Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

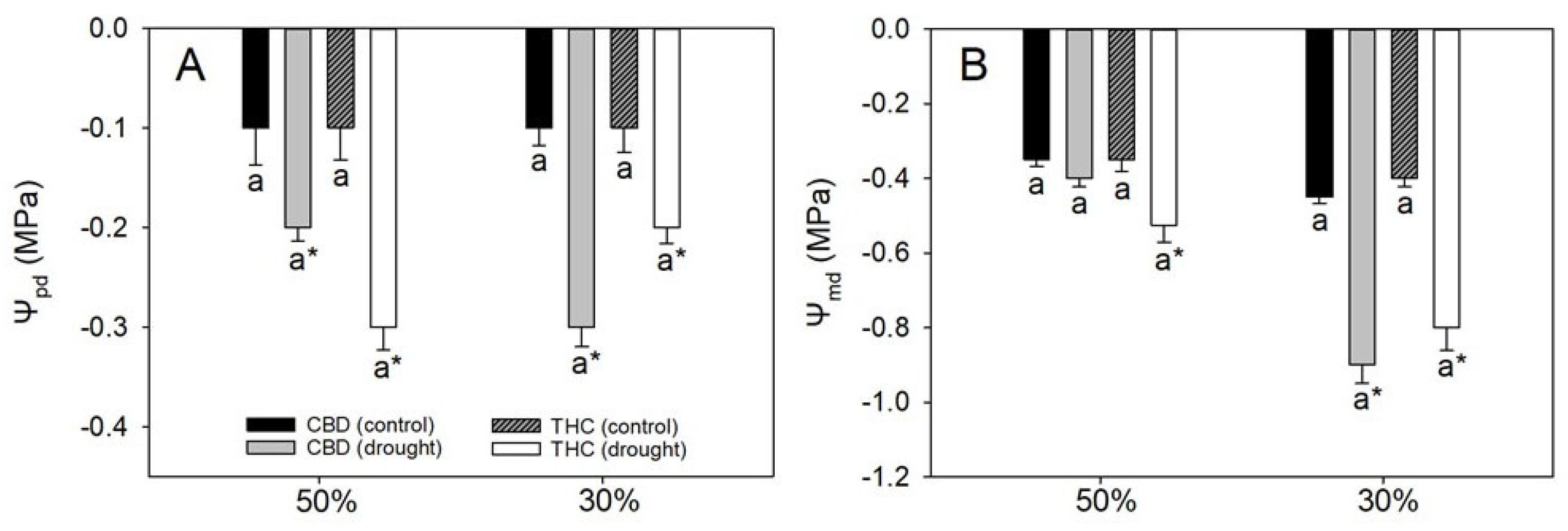

3.1. Stable Leaf Water Relations Fail to Explain Divergence in Growth and Photosynthetic Performance

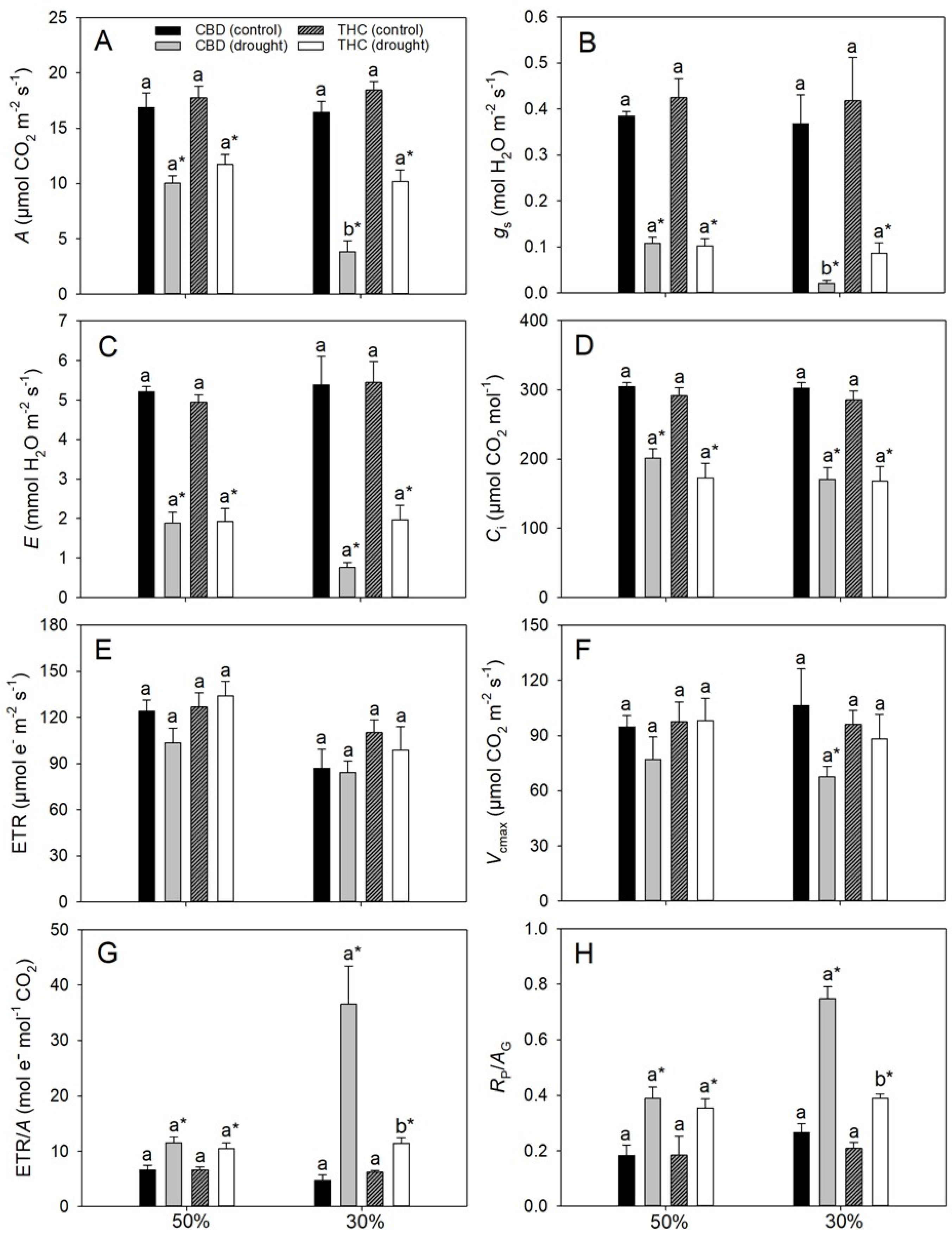

3.2. Contrasting Stomatal Versus Non-Stomatal Limitations Reveal Divergent Strategies of Photosynthetic Response to Drought

3.3. Failure to Upregulate Photoprotective Pathways Enhances Photosynthesis Photoinhibition and Oxidative Stress During Water Deficit

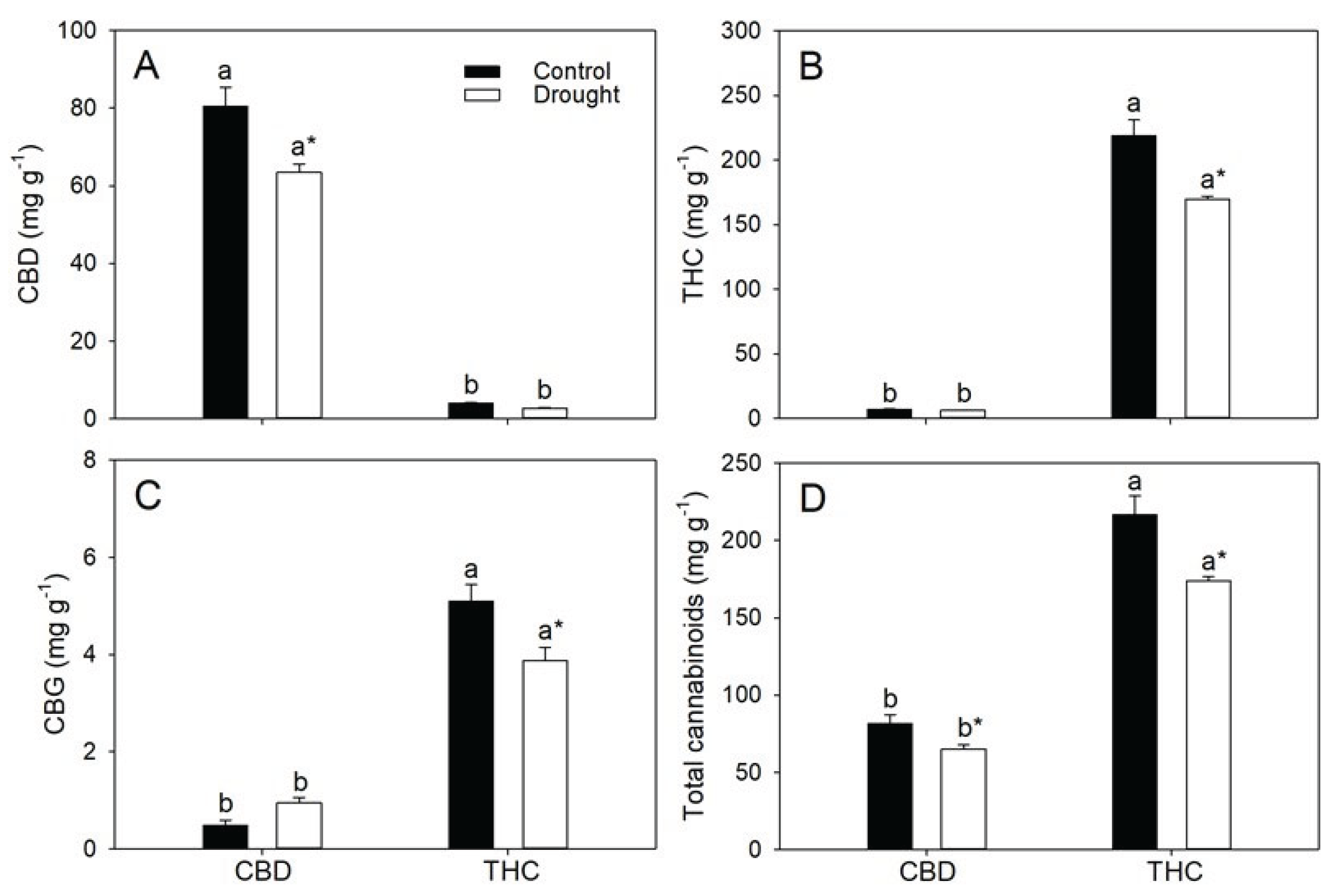

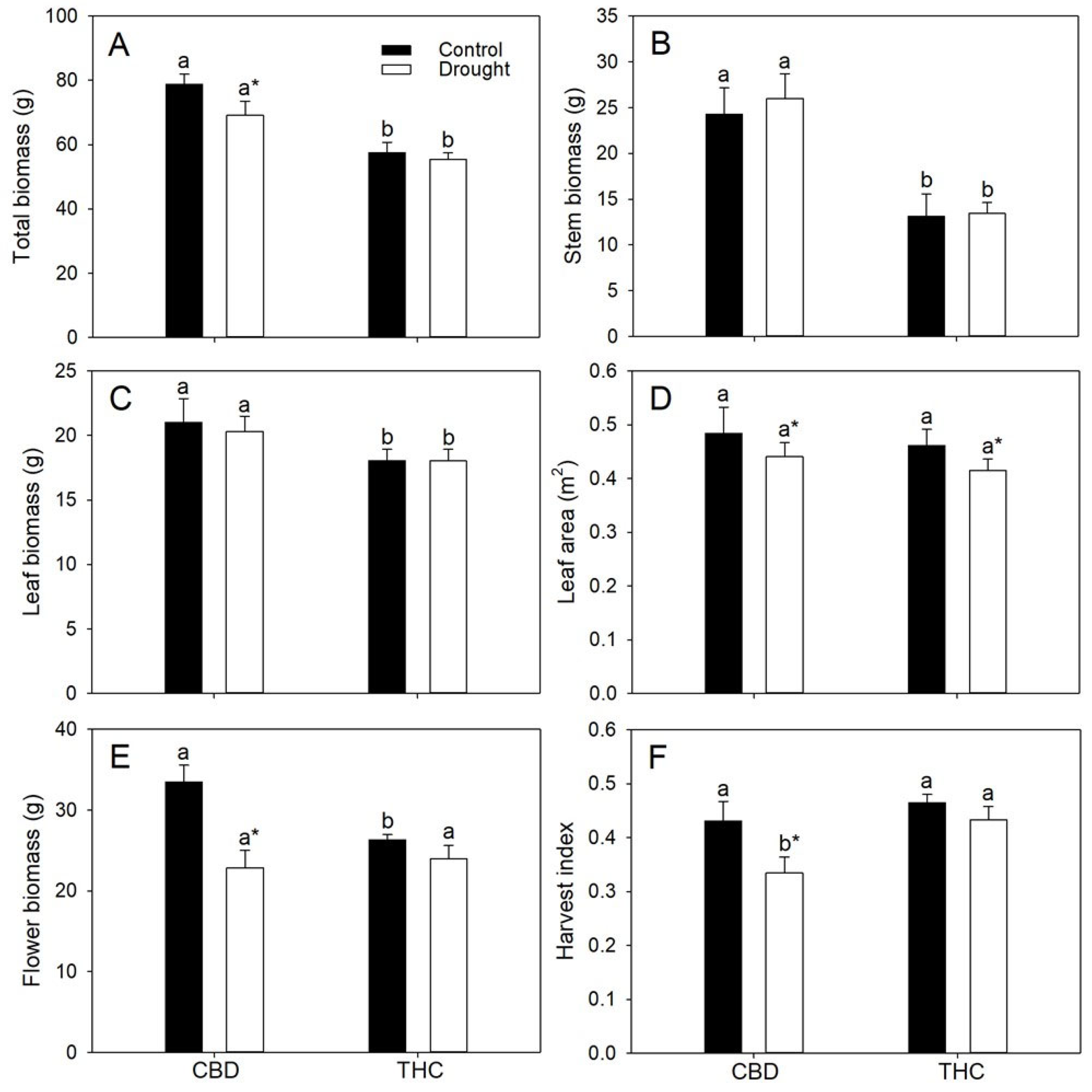

3.4. Genotypic Differences in Photosynthesis, Biomass Partitioning and Cannabinoid Yield Determine Agronomic and Energetic Returns Under Varying Water Availability

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material, Experimental Design, and Analytical Procedures

4.2. Leaf Water Potential and Pressure–Volume Curves

4.3. Gas Exchange and Chlorophyll Fluorescence

4.4. Biochemical and Cannabinoid Analyses

4.5. Growth Traits

4.6. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujita, D.; Basra, S.M.A. Plant drought stress: Effects, mechanisms and management. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Mir, R.A.; Haque, M.A.; Danishuddin; Almalki, M. A.; Alfredan, M.; Khalifa, A.; Mahmoudi, H.; Shahid, M.; Tyagi, A.; Mir, Z.A. Exploring physiological and molecular dynamics of drought stress responses in plants: Challenges and future directions. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1565635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukarram, M.; Choudhary, S.; Kurjak, D.; Petek, A.; Khan, M.M.A. Drought: Sensing, signalling, effects and tolerance in higher plants. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, H.-B.; Chu, L.-Y.; Jaleel, C.A.; Zhao, C.-X. Water-deficit stress-induced anatomical changes in higher plants. C. R. Biol. 2008, 331, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Flexas, J.; Pinheiro, C. Photosynthesis under drought and salt stress: Regulation mechanisms from whole plant to cell. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, K.J.; Zörb, C.; Geilfus, C.M. Drought and crop yield. Plant Biol. 2021, 23, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, P.J.; Boyer, J.S. Water Relations of Plants and Soils; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Flexas, J.; Díaz-Espejo, A.; Conesa, M.A.; Coopman, R.E.; Douthe, C.; Gago, J.; et al. Mesophyll conductance to CO₂ and Rubisco as targets for improving intrinsic water use efficiency in C₃ plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 965–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, M.; Nisar, M.; Khan, N.; Hazrat, A.; Khan, A.H.; Hayat, K.; Fahad, X.; Khan, A.; Ullah, A. Drought tolerance strategies in plants: A mechanistic approach. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 926–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Medrano, H. Drought-inhibition of photosynthesis in C₃ plants: Stomatal and non-stomatal limitations revisited. Ann. Bot. 2002, 89, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Kunert, K. The ascorbate–glutathione cycle coming of age. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 2682–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, W.-C.; Han, C.; Wang, S.; Bai, M.-Y.; Song, C.-P. Reactive oxygen species: Multidimensional regulators of plant adaptation to abiotic stress and development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 330–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Alberti, T.; Raposo, R.S.; Anterola, A.M.; Weber, J.; Diatta, A.A.; Leme Filho, J.F.C. The effects of water-deficit stress on Cannabis sativa L. development and production of secondary metabolites: A review. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetterman, P.S.; Keith, E.S.; Waller, C.W.; Guerrero, O.; Doorenbos, N.J.; Quimby, M.W. Mississippi-grown Cannabis sativa L.: Preliminary observation on chemical definition of phenotype and variations in tetrahydrocannabinol content versus age, sex, and plant part. J. Pharm. Sci. 1971, 60, 1246–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldon, K.; Shekoofa, A.; Walker, E.; Kelly, H. Physiological screening for drought-tolerance traits among hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) cultivars in controlled environments and in field. J. Crop Improv. 2021, 35, 816–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.R.; Loveys, B.R.; Cowley, J.M.; Hall, T.; Cavagnaro, T.R.; Burton, R.A. Physiological and morphological responses of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) to water deficit. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 187, 115331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, D.; Dixon, M.; Zheng, Y. Increasing inflorescence dry weight and cannabinoid content in medical cannabis using controlled drought stress. HortScience 2019, 54, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Pauli, C.S.; Gostin, E.L.; Staples, S.K.; Seifried, D.; Kinney, C.; Vanden Heuvel, B.D. Effects of short-term environmental stresses on the onset of cannabinoid production in young immature flowers of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). J. Cannabis Res. 2022, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, W.; Singh, J.; Kesheimer, K.; Davis, J.; Sanz-Saez, A. Identifying physiological traits related with drought tolerance and water-use efficiency in floral hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Crop Sci. 2024, 64, 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, S.L.; Riggi, E.; Testa, G.; Scordia, D.; Copani, V. Evaluation of European developed fibre hemp genotypes (Cannabis sativa L.) in semi-arid Mediterranean environment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 50, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrechorkos, S.H.; Sheffield, J.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Funk, C.; Miralles, D.G.; Peng, J.; et al. Warming accelerates global drought severity. Nature 2025, 642, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.K.; Scoffoni, C.; Sack, L. The determinants of leaf turgor loss point and prediction of drought tolerance of species and biomes: A global meta-analysis. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, A. Osmotic adjustment is a prime drought stress adaptive engine in support of plant production. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.G.; Dumbroff, E.B. Turgor regulation via cell wall adjustment in white spruce. Plant Physiol. 1999, 119, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago, J.; Daloso, D.M.; Carriquí, M.; Nadal, M.; Morales, M.; Araújo, W.L.; et al. The photosynthesis game is in the “interplay”: Mechanisms underlying CO₂ diffusion in leaves. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 178, 104174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.C.V.; Galmés, J.; Molins, A.; DaMatta, F.M. Improving the estimation of mesophyll conductance to CO2: On the role of electron transport rate correction and respiration. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3285–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marçal, D.M.; Avila, R.T.; Quiroga-Rojas, L.F.; de Souza, R.P.; Junior, C.C.G.; Ponte, L.R.; et al. Elevated [CO2] benefits coffee growth and photosynthetic performance regardless of light availability. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 158, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, D.M.; Johnson, G.; Kiirats, O.; Edwards, G.E. New fluorescence parameters for the determination of QA redox state and excitation energy fluxes. Photosynth. Res. 2004, 79, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingler, A.; Lea, P.J.; Quick, W.P.; Leegood, R.C. Photorespiration: Metabolic pathways and their role in stress protection. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2000, 355, 1517–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos-González, L.; Alarcón, N.; Bastías, R.; Pérez, C.; Sanz, R.; Peña-Neira, Á.; Pastenes, C. Photoprotection is achieved by photorespiration and modification of the leaf incident light, and their extent is modulated by the stomatal sensitivity to water deficit in grapevines. Plants 2022, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P.; Li, X.P.; Niyogi, K.K. Non-photochemical quenching: A response to excess light energy. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 1558–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E.H.; Lawson, T. Chlorophyll fluorescence analysis: A guide to good practice and understanding some new applications. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3983–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, N.R.; Rosenqvist, E. Applications of chlorophyll fluorescence can improve crop production strategies: An examination of future possibilities. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 1607–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, J.; Wang, Y.; Chi, Y.; Zhou, L.; Chen, J.; Zhou, W.; et al. Drought stress strengthens the link between chlorophyll fluorescence parameters and photosynthetic traits. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, T. Transition from vegetative to reproductive phase. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2001, 4, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.K.; Bhargava, S.C.; Goel, A. Energy as the basis of harvest index. J. Agric. Sci. 1982, 99, 237–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.L.; Cox, M.M. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 7th ed.; W.H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, M.; Hong, C.; Jiao, Y.; Hou, S.; Gao, H. Impacts of drought on photosynthesis in major food crops and the related mechanisms of plant responses to drought. Plants 2024, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavatte, P.C.; Oliveira, A.A.; Morais, L.E.; Martins, S.C.; Sanglard, L.M.; DaMatta, F.M. Could shading reduce the negative impacts of drought on coffee? A morphophysiological analysis. Physiol. Plant. 2012, 144, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyree, M.T.; Hammel, H.T. The measurement of the turgor pressure and the water relations of plants by the pressure-bomb technique. J. Exp. Bot. 1972, 23, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, C.J.; Brodribb, T.J. Two measures of leaf capacitance: Insights into the water transport pathway and hydraulic conductance in leaves. Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaMatta, F.M.; Godoy, A.G.; Menezes-Silva, P.E.; Martins, S.C.V.; Sanglard, L.M.V.P.; Morais, L.E.; et al. Sustained enhancement of photosynthesis in coffee trees grown under free-air CO₂ enrichment conditions: Disentangling the contributions of stomatal, mesophyll, and biochemical limitations. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.; Johnson, G.N. Chlorophyll fluorescence—A practical guide. J. Exp. Bot. 2000, 51, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, J.; Grace, J.; Miranda, A.; Meir, P.; Wong, S.; Miranda, H.; et al. A simple calibrated model of Amazon rainforest productivity based on leaf biochemical properties. Plant Cell Environ. 1995, 18, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, R.; Epron, D.; De Angelis, P.; Matteucci, G.; Dreyer, E. In situ estimation of net CO₂ assimilation, photosynthetic electron flow and photorespiration in Quercus cerris leaves: Diurnal cycles under different levels of water supply. Plant Cell Environ. 1995, 18, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kauwe, M.G.; Lin, Y.S.; Wright, I.J.; Medlyn, B.E.; Crous, K.Y.; Ellsworth, D.S.; et al. A test of the “one-point method” for estimating maximum carboxylation capacity from field-measured, light-saturated photosynthesis. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Caemmerer, S.; Evans, J.R.; Hudson, G.S.; Andrews, T.J.; Seemann, J.R. The kinetics of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in vivo inferred from measurements of photosynthesis in leaves of transgenic tobacco. Planta 1994, 195, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, T.D.; Bernacchi, C.J.; Farquhar, G.D.; Singsaas, E.L. Fitting photosynthetic carbon dioxide response curves for C₃ leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 1035–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisec, J.; Schauer, N.; Kopka, J.; Willmitzer, L.; Fernie, A.R. Gas chromatography mass spectrometry–based metabolite profiling in plants. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender-Machado, L.; Bauerlein, M.; Carrari, F.; Schauer, N.; Lytovchenko, A.; Gibon, Y.; et al. Expression of a yeast acetyl CoA hydrolase in the mitochondrion of tobacco plants inhibits growth and restricts photosynthesis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2004, 55, 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernie, A.R.; Roscher, A.; Ratcliffe, R.G.; Kruger, N.J. Fructose 2,6-bisphosphate activates pyrophosphate: Fructose 6 phosphate 1-phosphotransferase and increases triose phosphate to hexose phosphate cycling in heterotrophic cells. Planta 2001, 212, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemm, E.W.; Cocking, E.C.; Ricketts, R.E. The determination of amino-acids with ninhydrin. Analyst 1955, 80, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieleski, R.L.; Turner, N.A. Separation and estimation of amino acids in crude plant extracts by thin-layer electrophoresis and chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 1966, 17, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillo, P.; Gibon, Y. Protocol: Extraction and determination of proline. PrometheusWiki 2011, 2011, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praxedes, S.C.; DaMatta, F.M.; Loureiro, M.E.; Maria, M.A.; Cordeiro, A.T. Effects of long-term soil drought on photosynthesis and carbohydrate metabolism in mature robusta coffee (Coffea canephora Pierre var. kouillou) leaves. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2006, 56, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.M.; DeLong, J.M.; Forney, C.F.; Prange, R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, M. Commentary to: “Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds” by Hodges et al., Planta (1999) 207, 604–611. Planta 2017, 245, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, P.H.P.; Cambraia, J.; Sant’Anna, R.; Mosquim, P.R.; Moreira, M.A. Aluminum effects on lipid peroxidation and on the activities of enzymes of oxidative metabolism in sorghum. Rev. Bras. Fisiol. Veg. 1999, 11, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutases: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havir, E.A.; McHale, N.A. Biochemical and developmental characterization of multiple forms of catalase in tobacco leaves. Plant Physiol. 1987, 84, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, S.S.; Lee, M.S.; Park, I.H.; Kim, I.J.; Liu, J.R. Enhancement of peroxidase activity by stress-related chemicals in sweet potato. Phytochemistry 1996, 43, 565–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarén, C.; Zambrana, P.C.; Pérez-Roncal, C.; López-Maestresalas, A.; Ábrego, A.; Arazuri, S. Potential of NIRS technology for the determination of cannabinoid content in industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Agronomy 2022, 12, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, H.; Hartung, J.; Schober, T.; Vogt, M.M.; Carrera, D.A.; Ruckle, M.; Graeff-Hönninger, S. Non-destructive near-infrared technology for efficient cannabinoid analysis in cannabis inflorescences. Plants 2024, 13, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | CBD | THC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Drought | Control | Drought | |

| Ψs(100) (MPa) | -0.73 ± 0.12a | -0.62 ± 0.06a | -1.08 ± 0.17a | -0.69 ± 0.05a |

| Ψs(0) (MPa) | -1.23 ± 0.19a | -1.13 ± 0.08a | -1.50 ± 0.15a | -1.08 ± 0.06a |

| ε (MPa) | 5.77 ± 1.12a | 4.49 ± 0.48a | 6.75 ± 1.21a | 5.82 ± 0.62a |

| C(100) (mol m-2 MPa-1) | 0.09 ± 0.02a | 0.11 ± 0.01a | 0.09 ± 0.01a | 0.09 ± 0.01a |

| C(0) (mol m-2 MPa-1) | 0.11 ± 0.02b | 0.11 ± 0.01a | 0.22 ± 0.03a | 0.11 ± 0.02a* |

| Parameters | CBD | THC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Drought | Control | Drought | |

| Fv/Fm | 0.81 ± 0.01a | 0.64 ± 0.01a* | 0.83 ± 0.01a | 0.68 ± 0.02a* |

| F0 | 626 ± 18a | 950 ± 72a* | 554 ± 19a | 922 ± 98a* |

| qL | 0.46 ± 0.02a | 0.19 ± 0.01a* | 0.44 ± 0.03a | 0.12 ± 0.07a* |

| NPQ | 0.96 ± 0.08b | 0.58 ± 0.07b* | 1.74 ± 0.28a | 1.15 ± 0.14a* |

| Parameters | CBD | THC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Drought | Control | Drought | |

| SOD (U min-1 mg-1 protein) | 26.43 ± 1.9a | 16.73 ± 1.2a* | 19.85 ± 1.5a | 9.23 ± 0.6b* |

| CAT (µmol H2O2 min-1 mg-1 protein) | 17.5 ± 1.3a | 14.1 ± 0.9a* | 12.4 ± 0.7a | 8.7 ± 0.5a* |

| POX (µmol purpurogalin min-1 mg-1 protein) | 0.10 ± 0.01a | 0.03 ± 0.01a* | 0.04 ± 0.01b | 0.03 ± 0.01a |

| MDA (µmol g-1 DW) | 0.95 ± 0.09a | 1.24 ± 0.06a* | 1.16 ± 0.05a | 1.50 ± 0.09a* |

| Parameters | CBD | THC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Drought | Control | Drought | |

| Chlorophylls a+b (μg g-1) | 2807 ± 133a | 1759 ± 131b* | 2813 ± 35a | 2320 ± 77a* |

| Carotenoids (μg g-1) | 735 ± 20a | 437 ± 33a* | 715 ± 9a | 522 ± 22a* |

| Glucose (μmol g-1) | 87 ± 10a | 55 ± 3a* | 84 ± 6a | 55 ± 4a* |

| Fructose (μmol g-1) | 30 ± 3a | 24 ± 3a* | 38 ± 5a | 29 ± 2a* |

| Sucrose (μmol g-1) | 93 ± 7b | 73 ± 3b* | 107 ± 2a | 82 ± 2a* |

| Starch (mmol equiv. glucose g-1) | 0.90 ± 0.09a | 0.73 ± 0.06a* | 0.60 ± 0.07b | 0.42 ± 0.07b* |

| Amino acids (μmol g-1) | 43 ± 2a | 30 ± 2a* | 44 ± 1a | 32 ± 2a* |

| Phenolics (mg g-1) | 113 ± 3a | 102 ± 6a | 89 ± 2b | 91 ± 4b |

| Proline (μmol g-1) | 9.81 ± 0.5a | 8.69 ± 0.5a | 10.05 ± 1.0a | 7.72 ± 0.5a* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).