1. Introduction

Fresh products like fruits and vegetables have substantial economic and nutritional value. Once harvested from the fields, fruits and vegetables undergo significant deterioration of their physical and chemical properties [

1,

2]. Many techniques, such as packaging, chilling, chemical treatments, edible coatings, and modified atmosphere packaging. Among these, edible coatings are gaining popularity for preserving fruits and vegetables by lowering respiration rates and metabolic processes. It is due to their ability to block moisture and oxygen effectively. This assists in preserving fruit texture and minimizing weight loss during storage. In addition, edible coatings can be embedded with active substances like colorants, spices, nutrients as well as antimicrobial agents, which can hinder or delay the microbial spoilage of food products [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Edible coatings are thin layers made from safe materials, like proteins, polysaccharides, or lipids. They have a substantial role in the food sector as they are affordable, generate less waste, and provide protection even after opening the package [

2,

7]. The widespread utilization of synthetic compounds has sparked concerns regarding the environment and human well-being, which has led to increased investigations on the functionalities of organic natural materials, like biopolymers [

8,

9].

Among biopolymers, chitosan is widely used for the fabrication of edible coatings due to its excellent film-forming abilities, biocompatibility, and hydrophilicity. Chitosan is a naturally occurring polysaccharide known for its antibacterial and antifungal activity, and it is identified as the ideal natural alternative to synthetic polymers [

10,

11,

12]. There is growing interest in the potential applications of chitosan in packaging materials, because of the increasing demand for bio-functional materials from renewable resources [

13]. Chitosan-based films showed several advantages, but they also have some drawbacks, like weak mechanical strength [

14]. However, the mechanical and antimicrobial properties of chitosan coatings can be improved by the incorporation of organic or inorganic materials such as plasticizers, other polysaccharides, lipids, proteins, and nanoparticles into the polymer matrix to create a composite material [

14,

15,

16].

Various studies have reported that supplementing chitosan edible coatings with essential oils significantly enhances their effectiveness in extending the shelf life of fruits and vegetables [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Essential oils are compounds extracted from various plants, fruits, vegetables, and herbs, and they are known for their antimicrobial, antifungal, and antioxidant properties [

22,

23]. Frankincense essential oil is extracted from trees of the genus

Boswellia, which are indigenous to the Arabian Peninsula. This essential oil contains components like α-pinene, α-thujene, β-pinene, limonene, p-cymene, myrcene, and sabinene [

24]. Frankincense is used in a range of applications, including culinary and therapeutic contexts and it is widely used in Oman as a drink, gum, perfume, and to produce aromatic smoke [

24,

25,

26]. However, its ability to enhance the shelf life of food has not been evaluated previously.

In this study, we hypothesized that chitosan coatings with frankincense oil from Boswellia sacra could extend the shelf life of strawberries (Fragaria ananassa Duch) by decreasing microbial densities. Different concentrations of chitosan solution with and without frankincense essential oil were used as coatings for strawberries. The physical and chemical properties of coated strawberries were evaluated after storage. In addition, the antibacterial and antifungal properties of strawberries coated with chitosan and chitosan with frankincense oil were also measured.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coating Preparation

Four different solutions were prepared for this experiment: 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan and frankincense oil (1% Cs-Fr), and 3% chitosan and frankincense oil (3% Cs-Fr) solutions. Since chitosan is insoluble in pure water, an acidic medium was required to protonate the amino groups, enabling dissolution. For each solution, chitosan (SIGMA-ALDRICH, USA) was dissolved in 2% acetic acid (SIGMA-ALDRICH, USA) and kept under stirring for 24 h. Then, 4% NaOH (SIGMA-ALDRICH, USA) was added drop by drop to each solution until the pH reached 7. After the solutions were neutralized, 1% v/v frankincense oil (Natural Boswellia, Salalah, Oman) obtained from Omani Boswellia sacra was added to each of the 1% Cs-Fr and 3% Cs-Fr solutions and stirred thoroughly for 24h to form a homogeneous mixture with uniform oil droplet dispersion. Due to the low concentration of the oil and the stabilizing nature of chitosan and resin in frankincense, no additional emulsifying agents were added. Monoterpenes, such as alpha-pinane, beta-pinene, 3-careene, and delta-limonene, were dominant in frankincense oil. Oxygenated monoterpenes, such as 2.3-epoxycarane, were found in lower quantities. Esters, sesquiterpenes, and boswellic acids were observed in trace amounts.

2.2. Coating Characterization

2.2.1. FTIR, SEM and Water Contact Angle

Prepared Cs and Cs-Fr solutions were cast onto petri dishes and allowed to dry at room temperature (26 °C) for 3 to 4 days and then coatings were obtained for surface analysis. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was used to identify the chemical structure of the coating and the possible interactions between chitosan and frankincense essential oil. Cs and Cs-Fr were analyzed using a Frontier (FTIR) spectrometer (Perkin Elmer USA), in a spectral range from 4000 to 500 cm−1. Before the analysis, the films were made on clean glass and dried at room temperature in a desiccator for 24 hours to remove any residual moisture. Thin sections of each film were cut and directly placed on the crystal surface of the FTIR without additional treatment. Spectra were recorded in absorbance mode with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and 32 scans per sample. Background spectra were collected before each measurement and automatically subtracted from the sample spectra to ensure proper calibration and minimize atmospheric interference.

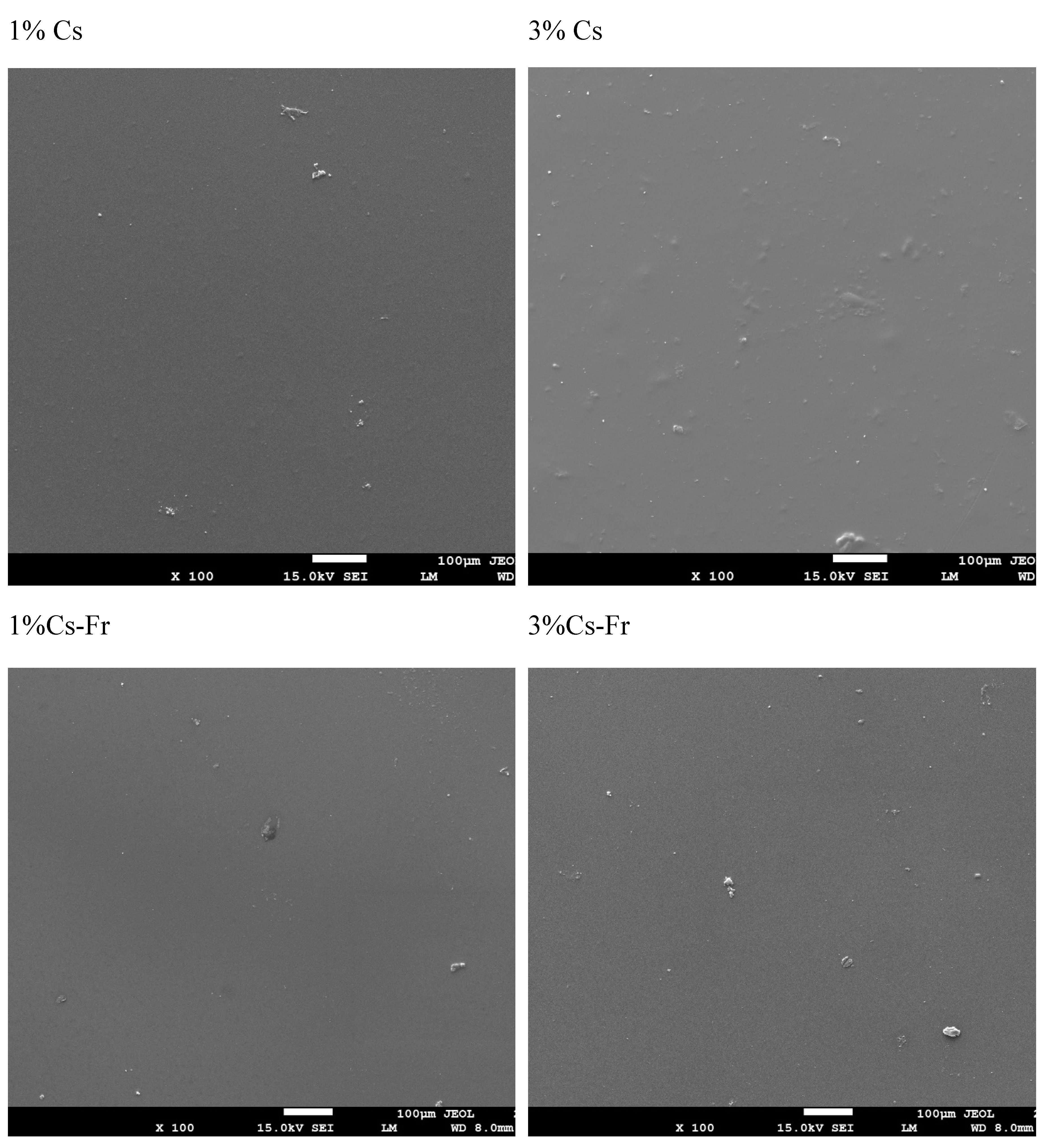

To determine the surface morphology of the coating, a scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used. Although SEM imaging of the strawberry surface was attempted, the non-flat, hydrated nature of the fruit skin did not allow for obtaining clear and focused micrographs. Therefore, the microstructure of the coating material was analyzed using films prepared from the same coating solution, providing representative insight into the morphology of the chitosan and chitosan–frankincense oil matrix. The films were visualized at 100-1000× magnification by JEOL JSM-7200 (JEOL Ltd., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan) working at 20 kV.

To determine coating wettability, the static contact angles of the coatings were measured using a Theta Lite Attension tensiometer (Biolin Scientific, Sweden) using the sessile drop technique [

27]. The measurements were conducted by averaging over three different locations of the surface of the coating, and the mean water contact angles (WCA) were reported.

2.2.2. Antibacterial Assay

The antimicrobial effect of Cs and Cs-Fr coatings on bacterial growth was evaluated by suspension culture medium. Antibacterial activity of the samples was tested against pathogenic bacteria, Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), obtained from the Sultan Qaboos University culture collection. To make a film, one ml of each prepared aqueous solution (1%Cs, 3%Cs, 1%Cs-Fr, and 3%Cs-Fr) was placed in each well of a 24-well plate (Sigma Aldrich, USA) and allowed to dry for 3 days under sterile conditions at room temperature. Prior to the assay, the bacterial strain E. coli was cultivated in the nutrient broth (Sigma Aldrich, USA) for 24 h at 37 °C. The turbidity was adjusted to achieve an optical density (OD) equivalent to McFarland 0.5 (approximately 105–106 CFU/mL). Nutrient broth (2 ml) was added to each well of a 24-well plate (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Additionally, ten μl of fresh bacterial culture was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h and 48 h. After incubation, the number of bacterial colony forming units per mL (CFU/mL) was calculated in each sample. All samples in the experiment were tested in triplicate, and wells with no coating solutions were used as controls.

2.3. Coating Application and Experiment

Strawberries were purchased from AL Mawaleh Souq (Gold Business, Jordan). Thirty strawberries of weight ranging from 10 to 13 g were dipped in each of the previously prepared chitosan and chitosan-frankincense solutions (see above) for five minutes and then allowed to dry for 30 min at room temperature (

Supplementary Figure S1). Uncoated strawberries were used as a control group. After coating, the samples were stored under refrigerated conditions at 4 ± 1 °C in a refrigerator with natural air ventilation and an average relative humidity of approximately 85–90% until further analysis. During the storage period of eight days, coated strawberries were tested for their color, moisture content, pH, total soluble solids (TSS), and hardness (see below). The samples were analyzed at 20 °C for 0, 2, 6, and 8 days.

2.3.1. Physical Properties of Strawberries

Color determination was done using a CM-3600d spectrophotometer (Minolta Co., Tokyo, Japan). The measurement was taken five times in different spots of each fruit. Five randomly selected fruits were used for each treatment. The hue angle was calculated as follows: Hue angle (H) = tan−1 (b/a), where a, b, and L values represent color intensity. To evaluate the degree of color variation in strawberry samples among coatings, total color change was calculated as follows:

Total Color Change (∆E) = Equation (1),

where L0, a0, and b0 are the values from day 0, and L, a, and b represent the corresponding color values measured on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8.

The texture of the strawberry was subjected to using a Texture Profile Analyser (Model: TA-XTplus, Stable Micro Systems, Surrey, England) to assess hardness. A cylindrical stainless-steel probe (2 mm diameter) was used to penetrate the samples at a constant speed of 1mm s-1. The hardness of each sample was determined by recording the maximum force value required during the penetration cycle. Five randomly selected fruits were used for each treatment. The total soluble solids in homogenized samples were measured using a refractometer (ATAGO, USA). Three replicated measurements were used for each treatment. For pH measurement, 5 g of the samples were homogenized of strawberries 45 ml of distilled water, and then the pH was measured using a pH meter (JENWAY, UK). Three replicated measurements were used for each treatment. For moisture content determination, 3 g samples were dried in a vacuum oven for 24 h at 70 °C. The moisture content was determined from the initial and final mass after drying. Three replicated measurements were used for each treatment.

2.3.2. Microbiological Analysis of Strawberries

For microbiological analysis, 10 g of strawberries were homogenized in 90 ml of peptone water (OXOID, England). For bacterial count determination, 100 μl of the mixture was cultured on nutrient agar (Hi-Media, India) and then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Bacterial count was taken after incubation, and the number of colony forming units (CFU/mL) was calculated. For yeast and mold counts, samples were cultured on potato dextrose agar (Liofilchem, Italy) and incubated at 30 °C for 5 days. The counts between 30 and 300 CFU were considered. All tests were done in triplicate.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). A one-way ANOVA was performed to compare different treatments at each time point. Before analysis, data normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was evaluated with Levene’s test. When ANOVA revealed significant differences, Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post hoc test was applied to identify pairwise differences.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Coating Characterization

3.1.1. FTIR, SEM and Water Contact Angle

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis was performed on films prepared from the same chitosan–frankincense oil coating solutions used for fruit application (

Figure 1). Direct SEM imaging of the coated strawberries was not feasible due to the uneven and highly hydrated surface of the fruit, which prevented obtaining clear and focused micrographs. Therefore, the film form was used to visualize the morphology of the dried coating material. SEM showed that 3% chitosan film was thicker compared to 1% chitosan (

Figure 1). The addition of frankincense oil did not affect the structure of the surface of the film.

Water contact angle (WCA) measurements showed that all coatings were hydrophilic. This is due to the presence of chitosan amino groups. The highest WCA was observed in 1% Cs (59.3 ± 6

o). The WCA of 3% Cs (56.8 ± 4

o) was not significantly different (ANOVA, LSD, p<0.05) from 1%Cs. Similar WCA for chitosan coatings were reported earlier [

15]. The addition of frankincense oil increased the hydrophobicity of the surface. The WCA of 1% Cs-Fr (65.5 ± 2

o) was significantly higher (ANOVA, LSD, p<0.05) than 1% Cs. This could be due to changes in the surface chemistry and hydrophobic properties of oil [

25]. However, the addition of chitosan to 3% significantly reduced the WCA of composite coating (3% Cs-Fr = 52.0 ± 5

o).

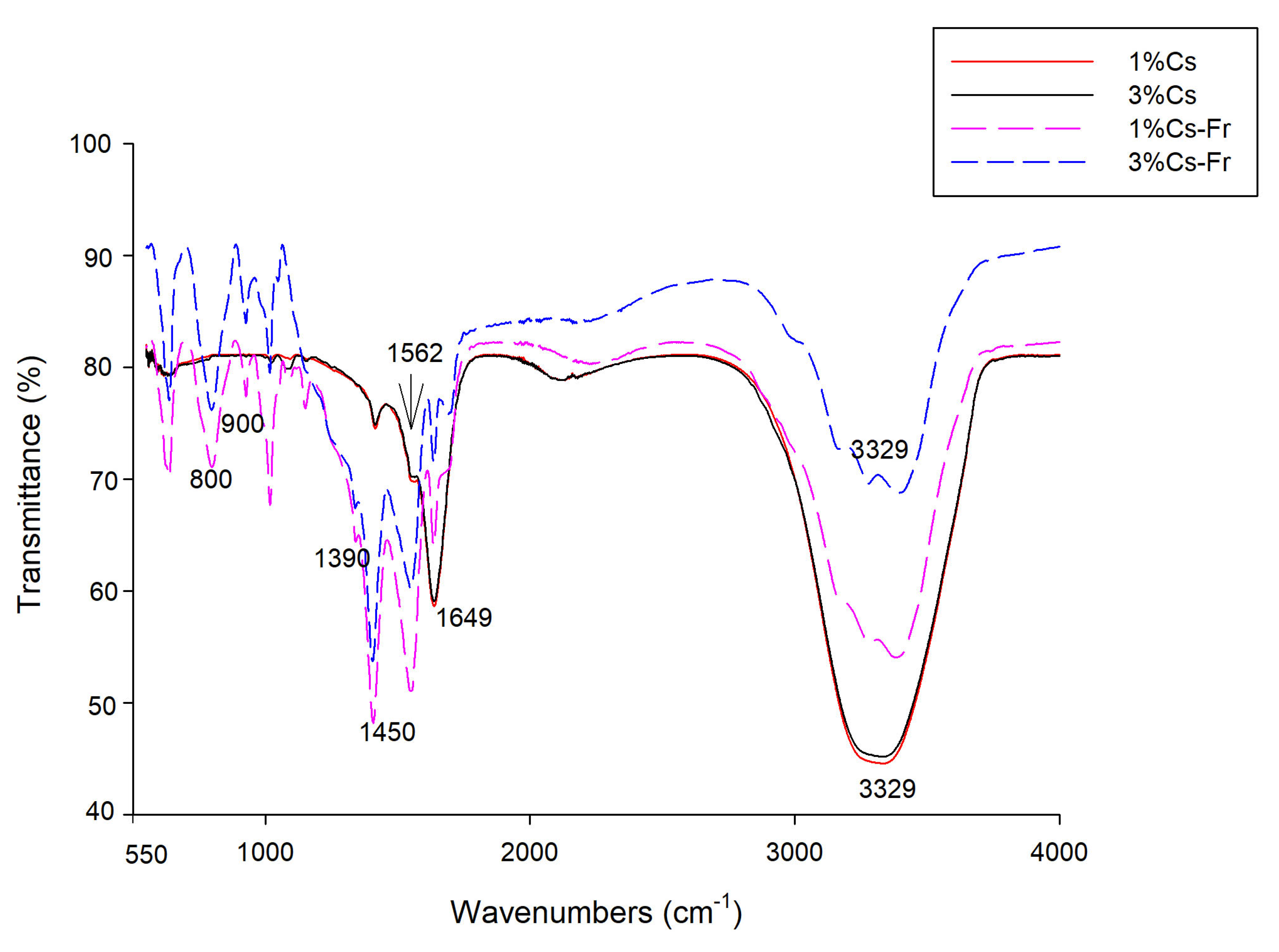

The FTIR spectra of all coatings are shown in

Figure 2. The FTIR spectra of 1% and 3% chitosan coatings were similar. Characteristic stretching of chitosan at 1562 cm

−1 of amide II, 1649 cm

−1 of amide I, and 3329 cm

−1 of N-H and O-H could be observed [

10]. The peak around 1050 cm

-1 represents glycosidic bonds in chitosan. The addition of frankincense essential oil changed the FTIR spectra (

Figure 2). First, the above-mentioned chitosan characteristic peaks became less pronounced. Second, additional peaks appeared in the region 620 – 1560 cm

−1. Bands in the region 800-900 cm

−1 are associated with out-of-plane C-H banding in vinyl and aromatic groups. These peaks are specific to frankincense oil and differentiate it from other essential oils [

28]. Strong CH

2 and CH

3 deformation bands around 1450 and 1390 cm

−1 are related to vibrations of terpenoid hydrocarbons, specifically due to the bending of these groups. These are characteristic of saturated hydrocarbons [

28]. Peaks 1635-1650 cm

−1 indicate the presence of alkenes (C=C stretching) characteristic of monoterpenes, like limonene, which is dominant in frankincense essential oil [

29].

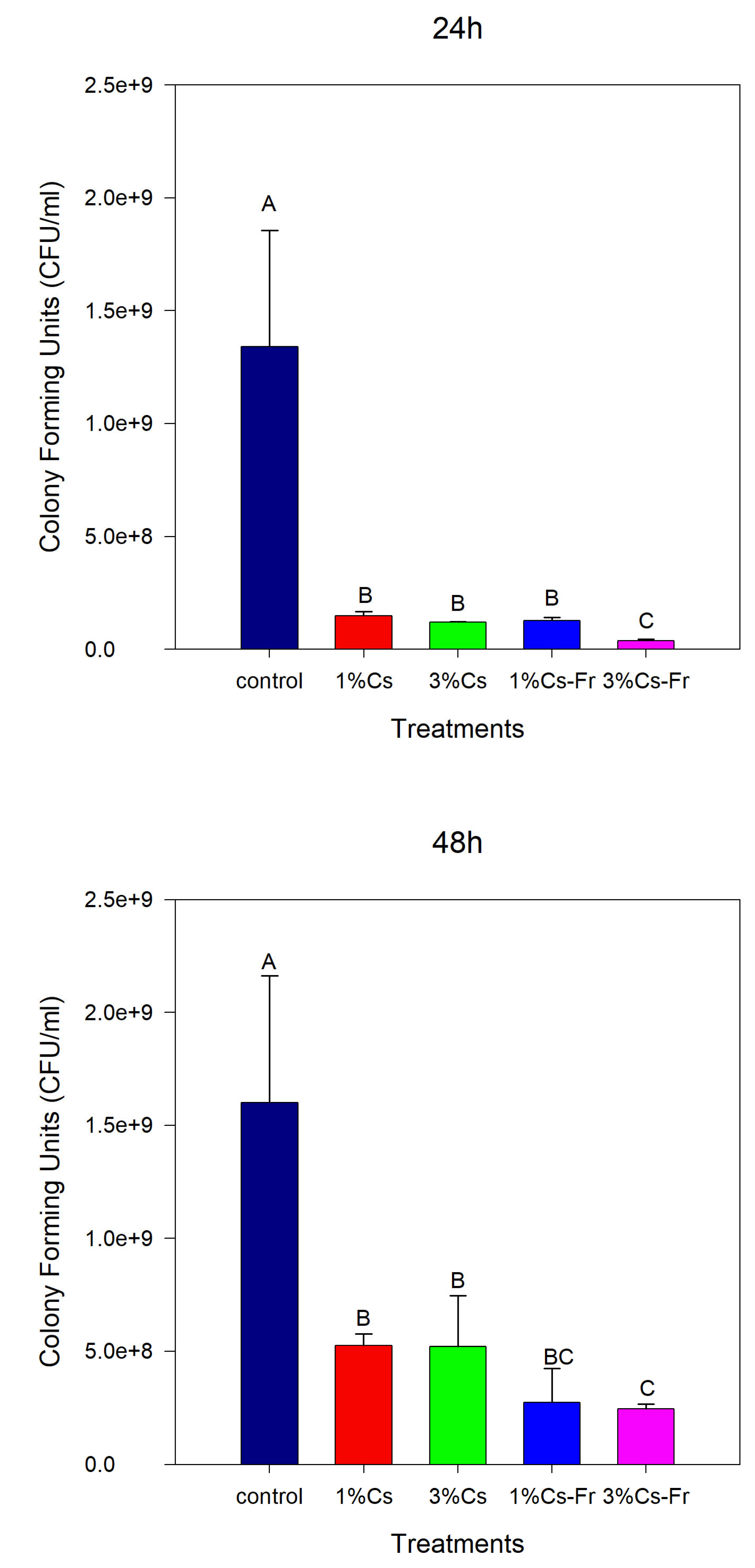

3.1.2. Antibacterial Activity of Coatings

The antibacterial activity of the prepared coatings was evaluated against the bacteria

E. coli (

Figure 3). The coatings affected bacterial growth significantly (ANOVA, p<0.05) compared to the control, and bacterial growth was significantly different (ANOVA, p<0.05) after 24 and 48 h. After 24 h, the lowest bacterial count was observed with 3% Cs-Fr coating (3.8×10

7 CFU/mL). It was three-fold lower than in the control (ANOVA, LSD, p<0.05) and significantly lower (ANOVA, LSD, p<0.05) than 1% Cs-Fr. After 48 h of incubation, bacterial counts in all samples were increased (

Figure 3). However, bacterial counts in all tested coatings were significantly different from the control sample (ANOVA, LSD, p<0.05). Addition of frankincense oil significantly reduced the number of

E. coli CFU (ANOVA, LSD, p<0.05). Conversely, after 48h, no significant difference was observed between 1% Cs-Fr (2.8×10

8 CFU/mL) and 3% Cs-Fr coatings (2.5×10

8 CFU/mL). This result confirms the continuous antibacterial effect of frankincense essential oil regardless of chitosan concentration.

The antibacterial activity of chitosan against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria such as

Staphylococcus aureus and

E. coli has been reported earlier [

30,

31]. Chitosan is known to interact with the cell surface of the bacteria, resulting in the permeabilization of the cell membrane, which causes the leakage of intracellular substances and eventually cell death. Some research also showed that chitosan can affect DNA expression by binding with nucleic acid, leading to inhibition of bacterial growth and reproduction and eventually cell death [

32,

33,

34,

35].

The antimicrobial activity of chitosan can be enhanced when combined with other antimicrobial agents, such as essential oils. Several studies revealed the increase in antimicrobial activity of chitosan incorporated with different essential oils, such as basil, cinnamon, mandarin, lemon grass, and clove [

36,

37,

38,

39]. This could explain our findings that chitosan coatings with frankincense essential oil could increase antibacterial activity.

Frankincense essential oil has been previously reported to exhibit antimicrobial activity against various bacterial pathogens, including

S. aureus,

Bacillus spp.,

E coli,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Enterococcus faecalis [

40,

41,

42,

43]. The antimicrobial activity of frankincense was attributed to its chemical composition, which is dominated by the presence of monoterpenes [

29,

44]. The presence of these terpenes, especially α-pinene and limonene, can change bacterial cell morphology by disrupting of cell membrane and causing cell death [

45].

3.2. Experiment with Coated Strawberries

3.2.1. Physical Properties of Strawberries

The moisture content of the strawberries varied between 88% and 92% across the different treatments (

Table 1). The results indicated that there was no significant difference in moisture content between the different treatments (ANOVA, p = 0.88). This implies that the moisture content of the strawberries was relatively consistent during the experiment. Overall, the coatings did not have a significant impact on the moisture content of the strawberries.

Table 2 presents the pH variations observed in strawberries that were coated and uncoated. It can be observed that strawberries coated with 1%Cs, 3%Cs, and 1%Cs-Fr, as well as 3% Cs-Fr, exhibited slight variations in pH throughout the experiment (

Table 2). There were no significant differences in pH between the different treatments (ANOVA, p=0.44). This suggests that the coating did not have any significant impact on the pH of strawberries.

The total soluble solids (TSS) in the strawberries decreased to approximately 5- and 6-degrees Brix in the strawberries coated with 1% Cs, 1% Cs-Fr, and the uncoated strawberries (

Table 3). On the other hand, on day four, strawberries coated with 3% chitosan (3% Cs) and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) showed the highest TSS percentage. However, there were no significant differences in TSS between the different treatments (ANOVA, p = 0.44). This suggests that the variations in TSS observed among the treatments were not statistically significant.

The changes in color of coated strawberries are shown in

Table 4. During the study, the strawberries coated with 1% chitosan (1% Cs) exhibited the lowest overall color change (8%), which was comparable to the control group with no coating (6%). In contrast, strawberries coated with 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs-Fr) showed the highest color change (22%,

Table 4). These changes in the color over time indicate the progression of strawberry aging. However, the hue angle values, which describe the perceived color of the strawberries, did not vary significantly among the coating treatments (ANOVA, p= 0.151). This suggests that the coatings did not alter the color of the strawberries.

The hardness of the uncoated samples decreased by day 6 of the experiment (

Table 5). Conversely, the strawberries coated with 1% chitosan (1% Cs) and 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs-Fr) exhibited relatively stable hardness levels over the course of the study. For the strawberries coated with 3% chitosan (3% Cs) and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs-Fr), the hardness initially decreased but started to increase again on day 8. However, the statistical analysis showed no significant differences in hardness among the different treatments over time (ANOVA, p-value=0.09). This suggests that hardness did not change significantly between different treatments in this experiment.

Overall, our study indicated that 1% and 3% chitosan coatings did not significantly impact the color, pH, moisture content, total soluble solids, or hardness of coated strawberries. This result is consistent with previous research that showed minimal or no effect on the quality attributes of strawberries coated with chitosan [

46,

47]. For instance, Pavinatto et al. [

48] showed that strawberries coated with glycerol-based chitosan films were well-protected from physical damage and microorganisms, without affecting their appearance, scent, texture, or flavor. Similarly, Perdones et al. [

49] reported that chitosan coatings did not noticeably affect the acidity, pH, or soluble solid content (TSS) of strawberries during storage.

The effectiveness of chitosan edible coating on the quality characteristics of coated fruits was found to be highly dependent on various factors, such as chitosan type and its concentrations, specific formulation of the coating, and the food product used [

50,

51,

52]. The interaction mechanism of chitosan with fruits was reported to be highly related to their physiological and metabolic processes [

53]. Chitosan coatings have been demonstrated to create a gas barrier that inhibits respiration and minimizes starch conversion into sugar, leading to lower TSS content in fruits. This process ensures firmness and delays the color change of fruits, resulting in slowing of the ripening process and reduction of weight loss [

54,

55,

56].

For the first time, strawberries were coated with 1% and 3% chitosan and frankincense oil coatings. No significant changes were observed in the color, pH, moisture content, total soluble solids, or hardness of strawberries coated with chitosan and frankincense oil. On the contrary, the addition of lemon essential oil to film-forming dispersions reduced the rate of respiration of strawberries [

49]. Similarly, the coating composed of 0.5% chitosan and 2 mM cinnamic acid was found to influence TSS, firmness, hue angle and weight loss of tomato samples after 13 days of storage [

57]. At the same time, incorporation of essential oils into chitosan coating was found to increase the shelf life of fruits like strawberries, apples, and passion by reducing respiration rate and enhancing antioxidant capacity, which leads to reducing oxidative stress [

18,

58].

3.2.2. Microbiological Analysis of Strawberries

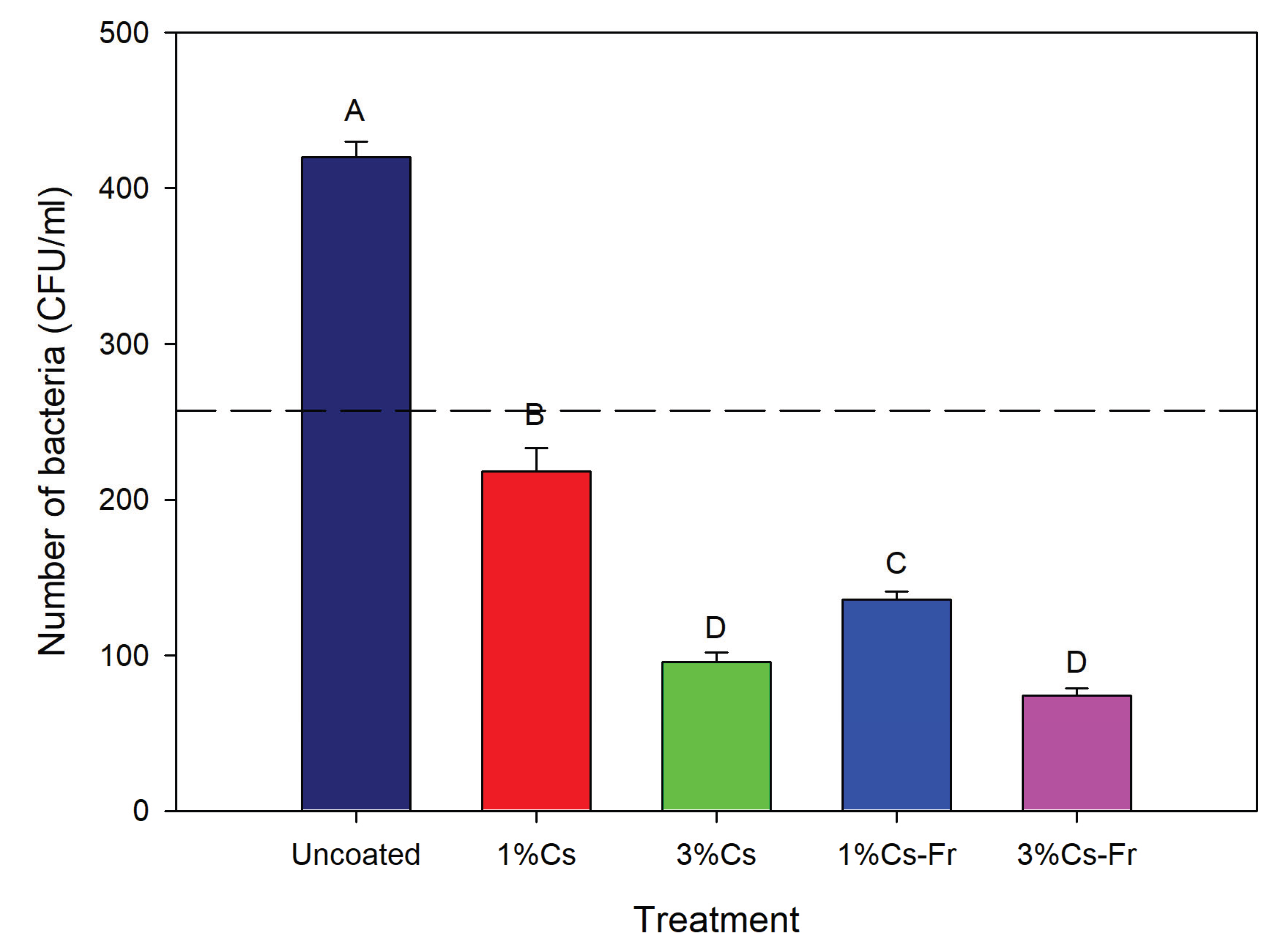

During the experiment, bacterial count on the uncoated control strawberries increased 1.6-fold, reaching the highest level of 420 CFU/mL by the end of the storage period (

Figure 4). Alternatively, the strawberries covered with 3% Cs-Fr had the lowest bacterial count (74 CFU/mL). Chitosan and chitosan-frankincense coatings decreased the number of bacteria during the experiment (

Figure 4). There were significant differences between all treatments (ANOVA, p= 8.32E

-17). The addition of frankincense to 1% of chitosan significantly reduced (ANOVA, LSD, p<0.05) the number of bacteria by 1.6-fold. However, the addition of frankincense in 3% Cs-Fr did not significantly reduce the number of bacteria in strawberries at the end of our experiment compared to 3%Cs (ANOVA, LSD, p>0.05). No yeast and or mold was detected in any of the samples throughout the experiment.

Chitosan showed fungicidal effects on several fungal pathogens in plants and humans [

59,

60,

61]. The antifungal activity of frankincense was also proved against various fungal pathogens such as

Malassezia furfur, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus ochraceus, Aspergillus niger, Penicillium citrinum, Alternaria alternate, and

Fusarium solani [

40,

41,

62].

Previous research reported the enhancement of the antimicrobial activity of chitosan when applied to food with the addition of essential oils. For example, chitosan antifungal activity was increased by adding lemon essential oil in both in vitro testing and strawberry cold storage [

49]. Similarly, Popescu et al. [

18] reported a significant reduction in fungal growth on strawberries coated with chitosan incorporated with sea buckthorn oil after 7 days of storage. The shelf-life of roast duck slices treated with chitosan incorporated with cinnamon and oregano essential oils was prolonged by at least 7 days compared to that of the control [

13].

A chitosan-based edible film enriched with frankincense essential oil combines the natural antimicrobial properties of both chitosan and frankincense. This edible film represents a novel approach to food preservation. This film can effectively inhibit bacterial growth, thereby extending the shelf life of food products. This study tested this film on strawberries; however, such chitosan-frankincense films can be applied to other fresh products, like vegetables, meat, and dairy. Frankincense is widely used in Oman and other Arab countries in beverages like tea, water, yogurt, ice cream, and laban [

24,

25,

26]. It is considered safe for consumption and is appreciated for its distinctive and pleasant flavour. The incorporation of frankincense essential oil into edible films not only enhances antimicrobial efficacy but may also offer a new flavor that aligns with local dietary preferences. However, further studies are needed to evaluate such films in terms of taste, consumer preference, and safety. In particular, the changes in antioxidant activity and sensory characteristics of coated strawberries during storage need to be studied in future studies to better understand the coating’s potential for maintaining nutritional and consumer-acceptable quality.

4. Conclusions

Chitosan and frankincense edible coating were developed to improve the postharvest quality and shelf life of the strawberries during the storage period. Our study suggested that chitosan and chitosan-frankincense essential oil coatings did not significantly affect the physical properties of coated strawberries, like color, pH, moisture content, total soluble solids, and hardness. However, after 8 days of storage, the chitosan–frankincense essential oil coatings significantly reduced bacterial growth, thereby contributing to the extended shelf life of strawberries. These findings highlight the potential of chitosan–frankincense oil coatings as a natural preservative method for maintaining strawberry stability during cold storage.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

RAM –Investigation, writing original draft and editing, visualization, validation, formal analysis, data curation. SD- Writing, review and editing, visualization, resources, investigation, validation, supervision, project administration, methodology, funding acquisition, data curation, conceptualization. LAN- writing original draft and editing, visualization, validation, formal analysis, data curation, supervision, methodology. MSR- writing, review and editing, validation, supervision, resources, project administration. NAH- writing, review and editing, validation, supervision, resources, project administration.

Funding

The authors acknowledged the following projects from Sultan Qaboos University CR/--/DVC/NRC/24/001, CL/SQU-SHOU/AGR/24/01, IG/AGR/FISH/24/01 and the Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation RC/SR-DVC/CEMB/22/01, Omantel Grant EG/SQU-OT/20/01.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the authors by a request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express thanks to Dr. Zahra AL-Khrousi (SQU). Dr. Jamal Al- Sabahi (SQU) and Dr. Htet Htet (SQU) for their help with the analysis of the samples. The authors acknowledged CAARU for SEM microphotographs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hussein, Z.; Fawole, O.A.; Opara, U.L. Harvest and postharvest factors affecting bruise damage of fresh fruits. Hortic. Plant J. 2020, 6(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, H.E.; Aziz, M.S.A. Development of active edible coating of alginate and aloe vera enriched with frankincense oil for retarding the senescence of green capsicums. LWT 2021, 145, 111341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalili, M.; Rahman, S.; Al-Habsi, N. Date Seed–Added Biodegradable Films and Coatings for Active Food Packaging Applications: A Review. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2025, 38(6), 445–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blancas-Benitez, F.J.; Montaño-Leyva, B.; Aguirre-Güitrón, L.; Moreno-Hernández, C.L.; Fonseca-Cantabrana, Á.; Romero-Islas, L.C.; González-Estrada, R.R. Impact of edible coatings on quality of fruits: A review. Food Control 2022, 139, 109063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Xie, Y.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, H.; Yao, W. Application of edible coating with essential oil in food preservation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59(15), 2467–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.S.; Ejaz, S.; Anjum, M.A.; Ali, S.; Hussain, S.; Ercisli, S.; Ilhan, G.; Marc, R.A.; Skrovankova, S.; Mlcek, J. Improvement of postharvest quality and bioactive compounds content of persimmon fruits after hydrocolloid-based edible coating application. Horticulturae 2022, 8(11), 1045, (MDPI). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Kaur, P.; Sadhu, S.D. Edible Coating for Improvement of Horticulture Crops. In Packaging and Storage of Fruits and Vegetables; Apple Academic Press: 2021; pp. 89–107.

- Baranwal, J.; Barse, B.; Fais, A.; Delogu, G.L.; Kumar, A. Biopolymer: A sustainable material for food and medical applications. Polymers 2022, 14(5), 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Gopi, S.; Amalraj, A. Biopolymers and their industrial applications: From plant, animal, and marine sources, to functional products. Elsevier, 2020.

- Al-Naamani, L.; Dutta, J.; Dobretsov, S. Nanocomposite zinc oxide-chitosan coatings on polyethylene films for extending storage life of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus). Nanomaterials 2018, 8(7), 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.W.; Riaz, T.; Yasmin, I.; Leghari, A.A.; Amin, S.; Bilal, M.; Qi, X. Chitosan-based materials as edible coating of cheese: A review. Starch-Stärke 2021, 73((11–12)), 2100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ismail, B.B.; Cheng, H.; Jin, T.Z.; Qian, M.; Arabi, S.A.; Liu, D.; Guo, M. Emerging chitosan-essential oil films and coatings for food preservation — A review of advances and applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 273, 118616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Q.; Xu, C.; Deng, S.; Kang, Y.; Fan, M.; Li, L. Application of functionalized chitosan in food: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 235, 123716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Naamani, L.; Dobretsov, S.; Dutta, J. Chitosan-zinc oxide nanoparticle composite coating for active food packaging applications. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 38, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Belushi, M.A.; Myint, M.T.Z.; Kyaw, H.H.; Al-Naamani, L.; Al-Mamari, R.; Al-Abri, M.; Dobretsov, S. ZnO nanorod-chitosan composite coatings with enhanced antifouling properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 162, 1743–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erceg, T.; Šovljanski, O.; Stupar, A.; Ugarković, J.; Aćimović, M.; Pezo, L.; Tomić, A.; Todosijević, M. A comprehensive approach to chitosan-gelatine edible coating with β-cyclodextrin/lemongrass essential oil inclusion complex — Characterization and food application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 228, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossen, M.A.; Shimul, I.M.; Sameen, D.E.; Rasheed, Z.; Tanga, W.; Chen, M.; Liu, Y. Chitosan/gelatin coating loaded with ginger essential oil/β-cyclodextrin inclusion complex on quality and shelf life of blueberries. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, P.-A.; Palade, L.M.; Nicolae, I.-C.; Popa, E.E.; Miteluț, A.C.; Drăghici, M.C.; Matei, F.; Popa, M.E. Chitosan-Based Edible Coatings Containing Essential Oils to Preserve the Shelf Life and Postharvest Quality Parameters of Organic Strawberries and Apples during Cold Storage. Foods 2022, 11(21), 3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarengaowa, Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Feng, K.; Hu, W. Screening of essential oils and effect of a chitosan-based edible coating containing cinnamon oil on the quality and microbial safety of fresh-cut potatoes. Coatings 2022, 12(10), 1492. [CrossRef]

- Valipour Kootenaie, F.; Ariaii, P.; Khademi Shurmasti, D.; Nemati, M. Effect of chitosan edible coating enriched with eucalyptus essential oil and α-tocopherol on silver carp fillets quality during refrigerated storage. J. Food Saf. 2017, 37(1), e12295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viacava, G.E.; Cenci, M.P.; Ansorena, M.R. Effect of chitosan edible coatings incorporated with free or microencapsulated thyme essential oil on quality characteristics of fresh-cut carrot slices. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15(4), 768–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annaz, H.; Annaz, H.; Ajaha, A.; Bouayad, N.; El Fakhouri, K.; Laglaoui, A.; El Bouhssini, M.; Sobeh, M.; Rharrabe, K. Chemical profiling and bioactivities of essential oils from Thymus capitatus and Origanum compactum against Tribolium castaneum. Heliyon 2024, 10(5), e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddou, M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Taibi, M.; Baraich, A.; Loukili, E.H.; Bellaouchi, R.; Saalaoui, E.; Asehraou, A.; Salamatullah, A.M.; Bourhia, M. Exploring the multifaceted bioactivities of Lavandula pinnata L. essential oil: Promising pharmacological activities. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1383731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrathi, H. Frankincense’s Ritual Uses in Oman. Al-Muntaqa: New Perspect. Arab Stud. 2023, 6(3), 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- Borotová, P.; Čmiková, N.; Galovičová, L.; Vukovic, N.L.; Vukic, M.D.; Tvrdá, E.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Kluz, M.I.; Puchalski, C.; Schwarzová, M. Antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-insect properties of Boswellia carterii essential oil for food preservation improvement. Horticulturae 2023, 9(3), 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Etminan, A.; Rahmati, A.; Behjati Moghadam, M.; Ghaderi Segonbad, G.; Homayouni Tabrizi, M. Incorporation of Boswellia sacra essential oil into chitosan/TPP nanoparticles towards improved therapeutic efficiency. Mater. Technol. 2022, 37(11), 1703–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fori, M.; Dobretsov, S.; Myint, M.T.Z.; Dutta, J. Antifouling properties of zinc oxide nanorod coatings. Biofouling 2014, 30(7), 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saied, M.A.; Kamel, N.A.; Ward, A.A.; et al. Novel Alginate Frankincense Oil Blend Films for Biomedical Applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 90, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbood, S.M.; Kadhim, S.M.; Al-Ethari, A.Y.H.; Al-Qaisia, Z.H.; Mohammed, M.T. Review on Frankincense Essential Oils: Chemical Composition and Biological Activities. Misan J. Acad. Stud. 2022, 21(44), 332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Ardean, C.; Davidescu, C.M.; Nemeş, N.S.; Negrea, A.; Ciopec, M.; Duteanu, N.; Negrea, P.; Duda-Seiman, D.; Musta, V. Factors influencing the antibacterial activity of chitosan and chitosan modified by functionalization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22(14), 7449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudouaia, N.; Benine, M.L.; Fettal, N.; Abbouni, B.; Bengharez, Z. Antibacterial Action of Chitosan Produced from Shrimp Waste Against the Growth of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Proteus mirabilis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Waste Biomass Valorization 2024, 15(3), 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.-L.; Deng, F.-S.; Chuang, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-H. Antimicrobial actions and applications of chitosan. Polymers 2021, 13(6), 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, W.; Du, J.; Sun, Y.; Xie, J. Insight into the antibacterial activity and mechanism of chitosan caffeic acid graft against Pseudomonas fluorescens. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58(3), 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhuang, S. Antibacterial activity of chitosan and its derivatives and their interaction mechanism with bacteria: Current state and perspectives. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 138, 109984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-C.; Nah, J.-W.; Park, Y. pH-dependent mode of antibacterial actions of low molecular weight water-soluble chitosan (LMWSC) against various pathogens. Macromol. Res. 2011, 19(8), 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, G.; Sabbah, M.; Caputo, L.; Idbella, M.; De Feo, V.; Porta, R.; Fechtali, T.; Mauriello, G. Basil essential oil: Composition, antimicrobial properties, and microencapsulation to produce active chitosan films for food packaging. Foods 2021, 10(1), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdana, M.I.; Ruamcharoen, J.; Panphon, S.; Leelakriangsak, M. Antimicrobial activity and physical properties of starch/chitosan film incorporated with lemongrass essential oil and its application. LWT 2021, 141, 110934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Ahuja, A.; Sharma, B.; Kulshreshtha, A.; Kadam, A.; Dutt, D. Vapor Phase Antimicrobial Active Packaging Application of Chitosan Capsules Containing Clove Essential Oil for the Preservation of Dry Cakes. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17(3), 780–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, L. Mandarin (Citrus reticulata L.) essential oil incorporated into chitosan nanoparticles: Characterization, anti-biofilm properties and application in pork preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 185, 620–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kharousi, Z.S.; Mothershaw, A.S.; Nzeako, B. Antimicrobial Activity of Frankincense (Boswellia sacra) Oil and Smoke against Pathogenic and Airborne Microbes. Foods 2023, 12(18), 3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, V.; Schillaci, D.; Cusimano, M.G.; Rishan, M.; Rashan, L. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Frankincense Oils from Boswellia sacra Grown in Different Locations of the Dhofar Region (Oman). Antibiotics 2020, 9(4), 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, A.; Santacroce, L.; Iacob, R.; Mare, A.; Man, L. Antimicrobial Activity of Six Essential Oils Against a Group of Human Pathogens: A Comparative Study. Pathogens 2019, 8(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, B.M.B.; Juglair, M.M.; Alves, F.; Gabardo, M.C.L.; Bruzamolin, C.D.; Brancher, J.A. The antimicrobial activity of essential oils of thyme, oregano, copaiba, tea tree, and frankincense against Enterococcus faecalis. Brazil. J. Dev. 2022, 8(2), 9079–9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, K.; Alsayed, M.F. Antimicrobial Activity of Essential Oil of Boswellia carterii Birdw. Oleo Gum Resin and Its Chemical Composition. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2023, 26(2), 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorović, P.; Krstić Ristivojević, M.; Jović, M.; Ivković, Đ.; Nestorović Živković, J.; Gašić, U.; Dimkić, I.; Stojiljković, I.; Ristivojević, P. Antimicrobial Effect of Boswellia serrata Resin’s Methanolic Extracts Against Skin Infection Pathogens. Processes 2025, 13, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharuddin, M.; Rubiyanto, D. The use of chitosan-based edible coatings enriched with essential oils to improve storability of strawberries. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2370, 060007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, M.S.; To, X.T.; Le, Q.T.P.; Nguyen, L.L.P.; Friedrich, L.; Hitka, G.; Zsom, T.; Nguyen, T.C.T.; Huynh, C.Q.; Tran, M.D.T. Postharvest quality of hydroponic strawberry coated with chitosan-calcium gluconate. Prog. Agric. Eng. Sci. 2020, 16, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavinatto, A.; de Almeida Mattos, A.V.; Malpass, A.C.G.; Okura, M.H.; Balogh, D.T.; Sanfelice, R.C. Coating with chitosan-based edible films for mechanical/biological protection of strawberries. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 1004–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdones, A.; Sánchez-González, L.; Chiralt, A.; Vargas, M. Effect of chitosan–lemon essential oil coatings on storage-keeping quality of strawberry. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2012, 70, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, A.; Triunfo, M.; Ianniciello, D.; Tedesco, F.; Salvia, R.; Scieuzo, C.; Schmitt, E.; Capece, A.; Falabella, P. Insect-derived chitosan, a biopolymer for the increased shelf life of white and red grapes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhoub, A.; Guendouz, A.; El Alaoui-Talibi, Z.; Koraichi, S.I.; Raouan, S.E.; Delattre, C.; El Modafar, C. Preparation of bioactive film based on chitosan and essential oils mixture for enhanced preservation of food products. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.; Shi, D.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Huang, W.; Liu, Y. Properties of modified chitosan-based films and coatings and their application in the preservation of edible mushrooms: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 132265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J., Yuan, Y., Liu, Y., Li, X., & Wu, S. Application of chitosan in fruit preservation: A review. Food Chemistry: X. 2024, 101589. [CrossRef]

- Medany, M.S.; Enas, A.H.; Mohamed, E.N.; Yehia, A.H. Evaluation of active edible coating containing essential oil emulsions to extend shelf life of orange. J. Environ. Sci. 2022, 51(5), 35–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Yang, H.; Guo, X.; Bi, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Shui, Y.; Chen, C.; Zheng, Y. Effect of chitosan/Nano-TiO2 composite coatings on the postharvest quality and physicochemical characteristics of mango fruits. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 263, 109135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Deng, W.; Yu, L.; Shi, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhong, Y. Chitosan coatings with different degrees of deacetylation regulate the postharvest quality of sweet cherry through internal metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmai, W.N.S.M.; Latif, N.S.A.; Zain, N.M. Efficiency of edible coating chitosan and cinnamic acid to prolong the shelf life of tomatoes. J. Trop. Resour. Sustain. Sci. (JTRSS) 2019, 7(1), 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxumalo, K.A.; Fawole, O.A. Effects of chitosan coatings fused with medicinal plant extracts on postharvest quality and storage stability of purple passion fruit (Passiflora edulis var. Ester). Food Qual. Saf. 2022, 6, fyac016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, G.S.; Kaur, S.; Brar, S.K.; Verma, M. Green synthesis approach: Extraction of chitosan from fungus mycelia. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2013, 33(4), 379–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.-H.; Deng, F.-S.; Chang, C.-J.; Lin, C.-H. Synergistic antifungal activity of chitosan with fluconazole against Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, and fluconazole-resistant strains. Molecules 2020, 25(21), 5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xianghong, M.; Yang, L.; Kennedy, J.; Tian, S. Effects of chitosan and oligochitosan on growth of two fungal pathogens and physiological properties in pear fruit. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 81(1), 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Edani, A.J.M.; Hussein, S.F. Evaluation of the activity of alcoholic extract of frankincense (Boswellia spp.) against some dermatophytes and pathogenic fungi of plant crops. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 12(3), 408–414. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images of chitosan-based films prepared from coating solutions: (A) 1% chitosan (1% Cs), (B) 3% chitosan (3% Cs), (C) 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and (D) 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr). Magnification - 100x. Scale bar - 100 μm. The films were produced using the same coating formulations applied to the strawberries and were analyzed to represent the microstructure of the coating matrix.

Figure 1.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images of chitosan-based films prepared from coating solutions: (A) 1% chitosan (1% Cs), (B) 3% chitosan (3% Cs), (C) 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and (D) 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr). Magnification - 100x. Scale bar - 100 μm. The films were produced using the same coating formulations applied to the strawberries and were analyzed to represent the microstructure of the coating matrix.

Figure 2.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan-frankincense oil (1% Cs-Fr), and 3% chitosan-frankincense oil (3% Cs-Fr) coatings.

Figure 2.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan-frankincense oil (1% Cs-Fr), and 3% chitosan-frankincense oil (3% Cs-Fr) coatings.

Figure 3.

Antibacterial activity of dried chitosan and chitosan–frankincense oil coatings against bacteria E. coli. Coatings of 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) were applied to microplate wells and dried before the addition of bacterial culture. The number of bacterial colony-forming units (CFU/mL) in the liquid medium was determined after 24 h and 48 h of incubation. Wells without coating served as the control. The data are the means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments according to one-way ANOVA followed by LSD test (p < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Antibacterial activity of dried chitosan and chitosan–frankincense oil coatings against bacteria E. coli. Coatings of 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) were applied to microplate wells and dried before the addition of bacterial culture. The number of bacterial colony-forming units (CFU/mL) in the liquid medium was determined after 24 h and 48 h of incubation. Wells without coating served as the control. The data are the means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments according to one-way ANOVA followed by LSD test (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

The number of bacteria (CFU/mL) at the end of the experiments (8 days) on strawberries. The initial number of bacteria is shown as a dashed line. Strawberries were coated with 1% chitosan (1%Cs), 3% chitosan (3%Cs), 1% chitosan-frankincense oil (1%Cs/Fr), and 3% chitosan-frankincense oil (3%Cs/Fr). Control strawberries were uncoated. Data are means + standard deviations. Different letters indicate significant (one-way ANOVA, LSD, p<0.05) differences between means.

Figure 4.

The number of bacteria (CFU/mL) at the end of the experiments (8 days) on strawberries. The initial number of bacteria is shown as a dashed line. Strawberries were coated with 1% chitosan (1%Cs), 3% chitosan (3%Cs), 1% chitosan-frankincense oil (1%Cs/Fr), and 3% chitosan-frankincense oil (3%Cs/Fr). Control strawberries were uncoated. Data are means + standard deviations. Different letters indicate significant (one-way ANOVA, LSD, p<0.05) differences between means.

Table 1.

Moisture content of strawberries on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8. Strawberries had 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) coatings or were uncoated. The data are the means of three replicates.

Table 1.

Moisture content of strawberries on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8. Strawberries had 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) coatings or were uncoated. The data are the means of three replicates.

| |

Moisture Content (%) |

| Day |

1%Cs |

1%Cs-Fr |

3%Cs |

3%Cs-Fr |

Uncoated |

| 0 |

91.06 ± 0.21 |

90.75 ± 0.34 |

90.17± 0.67 |

89.44± 0.93 |

90.33± 0.61 |

| 2 |

91.59± 0.69 |

88.78± 0.10 |

90.87± 0.73 |

91.07± 1.10 |

90.77± 0.78 |

| 4 |

90.96± 2.87 |

91.37± 3.35 |

90.51± 0.18 |

91.53± 1.48 |

91.36± 0.39 |

| 6 |

91.25± 1.39 |

94.64± 0.66 |

90.37± 2.05 |

91.08± 0.84 |

91.1± 1.44 |

| 8 |

89.71± 1.81 |

90.69± 1.17 |

90.72± 1.02 |

91.1± 1.81 |

90.25± 1.05 |

Table 2.

Change of pH of strawberries on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8. Strawberries had 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) coatings or were uncoated. The data are the means of three replicates.

Table 2.

Change of pH of strawberries on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8. Strawberries had 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) coatings or were uncoated. The data are the means of three replicates.

| |

pH |

| Day |

1%Cs |

1%Cs-Fr |

3%Cs |

3%Cs-Fr |

Uncoated |

| 0 |

3.28±0.01 |

3.3±0.02 |

3.29±0.01 |

3.28±0.01 |

3.26±0.02 |

| 2 |

3.31±0.10 |

3.45±0.14 |

3.64±0.18 |

3.60±0.19 |

3.20±0.16 |

| 4 |

3.56±0.30 |

3.97±0.33 |

3.69±0.34 |

4.09±0.39 |

3.09±0.31 |

| 6 |

3.61±0.28 |

3.78±0.26 |

3.59±0.30 |

4.15±0.29 |

4.20±0.30 |

| 8 |

3.45±0.11 |

3.63±0.30 |

3.44±0.15 |

3.66±0.28 |

3.49±0.13 |

Table 3.

Total Soluble Solid (TSS) in (Birx%) of strawberries on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8. Strawberries had 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) coatings or were uncoated. The data are the means of three replicates.

Table 3.

Total Soluble Solid (TSS) in (Birx%) of strawberries on days 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8. Strawberries had 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) coatings or were uncoated. The data are the means of three replicates.

| |

Total Soluble Solids (Birx%) |

| Day |

1%Cs |

1%Cs-Fr |

3%Cs |

3%Cs-Fr |

Uncoated |

| 0 |

8.01±0.51 |

7.0±0.49 |

7.87±0.31 |

6.90±0.44 |

7.24±0.39 |

| 2 |

10.32±1.98 |

8.49±1.34 |

8.24±1.35 |

6.51±2.21 |

8.52±1.45 |

| 4 |

7.78±0.81 |

7.81±0.78 |

9.02±1.22 |

8.03±1.03 |

6.71±1.90 |

| 6 |

5.77±0.89 |

6.82±0.82 |

6.89±0.58 |

7.03±0.91 |

5.89±0.66 |

| 8 |

6.21±1.03 |

6.42±0.92 |

7.92±0.97 |

5.63±1.18 |

5.71±0.96 |

Table 4.

Color measurements presented by the Hue angle for strawberries. Strawberries had 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) coatings or were uncoated. The data are the means of five replicates.

Table 4.

Color measurements presented by the Hue angle for strawberries. Strawberries had 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) coatings or were uncoated. The data are the means of five replicates.

| |

Hue Angle (in degrees) |

| Day |

1%Cs |

1%Cs-Fr |

3%Cs |

3%Cs-Fr |

Uncoated |

| 0 |

27.37±5.33 |

33.62±6.01 |

28.42±4.72 |

28.26±2.45 |

28.12±2.45 |

| 2 |

39.08±9.56 |

30.58±4.08 |

40.56±17.54 |

38.16±5.27 |

33.45±8.43 |

| 4 |

39.14±8.31 |

31.76±5.97 |

37.63±7.21 |

39.05±9.99 |

28.09±5.73 |

| 6 |

30.70±6.12 |

45.37±15.18 |

39.95±11.15 |

39.35±12.93 |

31.89±6.45 |

| 8 |

36.92±6.47 |

38.05±8.06 |

48.97±19.41 |

38.57±8.74 |

28.84±5.86 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Table 5.

The hardness of strawberries at 2,4,6, and 8 days. Strawberries had 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) coatings or were uncoated. The data are the means of five replicates.

Table 5.

The hardness of strawberries at 2,4,6, and 8 days. Strawberries had 1% chitosan (1% Cs), 3% chitosan (3% Cs), 1% chitosan with frankincense oil (1% Cs–Fr), and 3% chitosan with frankincense oil (3% Cs–Fr) coatings or were uncoated. The data are the means of five replicates.

| |

Hardness (N) |

| Day |

1%Cs |

1%Cs-Fr |

3%Cs |

3%Cs-Fr |

Uncoated |

| 2 |

3.56±1.10 |

2.73±1.17 |

4.44±1.76 |

6.02±2.89 |

4.28±1.80 |

| 4 |

2.45±1.68 |

3.52±1.34 |

3.05±1.48 |

4.47±2.91 |

5.59±2.22 |

| 6 |

3.41±1.87 |

3.31±1.38 |

2.02±1.78 |

2.50±1.72 |

2.70±1.46 |

| 8 |

4.17±1.95 |

3.28±1.37 |

5.07±2.15 |

6.50±2.55 |

5.01±1.97 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).