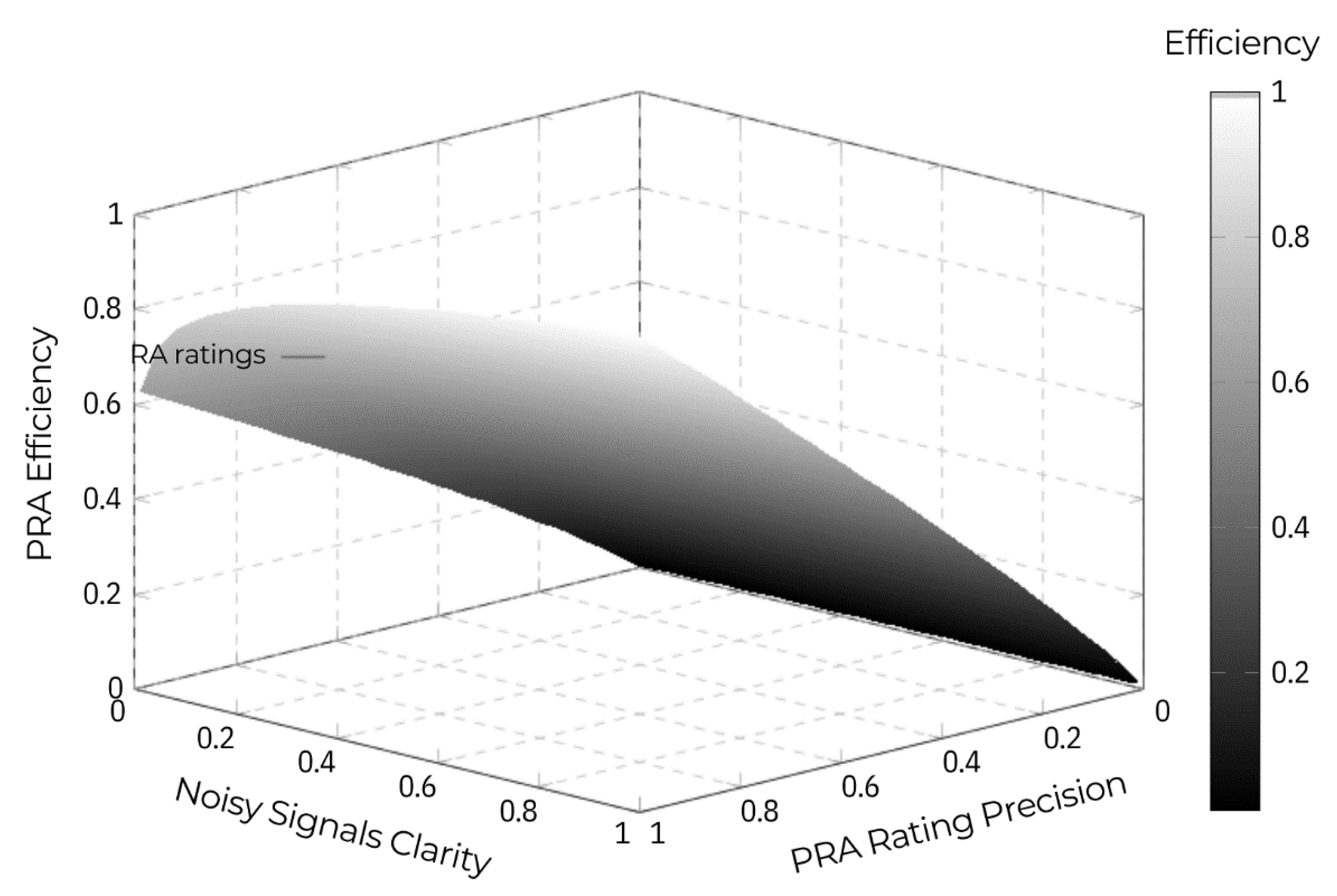

3.1. Impact on Noisy Signals and Beliefs

- Sharper Bayesian Updates: Beliefs ( become more responsive to actual elite behavior and type. The population can more accurately distinguish from .

- Mitigation of Adverse selection: With clearer information before elections (from ), the population is better prepared to select high-type elites.

- Mitigation of Moral Hazard: Knowing that their actions will be assessed by the PRA (via ) and that these evaluations are relatively transparent, elites have less motivation to engage in hidden opportunistic actions.

3.2. Reputational Costs and Shifts in Elite Strategies

- Lowered public esteem.

- Reduced chances of re-election or future political success.

- Increased scrutiny and criticism from media and civil society.

- Before election: Make more credible promises and possibly reduce electoral fraud to avoid negative and ratings.

- Action phase: Shift from embezzlement-focused () strategies toward investment-focused () strategies to prevent poor ratings and improve the chances of a good cumulative .

3.3. Impact on Equilibria

4. Discussion

4.1. Institutional Credibility and Feasibility

4.2. Effect of Population Reactivity

- Unreactive population (): The population largely ignores or distrusts the PRA’s rating , relying mostly on nosy private signals . In this case, the PRA’s impact is minimal, and issues of adverse selection and moral hazard continue to a great extent.

- Reactive population ():The population trusts and heavily relies on the PRA’s ratings. Private noisy signals are mostly disregarded. In this scenario, the influence of the political rating agency is at its peak.

5. Conclusions

References

- Achen, C.H.; Bartels, L.M. Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government; Princeton University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alesina, A.; Rosenthal, H. Partisan Politics, Divided Government, and the Economy; Cambridge University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Allcott, H.; Gentzkow, M. Social media and fake news in the 2016 election. Journal of Economic Perspectives 2017, 31(2), 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, D.M.; Jost, J.T. Political ideology as motivated social cognition: Behavioral and neuroscientific evidence; Motivation and Emotion, 2012; Volume 36, pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anduiza, E.; Gallego, A.; Muñoz, J. Turning a blind eye: Experimental evidence of partisan bias in attitudes toward corruption. Comparative Political Studies 2013, 46(12), 1664–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arceneaux, K.; Johnson, M. Changing Minds or Changing Channels? Partisan News in an Age of Choice; University of Chicago Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, S.; Bueno de Mesquita, E.; Freidenberg, A. Learning about voter rationality. American Journal of Political Science 2018, 62(1), 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Kumar, S.; Pande, R. Do Informed voters make better choices? Experimental evidence from Urban India; Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Carnegie Mellon University; Harvard University, 2011; (Unpublished manuscript). [Google Scholar]

- Bartoloni, D.; Sacchi, A.; Scalera, D.; Zazzar, A. Voters’ distance, information bias and politicians’ salary; Italian Economic Journal, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T. Principled Agents? The Political Economy of Good Government; Oxford University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Besley, T.; Burgess, R. The political economy of government responsiveness: Theory and evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics 2002, 117(4), 1415–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T.; Prat, A. Handcuffs for the grabbing hand? Media capture and government accountability. American Economic Review 2006, 96(3), 720–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, J. Polluting the polls: When citizens should not vote. Australasian Journal of Philosophy 2009, 87(4), 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, J. Against Democracy; Princeton University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Breitenstein, S.; Hernández, E. Too crooked to be good? Trade-offs in the electoral punishment of malfeasance and corruption. European Political Science Review 2024, 17(1), 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, J.G. Elite influence on public opinion in an informed electorate. American Political Science Review 2011, 105(3), 496–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.; Converse, P.E.; Miller, W.E.; Stokes, D.E. The American Voter; University of Chicago Press, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, B. Rational irrationality and the microfoundations of political failure. Public Choice 2001, 107(3), 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.; et al. Does corruption information inspire the fight or quash the hope? A field experiment in Mexico on voter turnout, choice, and party identification. The Journal of Politics 2015, 77(1), 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, R.G.; Lodge, M.; Vidigal, R. The boundary conditions of motivated reasoning; Tolbert, R. K., Ed.; The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Persuasion, 2020; pp. 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- De Figueiredo, M.F.P.; Hidalgo, D.F.; Kasahara, F.Y. When do voters punish corrupt politicians? Experimental evidence from a field and survey experiment. British Journal of Political Science 2023, 53(2), 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djankov, S.; McLiesh, C.; Nenova, T.; Shleifer, A. Who owns the media? The Journal of Law and Economics 2003, 46(2), 341–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, A. An Economic Theory of Democracy; Harper Collins, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Dulay, D.C.; Lee, S. Sorry not sorry: Presentational strategies and the electoral punishment of corruption. Electoral Studies 2024, 92, 102683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T.; et al. Voter information campaigns and political accountability: Cumulative findings from a preregistered meta-analysis of coordinated trials. Science Advances 2019, 5(7), eaaw2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eck, B.; Paulis, E. Defending the status quo or seeking change? Electoral outcome, affective polarization, and support for referendums. British Journal of Political Science 2025, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejdemyr, S.; Kramon, E.; Robinson, A.L. Segregation, ethnic favoritism, and the strategic targeting of local public goods. Comparative Political Studies 2018, 51(9), 1111–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearon, J.D. Electoral accountability and the control of politicians: Selecting good types versus sanctioning poor performance. In Democracy, Accountability, and Representation; Przeworski, A., Stokes, S.C., Manin, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 1999; pp. 55–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ferejohn, J. Incumbent Performance and Electoral Control. Public Choice 1986, 50(1-3), 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, C.; Finan, F. Exposing corrupt politicians: The effects of Brazil's publicly released audits on electoral outcomes. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2008, 123(2), 703–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, C.; Finan, F. Electoral accountability and corruption: Evidence from the audits of local governments. American Economic Review 2011, 101(4), 1274–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E.; Chang, H.; Chen, E.; Muric, G.; Patel, J. Characterizing social media manipulation in the 2020 US presidential election. First Monday 2020, 25(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentzkow, M.; Shapiro, J.M.; Stone, D.F. Media bias in the marketplace: Theory. In Handbook of Media Economics; Rose, N.L., Ed.; North-Holland, 2016; vol. 1, pp. 623–645. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Ponzetto, G.A.M. Fundamental errors in the voting booth. NBER Working Paper Series 2017, No. 23683. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G.; Michelitch, K.; Prato, C. The effect of sustained transparency on electoral accountability. American Journal of Political Science 2023, 67(1), 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L. Deciding What’s True: The Rise of Political Fact-Checking in American Journalism; Columbia University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, P. Sequential rationality and ordinal preferences. Unpublished manuscript. SSRN. 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3621347.

- Guriev, S.; Treisman, D. A theory of international autocracy. Journal of Public Economics 2020, 190, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, M. Are knowledgeable voters better voters? Politics, Philosophy, Economics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, A.; Malhotra, N. Retrospective voting reconsidered. Annual Review of Political Science 2013, 16, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, M.J. Putting polarization in perspective. British Journal of Political Science 2009, 39(2), 413–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, S.J. Learning together slowly: Bayesian learning about political facts. Journal of Politics 2017, 79(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S.; Lelkes, Y.; Levendusky, M.; Malhotra, N.; Westwood, S.J. The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science 2019, 22, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, R.; Smith, J.; Johnson, K. Cumulative learning in democratic systems. Journal of Theoretical Politics 2018, 30(2), 145(167). [Google Scholar]

- Kalmoe, N.P. Uses and abuses of ideology in political psychology. Political Psychology 2020, 41(4), 771–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klas̆na, M. Corruption and the incumbency disadvantage: Theory and evidence. Journal of Politics 2015, 77, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.; Mendez, F. Corruption and elections: An empirical study for a cross-section of countries. Economics & Politics 2009, 21(2), 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Jha, C. Condoning corruption: Who votes for corrupt political parties? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 2023, 215, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I-C.; Chen, E.E.; Yen, N-S.; Tsai, C-H.; Cheng, H-P. Are we rational or not? The exploration of voters’ choices during 2016 presidential and legislative elections in Taiwan. Frontiers in Psychology 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitsky, S.; Ziblatt, D. How Democracies Die; Crown, 2018; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, S.; Quaranta, M. Political support among winners and losers: Within- and between-country effects of structure, process and performance in Europe. European Journal of Political Research 2019, 58(1), 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

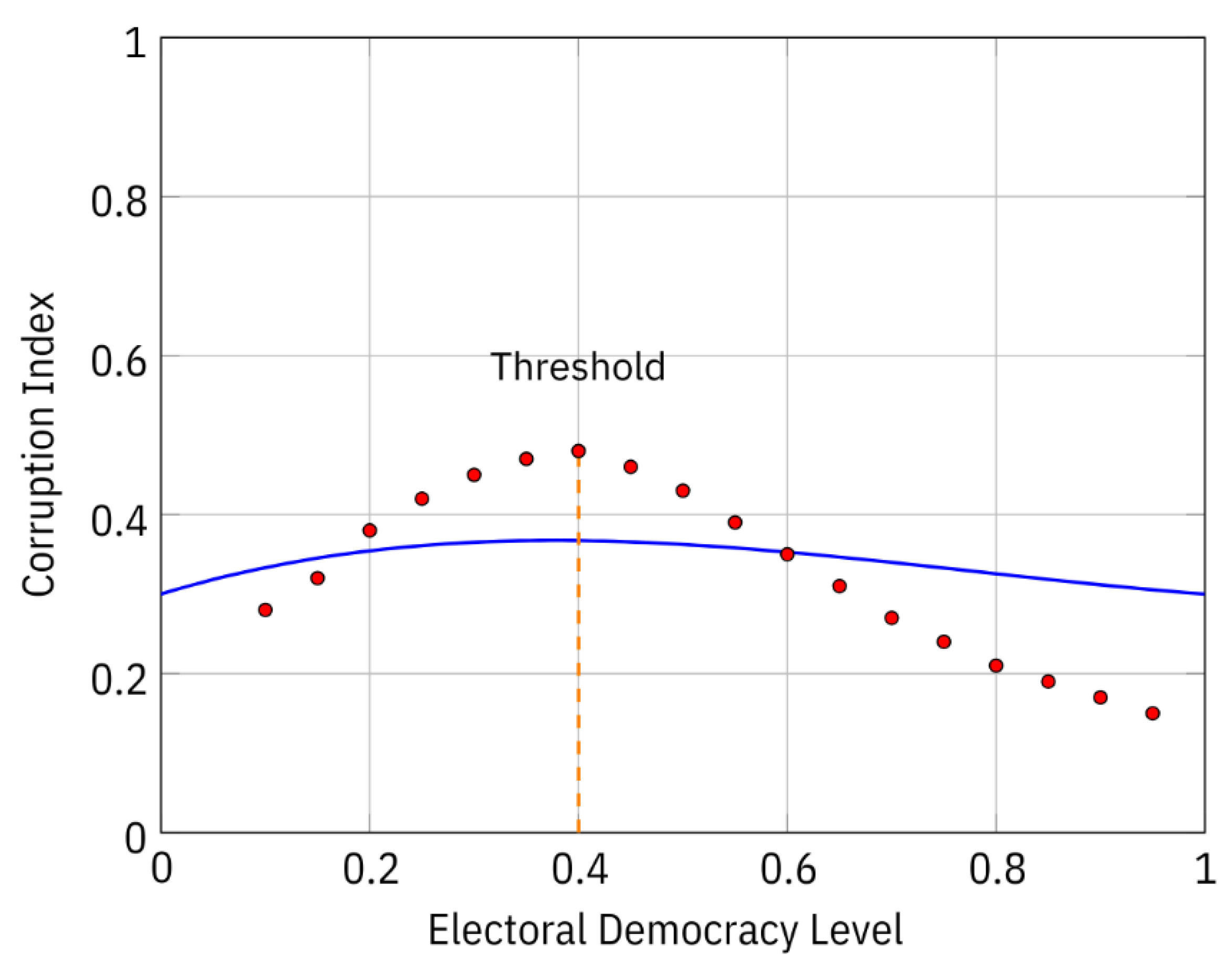

- McMann, K.M.; Seim, B.; Teorell, J.; Lindberg, S. Democracy and corruption: A global time-series analysis with V-Dem data. In Working Paper Series 2017; Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, 2017; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Nai, A. Voter information processing and political decision making. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition; Wright, J. D., Ed.; Elsevier, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeau, R.; Daoust, J-F.; Dassonneville, R. Winning, losing and the quality of democracy. Political Studies 2023, 71(2), 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M. The motivated electorate: Voter uncertainty, motivated reasoning, and ideological congruence to parties. Electoral Studies 2021, 72, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C.; Wallis, J.J.; Weingast, B.R. Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History; Cambridge University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J. The effect of fact-checking on elites: A field experiment on U.S. state legislators. American Journal of Political Science 2015, 59(3), 628–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, R. Can informed voters enforce better governance? Experiments in low-income democracies. Annual Review of Economics 2011, 3(1), 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.; McClendon, G. Cynicism and voter support for openly corrupt candidates: Evidence from Kenya. In Working Paper; Dartmouth College & New York University, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson, S. The very idea of rational irrationality; Politics, Philosophy & Economics, 2023; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienks, H. Corruption, scandals and incompetence: Do voters care? European Journal of Political Economy 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeberg, H.B.; Slothuus, R.; Stubager, R. Do voters learn? Evidence that voters respond accurately to changes in political parties’ policy positions. West European Politics 2016, 40(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, T.J. The New Masters of Capital: American Bond Rating Agencies and the Politics of Creditworthiness; Cornell University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Somin, I. Democracy and Political Ignorance: Why Smaller Government is Smarter; Stanford University Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stoetzer, L.F.; Leeman, L.; Traunmueller, R. Learning from polls during electoral campaigns; Political Behavior, 2024; Volume 46, pp. 543–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappin, B.M.; Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. Bayesian or biased? Analytic thinking and political belief updating. Cognition 2020, 204, 104375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Remoortere, A.; Vliegenthart, R. Affective polarization and political (dis)trust: Investigation of their interconnection and the moderating role of (social) media use. European Journal of Communication, 2025.

- Vaeth, M. Rational voter learning, issue alignment and polarization; Working Paper, Paris School of Economics, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wantchekon, L. Clientelism and voting behavior: Evidence from a field experiment in Benin. World Politics 2003, 55(3), 399–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitz-Shapiro, R.; Winters, M.S. Can citizens discern? Information credibility, political sophistication, and the punishment of corruption in Brazil. The Journal of Politics 2017, 79(1), 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.K.; Grose, C.R. Campaign finance transparency affects legislators’ election outcomes and behavior. American Journal of Political Science 2022, 66(2), 516–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).