1. Introduction

Despite significant advances in alternative drug-delivery routes, the oral route remains the most popular for paediatric therapy due to accurate dosing, low cost, non-invasiveness and ease of administration [

1]. However, conventional oral medicines available on the market are predominantly designed for adults [

2,

3,

4]. Children require different oral dosage forms than adults because of differences in swallowing ability, taste and texture preferences, and dosing requirements [

5,

6]. The paediatric population (1–17 years) is heterogeneous, spanning newborns to adolescents [

7]. Consequently, many formulations available worldwide are not age-appropriate; driven by the larger adult market, products are typically designed for adult patients. To fulfil dosing requirements in paediatrics, off-label or unlicensed use of adult formulations has become common (e.g., splitting tablets, crushing tablets, or dispersing capsule contents in water or other liquids), which can lead to adverse clinical consequences [

6,

8]. Extemporaneous dispensing is also widespread, yet limitations such as uncertain stability, imprecise dosing and inconsistent preparation make it challenging for pharmacists, practitioners and carers [

9].

Although liquid formulations are often considered the principal option for paediatric drug delivery, they can be poorly suited due to strict storage conditions, high transportation costs and the need for potable water for reconstitution [

10]. Non-liquid formulations (i.e., tablets and capsules) offer a viable alternative [

11,

12], but are not suitable for infants and toddlers who cannot safely chew or swallow solid forms [

13,

14]. Developing age-appropriate formulations is challenging because a wide range of clinical and pharmaceutical considerations must be addressed to ensure efficacy, safety and quality [

15]. Additional challenges arise from pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles, which vary substantially across development, necessitating age-tailored dosing. Dosing flexibility is therefore essential to provide appropriate doses across all paediatric age groups [

16].

To better meet paediatric needs, in 2007 the World Health Organization (WHO) called to “make medicines child-size”, emphasising the development of suitable paediatric formulations [

17]. In line with recommendations from the FDA, EMEA and WHO, flexible, child-friendly formulations such as orodispersible tablets (ODTs) may be preferable for paediatric patients [

18]. ODTs can be administered with a small volume of water or another liquid to younger patients [

19]. Following the FDA’s recommendations, pharmaceutical companies and researchers have increasingly developed ODTs to facilitate oral administration and improve convenience [

20]. ODTs are stable as solid dosage forms, particularly within their final packaging, yet disintegrate rapidly in the mouth to form a solution or suspension [

21], providing a pleasant mouthfeel and smooth swallowing [

22]. Drug release from ODTs typically involves rapid tablet disintegration, followed by dissolution and subsequent absorption. ODTs differ from chewable tablets in that they eliminate the need for chewing or concomitant liquid intake [

23], and from effervescent formulations, which require prior dispersion in a glass of liquid before administration [

24]. Owing to these characteristics, ODTs are considered a first-line option for paediatric patients with swallowing difficulties or dysphagia [

25]. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia and Jordan, approximately 58.0% of participants (aged 6–18 years) preferred ODTs over conventional liquids, tablets and capsules [

26]. Additionally, 63% of medical practitioners favoured replacing liquid formulations with suitable ODTs where appropriate [

27].

ODTs combine advantages of both solid and liquid dosage forms by leveraging technologies that enable higher drug loading with acceptable taste and a pleasant mouthfeel [

28]. Despite their commercial success, challenges remain during development, including insufficient mechanical strength, poor palatability due to inadequate taste-masking, prolonged disintegration times, and achieving controlled-release profiles when immediate release is required in paediatric care [

28]. Several reviews have addressed orodispersible dosage forms. For example, in 2015, Marta Slavkova and Jörg Breitkreutz focused on orodispersible formulations to outline future perspectives and potential benefits [

29]. Similarly, Karavasili et al. reported the patent landscape for paediatric-friendly oral drug-delivery formulations and devices, providing insights and future directions [

30]. Another review summarised neonatal/paediatric drug-delivery approaches, discussing hurdles and opportunities in developing age-appropriate formulations [

31]. However, comprehensive synthesis focused specifically on paediatric ODTs, with systematic methods and comparative analysis, appears limited. Accordingly, this review follows PRISMA guidelines [

32] to identify paediatric-relevant ODTs reported between 2015 and 2023, with specific attention to effective taste masking of APIs, optimised disintegration times, and improved bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. In addition, using metadata extracted from included studies, we summarise manufacturing techniques and process considerations, the emergence of natural disintegrants, and modified testing parameters used to evaluate ODTs.

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy, Information Sources and Screening Process

The search plot was developed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines [

32], encompassing identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion. The systematic review protocol was registered with the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (INPLASY) under the registration number INPLASY2025110022. A systematic search of published research articles was conducted from January 2015 to March 2023. An inclusive search plot was implemented across Google Scholar, EMBASE, PubMed, MEDLINE and Scopus. The lead authors executed the searches using the following terms:

“fast dissolving tablet” OR “orodispersible tablets” OR “orally disintegrating tablets” OR “mouth-dissolving tablets” OR “rapid dissolving” AND “Paediatric” OR “Paediatrics” OR “Pediatric” OR “Pediatrics” OR “children”. Titles and abstracts of retrieved records were screened initially, with studies irrelevant to the rationale of this systematic review removed. The full texts of the remaining articles were then examined in detail to assess eligibility, and additional studies not aligned with the review rationale were subsequently excluded.

2.2. Study Selection

The authors independently appraised the suitability of potentially eligible studies. Full texts were then assessed against the review rationale by two reviewers. Disagreements or differences of opinion regarding study eligibility were resolved through conclusive discussion.

2.3. Data Extraction and Collection

Data was extracted using a template form [

33] and the extracted information was tabulated in Microsoft Excel 2019 [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38] including active pharmaceutical ingredients, superdisintegrants/excipients, manufacturing technology, in-vitro/in-vivo disintegration, dissolution testing and overall study characteristics. In addition, based on the list of active pharmaceutical ingredients retrieved in this systematic review, a list of commercially available paediatric products was compiled [

39].

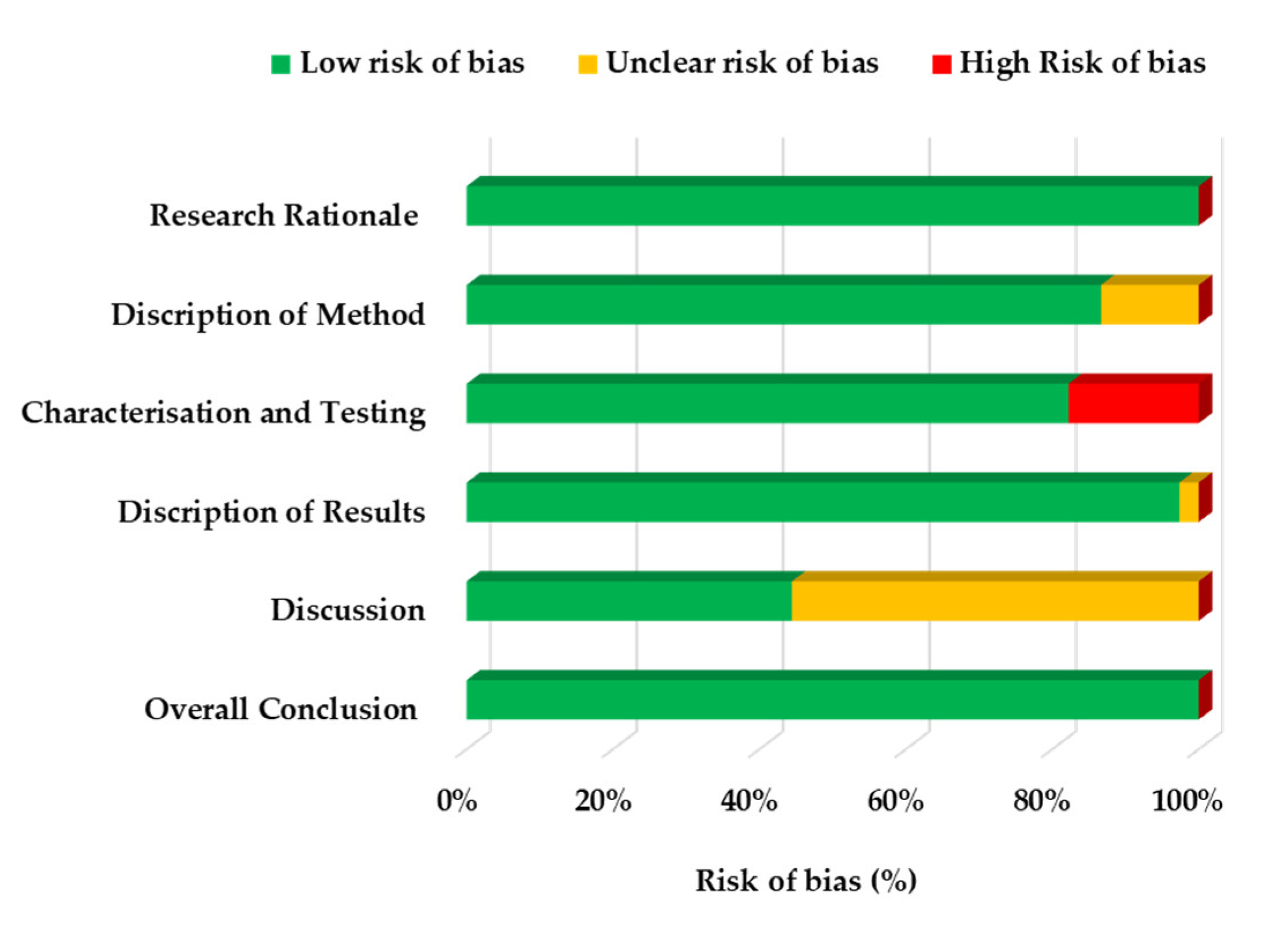

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

To assess risk of bias across all eligible studies, a recently published framework was adopted [

40]. The framework covers six key areas: research rationale, description of methodology, characterisation and testing, description of results, and description of discussion and conclusion,

Table S2 and S3. Two authors independently evaluated risk of bias for each included study and then discussed the assessments with the research team to reach consensus on the findings.

3. Results and Discussion

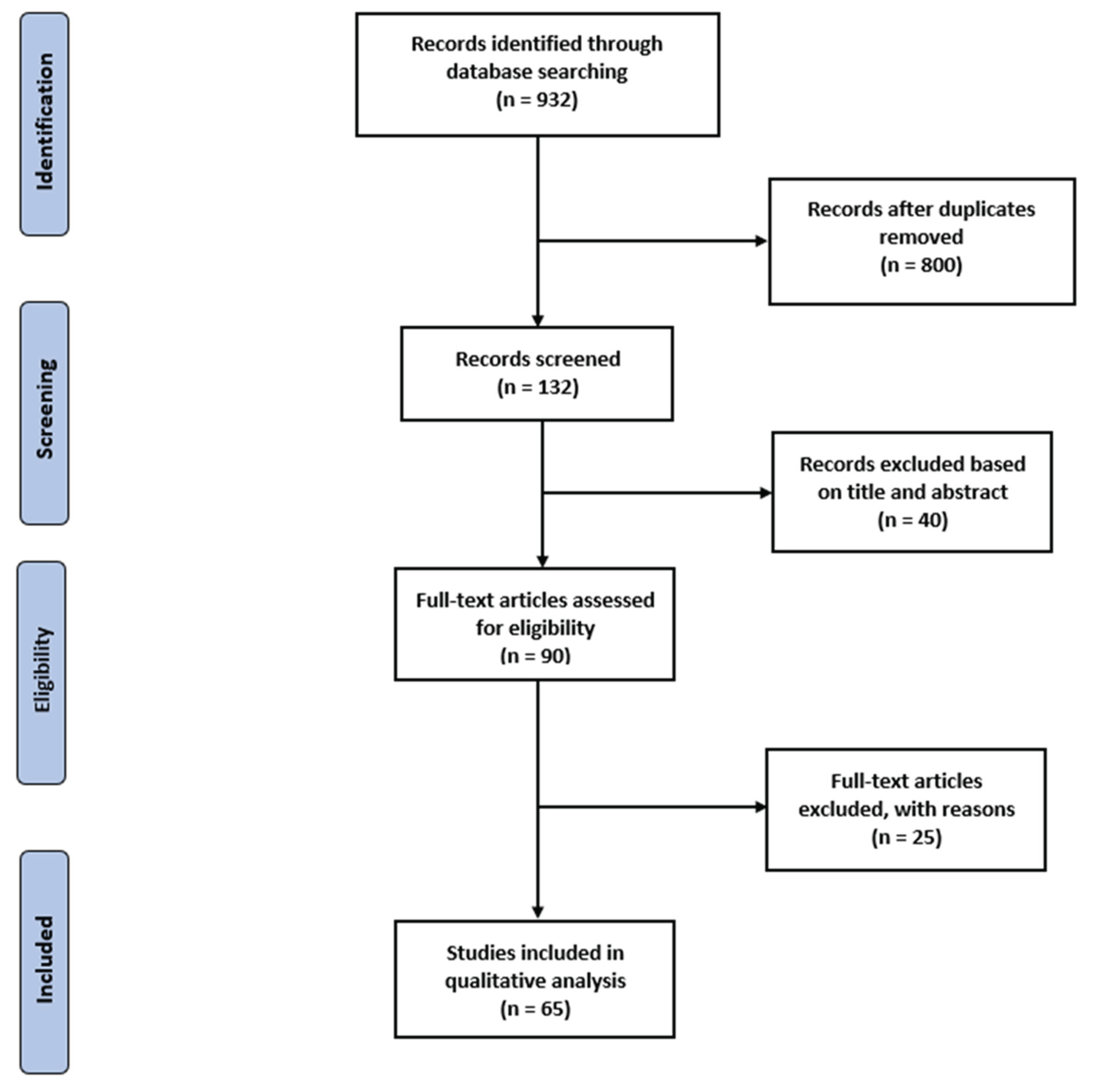

The database search identified 932 records. After de-duplication, 132 unique articles remained for screening. Titles and abstracts were reviewed against the predefined eligibility criteria, after which 90 articles were taken forward for full-text assessment. Following detailed appraisal of the full texts, 25 articles were excluded. Consequently, 65 studies [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105] met the inclusion criteria and were retained for qualitative synthesis and reporting, as depicted in

Figure 1.

The main reason for exclusion was insufficient relevance to paediatric drug delivery and formulation development. Additional common reasons included: studies focusing solely on adult populations; dosage forms other than orodispersible tablets; reports limited to devices, packaging or manufacturing operations without formulation performance data; non-primary research (e.g., narrative reviews, perspectives, editorials or conference abstracts lacking methodological detail); studies outside the defined time window; and records with inadequate data to extract key outcomes. Where disagreements arose during screening or full-text review, these were resolved through discussion to reach consensus.

The included studies were subsequently categorised, and data was extracted using a structured template (

Table S1) aligned to focused domains: (i) the manufacturing technique used to develop ODTs, (ii) disintegration and dissolution testing approaches, and (iii) overall study characteristics. Extraction fields covered the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), excipients/superdisintegrants, key process parameters, disintegration method (compendial or modified), test media and volumes, dissolution endpoints, and relevant quality attributes (e.g., hardness, friability, uniformity), together with any reported palatability or acceptability outcomes. To enhance consistency, terminology and units were harmonised across studies, and where necessary, comparable outcomes (e.g., disintegration time under modified rigs) were normalised and annotated. Data were dual checked for completeness, with discrepancies resolved by discussion and consensus. Detailed study-level extractions describing the summarised characteristics of the eligible studies are given in

Table S4.

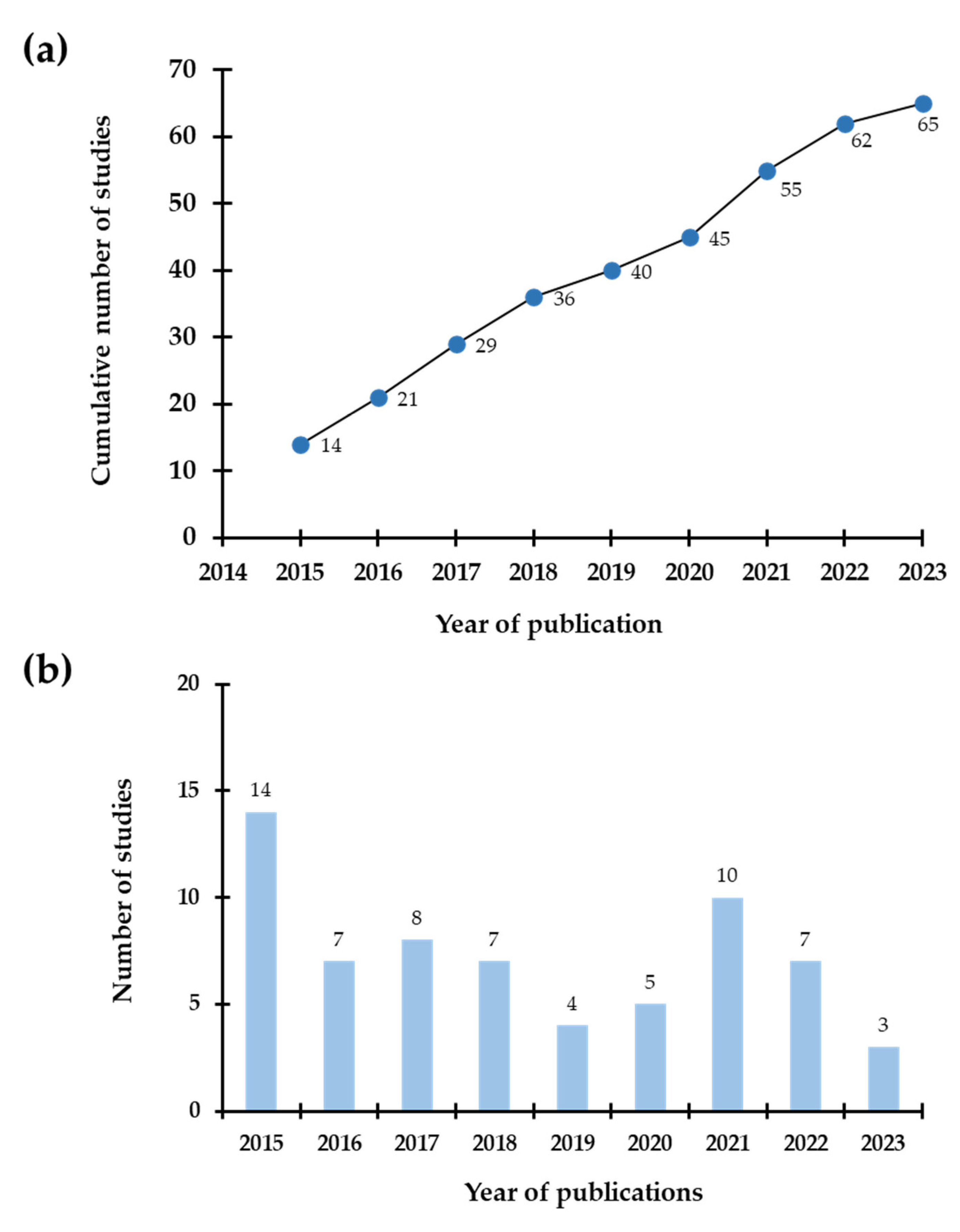

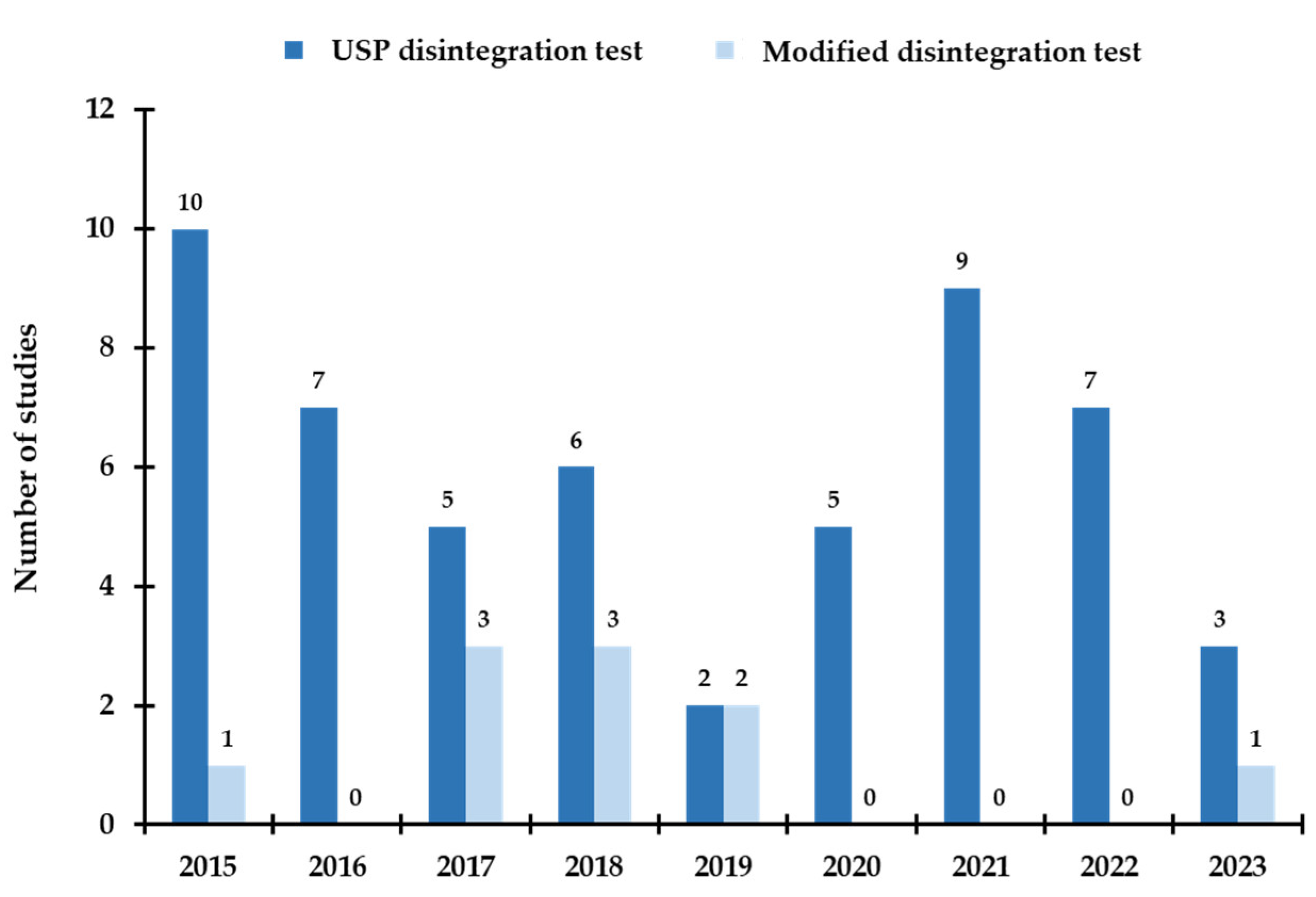

Figure 2 shows a clear upward trajectory in paediatric ODT research over the years.

Figure 2a demonstrates steady, near-linear growth in the cumulative number of publications, indicating sustained engagement with ODTs rather than isolated bursts of interest.

Figure 2b disaggregates counts by calendar year, revealing periodic surges that likely reflect several catalysts: (i) increasing recognition of child-friendly solid oral dosage forms as a priority for acceptability and adherence; (ii) wider availability of superdisintegrants and co-processed excipients; and (iii) the emergence of enabling technologies (e.g., spray-drying, sublimation and early applications of 3D printing) that facilitate dose flexibility and taste-masking. Collectively, these trends suggest the field is maturing, with method development increasingly complemented by application-focused studies in paediatric-relevant APIs and formulation scenarios.

Figure 3 summarises the risk-of-bias assessment across predefined domains. The details of study level scoring are listed in

Table S5. Overall, most studies exhibited low risk, supporting the general credibility of the evidence base. The “testing and characterisation” domain showed the highest proportion of high risk (2.2%), commonly arising from incomplete reporting of test conditions (e.g., media composition/volume, temperature, or rig modifications) or limited replication and variability metrics. “Unclear” risk clustered primarily in the discussion domain (5.0%), with smaller contributions from the results (0.3%) and methodology (1.0%) domains, indicating occasional gaps in narrative integration, justification of design choices, or transparency around inclusion/exclusion of data. These patterns point to remediable reporting issues rather than systematic methodological weaknesses. As the field progresses, adopting consistent templates for analytical method description, declaring any deviations from compendial tests, and providing full datasets should reduce residual bias and improve comparability across studies. Moreover, information regarding the commercial products of those drugs retrieved in this study was tabulated in

Table S6.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias assessment of eligible studies.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias assessment of eligible studies.

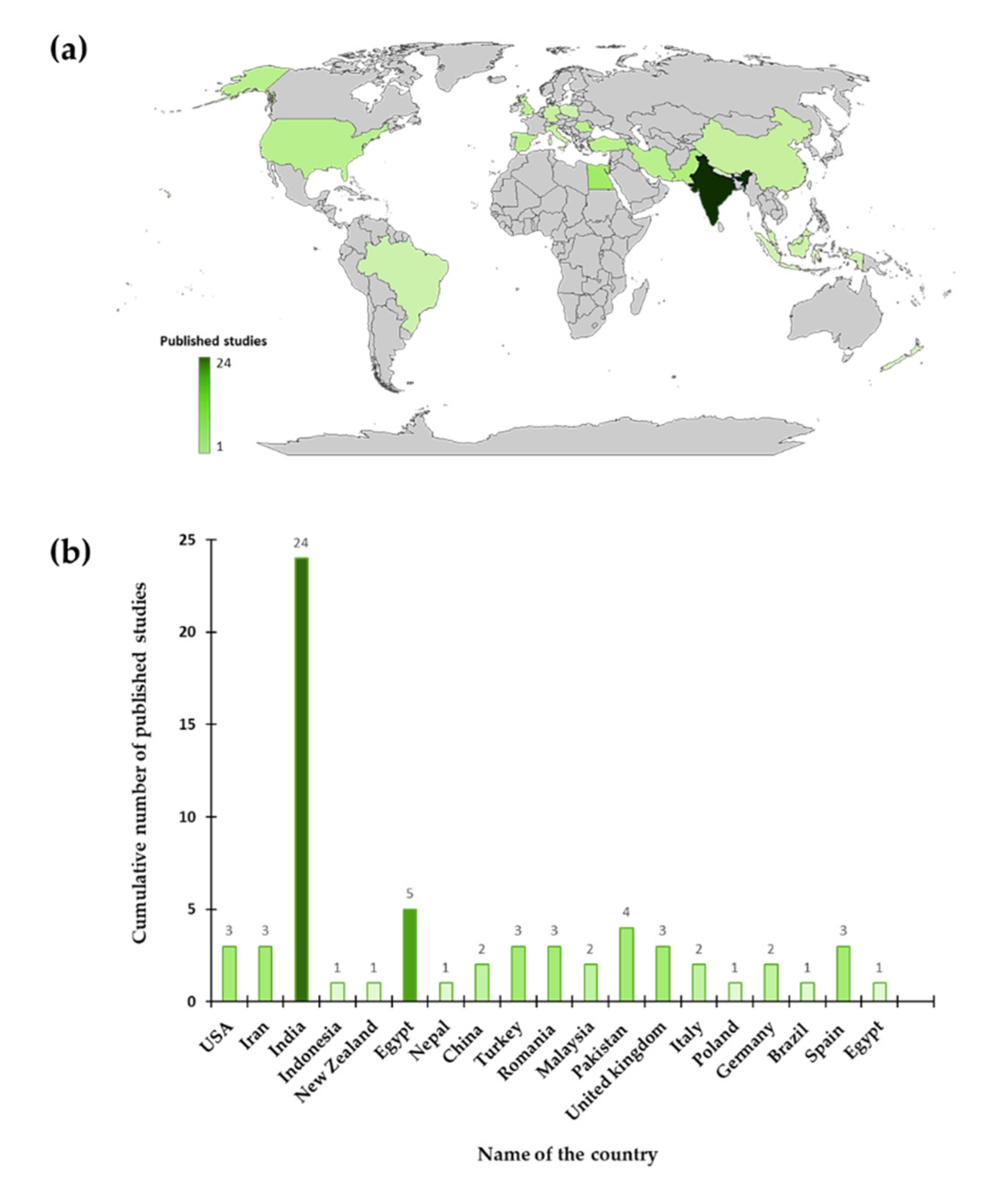

Figure 4a and b shows the global distribution of paediatric ODT publications. India contributed the largest share (n = 24), followed by Egypt (n = 5) and Pakistan (n = 4). Many other countries contributed one to three studies over the same period, reflecting broad, albeit uneven, global participation. The concentration of output in a few countries likely reflects established formulation research hubs, access to excipient and process infrastructure and targeted funding or training programmes in solid dosage-form development. At the same time, the relative scarcity of publications from some high-income and low-income regions suggests opportunities to expand collaborative networks, share standardised testing protocols and build capacity for paediatric-specific formulation science. Considering this geographic skew is important when interpreting generalisability: climatic conditions, supply chains and patient acceptability can vary by region, underscoring the value of multicenter validation and cross-regional replication of promising ODT technologies.

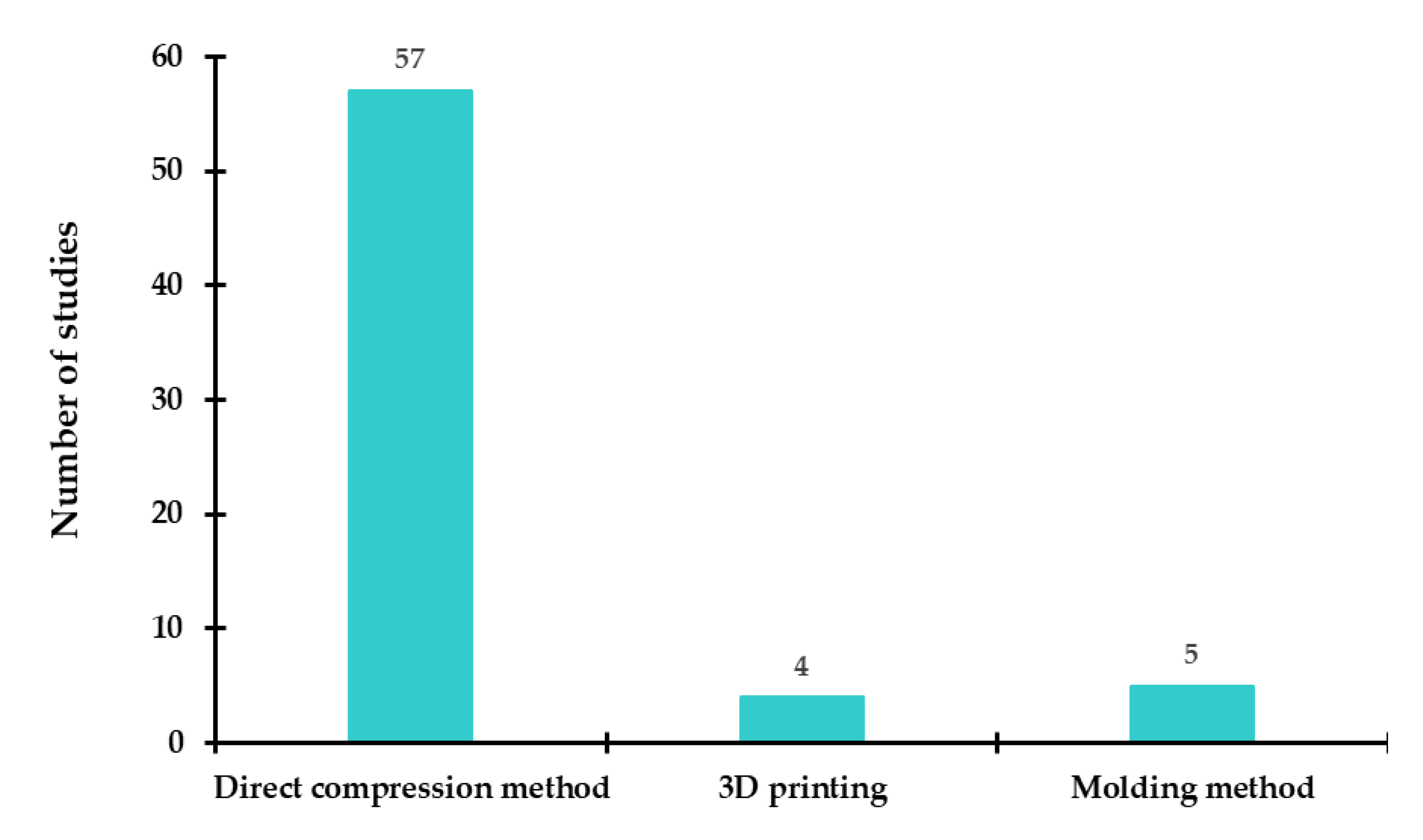

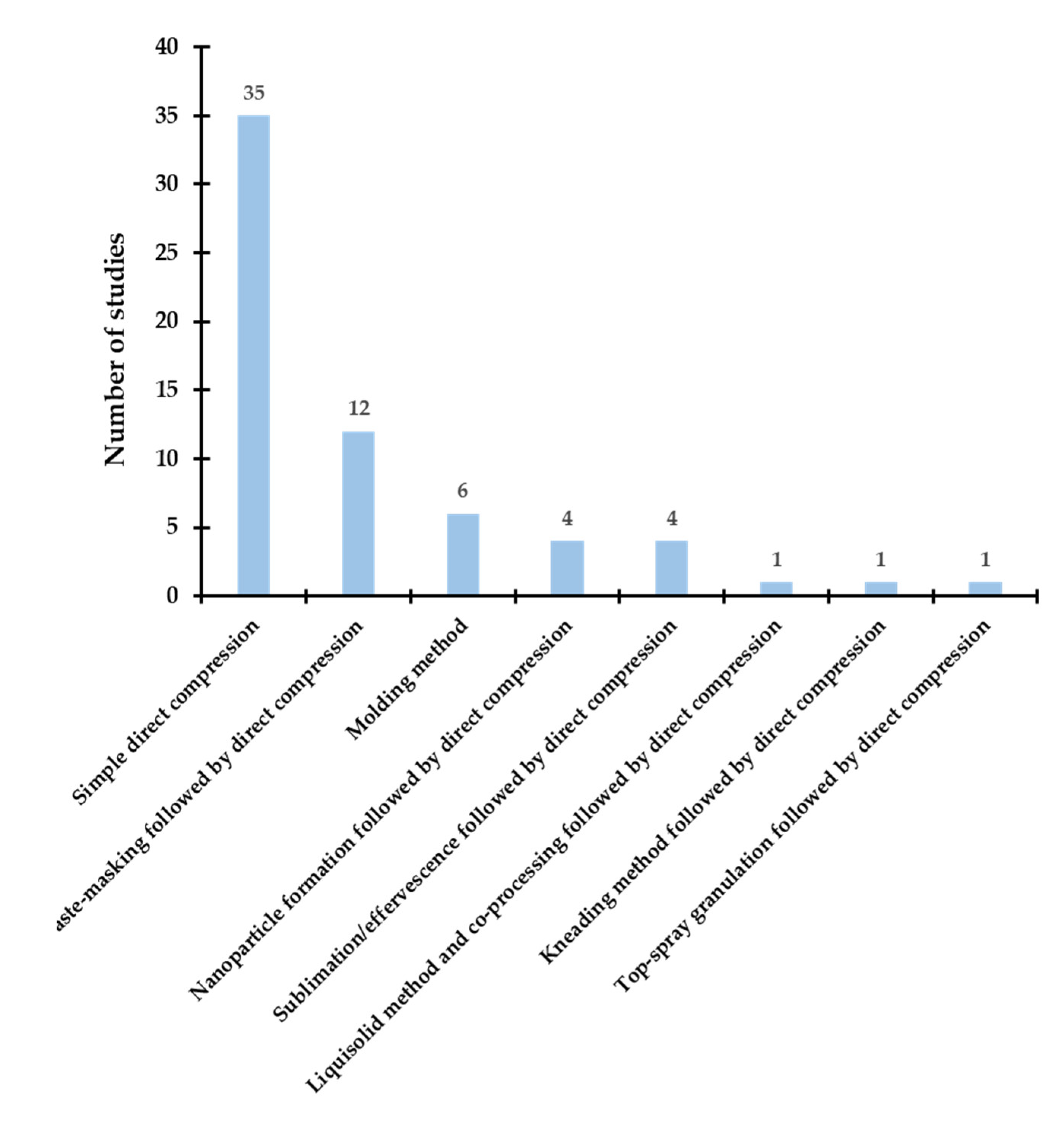

3.1. Techniques and Processes for Developing ODTs

A range of approaches has been employed to develop ODTs; however, direct compression remains the most frequently used route. In several studies, single or combined pre-processing steps—such as freeze-drying, spray-drying, nanoparticle formation and other modification techniques—were applied prior to compression to enhance disintegration, taste-masking or bioavailability.

Figure 5 summarises the overall distribution of techniques reported across the included studies, and detailed study characteristics and processing parameters are tabulated in

Table S1.

Consistent with its widespread industrial adoption, direct compression was the predominant technique identified for paediatric ODTs, reflecting its relative simplicity, cost-effectiveness and scalability: excipients and API are blended and compressed without a wet-granulation step. Powder compaction generally proceeds through four stages, initial powder rearrangement, elastic deformation, plastic deformation and, finally, relaxation/elastic recovery during unloading and ejection [

106]. Rapid disintegration upon contact with saliva is typically achieved through the inclusion of superdisintegrants and/or effervescent components within the compact. Across the eligible studies, APIs were formulated with natural, synthetic or co-processed disintegrants alongside diluents, fillers and/or effervescent systems to improve onset of action, patient acceptability and convenience [

42,

44,

45,

46,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

61,

62,

65,

67,

69,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

78,

79,

84,

85,

86,

89,

90,

93,

94,

96,

98,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104].

Building on this baseline, several studies introduced an intermediate processing step prior to tableting to tackle specific formulation challenges such as bitterness, low solubility or mechanical fragility (

Figure 6). Because ODTs disperse in the oral cavity, bitter APIs require robust taste-masking to preserve palatability and adherence; accordingly, a variety of approaches were used, including fluid-bed coating [

41], coacervation [

58,

71], complexation with ion-exchange resins [

51,

68,

70], combined ion-exchange resin with cyclodextrin [

77], hot-melt extrusion of taste-masked extrudates [

43], solvent-evaporation blends [

49,

50], fabrication of taste-masked composites prior to compression [

59], and bilayer or multilayer polymer coatings that couple pH-independent water-insoluble with water-soluble films to enable immediate release while masking bitterness [

97]. Importantly, these methods were generally compatible with downstream direct compression, allowing taste-masked intermediates to be converted into ODTs without sacrificing processability.

Where taste-masking alone was insufficient, alternative tablet-formation routes were explored. Moulded ODTs were prepared by moistening, dissolving or dispersing the API in a suitable solvent, shaping the wet mass and removing the solvent at ambient pressure. The lower compaction force produces a highly porous matrix and, consequently, rapid disintegration and dissolution [

107]. Nonetheless, a recent head-to-head comparison reported failure of the moulding route for hydrochlorothiazide ODTs owing to content-uniformity issues, whereas an alternative technology met pharmacopoeial requirements [

80,

95]. This limitation has steered interest towards processes that engineer high porosity while maintaining uniformity and dose accuracy. Lyophilised systems represent one such option. Freeze-dried ODTs were reported for fixed-dose combinations (e.g., lopinavir/ritonavir) suited to low-resource settings, offering very fast dispersion—even with as little as 0.5 mL of fluid—and enhanced dissolution relative to conventional tablets [

64,

88]. A milk-based oral lyophilisate loaded with the poorly soluble API loratadine also met official quality requirements, underscoring the versatility of lyophilised matrices for paediatric use [

99]. In parallel, nanoparticle-enabled strategies were used to improve bioperformance before tableting: nanoparticles produced by ionic gelation or spray-drying were subsequently compressed into ODTs, including polymer-coated nanoparticles designed for sustained release [

48], prednisolone-loaded nanoparticle tablets for paediatric asthma [

52], and a spray-dried nanoparticle-in-microparticle system in which highly porous particles facilitated rapid disintegration post-compression [

60]. A core–coat approach (nanoparticle core with excipient coat) was also used to achieve immediate and prolonged absorption of meclizine hydrochloride [

92]. These examples illustrate how particle-level engineering can be integrated with conventional compression to tune both disintegration and release.

Another route to rapid breakup involves creating porosity in situ. Sublimation and effervescence were employed before or alongside compression to accelerate disintegration. Volatile pore-formers (e.g., camphor, menthol, thymol, xylitol) were incorporated and then removed by sublimation after compression, yielding permeable matrices with very short disintegration times; camphor-based formulations were particularly effective [

47]. Effervescent systems combining sodium bicarbonate and tartaric acid with disintegrants (e.g., pregelatinised starch, sodium starch glycolate) similarly enhanced matrix breakup and, in some studies, improved release profiles compared with conventional comparators [

66,

87]. Where excipient selection itself was the leverage point, co-processed excipients produced superior palatability relative to a liquisolid approach after compression, suggesting an advantage for taste-critical paediatric formulations [

63]. Complementary to this, a kneaded multi-component system improved the absorption and bioavailability of efavirenz, supporting its value as a paediatric alternative where enhanced exposure is desirable [

82]. Process intensification steps such as top-spray granulation were also used, for example, to prepare mouth-dissolving memantine hydrochloride tablets aimed at rapid onset of action, while remaining compatible with subsequent direct compression [

83].

Finally, personalised paediatric solid dosage forms produced by three-dimensional (3D) printing have gained traction as an adaptable alternative to conventional compression [

108,

109]. A pressure-assisted microsyringe process generated solvent-free, immediate-release tablets by extruding a semi-solid feed in successive layers; disintegration and dissolution were tunable via the number of polymeric layers, and content-uniformity testing confirmed accurate individualised dosing [

81,

110]. A micro-extrusion platform produced orodispersible printlets of hydrochlorothiazide that satisfied European Pharmacopoeia criteria following process optimisation [

91]. Notably, in a comparative study, the moulding approach failed content-uniformity requirements, whereas semi-solid extrusion printlets met all pharmacopoeial tests and offered a credible route for dose individualisation with appropriate quality attributes [

95]. Orodispersible minitablets manufactured via semi-solid extrusion also emerged as promising child-appropriate formats [

105].

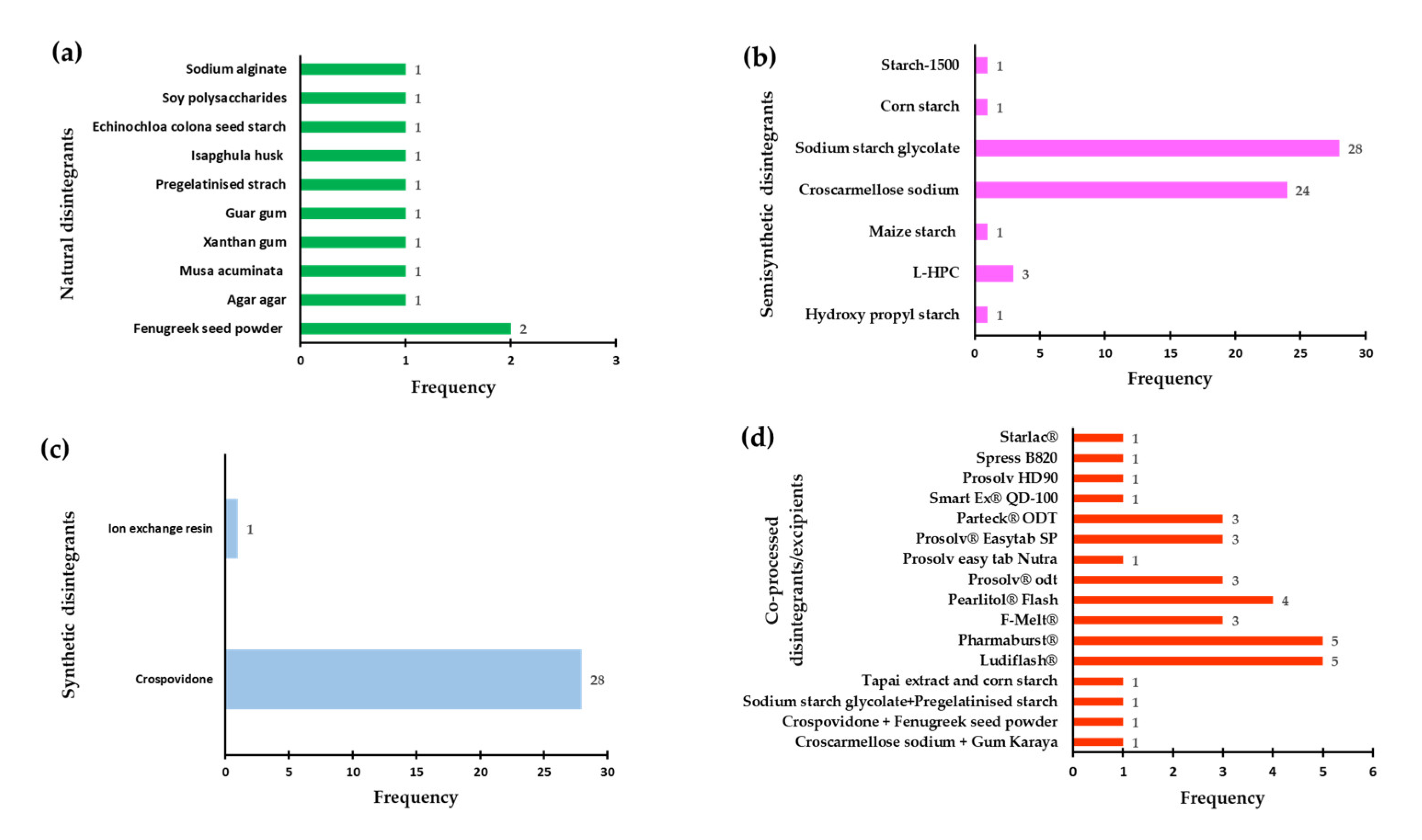

3.2. Use of Disintegrants in ODT Development

Disintegrants are typically incorporated into ODTs at 1–10% w/w to trigger rapid break-up of the compact on wetting, thereby accelerating dissolution and drug release; in the paediatric ODTs surveyed here, materials were classified by origin and principal mode of action into natural, semi-synthetic, synthetic, and co-processed systems (

Figure 7a-d) [

111,

112,

113,

114]. Natural options (

Figure 7a) appeared relatively infrequently in the dataset yet remain of interest for paediatric use because their swelling and gelation behaviours can promote rapid liquid wicking while offering favourable safety and nutritional profiles; their limited frequency of use in the surveyed studies also reflects supply and performance variability that can steer formulators towards more standardised alternatives [

115]. Semi-synthetic superdisintegrants (

Figure 7b) dominated overall usage, with sodium starch glycolate and croscarmellose sodium reported 28 and 24 times, respectively, consistent with their robust swelling and fibrous-wicking mechanisms and reliable performance across active ingredients of differing solubility; L-hydroxypropyl cellulose (L-HPC) was used less often but featured in several dispersible/ODT studies where a balance of rapid dispersion and acceptable mechanical strength was targeted. Among fully synthetic options (

Figure 7c), crospovidone was the most frequently selected superdisintegrant (28 reports), which aligns with its highly cross-linked, capillary-active structure that promotes fast water uptake and tablet rupture with comparatively modest sensitivity to tablet hardness. Beyond single-component superdisintegrants, the literature also evaluated co-processed, ready-to-use excipient systems designed for direct-compression ODTs (

Figure 7d), in which a water-soluble filler is co-formulated with a superdisintegrant and, frequently, a binder, glidant, or lubricant to deliver palatability, rapid disintegration, and acceptable flow and compressibility in one blend.

Figure 7 summarises the relative frequency of each class across the surveyed studies, providing context for the specific choices made in paediatric ODT development.

Compositions for the principal co-processed systems are summarised in

Table 1 [

97,

98]. In particular, Ludiflash

® combines mannitol for mouthfeel with crospovidone for rapid break-up and a polyvinyl acetate component that contributes to tablet integrity; Pharmaburst

® blends crospovidone with mannitol and sorbitol to enhance sweetness and cooling sensation, while precipitated silicon dioxide supports flow; F-Melt

® integrates crospovidone with xylitol, D-mannitol, microcrystalline cellulose, and porous magnesium aluminometasilicate to balance rapid wicking with mechanical strength and blendability; Pearlitol

® Flash pairs corn starch with mannitol for a simple, palatable base; Parteck

® ODT couples mannitol with croscarmellose sodium to exploit swelling–wicking synergy; Prosolv

® Easytab SP unites sodium starch glycolate with microcrystalline cellulose, colloidal silicon dioxide, and sodium stearyl fumarate to streamline flow, compressibility, and lubrication; and Prosolv

® ODT combines crospovidone with microcrystalline cellulose, colloidal silicon dioxide, mannitol, and fructose to deliver rapid disintegration with good mouthfeel (

Table 1) [

116,

117]. Collectively, these co-processed systems can reduce the need for multi-step pre-blending, shorten development time, and improve blend uniformity, yet selection should still be guided by dose and solubility of the API, target disintegration time and mouthfeel, control of hygroscopicity, lubricant sensitivity, and cost of goods. In practice, screening a small matrix of superdisintegrant level and compression force within each selected co-processed base helps confirm robustness, while

Figure 7a–d provide a concise snapshot of how frequently each class, and specific members such as sodium starch glycolate, croscarmellose sodium, and crospovidone, has been deployed across the surveyed ODT formulations.

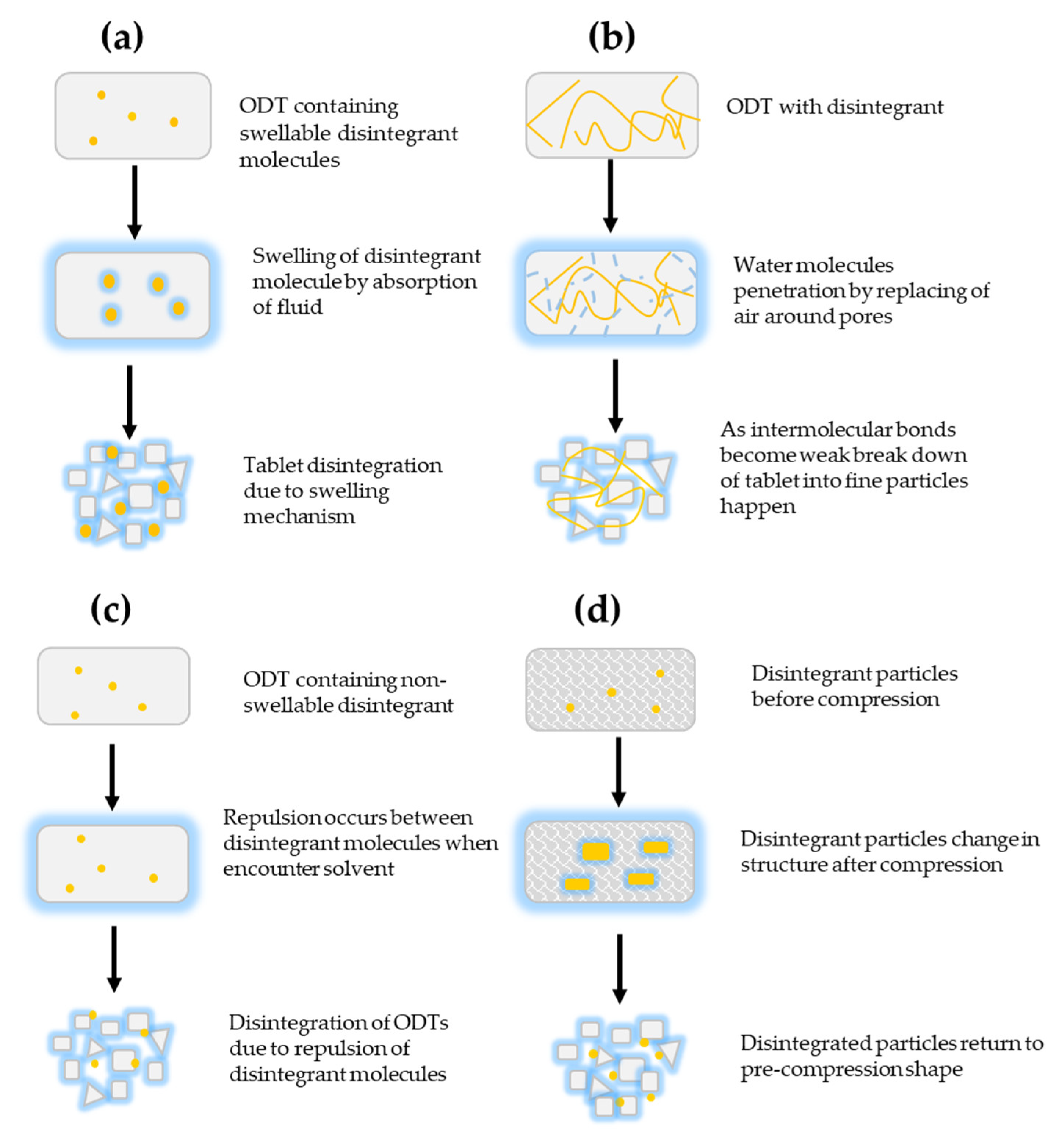

3.2.1. Mechanism of Action of Disintegrants

ODTs disintegrate when the compacted mass takes up liquid and rapidly breaks into smaller fragments that form a homogeneous suspension, thereby enabling prompt drug release. Several complementary mechanisms can operate within the same formulation—swelling, wicking (capillary action), heat of wetting, gas generation (effervescence), enzymatic action, particle–particle repulsion and deformation recovery, with their relative contribution governed by excipient selection, particle size distribution, porosity, compression force, lubricant level, and the hydrophilicity of both drug and excipients [

114,

118,

119].

Table 2 lists the disintegrants identified in this review together with their source and predominant mechanism [

118,

119].

Swelling is the mechanism most commonly associated with both natural and synthetic superdisintegrants. Following initial liquid ingress—often via capillary pathways—water hydrates the disintegrant network distributed throughout the matrix; as the network imbibes liquid, it expands to fill pore volume and generates outward stress that overcomes interparticulate bonds, fracturing the compact into primary granules and then smaller particles, as shown in

Figure 8a [

120,

121]. Achieving rapid, uniform swelling requires sufficient porosity and hydrophilicity to admit water quickly, adequate superdisintegrant level and dispersion to generate internal stress, and compaction conditions that do not collapse pores or over constrain polymer relaxation; excessive compression, hydrophobic lubrication, or high binder levels can retard this pathway [

121]. In wicking, or capillary action, liquid penetrates the tablet through interconnected pores, displacing adsorbed air and weakening interparticulate bonds so that the compact breaks down even when swelling is limited; this capillary-led breakdown is shown in

Figure 8b [

121,

122]. The efficiency of wicking depends strongly on pore architecture, particle surface energy, and the interfacial tension with the penetrating fluid; maintaining a low liquid–solid interfacial tension and an open pore network at the chosen compression force is therefore critical [

121,

123]. Heat of wetting can contribute where certain particles exhibit exothermic wetting. Localised thermal and interfacial changes during rapid wetting may create transient stresses that aid disruption of interparticulate bonds; while seldom the sole driver, this effect can complement wicking and swelling in highly hydrophilic, finely divided excipients [

124]. Gas-generating, or effervescent, systems promote disintegration by producing carbon dioxide within the compact as acids (e.g., citric or tartaric acid) react with carbonates or bicarbonates upon contact with water. The evolving gas increases internal pressure, prising apart the particle network and often improving taste masking and mouthfeel; because these mixtures are sensitive to temperature and humidity, environmental controls during blending, compression, and storage are essential, and the effervescent components are typically incorporated immediately prior to compression [

126]. Enzymatic action represents a biological pathway in which enzymes present in saliva or the gastrointestinal milieu diminish binder integrity or modify polymer structures, thereby facilitating water uptake and matrix rupture. Although not universally relied upon, owing to inter-patient variability, this mechanism can augment physicochemical routes by reducing cohesive strength in the first seconds to minutes of exposure [

127]. Particle–particle repulsion, as described in the Guyot–Hermann framework, posits that electrostatic repulsive forces between wetted particles assist separation once liquid bridges form; while often secondary to wicking, this contribution can be more evident in systems with limited swelling capacity but high surface charge development on wetting, as summarised in

Figure 8c [

127,

128]. Deformation recovery closes the mechanistic set. During tabletting, some disintegrant particles undergo elastic or plastic deformation; once exposed to liquid, these particles relax towards their pre-compression state, increasing in volume and exerting expansion forces that help rupture the compact, as depicted in

Figure 8d. Starch is a classic example: granules deformed under compression display enhanced swelling on rehydration and collectively produce sufficient stress to fracture the tablet [

108].

Overall, effective ODTs rarely rely on a single pathway. Formulations typically harness rapid wicking to admit fluid, prompt swelling or deformation recovery to generate internal stresses, and—where appropriate—adjunct triggers such as effervescence or enzyme-mediated binder weakening. Accordingly, the disintegrants catalogued in Table 3 are best selected not only by their nominal mechanism but also by how they interact with the active ingredient, filler system, and processing conditions to deliver the target disintegration time, palatability, and mechanical robustness [

118,

119].

Figure 8a-d provides a visual summary of how these pathways unfold within the tablet microstructure [

121].

3.3. Disintegration Test and Practical Approaches for Determining Disintegration Time

Within pharmaceutical technology, disintegration time is a critical quality attribute used to confirm that ODTs meet the compendial targets, not more than 3 minutes in the European Pharmacopoeia and about 30 seconds in the United States, so that they disperse promptly in the oral cavity and support rapid drug release [

129,

130,

131]. Because ODTs are intended to disintegrate in the mouth without the need for chewing or water, they are particularly advantageous for paediatric patients who have difficulty swallowing [

132,

133,

134]. In the current systematic search both the USP compendial and modified approaches were employed (

Figure 9).

In general, the compendial approach to measuring ODT disintegration follows the established procedures for solid oral dosage forms (tablets and capsules). In the paediatric ODT literature surveyed here, the pharmacopoeial test used most frequently was the USP method, typically conducted in a 1-litre beaker containing approximately 800–900 mL of distilled water, with time to complete disintegration recorded as per the specifications. Alongside this, several modified or alternative in-vitro methods were also applied to better mimic oral conditions or to accommodate product-specific features. In the petri-plate approach, the tablet is placed carefully at the centre of a petri dish (10 cm internal diameter) containing 10 mL of disintegration medium; the time taken for the tablet to disperse into particles is recorded [

47,

66,

70]. A related variant places a folded tissue or circular filter paper in the petri dish; a dyed disintegration medium is added, the tablet is placed on the wetted paper, and the simulated disintegration time is recorded as the point when the aqueous front has completely diffused across and through the tablet [

78]. A further modification employs a 10-mesh basket suspended in a 1000 mL beaker containing 900 mL of purified water under continuous stirring; the tablet is placed on the basket, and the disintegration time is the moment when no residue remains on the mesh [

70]. To more closely approximate in-mouth environment, Fu et al. [

114] proposed a beaker-and-sieve method, subsequently adapted by other researchers [

72], in which the tablet rests on a sieve suspended 1 cm above the base of a beaker containing 5 mL of artificial saliva; under gentle stirring, particles detach and pass through the sieve, with disintegration time taken at complete dispersion in the medium. In one study, a measuring-cylinder setup was used: 6 mL of phosphate buffer was added to a 25 mL cylinder, the ODT was dropped into the medium, and the time to disintegration was recorded [

79]. The individual procedural requirements, media, and acceptance criteria used in each case are described in

Table S2.

4. Future Directions and Outlook

Over the past decade, paediatric ODT development has shifted from feasibility to platform status, yet several gaps should be addressed to translate laboratory successes into routinely prescribed products. First, harmonisation of disintegration testing remains a priority. Compendial apparatus and endpoints do not fully reflect oral conditions in children; validated, physiologically relevant micro-volume tests (5–10 mL media, artificial saliva of age-appropriate composition, controlled hydrodynamics) should be standardised and cross-validated against USP/Ph. Eur. methods to permit regulatory acceptance while preserving clinical relevance. Closely related is the need for clinically anchored acceptability data: palatability, mouthfeel and swallowability should be reported using age-stratified, validated scales in small, well-designed human studies to complement in-vitro metrics and reduce formulation attrition late in development. Second, excipient strategy warrants broader exploration. Semi-synthetic superdisintegrants (croscarmellose sodium, sodium starch glycolate, crospovidone) dominate current practice, but co-processed systems offer integrated performance with shorter development timelines. Natural polymers remain attractive for cost and sustainability, yet their batch-to-batch variability and microbial limits demand robust characterisation frameworks and supply-chain quality agreements before routine paediatric use. Mapping excipient function to API properties (dose, ionisation state, bitterness, hygroscopicity) using quality-by-design tools and response-surface modelling can shorten optimisation cycles and help predict lubricant sensitivity and compression windows. Third, process intensification and personalisation should move beyond proof-of-concept. Semi-solid extrusion and other 3D-printing routes already meet basic pharmacopeial criteria; the next step is good manufacturing practice (GMP)-ready workflows with in-line mass control, rapid content-uniformity checks, and automated release testing. In parallel, nanoparticle-in-tablet and sublimation/effervescence hybrids deserve head-to-head comparisons with direct compression using shared APIs and unified endpoints, so trade-offs between mechanical strength, disintegration kinetics and taste can be quantified rather than inferred. Finally, equity and access should guide target product profiles. Dose-flexible ODTs for high-burden paediatric indications (e.g., antiepileptics, antibiotics, TB/HIV co-therapies) should emphasise heat-stable packaging, minimal water requirement, and manufacturability using widely available equipment. Transparent reporting, including full datasets for disintegration rig modifications, media recipes and acceptability outcomes, will improve reproducibility and accelerate convergence on best practice. The field is poised to deliver a new generation of child-appropriate ODTs once testing is harmonised, acceptability is measured consistently, and scalable processes are embedded from the outset.

5. Conclusions

This review shows that paediatric ODT development has matured rapidly, with direct compression remaining the workhorse because it is simple, scalable and compatible with taste-masking intermediates. Studies increasingly use pre-compression strategies, coating, complexation, spray-/freeze-drying, nanoparticle engineering, sublimation or effervescence, to reconcile fast disintegration with acceptable mechanical strength and taste. Co-processed excipients and semi-synthetic superdisintegrants dominate successful formulations, while natural options offer promise where cost and sustainability are decisive, provided variability is controlled. Emerging 3D-printing approaches now meet pharmacopeial tests and offer dose individualisation in small units suitable for children. Nonetheless, two barriers limit comparability and translation: heterogeneous disintegration tests that do not consistently reflect the paediatric oral environment, and sparse clinical acceptability data. Addressing these will enable better benchmarking across technologies and faster movement from bench to bedside. In sum, ODTs are well placed to improve paediatric medicine acceptability and adherence; the next phase should focus on harmonised, child-relevant testing and GMP-ready processes to deliver robust products across diverse healthcare settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: BRC, MUG; methodology: SF, BRC, MUG; validation: SF, OH, NA; data curation: SF; writing—original draft preparation: SF, writing—review and editing: SF, BRC, MUG; supervision: BRC, MUG; project administration: MUG. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Samia Farhaj expresses thanks to the University of Huddersfield for awarding her a Fee-Waiver Scholarship to support her doctoral studies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Prateek, S.; Ramdayal, G.; Kumar, S.U.; Ashwani, C.; Ashwini, G.; Mansi, S. Fast dissolving tablets: a new venture in drug delivery. Am. j. PharmTech res. 2012, 2, 252–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovska, V.; Rademaker, C.M.; van Dijk, L.; Mantel-Teeuwisse, A.K.J.P. Pediatric drug formulations: a review of challenges and progress. Pediatrics. 2014, 134, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozarewicz, P. Regulatory perspectives on acceptability testing of dosage forms in children. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 469, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, J.K.W.; Xu, Y.; Worsley, A.; Wong, I.C.K. Oral transmucosal drug delivery for pediatric use. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2014, 73, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner-Hattler, L.; Kiene, K.; Bielicki, J.; Pfister, M.; Puchkov, M.; Huwyler, J. High Acceptability of an Orally Dispersible Tablet Formulation by Children. Children 2021, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajicek, A.; Fossler, M.J.; Barrett, J.S.; Worthington, J.H.; Ternik, R.; Charkoftaki, G.; Lum, S.; Breitkreutz, J.; Baltezor, M.; Macheras, P. A report from the pediatric formulations task force: perspectives on the state of child-friendly oral dosage forms. AAPS J 2013, 15, 1072–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernest, T.B.; Craig, J.; Nunn, A.; Salunke, S.; Tuleu, C.; Breitkreutz, J.; Alex, R.; Hempenstall, J. Preparation of medicines for children – A hierarchy of classification. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 435, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahata, M.C.; Allen, L.V. Extemporaneous drug formulations. Clin. Ther. 2008, 30, 2112–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, B.M.; Capparelli, E.V.; Diep, H.; Rossi, S.S.; Farrell, M.J.; Williams, E.; Lee, G.; van den Anker, J.N.; Rakhmanina, N. Pharmacokinetics of lopinavir/ritonavir crushed versus whole tablets in children. J. Acquired Immune Defic. Syndr. 2011, 58, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF and WHO. Sources and prices of selected medicines for children, 2009 Available online:. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/supply/index_47129.html (accessed on 03).

- Wood, J.; Butler, C.; Hood, K.; Kelly, M.; Verheij, T.; Little, P.; Torres, A.; Blasi, F.; Schaberg, T.; Goossens, H. Antibiotic prescribing for adults with acute cough/LRTI: congruence with guidelines. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, K.; Li, L.; Cui, M.; Han, Y.; Karahan, H.E.; Chow, V.T.K.; Xu, C. Cold Chain-Free Storable Hydrogel for Infant-Friendly Oral Delivery of Amoxicillin for the Treatment of Pneumococcal Pneumonia. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017, 9, 18440–18449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, S.A.; Tuleu, C.; Wong, I.C.; Keady, S.; Pitt, K.G.; Sutcliffe, A.G. Minitablets: new modality to deliver medicines to preschool-aged children. Pediatrics. 2009, 123, e235–e238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.; Bickmann, D.; Breitkreutz, J.; Chariot-Goulet, M. Delivery devices for the administration of paediatric formulations: Overview of current practice, challenges and recent developments. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 415, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, S.; Giacoia, G.; Tuleu, C. The STEP (Safety and Toxicity of Excipients for Paediatrics) database. Part 1—A need assessment study. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 435, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, H.K.; Marriott, J.F. Formulations for children: problems and solutions. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 79, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.; Charoo, N.A.; Abdallah, D.B. Pediatric drug development: formulation considerations. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2014, 40, 1283–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riet-Nales, D.A.; de Neef, B.J.; Schobben, A.F.; Ferreira, J.A.; Egberts, T.C.; Rademaker, C.M. Acceptability of different oral formulations in infants and preschool children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, H.G. WHO guideline development of paediatric medicines: Points to consider in pharmaceutical development. Int. J. Pharm. 2012, 435, 134–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Reflection paper: formulations of choice for the paediatric population (EMEA/CHMP/PEG/194810/2005). Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/formulations-choicepaediatric-

population (Accessed on December 24, 2024). 24 December 2024.

- Almajidi, Y.; Maraie, N. An Overview on Oroslippery Technique as A Promising Alternative for Tablets used in Dysphagia. Research J. Pharm. and Tech. 2019, 12, 4545–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, F.L.; Ernest, T.B.; Tuleu, C.; Gul, M.O. Formulation approaches to pediatric oral drug delivery: benefits and limitations of current platforms. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery. 2015, 12, 1727–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinwala, M. Recent Formulation Advances and Therapeutic Usefulness of Orally Disintegrating Tablets (ODTs). Pharmacy. 2020, 8, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderborn, G. Tablets and compaction. In Aulton’s Pharmaceutics - The design and manufacture of medicines. 3rd ed.; Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh: 2007.

- Belayneh, A.; Molla, F.; Kahsay, G. Formulation and Optimization of Monolithic Fixed-Dose Combination of Metformin HCl and Glibenclamide Orodispersible Tablets. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 2020, 3546597–3546597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, H.; Koner, J.; Huynh, C.; Terry, D.; Mohammed, A.R. Current opinions and recommendations of paediatric healthcare professionals - The importance of tablets: Emerging orally disintegrating versus traditional tablets. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0193292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyami, H.; Koner, J.; Dahmash, E.Z.; Bowen, J.; Terry, D.; Mohammed, A.R. Microparticle surface layering through dry coating: impact of moisture content and process parameters on the properties of orally disintegrating tablets. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 807–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A AlHusban, F.; M El-Shaer, A.; J Jones, R.; R Mohammed, A. Recent patents and trends in orally disintegrating tablets. Recent Pat. Drug Delivery Formulation. 2010, 4, 178–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavkova, M.; Breitkreutz, J. Orodispersible drug formulations for children and elderly. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 75, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavasili, C.; Gkaragkounis, A.; Fatouros, D.G. Patent landscape of pediatric-friendly oral dosage forms and administration devices. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mfoafo, K.A.; Omidian, M.; Bertol, C.D.; Omidi, Y.; Omidian, H. Neonatal and pediatric oral drug delivery: Hopes and hurdles. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 120296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf, M.; Nirwan, J.S.; Smith, A.M.; Timmins, P.; Conway, B.R.; Ghori, M.U. Raft-forming polysaccharides for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD): Systematic review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 48012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.S.; Zaidi, S.T.R.; Nirwan, J.S.; Ghori, M.U.; Javid, F.; Ahmadi, K.; Babar, Z.-U.-D. Use of central nervous system (CNS) medicines in aged care homes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirwan, J.S.; Hasan, S.S.; Babar, Z.-U.-D.; Conway, B.R.; Ghori, M.U. Global Prevalence and Risk Factors of Gastro-oesophageal Reflux Disease (GORD): Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirwan, J.S.; Hasan, S.S.; Conway, B.R.; Ghori, M.U. Investigating the association between education level and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 30 (Suppl. 3), S892–S893. [Google Scholar]

- Nirwan, J.S.; Hasan, S.S.; Conway, B.R.; Ghori, M.U. Investigating the association between diet and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 30 (Suppl. 3), S616–S618. [Google Scholar]

- Nirwan, J.S.; Hasan, S.S.; Conway, B.R.; Ghori, M.U. Investigating the association between body mass index and gastroesophageal reflux disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 30, S592–S593. [Google Scholar]

- Electronic Medicines Compendium, Database on the Internet. Datapharm Communications Ltd. [Internet]. 2021 [cited 20 May 2021]. Available from: http://emc.medicines.org.uk.

- Khizer, Z.; Sadia, A.; Sharma, R.; Farhaj, S.; Nirwan, J.S.; Kakadia, P.G.; Hussain, T.; Yousaf, A.M.; Shahzad, Y.; Conway, B.R. Drug Delivery Approaches for Managing Overactive Bladder (OAB): A Systematic Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2021, 14, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, S.L.; Khan, M.A.; Gupta, A. Development and optimization of taste-masked orally disintegrating tablets (ODTs) of clindamycin hydrochloride. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2015, 41, 1156–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, M.T.; Shoaib, M.H.; Nasiri, M.I.; Yousuf, R.I.; Zaheer, K.; Ahmed, K. Development and evaluation of orally disintegrating tablets of Montelukast sodium by direct compression method. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2015, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimparade, M.B.; Morott, J.T.; Park, J.-B.; Kulkarni, V.I.; Majumdar, S.; Murthy, S.; Lian, Z.; Pinto, E.; Bi, V.; Durig, T. Murthy, R. Development of taste masked caffeine citrate formulations utilizing hot melt extrusion technology and in vitro–in vivo evaluations. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 487, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahtalebi, M.A.; Tabbakhian, M.; Koosha, S. Formulation and evaluation of orally disintegrating tablet of ondansetron using natural superdisintegrant. J. HerbMed Pharmacol. 2015, 4, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, P.K.; Rao, Y.S.; Devi, A.L.; Mallikarjun, P. Formulation and Evaluation of Orally Disintegrating Tablets of Amlodipine Besylate Using Novel Co-Processed Superdisintegrants. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2015, 34, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.; Rao, G.; Mallikarjun, V. Formulation and in- vitro evaluation of fast-disintegrating tablets of flupirtine. Int. J. Pharm. Technol. 2015, 7, 8289–8301. [Google Scholar]

- Samran, K. Methochlopramide orally disintegrating tablet formulation using co-processed excipient of solid tapai extract and corn starch. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2015, 8, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Elwerfalli, A.M.; Al-Kinani, A.; Alany, R.G.; ElShaer, A. Nano-engineering chitosan particles to sustain the release of promethazine from orodispersables. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 131, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labib, G.S. Novel levocetirizine HCl tablets with enhanced palatability: synergistic effect of combining taste modifiers and effervescence technique. Drug Des., Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 5135–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sisi, A.M.; Kharshoum, R.M.; Ali, A.A.; Hosny, K.M.; Abd-Elbary, A. Preparation and Evaluation of Risperidone Oro-dispersible Tablets. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2015, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Subedi, R.; Poudel, K.; Budhathoki, U.; Thapa, P. Taste Masking and Formulation of Ondansetron Hydrochloride Mouth Dissolving Tablets. Int. J. Pharm Sci. Res. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-D.; Liang, Z.-Y.; Cen, Y.-Y.; Zhang, H.; Han, M.-G.; Tian, Y.-Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.-J.; Yang, D.-S. Development of oral dispersible tablets containing prednisolone nanoparticles for the management of pediatric asthma. Drug Des., Dev. Ther. 2015, 9, 5815. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.; Singh, G.; Kumar, D.; Singh, M. Formulation development and evaluation of fast disintegrating tablets of salbutamol sulphate, cetirizine hydrochloride in combined pharmaceutical dosage form: a new era in novel drug delivery for pediatrics and geriatrics. J. Drug Delivery. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.U. Fabrication and evaluation of fast dissolving dosage form of domperidone. Pharm. Lett. 2015, 7, 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Aslani, A.; Beigi, M. Design, formulation, and physicochemical evaluation of montelukast orally disintegrating tablet. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Mishra, D.K.; Jain, D.K. Designing of Fast Disintegrating Tablets for Antihypertensive Agent Using Superdisintegrants. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2016, 9, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, C.K.; Sahoo, N.K.; Sahu, M.; Sarangi, D.K. Formulation and Evaluation of Orodispersible Tablets of Granisetron Hydrochloride Using Agar as Natural Super disintegrants. Pharm. Methods. 2016, 7, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, S.; Aytekin, E.; Yavuz, B.; Bozdağ Pehlivan, S.; Ünlü, N. Formulation studies for mirtazapine orally disintegrating tablets. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2016, 42, 1008–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazly, G.A.; Ibrahim, M.A. Losartan potassium taste-masked oral disintegrating tablets for hypertensive patients. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2016, 35, 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, P.; K Marwaha, R.; Nanda, A.; Dureja, H. Spray-dried nanoparticles-in-microparticles system (NiMS) of acetazolamide using central composite design. Nanosci. Nanotechnol.-Asia. 2016, 6, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwasrao, S.S.; Jadhav, A. Studies on formulation and evaluation of orally disintegrating tablets using Musa acuminata as a natural disintegrant for paediatric use. Indian Drugs. 2016, 53, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipos, E.; Oltean, A.R.; Szabó, Z.-I.; RÉDAI, E.; Nagy, G.D. Application of the SeDeM expert systems in the preformulation studies of pediatric ibuprofen ODT tablets. Acta Pharm. 2017, 67, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moqbel, H.A.; ElMeshad, A.N.; El-Nabarawi, M.A. Comparative study of different approaches for preparation of chlorzoxazone orodispersible tablets. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2017, 43, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, M.; Lai, M.; Estrada, M.; Zhu, C. Developing a Flexible Pediatric Dosage Form for Antiretroviral Therapy: A Fast-Dissolving Tablet. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 2173–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, V.; Yoong, J. Development and evaluation of mouth dissolving tablets using natural super disintegrants. J. Young Pharm. 2017, 9, 332–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Sarfraz, R.M.; Maheen, S.; Mahmood, A.; Shamim, A.; Sher, M. Development and evaluation of novel antihypertensive orodispersible tablets. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 30, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar]

- Tarke, S.; Shanmugasundaram, P. Formulation and evaluation of fast Dissolving tablets of Antihypertensive Drug. Res. J. Pharm. Tech. 2017, 10, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, P.; Kandasamy, R. Development of oral flexible tablet (OFT) formulation for pediatric and geriatric patients: a novel age-appropriate formulation platform. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2017, 18, 1972–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orubu, S.E.; Hobson, N.J.; Basit, A.W.; Tuleu, C. The Milky Way: paediatric milk-based dispersible tablets prepared by direct compression–a proof-of-concept study. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2017, 69, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, P.; Qian, R.; Sun, T.; Fang, F.; Wang, Z.; Ke, X.; Xu, B. A novel and discriminative method of in vitro disintegration time for preparation and optimization of taste-masked orally disintegrating tablets of carbinoxamine maleate. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2018, 44, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, S.; Aytekin, E.; Yavuz, B.; Bozdağ Pehlivan, S.; Vural, İ.; Ünlü, N. Development and evaluation of orally disintegrating tablets comprising taste-masked mirtazapine granules. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2018, 23, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennini, N.; Orlandini, S.; Furlanetto, S.; Pasquini, B.; Mura, P. Development and Optimization by Quality by Design Strategies of Frovatriptan Orally Disintegrating Tablets for Migraine Management. Curr. Drug Delivery. 2018, 15, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemiradzka, W.; Szulc-Musiol, B.; Bulas, L.; Jankowski, A. Effect of selected excipients and the preparation method on the parameters of orally disintegrating tablets containing ondansetron. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2018, 75, 733–740. [Google Scholar]

- G, S.; Pg, M.; K, C.; M, L.; S, A. Formulation and evaluation of fast dissolving tablet of ketorolac tromethamine. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkmen, Ö.; Şenyiğit, Z.A.; Baloğlu, E. Formulation and evaluation of fexofenadine hydrochloride orally disintegrating tablets for pediatric use. J. Drug Deliv Sci.Technol. 2018, 43, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husseiny, R.A.; Abu Lila, A.S.; Abdallah, M.H.; El-ghamry, H.A. Fast disintegrating tablet of Valsartan for the treatment of pediatric hypertension: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Drug Deliv Sci.Technol. 2018, 43, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.M.; Gupta, I.K.; Baboota, S.; Gupta, M. Formulation Development and Evaluation of Orally Disintegrating Tablet of Taste Masked Azithromycin. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2019, 38, 1478–1484. [Google Scholar]

- Kabir, Q.A.; Wasti, A.N.; Nazir, S.U.; Adnan, M.; Azhar, R.F.; Bukhari, F.; Amer, M. Formulation Development and In Vitro Evaluation of Mouth Dissolving Tablets of Domperidone. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2019, 38, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar]

- Jaya, S.; Amala, V. Formulation and in vitro evaluation of oral disintegrating tablets of amlodipine besylate. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2019, 11, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopalco, A.; Curci, A.; Lopedota, A.; Cutrignelli, A.; Laquintana, V.; Franco, M.; Denora, N. Pharmaceutical preformulation studies and paediatric oral formulations of sodium dichloroacetate. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 127, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aita, I.; Rahman, J.; Breitkreutz, J.; Quodbach, J. 3D-Printing with precise layer-wise dose adjustments for paediatric use via pressure-assisted microsyringe printing. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 157, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas Neto, J.L.; do Nascimento Gomes Barbosa, I.; de Melo, C.G.; Ângelos, M.A.; dos Santos Mendes, L.M.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; Rolim, L.A.; Soares, L.A.; da Silva, R.M.F.; Neto, P.J.R. Development of Pediatric Orodispersible Tablets Based on Efavirenz as a New Therapeutic Alternative. Curr. HIV Res. 2020, 18, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghogari, I.S.; Jain, P.S. Development of orally disintegrating tablets of memantine hydrochloride—A remedy for Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2020, 12, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, T.J.; Smith, J.C.; Badhan, R.K.; Mohammed, A.R. Formulation and Bioequivalence Testing of Fixed-Dose Combination Orally Disintegrating Tablets for the Treatment of Tuberculosis in the Paediatric Population. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 109, 3105–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamivelmanickam, M.; Venkatesan, P.; Sangeetha, G. Preparation and Evaluation of Mouth Dissolving Tablets of Loratadine by Direct Compression Method. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2020, 13, 2629–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panhale, D.P.; Bachhav, R.S.; Gondkar, S.B. Formulation and evaluation of orodispersible tablets of apremilast by inclusion complexation using beta-cyclodextrin. Ind. J. Pharm. Edu. Res 2021, 55, S112–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Verma, R.; Kaushik, R.; Kaushik, P.; Pandey, P.; Purohit, D.; Mittal, V.; Kaushik, D. Optimization and In vitro Evaluation of Famotidine Loaded Effervescent Orally Disintegrating Tablets Using Central Composite Design. Curr. Drug Ther. 2021, 16, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami-Milani, M.; Salatin, S.; Nasiri, E.; Jelvehgari, M. Preparation and optimization of fast disintegrating tablets of isosorbide dinitrate using lyophilization method for oral drug delivery. Ther. Delivery 2021, 12, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamling, S.S.; Chavan, S.; Chandrakant, G.P.; Kharat, R.T.; Kulkarni, A.S. Isolation, Characterization, Chemical Modification and Application of Echinochloa Colona Starch as Tablet Disintegrant. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Nanotechnol. 2021, 14, 5529–5537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, P.; Raman, S. Formulation and evaluation of fast dissolving tablet of prasugrel. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2021, 14, 4077–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduardo, D.-T.; Ana, S.-E. A micro-extrusion 3D printing platform for fabrication of orodispersible printlets for pediatric use. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 605, 120854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwesh, A.Y.; El-Dahhan, M.S.; Meshali, M.M. A new dual function orodissolvable/dispersible meclizine HCL tablet to challenge patient inconvenience: in vitro evaluation and in vivo assessment in human volunteers. Drug Delivery Transl. Res. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokott, M.; Lura, A.; Breitkreutz, J.; Wiedey, R. Evaluation of two novel co-processed excipients for direct compression of orodispersible tablets and mini-tablets. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 168, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhal, P.; Chamola, P.; Kumar, V.J.; Kumar, S.; Rout, A. Optimized fast disintegrating tablets, boosted oseltamivir phosphate orally fast disintegrating tablets. J. Med. Pharm. Allied Sci. 2021, 10, 3781–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-González, J.; Magariños-Triviño, M.; Díaz-Torres, E.; Cáceres-Pérez, A.R.; Santoveña-Estévez, A.; Fariña, J.B. Individualized orodispersible pediatric dosage forms obtained by molding and semi-solid extrusion by 3D printing: A comparative study for hydrochlorothiazide. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2021, 66, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, N.H.S.; Ming, L.C.; Uddin, A.H.; Sarker, Z.I.; Bin, L.K. Investigation of the Effects of Excipients in the Compounding of Amlodipine Besylate Orally Disintegrating Tablets. Int. J. Pharm. Compd. 2022, 26, 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Thakker, P.; Shah, J.; Mehta, T.; Shetty, V.; Aware, R.; Kuchekar, A. Development and evaluation of taste masked orally disintegrating tablets of pioglitazone hydrochloride. J. Res. Pharm. 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adsare, V.; Prakash, L.R.; Gholap, P.; Kanthale, S.B.; Choudante, S. To enhance the solubility of ivermectin with physical mixing method for the preparation of orodispersible tablets. J. Pharm. Negat. Results 2022, 964–971. [Google Scholar]

- Iurian, S.; Bogdan, C.; Suciu, Ș.; Muntean, D.-M.; Rus, L.; Berindeie, M.; Bodi, S.; Ambrus, R.; Tomuță, I. Milk Oral Lyophilizates with Loratadine: Screening for New Excipients for Pediatric Use. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlad, R.-A.; Antonoaea, P.; Todoran, N.; Rédai, E.-M.; Bîrsan, M.; Muntean, D.-L.; Imre, S.; Hancu, G.; Farczádi, L.; Ciurba, A. Development and Evaluation of Cannabidiol Orodispersible Tablets Using a 23-Factorial Design. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhetre, R.L.; Kadam, P.S.; Gadhire, P.H.; Lajurkar, G.; Kagde, A.D.; Dhole, S.N. Formulation and Evaluation of Naproxen Orodispersible Tablets. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Nanotechnol 2022, 15, 6055–6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadell-Heredia, R.; Suñé-Pou, M.; Nardi-Ricart, A.; Pérez-Lozano, P.; Suñé-Negre, J.; García-Montoya, E. Formulation and development of paediatric orally disintegrating carbamazepine tablets. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 1612–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, A.; Yousuf, R.I.; Shoaib, M.H.; Qazi, F.; Saleem, M.T.; Siddiqui, F.; Ahmed, F.R.; Jabeen, S.; Farooqi, S.; Khan, M.Z. Effect of starch, cellulose and povidone based superdisintegrants in a QbD-based approach for the development and optimization of Nitazoxanide orodispersible tablets: Physicochemical characterization, compaction behavior and in-silico PBPK modeling of its active metabolite Tizoxanide. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2023, 79, 104079. [Google Scholar]

- Teaima, M.H.; El-Messiry, H.M.A.; Osman, T.D.; El-Nabarawi, M.A.; Helal, D.A. The effect of co-processed excipients during formulation and evaluation of pediatric levetiracetam orodispersible tablets in rats. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2023, 15, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Fitaihi, R.; Abukhamees, S.; Abdelhakim, H.E. Formulation and Characterisation of Carbamazepine Orodispersible 3D-Printed Mini-Tablets for Paediatric Use. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghori, M.U.; Conway, B.R. Powder compaction: Compression properties of cellulose ethers. Br. J. Pharm. 2016, 1, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, N.; Deshpande, K. Orodispersible tablets: an overview of formulation and technology. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 2011, 2, 726–734. [Google Scholar]

- Okwuosa, T.C.; Soares, C.; Gollwitzer, V.; Habashy, R.; Timmins, P.; Alhnan, M.A. On demand manufacturing of patient-specific liquid capsules via co-ordinated 3D printing and liquid dispensing. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 118, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fina, F.; Madla, C.M.; Goyanes, A.; Zhang, J.; Gaisford, S.; Basit, A.W. Fabricating 3D printed orally disintegrating printlets using selective laser sintering. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 541, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, V.M.; Kumar, L. 3D Printing as a Promising Tool in Personalized Medicine. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.M.; Liew, C.V.; Heng, P.W.S. Review of Disintegrants and the Disintegration Phenomena. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 2545–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markl, D.; Zeitler, J.A. A review of disintegration mechanisms and measurement techniques. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 890–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulton, M.E.; Summers, M. Tablets and compaction. Pharmaceutics The Science of Dosage Form Design, 4th. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone 2013, pp. 397-439.

- Kumar, R.S.; Kumari, A. Superdisintegrant: crucial elements for mouth dissolving tablets. J. drug delivery ther. 2019, 9, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.T.; Parvez, N.; Sharma, P.K. FDA-Approved Natural Polymers for Fast Dissolving Tablets. J. Pharm. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoltenberg, I.; Breitkreutz, J. Orally disintegrating mini-tablets (ODMTs) – A novel solid oral dosage form for paediatric use. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2011, 78, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkmen, Ö.; Ay Şenyiğit, Z.; Baloğlu, E. Formulation and evaluation of fexofenadine hydrochloride orally disintegrating tablets for pediatric use. J. Drug Delivery Sci. Technol. 2018, 43, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahwa, R.; Gupta, N. Superdisintegrants in the development of orally disintegrating tablets: a review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2011, 2, 2767–2780. [Google Scholar]

- Shihora, H.; Panda, S. Superdisintegrants, utility in dosage forms: a quick review. J Pharm Sci Biosci Res. 2011, 1, 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, A.; Bisharat, L.; Blaibleh, A.; Pavoni, L.; Cespi, M. A simple and inexpensive image analysis technique to study the effect of disintegrants concentration and diluents type on disintegration. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 107, 2643–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Md, N.A.; Sharma, S.K.; Jaimini, M.; Mohan, S.; Chatterjee, A. Fast dissolving dosage forms: Boon to emergency conditions. Int. J. Ther. Appl. 2014, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Garg, S. Fast dissolving tablets (FDTs): Current status, new market opportunities, recent advances in manufacturing technologies and future prospects. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, P.M.; Er, P.X.H.; Liew, C.V.; Heng, P.W.S. Functionality of disintegrants and their mixtures in enabling fast disintegration of tablets by a quality by design approach. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2014, 15, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rewar, S.; Singh, C.; Bansal, B.; Pareek, R.; Sharma, A. Oral dispersible tablets: An overview; development, technologies and evaluation. Int. J. Res. Dev. Pharm. Life. Sci. 2014, 3, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N.; Pahuja, S.; Sharma, N. Immediate release tablets: a review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2019, 10, 3607–3618. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, V.; Mehara, N. A Review on: Importance of Superdisintegrants on Immediate Release Tablets. International Journal of Research and Scientific Innovation 2016, 3, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chotaliya, M.K.B.; Chakraborty, S. Overview of oral dispersible tablets. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2012, 4, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, R.C.; Sheskey, P.; Quinn, M. Handbook of pharmaceutical excipients; Libros Digitales-Pharmaceutical Press: 2009.

- Wasilewska, K.; Winnicka, K. How to assess orodispersible film quality? A review of applied methods and their modifications. Acta Pharm. 2019, 69, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Redfearn, A.; MacLeod, G.; Tuleu, C.; Hanson, B.; Orlu, M. How Do Orodispersible Tablets Behave in an In Vitro Oral Cavity Model: A Pilot Study. Pharmaceutics. 2020, 12, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koner, J.S.; Rajabi-Siahboomi, A.R.; Missaghi, S.; Kirby, D.; Perrie, Y.; Ahmed, J.; Mohammed, A.R. Conceptualisation, Development, Fabrication and In Vivo Validation of a Novel Disintegration Tester for Orally Disintegrating Tablets. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, P.; Lasher, J.; Alexander, K.S.; Baki, G. A new modified wetting test and an alternative disintegration test for orally disintegrating tablets. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 120, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Jeong, S.H.; Callihan, J.; Kim, J.; Park, K. Preparation of fast-dissolving tablets based on mannose. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 340–351. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Kataria, P.; Nakhat, P.; Yeole, P. Taste masking of ondansetron hydrochloride by polymer carrier system and formulation of rapid-disintegrating tablets. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2007, 8, E127–E133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).