Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

17 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

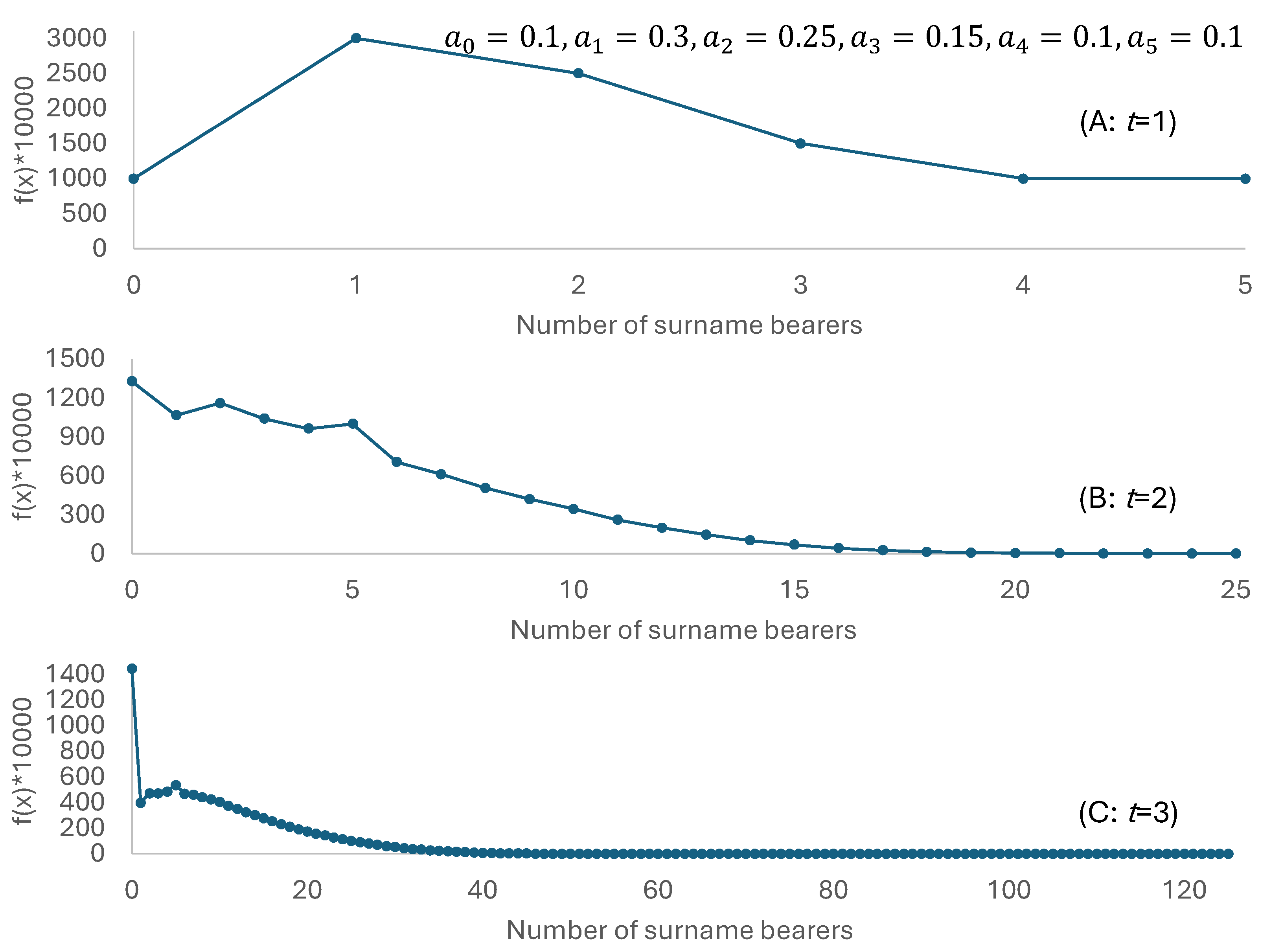

2. A Branching Process with Empirical Reproductive Success

2.1. Extinction Probability Q

2.2. Extinction Time T and Var(T)

3. A branching Process with Reproductive Success Following a Poisson Distribution

3.1. Extinction Probability Q

3.2. Extinction Time

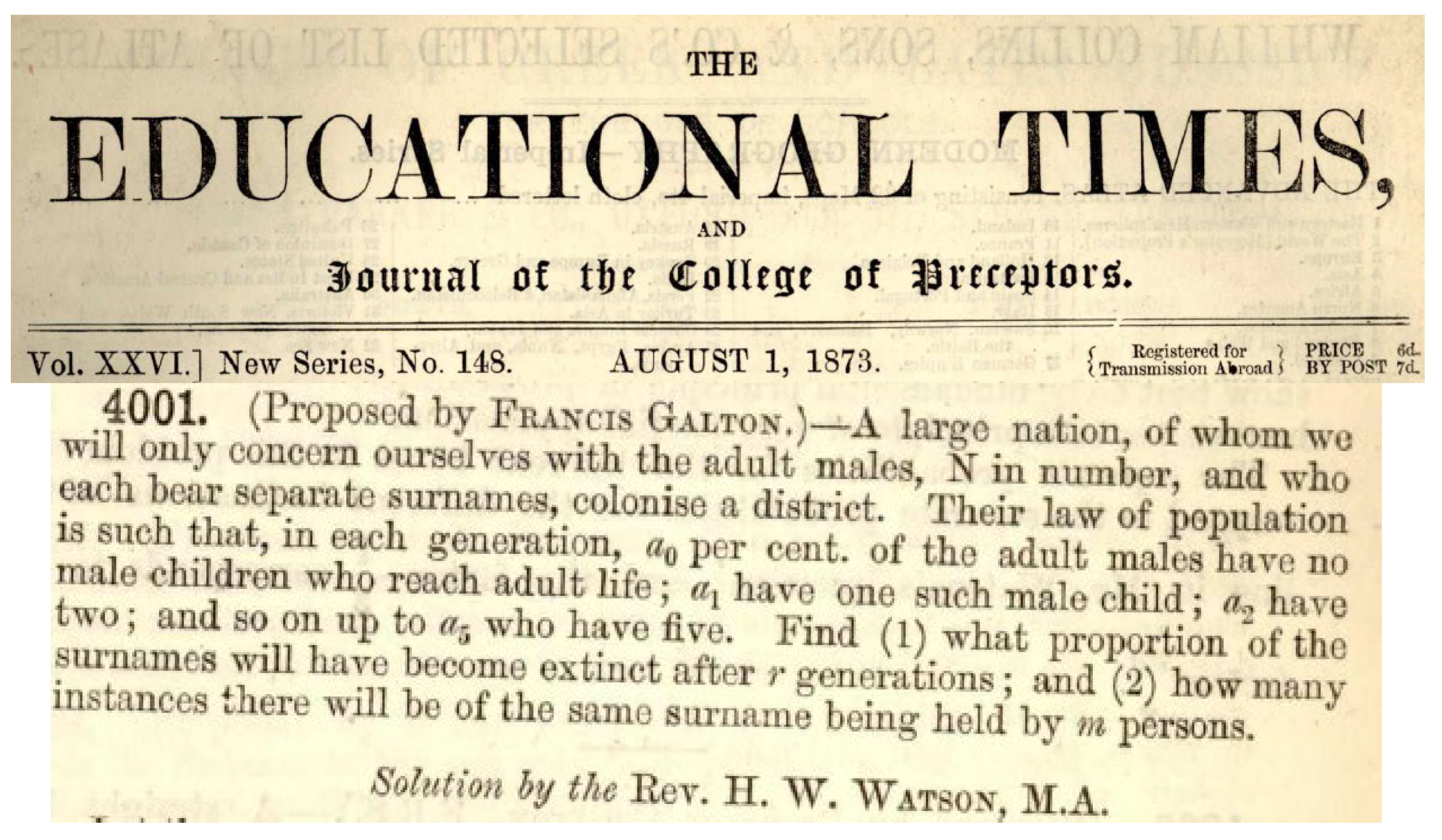

4. Come Back to the Galton Questions

5. Recent Extensions and Applications

Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feller, W. , An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications. Wiley series in probability and mathematical statistics, ed. R.A. Bradley, et al. Vol. 1. 1968, New York: Wiley. 509.

- Galton, F. and H.W. Watson, On the probability of extinction of families. Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 1874, 4, 138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.A. , On the dominance ratio. Proc. Royal. Soc. Edin. 1922, 42, 321–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, J.B.S. , A mathematical theory of natural and artificial selection. Part V. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 1927, 23, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.E. , The Theory of Branching Processes. 1963: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Athreya, K.B., P. E. Ney, and P.E. Ney, Branching Processes. 2004, Mineola: Dover Publications. 287.

- Freeman, A. and X. Xia, Phylogeographic Reconstruction to Trace the Source Population of Asian Giant Hornet Caught in Nanaimo in Canada and Blaine in the USA. Life 2024, 14, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. , Phylogeographic Analysis for Understanding Origin, Speciation, and Biogeographic Expansion of Invasive Asian Hornet, Vespa velutina Lepeletier, 1836 (Hymenoptera, Vespidae). Life 2024, 14, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.B.R. and P. Olofsson, A branching process model of evolutionary rescue. Math Biosci 2021, 341, 108708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. , Theoretical evolutionary genetics. 2019, Seattle, Washington: Self-published.

- Corless, R.M. , et al., On the Lambert W function. Advances in Computational Mathematics 1996, 5, 329–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viceconte, G. and N. Petrosillo, COVID-19 R0: Magic number or conundrum? Infect Dis Rep 2020, 12, 8516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, G.C. Sex and evolution; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard Smith, J. , The Evolution of Sex; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Haccou, P., P. Jagers, and V.A. Vatutin, Branching Processes: Variation, Growth, and Extinction of Populations. Cambridge Studies in Adaptive Dynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cloez, B. , et al., A bayesian version of Galton–Watson for population growth and its use in the management of small population. MathematicS In Action. Maths Bio 2023, 12, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sagitov, S. , Critical Galton–Watson Processes with Overlapping Generations. 2021, 36, 87–110.

| T | qt | qt−qt-1 | 1-qt | (2t+1)(1-qt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| 2 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

| 3 | 0.808 | 0.108 | 0.192 | 1.344 |

| 4 | 0.872973 | 0.064973 | 0.127027 | 1.143245 |

| 5 | 0.914308 | 0.041335 | 0.085692 | 0.94261 |

| 6 | 0.941484 | 0.027176 | 0.058516 | 0.760704 |

| .. | … | … | … | … |

| 37 | 0.999999 | 3.75E-07 | 8.74E-07 | 6.56E-05 |

| 38 | 0.999999 | 2.62E-07 | 6.12E-07 | 4.71E-05 |

| 39 | 1 | 1.84E-07 | 4.28E-07 | 3.38E-05 |

| 40 | 1 | 1.28E-07 | 3E-07 | 2.43E-05 |

| .. | … | … | … | … |

| 92 | 1 | 1.22E-15 | 2.55E-15 | 4.72E-13 |

| 93 | 1 | 0 | 1.89E-15 | 3.53E-13 |

| 94 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| W0(z) | Q | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -0.36788 | -1 | 1 |

| 1.01 | -0.36786 | -0.99014 | 0.98034 |

| 1.1 | -0.36616 | -0.90630 | 0.82391 |

| 1.2 | -0.36143 | -0.82353 | 0.68627 |

| 1.3 | -0.35429 | -0.75013 | 0.57702 |

| 1.4 | -0.34524 | -0.68461 | 0.48901 |

| 1.5 | -0.33470 | -0.62581 | 0.41720 |

| 2 | -0.27067 | -0.40637 | 0.20319 |

| 3 | -0.14936 | -0.17856 | 0.05952 |

| 4 | -0.07326 | -0.07931 | 0.01983 |

| 5 | -0.03369 | -0.03489 | 0.00698 |

| 10 | -0.00045 | -0.00045 | 0.00004 |

| T | qt | qt − qt-1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0000000000 | |

| 1 | 0.3328710837 | 0.332871084 |

| 2 | 0.4800611401 | 0.147190056 |

| 3 | 0.5644334773 | 0.084372337 |

| 4 | 0.6193261945 | 0.054892717 |

| 5 | 0.6578744403 | 0.038548246 |

| 6 | 0.6863702213 | 0.028495781 |

| 7 | 0.7082254834 | 0.021855262 |

| 8 | 0.7254580952 | 0.017232612 |

| … | … | … |

| 999 | 0.8238658564 | 0 |

| 1000 | 0.8238658564 | 0 |

| T | ||

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 0.1000000000 | 0.1000000000 |

| 2 | 0.1326610000 | 0.0326610000 |

| 3 | 0.1445833203 | 0.0119223203 |

| 4 | 0.1491044603 | 0.0045211400 |

| 5 | 0.1508434063 | 0.0017389461 |

| … | … | … |

| 23 | 0.1519416037 | 0.0000000001 |

| 24 | 0.1519416038 | 0.0000000000 |

| 25 | 0.1519416038 | 0.0000000000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).