Submitted:

14 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

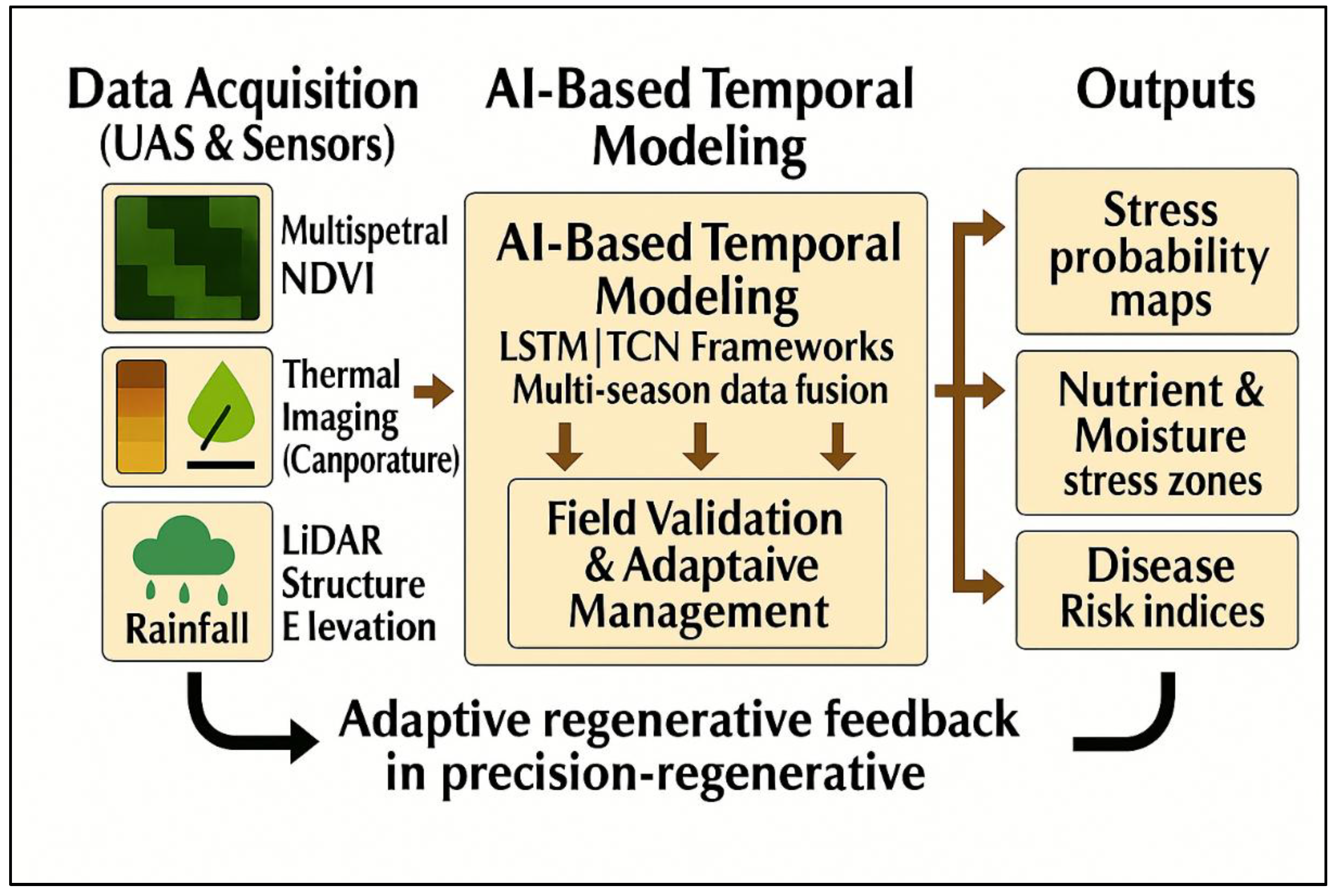

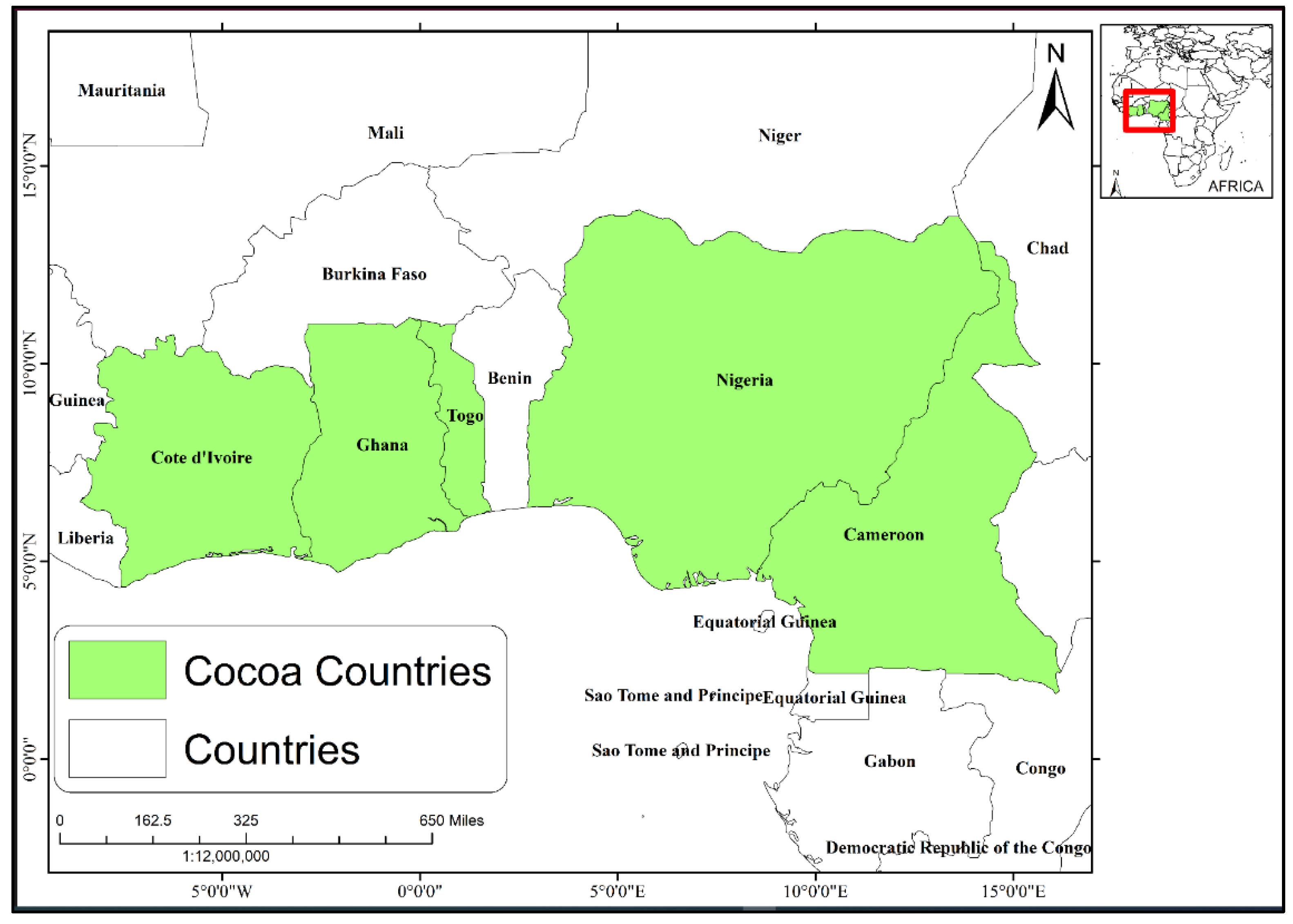

Cocoa production in West Africa—dominated by Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Togo—faces interconnected agronomic, environmental, and socio-economic challenges that limit productivity and threaten smallholder livelihoods. Integrating Regenerative Agriculture (RA), Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), and Artificial Intelligence (AI) present a transformative framework for achieving sustainable and climate-resilient cocoa farming. This review synthesizes evidence from 2000 to 2024 and establishes a tri-axial model that unites ecological regeneration, spatial diagnostics, and predictive intelligence. Regenerative practices such as composting, mulching, cover cropping, and agroforestry rebuild soil organic matter, enhance biodiversity, and strengthen ecosystem services. UAS-based multispectral, thermal, and LiDAR sensing provide high-resolution insights into canopy vigor, nutrient stress, and microclimatic variability across heterogeneous cocoa landscapes. When coupled with AI-driven analytics for crop classification, disease detection, yield forecasting, and decision support, these tools collectively enhance soil organic carbon by 15–25%, stabilize yields by 12–28%, and reduce fertilizer and water inputs by 10–20%. The integrated RA–UAS–AI framework also facilitates carbon-credit quantification, ecosystem-service valuation, and inclusive participation through cooperative drone networks. Overall, this convergence defines a precision-regenerative model tailored to West African cocoa systems, aligning productivity gains with ecological restoration, resilience, and regional sustainability.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.2. Integrating Regenerative, Aerial, and Analytical Approaches

1.3. Objectives of the Review

- Assess current knowledge on the application of RA, UAS, and AI in cocoa production systems across West Africa.

- Evaluate how their integration enhances soil health, productivity, and ecological sustainability; and

- Identify enabling policies, institutional frameworks, and research priorities to scale regenerative, technology-enabled cocoa farming.

1.4. Reader Roadmap

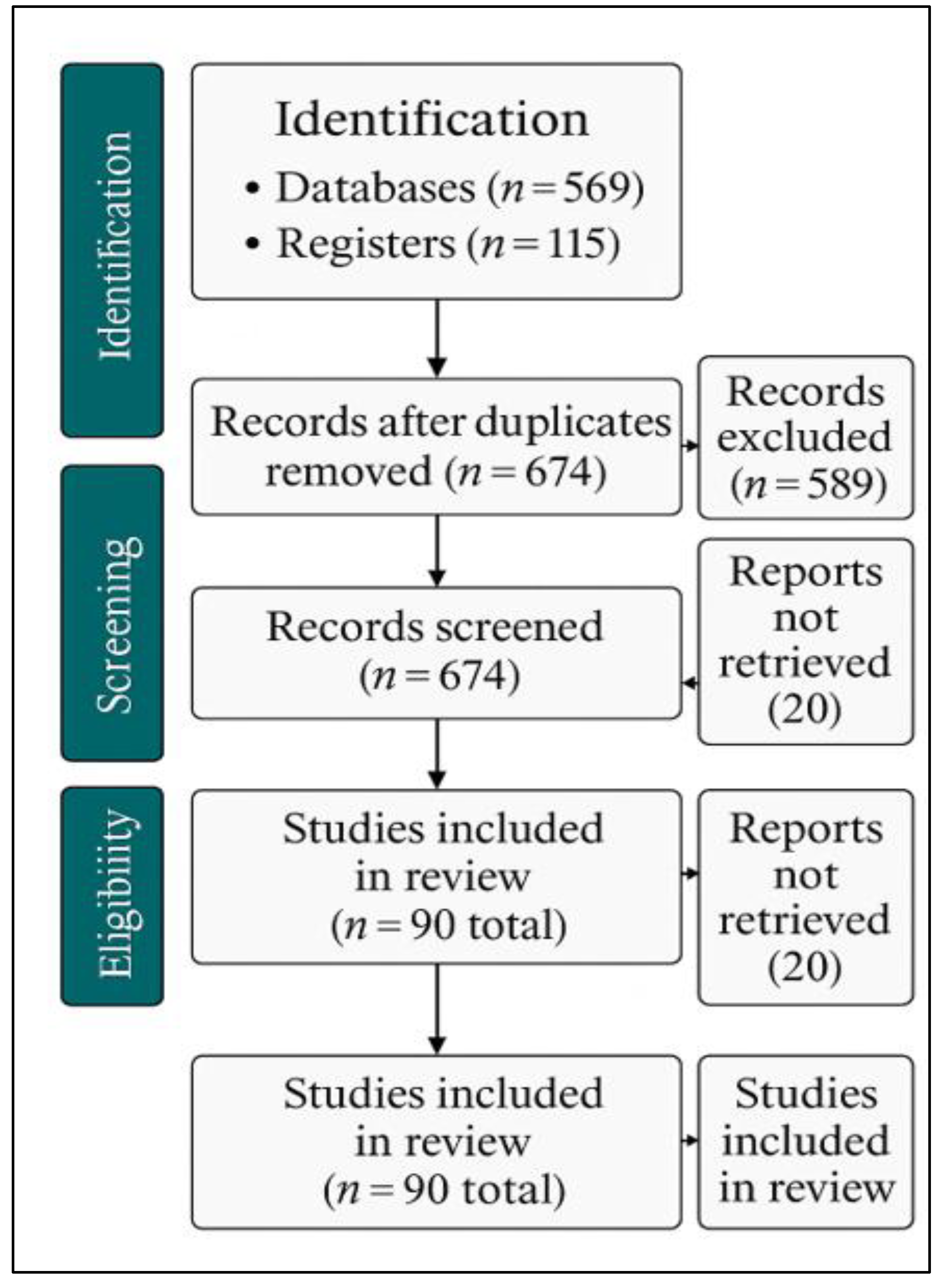

- Section 2 details the methodological framework and literature-selection process following PRISMA 2020 guidelines.

- Section 3 examines regional cocoa-production systems, yield trends, and agronomic constraints.

- Section 4 synthesizes regenerative-agriculture principles and field-validated practices.

- Section 5 presents UAS-based spatial monitoring—NDVI, thermal, and LiDAR analyses.

- Section 6 discusses deep-learning and analytical applications in cocoa farming.+

2. Methodological Framework

2.1. Review Protocol and Rationale

2.2. Search Strategy and Data Sources

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Studies addressed Theobroma cacao systems within West Africa.

- Focused on at least one of the three analytical domains (RA, UAS, or AI).

- Reported empirical, experimental, or modeling data on productivity, soil health, or sustainability.

- Were written in English and accessible in full text.

2.4. Analytical Framework and Synthesis Approach

2.5. Quality Assessment and Validation

2.6. Output Summary

3. Production Capacities and Agronomic Constraints in West Africa

3.1. Regional Context and Comparative Overview

3.2. Production Capacities and Agronomic Constraints of Major Producers

3.2.1. Côte d’Ivoire

3.2.2. Ghana

3.2.3. Nigeria

3.2.4. Cameroon

3.2.5. Togo

3.3. Long-Term Yield Dynamics and Structural Patterns (2000–2023)

3.4. Synthesis and Implications for Precision-Regenerative Management

4. Regenerative Agriculture in Cocoa Production Systems

4.1. Core Principles and Systemic Role

4.2. Soil Health Restoration and Carbon Dynamics

4.3. Agroforestry as the Structural Backbone

4.4. Soil-Disturbance Minimization and Structural Integrity

4.5. Mulching, Cover Cropping, and Nutrient Efficiency

4.6. Biodiversity and Socio-Ecological Integration

4.7. Quantified Outcomes and Conceptual Integration

4.8. Bridging to Technological Harnessing

5. Unmanned Aerial Systems for Spatial Diagnostics and Regenerative Management

5.1. Spectral Indices and Canopy Vigor Diagnostics

5.2. Multispectral–Thermal Synergies

5.3. LiDAR-Based Structural and Terrain Diagnostics

5.4. Integrated Insights and Adaptive Surveillance

6. Artificial Intelligence for Predictive Modeling and Decision Support (Axis III)

6.1. Classification and Detection

6.2. Yield Estimation and Prediction

6.3. Stress Detection and Risk Mapping

6.4. Decision-Support and Regenerative Integration

6.5. Research and Development Priorities

6.6. Policy and Institutional Implications

7. Case Studies and Applications Across West Africa

7.1. Côte d’Ivoire

7.2. Ghana

7.3. Cameroon

7.4. Togo

7.5. Cross-Country Synthesis

7.6. Key Insights

- Synergy Across Scales: Integrating ecological practices (RA) with high-resolution spatial diagnostics (UAS) and predictive modeling (AI) enables scalable precision management, even across highly heterogeneous landscapes.

- Socio-Technical Empowerment: Cooperative drone networks and youth-led data hubs reduce technological barriers, strengthen local innovation ecosystems, and ensure inclusive participation.

- Quantified Sustainability: Tangible improvements in SOC, canopy vigor, and yield demonstrate measurable ecological and economic benefits, supporting climate-smart certification and carbon-credit initiatives.

8. Cross-Axis Integration and Strategic Implications

8.1. Introductory Context

8.2. Synergistic Outcomes Across the Three Axes

8.3. Ecosystem and Climate-Resilience Impacts

8.4. Digital Inclusion and Knowledge Co-Production

8.5. Challenges and Research Frontiers

- Cost and Infrastructure: High deployment costs for UAS operations, limited cloud infrastructure, and inconsistent broadband access constrain data transmission and real-time analytics.

- Model Generalization: Variability in canopy architecture, soil heterogeneity, and local microclimates limit the transferability of AI models across agroecological zones.

- Data Fragmentation: Absence of standardized geospatial data protocols and regional data-sharing platforms impedes collaborative research and reproducibility.

9. Conclusions and Strategic Recommendations

9.1. Regenerative Foundations

- 15–25 % higher soil-organic-carbon content,

- 12–28 % yield gains, and

- up to 20 % reductions in fertilizer and water inputs,

9.2. Technological Convergence for Precision Management

9.3. Institutional Integration and Capacity Building

9.4. Financial Incentives and Carbon Markets

9.5. Strategic Outlook and Policy Alignment

- Establishing regional data-governance frameworks to promote transparency and equitable access.

- Expanding infrastructure for drone-AI integration, including rural connectivity and open cloud services; and

- Institutionalizing inclusive innovation models that center smallholders in the co-design of regenerative technologies.

9.6. Concluding Reflection

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Declaration of Competing Interest

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Cocoa Organization. Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics, 2023, 49(4), Cocoa Year 2022/2023. International Cocoa Organization, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Available online: https://www.icco.org/wp-content/uploads/Production_QBCS-XLIX-No.-4.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Digital Agriculture Report: Rural Transformation through ICTs; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Transforming Cocoa Systems for Sustainable Livelihoods in West Africa; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wessel, M.; Quist-Wessel, P.M.F. Cocoa production in West Africa: A review and analysis of recent developments. NJAS—Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 2015, 74–75, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ruf, F.; Schroth, G. Chocolate forests and monocultures: A historical review of cocoa growing and its environmental impacts. Agroforestry Systems 2021, 95, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G.A.R.; Lass, R.A. Cocoa, 4th ed.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anim-Kwapong, G.J.; Frimpong, E.B. Vulnerability and adaptation assessment under climate change in cocoa production. Ghana Cocoa Research Institute Technical Report 2010, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Schroth, G.; Läderach, P.; Martinez-Valle, A.I.; Bunn, C.; Jassogne, L. Vulnerability to climate change of cocoa in West Africa: Patterns, opportunities and limits to adaptation. Science of the Total Environment 2016, 556, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, R.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Osei-Owusu, Y.; Pabi, O. Cocoa agroforestry for increased climate resilience in Ghana. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisseleua, D.H.B.; Missoup, A.D.; Vidal, S. Biodiversity conservation, ecosystem functioning, and economic incentives under cocoa agroforestry intensification. Conservation Biology 2009, 23(5), 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaac, M.E.; Dawoe, E.; Sieciechowicz, K. Assessing local knowledge use in agroforestry management with cognitive maps. Environmental Management 2009, 43(6), 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawoe, E.; Asante, W.A.; Acheampong, E. Soil fertility under cocoa agroforestry systems and monocultures in Ghana. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2010, 138, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaser, W.J.; Oppong, J.; Hart, S.P.; et al. Climate-smart cocoa production requires local adaptation and biodiversity protection. Global Environmental Change 2018, 48, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Läderach, P.; Eitzinger, A.; Martinez, A.; Castro, N.; Collet, L. Predicting the future climatic suitability for cocoa farming of the world’s leading producer countries, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Climatic Change 2013, 119, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroth, G.; Ruf, F.; et al. Cocoa and climate change: A review of adaptation options. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2015, 20(2), 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Regenerative agriculture for food and climate. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2020, 75(5), 123A–124A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.J. The imperative for regenerative agriculture. Science Progress 2017, 100(1), 80–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reganold, J.P.; Wachter, J.M. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nature Plants 2016, 2, 15221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulla, D.J. Twenty-five years of remote sensing in precision agriculture: Key advances and remaining knowledge gaps. Biosystems Engineering 2013, 114(4), 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Climate-Smart Agriculture Sourcebook: Module 3—Crops and Cropping Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Cocoa Board (COCOBOD). Annual Report 2022–2023; Accra, Ghana, 2023.

- Godwin, R.J.; Richards, T.E.; Wood, G.A.; Welsh, J.P.; Knight, S.M. Precision farming of cereal crops: A review of six years of experiments to develop management guidelines. Biosystems Engineering 2003, 84(4), 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, F.J.; Nowak, P. Aspects of precision agriculture. Advances in Agronomy 1999, 67, 1–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongiovanni, R.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. Precision agriculture and sustainability. Precision Agriculture 2004, 5(4), 359–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatar, T.M.; McBratney, A.B. Site-specific management of soil variability: A review of variability sources and implications for precision agriculture. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2001, 38(1), 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBratney, A.B.; Mendonça Santos, M.L.; Minasny, B. On digital soil mapping. Geoderma 2003, 117(1–2), 3–52. [CrossRef]

- Saidou, A. , Kuyper, T.W., Kossou, D.K., Tossou, R., & Richards, P. (2012). Soil fertility management and cocoa production in West Africa: A review. Agricultural Systems, 110, 1–9.

- Isong, I. A.; Olim, D. M.; Nwachukwu, O. I.; Onwuka, M. I.; Afu, S. M.; Otie, V. O.; Oko, P. E.; Heung, B.; John, K. Delineating Soil Management Zones for Site-Specific Nutrient Management in Cocoa Cultivation Areas with a Long History of Pesticide Usage . Land 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gong, P. A hybrid classification scheme for land cover mapping with high-resolution remotely sensed images over urban areas. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2016, 119, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R. Precision agriculture: The way forward to enhance agricultural productivity and sustainability. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Agricultural Engineering, Wuhan, China; 2010; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, A.; Akram, M.; Saleem, M. Impact of remote sensing in precision agriculture in Pakistan. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology 2019, 20, 100–112. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant remote sensing vegetation indices: A review of developments and applications. Journal of Sensors 2017, 2017, 1353691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzid, R.; Alaya, M.A.; et al. Machine learning and remote sensing data fusion for crop yield estimation. Remote Sensing 2022, 14(12), 2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Blu, R.; Molina-Roco, M. Evaluation of site-specific nitrogen management using remote sensing and GIS in irrigated maize. Precision Agriculture 2016, 17(4), 418–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Shankar, R.; Jha, S.K. Review on UAV-based crop monitoring for precision agriculture: Applications, challenges and future trends. Drones 2023, 7(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.R.; Suryanarayana, T.M.V.; et al. Drone-based thermal imaging for irrigation scheduling in tropical crops. Agricultural Water Management 2022, 262, 107437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, G.; et al. Multi-temporal UAV data for crop growth monitoring using deep learning. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2021, 311, 108686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoulaye, T.; et al. Cocoa value chain transformation in Nigeria: Constraints and prospects. African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2018, 13(1), 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Clough, Y.; Barkmann, J.; Juhrbandt, J.; et al. Combining high biodiversity with high yields in tropical agroforests. PNAS 2011, 108(20), 8311–8316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarriba, E.; et al. Carbon stocks and cocoa yield in agroforestry systems: Trade-offs and opportunities. Agroforestry Systems 2021, 95(3), 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahenkorah, Y.; Halm, B.J.; Appiah, M.R.; et al. Twenty years’ results from a long-term fertilizer trial on cocoa. Experimental Agriculture 1987, 23(1), 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzahini-Obiatey, H.; Ameyaw, G.A.; et al. Cocoa Swollen Shoot Virus Disease: History, etiology, and management. Tree and Forestry Science and Biotechnology 2010, 4(2), 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Anim-Kwapong, G.J.; et al. Impact of age on cocoa productivity and nutrient dynamics. Ghana Journal of Agricultural Science 2011, 44, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler, P.L.; et al. The economics of cocoa farming under climate change. World Development Perspectives 2022, 25, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 2004, 304(5677), 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Six, J.; Conant, R.T.; Paul, E.A.; Paustian, K. Stabilization mechanisms of soil organic matter: Implications for C-saturation. Plant and Soil 2002, 241(2), 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Soussana, J.F.; Angers, D.; et al. How to measure, report and verify soil carbon change to realize the potential of soil carbon sequestration for atmospheric greenhouse gas removal. Global Change Biology 2020, 26(1), 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palm, C.A.; Smukler, S.M.; Sullivan, C.C.; Mutuo, P.K.; Nyadzi, G.I.; Walsh, M.G. Identifying potential synergies and trade-offs for meeting food security and climate change objectives in sub-Saharan Africa. PNAS 2010, 107(46), 19661–19666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vågen, T.G.; Lal, R.; Singh, B.R. Soil carbon sequestration in sub-Saharan Africa: A review. Land Degradation & Development 2005, 16(1), 53–71. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Stewart, B.A. Soil Degradation and Restoration in Africa; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil health and carbon management. Food and Energy Security 2016, 5(4), 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivenge, P.; Vanlauwe, B.; Six, J. Does the combined application of organic and mineral nutrient sources influence maize productivity? A meta-analysis. Plant and Soil 2011, 342(1–2), 1–30. [CrossRef]

- Agegnehu, G.; Nelson, P.N.; Bird, M.I. Crop yield, plant nutrient uptake and soil physicochemical properties under organic soil amendments and nitrogen fertilization on Nitisols. Soil and Tillage Research 2016, 160, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leakey, R.R.B. Definition of agroforestry revisited. Agroforestry Today 1996, 8(1), 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jose, S. Agroforestry for ecosystem services and environmental benefits: An overview. Agroforestry Systems 2009, 76(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, S.A.; Willis, K.J.; Birks, H.J.B.; Whittaker, R.J. Agroforestry: A refuge for tropical biodiversity? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2008, 23(5), 261–267. [CrossRef]

- Noponen, M.R.A.; Healey, J.R.; Soto, G.; Haggar, J.P. Sink or source—The potential of coffee agroforestry systems to sequester atmospheric CO₂ into soil organic carbon. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2013, 175, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, A.; Friedrich, T.; Derpsch, R. Global spread of conservation agriculture. International Journal of Environmental Studies 2019, 76(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derpsch, R.; Franzluebbers, A.J.; Duiker, S.W.; Reicosky, D.C.; Koeller, K.; Friedrich, T.; Sturny, W.G.; Sá, J.C.M.; Weiss, K. Why do we need to standardize no-tillage research? Soil and Tillage Research 2014, 137, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, D.J.; Schepers, J.S. Key advances in precision agriculture. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2019, 83(5), 1420–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Enhancing ecosystem services with no-till. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 2015, 30(2), 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clay, J. World Agriculture and the Environment: A Commodity-by-Commodity Guide to Impacts and Practices; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, P.A. Soil fertility and hunger in Africa. Science 2002, 295(5562), 2019–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tittonell, P.; Giller, K.E. When yield gaps are poverty traps: The paradigm of ecological intensification in African smallholder agriculture. Field Crops Research 2013, 143, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aikins, S.H.M.; Afuakwa, J.J. Effect of four different tillage practices on soil physical properties under cowpea. Agriculture and Biology Journal of North America 2010, 1(4), 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anang, B.T.; Mensah, F.; Asante, B.O. Farmers’ perception and adaptation to climate change: Evidence from cocoa-based agroforestry systems in Ghana. Environmental Management 2020, 66, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, M.R.; Ofori-Frimpong, K.; Afrifa, A.A. Evaluation of cocoa pod husk compost as fertilizer for cocoa production. Ghana Journal of Agricultural Science 2001, 34, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, J.; Muschler, R.; Kass, D.; Somarriba, E. Shade management in coffee and cacao plantations. Agroforestry Systems 1998, 38(1), 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tscharntke, T.; Clough, Y.; Bhagwat, S.A.; Buchori, D.; Faust, H.; Hertel, D.; et al. Multifunctional shade-tree management in tropical agroforestry landscapes – A review. Journal of Applied Ecology 2011, 48(3), 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengot, L.; Barbieri, P.; Andres, C.; Milz, J.; Schneider, M. Cacao agroforestry systems have higher return on labor compared to full-sun monocultures. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2016, 36, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaser, W.J.; Oppong, J.; Hart, S.P.; et al. Shade trees in cocoa systems increase productivity by improving soil fertility and moisture retention. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2018, 257, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaast, P.; Somarriba, E. Trade-offs between crop intensification and ecosystem services: The role of agroforestry in cocoa cultivation. Environmental Sustainability 2014, 6(1), 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niether, W.; Jacobi, J.; Blaser, W.J.; Andres, C.; Armengot, L. Cocoa agroforestry systems versus monocultures: A multi-dimensional meta-analysis. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2020, 295, 106891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, K.A.; et al. Impact of shade and soil management on cocoa productivity in Ghana. Agroforestry Systems 2021, 95(4), 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanlauwe, B.; et al. Integrated soil fertility management in sub-Saharan Africa: Unifying principles, practices and policy recommendations. Advances in Agronomy 2015, 132, 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei-Nsiah, S.; Kuyper, T.W. The yield gap of major food crops and its implications for food security in Ghana. Food Security 2014, 6, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.E.; et al. Cocoa agroforestry systems can contribute to climate change mitigation through improved soil health. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 263, 110384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fobane, J.L.; et al. Assessment of soil organic carbon under different cocoa management systems in Cameroon. Land Degradation & Development 2022, 33(8), 1273–1287. [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, R.; et al. Precision cocoa production in Ghana: Challenges and opportunities. Ghana Journal of Agricultural Science 2023, 58(1), 12–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kooistra, L.; Clevers, J.G.P.W. Remote sensing of environmental variables for precision agriculture: A review. Agricultural Systems 2016, 149, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.; Gaston, K.J. Lightweight unmanned aerial vehicles will revolutionize spatial ecology. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2013, 11(3), 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Hubbard, N.; Loudjani, P. Precision agriculture: An opportunity for EU farmers. Joint Research Centre Technical Report 2014, EUR 26578. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sensing of Environment 1979, 8(2), 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannari, A.; Morin, D.; Bonn, F.; Huete, A.R. A review of vegetation indices. Remote Sensing Reviews 1995, 13(1–2), 95–120. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.R.; Rock, B.N. Detection of changes in leaf water content using near- and middle-infrared reflectances. Remote Sensing of Environment 1989, 30(1), 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, J.G.P.W.; et al. Derivation of leaf area index from red and near-infrared reflectances using canopy reflectance models. Remote Sensing of Environment 1994, 50(3), 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.D.; Idso, S.B.; Reginato, R.J.; Pinter, P.J. Canopy temperature as a crop water stress indicator. Water Resources Research 1981, 17(4), 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.S.; Clarke, T.R.; Inoue, Y.; Vidal, A. Estimating crop water deficit using the relation between surface–air temperature and spectral vegetation index. Remote Sensing of Environment 1994, 49(3), 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Lan, Y.; Xu, C.; Liang, D. UAV-based multispectral remote sensing for precision agriculture: A comparison between different sensors. Sensors 2018, 18(7), 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, W.H.; Steppe, K. Perspectives for remote sensing with unmanned aerial vehicles in precision agriculture. Trends in Plant Science 2019, 24(2), 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Sánchez, J.; Peña, J.M.; de Castro, A.I.; López-Granados, F. Multi-temporal mapping of the vegetation fraction in early-season wheat fields using images from UAV. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2014, 103, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.; Lucieer, A.; Malenovský, Z.; Turner, D.; Vopěnka, P. Assessment of forest structure using two UAV techniques: A comparison of airborne laser scanning and structure from motion (SfM) point clouds. Forests 2016, 7(3), 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swatantran, A.; Dubayah, R.; Roberts, D.; Hofton, M.; Blair, J.B. Mapping biomass and stress in the Sierra Nevada using LiDAR and hyperspectral data fusion. Remote Sensing of Environment 2011, 115(11), 2917–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalponte, M.; Ørka, H.O.; Ene, L.T.; Gobakken, T.; Næsset, E. Tree crown delineation and tree species classification in boreal forests using hyperspectral and ALS data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2014, 140, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesano, P.M.; Cook, B.D.; Sun, G.; et al. Spaceborne LiDAR and radar remote sensing of forest biomass and structure. Forest Ecology and Management 2015, 358, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Kooistra, L. Using hyperspectral remote sensing data for retrieving canopy chlorophyll and nitrogen content. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2012, 5(2), 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, S.; Bendoula, R.; Hadoux, X.; Féret, J.-B.; Gorretta, N. A comparison of canopy reflectance models to estimate canopy chlorophyll content of wheat from hyperspectral measurements. Remote Sensing of Environment 2016, 174, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, O.; Skidmore, A.K. Narrow band vegetation indices overcome the saturation problem in biomass estimation. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2004, 25(19), 3999–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrelst, J.; Camps-Valls, G.; Muñoz-Marí, J.; Rivera, J.P.; Veroustraete, F.; Clevers, J.G.P.W.; Moreno, J. Optical remote sensing and the retrieval of terrestrial vegetation bio-geophysical properties – A review. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2015, 108, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Niu, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, D.; Wu, M.; Zhao, W. Remote estimation of canopy height and aboveground biomass of maize using LiDAR data. Remote Sensing 2015, 7(11), 15298–15314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendig, J.; Bolten, A.; Bareth, G. UAV-based imaging for multi-temporal, very high-resolution crop surface models to monitor crop growth variability. Photogrammetrie, Fernerkundung, Geoinformation 2013, 2013(6), 551–562. [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, K.; Hugenholtz, C.H. Remote sensing of the environment with small, unmanned aircraft systems (UASs), part 1: A review of progress and challenges. Journal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems 2014, 2(3), 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelong, C.C.D.; Burger, P.; Jubelin, G.; Roux, B.; Labbé, S.; Baret, F. Assessment of unmanned aerial vehicles imagery for quantitative monitoring of wheat crop in small plots. Sensors 2008, 8(5), 3557–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasen, H.; Burkart, A.; Bolten, A.; Bareth, G. Generating 3D hyperspectral information with lightweight UAV snapshot cameras for vegetation monitoring: From camera calibration to quality assurance. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2015, 108, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, Q.; Chen, L.; Tang, L.; Han, J.; Li, N.; Yu, Q. A deep learning-based approach for UAV imagery in estimating leaf nitrogen concentration. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2020, 92, 102183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2018, 147, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Du, K.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Z. Transfer learning for deep learning-based classification of high-resolution agricultural images. Remote Sensing 2019, 11(3), 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlingaryan, A.; Sukkarieh, S.; Whelan, B. Machine learning approaches for crop yield prediction and nitrogen status estimation in precision agriculture: A review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2018, 151, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakos, K.G.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Machine learning in agriculture: A review. Sensors 2018, 18(8), 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Gonzalez, A.; Singh, A.; Fritschi, F.B. Yield estimation in maize using UAV-based multispectral and RGB imagery. Remote Sensing 2021, 13(6), 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Liu, S.; Baret, F.; Hemerlé, M.; Comar, A. Estimates of plant density of wheat crops at emergence from very low altitude UAV imagery. Remote Sensing of Environment 2017, 198, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, X.; Dong, Z.; Guo, W. Estimation of leaf area index using airborne hyperspectral LiDAR data: A case study in maize. Remote Sensing 2020, 12(12), 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Tang, W.; Peng, Y.; Gong, Y.; Dai, C.; Chai, R.; Liu, K. Remote estimation of leaf area index in maize using hyperspectral data and machine learning. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 164, 104891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Tang, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Xie, Q. UAV-based multispectral remote sensing for precision nitrogen management in maize. Precision Agriculture 2021, 22(3), 782–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Integrating multisource remote sensing data for crop classification and mapping using deep convolutional neural networks. Remote Sensing 2020, 12(14), 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.K.; Bali, S.K. A review of methods to map nitrogen availability in agricultural soils using optical sensors. Advances in Agronomy 2018, 152, 71–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, C. Deep learning-based crop disease recognition with UAV imagery. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 178, 105759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, H.S.; Zhang, J.; Lofquist, A.; Assefa, T.; Sarkar, S.; Ackerman, D.; Singh, A.; et al. A real-time phenotyping framework using UAV imagery for soybean yield prediction. Remote Sensing 2017, 9(10), 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbedo, J.G.A. A review on the use of deep learning for agricultural image analysis. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 153, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Pu, R.; Gonzalez-Moreno, P.; Yuan, L.; Wu, K.; Huang, W. Monitoring plant diseases and pests through remote sensing technology: A review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2019, 165, 104943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J. Estimation of soil organic carbon in croplands using UAV hyperspectral imagery and machine learning. Remote Sensing 2021, 13(2), 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sishodia, R.P.; Ray, R.L.; Singh, S.K. Applications of remote sensing in precision agriculture: A review. Remote Sensing 2020, 12(19), 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. LiDAR: An important tool for next-generation phenotyping technology of high potential for plant phenomics. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2015, 119, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Gonzalez, A.; Singh, A.; et al. Integration of UAS and AI models for cocoa yield prediction in tropical systems. Drones 2023, 7(4), 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, A.; Walsh, K.B.; Wang, Z.; McCarthy, C. Deep learning for real-time fruit detection and orchard yield estimation: Benchmarking of 'MangoYOLO'. Precision Agriculture 2019, 20(6), 1107–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyarko, B. N. E.; Kolo, S.; Asseu, O. Improved YOLOv5m model based on Swin Transformer and K-means++ for cocoa tree disease detection . Journal of Plant Protection Research 2024, 64(3), 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adisa, R.S.; Olatokunbo, A.; Oyesola, O.B. Digital inclusion and ICT literacy among rural farmers in Nigeria: Implications for sustainable agriculture. Information Development 2021, 37(2), 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munthali, K.G.; Thierfelder, C.; Cheesman, S. Smallholder farmers and regenerative agriculture: Pathways for scaling climate-smart innovations in Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14(5), 2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, J., Sona, G., Torres-Sánchez, J., Pérez-Ortiz, M., Nieto, H., Mazzia, V., & De Lima, R.S. (2019). UAVid: A semantic segmentation dataset for UAV imagery. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, 165, 108–122. [CrossRef]

- Daum, T.; Birner, R. Agricultural mechanization in Africa: Insights from Ghana’s experience. Food Security 2020, 12, 937–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraiti, N.; van der Linden, S.; et al. Classifying full-sun cocoa in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana with limited reference data (Sentinel-2 + ML). Remote Sensing 2024, 16(3), 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammoglia, S.K.; Rojas-Bondioli, C.; et al. High-resolution multispectral and RGB dataset from UAV flights over cocoa in Côte d’Ivoire (2022 season). Data in Brief 2024, 54, 110002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipper, L.; Thornton, P.; Campbell, B.M.; Baedeker, T.; Braimoh, A.; Bwalya, M.; et al. Climate-smart agriculture for food security. Nature Climate Change 2014, 4, 1068–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Gill, M.S.; Kumar, A. Precision agriculture: Technologies and global trends. Agronomy 2021, 11(8), 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Bharucha, Z.P. P. Sustainable intensification in agricultural systems. Annals of Botany 2014, 114(8), 1571–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2015, 200, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flichman, G. Systems modelling and optimization for sustainable agriculture. Agricultural Systems 2017, 157, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei-Nsiah, S.; et al. The effects of regenerative practices on soil and yield resilience under drought-prone cocoa systems. Agroforestry Systems 2024, 98(2), 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Payments for Ecosystem Services and Carbon Sequestration: Guidelines for Agricultural Systems; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. West Africa Cocoa Resilience and Digital Transformation Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Financing Sustainable Cocoa Value Chains in Africa; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Database / Source |

Search String (Excerpt) |

Records Retrieved | After De-duplication |

Full Texts Reviewed |

Studies Included |

Primary Reasons for Exclusion |

|

Scopus + Web of Science |

(“Cocoa” AND “Regenerative Agriculture” AND “UAS” OR “Drone” OR “ Remote Sensing”) |

312 | 248 | 85 | 40 | Conducted outside West Africa (22); Insufficient methodological detail (15); Duplicates (8) |

| ScienceDirect + AGRICOLA | (“Cocoa” AND “Artificial Intelligence” OR “Machine Learning” OR “Deep Learning”) | 245 | 198 | 70 | 30 | Non-peer-reviewed (14); General AI applications outside agriculture (20) |

| Google Scholar + Institutional Repositories (FAO, ICCO, COCOBOD, UNDP) | (“Sustainable Cocoa” OR “Precision Agriculture” OR “Climate-Smart Farming”) | 233 | 175 | 61 | 20 | Grey literature (13); Incomplete data or non-quantitative results (18) |

| Totals | — | 790 | 621 | 216 | 90 | — |

| Country | Annual Production (2023) | Average Yield (kg (ha⁻¹) | Yield Trend (2000–2023) |

Key Agronomic Constraints |

Regenerative / Technological Potential |

| Côte d’Ivoire |

~ 2.3 million t | 550–700 | –5 % (stagnation) | Soil acidification; aging trees; pest and disease pressure | Agroforestry rehabilitation; UAS shade optimization |

| Ghana | 700–900 thousand t | 450–800 | –12 % (decline since 2010) | CSSVD; low K; poor organic matter | Composting; UAS thermal stress detection; AI nutrient mapping |

| Nigeria | 300–350 thousand t | 350–550 | +4 % (marginal increase) | Low input use; fragmented farms | UAS soil monitoring; AI yield forecasting |

| Cameroon | 250–300 thousand t | 400–600 | –8 % (variable rainfall effect) | Land degradation; erratic rainfall | Precision irrigation via UAS; soil carbon restoration |

| Togo | 70–90 thousand t | 350–500 | –10 % (stagnant) | Soil erosion; nutrient loss; aging plantations | Cover cropping; drone-assisted soil mapping |

| Country | Production (t yr⁻¹) | Yield (kg·ha⁻¹) | Key Constraints / Regenerative Opportunities |

| Côte d’Ivoire | 2.3 M [1,4] | 500–700 [4,6] | Soil fertility decline, nutrient mining, deforestation, pH 6.2→5.4, aging trees → Agroforestry rehab, composting, UAS shade mapping, AI nutrient modeling [7,9,11,12,15,19,83] |

| Ghana | 0.7–0.9 M [1,4,5] | 450–800 [6,8] | CSSVD, black pod, low K (<0.25 cmol·kg⁻¹), low OM, limited compost → Composting, UAS thermal & stress mapping, AI yield models [9,10,45,48,60,83,125] |

| Nigeria | 0.28–0.32 M [1,4] | 350–550 [6,8] | Low fertilizer (<5 kg NPK·ha⁻¹), fragmentation, poor varieties, weak extension → UAS soil/canopy monitoring, drone coops, AI forecasting [4,5,9,10,19,83,120] |

| Cameroon | 0.25 M [1,4] | 400–600 [6,8] | Old trees, erosion, low inputs, shade imbalance → Regenerative agroforestry, mulching, multispectral UAS vigor mapping [9,11,13,47,81,83] |

| Togo | 0.04–0.07 M [1,4,5] | 300–500 [6,8] | Degraded soils, pests, low fertilizer access, aging farms → Green manures, drone mapping coops, AI soil rehab advisory [4,5,11,13,19,81,125] |

|

Model / Algorithm |

Input Data | Key Function | Accuracy (%) | Reference |

| CNN | RGB / Multispectral images |

Canopy health & black pod detection |

90–95 | [120,121,122,123] |

| Random Forest (RF) | NDVI + Thermal data | Disease segmentation & vigor classification |

85–90 | [124] |

| Hybrid CNN–RF | RGB + LiDAR | Shadow-resilient canopy analysis | 92–94 | [124] |

| SVM | NDVI + EVI | Nutrient-stress classification | 80–85 | [125,145] |

| Algorithm / Model | Primary Function | Input Data Types | Output / Use Case | Example / West African Context (with citations) |

| CNN (Convolutional Neural Network) | Disease and nutrient-stress detection | RGB, multispectral, thermal | Early stress classification; canopy-health mapping | Applied in Ghana for early detection of black pod and nutrient deficiency using drone imagery [120,121,122,123]. |

| Random Forest (RF) | Classification and yield estimation | NDVI, canopy height, soil properties | Spatial yield-zone prediction | Used in Nigeria for predicting sub-field yield variability and nutrient demand [124,125,126]. |

| Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) | Non-linear yield modeling | Multispectral and rainfall data | Yield prediction under variable rainfall | Applied in Côte d’Ivoire for agroclimatic yield-response modeling [125,126]. |

| LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory Network) | Temporal yield forecasting | Multi-season NDVI and rainfall time series | Multi-year yield-trend analysis | Tested in Ghana and Cameroon for seasonal cocoa-yield prediction [127]. |

| TCN (Temporal Convolutional Network) | Stress-risk prediction | NDVI, canopy temperature, LiDAR | Dynamic climate- and pest-risk mapping | Demonstrated >85% accuracy for stress detection in Cameroon [128,129]. |

| Hybrid CNN–RF Models | Enhanced classification robustness | RGB + multispectral | Combined disease/stress mapping | Integrated with UAS data to improve classification accuracy by 5–10% under variable illumination [124,130]. |

| Focus Area | Strategic Actions | Outcomes & Timeline | References |

| Research | Develop localized, multi-season datasets integrating multispectral, thermal, and LiDAR imagery; conduct cross-zone AI model validation |

Accurate, scalable predictive models; 1–3 years |

[120,121,122,123,125,126,127], [131] |

| Institutions | Establish cooperative drones and data hubs; build capacity for youth, agronomists, and extension staff |

Improved digital literacy and farmer inclusion; 2–5 years |

[83,130,131,132] |

| Policy | Integrate RA–UAS–AI framework into national cocoa plans; enact data-governance and carbon-credit incentives |

Mainstreamed regenerative adoption; 5–10 years | [132,133] |

| Country | Primary Application | Yield Gain (%) | SOC Change (%) | Model Accuracy (%) | References |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Canopy-height & carbon-accounting analytics |

18–25 | +18 | 93 | [137,138] |

| Ghana | NDVI-guided compost & mulch placement |

15–22 | +20 | 85–90 | [134,135,136] |

| Nigeria | CNN–RF disease detection & stress alerts | 20–25 | +17 | > 90 | [139,140] |

| Cameroon | LiDAR-terrain-based soil–water management |

10–20 | +15 | 76 | [141,142] |

| Togo | Cooperative open-source canopy monitoring |

10–15 | +20 | 85–88 | [143] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).