Submitted:

15 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Urban Economics Integration

2.2. ESG in Real Estate: Global Standards, Regulatory Pressure, and Performance Gaps

2.3. Mixed-Use Urbanism: Theoretical Roots and Sustainability Promise

2.4. Anchor Tenants: Typology, Theoretical Models, and Empirical Evidence

2.5. ESG Certification: Frameworks, Limits, and Regulatory Convergence

2.6. ESG and Capital Formation: Finance, Disclosure, and Investment Risk

2.7. Comparative International Evidence: Models and Risks

2.8. Literature Gaps and Research Agenda

3. Methodology

3.1. Anchor tenant typology.

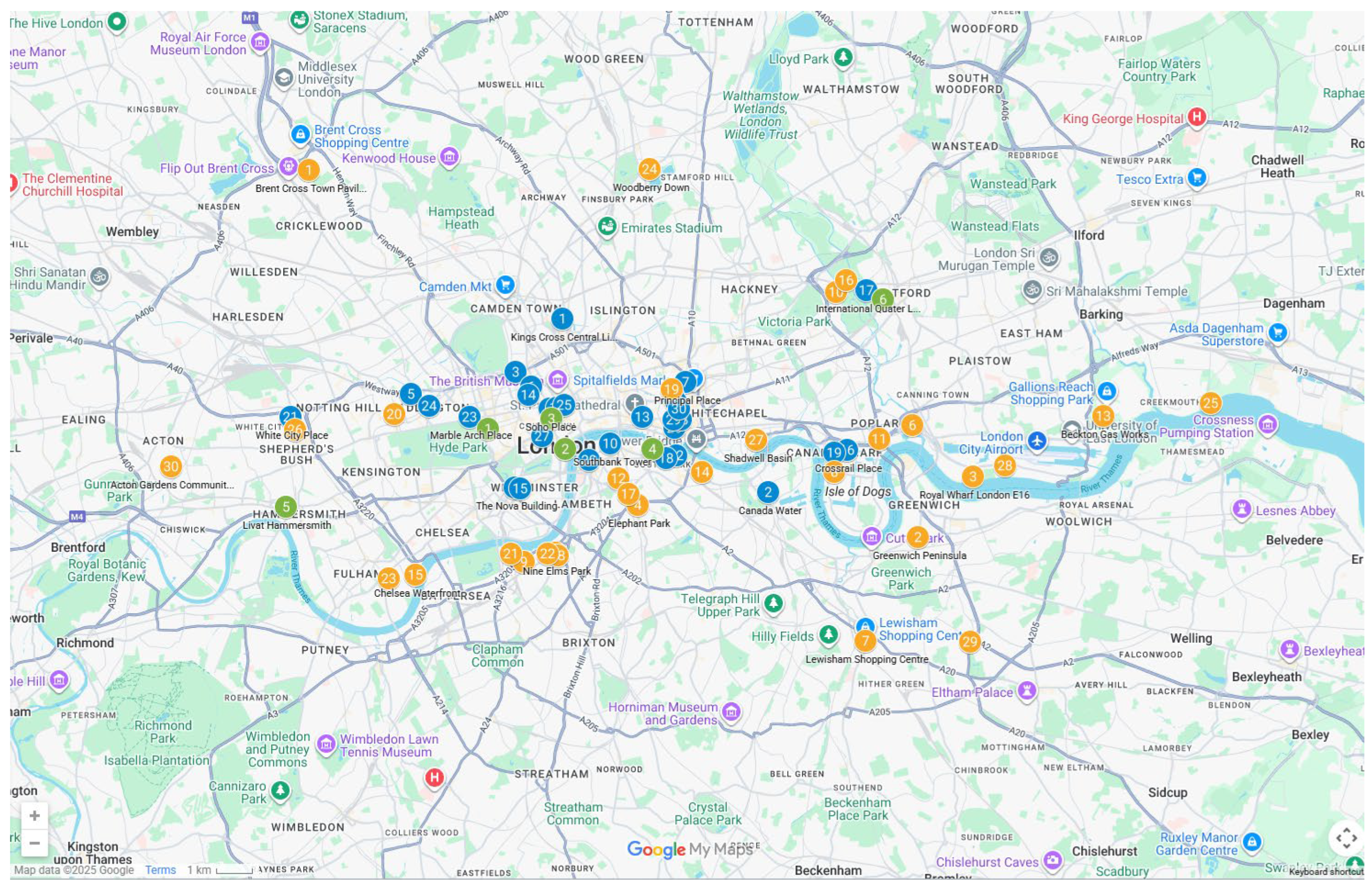

- Sustainability indicators from the BRE BREEAM directory and UK Government EPC Register (EPC, 2025).

- Governance indicators (evidence of green lease adoption, tenant ESG maturity) from corporate sustainability reports, TCFD disclosures, analyst presentations, and industry market research. See full details of assets analysed in the Supplementary Information.

- Control variables including estimated gross lettable area (GLA), year of completion/refurbishment, borough, London zone, and provision of public realm from developer websites, planning applications, leasing announcements, and investment presentations.

3.2. Composite ESG Scoring Framework

- a)

- Establishing the measurement approach

- b)

- Designing the Framework

- Environmental dimension: BREEAM certification and EPC ratings, capturing energy and compliance benchmarks embedded in UK regulation.

- Social dimension: the quality of public realm and transport accessibility, assessing wellbeing and connectivity contributions at community level.

- Governance dimension: the likelihood of green lease adoption and anchor tenant ESG maturity, reflecting alignment of landlord-tenant sustainability objectives and data transparency.

- c)

- Validating the Structure

- d)

- Accounting for Scale and Location

- e)

- Diagnostic and Robustness Tests

- f)

- Integration into the Analytical Model

3.3. ESG Score Calculation:

3.4. Statistical Analysis and Modelling

- Descriptive Statistics: Computed for the sample by anchor type—mean, median, SD, min, max; distributional boxplots for visualisation.

-

Group Comparison Tests

- ○

- Welch’s t-test for Office vs Residential comparisons (assumes unequal variances).

- ○

- Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric confirmation.

- ○

- Kruskal–Wallis test for all typologies (performed exploratorily due to small n for retail/hotel anchors).

3.5. Regression Models

- Model 1: ESG regressed on Office dummy (1=Office, 0=Residential)

- Model 2: ESG regressed on Office dummy + Year of completion

- Model 3: ESG regressed on Office dummy + locational controls (Zone 1, Zone 2)

- Model 4: Full specification adding scheme size (lnGLA) and tenant ESG maturity

- Model 5: Interaction Model (Office dummy × Tenant ESG maturity)

3.6. Pillar-Level Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

- Conceptual Framework & Hypotheses

- H1 (Formal): Office-anchored mixed-use developments achieve higher composite ESG scores than residential-anchored ones, reflecting greater tenant governance capacity and regulatory compliance.

- H2 (Exploratory): Tenant ESG maturity positively moderates typology effects — more mature anchors strengthen sustainability outcomes.

- H3 (Exploratory): Social sustainability indicators vary more strongly by anchor typology than environmental ones, which are increasingly standardised through regulation.

4. Calculations

4.1. Statistical Rationale

- Descriptive statistics: Means, standard deviations, interquartile ranges.

- Parametric tests (Welch’s t-test) due to unequal variances in anchor groups.

- Nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis) for robustness in distributional checks.

- OLS regression models: Sequential addition of controls and interaction terms.

- Robustness checks: Heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors, proxy-free subsamples, and alternative weightings.

4.2. Data Preparation

- Normalization: All ESG indicators were normalized to a 0–4 scale.

- Composite Score: Weighted as per methodology:

- Missing Data Handling: Imputation via mid-point if ranges provided; proxies flagged.

4.3. Group Comparisons Testing

-

Welch’s t-test calculation, Testing office (n=30) vs residential (n=30) anchors:

- ○

- Mean ESG (Office): 74.42 (SD = 11.25)

- ○

- Mean ESG (Residential): 68.08 (SD = 11.56)

- ○

- t(57.96) = 2.15, p = 0.04

-

Mann-Whitney U calculation, non-parametric check:

- ○

- U = 315.5, Z = –1.99, p = 0.047

4.4. Regression Modelling

-

Model Specification

- ○

- Model 1: ESG = β₀ + β₁OfficeDummy + ε

- ○

- Model 2: ESG = β₀ + β₁OfficeDummy + β₂Year + ε

- ○

- Model 3: ESG = β₀ + β₁OfficeDummy + β₂Year + β₃Zone1 + β₄Zone2 + ε

- ○

- Model 4: ESG = β₀ + β₁OfficeDummy + β₂Year + β₃Zone1 + β₄Zone2 + β₅lnGLA + β₆ESGMaturity + ε

- ○

- Model 5: ESG = β₀ + β₁OfficeDummy + β₂Year + β₃Zone1 + β₄Zone2 + β₅lnGLA + β₆ESGMaturity + β₇(Office×ESGMaturity) + ε

4.5. Regression Diagnostics

- Breusch–Pagan test for heteroscedasticity.

- Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) < 1.3 for multicollinearity.

- HC1 standard errors where heteroscedasticity detected.

4.6. Pillar-Level Analysis

-

Office vs residential mean differences for:

- ○

- Environmental Pillar: t(58.0) = 1.93, p = 0.06 (marginally significant)

- ○

- Social Pillar: t(57.9) = 0.92, p = 0.36 (not significant)

- ○

- Governance Pillar: t(57.8) = 1.84, p = 0.07 (marginally significant)

5. Results

5.1. Comparative Hypothesis Testing (H₁: Office > Residential)

5.2. Practical significance:

5.3. Regression and Moderation Analysis (H₂)

5.4. Pillar-Level Analysis (H₃)

- Environmental: t(58.0) = 1.93, p = 0.06 (marginal). Convergence indicates policy effectiveness—MEES and the London Plan have largely standardised environmental performance.

- Social: t(57.9) = 0.92, p = 0.36 (ns). Social parity arises from planning-imposed public-realm and accessibility obligations across all typologies.

- Governance: t(57.8) = 1.84, p = 0.07 (borderline). Governance maturity remains the distinguishing factor underpinning residual variance.

5.5. Robustness Checks and Sensitivity

6. Discussion

6.1. Institutional Convergence under Regulatory Pressure

6.2. Mechanisms of ESG Equalisation

- Formalised data-sharing. Green leases allow energy and emissions transparency, operationalising landlord–tenant co-management.

- Joint ESG committees. Estate-wide governance bodies institutionalise monitoring and collective target-setting, supporting sustained improvement.

- Sustainability-linked finance. Loan covenants link interest-rate adjustments to verified ESG KPIs, incentivising consistent performance across anchors.

6.3. Implications for Capital Markets and Valuation

- Underwriting: ESG maturity becomes a risk proxy influencing debt pricing (reported advantage 25–50 bps).

- Portfolio valuation: REITs can integrate quantified ESG scores into NAV calculations, reflecting reduced stranded-asset risk.

- Liquidity: Strong disclosure reduces investment friction and exit yield spreads, aligning with “greenium” trends in sustainable bonds (Partridge & Zheng, 2025).

6.4. Urban Policy and Regeneration

6.5. Theoretical Integration

7. Gaps and Limitations

7.1. Cross-Sectional Design and Endogeneity

7.2. Sample Structure and Statistical Power

7.3. Indicator Construction

7.4. Geographic and Temporal Boundaries

7.5. Econometric Diagnostics

8. Practical Recommendations

8.1. Investors and Asset Managers

- Integrate Tenant ESG Maturity Screening.

- Prioritise Operational over Design Certifications.

- Embed Governance Quality in Valuation Models.

- Mandate Estate-Level Governance Evidence

- Refine ESG Reporting Expectations

8.2. Landlords and Developers

- Enforce Green-Lease Clauses.

- Establish Multi-Stakeholder ESG Committees.

- Adopt PropTech for Real-Time Transparency.

- Design for Dynamic Governance.

- Quantify Governance as Asset Value.

8.3. Lenders and Capital Markets

- Tie Cost of Capital to Verified ESG KPIs.

- Evaluate Tenant ESG Maturity in Underwriting.

- Enhance Transparency Requirements.

- Incorporate ESG Resilience in Stress Testing.

8.4. Policymakers and Regulators

- Expand MEES and “Be Seen” to Tenant Operations

- Harmonise Certification and Disclosure Regimes.

- Incentivize Estate-Level Governance Structures.

- Support Digital Infrastructure for ESG Data.

- Address Social Equity Within ESG Frameworks.

9. Conclusions

9.1. Empirical Insights

9.2. Theoretical Contributions

9.3. Practical and Policy Relevance

9.4. Broader Implications for Urban Sustainability Research

9.5. Pathways for Future Research

- Track estates longitudinally to assess persistence of ESG gains under tenant turnover.

- Compare institutional contexts—Amsterdam, Paris, Singapore—to test governance-convergence generalisability.

- Develop multi-level models linking individual lease arrangements to aggregate estate performance.

- Expand the social pillar with metrics capturing inclusivity, affordability, and community integration.

- Evaluate how digitalised data ecosystems (PropTech, IoT) enable real-time ESG compliance and capital-market verification.

9.6. Closing Synthesis

Compliance with Ethics Standards

Competing Interests

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Abraham, Y.; Greenwood, L.; Andoh, N.-Y.; Schneider, J. Sustainable Building without Certification: An Exploration of Implications and Trends. J. Sustain. Res. 2022, 4, e220007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adindu, C.; Ekung, S.; Ukpong, E. Green cost premium as the dynamics of project management practice: A critical review. J. Proj. Manag. 2022, 7, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ain Farhana Jamaludin, &. M. (2025). The Impact of Environmental, Social and Governance (Esg) on Real Estate Investment: A Bibliometric Review. Pacific Rim Real Estate Society Journal, 30(1).

- Alabid, J.; Bennadji, A.; Seddiki, M. A review on the energy retrofit policies and improvements of the UK existing buildings, challenges and benefits. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, R. Measuring Gentrification and Displacement in Greater London. Urban Stud. 2000, 37, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.-H. Developing ESG Evaluation Guidelines for the Tourism Sector: With a Focus on the Hotel Industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S. A review of tourism and climate change as an evolving knowledge domain. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.; Battisti, G.; Guin, B. The greening of lending: Evidence from banks’ pricing of energy efficiency before climate-related regulation. Econ. Lett. 2023, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasin, M.; Foglie, A.D.; Giacomini, E. Addressing climate challenges through ESG-real estate investment strategies: An asset allocation perspective. Finance Res. Lett. 2024, 63, 105381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, N.; Fotak, V.; Guedhami, O.; Yasuda, Y. The heterogeneous and evolving roles of sovereign wealth funds: Issues, challenges, and research agenda. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2023, 6, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourg-Meyer, V.; Kum, D.; Elias, J.; Uetake, K. (2019). Marina bay sands: Sustainability challenges and opportunities in the events industry. (Y. S. Management, Ed.) Sage Business Cases. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526468130. [CrossRef]

- Bowie, N.E. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art, R. Edward Freeman, Jeffrey S. Harrison, Andrew C. Wicks, Bidhan L. Parmar, and Simone de Colle (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010). Bus. Ethic- Q. 2012, 22, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasch, T.; Eckert, C. Development of the ESG Pillar Scores and Data Availability: Empirical Evidence from the Insurance Industry. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusch, T.S.; Pagan, A.R. A Simple Test for Heteroscedasticity and Random Coefficient Variation. Econometrica 1979, 47, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, S. J. (2016). The evolution of “greener” leasing practices in Australia and England. In Proceedings of COBRA, Sydney, Australia). (p. 4). Sydney: Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS). Retrieved from. [CrossRef]

- Bungau, C.C.; Bungau, T.; Prada, I.F.; Prada, M.F. Green Buildings as a Necessity for Sustainable Environment Development: Dilemmas and Challenges. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R. &. (2000). Compact Cities: Sustainable Urban Forms for Developing Countries. London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203478622. [CrossRef]

- Cajias, M.; Fuerst, F.; McAllister, P.; Nanda, A. DO RESPONSIBLE REAL ESTATE COMPANIES OUTPERFORM THEIR PEERS? Int. J. Strat. Prop. Manag. 2014, 18, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calipha, R.; Katav-Herz, S. (2025). The EU Sustainable Finance Framework. In R. D.-H. Caliphaz, Sustainable Finance Regulation in the European Union. Sustainable Finance. Springer, Cham. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-883. [CrossRef]

- Cesarone, F.; Martino, M.L.; Carleo, A. Does ESG Impact Really Enhance Portfolio Profitability? Sustainability 2022, 14, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Hua, J.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; et al. Green building practices to integrate renewable energy in the construction sector: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 751–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: economic analysis and literature review. Rev. Account. Stud. 2021, 26, 1176–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: economic analysis and literature review. Rev. Account. Stud. 2021, 26, 1176–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condezo-Solano, M.J.; Erazo-Rondinel, A.; Barrozo-Bojorquez, L.M.; Rivera-Nalvarte, C.C.; Giménez, Z. Global Analysis of WELL Certification: Influence, Types of Spaces and Level Achieved. Buildings 2025, 15, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contat, J.; Hopkins, C.; Mejia, L.; Suandi, M. When climate meets real estate: A survey of the literature. Real Estate Econ. 2024, 52, 618–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupland, A. (1997). An introduction to mixed use development. In Reclaiming the City. London: Routledge. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-883. [CrossRef]

- Crevoisier, O.; Theurillat, T.; Rota, M.; Segessemann, A.; Merckhoffer, A. The role of real estate in the development of cities and regions: Territorial real estate and economic systems. Prog. Econ. Geogr. 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosas Armengol, C. G. (2024). From land-use planning to mixed-use configuration: similarities and differences in two urban fragments of Barcelona Metropolis. In XXIX International Seminar on Urban Form: Urban Redevelopment and Revitalisation: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. LódzProceedings book (pp. 200-211). Kraków, Poland: Lodz University of Technology.

- Crosas, C.; Gómez-Escoda, E.; Villavieja, E. Interplay between Land Use Planning and Functional Mix Dimensions: An Assemblage Approach for Metropolitan Barcelona. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawei, Z. &. (2024). The Impact of ESG Factors on Financial Performance: Analyzing the Influence of Sustainability Practices in Chinese Firms. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 14(11), 1649-1652. [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.; Toffel, M.W. Stakeholders and environmental management practices: an institutional framework. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2024, 13, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Toffel, M.W. Organizational responses to environmental demands: opening the black box. Strat. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1027–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Adv. Strateg. Manag. 2004, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dindar, S. A Systematic Review of Urban Regeneration's Impact on Sustainable Transport: Traffic Dynamics, Policy Responses, and Environmental Implications. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, D.; Palka, G.; Hersperger, A.M. Effect of zoning plans on urban land-use change: A multi-scenario simulation for supporting sustainable urban growth. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drempetic, S.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. The Influence of Firm Size on the ESG Score: Corporate Sustainability Ratings Under Review. J. Bus. Ethic- 2020, 167, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichholtz, P.; Holtermans, R.; Kok, N.; Yönder, E. Environmental performance and the cost of debt: Evidence from commercial mortgages and REIT bonds. J. Bank. Finance 2019, 102, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPC. (2025, 10 1). Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. Retrieved from Energy Performance Certificate Register. GOV.UK. : https://www.epcregister.com.

- Espinoza-Zambrano, P. R.-H.-D. (2024). Do green certifications add value? Feedback from high-level stakeholders in the Spanish office market. Journal of Cleaner Production, 144276. [CrossRef]

- Farjam, R.; Motlaq, S.M.H. Does urban mixed use development approach explain spatial analysis of inner city decay? J. Urban Manag. 2019, 8, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst, F.; McAllister, P. The impact of Energy Performance Certificates on the rental and capital values of commercial property assets. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 6608–6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, H. The theory and praxis of mixed-use development - An integrative literature review. Cities 2024, 147, 104774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillingham, K.; Palmer, K. Bridging the Energy Efficiency Gap: Policy Insights from Economic Theory and Empirical Evidence. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2014, 8, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Gottlieb, J.D. The Wealth of Cities: Agglomeration Economies and Spatial Equilibrium in the United States. J. Econ. Lit. 2009, 47, 983–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomide, F.P.d.B.; Bragança, L.; Junior, E.F.C. How Can the Circular Economy Contribute to Resolving Social Housing Challenges? Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Ejohwomu, O.A.; Shen, F.; Aye, L.; Aminian, E.; Abadi, M. Energy performance gap in zero-energy buildings: A socio-technical complexity framework for risk assessment and mitigation. Environ. Challenges 2025, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, S.; V. , S.; N., E. ESG or financial metrics? What retail investors really look for in decision-making. Invest. Manag. Financial Innov. 2025, 22, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourabpasi, A.H.; Jalaei, F.; Ghobadi, M. Developing an openBIM Information Delivery Specifications Framework for Operational Carbon Impact Assessment of Building Projects. Sustainability 2025, 17, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.; Buizer, M.; Buijs, A.; Pauleit, S.; Mattijssen, T.; Fors, H.; van der Jagt, A.; Kabisch, N.; Cook, M.; Delshammar, T.; et al. Transformative or piecemeal? Changes in green space planning and governance in eleven European cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 2401–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirigoyen, Julie. (2014). UK Green Building Council. Retrieved from UKGBC: https://ukgbc.org/resources/impact-report-2018-19/.

- Holt, A.D.; Giordano, J.A.; White, N. The evolution of accounting practices for UK commercial service charges: evaluating the impact of the RICS professional standard. J. Corp. Real Estate 2025, 27, 130–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppenbrouwer, E.; Louw, E. Mixed-use development: Theory and practice in Amsterdam's Eastern Docklands. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2005, 13, 967–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Bai, F.; Shang, M.; Ahmad, M. On the fast track: the benefits of ESG performance on the commercial credit financing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 83961–83974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwuanyanwu, O.; Gil-Ozoudeh, I.; Okwandu, A.C.; Ike, C.S. THE ECONOMIC BENEFITS OF GREEN BUILDINGS: A COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF SUSTAINABLE ARCHITECTURE. Int. J. Adv. Econ. 2023, 5, 374–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamei, E.; Ahmadi, K.; Chau, H.W.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Horan, B.; Stojcevski, A. Urban Design and Walkability: Lessons Learnt from Iranian Traditional Cities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, K.B.; Bright, S.; Patrick, J.; Wilkinson, S.; Dixon, T.J. The evolution of green leases: towards inter-organizational environmental governance. Build. Res. Inf. 2016, 44, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukić, T.; Watson, G.B. (2019). Reuse and revitalisation of contemporary city areas: structural and functional transformation of brownfield sites. In M. B. Obad Šćitaroci, Cultural Urban Heritage. The Urban Book Series (pp. 245–261). Springer, Cham. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-10612-6_18. [CrossRef]

- Kempeneer, S.; Peeters, M.; Compernolle, T. Bringing the User Back in the Building: An Analysis of ESG in Real Estate and a Behavioral Framework to Guide Future Research. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Barles, S. The energy consumption of Paris and its supply areas from the eighteenth century to the present. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2012, 12, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledgerwood, G.; Haywood, I.; Sheppard, N.; Street, E. Environmental assessment as a real estate management protocol. Cities 1994, 11, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. R. (2024). Code for JUE paper Agglomeration Economies and the Built Environment: Evidence from Specialized Buildings and Anchor Tenants. Mendeley Data, 1. [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, B.; Hutchison, N. Tenants’ ESG: influence on preferences and rent premiums for green buildings in commercial real estate. J. Prop. Res. 2025, 42, 321–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Sandanayake, M.; Miao, P.; Shi, Y.; Yap, P.-S. Sustainability Considerations of Green Buildings: A Detailed Overview on Current Advancements and Future Considerations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D.; Lützkendorf, T. Sustainability and property valuation. J. Prop. Invest. Finance 2011, 29, 644–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, P.; Nase, I. The impact of Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards: Some evidence from the London office market. Energy Policy 2019, 132, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, P.; Dowling, R. Urban governance dispositifs: cohering diverse ecologies of urban energy governance. Environ. Plan. C: Politi- Space 2020, 39, 759–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, C.S.; Kumar, A.; Jain, S.; Rehman, A.U.; Mishra, S.; Sharma, N.K.; Bajaj, M.; Shafiq, M.; Eldin, E.T. Innovation in Green Building Sector for Sustainable Future. Energies 2022, 15, 6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaxas, T.; Juarez, L.; Gavriilidis, G. Planning and Marketing the City for Sustainability: The Madrid Nuevo Norte Project. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, G. Future research opportunities for Asian real estate. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2019, 25, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, G. Real Estate Insights The increasing importance of the “S” dimension in ESG. J. Prop. Invest. Finance 2023, 41, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuriani, N.; Oldfield, P.; Prasad, D.; Thomas, P. Minimising the energy performance gap in Australia’s commercial buildings: Energy modelling practice, process, and performance. Energy Build. 2025, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, C.; Medda, F.R. Green Bond Pricing: The Search for Greenium. J. Altern. Investments 2020, 23, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Zapata-Lancaster, G. Integrating views on building performance from different stakeholder groups. J. Corp. Real Estate 2023, 26, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przychodzen, J.; Gómez-Bezares, F.; Przychodzen, W.; Larreina, M. ESG Issues among Fund Managers—Factors and Motives. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puggioni, F.; Tontisirin, N. Mixed-use Developments and Urban Megaprojects in the Global South: A Systematic Review and Interpretation of a Blurred Intersection. Nakhara : J. Environ. Des. Plan. 2025, 24, 508–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.; McIntosh, M.G. A Literature Review of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) in Commercial Real Estate. J. Real Estate Lit. 2022, 30, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, N.; Vale, M.; Costa, P. Urban experimentation and smart cities: a Foucauldian and autonomist approach. Territ. Politi- Gov. 2020, 10, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S.S.; Strange, W.C. How Close Is Close? The Spatial Reach of Agglomeration Economies. J. Econ. Perspect. 2020, 34, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, Z.M.; Dindar, S. Key Challenges and Strategies in the Evaluation of Sustainable Urban Regeneration Projects: Insights from a Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweber, L. The effect of BREEAM on clients and construction professionals. Build. Res. Inf. 2013, 41, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scofield, J.H. Efficacy of LEED-certification in reducing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emission for large New York City office buildings. Energy Build. 2013, 67, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, A.M. Environment, social, and governance (ESG) criteria and preference of managers. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.; Burman, E.; Mumovic, D.; Davies, M. Managing the risk of the energy performance gap in non-domestic buildings. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2021, 43, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dronkelaar, C.; Dowson, M.; Burman, E.; Spataru, C.; Mumovic, D. A Review of the Regulatory Energy Performance Gap and Its Underlying Causes in Non-domestic Buildings. Front. Mech. Eng. 2016, 1, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voland, N.; Saad, M.M.; Eicker, U. Public Policy and Incentives for Socially Responsible New Business Models in Market-Driven Real Estate to Build Green Projects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Z. Research on sustainability evaluation of green building engineering based on artificial intelligence and energy consumption. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 11378–11391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebardast, E. (2017). Exploratory Factor Analysis in Urban and Regional Planning. Journal of Fine Arts: Architecture & Urban Planning, 22(2), 5-18. [CrossRef]

- Zehner, J. (2021). The Impact of Environmental Certificates on Office Prices in London. University College London. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3943976. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-N.; Wei, S.-Y. A comparative study on the spatial vitality of national squares: A visualization analysis based on multi-source data. Front. Arch. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Aziz, F.A.; Deng, Y.; Ujang, N.; Xiao, Y. A Review of Comprehensive Post-Occupancy Evaluation Feedback on Occupant-Centric Thermal Comfort and Building Energy Efficiency. Buildings 2024, 14, 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Lee, C.L. A meta-analysis of ESG factors in the real estate investment trusts sector: exploring their impacts on REITs performance. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. [CrossRef]

| Variable Group | Source(s) | Proxy Logic / Notes |

| Anchor Typology | Press releases, leasing announcements, developer/investor websites | Dominant GLA, investment draw, or branding |

| ESG Certifications | BRE BREEAM directory, UK Govt EPC Register, asset manager disclosures | Asset-level records, proxy from similar assets |

| Governance Maturity | Sustainability reports, TCFD, analyst briefings, BBP, JLL, CBRE market research | High/medium/low scale by reporting transparency |

| Control Variables | Developer reports, planning documents, GLA, zone, year, public realm provision | Where missing, triangulated from comparables |

| Dimension | Indicator | Scale & Rule | Rationale |

| Environmental | BREEAM | 1–4 by grading | Cert uptake, reg. compliance, tenant-driven demand |

| Environmental | EPC | A–G mapped 0–4 | Mandatory, but imperfect, regulatory measure |

| Social | Public Realm | None–High 0–4 | Urban placemaking, accessibility |

| Social | Transport | None–High 0–4 | Mobility, connectedness, estate externality |

| Governance | Green Lease | None–Conf 0–4 | Direct evidence/presumptive via anchor maturity |

| Governance | ESG Maturity | Low–High 0–4 | Disclosure, engagement, sustainability targets |

| Type | Anchor Comparison | ESG Dimension | Expected Outcome |

| H1 (Formal) | Office vs Residential | ESG composite (0–100) | ↑ Higher for Office |

| H2 (Exploratory) | All typologies | Governance (ESG maturity) | Positive moderation |

| H3 (Exploratory) | All typologies | Social vs Environmental | Greater Social variation |

| Anchor Type | n | Mean ESG | SD ESG | Mean E | Mean S | Mean G |

| Office | 30 | 74.42 | 11.25 | 2.93 | 3.10 | 2.90 |

| Residential | 30 | 68.08 | 11.56 | 2.70 | 2.93 | 2.47 |

| Retail | 3 | 73.75 | 6.61 | 2.50 | 3.67 | 3.00 |

| Hotel | 2 | 58.75 | 22.98 | 2.00 | 3.50 | 1.50 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).