Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

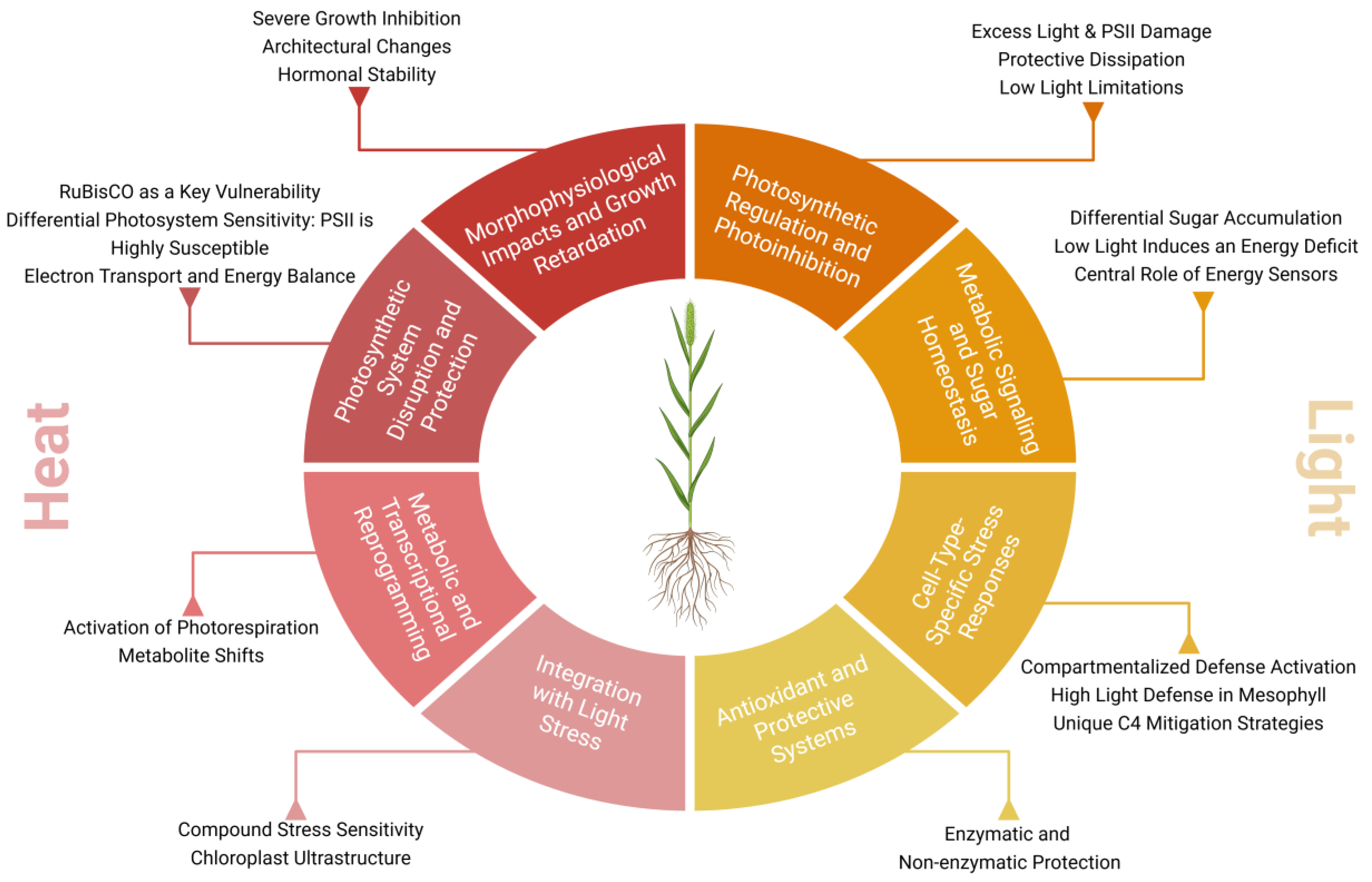

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

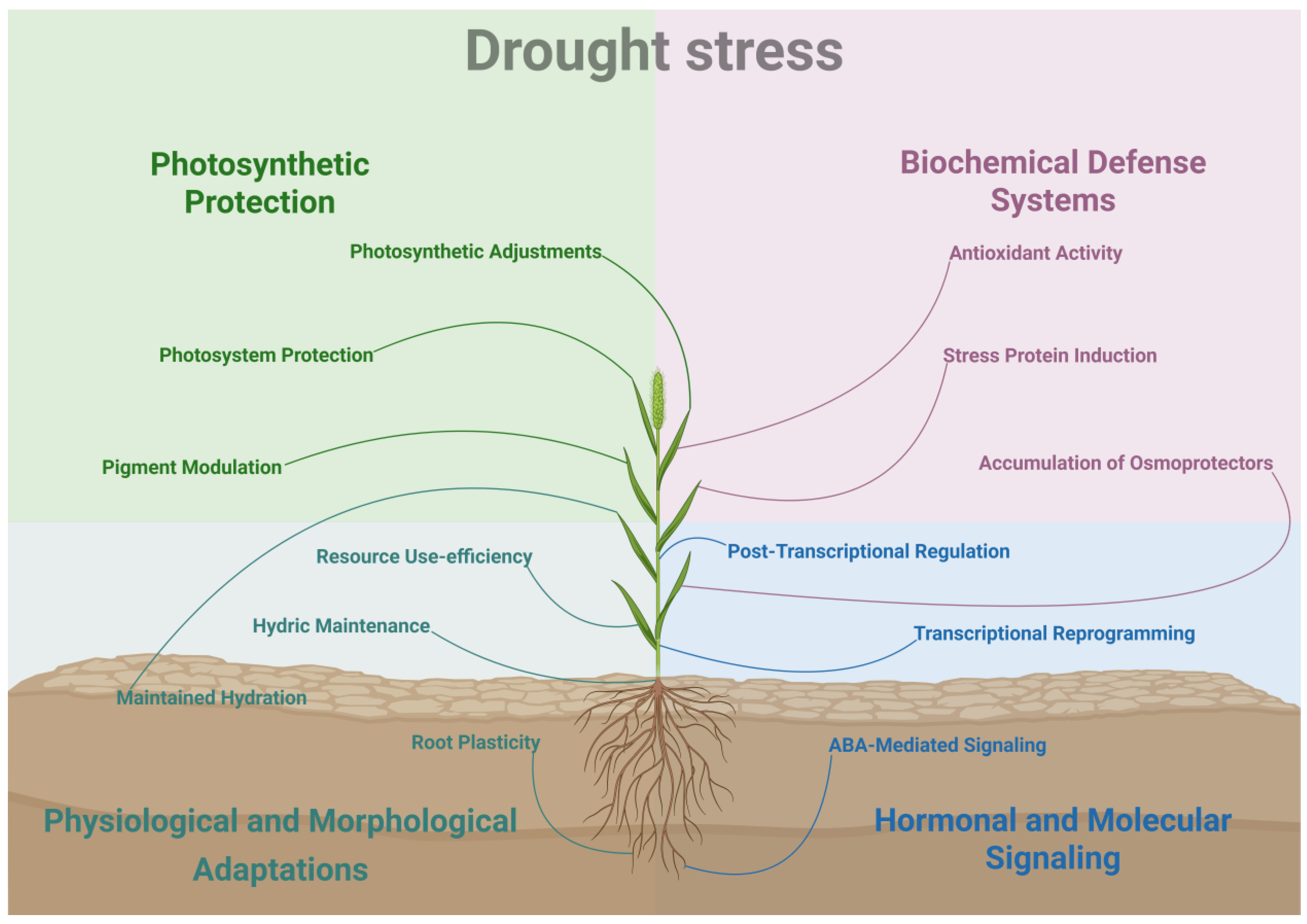

2. Drought Stress

3. Heat Stress

4. Light Stress

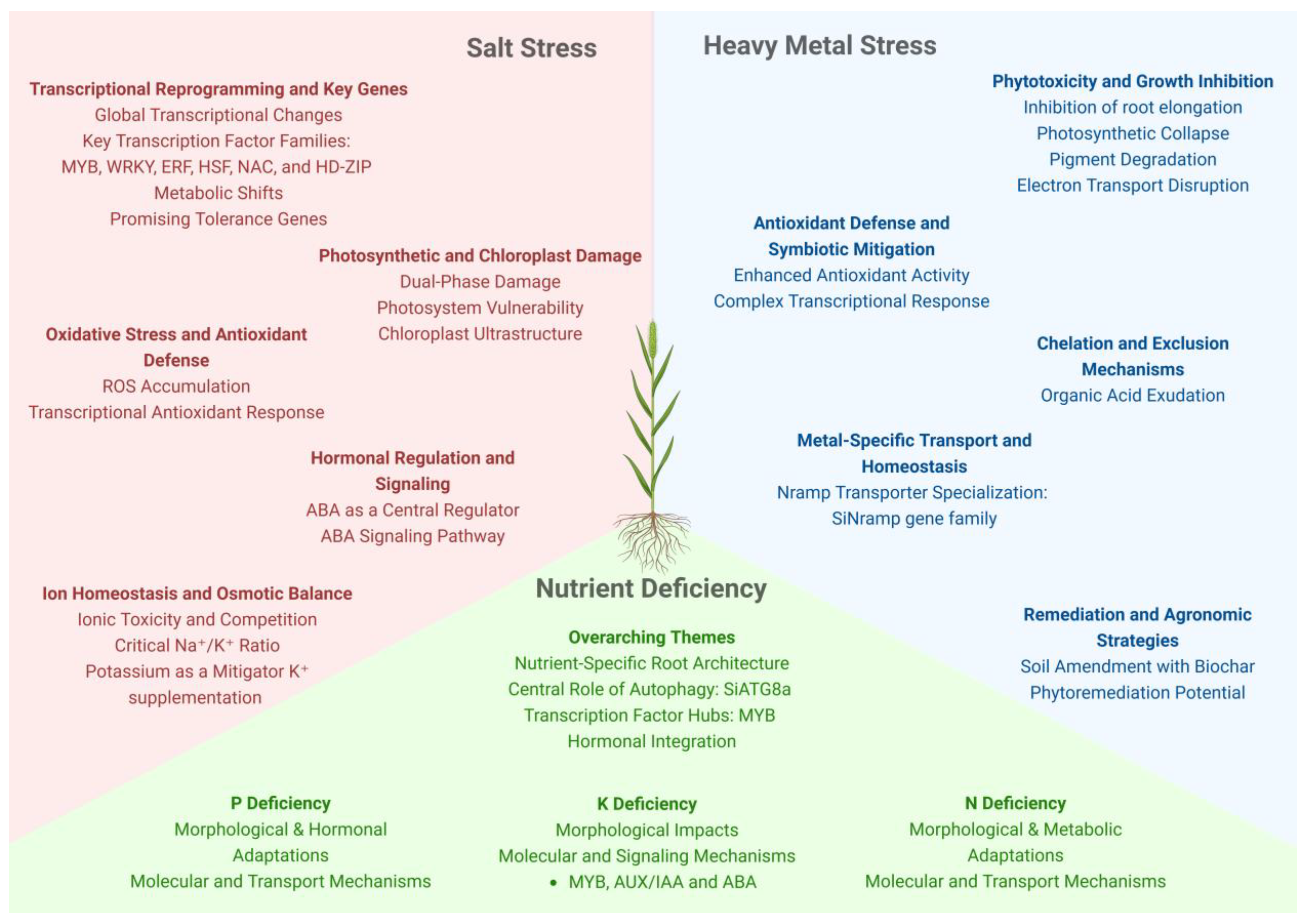

5. Salt Stress

6. Nutrient Deficiency

7. Heavy Metals

8. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knutti, R.; Rogelj, J.; Sedlácek, J.; Fischer, E.M. A Scientific Critique of the Two-Degree Climate Change Target. Nat Geosci 2016, 9, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coustenis, A.; Taylor, F.W.; Plainaki, C. Climate Issues from the Planetary Perspective and Insights for the Earth. In Global Change and Future Earth; Cambridge University Press; pp. 40–54.

- Govindan, K. Sustainable Consumption and Production in the Food Supply Chain: A Conceptual Framework. Int J Prod Econ 2018, 195, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abberton, M.; Batley, J.; Bentley, A.; Bryant, J.; Cai, H.; Cockram, J.; Costa de Oliveira, A.; Cseke, L.J.; Dempewolf, H.; De Pace, C.; et al. Global Agricultural Intensification during Climate Change: A Role for Genomics. Plant Biotechnol J 2016, 14, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Change 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Oshunsanya, S.O.; Nwosu, N.J.; Li, Y. Abiotic Stress in Agricultural Crops Under Climatic Conditions. In Sustainable Agriculture, Forest and Environmental Management; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2019; pp. 71–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, L.; Chhogyel, N.; Gopalakrishnan, T.; Hasan, M.K.; Jayasinghe, S.L.; Kariyawasam, C.S.; Kogo, B.K.; Ratnayake, S. Climate Change and Future of Agri-Food Production. In Future Foods; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 49–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ghadirnezhad Shiade, S.R.; Fathi, A.; Taghavi Ghasemkheili, F.; Amiri, E.; Pessarakli, M. Plants’ Responses under Drought Stress Conditions: Effects of Strategic Management Approaches—a Review. J Plant Nutr 2023, 46, 2198–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seikh, T.A.; Liontou, P.; Korres, N.E. The Response of Weeds under Abiotic Stress as a Tool for Green Strategies in Agriculture; 2025; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zandalinas, S.I.; Sengupta, S.; Fritschi, F.B.; Azad, R.K.; Nechushtai, R.; Mittler, R. The Impact of Multifactorial Stress Combination on Plant Growth and Survival. New Phytologist 2021, 230, 1034–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Singh Sidhu, G.P.; Bali, A.S.; Handa, N.; Kapoor, D.; Yadav, P.; Khanna, K.; et al. Photosynthetic Response of Plants Under Different Abiotic Stresses: A Review. J Plant Growth Regul 2020, 39, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszczak, C.; Carmody, M.; Kangasjärvi, J. Reactive Oxygen Species in Plant Signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2018, 69, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.; Mahmud, J.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Abiotic Stress: Revisiting the Crucial Role of a Universal Defense Regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnola, A.; Bassi, R. Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Plant Photoprotection. Biochem Soc Trans 2018, 46, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, J.; Prathibha, M.; Singh, P.; Choyal, P.; Mishra, U.N.; Saha, D.; Kumar, R.; Anuragi, H.; Pandey, S.; Bose, B.; et al. Plant Photosynthesis under Abiotic Stresses: Damages, Adaptive, and Signaling Mechanisms. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opoku, E.; Sahu, P.P.; Findurová, H.; Holub, P.; Urban, O.; Klem, K. Differential Physiological and Production Responses of C3 and C4 Crops to Climate Factor Interactions. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monson, R.K.; Li, S.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Fan, Y.; Hodge, J.G.; Knapp, A.K.; Leakey, A.D.B.; Lombardozzi, D.; Reed, S.C.; Sage, R.F.; et al. <scp> C 4 </Scp> Photosynthesis, Trait Spectra, and the Fast-efficient Phenotype. New Phytologist 2025, 246, 879–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stainbrook, S.C.; Aubuchon, L.N.; Chen, A.; Johnson, E.; Si, A.; Walton, L.; Ahrendt, A.J.; Strenkert, D.; Jez, J.M. C4 Grasses Employ Distinct Strategies to Acclimate Rubisco Activase to Heat Stress. Biosci Rep 2024, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Sui, N. Sensitivity and Responses of Chloroplasts to Salt Stress in Plants. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutnell, T.P.; Wang, L.; Swartwood, K.; Goldschmidt, A.; Jackson, D.; Zhu, X.-G.; Kellogg, E.; Van Eck, J. Setaria viridis: A Model for C4 Photosynthes. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2537–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Brutnell, T.P. Setaria viridis and Setaria italica, Model Genetic Systems for the Panicoid Grasses. J Exp Bot 2011, 62, 3031–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennetzen, J.L.; Schmutz, J.; Wang, H.; Percifield, R.; Hawkins, J.; Pontaroli, A.C.; Estep, M.; Feng, L.; Vaughn, J.N.; Grimwood, J.; et al. Reference Genome Sequence of the Model Plant Setaria. Nat Biotechnol 2012, 30, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, J. The Status of Setaria viridis Transformation: Agrobacterium-Mediated to Floral Dip. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, T.; Wang, C.; Kang, X.; Zhao, H.; Elena Gamo, M.; Starker, C.G.; Crisp, P.A.; Zhou, P.; Springer, N.M.; Voytas, D.F.; et al. Optimization of Multiplexed CRISPR/Cas9 System for Highly Efficient Genome Editing in Setaria viridis. The Plant Journal 2020, 104, 828–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Mauro-Herrera, M.; Doust, A.N. Domestication and Improvement in the Model C4 Grass, Setaria. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Yu, S.; Chen, X. Charring-Induced Morphological Changes of Chinese “Five Grains”: An Experimental Study. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Muthamilarasan, M.; Prasad, M. Foxtail Millet: An Introduction; 2017; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, X.; Jia, G. Foxtail Millet Germplasm and Inheritance of Morphological Characteristics; 2017; pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, J. The Foxtail (Setaria) Species-Group. Weed Sci 2003, 51, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, J.; Yee, M.-C.; Goudinho Viana, W.; Rellán-Álvarez, R.; Feldman, M.; Priest, H.D.; Trontin, C.; Lee, T.; Jiang, H.; Baxter, I.; et al. Grasses Suppress Shoot-Borne Roots to Conserve Water during Drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 8861–8866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Sade, N.; Arzani, A.; Rubio Wilhelmi, M. del M.; Coe, K.M.; Li, B.; Blumwald, E. Effects of Abiotic Stress on Physiological Plasticity and Water Use of Setaria viridis (L.). Plant Science 2016, 251, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro-Herrera, M.; Doust, A.N. Development and Genetic Control of Plant Architecture and Biomass in the Panicoid Grass, Setaria. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0151346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Cao, X.; Li, H.; Cui, X.; Diao, X.; Qiao, Z. Genomic Analysis of Hexokinase Genes in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica): Haplotypes and Expression Patterns Under Abiotic Stresses. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supriya, L.; Shukla, P.; Dake, D.; Gudipalli, P.; Muthamilarasan, M. Physio-Biochemical and Molecular Analyses Decipher Distinct Dehydration Stress Responses in Contrasting Genotypes of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.). J Plant Physiol 2025, 311, 154549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Ge, W.; Bai, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, L.; Li, J.; Shen, J.; Xu, N.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Leaves and Roots during Drought Stress and Recovery in Setaria italica L. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unknown The Impact of Disasters and Crises on Agriculture and Food Security: 2021; FAO, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-134071-4.

- Gupta, A.; Rico-Medina, A.; Caño-Delgado, A.I. The Physiology of Plant Responses to Drought. Science (1979) 2020, 368, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhi, H.; Li, Y.; Guo, E.; Feng, G.; Tang, S.; Guo, W.; Zhang, L.; Jia, G.; Diao, X. Response of Multiple Tissues to Drought Revealed by a Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis in Foxtail Millet [Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv.]. Front Plant Sci 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Duan, Y.; Xing, Q.; Duan, R.; Shen, J.; Zong, Y.; Zhang, D.; Shi, X.; Li, P.; Hao, X. Elevated CO2 Concentration Enhances Drought Tolerance by Mitigating Oxidative Stress and Enhancing Carbon Assimilation in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica). J Agron Crop Sci 2024, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Sade, N.; Arzani, A.; Rubio Wilhelmi, M. del M.; Coe, K.M.; Li, B.; Blumwald, E. Effects of Abiotic Stress on Physiological Plasticity and Water Use of Setaria viridis (L.). Plant Science 2016, 251, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valença, D. da C.; de Moura, S.M.; Travassos-Lins, J.; Alves-Ferreira, M.; Medici, L.O.; Ortiz-Silva, B.; Macrae, A.; Reinert, F. Physiological and Molecular Responses of Setaria viridis to Osmotic Stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2020, 155, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Gong, X.; Zhang, W.; Hu, Y.; Yang, T.; Dong, K.; Feng, B. Proteomic Changes in the Grains of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica (L.) Beau) under Drought Stress. Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2019, 17, e0802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Cheng, J.; Wen, X.; Wang, J.; Shi, G.; Yao, J.; Hou, L.; Sun, Q.; Xiang, P.; Yuan, X.; et al. Transcriptomic Studies Reveal a Key Metabolic Pathway Contributing to a Well-Maintained Photosynthetic System under Drought Stress in Foxtail Millet ( Setaria italica L.). PeerJ 2018, 6, e4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travassos-Lins, J.; de Oliveira Rocha, C.C.; de Souza Rodrigues, T.; Alves-Ferreira, M. Evaluation of the Molecular and Physiological Response to Dehydration of Two Accessions of the Model Plant Setaria viridis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2021, 169, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cal, A.J.; Sanciangco, M.; Rebolledo, M.C.; Luquet, D.; Torres, R.O.; McNally, K.L.; Henry, A. Leaf Morphology, Rather than Plant Water Status, Underlies Genetic Variation of Rice Leaf Rolling under Drought. Plant Cell Environ 2019, 42, 1532–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, J.C.; Cruz, R.T.; Singh, T.N. Leaf Rolling and Transpiration. Plant Sci Lett 1979, 16, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Hao, D.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Yang, P.; Zhang, B. Comparative Transcriptomics Reveals Key Genes Contributing to the Differences in Drought Tolerance among Three Cultivars of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica). Plant Growth Regul 2023, 99, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T. de S.; Lins, J.T.; Cattem, M.V.; Jardim, V.C.; Buckeridge, M.S.; Grossi-de-Sá, M.F.; Reinert, F.; Alves-Ferreira, M. Evaluation of Setaria viridis Physiological and Gene Expression Responses to Distinct Water-Deficit Conditions. Biotechnology Research and Innovation 2019, 3, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, C.; Chaves, M.M. Photosynthesis and Drought: Can We Make Metabolic Connections from Available Data? J Exp Bot 2011, 62, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, K.E.; Basso, M.F.; de Oliveira, N.G.; da Silva, J.C.F.; de Oliveira Garcia, B.; Cunha, B.A.D.B.; Cardoso, T.B.; Nepomuceno, A.L.; Kobayashi, A.K.; Santiago, T.R.; et al. MicroRNAs Expression Profiles in Early Responses to Different Levels of Water Deficit in Setaria viridis. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2022, 28, 1607–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.J.; Ellsworth, P.Z.; Fahlgren, N.; Gehan, M.A.; Cousins, A.B.; Baxter, I. Components of Water Use Efficiency Have Unique Genetic Signatures in the Model C 4 Grass Setaria. Plant Physiol 2018, 178, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajithkumar, I.P.; Panneerselvam, R. Osmolyte Accumulation, Photosynthetic Pigment and Growth of Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv. under Drought Stress. Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction 2013, 2, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, W.; Zhu, L. Photosynthetic Mechanisms of Carbon Fixation Reduction in Rice by Cadmium and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Environmental Pollution 2024, 344, 123436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, M.M.; Aljabi, H.R.; AL-Huqail, A.A.; Horneburg, B.; Mohammed, A.E.; Alotaibi, M.O. Drought Responses and Adaptation in Plants Differing in Life-Form. Front Ecol Evol 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, L.; Lo Piccolo, E.; Landi, M. Chlorophyll Fluorescence, Photoinhibition and Abiotic Stress: Does It Make Any Difference the Fact to Be a C3 or C4 Species? Front Plant Sci 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Ma, F.; Duan, M.; Zhang, B.; Li, H. The Responses of the Lipoxygenase Gene Family to Salt and Drought Stress in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica). Life 2021, 11, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.; Deng, L.; Yao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Han, Y.; Wang, J. Responses of the Lipoxygenase Gene Family to Drought Stress in Broomcorn Millet (Panicum Miliaceum L.). Genes (Basel) 2025, 16, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Wu, F.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, F.; Xie, H.; Xiao, Y.; et al. OsLOX1 Positively Regulates Seed Vigor and Drought Tolerance in Rice. Plant Mol Biol 2025, 115, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rejeb, K. Ben; Abdelly, C.; Savouré, A. How Reactive Oxygen Species and Proline Face Stress Together. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2014. [CrossRef]

- Rai, G.K.; Khanday, D.M.; Choudhary, S.M.; Kumar, P.; Kumari, S.; Martínez-Andújar, C.; Martínez-Melgarejo, P.A.; Rai, P.K.; Pérez-Alfocea, F. Unlocking Nature’s Stress Buster: Abscisic Acid’s Crucial Role in Defending Plants against Abiotic Stress. Plant Stress 2024, 11, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, I.P.; Schaaf, C.; de Setta, N. Drought Responses in Poaceae: Exploring the Core Components of the ABA Signaling Pathway in Setaria italica and Setaria viridis. Plants 2024, 13, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, K.E.; de Souza, W.R.; Santiago, T.R.; Sampaio, B.L.; Ribeiro, A.P.; Cotta, M.G.; da Cunha, B.A.D.B.; Marraccini, P.R.R.; Kobayashi, A.K.; Molinari, H.B.C. Identification and Characterization of Core Abscisic Acid (ABA) Signaling Components and Their Gene Expression Profile in Response to Abiotic Stresses in Setaria viridis. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Xie, S.; Liu, Y.; Yi, F.; Yu, J. Genome-Wide Annotation of Genes and Noncoding RNAs of Foxtail Millet in Response to Simulated Drought Stress by Deep Sequencing. Plant Mol Biol 2013, 83, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, J.-K. Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants. Nat Rev Genet 2022, 23, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Z.; Li, C.-L.; Zhang, W. WRKY1 Regulates Stomatal Movement in Drought-Stressed Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 2016, 91, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, L.-L.; Xu, Z.-S.; Fu, L.; Pang, H.-X.; Ma, Y.-Z.; Min, D.-H. Genome-Wide Analysis of MADS-Box Genes in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) and Functional Assessment of the Role of SiMADS51 in the Drought Stress Response. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Lan, T. Functional Characterization of the Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) Protein Gene Family from Pinus Tabuliformis (Pinaceae) in Escherichia Coli. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 19467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, Q.; Li, D.; Yang, X.; Li, D. Multifunctional Roles of Plant Dehydrins in Response to Environmental Stresses. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qie, L.; Jia, G.; Zhang, W.; Schnable, J.; Shang, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, B.; Li, M.; Chai, Y.; Zhi, H.; et al. Mapping of Quantitative Trait Locus (QTLs) That Contribute to Germination and Early Seedling Drought Tolerance in the Interspecific Cross Setaria italica×Setaria viridis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamidi, S.; Healey, A.; Huang, P.; Grimwood, J.; Jenkins, J.; Barry, K.; Sreedasyam, A.; Shu, S.; Lovell, J.T.; Feldman, M.; et al. A Genome Resource for Green Millet Setaria viridis Enables Discovery of Agronomically Valuable Loci. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.M.; Knutti, R. Anthropogenic Contribution to Global Occurrence of Heavy-Precipitation and High-Temperature Extremes. Nat Clim Chang 2015, 5, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Abiotic Stress Signaling and Responses in Plants. Cell 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Y.; Mu, X.-R.; Gao, J.; Lin, H.-X.; Lin, Y. The Molecular Basis of Heat Stress Responses in Plants. Mol Plant 2023, 16, 1612–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, F.; Shao, Y.; He, J. Regulatory Mechanisms of Heat Stress Response and Thermomorphogenesis in Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyowati, N.; Lestari, P.; Wawo, A.H. Tracking Optimum Temperature for Germination and Seedling Characterization of Three Millet (Setaria italica) Accessions. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2020, 591, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidoo, M.K.; Bdolach, E.; Fait, A.; Lazarovitch, N.; Rachmilevitch, S. Tolerance to High Soil Temperature in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) Is Related to Shoot and Root Growth and Metabolism. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2016, 106, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowsiga, S.; Vijayalakshmi, D.; Santhosh, G.; Srividhya, S.; Sivakumar, R.; Iyanar, K.; Kokiladevi, E.; Sivakumar, U. Dissecting the Tolerance to Combined Drought and High Temperature Stress in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica ) Using Gas Exchange Response and Plant Water Status. Plant Science Today 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Wang, Y.; Choong, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, Y.; Hsieh, T.-F.; Lin, Y. How Ambient Temperature Affects the Heading Date of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica). Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R, D.; S, P.; Ga, D.; S, K. Effect of Elevated Temperature on Growth Parameters of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica). MADRAS AGRICULTURAL JOURNAL 2019, 106, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X. Antioxidant Defense Response of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Setaria viridis. Pak J Bot 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R, D.; S, P.; Ga, D.; S, K. Effect of Elevated Temperature on Growth Parameters of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica). MADRAS AGRICULTURAL JOURNAL 2019, 106, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowsiga, S.; Vijayalakshmi, D.; Santhosh, G.; Srividhya, S.; Sivakumar, R.; Iyanar, K.; Kokiladevi, E.; Sivakumar, U. Dissecting the Tolerance to Combined Drought and High Temperature Stress in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica ) Using Gas Exchange Response and Plant Water Status. Plant Science Today 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Ren, B.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Z. High Temperature Reduces Photosynthesis in Maize Leaves by Damaging Chloroplast Ultrastructure and Photosystem II. J Agron Crop Sci 2020, 206, 548–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Qiu, H.; Pei, Y.; Hu, S.; Ma, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, M. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of the Infiltration Characteristics of a Loess Landslide. ISPRS Int J Geoinf 2020, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Gentile, B.R.; Xin, Z.; Zhao, D. The Effects of Heat Stress on Male Reproduction and Tillering in Sorghum Bicolor. Food Energy Secur 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocon, K.D.; Luis, P. The Potential of RuBisCO in CO2 Capture and Utilization. Prog Energy Combust Sci 2024, 105, 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, A.K.M.; Orr, D.J.; Carmo-Silva, E. Regulation of Rubisco Activity by Interaction with Chloroplast Metabolites. Biochemical Journal 2024, 481, 1043–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E.H.; McAusland, L.; Burgess, A.J. Abiotic Stress, Acclimation, and Adaptation in Carbon Fixation Processes. In Photosynthesis in Action; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 103–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jespersen, D. Heat Shock Induced Stress Tolerance in Plants: Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Mechanisms of Acquired Tolerance. In Priming-Mediated Stress and Cross-Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicka, B.; Ciura, J.; Szymańska, R.; Kruk, J. Improving Photosynthesis, Plant Productivity and Abiotic Stress Tolerance – Current Trends and Future Perspectives. J Plant Physiol 2018, 231, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, R.A.; Gandin, A.; Cousins, A.B. Temperature Response of C4 Photosynthesis: Biochemical Analysis of Rubisco, Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxylase and Carbonic Anhydrase in Setaria viridis. Plant Physiol 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, E.A.; Kozuleva, M.A.; Klaus, A.A.; Pshybytko, N.L.; Kusnetsov, V. V. Lower Air Humidity Reduced Both the Plant Growth and Activities of Photosystems I and II under Prolonged Heat Stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2023, 194, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, N.; Hafeez, M.B.; Ghaffar, A.; Kausar, A.; Zeidi, M. Al; Siddique, K.H.M.; Farooq, M. Plant Photosynthesis under Heat Stress: Effects and Management. Environ Exp Bot 2023, 206, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, Y. Regulation of Photosynthesis under Stress. In Improving Stress Resilience in Plants; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sack, L.; Holbrook, N.M. LEAF HYDRAULICS. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2006, 57, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Sinclair, T.R.; Zhu, M.; Messina, C.D.; Cooper, M.; Hammer, G.L. Temperature Effect on Transpiration Response of Maize Plants to Vapour Pressure Deficit. Environ Exp Bot 2012, 78, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamori, W. Photosynthesis and Respiration. In Plant Factory; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 197–206. [Google Scholar]

- Nobel, P.S. Temperature and Energy Budgets. In Physicochemical and Environmental Plant Physiology; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 357–407. [Google Scholar]

- Heldt, H.-W.; Piechulla, B. Photosynthesis Is an Electron Transport Process. In Plant Biochemistry; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 63–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, S.; Agrawal, D.; Jajoo, A. Photosynthesis: Response to High Temperature Stress. J Photochem Photobiol B 2014, 137, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirhindi, G.; Mushtaq, R.; Gill, S.S.; Sharma, P.; Abd_Allah, E.F.; Ahmad, P. Jasmonic Acid and Methyl Jasmonate Modulate Growth, Photosynthetic Activity and Expression of Photosystem II Subunit Genes in Brassica Oleracea L. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 9322. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 9322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavafer, A.; Mancilla, C. Concepts of Photochemical Damage of Photosystem II and the Role of Excessive Excitation. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C: Photochemistry Reviews 2021, 47, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka-Nishimura, M.; Yamamoto, Y. Quality Control of Photosystem II: The Molecular Basis for the Action of FtsH Protease and the Dynamics of the Thylakoid Membranes. J Photochem Photobiol B 2014, 137, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Niu, D.; Liu, X. Effects of Abiotic Stress on Chlorophyll Metabolism. Plant Science 2024, 342, 112030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, P.; Yamamoto, Y. Damage to Photosystem II by Lipid Peroxidation Products. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2017, 1861, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshiharu Shikanai Regulation of Photosynthesis by Cyclic Electron Transport around Photosystem I. In Advances in Botanical Research; Kyoto, 2020; pp. 177–204.

- Anderson, C.M.; Mattoon, E.M.; Zhang, N.; Becker, E.; McHargue, W.; Yang, J.; Patel, D.; Dautermann, O.; McAdam, S.A.M.; Tarin, T.; et al. High Light and Temperature Reduce Photosynthetic Efficiency through Different Mechanisms in the C4 Model Setaria viridis. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Peterson, R.B.; Brutnell, T.P. Regulatory Mechanisms Underlying C 4 Photosynthesis. New Phytologist 2011, 190, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yang, M.; Liu, J.; Huang, H.; Luan, R.; Yue, H.; Zhang, C. Physiological Investigation and Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Mechanisms of Setaria italica’s Yield Formation under Heat Stress. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, Z.A.; Wootan, C.M.; Liang, Z.; Zhou, P.; Engelhorn, J.; Hartwig, T.; Nathan, S.M. Conserved and Variable Heat Stress Responses of the Heat Shock Factor Transcription Factor Family in Maize and <scp> Setaria viridis </Scp>. Plant Direct 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Rodríguez, M.D.; Bhatnagar, N.; Pandey, S. Overexpression of a Plant-Specific Gγ Protein, AGG3, in the Model Monocot Setaria viridis Confers Tolerance to Heat Stress. Plant Cell Physiol 2023, 64, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Pan, J.; Wu, J.; Yuan, M. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analyses of FKBP and CYP Gene Family under Salt and Heat Stress in Setaria italica L. Physiology and Molecular Biology of Plants 2024, 30, 1871–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, P.; Datta, D.; Pattnaik, D.; Dash, D.; Saha, D.; Panda, D.; Bhatta, B.B.; Parida, S.; Mishra, U.N.; Chauhan, J.; et al. Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Adaptation Mechanisms of Photosynthesis and Respiration under Challenging Environments. In Plant Perspectives to Global Climate Changes; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, H.; Niu, G. Plant Responses to Light. In Plant Factory; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, E.; Wakao, S.; Niyogi, K.K. Light Stress and Photoprotection in Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. The Plant Journal 2015, 82, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Ke, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Hou, X. Plants Response to Light Stress. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2022, 49, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sembada, A.A.; Faizal, A.; Sulistyawati, E. Photosynthesis Efficiency as Key Factor in Decision-Making for Forest Design and Redesign: A Systematic Literature Review. Ecological Frontiers 2024, 44, 1128–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger-Liszkay, A.; Kirilovsky, D. Transport of Electrons. In Photosynthesis in Action; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.; Munné-Bosch, S. Tocochromanol Functions in Plants: Antioxidation and Beyond. J Exp Bot 2010, 61, 1549–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, P. The Role of Metals in Production and Scavenging of Reactive Oxygen Species in Photosystem II. Plant Cell Physiol 2014, 55, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksas, B.; Becuwe, N.; Chevalier, A.; Havaux, M. Plant Tolerance to Excess Light Energy and Photooxidative Damage Relies on Plastoquinone Biosynthesis. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, K.S. Nature′s Swiss Army Knife: The Diverse Protective Roles of Anthocyanins in Leaves. Biomed Res Int 2004, 2004, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, J.; Liu, H.; Cao, Z.; Manukovsky, N.S.; Liu, H. Interaction Effects of Light Intensity and Nitrogen Concentration on Growth, Photosynthetic Characteristics and Quality of Lettuce ( Lactuca Sativa L. Var. Youmaicai). Sci Hortic 2017, 214, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonwal, S.; Verma, N.; Sinha, A.K. Regulation of Photosynthetic Light Reaction Proteins via Reversible Phosphorylation. Plant Science 2022, 321, 111312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhong, H.; Wang, Ji.; Sui, X.; Xu, N. Adaptive Changes in Chlorophyll Content and Photosynthetic Features to Low Light in Physocarpus Amurensis Maxim and Physocarpus Opulifolius “Diabolo. ” PeerJ 2016, 4, e2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.; Watson-Lazowski, A.; Oszvald, M.; Griffiths, C.; Paul, M.J.; Furbank, R.T.; Ghannoum, O. Sugar Sensing Responses to Low and High Light in Leaves of the C4 Model Grass Setaria viridis. J Exp Bot 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Liu, Q.; Dai, X.; Wang, X. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals the Correlation between End-of-Day Far Red Light and Chilling Stress in Setaria viridis. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.Y.; Zhang, L.G.; Huang, L.; Qi, X.; Wen, Y.Y.; Dong, S.Q.; Song, X.E.; Wang, H.F.; Guo, P.Y. Photosynthetic and Physiological Responses of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) to Low-Light Stress during Grain-Filling Stage. Photosynthetica 2017, 55, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavi, I.; Thevs, N.; Priori, S. Soil Salinity and Sodicity in Drylands: A Review of Causes, Effects, Monitoring, and Restoration Measures. Front Environ Sci 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Song, C.; Zhu, J.-K.; Shabala, S. Mechanisms of Plant Responses and Adaptation to Soil Salinity. The Innovation 2020, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, N.; Yang, Z.; Liu, M.; Wang, B. Identification and Transcriptomic Profiling of Genes Involved in Increasing Sugar Content during Salt Stress in Sweet Sorghum Leaves. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, J.-L.; Liu, L.-N.; Xie, Q.; Sui, N. Photosynthetic Regulation Under Salt Stress and Salt-Tolerance Mechanism of Sweet Sorghum. Front Plant Sci 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EL-MAAROUF-BOUTEAU, H.; SAJJAD, Y.; BAZIN, J.; LANGLADE, N.; CRISTESCU, S.M.; BALZERGUE, S.; BAUDOUIN, E.; BAILLY, C. Reactive Oxygen Species, Abscisic Acid and Ethylene Interact to Regulate Sunflower Seed Germination. Plant Cell Environ 2015, 38, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Tohge, T.; Ivakov, A.; Mueller-Roeber, B.; Fernie, A.R.; Mutwil, M.; Schippers, J.H.M.; Persson, S. Salt-Related MYB1 Coordinates Abscisic Acid Biosynthesis and Signaling during Salt Stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2015, 169, 1027–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.R.; Roy Choudhury, S.; Estelle, A.B.; Vijayakumar, A.; Zhu, C.; Hovis, L.; Pandey, S. Optimization of Phenotyping Assays for the Model Monocot Setaria viridis. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.M.M.; Santos, M. de L.; Lopes, C.L.; Sousa, C.A.F. de; Souza Junior, M.T. Effect of Salinity Stress in Setaria viridis (L.) P. Beauv. Accession A10.1 during Seed Germination and Plant Development. Ciência e Agrotecnologia 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Sun, M.; He, W.; Guo, S.; Feng, J.; Wang, H.; Yang, Q.; Pan, H.; Lou, Y.; Zhuge, Y. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Molecular Mechanisms under Salt Stress in Leaves of Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.). Plants 2022, 11, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathne, S.D.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.-Q.; Dang, V.H.; Angessa, T.T.; Li, C. Using Chlorate as an Analogue to Nitrate to Identify Candidate Genes for Nitrogen Use Efficiency in Barley. Molecular Breeding 2021, 41, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dias, M.C.; Freitas, H. Drought and Salinity Stress Responses and Microbe-Induced Tolerance in Plants. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeriano, F.R.; de Moura, S.M.; Travassos-Lins, J.; Alves-Ferreira, M.; Vieira, R.C.; Ortiz-Silva, B.; Reinert, F. Evaluation of Setaria viridis Responses to Salt Treatment and Potassium Supply: A Characterization of Three Contrasting Accessions. Brazilian Journal of Botany 2021, 44, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Bezerra, A.C.; da Cunha Valença, D.; da Gama Junqueira, N.E.; Moll Hüther, C.; Borella, J.; Ferreira de Pinho, C.; Alves Ferreira, M.; Oliveira Medici, L.; Ortiz-Silva, B.; Reinert, F. Potassium Supply Promotes the Mitigation of NaCl-Induced Effects on Leaf Photochemistry, Metabolism and Morphology of Setaria viridis. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2021, 160, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Shahzad, B.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Singh Sidhu, G.P.; Bali, A.S.; Handa, N.; Kapoor, D.; Yadav, P.; Khanna, K.; et al. Photosynthetic Response of Plants Under Different Abiotic Stresses: A Review. J Plant Growth Regul 2020, 39, 509–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essemine, J.; Qu, M.; Lyu, M.-J.A.; Song, Q.; Khan, N.; Chen, G.; Wang, P.; Zhu, X.-G. Photosynthetic and Transcriptomic Responses of Two C4 Grass Species with Different NaCl Tolerance. J Plant Physiol 2020, 253, 153244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essemine, J.; Lyu, M.-J.A.; Qu, M.; Perveen, S.; Khan, N.; Song, Q.; Chen, G.; Zhu, X.-G. Contrasting Responses of Plastid Terminal Oxidase Activity Under Salt Stress in Two C4 Species With Different Salt Tolerance. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E.H.; Lawson, T. Chlorophyll Fluorescence Analysis: A Guide to Good Practice and Understanding Some New Applications. J Exp Bot 2013, 64, 3983–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahad, S.; Hussain, S.; Matloob, A.; Khan, F.A.; Khaliq, A.; Saud, S.; Hassan, S.; Shan, D.; Khan, F.; Ullah, N.; et al. Phytohormones and Plant Responses to Salinity Stress: A Review. Plant Growth Regul 2015, 75, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, A.L.; Muneer, S.; Kim, Y.-H.; Al-Rawahi, A.; Al-Harrasi, A. Silicon and Salinity: Crosstalk in Crop-Mediated Stress Tolerance Mechanisms. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zelm, E.; Zhang, Y.; Testerink, C. Salt Tolerance Mechanisms of Plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2020, 71, 403–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Lai, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Dai, Y.-S.; Wang, C.; Du, J.; Xiao, S.; Yang, C. Jasmonate Complements the Function of Arabidopsis Lipoxygenase3 in Salinity Stress Response. Plant Science 2016, 244, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-Y.; Kang, F.-C.; Wang, Y.-Y. Glucosinolate Transporter1 Involves in Salt-Induced Jasmonate Signaling and Alleviates the Repression of Lateral Root Growth by Salt in Arabidopsis. Plant Science 2020, 297, 110487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; Hu, Q.; Yang, C.; Zhu, L.; Luo, H. Constitutive Expression of a MiR319 Gene Alters Plant Development and Enhances Salt and Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Creeping Bentgrass. Plant Physiol 2013, 161, 1375–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, H.; Li, Y.; Tang, W.; Ma, L.; Yang, G.; Sun, J. Genomic Characterization and Expression Analysis of TCP Transcription Factors in Setaria italica and Setaria viridis. Plant Signal Behav 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Jiao, L.; Li, C.; Zhu, D.; Yu, J. A Non-Specific Setaria italica Lipid Transfer Protein Gene Plays a Critical Role under Abiotic Stress. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthamilarasan, M.; Singh, R.K.; Suresh, B.V.; Rana, S.; Dulani, P.; Prasad, M. Genomic Dissection and Expression Analysis of Stress-Responsive Genes in C4 Panicoid Models, Setaria italica and Setaria viridis. J Biotechnol 2020, 318, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; He, S.; Fu, Y.; Yu, R.; Gao, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Chen, M. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Key Genes in Response to Salinity Stress during Seed Germination in Setaria italica. Environ Exp Bot 2021, 191, 104604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Amna, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Javed, M.T.; Ali, Q.; Azeem, M.; Ali, S. Nutrient Deficiency Stress and Relation with Plant Growth and Development. In Engineering Tolerance in Crop Plants Against Abiotic Stress; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2021; pp. 239–262. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Tan, H.; Shan, M.; Duan, M.; Ye, L.; Yang, Y.; He, L.; Shen, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the NPF Genes Provide New Insight into Low Nitrogen Tolerance in Setaria. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, F.; Ahmad, Z.; Wang, R.; Han, J.; Shen, Q.; Chang, F.; Diao, X.; Zhang, F.; Li, X. Foxtail Millet [Setaria italica (L.) Beauv.] Grown under Low Nitrogen Shows a Smaller Root System, Enhanced Biomass Accumulation, and Nitrate Transporter Expression. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Miller, A.J. Plant Nitrogen Assimilation and Use Efficiency. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2012, 63, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeem, F.; Mahmood, R.; Sabir, M.; Khan, W.-D.; Haider, M.S.; Wang, R.; Zhong, Y.; Ishfaq, M.; Li, X. Foxtail Millet [Setaria italica (L.) Beauv.] over-Accumulates Ammonium under Low Nitrogen Supply. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2022, 185, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Dong, E.; Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, E.; Jiao, X.; Diao, X. Foxtail Millet [Setaria italica (L.) P. Beauv.] Grown under Nitrogen Deficiency Exhibits a Lower Folate Contents. Front Nutr 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, M.; Zhong, L.; Liu, J.; Xu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.-B.; Guo, C.-H.; Ma, Y.-Z. Overexpression of the Autophagy-Related Gene SiATG8a from Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) Confers Tolerance to Both Nitrogen Starvation and Drought Stress in Arabidopsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2015, 468, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, M.; Wang, E.; Hu, L.; Hawkesford, M.J.; Zhong, L.; Chen, Z.; Xu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Autophagy-Associated Genes in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) and Characterization of the Function of SiATG8a in Conferring Tolerance to Nitrogen Starvation in Rice. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; He, Z.; Qi, X.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Le, S.; Chen, K.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Z.; et al. Overexpression of MYB-like Transcription Factor SiMYB30 from Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) Confers Tolerance to Low Nitrogen Stress in Transgenic Rice. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2023, 196, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, Z.; Nadeem, F.; Wang, R.; Diao, X.; Han, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, X. A Larger Root System Is Coupled With Contrasting Expression Patterns of Phosphate and Nitrate Transporters in Foxtail Millet [Setaria italica (L.) Beauv.] Under Phosphate Limitation. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roch, G.V.; Maharajan, T.; Krishna, T.P.A.; Ignacimuthu, S.; Ceasar, S.A. Expression of PHT1 Family Transporter Genes Contributes for Low Phosphate Stress Tolerance in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica) Genotypes. Planta 2020, 252, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Chen, M.; Ling, B.; Cao, T.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Tang, W.; Chen, K.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Overexpression of the Autophagy-Related Gene SiATG8a from Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) in Transgenic Wheat Confers Tolerance to Phosphorus Starvation. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2023, 196, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Khan, N.U.; Dai, S.; Qin, N.; Han, Z.; Guo, B.; Li, J. Transcriptome Analysis and Identification of the Low Potassium Stress-Responsive Gene SiSnRK2. 6 in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 2024, 137, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Hu, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, R.; Cheng, D.; Li, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, A.; et al. Genome-Wide Analysis and Identification of the Low Potassium Stress Responsive Gene SiMYB3 in Foxtail Millet (Setariaitalica L.). BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajyoti, P.C.; Lee, K.D.; Sreekanth, T.V.M. Heavy Metals, Occurrence and Toxicity for Plants: A Review. Environ Chem Lett 2010, 8, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Parihar, R.D.; Sharma, A.; Bakshi, P.; Singh Sidhu, G.P.; Bali, A.S.; Karaouzas, I.; Bhardwaj, R.; Thukral, A.K.; Gyasi-Agyei, Y.; et al. Global Evaluation of Heavy Metal Content in Surface Water Bodies: A Meta-Analysis Using Heavy Metal Pollution Indices and Multivariate Statistical Analyses. Chemosphere 2019, 236, 124364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.P.; Mahajan, P.; Kaur, S.; Batish, D.R.; Kohli, R.K. Chromium Toxicity and Tolerance in Plants. Environ Chem Lett 2013, 11, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, M.; Ma, Y. Mitigation of Heavy Metal Stress in the Soil through Optimized Interaction between Plants and Microbes. J Environ Manage 2023, 345, 118732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.A.; Bashir, O.; Ul Haq, S.A.; Amin, T.; Rafiq, A.; Ali, M.; Américo-Pinheiro, J.H.P.; Sher, F. Phytoremediation of Heavy Metals in Soil and Water: An Eco-Friendly, Sustainable and Multidisciplinary Approach. Chemosphere 2022, 303, 134788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, B.; Ahmad, N.; Li, G.; Jalal, A.; Khan, A.R.; Zheng, X.; Naeem, M.; Du, D. Unlocking Plant Resilience: Advanced Epigenetic Strategies against Heavy Metal and Metalloid Stress. Plant Science 2024, 349, 112265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, N.; Imran, M.; Shaheen, M.R.; Ishaque, W.; Kamran, M.A.; Matloob, A.; Rehim, A.; Hussain, S. Phytoremediation Strategies for Soils Contaminated with Heavy Metals: Modifications and Future Perspectives. Chemosphere 2017, 171, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachappanavar, V.; Gupta, S.K.; Jayaprakash, G.K.; Abbas, M. Silicon Mediated Heavy Metal Stress Amelioration in Fruit Crops. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, B.; Tanveer, M.; Hassan, W.; Shah, A.N.; Anjum, S.A.; Cheema, S.A.; Ali, I. Lithium Toxicity in Plants: Reasons, Mechanisms and Remediation Possibilities – A Review. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2016, 107, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, A.; Schmitt, C.; Moulouel, B.; Mirmiran, A.; Puy, H.; Lefèbvre, T.; Gouya, L. Iron, Heme Synthesis and Erythropoietic Porphyrias: A Complex Interplay. Metabolites 2021, 11, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, B.; Yang, F.; Ding, Y.; Liu, H.; et al. Selenite Affected Photosynthesis of Oryza Sativa L. Exposed to Antimonite: Electron Transfer, Carbon Fixation, Pigment Synthesis via a Combined Analysis of Physiology and Transcriptome. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2023, 201, 107904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, P.; Kumari, N.; Sharma, V. Structural and Functional Alterations in Photosynthetic Apparatus of Plants under Cadmium Stress. Bot Stud 2013, 54, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakoula, A.; Therios, I.; Chatzissavvidis, C. Effect of Lead and Copper on Photosynthetic Apparatus in Citrus (Citrus Aurantium L.) Plants. The Role of Antioxidants in Oxidative Damage as a Response to Heavy Metal Stress. Plants 2021, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Yadav, V.; Arif, N.; Singh, V.P.; Dubey, N.K.; Ramawat, N.; Prasad, R.; Sahi, S.; Tripathi, D.K.; Chauhan, D.K. Heavy Metal Stress and Plant Life: Uptake Mechanisms, Toxicity, and Alleviation. In Plant Life Under Changing Environment; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Ni, J.; Mo, A.; Fan, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, H.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Peng, C.; Yang, F. Cadmium Affects the Growth, Antioxidant Capacity, Chlorophyll Content, and Homeostasis of Essential Elements in Soybean Plants. South African Journal of Botany 2023, 162, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Manzoor, M.A.; Mao, D.; Ren, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y. Photosynthetic Machinery and Antioxidant Enzymes System Regulation Confers Cadmium Stress Tolerance to Tomato Seedlings Pretreated with Melatonin. Sci Hortic 2024, 323, 112550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wu, Y.; Che, J.; Lyu, L.; Wu, W.; Cao, F.; Li, W. Effects of Cadmium Stress on the Growth, Physiology, Mineral Uptake, Cadmium Accumulation and Fruit Quality of “Sharpblue” Blueberry. Sci Hortic 2024, 337, 113593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.; Kuang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mickan, B.S.; Xu, B.; Zhang, S.; Deng, X.; Yu, M.; et al. Variability in Cadmium Stress Tolerance among Four Maize Genotypes: Impacts on Plant Physiology, Root Morphology, and Chloroplast Microstructure. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2023, 205, 108135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Chenchang, W.; Tao, C. Advances in Understanding Cadmium Stress and Breeding of Cadmium-Tolerant Crops. Rice Sci 2024, 31, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.P.; de Souza, W.R.; Martins, P.K.; Vinecky, F.; Duarte, K.E.; Basso, M.F.; da Cunha, B.A.D.B.; Campanha, R.B.; de Oliveira, P.A.; Centeno, D.C.; et al. Overexpression of BdMATE Gene Improves Aluminum Tolerance in Setaria viridis. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, D.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Setaria viridis on Heavy Metal Enrichment Tolerance and Bacterial Community Establishment in High-Sulfur Coal Gangue. Chemosphere 2024, 351, 141265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadid, N.; Puspaningtyas, I.; Jannah, A.L.; Safitri, C.E.; Hutahuruk, V.H.D. Growth Responses of Indonesian Foxtail Millet ( Setaria italica (L.) Beauv.) to Cadmium Stress. Air, Soil and Water Research 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Liang, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, K.; Chen, L.; Aduragbemi, A.; Han, Y.; Sun, Z.; Li, H.; et al. Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein (Nramp) Family in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica): Characterization, Expression Analysis and Relationship with Metal Content under Cd Stress. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Geng, N.; Li, X.; Yu, J.; Wang, H.; Pan, H.; Yang, Q.; Zhuge, Y.; Lou, Y. Biochar Alleviates Phytotoxicity by Minimizing Bioavailability and Oxidative Stress in Foxtail Millet (Setaria italica L.) Cultivated in Cd- and Zn-Contaminated Soil. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulasza, M.; Sielska, A.; Szenejko, M.; Soroka, M.; Skuza, L. Effects of Copper, and Aluminium in Ionic, and Nanoparticulate Form on Growth Rate and Gene Expression of Setaria italica Seedlings. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 15897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).