1. Introduction

The incorporation of financial technologies within the banking sector has resulted in transformation of the sector and created a win-win situation for banks and customers. Transformation includes 24-hour banking services access, self- serving machines, and financial integration among others which advance digital banking. Additionally, the digital age has led to paradigm shift in business models. With digitalization increasing and becoming integral in customer`s lifestyles as it brings convenience in accessing banking services. Digital banking has become increasingly crucial as new risks and vulnerabilities emerge on the digital landscape.

Historically, traditional financial institutions have long been at the forefront of using information technologies (Windasaria, et al., 2022; Haddad & Hornuf, 2019). However, today’s world is defined by rapid technologically induced innovative solutions that allow for an open environment. Dissanayake, Popescu, and Iddagoda (2023) observed that the financial services sector is experiencing a significant shift, marked by the appearance of innovative financial technological solutions which pose a threat to conventional banking services. For instance, new ways of interacting with customers have emerged because of the integration of both the digital and physical environments (Tanda & Schena, 2019).

Aljudaibi and Amuda (2024) concurred with Dissanye et al. (2023) that there has been noticeable rise in the frequency of customer engagement across various interaction channels during the last decade. Above all, financial institutions have been forced to adapt to this shift by introducing hybrid customer engagements, physical and virtual. For this reason, technological innovations coupled with evolving modern consumer expectations lay the path for a more digitized future. Understandably, physical branches and staff are being rendered redundant as banking services and delivery channels undergo a massive transition from traditional, non-digitalized operations backed by bank employees to totally digital and self-service. Gaviyau and Sibindi (2023) posit that the foundation for banking is now digital, but real innovation is the ultimate test.

Noticeably, traditional banks are shifting either by closing bank branches or incorporating innovative technological solutions to banking (Dissanye et al., 2023; Polat, 2021). Despite fintech taking some market share from the banks, their presence is not to substitute banks but to complement the existing banking service provision (Elsaid, 2023; Bunea, Kogan, & Stolin, 2016).

In terms of risks, traditional banking regulations fail to keep up with the rapid emergence of digital financial services since they were developed for brick-and-mortar type of institutions. On the other hand, both digital and traditional banks face similar risks. Thus, the transition to digital banks and banking requires responsive regulations. Indeed, digital banking has become part of many people’s daily lives, and this business model is relatively new.

Globally, digital and traditional banks are being subjected to the same regulations, but some jurisdictions have developed regulatory frameworks specifically for digital banks (Biswas, Saha, Paulc & Kumer, 2024). For instance, in 2020 four digital banks licenses were issued in Singapore and no other have been issued in Singapore while Malaysia issued four digital banks licenses in 2022 (Bank Negara Malaysia, 2022: Monetary Authority of Singapore, 2020).

In designing the digital banks regulation as part of the financial services sector policy, there is need to be cognisant of the dual policy challenges of seeking to ensure the financial system’s safety and to protect customers’ interests. Furthermore, to leverage the emerging opportunities and tackle associated challenges in the new digital and customer landscape. Undoubtedly, the banking sector must concurrently address the associated emerging risks and implications of protecting client data and privacy (Duan, 2024; Allen, Gu, & Jagtiani, 2021).

Against this background, a research query was adopted to enable the bibliometric review of the subject under study. The paper is organized into five sections. The first section focused on the introduction to the subject under study, this was followed by section 2 which discusses the literature underpinning the study.

Section 3 focuses on the research methodology adopted. Presentation and discussion of results are shown in

Section 4. Finally,

Section 5 provides the conclusions and directions of future studies.

2. Literature Review

To enhance understanding of the emerging risks associated with fintech and digital banks, literature was gathered. The literature focuses on theoretical foundation, emerging risks and evolution of banking integrating with technology. Importantly, there is a need to trace the origins and how the banking sector has evolved over the years with technology being the driving force. Firstly, to be discussed is the theoretical foundation followed by evolution of banking sector integrated with technology and lastly emerging risks in the digital era.

2.1. Theoretical Literature

The three theories provided an insight into the foundation upon which the future of banking is anchored and responding thereof. These theories are namely, institutional theory, information asymmetry and holistic digital maturity model. These are discussed below:

2.1.1. Institutional Theory

The institutional theory was advanced by Scott in 1987. The theory postulates that procedures and mechanisms form structures, rules and behavior to explain social behavior. Additionally, this instils values as organizations are continually evolving in response to the business environment. Banking is anchored on values of trust and confidentiality; consumers expect that to continue even in the digital era where there is minimal bank-customer interaction.

Institutions are at different levels of institutionalization as they are not constant (Peters, 2000). Scott (2004) argued that institutions existence is due to social interactions among people. As social interactions take effect, this influences the powers of groups, shapes ideas, influences policy coordination and public decisions making. Generally, organizations change over time in terms of their effectiveness.

Institutional theory is anchored on the integration of social, political, and economic factors. The theory attempts to distinguish as to why some organizational structures and procedures become predominant while others may be marginalized or even have an unfavourable prospect of weakening completely (Agoba et al. 2023; Hallett & Hawbaker 2021). By recognizing institutional forces, banks may better manage the competitive landscape, through incorporating digital innovations to meet the evolving stakeholders’ needs and expectations.

2.1.2. Asymmetric Information Theory

The three researchers namely Akerlof, Spence and Stiglitz advanced the information asymmetry theory in 1971 (Smith & Doe, 2023; Auronen, 2003). Since the advancement, the theory has been used to explain and describe phenomena within the economic and business domain among others (Smith & Doe, 2023). The theory offers insights into understanding how markets or economic sectors operate and influencing associated behaviour. Failure to align market behaviours can result in imperfect outcomes caused by adverse selection and moral hazards (Auronen, 2003).

Asymmetry of information among the economic participants is reduced by an intermediary market institution known as counteracting institution (Nygaard & Silkoset, 2023; Auronen, 2003). When applied to this study, the regulator serves that role of reducing information asymmetry by regulating the financial services sector. Although Fintechs and banks target the same consumers with different information sets which make them competitive. Regulation by design is to correct the market imperfections, as failure can result in excessive risk-taking behaviour (Iyelolu, Agu, Idemudia & Ijomah, 2024). Therefore, the existence of regulator brings complexity to the information availability.

This theory postulates that economic agents operate in an environment associated with biased and incomplete information. Information influences the behavior of economic participants. Decisions are based on this set of imperfect information to attain economic gain. Thus, the theory offers insights into the current operating environment where Fintechs have identified opportunities within the banking sector while the traditional banks are slowly adapting and responding because of legacy systems. On the other hand, Fintechs serve as an avenue in transforming the banking sector.

Applying to this study, with the incorporation of fintech into the banking sector consumer decision making, security and trust in the digital environment can be impacted. Hence, requiring regulatory responses such as disclosure requirements, regulatory licensing and consumer protection among others.

2.1.3. Holistic Digital Maturity Model (HDMM)

The model was advanced by Aras and Büyüközkan (2023) who developed the model based on the shortfalls of the other maturity models. The maturity models first appeared within the software engineering domain in the 1970s (Minh & Thanh, 2022; Chanias & Hess, 2016). Indeed, this has evolved into a crucial tool to assess the status quo and improve thereof. Berghaus and Back (2016) opines that a maturity model offers guidance on the approach entities can adopt to plan and implement digital transformation. Critique of the maturity models included the model being centered on improving specific organization’s capabilities entailing further developing the model in line with digital transformation (Minh & Thanh, 2022).

The Holistic Digital Maturity Model is based on six interacting elements in the journey of digital transformation. Based on each organization’s assessment they would be able to identify existing gaps between the current situation and intended goals. The six dimensions being digital strategy, digital value, digital processes, digital technology and data, digital work and digital governance.

Firstly, digital strategy assesses long term organizational aspects that create value in digital transformation. Secondly, digital value focuses on the value creation from the product to customer offering. This entails new product offering, innovation and customer value offering. Thirdly, digital processes examine how the organization’s process architecture and business process management is affected by strategies and management of the digitalization processes.

Fourthly, is digital technology and data which evaluates the technologies and solutions which put the transformation process in a sustainable manner. The fifth dimension, digital work, focuses on employees upskilling in the digital transformation agenda to remain competitive. Lastly, digital governance focuses on managerial and cultural that need to be addressed to ensure successful implementation and sustainability of the digital transformation.

Gökalp and Martinez (2022) argued that the inclusion of digital governance remains key to the success of the digital transformation process. Though the model is generic it can still be applied in the financial services sector to guide the transformation process to digital banks and banking. Furthermore, providing an opportunity to develop targeted solutions to accelerate the transformation. Thus, the holistic model allows for the examination and management of all the elements within the digital transformation journey. The digital transformation should be considered as an ongoing and iterative growth process to steering company success.

2.2. Banking Evolution and Integration with Information Communication Technologies (ICT)

Since immemorial time, businesses have made use of technology in business operations and with the developments, changes have been implemented. These changes include modern production methods, customer engagements and business operations among others which have led to spurred productivity. Importantly, the financial services sector was spared, and information technologies have remained core to their functions.

Megargel, Shankararaman, and Reddy (2018) observed that technological changes have gone through three stages namely data processing, client server and predictive. Noticeably, the banking sector has evolved from banking 1.0 to the current banking 5.0 (Chougule & Dudekula, 2024; Rathnayake, 2023).

Table 1 shows the integrated changes between the banking sector and incorporated technologies which provide insights into the evolution process and how the future is expected to be.

Mehdiabadi et al, (2020) observed that Banking 1.0, refers to the traditional banking concept which operated pre-1960, where banking services were personalised with branches operating at specified times. According to Megargel, et al. (2018) due to the analogue system that was being used the period was known as the data processing years. Transactions in the banking sector were primarily done at the branches in bulk with processing at the end of day. The period, also known as Banking 2.0, advanced from Banking 1.0 as banks started having off branch operations and branch networks growing (Chougule & Dudekula, 2024).

Banking 3.0 stretched from 1980s to 2000s. During this period banks facilitated IT-based infrastructures to enable bank clients to interact with the bank in addition to the new service offered by banks. The new service offerings were prompted by innovative technologies such as internet banking which was popularised in the 1990s with the advent of banks having worldwide websites. Subsequently, Banking 4.0 encourages collaboration and innovation in the financial services ecosystem with real time processing of transactions.

Banking 5.0 is going to be characterised by Exchange-traded funds (ETFs), cryptocurrencies, high-frequency trading, intelligent banking, robo-advisors and cobots, embedded banking, and responsible banking. Thus, Banking 5.0 would require greater collaboration between human and intelligent systems (Chougule & Dudekula, 2024; Rathnayake, 2023).

Comparing Banking 4.0 and Banking 5.0, collaboration in Banking 4.0 centered on financial institutions with fintechs while Banking 5.0 is on human and intelligent system. This shows great advancement in the interaction which requires traditional banks to move away from legacy systems.

2.3. Emerging Risks

Fintech has revolutionized the traditional financial system, resulting in improved access to financial services and innovative banking practices with convenience underpinning this. Alongside the benefits, fintech has brought emerging risks that must be carefully addressed in line with the regulator`s mandates such as consumer protection and financial stability. The emerging risks include cybersecurity, operational, data protection, and regulatory arbitrage. Discussed below are some of the risks:

2.3.1. Cybersecurity and Data Privacy Risks

Cybersecurity remains as a significant issue faced by the financial services sector. Financial services are increasingly digital, making systems and bank customers more vulnerable to identity theft, data breaches, and cyberattacks (Duran & Griffin, 2021). Sahu and Kumar (2024) highlighted that though decentralised financial platforms aim at promoting peer to peer transactions and eliminating bank charges they contribute to increased cybersecurity risks. Furthermore, Daiya (2024) concurred with Lanfranchi and Grassi (2022) that fintech application integration with machine learning and artificial intelligence compounds the mitigation of associated risks.

Related to cybersecurity is data privacy. Fintech integrates hard and soft information to customise new services offering, hence the competition with traditional banks who relied on one set of information. Information harvesting from different sources can entail unauthorised access or potential misuse (Fischli, 2024; Hua & Huang, 2021; Goddard, 2017). Due to weak or no data protection regulations in many countries, enactment of data protection mechanisms is required. The General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) for the European Union can serve as the data protection framework for countries to customize. Without the legal data framework, consumer trust can be eroded and expose the sector to financial and legal penalties among others.

In some countries, sharing personal details infringes on privacy rights (Bakare, Adeniyi, Akpuokwe, and Eneh, 2024; Christie, 2018). The biometric identification system adopted in India, Aadhaar was legally challenged on data privacy issues. Since the collation of data was being done by third party. Biometric information on the Aadhar system was open to abuse through fraud and misuse (Sadhya & Sahu, 2024; Martin, 2021; Abraham, et al., 2017). In 2017, the Supreme Court of India agreed that the privacy rights have been infringed but failed to rule on the constitutionality of case brought before the courts. This shows that country laws and regulations, culture and religion can be a hindrance to uniform global implementation of data standards.

Existence of disharmony continues to present challenges to banks, regulators and academics on the need to find common ground to the betterment of the financial services sector (Ofoeda. et al, 2022; Heller, 2017). Likewise, the advent of blockchain technology can aid in resolving these challenges. Similarly, data privacy issues are impediments to blockchain technology which is imminent (Al-Tawil, 2023). Simplification of the internal process by overcoming data issues can shift regulations to data-based regulations.

2.3.2. Regulatory and Compliance Risk

Fintech's rapid growth has resulted in regulations lagging, posing serious risk to regulatory compliance. These regulatory gaps together with limited fintech related regulations worldwide create an uncertain environment threatening financial stability (Khazratkulov, 2023; Lanfranchi and Grassi, 2022; Ryu, 2018). Additionally, the cross-border nature of fintech complicates harmonisation of regulations. Nonetheless, this regulatory arbitrage opens opportunities for the fintech, which exposes the wider financial services sector to inadequacy to address consumer protection and financial stability mandates.

Financial institutions have been able to enhance operational efficiency, improve customer service, and reach a wider audience by integrating innovative technologies such as blockchain, artificial intelligence, and big data analytics (Obeng, Iyelolu, Akinsulire, and Idemudia, 2024). But these developments have also presented emerging challenges on current and traditional regulatory mandates of consumer protection and financial stability. In the same vein, Fintech brought about by new financial products, digital payment methods, and decentralized finance (DeFi) platforms, all of which frequently function outside of traditional financial regulatory framework. As FinTech solutions move across global and jurisdictional boundaries, regulatory compliance in areas like data protection, know your customer (KYC) regulations, and anti-money laundering (AML) has grown increasingly complex. In the digital era the know your customer (KYC) principle is being transformed to know your data (KYD) (Velez, 2024; Ismayilov & Kozarević, 2023).

Akartuna et al. (2022) posits that cryptocurrencies facilitate money laundering and illicit transactions due to their anonymity and decentralized nature, necessitating the development of targeted regulatory measures. Money laundering risks are compounded by the accessibility of fintech platforms, which allow criminal actors to create false identities and obscure transactional trails, undermining efforts to combat financial crimes (Ismaeel, 2024; Ajdini, 2024; Nazzari, 2023).

Haralayya (2024) assert that regulatory frameworks need to change considering fintech's innovative nature while maintaining financial stability, market integrity, and consumer protection. Thus, there is need for regulation paradigm shift which strikes a balance between innovation and risk management. Also, regulators should be proactive by encouraging incorporation of technology into the regulatory process such as Regtech and SupTech and promote innovation by testing the new advances in a controlled environment (regulatory sandboxes).

Prudential regulations have become the cornerstone of post 2007/8 GFC which require massive data sets to be able to address financial stability mandate (Schiavo, 2022). Regulators need to make informed decisions; hence they need to adapt to technological enabled solutions and have collaborative partnerships (Kuchina, 2024).

2.3.3. Operational Risk

Operational risk is the possibility of suffering a loss because of weak or inadequate internal procedures, personnel, systems, or other external factors. This type of risk arises from several factors such as human error, failed processes and systems, and natural disasters. All these factors can lead to reputational damage and financial losses. In the financial services sector with the incorporation of fintech exposes the sector to systemic risks.

Operating challenges are rendered inefficiency by more dependence on modern technologies such as blockchain and artificial intelligence. This further complicates operating system integration and maintenance, especially for traditional banks with legacy systems.

Over the past 20 years, financial services have been the major user and purchaser of IT services globally (Tsingou, 2022; Arner & Barberis, 2015). Saksonova and Kuzmina-Merlino (2017) argued that legacy systems by financial institutions contribute to failure to innovate and adopt new technologies. Due to legacy issues, technology companies can exploit the opportunity through provision of cost effective and efficient ways to provide banking services. These have the competitive edge of being digitally centered. Resultantly, customers prefer better customer experience offered by technology companies to traditional banks.

Traditional banks have struggled to develop robust and efficient systems to tackle compliance issues due to legacy systems (Tsingou, 2022; Marous, 2018). Compliance based data requires data extraction from different sets within the banking system. Integration, algorithm-based data aggregation and automation can only be extracted using modern technologies.

Legacy systems make compliance expensive and very slow to get the requested information or data (Sreekanth & Kiran, 2024; Marous, 2018). For example, an online customer boarding process using legacy systems cost at least USD10 million and implemented over a two-year period (Cognizant, 2017). Comparably, using modern technologies the same costs USD0.3 million and is implemented over a three-month period. The FATF recommendation number 17 of money laundering requires that extreme caution be observed when integrating technology from third party sources with the banking functions (Gaviyau & Sibindi, 2023; Omar & Johari, 2015).

Ability to integrate risk functions is based on access to high quality data which is consistent across the organisation (Paramesha, Rane, and Rane, 2024; Mylavarapu, et al., 2016). In traditional banks this appears to be insurmountable due to legacy issues and compliance with internal data standards and practices. By resolving this challenge, this improves data quality and accuracy needed in supporting data driven decisions in real time.

Essentially, with the current scenario of huge data, solutions include effective data management and advanced analytics. Data analytics helps banks to identify risky patterns or unusual account activity thereby deterring any criminal intentions (Javaid, 2024; Alter, 2015). By utilising data, banks can have better insights into customer relationships. The relationship can be analysed through using massive data of current and historical transactions.

2.3.4. Ethical and Societal Risks

Digital technology has transformed the working culture in the financial services sector, as well as traditional financial institutions have been compelled to adapt the way they operate. By adapting to the new norms this embraces inclusion and diversity, encourage innovation and new ways of thinking, and foster transparency and higher levels of customer trust (Prastyanti, et al, 2023).

To offer a sufficient degree of clients’ protection, banks, as regulated entities, must also closely follow responsible credit practices in line with the applicable legislative framework (Sampat, Mogaji, and Nguyen, 2024). Unregulated entities such as fintechs engage in unethical or predatory lending practices with limited or no consumer protection mechanisms in place. Indeed, the greatest competitive advantage, which sets regulated banks apart from fintech entrants, is regulatory compliance and the integration of innovation and risk management within the banking systems (Macchiavello & Siri, 2022).

Emphasis has focused on how critical it is to solve these ethical issues to reestablish digital ethics in the fintech sector and guarantee that technological ideals like accountability, transparency, fairness, and access are realized (Aldboush, & Ferdous, 2023; Prastyanti, Rezi, & Rahayu, 2023). Prastyanti, et al (2023) argued that to build a sustainable future for FinTech and digital banking, a balance should be struck between technological innovation and moral behaviour.

Financial illiteracy among consumers further complicates the adoption of fintech services. Ozili (2021) notes that limited understanding of complex fintech products, particularly in developing economies, heightens the risk of misuse and exploitation. This underscores the need for comprehensive financial education initiatives to empower users and mitigate risks.

Procedure used for assessing consumer credit loan applications has changed due to the extensive use of econometric techniques and machine learning systems. While automated credit application analysis reduces the subjective nature of the decision-making process. On the other hand, machine learning which is based on historical decisions documented in financial institutions' datasets, frequently reinforces preexisting prejudices and biases (Garcia, Garcia, & Rigobon, 2024). The biases are based on elements such as ethnicity, sexual orientation, and gender among others.

Inherent biases in financial institutions' datasets can lead to discriminatory outcomes which undermines the financial inclusion goal envisioned by fintech (Lanfranchi and Grassi, 2022). To address the inherent biasness within the artificial intelligence driven financial service sector, regular algorithm audits should be conducted along with stakeholder collaboration (Chomczyk Penedo & Trigo Kramcsák, 2023).

3. Methodology

A bibliometric analysis approach using databases such as Scopus and Google Scholar with tools like VOS viewer and R has been adopted by many researchers due to its cross disciplinary information repository (Passas,2024; Doulani, 2020). Additionally, it provides an enhanced scholarly foundation to discover emerging scholarly trends. The research relied on the Scopus search database.

Scopus database was chosen as the database provides access to vast number of internationally recognized publishers and peer reviewed journals with a robust citation analysis and tracking tool among others (Chadegani, Salehi, Yunus, Farhadi, Fooladi, Farhadi, and Ebrahim, 2013; Bergman, 2012). The tracking tool aids in evaluating the significance and scope of research outputs by different researchers globally.

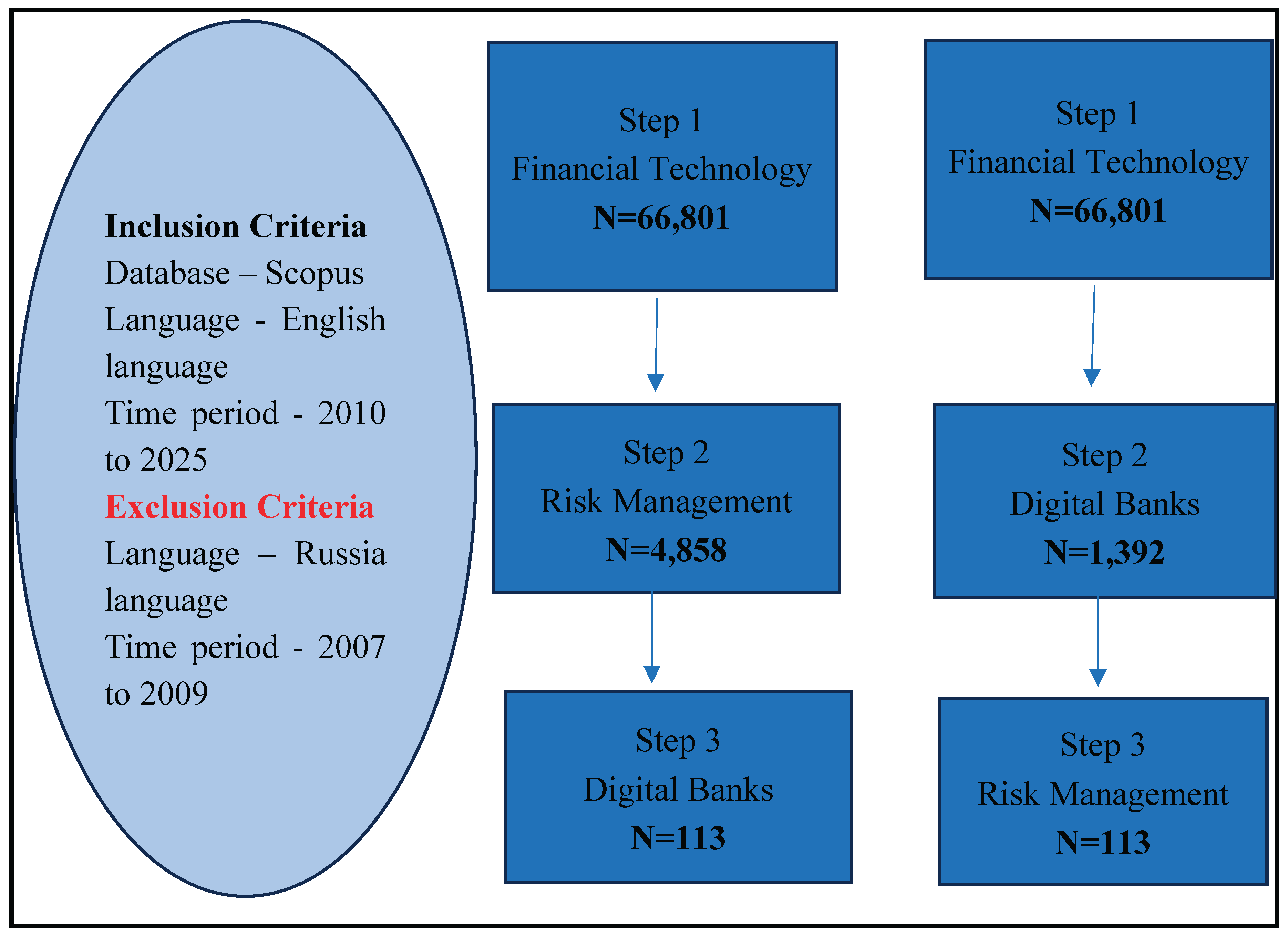

To gather the appropriate documents aligned to the research under study, two different search queries were applied which resulted in the same output of one hundred and thirteen (113) documents as shown in

Figure 4. These documents served as the primary source documents on the banking perspectives given the emergent risks in the fintech or digitalized environment. By adopting two different search queries, the aim was to minimize missing critical documents sources as database responds differently when full words or initials are used in searching. For instance, financial technology and fintech can result in different information sets though they are covering the same subject of financial technologies. Also banking and bank produces different information. Therefore, the search process remains iterative requiring carefully identifying the appropriate search string which produces desirable results.

The first search query was (TITLE-ABS-KEY-AUTH (financial AND technology) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (digital AND banks) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (risk AND management)) AND PUBYEAR > 2006 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND (EXCLUDE (LANGUAGE, “Russian”)). The initial query of financial technology had 66,801documents which were further confined to digital banks with 1,392 documents and risk management with 113 documents. The second search query (TITLE-ABS-KEY-AUTH (financial AND technology) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (risk AND management) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (digital AND banks)) AND PUBYEAR > 2006 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 AND (EXCLUDE (LANGUAGE, “Russian”)). The initial query of financial technology had the same documents as the first with 66,801 documents which was further limited to risk management with 4,858 documents and digital banks with 113 documents.

Documents published between the period 2007 to 2025 were analyzed with focus but not limited to dominant themes, citations, publication trends, research output linked to the country, discipline areas, and influential authors. The inclusion period was considered on the basis that the global financial crisis (GFC) started in 2007/8, and the aftermath saw a surge in financial technology innovations. Despite initial thoughts of including 2007 as start period, Scopus database limited the search to start from 2010 which indicates little or no related research articles for that prior period. In terms of language, documents written in English were considered with those in Russian language excluded.

4. Results and Discussions

Table 2 shows some of the descriptive statistics of the retrieved documents under study. These metrics are discussed in the next section.

4.1. Research Output by Year

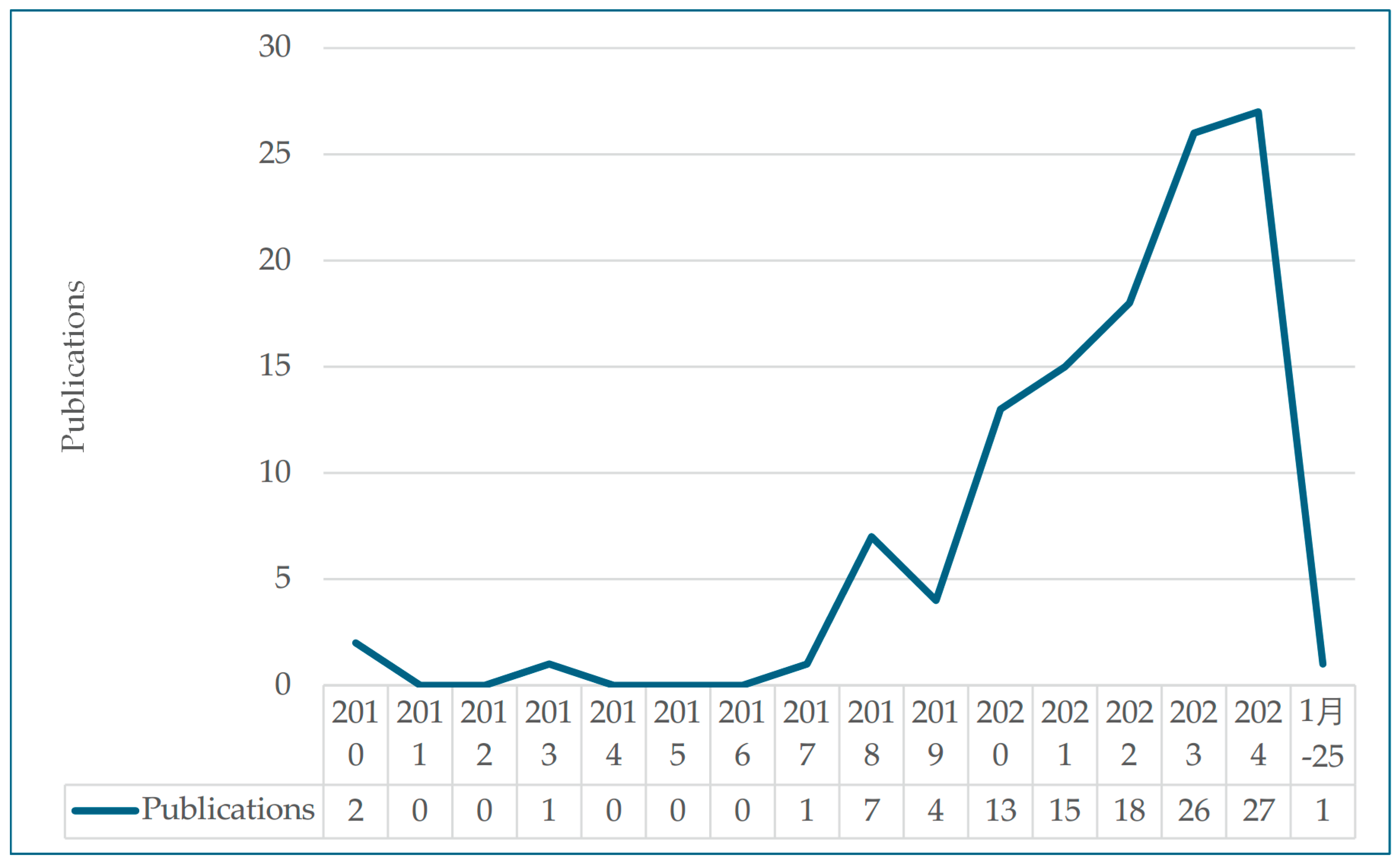

As shown in

Figure 5, of the one hundred and thirteen (113) research output retrieved during the said period, the majority were published in 2024, which accounted for 24% followed by 2023 which accounted for 23%. Notably, publication of research output within the confine of research query started from 2018 which showed a growing trend from that year to 2024. The plausible explanation being the growth and scrutiny of the subject under research as the financial services sector responds to the clarion call to evolve in terms of regulation, risk management, and consumer protection among others. The peaks especially after 2019 can be attributed to the COVID 19 induced restrictions of 2020 to 2021 which accelerated the shift towards digital banking. However, these opportunities underscored the importance of robust risk management frameworks as emergent risks arise. The findings also illustrate the financial technology research articles emerging period, even though GFC occurred in 2007/8.

4.2. Research Output by Geographical Distribution

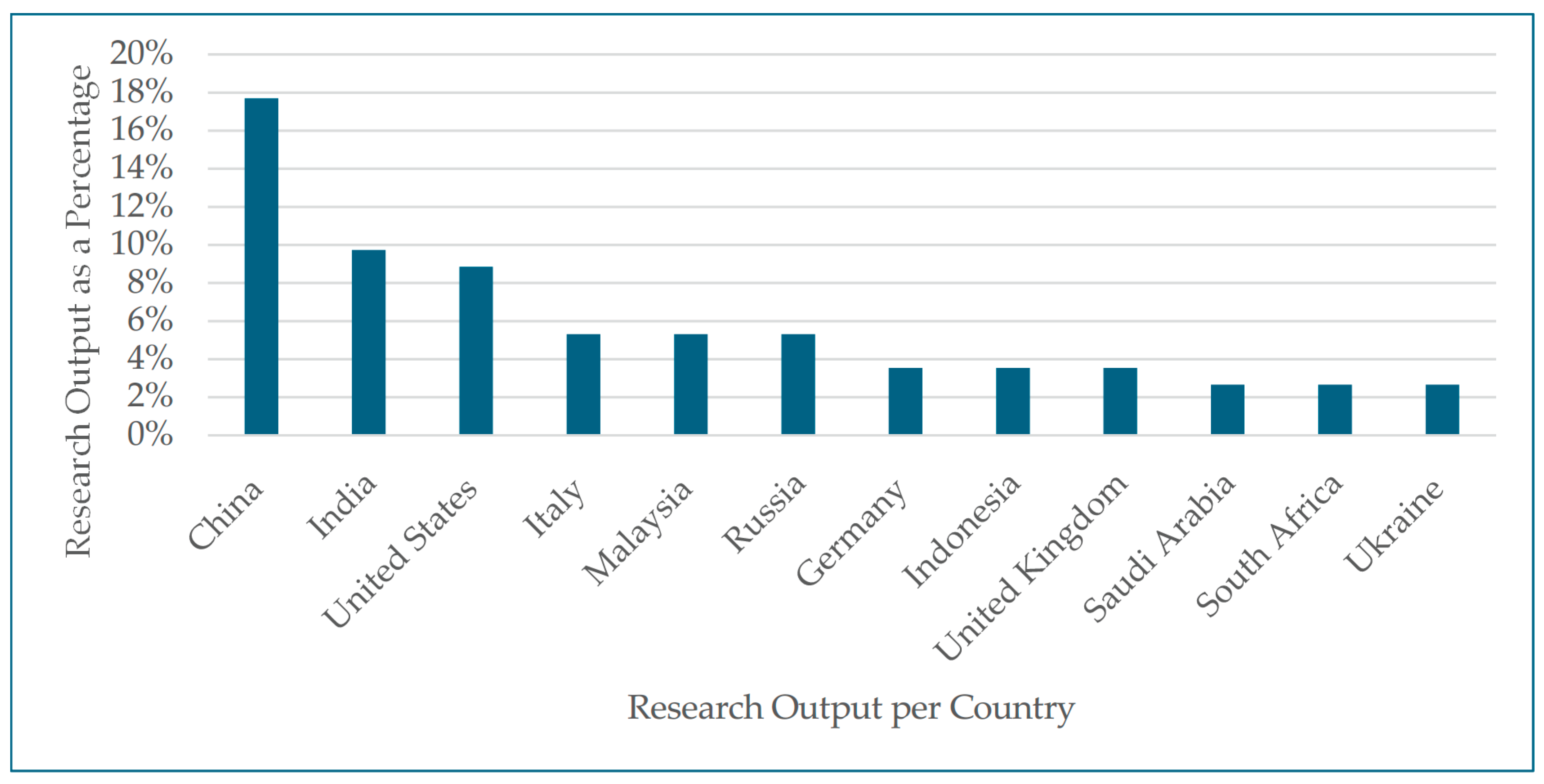

Of the research output and over the same period 2010 to 2024, the countries that dominated the scholarly output were China, followed by India and thirdly United States of America (USA). As shown in

Figure 5, the dominant countries are mainly in middle to upper income countries, except for India which is in the lower middle-income category. Despite India being classified in the lower middle-income category, the country is dominant in the financial inclusion subject.

Figure 6.

Publication by Country.

Figure 6.

Publication by Country.

Based on World Bank (2023) categorization High income countries are Russia, Germany, United Kingdom and United States of America. Moreover, Upper middle income countries being China, Malaysia, Indonesia, South Africa and Ukraine. The results indicate the growth of Bigtechs and their countries of origin who are dominant in the field of information and communication technology infrastructure development which have extended into the financial services sector. This underscores the collaborations driven in Banking 4.0 and 5.0 evolution.

BigTechs, also known as Tech Giants, are technological companies who leverage their data analytics capabilities, vast customer base and brand recognition to offer financial services (Armstrong, Balitzky and Harris, 2020). Offered services include payment and credit services. For instance, China has BATX - Baidu, Alibaba (Alipay), Tencent (WeChat Pay), and Xiaomi while the USA`s big tech players include Google, Amazon (Amazon Pay), Microsoft, Apple (Apple pay) and Meta (Meta pay). Furthermore, the BATX has a bigger presence in the domestic financial markets (Dziawgo, 2021). Bigtechs gather information from their financial and non-financial operations and use customer data stored in various areas of their company like social media.

Bains, Sugimoto, and Wilson (2022) opine that to host essential IT systems such as cloud-based services, which boost security and efficiency, incumbent financial businesses have become more dependent on BigTech companies. Consequently, BigTechs' exponential growth in the financial services industry, together with their connections with other financial service companies, gives rise to new avenues for systemic risk.

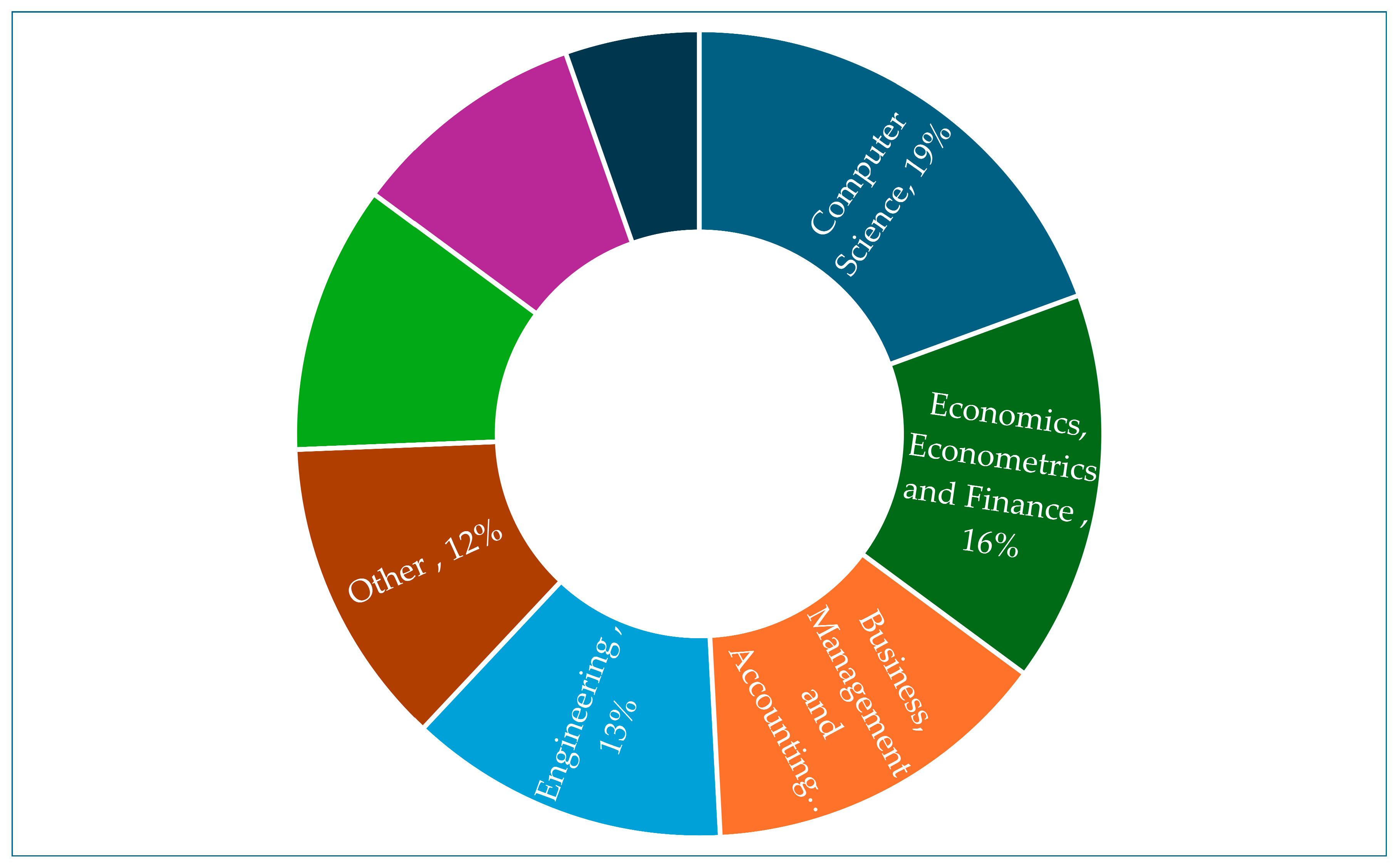

4.3. Discipline Area

Figure 6.

Publication by Discipline Area.

Figure 6.

Publication by Discipline Area.

The area of discipline indicates the extent of growth of the subject under discussion. In this paper, the subject most appeared in the Computer Science discipline with 19% followed by Economics, Econometrics and Finance with 16% while Business, Management and Accounting had 14%. Notably, the subject of financial technology, digital banks and risk management is related to finance discipline. However, with the research output mainly in the Computer Science discipline this indicates the inter-disciplinary nature of the subject.

Primarily, Fintech falls under the finance subject discipline though Fintech is a blend of finance, technology and computer science due to the reliance on algorithms, software development and digital platforms (Liang, 2023; Stulz, 2019). Taherdoost (2023) concurred with Das (2019) that Fintechs emerged because of significant advancements in computing technology, econometrics, mathematical and statistical disciplines. Indeed, fintech is inter-disciplinary. Interdisciplinary research is generative process of harvesting and leveraging on the skills expertise of the various parties linked to the research (Duan, 2024; Klein, 2008).

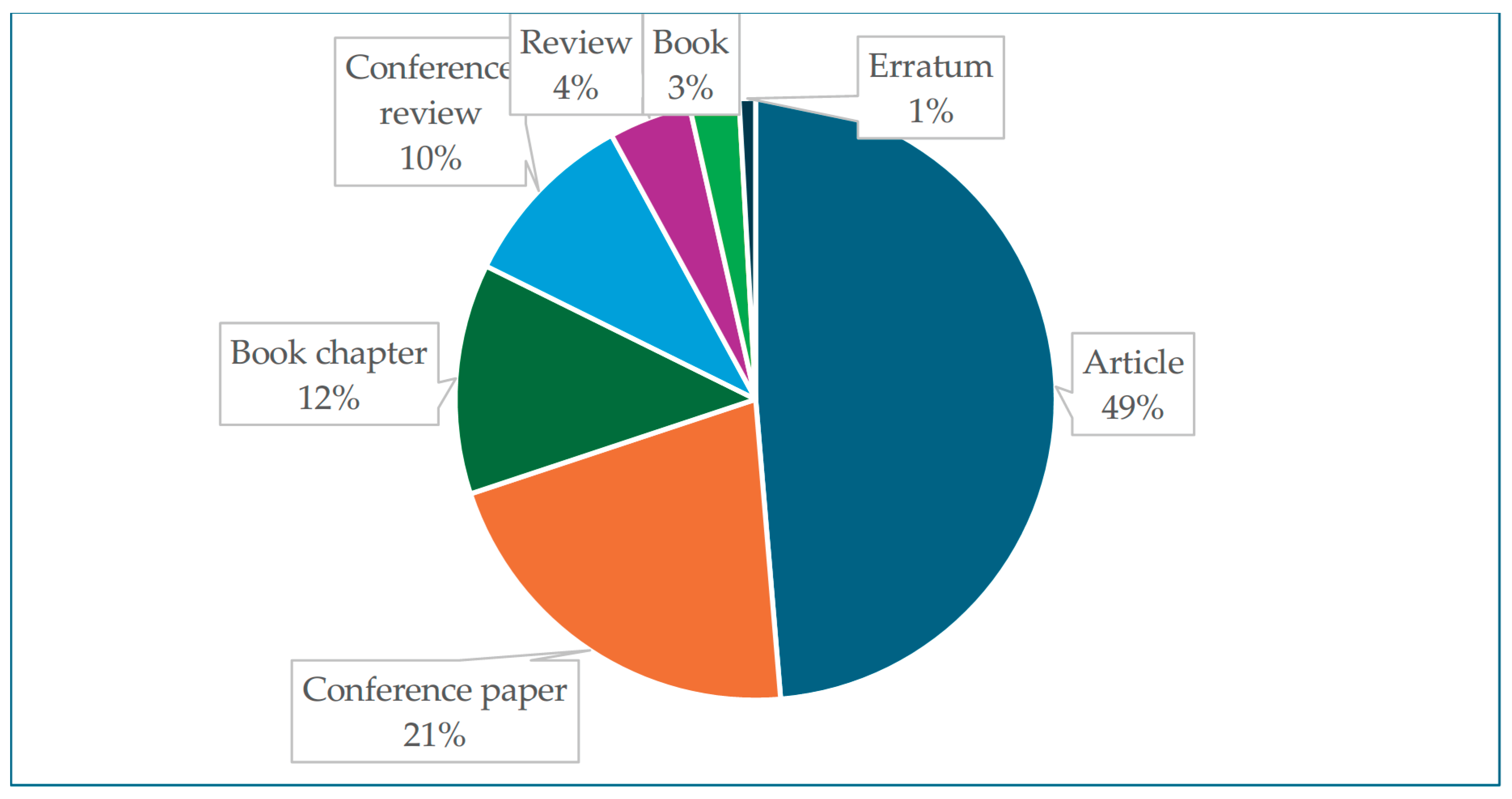

4.4. Publication by Type

Figure 7.

Research Output by Type.

Figure 7.

Research Output by Type.

Research output is published in the form of articles, conference papers, book chapters, and books among others. In this paper, the research output is mainly produced in the form of Articles which accounted for 49%, followed by Conference paper with 21% and Book Chapter accounting 12%. This indicates that research outputs by academics are being shared through Articles in internationally recognized journals and acceptable conferences. Publishing research output remains as a powerful way to share findings, gain professional recognition, open collaboration opportunities, and contribute to the advancement of knowledge.

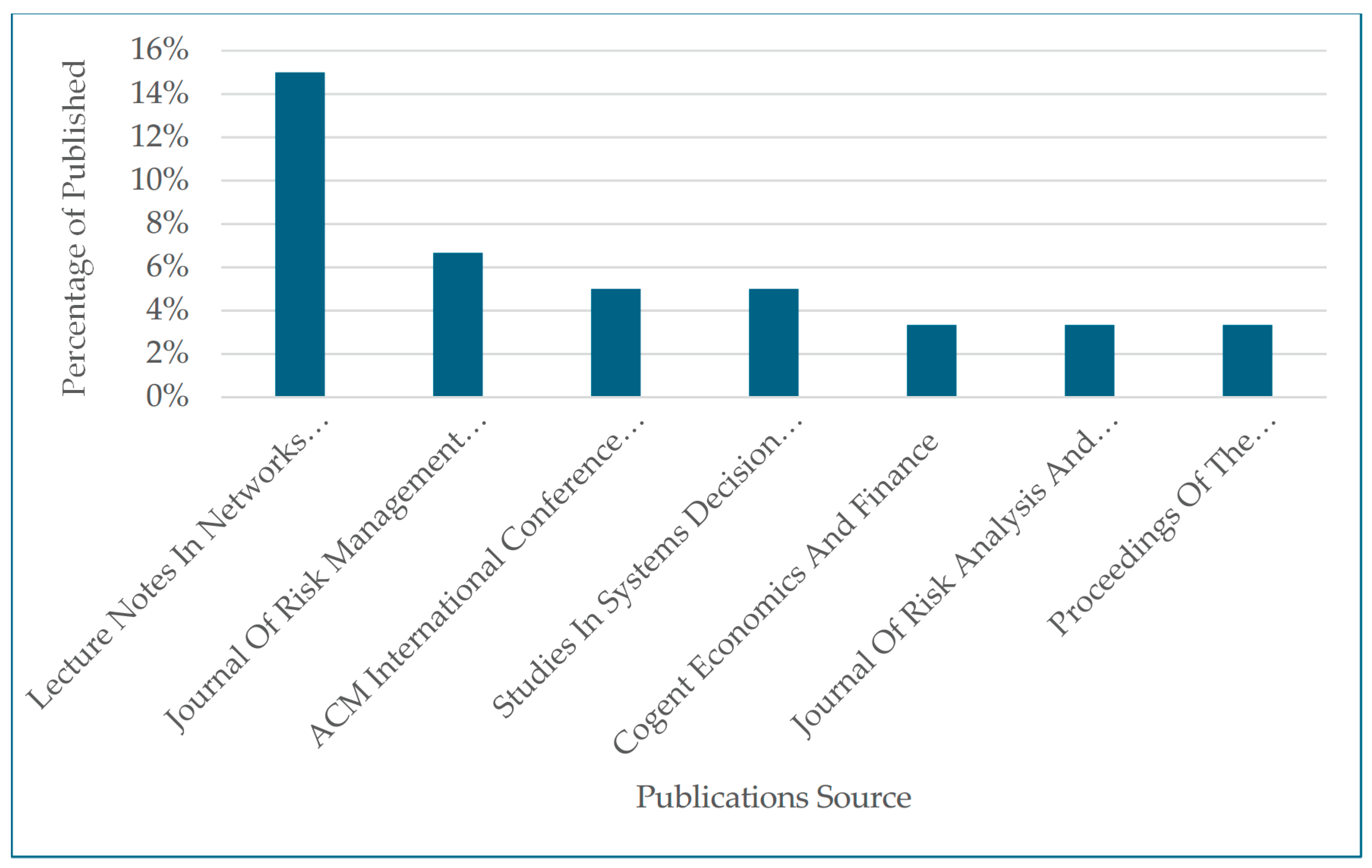

4.5. Publication by Source

Figure 8 shows the publications sources used by the researchers. Over the period under study, the top three publishers used by researchers were Lectures Notes in Networks and Systems with 15% followed by Journal of Risk Management in Financial Institutions with 7% and these two - ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, and Studies in Systems Decision and Control in the third-place accounting for 5% each. These findings support the earlier assertion on the interdisciplinary nature of the subject as it cuts across various disciplines. Additionally, publishers of choice grow with time which assists researchers to evaluate the research output significance.

SJR assists researchers in identifying influential journals in a specified discipline. Also, it assesses the quality of journal citations (Jain, Khor, Beard, Smith, and Hing, 2021). SNIP assists researchers in comparing journals more accurately, especially those within the interdisciplinary research. Collectively these metrics assist in researcher`s decision making on which publication to choose and potential impact based on the previous metrics. As shown in

Table 3, the journals have relatively low SJR and SNIP scores which indicate the interdisciplinary nature which can entail citations as not domiciled in one field. Also, the subject is a niche area which is still emerging and growing.

4.6. Research Output – Citation Metrics

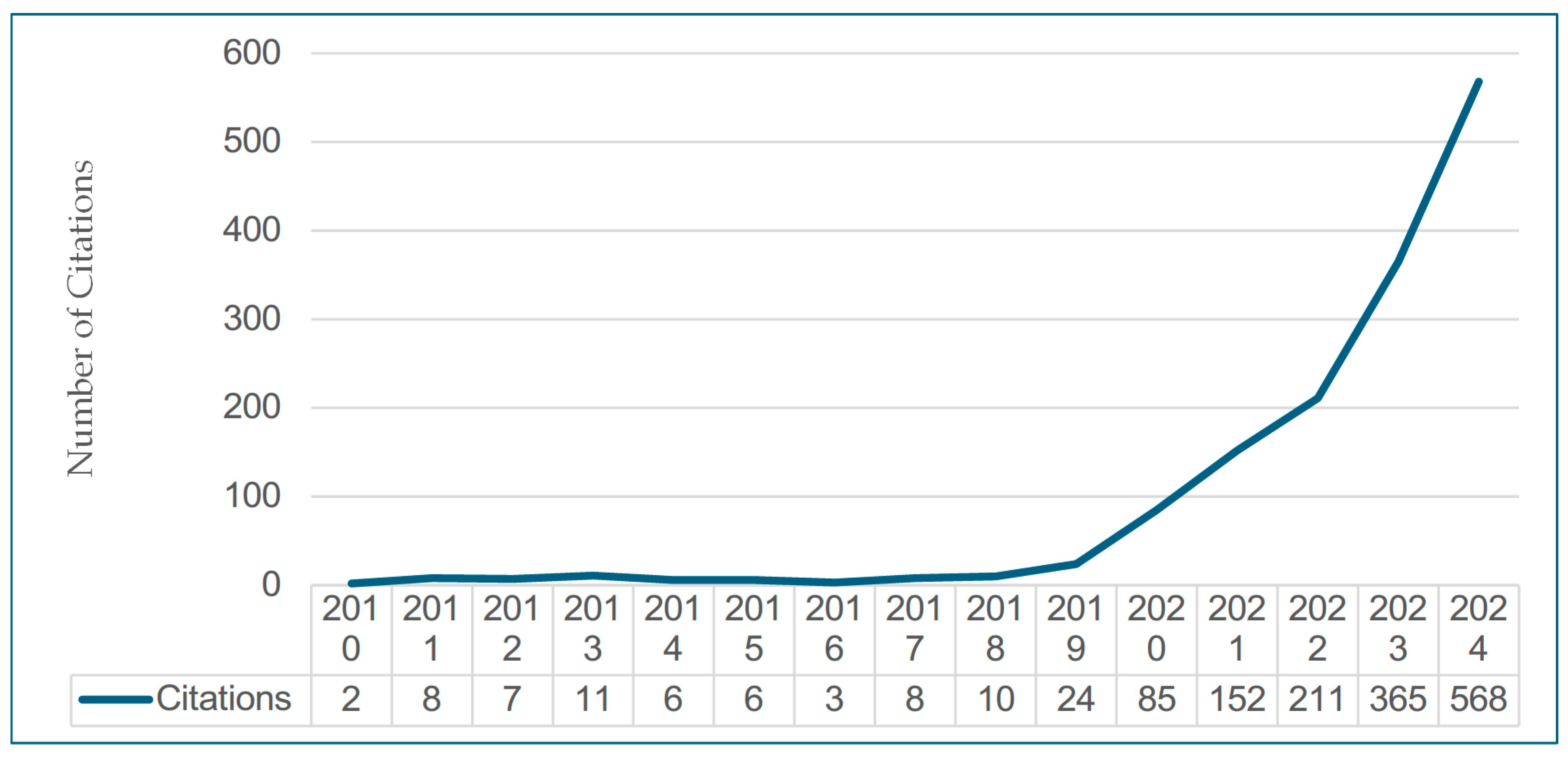

Citations indicate the relevance and importance of the published document within the academic community. Over the period 2010 to 2024, a total of 1,466 citations were recorded as shown in

Figure 9. Of the citations, 2024 recorded the highest citations of 568 followed by 2023 with 365 citations and 2022 with 211 citations. In addition, they had an overall h-index of 15, indicating the strength and relevance of the publications.

Of the publications, the five most prominent publications based on the citations are shown in

Table 4. The research output entitled Blockchain technology for enhancing supply chain resilience, by Min H had the highest citations of 622 with a field weighted citation impact (FWCI) of 24.26.

On the second place was the output entitled A review of Blockchain Technology applications for financial services by Javaid M and others had 134 citations with FWCI of 6.24. On the third place was entitled Technologies of compliance: Risk and regulation in a digital age by Bamberger, K.A with 119 citations and FWCI of 9.96.

Fourthly the research entitled Supply chain financial service management system based on block chain IoT data sharing and edge computing by Wang, L and others had 54 citations with FWCI of 7.07. Lastly, output entitled Technology Quality Management of the Industry 4.0 and Cybersecurity Risk Management on Current Banking Activities in Emerging Markets – The Case in Vietnam by Thach, N.N and others had 40 citations with FWCI of 2.67.

Of the top five cited articles shown in

Table 4, it is of particular note that the higher FWCI of 24.26 observed on the first article focuses on Blockchain issues within the supply chain framework. However, this article was included in this research query indicating the interdisciplinary nature of the research query. This observation confirms the findings in

Figure 6 where the subject discipline was shared with Computer Science, Economics and Business Management. Also cuts across all the disciplines as observed by Liang (2023) and Stulz (2019).

Figure 10.

Emergent Key Words in Top Cited Publications.

Figure 10.

Emergent Key Words in Top Cited Publications.

The emergent key words of the top five cited published was risk management with the others such as data sharing, virtual currency, service management and cloud technology being emerging. This indicates a growing trend towards addressing the risk management aspects in the fintech or digitalized environment.

4.7 Geographical Collaboration Metrics

Collaboration facilitates the exchange of knowledge and skills among researchers. This thereby enhances learning and development of better and enhanced methodological research approaches.

Table 5 shows that the majority, 29.5%, had institutional collaboration only with 22.3% being single authored with no collaboration and 19.6% had national collaboration only. Notably single authored publication had higher metrics such as 809 citations and 32.4 citations per publication with a 2.23 FWCI. This shows as a niche area or emerging subject which is interdisciplinary, collaborations and FWCI is still in the novel stage. As more and more interest is generated, expectations are high that more joint research projects and collaborations will be recorded.

Duan (2024) argued that studies involving collaboration are crucial for academic advancement because they enable researchers to pool their resources and expertise to produce novel concepts that might not have been achievable through individual effort. As a result, individuals may work more productively and provide better outcomes.

4.8. Key Phrase Analysis

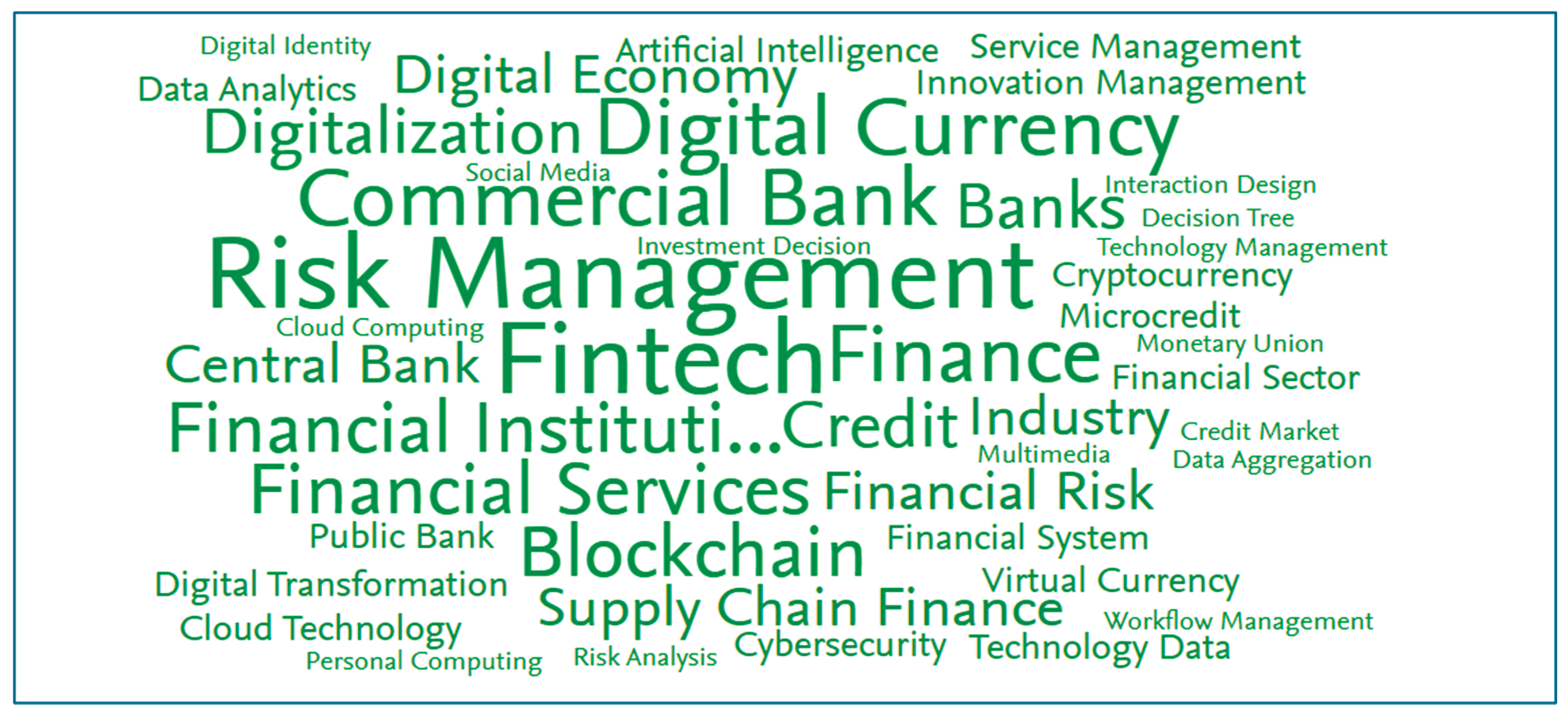

The key phrases for the study are shown in

Figure 11. The key words for this study are risk management, fintech, commercial banks, finance, blockchain and digital currency. Further to interpreting these results, the relevance scores for the key phrases are shown in

Table 6. The relevance score ranges from 0 to 1, showing the strength of relevance from 0 the lowest to 1 being the highest. In this study the most relevant were risk management and fintech with a highly strong relevant score of 1 followed by finance, digital currency and commercial bank with a strong score of 0.75. On the third, with a relatively moderate strong score of 0.63 were financial institution and block chain.

Over the period 2019 to 2024, the top five key phrases growth due to research and increased reference revealed growth ranging from 100% to 500%. As shown in

Table 7, risk management had the highest growth at +500% with financial institutions coming second with +400% and banks being third with +250%. On the fourth was digital currency with +200% and fifth being block chain with +100%.

These findings indicate that risk management continues to dominate and emerge within banks or financial institutions. Evidently, this can be an indicator of the risky nature of the financial services sector due to the regulatory environment they are accustomed to. Also, the domination reflects the banking sector`s shift towards technology-driven models. Hence, the increase in digital banks with some collaborating with fintech to offer seamless customer service. This calls for appropriate regulatory responses which do not stifle innovation.

5. Conclusion

The bibliometric analysis undertaken reveals research on emerging risks in the era of fintech-driven digital banking and banks. Key findings revealed importance of addressing risks such as data privacy, cybersecurity, and blockchain which are the study`s key phrases. Also, the subject is interdisciplinary as shown with the research output in various disciplines. Research output is inclined to countries where Bigtechs are domiciled. This indicates the growth of Bigtechs and their countries of origin who are dominant in the field of information and communication technology infrastructure development which have extended into the financial services sector. This underscores the collaborations driven in Banking 4.0 and 5.0 evolution.

For financial institutions, the shift from traditional banking to digital banking marks an important industry transformation. For this reason, digital banks are being licensed under strict regulations while the fintech environment has forced traditional banks to be innovative and adaptable. Despite emerging risks evolving, a paradigm shift is needed by stakeholders in the financial ecosystem. Considerably, banks which embrace the fintech operating environment remain well-positioned to prosper in the rapidly evolving financial environment.

To mitigate emerging risks and foster innovation especially in the Banking 5.0, collaboration involving policymakers, stakeholders and academics remains essential. Future studies should concentrate on creating robust risk management frameworks that address ethical issues associated with financial technologies. In the fintech era, this can ensure a robust and inclusive digital financial services ecosystem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.G. and J.G; methodology, W.G. and J.G; software, W.G.; validation, W.G. and J.G.; formal analysis, W.G.; investigation, W.G.; resources, W.G.; data curation, W.G.; writing—original draft preparation, W.G.; writing—review and editing, J.G; visualization, W.G.; supervision, J.G; project administration, W.G.; funding acquisition, J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of South Africa.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abraham, K., Haltiwanger, J., Sandusky, K. and Spletzer, J. (2017): Measuring the gig economy: Current knowledge and open issues: Measuring and Accounting for Innovation in the 21st Century.

- Agoba, A.M., Sare, Y.A., Anarfo, E.B. and Tsekpoe, C. (2023): The push for financial inclusion in Africa: Should central banks be wary of political institutional quality and literacy rates?: Politics & Policy, 51(1), pp.114-136. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.(2022): Rise of Decentralised Finance-Reimagining Financial Regulation: Indian JL & Tech., 18, p.1.

- Ajdini, V. (2024): Abuse of Cryptocurrencies as a modern from of Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism: Vizione, (42).

- Akartuna, E.A., Johnson, S.D. and Thornton, A.E. (2022): The money laundering and terrorist financing risks of new and disruptive technologies: a futures-oriented scoping review: Security Journal, p.1. [CrossRef]

- Aldboush, H. H. H., & Ferdous, M. (2023). Building Trust in Fintech: An Analysis of Ethical and Privacy Considerations in the Intersection of Big Data, AI, and Customer Trust. International Journal of Financial Studies, 11(3), 90. [CrossRef]

- Aljudaibi SA, Amuda YJ. (2024): Legal framework governing consumers’ protection in digital banking in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development. 8(8): 5453. [CrossRef]

- Allen, F., Gu, X. and Jagtiani, J. (2021): A survey of fintech research and policy discussion: Review of Corporate Finance, 1, pp.259-339.

- Al-Tawil, T.N. (2023), "Anti-money laundering regulation of cryptocurrency: UAE and global approaches": Journal of Money Laundering Control, Vol. 26 No. 6, pp. 1150-1164. [CrossRef]

- Alter, D. (2015): How to lighten community bank`s AML compliance load. American Banker.

- Aras, A. and Büyüközkan, G. (2023): Digital transformation journey guidance: A holistic digital maturity model based on a systematic literature review. Systems, 11(4), p.213. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong Patrick, Balitzky Sara and Harris Alexander (2020): Financial stability and investor protection - BigTech – implications for the financial sector: ESMA Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities, Volume 1. pg 48-59.

- Arner, D.W. and Barberis, J. (2015): FinTech in China: from the shadows?. The Journal of Financial Perspectives.

- Auronen, L. (2003): Asymmetric information: theory and applications. In Seminar of Strategy and International Business as Helsinki University of Technology (Vol. 167, pp. 14-18).

- Awaliyah, Tuti & Safitri, Nurul & Hartaty, Sri & Felani, Fifin & Judijanto, Loso. (2023): The Impact of Financial Technology Innovation on Banking Service Transformation: A Case Study in the FinTech Industry: Global International Journal of Innovative Research. Vol 1. pp 306-313.

- Bakare, S.S., Adeniyi, A.O., Akpuokwe, C.U. and Eneh, N.E. (2024): Data privacy laws and compliance: a comparative review of the EU GDPR and USA regulations: Computer Science & IT Research Journal, 5(3), pp.528-543.

- Bank Negara Malaysia (2022): Five successful applicants for the digital bank licences: https://www.bnm.gov.my/-/digital-bank-5-licences accessed 30 January 2025.

- Berghaus, S and Back (2016): The Fuzzy Front-end of Digital Transformation: Three Perspectives on the Formulation of Organizational Change Strategies. In Proceedings of the 29th Bled eConference: Digital Economy, Bled, Slovenia, 19–22 June 2016; pp. 129–144.

- Bergman, S. (2012): Integral operators in the theory of linear partial differential equations: Springer Science & Business Media, Vol. 23.

- Bhattacharjee, Dr & Srivastava, Dr & Mishra, Prof & Adhav, Dr & Singh, Mrs. (2024): The Rise of Fintech: Disrupting Traditional Financial Services: Educational Administration: Theory and Practice. 30. 89-97.

- Bhattacharya, S. and Thakor, A.V. (1993): Contemporary banking theory: Journal of financial Intermediation, 3(1), pp.2-50. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R., Sahab, P., Paulc, G. and Sahad, A.K., (2024): Regulatory outlook in fintech: A review: International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 5, pp.7100-7108.

- Boot, A.W. and Marinč, M.(2008): The evolving landscape of banking: Industrial and corporate change, 17(6), pp.1173-1203.

- Bunea, S., Kogan, B. and Stolin, D., (2016): Banks versus FinTech: At last, it's official: Journal of Financial Transformation, 44, pp.122-131. [CrossRef]

- Chadegani, A. A., Salehi, H., Yunus, M. M., Farhadi, H., Fooladi, M., Farhadi, M., & Ebrahim, N. A. (2013): A Comparison between two main academic literature collections: Web of Science and Scopus databases: Asian Social Science, 9(5), 18–26.

- Chanias, S. and Hess, T. (2016): How digital are we? Maturity models for the assessment of a company’s status in the digital transformation. Management Report/Institut für Wirtschaftsinformatik und Neue Medien, (2), pp.1-14.

- Chomczyk Penedo, A. and Trigo Kramcsák, P., (2023): Can the European Financial Data Space remove bias in financial AI development? Opportunities and regulatory challenges: International Journal of Law and Information Technology, 31(3), pp.253-275. [CrossRef]

- Chougule, P.S. and Dudekula, C.S. (2024): Banking in the Future: An Exploration of Underlying Challenges. In The Adoption of Fintech (pp. 160-191): Productivity Press.

- Cognizant (2017): Digital Customer Due Diligence: Leveraging Third-Party Utilities, s.l.: Cognizant.

- D’Andrea, A. and Limodio, N. (2024): High-speed internet, financial technology, and banking: Management Science, 70(2), pp.773-798. [CrossRef]

- Daiya, H. (2024): AI-Driven Risk Management Strategies in Financial Technology: Journal of Artificial Intelligence General science (JAIGS) ISSN: 3006-4023, 5(1), pp.194-216. [CrossRef]

- Del Gaudio, B.L., Porzio, C., Sampagnaro, G. and Verdoliva, V. (2021): How do mobile, internet and ICT diffusion affect the banking industry? An empirical analysis: European Management Journal, 39(3), pp.327-332. [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, H., Popescu, C. and Iddagoda, A. (2023): A Bibliometric Analysis of Financial Technology: Unveiling the Research Landscape: FinTech, 2(3), pp.527-542. [CrossRef]

- Doulani, A. (2020): A bibliometric analysis and science mapping of scientific publications of Alzahra University during 1986–2019: Libr. Hi Tech 2020, 39, 915–935. [CrossRef]

- Duan, C. (2024): Analyses of Scientific Collaboration Networks among Authors, Institutions, and Countries in FinTech Studies: A Bibliometric Review: FinTech, 3(2), 249-273. [CrossRef]

- Duran, R.E. and Griffin, P. (2021): Smart contracts: will Fintech be the catalyst for the next global financial crisis?: Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance, 29(1), pp.104-122. [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, H. (2023): Interactivity in the electronic press and its impact on the readability of the paper press: The Egyptian Journal of Media Research, 2023(84), pp.2037-2062.

- 38. FATF, 2015.

- Fischli, R. (2024): Data-owning democracy: Citizen empowerment through data ownership: European Journal of Political Theory, 23(2), pp.204-223. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.C.B., Garcia, M.G.P. & Rigobon, R. (2024): Algorithmic discrimination in the credit domain: what do we know about it?: AI & Soc 39, pp2059–2098. [CrossRef]

- Gaviyau, W. and Sibindi, A.B (2023): Anti-money laundering and customer due diligence: empirical evidence from South Africa: Journal of Money Laundering Control, 26(7), pp.224-238. [CrossRef]

- Giannakoudi, S. (1999): Internet banking: the digital voyage of banking and money in cyberspace: Information and Communications Technology Law, 8(3), pp.205-243. [CrossRef]

- Goddard, M. (2017): The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR): European regulation that has a global impact: International Journal of Market Research, 59(6), pp.703-705. [CrossRef]

- Gökalp, E. and Martinez, V. (2022): Digital transformation maturity assessment: development of the digital transformation capability maturity model: International Journal of Production Research, 60(20), pp.6282-6302. [CrossRef]

- Haddad, C. and Hornuf, L. (2019): The emergence of the global fintech market: Economic and technological determinants: Small business economics, 53(1), pp.81-105. [CrossRef]

- Hallett, T. and Hawbaker, A., (2021): The case for an inhabited institutionalism in organizational research: Interaction, coupling, and change reconsidered: Theory and Society, 50(1), pp.1-32. [CrossRef]

- Haralayya, B. (2024): Fintech Disruption: Evaluating the Implications For Traditional Financial Institutions And Regulatory Frameworks: Educational Administration: Theory And Practice, 30(5), pp.6783-6792.

- Heller, N. (2017): Estonia, the digital republic: The New Yorker, 18(25).

- Henriette, E.; Feki, M.; Boughzala, I. (2015): The Shape of Digital Transformation: A Systematic Literature Review: In Proceedings of the 9th Mediterranean Conference on Information Systems (MCIS 2015), Samos, Greece, 3–5 October 2015; pp. 1–13.

- Hrynko, P (2019): Improvement of the digital transformation strategy of business on the basis of digital technologies: Eureka Soc. Humanit. 2019, 6, 10–18. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J. S. (2018): The impact of fintech on banking industries: Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce,23(2), 1-1.

- Hua, X. and Huang, Y. (2021): Understanding China’s fintech sector: development, impacts and risks: The European Journal of Finance, 27(4-5), pp.321-333. [CrossRef]

- Ismaeel, S., (2024): Money Laundering: Impact on Financial Institutions and International Law-A Systematic Literature Review: Pakistan Journal of Criminology, 16(431).

- Ismayilov, N. and Kozarević, E. (2023): Changing financial system architecture under the influence of the fintech market: A literature review: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 28(2), pp.93-102. [CrossRef]

- Iyelolu, T.V., Agu, E.E., Idemudia, C. and Ijomah, T.I., (2024): Legal innovations in FinTech: Advancing financial services through regulatory reform: Finance & Accounting Research Journal, 6(8), pp.1310-1319.

- Jain, A., Khor, K.S., Beard, D., Smith, T.O. and Hing, C.B. (2021): Do journals raise their impact factor or SCImago ranking by self-citing in editorials? A bibliometric analysis of trauma and orthopaedic journals: ANZ Journal of Surgery, 91(5), pp.975-979. [CrossRef]

- Javaid, H.A., (2024): Improving Fraud Detection and Risk Assessment in Financial Service using Predictive Analytics and Data Mining: Integrated Journal of Science and Technology, 1(8).

- Khazratkulov, O., (2023): Navigating the Fin-Tech Revolution: Legal Challenges and Opportunities in the Digital Transformation of Finance: Uzbek Journal of Law and Digital Policy, 1(1).

- Kotarba, M (2018): Digital transformation of business models: Found. Manag. Vol 10, 123–142.

- Kuchina, Y.O(2024): Problems and challenges of regulation of anonymous fintech: Образoвание. Наука. Научные кадры, (1), pp.176-189.

- Kurmann, P. and Arpe, B (2019): Managing Digital Transformation: How Organizations turn Digital Transformation into Business Practices: Master’s Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

- Grassi, L. and Lanfranchi, D., (2022): RegTech in public and private sectors: the nexus between data, technology and regulation: Journal of Industrial and Business Economics, 49(3), pp.441-479. [CrossRef]

- Macchiavello, E. and Siri, M. (2022): “Sustainable finance and fintech: can technology contribute to achieving environmental goals? A preliminary assessment of ‘green fintech’ and ‘sustainable digital finance’”: European Company and Financial Law Review, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 128-174.

- Marous, J. (2018): The Future of Banking: Fintech or Techfin?. Forbes.

- Megargel, A., Shankararaman, V. and Reddy, S.K. (2018): Real-time inbound marketing: A use case for digital banking: In Handbook of Blockchain, Digital Finance, and Inclusion, Volume 1 (pp. 311-328). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Mehdiabadi, A.; Tabatabeinasab, M.; Spulbar, C.; Yazdi, A.K.; Birau, R (2020): Are We Ready for the Challenge of Banks 4.0? Designing a Roadmap for Banking Systems in Industry 4.0: Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2020, 8, 32. [CrossRef]

- Metzger, J. and Paulowitz, T. (2018): Seeking common legal entity standards to facilitate cross-border payments: Journal of Payments Strategy & Systems, 12(4), pp.365-370.

- Minh, H.P. and Thanh, H.P.T. (2022): Comprehensive Review of Digital Maturity Model and Proposal for A Continuous Digital Transformation Process with Digital Maturity Model Integration: IJCSNS, 22(1), p.741. [CrossRef]

- Monetary Authority of Singapore (2020): MAS Announces Successful Applicants of Licences to Operate New Digital Banks in Singapore: https://www.mas.gov.sg/news/media-releases/2020/mas-announces-successful-applicants-of-licences-to-operate-new-digital-banks-in-singapore accessed 29 January 2025.

- Nazzari, M (2023): From payday to payoff: Exploring the money laundering strategies of cybercriminals: Trends in Organized Crime, pp.1-18.

- Noreen, U., Shafique, A., Ahmed, Z., & Ashfaq, M. (2023): Banking 4.0: Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Banking Industry & Consumer’s Perspective: Sustainability, 15(4), 3682. [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, A. and Silkoset, R. (2023): Sustainable development and greenwashing: How blockchain technology information can empower green consumers: Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(6), pp.3801-3813. [CrossRef]

- Obeng, S., Iyelolu, T.V., Akinsulire, A.A. and Idemudia, C. (2024): The transformative impact of financial technology (FinTech) on regulatory compliance in the banking sector: World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 23(1), pp.2008-2018. [CrossRef]

- Ofoeda, I., Agbloyor, E.K., Abor, J.Y. and Osei, K.A. (2022): Anti-money laundering regulations and financial sector development: International Journal of Finance & Economics, 27(4), pp.4085-4104. [CrossRef]

- Omar, N. and Johari, Z.A., 2015. An international analysis of FATF recommendations and compliance by DNFBPS. Procedia Economics and Finance, 28, pp.14-23. [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. (2022): Financial inclusion and sustainable development: an empirical association: Journal of Money and Business, Vol. 2 No. 2, pp. 186-198. [CrossRef]

- Paramesha, M., Rane, N.L. and Rane, J., (2024): Big data analytics, artificial intelligence, machine learning, internet of things, and blockchain for enhanced business intelligence: Partners Universal Multidisciplinary Research Journal, 1(2), pp.110-133. [CrossRef]

- Passas, I. (2024): Bibliometric Analysis: The Main Steps: Encyclopedia, 4(2), 1014-1025. [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.G. (2000): Institutional theory: Problems and prospects. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/24657 accessed 27 December 2024.

- Prastyanti, R. A., Rezi, R., & Rahayu, I. (2023). Ethical Fintech is a New Way of Banking. Contingency: Scientific Journal of Management 11(1), 255-260. [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, N.D.N.B. (2023), "The Era of the Transition – From Traditional to Digital Banking", Saini, A. and Garg, V. (Ed.) Transformation for Sustainable Business and Management Practices: Exploring the Spectrum of Industry 5.0, Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. 41-55. [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.; Amorim, M.; Melão, N.; Matos, P. (2018): Digital transformation: A literature review and guidelines for future research. In Trends and Advances in Information Systems and Technologies; Rocha, Á., Adeli, H., Reis, L.P., Costanzo, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 411–421. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.S. (2018): What makes users willing or hesitant to use Fintech? the moderating effect of user type. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 118(3), pp.541-569. [CrossRef]

- Sadhya, D. and Sahu, T. (2024): A critical survey of the security and privacy aspects of the Aadhaar framework: Computers & Security, 140, p.103782. [CrossRef]

- Safari, K., Bisimwa, A. and Buzera Armel, M. (2022): Attitudes and intentions toward internet banking in an underdeveloped financial sector. PSU Research Review, 6(1), pp.39-58. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, K. and Kumar, R. (2024): A secure decentralised finance framework. Computer Fraud & Security, Vol (3). [CrossRef]

- Saksonova, S. and Kuzmina-Merlino, I., (2017): Fintech as financial innovation–The possibilities and problems of implementation. [CrossRef]

- Sampat, B., Mogaji, E. and Nguyen, N.P. (2024), “The dark side of FinTech in financial services: a qualitative enquiry into FinTech developers' perspective”, International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 42 No. 1, pp. 38-65. [CrossRef]

- Saxena Ritu (2022): Digital Banking: New Developments in Digital Banking: International Journal of Advanced Research in Commerce, Management & Social Science (IJARCMSS) Volume 05, No. 01(II), January - March, 2022, pp 197-201.

- Schiavo, G.L., (2022): FinTech Regulation and Its Impact on State-Owned Companies in Europe. In Regulation of State-Controlled Enterprises: An Interdisciplinary and Comparative Examination (pp. 621-633). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.A., 2004. Small business and the value of community financial institutions. Journal of Financial Services Research, 25, pp.207-230. [CrossRef]

- Doe, J., Doe, J. and Smith, M. (2023): Publishing an Article with CSTEM press Journals. CSTEM Demo Journal, pp.1-2.

- Smith, J. and Liu, C. (2024): Secure Transactions, Secure Systems: Regulatory Compliance in Internet Banking (No. 12318). Easy Chair.

- Sreekanth, P.V. and Kiran, K.B. (2024): Digital Transformation in Banks: Evidence from Indian Banking Industry. In Interdisciplinary Research in Technology and Management (pp. 262-269). CRC Press.

- Tan, M. and Teo, T.S. (2000): Factors influencing the adoption of Internet banking. Journal of the Association for information Systems, 1(1), p.5. [CrossRef]

- Tanda, A. and Schena, C.M., (2019): FinTech, BigTech and banks: Digitalisation and its impact on banking business models. Springer.

- Tsingou, E. (2022): Effective horizon management in transnational administration: Bespoke and box-ticking consultancies in anti-money laundering. Public Administration, 100(3), pp.522-537. [CrossRef]

- Utami Eka (2021): The Role of Monetary and Macroprudential Policy Instruments on Macroeconomic Stability in Southeast Asian Countries: Proceedings of the International Conference on Management, Business, and Technology (ICOMBEST 2021) Atlantis Press. [CrossRef]

- Velez, S.B., 2024. Regulatory Compliance in Global Banks. In Compliance and Financial Crime Risk in Banks: A Practitioners Guide (pp. 15-25). Emerald Publishing Limited. [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Dong, J.Q.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [CrossRef]

- Windasari, N. A., Kusumawati, N., Larasati, N., et al. (2022): Digital-only banking experience: Insights from gen Y and gen Z: Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(2), 100170. [CrossRef]

- World Bank (2022): New World Bank country classifications by income level: 2022-2023. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 Accessed 27 January 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).