Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

14 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

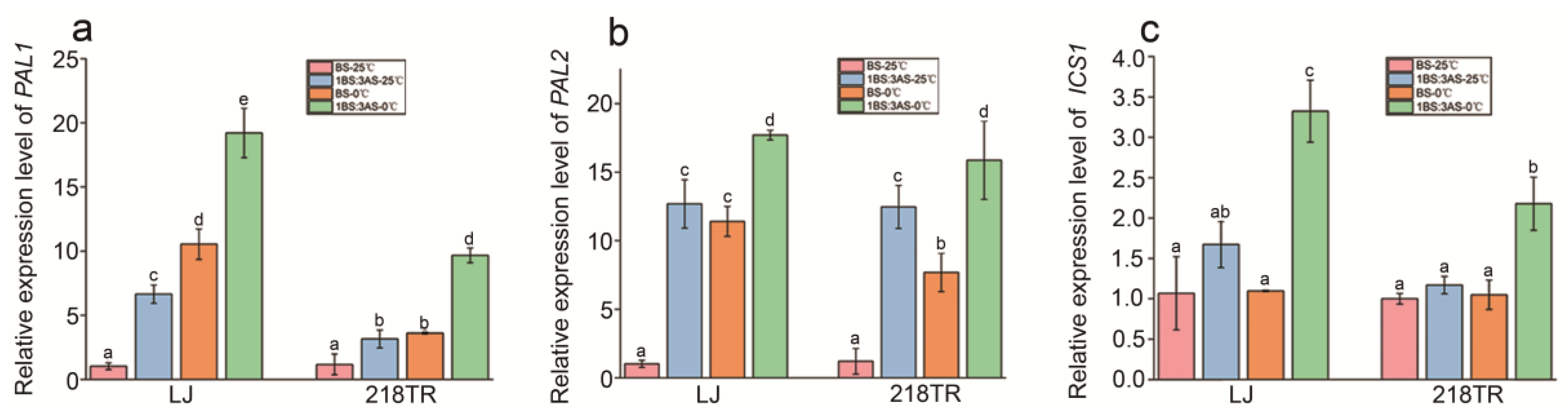

Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), a perennial leguminous herb, exhibits robust cold and saline-alkali tolerance. In this study, two alfalfa cultivars, LJ and 218TR, were treated with saline-alkali stress, cold stress, and combined saline-alkali-cold stress, and phenotype, physiology, key metabolite and stress-responsive genes were analyzed. The results showed malondialdehyde, soluble sugar, proline content, and the activities of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase initially increased under individual stresses but declined after combined stress. The maximum photochemical efficiency of photosystem II and chlorophyll content declined under individual and combined stresses. The staining of leaves revealed that combined stress induced significantly higher cell mortality and accumulation of superoxide anion compared to individual stresses. LJ exhibited superior resistant to saline-alkali, cold, and combined stress compared to 218TR. Metabolite analysis showed salicylic acid (SA) in two alfalfa was the most responsive metabolite to combined stress. The isochorismate synthase (ICS) and PAL as critical genes for SA biosynthesis were up-regulated in expression under single or combined stress, and promoted SA accumulation, thereby improving alfalfa resilience to combined saline-alkali-cold stress. This study elucidates the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying alfalfa’s response to combined saline-alkali and cold stress, providing a theoretical basis for breeding stress-tolerant cultivars.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phenotype of Alfalfa to Saline-Alkali and Cold Stress

2.2. Physiological Characteristics of Alfalfa to Saline-Alkali and Cold Stress

2.3. Chlorophyll Fluorescence of Alfalfa to Saline-Alkali and Cold Stress

2.4. NBT Staining of Alfalfa to Saline-Alkali and Cold Stress

2.5. Metabolite Analysis of Alfalfa to Saline-Alkali and Cold Stress

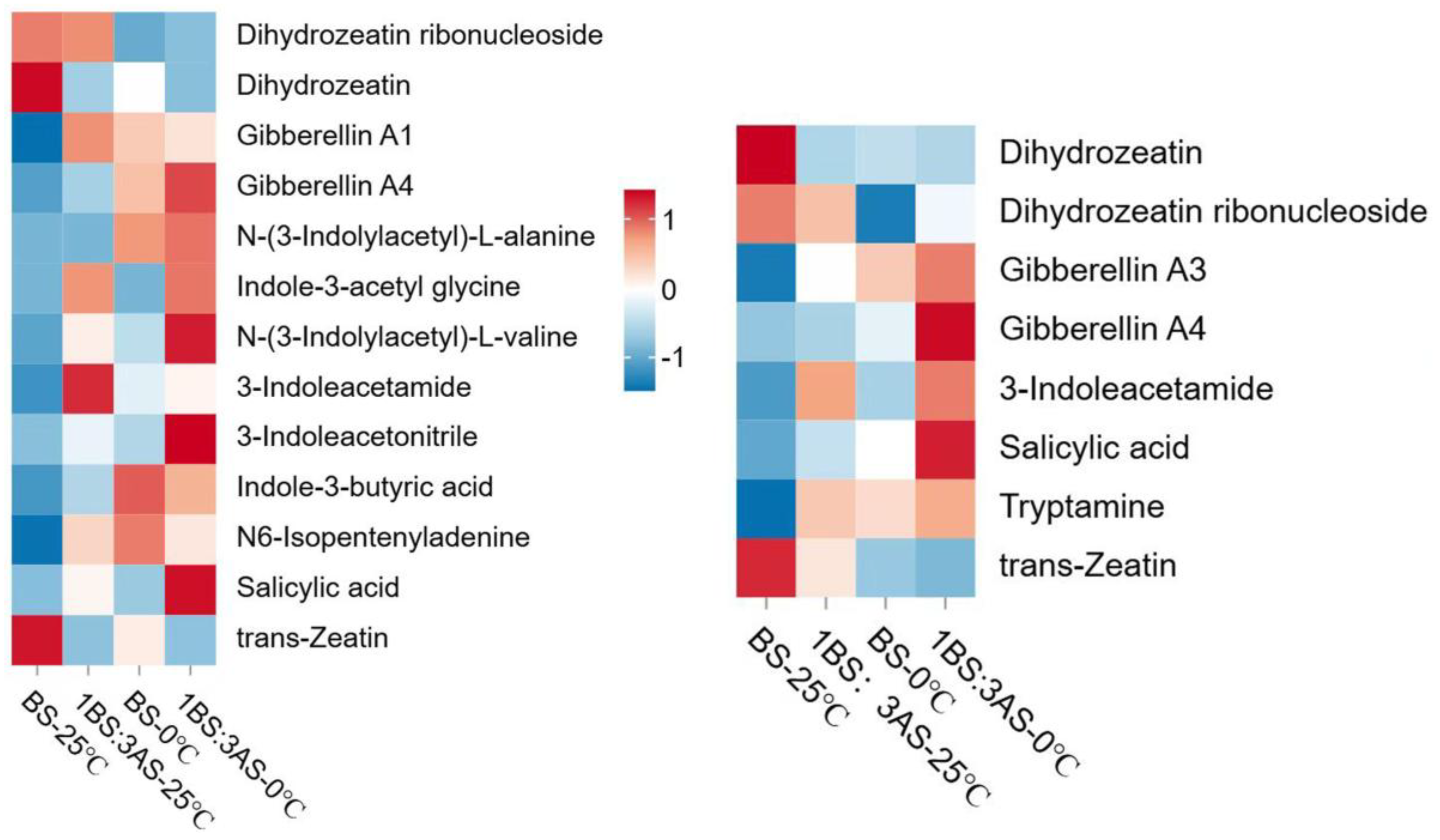

2.6. Heatmap of Metabolite Expression Levels to Saline-Alkali and Cold Stress

2.7. Expression Analysis of Key Genes in the SA Biosynthesis Pathway

3. Discussion

3.1. Physiological Responses of Alfalfa to Saline-Alkali and Cold Stress

3.2. Metabolite Responses of Alfalfa to Saline-Alkali and Cold Stress

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Treatment

4.2. The Determination of Phenotype, Physiological Indices and Metabolites

4.3. Data Processing and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, X.L.; Qin, C . Effects of different amendments on improvement of saline-alkali soil and cotton growth in Xinjiang. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2022, 38, 91–96.

- Zhao, T.J.; Gai, J.Y. Progress and discussion on breeding of super-high-yielding soybeans. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2006, 1, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, H.Y.; Wang, D.W. Innovation trends in soybean breeding industry. J. Plant Genet. Resour. 2018, 19, 464–467. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, T.; Zhong, X.B. Current status and revitalization strategies of soybean industry in China. Soybean Sci. 2018, 37, 458–463. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, L.X. Analysis and evaluation of soil salinization characteristics under different land use types in Daqing region. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2011, 25, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, C.X.; Zhang, Y.M. Response of anatomical structure of Medicago sativa to NaHCO3 saline-alkali stress. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2014, 23, 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hai, X.; Liu, J.H. Effects of salt stress on Na+, K+ absorption and ion accumulation in oat seedlings. J. Triticeae Crops 2019, 39, 613–620. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, F.; Zhang, Q.G. Formation and classification of saline-alkali land in Tongliao City. J. Inn. Mong. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2009, 24, 409–413. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; Qiu, S.W. Background of Regional Eco-Environment in Da’an Sodic Land Experiment Station of China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Guo, Y.J. Research on improvement technology of soda saline-alkali soil in Northeast China. Agric. Technol. 2019, 39, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.F.; Ma, J.Y. Study on the relationship between photosynthetic fluorescence parameters and quality of Medicago sativa in saline-alkali soil. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Puertas, M.C.; Rodríguez-Serrano, M. Cadmium-induced subcellular accumulation of O2− and H2O2 in pea leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2004, 27, 1122–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Miao, N.S. Changes in chlorophyll content and antioxidant enzyme activities of diploid potato under salt stress. Crops 2014, 5, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.J.; Hu, T. Physiological effects of soda alkali stress on perennial ryegrass. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2012, 21, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Ye, L. Effects of saline-alkali stress on growth, quality, and photosynthetic characteristics of Medicago sativa. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2017, 45, 176–180. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.C.; Shi, K. Response of Medicago sativa cv. Zhongmu No.1 seedlings to mixed saline-alkali stress. Chin. J. Grassl. 2024, 46, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.C.; Hu, X.L. Application of chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics in plant stress physiology research. Nonwood For. Res. 2002, 4, 14–18, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.Z.; Wu, J.J. Research progress on chlorophyll fluorescence and its application in drought stress monitoring. Spectrosc. Spectr. Anal. 2017, 37, 2780–2787. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.R.; Xue, L. Research progress on the effects of salt stress on plant chlorophyll fluorescence. Ecol. Sci. 2019, 38, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, L.; Li, S. Leaf morphology and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics of mulberry seedlings under waterlogging stress. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.Z.; Yu, S.L.N. Effects of salt stress on photosynthetic physiology and chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics of grape (Red Globe) seedlings. Agric. Res. Arid Areas 2011, 29, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.L.; Li, H. Identification of salt tolerance during seed germination and seedling stage of five Poaceae forage species. Seed 2016, 35, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.X.; Bai, T.Y. Effects of salt stress on growth and photosynthetic fluorescence characteristics of two Artocarpus species seedlings. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2019, 52, 2140–2150. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Lu, Y.S. Effects of salt and low-temperature dual stress on growth and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of melon seedlings. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 2017, 23, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiztugay, E.; Sekmen, A.H. Elucidation of physiological and biochemical mechanisms of an endemic halophyte Centaurea tuzgoluensis under salt stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 49, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malenčić, D.; Kiprovski, B. Changes in antioxidant systems in soybean as affected by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (Lib.) de Bary. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, C. Model analysing the antioxidant responses of leaves and roots of switchgrass to NaCl-salinity stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 58, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.Z.; Han, B. Changes of malondialdehyde content in alfalfa under different salt stress concentrations. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2009, 37, 1905–1911. [Google Scholar]

- Deinlein, U.; Stephan, A.B. Plant salt-tolerance mechanisms. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.C.; Zhang, Z.M. Effects of drought and salt stress on osmotic adjustment and antioxidant enzyme activities in peanut. Acta Agric. Boreali-Sin. 2018, 33, 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, S. Heat and chilling induced disruption of redox homeostasis and its regulation by hydrogen peroxide in germinating rice seeds (Oryza sativa L., cultivar Ratna). Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2013, 19, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Liu, J. NUCLEAR TRANSPORT FACTOR 2-LIKE improves drought tolerance by modulating leaf water loss in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Plant J. 2022, 112, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Bao, G.Z. Physiological responses of ryegrass seedlings under freeze-thaw and NaHCO3 composite stress. J. Jilin Univ. Sci. Ed. 2017, 55, 451–457. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.N.; Yang, Z.M. Effects of high temperature and drought stress on antioxidant metabolism in creeping bentgrass. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2014, 45, 489–494. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.L.; Xuan, C.X. Effects of drought stress and rewatering on endogenous hormone content in pea roots. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2009, 17, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, I.M.; Clarke, S.M. Salicylate accumulation inhibits growth at chilling temperature in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 1040–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, H. ABNORMAL INFLORESCENCE MERISTEM1 functions in salicylic acid biosynthesis to maintain proper reactive oxygen species levels for root meristem activity in rice. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 560–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Ding, Y. Stories of salicylic acid: A plant defense hormone. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shine, M.B.; Yang, J. Cooperative functioning between phenylalanine ammonia lyase and isochorismate synthase activities contributes to salicylic acid biosynthesis in soybean. New Phytol. 2016, 212, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, D.; Nakajima, N. The phenylalanine pathway is the main route of salicylic acid biosynthesis in tobacco mosaic virus-infected tobacco leaves. Plant Biotechnol. 2006, 23, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, J.; Shainberg, I. Reclamation of salt-affected soils. In Agricultural Drainage; 1999; 38, 659–691.

- Guo, F.X.; Zhang, M.X. Relation of several antioxidant enzymes to rapid freezing resistance in suspension cultured cells from alpine Chorispora bungeana. Cryobiology 2006, 52, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Fu, X.Z. Spermine pretreatment confers dehydration tolerance of citrus in vitro plants via modulation of antioxidative capacity and stomatal response. Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F.; Wu, X.D. Experimental design for determination of malondialdehyde content in plants. Tianjin Agric. Sci. 2016, 22, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Wan, C. The characteristics of Na+, K+ and free proline distribution in several drought-resistant plants of the Alxa Desert, China. J. Arid Environ. 2004, 56, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Y.; Zhang, C.Q. Rapid determination method of chlorophyll content in maize. J. Maize Sci. 2008, 2, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.Y.; Wang, H.H. Improvement of soluble sugar content determination (anthrone method) experiment. Lab. Sci. 2013, 16, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahám, E.; Hourton-Cabassa, C.; Erdei, L.; Szabados, L. Methods for determination of proline in plants. Plant stress tolerance: Methods and protocols. 2010, 639, 317–331. [Google Scholar]

- Solekha, R.; Susanto, F.A. Phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) contributes to the resistance of black rice against Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 359–365; Correction to J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 102, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacyn Baker, C.; Mock, N.M. An improved method for monitoring cell death in cell suspension and leaf disc assays using Evans blue. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1994, 39, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control group | Total substance count detection | The number of upregulated substances | The number of downregulated substances |

|---|---|---|---|

| LJ-BS-25℃ group vs LJ-1BS:3AS-25℃ group | 49 | 18 | 31 |

| LJ-BS-25℃ group vs LJ-BS-0℃ group | 49 | 27 | 22 |

| LJ-1BS:3AS-25℃ group vs LJ-1BS:3AS-0℃ group | 49 | 30 | 19 |

| LJ-BS-0℃ group vs LJ-1BS:3AS-0℃ group | 49 | 33 | 16 |

| 218TR-BS-25℃ group vs 218TR-1BS:3AS-25℃ group | 49 | 14 | 35 |

| 218TR-BS-25℃ group vs 218TR-BS-0℃ group | 49 | 20 | 29 |

| 218TR-1BS:3AS-25℃ group vs 218TR-1BS:3AS-0℃ group | 49 | 36 | 13 |

| 218TR-BS-0℃ group vs 218TR-1BS:3AS-0℃ group | 49 | 34 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).