1. Introduction

Women in the perinatal period are known to have a higher risk of experiencing mental health concerns [

1] and are vulnerable to environmental stressors [

2]. Research shows that one in five perinatal women experiences anxiety and one in 10 experiences depression [3-4]. Moreover, perinatal women have been found to be more vulnerable to psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic with research suggesting that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the risk of mental health issues for perinatal women globally [5-8]. This is understandable given that during the pandemic perinatal women were likely to fear infections of themselves and their infants and were under increased stress due to mandatory COVID-19 adjustments (i.e., working restrictions, hospital and appointment restrictions to mother only, reduced social supports; [

9]).

In Australia, national surveys conducted in 2020 showed a 51% increase in calls to perinatal mental health support lines [

10], with 43% of callers reporting their mental health had been impacted by COVID-19 [

11]. A meta-analysis [

9] looked at studies across Asia, Europe and North America on the prevalence of perinatal anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that perinatal anxiety almost tripled compared to levels reported in previous metanalyses (e.g., [

12]). Although these statistics raise concerns for the vulnerability of perinatal women and infants, most studies have targeted pregnant women and have been conducted outside Australia. Additionally, while anxiety and depression have received considerable attention, social anxiety emerged as a major problem in the community during the COVID-19 pandemic [13-14]. Therefore, this study sought to better understand how depression, general anxiety and social anxiety presented in Australian perinatal women as well as to explore the relationship with their COVID-19 experience.

1.1. Social Anxiety and Perinatal Women

A systematic review by Kindred and Bates [

14] found that the incidence of social anxiety among women had increased during the COVID-19 pandemic and even prior to the onset of COVID-19, social anxiety had been recognised as a “hidden epidemic” [

15]. Interestingly, women showed over double the rates of social anxiety prevalence compared to men in the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ 2022 review [

13]. Despite this, there is currently no specific research on social anxiety in perinatal women. A systematic review by McCarthy et al [

16] indicated, however, that perinatal women are likely to fear social scrutiny due to the pressure of meeting social norms to be a “good mother” and this is related to the presence of anxiety in social situations, that is, social anxiety. Moreover, COVID-19 restrictions and isolations have likely increased fear of meeting such expectations in perinatal women and provided them with fewer opportunities to build their social confidence as a mother. Taken together, this suggests there may be higher rates of social anxiety within the perinatal population that have gone unrecognised, and which are likely to have made these women more vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic. This underscores the need to better understand social anxiety in perinatal women and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.2. Emotion Regulation for Perinatal Women

Emotion regulation has been defined as the processes whereby individuals seek to influence their experience of emotions and their expression of emotion [

17]. Considering the increase in anxiety and depression, and possibly social anxiety, in the perinatal population during the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems important to understand which emotion regulation strategies could have influenced mental health outcomes during that time. Maladaptive behavioural emotion regulation (e.g., distraction and numbing behaviours like comfort eating) have been shown to be closely associated with anxiety and depression symptoms among perinatal women [

18]. Yet, there is currently no data on the relationships between specific inner emotion regulation strategies and perinatal mental health. However, research on the general population shows that, broad emotion regulation strategies such as self-compassion, are good predictors of mental health outcomes [19-21].

Neff’s framework of self-compassion as a broad form of emotional regulation is clearly associated with mental health outcomes [

22] and has been investigated in perinatal research [23-25]. Neff [

26] defined self-compassion as a person’s ability to be sensitive to their own experience of suffering. This inward concern for the self-manifests in three general ways: self-kindness (vs self-judgement), awareness of common humanity in painful experiences (vs feeling isolated in suffering), and mindfulness (vs overidentification with difficult experiences). Felder et al. [

23] found that self-compassion scores explained 10-24% of the variation in perinatal anxiety and depression, with high self-judgment, isolation, low self-kindness, and common humanity associated with higher anxiety and depression. COVID-19 related studies also show that higher levels of self-compassion predict less impairment in mother infant bonding, reduced perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms and lower birth related fear [

24,

27].

A study by Carona et al. [

25] examined the role of self-compassion and mediating emotion regulation difficulties in perinatal depression and anxiety. They found that higher self-compassion predicted lower perinatal anxiety and depression directly and indirectly via general emotion regulation difficulties. These specific difficulties included non-acceptance of emotions, lack of emotion awareness and clarity, limited access to emotion regulation strategies and engaging in goal directed behaviour, and impulse control. A similar relationship between emotion regulation and self-compassion has been shown in the prediction of social anxiety symptoms within a general student sample [

19]. As these studies used data collected before the COVID-19 pandemic, they do not indicate how COVID-19 may have influenced these relationships. The present study built on these studies by including assessments for possible COVID-19 experience impacts.

Some research sheds light on the relationship between perinatal distress during COVID-19 and specific emotion regulation strategies such as information seeking, self-efficacy, comfort eating, and self-blame [3,18, 28-32]. A study by Di Paolo [

33] explored how resilience, tolerance of uncertainty and cognitive appraisal of the pandemic’s consequences affected postpartum anxiety and found negative cognitive appraisals predicted higher postpartum anxiety during COVID-19. Nevertheless, the specific emotion regulation strategies that most strongly influence social anxiety, anxiety and depression symptoms in perinatal women remain largely unknown. In general population studies, Chesney et al., [

21] and Aldao et al.,[

34] established that adaptive emotion regulation strategies (i.e., acceptance, cognitive reappraisal and problem solving) relate to lower symptoms of anxiety and depression; whereas maladaptive strategies (i.e., avoidance, emotion suppression and rumination) increase symptoms. Building on Di Paolo’s findings on cognitive reappraisal, it is important to understand whether the relationships of specific adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and mental health outcomes are replicated in perinatal women [21, 34].

1.3. The Present Study

The overall aim of this study was to examine how self-compassion, emotion regulation strategies and COVID-related experiences influence anxiety, depression, and social anxiety symptoms in Australian perinatal women. It was predicted that:

Higher self-compassion and adaptive emotion regulation factors (acceptance, cognitive reappraisal, problem solving) would negatively correlate with anxiety, depression, and social anxiety symptoms.

High COVID-19 related stress, lower self-compassion, and maladaptive emotion regulation factors (lack of emotional understanding, expressive suppression, rumination) would positively correlate with anxiety, depression, and social anxiety symptoms.

Further, based on previous studies [

19,

23,

25], the relationship between self-compassion and mental health symptoms was expected to be mediated by adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies during COVID-19. COVID-19 perceived experiences were also expected to mediate the relationship between self-compassion and mental health symptoms because higher COVID-19 related concern would likely reduce the influence of self-compassion on mental health. It was hypothesised that:

Adaptive emotion regulation (acceptance, cognitive reappraisal, problem solving) would positively mediate the influence of self-compassion on anxiety, depression, and social anxiety symptoms.

Maladaptive emotion regulation (rumination, expressive suppression, lack of emotional understanding) and more negative COVID experience would negatively mediate the influence of self-compassion on anxiety, depression, and social anxiety symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

This study adopted a heterogeneous cross-sectional design, targeting women in various stages of the perinatal period from pregnancy or up to two years post-birth [

35]. The study received ethics clearance by the Swinburne University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number 20226567-10039). Inclusion criteria mandated participants to be 18 years or older and residents of Australia. Recruitment ensued through targeted emails to women enrolled in perinatal mental health services, while an additional avenue involved unpaid advertisements on social media platforms and online mothers’ group pages. Swinburne University students within the perinatal period were also invited through the Research Experience Program portal, earning course credit for participation. The utilisation of diverse recruitment channels was aimed at obtaining a more comprehensive and unbiased representation of the population of Australian perinatal women. Invitations, disseminated through emails and advertisements, included a survey link providing project details and an informed consent process. Participants retained the right to withdraw consent at any point by abstaining from submission.

To ascertain an optimal sample size for a moderate effect size, an a-priori G-power analysis was performed, indicating a requirement of 160 participants In the end, 265 participants completed the online survey. The total sample comprised women, aged 18-56, from diverse regions in Victoria and other states of Australia. Most of the participants were postnatal, married, or in partnerships, with a range of career paths and varying degrees of involvement in therapy.

Table 1 presents a detailed breakdown of participant characteristics.

2.2. Measures

COVID-19 Perceived Concerns

COVID-19 Perinatal Perception Questionnaire (COVID19-PPQ; [

36]). The COVID19-PPQ was developed in response to the first global lockdown in 2020 by surveying perinatal women on perceived COVID-19 related stress in the perinatal period. The questionnaire consisted of

pregnancy (nine-items, e.g., ‘it bothered me that my scheduled ultrasounds could not continue’) and

postpartum (10-items, e.g., ‘I was afraid that my partner would be infected with COVID-19’) subscales, measured with a 4-point response from 1 (Completely disagree) to 4 (Fully disagree). Higher scores indicated greater agreement of an unpleasant experience. The COVID19-PPQ was found to have adequate psychometric properties for both scales including appropriate reliability and adequate-excellent model fit.

Mental Health

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond, & Snaith, [

37]). The HADS is a 14-item self-report scale that assesses depression and anxiety symptoms in the previous week and is the most widely validated anxiety measures in the perinatal population [

38] and depression measure have substantial overlap with the Edinburgh Perinatal Depression Scale [

39]. The HADS comprised seven anxiety items (e.g., ‘I feel restless as I have to be on the move’), and seven depression items (e.g., ‘I feel as if I am slowed down’), answered on a 4-point Likert scale (from 0 to 3 with varied anchors). The total subscale scores range from 0 to 21 with higher scores indicating greater symptoms of anxiety and depression. A cut-off score of 11 or higher is indicative of clinical levels of anxiety and depression symptoms [

37].

The Social Interaction Phobia Scale (SIPS; [

40]. The SIPS is a combination of elements from two social anxiety scales, the Social Phobia Scale (SPS; Mattick & Clarke, 1998) and the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; [

41]), both on a five-point rating scale. The total SIPS score is calculated by summing the

social interaction anxiety (SIA) subscale (consisting of five SIAS items) the

fear of overt evaluation (FOE) subscale (consisting of six SPS items), and the

fear of attracting attention (FAA) subscale (consisting of three SPS items) the SIAS items are rated from 0 ‘Not at all characteristic or true of me’ to 4 ‘Extremely characteristic or true of me’, and the SPS items are rated from 0 = ‘Not at all characteristic or true of me’ to 4 = ‘Extremely characteristic or true of me’. The SIPS has enhanced utility and excellent internal consistency clinical (a= 0.95) and good internal consistency for non-clinical populations (alpha = 0.87; [

4]).

Emotion Regulation

Due to the paucity of emotion regulation research on the perinatal period, measures of adaptive and maladaptive regulation strategies were selected based on previous research and a survey of perinatal clinicians. Eight perinatal mental health clinicians provided their clinical opinion regarding the prevalence of commonly observed emotion regulation strategies within the perinatal population. The clinicians were provided with a list of regulation strategies taken from various emotion regulation scales to rate what strategies they notice more so [43-46]. Similarly to research by Chesney, Aldao and colleagues [

21,

34], acceptance, problem solving, expressive suppression, avoidance and rumination were identified by the clinicians as commonly observed in perinatal women accessing mental health support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though cognitive reappraisal was not suggested by the clinicians as common, it was also included given its prominence as a measure of adaptive emotion regulation in the literature [

21]. It is possible that the clinicians completing the survey based their responses on initial presentation to mental health services rather than effective strategies that may need to be developed such as cognitive reappraisal.

Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF; [

47]). The SCS-SF is a 12-item, shortened version of the 26-item Self-Compassion Scale [

26]. The short-form measures each of the six components of self-compassion identified by Neff [

26]. Three, two-item subscales are positively worded: Self-Kindness, Common Humanity, and Mindfulness, and three are negatively worded: Isolation, Over-Identification, and Self-Judgment. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1=almost never to 5= almost always. A total score is calculated by adding all 12 items with reverse scoring applied to negatively worded items. Higher scores reflect greater self-compassion. Raes et al. [

47] reported an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87 for the 12 item SCS-SF and a correlation of 0.97 with the long form.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; [

45]). The DERS is a self-report measure assessing emotion regulation difficulties.

Non-acceptance of emotional responses (six items),

lack of emotional awareness (six items),

lack of emotional clarity (five items),

difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour (five items) and

limited access to emotion regulation strategies (eight items) were included. All items were answered on a five-point response scale from 1 = Almost never to 5 = Almost always, with higher scores suggesting more difficulties in the use of each emotion regulation strategy. Non-acceptance was reversed coded as adaptive items of acceptance. All other subscales were included as maladaptive emotion regulation strategies.

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; [

44]). The ERQ is a 10-item measure assessing the emotional regulation strategies of

Expressive Suppression (ES; four items, e.g., ‘I keep my emotions to myself’) and

Cognitive Reappraisal (CR; six items), e.g., ‘When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I am thinking about the situation’). Respondents rate on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Gross and John reported good Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities for both scales across four samples (ES averaged 0.73 and CR averaged 0.79) and test–retest reliability was 0.69 over three months, as well as good construct validity.

Brief COPE scale – Problem-focused coping subscale (Brief-COPE; [

43]). The Brief-COPE problem focused subscale is an eight-item self-report subscale that measures coping strategies aimed at changing the stressful situation. All items are answered on a 4-point response scale 1 = I haven’t been doing this at all to 4 = I have been doing this a lot, indicating how much they perceive themselves to be using each strategy including active coping, planning, and using information supports. For this study two items measuring positive reframing were removed to avoid overlap with the ERQ assessment of cognitive reappraisal. Therefore, six items were used from the problem focused subscale.

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire – Rumination subscale (CER [

46]). The CERQ Rumination scale holds four items that assesses cognitive rumination (e.g., “I am preoccupied with what I think and feel about what I have experienced”). Items are measured on a five-point response scale 1= Almost never to 5 = Almost always, with higher scores indicating greater frequency of use of rumination. Empirical derived measure of rumination developed by Chesney et al. [

21] with sound psychometric properties including good factorial validity and high reliabilities with alphas ranging between 0.75 and 0.87.

2.3. Data Analysis

Prior to the analyses, data from all measures were checked for missing data, univariate and multivariate outliers, skewness, and kurtosis (see

Table 2). All variables appeared normally distributed with no skewness or kurtosis and no outliers. While there was some missing data, this did not exceed five percent of responses on any measure and therefore mean substitution was used for missing data [

48]. After these analyses, relationships among the measures were examined using bivariate Pearson product-moment correlations. The mediation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS V4.2 (model 4) macro for SPSS [

49]. The models used five thousand bootstrapped samples and percentiles-base ninety five percent confidence intervals. Three parallel mediation models were used to assess the indirect effects of maladaptive and adaptive emotion regulation on self-compassion relationship with the three mental health outcomes in perinatal women (anxiety, depression, and social anxiety). Further prevalence analyses were conducted to assess the percentage of perinatal women in the overall sample with scores above the clinical cut off scores for HADS anxiety and depression (>11; [

37]) and SIPS (>12; [

40]) scores as well as the percentage of women engaged in therapy. Respectively 93.2%, 70.9% and 65.7% of women presented with clinically significant anxiety, depression, and social anxiety scores. Similarly, across the HADS and SIPS mean scores sat well above the clinical cut off highlighting a largely clinical sample.

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to compare current, recent or no engagement in therapy on mental health outcomes. MANOVA indicated differences across the three level of therapy engagement groups for anxiety, depression, and social anxiety (Pillai’s trace = 0.058, F(6, 518) = 2.57, p <.05, partial eta squared = 0.030. Univariate tests showed that the group difference was confined to scores on anxiety (F(2, 260) = 6.21, p = <0.01, partial eta squared = 0.046). Student Neuman Keuls post hoc analysis confirmed that currently being in therapy was associated with a significant increase in anxiety scores in comparison to not being in therapy. Therefore, therapy was included as a covariate in the mediation analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Analyses

As hypothesised (H1), the bivariate correlations (see table 3) indicated that anxiety, depression and social anxiety measures (HADS & SIPS) had strong negative associations with self-compassion and the adaptive emotion regulation measures (acceptance, cognitive reappraisal, problem solving). In addition, maladaptive emotion regulation measures (lack of emotional understanding, expressive suppression, rumination, lack of goal directed behaviour and lack of emotion regulation strategies) had strong positive associations with anxiety, depression, and social anxiety. High COVID-19 perceived experience in postnatal women had a weak positive correlation with anxiety and depression but not social anxiety. Additionally, higher COVID-19 perceived experience in postnatal women (n=235) had a strong negative correlation with self-compassion. COVID-19 perceived experience in pregnant women failed to significantly correlate with any mental health outcomes.

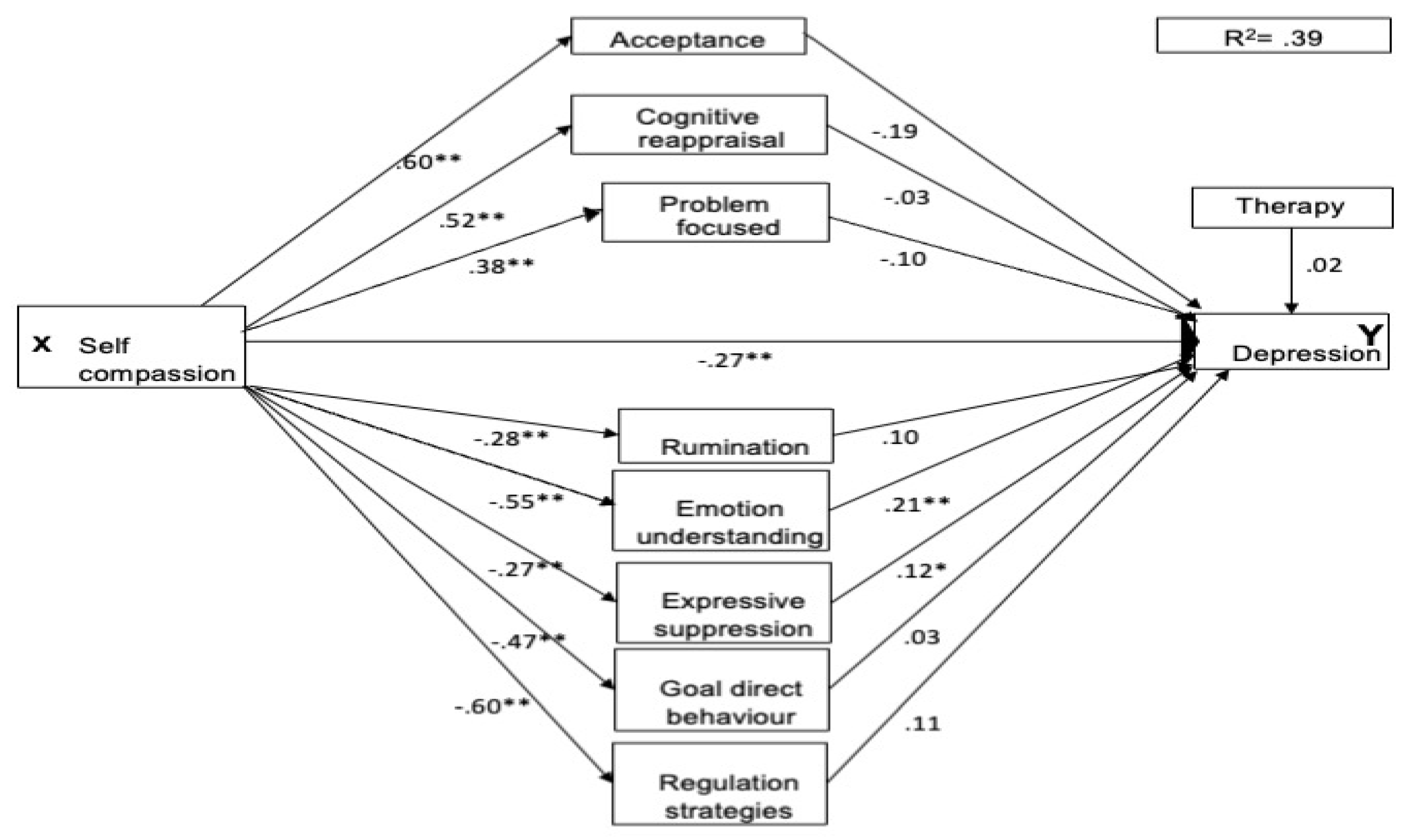

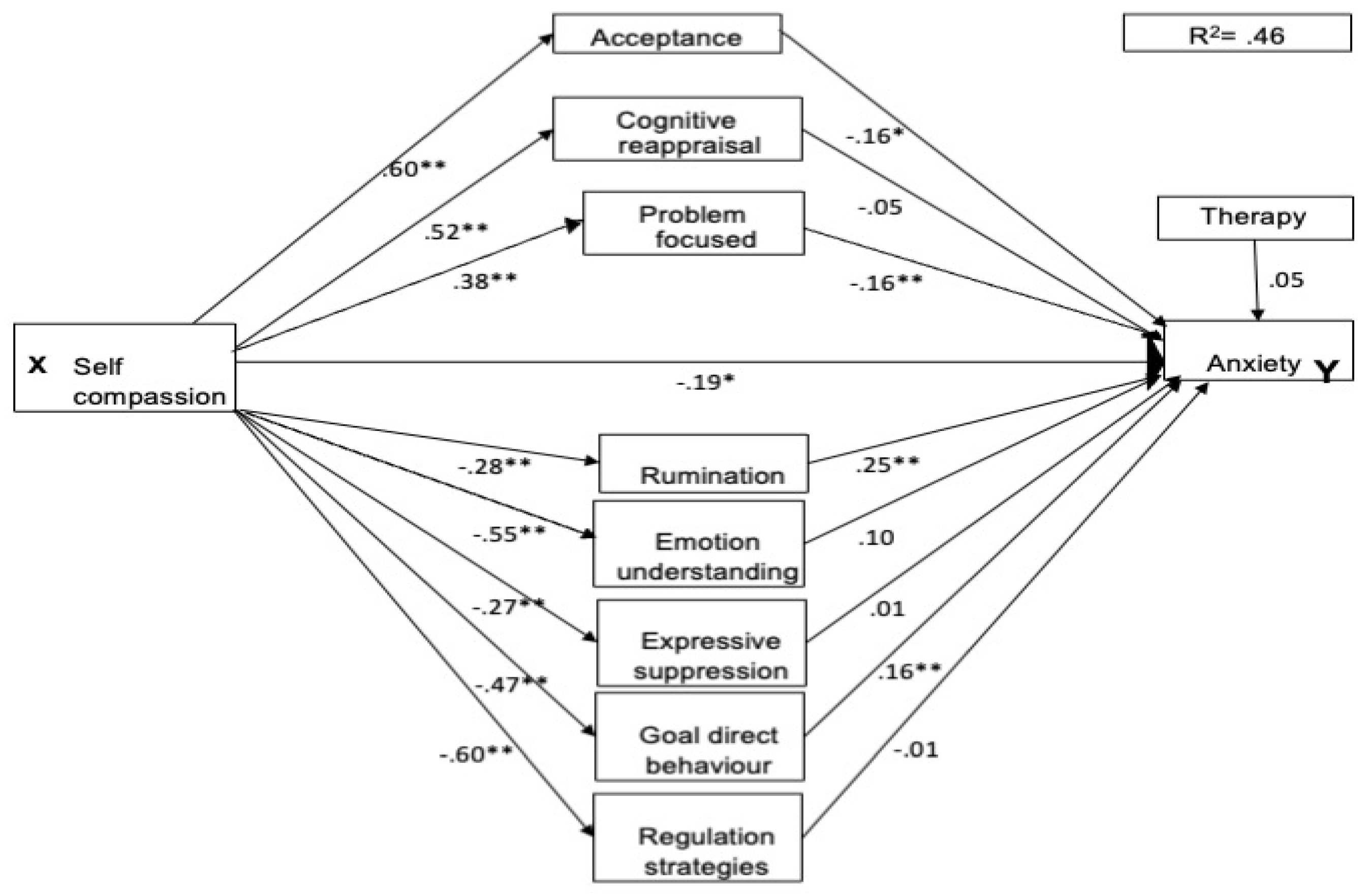

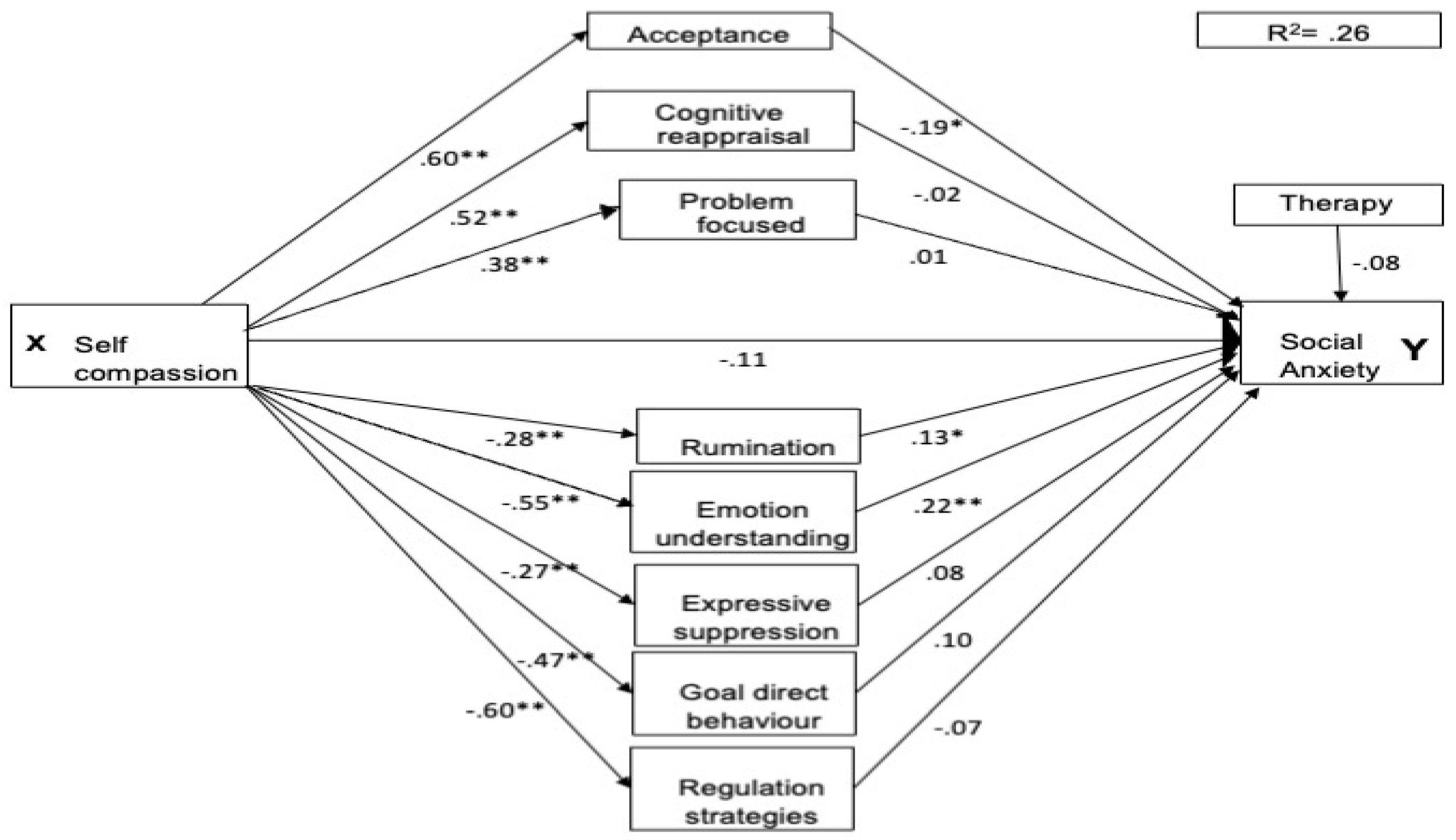

As two participants did not specify their therapy experience, the three parallel mediation analyses each included 263 participants. For all three mental health conditions the pathways between self-compassion and each of the emotion regulation strategies was significant. Higher self-compassion directly predicted lower maladaptive emotion regulation scores and higher adaptive emotion regulation scores (see figures 1-3). For the adaptive pathways self-compassion was a significant positive predictor for acceptance (βse =.60, p<.001, 95% CI [3.81, 5.38]), cognitive reappraisal (βse =.52, p<.001, 95% CI [3.70, 5.67]) and engagement in problem focused strategies (βse =.38, p<.001, 95% CI [1.74, 3.32]). For the maladaptive pathways it was a significant negative predictor for rumination (βse =-.28, p<.001, 95% CI [-.43, -.18]) , lack of emotion understanding (βse =-.55, p<.001, 95% CI [-6.49, -4.35]) , expressive suppression (βse =-.27, p<.001, 95% CI [-2.65, -.99]) , lack of goal directed behaviour (βse =-.47, p<.001, 95% CI [-3.19, -1.96]), and lack of access to regulation strategies (βse =-.61, p<.001, 95% CI [-6.13, -4.36]). The therapy covariate was non-significant for all mental health conditions.

The total effect of self-compassion was significant for depression (βse =-.55, p<.001, 95% CI [-3.38, -2.27]), anxiety (βse =-.57, p<.001, 95% CI [-4.03, -2.77]), and social anxiety (βse =-.42, p<.001, 95% CI [-9.85, -5.54]).

3.3. Prediction of Depression

Self-compassion strongly predicted lower scores of depression symptoms (β

se =-.27,

p<.01, 95% CI [-2.20, -0.52]) in the perinatal sample and indirectly through lack of emotion understanding (β

se =-.21,

p<.001, 95% CI [0.05, 0.18]). Self-compassion also held an indirect relationship with expressive suppression as a modest predictor (β

se =.12,

p<.05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.18]) . Interestingly, rumination, goal directed behaviour, access to regulation strategies and all adaptive emotion regulation strategies were non-significant mediators for depression (refer to

Figure 1).

3.4. Prediction of Anxiety

Although a modest effect, self-compassion directly (β

se =-.19,

p<.05, 95% CI [-2.07, -0.24]) predicted reduced anxiety symptoms. Self-compassion also strongly and indirectly predicted lower anxiety scores via the mediators of rumination (β

se = 0.25,

p<.001, 95% CI [0.83, 2.03]), goal directed behaviour (β

se =.16,

p<.01, 95% CI [0.04, 0.31]) and problem focused strategies (β

se = -.16,

p<.01, 95% CI [-0.24,-0.04]) (see

Figure 2). Acceptance was also a modest mediator of the relationship between self-compassion and anxiety (β

se =-.16,

p<.05, 95% CI [-2.20, -0.52]). When problem focused strategies and acceptance were higher, anxiety symptoms reduced. Alternatively, when high rumination and a lack of goal directed strategies were reported, anxiety scores increased. Access to emotion regulation strategies, expressive suppression, emotion understanding, and cognitive reappraisal were non-significant moderators for anxiety scores. See figure two for the parallel mediation model for anxiety.

3.5. Prediction of Social Anxiety

Unlike depression and anxiety, self-compassion was fully mediated as a predictor of social anxiety scores (see

Figure 3; β

se =-.11,

p=.21, 95% CI [-5.38, 1.20]). The significant mediators were emotion understanding which was a strong mediator (β

se =-.22,

p<.01, 95% CI [0.16, 0.68]); increased rumination (β

se =.13,

p<.05, 95% CI [0.20, 4.44]) and Acceptance (β

se =-.19,

p<.05, 95% CI [0.05, 0.85]) both of which had modest effects. The other potential mediators of cognitive reappraisal, problem focused strategies, expressive suppression, lack of goal-directed behaviour and regulation strategies failed to predict social anxiety scores.

4. Discussion

The present study examined self-compassion, emotion regulation strategies, and COVID-19 perceived experience as predictors of perinatal anxiety, depression, and social anxiety. As expected, (hypothesis one), and consistent with non-perinatal research [

19,

21,

23], increased self-compassion and adaptive emotion regulation factors correlated with lower symptoms of depression, anxiety and social anxiety. Alternately, and in partial support of the second hypothesis, lower self-compassion and greater maladaptive emotion regulation related to higher depression, anxiety, and social anxiety symptoms in perinatal women. The mediation hypotheses were also partially supported with unique adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies mediating the influence of self-compassion for depression, anxiety and social anxiety. For depression symptoms, a lack of emotion understanding, and expressive suppression were positive mediators. For anxiety symptoms, rumination, goal-directed behaviour, acceptance and problem-focused strategies were significant mediators. For social anxiety symptoms, acceptance, lack of emotion understanding, and rumination were significant mediators. Interestingly, whereas self-compassion’s effect was partially mediated for anxiety and depression, it was fully mediated for social anxiety.

Despite being a broad community sample of perinatal women, there was a high representation of clinical levels on self-reported depression (70.9%), anxiety (93.2%) and social anxiety (65.7%). Notably, women who were engaged in therapy had significantly higher general anxiety scores than those who had not received psychological treatment in the last two years. Taken together, these findings emphasise the need to better understand the specific factors that either exacerbate or alleviate perinatal mental health issues to better support perinatal women in therapy. This discussion focuses on the finding that COVID-19 experience did not influence depression, anxiety, and social anxiety, and on the unique emotion regulation strategies which mediated the effects of self-compassion on perinatal mental health outcomes. The final section discusses methodological considerations and directions for further research.

4.1. The Influence of COVID-19 Pandemic Experience

Despite widespread concerns regarding the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perinatal mental health [5-8], in our study the perceived experience of COVID did not correlate significantly with social anxiety in either pregnant or postnatal women. Furthermore, there was only a weak association with depression and anxiety, and these associations were observed solely in postnatal women. This suggests that the heightened mental health concerns observed in perinatal women during their postnatal phase persisted during the pandemic, but this was not necessarily attributable to their COVID experiences in pregnancy and post-birth. As the data were collected in the later stages of the pandemic, it may also be that the sense of threat from COVID-19 had dissipated at the time the women completed the survey and so had less intense influence on the relationship between self-compassion and mental health outcomes. Excluding the COVID-19 experience measure from the parallel mediation analyses permitted a focus on how specific emotion regulation strategies mediated the predictive relationship between self-compassion and perinatal mental health outcomes.

4.2. Specific Predictors of Perinatal Depression

The results for perinatal depression aligned somewhat with expectations, revealing that self-compassion predicted depression symptoms both directly and indirectly. This mirrors the findings of Carona et al [

25] that higher self-compassion directly predicted lower depression symptoms in perinatal women. To build on these findings, future research could look at specific self-compassion features to identify whether self-kindness (vs self-judgement), awareness of common humanity in during challenge (vs feeling isolated in suffering), or engagement in mindfulness (vs overidentification with difficult experience; [

26]) are more important for reducing postnatal depression.

The current study also identified emotion regulation strategies that were the most influential mechanisms of the influence of self-compassion on perinatal depression. This extends Corona et al.’s finding that general deficits in emotion regulation mediated the effect of self-compassion on perinatal depression. The specific emotion regulation strategies identified were

lack of emotion understanding and

expressive suppression. The

emotional understanding subscale comprises both an awareness of emotions as they are occurring, and clarity about which emotion is being experienced. In contrast,

Expressive suppression is a form of experiential avoidance which exacerbates distress through attempts to inhibit the expression of emotion [

17]. Therefore, the more that perinatal women are aware and clear on the emotion they are experiencing and the more they can express that emotion the greater will be the benefits of self-compassion on reducing depression. This is because self-compassion helps the person to recognise suffering and taking action to alleviate it [

26].

Contrary to other research (e.g., [

50]), rumination did not predict depression in this sample, despite it being known as a prominent maintaining feature in depression [

51]. It is possible that the limited number of items in our measure may not have covered all relevant features of rumination in depression and so was less representative of depressive rumination. Moreover, the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire (CERQ; [

46]) rumination subscale items such as “I dwell on the feelings the situation has evoked in me” could have been interpreted as worrying about emotions, which is more in line with anxiety than depression. Supporting this possibility, rumination did significantly predict anxiety in this study. To better understand the effect rumination has on the relationship of self-compassion and perinatal depression, future research could use a more comprehensive measure of rumination to fully test the role of rumination in perinatal women (e.g., Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; [52-54]). As they stand, our findings suggest that it is most useful to focus on improving emotional understanding and reducing expressive suppression to enhance the effect of self-compassion on perinatal depression.

4.3. Specific Predictors of Perinatal Anxiety

Consistent with our hypotheses, and findings from preliminary perinatal research [

23,

33], self-compassion directly predicted perinatal anxiety symptoms. This finding supports Felder et al. [

23] who found that 10-24% of variance in perinatal anxiety could be explained by self-compassion. The direct pathway between self-compassion and anxiety, however, exhibited robust mediators that were different to those identified for depression.

Rumination,

goal-directed behaviour, and

problem-focused strategies were mechanisms of the influence of self-compassion on anxiety. Unlike self-compassion’s relationship with depression, rumination mediated its influence such that rumination reduced the effect self-compassion had on lowering anxiety. As previously mentioned, our rumination measure’s items may align with features of worry as well as rumination, and this may account for the heightened influence of rumination on anxiety within this sample. Considering that worry constitutes a fundamental aspect of anxiety ([

55]), it follows logically that elevated levels of worry could impede perinatal women’s capacity to cultivate self-compassion as a means of mitigating anxiety symptoms. Importantly, future research could better understand how rumination predicts perinatal anxiety by using a measure of worry (e.g., Penn State Worry Questionnaire, [56]) and a comprehensive rumination scale. Moreover, it is plausible that directing awareness towards goal-oriented and problem-focused strategies might enhance the effects of self-compassion and alleviate anxiety symptoms by providing women with a heightened sense of control over prevailing issues during this critical period. Acceptance of anxiety symptoms will also help alleviate concerns about emotional states, creating a mental space conducive to the cultivation of self-compassion.

Referring to Neff’s [

26] model of self-compassion, it follows that if perinatal women increase their focus on ways of solving problems and directing thoughts toward goals that support them and their baby this will enhance experiences of self-kindness, mindfulness and normalising their perinatal experience as common humanity. Likewise, building acceptance of their unique experiences as soon to be or new mothers may reduce worries regarding the unknown and fears of motherhood, whereas ruminating over them would only increase the presence of anxiety to be a “good mother” [

16]. Taken together, these findings provide unique insights into emotion regulation strategies that might best support perinatal women to prevent and reduce perinatal anxiety during such a valuable time in their lives.

4.4. Novel Insights into Perinatal Social Anxiety

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first exploration of social anxiety in perinatal women. Notably, 65.7% of our sample surpassed the clinical cut off for social anxiety scores on the SIPS. This alone underscores the necessity for deeper investigation of the influence of social anxiety among perinatal women, considering the substantial social transformations experienced by women during this period in their lives [

16].

Unlike the predictive pathways for anxiety and depression, self-compassion’s effect on social anxiety was fully mediated by emotion regulation strategies. This was unexpected as self-compassion has been found to be partially mediated in predicting social anxiety within a general community sample ([

21]). Respectively, a lack of

emotion understanding, and increased

rumination predicted greater social anxiety symptoms and higher acceptance had a negative effect on social anxiety. The items of the non-acceptance of emotions scale capture negative evaluations of the self for experiencing distress (e.g. “When I’m upset, I feel ashamed of myself for feeling that way”.). Such experiences of shame and self-criticism for having social anxiety are major features of the condition ([57]). Thus, the effects of compassion toward the self in reducing social anxiety will be enhanced when the person has a greater level of acceptance of the emotion they are experiencing and a clear understanding of the emotion. In addition, reducing rumination enhances the benefits of self-compassionate responses to distress. These findings highlight the gap in our understanding of how social anxiety presents for perinatal women and the benefits of constructive emotion regulation strategies and self-compassionate responding for perinatal women experiencing social anxiety.

4.5. Methodological Considerations and Directions for Future Research

A strength of this study was the relatively large, diverse, and widespread perinatal sample drawn from across Australia. However, using a convenience and heterogeneous sampling method limits the capacity to generalise the results to the overall population of perinatal women. Also, our data were drawn from a largely clinical sample of perinatal women, and this may have raised the levels of depression, anxiety and social anxiety symptoms relative to the general population. In addition, use of cross-sectional data means our findings cannot determine causality in the identified relationships. Nevertheless, given this was an exploratory study, the data will assist in framing future longitudinal research with more generally representative samples of perinatal women.

Given that specific emotion regulation strategies in the perinatal population had not been explored before, this study chose to focus on well researched emotion regulation strategies with an introspective focus. Future research could include analyses for exteroceptive emotion regulation strategies such as behavioural avoidance. This would extend our knowledge of possibly helpful (or unhelpful) behavioural regulation strategies to support self-compassion and mental health outcomes. Moreover, use of self-report measures poses a risk of results being influenced by participant honesty, bias, and introspective ability. To reduce this risk, in this study only well researched and validated measures used with the perinatal population and for assessing mental health outcomes were included. Future research could look to confirm the findings possibly through observational and single case study research with the use of state and trait measures.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides novel and unique insights into the influence of specific emotion regulation strategies, including self-compassion, directional and predictive relationships for perinatal mental health outcomes. Importantly, we found that different emotion regulation strategies were important for different mental health issues. This highlights the need for further work on how emotion regulation strategies can be incorporated into interventions for the prevention and treatment of perinatal depression, anxiety, and social anxiety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design, K.C. and G..B.; data curation and acquisition, G.B., formal analysis, K.C., and G.B.; funding acquisition, G.B.; investigation, K.C.; methodology, K.C., and G.B.; project administration, G.B.; resources, G..B. ; software, K.C; supervision, G.B; validation, K.C; visualisation, K.C., and G..B.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C; writing—review and editing, K.C., and G.B. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in the study that involved human participants followed the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The Swinburne University of Technology ethics board granted permission for the study to proceed (approval number 20226567-10039, June 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided informed consent at the beginning of survey and were informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. Also, they were assured that the questions did not contain any personally identifiable information, and that the data collected would be used for the stated research purposes only.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request and university ethics approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Howard, L. M. , & Khalifeh, H. Perinatal mental health: A review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bales, M. , Pambrun, E., Melchior, M., Glangeaud-Freudenthal, N. M., Charles, M. A., Verdoux, H., et al. Prenatal psychological distress and access to mental health care in the ELFE cohort. European Psychiatry 2015, 30, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryson, H. , Perlen, S., Price, A., Mensah, F., Gold, L., Dakin, P., & Goldfeld, S. Patterns of maternal depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms from pregnancy to 5 years postpartum in an Australian cohort experiencing adversity. Archives of Women’s Mental Health 2021, 24, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, L. S. , Poyser, C., & Fairweather-Schmidt, K. Maternal perinatal anxiety: A review of prevalence and correlates. Clinical Psychologist 2017, 21, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, M. , Hompes, T., & Foulon, V. (2020). Mental health status of pregnant and breastfeeding women during the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. [CrossRef]

- Davenport, M. H. , Meyer, S., Meah, V. L., Strynadka, M. C., & Khurana, R. Moms Are Not OK: COVID-19 and Maternal Mental Health. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health. [CrossRef]

- Lebel, C. , MacKinnon, A., Bagshawe, M., Tomfohr-Madsen, L., & Giesbrecht, G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders 2020, 277, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y. , Zhang, C., Liu, H., Duan, C., Li, C., Fan, J., et al. Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020, 223, 240–e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S. Y. , Ng, E. D., & Chee, C. Y. I. Anxiety and depressive symptoms of women in the perinatal period during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2021, 49, 730–740. [Google Scholar]

- Perinatal Anxiety and Depression Australia. (2021). Annual Review 20/21. PANDA.

- Sutherland, D. Increased Demand for Perinatal Mental Health Support during Covid-19. Australian Midwifery News 2020, 21, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C-L, Falah-Hassani K and Shiri R. (2017).Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry,23,. [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020-21). National Study of Mental Health and Wellbeing. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.

- Kindred, R. , & Bates, G. The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Social Anxiety: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, D. J.; et al. The cross-national epidemiology of social anxiety disorder: Data from the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. BMC Med 2017, 15, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. , Houghton, C., & Matvienko-Sikar, K. Women’s experiences and perceptions of anxiety and stress during the perinatal period: a systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. Emotional regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werchan, D. M. , Hendrix, C. L., Ablow, J. C., Amstadter, A. B., Austin, A. C., Babineau, V., Anne Bogat, G., Cioffredi, L.-A., Conradt, E., Crowell, S. E., Dumitriu, D., Fifer, W., Firestein, M. R., Gao, W., Gotlib, I. H., Graham, A. M., Gregory, K. D., Gustafsson, H. C., Havens, K. L., & Howell, B. R. Behavioral coping phenotypes and associated psychosocial outcomes of pregnant and postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, G. W. , Elphinstone, B., & Whitehead, R. Self-compassion and emotional regulation as predictors of social anxiety. Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice 2021, 94, 426–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, T. , Steindl, S. R., Kirby, J. N., & Kane, R. T. The Relationship Between Self-Compassion and Depressive Symptoms: Avoidance and Activation as Mediators. Mindfulness 2021, 12, 1748–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney, S. A. , Timmer-Murillo, S. C., & Gordon, N. S. Establishment and replication of emotion regulation profiles: implications for psychological health. Anxiety, Stress & Coping 2019, 32, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, G.W. , McBride N.L., & Pang, Y. (2022). The Influence of Emotional Regulation and Self-Compassion on Social Anxiety. In A.M. Columbus. Advances in psychological research, Volume 148. N: Publisher.

- Felder, J. , Lemon, E., Shea, K., Kripke, K., & Dimidjian, S. Role of self-compassion in psychological well-being among perinatal women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health 2016, 19, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, D. V. , Canavarro, M. C., & Moreira, H. The role of mothers’ self-compassion on mother–infant bonding during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study exploring the mediating role of mindful parenting and parenting stress in the postpartum period. Infant Mental Health Journal 2021, 42, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carona, C. , Xavier, S., Canavarro, M. C., & Fonseca, A. (2022). Self-compassion and complete perinatal mental health in women at high risk for postpartum depression: The mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties. Psychology & Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity 2003, 2, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubman, B. O. , Chasson, M., & Abu, S. S. Childbirth anxieties in the shadow of COVID-19: Self-compassion and social support among Jewish and Arab pregnant women in Israel. Health & Social Care in the Community 2021, 29, 1409–1419. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, A. , Kim, H. H., Basaldua, R., Choi, K. W., Charron, L., Kelsall, N., Hernandez-Diaz, S., Wyszynski, D. F., & Koenen, K. C. A cross-national study of factors associated with women’s perinatal mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M. Anxiety, Fear, and Self-Efficacy in Pregnant Women in the United States During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Prenatal & Perinatal Psychology & Health 2021, 35, 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, J. E. , Atkinson, L., Bennett, T., Jack, S. M., & Gonzalez, A. Coping strategies mediate the associations between COVID-19 experiences and mental health outcomes in pregnancy. Archives of Women’s Mental Health 2021, 24, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinser, P. A. , Jallo, N., Amstadter, A. B., Thacker, L. R., Jones, E., Moyer, S., Rider, A., Karjane, N., & Salisbury, A. L. Depression, Anxiety, Resilience, and Coping: The Experience of Pregnant and New Mothers During the First Few Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Women’s Health (15409996) 2021, 30, 654–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J. M. , Misra, D. P., & Giurgescu, C. Stress and coping among pregnant black women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nursing 2021, 38, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Paolo. (2022). Prenatal stress from the COVID-19 pandemic predicts maternal postpartum anxiety as moderated by psychological factors: The Australian BITTOC Study. Journal of Affective Disorders.

- Aldao, A. , Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review 2010, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, A. , Blake-Lamb, T., Hatoum, I., & Kotelchuck, M. Women’s Use of Health Care in the First 2 Years Postpartum: Occurrence and Correlates. Maternal and Child Health Journal 2016, 20, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulsbosch, L. P. , Boekhorst, M. G. B. M., Muskens, L., Potharst, E. S., Nyklíček, I., & Pop, V. J. M. Development of the COVID-19 Perinatal Perception Questionnaire (COVID19-PPQ). Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment 2021, 43, 735–744. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A. S. , & Snaith, R. P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meades, R. , & Ayres, S. Anxiety measures validated in perinatal populations: a systematic review. Journal of affective disorders 2011, 133, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, J. L. , Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleton, R. N. , Collimore, K. C., Asmundson, G. J., McCabe, R. E., Rowa, K., &Antony, M. M. Refining and validating the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale. Depression and Anxiety 2009, 26, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattick, R. P. , & Clarke, J. C. Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1998, 36, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modini, M. , Abbott, M. J., & Hunt, C. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of trait social anxiety self-report measures. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2015, 37, 645–662. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C. S. You want to measure coping but your protocol is too long: Consider the brief cope. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. , & John, O. P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar]

- Gratz, K. L. , & Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski, N. , & Kraaij, V. The cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 2007, 23, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F. , Pommier, E., Neff,K. D., & Van Gucht, D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy 2011, 18, 250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B. G. , & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics.

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. (Third edition). New York; Guilford Publications.

- Connolly, S. L. , & Alloy, L. B. Rumination interacts with life stress to predict depressive symptoms: An ecological momentary assessment study. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2017, 97, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. , Vine, V., Gilbert, K. (2013). Handbook of psychology of emotions. 1: recent theoretical perspectives and novel empirical findings.

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. , & Morrow, J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1991, 61, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Treynor, W. , Gonzalez, R., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research 2003, 27, 247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Gana, K. , Martin, B., & Canouet, M.-D. Worry and Anxiety: Is There a Causal Relationship? Psychopathology 2001, 34, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, T. J. , Miller, M. L., Metzger, R. L., & Borkovec, T. D. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1990, 28, 487–495. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).