Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- A KPI framework structured across six dimensions

2.1. KPI Definition

2.2. KPI Sub-Criteria

2.2.1. Technical Modelling

2.2.2. Operations and Control

2.2.3. Economic

2.2.4. Environmental

2.2.5. Social

2.2.6. Quality Indicators

2.3. KPI Calculation and Tool Evaluation

2.4. Weight Coefficient Determination

2.4.1. ROC

2.4.2. AHP

2.4.3. EWM

2.4.4. CRITIC

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Selected EMTs

3.2. Results by Methodological Step

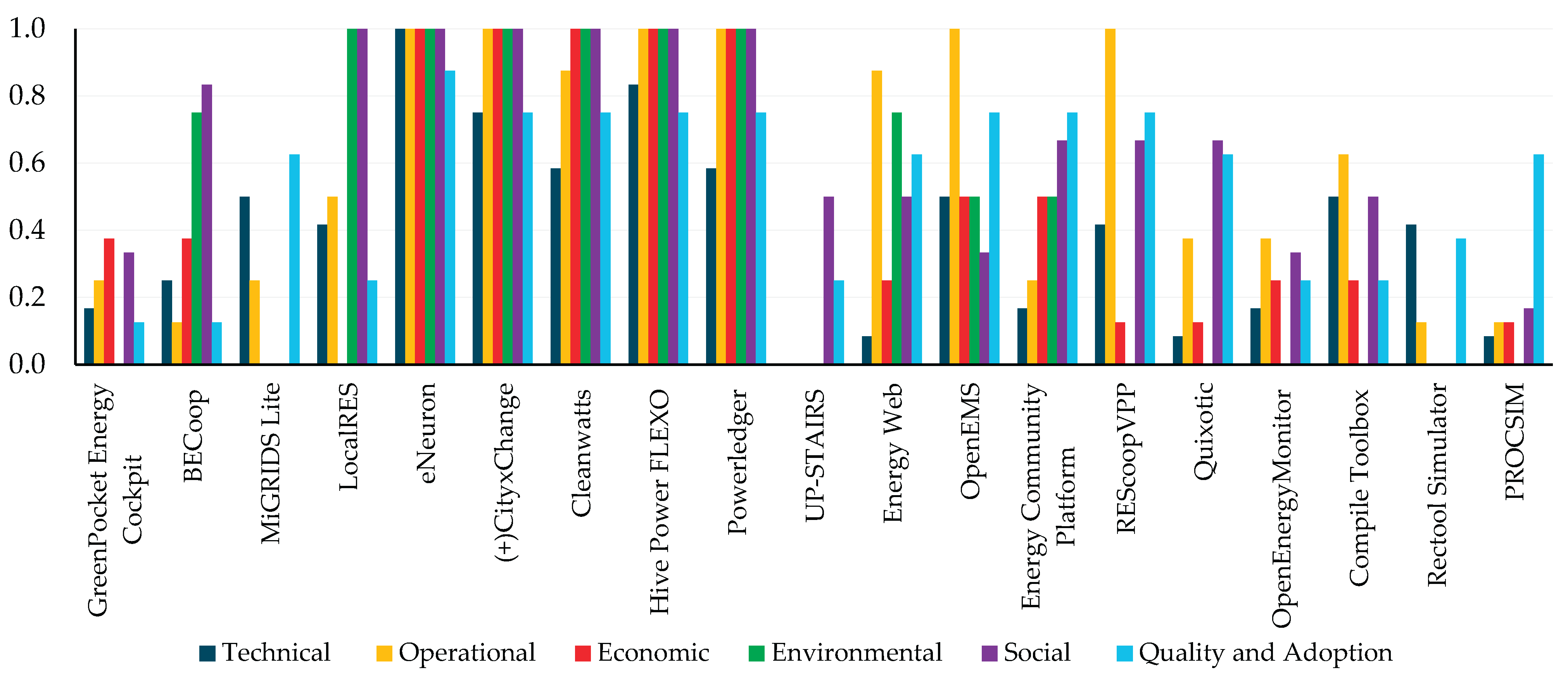

3.3. KPI Results

3.4. Ranking of KPI Dimension

3.5. Results of Weight Coefficients

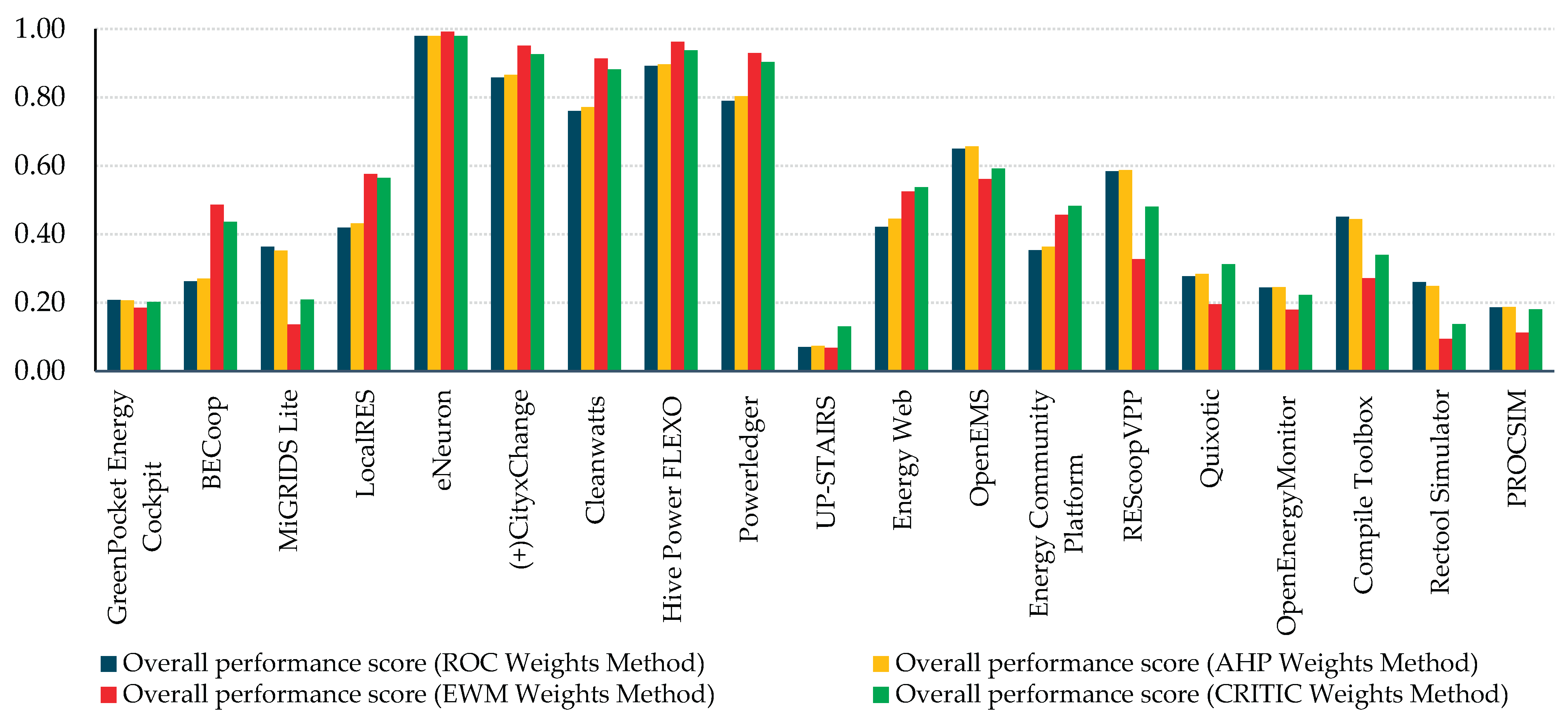

3.6. Results of Final Score

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix 1

| Sub-criteria | Sub-criterion score | ||

| x=0 | x=0.5 | x=1 | |

| TECH_vec | Single vector only | Two vectors | Three or more vectors with explicit couplings |

| TECH_opt | No optimizer (scenario calculation only) |

Single-objective optimization | Multi-objective optimization or equivalent explicit trade-off exploration |

| TECH_Sim | Aggregate/static or seasonal snapshot calculations without continuous time-series | Hourly time-series over representative periods or full year with limited sub-hourly support | Full-year time-series with optional sub-hourly steps, consistent multi-vector balance, and documented numerical/validation details. |

| TECH_forec | No built-in forecasting | Built-in forecasting for at least one stream (e.g., PV or load) or automated import from external services without accuracy reporting | Configurable multi-stream forecasting (load and RES at minimum) with documented methods, horizon/cadence control, and accuracy/confidence reporting. |

| TECH_spat | Non-spatial, aggregate inputs only | Basic GIS support (layer import, georeferencing of assets) | Advanced spatial analytics (3D/shading, geoprocessing queries, perimeter/network checks) |

| TECH_grid | Single-bus balance without grid representation | Simplified treatment (aggregate losses or transformer caps) | Explicit LV/MV network model with power-flow and constraint checking |

| ECON_fin | Costs only | Some KPIs (e.g., LCOE and payback) but not the full set or without transparent assumptions | Full KPI set (NPV, LCOE, IRR, payback) with parameterized assumptions and clear reporting |

| ECON_tar | Single flat tariff only | Multiple static/TOU tariffs or limited dynamic import | Native dynamic pricing support and per-member/asset tariff assignment with scenarioable tariff sets. |

| ECON_sens | No built-in sensitivity | Manual/scenario-by-scenario variation with limited aggregation | Integrated batch sensitivity or stochastic analysis with summarized robustness metrics |

| ECON_shar | No explicit sharing logic (manual spreadsheets required) | Single or hard-coded scheme with limited configurability | Multiple configurable schemes (including dynamic allocation) with transparent statements and exports |

| ENVIR_carb | No emission quantification or only static, generic emission factors without transparency or time resolution | Basic carbon accounting is implemented using national or annual average factors, with limited spatial or temporal granularity. | Comprehensive carbon accounting framework with high-resolution (hourly or regional) emission factors, transparent methodology, and automatic tracking of emissions across scenarios or operational periods. |

| ENVIR_obj | Environmental indicators are reported only as outputs; no influence on design, control, or optimisation decisions. | Environmental parameters (e.g., CO2 intensity, renewable share) can be used qualitatively or as secondary evaluation metrics, but not directly optimised or constrained. | Environmental performance explicitly incorporated as an optimisation objective or constraint (e.g., CO2 minimisation, renewable penetration target, emission caps), with capability for trade-off and scenario analysis. |

| SOC_trans | No member-facing interface or dashboards; information is only accessible to administrators. | Basic dashboards with limited visibility (e.g., simple energy or cost summaries without detailed breakdowns or role differentiation). | Comprehensive, role-based member portal with detailed visualisation of energy, cost, and environmental data; includes data export, report generation, and transparency features that support trust and engagement. |

| SOC_des | No participatory or feedback mechanisms; community members have no structured way to provide input. | Basic feedback options (e.g., static survey or manual preference collection) without integration into platform logic or scenario design | Fully integrated co-design environment with interactive tools (surveys, voting, preference inputs) and feedback loops that directly influence planning, optimisation, or governance decisions. |

| SOC_educ | No built-in help, onboarding, or external documentation; users must rely on ad-hoc support | Basic user manual or FAQ provided; limited contextual help or outdated documentation | Comprehensive learning ecosystem combining interactive onboarding, contextual help, structured documentation (user & developer), and online training resources ensuring accessibility for all user types. |

| OPER_ascl | The platform supports only a single or very limited asset type (e.g., PV monitoring only) with no control or interoperability functions | Multiple asset types are represented but with limited depth (e.g., monitoring without control or lack of standardized integration). | Wide range of controllable and observable assets supported natively, with full data integration, real-time control capability, and interoperability across multiple device classes. |

| OPER_analyt | No analytical or reporting functionality beyond raw data logs. | Basic analytics and standard KPI visualisation (e.g., daily/weekly summaries). | Advanced analytics with predictive/prescriptive functions, automated KPI tracking, and multi-user report generation. |

| OPER_flex | No flexibility or demand response capabilities; assets operate independently. | Basic manual or schedule-based flexibility activation; limited to a single asset class (e.g., batteries or EVs). | Full flexibility aggregation with automated event handling, forecasting, multi-asset coordination (including EVs), and verification of delivery. |

| OPER_EV | Absence of EV-specific functionality beyond manual metering/logging | Support for imported charging schedules or basic rule-based charging, without optimization against price/RES signals and without explicit handling of network constraints | Integrated, policy-based smart charging with optimization against dynamic prices and RES forecasts, explicit enforcement of network/connection constraints, and provision of monitoring and compliance logs |

| QUAL_us | Complex, unintuitive interface requiring expert-level knowledge; no guidance or accessibility support. | Moderately usable interface with partial structure and limited contextual help. | Highly intuitive, user-centred design with clear workflows, multilingual support, and built-in interactive guidance. |

| QUAL_perf | Platform exhibits frequent errors, crashes, or data inconsistencies; performance degrades significantly under normal load. | Platform operates reliably under standard conditions but shows occasional instability or slow performance under heavy computation or large datasets. | Platform demonstrates high reliability and computational performance with stable uptime, efficient resource management, and proven resilience during intensive simulations or multi-user operation. |

| QUAL_scab | Platform cannot scale; performance or stability degrades sharply when data size or number of users increases. | Platform can handle moderate scaling with manual adjustments or partial degradation in responsiveness. | Platform supports seamless scaling in data, users, and functionalities through modular or cloud-based architecture, maintaining stable performance and responsiveness under increased load. |

| QUAL_open | Closed-source platform with proprietary data models and no public documentation or APIs | Partially open system (e.g., documented APIs or selected modules available) with limited transparency | Fully open or transparent ecosystem: open-source code, public API documentation, open data models, and community-driven development. |

Appendix 2

| KPI / Tools/tool | GreenPocket Energy Cockpit | BECoop | MiGRIDS Lite |

LocalRES |

eNeuron |

(+)CityxChange |

|||||

| Tehnical | |||||||||||

| Energy vector | 1 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Simulation capability | 0 | 0,5 | 1 | 0,5 | 1 | 0,5 | |||||

| Forecasting | 0 | 0 | 0,5 | 0 | 1 | 0,5 | |||||

| Optimization | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Spatial / GIS | 0 | 0,5 | 0 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| LV/MV grid constraints & losses | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0,5 | |||||

| Operational | |||||||||||

| Asset classes | 0 | 0 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| EV management | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Analytics and reporting | 1 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Demand response / flexibility aggregation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Economic | |||||||||||

| Financial KPIs | 0,5 | 1 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | 0,5 | |||||

| Tariff / market models | 1 | 0 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Sensitivity | 0 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | 0,5 | |||||

| Benefit-sharing calculators | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0,5 | |||||

| Environmental | |||||||||||

| Carbon accounting | 0 | 0,5 | 0 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Environmental objectives | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Social | |||||||||||

| Member portals & transparency | 1 | 0,5 | 0 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Co-design features | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Education | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Quality and Adoption | |||||||||||

| Usability | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Reliability and performance | 0 | 0 | 0,5 | 0 | 1 | 0,5 | |||||

| Openness | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0,5 | 0,5 | |||||

| Scalability | 0 | 0 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| KPI / Tools/tool | Cleanwatts | Hive Power FLEXO | Powerledger | UP-STAIRS | Energy Web | ||||||

| Tehnical | |||||||||||

| Energy vector | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Simulation capability | 0 | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Forecasting | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Optimization | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Spatial / GIS | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| LV/MV grid constraints & losses | 0 | 1 | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Operational | |||||||||||

| Asset classes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| EV management | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Analytics and reporting | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Demand response / flexibility aggregation | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Economic | |||||||||||

| Financial KPIs | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Tariff / market models | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Benefit-sharing calculators | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Environmental | |||||||||||

| Carbon accounting | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Environmental objectives | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Social | |||||||||||

| Member portals & transparency | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Co-design features | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | ||||||

| Education | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Quality and Adoption | |||||||||||

| Usability | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0,5 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Reliability and performance | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Openness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Scalability | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0,5 | 1 | ||||||

| KPI / Tools/tool | OpenEMS | Energy Community Platform | REScoopVPP | Quixotic | OpenEnergyMonitor | ||||||

| Tehnical | |||||||||||

| Energy vector | 1 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Simulation capability | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Forecasting | 0,5 | 0 | 1 | 0,5 | 0 | ||||||

| Optimization | 0,5 | 0 | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Spatial / GIS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| LV/MV grid constraints & losses | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Operational | |||||||||||

| Asset classes | 1 | 0,5 | 1 | 0,5 | 1 | ||||||

| EV management | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Analytics and reporting | 1 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Demand response / flexibility aggregation | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Economic | |||||||||||

| Financial KPIs | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Tariff / market models | 1 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | ||||||

| Sensitivity | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Benefit-sharing calculators | 0 | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Environmental | |||||||||||

| Carbon accounting | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Environmental objectives | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| Social | |||||||||||

| Member portals & transparency | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Co-design features | 0 | 1 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0 | ||||||

| Education | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Quality and Adoption | |||||||||||

| Usability | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Reliability and performance | 1 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| Openness | 0,5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||

| Scalability | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||

| KPI / Tools/tool | Compile Toolbox / ComPilot & related tools | Rectool Simulator | PROCSIM | ||||||||

| Tehnical | |||||||||||

| Energy vector | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Simulation capability | 0 | 0,5 | 0,5 | ||||||||

| Forecasting | 0,5 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||

| Optimization | 0,5 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Spatial / GIS | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||

| LV/MV grid constraints & losses | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Operational | |||||||||||

| Asset classes | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | ||||||||

| EV management | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Analytics and reporting | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Demand response / flexibility aggregation | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Economic | |||||||||||

| Financial KPIs | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Tariff / market models | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Sensitivity | 0 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||||

| Benefit-sharing calculators | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Environmental | |||||||||||

| Carbon accounting | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Environmental objectives | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Social | |||||||||||

| Member portals & transparency | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Co-design features | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Education | 0,5 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||||

| Quality and Adoption | |||||||||||

| Usability | 0 | 0,5 | 0,5 | ||||||||

| Reliability and performance | 0 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||||

| Openness | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Scalability | 1 | 0 | 0,5 | ||||||||

Appendix 3

| TECH | OPER | QUAL | ECON | SOC | ENVIR | |

| TECH | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| OPER | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| QUAL | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| ECON | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| SOC | 1/5 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1 | 2 |

| ENVIR | 1/6 | 1/5 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1 |

References

- The European Parliament and The Council of The European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources (recast) (Text with EEA relevance.). Official Journal of the European Union. Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- The European Parliament and The Council of The European Union. Directive (EU) 2023/2413 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 October 2023 amending Directive (EU) 2018/2001, Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and Directive 98/70/EC as regards the promotion of energy from renewable sources, and repealing Council Directive (EU) 2015/652. Official Journal of the European Union. Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- The European Parliament and The Council of The European Union. Directive (EU) 2019/944 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on common rules for the internal market for electricity and amending Directive 2012/27/EU (recast) (Text with EEA relevance.) Official Journal of the European Union. Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Caramizaru, E.; Uihlein, A.; Energy communities: An overview of energy and social innovation. JRC Publications Repository 2019, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2020, ISBN 978-92-76-10713-2. [CrossRef]

- Arias, A. Digital Tools and Platforms for Renewable Energy Communities: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2023-2024.

- Yazdanie, M.; Orehounig, K.; Advancing urban energy system planning and modeling approaches: Gaps and solutions in perspective. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 137, 110607, ISSN 1364-0321. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, M.; Causone, F.; Hong, T.; Chen, Y.; Urban building energy modeling (UBEM) tools: A state-of-the-art review of bottom-up physics-based approaches. Sustainable Cities and Society 2020, 62, 102408, ISSN 2210-6707. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Chandel, S. S.; Review of software tools for hybrid renewable energy systems. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2014, 32, 192-205, ISSN 1364-0321. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Giannuzzo, L.; Minuto, F.D.; Schiera, D.S.; Branchetti, S.; Petrovich, C.; Gessa, N.; Frascella, A.; Lanzini, A. Assessment of renewable energy communities: A comprehensive review of key performance indicators. Energy Reports 2025, 13, 6609–6630, ISSN 2352-4847. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Wiese, F., Hilpert, S., Kaldemeyer, C.; A qualitative evaluation approach for energy system modelling frameworks. Energ Sustain Soc 2018 8, 13. [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, F.; Stasi, R.; Berardi, U. Modelling tools for the assessment of renewable energy communities. Energy Reports 2024, 11, 3941–3962. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Velkovski, B.; Gjorgievski, V.Z.; Kothona, D.; Bouhouras, A.S.; Cundeva, S.; Markovska, N.. Impact of tariff structures on energy community and grid operational parameters. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2024, 38, 101382, . Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, K.; Tuomela, S.; Juntunen, J.K.; Emergence and prospects of digital mediation in energy communities: Ecosystem actors’ perspective. Energy, Sustainability and Society 2025, 15, 35. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, H.; Munné-Collado, Í.; Mehmood, F.; Syed, T.A.; Driesen, J.; Towards data-driven energy communities: A review of open-source datasets, models and tools. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 148,111290. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Amin, R. Exploring stakeholder engagement in energy system modelling and planning: A systematic review using SWOT analysis. Energies and Sustainable Planning Journal 2025, 28, 153-178. [CrossRef]

- Johannsen, R.M.; Prina, M.G.; Østergaard, P.A.; Mathiesen, B.V.; Sparber, W.; Municipal energy system modelling—A practical comparison of optimisation and simulation approaches. Energy 2023, 269, 126803, ISSN 0360-5442. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Weighted Sum Method — an overview. ScienceDirect Topics. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/weighted-sum-method (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Macgregor, G. How to do Research: A Practical Guide to Designing and Managing Research Projects, 3rd.; ed. Library Review; London, GB, 2007. 337–339. Available on: . [CrossRef]

- Glenn A. Bowen; Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal 3 August 2009; 9 (2): 27–40.

- Triantaphyllou, Evangelos. (2000). Multi-Criteria Decision Making Methods: A Comparative Study. 10.1007/978-1-4757-3157-6.

- Mardani, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Khalifah, Z.; Zakuan, N.; Jusoh, A.; Md Nor, K.; Khoshnoudi, M.; A review of multi-criteria decision-making applications to solve energy management problems: Two decades from 1995 to 2015. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2017, 216-256, ISSN 1364-0321. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.; Peeling, R. A framework for early-stage sustainability assessment of innovation projects enabled by weighted sum multi-criteria decision analysis in the presence of uncertainty. Open Res Europe 2024, 4:162. Available online:. [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Khalifah, Z.; Zakuan, N.; Jusoh, A.; Nor, K.M.; Khoshnoudi, M. A review of multi-criteria decision-making applications to solve energy management problems: Two decades from 1995 to 2015. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev 2017, 71, 216–256. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.; Peeling, R. A framework for early-stage sustainability assessment of innovation projects enabled by weighted sum multi-criteria decision analysis in the presence of uncertainty. Open Research Europe 2024, 4, 162. [CrossRef]

- Jahangirian, M.; Taylor, S. J. E.; Young, T.; Robinson, S. Key performance indicators for successful simulation projects. Journal of the Operational Research Society 2017 68(7), 747–765. [CrossRef]

- Roubtsova, E. KPI design as a simulation project. Proceedings of the 32nd European Modeling and Simulation Symposium 2020, 120-129. [CrossRef]

- Kifor, C.V.; Olteanu, A.; Zerbes, M. Key Performance Indicators for Smart Energy Systems in Sustainable Universities. Energies 2023, 16, 1246. [CrossRef]

- Lamprousis, G.D.; Golfinopoulos, S.K. The Integrated Energy Community Performance Index (IECPI): A Multidimensional Tool for Evaluating Energy Communities. Urban Sci 2025, 9, 264. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, G.; Bonvini, B.; Bracco, S.; Delfino, F.; Laiolo, P.; Piazza, G. Key Performance Indicators for an Energy Community Based on Sustainable Technologies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8789. [CrossRef]

- Mancò, G.; Tesio, U.; Guelpa, E.; Verda, V. A review on multi energy systems modelling and optimization. Applied Thermal Engineering 2024, 236, 121871, ISSN 1359-4311, Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Yang, Y.; Xu, C. A comprehensive review of planning, modeling, optimization, and control of distributed energy systems. Carb Neutrality 2022 1, 28. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Taxt, H.; Bjarghov, S.; Askeland, M.; Crespo del Granado, P.; Morch, A.; Degefa, M.Z.; Rana, R. Integration of energy communities in distribution grids: Development paths for local energy coordination. Energy Strategy Reviews 2025, 58, 101668, ISSN 2211-467X. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Obi, M.; Slay, T.; Bass, R. Distributed energy resource aggregation using customer-owned equipment: A review of literature and standards. Energy Reports 2020, 6. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Johra, H.; de Andrade Pereira, F.; Hong, T.; Le Dréau, J.; Maturo, A.; Wei, M.; Liu, Y.; Saberi-Derakhtenjani, A.; Nagy, Z.; Marszal-Pomianowska, A.; Finn, D.; Miyata, S.; Kaspar, K.; Nweye, K.; O’Neill, Z.; Pallonetto, F.; Dong, B. Data-driven key performance indicators and datasets for building energy flexibility: A review and perspectives. Applied Energy, 2023, 343, 121217, ISSN 0306-2619. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Ranaboldo, M.; Aragüés-Peñalba, M.; Arica, E.; Bade, A.; Bullich-Massagué, E.; Burgio, A.; Caccamo, C.; Caprara, A.; Cimmino, D.; Domenech, B.; Donoso, I.; Fragapane, G.; González-Font-de-Rubinat, P.; Jahnke, E.; Juanpera, M.; Manafi, E.; Rövekamp, J.; Tani, R. A comprehensive overview of industrial demand response status in Europe. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 203, 114797, ISSN 1364-0321, Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Teng, Q.; Wang, X.; Hussain, N.; Hussain, S. Maximizing economic and sustainable energy transition: An integrated framework for renewable energy communities. Energy 2025, 317, 134544, ISSN 0360-5442. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Delapedra-Silva, V.; Ferreira, P.; Cunha, J.; Kimura, H. Methods for Financial Assessment of Renewable Energy Projects: A Review. Processes 2022, 10(2), 184; [CrossRef]

- Minuto, F.D.; Lanzini, A. Energy-sharing mechanisms for energy community members under different asset ownership schemes and user demand profiles. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 168. [CrossRef]

- Ryszawska, B.; Rozwadowska, M.; Ulatowska, R.; Pierzchała, M.; Szymański, P. The Power of Co-Creation in the Energy Transition—DART Model in Citizen Energy Communities Projects. Energies 2021, 14(17), 5266; [CrossRef]

- Berendes, S.; Hilpert, S.; Günther, S.; Muschner, C.; Candas, S.; Hainsch, K.; van Ouwerkerk, J.; Buchholz, S.; Söthe, M. Evaluating the usability of open source frameworks in energy system modelling. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 159, 112174, ISSN 1364-0321. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Department for Energy Security & Net Zero, Use of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis in options appraisal of economic cases, 2024. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6645e4b2b7249a4c6e9d3631/Use_of_MCDA_in_options_appraisal_of_economic_cases.pdf.

- O’Shea, R.; Deeney, P.; Triantaphyllou, E.; Diaz-Balteiro, L.; Tarim, S.A. Weight Stability Intervals for Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Using the Weighted Sum Model. Expert Systems with Applications 2026, 128460. [CrossRef]

- https://ebrary.net/134839/mathematics/methods_choosing_weights.

- Hatefi, M.A. An Improved Rank Order Centroid Method (IROC) for Criteria Weight Estimation: An Application in the Engine/Vehicle Selection Problem. Informatica 2023 34, 2, 249–270 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Kunsch, P. A critical analysis on Rank-Order-Centroid (ROC) and Rank-Sum (RS) weights in Multicriteria-Decision Analysis. Vrije Universiteit Brussel 2019.

- Diahovchenko, I.M.; Kandaperumal, G.; Srivastava, A.K. Enabling resiliency using microgrids with dynamic boundaries. Electric Power Systems Research 2023, 221, 109460, ISSN 0378-7796. [CrossRef]

- Bozorg-Haddad, O.; Loáiciga, H.; Zolghadr-Asli, B. Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, S. A Simplified Algorithm for Dealing with Inconsistencies Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process. Algorithms 2022, 15(12), 442; [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tian, D.; Yan, F. Effectiveness of Entropy Weight Method in Decision-Making. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2020. 1-5. 10.1155/2020/3564835. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.R.; Kasim, M.M.; Hamid, R.; Ghazali, M.F. A Modified CRITIC Method to Estimate the Objective Weights of Decision Criteria. Symmetry 2021, 13, 973. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Fan, J. & Gao, C. CRITID: Enhancing CRITIC with advanced independence testing for robust multi-criteria decision-making. Sci Rep 2024 14, 25094. [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E. Rank Ordering Criteria Weighting Methods—A Comparative Overview. Optimum Economic Studies 2013. [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L.; Vargas, L.G. Models, Methods, Concepts & Applications of the Analytic Hierarchy Process, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-4614-3596-9.

- Arce, M.E.; Saavedra, Á.; Míguez, J.L.; Granada, E. The use of grey-based methods in multi-criteria decision analysis for the evaluation of sustainable energy systems: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015 47, 924-932, ISSN 1364-0321. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; An, R. Research on the coordinated development capacity of China’s hydrogen energy industry chain. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 377, 134177, ISSN 0959-6526. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.R.; Mat Kasim, M.; Hamid, R.; Ghazali, M.F. A Modified CRITIC Method to Estimate the Objective Weights of Decision Criteria. Symmetry 2021, 13(6), 973; [CrossRef]

- Berman, J.J. Chapter 4—Understanding Your Data, Berman, J.J. Data Simplification, 2016, Pages 135-187, ISBN 9780128037812, Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Bult-Ito, Y. UAF News and Information, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Free tool helps small communities pick renewable energy sources. 7 August 2025. Available online: https://www.uaf.edu/news/free-tool-helps-small-communities-pick-renewable-energy-sources.php (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Gilchrist, P. New tool looks to make grid modeling more accessible to small communities. 24 August 2025. Available online: https://fm.kuac.org/2025-08-24/new-tool-looks-to-make-grid-modeling-more-accessible-to-small-communities (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Localres. Available online: https://www.localres.eu/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- eNeuron. Optimising the design and operation of local energy communities based on multi-carrier energy systems. Available online: https://eneuron.eu/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- +CityxChange. Positive City ExChange—Enabling the co-creation of the future we want to live in. Available online: https://cityxchange.eu/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- +CityxChange. Developing a Lighthouse Project for Positive Energy Districts. +CityxChange Project, Horizon 2020 Grant Agreement No 824260; Sustainable Places 2019: [Limerick, Ireland]. 2021. Available online: https://www.sustainableplaces.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/CityxChange-%E2%80%93-Developing-a-Lighthouse-Project-for-Positive-Energy-Districts.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- +CityxChange. CORDIS—EU Research Results. Positive city exchange. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/824260/results (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- ABB. The climate-positive city. Available online: https://new.abb.com/news/detail/110049/the-climate-positive-city (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Gall, T.; Carbonari, G.; Ahlers, D.; Wyckmans, A. Co-Creating Local Energy Transitions Through Smart Cities: Piloting a Prosumer-Oriented Approach. Vol. 16; 2020; pp. 112–127. Available online: https://www.institute-urbanex.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Co-Creating-Local-Energy-Transitions-Through-Smart-Cities-Piloting-a-Prosumer-Oriented-Approach.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Cleanwatts. Cleanwatts — Shaping the Future of Sustainable Energy. Available online: https://cleanwatts.energy/ (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Cleanwatts. Cleanwatts Official Channel. YouTube channel, available online: https://www.youtube.com/@cleanwatts4048 (accessed on 25 Agust 2025).

- ABB. ABB-Cleanwatts solution—Scaling community energy solutions. Available online: https://new.abb.com/low-voltage/solutions/energy-efficiency/abb-cleanwatts (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Hive Power SA. FLEXO. Available online: https://www.hivepower.tech/flexo (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Powerledger. Powerledger — Software solutions for tracking, tracing and trading renewable energy. Available online: https://powerledger.io (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Messari. Power Ledger (POWR)—Project Profile. Available online: https://messari.io/project/power-ledger/profile (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- CoinMarketCap. Powerledger (POWR)—Cryptocurrency profile. Available online: https://coinmarketcap.com/currencies/power-ledger (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- eCREW. The App. Available online: https://ecrew-project.eu/the-app (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- GreenPocket GmbH. Residential Customers—Energy Cockpit for residential customers. Available online: https://www.greenpocket.com/products/residential-customers (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- BECoop. D2.4 BECoop Toolkit—Final. BECoop Project (Horizon 2020 Grant Agreement No 952930), October 2022. Available online: https://becoop-kep.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/D2.4_BECoop_Toolkit-Final_V1.0_compressed.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- BECoop. Unlocking the Community Bioenergy Potential. Available online: https://www.becoop-project.eu/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- UP-STAIRS. UP-lifting energy communities. Available online: https://www.h2020-upstairs.eu/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- UP-STAIRS. About the UP-STAIRS. Available online: https://www.h2020-upstairs.eu/about (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- COMPILE. Integrating Community Power in Energy Islands. Available online: https://main.compile-project.eu/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- OpenEnergyMonitor. OpenEnergyMonitor—Open Source Energy Monitoring and Analysis Tools. Available online: https://openenergymonitor.org/ (accessed on 26 September 2025).

- OpenEnergyMonitor. Emoncms—User login. Available online: https://emoncms.org/app/view?name=MySolarBattery (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Joint Research Centre, European Commission. REC Tool—Renewable Energy Communities Tool. Available online: https://ses.jrc.ec.europa.eu/rectool (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- De Paola A.; Musiari, E.; Andreadou, N. Fortunati L.; Francesco G.; Anselmi G. P.; An Open-Source IT Tool for Energy Forecast of Renewable Energy Communities. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 69619–69630. [CrossRef]

- Velosa, N.; Gomes, E.; Morais, H.; Pereira, L. PROCSIM: An Open-Source Simulator to Generate Energy Community Power Demand and Generation Scenarios. Energies 2023, 16, 1611. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/16/4/1611 (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Energy Web. Energy Web—Built, connect, transform. Available online: https://www.energyweb.org/ (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Energy Web. Energy Web X Ecosystem. Documentation overwiev. Available online: https://docs-launchpad.energyweb.org (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- OpenEMS Association e.V. OpenEMS—The Open Source Energy Management System. Available online: https://openems.io/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- OpenEMS Association e.V. OpenEMS—Introduction. Available online: https://openems.github.io/openems.io/openems/latest/introduction.html (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- REScoop.eu. Energy Community Platform—One-stop solution for community energy projects. Available online: https://energycommunityplatform.eu/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- REScoopVPP. REScoopVPP—Community-driven Virtual Power Plant and Smart Building Ecosystem. Available online: https://www.rescoopvpp.eu/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency. Horizon Energy: REScoopVPP—Smart Building Ecosystem for Energy Communities. Available online: https://cinea.ec.europa.eu/featured-projects/horizon-energy-rescoopvpp-smart-building-ecosystem-energy-communities_en (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Quixotic. Quixotic—Cloud solution to automate energy billing and invoicing operations for energy communities and utilities. Available online: https://www.quixotic.energy/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

| Tool/Platform | Goal/Description | Scale and Scope | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| MiGRIDS Lite | Open-source tool for microgrid energy modelling, dispatch optimisation, and sizing using real data. | Small-scale or isolated microgrids (village or island level). | [58,59] |

| LocalRES | Supports municipalities and stakeholders in planning, designing, and optimising Renewable Energy Communities (RECs). | Medium-scale local energy communities (municipal or district level). | [60] |

| eNeuron | Multi-energy carrier simulation and optimisation integrating electricity, heat, gas, and mobility. | Medium to large-scale REC or multi-district systems. | [61] |

| (+CityxChange) | Demonstrates positive-energy blocks and local energy trading within smart-city environments. | Medium to large city districts. | [62,63,64,65,66] |

| Cleanwatts (Kiplo) | Commercial digital platform for creation and optimisation of RECs with PV, BESS, and EVs. | Scalable from small residential RECs to multi-community portfolios. | [67,68,69] |

| Hive Power FLEXO | Flexibility and community orchestration platform for DSOs, aggregators, and RECs. | Medium to large communities, scalable to national aggregation. | [70] |

| Powerledger (xGrid / TraceX) | Blockchain-based local energy-trading platform enabling peer-to-peer and prosumer market transactions. | Large-scale implementation—from community pilots to national and international markets. | [71,72,73] |

| GreenPocket Energy Cockpit | A consumer-facing web & mobile app for energy visualization and engagement used in community pilots to give households transparency on consumption, production, peer comparison, and community features. | From small scale communities to medium scale communities | [74,75] |

| BECoop (H2020) | BECoop aims to put communities in charge of their local renewable (bio)energy generation, overcoming barriers such as knowledge and policies to make bioenergy heating communities more appealing. | Mostly aimed for small, local or regional communities | [76,77] |

| UP-STAIRS (H2020) | The project’s goal is to accelerate the creation of energy communities in the EU by deploying One-Stop Shops, facilitating adoption of renewable energy projects, and enabling local actors to navigate complexity. | Scope of the project is to build small or medium and local communities, but with idea to do that in as many regions across EU as possible. | [78,79] |

| COMPILE Toolbox / ComPilot | Project aims to provide the technical stack, community tools, and support to enable community energy to operate reliably while respecting network constraints, especially in weak grid, islanded systems. | Focus on smaller scale, local communities and microgrids. | [80] |

| OpenEnergyMonitor (Emoncms) | Providing an open-source, modular monitoring, logging, visualization, and data analysis platform for energy systems, enabling users to better understand and interact with their energy usage and systems. | For smaller enviroments, more aimed for single household or small community. | [81,82] |

| Rectool Simulator | To provide tool, for predicting energy behaviour of RECs on the basis of their fundamental planning parameters (type/number of members, installed generation, geographical location). | Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) and private customers | [83,84] |

| PROCSIM | Helping to reduce the carbon footprint, by helping to create datasets for generalization, testing and evaluation of renewable energy resource management. | Generalized datasets, for applying the data to medium, larger scale communities. | [85] |

| Energy Web | Acceleration of the global energy transition by providing an open-source, enterprise-grade blockchain | Scales from small communities to global utilities and enterprises. | [86,87] |

| OpenEMS | Open-source modular platform to manage DER, storage, renewables, and flexibility | Scales from small communities to industrial and utility-scale systems | [88,89] |

| REScoop Energy Community Platform | One-stop hub supporting creation and governance of citizen energy communities | Scales from small local groups to national and EU-wide networks | [90] |

| REScoopVPP | Community-driven Virtual Power Plant enabling flexibility, renewables, and smart buildings | Scales from small energy communities to national cooperative networks | [91,92] |

| Quixotic | Cloud-based software as a service platform automating billing, contracting, and energy communities | Scales from small energy communities to utilities and large retailers | [93] |

| Author/KPI criteria | TECH | OPER | ECON | QUAL | ENVIR | SOC |

| Author 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Author 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Author 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| Author 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 5 |

| Author 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Author 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Final ranking | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| KPI criteria/ Method of weight calculation | ROC | AHP | EWM | CRITIC |

| TECH | 0.4083 | 0.3735 | 0.1328 | 0.1373 |

| OPER | 0.2417 | 0.2545 | 0.1262 | 0.1643 |

| ECON | 0.1028 | 0.1021 | 0.2369 | 0.1536 |

| ENVIR | 0.0278 | 0.0430 | 0.3386 | 0.2046 |

| SOC | 0.0611 | 0.0650 | 0.1040 | 0.1811 |

| QUAL | 0.1583 | 0.1620 | 0.0614 | 0.1591 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).