Submitted:

15 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Review Purpose

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Question

2.1.1. Problem Identification

2.1.2. Literature Search

2.2. The Search Terms

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

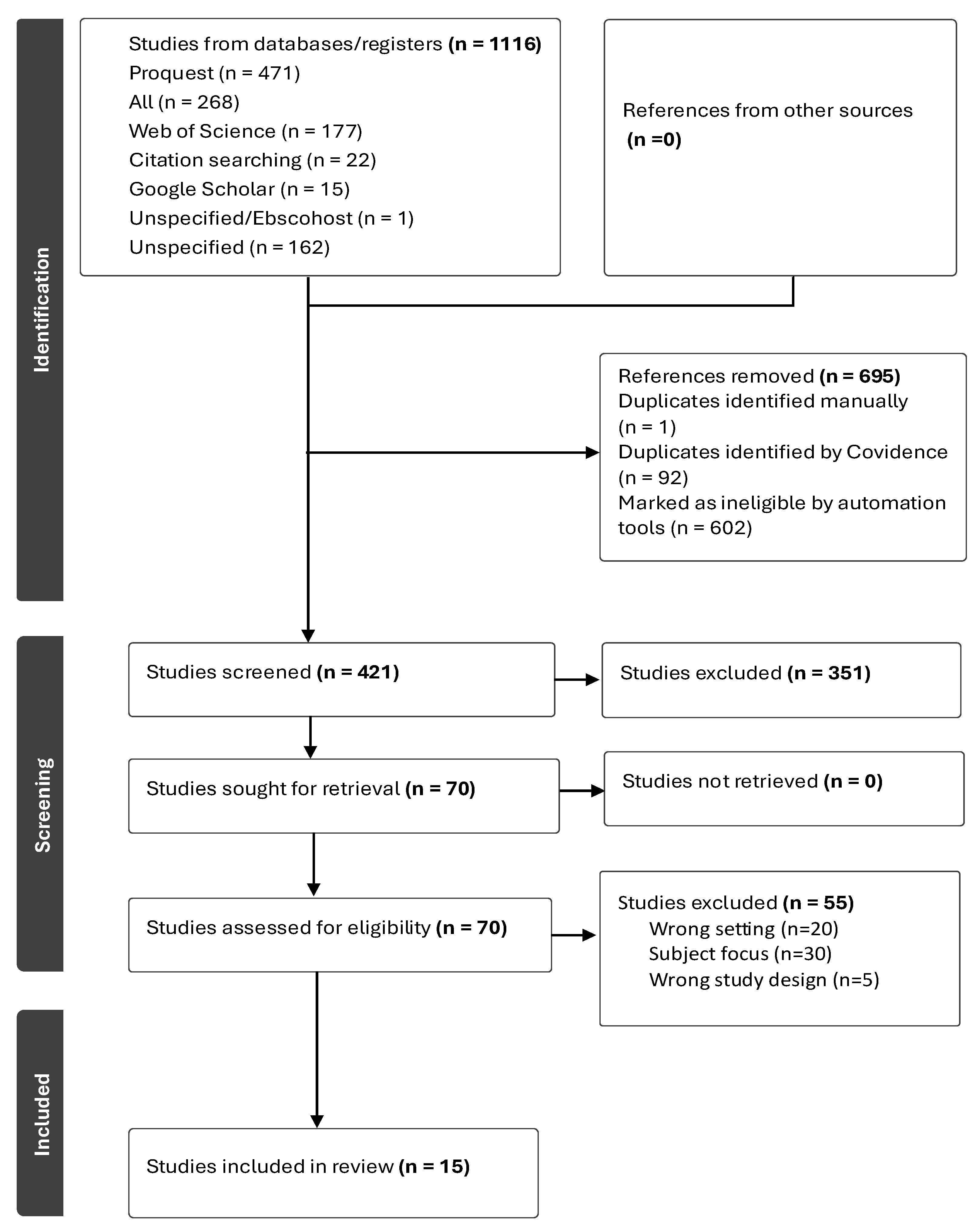

2.4. Selection of Data

2.4.1. Quality Assessment

2.4.2. Methodological Rigor

2.5. Documenting the Data

2.6. Organizing, Summarizing, and Presenting the Findings

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Studies Included

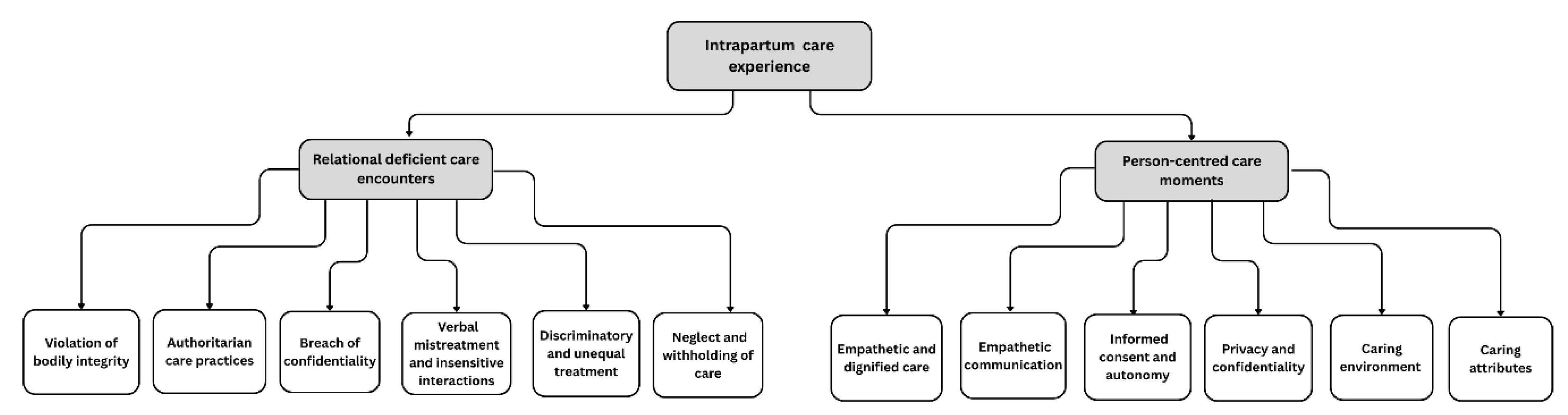

3.2. Scope of Narratives and Conceptual Framing

3.3. Person-Centred Care Moments

3.3.1. Empathetic and Dignified Care

“They respected my body and allowed me to labour in my own way.” [41]

3.3.2. Empathetic Communication

“The midwife held my hand and told me I was strong. That made me feel I could do it.” [35]

3.3.3. Informed Consent and Autonomy

“They asked me before they did anything. I felt like I had control over my birth.” [39]

3.3.4. Privacy and Confidentiality

“They covered me properly and ensured others could not see me.” [35]

3.3.5. Caring Environment

“They allowed my sister to stay with me I felt strong knowing she was there.” [39]

3.3.6. Caring Attributes

“The midwife held my hand and said, ‘You can do it’; that gave me courage.” [40]

3.4. Relational Deficient Care Encounters

3.4.1. Violation of Bodily Integrity

“… That is very bad because during delivery you push with a lot of pain and you are suffering while been pinched or slapped, it’s not acceptable…” [34]

3.4.2. Authoritarian Care Practices

“I told the midwifenotto allow [students to enter and observe care], but they were already in the room on practical learning, and the midwife didn’t want to send them out once they were in. In the future, I don’t want that.” [31]

3.4.3. Breach of Confidentiality

“…assessments were done in non-private settings with many students around to observe.” [32]

3.3.4. Verbal Mistreatment and Insensitive Interactions

“They say, don’t cry! There is no mum here, eh? Don’t cry. Did your mum make your baby, eh? Or was it your boyfriend?” [43]

3.4.5. Discriminatory and Unequal Treatment

“...theytreatyou depending on your background…If you come wearing nice clothes and accompanied by urban companions, they will give you a priority. For mothers in torn clothes, then things are different.” [30]

3.5. Neglect and Withholding of Care

“After the baby came, she (the nurse) was about to stitch me and I was afraid because she did not give me anything for pain, so I refused, and she left me in bed with blood all over me for about two to three hours.” [42]

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Recommendations

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blomberg K, Griffiths P, Wenstrom Y, May C, Bridges J. Interventions for compassionate nursing care: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;62:137–155. Epub. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Definition of skilled health personnel providing care during childbirth: The 2018 joint statement by WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, ICM, ICN, FIGO and IPA. 2018. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/definition-of-skilled-health-personnel-providing-care-during-childbirth.

- Vedeler C, Nilsen AB, Downe S, Eri TS. The “doing” of compassionate care in the context of childbirth from a women’s perspective. Qual Health Res. 2025;35(10-11):1177-90. [CrossRef]

- Strauss C, Taylor BE, Gu J, Kuyken W. Baer R, Jones F, Cavanagh J. What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clin Psychol Rev. [CrossRef]

- Menage D, Bailey E, Lees S, Coad J. Women's lived experience of compassionate midwifery: Human and professional. Mid. 2020;1(85):102662. [CrossRef]

- Cummings J, Bennett V. Compassion in Practice: Nursing, Midwifery and Care Staff - our Vision and Strategy. NHS Commissioning Board. http://www.england.nhs.uk/ wp-content/uploads/2012/12/compassion-in-practice (accessed 1 April 2024).

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, et al. The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed Method Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6):e1001847. [CrossRef]

- Vusio F, Odentz K, Plunkett C. Experience of compassionate care in mental health and community-based services for children and young people: facilitators of, and barriers to compassionate care–a systematic review. European Child Adolesc Psych. 2025; 4:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Lim SWC, Foo SA, Chan, HG, Mathur M. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2024;13(6):1376-1382. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2025. HIV and AIDS. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids Date accessed 16 August 2025.

- Asefa A, McPake B, Langer A, Bohren MA, Morgan A. Imagining maternity care as a complex adaptive system: understanding health system constraints to the promotion of respectful maternity care. Sex Reprod Health Matters. 2020;28(1):e1854153. [CrossRef]

- Moyer CA, McNally B, Aborigo RA, Williams JEO, Afulani PA. Providing respectful maternity care in northern Ghana: A mixed-methods study with maternity care providers. Midwifery. 2021;94:102904. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/134588/1/WHO_RHR14.23_eng.pdf (accessed 28 Mar 2024).

- White Ribbon Alliance (WRA). Respectful Maternity Care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women. https://content.sph.harvard.edu/wwwhsph/sites/2413/2014/05/Final_RMC_Charter.pdf (accessed 17 Apr 2024).

- National Department of Health. National Integrated Maternal and Perinatal Care Guidelines for South Africa (5th ed.). Government of South Africa. http//www.Department of Health Knowledge Hub: Integrated Maternal and Perinatal Care Guideline_23_10_2024_0.pdf (accessed 20 Aug 2025).

- Thirukumar, M. Short Review on Respectful Maternal Care (RMC). Batticaloa Medic J. 2024;18(2). [CrossRef]

- Mayra K, Catling C, Musa H, Hunter B, Baird K. Compassion for midwives: The missing element in workplace culture for midwives globally. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3(7):e0002034. [CrossRef]

- West M, Bailey S, Williams E. The courage of compassion. Supporting Nurses and Midwives to Deliver High-Quality Care. London: The King’s Fund, London. 2020 Sep.

- Downe S, Finlayson K, Oladapo OT, Bonet M, Gülmezoglu AM. What matters to women during childbirth: A systematic qualitative review. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(4):e0194906. [CrossRef]

- Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method. 2005;8(1):19-32. [CrossRef]

- Levac D, Colquhoun H, & O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Imp Sci, 201;5(1):69. [CrossRef]

- Wildridge V, Bell L. 2002. How CLIP became ECLIPSE: a mnemonic to assist in searching for health policy/management information. Health Info Libra J. 2002;19(2). [CrossRef]

- Torraco, RJ. Writing Integrative Reviews of the Literature: Methods and Purposes. Int J Adult Vocat Edu Tech. 2016;7(3):62-70. [CrossRef]

- Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Johanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute. 2015 edition Suppl. Accessed September 26, 2024. https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ Reviewers Manuals/ Scoping-.pdf.

- Renjith V, Yesodharan R, Noronha JA, Ladd E, George A. Qualitative methods in health care research. Human Reprod Sci. 2021;14(1), 80–86. [CrossRef]

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Edu Info. 2018;34(4), 285–291.

- Covidence. 2025. Covidence Academy. Accessed 21 January https://academy.covidence.org/.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj. 2021;29;372.

- Asrese, K. Quality of intrapartum care at health centers in Jabi Tehinan district, North West Ethiopia: clients’ perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Burrowes S, Holcombe SJ, Jara D, Carter D. Smith K. Midwives' and Patients' Perspectives on Disrespect and Abuse During Labor and Delivery Care in Ethiopia: A Qualitative Study. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2017;17:263. [CrossRef]

- Jiru HD, Sendo EG. Promoting compassionate and respectful maternity care during facility-based delivery in Ethiopia: perspectives of clients and midwives. BMJ Open 2021;11:e051220. [CrossRef]

- Afulani PA, Kirumbi L, Lyndon A. What makes or mars the facility-based childbirth experience: thematic analysis of women’s childbirth experiences in western Kenya. Reproductive health. 2017;29;14(1):180.

- Oluoch-Aridi J, Afulani PA, Guzman DB, Makanga C, Miller-Graff L. Exploring women’s childbirth experiences and perceptions of delivery care in peri-urban settings in Nairobi, Kenya. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):83.

- Kumbani L, Bjune G, Chirwa E, Malata A, Odland JØ. Why some women fail to give birth at health facilities: a qualitative study of women’s perceptions of perinatal care from rural southern Malawi. Reprod Health. 2013;10:9. [CrossRef]

- Metta E, Unkels R, Mselle LT, Hanson C, Alvesson HM, Al-Beity FMA. Exploring women’s experiences of care during hospital childbirth in rural Tanzania: a qualitative study. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2024;24(1):290. [CrossRef]

- Shimpuku Y, Patil CL, Norr KF, Hill PD. Women's perceptions of childbirth experience at a hospital in rural Tanzania. Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(6);461-481.

- Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Willcox M, Nabudere H. Ugandan health workers’ and mothers’ views and experiences of the quality of maternity care and the use of informal solutions: A qualitative study. PLoS O 2019;14(3):e0213511. [CrossRef]

- Namujju J, Muhindo R, Mselle L T, Waiswa P, Nankumbi J, Muwanguzi P. Childbirth experiences and their derived meaning: A qualitative study among postnatal mothers in Mbale regional referral hospital, Uganda. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1),183. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick RJ, Cooper D, Harries J. Narratives of distress about birth in South African public maternity settings: A qualitative study. Midwifery. 2014;30:862-868. [CrossRef]

- Hastings-Tolsma M, Nolte GW. Temane A. Birth stories from South Africa: Voices unheard. Women Birth. 2018;31(1):e42-e50. [CrossRef]

- Malatji R, Madiba S. Disrespect and Abuse Experienced by Women during Childbirth in Midwife-Led Obstetric Units in Tshwane District, South Africa: A Qualitative Study. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2020;17:3667. [CrossRef]

- Wibbelink M, James S, Thomson AM. A qualitative study of women and midwives' reflections on midwifery practice in public maternity units in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Afri J Mid Women Health. 2022;16(2):1-4. [CrossRef]

- Zitha E, Mokgatle MM. Women’s views of and responses to maternity services rendered during labor and childbirth in maternity units in a semi-rural district in South Africa. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2020;17(14):5035. [CrossRef]

- Stanton ME, Gogoi A. Dignity and respect in maternity care. BMJ Global Health 2022;5:e009023. [CrossRef]

- Freedman LP, Kruk ME. Disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth: challenging the global quality and accountability agendas. The Lancet. 2014;384(9948):e42-4. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. World Health Organization. 2016.

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Tunçalp Ö, Fawole B, Titiloye MA, Olutayo AO, Ogunlade M, Oyeniran AA, Osunsan OR, Metiboba L, Idris HA. Mistreatment of women during childbirth in Abuja, Nigeria: a qualitative study on perceptions and experiences of women and healthcare providers. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):9. [CrossRef]

- Vedam S, Stoll K, Taiwo TK, Rubashkin N, Cheyney M, Strauss N, McLemore M, Cadena M, Nethery E, Rushton E, Schummers L. The Giving Voice to Mothers study: inequity and mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):77. [CrossRef]

- Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth. Boston: USAID-traction project, Harvard school of public health. 2010.

- Hawkes S, Allotey P, Elhadj AS, Clark J, Horton R. The Lancet Commission on gender and global health. The Lancet. 2020 Aug 22;396(10250):521-2.

- Afulani PA, Kelly AM, Buback L, Asunka J, Kirumbi L, Lyndon A. Providers' perceptions of disrespect and abuse during childbirth: a mixed-methods study in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35:577-586. [CrossRef]

- WHO recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Chikezie NC, Shomuyiwa DO, Okoli EA, Onah IM, Adekoya OO, Owhor GA, Abdulwahab AA. Addressing the issue of a de-pleting health workforce in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet. 2023;401(10389):1649-1650. [CrossRef]

- Okeny PK, Pittalis C, Monaghan CF, Brugha R, Gajewski J. Dimensions of patient-centred care from the perspective of patients and healthcare workers in hospital settings in sub-Saharan Africa: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Plos one. 2024;19(4):e0299627. [CrossRef]

| Expectation | The study aims to provide insight into the experiences of women who gave birth in health facilities. |

|---|---|

| Client group | The focus is specifically on postpartum women who gave birth normally |

| Location | The studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa |

| Impact | Compassion during intrapartum care |

| Professionals | Midwives/nurses and or doctors are the birth attendants. |

| Service | Refers to intrapartum care rendered to women within health facilities |

| Description | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Women who gave birth in health facilities across Sub-Saharan Africa | Ensures the review reflects women’s first-hand experiences of care within facility-based childbirth, where health system interactions are most visible and policy interventions are focused. |

| Experiences and perceptions of compassionate, respectful, empathetic, or dignified maternity care during childbirth | Aligns with the review’s aim to explore positive dimensions of care and identify elements that foster respectful, person-centred maternity practices. |

| Qualitative and mixed-methods studies with qualitative components | Captures the richness and depth of women’s narratives, emotional expressions, and interpretations of care that quantitative data alone may overlook. |

| Health facilities such as hospitals, maternity wards, or clinics providing childbirth services | Focuses on institutional contexts where respectful care policies and professional standards are most applicable and measurable. |

| Studies involving women who gave birth within six months prior to data collection | Minimizes recall bias and ensures accounts reflect recent practices, service quality, and prevailing care standards. |

| English language | Facilitates consistent data extraction, synthesis, and interpretation within the linguistic capabilities of the research team. |

| Peer-reviewed, full-text journal articles | Guarantees methodological rigour, transparency, and accessibility of complete findings for quality appraisal. |

| Published between 2012–2024 | Corresponds with the post-2011 period following the introduction of the Respectful Maternity Care Charter, capturing the growing policy and research focus on compassionate and respectful maternity care. |

| Studies conducted in Sub-Saharan African countries | Provides a contextual understanding of women’s experiences within a region marked by shared maternal health challenges, sociocultural contexts, and health system reforms. |

| Theme | Theme |

|---|---|

| Person-centred care moments | Relational deficient care encounters |

| Sub-themes | Sub-themes |

| Empathetic and dignified care | Physical mistreatment |

| Empathetic communication | Unconsented care |

| Informed consent and autonomy | Verbal mistreatment and insensitive interactions |

| Privacy and confidentiality | Discriminatory and inequitable care |

| Caring environment | Breach of confidentiality |

| Caring attributes | Neglect and withholding of care |

| Authors | Aim / objectives & birth setting | Main results related to the review purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Asrese [30] | To assess the quality of intrapartum care experienced by mothers at health centres and homes in the Jabi Tehinan district, Northwest Ethiopia. | Positive: emotional support, clean environment, privacy, appreciated companions. Negative: unfriendly staff, poor communication, uncaring, verbal abuse, discriminatory care. |

| Burrowes et al. [31] | To examine women’s experiences of care from midwives during labour and delivery including disrespect/abuse in public health centres and homes in Ethiopia. | Positive: facility recommended by friends, oral fluids allowed, appropriate positions. Negative: abuse, unconsented care, lack of privacy, neglect, denial of services/companions, unnecessary procedures, mobility restriction. Resource: inadequate beds. |

| Jiru & Sendo [32] | To explore clients’ and midwives’ perceptions of compassionate and respectful care during facility-based delivery in Bishoftu District (Oromia, Ethiopia). | Positive: caring treatment (“like a friend”). Negative: discriminatory care, verbal abuse, underqualified staff. |

| Afulani et al. [33] | To examine women’s facility–based childbirth experiences in a rural county in Kenya, to identify aspects of care that contribute to a positive or negative birth experience. |

Positive: Warm reception, caring treatment, birth companions allowed, clean linen Negative: abandonment, discriminatory care, verbal abuse. |

| Oluoch-Aridi et al. [34] | To explore women's experiences during childbirth at six health facilities across Embakasi sub-counties (public, private, faith-based) Nairobi, Kenya. | Positive: warm reception, dignified communication, supportive care. Negative: lack of information, discriminatory and non-dignified care, verbal abuse. Companions: often not allowed, women wanted support persons. |

| Kumbani et al. [35] | To describe women’s perceptions of perinatal care among women who delivered at a district hospital in Malawi. | Positive: good reception/respect, breastfeeding advice, positive attitudes, confidentiality. Negative: verbal abuse, neglect, abandonment. |

| Metta et al. [36] | To explore women’s childbirth experiences to inform a co-designed quality improvement intervention in four rural hospitals (including one faith-based) in southern Tanzania. | Positive: good communication, informed procedures, dignified care, midwife support. Negative: lack of information/compassion, verbal abuse. Companions: mixed views. |

| Shimpuku et al. [37] | To explore women's perceptions of childbirth experience at a hospital in rural Tanzania. | Positive: caring/friendly midwives, supportive care, good service, skilled HCPs. Negative: verbal abuse, lack of support/information, abandonment. Companions: relatives appreciated. |

| Munabi-Babigumira et al. [38] | To explore the nature of interactions between mothers and health workers in Mpigi and Rukungiri districts (health facilities and home), Uganda. | Positive: Dignified interactions, staff explained procedures, provider dedication despite constraints. Negative: lack of information, discriminatory care, verbal abuse. Resource: inadequate supplies. Companions: denied due to space. |

| Namujju et al. [39] | To explore childbirth experiences and their meaning among postnatal mothers in a public hospital, Uganda. | Positive: supportive care (comfort, touch, reassurance), empowerment via vaginal birth, cultural meaning in enduring pain. Negative: non-caring, rough handling, limited support. Companions: relatives appreciated and preferred. |

| Chadwick et al. [40] | To explore factors associated with negative maternity settings from women's birth narratives, City of Cape Town, South Africa. | Positive: kindness, reassurance, gentle touch Negative: abuse, neglect, abandonment reported by many. |

| Hastings-Tolsma et al. [41] | To describe experiences of women receiving care during childbirth in private, public, and maternity hospitals, and homes in South Africa. | Positive: shared decision-making in midwife-led care, respect for beliefs/preferences. Negative: neglect, abandonment, lack of autonomy, loneliness without companions. Companions: mixed experiences. |

| Malatji & Madiba [42] | To explore women’s experiences of care during childbirth and examine occurrence of disrespect & abuse (D&A) during childbirth in MOUs, South Africa. | Positive: gentle tone, reassurance, timely clinical care, respect for privacy. Negative: abuse, lack of support, discrimination, poor standards. Companions: mixed as some had, while others did not. |

| Wibbelink et al. [43] | To describe factors affecting clinical practice in public maternity units from women’s perspectives in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. | Positive: caring/friendly midwives, competence in complications, empathetic engagement. Negative: verbal abuse, neglect. |

| Zitha & Mokgatle [44] | To assess views of women about care received during labour and childbirth and interactions with midwives in MOUs and the district hospital in a semi-rural Tshwane district, South Africa. | Positive: empathetic/polite midwives, reassurance, privacy/modesty preserved. Negative: verbal abuse, neglect, lack of informed choice/advice. Companions: mostly denied. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).