Submitted:

14 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

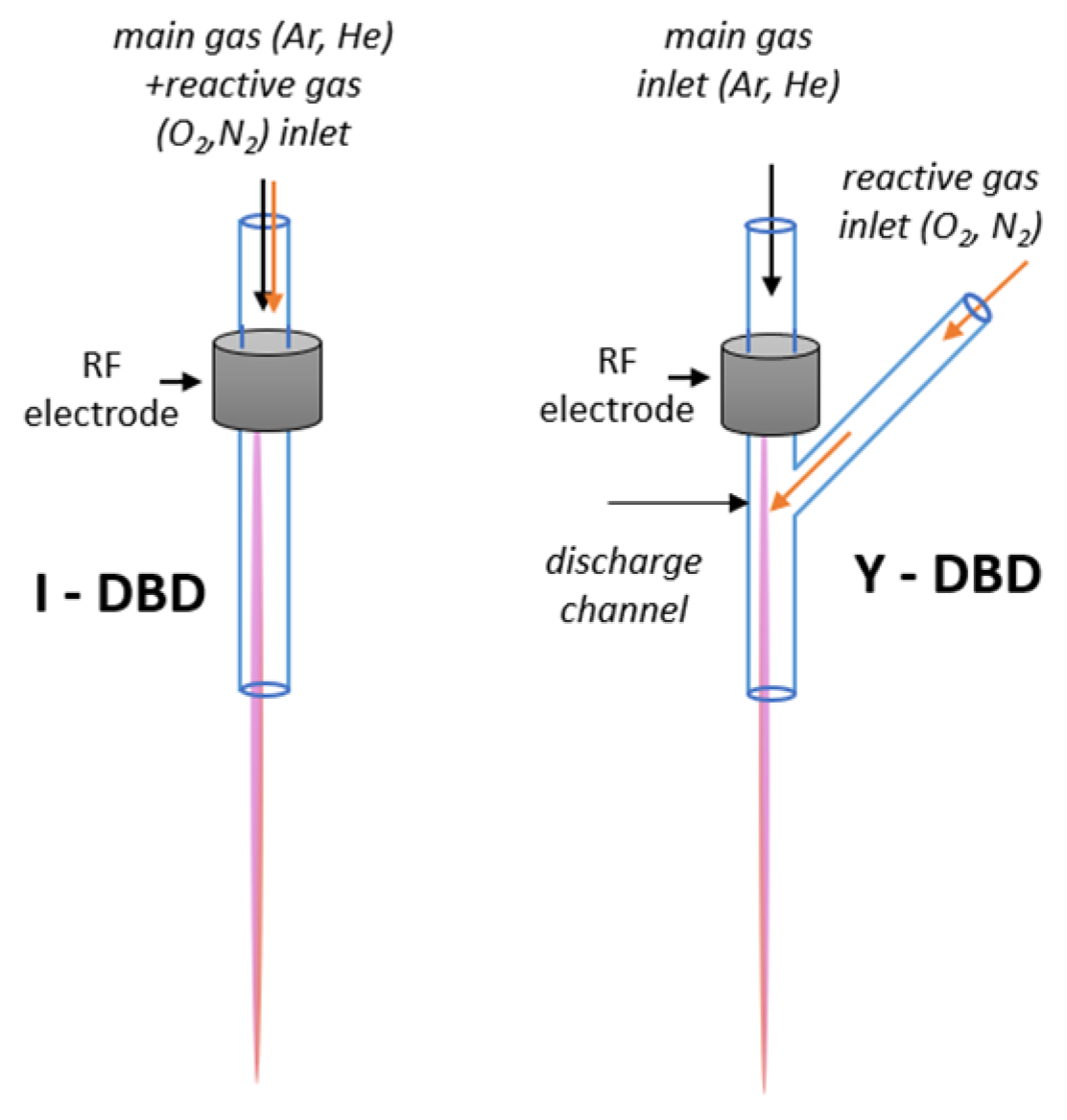

Control of reactive species generation lies at the core of atmospheric-pressure plasma processing. In this work, we investigate the capability of a cold RF argon plasma jet source to produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) following the injection of a molecular gas (N₂ or O₂), either premixed with the main gas (Ar) or introduced separately into an already generated Ar discharge. We show that when reactive gases are injected directly into the Ar discharge, the range of operating parameters—particularly the ratio of reactive gas to main gas—is considerably widened compared to the conventional injection through the main argon flow. The plasma characteristics at the source exit were analyzed using Optical Emission Spectroscopy (OES), including the determination of electron density, rotational temperature, and the emission intensities of plasma species such as Ar I, NO(A), OH(A), and N₂(C), for both injection types. Overall, the results show that plasmas generated using in-discharge injection are more stable and capable of sustaining enhanced production of reactive radicals such as NO(A) and OH(A), whereas injection through the main gas can be tuned to selectively enhance NO generation. These findings highlight the potential of plasma sources employing premixed or in-discharge reactive gas injection for surface treatment and for the processing of gas and liquid phases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Details and Methods

2.1. Plasma Generation and Control

2.2. Plasma Generation and Control

2.3. Gas Estimation Using OH(A-X) Simulations

3. Results

3.1. Determination of the I- and Y-DBD Plasma Jets Operating Domains

3.2. Behavior of the Emitting Species at the Tube Exit

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z. Correlation of Reflected Plasma Angle and Weld Pool Thermal State in Plasma Arc Welding Process. J Manuf Process 2022, 75, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, M.J.; Malley, D.R. Plasma Arc Melting of Titanium Alloys. Mater Des 1993, 14, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-I.; Kim, M.-H. Evaluation of Cutting Characterization in Plasma Cutting of Thick Steel Ship Plates. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing 2013, 14, 1571–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tendero, C.; Tixier, C.; Tristant, P.; Desmaison, J.; Leprince, P. Atmospheric Pressure Plasmas: A Review. Spectrochim Acta Part B At Spectrosc 2006, 61, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovich, I.; Agarwal, S.; Ahedo, E.; Alves, L.L.; Baalrud, S.; Babaeva, N.; Bogaerts, A.; Bourdon, A.; Bruggeman, P.J.; Canal, C. The 2022 Plasma Roadmap: Low Temperature Plasma Science and Technology. J Phys D Appl Phys 2022, 2022, 373001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroussi, M.; Tendero, C.; Lu, X.; Alla, S.; Hynes, W.L. Inactivation of Bacteria by the Plasma Pencil. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2006, 3, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, K.; Ichiki, R.; Kanbara, Y.; Kojima, K.; Tachibana, K.; Furuki, T.; Kanazawa, S. Bright Nitriding Using Atmospheric-Pressure Pulsed-Arc Plasma Jet Based on NH Emission Characteristics. Jpn J Appl Phys 2020, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; de Wege, R. van; Sobota, A. Nitric Oxide (NO) Production in a KHz Pulsed Ar Plasma Jet Operated in Ambient Air. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 2025, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Hayhurst, A.N. The Chemical Reactions of Nitric Oxide with Solid Carbon and Catalytically with Gaseous Carbon Monoxide. Fuel 2015, 142, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanmore, B.R.; Tschamber, V.; Brilhac, J.F. Oxidation of Carbon by NOx, with Particular Reference to NO2 and N2O. Fuel 2008, 87, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, S.O. Reactive Oxygen Species Controllable Nonthermal Atmospheric Pressure Plasmas Using Coaxial Geometry for Biomedical Applications. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2014, 42, 2490–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedrick, J.; Schröter, S.; Niemi, K.; Wijaikhum, A.; Wagenaars, E.; De Oliveira, N.; Nahon, L.; Booth, J.P.; O’Connell, D.; Gans, T. Controlled Production of Atomic Oxygen and Nitrogen in a Pulsed Radio-Frequency Atmospheric-Pressure Plasma. J Phys D Appl Phys 2017, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Nagatomo, T.A.F.M.K.E. and K.N. Takuya Nagatomo_Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 55, 01AB06 (2016). Jpn. J. Appl. Phys 2016, 55. [CrossRef]

- Klyucharev, A.N.; Pechatnikov, P.A. Plasma Ion Source Based on the Barrier Discharge for Earth Atmosphere Pollution Monitoring Systems. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2014, 8, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirafuji, T.; Oh, J.-S. Reaction Kinetics of Active Species from an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet Irradiated on the Flowing Water Surface-Effect of Gas-Drag by the Sliding Water Surface.

- Belmonte, T.; Noël, C.; Gries, T.; Martin, J.; Henrion, G. Theoretical Background of Optical Emission Spectroscopy for Analysis of Atmospheric Pressure Plasmas. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 2015, 24, 064003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleslić, S.; Katalenić, F. Monitoring and Diagnostics of Non-Thermal Plasmas in the Food Sector Using Optical Emission Spectroscopy. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 8325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaplotnik, R.; Primc, G.; Vesel, A. Optical Emission Spectroscopy as a Diagnostic Tool for Characterization of Atmospheric Plasma Jets. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubka, Z.; Novák, J.; Majerová, I.; Green, J.T.; Velpula, P.K.; Boge, R.; Antipenkov, R.; Šobr, V.; Kramer, D.; Majer, K.; et al. Mitigation of Laser-Induced Contamination in Vacuum in High-Repetition-Rate High-Peak-Power Laser Systems. Appl Opt 2021, 60, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolenis, T.; Vazquez, S.; Ramalis, L.; Havlík, M.; Chauvin, A.; Těreščenko, A.; Espinoza, S.; Fučíkova, A.; Andreasson, J.; Havlickova, I.; et al. Complex Analysis of Laser Induced Contamination in High Reflectivity Mirrors. High Power Laser Science and Engineering 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, C.; Alegre, D.; Ionita, E.R.; Mitu, B.; Grisolia, C.; Tabares, F.L.; Dinescu, G. Cleaning of Carbon Materials from Flat Surfaces and Castellation Gaps by an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet. Fusion Engineering and Design 2016, 103, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinescu, G.; Ionita, E.R.; Luciu, I.; Grisolia, C. Flexible Small Size Radiofrequency Plasma Torch for Tokamak Wall Cleaning. Fusion Engineering and Design 2007, 82, 2311–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, S.A.; Zarif, M.E.; Bita, B.I.; Teodorescu, M.; Carpen, L.G.; Vizireanu, S.; Petrea, N.; Dinescu, G. Development and Optimization of Single Filament Plasma Jets for Wastewater Decontamination. Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing 2020, 40, 1485–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, S.A.; Petrea, N.; Grigoriu, N.; Vizireanu, S.; Zarif, M.E.; Carpen, L.G.; Ginghina, R.E.; Dinescu, G. Organophosphorus Toxic Compounds Degradation in Aqueous Solutions Using Single Filament Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma Jet Source. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionita, M.D.; Vizireanu, S.; Stoica, S.D.; Ionita, M.; Pandele, A.M.; Cucu, A.; Stamatin, I.; Nistor, L.C.; Dinescu, G. Functionalization of Carbon Nanowalls by Plasma Jet in Liquid Treatment. European Physical Journal D 2016, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizireanu, S.; Panaitescu, D.M.; Nicolae, C.A.; Frone, A.N.; Chiulan, I.; Ionita, M.D.; Satulu, V.; Carpen, L.G.; Petrescu, S.; Birjega, R.; et al. Cellulose Defibrillation and Functionalization by Plasma in Liquid Treatment. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 15473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolouki, N.; Hsieh, J.H.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.Z. Emission Spectroscopic Characterization of a Helium Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet with Various Mixtures of Argon Gas in the Presence and the Absence of De-Ionized Water as a Target. Plasma 2019, 2, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.C.; Li, Q.; Zhu, X.M.; Pu, Y.K. Characteristics of Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jets Emerging into Ambient Air and Helium. J Phys D Appl Phys 2009, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodorescu, M.; Bazavan, M.; Ionita, E.R.; Dinescu, G. Characteristics of a Long and Stable Filamentary Argon Plasma Jet Generated in Ambient Atmosphere. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 2015, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton Yu Nikiforov, E.-R.I.G.D. and C.L. Nikifirov_Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 58 (2016) 014013 (12pp). Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 2016, 58.

- Index. In Principles of Plasma Discharges and Materials Processing; Wiley, 2005; pp. 749–757.

- Lin, P.; Zhang, J.; Nguyen, T.; Donnelly, V.M.; Economou, D.J. Numerical Simulation of an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet with Coaxial Shielding Gas. J Phys D Appl Phys 2021, 54, 075205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Tresp, H.; Wende, K.; Hammer, M.U.; Winter, J.; Masur, K.; Schmidt-Bleker, A.; Weltmann, K.D. From RONS to ROS: Tailoring Plasma Jet Treatment of Skin Cells. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2012, 40, 2986–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, S.; Winter, J.; Schmidt-Bleker, A.; Tresp, H.; Hammer, M.U.; Weltmann, K.D. Controlling the Ambient Air Affected Reactive Species Composition in the Effluent of an Argon Plasma Jet. IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science 2012, 40, 2788–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Zhang, J.; Nguyen, T.; Donnelly, V.M.; Economou, D.J. Numerical Simulation of an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet with Coaxial Shielding Gas. J Phys D Appl Phys 2021, 54, 075205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüttler, S.; Kaufmann, J.; Golda, J. Nitrogen Fixation and H2O2 Production by an Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet Operated in He–H20–N2–O2 Gas Mixtures. Plasma Processes and Polymers 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.A.H.; Basher, A.H.; Almarashi, J.Q.M.; Ouf, S.A. Susceptibility of Staphylococcus Epidermidis to Argon Cold Plasma Jet by Oxygen Admixture. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, A.H.; Galaly, A.R. The Effect of Oxygen Admixture with Argon Discharges on the Impact Parameters of Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jet Characteristics. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Naidis, G.V.; Laroussi, M.; Reuter, S.; Graves, D.B.; Ostrikov, K. Reactive Species in Non-Equilibrium Atmospheric-Pressure Plasmas: Generation, Transport, and Biological Effects. Phys Rep 2016, 630, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griem, H.R.; Kolb, A.C.; Shen, K.Y. Stark Broadening of Hydrogen Lines in a Plasma. Physical Review 1959, 116, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigosos, M.A.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Cardenoso, V. Spectrochimica Acta Electronica Computer Simulated Balmer-Alpha,-Beta and-Gamma Stark Line Profiles for Non-Equilibrium Plasmas Diagnostics. Spectrochimica Acta Part B 2003, 58, 1489–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.-K.; Montaser, A. Determination of Electron Number Density via Stark Broadening with an Improved Algorithm; 1989; Vol. 448;

- Bazavan, M.; Teodorescu, M.; Dinescu, G. Confirmation of OH as Good Thermometric Species for Gas Temperature Determination in an Atmospheric Pressure Argon Plasma Jet. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 2017, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Fattah, E.; Bazavan, M.; Shindo, H. Temperature Measurements in Microwave Argon Plasma Source by Using Overlapped Molecular Emission Spectra. Phys Plasmas 2015, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Li, S.Z. Investigation of a Nitrogen Post-Discharge of an Atmospheric-Pressure Microwave Plasma Torch by Optical Emission Spectroscopy. Phys Plasmas 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gangwar, R.K.; Srivastava, R. Diagnostics of Ar/N2 Mixture Plasma with Detailed Electron-Impact Argon Fine-Structure Excitation Cross Sections. Spectrochim Acta Part B At Spectrosc 2018, 149, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boris, D.R.; Petrov, G.M.; Lock, E.H.; Petrova, T.B.; Fernsler, R.F.; Walton, S.G. Controlling the Electron Energy Distribution Function of Electron Beam Generated Plasmas with Molecular Gas Concentration: I. Experimental Results. Plasma Sources Sci Technol 2013, 22, 065004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouwenhorst, K.H.R.; Jardali, F.; Bogaerts, A.; Lefferts, L. From the Birkeland–Eyde Process towards Energy-Efficient Plasma-Based NO X Synthesis: A Techno-Economic Analysis. Energy Environ Sci 2021, 14, 2520–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaens, W. Van; Iseni, S.; Schmidt-Bleker, A.; Weltmann, K.D.; Reuter, S.; Bogaerts, A. Numerical Analysis of the Effect of Nitrogen and Oxygen Admixtures on the Chemistry of an Argon Plasma Jet Operating at Atmospheric Pressure. New J Phys 2015, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).