1. Introduction

Financial burden remains one of the major challenges faced by the informal caregivers of older adults providing care within home or institutional settings [

1,

2]. The financial burden includes both direct and indirect costs of caregiving including medical expenses, caregiving time, roles and responsibilities [

3,

4]. Beyond the high costs of medical care, caregivers also contend with additional expenses such as housing and transportation, which together can exceed

$7,000 annually [

5]. On average, family caregivers spend approximately 26% of their income on caregiving-related costs, and about half of them use their own funds to cover household expenses associated with caregiving [

6,

7,

8]. This financial strain is especially pronounced among informal caregivers who provide unpaid care. For instance, more than half (58%) of informal caregivers’ report dissatisfaction with their household income, and nearly a third (30%) struggle to meet their families’ basic needs [

9].

In 2020, nearly half of caregivers in California reported experiencing financial stress [

3,

4]. Such strain often forces caregivers to reduce or stop saving, accumulate debt, delay bill payments, and cut back on essentials such as food [

10]. Many caregivers face difficulties accessing financial assistance due to poor financial literacy or lack of support and guidance from the providers [

3,

7,

11]. Informal caregivers tend to face multiple financial hardships, sacrifice their careers, experience employment limitations, downsize their businesses, and compromise on their family roles [

11,

12]. These financial pressures contribute significantly towards informal caregivers’ physical and mental health outcomes [

3,

13]. Evidence suggests that higher financial difficulty scores are associated with greater caregiver distress, poorer self-rated health, and lower quality of life [

9,

11,

14].

Demographic disparities also complicate these hardships. Studies show that financial stress is more pronounced among male caregivers, caregivers in low socioeconomic settings, and young adult caregivers [

15,

16,

17]. Young adult caregivers report greater psychological distress, poorer health outcomes, and heightened financial strain compared to their peers [

16]. About one-third of caregivers are aged 65 or older, with caregiving demands increasing alongside age, thereby elevating health risks [

12]. High-hour caregivers average 51.8 years, and notable gender disparities persist; 25.4% of women versus 18.9% of men provide care [

18]. Additionally, 65% of care recipients are female (mean age 69.4), and women caregivers spend up to 50% more time providing care than men [

12].

Prior research has consistently documented the financial strain and psychosocial burden of caregiving, few studies have investigated how gender moderates the relationship among psychosocial distress, social support, and financial well-being especially among informal caregivers of older adults. Few studies established the role of social support in enhancing the financial well-being [

19], limited attention has been given to whether these effects differ by gender. Addressing this gap is crucial, as gender-specific pathways may influence how caregivers experience and manage financial stress. Accordingly, this study seeks to determine whether gender moderates the associations between psychosocial distress, social support, and financial well-being among informal caregivers, offering insights for more targeted and gender-responsive interventions.

2. Methods

1.1. Purpose

This study aims to investigate whether gender moderates the relationships between 1) psychosocial distress and financial well-being, and 2) social support and financial well-being.

2.1. Study Design

A cross-sectional survey design was employed to examine the financial well-being of rural family caregivers in the United States. Data were collected using a structured, web-based questionnaire hosted on Qualtrics.

2.2. Setting and Sample

The study was conducted across twelve North Central rural states, including Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. A total of 533 caregivers completed the survey between December 2023 and March 2024.

2.3. Participant Eligibility

Eligible participants were 18 years or older and currently providing unpaid or informal care to an older adult aged 60 or above with a chronic illness or disability residing at home, in hospice, or within a residential care facility.

2.4. Recruitment Procedures

Participants were recruited through a combination of panel-based sampling and community outreach. Recruitment strategies included collaboration with a professional survey panel company, distribution of flyers at libraries and community centers, participation in local fairs, and postings on the social media pages of caregiving associations. The survey required approximately 15–20 minutes to complete.

2.5. Study Measures

2.5.1. Dependent Variable

Financial Well-Being. Perceived financial well- being was assessed using the abbreviated five-item version of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB) Financial Well-Being Scale (reference 1). This validated scale captures individuals’ perceptions of their financial security and control. Participants responded to five items: 1) Because of my money situation, I feel like I will never have the things I want in life; 2) I am just getting by financially; 3) I am concerned that the money I have or will save won’t last; 4) I have money left over at the end of the month; and 5) My finances control my life. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with negatively worded items (Items 1, 2, 3, and 5) reverse-coded. Total raw scores were then converted into a standardized financial well-being score ranging from 19 to 90, based on respondents’ age group (18–61 years or 62+ years) and the method of survey administration (self-administered or administered by someone else). Higher scores indicate greater financial well-being. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.805 in the current study.

2.5.2. Independent Variables

Social Support. Perceived social support was measured using the Oslo-3 Social Support Scale (OSSS-3), a brief, validated three-item instrument designed to assess the level of social support (reference 2). Total scores range from 3 to 14, with higher scores indicating stronger perceived social support. Participants were categorized into three groups based on their OSSS-3 scores: 3–8 (poor social support), 9–11 (moderate social support), and 12–14 (strong social support). The OSSS-3 has been widely used in research and has demonstrated acceptable reliability and construct validity (reference 2).

Psychosocial Distress. Participants’ psychosocial distress was assessed using five self-reported items: feeling stressed, anxious, depressed, lonely, and having no time for oneself. Each item was measured on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating the lowest level of distress and 10 indicating the highest. A total distress score was calculated by summing the responses across all five items, with higher scores indicating greater psychosocial distress. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.847 in the current study.

Gender. Participants were categorized into two gender groups: male and female. The dataset did not include individuals identifying as gender-fluid or non-binary.

2.5.3. Covariates

In addition to the variables described above, the study also collected demographic and background information, including caregivers’ age (18–64 years or 65+ years), race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White or non-White), education level (high school or less, some college, or college degree or higher), marital status (married/partnered, never married, or divorced/widowed/separated), and annual household income (less than $20,000; $20,000–$49,999; $50,000–$74,999; or ≥ $75,000). Participants were also asked whether they provided care for older adults (yes or no) and to rate their overall health (poor, fair, good, or very good).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize sample characteristics. Means and standard deviations were reported for continuous variables, while frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. An independent-samples t-test was conducted to examine differences in financial well-being by gender, and a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences in financial well-being across levels of social support. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the association between psychosocial distress and financial well-being. To explore whether the associations between psychosocial distress and financial well-being, as well as between social support and financial well-being, differed by gender, a linear regression model was conducted including two interaction terms: psychosocial distress × gender and social support × gender. All regression models controlled for age, race/ethnicity, education level, marital status, annual household income, caregiving status for older adults, and self-rated health. Multicollinearity was not a concern in the linear regression analysis, as the variance inflation factor (VIF) for all variables was less than 3. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 19.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX), with a p-value of less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Informed consent was embedded within the online Qualtrics survey, which participants completed prior to beginning the questionnaire. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, all surveys were coded numerically without personal identifiers. Data were securely stored on the Qualtrics platform and accessed only by the research team, following institutional ethical guidelines for data protection.

3. Results

A total of 589 caregivers participated in the study. Among them, 56 participants (9.51%) had missing data. Listwise deletion was employed to handle the missing data. As a result, data from 533 participants (90.49%) with complete responses were included in the final analysis.

Table 1 presents the sample characteristics of 533 caregivers. The majority (70.73%) were aged 18–64 years, while 29.27% were older adult caregivers (65 years and older). Approximately 45.97% of the sample were female caregivers, and the majority (88.56%) identified as non-Hispanic White. Educational attainment was relatively evenly distributed: 34.15% had a high school diploma or less, 34.15% had some college education, and 31.71% held a college degree or higher. More than half of the caregivers (56.29%) were married or partnered; 23.26% had never married, and 20.45% were divorced, widowed, or separated. In terms of annual household income, 17.82% reported earning less than

$20,000, 34.52% earned between

$20,000 and

$49,999, 21.58% between

$50,000 and

$74,999, and 26.08% reported incomes of

$75,000 or more. About 36.77% of caregivers provided care for older adults. Regarding self-rated health, 5.82% rated their health as poor, 24.95% as fair, 53.85% as good, and 15.38% as very good. Nearly half of caregivers (48.22%) reported low levels of perceived social support, 43.71% reported moderate support, and only 8.07% reported strong support. The average psychosocial distress score was 17.90 (range: 0–50), and the mean financial well-being score was 51.49 (range: 19–90).

As shown in

Table 2, male caregivers reported significantly higher financial well-being than female caregivers, with a mean difference of 2.54 points (males: 52.66; females: 50.12; p = 0.036). ANOVA results also indicated significant differences in financial well-being across levels of social support (p < 0.001;

Table 2). Post hoc analysis revealed that caregivers who reported strong and moderate social support had significantly higher financial well-being scores—11.80 points (p < 0.001) and 7.04 points (p < 0.001), respectively—compared to those with poor social support. Although caregivers who reported strong social support had 4.76 points higher financial well-being than those with moderate support, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.099). As expected, there was a moderate negative correlation between psychosocial distress and financial well-being (r = –0.491, p < 0.001), indicating that higher levels of distress were associated with lower financial well-being.

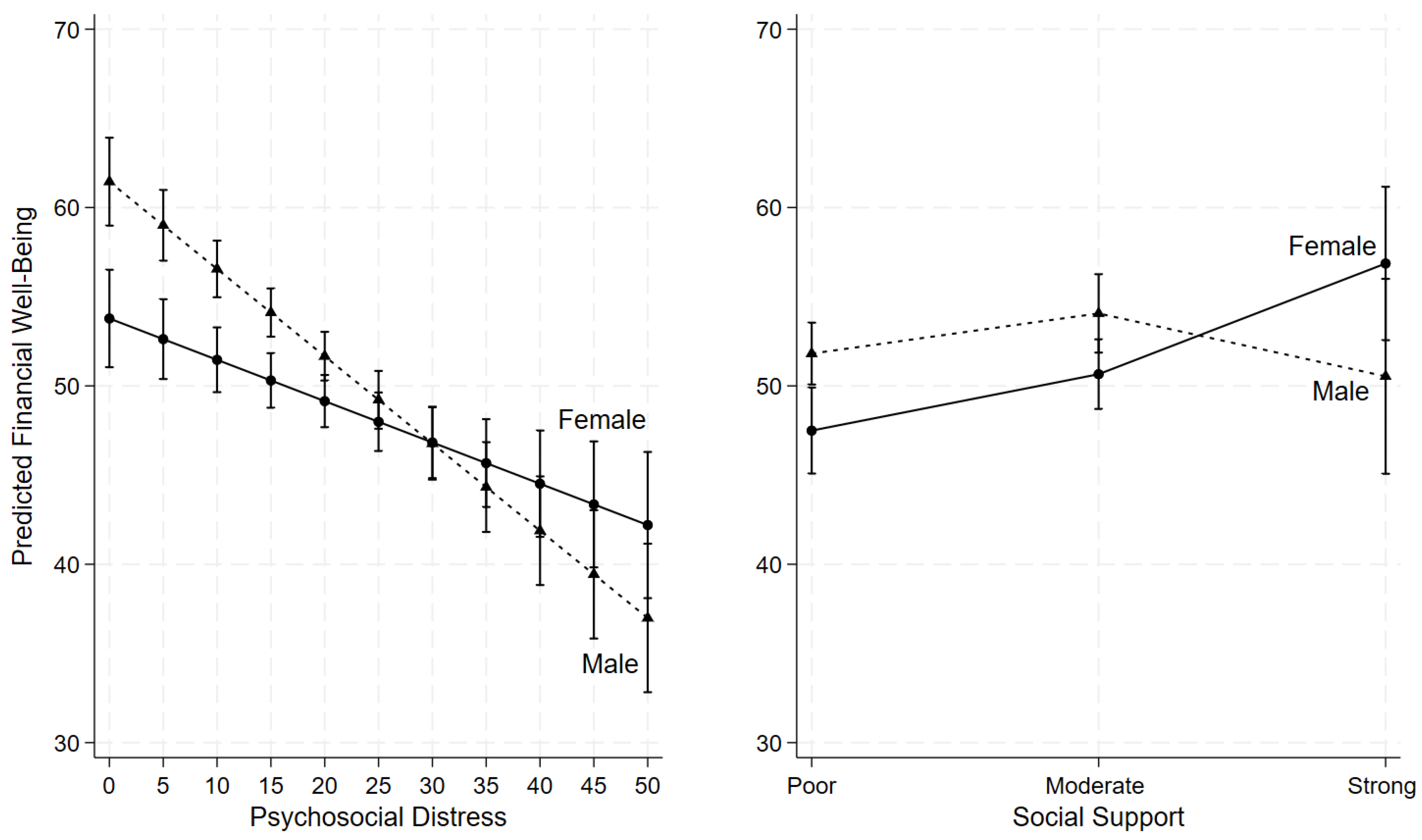

As shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 1, psychosocial distress was negatively associated with financial well-being, even after adjusting for demographic and other potential confounding variables. Moreover, the interaction term between psychosocial distress and gender was statistically significant (β = 0.26, p = 0.002;

Table 3) indicating that gender moderates the relationship between psychosocial distress and financial well-being. Specifically, as psychosocial distress increased, financial well-being declined more sharply among males than females (

Figure 1). At lower levels of psychosocial distress, males reported higher financial well-being compared to females; however, at higher levels of distress, males reported lower financial well-being than females (

Figure 1).

Regarding the relationship between social support and financial well-being, the interaction term between strong social support and gender was statistically significant (β = 10.64, p = 0.006;

Table 3), indicating that gender moderates this association. Among caregivers reporting poor or moderate social support, females reported lower financial well-being than males (

Figure 1). However, when females perceived strong social support, their financial well-being increased substantially, surpassing that of males with similarly strong social support, although the gender difference at this level was not statistically significant (

Figure 1).

Among the covariates, caregivers aged 65 years and older reported significantly better financial well-being compared to those aged 18–64 years (β = 7.78, p < 0.001;

Table 3). Higher annual household income was also associated with greater financial well-being: caregivers with

$50,000–

$74,999 had significantly higher scores than those earning less than

$20,000 (β = 3.56, p = 0.035), as did those with incomes of

$75,000 or more (β = 5.33, p = 0.002;

Table 3). In addition, caregivers who rated their health as very good reported better financial well-being compared to those with poor or fair self-rated health (β = 3.26, p = 0.048;

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study examined whether gender moderates the associations between psychosocial distress, social support, and financial well-being among caregivers. Post hoc analysis revealed that caregivers with strong and moderate social support reported significantly higher financial well-being scores—11.80 points (p < 0.001) and 7.04 points (p < 0.001), respectively compared to those with poor support. This may reflect the diverse forms of assistance, including financial help, provided by family, friends, and loved ones to those with stronger support networks. Consistent with previous findings, caregivers with limited social support are more likely to experience heightened financial stress [

19]. Therefore, caregivers of older adults require not only emotional and physical support but also financial assistance from significant others to offset treatment and out-of-pocket costs, which can enhance their well-being and caregiving capacity. Moreover, social support is associated with greater life satisfaction, improved emotional health, and reduced loneliness [

20,

21].

The findings showed a moderate negative correlation between psychosocial distress and financial well-being (r = –0.491, p < 0.001), meaning caregivers experiencing higher distress reported lower financial well-being. This highlights the importance of expanding financial support and implementing strategies to ease caregivers’ financial strain, which may in turn reduce psychosocial distress as they care for older adults with illness. Evidence from previous studies suggests that accessible financial counseling and targeted public health programs can help mitigate financial burden and improve psychological well-being [

22]. Notably, this challenge is especially acute among marginalized groups, including women, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic caregivers, individuals with low income or education, the uninsured, the unemployed, and those living in private or social housing [

23,

24]. These results emphasize the need to ensure equity in financial resources and support systems to address disparities and protect caregivers’ well-being.

The findings show that financial well-being declined more sharply among male caregivers as psychosocial distress increased. Although men reported higher financial well-being than women at lower levels of distress, this advantage diminished and eventually reversed at higher distress levels, with men reporting lower financial well-being than women. This pattern suggests that while men may start with greater financial resources or confidence, they appear to have fewer coping mechanisms or support systems to buffer the effects of rising distress. Women, by contrast, may benefit from stronger social networks that help sustain financial well-being under stress despite beginning from a lower baseline. Prior research supports this interpretation, showing that women tend to use a wider range of coping strategies than men—including self-distraction, emotional and instrumental support, and venting [

25]. Men, on the other hand, may be less likely to disclose distress or seek help, including financial assistance, partly due to stigma surrounding help-seeking behaviors [

26]. These insights underscore the importance of gender-responsive interventions: financial literacy and stress management programs tailored to men could bolster resilience when distress escalates, while sustained investment in social support systems remains vital for women.

The results suggests that gender differences in financial well-being among caregivers are closely tied to the level of social support. When social support was poor or moderate, women reported lower financial well-being than men, reflecting the additional financial vulnerabilities that female caregivers often face. However, when women perceived strong social support, their financial well-being rose significantly, surpassing that of men with equally strong support, although this difference was not statistically significant. This pattern suggests that women may draw greater benefit from robust support networks, which can provide both emotional encouragement and practical assistance that directly ease financial strain. Men, by contrast, appear to gain less from increased support, possibly reflecting differences in how social resources are accessed or used. Supporting evidence shows women are more likely than men to seek help from close ties 54% vs. 42% from mothers, 54% vs. 38% from friends, and 44% vs. 26% from other relatives [

27]. These findings highlight the critical importance of strengthening social support systems for caregivers, particularly for women, as a means of reducing financial stress and narrowing gender disparities in caregiver well-being.

Caregivers aged 65 and older reported significantly higher financial well-being than those aged 18–64, plausibly reflecting accumulated savings, retirement income, and fewer ongoing obligations. Younger caregivers, by contrast, often juggle employment, childcare, and debt, heightening financial strain. Self-rated health also mattered as respondents who described their health as very good had higher financial well-being than those with poor or fair health (β = 3.26, p = 0.048), underscoring the reciprocal link between health and finances. Poor health can reduce earning capacity and increase medical expenses, deepening hardship, whereas greater financial security may facilitate access to care and healthier behaviors. These patterns align with evidence that ill health drives poverty through multiple mechanisms across the life course and generations (O’Donnell, 2024).

Limitations

The cross-sectional design used prevents causal inference between psychosocial distress, social support, and financial well-being. Longitudinal research is needed to establish temporal relationships and explore potential bidirectional effects. The reliance on self-reported data may introduce recall and social desirability biases, particularly in sensitive areas such as financial well-being and emotional distress. Third, the sample was drawn primarily from rural caregivers and may not be generalizable to urban populations or caregivers from different cultural or socioeconomic contexts. Additionally, gender was categorized as binary (male/female), limiting understanding of diverse gender identities and caregiving experiences. Future studies should incorporate more inclusive measures, larger and more diverse samples, and mixed-method approaches to deepen insights into the gendered and contextual dimensions of caregiver well-being.

5. Implications and Conclusion

This study highlights the critical role of psychosocial distress, social support, and gender in shaping the financial well-being of rural informal caregivers. The findings suggest that strong social networks can buffer financial strain, particularly for women, while male caregivers experience sharper financial declines as distress increases, emphasizing the need for gender-responsive interventions that combine financial literacy, stress management, and peer support. Enhancing access to community-based caregiver resources, social safety nets, and financial relief programs can reduce inequities and improve both caregiver and patient outcomes. Moreover, addressing caregivers’ emotional and economic needs as part of holistic health care is essential to sustaining long-term caregiving capacity. Overall, the results underscore that improving caregivers’ financial well-being requires integrated approaches that strengthen social support systems, reduce psychosocial distress, and promote equity across gender and socioeconomic lines.

Funding

This study did not receive any external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Purdue University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All supporting data are contained within the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the participants and to the scholars whose works were referenced in this study. Special thanks to the informal family caregivers who generously shared their experiences and insights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hailu GN, Abdelkader M, Meles HA, Teklu T. Understanding the support needs and challenges faced by family caregivers in the care of their older adults at home: A qualitative study. Clin Interv Aging. 2024;19:481–490. [CrossRef]

- Honda A, Nishida T, Ono M, Tsukigi T, Honda S. Impact of financial burden on family caregivers of older adults using long-term care insurance services. SAGE Open Nurs. 2025;11:23779608251383386. [CrossRef]

- Tan S, Kudaravalli S, Kietzman KG. Who is caring for the caregivers? The financial, physical, and mental health costs of caregiving in California [policy brief]. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. Published November 29, 2021. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/who-is-caring-for-the-caregivers.

- Tahami Monfared AA, Hummel N, Chandak A, Khachatryan A, Zhang Q. Assessing out-of-pocket expenses and indirect costs for the Alzheimer disease continuum in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2023;29(9). [CrossRef]

- Kerr N. Family caregivers spend more than $7,200 a year on out-of-pocket costs: AARP study finds family members feeling financial strain from contributing to loved ones’ care. AARP. Published June 29, 2021. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/financial-legal/info-2021/family-caregiving-costs.html.

- AARP Research. AARP research insights on caregiving. AARP. Published March 27, 2025. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.aarp.org/research/topics/care/info-2023/family-caregiving-insights.html.

- AARP; National Alliance for Caregiving. New report reveals crisis point for America’s 63 million family caregivers: 1 in 4 Americans provide ongoing, complex care; report finds they endure poor health, financial strain, and isolation. AARP Press Room. Published July 23, 2025. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.aarp.org/caregivingintheus2025.

- AARP. AARP research shows family caregivers face significant financial strain, spend on average $7,242 each year: AARP launches national campaign urging more support for family caregivers, passage of bipartisan Credit for Caring Act. AARP. Published 2021. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://states.aarp.org/idaho/aarp-research-shows-family-caregivers-face-significant-financial-strain.

- Wagle S, Yang S, Osei EA, Katare B, Lalani N. Caregiving intensity, duration, and subjective financial well-being among rural informal caregivers of older adults with chronic illnesses or disabilities. Healthcare. 2024;12(22):2260. [CrossRef]

- Reinhard S, Feinberg L. Caregiver health and well-being, and financial strain. Innov Aging. 2020;4(Suppl 1):681–682. [CrossRef]

- Lalani N, Osei EA, Yang S, et al. Financial health and well-being of rural female caregivers of older adults with chronic illnesses. BMC Geriatr. 2025;25:239. [CrossRef]

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiver statistics: Demographics. Family Caregiver Alliance, National Center on Caregiving; 2016. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.caregiver.org/resource/caregiver-statistics-demographics/.

- Liu Y, Hughes MC, Wang H. Financial strain, health behaviors, and psychological well-being of family caregivers of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. PEC Innov. 2024;4:100290. [CrossRef]

- Poco LC, Andres EB, Balasubramanian I, Malhotra C. Financial difficulties and well-being among caregivers of persons with severe dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2025;29(7):1338–1347. [CrossRef]

- Koomson I, Lenzen S, Afoakwah C. Informal care and financial stress: Longitudinal evidence from Australia. Stress Health. 2024;40(4):e3393. [CrossRef]

- Darabos K, Faust H. Assessing health, psychological distress, and financial well-being in informal young adult caregivers compared to matched young adult non-caregivers. Psychol Health Med. 2023;28(8):2249–2260. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Anuarbe M, Kohli P. Understanding male caregivers' emotional, financial, and physical burden in the United States. Healthcare. 2019;7(2):72. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Caregiving for family and friends—A public health issue. National Association of Chronic Disease Directors; 2018. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/caregiving/index.htm.

- Åslund C, Larm P, Starrin B, Nilsson KW. The buffering effect of tangible social support on financial stress: Influence on psychological well-being and psychosomatic symptoms in a large sample of the adult general population. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13(1):85. [CrossRef]

- Xin Z, Guo Y, Zheng J, Xie P. When giving social support is beneficial for well-being? Acta Psychol. 2025;255:104911. [CrossRef]

- Egaña-Marcos E, Collantes E, Díez-Solinska A, Azkona G. The influence of loneliness, social support, and income on mental well-being. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2025;15(5):70. [CrossRef]

- Ryu S, Fan L. The relationship between financial worries and psychological distress among U.S. adults. J Fam Econ Issues. 2023;44(1):16–33. [CrossRef]

- Jackson SE, Cox S, Holmes J, Angus C, Robson D, Brose L, Brown J. Paying the price: Financial hardship and its association with psychological distress among different population groups in the midst of Great Britain’s cost-of-living crisis. Soc Sci Med. 2025;364:117561. [CrossRef]

- Nasir A, Javed U, Hagan K, Chang R, Kundi H, Amin Z, Butt S, Al-Kindi S, Javed Z. Social determinants of financial stress and association with psychological distress among young adults 18–26 years in the United States. Front Public Health. 2025;12:1485513. [CrossRef]

- Graves BS, Hall ME, Dias-Karch C, Haischer MH, Apter C. Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255634. [CrossRef]

- Smith GD, Hebdon M. Mental health help-seeking behaviour in men. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79(1):e1–e3. [CrossRef]

- Goddard I, Parker K. Men, women and social connections. Pew Research Center; Published January 16, 2025. Accessed November 11, 2025. https://pewrsr.ch/42hWLuO.

- O'Donnell O. Health and health system effects on poverty: A narrative review of global evidence. Health Policy. 2024;142:105018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).