Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

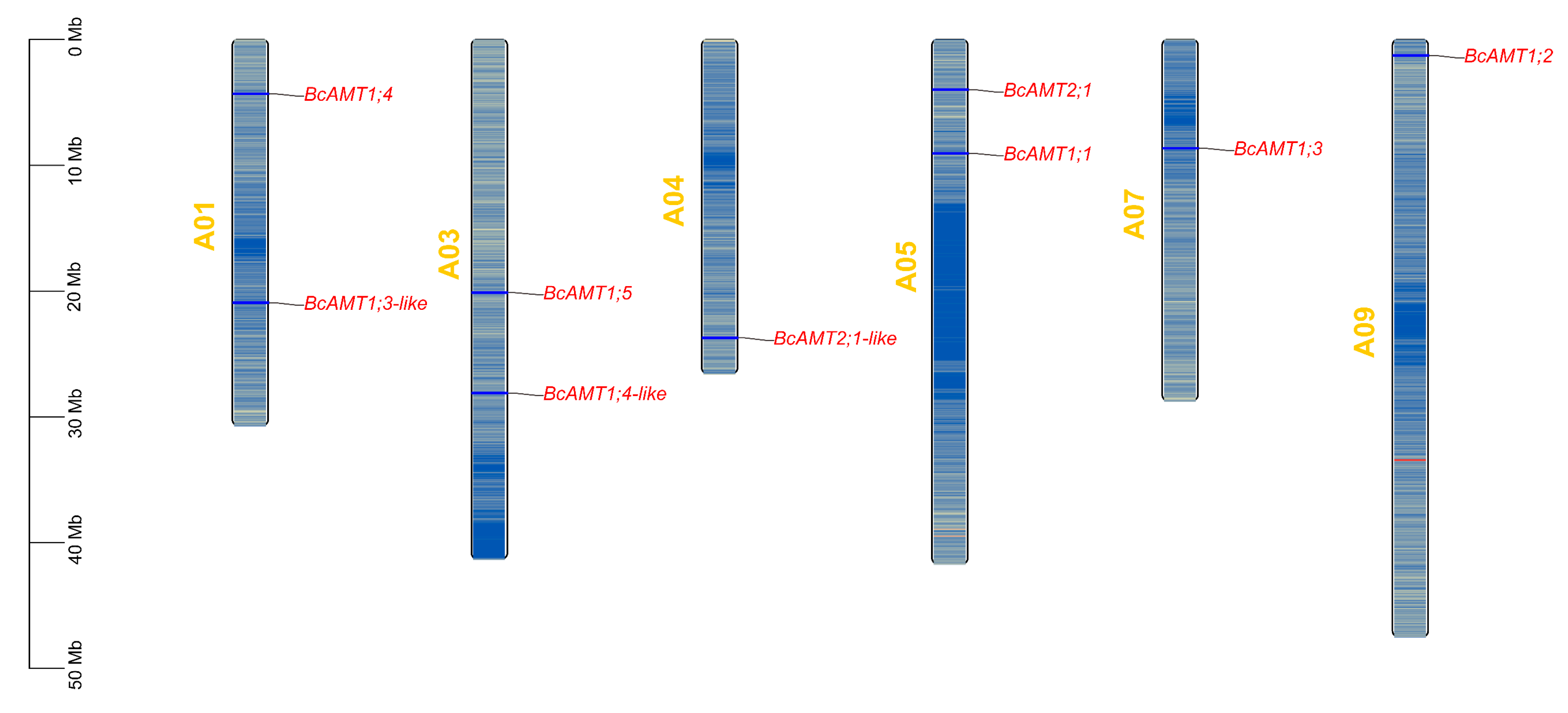

2.1. Identification and Chromosomal Localization of BcAMT Gene Family in Flowering Chinese Cabbage

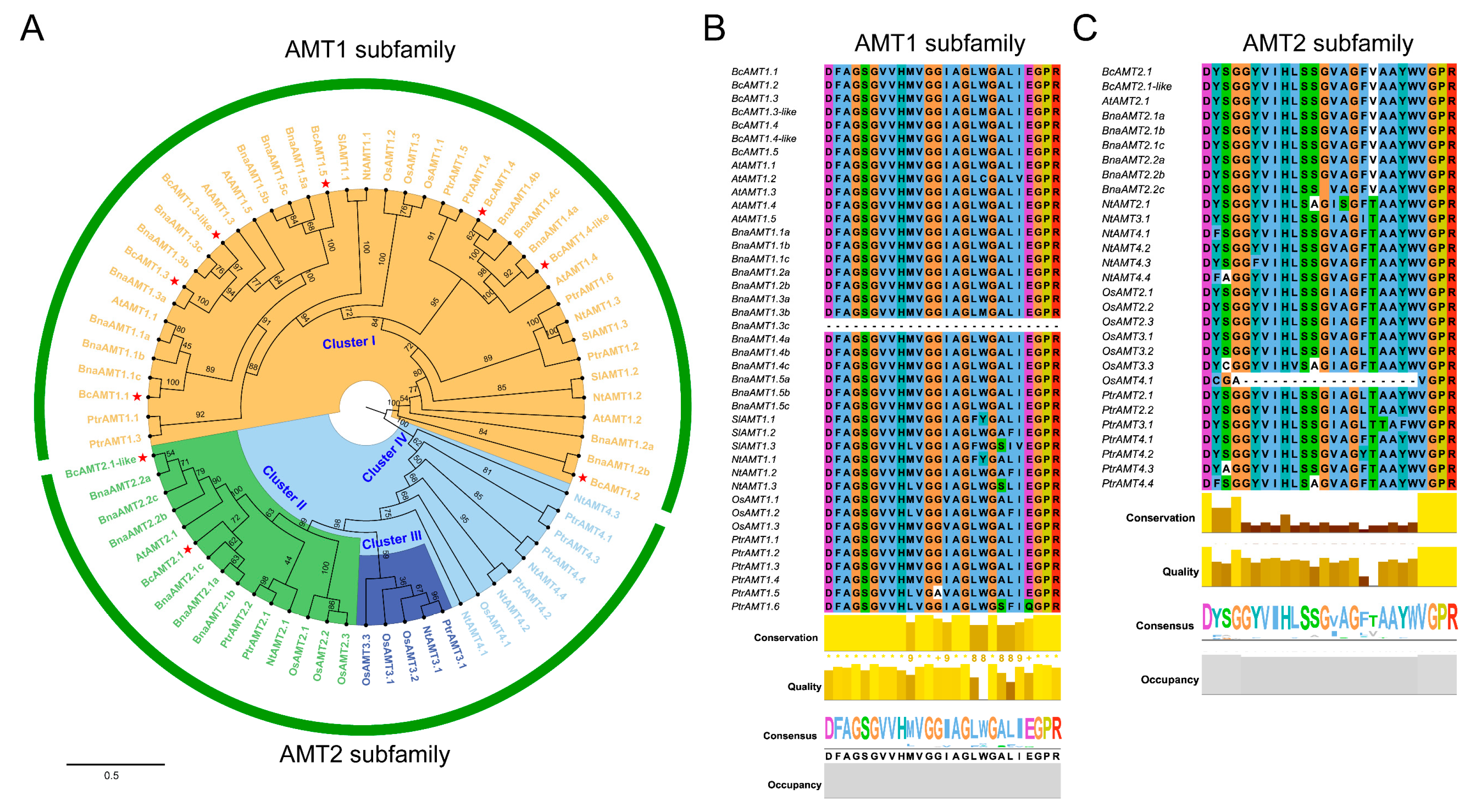

2.2. Phylogenetic Tree and Conserved Domains Analyses of BcAMT Gene Family

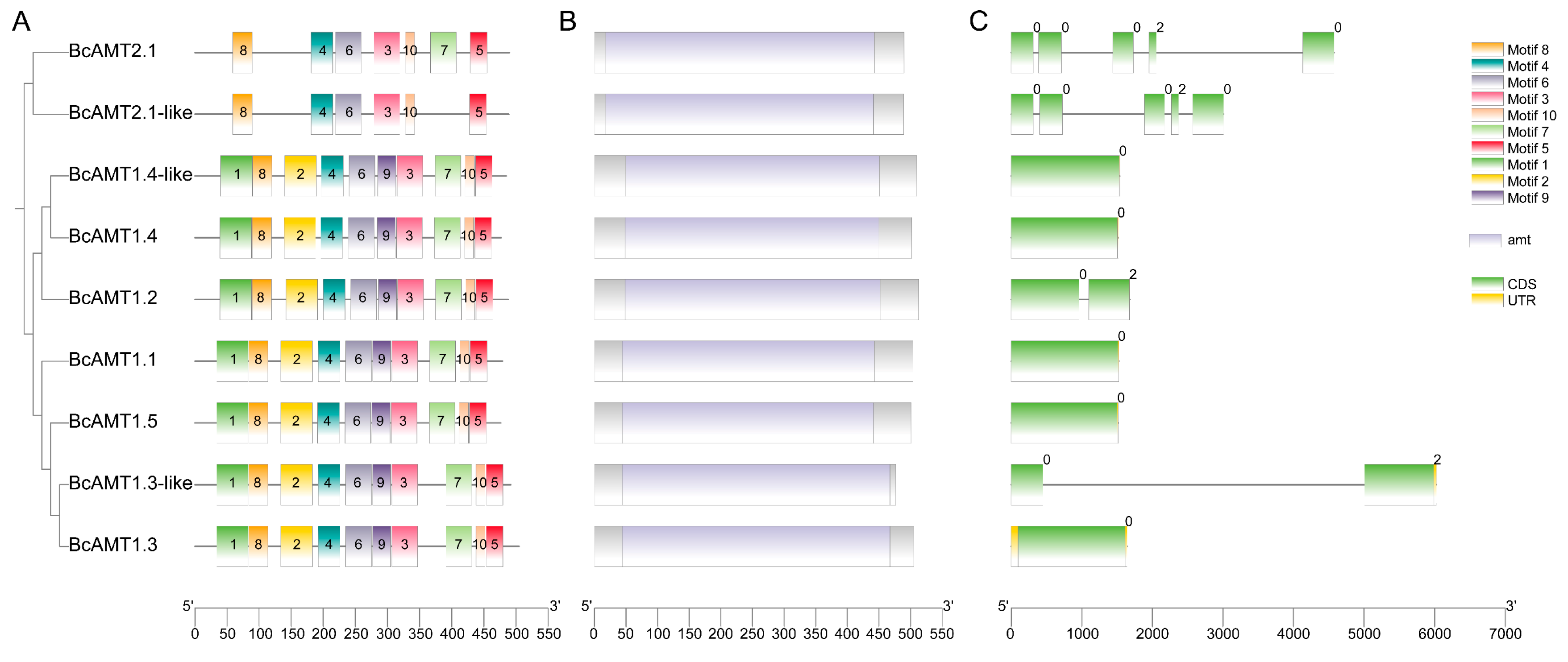

2.3. Conserved Motifs and Gene Structure of BcAMT Gene Family

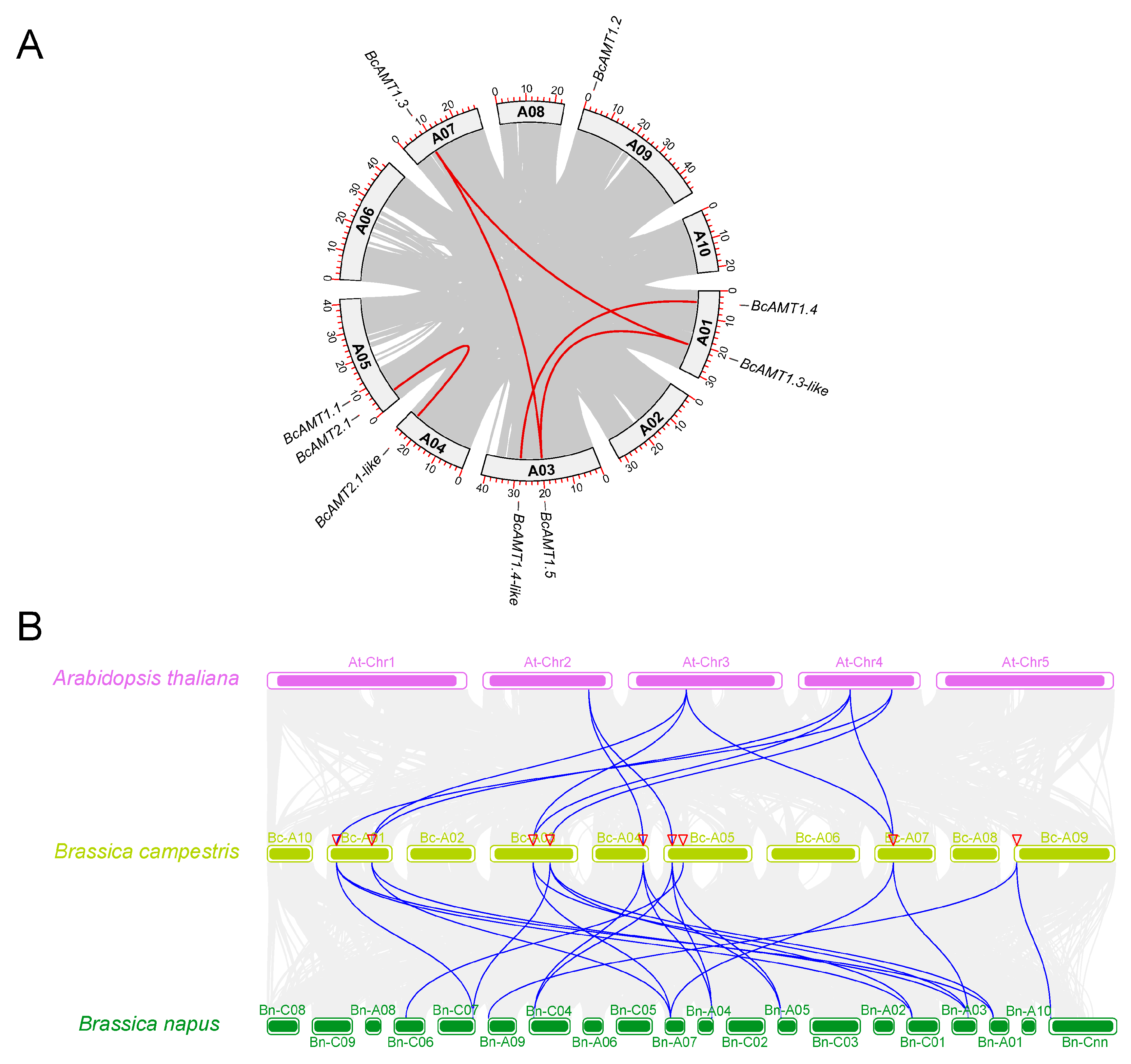

2.4. Gene Duplication and Synteny Analyses of the BcAMT Gene Family

2.5. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in BcAMT Promoter Regions

2.6. Expression Patterns of BcAMTs Across Tissues of Flowering Chinese Cabbage and Under Different Nitrogen Forms

2.6.1. Tissue-Specific Expression

2.6.2. BcAMTs Response to Nitrogen Forms

2.6.3. Response to Nitrogen Deficiency and Different NH4+ Concentration

2.7. Subcellular Localization and NH4+ Transport Activity of BcAMT1.1

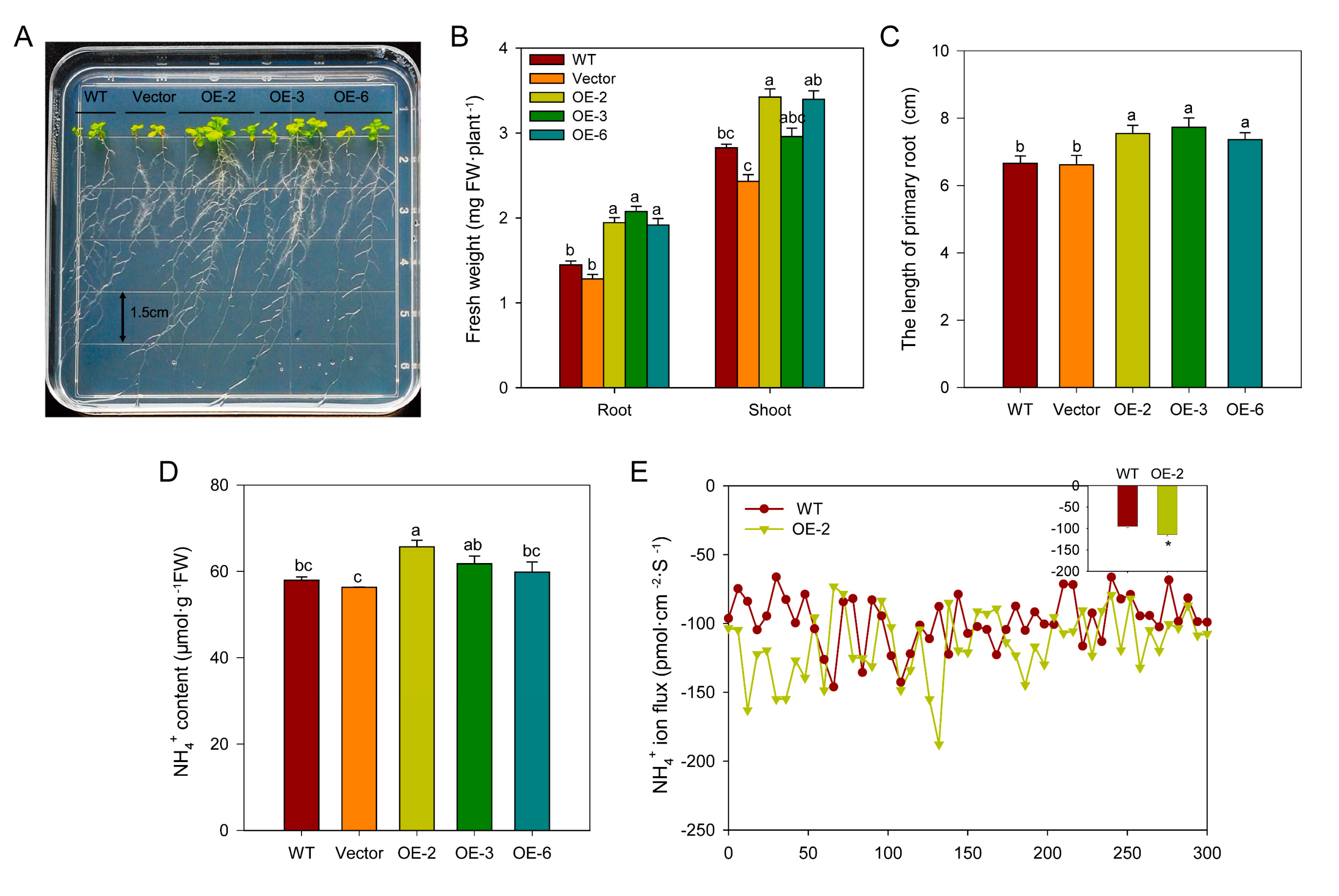

2.8. Overexpressing BcAMT1.1 Promotes NH4+ Uptake and Accelerates Plant Growth of Arabidopsis Under Low NH4+ Concentration

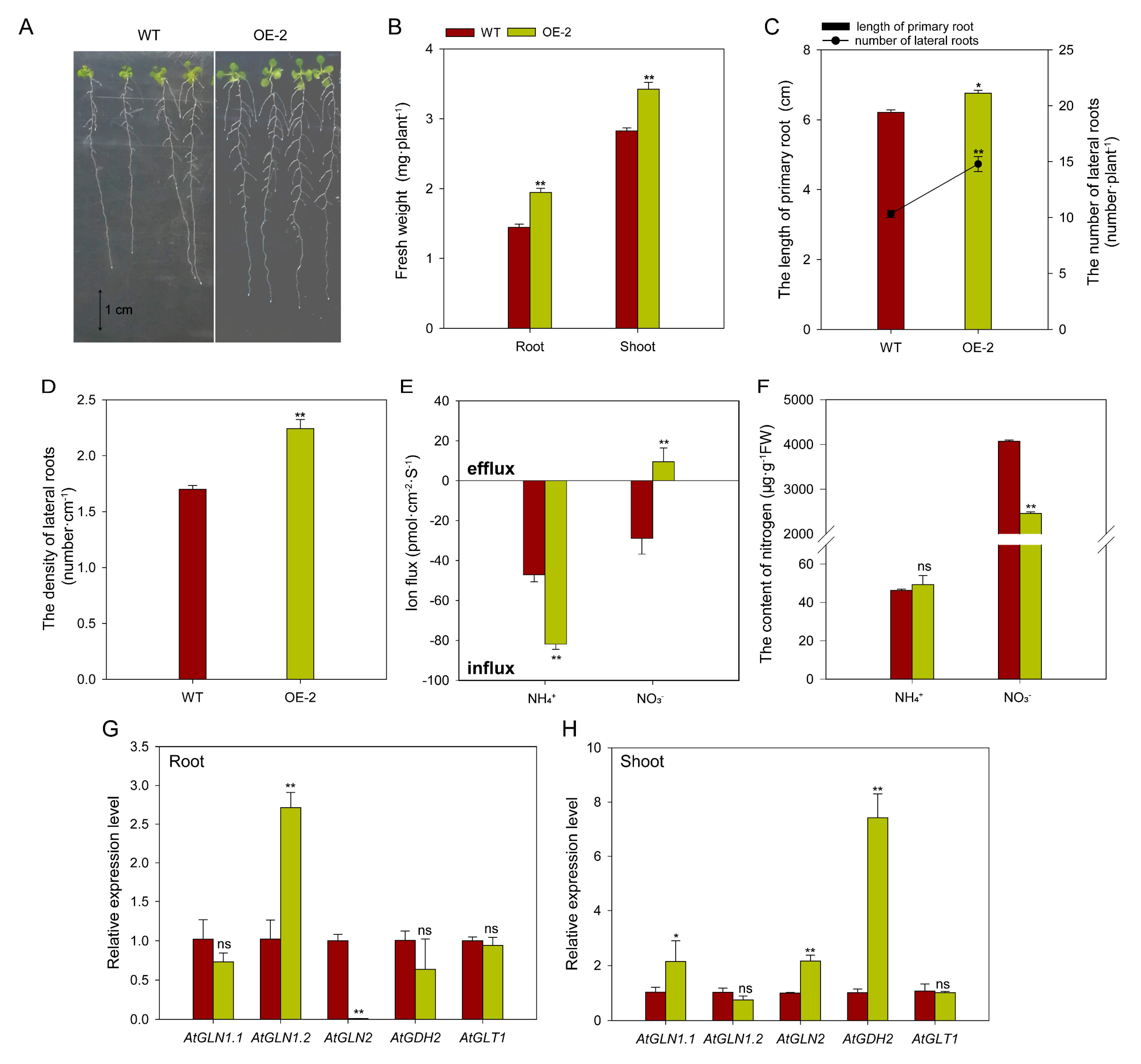

2.9. Overexpressing BcAMT1.1 Alters Nitrogen Ion Fluxes and the Expression of Nitrogen Assimilation-Related Genes in Arabidopsis

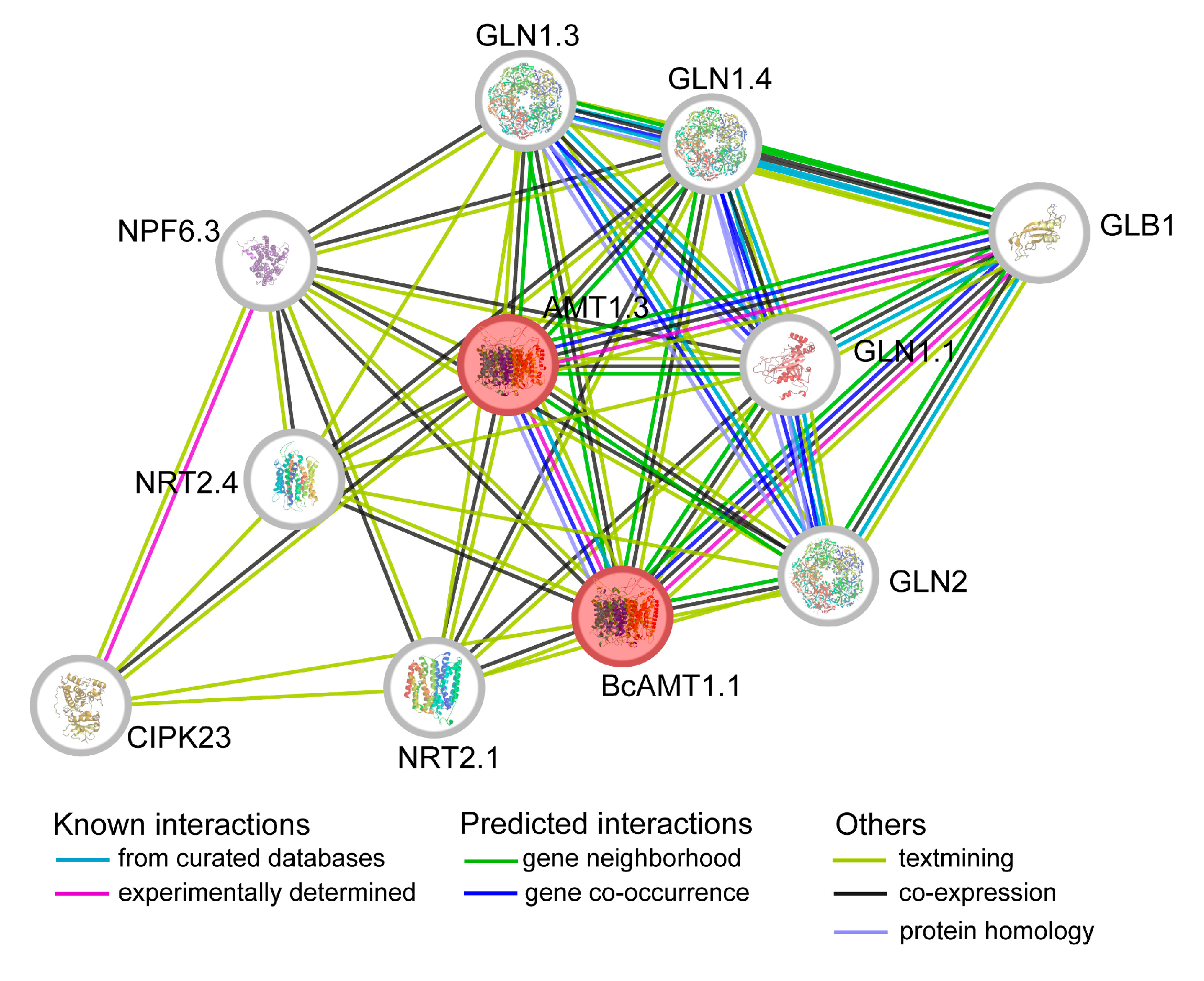

2.10. Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network of BcAMT1.1

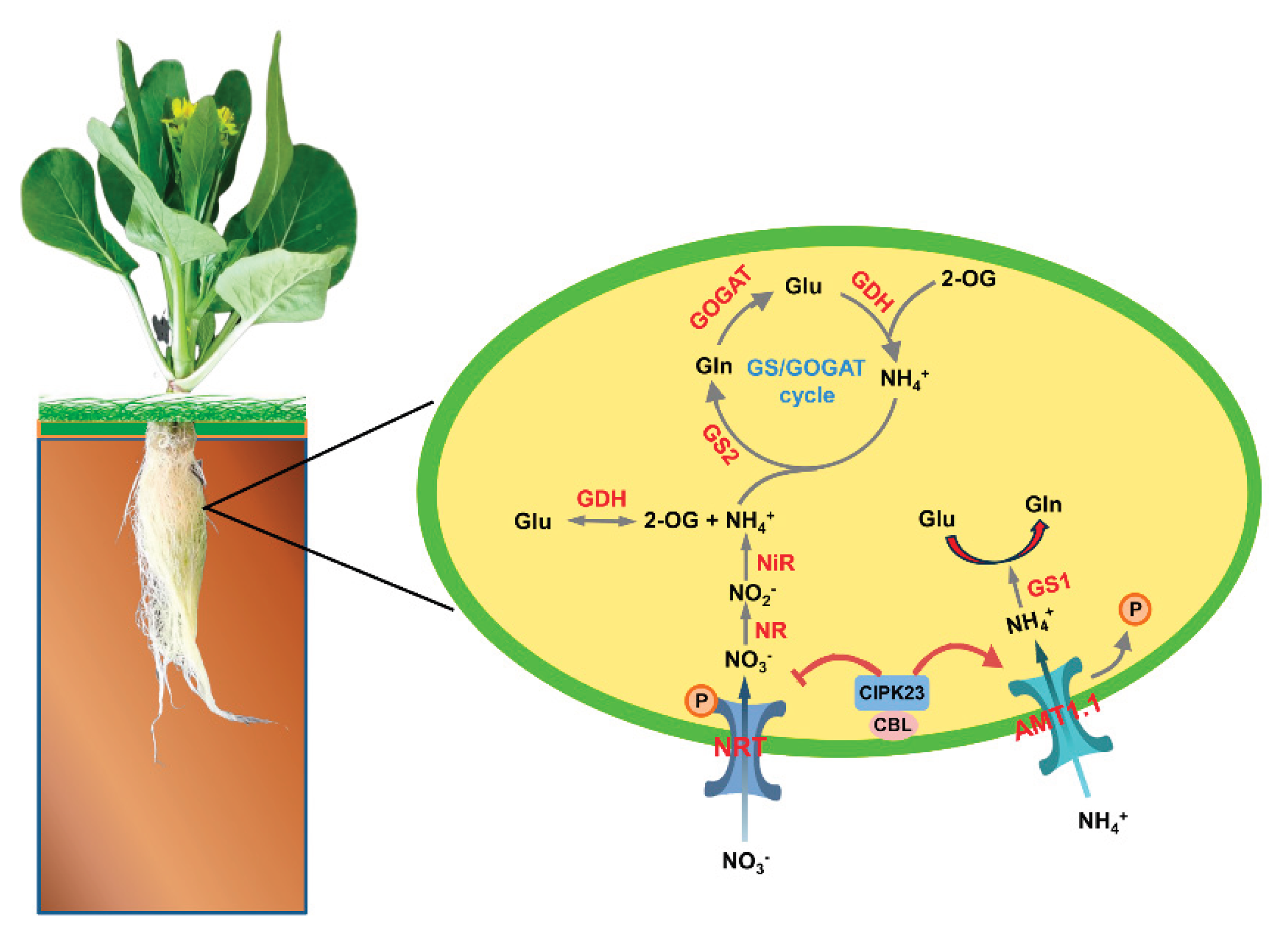

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Geonmoe-Wide Identification of AMT Genes in Flowering Chinese Cabbage and Chromosome Location

4.2. Phylogenetic Tree, Conserved Motifs, Domains, and Gene Structure Analyses of AMT Members

4.3. Gene Duplication and Geneome-Wide Synteny Analysis of AMTs

4.4. Identification of Cis-Acting Elements in AMT Promoter Regions

4.5. Expression Profiling of BcAMTs

4.6. Subcellular Localization of BcAMT1.1

4.7. Functional Complementation Analysis of BcAMT1.1 in Yeast

4.8. Overexpression of BcAMT1.1 in Arabidopsis

4.9. Prediction of Protein-Protein Interaction Network of BcAMT1.1

4.10. Statistial Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kindred, D.R.; Verhoeven, T.M.O.; Weightman, R.M.; Swanston, J.S.; Agu, R.C.; Brosnan, J.M.; Sylvester-Bradley, R. Effects of variety and fertiliser nitrogen on alcohol yield, grain yield, starch and protein content, and protein composition of winter wheat. J. Cereal. Sci. 2008, 48, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tei, F.; De Neve, S.; de Haan, J.; Kristensen, H.L. Nitrogen management of vegetable crops. Agr. Water Manag. 2020, 240, 106316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, H. Optimizing the nitrogen use efficiency in vegetable crops. Nitrogen 2024, 5, 106–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Fan, X.; Miller, A.J. Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 153–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechorgnat, J.; Nguyen, C.T.; Armengaud, P.; Jossier, M.; Diatloff, E.; Filleur, S.; Daniel-Vedele, F. From the soil to the seeds: the long journey of nitrate in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yan, L.; Zhang, W.; Yi, C.; Haider, S.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Shi, L.; Ding, G. Nitrate alleviates ammonium toxicity in Brassica napus by coordinating rhizosphere and cell pH and ammonium assimilation. Plant J. 2024, 117, 786–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, A.J.; Burger, M.; Asensio, J.S.R.; Cousins, A.B. Carbon dioxide enrichment inhibits nitrate assimilation in wheat and Arabidopsis. Science 2010, 328, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hu, B.; Chu, C. Nitrogen assimilation in plants: current status and future prospects. J. Genet. Genomics. 2022, 49, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omari Alzahrani, F. Ammonium transporter 1 (AMT1) gene family in pomegranate: genome-wide analysis and expression profiles in response to salt stress. Curr. Issues. Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, J.; Montanini, B.; Martin, F.; Brun, A.; Blaudez, D.; Chalot, M. The expanded family of ammonium transporters in the perennial poplar plant. New. Phytol. 2007, 174, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.; Harris, T.; Bizior, A.; Hoskisson, P.A.; Pritchard, L.; Javelle, A. Biological ammonium transporters: evolution and diversification. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 3786–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, A.D.M.; Britto, D.T.; Kaiser, B.N.; Kinghorn, J.R.; Kronzucker, H.J.; Kumar, A.; Okamoto, M.; Rawat, S.; Siddiqi, M.Y.; Unkles, S.E.; Vidmar, J.J. The regulation of nitrate and ammonium transport systems in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, T.R.; Ward, J.M. Evolution of electrogenic ammonium transporters (AMTs). Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludewig, U.; Neuhäuser, B.; Dynowski, M. Molecular mechanisms of ammonium transport and accumulation in plants. Febs. Lett. 2007, 581, 2301–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohlenkamp, C.; Shelden, M.; Howitt, S.; Udvardi, M. Characterization of Arabidopsis AtAMT2, a novel ammonium transporter in plants. Febs. Lett. 2000, 467, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninnemann, O.; Jauniaux, J.C.; Frommer, W.B. Identification of a high affinity NH4+ transporter from plants. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 3464–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Merrick, M.; Li, S.; Li, H.; Zhu, S.; Shi, W.; Su, Y. Molecular basis and regulation of ammonium transporter in rice. Rice Sci. 2009, 16, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, N.; Ma, J.F. Three polarly localized ammonium transporter 1 members are cooperatively responsible for ammonium uptake in rice under low ammonium condition. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 1778–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Han, P.; Walk, T.C.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Gu, C.; Liao, X.; Qin, L. Genome-wide identification and characterization of ammonium transporter (AMT) genes in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Genes 2023, 14, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Dong, X.; Yuan, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the ammonium transporter family genes in soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Fan, T.; Shi, D.; Li, C.; He, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, C.; Cheng, X.; Chen, X.; Li, D.; Sun, Y. Coding-sequence identification and transcriptional profiling of nine AMTs and four NRTs from tobacco revealed their differential regulation by developmental stages, nitrogen nutrition, and photoperiod. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Loqué, D.; Kojima, S.; Rauch, S.; Ishiyama, K.; Inoue, E.; Takahashi, H.; von Wirén, N. The organization of high-affinity ammonium uptake in Arabidopsis roots depends on the spatial arrangement and biochemical properties of AMT1-type transporters. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2636–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohlenkamp, C.; Wood, C.C.; Roeb, G.W.; Udvardi, M.K. Characterization of Arabidopsis AtAMT2, a high-affinity ammonium transporter of the plasma membrane. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 1788–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Graff, L.; Loqué, D.; Kojima, S.; Tsuchiya, Y.N.; Takahashi, H.; von Wirén, N. AtAMT1;4, a Pollen-specific high-affinity ammonium transporter of the plasma membrane in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009, 50, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tang, Z.; Wei, J.; et al. The OsAMT1.1 gene functions in ammonium uptake and ammonium-potassium homeostasis over low and high ammonium concentration ranges. J. Genet. Genomics 2016, 43, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, G.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, M.; Chen, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, Y.; Liao, Y.; Chen, C. Genomic selection and genetic architecture of agronomic traits during modern flowering Chinese cabbage breeding. Hortic Res. 2025, 12, uhae299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; He, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, R.; Zhu, Y.; Song, S.; He, Q. Genome-wide identification of SWEET gene family and functional analysis of BcSWEET1-2 associated with flowering in flowering Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris). BMC Genomics 2025, 26, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Anwar, A.; He, B.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.; Hao, Y.; Chen, R.; Song, S. Genome-wide identification of BcGRF genes in flowering Chinese cabbage and preliminary functional analysis of BcGRF8 in nitrogen metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1144748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Qi, B.; Hao, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, G.; Chen, R.; Song, S. Appropriate NH4+/NO3– ratio triggers plant growth and nutrient uptake of flowering Chinese cabbage by optimizing the pH value of nutrient solution. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 656144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Yi, L.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, G.; Chen, R. Effects of ammonium and nitrate ratios on plant growth, nitrate concentration and nutrient uptake in flowering Chinese cabbage. Bangl. J. Bot. 2017, 46, 1259–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, M.H.; Lam, H.M.; van de Loo, F.J.; Coruzzi, G. A PII-like protein in Arabidopsis: putative role in nitrogen sensing. PNAS 1998, 95, 13965–13970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ródenas, R.; Vert, G. Regulation of root nutrient transporters by CIPK23: ‘One kinase to rule them all’. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 62, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giehl, R.; Laginha, A.M.; Duan, F.; Rentsch, D.; Yuan, L.; von Wirén, N. A critical role of AMT2;1 in root-to-shoot translocation of ammonium in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant. 2017, 10, 1449–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jiang, D.; Wang, J.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, H.; Dai, X.; Ren, H.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Y. A high-continuity genome assembly of Chinese flowering cabbage (Brassica rapa var. parachinensis) provides new insights into Brassica genome structure evolution. Plants 2023, 12, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Kole, C. The Brassica rapa genome. In Compendium of Plant Genomes; Chittaranjan, K., Mohanpur, W.B., Eds.; Springer-Verlag GmbH Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvemini, F.; Marini, A.; Riccio, A.; Patriarca, E.J.; Chiurazzi, M. Functional characterization of an ammonium transporter gene from Lotus japonicus. Gene 2001, 270, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filiz, E.; Akbudak, M.A. Ammonium transporter 1 (AMT1) gene family in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) bioinformatics, physiological and expression analyses under drought and salt stresses. Genomics 2020, 112, 3773–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, Y. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of ammonium transporter 1 (AMT1) gene family in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) and functional analysis of MeAMT1;1 in transgenic Arabidopsis. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, B.; Choi, S.S. Introns: The Functional Benefits of Introns in Genomes. Genomics Inform. 2015, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhong, L.; Huang, X.; Su, W.; Liu, H.; Sun, G.; Song, S.; Chen, R. BcAMT1;5 mediates nitrogen uptake and assimilation in flowering Chinese cabbage and improves plant growth when overexpressed in Arabidopsis. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzarrini, S.; Lejay, L.; Gojon, A.; Ninnemann, O.; Frommer, W.B.; von Wirén, N. Three functional transporters for constitutive, diurnally regulated, and starvation-induced uptake of ammonium into Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Zhuang, S.; Feng, Z.; Fan, J. Functional characterization of PsAMT1.1 from Populus simonii in ammonium transport and its role in nitrogen uptake and metabolism. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 208, 105255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranathunge, K.; El-kereamy, A.; Gidda, S.; Bi, Y.; Rothstein, S.J. AMT1;1 transgenic rice plants with enhanced NH4+ permeability show superior growth and higher yield under optimal and suboptimal NH4+ conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, X.; Hao, Y.; Su, W.; Liu, H.; Sun, G.; Chen, R.; Song, S. Ammonium transporter (BcAMT1.2 mediates the interaction of ammonium and nitrate in Brassica campestris. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The, S.V.; Snyder, R.; Tegeder, M. Targeting nitrogen metabolism and transport processes to improve plant nitrogen use efficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 11, 628366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Loqué, D.; Ye, F.; Frommer, W.B.; von Wirén, N. Nitrogen-dependent posttranscriptional regulation of the ammonium transporter AtAMT1;1. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, T.; Ludewig, U.; Neuhäuser, B. The kinase CIPK23 inhibits ammonium transport in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, F.; Neuhäuser, B.; Ludewig, U.; Schulze, W.X.; Yuan, L. Ammonium and nitrate regulate NH4+ uptake activity of Arabidopsis ammonium transporter AtAMT1;3 via phosphorylation at multiple C-terminal sites. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 4919–4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Ju, C.; Wang, C. Calcium signaling in plant mineral nutrition: From uptake to transport. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Hu, B.; Li, A.; Chu, C. NRT1.1s in plants: functions beyond nitrate transport. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 4373–4379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.; Lin, S.; Hu, H.; Tsay, Y. CHL1 Functions as a Nitrate Sensor in Plants. Cell 2009, 138, 1184–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procter, J.B.; Carstairs, G.M.; Soares, B.; Mourão, K.; Ofoegbu, T.C.; Barton, D.; Lui, L.; Menard, A.; Sherstnev, N.; Roldan-Martinez, D.; Duce, S.; Martin, D.M.A.; Barton, G.J. Alignment of Biological Sequences with Jalview. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Katoh, K., Ed.; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2231, pp. 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Xiang, N.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y. Genome-wide identification and functional analysis of the calcineurin B-like protein and calcineurin B-like protein-interacting protein kinase gene families in turnip (Brassica rapa var. rapa). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktorek-Smagur, A.; Hnatuszko-Konka, K.; Kononowicz, A.K. Flower bud dipping or vacuum infiltration—two methods of Arabidopsis thaliana transformation. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2009, 56, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivančič, I.; Degobbis, D. An optimal manual procedure for ammonia analysis in natural waters by the indophenol blue method. Water Res. 1984, 18, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene ID | Gene Name | Chr | Start | End | MW (kDa) |

pI | AA (aa) |

Instability index | GRAVY | TM | Subcellular localization |

Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bra_cxA05g029310.1 | BcAMT1.1 | A05 | 9051433 | 9052957 | 53.62 | 7.13 | 503 | 25.33 | 0.38 | 9 | Cell membrane | AMT1 |

| Bra_cxA09g068650.1 | BcAMT1.2 | A09 | 1262097 | 1263778 | 54.88 | 7.73 | 512 | 24.10 | 0.35 | 10 | Cell membrane | AMT1 |

| Bra_cxA07g035530.1 | BcAMT1.3 | A07 | 8638823 | 8640466 | 54.11 | 6.74 | 504 | 28.46 | 0.35 | 9 | Cell membrane | AMT1 |

| Bra_cxA01g016480.1 | BcAMT1.3-like | A01 | 20920458 | 20926484 | 50.79 | 5.87 | 476 | 26.46 | 0.39 | 10 | Cell membrane | AMT1 |

| Bra_cxA01g038520.1 | BcAMT1.4 | A01 | 4314030 | 4315548 | 53.66 | 5.7 | 501 | 26.06 | 0.43 | 10 | Cell membrane | AMT1 |

| Bra_cxA03g011620.1 | BcAMT1.4-like | A03 | 28109231 | 28110768 | 54.41 | 5.45 | 509 | 27.01 | 0.45 | 10 | Cell membrane | AMT1 |

| Bra_cxA03g025790.1 | BcAMT1.5 | A03 | 20119522 | 20121038 | 53.17 | 5.96 | 500 | 25.32 | 0.43 | 10 | Cell membrane | AMT1 |

| Bra_cxA05g037880.1 | BcAMT2.1 | A05 | 3982245 | 3986822 | 52.63 | 6.32 | 489 | 28.53 | 0.45 | 11 | Cell membrane | AMT2 |

| Bra_cxA04g005660.1 | BcAMT2.1-like | A04 | 23713465 | 23716475 | 52.52 | 7.28 | 488 | 25.86 | 0.45 | 11 | Cell membrane | AMT2 |

| Seq_1 | Seq_2 | Identity (%) | Ka | Ks | Ka/Ks | T/ (MYA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BcAMT1.3 | BcAMT1.3-like | 87.30 | 0.0394 | 0.4100 | 0.0962 | 13.6678 |

| BcAMT1.5 | BcAMT1.3 | 84.33 | 0.0903 | 0.6636 | 0.1360 | 22.1207 |

| BcAMT1.5 | BcAMT1.3-like | 81.04 | 0.0782 | 0.7431 | 0.1053 | 24.7684 |

| BcAMT1.4 | BcAMT1.4-like | 90.57 | 0.0454 | 0.4027 | 0.1129 | 13.4226 |

| BcAMT2.1 | BcAMT2.1-like | 92.84 | 0.0438 | 0.3165 | 0.1383 | 10.5503 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).