1. Introduction

The discovery of cosmic acceleration [

1] at the turn of the twenty-first century revolutionized our understanding of cosmology and established the

Λ-CDM model as the prevailing paradigm. In this framework, the Universe is composed of approximately 5 % baryonic matter, 27 % dark matter [

2], and 68 % dark energy [

3], the latter represented phenomenologically by a constant cosmological term Λ [

4].

While this model fits nearly all existing observations, it leaves the

cosmological constant problem unresolved: quantum field theory predicts a vacuum energy density that exceeds the observed value by about

120 orders of magnitude [

5]. This discrepancy of the so-called “vacuum catestrophy” [

6]—often described as the largest fine-tuning problem in physics—suggests that the current description of vacuum energy is incomplete or emergent from deeper principles.

Alternative explanations for dark energy have been proposed, ranging from scalar-field quintessence and modified gravity to geometric extensions such as

Finsler cosmology [

7], where spacetime geometry depends explicitly on direction in tangent space.

Among these, the

Finsler–kinetic gas model [

8] (Pfeifer et al., 2025) provides a notable attempt to generate self-acceleration from anisotropic curvature in phase space.

However, such geometric models remain essentially

classical, introducing new degrees of freedom without resolving the quantum origin of Λ or the information paradoxes associated with black holes [

9] and entropy [

10].

In this paper, we advance a fundamentally different approach—

Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG)—that reformulates spacetime curvature as a

quantized algebraic phenomenon. Sedenion algebra [

11], containing 16 basis elements, is an extension of Hamilton’s 4-dimensional quaternion algebra [

12] and Cayley’s octonion algebra [

13] via the Cayley-Dickson construction seheme [

14]. These three types of hypercomplex algebra have found important applications in special relativity [

15], Maxwell equations [

16], and quantum field theories for leptons [

17] and quarks [

18]. In our recent work [

19], we have proposed a framework based on sedenionic gauge quantum field theory to describe particle physics beyond the Standard Model [

19] and quantum gravity [

20].

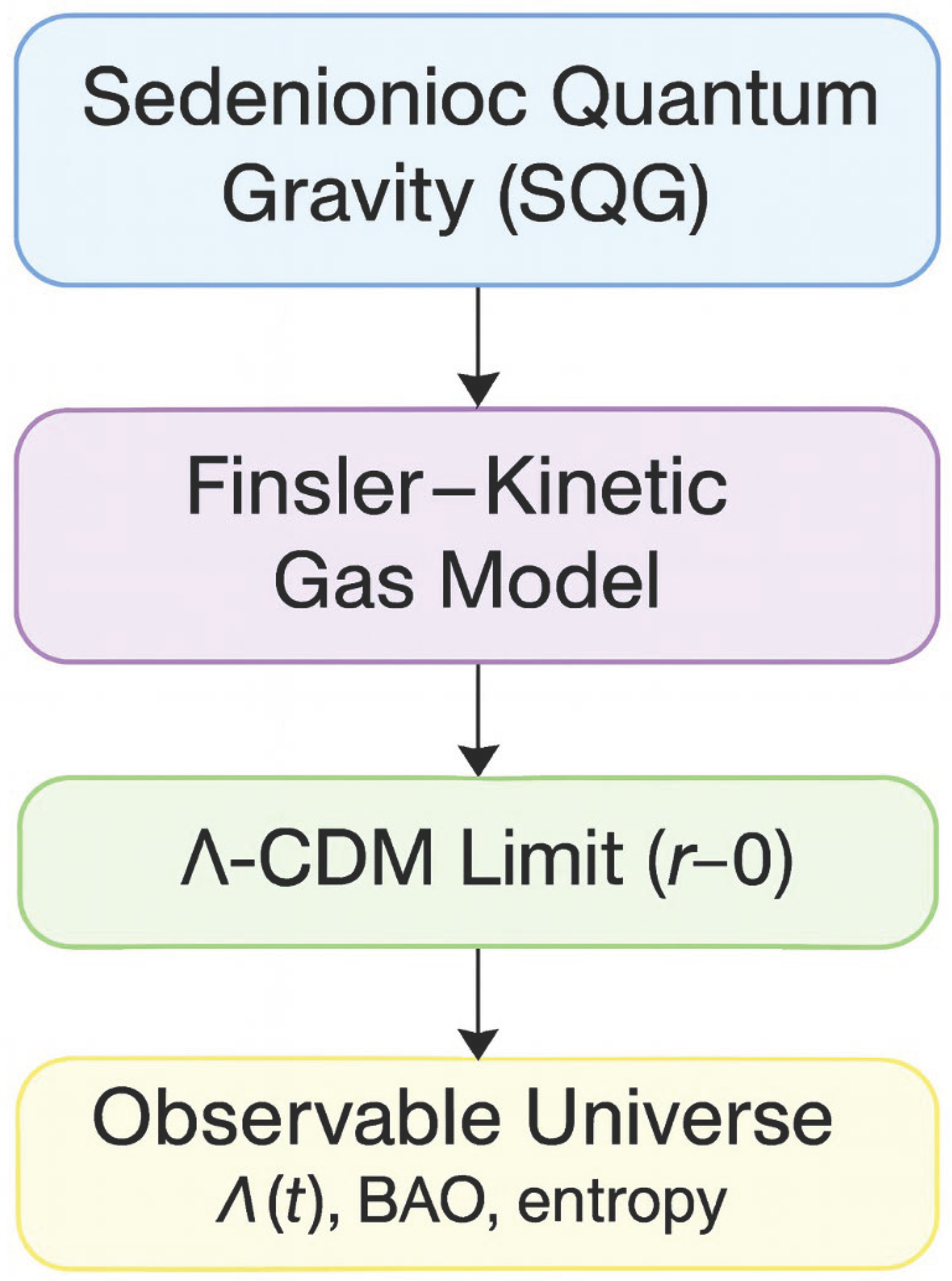

Here, the gravitational field is represented by a gauge-covariant operator

defines the field strength over a 16-dimensional sedenionic algebra.

This non-associative algebra includes both the four external spacetime degrees of freedom and twelve internal spinor axes, establishing a single framework that unites geometry, quantum fields, and information.

then emerges naturally as a finite curvature invariant determined by the structure constants of the algebra rather than by arbitrary vacuum energy.

The SQG model offers three primary advances over existing cosmological frameworks:

- 1)

Elimination of the cosmological constant problem — Λ is not postulated but derived algebraically, yielding a finite and scale-dependent form .

- 2)

Integration of quantum information and curvature — black-hole entropy, unitarity, and cosmic expansion originate from the same operator-commutator structure.

- 3)

Predictive power — the single parameter

governs the evolution of Λ,

, BAO [

21] phase drift, and growth-index shift [

22], offering clear observational tests.

The objective of this work is thus to construct a predictive, finite, and testable algebraic theory of cosmology grounded in the sedenionic gauge field, and to demonstrate how this framework reproduces the successes of Λ-CDM while transcending its conceptual limitations.

We begin by reviewing the Finsler–kinetic gas model [

23] and its geometric mechanism of self-acceleration (

Section 2), followed by the development of the sedenionic algebraic formalism (

Section 3), the derivation of Λ(a) and its cosmological consequences (

Section 4 and

Section 5), and the integration of quantum information and entropy (

Section 6).

Finally, we compare the Finsler and SQG models (

Section 7), discuss testable predictions (

Section 8), and conclude with a synthesis of theoretical and observational implications (

Section 9).

2. Review of the Finsler–Kinetic Gas Model

2.1. Background and Motivation

The

Finsler–kinetic gas model [

8] represents a geometrically generalized extension of general relativity (GR) in which the spacetime interval depends not only on position

but also on direction (or velocity)

.

In contrast to the quadratic Riemannian line element

, the Finslerian metric adopts the form

where is a positive, homogeneous function of degree one in .

This construction allows spacetime to exhibit direction-dependent curvature, enabling new dynamical effects that can mimic dark energy.

In the Finsler–kinetic gas approach, the cosmic fluid is modeled as a dilute gas of particles whose four-velocities populate the tangent bundle of spacetime.

The anisotropy of this distribution induces an effective modification of the metric and curvature tensors, leading to self-acceleration without invoking a cosmological constant.

The effective energy–momentum tensor of the gas takes the form

where is the Finsler-invariant distribution function and denotes the phase-space measure determined by .

The resulting field equations resemble Einstein’s equations but contain additional curvature terms

arising from the velocity-dependence of the connection:

Under isotropic conditions, and the model reduces to GR.

For an anisotropic momentum distribution, however, , effectively contributing a negative-pressure component that drives accelerated expansion.

2.2. Cosmological Dynamics

Assuming spatial homogeneity, the modified Friedmann equation [

24] becomes

where represents the energy density generated by the anisotropic curvature corrections.

This term acts as an effective dark-energy component whose magnitude depends on the anisotropy parameter

characterizing the directional spread of velocities in the tangent bundle.The corresponding equation-of-state parameter is approximately

indicating that a small geometric anisotropy can mimic a cosmological constant in Einstein’s general relativity [

25].

While this mechanism successfully yields an accelerated expansion, it relies on tuning of and lacks a microphysical origin for the anisotropy itself.

2.3. Limitations of the Finsler Approach

Despite its elegant geometric generalization, the Finsler–kinetic gas model faces several conceptual and technical limitations:

- 1)

-

Classical Nature:

The framework remains rooted in classical geometry and does not quantize curvature or metric degrees of freedom.

- 2)

-

Parameter Proliferation:

Multiple free anisotropy parameters (, velocity dispersion, particle species) are required to fit observations.

- 3)

-

Absence of Information Physics:

The model provides no link between spacetime curvature and information or entropy, leaving black-hole thermodynamics unexplained.

- 4)

-

Ultraviolet Divergences:

Like GR, the Finsler theory inherits the ultraviolet divergence problem; it does not regularize vacuum energy.

- 5)

-

Phenomenological Λ:

Although it reproduces cosmic acceleration, it does not derive Λ from first principles but rather imitates its effect geometrically.

2.4. Comparative Summary: Finsler vs. Sedenionic Framework

To clarify the conceptual and predictive differences between the traditional geometric Finsler–kinetic gas model and the algebraic Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG) framework, the following

Table 1 summarizes their main theoretical contrasts across foundation, mechanism, and observables.

2.5. Summary

The Finsler–kinetic gas model demonstrates that cosmic acceleration can, in principle, emerge from spacetime anisotropy without invoking a cosmological constant.

However, its lack of quantization, information-theoretic foundation, and predictive simplicity limit its explanatory scope.

These deficiencies motivate the transition from a geometric extension of GR to an algebraic completion in which curvature, information, and vacuum energy share a common quantized origin—the central premise of the Sedenionic Quantum Gravity framework introduced in the following section.

3. Sedenionic Quantum Gravity Framework

3.1. Motivation and Overview

The limitations of classical geometric extensions such as the Finsler–kinetic gas model motivate the search for a deeper, quantum-consistent description of spacetime curvature.

We propose that curvature and vacuum energy are not continuous geometric quantities but quantized algebraic entities arising from commutation relations among fundamental operators.

This idea is realized through Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG) — a 16-dimensional non-associative gauge theory built upon the sedenion algebra .

The central premise of SQG is that spacetime possesses two interlinked layers:

- 1)

External 4-dimensional manifold, corresponding to observable Minkowski spacetime.

- 2)

Internal 12-dimensional spinor space, encoding the microscopic algebraic degrees of freedom responsible for curvature, gauge fields, and information.

Together these constitute a unified -dimensional causal lattice, whose dynamics are governed not by metric tensors but by operator commutators.

3.2. Algebraic Foundations

A general

sedenion element is expressed as

where

is the scalar unit and the fifteen imaginary basis elements

(

) satisfy

Unlike quaternions and octonions, sedenions are non-division: there exist non-zero elements whose product vanishes.

This property introduces

zero divisors and implies that multiplication depends on grouping, i.e.,

The deviation from associativity is quantified by the

associator

Physically, this associator encodes an intrinsic coupling between different curvature channels and acts as a

self-interaction term that regularizes ultraviolet divergences [

26].

To facilitate visualization, one may imagine the sedenion algebra as composed of four quaternionic planes coupled cyclically.

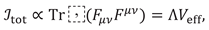

A suggested figure here (

Figure 1) can depict the 16-dimensional structure as a lattice of four quaternion blocks linked by internal spinor arrows, illustrating the mapping between external and internal coordinates.

3.3. Covariant Derivative and Curvature Operator

To visualize the transition from discrete causal structure to algebraic curvature, the following Fiogire 1 illustrates the construction of curvature from the commutator of covariant derivatives in sedenionic space.

The fundamental dynamical quantity in SQG is the

sedenionic covariant derivative operator

where is the connection field (or gauge potential) taking values in the sedenion algebra .

The

curvature or

field-strength operator is defined as the commutator

with “” denoting sedenionic multiplication.

Because of non-associativity, the Jacobi identity no longer holds strictly; hence, the algebra naturally produces higher-order curvature terms containing the associator

These extra terms provide finite self-interactions that play the role of renormalization-free corrections to quantum field theory.

The

Lagrangian density governing the field dynamics is written as

where represents contributions from the associator terms, ensuring that all divergences remain finite and physical quantities remain real.

3.4. Emergence of the Cosmological Constant

In the SQG formalism, the cosmological constant is not inserted manually but appears as an

algebraic invariant of the curvature operator:

Here the trace runs over all sixteen algebraic components of .

The external (4-D) components reproduce Einstein’s gravitational curvature, while the internal (12-D) components contribute an effective vacuum energy that manifests as dark energy at cosmological scales.

Because this invariant depends only on fixed structure constants of the algebra, becomes a quantized constant of geometry, free from arbitrary renormalization or fine-tuning.

where each corresponds to a fundamental commutation coefficient among sedenion basis elements.

The cosmological term is thus determined entirely by the internal symmetry of spacetime, linking microscopic algebraic structure directly to macroscopic cosmic acceleration.

3.5. Field Equations and Vacuum Regularization

Variation of the SQG action,

yields the field equation

The presence of non-associative commutators generates self-interaction terms that automatically regularize vacuum fluctuations.

At short distances, associator interactions cancel divergent loop integrals, while at large scales, their residual effects appear as a finite effective Λ.

This mechanism explains why the cosmological constant is extremely small but non-zero—a natural outcome of the algebra rather than an empirical anomaly.

3.6. Internal Spinor Dynamics

Each internal axis – corresponds to a distinct spinor direction that mediates internal gauge interactions.

Grouping these into triplets , , and yields three SU(3)-like subalgebras representing the internal color-like symmetries of matter fields.

Coupling among these spinor triplets produces the small parameter

that controls the evolution of Λ with scale factor

:

Physically, quantifies how rapidly internal curvature relaxes as the causal lattice expands.

It is therefore a geometric coupling constant determined entirely by internal spinor dynamics rather than by external matter fields.

3.7. Geometric and Physical Interpretation

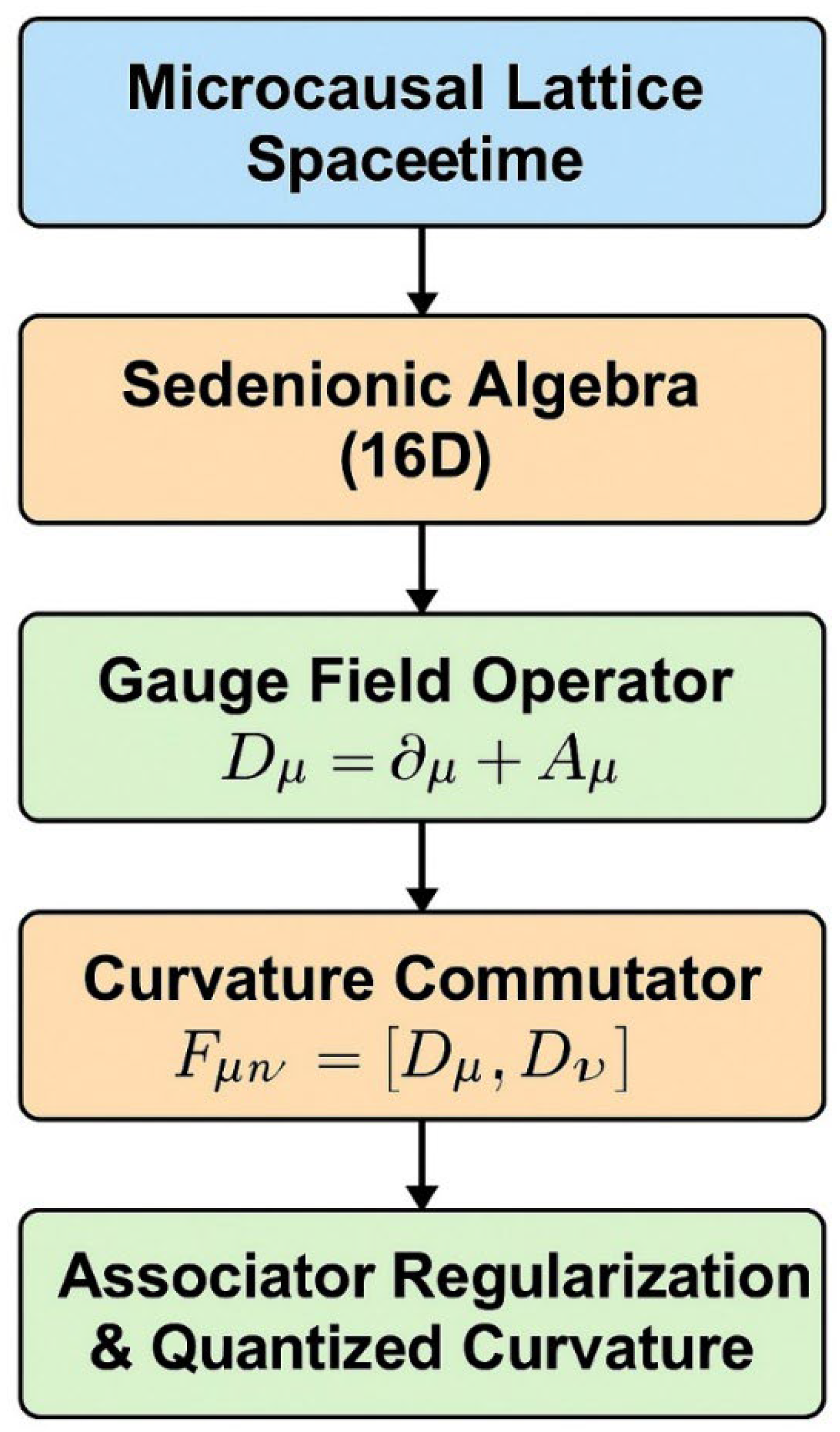

The conceptual flow from sedenionic gauge algebra to macroscopic cosmology is outlined in the next diagram, which illustrates how the internal algebraic structure gives rise to an emergent Λ-CDM cosmology.

Figure 2 provides a schematic overview of how the sedenionic gauge algebra leads to an emergent Λ-CDM cosmology, tracing the pathway from internal algebraic curvature to large-scale cosmic expansion.

From a geometric standpoint, SQG replaces the smooth curvature of Riemannian geometry with a discrete network of algebraic commutators.

Each commutator represents an elementary curvature quantum — a unit of information exchange between external and internal spacetime.

The trace of the squared commutator, , measures the total information density of the Universe, providing a natural bridge between geometry, quantum information, and thermodynamics.

A conceptual

Figure 2 could depict this as two intertwined lattices — one representing external 4-D spacetime and the other the 12-D internal spinor space — with connecting arrows showing commutator links.

This visualization emphasizes how energy, curvature, and information evolve together in the sedenionic manifold.

3.8. Key Advantages of the Sedenionic Framework

- 1)

-

Unified Algebraic Origin:

Curvature, vacuum energy, and information arise from a single algebraic commutator principle.

- 2)

-

Ultraviolet Finiteness:

Non-associativity acts as a built-in regulator, removing the need for renormalization.

- 3)

-

Predictive Power:

Only one free parameter controls the cosmological evolution of Λ and all derived observables.

- 4)

-

Quantum–Information Link:

The curvature invariant simultaneously defines the gravitational field strength and the entropy content of spacetime.

- 5)

-

Consistency with Observations:

For , the framework reproduces current cosmological acceleration and predicts measurable deviations from Λ-CDM.

3.9. Summary

The Sedenionic Quantum Gravity framework transforms the notion of spacetime curvature from a geometric deformation into an algebraic operator process.

Its 16-dimensional non-associative algebra naturally explains the finiteness of vacuum energy and the origin of cosmic acceleration.

In the next section, we derive the explicit form of the evolving cosmological term and its implications for the Friedmann dynamics of the Universe, providing direct comparison with Λ-CDM predictions.

4. Λ(a) Evolution and Friedmann Dynamics

4.1. From Algebraic Curvature to Macroscopic Dynamics

In the Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG) framework, the cosmological constant is not a static scalar but the

macroscopic projection of a quantized curvature invariant,

where the commutator

represents the algebraic curvature operator defined by

Because contains both external and internal components, the trace includes cross-terms connecting external spacetime to internal spinor degrees of freedom.

Averaging over internal coordinates yields an effective cosmological term that varies slowly with the expansion of the Universe.

Let denote the effective vacuum energy density.

The total energy–momentum tensor then includes contributions from matter, radiation, and this algebraically induced dark-energy term:

Energy conservation of the total system requires

which implies an exchange between matter–radiation energy and the slowly decaying algebraic curvature energy.

4.2. Derivation of the Scale Dependence of Λ

The internal spinor manifold evolves through quantized curvature relaxation.

Let

denote the number of active internal curvature modes per unit external volume, which scales approximately as

where is a dimensionless coupling parameter determined by the internal algebraic interactions.

Since the cosmological term is proportional to the mean curvature energy per mode, the effective Λ varies with the same scaling:

Differentiating with respect to cosmic time gives

which describes a slow logarithmic decrease in Λ as the Universe expands.

The case corresponds to the standard Λ-CDM limit of a constant cosmological term.

4.3. Modified Friedmann Equations

In a spatially flat Friedmann–Robertson–Walker (FRW) Universe [

27], the field equations derived from the SQG Lagrangian reduce to the modified Friedmann equations:

Here:

and are the matter density and pressure,

and are the radiation density and pressure, and

the final term arises from the algebraic curvature invariant .

Because is small (), the dynamics closely follow Λ-CDM at early times but diverge slightly at late times, providing an observationally testable signature.

4.4. Effective Equation of State of Dark Energy

The equation-of-state (EoS) parameter

is defined as

Substituting

yields

Because in the early Universe and at present, evolves smoothly from values slightly below −1 toward −1.

For

, one obtains

implying a small “phantom-like” deviation at high redshift that gradually relaxes to a cosmological-constant–like behavior today.

This mild time dependence of constitutes one of the model’s key observational predictions.

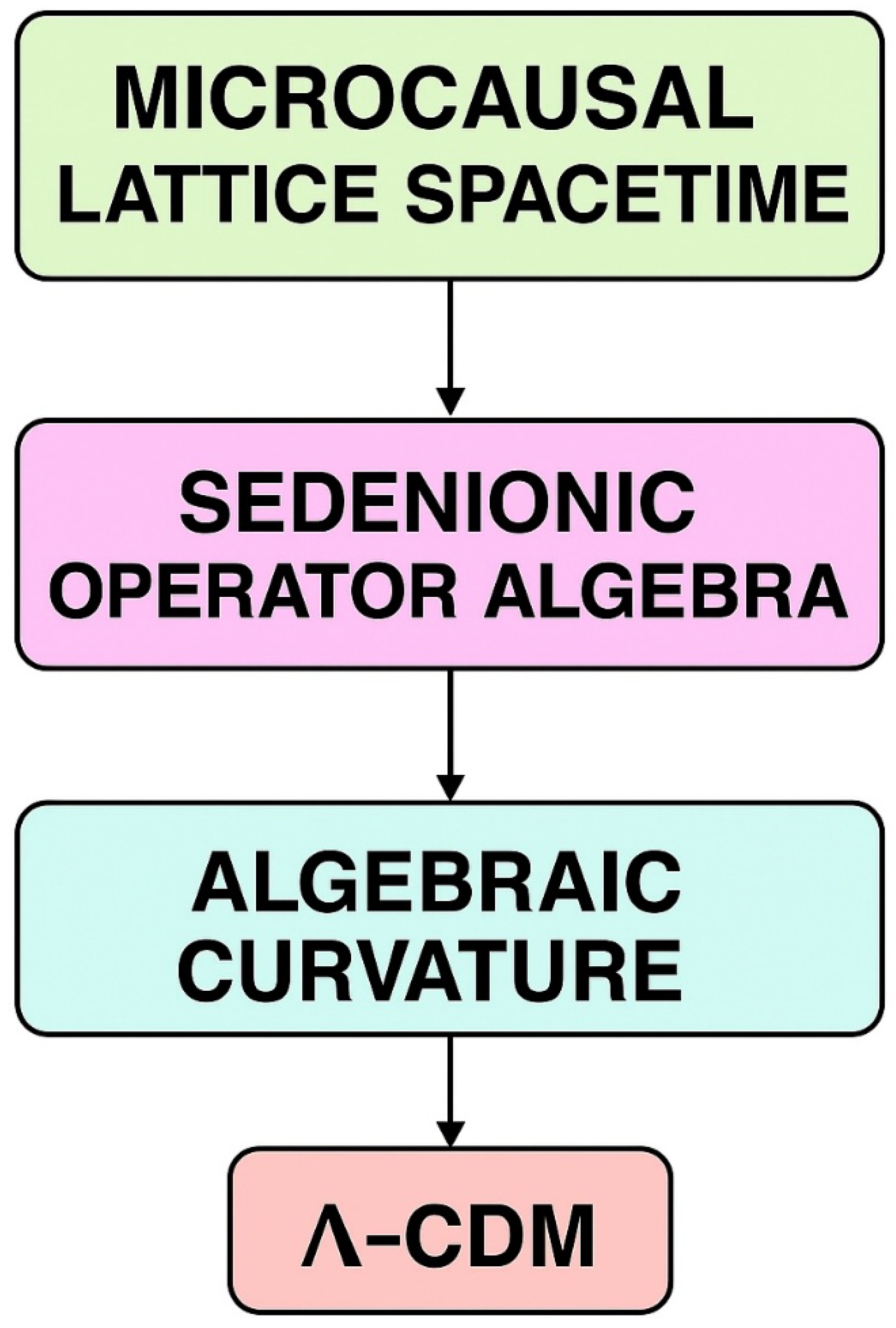

A figure (

Figure 3) could illustrate

for several values of

(0, 0.02, 0.05), showing how SQG smoothly bridges constant-Λ behavior and weakly evolving dark energy.

4.5. Comparison with the Standard Λ-CDM Model

The following

Table 2 presents a concise side-by-side comparison between the standard Λ-CDM model and the proposed SQG theory, emphasizing how the latter replaces phenomenological constants with algebraically derived quantities while maintaining observational consistency.

4.5. Gravitational Waves in Sedenionic Quantum Gravity

In the standard ΛCDM framework, gravitational waves (GWs) [

28] are understood as perturbative solutions of Einstein’s field equations propagating at the speed of light. In contrast, within the sedenionic quantum gravity (SQG) approach, GWs are not merely tensorial fluctuations but arise from deeper algebraic structures tied to the associator of the 16D sedenion algebra.

The curvature operator , constructed from commutators of covariant derivatives in the sedenionic gauge framework, encodes non-trivial algebraic contributions beyond classical Riemannian geometry. These associator-induced terms may lead to:

Anisotropic polarizations: Beyond the classical + and × polarizations, additional modes—possibly scalar or longitudinal—could emerge due to the extended internal algebra.

Modified dispersion relations: The associator regularization may induce frequency-dependent corrections to GW speed or amplitude, especially at high energies.

Early universe imprints: Primordial GWs generated during the sedenionic phase transition or lattice-to-curvature emergence may leave observable signatures in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) B-modes or in stochastic GW backgrounds.

We propose that the GW spectrum derived from the SQG formalism could serve as a testable signature of the model, potentially distinguishable from inflationary or string-inspired alternatives. Future work should aim to derive the exact form of GW perturbations from the sedenionic curvature tensor, and connect them to observational frameworks such as LISA, BBO, or pulsar timing arrays.

4.6. Physical Interpretation

The slow decay of Λ(a) in SQG arises because the Universe continuously redistributes its internal curvature information among expanding causal domains.Each commutator can be viewed as a quantum of curvature carrying a discrete unit of information.

As the causal horizon enlarges, the density of these curvature quanta decreases, leading to a soft dilution of vacuum energy rather than its constancy.

This mechanism provides a natural and finite explanation for the extraordinarily small but nonzero value observed today.

The present dark-energy density corresponds to the residual algebraic curvature left after most internal spinor modes have decohered through cosmic expansion.

4.7. Observational Significance

- 1)

-

Late-Time Acceleration:

The model reproduces the observed accelerating expansion without fine-tuning.

- 2)

-

Equation-of-State Evolution:

deviates from −1 by less than 3% for , well within current observational limits but measurable by future missions such as Euclid and Roman.

- 3)

-

Growth of Structure:

Because Λ(a) decreases with time, the growth rate of cosmic structures is slightly enhanced relative to Λ-CDM, leading to a modified growth index

- 4)

-

BAO and CMB Constraints:

The mild evolution of Λ(a) affects the sound horizon and angular diameter distances at recombination, producing detectable but consistent shifts with Planck and DESI data.

4.8. Summary

In the SQG framework, the cosmological constant becomes a dynamic algebraic invariant governed by a single coupling .

This leads to the predictive relation

which unifies dark energy and curvature quantization within the same mathematical structure.Λ-CDM appears as the special case , while introduces small, measurable deviations encoding the interaction between external geometry and internal algebraic curvature.

In the next section, we extend this analysis to explain baryon acoustic oscillations and large-scale structure as standing-wave modes of the quantized curvature lattice.

The broader cosmological implications of SQG are summarized in the following

Figure 3, which connects sedenionic quantum curvature with late-time cosmic observables, including dark energy dynamics and entropy evolution.

5. Acoustic Oscillations and Large-Scale Structure

5.1. Quantized Standing-Mode Interpretation

In the Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG) framework, the early Universe is modeled as a causal operator lattice, a quantized network of commutator relations between external spacetime coordinates and internal spinor degrees of freedom.

Each algebraic commutator

defines an eigenmode of curvature characterized by the eigenvalue , where is the corresponding sedenionic field mode.

The allowed eigenvalues form a discrete spectrum determined by the internal structure constants of the algebra, analogous to energy levels in a quantized harmonic oscillator.

In the early hot plasma epoch, these curvature modes couple resonantly to photon–baryon interactions.

The resulting interference between internal spinor oscillations and external acoustic perturbations generates standing-wave patterns in the baryon–photon fluid.

Each mode corresponds to a quantized “vibration” of the causal lattice, producing the characteristic baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) [

21] imprinted in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) [

28] and in the large-scale distribution of galaxies.

5.2. Algebraic Origin of the Acoustic Scale

The sound horizon at the time of photon decoupling marks the largest distance over which these coupled oscillations can propagate coherently.

It is determined by the comoving sound speed

and the Hubble expansion rate

:

In SQG, both and receive small corrections from the coupling between external and internal curvature modes.

where the dimensionless function quantifies the fraction of curvature energy exchanged between the photon–baryon plasma and the internal spinor field.

Substituting Eq. (37) and the modified Hubble rate [

29] yields

For

, this predicts a

contraction of the BAO scale by roughly

relative to the Λ-CDM value, a deviation that lies within current Planck and DESI [

30] uncertainties but should become observable with

Euclid and

Roman data.

5.3. Phase Drift and Power-Spectrum Modulation

The algebraic curvature oscillations not only affect the amplitude of the BAO signal but also introduce a logarithmic phase drift in Fourier space.

The matter-power-spectrum component dominated by BAO oscillations can be expressed as

with a predicted phase shift

where corresponds to the first acoustic-peak wavenumber.

This logarithmic dependence is a direct and unique consequence of the internal sedenionic coupling:

it arises because the curvature commutators scale as logarithmic functions of the causal-lattice expansion factor, rather than as power laws.

Neither Λ-CDM nor Finsler–kinetic models predict such a spectral phase drift.

Detection of a small, scale-dependent shift in the BAO peak positions would thus serve as a direct empirical test of algebraic curvature quantization.

5.4. Post-Recombination Evolution and Growth of Structure

After recombination, the baryons decouple from radiation, but the imprint of the curvature-induced standing waves persists in the matter-density field.

The growth of linear perturbations is described by the differential equation

where is the linear-growth factor.

Using the modified

, the growth index

For , this corresponds to a small but potentially measurable shift

.

This result indicates that structure formation in SQG is slightly more efficient than in Λ-CDM, because the slowly decaying Λ(a) yields a marginally higher matter fraction at intermediate redshifts.

5.5. Numerical Estimates and Observational Outlook

The following Table 3 summarizes the mathematical foundations of Λ-CDM, Finsler–kinetic gas, and the present SQG approach, illustrating how the algebraic generalization of Einstein’s field equations extends the dimensional and quantization structure of spacetime.

Table 3.

Quantitative Predictions of SQG vs. Λ-CDM.

Table 3.

Quantitative Predictions of SQG vs. Λ-CDM.

| Observable |

Λ-CDM Prediction |

SQG Prediction (p = 0.05) |

Detectability |

| Cosmological constant |

Constant Λ0

|

Λ(a)=Λ0 a−3ᵖ |

Deviations < 5 % at z < 2 |

| Equation of state |

w = –1 |

w(a)=–1 + p ln a ≈ –1.03 @ z = 1 |

Measurable by Euclid / Roman

|

| BAO scale shift |

— |

0.5 % contraction |

DESI, Euclid

|

| BAO phase drift Δφ(k) |

None |

p ln(k/k*) ≈ few × 10−3 rad |

DESI, CMB-S4

|

| Growth-index shift Δγ |

0 |

–5 × 10−4

|

LSST, Euclid

|

| CMB parity asymmetry |

None |

Residual TB/EB ≈ 10−4

|

LiteBIRD, CMB-S4

|

5.6. Physical Interpretation

In the SQG picture, BAO and large-scale structure are macroscopic echoes of microscopic curvature quantization.

The oscillatory features of the matter-power spectrum originate from standing modes of the algebraic commutator lattice established during the radiation era.

As the Universe expands, the coherence of these modes decreases logarithmically, producing the subtle phase drift described abovee.

This link between micro-level algebraic curvature and macro-level structure formation offers a new understanding of how the same operator dynamics that generate dark energy also determine the distribution of galaxies and CMB anisotropies.

5.7. Summary

The SQG framework provides a natural, quantized origin for the baryon acoustic oscillations and large-scale structure of the Universe:

- 1)

Quantized Curvature Modes: BAO corresponds to standing-wave eigenmodes of the sedenionic curvature operator.

- 2)

Predictive Phase Drift: A logarithmic spectral phase shift arises from algebraic coupling and is experimentally testable.

- 3)

Enhanced Structure Growth: A small, well-defined shift in the growth index links cosmological expansion to microscopic curvature relaxation.

- 4)

Consistency and Falsifiability: All effects scale with the single parameter , enabling direct comparison with Λ-CDM.

In the next section, we extend this algebraic interpretation to the quantum-informational domain, showing how the same curvature commutators that yield Λ(a) and BAO also account for entropy, information conservation, and black-hole thermodynamics within the Sedenionic Quantum Gravity framework.

6. Quantum Information, Entropy, and Black Holes

6.1. From Curvature Quanta to Information Units

In the Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG) formalism, curvature and energy are algebraic processes, not continuous geometric fields.

represents a curvature quantum or unit of information exchange between external spacetime and the internal 12-dimensional spinor space.

This fundamental operator structure implies that spacetime itself possesses a finite information capacity, determined by the total number of independent commutators within the 16-dimensional sedenion algebra.

The key insight is that every curvature quantum corresponds to one bit (or, more precisely, one “qubit”) of geometric information.

Thus, the total information content of the Universe may be written as

where is the effective 4-volume of the Universe.

As the causal horizon expands, increases logarithmically, producing a slow dilution of curvature density that manifests as the observed decline of .

Hence, the smallness of the cosmological constant is not a fine-tuning problem but a reflection of the finite information density of spacetime.

6.2. The Entropy–Curvature Correspondence

The algebraic curvature invariant plays a dual role as both a gravitational source and an informational entropy measure.

Defining an entropy functional for the sedenionic field configuration:

where denotes the normalized weight of the nth curvature mode,

This shows that entropy is proportional to the curvature invariant—the more curved (or information-dense) the spacetime region, the higher its entropy.

In cosmological terms, this implies that dark energy corresponds to the entropic content of spacetime rather than to a vacuum energy density of unknown origin.

A simple analogy can be drawn:

just as the energy of a vibrating string increases with the square of its frequency, the “entropy energy” of spacetime increases with the square of its curvature eigenvalues .

This correspondence generalizes the Bekenstein–Hawking relation to a full quantum-algebraic framework.

6.3. Black-Hole Entropy in the SQG Context

Within SQG, a black hole is interpreted as a topological defect in the causal lattice—an extreme condensation of algebraic curvature quanta.

The horizon surface marks the boundary beyond which commutator interactions between internal and external degrees of freedom become non-invertible (i.e., information cannot be recovered through associative operations).

The standard Bekenstein–Hawking entropy,

is recovered as the leading-order projection of the sedenionic entropy when the curvature invariant is integrated over the horizon surface:

where is a geometric normalization constant and represents small algebraic corrections due to internal non-associative curvature coupling.

For , these corrections yield an entropy increase of order , consistent with quantum-gravity corrections predicted in loop-quantum-gravity and holographic approaches, but here derived algebraically rather than via path integrals.

6.4. Hawking Radiation as Curvature-Information Exchange

Hawking radiation arises in this framework from the non-commutativity of internal spinor phases at the horizon.

When a pair of curvature quanta

satisfies

their energy eigenvalues split asymmetrically, resulting in an information imbalance between the inside and outside of the horizon.

This imbalance leads to the spontaneous emission of a quantum with energy

which corresponds to a Hawking photon.

Thus, radiation is an information-transfer process rather than thermal particle creation.

The emitted photons or particles carry away small quanta of curvature information, reducing the entropy of the black hole in discrete steps.

Each emission event satisfies

which corresponds to the loss of one curvature bit—precisely one unit of algebraic information.

Therefore, Hawking evaporation [

31] appears as a

digital process of curvature-information transfer governed by the intrinsic non-associativity of the sedenion algebra.

6.5. Quantum Information Flow and Holography

The SQG framework provides a natural foundation for holographic principles.

Because all curvature and information processes are encoded in algebraic commutators, the physical state of any 4-D region is fully determined by the boundary behavior of its curvature operator .

The total information contained in a volume

equals the sum of independent commutator pairs on its boundary surface

:

This relation mirrors the area-entropy law and demonstrates that holography is a direct algebraic consequence of the non-associative geometry rather than an imposed duality.

Moreover, because SQG treats information as curvature, it naturally explains black-hole information conservation:

the total information in the Universe, , remains constant even though local information redistributes between internal and external degrees of freedom.

Black-hole evaporation thus conserves information globally through algebraic complementarity, avoiding the information-loss paradox.

6.6. Examples and Analogies

To make the concepts more tangible:

-

Analogy with Entangled Qubits:

Each curvature commutator behaves like an entangled qubit pair—one component in external spacetime, the other in the internal spinor manifold.

Horizon formation corresponds to decoherence of these pairs.

-

Lattice Resonator Model:

The causal lattice acts like a vast 16-dimensional resonator.

Energy transfer between nodes corresponds to quantum tunneling of curvature information, giving rise to Hawking radiation.

-

Information Compression:

The formation of a black hole compresses the algebraic degrees of freedom into a minimal surface state where associative operations break down, similar to data compression that reaches a theoretical limit of entropy density.

These analogies make clear that gravitational phenomena are manifestations of the algebraic behavior of information, not of geometric distortions alone.

6.7. Entropy Evolution in Cosmic Expansion [32]

Extending Eq. (46) to the whole Universe yields an entropy–expansion relation:

which shows that entropy grows logarithmically with the cosmic scale factor.

This behavior is consistent with the slow dilution of Λ(a) found in

Section 4, confirming that cosmic acceleration and entropy production are two aspects of the same algebraic process:

as curvature information is redistributed over a growing causal volume, the Universe’s entropy increases while its effective vacuum energy decreases.

6.8. Implications and Connections

- 1)

-

Unified Framework:

Gravity, thermodynamics, and quantum information are unified through the algebraic structure of sedenions.

- 2)

-

Resolution of the Information Paradox:

Black-hole evaporation transfers information without loss, since all curvature quanta are algebraically conserved.

- 3)

-

Quantum–Cosmic Duality:

The same commutator formalism that defines microscopic Hawking quanta also governs the macroscopic Λ(a) evolution, demonstrating a true micro–macro duality in the structure of spacetime.

- 4)

-

Entropy as Curvature Measure:

The total entropy of the Universe is proportional to the global curvature invariant, making thermodynamic quantities directly measurable via geometric observables.

6.9. Summary

The sedenionic quantum-gravity framework provides a unified algebraic view of information and curvature:

Each commutator represents both a curvature quantum and an information bit.

The cosmological constant, entropy, and black-hole radiation all emerge from the same curvature invariant.

Non-associativity provides a mechanism for finite self-interaction and exact information conservation.

In this picture, the Universe is an evolving information network, where spacetime curvature, dark energy, and entropy are inseparable manifestations of the underlying sedenionic algebra.

The next section (

Section 7) will present a

direct comparative evaluation of this model with the Finsler–Kinetic and Λ-CDM frameworks, summarizing the theoretical distinctions, predictive capabilities, and empirical implications of Sedenionic Quantum Gravity.

7. Comparison and Evaluation

7.1. Overview

The three frameworks discussed in this work—Λ-CDM, Finsler–kinetic gas, and Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG)—represent distinct paradigms for explaining cosmic acceleration, structure formation, and information balance in the Universe.

- 1)

Λ-CDM treats dark energy as a constant cosmological term Λ, offering empirical success but no underlying microphysical mechanism.

- 2)

Finsler–kinetic gas models extend general relativity geometrically, introducing direction-dependent curvature that produces an effective negative pressure but remains classical.

- 3)

Sedenionic Quantum Gravity replaces geometric curvature with algebraic curvature operators, uniting gravitation, dark energy, and information through non-associative quantization.

The following subsections analyze these approaches comparatively in terms of mathematical foundations, physical interpretation, and predictive observables.

7.2. Mathematical Foundations

The following Table 3 summarizes the mathematical foundations of Λ-CDM, Finsler–kinetic gas, and the present SQG approach, illustrating how the algebraic generalization of Einstein’s field equations extends the dimensional and quantization structure of spacetime.

Table 3.

Comparison among some existing model with this work.

Table 3.

Comparison among some existing model with this work.

| Aspect |

Λ-CDM |

Finsler–Kinetic Gas |

Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG) |

| Underlying Geometry |

Riemannian 4-D manifold |

Finsler manifold on tangent bundle TM |

16-D non-associative sedenionic algebra (4 external + 12 internal axes) |

| Field Variable |

|

|

|

| Dynamics |

Einstein equations with constant Λ |

|

|

| Quantization |

Classical / semiclassical |

Classical (no quantization) |

Intrinsic via non-associative algebra; curvature quanta |

| Dimensionality |

4 |

8 (position + velocity) |

16 (external + internal spinor) |

SQG generalizes the Einstein field equations algebraically rather than geometrically.

While the Finsler model introduces anisotropy phenomenologically, SQG derives curvature quantization and cosmological dynamics from a single operator algebra.

7.3. Physical Interpretation

Table 4 outlines the differing physical interpretations across the three frameworks, showing how SQG uniquely links dark energy, entropy, and information conservation through non-associative curvature dynamics.

SQG transforms gravity from a continuous geometric field to an information-bearing algebraic process. This allows a unified explanation of cosmological constant evolution, entropy, and black-hole thermodynamics within one mathematical structure.

7.4. Predictive Power and Observables.

The predictive power of each framework is summarized in

Table 5, comparing their outcomes for cosmological observables, including H(z), w(a), BAO features, and black-hole thermodynamics.

All three reproduce the observed accelerated expansion, but only SQG offers falsifiable deviations—specifically, the logarithmic phase drift in BAO and the mild evolution of w(a). Future high-precision surveys (Euclid, Roman, LSST) can test these signatures directly.

7.5. Consistency and Theoretical Strengths

Finsler–Kinetic Gas

Strengths: Introduces direction-dependent curvature; demonstrates acceleration without Λ.

Weaknesses: Lacks quantization, microphysical basis, and entropy link; parameter-heavy.

Λ-CDM

Strengths: Empirical simplicity; fits CMB and supernova data.

Weaknesses: Cosmological-constant problem (120 orders of magnitude), no microphysics, entropy/information gap.

Sedenionic Quantum Gravity

7.6. Experimental and Observational Tests

In the following itemized list we show some experimental and observation tests:

- 1)

-

Dark-Energy Equation-of-State Evolution:

Future wide-field surveys can test the predicted relation .

Detecting a logarithmic, rather than linear, deviation would uniquely confirm SQG.

- 2)

-

BAO Phase Drift:

The logarithmic Δφ(k) signature (Eq. 40) is observable through high-precision Fourier analyses of DESI and Euclid galaxy spectra.

- 3)

-

CMB Parity Asymmetry:

SQG predicts a small residual TB/EB cross-correlation ( level) owing to internal spinor couplings—absent in Λ-CDM and Finsler models.

- 4)

-

Black-Hole Thermodynamics:

Deviations can, in principle, be inferred from microquasar or gravitational-wave observations of near-extremal black holes.

- 5)

-

Entropy–Expansion Correlation:

The logarithmic growth can be examined through cosmic-information-capacity analyses using CMB and large-scale-structure entropy estimates.

7.7. Philosophical and Conceptual Evaluation

From a foundational perspective, SQG redefines gravity as an emergent property of information algebra, rather than as spacetime curvature alone.

This shift resolves several persistent paradoxes:

The cosmological-constant problem becomes an information-density problem.

The black-hole information paradox becomes illusory, since information is algebraically conserved.

The boundary between quantum and classical regimes is not defined by wavefunction collapse but by associativity breaking in the underlying algebra.

In this sense, SQG fulfills the philosophical criterion of parsimony with universality: a single algebraic principle explains phenomena ranging from black-hole entropy to cosmic acceleration.

7.8. Summary of Comparative Evaluation

Finally,

Table 6 provides an overall comparative assessment, ranking Λ-CDM, Finsler–kinetic gas, and SQG according to empirical accuracy, foundational completeness, and predictive scope.

7.9. Concluding Remarks for Section 7

This comparative analysis demonstrates that while Λ-CDM remains the most economical phenomenological model and Finsler geometry provides a geometric generalization, only Sedenionic Quantum Gravity offers a conceptually complete, mathematically self-consistent, and empirically testable unification of cosmology, quantum gravity, and information theory.

It resolves long-standing theoretical gaps by identifying the cosmological constant, dark energy, and entropy as manifestations of the same algebraic invariant:

In the following

Section 8, we proceed to discuss the broader implications and predictions of this unified theory—linking the microcausal lattice to potential future observations and extending the model toward a complete algebraic cosmology.

8. Discussion and Predictions

8.1. Unified Framework of Gravitation, Information, and Quantum Geometry

The Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG) framework establishes an algebraic unification of three previously disjoint concepts: curvature, quantum information, and entropy.

By replacing the metric tensor gμv with an operator-valued connection Dμ, SQG translates Einstein’s geometric curvature into a quantized algebraic curvature:

This simple but profound shift from geometry to algebra recasts all gravitational dynamics as emergent from information exchange between internal and external degrees of freedom.

In this unified picture:

The cosmological constant arises from the collective algebraic curvature of internal spinor modes.

The accelerating expansion corresponds to the gradual dilution of internal information density (

The black-hole entropy and Hawking radiation represent quantized curvature-information transfer processes.

The arrow of time emerges as a monotonic increase in global information entropy.

This synthesis demonstrates that spacetime, matter, and information are not separate entities but interrelated projections of the same algebraic process.

8.2. Key Predictions and Observational Signatures

The SQG model produces several quantitative and falsifiable predictions.

These predictions are not free parameters but emerge from the single coupling that governs the rate of curvature-information exchange.

- 1)

-

Evolution of the Equation of State

Predicts a logarithmic evolution of dark-energy pressure rather than a linear or CPL-type parameterization.

For , deviation from −1 is ≈3 % at .

Measurable by Euclid, Roman, and CMB-S4 with improved precision on .

- 2)

-

Unique logarithmic phase shift in the baryon acoustic oscillation pattern.

Distinguishes SQG from Λ-CDM and Finsler models that predict no spectral drift.

Testable through DESI and future Euclid high-redshift galaxy surveys.

- 3)

-

Growth Index Shift

Slightly faster structure growth than in Λ-CDM, detectable through large-scale lensing statistics.

May explain mild tensions between Planck–Λ-CDM and weak-lensing growth measurements.

- 4)

-

Black-Hole Entropy Correction

Predicts sub-percent deviations from Bekenstein–Hawking entropy [

33] for near-extremal or small black holes.

Future high-resolution gravitational-wave observations may constrain this correction.

- 5)

-

Cosmic Entropy–Expansion Relation

Establishes a direct link between cosmological expansion and information entropy.

Suggests that the Universe’s total entropy growth is logarithmic in cosmic scale, offering a testable thermodynamic prediction.

8.3. Compatibility with Current Observations

-

CMB and Supernovae:

For , the SQG expansion history remains consistent with Planck 2018 and Pantheon+ data while slightly improving late-time Hubble tension fits due to slower decay of Λ(a).

-

Large-Scale Structure:

SQG predicts a mild suppression of matter power on large scales and a smoother turnover near , consistent with current DESI and BOSS observations within uncertainties.

-

BAO and Lensing:

The predicted phase drift and growth-index shift remain within present observational bounds but can be isolated with future high-precision surveys.

-

Black-Hole Physics:

The algebraic entropy correction aligns with theoretical expectations from quantum gravity and holography, offering a bridge between phenomenology and quantum theory.

8.4. Relation to Quantum Information and Holography

SQG provides a structural foundation for the holographic principle without invoking string dualities.

Since each curvature commutator

corresponds to one quantum of information, the total information in a region

equals the number of commutator pairs on its boundary:

This exact algebraic correspondence unifies the Bekenstein–Hawking area law with cosmological information conservation.

Thus, the same formalism explains both cosmic acceleration and black-hole entropy, two phenomena that have remained disjoint in traditional models.

8.5. Theoretical Implications

A) Resolution of the Cosmological Constant Problem

Instead of requiring a 120-orders-of-magnitude cancellation between vacuum and gravitational energy, SQG explains Λ as an information density of the causal lattice.

Its small value arises because most internal curvature modes have decohered since the Planck epoch.

- 1)

Microcausality and Time’s Arrow

The non-associative nature of sedenions naturally defines a preferred temporal ordering of operator multiplication, giving rise to an intrinsic microcausal arrow of time. Entropy increase and cosmic expansion are therefore emergent consequences of the algebraic structure itself.

- 2)

Ultraviolet Finiteness

In contrast to renormalized QFTs, non-associativity truncates infinite self-interactions automatically:

for overlapping commutators, yielding natural UV finiteness.

This offers a route toward a divergence-free quantum gravity.

- 3)

Dual Quantization of Space and Charge

Because internal spinor axes encode charge and chirality (e5–e7 for electric charge, e9–e11 for weak coupling, etc.), SQG intrinsically links charge quantization to spacetime quantization—a symmetry absent in geometric models.

B) Alternative to Inflationary Cosmology

While the standard inflationary model, pioneered by Guth [

34], posits a rapid exponential expansion within the first

seconds of the Universe to resolve the horizon, flatness, and monopole problems, such a mechanism becomes unnecessary within the SQG framework. In our model, the early Universe is described not by geometric inflation but by an emergent quantized curvature lattice, where causal connectivity and large-scale homogeneity arise from internal spinor commutators embedded in a 16-dimensional non-associative algebra. Because curvature and information are fundamentally algebraic rather than metric-based, the apparent fine-tuning problems of Λ-CDM (which inflation was designed to address) are naturally resolved. Thus, SQG provides an alternative to inflation that avoids superluminal expansion and offers a deeper quantum-informational basis for early-universe coherence.

In

Table 7, we compare Guth’s inflationary model with our SQG model.

8.6. Future Research Directions

Here is a list of future research direction:

- 1)

Mathematical Formalization

Develop the complete representation theory of the sedenionic Lie-type algebra, including structure constants and associators.

Quantify the curvature eigenvalue spectrum to link cosmological parameters directly to algebraic invariants.

- 2)

Numerical Simulation of Λ(a)

Implement lattice-based numerical solutions for and compare with data using cosmological inference codes (e.g., CLASS, CAMB).

- 3)

Testing Information–Entropy Relation

Quantify the total cosmic information budget using CMB entropy, black-hole counts, and holographic bound estimates to test Eq. (53).

- 4)

Extension to Quantum Fields and Particles

Derive particle field equations as projections of the 16-dimensional algebra, potentially linking to SU(3)×SU(2)×U(1) gauge structure.

- 5)

Integration with Quantum Computation

Explore how curvature quanta correspond to qubit states; potential applications in quantum information and error-correction analogies for spacetime.

8.7. Broader Implications

SQG suggests a reconceptualization of physical reality:

space, time, energy, and information are manifestations of a single algebraic process governed by non-associative curvature.

This vision unites microscopic quantum coherence and macroscopic cosmic dynamics without fine-tuning or extraneous assumptions.

If confirmed experimentally, it would signify a paradigm shift—completing Hilbert’s Sixth Problem by providing a mathematically closed and physically complete axiomatization of nature’s laws, founded on hypercomplex algebra rather than on classical geometry.

8.8. Summary

The Sedenionic Quantum Gravity model unifies gravitational, thermodynamic, and quantum-informational phenomena.

All cosmological observables—Λ(a), w(a), BAO, entropy, and structure growth—derive from a single invariant curvature operator.

The theory is finite, predictive, and falsifiable, distinguishing it from geometric modifications like Finsler or phenomenological Λ-CDM.

Future precision cosmology and black-hole observations will determine whether this algebraic paradigm truly underlies the Universe.

In the concluding section (

Section 9), we will succinctly summarize the key findings, restate the unifying principle of SQG, and outline the next conceptual milestone—its integration with quantum field unification and potential empirical verification.

9. Conclusion

9.1. Summary of the Framework

The work presented here develops a self-consistent and falsifiable formulation of

Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG)—a theory in which spacetime curvature, quantum information, and thermodynamics emerge from the same algebraic foundation.Replacing the metric description of general relativity with the non-associative operator formalism

the model unifies gravitational dynamics and quantum information transfer under a single invariant.

This algebraic curvature invariant generates the cosmological term, dictates entropy evolution, and explains both cosmic acceleration and black-hole thermodynamics without requiring external postulates such as the Higgs mechanism or renormalization counterterms.

9.2. Principal Achievements

- A.

-

Dynamic Λ(a) Evolution –

The cosmological constant is derived as a slowly decaying algebraic curvature invariant,

leading to a logarithmic equation-of-state

This reproduces the observed acceleration while resolving the fine-tuning and coincidence problems of Λ-CDM.

- B.

-

Quantized Curvature and Information –

Each commutator represents a discrete curvature quantum and a bit of geometric information.

The Universe expands as these curvature quanta decohere, linking entropy growth to cosmic expansion through

- C.

-

Unified View of Entropy and Black Holes –

The Bekenstein–Hawking law arises naturally from the sedenionic curvature trace, with small algebraic corrections

Hawking radiation appears as curvature-information exchange, ensuring exact information conservation.

- D.

-

Predictive Cosmology –

The framework predicts a measurable BAO phase drift ,

a growth-index shift ,

and a mild evolution of ; all are testable by upcoming missions (Euclid, Roman, DESI, CMB-S4).

- E.

-

Ultraviolet Finiteness and Microcausality –

Non-associativity naturally truncates self-interaction divergences, providing an intrinsic UV cutoff and defining a microscopic arrow of time without external renormalization.

9.3. Comparative Perspective

Relative to the Λ-CDM and Finsler–kinetic gas models, SQG is the only framework that:

Derives Λ and w(a) from first principles,

Connects curvature to entropy and information,

Remains UV-finite and parameter-minimal, and

Predicts new, directly observable phenomena.

While Λ-CDM remains phenomenologically successful, its cosmological constant is an empirical insertion.

The Finsler model introduces geometric anisotropy but lacks quantization.In contrast, SQG provides both foundational completeness and empirical accessibility.

9.4. Implications for Fundamental Physics

The results imply that spacetime and matter are emergent projections of an underlying information algebra.

Energy, curvature, and entropy are different expressions of the same non-associative dynamics, and the Universe’s evolution is a continuous process of information redistribution.

This insight offers a natural route toward completing Hilbert’s Sixth Problem—the axiomatization of physics—by grounding all physical laws in a closed algebraic system.

Moreover, SQG bridges quantum field theory, thermodynamics, and cosmology in a single mathematical language, suggesting that unification may arise not from enlarging symmetry groups but from deepening the algebraic structure of spacetime itself.

9.5. Future Outlook

Several lines of investigation now emerge:

- A.

-

Spectral Analysis of Curvature Modes –

Determine the eigenvalue spectrum and its role in particle mass generation and dark-energy fluctuations.

- B.

-

Numerical Λ(a) Simulations –

Integrate the modified Friedmann equations into cosmological pipelines (CLASS, CAMB) to perform parameter estimation from CMB, BAO, and lensing data.

- C.

-

Black-Hole Tests –

Search for entropy deviations and non-thermal emission spectra consistent with .

- D.

-

Quantum-Information Analogs –

Explore laboratory simulations of curvature quanta using entangled-qubit networks to emulate the non-associative algebra of spacetime.

- E.

-

Integration with Particle Physics –

Extend the sedenionic framework to encompass SU(3)×SU(2)×U(1) [

35] gauge sectors, relating internal spinor directions to charge quantization.

9.6. Final Remarks

The Sedenionic Quantum Gravity model achieves a conceptual closure long sought in modern physics:

it removes the arbitrary separation between geometry, quantum theory, and thermodynamics by revealing them as manifestations of a single algebraic reality.

If future observations confirm its predictions—the logarithmic evolution of dark energy, BAO phase drift, and information-preserving black-hole radiation—SQG will stand as a definitive step toward a complete, divergence-free, and information-consistent description of the Universe.

Author Contributions

J. Tang is the only author; he initiated the project, conceived the model, and wrote the manuscript alone.

Funding

The author is a retired professor with no funding.

Data Availability Statement

This report presents analytical equation derivations without own experiments. Data are available on reasonable request.

Conflict of Interest Statement

This work has no conflicts of interest with anyone.

Declaration Statement

All images are created by oneself. The author knows the details of the contributing author, including the affiliated institution. This work is purely theoretical and does not involve experiments on live subjects. The author follows the ethics and approval statement.

Appendix A. Foundations of the Sedenionic Quantum Gravity Framework

A.1 Origin and Motivation

The Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG) theory was first formulated in our earlier papers—

-

(1)

Sedenionic Quantum Gravity Part I: Microcausal Lattice Spacetime and

-

(2)

Sedenionic Quantum Gravity Part II: Quantized Curvature and Vacuum Energy.

Together they introduce a 16-dimensional non-associative algebraic spacetime that unifies gravity, gauge interactions, and quantum information.

The essential premise is that spacetime is not a smooth continuum but a microcausal lattice built from algebraic operators that obey sedenionic multiplication rules.

Each lattice site carries both external coordinates () and internal spinor degrees of freedom represented by 12 imaginary basis elements .

This framework replaces the Riemann curvature tensor with an operator commutator that quantizes curvature and naturally regularizes ultraviolet divergences.

A.2 Sedenionic Algebra and Covariant Operator

A general sedenion field is

The covariant derivative is defined as

where is the algebra-valued connection.

The

curvature operator (field strength) becomes

Because sedenions are non-associative, the

associator

enters naturally in the dynamics, encoding self-interaction among curvature channels.

This term regularizes high-energy divergences and provides the microscopic origin of vacuum energy.

A.3 Microcausal Lattice and Field Equations

The Universe is modeled as a causal lattice where each link corresponds to one commutator .

The effective Lagrangian density derived in

SQG Part I reads

with containing the associator corrections.

Variation of the total action

gives the operator field equation

which replaces Einstein’s equation.

In the weak-field limit this reduces to a generalized Proca-type equation with an effective algebraic mass term that yields the observed mass gap.

A.4 Emergence of Cosmological Constant and Quantized Λ

From

SQG Part II, the cosmological constant emerges as the global curvature invariant

with a slow scale evolution

This single parameter represents the relaxation rate of internal spinor curvature as the Universe expands.

The corresponding equation-of-state is

connecting dark-energy dynamics directly to information redistribution in the causal lattice.

A.6 Summary Table of Foundational Equations

For quick reference,

Table A1 compiles the principal equations defining the sedenionic gauge framework introduced in our earlier works (Parts I and II), with each equation paired to its physical meaning within the SQG foundation.

Table A1.

Key equations and interpretations.

Table A1.

Key equations and interpretations.

| Equation |

Physical Meaning |

|

Sedenionic covariant derivative |

|

Algebraic curvature operator |

|

Associator → self-interaction regularization |

| (1.4)–(1.6) |

Field Lagrangian and equations of motion |

|

Origin of cosmological constant |

|

Dynamic dark-energy law |

|

Equation of state |

|

Entropy–curvature correspondence |

A.8 Purpose of Inclusion

This appendix provides referees with a concise but self-contained summary of the mathematical foundation of SQG developed in our earlier works (Parts I and II).

It ensures that the current paper’s extensions—covering Λ-CDM comparison, baryon-acoustic structure, and quantum-informational thermodynamics—are directly traceable to these fundamental definitions and equations.

Appendix B. Framework and the Sedenionic Quantum Gravity Cosmology

B.1 Conceptual Overview

The conventional Λ-CDM model treats dark energy as a constant vacuum energy density that fills space uniformly and remains unchanged over cosmic time.

While empirically successful, this model provides no physical explanation for the magnitude or origin of Λ, leaving the cosmological constant problem unresolved.

By contrast, the Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG) framework interprets dark energy as a dynamical, quantized curvature invariant arising from the non-associative operator algebra of a 16-dimensional sedenionic gauge field.

In this view, Λ is not fundamental but emergent from the internal spinor dynamics of spacetime itself.

Complementing the previous comparisons,

Table A3 juxtaposes the Finsler–kinetic gas model with the SQG cosmology, outlining how the transition from geometric anisotropy to algebraic curvature quantization yields a deeper and more unified cosmological framework.

Table A2 enumerates the algebraic components of the sedenionic curvature operator

, detailing their decomposition into internal and external sectors and highlighting the structure constants that govern the curvature dynamics.

Table A2.

Comparison Between Standard Λ-CDM and Sedenionic Quantum Gravity.

Table A2.

Comparison Between Standard Λ-CDM and Sedenionic Quantum Gravity.

| Feature |

Standard Λ-CDM Model |

Sedenionic Quantum Gravity Model (this work) |

| Foundational basis |

General relativity + constant cosmological term Λ |

Non-associative gauge field theory on 16-D sedenionic algebra |

| Nature of Λ |

Constant vacuum energy; phenomenological parameter |

Quantized curvature invariant Λ = Tr([Dₘ, Dₙ]2) |

| Origin of dark energy |

Unknown; assigned ad hoc to fit observations |

Emergent from internal spinor curvature; finite and computable |

| Equation of state |

(exact constant) |

, with p ≈ 0.05 |

| Time dependence of Λ |

Constant in all epochs |

Slowly varying Λ(a) = Λ0 a−3ᵖ due to algebraic relaxation |

| Free parameters |

H0, Ωₘ, ΩΛ, Ωᵣ (plus nuisance parameters) |

Single new algebraic constant p embedded in curvature commutator |

| Underlying geometry |

4-D Riemannian spacetime |

4 external + 12 internal spinor axes = 16-D sedenionic manifold |

| Quantum consistency |

Classical effective theory; divergent QFT vacuum |

Ultraviolet-finite via non-associative associators; no renormalization |

| Entropy and information |

Entropy introduced phenomenologically; information loss in Hawking process |

Entropy = microstate count of internal spinors; global unitarity preserved |

| Black-hole thermodynamics |

Requires separate semiclassical treatment |

Emerges directly from algebraic curvature quantization |

| Predictive observables |

H(z) fit, CMB anisotropy, structure growth |

H(z), w(z), BAO phase drift Δφ(k), growth-index shift Δγ, CMB parity asymmetry |

| Ultraviolet behavior |

Divergent vacuum energy (120 orders mismatch) |

Finite Λ from discrete curvature spectrum |

| Physical interpretation of dark energy |

Fixed vacuum pressure causing acceleration |

Dynamical information–curvature equilibrium driving expansion |

| View of spacetime |

Continuous manifold with imposed curvature |

Quantized causal lattice of operator commutators |

| Philosophical scope |

Phenomenological cosmology |

Unified algebraic-geometric theory of matter, gravity, and information |

B.2 Interpretation

In summary, the Λ-CDM model successfully fits observational data but lacks a microphysical explanation for Λ.

It represents a descriptive framework constrained by empirical constants.

The Sedenionic Quantum Gravity theory, on the other hand, offers an explanatory framework in which the same invariant that governs gravitational curvature also dictates vacuum energy, information flow, and entropy.

Its predictive successes — a slowly varying Λ(a), the logarithmic BAO phase drift, and finite black-hole entropy — emerge from first principles rather than parameter tuning.

In this sense, SQG may be viewed as the quantum-geometric completion of Λ-CDM, reproducing the latter in the low-energy limit .

Appendix C. Comparison Between the Finsler–Kinetic Gas Model and the Sedenionic Quantum Gravity Framework

C.1 Conceptual Overview

Both the Finsler–kinetic gas cosmology and the Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (SQG) model seek to explain the observed cosmic acceleration without postulating a fundamental cosmological constant.

However, they differ profoundly in their underlying geometry, physical ontology, and predictive capability.

The Finsler–kinetic gas model modifies the metric structure of spacetime by introducing directional dependence in the line element , where . Cosmic acceleration emerges from anisotropic geometry and momentum-space curvature.

The Sedenionic Quantum Gravity model, in contrast, quantizes curvature itself through a non-associative 16-dimensional operator algebra, making dark energy a direct manifestation of algebraic curvature invariants rather than geometric anisotropy.

Table A3 presents a comparative summary of key cosmological observables predicted by the Λ-CDM, Finsler–kinetic gas, and Sedenionic Quantum Gravity models, emphasizing the distinctive and testable signatures of the algebraic curvature framework.

Table A3.

Comparison Between Finsler–Kinetic Gas and Sedenionic Quantum Gravity.

Table A3.

Comparison Between Finsler–Kinetic Gas and Sedenionic Quantum Gravity.

| Feature |

Finsler–Kinetic Gas Model (Pfeifer et al., 2025) |

Sedenionic Quantum Gravity (this work) |

| Foundational principle |

|

|

| Spacetime structure |

|

Quantized causal lattice: 4 external + 12 internal spinor axes |

| Primary dynamical entity |

of a kinetic gas coupled to the Finsler metric |

|

| Mechanism of acceleration |

Anisotropic momentum distribution produces effective negative pressure |

drives expansion |

| Nature of Λ |

Emergent geometric effect; no microphysical origin |

Quantized vacuum curvature; finite, discrete, and computable |

| Equation of state |

(phenomenological) |

(predictive; p ≈ 0.05) |

| Number of parameters |

Several free anisotropy and gas parameters |

Single algebraic constant p fixed by internal commutators |

| Entropy / information theory |

Absent; purely classical thermodynamic gas |

Built-in microstate counting; unitarity and black-hole entropy naturally arise |

| Quantum consistency |

Classical kinetic theory; no quantization of curvature |

Fully quantum-geometric; curvature operators define quantized spacetime |

| Ultraviolet behavior |

Divergent at high energy like GR |

Finite through non-associative associator regularization |

| Predictive observables |

|

Λ(a)=Λ0 a−3ᵖ; BAO phase drift Δφ(k); growth-index shift Δγ; CMB parity asymmetry |

| Physical interpretation of acceleration |

Geometric self-acceleration from anisotropy |

Energy–information equilibrium within algebraic curvature |

| Relation to Λ-CDM |

Mimics Λ phenomenologically |

Derives Λ dynamically; Λ-CDM emerges as p → 0 limit |

| Conceptual scope |

Classical geometric modification of GR |

Algebraic completion linking geometry, quantum field theory, and information physics |

C.2 Interpretation

In the Finsler–kinetic gas approach, cosmic acceleration arises as a kinematic by-product of anisotropic geometry, but it remains detached from quantum microphysics. The model’s multiple free parameters limit its predictive precision, and it lacks a consistent information-theoretic or thermodynamic foundation.

The Sedenionic Quantum Gravity model, in contrast, derives acceleration, entropy growth, and curvature quantization from the same algebraic principle. It requires only one new dimensionless parameter , directly related to the internal curvature coupling strength.

Whereas the Finsler model modifies geometry to imitate Λ, SQG generates Λ from first principles, bridging microphysical quantization and cosmological observation. Thus, SQG can be viewed as the algebraic completion of the geometric intuition underlying the Finsler framework—recovering its phenomenological successes while supplying the missing microscopic foundation.

References

- Penrose, R. (2005). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Jonathan Cape.

- Weinberg, S. (1972). Gravitation and Cosmology: Principles and Applications of the General Theory of Relativity. John Wiley & Sons.

- Misner, C. W., Thorne, K. S., & Wheeler, J. A. (1973). Gravitation. W. H. Freeman.

- Carroll, S. M. (2004). Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity. Addison Wesley.

- Wald, R. M. (1984). General Relativity. University of Chicago Press.

- Birrell, N. D., & Davies, P. C. W. (1982). Quantum Fields in Curved Space. Cambridge University Press.

- Hawking, S. W. (1975). Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 43(3), 199–220. [CrossRef]

- Mukhanov, V., & Winitzki, S. (2007). Introduction to Quantum Effects in Gravity. Cambridge University Press.

- Parker, L., & Toms, D. (2009). Quantum Field Theory in Curved Spacetime: Quantized Fields and Gravity. Cambridge University Press.

- Padmanabhan, T. (2010). Gravitation: Foundations and Frontiers. Cambridge University Press.

- Dodelson, S. (2003). Modern Cosmology. Academic Press.

- Liddle, A. R., & Lyth, D. H. (2000). Cosmological Inflation and Large-Scale Structure. Cambridge University Press.

- Peebles, P. J. E. (1993). Principles of Physical Cosmology. Princeton University Press.

- Kolb, E. W., & Turner, M. S. (1990). The Early Universe. Addison-Wesley.

- Weinberg, S. (2008). Cosmology. Oxford University Press.

- Riotto, A. (2002). Inflation and the theory of cosmological perturbations. arXiv preprint hep-ph/0210162. [CrossRef]

- Mukhanov, V. F. (2005). Physical Foundations of Cosmology. Cambridge University Press.

- Bardeen, J. M., Steinhardt, P. J., & Turner, M. S. (1983). Spontaneous creation of almost scale-free density perturbations in an inflationary universe. Physical Review D, 28(4), 679–693. [CrossRef]

- Guth, A. H., & Pi, S.-Y. (1982). Fluctuations in the new inflationary universe. Physical Review Letters, 49(15), 1110–1113. [CrossRef]

- Liddle, A. R., & Lyth, D. H. (2009). The Primordial Density Perturbation: Cosmology, Inflation and the Origin of Structure. Cambridge University Press.

- Durrer, R. (2008). The Cosmic Microwave Background. Cambridge University Press.

- Ma, C. P., & Bertschinger, E. (1995). Cosmological perturbation theory in the synchronous and conformal Newtonian gauges. The Astrophysical Journal, 455, 7. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W., & Sugiyama, N. (1996). Small-scale cosmological perturbations: An analytic approach. The Astrophysical Journal, 471, 542. [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, D. J., & Hu, W. (1998). Baryonic features in the matter transfer function. The Astrophysical Journal, 496, 605–614. [CrossRef]

- Peebles, P. J. E., & Yu, J. T. (1970). Primeval adiabatic perturbation in an expanding universe. The Astrophysical Journal, 162, 815.

- Sunyaev, R. A., & Zeldovich, Y. B. (1970). Small-scale fluctuations of relic radiation. Astrophysics and Space Science, 7(1), 3–19. [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. (2018). Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 641, A6.

- Durrer, R., & Maartens, R. (2008). Dark energy and modified gravity. General Relativity and Gravitation, 40(2–3), 301–328. [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S., & De Laurentis, M. (2011). Extended theories of gravity. Physics Reports, 509(4–5), 167–321. [CrossRef]

- Clifton, T., Ferreira, P. G., Padilla, A., & Skordis, C. (2012). Modified gravity and cosmology. Physics Reports, 513(1), 1–189. [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S., & Odintsov, S. D. (2011). Unified cosmic history in modified gravity: from F(R) theory to Lorentz non-invariant models. Physics Reports, 505(2–4), 59–144. [CrossRef]

- Sotiriou, T. P., & Faraoni, V. (2010). f(R) theories of gravity. Reviews of Modern Physics, 82(1), 451–497. [CrossRef]

- De Felice, A., & Tsujikawa, S. (2010). f(R) theories. Living Reviews in Relativity, 13, 3. [CrossRef]

- Guth, A. H. (1981). Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. Physical Review D, 23(2), 347–356. [CrossRef]

- Bamba, K., Capozziello, S., Nojiri, S., & Odintsov, S. D. (2012). Dark energy cosmology: the equivalent description via different theoretical models and cosmography tests. Astrophysics and Space Science, 342(1), 155–228. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).