1. Background Theory

To facilitate subsequent derivations and avoid doubts about the theoretical basis, the following basic theories are listed first:

Ferromagnets in a magnetic field will shield or conduct the magnetic field, and with temperature changes, the Curie phase transition occurs, transitioning from the ferromagnetic state to the paramagnetic state, causing the shielding or conduction function to disappear.

Since the Curie phase transition occurs due to changes in the arrangement of ferromagnetic domains, the root cause is temperature changes. According to energy conservation, after a phase transition cycle, the object returns to its initial state, and the cumulative heat consumption of the entire process is zero. Here, the phase transition cycle refers to the object: normal state → Curie state → normal state, or Curie state → normal state → Curie state.

According to magnet medium thermodynamics, for an object in a magnetic field H with magnetization intensity M, neglecting the excited magnetic field, the magnetization work done by the magnetic field on the magnetized object is:

,

is the vacuum permeability (4π×10⁻⁷ H/m). [

1,

2,

3]

According to classical electrodynamics, the static magnetic field of a permanent magnet does mechanical work on an approaching ferromagnet: , where F is the magnetic force of the permanent magnet on the ferromagnet, and L is the displacement of the ferromagnet in the magnetic field.

According to Ampère’s circuital law, the curl of a static magnetic field without current is zero, , belonging to a conservative field, satisfying , and the magnetic field of a permanent magnet is such a conservative field.

According to the first law of thermodynamics, , which also means that energy is conserved at all times, and it is impossible for only one form of energy to change over a period. The energy formula is a state function; for an object, no matter how the state changes during the process, if it completely returns to the initial state (including temperature), its internal energy is conserved.

According to the ideal gas state equation , compressing or releasing a certain amount of gas in an adiabatic box can achieve temperature changes inside the box; when returning to the original state, the temperature recovers, and no energy is consumed during this process, with zero work done by the external environment.

In the theoretical analysis of this paper, to simplify the analysis, the following factors are temporarily not considered: assuming complete magnetic shielding in the normal ferromagnetic state, adiabatic phase transition for the Curie ferromagnet with no heat exchange with the external environment during phase transition; thermal dissipation such as hysteresis loss of objects in the model; no energy consumption for displacement without force; not considering the thermodynamic volume work caused by volume changes of the Curie ferromagnet due to temperature and magnetic field changes (e.g., magnetostriction). This will be uniformly explained at the end of the article.

2. Problem Description and Simulation Model

The origin of the issue in this paper is that, while analyzing the dynamic shielding magnetic field during Curie phase transition, it was observed that in one phase transition cycle of a shielding model, the cumulative mechanical work is non-zero, raising questions about the thermodynamic source of this work.

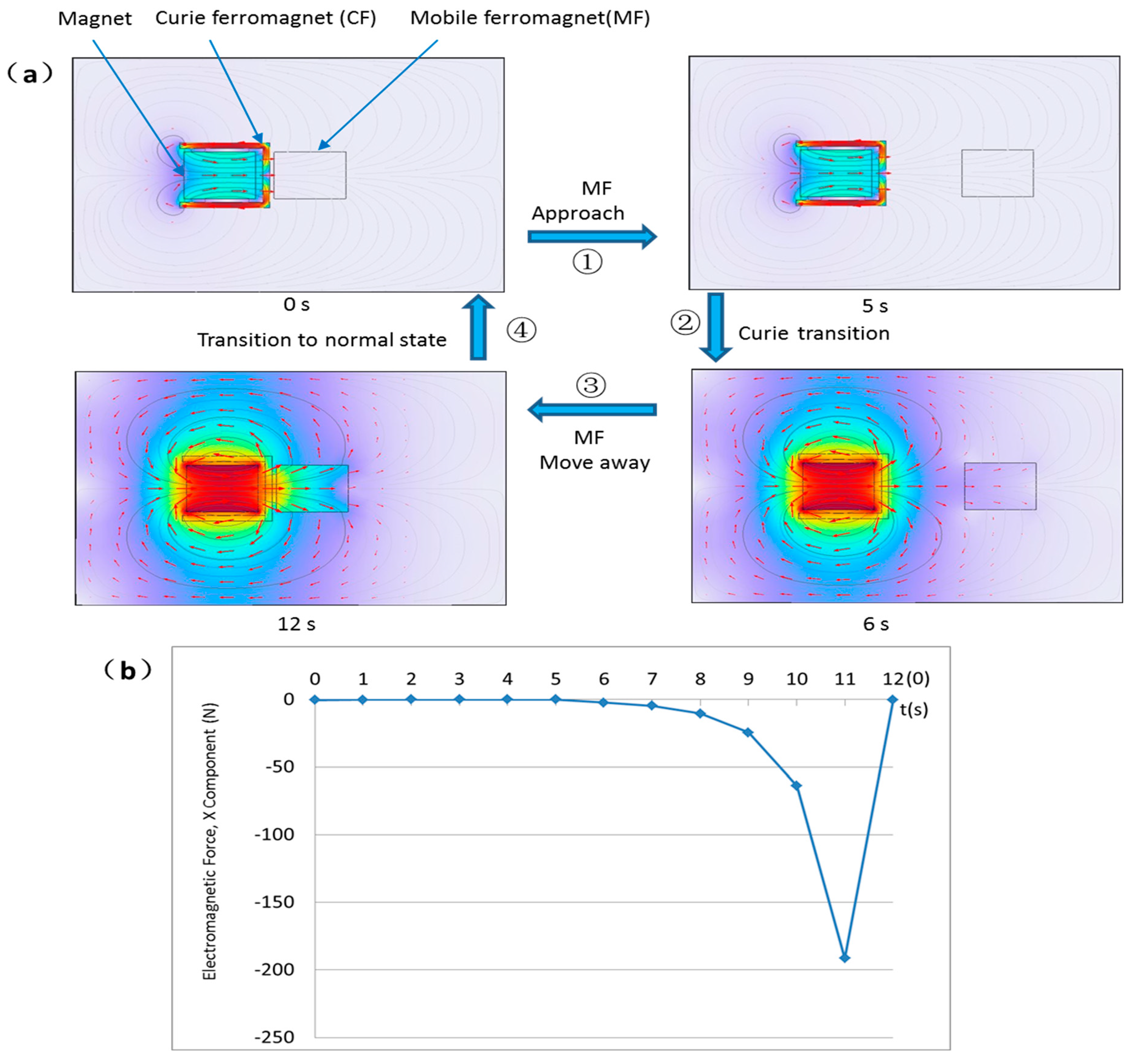

Figure 1a shows the dynamic simulation cloud diagram of the Curie phase transition shielding magnetic field model. In the diagram, the left side consists of a fixed cylindrical permanent magnet that forms the static magnetic field of the model. The permanent magnet is placed inside a cylindrical Curie ferromagnet, while the left side features a cylindrical ferromagnet capable of moving left and right.

The specific action sequence of the model dynamic operation is as follows:

Initially, the mobile ferromagnet is close to the Curie ferromagnet and the permanent magnet, while the Curie ferromagnet is in the normal state and shields the magnetic field;

Step ①, within 0-5 seconds, the mobile ferromagnet moves away from the Curie ferromagnet;

Step ②, at 5 seconds the mobile ferromagnet stops, within 5-6 seconds the Curie ferromagnet transitions to the Curie state, while ceasing to shield the magnetic field;

Step ③, within 6-11 seconds, the mobile ferromagnet approaches the Curie ferromagnet;

Step ④, the Curie ferromagnet returns to the initial normal state.

Figure 1b shows the magnetic force curve on the mobile ferromagnet over time during one cycle of the model, which is also the electromagnetic force curve of the mobile ferromagnet at different displacements. The negative force value in the chart indicates that the force on the mobile ferromagnet is opposite to the direction of the software coordinate system. Clearly, when magnetic shielding is active, the mobile ferromagnet experiences almost no magnetic force when moving away, but after the Curie ferromagnet transitions to the normal state, the mobile ferromagnet experiences a magnetic force when approaching. This results in the line integral of the magnetic force on the mobile ferromagnet over a closed path not being zero after one cycle of the model, and the mobile ferromagnet obtains non-zero mechanical work.

What kind of energy does this remaining mechanical work come from, and how is it converted? The mechanical work on the mobile ferromagnet is clearly done by the magnetic field of the permanent magnet, but the static magnetic field of the permanent magnet is a conservative field, and the line integral of the magnetic force over a loop is zero. Moreover, the permanent magnet only provides the static magnetic field, and its internal energy remains unchanged. According to the first law of thermodynamics, the energy of an object is a state function, independent of the process, and only related to the change between initial and final states; therefore, after one cycle, the Curie ferromagnet returns to its initial state, and its internal energy also remains unchanged.

The Curie ferromagnet cannot directly do mechanical work on the mobile ferromagnet through heat transfer; energy exchange between them should only occur through electromagnetic interaction.

During model operation, when the Curie ferromagnet is in the ferromagnetic state, the mobile ferromagnet is not magnetized and they do not affect each other, and when the mobile ferromagnet is magnetized, the Curie ferromagnet is in the Curie state and they still do not affect each other, so there seems to be no opportunity for direct energy exchange between them. Therefore, the net mechanical work obtained by the mobile ferromagnet lacks a clear energy source, raising doubts about the energy conservation of the isolated system. Further analysis through thermodynamic theory is necessary.

3. Energy Exchange Analysis Between Mobile Ferromagnet and Curie Ferromagnet

During the Curie phase transition in a magnetic field, the Curie ferromagnet undergoes magnetization work, entropy changes, causing heat absorption and release; the phase transition itself also involves heat absorption and release, making energy conversion complex. This model has multiple steps in the phase transition cycle, and the magnetic field is variable. If analyzed step by step according to energy conversion, it would become extremely cumbersome and easy to confuse. Detailed analysis of energy conversion at each step is not the focus of this paper. From the main purpose of this paper, it only aims to analyze the overall energy change of the model after one complete phase transition cycle. By considering from different angles, the overall comparison method is finally chosen for analysis, which easily clarifies the overall energy change of the model, as detailed below.

The following analysis assumes that the Curie ferromagnet is in an adiabatic environment, with no thermal dissipation, and the entropy increase to the external environment is zero: . Then, only the conversion between internal energy and work of the Curie ferromagnet needs to be analyzed, i.e., its energy change: .

In all following graphical models, 1 represents the permanent magnet, 2 represents the Curie ferromagnet, 3 represents the mobile ferromagnet. Parameters in formulas correspond to objects with subscripts, e.g., H1represents the magnetic field of permanent magnet 1, is the magnetic moment of the Curie ferromagnet relative to H1, represents the work done by the magnetic force of the permanent magnet on the mobile ferromagnet, U represents the internal energy of an object, and E represents the energy of an object.

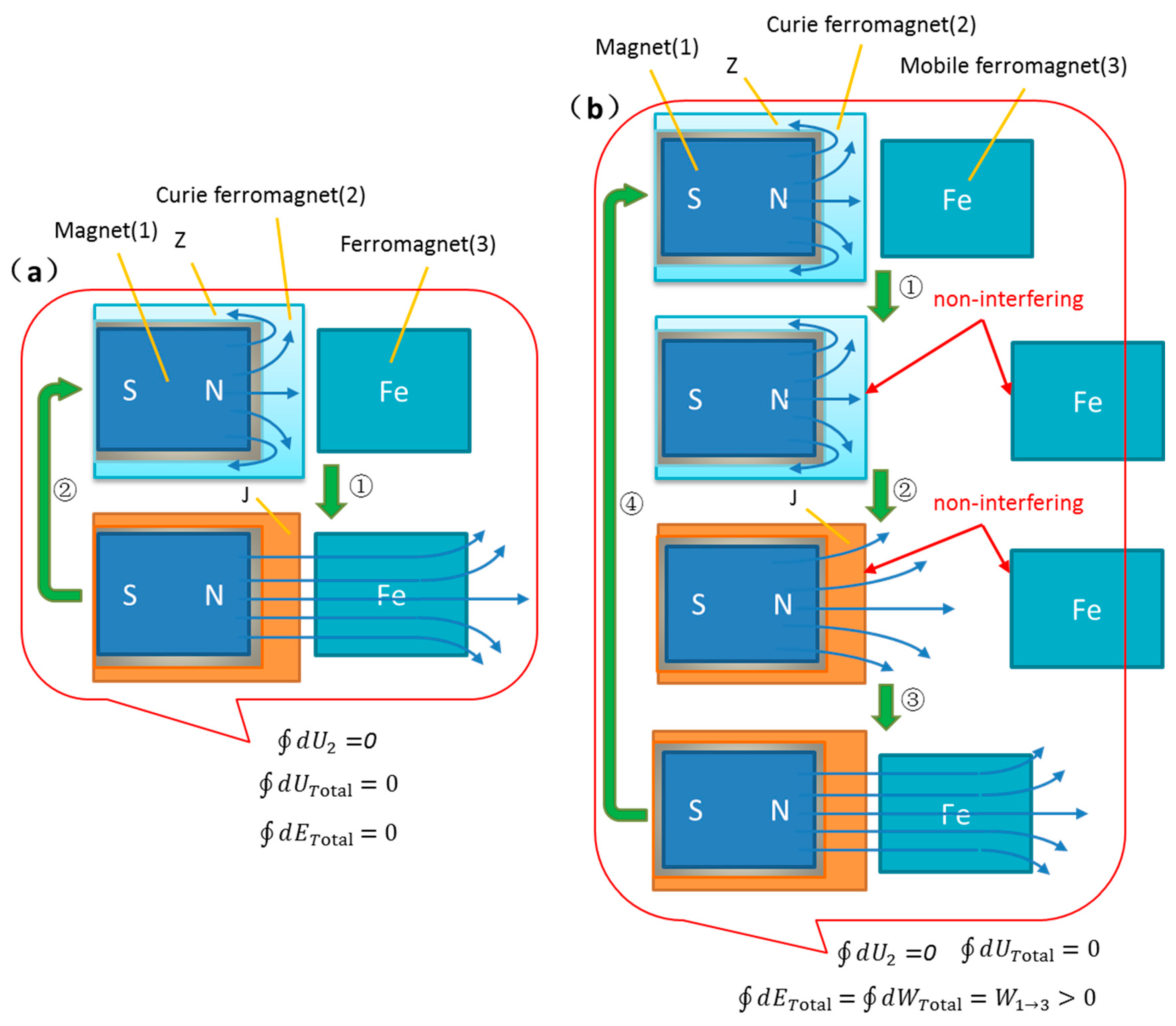

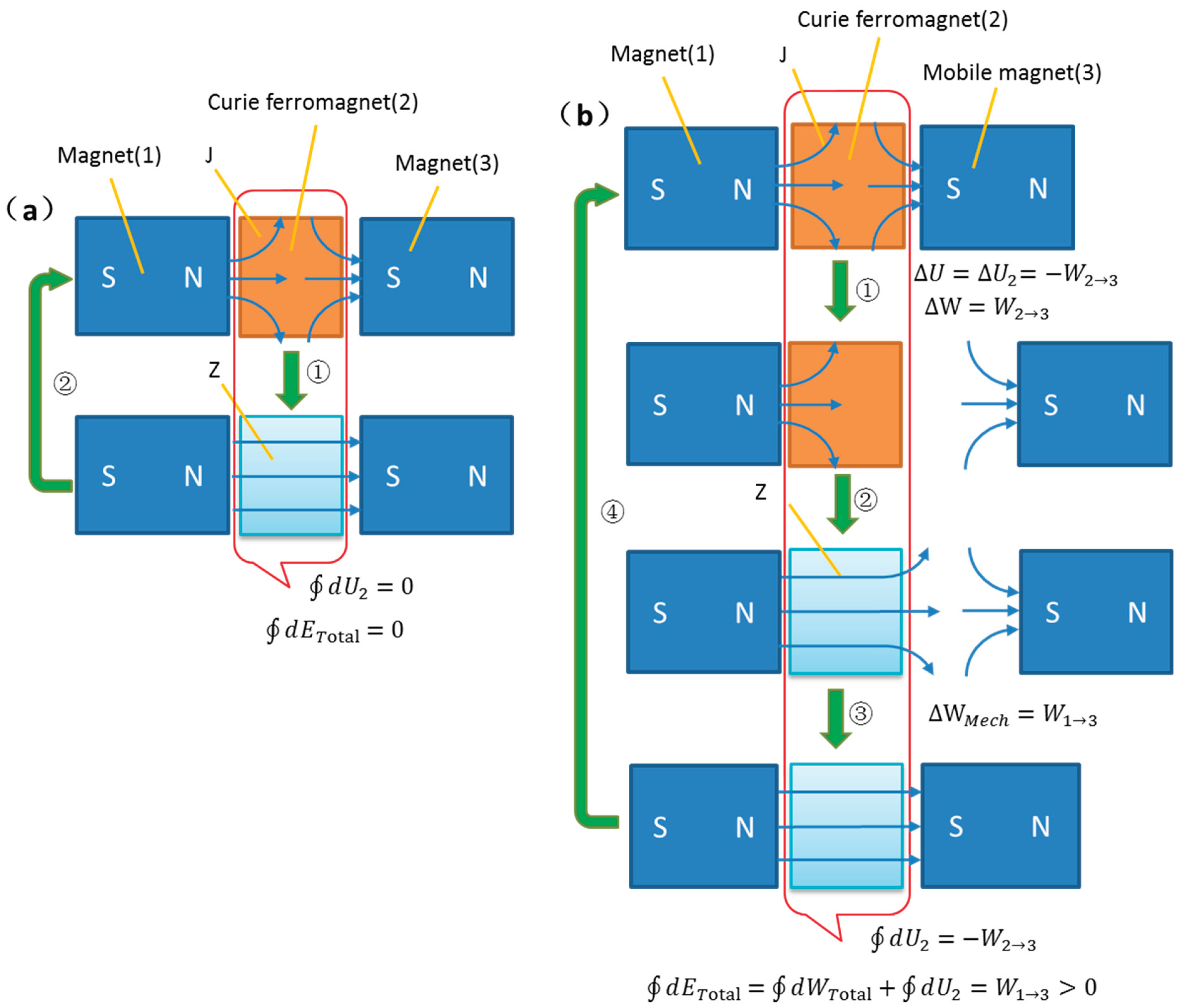

As shown in

Figure 2, a model similar to

Figure 1a is shown in

Figure 2a, with the difference that the mobile ferromagnet is fixed. According to phase transition reversibility, for one phase transition cycle in

Figure 2a, the cumulative magnetization work obtained by the Curie ferromagnet from the magnetic field is zero:

Therefore, the internal energy is conserved ∮dU2=0; the cumulative magnetization work obtained by the mobile ferromagnet is also zero, so the internal energy of the entire system is conserved: . The mechanical work produced by the system is zero, and the entire model energy is conserved: .

By comparison,

Figure 2b differs from

Figure 2a in that the mobile ferromagnet moves away when the Curie ferromagnet is in the normal state, and after the Curie ferromagnet transitions to the Curie state, the mobile ferromagnet approaches and returns near the Curie ferromagnet.

3.1. No energy Influence Between Mobile Ferromagnet Movement Process and Curie Ferromagnet

First, analyze whether energy exchange occurs between the mobile ferromagnet and the Curie ferromagnet during the movement process. From

Figure 2b, it can be seen that when the mobile ferromagnet moves away, the Curie ferromagnet completely shields the magnetic field, so the mobile ferromagnet and the Curie ferromagnet do not affect each other; similarly, when the mobile ferromagnet approaches, it is magnetized by the magnetic field producing an induced magnetic field, but at this time the Curie ferromagnet is already in the Curie state and is a paramagnet, so they still do not affect each other.

The above shows that

the reciprocating motion of the mobile ferromagnet in Figure 2b does not consume any internal energy of the model, and since the internal energy is conserved in Figure 2a, the internal energy in Figure 2b is also conserved.

3.2. No Cumulative Magnetization Work from Mobile Ferromagnet to Curie Ferromagnet

Changes in work lead to energy changes; the mobile ferromagnet can only exchange energy with the Curie ferromagnet through magnetization work, so analyzing the magnetization work between them can also illustrate the energy exchange.

The Curie phase transition is actually a process; through analysis of the entire model process, the mobile ferromagnet and the Curie ferromagnet only have transient magnetization work influence during the mixed state of the Curie phase transition process. In this process, part of the magnetic field passes through the Curie ferromagnet and induces a magnetic field B in the mobile ferromagnet, and the induced magnetic field in turn induces the Curie ferromagnet and produces a magnetic moment .

For the phase transition process in

Figure 2a, the mobile ferromagnet does magnetization work on the Curie ferromagnet during the process:

, and the Curie ferromagnet produces a corresponding induced magnetic field. But after the Curie ferromagnet completely transitions, the cumulative magnetization work done by the mobile ferromagnet on the Curie ferromagnet is zero:

Therefore, regardless of the presence of the mobile ferromagnet, the Curie ferromagnet transitions to the Curie state, and the final magnetization work obtained is the same, for example, step ① in

Figure 2a and step ② in

Figure 2b. The magnetization work is:

This also shows that there is no cumulative magnetization work from the mobile ferromagnet to the Curie ferromagnet, consistent with the theory that energy change of an object only depends on the initial and final states, and is independent of the energy conversion path.

But obviously, in

Figure 2b, the work done by the magnetic force on the mobile ferromagnet during approach is not zero:

In the formula, F1→3is the magnetic force of the permanent magnet on the mobile ferromagnet, and L is the displacement of the mobile ferromagnet in the magnetic field. The model obtains non-zero mechanical work additionally while the internal energy is conserved in one cycle, which contradicts the law of energy conservation.

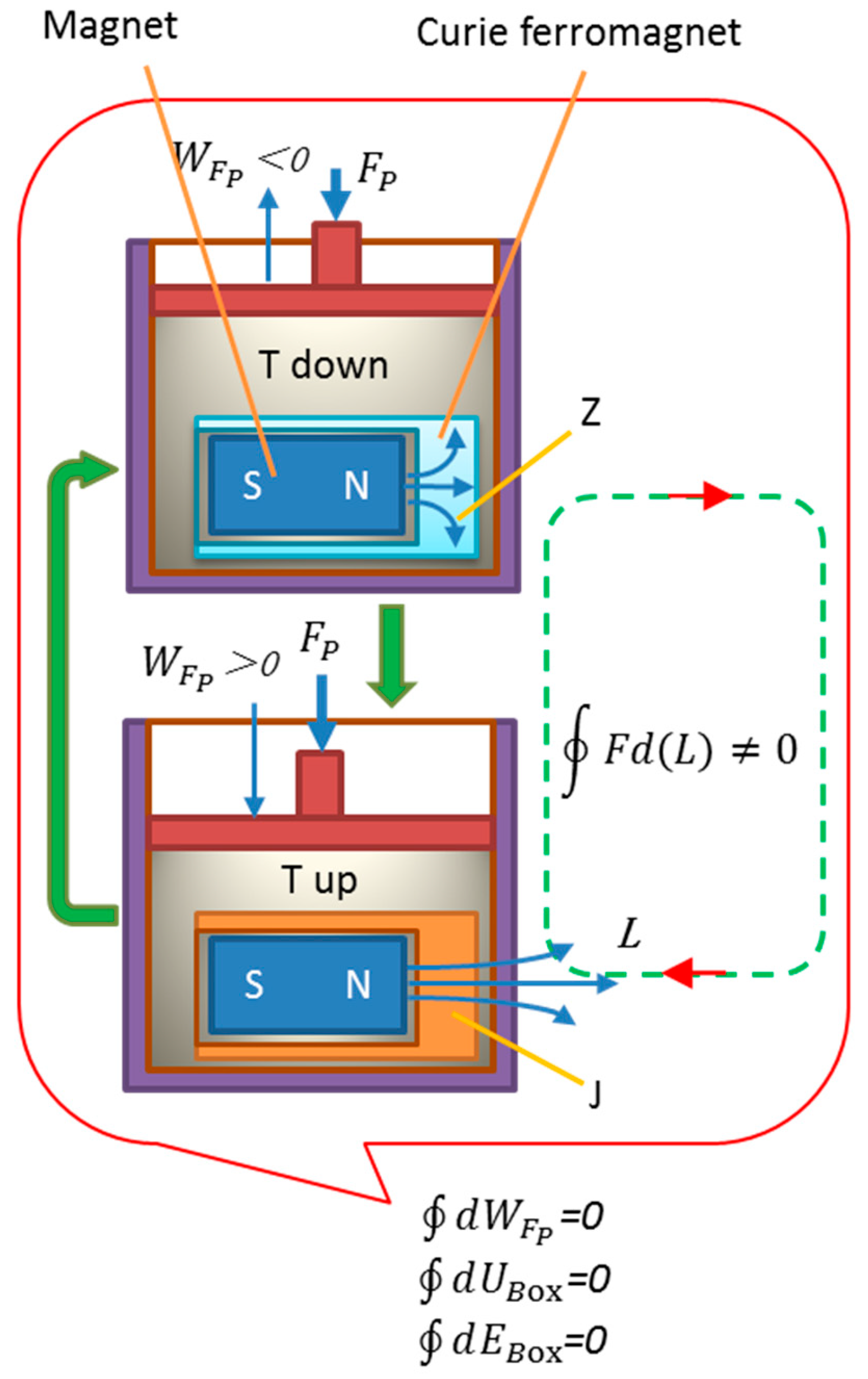

4. Compressible Adiabatic Box Illustrates Phase Transition Depends on Temperature Rather than Consuming Energy

According to the law of energy conservation and phase transition theory, no substance phase transition truly consumes energy; the Curie phase transition is the same, entirely caused by temperature changes leading to phase transition, temporarily exchanging heat with the external environment during the process, and a complete phase transition cycle does not consume energy, with internal energy unchanged. If in an adiabatic environment, the internal energy of the environment is also unchanged after one cycle, but the Curie phase transition is still questioned to consume energy. To avoid questioning, a completely mechanical work-driven adiabatic device for environmental temperature changes is listed below, which can intuitively show that the Curie phase transition is entirely determined by temperature and does not truly consume or dissipate energy, as shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 places the Curie phase transition system excluding the mobile ferromagnet from

Figure 2a into an adiabatic box with a piston, filled with ideal gas. The external environment compresses or releases the gas in the box through the piston, changing the internal temperature of the box to achieve the Curie phase transition. According to the ideal gas state equation:

, the external force compressing the piston

does positive work

, and the gas heats up; conversely,

does negative work

, and the gas cools down. After one cycle returning to the original state, the external work is zero. Because the Curie phase transition system composed of the Curie ferromagnet and the permanent magnet must comply with the law of energy conservation, after one phase transition cycle returning to the original state, the internal energy of the Curie ferromagnet and the ideal gas each remains unchanged, and the overall internal energy of the adiabatic box system is unchanged. Let the overall internal energy of the adiabatic box system be represented as

, then the internal energy and energy conservation for

Figure 2a:

=0, =0. Through the energy analysis of

Figure 3, it illustrates that

the Curie phase transition does not consume energy, but only exchanges energy with the external environment to undergo phase transition.

5. Reason for Mobile ferromagnet Obtaining Net Work: Temporal Non-Conservative Field

For the Curie phase transition system in

Figure 3, the Curie ferromagnet intermittently shields the permanent magnet’s magnetic field during one phase transition cycle, objectively intermittently changing the direction and distribution of the static magnetic field, turning the originally conservative magnetic field on the right side of the system into

a temporal non-conservative field. Ferromagnetic material moving on the path corresponding to this temporal non-conservative field will inevitably result in the line integral of the magnetic force of the permanent magnet on the mobile ferromagnet no longer being zero

. More importantly, the energy of the Curie phase transition system in

Figure 3 itself is conserved; no matter how the phase transition occurs, the system does not consume any energy. The Curie phase transition system itself is energy conservative, meaning that forming this temporal non-conservative field requires no energy consumption. The magnetic field of the permanent magnet is a conservative field, and its line integral over the mobile ferromagnet’s path is zero. It is precisely due to the Curie ferromagnet phase transition changing the magnetic field distribution in time sequence that causes the mobile ferromagnet to move at corresponding times, resulting in a non-zero line integral. If a mobile ferromagnet is added on the right side and moves according to the corresponding time sequence, as shown in

Figure 2b, it can completely enable the mobile ferromagnet to obtain non-zero mechanical work, which contradicts energy conservation.

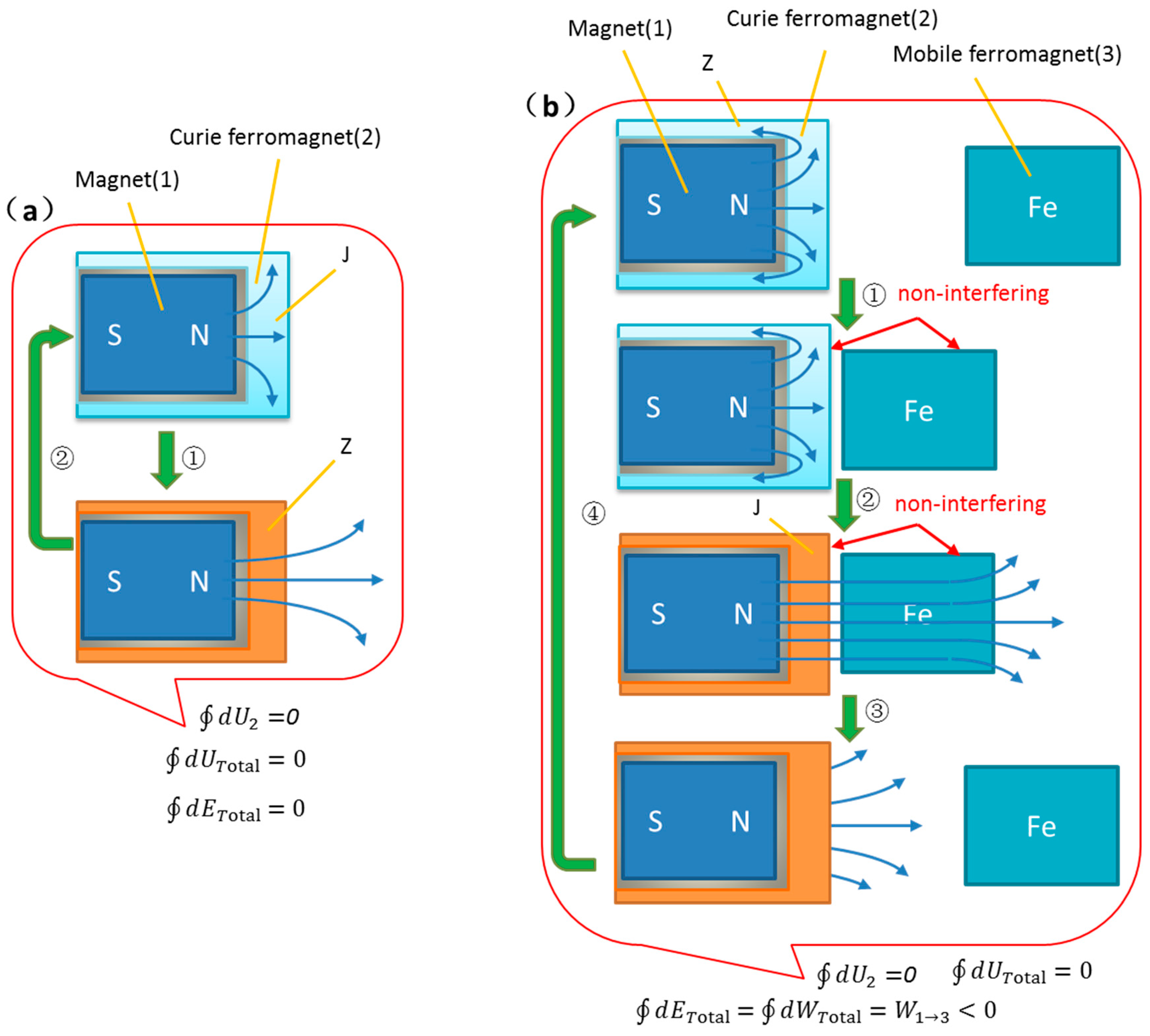

6. Reverse Proof of Model Energy Conservation Contradiction

Since it is a non-conservative field, the non-zero work done by the conservative field on an object can be greater than zero or less than zero. Below, the reverse motion situation of the mobile ferromagnet is analyzed, as shown in

Figure 4a.

Figure 4a has no mobile ferromagnet compared to

Figure 2a.

Figure 4b has the opposite motion process of the mobile ferromagnet compared to

Figure 2b. The same method of analysis shows that the mobile ferromagnet has no effect on the Curie ferromagnet during the approaching process in steps ① and ②, and the internal energy change is exactly the same as in

Figure 4a without the mobile ferromagnet, and the internal energy of the entire system is conserved.

Obviously, after completing one phase transition cycle in

Figure 4b, the mobile ferromagnet obtains negative mechanical work, and energy is consumed. Assuming the model conserves energy, then the model as an isolated system must have some kind of energy increase in some object. For a system with only three objects, the internal energy of the permanent magnet is unchanged, so only the Curie ferromagnet has obtained positive energy in some way. Since the Curie ferromagnet is in an adiabatic environment and adiabatic with the mobile ferromagnet, the two can only exchange energy through magnetization work. But it has been proven that the cumulative magnetization work of the mobile ferromagnet on the Curie ferromagnet throughout the process is zero. The reciprocating motion of the unmagnetized mobile ferromagnet causing the internal energy of the Curie ferromagnet to continuously increase violates physical common sense, which shows that the assumption of energy conservation is invalid and contradicts the conservation law.

7. Mobile Ferromagnet Replaced by Permanent Magnet Model Analysis

If the mobile ferromagnet in the model is replaced by a mobile permanent magnet, the mobile permanent magnet will affect the Curie ferromagnet, and the analysis seems to become complicated. But the mobile permanent magnet also does magnetization work on the Curie ferromagnet. According to the principle of electromagnetic superposition, the electromagnetic influences between objects are independent of each other, so this additional magnetization work can be analyzed separately. As shown in

Figure 5, the same analysis method shows that after one cycle of model operation, the work and energy between the mobile permanent magnet and the Curie ferromagnet are mutually converted, and the cumulative magnetization work of the mobile permanent magnet on the Curie ferromagnet is also zero. Only for this energy conversion, energy conservation is obeyed. Therefore, the remaining non-zero mechanical work is still

, contradicting energy conservation.

It can be seen that the shape of the Curie ferromagnetic material in

Figure 5 has been modified to a cylindrical configuration. This adjustment was made because the actual simulation in the

Figure 1a model—where the movable ferromagnetic material was replaced with a permanent magnet—demonstrated poor shielding performance. The reason lies in the Curie ferromagnetic material acting as a conductor of the magnetic field. By reshaping it into a cylinder, intermittent magnetic field conduction was achieved, effectively replicating the behavior of a non-conservative field with enhanced efficacy. However, this geometric alteration caused a functional shift: in its normal ferromagnetic state, the Curie material transitioned from shielding to magnetic conduction. The cylindrical shielding structure weakened the magnetic flux density in the right-side region, whereas the cylindrical conduction mechanism significantly increased the magnetic flux density in the same area. Notably, achieving non-zero mechanical work from the mobile permanent magnet required its reverse motion.

8. The Fundamental Cause of Changes in the Internal Energy of an Object Is Magnetization Work, Which Has No Causal Relationship with Magnetic Force Work

Further analyzing the reason for the non-zero mechanical work generated during the phase transition process of the model, it can also be considered that the magnetization work generated by the magnetic field during the Curie ferromagnet phase transition process and the magnetic force work generated by the magnetic field on the mobile ferromagnet do not have a necessary causal relationship. For example, in

Figure 2a, the Curie ferromagnet phase transition process continuously generates magnetization work, but no magnetic force work is produced; another example is the approaching process of the mobile ferromagnet, which produces magnetic force work, but does not generate magnetization work on the Curie ferromagnet in the Curie state; and if the permanent magnet moves away or approaches when the Curie ferromagnet is in the ferromagnetic state, then magnetization work and magnetic force work occur simultaneously. Therefore, magnetization work and magnetic force work do not necessarily appear simultaneously, and it cannot be simply considered that when both occur simultaneously, it is mutual energy conversion. This shows that the generation of magnetic force work is not caused by the consumption of equivalent heat by the magnetization work. Clarifying the relationship between the two leads to a further understanding of the reason why the model obtains non-zero mechanical work.

This research is mainly based on theoretical derivation and simulation analysis. Experimental verification requires precise detection of the thermodynamic heat of objects due to magnetic field changes, which is difficult and will be the focus of subsequent work. Placing the Curie ferromagnet of

Figure 2b into the adiabatic box of

Figure 3 can serve as an experimental scheme. Run the model without the mobile ferromagnet and the complete model separately for a sufficient number of times, and statistically analyze the cumulative position changes when the piston recovers, thereby judging the heat changes inside the adiabatic box. Compare the changes of the two; if the changes are the same, it indicates that the mobile ferromagnet has no energy impact on the adiabatic box system, which fully proves the theory of this paper correct.

9. Factors Such as Hysteresis Effects Do Not Truly Reduce Energy but only Cause Changes in Entropy

When the Curie ferromagnet transitions to the normal state, it becomes a ferromagnet, and there will be a hysteresis effect when the magnetic field is removed, but after heating to restore the Curie state, all hysteresis disappears. In practice, the remanence of ferromagnets is eliminated by heating. The temperature change of the Curie ferromagnet phase transition requires external repeated heating and cooling. Through adiabatic phase transition, thermal dissipation is minimized. The volume change occurring during the Curie ferromagnet phase transition does not exchange work with the external environment, belonging to virtual work, and after the phase transition cycle returns to the initial state, the cumulative volume work is also zero, so it does not need to be considered in the analysis.

The above factors can all be reduced by process technology. Problems that can be solved by process technology can be continuously reduced by improvement, so they can be completely temporarily not considered in theoretical qualitative analysis.

10. Conclusions

This paper analyzes the internal energy of the phase transition system in a Curie phase transition shielding model based on the theories of Curie phase transition and magnetic medium thermodynamics. The result shows that after the model completes one phase transition cycle, the cumulative magnetization work on the Curie ferromagnet is zero, and the internal energy of both the adiabatic phase transition system and the entire model is conserved. However, the moving ferromagnet gains non-zero mechanical work, causing the energy of the entire model to no longer be conserved, which contradicts the law of conservation of energy. This discovery indicates that there are exceptions to the conservation of energy, and it is not absolute.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Cui Haining, Theory of Thermodynamic Systems, Changchun, Jilin University Press, 2009, pp. 274-275.

- J. M. D. Coey, Magnetism and Magnetic Materials,Cambridge University Press, 2010,50-56.

- Vladimir Kozhevnikov, Thermodynamics of Magnetizing Materials and Superconductors, CRC Press, 2019, Chapter 1, 6-7.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).