1. Introduction

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is currently experiencing one of the most ambitious changes in its history, which is carried out within the context of the Vision 2030, which is aimed at diversifying the economy beyond its traditional oil-dependent economy and switching to knowledge-based and technology-driven industries (Brika et al., 2025; Moshashai et al., 2018). One key element of this change is the fast evolution of financial technology or fintech, which has emerged as a driver of innovation, investment, and sustainable growth in the Kingdom has been growing rapidly in recent years, which is facilitated by government-led reforms, the emergence of a tech-oriented population, and targeted investments by local and foreign companies (Albarrak & Alokley, 2021; Khan & Alhadi, 2022). This growth is justified by the fact that the Saudi Central Bank notes that the list of licensed fintech companies has grown not only rapidly in 2019 (only 20 companies were licensed) but also in 2023, there are more than 150 registered companies, which is a sign of the pace of market expansion, as well as the willingness of the Kingdom to become a regional center (SAMA, 2023). In this regard, the most significant tool highlighted in the existing literature is the rise of artificial intelligence, which has become a key driver of change in transforming the delivery and consumption of financial services having a direct impact on the aspects of inclusion, efficiency, and trust (DV, 2025; Lehner et al., 2022). Among the most significant highlighted AI tools, robo-advisory services offer computer-based financial planning and investment advice, which makes professional-level financial advice affordable to retail investors who would not otherwise afford it (Yi et al., 2023) while the accuracy and inclusiveness of lending decisions can be improved through AI-based credit scoring systems, which utilizes alternative data in addition to traditional credit history, providing new opportunities to people and small businesses (Hussain et al., 2024). AI-powered fraud detection systems enhance the integrity and security of financial transactions, which is essential in establishing a trust among consumers who might be reluctant to use digital finance (Nweze et al., 2024). Individualized banking services use AI to provide personalized services that address the preferences of customers, enhancing the user experience and expanding access to customers with unique financial requirements (Baffour Gyau et al., 2024). All of these innovations have the potential to close financial access gaps, increase the number of people who engage in the formal economy, and directly correspond to the goal of Saudi Arabia to position itself as a financial innovation hub in the region.

In spite of the fact that AI-powered financial services are commonly referred to as game-changers, there is a lack of evidence on their actual impact on the financial access in Saudi Arabia. Although international research emphasizes the effectiveness and cost-saving advantages of AI in the fintech sector (Albarrak & Alokley, 2021; Khan & Alhadi, 2022; Yi et al., 2023), much less is devoted to how these technologies allow disadvantaged populations to gain power or how they can be included in the Saudi fintech industry. Access to finance is also a critical issue, with some groups of people, including women entrepreneurs, low-income earners, and small business owners, still facing challenges in accessing reliable, affordable, and suitable financial services. Even in the situation when AI-based systems are implemented, there is a concern regarding their fairness, transparency, and accessibility (Onabowale, 2025; Sarioguz et al., 2024). An example is that robo-advisory tools can offer cheap advice, but they also need digital literacy, which is not distributed uniformly across the population. AI-based credit scoring systems could expand credit, although they require a lot of data to work, which has privacy and security implications (Onabowale, 2025). Fraud detection tools are confidence enhancers; however, they require a lot of infrastructure and trained personnel, which the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is yet to develop (Mohammed & Rahman, 2024). Individualized banking makes banking more convenient, yet can widen the divide when the access to more sophisticated digital banking is limited to city or wealthy customers. According to a survey conducted by Council (2021), 74 percent of Saudi consumers are willing to use AI-based banking services, however, almost half of them are worried about the privacy and security of their data, which highlights this conflict between adoption and trust.

This discrepancy between potential and reality highlights the main issue that is discussed in this paper. Although the AI is being enthusiastically discussed and the potential of its ability to transform the financial sector is evident in the existing literature, there is a lack of empirical evidence regarding its practical effects on financial access in the Saudi Arabian fintech industry. The current literature is inclined to focus on technology adoption models, consumer preferences, or theoretical discussions of innovation (Hussain et al., 2024; Mohammed & Rahman, 2024; Yi et al., 2023), but it hardly provides any direct correlation between AI-based financial services and the quantifiable results of accessibility, affordability, and engagement in terms of financial access. In addition, the majority of the existing studies are either conceptual or qualitative in character lacking a systematic and quantitative analysis based on the Saudi context in which the Vision 2030 offers urgency and opportunity to financial access (Brika et al., 2025; Moshashai et al., 2018). The current study fills that gap by carrying out primary quantitative research to test the impact of AI-based financial services such as robo-advisory, AI-based credit scoring, fraud detection, and personalized banking on financial access within the Saudi Arabian fintech industry to offer evidence-based information that can directly inform policy makers, fintech companies, investors and regulators in their decision making. In line with this, the overarching aim is to evaluate the impact of AI-powered financial services on financial access in the Saudi Arabian fintech sector, with specific objectives as follows:

- (1)

To investigate how AI-based robo-advisory platforms influence financial access for diverse consumer groups in Saudi Arabia.

- (2)

To examine the role of AI-based credit scoring in expanding credit opportunities for underserved individuals and small businesses, thereby enhancing financial access.

- (3)

To assess the effectiveness of AI-powered fraud detection systems in enhancing trust and security, thereby encouraging positive financial access.

- (4)

To evaluate the impact of AI-based personalized banking solutions on improving financial accessibility.

Meeting these research objectives, the study has great significance for policymakers to come up with regulations that promote the responsible use of AI-based financial services as the drawn implications can help fintech companies improve their products and make their offerings more accessible, making them more specific to various consumer groups instead of focusing on digital-savvy ones. Furthermore, the study provides the insights for the regulators to create a balance between innovation and regulation so that the use of AI is aligned with the values of transparency and fairness adopting a multi-stakeholder approach, where fintech firms, regulators, and policymakers collaborate to maximize the benefits of AI-powered financial services while minimizing associated risks as well as the study also provide a practical foundation for industry practitioners to design customer-centric strategies that strengthen trust, enhance consumer loyalty, and drive sustainable growth for the investors in alignment with Vision 2030’s goals of economic diversification and financial access. In this way, the ultimate beneficiaries of the evidence are the consumers themselves who will have access to affordable and reliable financial solutions through AI-driven innovation as AI-enabled services automate processes, reduce operational costs, enhance financial literacy, and create personalized services, all of which translates to a better experience and more inclusive financial access for consumers, especially those in underserved communities.

The remainder of this manuscript is structured as follows: the next discussion is about citing a critical literature review that situates the study within existing work on AI-powered financial services and financial access followed by a description of the theoretical framework that underpins the research design; the methodology section then explains the positivist philosophy, deductive approach, survey strategy, and data analysis techniques used while the findings and discussion section present the results and interprets them in relation to both the objectives and the existing literature. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the key contributions, practical and policy implications, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Academic Literature and Research Hypothesis

A study by Onabowale (2025) point to the fact that AI-based robo-advisory platforms as effective solutions to increasing access to finance highlighting that robo-advisors have played a significant role in lowering the barrier to entry through the provision of low-cost automated financial advice to people who have historically not had access to professional advice. Supporting this, Yi et al. (2023) argued that streamlined interfaces and gamified experiences promote adoption, especially among younger and less wealthy clients contending that robo-advisors supported by reputable institutions can instill more trust which assists reluctant customers to use online investment platforms. This claim is further enforced by Ashrafi (2023), who affirmed that these platforms democratize financial management by accessing middle-income and mass-affluent users who had not previously been targeted by customized advice as these platforms offer low-cost, user-friendly, and scalable solutions for portfolio construction, rebalancing, and financial planning, thus democratizing access to wealth management services traditionally reserved for affluent clients. Although there are such advantages, researchers such as Zhu et al. (2023) highlighted that robo-advisors could potentially leave out people who are not digitally literate or have access to stable internet, especially in developing areas. This scenario, according to Kofman (2025), pose a significant risk of leaving out digitally illiterate individuals and those lacking reliable internet access, particularly in developing areas, creating a new form of financial exclusion which means that the benefits of accessible and affordable financial services that robo-advisors aim to provide are not reaching everyone, limiting their potential to truly make finance more inclusive and affordable for all as highlighted by Arora et al. (2025). These studies collectively point out that there is a conflict between inclusivity and exclusivity in a way that digital differences, mistrust, and reliability of data that limit efficacy among vulnerable populations which implies that robo-advisors work best in the environment with high digital literacy and developed financial ecosystems but fail in the environment with low access and trust. Based on the presented arguments, the following research hypothesis has been formulated to be tested in the context of in the Saudi Arabian fintech sector.

H1: AI-based robo-advisory platforms have a positive and significant impact on financial access.

The use of AI-based credit scoring is being applauded as a way of enhancing financial access according to Hussain et al. (2024) in a way that AI-driven models are better than traditional credit scoring because they use alternative data to enable thin-file clients to access credit as Mesihovic and Nordström (2021) believe that by integrating diverse, real-time data points, AI-powered credit scoring models can improve approval rates, reduce risk and extend credit to those previously overlooked by conventional systems. Furthermore, Omotosho (2025) and Mehmood et al. (2024) noted that AI systems decrease the risks of default by more accurately predicting repayment, allowing lenders to serve a larger number of people asserting that other sources of data, including mobile phone usage or utility payments, give lenders a better understanding of borrowers, especially in underserved markets. But critics caution that AI-based credit scoring can replicate or even enhance social inequalities (Lehner et al., 2022; Omokhoa et al., 2021) demonstrating that algorithms that are trained on biased data can indirectly discriminate against some groups, such as residential location as a proxy variable as well as the issue of AI-based algorithmic opacity, which does not allow customers to know how credit decisions are made, compromising accountability. The cited studies asserted that AI-assisted credit scoring improves access in the most regulated jurisdictions and consumer protection, whereas in less regulated settings, the probability of bias is high which may lead to limited financial access. Based on the presented arguments, the following research hypothesis has been formulated to be tested in the context of in the Saudi Arabian fintech sector.

H2: AI-based credit scoring has a positive impact on financial access.

AI-based fraud detection systems are often hyped as the key to financial access in different studies. For example, Alaba et al. (2025) carrying out a study in Nigerian banking sector demonstrates that machine learning models are better than traditional rule-based methods because they detect intricate fraud patterns, which minimizes financial crime. The study concluded that AI-based fraud detection systems positively and significantly improve financial access by enabling more accurate fraud prevention, reducing false positives, and allowing financial institutions to serve more customers securely. In a similar way, Nweze et al. (2024) affirmed that AI-enabled fraud detection systems process vast datasets in real-time to detect anomalies, adapt to new threats, and lower the risk of financial loss, which in turn strengthens customer trust and supports broader access to financial services. This scenario is also highlighted by Mabula and Han (2018), who pointed out that AI systems that track billions of transactions per day with great precision create confidence among the consumers to engage more in digital banking. The cited studies collectively note that improved fraud prevention safeguards both the customers and institutions, which increases trust in financial services and indirectly increases access. Although these gains are made, there are a number of challenges which limit the ability of the adopted processes to enhance financial access. For example, Mohammed and Rahman (2024) points out the problem of false positives, which is the detection of legitimate transactions as fraudulent, annoying customers and potentially deterring their use. Another important factor is privacy as fraud detection involves gathering and processing sensitive personal information (Lehner et al., 2022). Sarioguz et al. (2024) affirming that fraudsters are constantly evolving to take advantage of vulnerabilities, and thus the system has to be constantly updated, which smaller institutions might not be able to afford. These studies indicate that although AI-based detection of fraud improves access to finance with the introduction of effective protection mechanisms but can jeopardize inclusion otherwise. Based on the presented arguments, the following research hypothesis has been formulated to be tested in the context of in the Saudi Arabian fintech sector.

H3: The financial access is positively and significantly improved by AI-based fraud detection systems.

Personalization in AI-based banking solutions is hailed as relevant and user-centric services which ultimately lead to enhanced financial access. According to Salem et al. (2019), AI-enabled personalization in financial solutions enhance customer engagement because it improves the products to fit the needs and behaviors of the individuals. This is mainly because AI-based predictive analytics allow financial institutions to optimize investment strategies based on the anticipated market trends, and enhance financial access by extending credit access to underbanked populations as pointed out by Baffour Gyau et al. (2024). In a similar way, Yi et al. (2023) emphasize that personalization makes financial information easier to comprehend and use by underserved groups, thus, improving their access to banking services asserting that customers who are served with personalized services have higher chances of adopting digital banking, which promotes inclusion while Omokhoa et al. (2021) indicate that personalization enhances customer satisfaction and customer loyalty, which results in greater financial involvement with caution that although personalization can go too far and can be over-customization, which could offer vulnerable customers the wrong products. This argument is supported by Lehner et al. (2022) and Mohammed and Rahman (2024), who noted that low-digital or less technologically accessible populations might not be able to fully benefit out of these services especially because of data privacy issue, since personalized banking will entail a lot of use of personal data. The cited studies notes that the offered AI-based customized banking solutions are the most effective in situations where the customers are digitally literate, and the data protection is strong, but it might not be applicable to vulnerable populations in less developed settings because it can create rifts or become an instrument of exploitation in case it is not controlled thus leading to decreased financial access. Based on the presented arguments, the following research hypothesis has been formulated to be tested in the context of in the Saudi Arabian fintech sector.

H4: AI-based customized banking solutions have a positive effect on financial access.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

This paper relies on two theories that are complementary to each other, namely, Innovation Diffusion Theory also adopted by Singh et al. (2022) and the Technology Acceptance Model also adopted by DV (2025) and Mehmood et al. (2024), to understand how AI-based financial technologies can affect financial access as they offer information on the factors behind adoption, user attitudes, and the circumstances in which AI-based solutions, including robo-advisory systems, credit scoring systems, fraud detection systems, and customized banking services, can enhance access to financial services. The Innovation Diffusion Theory was proposed by Rogers (2003) focusing on the diffusion of innovations within a social system based on five attributes that influence adoption namely relative advantage, compatibility, complexity, trialability, and observability highlighting that relative advantage in the context of financial technologies is expressed in the perceived value of AI solutions, including cost-saving, efficiency, and a wider range of accessibility than traditional banking practices while compatibility shows the level of compatibility between these technologies and the financial needs, lifestyles and cultural backgrounds of the users (Addula, 2025; Arora et al., 2025). Complexity is the perceived complexity of using AI-based services; the easier it is to use, the faster it can be adopted; trialability can be seen in pilot offerings or freemiums that enable customers to test out digital platforms, whereas observability can be seen in the visibility of the benefits of these technologies in peer networks as pointed out by Arora et al. (2025) and Madanchian and Taherdoost (2024). The cited studies taking into account the different attributes of theory argued that the extensive use of robo-advisors or AI-based credit scoring among some groups of people can prompt others to do the same, increasing access to finance highlighting that this theory can therefore be used to describe the spread of AI financial technologies in various segments and regions. Whereas Innovation Diffusion Theory deals with the diffusion of innovation, Technology Acceptance Model by Davis (1989) offers a more detailed perspective of user attitudes that lead to acceptance assuming that attitudes towards the adoption of a technology are determined by two factors, including perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Perceived usefulness in AI-based financial systems is the degree to which the customers feel that such services will enhance their financial decision-making, credit access, or transaction security. Perceived ease of use, in its turn, is associated with the consideration of whether people consider the platforms to be intuitive, accessible, and easy to handle without any specific financial or technical skills (Jena, 2025). These perceptions, in combination, influence behavioral intention, which leads to adoption. To illustrate, when customers are convinced that AI-based fraud detection will increase the safety of transactions and the interface is easy to use, they would be more willing to use digital banking services. Combining the two theories would enable a more balanced discussion of both social-system processes and user perceptions and provide a better basis to analyze how AI-based platforms can contribute to financial access in the Saudi Arabian fintech sector.

3. Research Methodology

This study methodology is based on the principles of positivism and deductive reasoning, which focus on objectivity, measurement, and the use of observable data to determine causal relationships (Saunders et al., 2019). Positivism was an appropriate philosophical choice, as the study aims to assess the objective effect of AI-based financial services on financial access instead of discussing subjective experiences or stories while deductive research approach helped the researchers to begin with theory and moves to data analysis to make sure that the results are not only contextually relevant but also placed within a wider academic discourse. Aligned with this, the research adopted a quantitative research design and cross-sectional time horizon to collect numerical data through surveys at one moment in time examining the current dynamics of the research variables of interest from employees working in the departments related to AI-based services, staff members of fintech firms, and owners of small enterprises who use digital financial solutions in Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam. Purposive sampling was used to guarantee the topicality of the answers, and in this case, the participants who have a real experience of using technologies like robo-advisory, AI-based credit scoring, fraud detection systems, or personalized banking services were considered since they are the groups that are most directly impacted by the implementation of AI in financial services and are working in the financial and technological hubs where fintech adoption is most visible (Campbell et al., 2020). To ensure this, a statement “Please fill out this questionnaire only if you are a current employee in the fintech industries of Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam and are either working in the departments related to AI-based services, staff members of fintech firms, or owners of small enterprises who use digital financial solutions” was added. The study targeted 240 respondents following 10:1 (ten responses against one item) items response theory, which is in line with the recommendations of Kline (2023) about the sample size required in large populations, to achieve reliable SEM results. Total 194 responses were received with a response rate of 80.84%.

The structured questionnaire was administered electronically which included both demographic items and measures of each construct rated on a five-point Likert scale with strongly disagree and strongly agree options. While collecting the data, the research was complied with different ethical considerations such as obtaining informed consent, protecting participant privacy and confidentiality, ensuring data accuracy and integrity, avoiding deceptive practices, and maintaining security of the collected information. The three items scale for AI-based personalized banking solutions from Bagozzi and Phillips (1982) also used by Salem et al. (2019), three items for financial access from Mabula and Han (2018), ten questions for AI-based credit scoring from Mesihovic and Nordström (2021), three items for AI-based robo-advisory from Venkatesh et al. (2012) also used by Ashrafi (2023) while five items for AI-based fraud detection systems from Alaba et al. (2025) were adopted.

Once data were collected, SPSS and structural equation modeling was used as an analytical technique, implemented through SmartPLS software. The analysis started with the presentation of summary of demographic characteristics of respondents and research variables using SPSS. Following this, convergent validity was affirmed, confirming that the instrument measures the intended concept and establishes the construct validity of the measurement tools beside confirming the normality assumption (Hair et al., 2019). The correlation analysis establishes the preliminary associations among research variables. Finally, SEM analysis using bootstrapping method was employed to test the developed research hypotheses, and model strength was further evaluated using effect size (f²).

4. Results And Discussion

4.1. Participants Characteristics

The demographic composition of respondents (

Table 1) shows that 33 participants (17.0%) were between 25-34 years, while the largest share came from the 45-54 age group with 56 respondents (28.9%). This was closely followed by 52 individuals (26.8%) aged 35-44 and 53 respondents (27.3%) aged 55 and above. The near-equal spread across age cohorts highlights that the use and perception of AI-powered financial services extend well beyond younger, tech-savvy consumers to middle-aged and older groups. This challenges the conventional assumption that fintech adoption is predominantly driven by younger generations and suggests that in the Saudi context, Vision 2030 reforms and digital transformation initiatives have successfully encouraged older populations to engage with innovative financial tools.

Gender and occupational backgrounds further enrich this profile. Male respondents comprised 114 (58.8%) of the sample, while females represented 80 (41.2%), reflecting improving gender inclusivity in fintech participation though men remain slightly more dominant. Occupationally, 57 respondents (29.4%) were directly employed in AI-based financial services, 64 (33.0%) worked in fintech firms, and 73 (37.6%) were small enterprise owners actively using digital finance. This balance between providers and end-users strengthens the study’s perspective on adoption and practical application. Geographical distribution also underlines representativeness: 71 participants (36.6%) resided in Riyadh, 70 (36.1%) in Jeddah, and 53 (27.3%) in Dammam, ensuring the sample covered Saudi Arabia’s main commercial and financial hubs where fintech growth is most concentrated.

4.2. Descriptive, Normality and Correlation Statistics

The descriptive statistics (

Table 2) suggest a consistent and positive perception of AI-powered financial services among respondents. Mean values for all constructs fall between 3.79 and 3.85 on a five-point Likert scale, indicating that participants generally agree with statements relating to AI-based credit scoring, robo-advisory, fraud detection, personalized banking, and financial access. The relatively small standard deviations (ranging from 0.76 to 0.95) reflect low dispersion, suggesting that opinions were moderately homogeneous across the sample. Skewness values are negative for all variables, between -0.61 and 0.89, while kurtosis ranges from -0.40 to -0.87, both falling within acceptable thresholds for normal distribution (±2 for skewness and ±7 for kurtosis) by Hair et al. (2019).

Correlation results reveal strong, positive, and statistically significant relationships among all independent variables and the dependent variable. The correlations exceed 0.80 in every case, with AI-based fraud detection showing the highest association with financial access (r = .879, p < 0.01), followed closely by robo-advisory (r = .854, p < 0.01) and credit scoring (r = .852, p < 0.01). Personalized banking also demonstrated a substantial positive correlation with financial access (r = .821, p < 0.01). These strong linkages suggest that the components of AI-powered financial services do not operate in isolation but reinforce one another in driving financial access.

4.3. Measurement Model – Factor Loadings and Convergent Validity

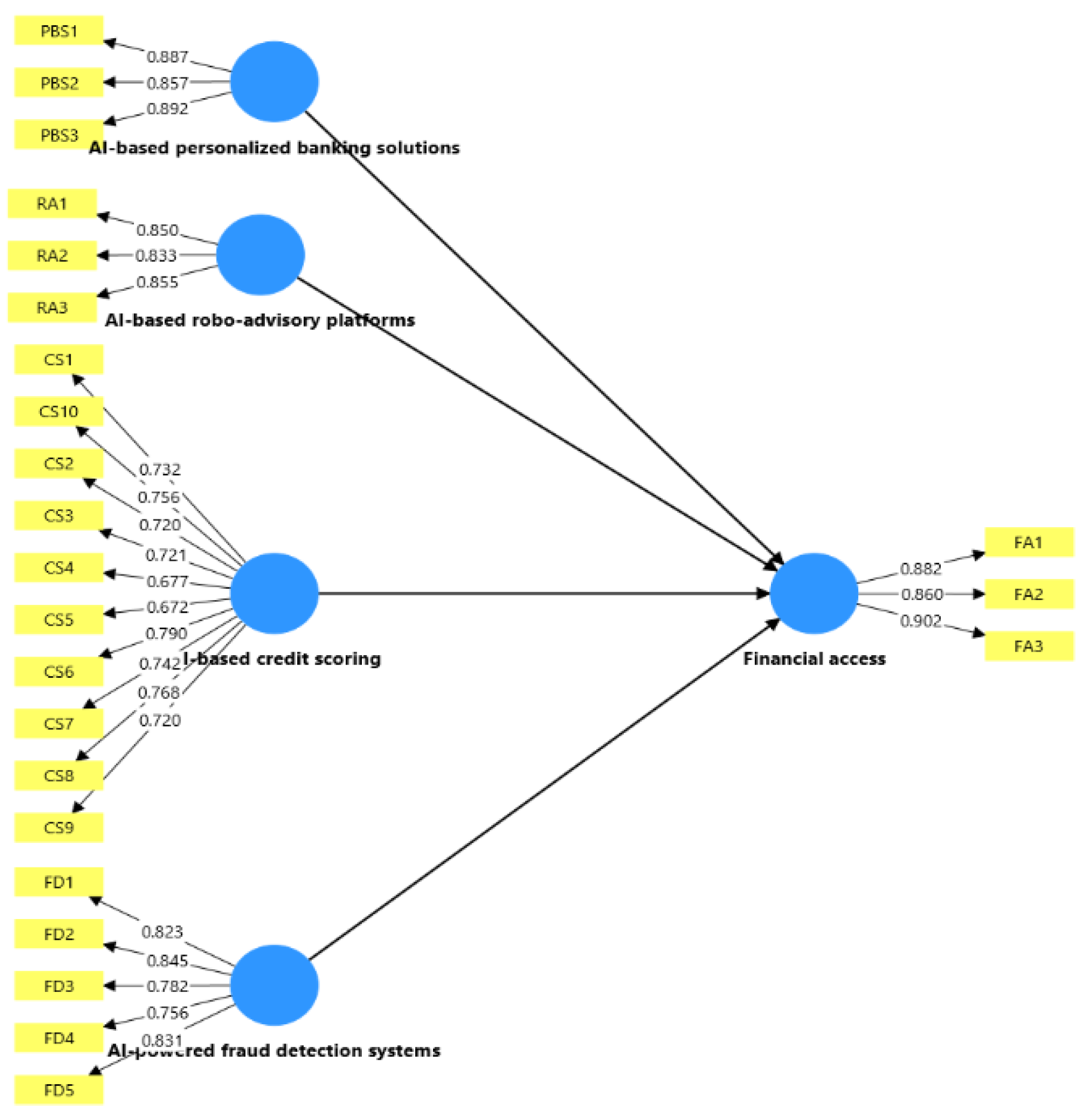

The results for factor loadings and reliability (

Table 3) provide strong evidence of measurement adequacy across all constructs. For AI-based credit scoring, item loadings ranged from 0.672 to 0.790, with all values exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.60 as proposed by Kaiser (1974) demonstrating that each indicator contributes meaningfully to the latent construct. Higher loadings were observed for CS6 (0.790) and CS7 (0.742), suggesting that these items best capture participants’ perceptions of credit scoring reliability, whereas lower but still acceptable loadings, such as CS4 (0.677) and CS5 (0.672), indicate moderate contributions. In contrast, constructs with fewer items, such as AI-based personalized banking, robo-advisory, fraud detection, and financial access, demonstrated consistently high loadings above 0.75, with several exceeding 0.85, highlighting strong coherence between the items and their respective constructs. These statistics are also revealed in

Figure 1.

As per the convergent validity statistics, the Cronbach’s alpha values ranged between 0.802 and 0.903, exceeding the 0.70 benchmark, thereby indicating internal consistency. Similarly, composite reliability (rho_A and rho_C) scores were all above 0.85, reinforcing the consistency of the scales. Convergent validity was also established through the AVE, with all constructs surpassing the 0.50 threshold. AI-based personalized banking and financial access demonstrated the strongest convergent validity with AVE values of 0.772 and 0.777 respectively.

4.4. Structural Model – SEM Analysis (Hypotheses Testing)

The structural model results (

Table 4) provide strong support for the influence of AI-powered financial services on financial access in Saudi Arabia. Among the four constructs, AI-powered fraud detection emerged as the most influential driver (β = 0.407, t = 3.005, p = 0.003), with a moderate effect size (f² = 0.09). This finding highlights the importance of trust and security in shaping consumer engagement with digital finance. In an environment where fraud risks can undermine confidence, effective detection systems appear to significantly enhance perceptions of accessibility, suggesting that users view secure platforms as essential gateways to inclusion. AI-based credit scoring also exerted a significant positive effect (β = 0.258, t = 2.414, p = 0.016, f² = 0.039), indicating that advanced credit assessment tools expand access by improving risk evaluation and enabling broader lending opportunities. Similarly, robo-advisory platforms demonstrated a positive and significant relationship with financial access (β = 0.213, t = 2.285, p = 0.022, f² = 0.032), reflecting growing consumer reliance on automated, low-cost investment advice that democratizes financial participation previously limited to wealthier segments.

In contrast, AI-based personalized banking solutions showed no significant impact on financial access (β = 0.048, t = 0.437, p = 0.662, f² = 0.002). This non-significance suggests that while personalization may enhance user satisfaction or loyalty, it does not directly translate into increased access to financial services. For Saudi Arabia, this highlights a gap where personalization strategies remain more cosmetic than structural in expanding inclusivity. The overall model fit is robust, with R² = 0.804 and adjusted R² = 0.800, meaning that 80% of the variance in financial access is explained by the four AI-enabled services. These results are also shown in

Figure 2.

4.5. Model Fit Summary

The model fit indices (

Table 5) confirm that the structural model is both statistically adequate and theoretically sound. The SRMR value of 0.074 for both the saturated and estimated models falls below the recommended threshold of 0.08, indicating that the model accurately reproduces the observed correlations (Hair et al., 2019).

The d_ULS statistic, reported at 1.635 for both models, further supports the absence of substantial discrepancies between observed and predicted covariance structures. While this index has no strict cut-off, lower values are desirable, and the stability of d_ULS across the saturated and estimated models confirm that the model is well-fitting.

4.6. Discussion on Results

The first objective was to investigate how AI-based robo-advisory platforms influence financial access in the Saudi Arabian fintech sector. The results of the SEM analysis show that AI-based robo-advisory platforms have a positive and significant impact on financial access (β = 0.213, t = 2.285, p = 0.022). Therefore, H1 is accepted. This indicates that robo-advisory services are effective in reducing barriers to financial advice by providing low-cost and easily accessible solutions, especially for middle-income and mass-affluent users. These findings are consistent with Yi et al. (2023) and Ashrafi (2023), who argued that robo-advisors democratize financial management and extend advisory services to previously excluded groups. From the Innovation Diffusion Theory perspective (Rogers, 2003), robo-advisors provide clear relative advantage through affordability and ease of use, while their compatibility with digitally literate consumers explains the positive adoption patterns. The Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989) further reinforces this finding, as users perceive robo-advisors as useful tools for improving financial decision-making. However, earlier research by Zhu et al. (2023) and Kofman (2025) warned that low digital literacy and access inequalities may hinder inclusivity, a challenge that remains relevant in the Saudi context. Thus, while robo-advisory platforms are contributing to financial access, efforts to increase digital education are critical to avoid new forms of exclusion.

The second research objective was to examine the role of AI-based credit scoring in expanding credit opportunities in the Saudi Arabian fintech sector. The SEM analysis revealed that AI-based credit scoring has a positive and significant relationship with financial access (β = 0.258, t = 2.414, p = 0.016). Therefore, H2 is accepted. This suggests that AI-driven models improve lending opportunities by using alternative data sources beyond traditional credit histories, thus enabling underserved individuals and small businesses to access loans. The results are aligned with Hussain et al. (2024), Omotosho (2025), and Mesihovic and Nordström (2021), who demonstrated that AI-based scoring reduces default risks and expands approval rates. Within the Technology Acceptance Model, this reflects strong perceived usefulness, as lenders benefit from better risk evaluation and consumers benefit from increased access. According to the Innovation Diffusion Theory, observability also plays a role, since the visible success of AI-based credit approvals encourages further adoption. However, scholars such as Lehner et al. (2022) caution that algorithmic opacity and bias may reinforce social inequalities if not properly regulated. In Saudi Arabia, the positive impact observed in this study suggests that regulatory oversight and data-driven approaches are already mitigating these risks to some degree. These results demonstrate that AI-based credit scoring is a viable enabler of financial access, provided that transparency and fairness remain priorities.

The third objective was to assess the effectiveness of AI-powered fraud detection systems in enhancing trust and financial access in the Saudi Arabian fintech sector. The findings show that AI-powered fraud detection systems have the strongest effect on financial access (β = 0.407, t = 3.005, p = 0.003). Accordingly, H3 is accepted. The stronger impact of fraud detection compared to robo-advisory and credit scoring highlights that fraud detection systems are an essential driver of inclusion, validating their central role in supporting Vision 2030’s financial access goals. The result is consistent with Alaba et al. (2025) and Nweze et al. (2024), who highlighted that AI-based fraud detection reduces financial crime, detects anomalies in real time, and builds consumer confidence in digital services. The Innovation Diffusion Theory supports this outcome through compatibility, as consumers prioritize systems that align with their need for safety in financial transactions. Similarly, the Technology Acceptance Model emphasizes usefulness, as fraud detection addresses a core concern of users: security.

For the fourth objective, the SEM results revealed that AI-based personalized banking solutions did not show a significant impact on financial access (β = 0.048, t = 0.437, p = 0.662); therefore, H4 is rejected as this result diverges from studies such as Salem et al. (2019) and Baffour Gyau et al. (2024), who argued that personalization enhances customer engagement and financial access. While personalization may improve satisfaction and loyalty, the evidence from Saudi Arabia suggests that it does not yet translate into expanded financial access. This may be due to limited digital literacy, privacy concerns, and uneven access to advanced digital services, as highlighted by Lehner et al. (2022) and Mohammed and Rahman (2024). From a theoretical perspective, the insignificance reflects limitations in both IDT and TAM: personalization may lack compatibility with underserved groups and may not provide sufficient perceived usefulness to encourage adoption beyond digitally advanced consumers. The implication is that personalized banking in Saudi Arabia currently functions more as a value-added feature for existing customers rather than a structural mechanism to reach excluded groups. This finding signals that personalization must evolve beyond cosmetic enhancements and address inclusivity challenges if it is to contribute to national financial access objectives.

5. Conclusion

5.1. Conclusion

Grounded into Innovation Diffusion Theory and Technology Acceptance Model, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of AI-powered financial services such as robo-advisory platforms, AI-based credit scoring, AI-powered fraud detection systems and AI-based personalized banking solutions on financial access in the Saudi Arabian fintech sector. To achieve this purpose, the study adopted the positivism philosophy, deductive approach, and quantitative research design. Aligned with this, the research adopted a cross-sectional time horizon and purposive sampling technique to collect numerical data through surveys from 240 employees working in the departments related to AI-based services, staff members of fintech firms, and owners of small enterprises who use digital financial solutions in Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam. Total 194 responses were received with a response rate of 80.84%. Once data were collected, SPSS and structural equation modeling was used as an analytical technique, implemented through SmartPLS software. The findings reveal that three of the four proposed hypotheses were supported. More specifically, the robo-advisory platforms significantly improved financial access, showing that affordable and accessible advisory services democratize financial management while personalized banking solutions showed no significant effect, suggesting that while customization may enhance satisfaction, it does not yet translate into broader financial access in Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, AI-based credit scoring was also significant, demonstrating that alternative data-driven models expand credit opportunities for underserved individuals and small enterprises and most importantly, the fraud detection emerged as the strongest predictor, highlighting that trust and security are fundamental to consumer participation in digital finance. Collectively, these results underscore the transformative potential of AI for supporting Saudi Vision 2030’s financial access agenda, while also drawing attention to gaps in personalization strategies.

5.2. Practical and Theoretical Implications

In practical terms, the findings imply that fintech companies and financial institutions should prioritize robo-advisory services as a means of expanding access to professional financial advice. By keeping platforms affordable and user-friendly, robo-advisors can continue to attract middle-income groups and new investors for which the firms should also invest in digital literacy initiatives to ensure that older consumers and less tech-savvy groups are not excluded. Second, AI-based credit scoring presents a valuable opportunity to extend credit access, especially for small businesses and entrepreneurs who lack traditional collateral or credit history. Policymakers and regulators should therefore encourage the adoption of these models while simultaneously enforcing strict fairness, transparency, and accountability standards to prevent algorithmic bias. Third, the strong role of fraud detection highlights that security is a non-negotiable requirement for financial access therefore, fintech providers should invest in advanced fraud detection tools to protect consumers and reassure them about the safety of digital finance. Regulators, meanwhile, should develop frameworks that balance effective fraud prevention with data privacy protections, ensuring that consumer trust is not compromised by over-surveillance or frequent false positives. Fourth, the non-significant role of personalized banking solutions suggests that personalization strategies in Saudi Arabia are currently more cosmetic than transformative therefore financial institutions should reframe personalization to focus on inclusivity by tailoring services for vulnerable groups, such as women entrepreneurs and rural populations. This requires not only technological investments but also policy incentives to encourage equitable personalization practices encouraging a multi-stakeholder approach, where fintech firms, regulators, and policymakers collaborate to maximize the benefits of AI-powered financial services while minimizing associated risks.

In terms of theoretical implications, by applying both the IDT and the TAM, the research extends existing frameworks into the Saudi fintech context in a way that the acceptance of H1, H2, and H3 demonstrates that IDT’s dimensions of relative advantage, compatibility, and observability are strongly reflected in robo-advisory, credit scoring, and fraud detection. This insight affirms that the consumers perceive these technologies as advantageous and aligned with their financial needs, supporting the notion that diffusion is driven by visible and useful benefits. Similarly, TAM’s construct of perceived usefulness was reinforced across these three services, showing that utility remains the dominant factor in adoption of AI-driven finance. At the same time, the rejection of H4 (personalized banking solutions) highlights an important boundary condition for both theories suggesting that usefulness and compatibility are not universally applicable, as personalization failed to translate into broader access as this challenges TAM’s assumption of uniform adoption drivers and IDT’s focus on relative advantage, signaling that contextual and cultural factors such as digital literacy and privacy concerns need greater integration into theoretical models. Overall, the study refines these theories by emphasizing that adoption is shaped not only by technological attributes but also by the socioeconomic environment in which they operate.

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

While this study contributes valuable insights, it is subject to certain limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the research adopted a cross-sectional design, capturing perceptions at a single point in time. This restricts the ability to identify long-term effects or evolving adoption patterns. Future studies could employ longitudinal designs to better understand how AI-powered financial services influence access over time. Second, the study focused only on three major cities such as Riyadh, Jeddah, and Dammam. Although these are the leading fintech hubs in Saudi Arabia, the findings may not fully represent consumers in smaller cities or rural areas, where digital infrastructure and literacy levels may differ. Future research could broaden the geographical scope to capture a more diverse range of participants. Third, the research relied on self-reported survey data, which may be influenced by social desirability bias or limited respondent awareness therefore combining surveys with qualitative interviews or case studies could provide richer insights into how individuals experience and perceive AI-powered financial services. Finally, this study examined four specific AI applications which leave a gap in terms of exploring other emerging tools such as blockchain-based identity verification, AI-driven insurance, or decentralized finance platforms to build a more comprehensive understanding of technological impacts on financial access.

References

- Addula, S. R. Mobile Banking Adoption: A Multi-Factorial Study on Social Influence, Compatibility, Digital Self-Efficacy, and Perceived Cost Among Generation Z Consumers in the United States. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 2025, 20(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaba, J. S.; Ahmed, S. J.; Farida, A. P.; Oluwatosin, O. V. Adoption of AI-Driven Fraud Detection System in the Nigerian Banking Sector: An Analysis of Cost, Compliance, and Competency. Economic Review of Nepal 2025, 8(1), 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarrak, M. S.; Alokley, S. A. FinTech: Ecosystem, Opportunities and Challenges in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2021, 14(10). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Rajesh, A.; Misra, R.; Singh, G. Bridging technology and trust: the role of AI-driven robo-advisors in middle-class financial management. Management Decision 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, D. M. Managing Consumers’ adoption Of Artificial Intelligence-Based Financial Robo-Advisory Services: A Moderated Mediation Model. Journal of Indonesian Economy & Business 2023, 38(3), 270–301. [Google Scholar]

- Baffour Gyau, E.; Appiah, M.; Gyamfi, B. A.; Achie, T.; Naeem, M. A. Transforming banking: Examining the role of AI technology innovation in boosting banks financial performance. International Review of Financial Analysis 2024, 96, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P.; Phillips, L. W. Representing and testing organizational theories: A holistic construal. Administrative science quarterly 1982, 27(3), 459–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brika, S. k.; Adli, B.; Mili, K.; Bengana, I.; Khababa, N. Key Sectors Driving Saudi Vision 2030 Diversification. Journal of Posthumanism 2025, 5(4), 609–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Greenwood, M.; Prior, S.; Shearer, T.; Walkem, K.; Young, S.; Bywaters, D.; Walker, K. Purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing 2020, 25(8), 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council, A. The global energy agenda; Report; Washington, DC, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F. D.; Al-Suqri, MN. Technology acceptance model: TAM. Al-Aufi, AS: Information Seeking Behavior and Technology Adoption 1989, 205(219), 5. [Google Scholar]

- DV, L. Artificial Intelligence in Financial Inclusion: An Impact on Financial Accessibility and Efficiency in India. Available at SSRN 5285866; 2025.

- Hair, J. F.; Risher, J. J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European business review 2019, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Khan, M.; S, A.; K, K. Enhancing Credit Scoring Models with Artificial Intelligence: A Comparative Study of Traditional Methods and AI-Powered Techniques; 2024; pp. 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, R. K. Factors Influencing the Adoption of FinTech for the Enhancement of Financial Inclusion in Rural India Using a Mixed Methods Approach. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2025, 18(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H. F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39(1), 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Alhadi, F. A. F. Fintech and financial inclusion in Saudi Arabia. Review of Economics and Finance 2022, 20(1), 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling; Guilford publications, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kofman, P. Scoring the Ethics of AI Robo-Advice: Why We Need Gateways and Ratings. Journal of business ethics 2025, 198(1), 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, O. M.; Ittonen, K.; Silvola, H.; Ström, E.; Wührleitner, A. Artificial intelligence based decision-making in accounting and auditing: ethical challenges and normative thinking. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 2022, 35(9), 109–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabula, J. B.; Han, D. P. Financial literacy of SME managers’ on access to finance and performance: The mediating role of financial service utilization. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 2018, 9(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madanchian, M.; Taherdoost, H. AI-Powered Innovations in High-Tech Research and Development: From Theory to Practice. Computers, Materials & Continua 2024, 81, 2133–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, S.; Khan, M. Z.; Ghaffar, A. Exploring the mediating effect of financial knowledge on technological innovations and financial accessibility. Bulletin of Management Review 2024, 1(4), 343–359. [Google Scholar]

- Mesihovic, A. E.; Nordström, H. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning usage in credit risk management-A study from the Swedish financial services industry. Bachelor Thesis, University of Gothenburg, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, A. F. A.; Rahman, H. M. A.-A. The role of artificial intelligence (AI) on the fraud detection in the private sector in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Arts, Literature, Humanities and Social Sciences 2024, (100), 472–506. [Google Scholar]

- Moshashai, D.; Leber, A.; Savage, J. Saudi Arabia plans for its economic future: Vision 2030, the National Transformation Plan and Saudi fiscal reform. British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 2018, 47, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nweze, M.; Avickson, E.; Ekechukwu, G. The Role of AI and Machine Learning in Fraud Detection: Enhancing Risk Management in Corporate Finance. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews 2024, 5(10), 2812–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omokhoa, H.; Ogundeji, I.; Ewim, P.-M.; Achumie, G.; Pub, A. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence to Enhance Financial Inclusion and Reduce Global Poverty Rates. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation 2021, 02, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omotosho, M. Exploring the role of ai-driven credit scoring systems on financial inclusion in emerging economies. American Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 2025, 9(01), 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Onabowale, O. The Rise of AI and Robo-Advisors: Redefining Financial Strategies in the Digital Age. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews 2025, 6, 4832–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. Diffusion of innovations. In Free Press. New York; 2003; Volume 551, p. 900. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, M. Z.; Baidoun, S.; Walsh, G. Factors affecting Palestinian customers’ use of online banking services. International Journal of Bank Marketing 2019, 37(2), 426–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAMA. Navigating Saudi Arabia’s Regulatory Landscape for Fintech Success. 2023. Available online: https://www.jawanpartners.com/insights/navigating-saudi-arabia-regulatory-landscape-for-fintech-success.

- Sarioguz, O.; Miser, E.; Teslim, B. Integrating AI in financial risk management: Evaluating the effects of machine learning algorithms on predictive accuracy and regulatory compliance. 2024, 789–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research methods for business students; Pearson education, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Singh, S.; Raman, R.; Thakur, R.; Johar, I.; Singh, P. Exploring Dimensions of Financial Inclusion from Stakeholders’ Perspectives: Evidence from Rural Areas of Jammu District. Acta Universitatis Bohemiae Meridionalis 2022, 25, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J. Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly 2012, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T. Z.; Rom, N. A.; Hassan, N. M.; Samsurijan, M. S.; Ebekozien, A. The Adoption of Robo-Advisory among Millennials in the 21st Century: Trust, Usability and Knowledge Perception. Sustainability 2023, 15(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Sallnäs Pysander, E.-L.; Söderberg, I.-L. Not transparent and incomprehensible: A qualitative user study of an AI-empowered financial advisory system. Data and Information Management 2023, 7(3), 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).