Introduction

The question of what language the brain uses to think has long been a matter of philosophical and scientific debate (Fedorenko and Varley 2016; Martín-Iglesias and Flórez 2018; Frankland and Greene 2020; Fedorenko, Piantadosi and Gibson 2024; Mahowald et al. 2024). Competing hypotheses have framed thought as a symbolic inner code (Mentalese) resembling logic (Fodor 1975), as patterns of neural activity encoded in spikes, rates or oscillations, as predictive models continually updated to minimize error (Friston 2010) or as processes grounded in bodily and sensorimotor experience (Barsalou 2008). These approaches have shaped modern cognitive science, yet they often emphasize propositional, mechanistic or code-like structures at the expense of more flexible and symbolic modes of thought.

An alternative possibility has received less systematic attention: the idea that thought may be organized in a poetic mode. By poetic we mean a constellation of features (e.g., metaphor, rhythm, repetition, imagery, ambiguity, sound play, emotional resonance and collective synchrony) that characterize not only literary works but also fundamental cognitive processes (Jakobson 1960; Wimsatt and Beardsley 1954; Lotman 1977; Tsur 1992; Hogan 2011; Obermeier et al. 2013a; Ob ermeier et al., 2013b; Jacobs 2015). Several cues point towards the possibility that the brain may employ a poetic language. In cognitive linguistics, Lakoff and Johnson (1980) argued that metaphor forms the scaffolding of abstract reasoning. Cognitive poetics has further developed the relationship between poetic structures and cognition (Tsur 2008; Steen 2014), while Jacobs’ (2015) neurocognitive poetics model has shown how literary reading recruits circuits that integrate emotion, imagery and meaning. Neuroimaging reveals that poetry engages broader cortical and limbic networks than prose, with measurable effects on memory and emotion (Wassiliwizky et al. 2017).

Anthropological evidence adds a further dimension: rhythmic chant, song and poetic parallelism are ubiquitous across early human societies, suggesting that poetic structures are older and more essential than the prose-like logic later emphasized in science and philosophy (Fabb 2015). Extending this view beyond humans, animal communication exhibits proto-poetic features. Birdsong, whale song, primate calls, the honeybee’s dance and ritualized displays such as the peacock’s tail all reveal rhythmic structuring, repetition with variation, symbolic cues and affective resonance.

Together, these findings raise the provocative possibility that poetry is not a cultural luxury but a natural cognitive technology, embedded in neural architecture and shaped by evolutionary pressures. This review synthesizes evidence across neuroscience, linguistics, literary theory and animal communication to ask whether humans and perhaps animals, think in poetic language.

Defining Poetic Language

Poetic language differs from ordinary discourse because it is built not merely to convey information, but to transform it into forms that resonate, endure and connect. Where literal language strives for precision and univocal clarity, poetic language embraces pattern, association and multiplicity. It is distinguished by a constellation of features that, taken together, give it a unique capacity to shape thought and expression.

Metaphor and analogy form the foundation of poetic language. Through them, abstract ideas are understood in terms of concrete experiences, allowing new insights to emerge from cross-domain associations. Life becomes a journey, emotion becomes fire, time becomes a river. These metaphors are not only stylistic embellishments but ways of reordering experience, making the unfamiliar intelligible by framing it in terms of what is already known. Analogy, similarly, bridges disparate realms, inviting recognition of hidden similarities and sparking new conceptual structures.

Rhythm and repetition provide a second defining feature. Poetic language is rarely neutral in its flow; it is structured into beats, pulses and returns. Rhythm captures attention, establishes expectation and guides reception. Repetition, whether of sounds, words, phrases or structures, reinforces memory, lends emphasis and generates cohesion. Parallelism, a special case of repetition, creates balance and symmetry, making ideas more memorable and aesthetically satisfying. Together, rhythm and repetition transform language into patterned experience.

Imagery and symbolism lend poetry its density. Images summon sensory detail, evoking sight, sound, touch and movement with a few words. They compress meaning, allowing multiple associations to cluster around a single image. Symbols extend this compression, turning concrete objects into carriers of layered significance: a rose for love, a road for choice, a shadow for mortality. Through imagery and symbolism, poetry achieves richness that ordinary description cannot.

Ambiguity and polysemy distinguish poetic from prosaic communication. Where ordinary discourse tends toward resolution, poetry often resists closure, holding open several meanings at once. A line may suggest one thing and its opposite or hover between interpretations and this openness is part of its force. Ambiguity compels the reader or listener to dwell in uncertainty, encouraging reflection and multiple perspectives. Polysemy, the coexistence of several meanings in a single word or phrase, multiplies resonance and depth.

Sound play is another essential dimension. Rhyme, alliteration, assonance and onomatopoeia exploit the acoustic properties of language, creating echoes, harmonies and textures that delight the ear and reinforce structure. Poetic language is thus memorable not only for its meaning but for its music. Its patterns of sound contribute to its rhythm and amplify its power to linger in memory.

Conciseness and compression mark another feature. Poetic expression often condenses complexity into striking brevity. A few words can carry the weight of an extended argument or an entire narrative. Compression is not mere economy; it distills thought into heightened intensity, demanding close attention and inviting interpretation beyond the literal.

Emotional resonance is inseparable from poetic expression. Poetry does not simply state ideas; it evokes feelings. Through rhythm, imagery, ambiguity and sound, it amplifies affective impact, stirring joy, sorrow, wonder or awe. Emotional intensity is not an accident of poetic form but its essence, giving language the ability to move as well as inform.

Collective synchrony extends poetry’s reach from the individual to the group. Chants, refrains and ritual recitations synchronize not only words but bodies and voices. In such contexts, poetry binds individuals together into a shared rhythm and shared meaning. This collective dimension reveals poetry’s power not only as private reflection but as social glue, linking cognition and emotion to communal identity.

Taken together, these features suggest that poetic language is not reducible to ornament or artifice. It constitutes a mode of expression in which form and meaning are inseparable, in which rhythm and metaphor, sound and ambiguity, emotion and symbol intertwine. Poetic language communicates not just by telling but by shaping how experience is perceived, remembered and shared.

Neural Correlates of Poetic Features and Evidence in Human Cognition

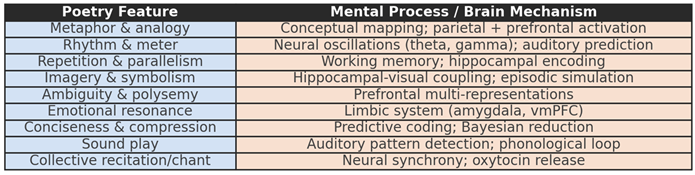

If poetic language is to be considered not merely an aesthetic phenomenon but a cognitive technology, it must be shown to align with identifiable brain mechanisms and cognitive processes. Research from cognitive linguistics, cognitive poetics, neurocognitive poetics and empirical neuroscience increasingly converges on the view that the above-mentioned hallmark features of poetry are deeply embedded in the neural architecture of the human mind (

Table 1).

Metaphor and analogy have been recognized in cognitive linguistics as the scaffolding of abstract thought (Lakoff and Johnson 1980). Neuroimaging studies reveal that metaphor engages distributed cortical networks, including the inferior frontal gyrus, anterior temporal cortex and inferior parietal lobule, supporting cross-domain integration (Bohrn, Altmann and Jacobs 2012). Multivariate pattern analysis shows that metaphoric meaning recruits both domain-general semantic systems and modality-specific sensory cortices, grounding abstract concepts in concrete experience (Xu et al. 2021). Evidence from clinical populations demonstrates that metaphor comprehension is impaired in left hemisphere degeneration, indicating the crucial role of frontal and temporal regions (Klooster et al. 2020). These findings confirm that metaphor is not decorative but fundamental to conceptual mapping in the brain.

Rhythm and repetition reflect the brain’s rhythmic nature. Cortical oscillations at multiple frequencies synchronize neural communication and linguistic rhythm entrains these oscillations to enhance prediction and comprehension (Giraud and Poeppel 2012). Theta–gamma coupling is particularly implicated in the segmentation and integration of speech, while delta rhythms align with prosodic patterns (Teng and Poeppel 2020). Repetition and parallelism, central to oral traditions, reinforce memory by supporting hippocampal encoding and cortical reinstatement (Jacobs 2015). Experimental studies demonstrate that neural entrainment to poetic meter predicts recall, showing a direct link between rhythm and memory (Shukla et al. 2021).

Imagery and symbolism are also supported by neurocognitive evidence. Poetry that evokes vivid images activates the hippocampus, precuneus and visual cortices, facilitating episodic simulation and associative binding (Benedek et al. 2014). Figurative and image-rich language strongly engages the default mode network (Zeman et al. 2013; Mar, Spreng and DeYoung 2021), suggesting that symbolic condensation taps into systems of internally directed cognition. This convergence indicates that poetry recruits not only language areas but also neural circuits associated with imagination and memory.

Ambiguity and polysemy distinguish poetic language from literal discourse. Ambiguous expressions engage bilateral inferior frontal gyrus and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, regions that maintain multiple competing interpretations and resolve conflict (Rodd et al. 2012; Vitello and Rodd 2015). Magnetoencephalography studies show that the brain sustains parallel semantic representations for hundreds of milliseconds before selecting a dominant meaning (Broderick et al. 2021). Such findings indicate that ambiguity is processed actively, rather than as noise and that it fosters the cognitive flexibility that is also central to creativity.

Sound play, including rhyme, alliteration and assonance, capitalizes on the auditory system’s sensitivity to pattern. The phonological loop of working memory is particularly responsive to these features (Baddeley 2012). Neuroimaging reveals that rhyme processing engages the superior temporal gyrus and inferior parietal regions, reflecting auditory pattern detection and memory chunking (Obermeier et al. 2016). These findings suggest that poetic sound structures exploit low-level auditory mechanisms to amplify high-level comprehension and recall.

Emotional resonance is among the most powerful aspects of poetry (Yukalov 2022). Neuroimaging demonstrates that poetic language activates the amygdala, anterior insula and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, particularly during moments of peak affect (Wassiliwizky et al. 2017). Subjective chills, often reported during aesthetic appreciation of poetry, correlate with activity in dopaminergic reward pathways, including the ventral striatum (Obermeier et al. 2016). This affective engagement distinguishes poetic from prosaic processing and underscores the link between poetic structure and emotion.

Collective synchrony extends poetic processing into the social domain. Ritual recitation, chant and song produce alignment not only at the behavioral level but also in physiology and neural activity. Hyperscanning studies show increased inter-brain synchrony during collective chanting or music-making, suggesting that rhythmic poetic language promotes group cohesion through shared neural states (Konvalinka et al. 2011; Kinreich et al. 2017; Müller et al. 2021). Such synchrony underpins the social dimension of poetry as a tool for bonding and cooperation.

The integration of these findings has been advanced by the field of cognitive poetics and by Jacobs’ neurocognitive poetics model (Tsur 2008; Steen 2011; Jacobs 2015). This model distinguishes between “foregrounding” devices like rhyme, metaphor or unusual syntax, that capture attention and evoke emotion and “backgrounding” elements that support narrative flow. Empirical studies confirm that foregrounding triggers enhanced activation in attention and affective networks, while backgrounding engages broader narrative comprehension circuits (Bohrn, Altmann and Jacobs 2013).

Anthropological perspectives reinforce these findings. Poetic forms such as chant, song and parallelism are documented universally in oral traditions (Fabb 2015; Norrick 2014). Their ubiquity across cultures suggests that poetic structuring evolved as a cognitive strategy for memory, prediction and social coordination long before the emergence of literacy.

Taken together, evidence from linguistics, neuroscience, psychology and anthropology demonstrates that the core features of poetic language are not ornamental but fundamental. They represent a cognitive technology that engages neural systems for abstraction, rhythm, imagery, ambiguity, sound, emotion and synchrony. In doing so, they enhance memory and prediction, foster creativity, amplify affect and cement social bonds. What literary studies have often described as aesthetic devices thus appear, in light of convergent empirical research, to reflect fundamental principles of thought and the very architecture of human cognition itself.

Evidence in Animal Communication

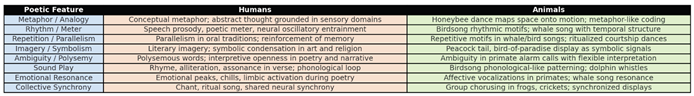

The presence of poetic features in nonhuman species suggests that patterned, symbolic and affective communication may be more ancient and widespread than once assumed. Far from being uniquely human, proto-poetic structures appear across the animal kingdom, where they serve functions of memory, prediction, signaling and social cohesion (

Table 2).

Birdsong has long been studied as a paradigmatic case of complex vocal behavior. Songbirds produce hierarchically organized sequences that include motifs, phrases and syntax-like rules (Berwick et al. 2011). These songs rely on rhythm, repetition and variation, often with motifs recurring across time to reinforce recognition (Mooney 2014; Wohlgemuth, Adam and Scharff 2014; Tyack 2020; Searcy, Soha, Peters and Nowicki 2021; Duque and Carruth 2022; Rose, Haakenson and Ball 2022). Birds also improvise within fixed structures, echoing poetic devices of variation within repetition. Neural studies show that these features are supported by specialized circuits such as the HVC and RA, which exhibit oscillatory coordination and experience-dependent plasticity (Mooney 2014). Birdsong therefore exhibits the rhythmic and repetitive structures that are central to poetic cognition.

Whale song provides another striking example. Humpback whales produce long, hierarchically nested vocalizations, often lasting for hours, characterized by repetition with variation and the gradual evolution of themes across breeding seasons (Dunlop, Noad, Cato and Stokes 2007; Mercado 2020; Warren et al. 2020; Mercado, Ashour and McAllister 2022; Girola, Dunlop and Noad 2023). These compositions resemble extended poetic or musical works, with motifs that are transmitted socially and modified across populations. Whale songs thus reveal not only repetition and rhythm but also cultural evolution akin to human oral traditions.

The honeybee dance translates spatial information into rhythmic bodily motion, encoding both distance and direction of food sources (De Marco, Gil and Farina 2005; Okada et al. 2008; Kohl et al. 2020; Linn et al. 2020; Doi, Deng and Ikegami 2023; Hadjitofi and Webb 2024). The waggle phase functions as a compressed symbolic mapping, akin to metaphor, by representing abstract coordinates through embodied motion (Seeley 2010). This cross-domain coding mirrors human metaphorical thinking, where abstract domains are mapped onto sensory-motor experiences.

Primate communication demonstrates ambiguity and polysemy, which are central to poetic discourse. Campbell’s monkeys, for instance, combine affixes with alarm calls to generate context-sensitive signals, such as modifying general alarm calls to specify aerial predators (Zuberbühler 2000; Ouattara et al., 2009; Lemasson and Hausberger 2011; Coye et al. 2015). This combinatorial flexibility shows that meaning is not fixed but layered, opening interpretive possibilities much like polysemy in human poetry. Other primates produce ambiguous vocalizations that require contextual interpretation, a feature that parallels the productive ambiguity of poetic texts.

Ritualized displays offer visual analogues of poetic form. The peacock’s tail or the elaborate dances of birds-of-paradise exemplify symbolic condensation and aesthetic exaggeration (Prum 2017). These displays rely on rhythm, symmetry and repetition and their effectiveness depends on aesthetic appreciation by conspecifics. They demonstrate that poetic features need not be vocal: bodily performance and ornament can achieve symbolic resonance.

Frogs and crickets exemplify collective synchrony in the nonhuman realm (Schneider et al. 2018; Escalona Sulbarán et al. 2019; Lee, Vélez and Bee 2023; Wu et al. 2023; Zigler et al. 2023; Brandt et al. 2023; Levy et al. 2025). In many species, males engage in antiphonal chorusing, producing rhythmic calls that synchronize across large groups. Such collective soundscapes resemble human chanting, where synchrony fosters group cohesion and amplifies signal strength.

Elephants provide evidence of emotional resonance in communication. Their infrasonic calls are used not only for coordination but also for mourning and reunion, producing behaviors that resemble human poetic lament or celebration. The affective dimension of these signals highlights the continuity of emotional expression across species.

Dolphins display remarkable sound play, producing whistles that include individual-specific “signature calls” as well as playful imitations of others’ signals (Janik 2000; Barton 2006; Simard et al. 2011; Fouda et al. 2018; Mishima et al. 2019). The combinatorial and playful aspects of dolphin vocalizations parallel rhyme and alliteration in human language, where sound structures are manipulated to create identity, cohesion or humor.

Taken together, these examples suggest that poetic features (metaphor-like coding, rhythm, repetition, imagery, ambiguity, sound play, emotional resonance and collective synchrony) are not uniquely human but broadly distributed across the animal kingdom. Birdsong and whale song demonstrate rhythm, repetition and cultural transmission; bees’ dances show metaphor-like mapping; primate calls reveal ambiguity and polysemy; ritualized displays exemplify symbolism and aesthetic form; frogs, crickets and wolves illustrate synchrony; elephants and dolphins highlight affect and playfulness. These findings support the hypothesis that poetry reflects ancient communicative strategies with deep evolutionary roots.

Evolutionary Functions

If poetic structures are deeply embedded in cognition, what adaptive purposes do they serve? From an evolutionary perspective, poetic features appear less as cultural ornaments and more as functional strategies that enhance survival and cooperation.

Memory reinforcement. Repetition, rhythm and parallelism improve encoding and retrieval, providing mnemonic scaffolds for oral traditions and knowledge transmission. Before literacy, societies relied on poetic forms to preserve genealogies, rituals and ecological knowledge. Neurocognitive evidence supports this function: rhythmic and repetitive structures enhance hippocampal consolidation and cortical reinstatement.

Predictive efficiency. Rhythm and meter align with neural oscillations, reducing uncertainty and sharpening temporal prediction (Teng and Poeppel 2020). Ambiguity sustains multiple interpretations, maintaining cognitive flexibility until environmental cues resolve uncertainty. Metaphor compresses complexity by linking distant domains, enabling efficient reasoning across contexts. These mechanisms reduce cognitive load and increase adaptability.

Social cohesion. Poetry is intrinsically social: collective chanting, song and ritual synchronize neural activity and arousal across individuals. Group synchrony, often mediated by oxytocin and dopamine release, fosters trust, cooperation and shared identity (Müller et al. 2021). The aesthetic and emotional resonance of poetic language motivates participation, reinforcing group cohesion.

Creativity and problem-solving. Ambiguity, imagery and metaphor allow the mind to explore multiple representational states. This flexibility enhances divergent thinking and innovation, adaptive in dynamic environments. Neuroimaging studies show that poetic and figurative language engages default mode and executive networks, systems central to creative cognition (Beaty et al. 2016).

Cross-species continuity. Animal communication reveals parallel functions: birdsong reinforces territory and memory, whale song evolves culturally to sustain social cohesion, honeybee dances compress spatial data into symbolic motion and primate calls use ambiguity to negotiate complex social interactions. These proto-poetic signals suggest that rhythmic, symbolic and affective communication confer advantages not only to humans but across species.

In sum, poetic structures serve crucial functions: they extend memory beyond individual limits, improve predictive modeling, cement social bonds and foster creativity. What humans recognize as poetry may thus reflect a fundamental evolutionary adaptation, an ancient cognitive technology that binds thought, emotion and society.

Applications and Future Directions

If poetic structuring is indeed a natural cognitive technology, its implications extend across neuroscience, comparative biology, education, therapy and artificial intelligence. This section outlines how the poetic cognition hypothesis may be tested and applied in diverse domains.

Experimental tests in humans. A central challenge is to move from correlational evidence to causal testing of poetic features. Neuroimaging can compare brain responses to poetic versus prosaic stimuli, isolating the contribution of metaphor, rhythm or ambiguity. For example, fMRI could examine whether metaphor-rich passages activate broader parietal–prefrontal networks than literal counterparts. EEG and MEG studies can track oscillatory entrainment to meter and rhyme, predicting stronger theta–gamma coupling during rhythmic exposure. Eye-tracking and pupillometry may complement these methods by indexing attention and cognitive load during poetic versus nonpoetic reading.

Comparative animal research. Applying the poeticity framework to animals invites systematic reanalysis of communication. Entropy-based measures could quantify structural complexity in birdsong or whale song, while acoustic analysis may reveal rhyme- or meter-like regularities in vocalizations. Neurophysiological recordings in primates could test whether ambiguous calls sustain prolonged prefrontal activation, as in humans confronted with polysemy. Social experiments could assess whether group synchrony in chorusing species (frogs, crickets, wolves) enhances cohesion and collective action, paralleling the effects of human chanting and ritual.

Evolutionary anthropology. Our approach reframes debates on language origins. Rather than arising solely from propositional or symbolic capacities, language may have emerged from rhythmic, metaphorical and emotionally charged proto-poetic systems. Archaeological evidence of ritual, music and symbolic ornamentation suggests that poeticity predates writing and may have scaffolded linguistic and cultural complexity. Future work could integrate genetic, archaeological and cognitive evidence to test whether poetic cognition was a selective advantage for early Homo.

Artificial intelligence. Poetic cognition can inspire novel AI architectures. Current models excel at literal processing but struggle with metaphor, ambiguity and flexible reasoning. Incorporating principles of poeticity could help AI approximate human-like thought. For instance, rhythmic processing might inform temporal models in recurrent or oscillatory networks, while metaphor-inspired cross-domain mapping could enhance transfer learning. Ambiguity-tolerant systems could improve creativity and robustness in uncertain environments. “Poetic AI” may not only generate verse but also reason in patterns closer to human cognition, with applications from natural language understanding to human–machine interaction.

Clinical and therapeutic contexts. Poetry has long been used informally in therapy, but the neurocognitive poetics model provides a framework for mechanistic application. Rhythmic recitation can improve speech fluency in aphasia. Metaphor enriches patient narratives, fostering new perspectives in psychotherapy. Poetry’s capacity to evoke emotion and synchrony may also mitigate loneliness or trauma, acting as a tool for social and affective regulation. Future clinical research could test whether poetic interventions specifically modulate limbic and prefrontal activity, thereby enhancing resilience.

Educational applications. Poetic structures can be harnessed to optimize learning. Rhythm and rhyme aid memory consolidation, particularly in children, by aligning with natural oscillatory mechanisms. Imagery and metaphor foster comprehension of abstract concepts, from mathematics to science education. Group recitation or song can enhance classroom cohesion and collective engagement, potentially improving attention and motivation. Developing curricula that systematically leverage poetic structuring could yield measurable gains in memory, prediction and creativity.

Future directions. To operationalize our framework, researchers must develop quantitative metrics of poeticity, applicable across species, cultures and modalities. Such metrics might quantify rhythmic regularity, degree of ambiguity or density of metaphorical mapping. Computational models could then simulate how poetic structuring influences prediction error, memory load or social cohesion. Combining behavioral, neuroimaging and comparative data would allow rigorous testing of whether poetic cognition constitutes a universal substrate of intelligence.

In sum, the poetic cognition hypothesis opens new frontiers. It encourages scientists to treat poetry not as ornament but as an evolved cognitive and communicative strategy, with testable predictions and wide-ranging applications in neuroscience, anthropology, education, therapy and AI.

Conclusions

The search for the “language of thought” has traditionally centered on symbolic logic, neural coding, predictive models or embodied processes. We have considered an alternative: that cognition itself may operate in a fundamentally poetic mode. Evidence from cognitive linguistics, neuroscience, anthropology and comparative biology suggests that the core features of poetry (namely, metaphor, rhythm, repetition, imagery, ambiguity, sound play, emotional resonance and collective synchrony) map onto identifiable neural mechanisms and serve adaptive functions. These structures support memory, enhance prediction, foster creativity and reinforce social cohesion, making them indispensable cognitive tools rather than cultural ornaments.

Through literary and ritual forms, humans exploit these mechanisms explicitly, but proto-poetic features also appear across species. Birdsong, whale song, honeybee dances, primate calls and ritualized displays exhibit rhythmic structuring, repetition with variation, symbolic compression and ambiguity. These parallels suggest that poeticity is not confined to human culture but reflects a deeper evolutionary substrate of communication and cognition.

By reframing poetry as a natural cognitive technology, we bridge disciplines and species, offering a unifying framework to study thought across biological systems. The challenge ahead is to operationalize this hypothesis: developing metrics of poeticity, conducting cross-species experiments and leveraging poetic principles in clinical, educational and artificial intelligence applications.

Ultimately, to ask whether humans and animals think in poetic language is to recognize that patterned, metaphorical and affective communication may be the foundation of intelligence itself. Rather than an aesthetic luxury, poetry may constitute the ancient rhythm through which brains, both human and nonhuman, make sense of the world together.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Informed Consent Statement

The Author transfers all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Author had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

During the preparation of this work, the author used ChatGPT 4o to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed, taking full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

References

- Barsalou, Lawrence W. 2008. “Grounded Cognition.” Annual Review of Psychology 59: 617–45. [CrossRef]

- Barton, R. A. “Animal Communication: Do Dolphins Have Names?” Current Biology 16, no. 15 (2006): R598–99. [CrossRef]

- Beaty, Roger E., Mathias Benedek, Paul J. Silvia and Daniel L. Schacter. 2016. “Creative Cognition and Brain Network Dynamics.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 20 (2): 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, Emily E., Sarah Duke, Hang Lu Wang and N. Mhatre. “The Ground Offers Acoustic Efficiency Gains for Crickets and Other Calling Animals.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120, no. 46 (2023): e2302814120. [CrossRef]

- Coye, Christelle, Kouakou Ouattara, Klaus Zuberbühler and Alban Lemasson. “Suffixation Influences Receivers’ Behaviour in Non-Human Primates.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 282, no. 1807 (2015): 20150265. [CrossRef]

- Doi, Ikegami T., W. Deng and T. Ikegami. “Spontaneous and Information-Induced Bursting Activities in Honeybee Hives.” Scientific Reports 13, no. 1 (2023): 11015. [CrossRef]

- Escalona Sulbarán, Mario D., Pedro Ivo Simões, Alejandro Gonzalez-Voyer and Santiago Castroviejo-Fisher. “Neotropical Frogs and Mating Songs: The Evolution of Advertisement Calls in Glassfrogs.” Journal of Evolutionary Biology 32, no. 2 (2019): 163–76. [CrossRef]

- Fabb, Nigel. 2015. What Is Poetry? Language and Memory in the Poems of the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fedorenko, E. and R. Varley. “Language and Thought Are Not the Same Thing: Evidence from Neuroimaging and Neurological Patients.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1369, no. 1 (April 2016): 132–153. [CrossRef]

- Fedorenko, E., S. T. Piantadosi and E. A. F. Gibson. “Language Is Primarily a Tool for Communication Rather than Thought.” Nature 630, 2024, 575–586. [CrossRef]

- Fodor, Jerry A. 1975. The Language of Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Fouda, L., J. E. Wingfield, A. D. Fandel, A. Garrod, K. B. Hodge, A. N. Rice and H. Bailey. “Dolphins Simplify Their Vocal Calls in Response to Increased Ambient Noise.” Biology Letters 14, no. 10 (2018): 20180484. [CrossRef]

- Frankland, S. M. and J. D. Greene. “Concepts and Compositionality: In Search of the Brain’s Language of Thought.” Annual Review of Psychology 71 (January 4, 2020): 273–303. [CrossRef]

- Friston, Karl. 2010. “The Free-Energy Principle: A Unified Brain Theory?” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11 (2): 127–38. [CrossRef]

- Hadjitofi andriani and Barbara Webb. “Dynamic Antennal Positioning Allows Honeybee Followers to Decode the Dance.” Current Biology 34, no. 8 (2024): 1772–79.e4. [CrossRef]

- Hogan, Patrick Colm. Affective Narratology. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

- Jacobs, Arthur M. “The Scientific Study of Literary Experience: Sampling the State of the Art.” Scientific Study of Literature 5 (2015): 139–170.

- Jakobson, Roman. “Linguistics and Poetics.” In Style in Language, edited by T. A. Sebeok, 350–377. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1960.

- Kuang, Changyi, Jun Chen, Jiawen Chen, Yafei Shi, Huiyuan Huang, Bingqing Jiao, Qiwen Lin, Yuyang Rao, Wenting Liu, Yunpeng Zhu, Lei Mo, Lijun Ma and Jiabao Lin. 2022. “Uncovering Neural Distinctions and Commodities between Two Creativity Subsets: A Meta--Analysis of fMRI Studies in Divergent Thinking and Insight Using Activation Likelihood Estimation.” Human Brain Mapping 43 (16): 4864–85. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A.M. Towards a Neurocognitive Poetics Model of Literary Reading. Cogn. Crit. 2015, 1, 135–59.

- Janik, V. M. “Food-Related Bray Calls in Wild Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus).” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 267, no. 1446 (2000): 923–27. [CrossRef]

- Kinreich, Sivan, Hilla Djalovski, David Kraus, Tsachi Ein-Dor and Ruth Feldman. 2017. “Brain-to-Brain Synchrony during Naturalistic Social Interactions.” Scientific Reports 7: 17060. [CrossRef]

- Klooster, Nathaniel, Marguerite McQuire, Murray Grossman, Corey McMillan, Anjan Chatterjee and Eileen Cardillo. 2020. “The Neural Basis of Metaphor Comprehension: Evidence from Left Hemisphere Degeneration.” Neurobiology of Language 1 (4): 474–91. [CrossRef]

- Kohl, Philipp L., Natesan Thulasi, Beat Rutschmann, Emily A. George, Ingolf Steffan-Dewenter and Axel Brockmann. “Adaptive Evolution of Honeybee Dance Dialects.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 287, no. 1922 (2020): 20200190. [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lee, Nathan, Ana Vélez and Mark Bee. “Behind the Mask(ing): How Frogs Cope with Noise.” Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Neuroethology, Sensory, Neural and Behavioral Physiology 209, no. 1 (2023): 47–66. [CrossRef]

- Lemasson, Alban and Martine Hausberger. “Acoustic Variability and Social Significance of Calls in Female Campbell’s Monkeys (Cercopithecus campbelli campbelli).” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 129, no. 5 (2011): 3341–52. [CrossRef]

- Levy, Keren, Yin Yan Aidan, Dana Paz, Hassan Medlij and Amir Ayali. “Light Alters Calling-Song Characteristics in Crickets.” Journal of Experimental Biology 228, no. 4 (2025): JEB249404. [CrossRef]

- Linn, Margot, Sarah M. Glaser, Teng Peng and Christoph Grüter. “Octopamine and Dopamine Mediate Waggle Dance Following and Information Use in Honeybees.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 287, no. 1936 (2020): 20201950. [CrossRef]

- Lotman, Yuri. The Structure of the Artistic Text. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1977.

- Mahowald, K., A. A. Ivanova, I. A. Blank, N. Kanwisher, J. B. Tenenbaum and E. Fedorenko. “Dissociating Language and Thought in Large Language Models.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 28, no. 6 (June 2024): 517–540. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Iglesias, S. and R. F. Flórez. “Thought, Language and Care.” Enfermería Intensiva (English Edition) 29, no. 4 (October–December 2018): 147–148. [CrossRef]

- Mishima, Yuki, Tadamichi Morisaka, Masaki Ishikawa, Yukinori Karasawa and Yasuhiko Yoshida. “Pulsed Call Sequences as Contact Calls in Pacific White-Sided Dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens).” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 146, no. 1 (2019): 409. [CrossRef]

- Müller, Valentin, Marcus Müller, Michael T. Delius and Ulman Lindenberger. 2021. “Interpersonal Synchrony and Network Dynamics in Multimodal Hyperscanning.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 25 (6): 482–95. [CrossRef]

- Okada, R., H. Ikeno, N. Sasayama, H. Aonuma, D. Kurabayashi and E. Ito. “The Dance of the Honeybee: How Do Honeybees Dance to Transfer Food Information Effectively?” Acta Biologica Hungarica 59, Suppl. (2008): 157–62. [CrossRef]

- Obermeier, Christian, et al. “Aesthetic Appreciation of Poetry Correlates with Ease of Processing in the Brain: An fMRI Study.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 8 (2013a): 490–498.

- Obermeier, Christian, Winfried Menninghaus, Martin von Koppenfels, Tim Raettig, Maren Schmidt-Kassow, et al. 2013b. “Aesthetic and Emotional Effects of Meter and Rhyme in Poetry.” Frontiers in Psychology 4 (Psychology of Language): 10. [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, Kouakou, Alban Lemasson and Klaus Zuberbühler. “Campbell’s Monkeys Use Affixation to Alter Call Meaning.” PLoS One 4, no. 11 (2009): e7808. [CrossRef]

- Simard, Patrice, N. Lace, S. Gowans, E. Quintana-Rizzo, S. A. Kuczaj, R. S. Wells and D. A. Mann. “Low Frequency Narrow-Band Calls in Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus): Signal Properties, Function and Conservation Implications.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 130, no. 5 (2011): 3068–76. [CrossRef]

- Tsur, Reuven. What Makes Sound Patterns Expressive?. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992.

- Prum, Richard O. 2017. The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World—and Us. New York: Doubleday.

- Schneider, W. Timothy, Christian Rutz, Berthold Hedwig and Nathan W. Bailey. “Vestigial Singing Behaviour Persists after the Evolutionary Loss of Song in Crickets.” Biol. Lett. 2018, 14, 20170654. [CrossRef]

- Steen, Gerard J. 2011. “The Contemporary Theory of Metaphor—Now New and Improved!” Review of Cognitive Linguistics 9 (1): 26–64. [CrossRef]

- Tsur, Reuven. 2008. Toward a Theory of Cognitive Poetics. 2nd ed. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

- Teng, Xiangbin and David Poeppel. 2020. “Theta and Gamma Bands Encode Acoustic Dynamics in Speech.” Cerebral Cortex 30 (3): 1609–21. [CrossRef]

- Vitello, Sylvia and Jennifer M. Rodd. 2015. “Resolving Semantic Ambiguities in Sentences: Cognitive and Neural Mechanisms.” Language and Linguistics Compass 9 (10): 391–405. [CrossRef]

- Wassiliwizky, Eugen, Michael Koelsch, Valentin Wagner, Thomas Jacobsen and Winfried Menninghaus. 2017. “The Emotional Power of Poetry: Neural Circuitry, Psychophysiology and Compositional Principles.” Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 12 (8): 1229–40. [CrossRef]

- Yukalov, V. I. 2022. “Quantification of Emotions in Decision Making.” Soft Computing 26: 2419–36. [CrossRef]

- Wimsatt, W. K. and Monroe C. Beardsley. The Verbal Icon: Studies in the Meaning of Poetry. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1954.Wu, Yong, Xiaofeng Luo, Ping Chen and Fang Zhang. “Frequency Jumps and Subharmonic Components in Calls of Female Odorrana tormota Differentially Affect the Vocal Behaviors of Male Frogs.” Frontiers in Zoology 2023, 20, 39. [CrossRef]

- Zigler andrew, Sarah Straw, Isao Tokuda, Erin Bronson and Tobias Riede. “Critical Calls: Circadian and Seasonal Periodicity in Vocal Activity in a Breeding Colony of Panamanian Golden Frogs (Atelopus zeteki).” PLoS One 18, no. 8 (2023): e0286582. [CrossRef]

- Zuberbühler, Klaus. “Interspecies Semantic Communication in Two Forest Primates.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B 267, no. 1444 (2000): 713–18. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Neural correlates of poetic features. Each feature of poetic language is associated with specific cognitive processes and brain mechanisms. Metaphor and analogy engage parietal and prefrontal regions for conceptual mapping; rhythm and meter rely on oscillatory entrainment; repetition and parallelism support hippocampal memory encoding; imagery and symbolism link hippocampal and visual areas; ambiguity recruits prefrontal multi-representations; emotional resonance involves the limbic system; conciseness and compression reflect predictive coding; sound play exploits auditory and phonological circuits; and collective recitation promotes neural synchrony and oxytocin-mediated social bonding.

Table 1.

Neural correlates of poetic features. Each feature of poetic language is associated with specific cognitive processes and brain mechanisms. Metaphor and analogy engage parietal and prefrontal regions for conceptual mapping; rhythm and meter rely on oscillatory entrainment; repetition and parallelism support hippocampal memory encoding; imagery and symbolism link hippocampal and visual areas; ambiguity recruits prefrontal multi-representations; emotional resonance involves the limbic system; conciseness and compression reflect predictive coding; sound play exploits auditory and phonological circuits; and collective recitation promotes neural synchrony and oxytocin-mediated social bonding.

Table 2.

Comparative overview of poetic features in humans and animals. Humans employ metaphor, rhythm, repetition, imagery, ambiguity, sound play, emotional resonance and synchrony in cognition, memory and culture. Animals display analogous “proto-poetic” structures: honeybee dance as metaphor-like coding, birdsong and whale song as rhythmic and repetitive motifs, primate calls as ambiguous signals and ritualized displays such as the peacock’s tail as symbolic communication. The table highlights evolutionary continuities, suggesting that poetic structuring may serve shared cognitive and social functions across species.

Table 2.

Comparative overview of poetic features in humans and animals. Humans employ metaphor, rhythm, repetition, imagery, ambiguity, sound play, emotional resonance and synchrony in cognition, memory and culture. Animals display analogous “proto-poetic” structures: honeybee dance as metaphor-like coding, birdsong and whale song as rhythmic and repetitive motifs, primate calls as ambiguous signals and ritualized displays such as the peacock’s tail as symbolic communication. The table highlights evolutionary continuities, suggesting that poetic structuring may serve shared cognitive and social functions across species.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).