Submitted:

14 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

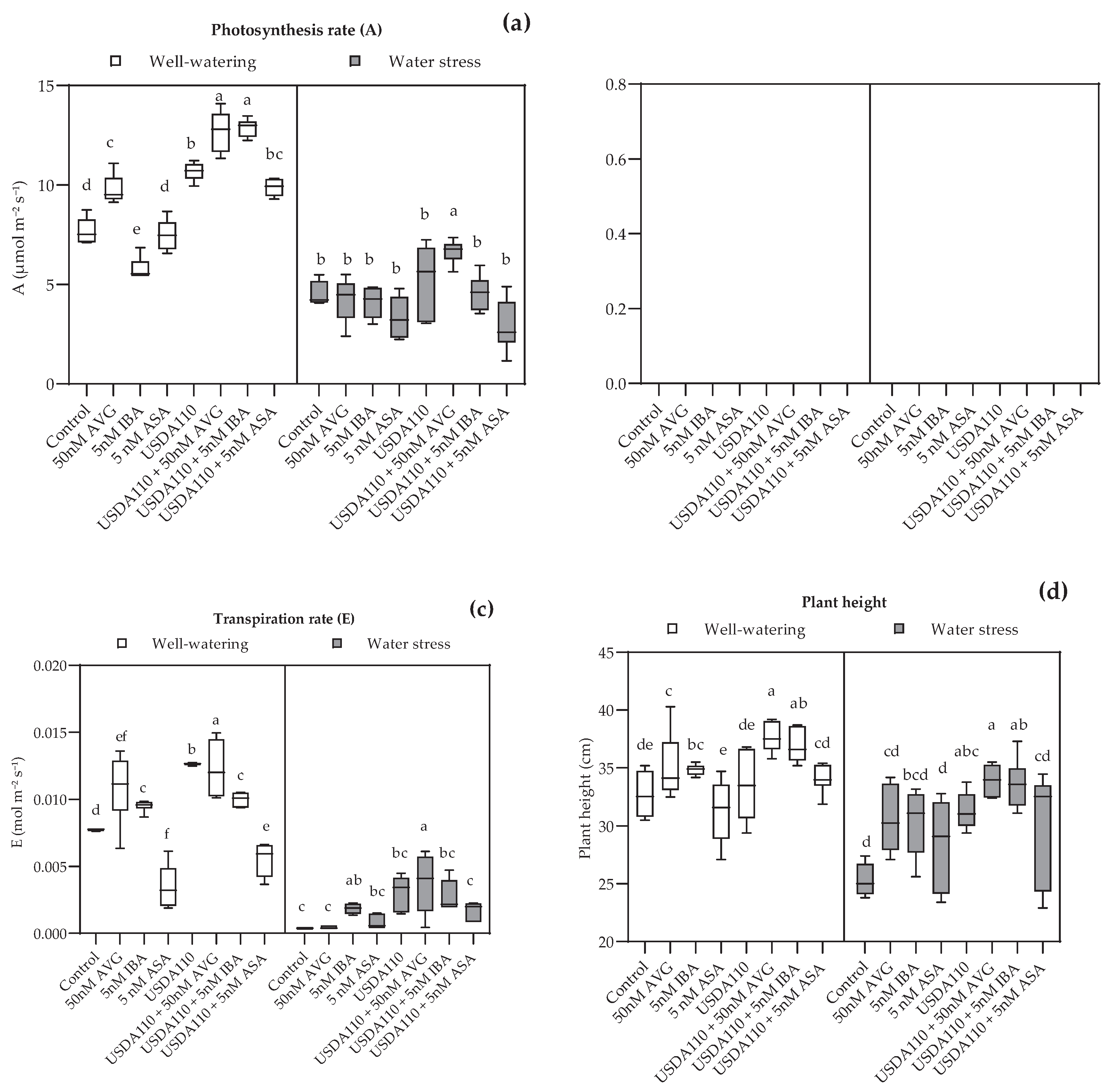

Soybean (Glycine max) is a globally important crop, but its productivity is often limited by suboptimal nodulation and nitrogen fixation, particularly under stress conditions. Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens strain USDA110 is widely applied to enhance nodulation, yet its efficiency can be further improved by phytohormone modulation. This study examined the effects of seed coatings containing plant growth regulators (PGRs)—acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG), indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), and 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP)—at varying concentrations from 5 – 500 nM, in combination with USDA110, on nodulation, nitrogenase activity, ethylene emission, physiological traits, and yield of soybean cultivar CM60. Laboratory assays identified 50 nM AVG, 5 nM IBA, and 5 nM ASA as optimal treatments, significantly enhancing nodule number and nitrogenase activity. Greenhouse trials under both well-watered and water-deficit conditions further demonstrated that USDA110 combined with AVG or IBA markedly improved photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, transpiration, plant height, and yield components compared with USDA110 or PGRs applied alone. Notably, USDA110 + AVG/IBA treatments sustained higher seed weight under drought, indicating strong synergistic effects in mitigating stress impacts. These findings highlighted that integrating USDA110 with specific PGRs represented a promising strategy to optimize nitrogen fixation and enhanced soybean productivity under both favorable and challenging conditions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Bradyrhizobium and PGRs Inoculant

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Screening of Plant Growth Regulators’ Concentrations Affecting Nitrogenase Activity and Nodule Numbers in Soybean Roots

2.3.2. Plant Growth Regulators’ Effects on Physiological Parameters, Yield, and Yield Components of Soybean in Greenhouse Condition

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

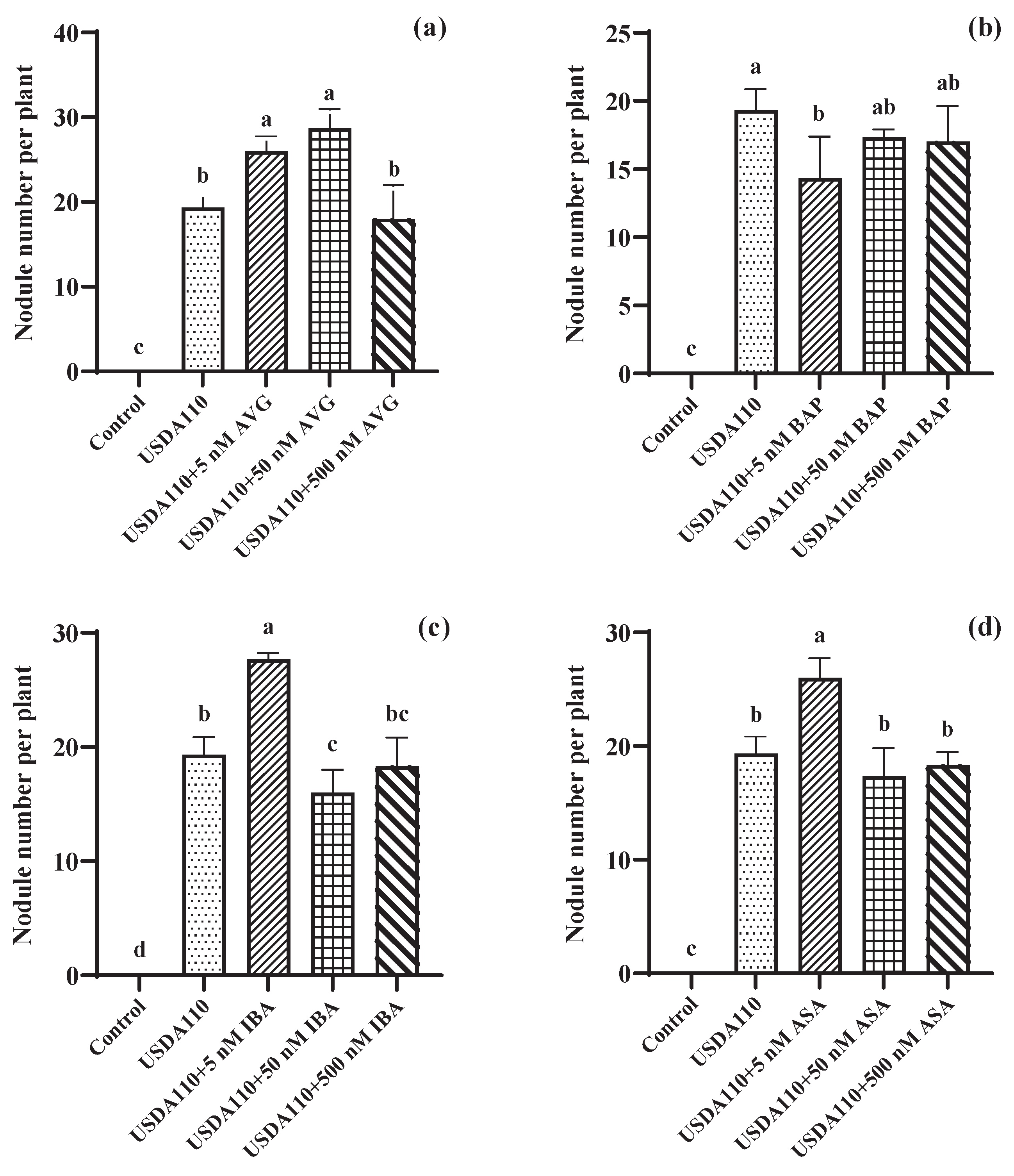

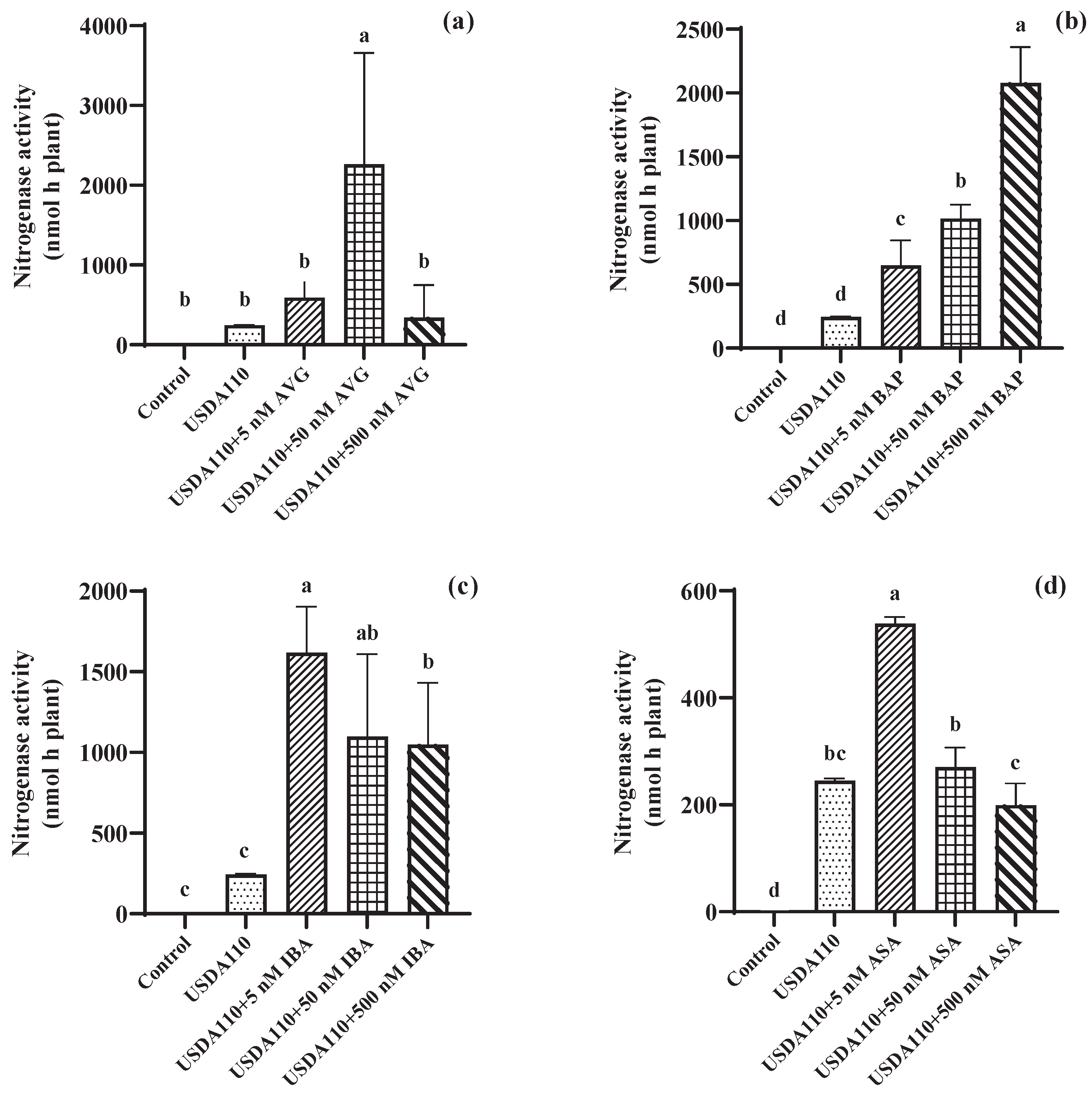

3.1. Effects of Seed Coating Plant Growth Regulators on Nitrogenase Activity and Nodule Numbers in Soybean Roots

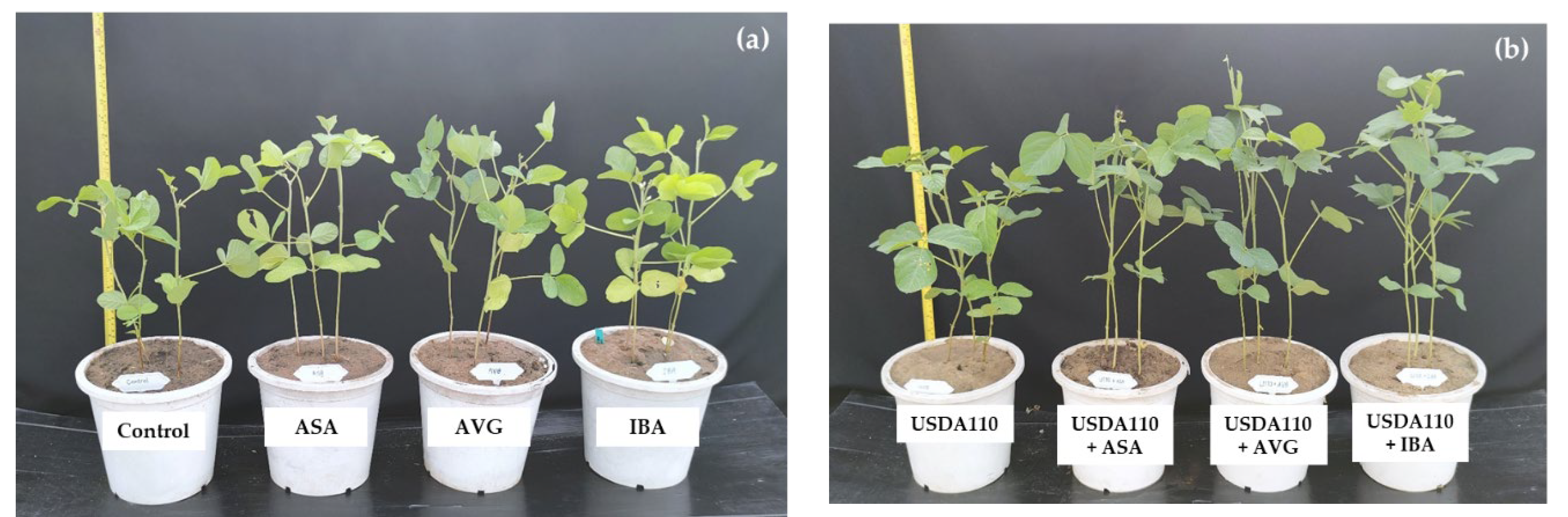

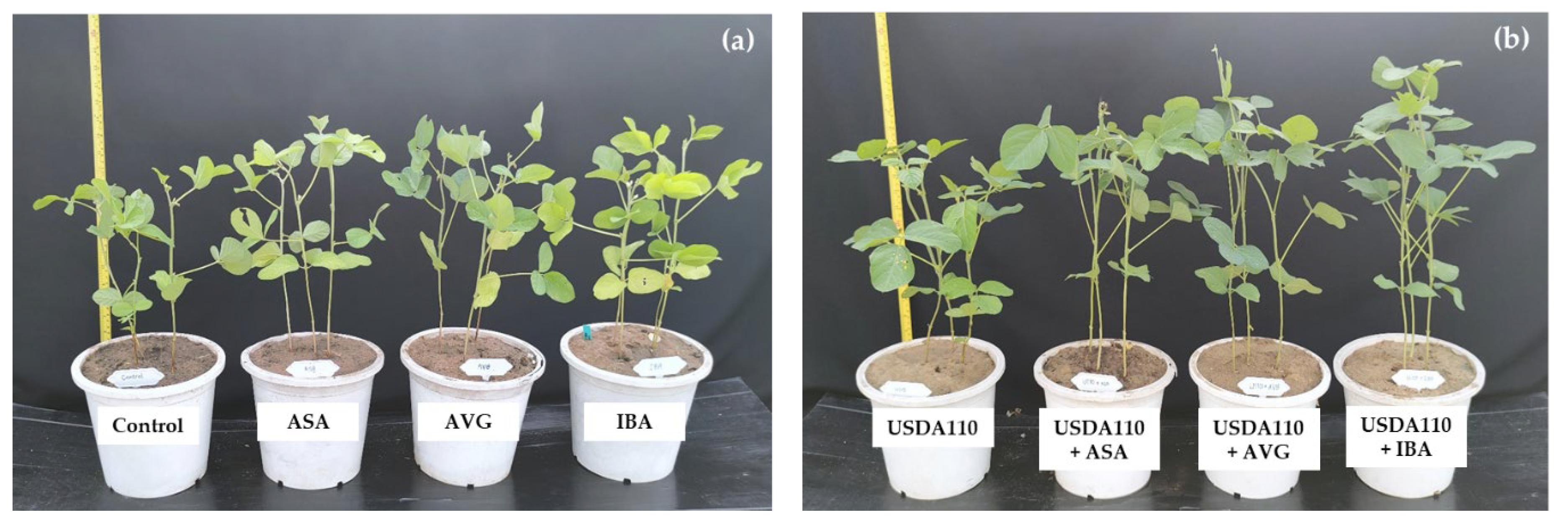

3.2. Effects of Plant Growth Regulators on Physiological Parameters, Yield, and Yield Components of Soybean in Greenhouse Condition

3.2.1. Physiological Parameters

3.2.2. Yield and Yield Components

4. Discussions

4.1. Effects of Seed Coating Plant Growth Regulators on Nitrogenase Activity and Nodule Numbers in Soybean Roots

4.2. Effects of Plant Growth Regulators on Physiological Parameters, Yield, and Yield Components of Soybean in Greenhouse Condition

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EMR. (2024). Global soybean market growth, analysis, trends, forecast (pp. 1–16).

- Srinives, P.; Somta, P. Present status and future perspectives of Glycine and Vigna in Thailand. In The 14th NIAS international workshop on genetic resources–Genetic resources and comparative genomics of legumes (Glycine and Vigna). 2011, 63–68. National Institute of Agrobiological Science.

- Cerezini, P.; Oliveira, A.F.M.D.; Nogueira, M.A.; Hungria, M. Strategies to promote early nodulation in soybean under drought. Field Crops Research 2016, 196, 160–167. [CrossRef]

- Kunert, K.J.; Wilson, C.D.; Fuhrmann, M. Drought stress responses in soybean roots and nodules. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Miljaković, D.; Marinković, J.; Ignjatov, M.; Milosević, D.; Nikolić, Z.; Tintor, B.; Đukić, V. Competitiveness of Bradyrhizobium japonicum inoculation strain for soybean nodule occupancy. Plant, Soil and Environment 2022, 68(1), 59–64. [CrossRef]

- Miljaković, D.; Marinković, J.; Tamindžić, G.; Đorđević, V.; Tintor, B.; Milošević, D.; Nikolić, V.; Nikolić, Z. Bio-priming of soybean with Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Bacillus megaterium: Strategy to improve seed germination and the initial seedling growth. Plants 2022, 11(15), 1927. [CrossRef]

- Szpunar-Krok, E.; Bobrecka-Jamro, D.; Pikuła, W.; Jańczak-Pieniążek, M. Effect of nitrogen fertilization and inoculation with Bradyrhizobium japonicum on nodulation and yielding of soybean. Agronomy 2023, 13(5), 1341. [CrossRef]

- Gebrehana, Z.G.; Dagnaw, L.A. Response of soybean to rhizobial inoculation and starter N fertilizer on Nitisols of Assosa and Begi areas, Western Ethiopia. Environmental Systems Research 2020, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Frank, M.; Reid, D. (2020). No home without hormones: How plant hormones control legume nodule organogenesis. Plant Communications 2020, 1(5), 100104. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Guo, H.J.; Wang, R.; Sui, X.H.; Zhang, Y.M.; Wang, E.T.; Tian C.F.; Chen, W.X. Genetic divergence of Bradyrhizobium strains nodulating soybeans as revealed by multilocus sequence analysis of genes inside and outside the symbiosis island. Applied and environmental microbiology 2014, 80(10), 3181-3190. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Sato, S.; Minamisawa, K.; Uchiumi, T.; Sasamoto, S.; Watanabe, A.; Idesawa, K., Iriguchi, M., Kawashima, K.; Kohaea, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Shimpo, S.; Tsuruoka, K.; Wada, T.; Yamada, M.; Tabata, S. Complete Genomic Sequence of Nitrogen-fixing Symbiotic Bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110. DNA Research 2002, 9(6), 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.R.; Johns, S.M.; Pandey, S. A convenient, soil-free method for the production of root nodules in soybean to study the effects of exogenous additives. Plant Direct 2019, 3(4), e00135. [CrossRef]

- Kempster, R.; Barat, M.; Bishop, L.; Rufino, M.; Borras, L.; Dodd, I.C. Genotype and cytokinin effects on soybean yield and biological nitrogen fixation across soil temperatures. Annals of Applied Biology 2020, 178(2), 341–354. [CrossRef]

- Kitaeva, A.B.; Serova, T.A.; Kusakin, P.G.; Tsyganov, V.E. Effects of elevated temperature on Pisum Sativum nodule development: II—Phytohormonal responses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(23), 17062. [CrossRef]

- Hasibuan, R.F.M.; Miyatake, M.; Sugiura, H.; Agake, S.I.; Yokoyama, T.; Bellingrath-Kimura, S.D.; Katsura, K.; Ohkama-Ohtsu, N. Application of biofertilizer containing Bacillus pumillus TUAT1 on soybean without inhibiting infection by Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens USDA110. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2021, 67(5), 535–539. [CrossRef]

- Zadegan, S.B.; Kim, W.; Abbas, H.M.K.; Kim, S.; Krishnan, H.B.; Hewezi, T. Differential symbiotic compatibilities between rhizobium strains and cultivated and wild soybeans revealed by anatomical and transcriptome analyses. Frontiers in Plant Science 2024, 15, 1435632. [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, G.; Wijayasinghe, M.; Yapa, N. Evaluation of potential seed coating formulation with Bradyrhizobium japonicum on soybean (Glycine max L.) seeds. Vingnanam Journal of Science 2024, 19(2).

- Souza, M.C.; Chagas, L.F.B.; Martins, A.L.L.; Lima, C.A.; de Oliveira Moura, D.M.; Lopes, M.B.; Leite, A.S.D.F.; Junior, A.F.C. Biopolymers in the preservation of rhizobacteria cells and efficiency in soybean inoculation. Research, Society and Development 2022, 11(7), e21911729688.

- Liu, R.; Yan, X.; Liu, R.; Wu, Q.; Gao, Y.; Muhindo, E.M.; Zhi, Z.; Wu, T.; Sui, W.; Zhang, M. Lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus Linn.) protein isolate as a promising plant protein mixed with xanthan gum for stabilizing oil-in-water emulsions. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2024, 104(2), 818–828. [CrossRef]

- Baldani, J.I.; Reis, V.M.; Videira, S.S.; Boddey, L.H.; Baldani, V.L.D. The art of isolating nitrogen-fixing bacteria from non-leguminous plants using N-free semi-solid media: a practical guide for microbiologists. Plant and Soil 2014, 384, 413–431. [CrossRef]

- Lindström, K.; Mousavi, S.A. Effectiveness of nitrogen fixation in rhizobia. Microbial biotechnology 2020, 13(5), 1314-1335. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Daoust, F.; Charles, T.C.; Driscoll, B.T.; Prithiviraj, B.; Smith, D.L. Bradyrhizobium japonicum mutants allowing improved nodulation and nitrogen fixation of field-grown soybean in a short season area. The Journal of Agricultural Science 2002, 138(3), 293-300. [CrossRef]

- Guinel, F.C. Ethylene, a hormone at the center-stage of nodulation. Frontiers in Plant Science 2015, 6, 1121. [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Sharma, M.; Singh, R.; Gupta, S. Auxins and nodulation in legume roots: complex signaling pathways. Plant Growth Regulation 2013, 70(2), 89–100.

- Liu, J.; Hu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F. (2011). Cytokinin regulation of soybean nodulation is independent of ethylene signaling. Plant Science 2011, 180(2), 481–490.

- Hegazi, A.M.; El-Shraiy, A.M. Impact of salicylic acid and paclobutrazol exogenous application on the growth, yield and nodule formation of common bean. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2007, 1(4), 834–840.

- Kuchlan, P.; Kuchlan, M.K. Effect of salicylic acid on plant physiological and yield traits of soybean. Legume Research-An International Journal 2023, 46(1), 56–61.

- van Spronsen, P.C.; Tak, T.; Rood, A.M.; van Brussel, A.A.; Kijne, J.W.; Boot, K.J. Salicylic acid inhibits indeterminate-type nodulation but not determinate-type nodulation. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2003, 16(1), 83–91. [CrossRef]

- Senaratna, T.; Touchell, D.; Bunn, E.; Dixon, K. Acetyl salicylic acid (Aspirin) and salicylic acid induce multiple stress tolerance in bean and tomato plants. Plant Growth Regulation 2000, 30(2), 157–161. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, R.; Ranjithakumari, B.D. Callus induction and plant regeneration of Indian soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr. cv. CO3) via half seed explant culture. Journal of Agricultural Technology 2007, 3(2), 287–297.

- Rathod, B.U.; Dattagonde, N.R.; Jadhav, M.P.; Behre, P.P. Effect of different growth regulators on soybean (Glycine max L.) regeneration. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci 2017, 6(11), 2726–2731. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Suh, S.K.; Park, H.K.; Wood, A. Impact of 2, 4-DP and BAP upon pod set and seed yield in soybean treated at reproductive stages. Plant Growth Regulation 2002, 36(3), 215–221. [CrossRef]

- van Spronsen, P.C.; Grønlund, M.; Bras, C.P.; Spaink, H.P.; Kijne, J.W. Cell biological changes of outer cortical root cells in early determinate nodulation. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2001, 14(7), 839–847. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhong, X.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, W.; Wang, W.; Gu, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Kiu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, J. Exogenous spermidine and amino-ethoxyvinylglycine improve nutritional quality via increasing amino acids in rice grains. Plants 2024, 13(2), 316. [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, S.; Merritt, D.J.; Stevens, J.; Dixon, K. Seed coating: science or marketing spin?. Trends in plant science 2017, 22(2), 106-116. [CrossRef]

- Patyal, D.; Sachdeva, K.; Sharma, K.; Khan, R.R. An innovative and sustainable seed coating technology for improving seed quality and crop performance. Journal of Scientific Research and Reports 2025, 597–607.

- Sheteiwy, M.S.; Ali, D.F.I.; Xiong, Y.C.; Brestic, M.; Skalicky, M.; Hamoud, Y.A.; Ulhassan, Z.; Shaghaleh, H.; AbdElgawad, H.; Farooq, M; Sharma, A.; Sl-Sawah, A.M. Physiological and biochemical responses of soybean plants inoculated with Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Bradyrhizobium under drought stress. BMC Plant Biology 2021, 21(1), 195. [CrossRef]

- Jarecki, W. Physiological response of soybean plants to seed coating and inoculation under pot experiment conditions. Agronomy 2022, 12(5), 1095. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, I.; Ma, Y.; Souza-Alonso, P.; Vosátka, M.; Freitas, H.; Oliveira, R.S. Seed coating: a tool for delivering beneficial microbes to agricultural crops. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 1357. [CrossRef]

- Halmer, P. Seed technology and seed enhancement. In P. Halmer (Ed.), XXVII International Horticultural Congress-IHC2006: International Symposium on Seed Enhancement and Seedling Production 2006 (771, pp. 17–26). International Society for Horticultural Science.

- Chen, L.; Yang, W.; Zhang, H. Effect of Aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG) on soybean nodulation and root development under different water regimes. Journal of Plant Physiology 2020, 244, 153–162.

- Cheng, C.; Zhang, H.; Yang, H. Interaction between plant growth regulators and Bradyrhizobium strains on soybean performance. Plant and Soil 2022, 470(1), 191–204.

- Wang, X.; Wen, H.; Suprun, A.; Zhu, H. Ethylene signaling in regulating plant growth, development, and stress responses. Plants 2025, 14(3), 309. [CrossRef]

- Broekaert, W.F.; Delauré, S.L.; De Bolle, M.F.; Cammue, B.P. The role of ethylene in host-pathogen interactions. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2006, 44(1), 393–416. [CrossRef]

- Ecker, J.R.; Davis, R.W. Plant defense genes are regulated by ethylene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1987, 84(15), 5202–5206. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, F.X.; Rossi, M.J.; Glick, B.R. Ethylene and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) in plant–bacterial interactions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 9, 114. [CrossRef]

- Schaller, G.E.; Binder, B.M. Inhibitors of ethylene biosynthesis and signaling. Ethylene Signaling: Methods and Protocols 2017, 223–235. [CrossRef]

- McBride, S.; Errickson, W.; Huang, B. Effects of chemical and biological inhibitors of ethylene on heat tolerance in annual bluegrass. HortScience 2025, 60(3), 310-316. [CrossRef]

- Najeeb, U.; Atwell, B.J.; Bange, M.P.; Tan, D.K. Aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG) ameliorates waterlogging-induced damage in cotton by inhibiting ethylene synthesis and sustaining photosynthetic capacity. Plant Growth Regulation 2015, 76(1), 83-98. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Gen, W.; Cheng, Y. The effects of ethylene on the HCl-extractability of trace elements during soybean seed germination. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology 2015, 18(5), 333-337. [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.; Liu, H.; Jiang, C. Ethylene inhibition and nodulation enhancement in soybean by Aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG) and its interaction with Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 2021, 40(3), 1223–1233.

- Khalid, A.; Ahmad, Z.; Mahmood, S.; Mahmood, T.; Imran, M. Role of ethylene and bacterial ACC-deaminase in nodulation of legumes. In Microbes for Legume Improvement 2017, pp. 95–118. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Frick, E.M.; Strader, L.C. Roles for IBA-derived auxin in plant development. Journal of Experimental Botany 2018, 69(2), 169–177. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Zuo, Y.; Zhu, L.; Hastwell, A.H.; Chen, L.; Tian, Y., Su, C.; Ferguson, B.J.; Li, X. GmYUC2a mediates auxin biosynthesis during root development and nodulation in soybean. Journal of Experimental Botany 2019, 70(12), 3165–3176. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Ali, S.; Noor, M. Role of plant growth regulators in enhancing soybean yield and yield stability under water stress. Plant Growth Regulation 2022, 94(3), 489–501.

- Gao, Z.P.; Gu, W.C.; Li, J.; Qiu, Q.T.; Ma, B.G. Independent component analysis reveals the transcriptional regulatory modules in Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens USDA110. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24(16), 12544. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, A.K.; Brown, M.R.; Subramanian, S.; Brözel, V.S. Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens USDA110 displays plasticity in the attachment phenotype when grown in different soybean root exudate compounds. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1190396. [CrossRef]

| Conditions | Treatments | Dry weight per plant (g) | Nodule number per plant | Pod number per plant | 100 seed weight (g) | Seed weight per plant (g) |

| Well-watering | Control | 1.18±0.17c | 0.00±0.00c | 10.11±1.02abc | 2.53±0.19bcd | 6.12±0.39c |

| 5nM IBA | 1.26±0.16c | 0.00±0.00c | 7.67±0.37c | 1.77±0.17d | 6.34±0.39c | |

| 50nM AVG | 1.53±0.12c | 0.00±0.00c | 9.11±0.56bc | 2.03±0.17cd | 6.51±0.11bc | |

| 5nM ASA | 1.41±0.17c | 0.00±0.00c | 8.56±1.00bc | 2.05±0.13cd | 6.56±0.21bc | |

| USDA110 | 2.54±0.20b | 10.33±0.50b | 13.56±0.56a | 3.34±0.18a | 8.06±0.17a | |

| USDA110 + 5nM IBA | 3.57±0.29a | 12.78±0.86a | 11.67±0.50ab | 2.70±0.13abc | 8.41±0.10a | |

| USDA110 + 50nM AVG | 2.54±0.10b | 13.33±0.53a | 12.00±1.11ab | 3.24±0.25ab | 8.24±0.19a | |

| USDA110 + 5nM ASA | 2.50±0.15b | 9.44±0.41b | 11.44±1.06ab | 2.57±0.14abc | 7.43±0.13ab | |

| Sig | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | |

| %CV | 26.09 | 22.20 | 23.43 | 20.83 | 9.88 | |

| Water stress | Control | 0.75±0.04d | 0.00±0.00c | 5.56±0.29bc | 1.08±0.64b | 4.15±0.13cd |

| 5nM IBA | 0.87±0.10cd | 0.00±0.00c | 4.67±0.33c | 1.05±0.06b | 3.45±0.13d | |

| 50nM AVG | 1.36±0.20bc | 0.00±0.00c | 6.11±0.39abc | 1.46±0.12ab | 4.49±0.10c | |

| 5nM ASA | 0.85±0.08cd | 0.00±0.00c | 5.63±0.38bc | 1.33±0.12ab | 3.90±0.25cd | |

| USDA110 | 0.89±0.10cd | 5.78±0.22b | 5.89±0.66bc | 1.58±0.21ab | 5.60±0.12b | |

| USDA110 + 5nM IBA | 2.05±0.15a | 7.33±0.29a | 7.67±0.37a | 1.88±0.13a | 5.73±0.18b | |

| USDA110 + 50nM AVG | 1.91±0.12ab | 7.11±0.31a | 6.44±0.34ab | 1.66±0.11a | 7.55±0.20a | |

| USDA110 + 5nM ASA | 2.04±0.18a | 6.00±0.24b | 4.89±0.31bc | 1.35±0.11ab | 5.48±0.19b | |

| Sig | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | 0.000** | |

| %CV | 29.20 | 16.99 | 20.39 | 25.72 | 10.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).