Submitted:

12 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

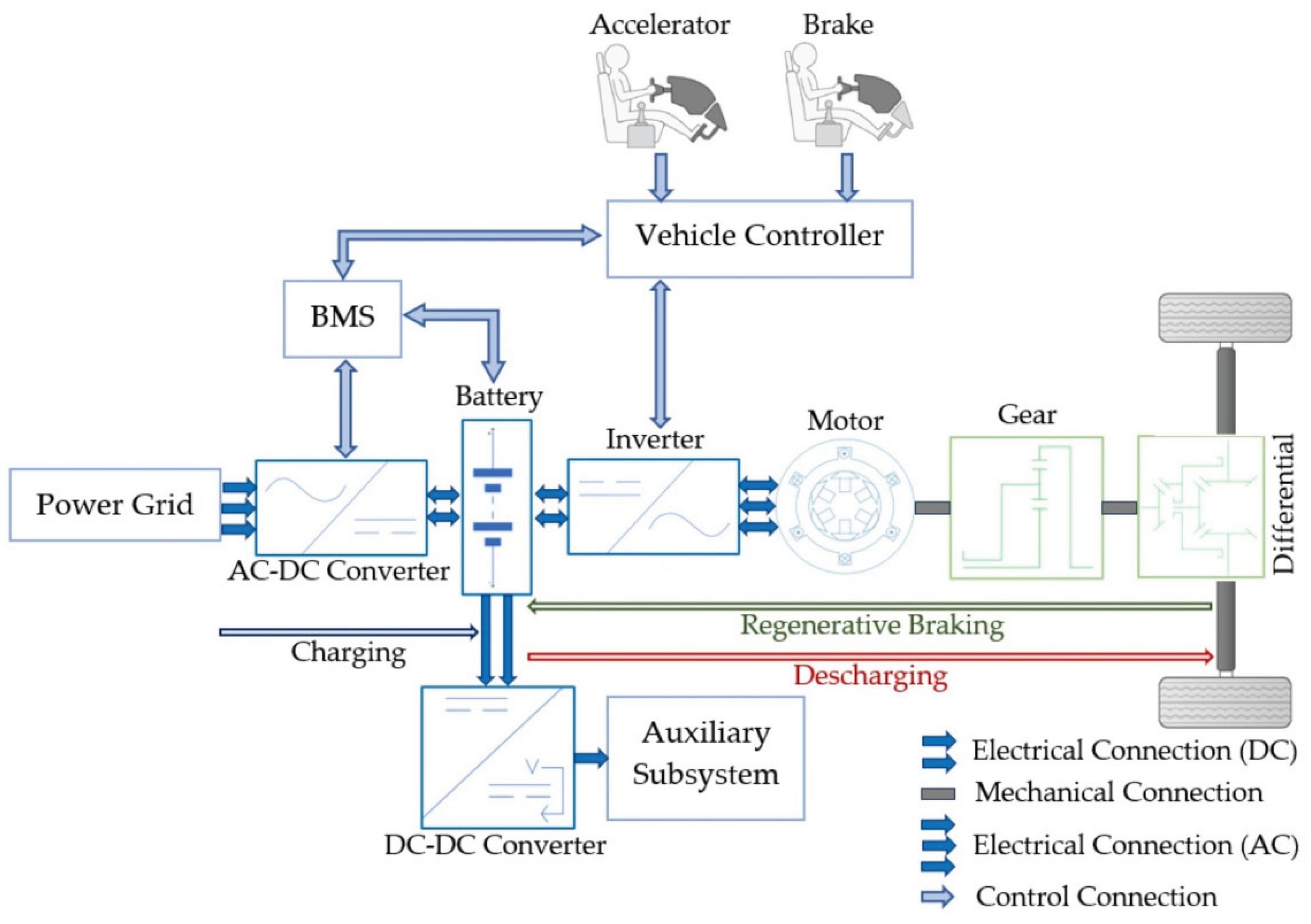

2. Background

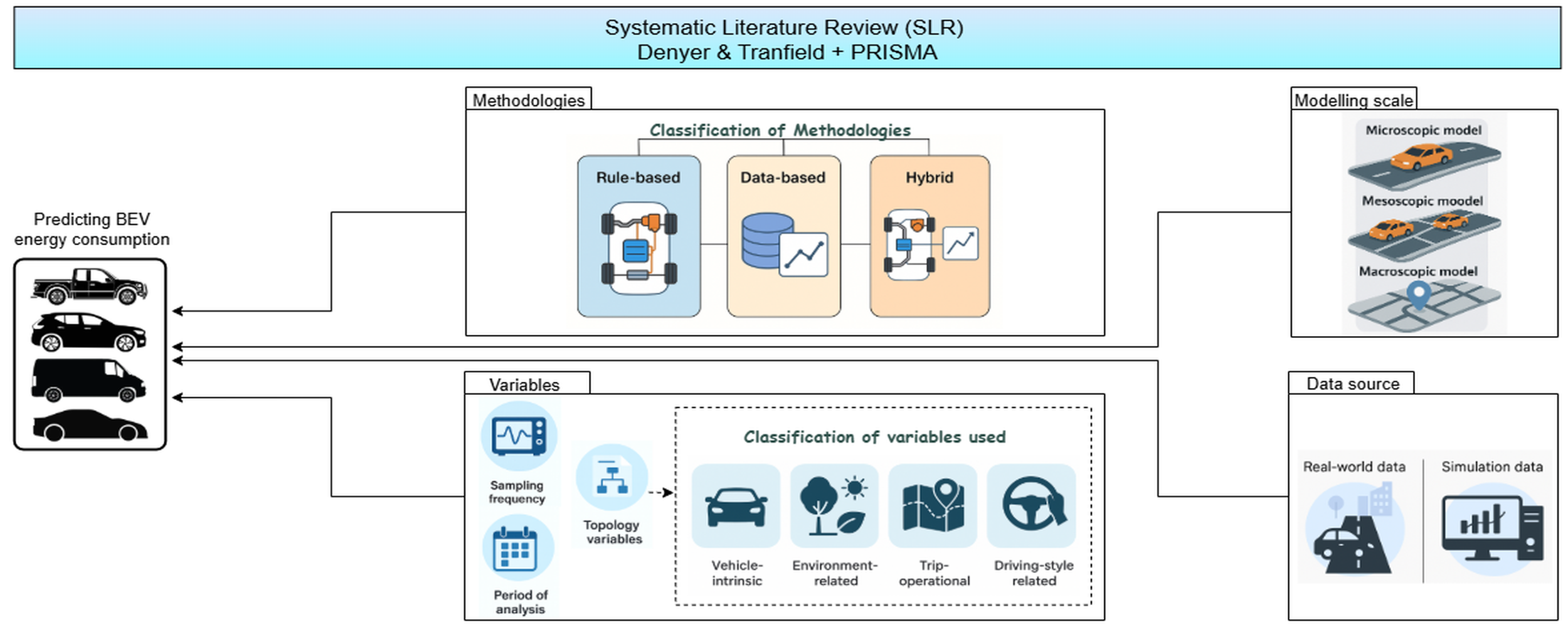

3. Method

3.1. Formulation of the Research Question

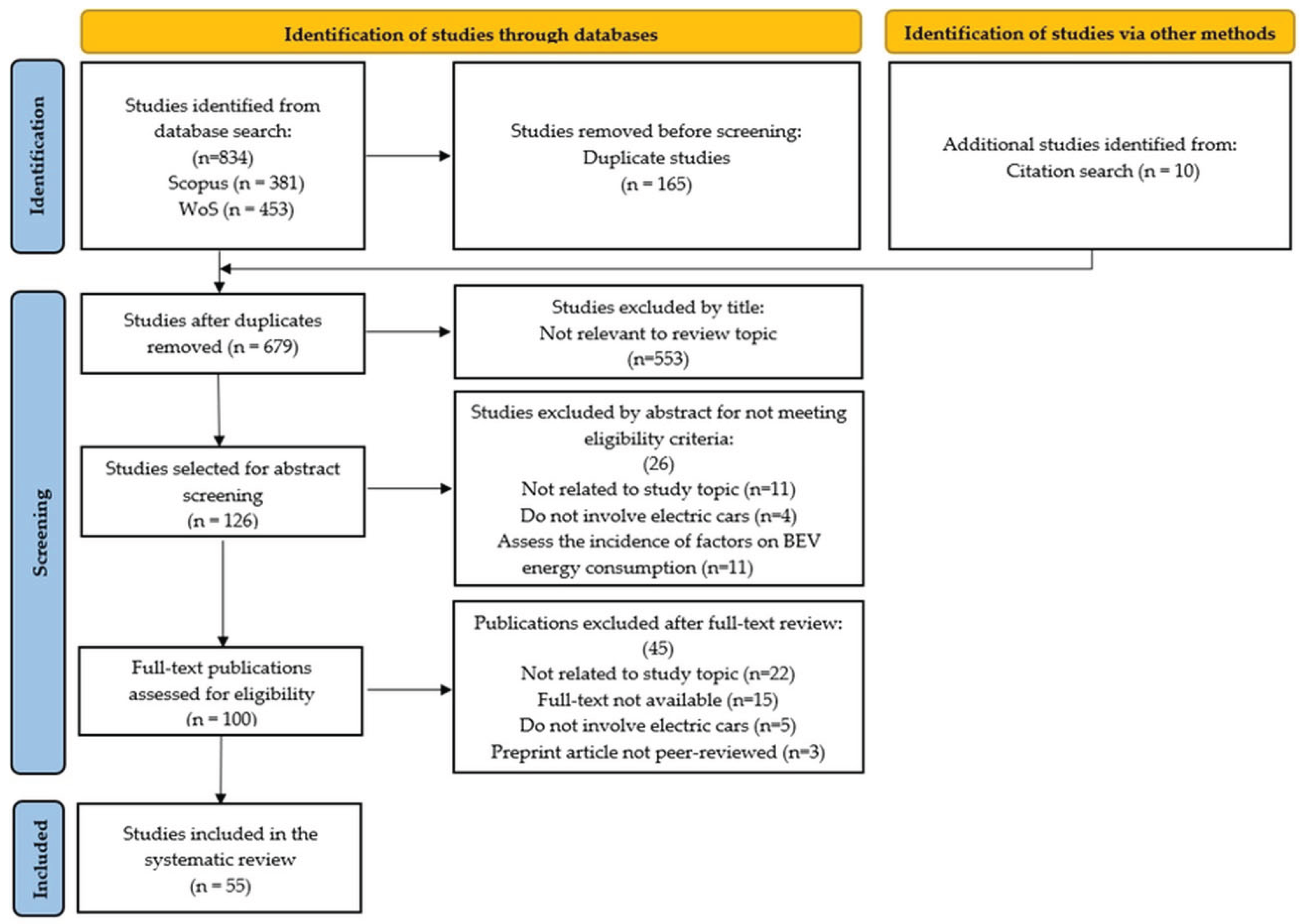

3.2. Locating Studies

3.3. Selection and Evaluation of Studies

3.4. Analysis and Synthesis

- Methodologies for predicting BEV energy consumption (rule-based models, data-driven models, and hybrids).

- Computational tools used.

- Evaluation metrics of the prediction model (accuracy).

- Topology of variables used, including intrinsic vehicle variables, environment-related variables (environmental and road characteristics), trip-related attributes (operational), and those associated with driving style.

- Sampling frequency of variables.

- Analysis period.

- Microscopic-, mesoscopic-, and macroscopic-scale models.

- BEV energy estimation models based on real-world data or simulation data.

3.5. Communication and Use of Results

4. Results

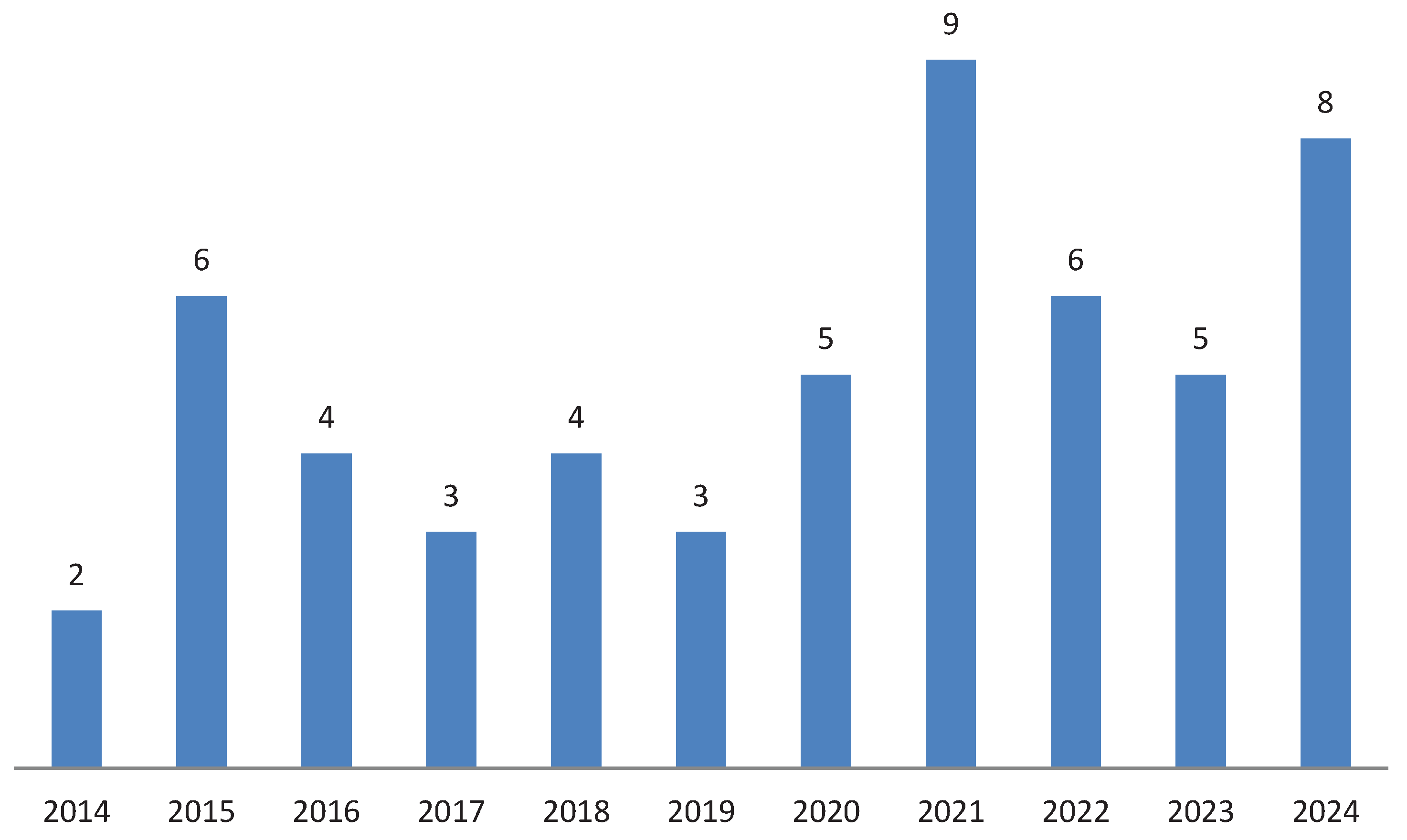

4.1. Year of Publication

4.2. Source of Publication

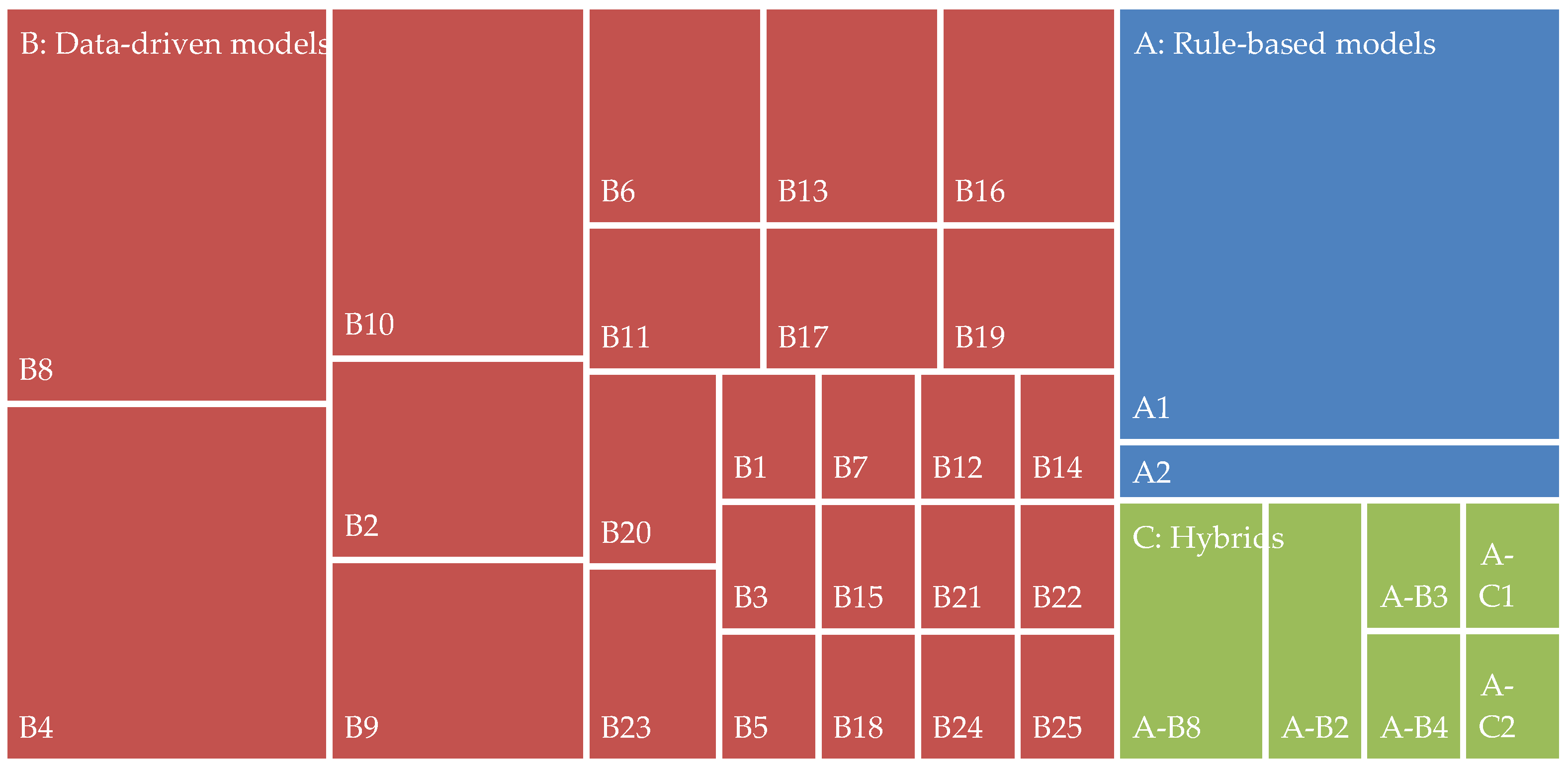

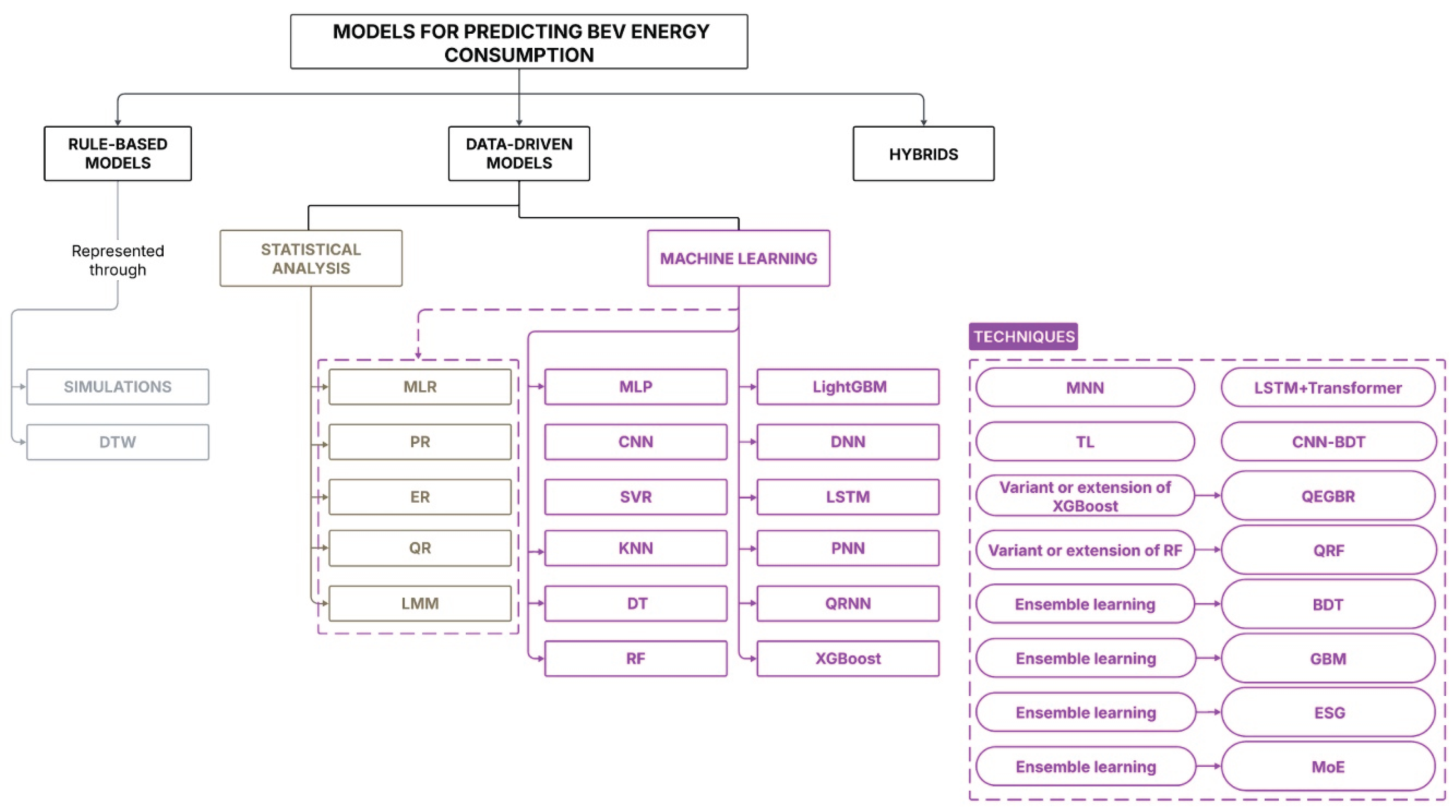

4.3. Axis of Analysis 1 – Methodology and Methods

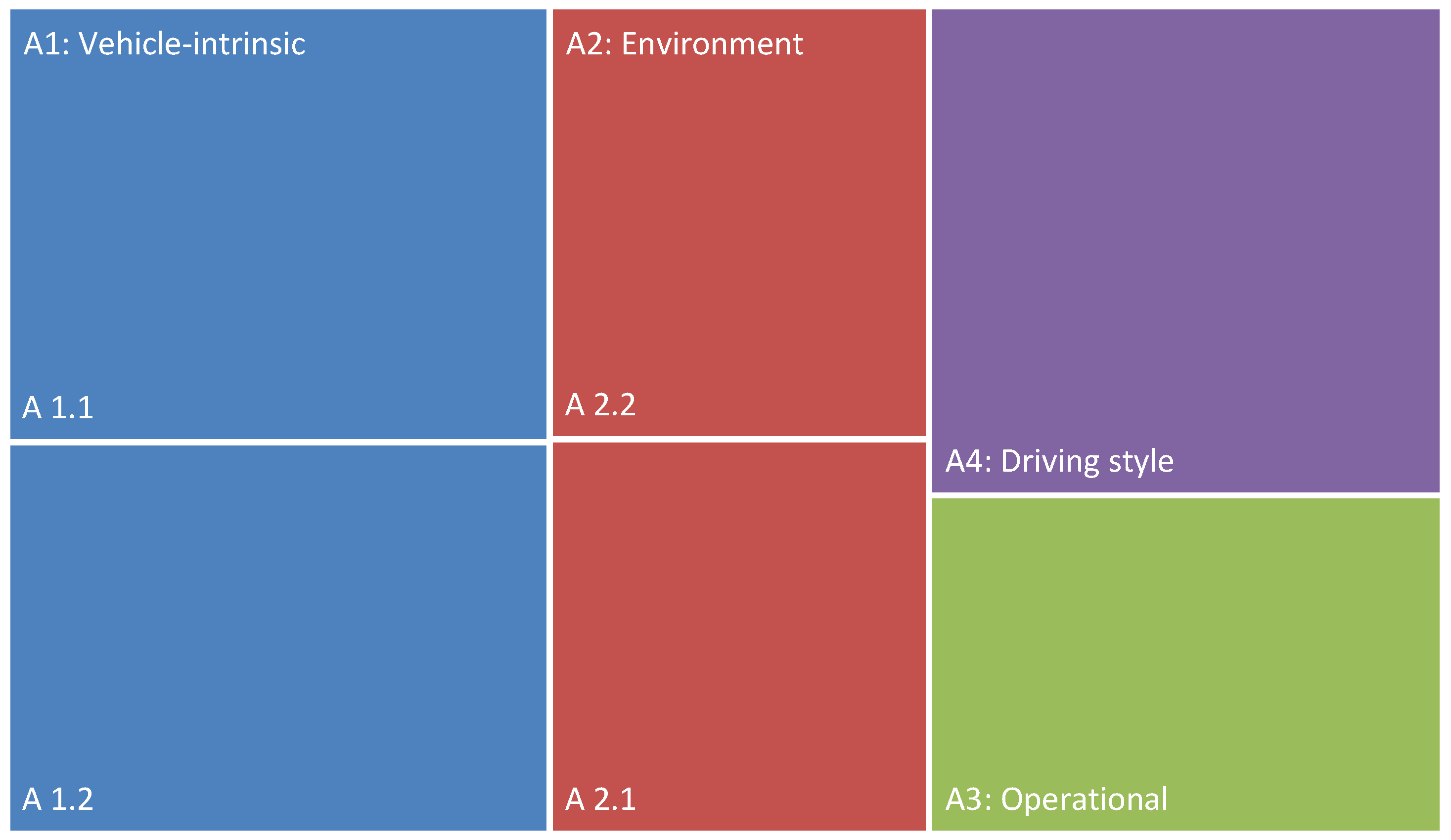

4.4. Axis of Analysis 2 – Variables Used

4.5. Axis of Analysis 3 – Modelling Scale

4.6. Axis of Analysis 4 – Data Source

5. Discussion and Suggestions for Future Work

6. Conclusions

- -

- There is a greater number of studies using data-driven energy modelling methods, most of which involve ML rather than traditional statistics, since they are capable of handling complex interactions in large datasets and predicting outcomes with higher accuracy. However, these models require larger sample sizes, which increases computational effort. Moreover, ML models often sacrifice interpretability compared with traditional statistics, as their main goal is to optimise prediction accuracy. Likewise, these models do not aim to understand the physical process of electricity generation and flow in BEVs, nor the interaction of powertrain components.

- -

- Rule-based models are more accurate than data-driven models; however, this accuracy depends on the level of model detail, which may lead to greater complexity, as they attempt to explain the interaction of powertrain components and their contribution to energy consumption. These models have been represented either through simulations or with DT, the latter having a broader scope as they integrate real-time data from the physical system, enabling continuous interaction and dynamic optimisation.

- -

- In hybrid models, a rule-based approach is generally developed to model vehicle dynamics, the powertrain, or the regenerative braking system. Then, by conveniently postulating the factors that may explain BEV energy consumption, predictive models are established either from a traditional statistical perspective or by employing ML models.

- -

- BEV energy consumption is dynamic and depends on vehicle-intrinsic variables (those related to vehicle dynamics and unit components), environment-related variables (ambient conditions and road characteristics), operational variables, and driving-style variables. When developing appropriate models for predicting BEV energy consumption, it is preferable to use real-world driving data rather than synthetic data or data obtained from laboratory tests, as this provides a more accurate estimation in line with actual journeys.

- -

- Microscopic-scale models are more accurate than mesoscopic- and macroscopic-scale models, as they allow for estimating instantaneous energy consumption. However, their high level of temporal and spatial granularity requires detailed vehicle models and driving cycles.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviation Full Term | |

| BDT | Bagged Decision Tree |

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicles |

| BMS | Battery Management System |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DNN | Deep Neural Networks |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| DTW | Digital Twin |

| ER | Exponential Regression |

| ESG | Ensemble Stacked Generalisation |

| FCEV | Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles |

| GBM | Gradient Boosting Machines |

| GHC | Anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning |

| ICEV | Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles |

| KNN | k-Nearest Neighbours |

| LightGBM | Light Gradient Boosting Machine |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory Networks |

| LMM | Linear Mixed Models |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| MNN | Multifunctional Neural Networks |

| MoE | Mixture of Experts |

| NKE | Negative Kinetic Energy |

| PKE | Positive Kinetic Energy |

| PNN | Probabilistic Neural Networks |

| PR | Polynomial Regression |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PHEV | Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles |

| QEGBR | Quantile Extreme Gradient Boosted Regression |

| QRF | Quantile Regression Forests |

| QRNN | Quantile Regression Neural Networks |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RLS | Recursive Least Squares |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| SoC | State of Charge |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

| TL | Transfer Learning |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), “Fast Facts: U.S. Transportation Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 1990-2022,” May 2024. Accessed: Mar. 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi?Dockey=P101AKR0.pdf.

- European Environment Agency (EEA), “Annual European Union greenhouse gas inventory 1990-2022 and inventory document 2024,” Copenhagen, Dec. 2024. Accessed: Mar. 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/annual-european-union-greenhouse-gas-inventory.

- German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA), “International passenger car markets clearly up after first quarter.” [Online]. Available: https://www.vda.de/en/press/press-releases/2023/230419_PM_International-passenger-car-markets-clearly-up-after-first-quarter.

- X. He et al., “Asia Pacific road transportation emissions, 1900-2050,” Faraday Discuss, vol. 226, pp. 53–73, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Moeletsi, “Socio-Economic Barriers to Adoption of Electric Vehicles in South Africa : Case Study of the Gauteng Province,” World Electric Vehicule Journal, vol. 12, no. 167, pp. 1–11, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Rodrigues, V. Albuquerque, J. Ferreira, M. Sales, and A. Martins, “Mining Electric Vehicle Adoption of Users,” World Electric Vehicule Journal, vol. 12, no. 233, pp. 1–31, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Jonas, C. Hunter, and G. Macht, “Quantifying the impact of traffic on the energy consumption of electric vehicles,” World Electric Vehicule Journal, vol. 13, no. 15, pp. 1–12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Huber, Q. De Clerck, C. De Cauwer, N. Sapountzoglou, T. Coosemans, and M. Messagie, “Vehicle to Grid Impacts on the Total Cost of Ownership for Electric Vehicle Drivers,” World Electric Vehicule Journal, vol. 12, no. 236, pp. 1–39, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Omahne, M. Knez, and M. Obrecht, “Social Aspects of Electric Vehicles Research — Trends and Relations to Sustainable Development Goals,” World Electric Vehicule Journal, vol. 12, no. 15, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Ivanova and A. C. Moreira, “Antecedents of Electric Vehicle Purchase Intention from the Consumer’s Perspective: A Systematic Literature Review,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 1–27, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Breuer, R. C. Samsun, D. Stolten, and R. Peters, “How to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution caused by light and heavy duty vehicles with battery-electric, fuel cell-electric and catenary trucks,” Environ Int, vol. 152, no. January, p. 106474, 2021. [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA), “Global EV Outlook 2024. Moving towards increased affordability,” Apr. 2024. Accessed: Mar. 11, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/a9e3544b-0b12-4e15-b407-65f5c8ce1b5f/GlobalEVOutlook2024.pdf.

- W. Achariyaviriya et al., “Estimating Energy Consumption of Battery Electric Vehicles Using Vehicle Sensor Data and Machine Learning Approaches,” Energies (Basel), vol. 16, no. 17, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. D. A. Guerrero, B. Bhattarai, R. Shrestha, T. L. Acker, and R. Castro, “Integrating electric vehicles into power system operation production cost models,” World Electric Vehicle Journal, vol. 12, no. 263, pp. 1–22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Schneidereit, T. Franke, M. Günther, and J. F. Krems, “Does range matter? Exploring perceptions of electric vehicles with and without a range extender among potential early adopters in Germany,” Energy Res Soc Sci, vol. 8, pp. 198–206, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Ghosh, “Possibilities and challenges for the inclusion of the electric vehicle (EV) to reduce the carbon footprint in the transport sector: A review,” Energies (Basel), vol. 13, no. 10, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Mastoi et al., “An in-depth analysis of electric vehicle charging station infrastructure, policy implications, and future trends,” Energy Reports, vol. 8, pp. 11504–11529, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Palmer, J. E. Tate, Z. Wadud, and J. Nellthorp, “Total cost of ownership and market share for hybrid and electric vehicles in the UK, US and Japan,” Appl Energy, vol. 209, no. July 2017, pp. 108–119, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Newbery and G. Strbac, “What is needed for battery electric vehicles to become socially cost competitive?,” Economics of Transportation, vol. 5, pp. 1–11, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. Noel, G. Zarazua de Rubens, B. K. Sovacool, and J. Kester, “Fear and loathing of electric vehicles: The reactionary rhetoric of range anxiety,” Energy Res Soc Sci, vol. 48, no. April 2018, pp. 96–107, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Capuder, D. Miloš Sprčić, D. Zoričić, and H. Pandžić, “Review of challenges and assessment of electric vehicles integration policy goals: Integrated risk analysis approach,” International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, vol. 119, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Wei, C. He, J. Li, and L. Zhao, “Online estimation of driving range for battery electric vehicles based on SOC-segmented actual driving cycle,” J Energy Storage, vol. 49, no. 104091, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Li, R. Long, H. Chen, and J. Geng, “A review of factors influencing consumer intentions to adopt battery electric vehicles,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 78, no. May 2016, pp. 318–328, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Yu, J. Yang, D. Wang, J. Shi, and J. Chen, “Energy consumption and increased EV range evaluation through heat pump scenarios and low GWP refrigerants in the new test procedure WLTP,” INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF REFRIGERATION, vol. 100, pp. 284–294, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Castillo-Calderón, D. Cordero-Moreno, and E. Larrodé Pellicer, “A Model-Driven Approach for Estimating the Energy Performance of an Electric Vehicle Used as a Taxi in an Intermediate Andean City,” Energies (Basel), vol. 17, no. 23, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Yavasoglu, Y. E. Tetik, and K. Gokce, “Implementation of machine learning based real time range estimation method without destination knowledge for BEVs,” Energy, vol. 172, pp. 1179–1186, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Fiori, K. Ahn, and H. A. Rakha, “Microscopic series plug-in hybrid electric vehicle energy consumption model: Model development and validation,” Transp Res D Transp Environ, vol. 63, pp. 175–185, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. N. Genikomsakis, G. Mitrentsis, D. Savvidis, and C. S. Ioakimidis, “Energy consumption model of electric scooter for routing applications: Experimental validation,” in IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Proceedings, ITSC, ERA Net-Zero Energy Efficiency on City Districts, NZED’ Unit, Research Institute for Energy, University of Mons, Mons, Belgium: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2017, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, G. Wu, R. Sun, A. Dubey, A. Laszka, and P. Pugliese, “A Review and Outlook on Energy Consumption Estimation Models for Electric Vehicles,” SAE International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, Energy, Environment, & Policy, vol. 2, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. C. López and R. Á. Fernández, “Predictive model for energy consumption of battery electric vehicle with consideration of self-uncertainty route factors,” J Clean Prod, vol. 276, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Vepsäläinen, K. Otto, A. Lajunen, and K. Tammi, “Computationally efficient model for energy demand prediction of electric city bus in varying operating conditions,” Energy, vol. 169, pp. 433–443, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Fiori, K. Ahn, and H. A. Rakha, “Power-based electric vehicle energy consumption model: Model development and validation,” Appl Energy, vol. 168, pp. 257–268, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Modi, J. Bhattacharya, and P. Basak, “Estimation of energy consumption of electric vehicles using Deep Convolutional Neural Network to reduce driver’s range anxiety,” ISA Trans, vol. 98, no. xxxx, pp. 454–470, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Fotouhi, N. Shateri, D. S. Laila, and D. J. Auger, “Electric vehicle energy consumption estimation for a fleet management system,” Int J Sustain Transp, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 40–54, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Kirschstein and F. Meisel, “GHG-emission models for assessing the eco-friendliness of road and rail freight transports,” Transportation Research Part B: Methodological, vol. 73, pp. 13–33, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhai, L. Zhang, G. Song, X. Li, and L. Yu, “Modeling energy consumption for battery electric vehicles based on in-use vehicle trajectories,” Transp Res D Transp Environ, vol. 137, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, F. Yang, X. Ke, Z. Liu, and C. Yuan, “Predictive modeling of energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions from autonomous electric vehicle operations,” Appl Energy, vol. 254, no. March, p. 113597, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, D. Zhao, Q. Meng, G. P. Ong, and D.-H. Lee, “Network-level energy consumption estimation for electric vehicles considering vehicle and user heterogeneity,” TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH PART A-POLICY AND PRACTICE, vol. 132, pp. 30–46, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Yılmaz and B. Yagmahan, “Electric vehicle energy consumption prediction for unknown route types using deep neural networks by combining static and dynamic data,” Appl Soft Comput, vol. 167, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, S. Li, and Y. Li, “A Review on Quantitative Energy Consumption Models from Road Transportation,” Energies (Basel), vol. 17, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhang and E. Yao, “Mesoscopic model framework for estimating electric vehicles’ energy consumption,” Sustain Cities Soc, vol. 47, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Rakha, H. Yue, and F. Dion, “VT-Meso model framework for estimating hotstabilized light-duty vehicle fuel consumption and emission rates,” Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering, vol. 38, no. 11, pp. 1274–1286, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Pan, W. Fang, and W. Zhang, “Development of an energy consumption prediction model for battery electric vehicles in real-world driving: A combined approach of short-trip segment division and deep learning,” J Clean Prod, vol. 400, no. 136742, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Ye, G. Wu, K. Boriboonsomsin, and M. J. Barth, “A Hybrid Approach to Estimating Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption for Ecodriving Applications,” in 2016 IEEE 19TH International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA: IEEE, 2016, pp. 719–724.

- A. Di Martino, S. M. Miraftabzadeh, and M. Longo, “Strategies for the Modelisation of Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption: A Review,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 21, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Alanazi, “Electric Vehicles: Benefits, Challenges, and Potential Solutions for Widespread Adaptation,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 10, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Ansarey, M. Shariat Panahi, H. Ziarati, and M. Mahjoob, “Optimal energy management in a dual-storage fuel-cell hybrid vehicle using multi-dimensional dynamic programming,” J Power Sources, vol. 250, pp. 359–371, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Baker and S. M. Weeks, “An overview of systematic review,” Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 454–458, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Siddaway, A. M. Wood, and L. V. Hedges, How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses, vol. 70, no. January. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Denyer and D. Tranfield, “Producing a Systematic Review,” The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, pp. 671–689, 2009.

- K. Liu, T. Yamamoto, and T. Morikawa, “Impact of road gradient on energy consumption of electric vehicles,” Transp Res D Transp Environ, vol. 54, pp. 74–81, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Yang, M. Li, Y. Lin, and T. Q. Tang, “Electric vehicle’s electricity consumption on a road with different slope,” Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, vol. 402, pp. 41–48, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Graser, J. Asamer, and W. Ponweiser, “The elevation factor: Digital elevation model quality and sampling impacts on electric vehicle energy estimation errors,” in 2015 International Conference on Models and Technologies for Intelligent Transportation Systems, MT-ITS 2015, 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA: IEEE, 2015, pp. 81–86. [CrossRef]

- A. Desreveaux, A. Bouscayrol, R. Trigui, E. Castex, and J. Klein, “Impact of the Velocity Profile on Energy Consumption of Electric Vehicles,” IEEE Trans Veh Technol, vol. 68, no. 12, pp. 11420–11426, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Wager, J. Whale, and T. Braunl, “Driving electric vehicles at highway speeds : The effect of higher driving speeds on energy consumption and driving range for electric vehicles in Australia,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 63, pp. 158–165, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Donkers, D. Yang, and M. Viktorovic, “Influence of driving style, infrastructure, weather and traffic on electric vehicle performance,” TRANSPORTATION RESEARCH PART D-TRANSPORT AND ENVIRONMENT, vol. 88, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Wang, K. Liu, T. Yamamoto, and T. Morikawa, “Improving Estimation Accuracy for Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption Considering the Effects of Ambient Temperature,” in Energy Procedia, J. Yan, F. Sun, S. K. Chou, U. Desideri, H. Li, P. Campana, and R. Xiong, Eds., in Energy Procedia, vol. 105. SARA BURGERHARTSTRAAT 25, PO BOX 211, 1000 AE AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS: ELSEVIER SCIENCE BV, 2017, pp. 2904–2909. [CrossRef]

- K. Liu, J. Wang, T. Yamamoto, and T. Morikawa, “Exploring the interactive effects of ambient temperature and vehicle auxiliary loads on electric vehicle energy consumption,” Appl Energy, vol. 227, no. SI, pp. 324–331, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Iora and L. Tribioli, “Effect of ambient temperature on electric vehicles’ energy consumption and range: Model definition and sensitivity analysis based on Nissan Leaf data,” World Electric Vehicle Journal, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Lee, J. Song, Y. Lim, and S. Park, “Energy consumption evaluation of passenger electric vehicle based on ambient temperature under Real-World driving conditions,” Energy Convers Manag, vol. 306, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Unni and S. Thale, “Influence of Auxiliary Loads on the Energy Consumption of Electric Vehicle - A Case Study,” in 2021 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference, ITEC-India 2021, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumari, S. Ghosh, A. R. Hota, and S. Mukhopadhyay, “Energy Consumption of Electric Vehicles: Effect of Lateral Dynamics,” in IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Wager, M. P. McHenry, J. Whale, and T. Bräunl, “Testing energy efficiency and driving range of electric vehicles in relation to gear selection,” Renew Energy, vol. 62, pp. 303–312, 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Hinov, P. Punov, B. Gilev, and G. Vacheva, “Model-Based Estimation of Transmission Gear Ratio for Driving Energy Consumption of an EV,” Electronics (Basel), vol. 10, no. 13, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Schweizer, M. Stöckl, R. Tutunaru, and U. Holzhammer, “Influence of heating, air conditioning and vehicle automation on the energy and power demand of electromobility,” Energy Conversion and Management: X, vol. 20, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Sagoian, B. O. Varga, and S. Solodushkin, “Energy Consumption Prediction of Electric Vehicle Air Conditioning System Using Artificial Intelligence,” in Proceedings - 2021 Ural Symposium on Biomedical Engineering, Radioelectronics and Information Technology, USBEREIT 2021, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2021, pp. 379 – 382. [CrossRef]

- A. Doyle and T. Muneer, “Energy consumption and modelling of the climate control system in the electric vehicle,” Energy Exploration and Exploitation, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 519–543, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Sarrafan, K. M. Muttaqi, D. Sutanto, and G. Town, “Improved Estimation of the Impact of Regenerative Braking on Electric Vehicle Range,” in 2016 IEEE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON POWER SYSTEM TECHNOLOGY (POWERCON), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA: IEEE, 2016.

- G. Sandrini, M. Gadola, D. Chindamo, A. Candela, and P. Magri, “Exploring the Impact of Vehicle Lightweighting in Terms of Energy Consumption: Analysis and Simulation,” Energies (Basel), vol. 16, no. 13, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Yi and P. H. Bauer, “Effects of environmental factors on electric vehicle energy consumption: A sensitivity analysis,” IET Electrical Systems in Transportation, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 3–13, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Suryavanshi and P. M. Ghanegaonkar, “Repercussion of effect of different drive cycles on evaluation of electrical consumption for electric four-wheeler to achieve optimal performance of electric vehicle,” Energy Storage, vol. 5, no. 7, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Merchán, L. Gonzalez, and J. Espinoza, “Energy Efficiency of an Electric Vehicle in a Latin American Intermediate City,” in Smart Energy Systems and Technology (SEST 2018), 2018, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- I. Komorska, A. Puchalski, A. Niewczas, M. Ślęzak, and T. Szczepański, “Adaptive driving cycles of evs for reducing energy consumption,” Energies (Basel), vol. 14, no. 9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Castillo-Calderón, D. Díaz-Sinche, R. Carrión, A. Sigüenza, and J. Cabrera, “Energy Consumption of a Battery Electric Vehicle Used for City-Airport Trips: a Case Study in an Andean Region,” in 2023 IEEE Seventh Ecuador Technical Chapters Meeting (ECTM), IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- J. Diaz, J. Guillén, D. Arroyo, and M. Maks, “Performance Evaluation of an Electric Vehicle in Real Operating Conditions of Quito , Ecuador,” in 4th International Congress of Automotive and Transport Engineering (AMMA 2018), 2018, pp. 328–337. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu, Z. Zhang, and J. Zhang, “Research on the interaction between energy consumption and power battery life during electric vehicle acceleration,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Page, J. E. McKenzie, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, and T. C. Hoffmann, “The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews,” Rev Esp Cardiol, vol. 74, no. 9, pp. 790–799, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Yao, M. Wang, Y. Song, and Y. Zhang, “Estimating energy consumption on the basis of microscopic driving parameters for electric vehicles,” Transp Res Rec, vol. 2454, no. 2454, pp. 84–91, 2014. [CrossRef]

- N. Chang, D. Baek, and J. Hong, “Power Consumption Characterization, Modeling and Estimation of Electric Vehicles,” in 2014 IEEE/ACM INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPUTER-AIDED DESIGN (ICCAD), in ICCAD-IEEE ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design. 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA: IEEE, 2014, pp. 175–182.

- J. Maldonado-Correa, S. Martín-Martínez, E. Artigao, and E. Gómez-Lázaro, “Using SCADA data for wind turbine condition monitoring: A systematic literature review,” Energies (Basel), vol. 13, no. 12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. V Limaye, V. K. Rao, K. Limaye V, and V. K. Rao, “Methodology for Battery Capacity Sizing of Battery Electric Vehicles,” in 2019 IEEE TRANSPORTATION ELECTRIFICATION CONFERENCE (ITEC-INDIA), 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2019. [CrossRef]

- I. Miri, A. Fotouhi, and N. Ewin, “Electric vehicle energy consumption modelling and estimation—A case study,” Int J Energy Res, pp. 1–20, 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. Kocaarslan, M. A. Zehir, E. Uzun, E. C. Uzun, M. E. Korkmaz, and Y. Cakiroglu, “High-Fidelity Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption Modelling and Investigation of Factors in Driving on Energy Consumption,” in Proceedings - 2022 IEEE 4th Global Power, Energy and Communication Conference, GPECOM 2022, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2022, pp. 227–231. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, I. Besselink, and H. Nijmeijer, “Electric vehicle energy consumption modelling and prediction based on road information,” World Electric Vehicle Journal, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 447–458, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- X. Wu, D. Freese, A. Cabrera, and W. A. Kitch, “Electric vehicles’ energy consumption measurement and estimation,” Transp Res D Transp Environ, vol. 34, pp. 52–67, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- F. Janković, L. Šćekić, and S. Mujović, “Matlab/Simulink Based Energy Consumption Prediction of Electric Vehicles,” in 2021 21st International Symposium on Power Electronics (Ee), IEEE, Dec. 2021, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- J. Guo, Y. Jiang, Y. Yu, and W. Liu, “A novel energy consumption prediction model with combination of road information and driving style of BEVs,” Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, vol. 42, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, I. Besselink, and H. Nijmeijer, “Battery electric vehicle energy consumption modelling for range estimation,” Int. J. Electric and Hybrid Vehicles, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 79–102, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Luin, S. Petelin, and F. Al-Mansour, “Microsimulation of electric vehicle energy consumption,” Energy, vol. 174, pp. 24–32, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Asamer, A. Graser, B. Heilmann, and M. Ruthmair, “Sensitivity analysis for energy demand estimation of electric vehicles,” Transp Res D Transp Environ, vol. 46, pp. 182–199, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Alhanouti and F. Gauterin, “A Generic Model for Accurate Energy Estimation of Electric Vehicles,” Energies (Basel), vol. 17, no. 2, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, Y. Zou, T. Zhou, X. Zhang, and Z. Xu, “Energy consumption prediction of electric vehicles based on digital twin technology,” World Electric Vehicle Journal, vol. 12, no. 4, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie et al., “Microsimulation of electric vehicle energy consumption and driving range,” Appl Energy, vol. 267, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Miraftabzadeh, M. Longo, and F. Foiadelli, “Estimation model of total energy consumptions of electrical vehicles under different driving conditions,” Energies (Basel), vol. 14, no. 4, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Qi and Y. Zhang, “Data-driven Macroscopic Energy Consumption Estimation for Electric Vehicles with Different Information Availability,” in 2016 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence, IEEE Computer Society, Conference Publishing Services, 2016, pp. 1214–1219. [CrossRef]

- X. Qi, G. Wu, K. Boriboonsomsin, and M. J. Barth, “Data-driven decomposition analysis and estimation of link-level electric vehicle energy consumption under real-world traffic conditions,” Transp Res D Transp Environ, vol. 64, pp. 36–52, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Jimenez, J. C. Amarillo, J. E. Naranjo, F. Serradilla, and A. Diaz, “Energy Consumption Estimation in Electric Vehicles Considering Driving Style,” in IEEE 18th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2015, pp. 101–106. [CrossRef]

- P. Petersen, T. Rudolf, and E. Sax, “A Data-driven Energy Estimation based on the Mixture of Experts Method for Battery Electric Vehicles,” in International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems, VEHITS - Proceedings, Science and Technology Publications, Lda, 2022, pp. 384–390. [CrossRef]

- F. Foiadelli, M. Longo, and S. Miraftabzadeh, “Energy Consumption Prediction of Electric Vehicles Based on Big Data Approach,” in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2018 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC / I&CPS Europe), IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- I. Ullah, K. Liu, T. Yamamoto, R. E. Al Mamlook, and A. Jamal, “A comparative performance of machine learning algorithm to predict electric vehicles energy consumption: A path towards sustainability,” Energy and Environment, vol. 33, no. 8, pp. 1583–1612, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Mądziel, “Energy Modeling for Electric Vehicles Based on Real Driving Cycles: An Artificial Intelligence Approach for Microscale Analyses,” Energies (Basel), vol. 17, no. 5, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Maity and S. Sarkar, “Data-Driven Probabilistic Energy Consumption Estimation for Battery Electric Vehicles with Model Uncertainty,” Jul. 2023, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2307.00469.

- Q. Zhu, Y. Huang, C. F. Lee, P. Liu, J. Zhang, and T. Wik, “Predicting Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption from Field Data Using Machine Learning,” IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Cabani, P. Zhang, R. Khemmar, and J. Xu, “Enhancement of energy consumption estimation for electric vehicles by using machine learning,” IAES International Journal of Artificial Intelligence (IJ-AI, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 215–223, 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Ullah, K. Liu, T. Yamamoto, M. Zahid, and A. Jamal, “Electric vehicle energy consumption prediction using stacked generalization: an ensemble learning approach,” Int J Green Energy, vol. 18, no. 9, pp. 896–909, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Pokharel, P. Sah, and D. Ganta, “Improved prediction of total energy consumption and feature analysis in electric vehicles using machine learning and shapley additive explanations method,” World Electric Vehicle Journal, vol. 12, no. 3, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Fukushima, T. Yano, S. Imahara, H. Aisu, Y. Shimokawa, and Y. Shibata, “Prediction of energy consumption for new electric vehicle models by machine learning,” IET Intelligent Transport Systems, vol. 12, no. 9, pp. 1174–1180, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. De Cauwer, J. Van Mierlo, and T. Coosemans, “Energy consumption prediction for electric vehicles based on real-world data,” Energies (Basel), vol. 8, no. 8, pp. 8573–8593, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. De Cauwer, W. Verbeke, T. Coosemans, S. Faid, and J. Van Mierlo, “A data-driven method for energy consumption prediction and energy-efficient routing of electric vehicles in real-world conditions,” Energies (Basel), vol. 10, no. 5, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Z. Qi, J. Yang, R. Jia, and F. Wang, “Investigating real-world energy consumption of electric vehicles: A case study of Shanghai,” in Procedia Computer Science, Elsevier B.V., 2018, pp. 367–376. [CrossRef]

- Z. Feng, J. Zhang, H. Jiang, X. Yao, Y. Qian, and H. Zhang, “Energy consumption prediction strategy for electric vehicle based on LSTM-transformer framework,” Energy, vol. 302, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Grubwinkler and M. Lienkamp, “Energy prediction for EVs using support vector regression methods,” Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol. 323, pp. 769–780, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, Z. Wang, P. Liu, and Z. Zhang, “Energy consumption analysis and prediction of electric vehicles based on real-world driving data,” Appl Energy, vol. 275, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Liu, F. Gao, J. Zhao, and W. Zhou, “Prediction of Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption in an Intelligent and Connected Environment,” Promet - Traffic and Transportation, vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 662–680, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wu, X. Chen, and Y. Jiang, “Prediction of Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption by Combining Real Vehicle Data and Machine Learning Methods,” Medicon Engineering Themes, vol. 4, no. 3, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. P. Adedeji, “Electric vehicles survey and a multifunctional artificial neural network for predicting energy consumption in all-electric vehicles,” Results in Engineering, vol. 19, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Petkevicius, S. Saltenis, A. Civilis, and K. Torp, “Probabilistic Deep Learning for Electric-Vehicle Energy-Use Prediction,” in ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, Association for Computing Machinery, Aug. 2021, pp. 85–95. [CrossRef]

- S. Modi and J. Bhattacharya, “A system for electric vehicle’s energy-aware routing in a transportation network through real-time prediction of energy consumption,” Complex and Intelligent Systems, vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 4727–4751, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Modi, J. Bhattacharya, and P. Basak, “Convolutional neural network–bagged decision tree: a hybrid approach to reduce electric vehicle’s driver’s range anxiety by estimating energy consumption in real-time,” Soft comput, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 2399–2416, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhang and E. Yao, “Electric vehicles’ energy consumption estimation with real driving condition data,” Transp Res D Transp Environ, vol. 41, pp. 177–187, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Mediouni, A. Ezzouhri, Z. Charouh, K. El Harouri, S. El Hani, and M. Ghogho, “Energy Consumption Prediction and Analysis for Electric Vehicles: A Hybrid Approach,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 17, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, K. Liu, and T. Yamamoto, “Improving electricity consumption estimation for electric vehicles based on sparse GPS observations,” Energies (Basel), vol. 10, no. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Shen et al., “Electric Vehicle Energy Consumption Estimation with Consideration of Longitudinal Slip Ratio and Machine-Learning-Based Powertrain Efficiency,” in IFAC-PapersOnLine, Elsevier B.V., 2022, pp. 158–163. [CrossRef]

- C. Liu, “Energy Consumption Prediction and Optimization of Electric Vehicles Based on RLS and Improved SOA,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 38180–38191, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Ganaie, M. Hu, A. K. Malik, M. Tanveer, and P. N. Suganthan, “Ensemble deep learning: A review,” Oct. 01, 2022, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- E. Abbasi, M. E. Shiri, and M. Ghatee, “A regularized root-quartic mixture of experts for complex classification problems,” Knowl Based Syst, vol. 110, pp. 98–109, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Yang, J. Wu, Y. Du, Y. He, and X. Chen, “Ensemble Learning for Short-Term Traffic Prediction Based on Gradient Boosting Machine,” J Sens, vol. 2017, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Tao, H. Zhang, A. Liu, and A. Y. C. Nee, “Digital Twin in Industry: State-of-the-Art,” IEEE Trans Industr Inform, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 2405–2415, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Ley, R. K. Martin, A. Pareek, A. Groll, R. Seil, and T. Tischer, “Machine learning and conventional statistics: making sense of the differences,” Mar. 01, 2022, Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. [CrossRef]

- C. De Cauwer, W. Verbeke, J. Van Mierlo, and T. Coosemans, “A Model for Range Estimation and Energy-Efficient Routing of Electric Vehicles in Real-World Conditions,” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 2787–2800, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Pollák et al., “Promotion of electric mobility in the European Union—overview of project PROMETEUS from the perspective of cohesion through synergistic cooperation on the example of the catching-up region,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 1–26, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Basso, B. Kulcsár, B. Egardt, P. Lindroth, and I. Sanchez-Diaz, “Energy consumption estimation integrated into the Electric Vehicle Routing Problem,” Transp Res D Transp Environ, vol. 69, pp. 141–167, Apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Kruppok, R. Kriesten, and E. Sax, “Calculation of route-dependent energysaving potentials to optimize EV’s range,” 2018, pp. 1349–1363. [CrossRef]

- X. Yuan, C. Zhang, G. Hong, X. Huang, and L. Li, “Method for evaluating the real-world driving energy consumptions of electric vehicles,” Energy, vol. 141, pp. 1955–1968, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Severino et al., “Real-Time Highly Resolved Spatial-Temporal Vehicle Energy Consumption Estimation Using Machine Learning and Probe Data,” 2022.

- K. Unni and S. Thale, “Energy Consumption Analysis for the Prediction of Battery Residual Energy in Electric Vehicles,” Engineering, Technology and Applied Science Research, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 11011–11019, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Díaz, F. Serradilla, E. Naranjo, J. Anaya, and F. Jiménez, “Modeling the Driving Behavior of Electric Vehicles Using Smartphones and Neural Networks,” IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 44–53, 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Ristiana, A. S. Rohman, C. Machbub, A. Purwadi, and E. Rijanto, “A new approach of EV modeling and its control applications to reduce energy consumption,” IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 141209–141225, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Lai, W. Zhang, and H. Liu, “A Preference-aware Meta-optimization Framework for Personalized Vehicle Energy Consumption Estimation,” in Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Association for Computing Machinery, Aug. 2023, pp. 4346–4356. [CrossRef]

| Category of search terms | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | (“electric vehicl*” OR “electric car*”)1 |

| 2 | (“energy consumption” OR “power consumption”) |

| 3 | (“prediction” OR “estimation” OR “forecasting”) |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY ("electric vehicl*" OR "electric car*" AND "energy consumption" OR "power consumption" AND "prediction" OR "estimation" OR "forecasting") AND LANGUAGE (english) AND SUBJAREA (comp) OR SUBJAREA (ener) OR SUBJAREA (engi) OR SUBJAREA (envi) OR SUBJAREA (math) OR SUBJAREA (phys) |

| Journal | Number of articles | JCR | SJR | h5 |

Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile | IF | Quartile | IF | ||||

| Applied Energy | 3 | Q1 | 10.1 | Q1 | 2.82 | 189 | 4037.32 |

| Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment | 5 | Q1 | 7.4 | Q1 | 2.33 | 99 | 1706.96 |

| Energy | 2 | Q1 | 9.0 | Q1 | 2.11 | 165 | 1566.68 |

| Sustainable Cities and Society | 1 | Q1 | 10.5 | Q1 | 2.55 | 147 | 983.98 |

| Energies | 9 | Q3 | 3.0 | Q1 | 0.65 | 137 | 534.30 |

| Applied Soft Computing | 1 | Q1 | 7.2 | Q1 | 1.84 | 133 | 440.50 |

| IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification | 1 | Q1 | 7.2 | Q1 | 2.77 | 75 | 373.95 |

| Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments | 1 | Q1 | 7.1 | Q1 | 1.57 | 90 | 250.81 |

| IEEE Access | 1 | Q2 | 3.4 | Q1 | 0.96 | 266 | 217.06 |

| ISA Transactions | 1 | Q1 | 6.3 | Q1 | 1.57 | 83 | 205.24 |

| Complex & Intelligent Systems | 1 | Q2 | 5.0 | Q1 | 1.32 | 66 | 108.90 |

| International Journal of Energy Research | 1 | Q1 | 4.3 | Q1 | 0.83 | 89 | 79.41 |

| Results in Engineering | 1 | Q1 | 6.0 | Q1 | 0.79 | 54 | 63.99 |

| Soft Computing | 1 | Q2 | 3.1 | Q2 | 0.81 | 90 | 56.50 |

| International Journal of Sustainable Transportation | 1 | Q2 | 3.1 | Q1 | 1.22 | 47 | 44.44 |

| International journal of green energy | 2 | Q3 | 3.1 | Q2 | 0.72 | 39 | 43.52 |

| World Electric Vehicle Journal | 2 | Q2 | 2.6 | Q2 | 0.57 | 40 | 29.64 |

| Energy & Environment | 1 | Q2 | 4.0 | Q2 | 0.64 | 40 | 25.60 |

| IET Intelligent Transport Systems | 1 | Q2 | 2.3 | Q1 | 0.78 | 44 | 19.73 |

| Transportation Research Record | 1 | Q3 | 1.6 | Q2 | 0.54 | 56 | 12.10 |

| Promet - Traffic & Transportation | 1 | Q4 | 0.8 | Q3 | 0.3 | 17 | 1.02 |

| International Journal of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles | 1 | Q4 | 0.4 | Q3 | 0.26 | 10 | 0.26 |

| IAES International Journal of Artificial Intelligence (IJ-AI) | 1 | - | - | Q3 | 0.37 | 29 | 0.00 |

| Procedia Computer Science | 1 | - | - | - | 0.51 | 113 | 0.00 |

| IFAC-PapersOnLine | 1 | - | - | - | 0.37 | 56 | 0.00 |

| 2014 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, ICCAD | 1 | - | - | - | - | 41 | 0.00 |

| Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing | 1 | - | - | - | - | 40 | 0.00 |

| Proceedings - 2016 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence, CSCI 2016 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 22 | 0.00 |

| Proceedings - 2022 IEEE 4th Global Power, Energy and Communication Conference, GPECOM 2022 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 18 | 0.00 |

| IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Proceedings, ITSC | 2 | - | - | - | - | 16 | 0.00 |

| International Conference on Vehicle Technology and Intelligent Transport Systems (VEHITS) | 1 | - | - | - | - | 16 | 0.00 |

| 2019 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference, ITEC-India 2019 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 13 | 0.00 |

| 2021 21st International Symposium on Power Electronics, Ee 2021 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 10 | 0.00 |

| Proceedings - 2018 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2018 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe, EEEIC / I and CPS Europe | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.00 |

| SSTD '21: Proceedings of the 17th International Symposium on Spatial and Temporal Databases | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.00 |

| Medicon Engineering Themes | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.00 |

| 28th International Electric Vehicle Symposium and Exhibition 2015, EVS 2015 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.00 |

| Publisher | Percentage of articles |

|---|---|

| Elsevier | 30.9 |

| MDPI | 21.8 |

| IEEE | 18.2 |

| Taylor & Francis | 5.5 |

| Springer | 5.5 |

| Sage | 3.6 |

| Otras | 14.5 |

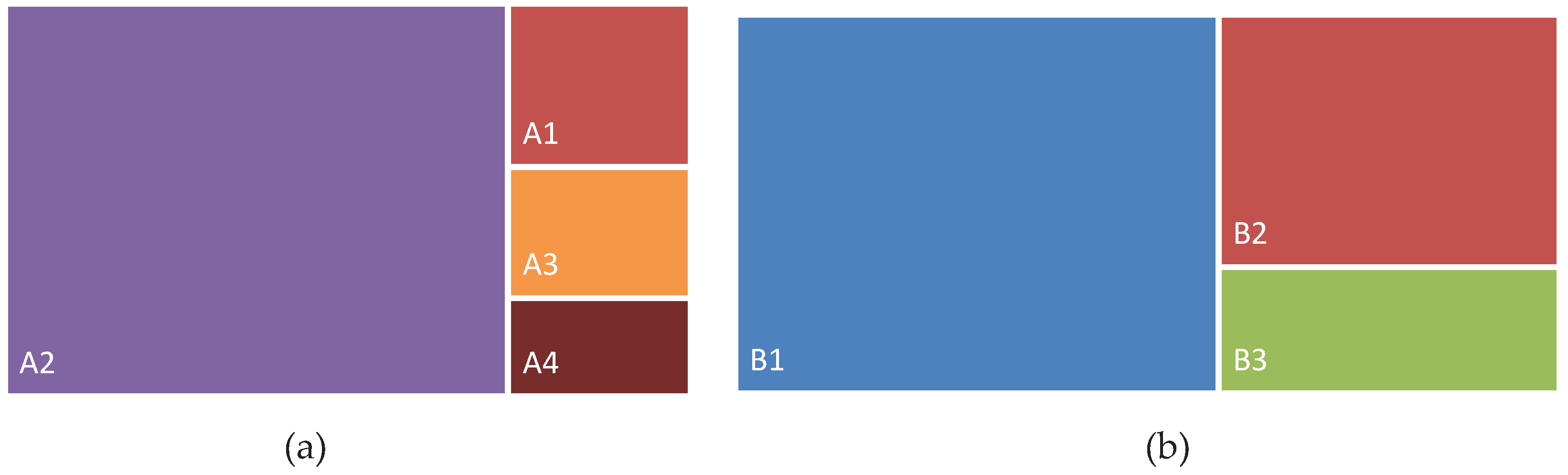

| Category 1. Methodologies for predicting BEV energy consumption | Number of articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Rule-based models | A1 | Simulación | [25,32,34,36,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91] | 15 |

| A2 | Digital Twin (DT) | [92,93] | 2 | |

| B: Data-driven models | B1 | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | [33] | 1 |

| B2 | Polynomial Regression (PR) | [78,94,95,96] | 4 | |

| B3 | Exponential Regression (ER) | [78] | 1 | |

| B4 | Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | [13,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102] | 9 | |

| B5 | Quantile Regression Neural Networks (QRNN) | [103] | 1 | |

| B6 | k-Nearest Neighbours (KNN) | [39,104,105] | 3 | |

| B7 | Mixture of Experts (MoE) | [98] | 1 | |

| B8 | Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | [39,96,100,101,106,107,108,109,110,111] | 10 | |

| B9 | Support Vector Regression (SVR) | [13,39,106,112] | 4 | |

| B10 | Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | [13,39,100,106,113,114,115] | 7 | |

| B11 | Decision Tree (DT) | [99,105] | 2 | |

| B12 | Ensemble Stacked Generalisation (ESG) | [105] | 1 | |

| B13 | Random Forest (RF) | [13,101,105] | 3 | |

| B14 | Transfer Learning (TL) | [107] | 1 | |

| B15 | Multifunctional Neural Networks (MNN) | [116] | 1 | |

| B16 | Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) | [39,100,114] | 3 | |

| B17 | Deep Neural Networks (DNN) | [39,117] | 2 | |

| B18 | Quantile Regression (QR) | [103] | 1 | |

| B19 | Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM) | [111,117] | 2 | |

| B20 | CNN – Bagged Decision Tree (BDT) | [118,119] | 2 | |

| B21 | Quantile Extreme Gradient Boosted Regression (QEGBR) | [103] | 1 | |

| B22 | Quantile Regression Forests (QRF) | [103] | 1 | |

| B23 | Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) | [101,114] | 2 | |

| B24 | LSTM + Transformer | [111] | 1 | |

| B25 | Probabilistic Neural Networks (PNN) | [102] | 1 | |

| C: Hybrids | A-B2 | [79,120] | 2 | |

| A-B3 | [121] | 1 | ||

| A-B8 | [44,122] | 2 | ||

| A-C1 | Linear Mixed Models (LMM) | [122] | 1 | |

| A-B4 | [123] | 1 | ||

| A-C2 | MLR (Fitting with the Recursive Least Squares – RLS – algorithm) + MLP | [124] | 1 | |

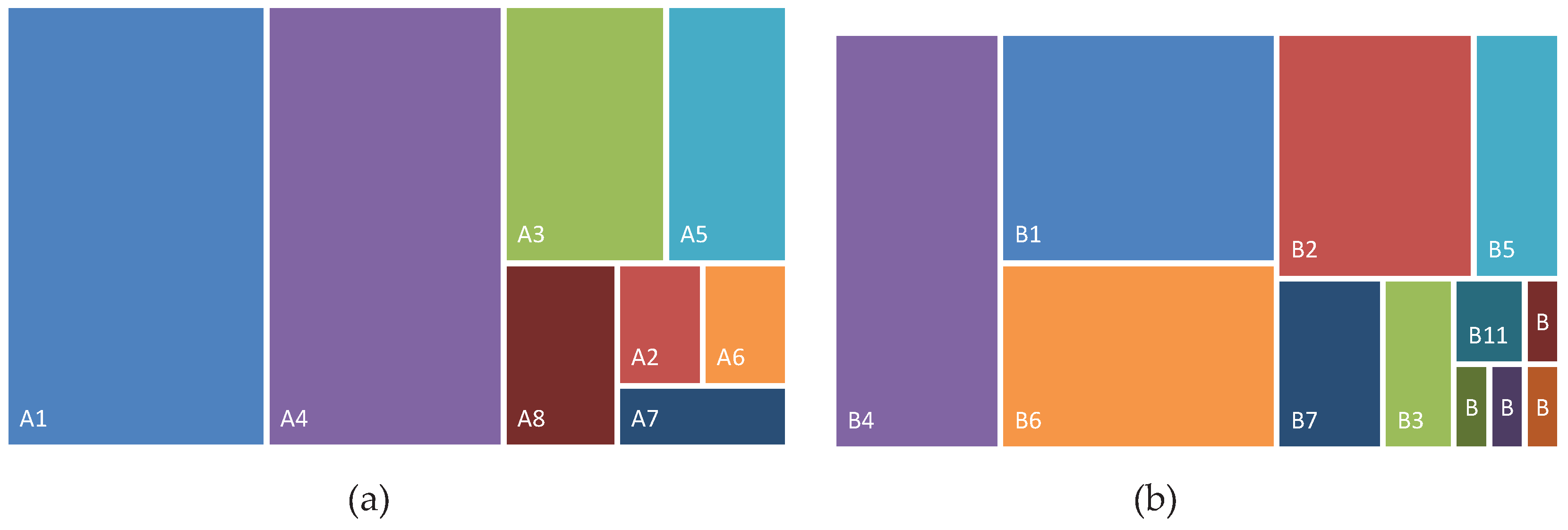

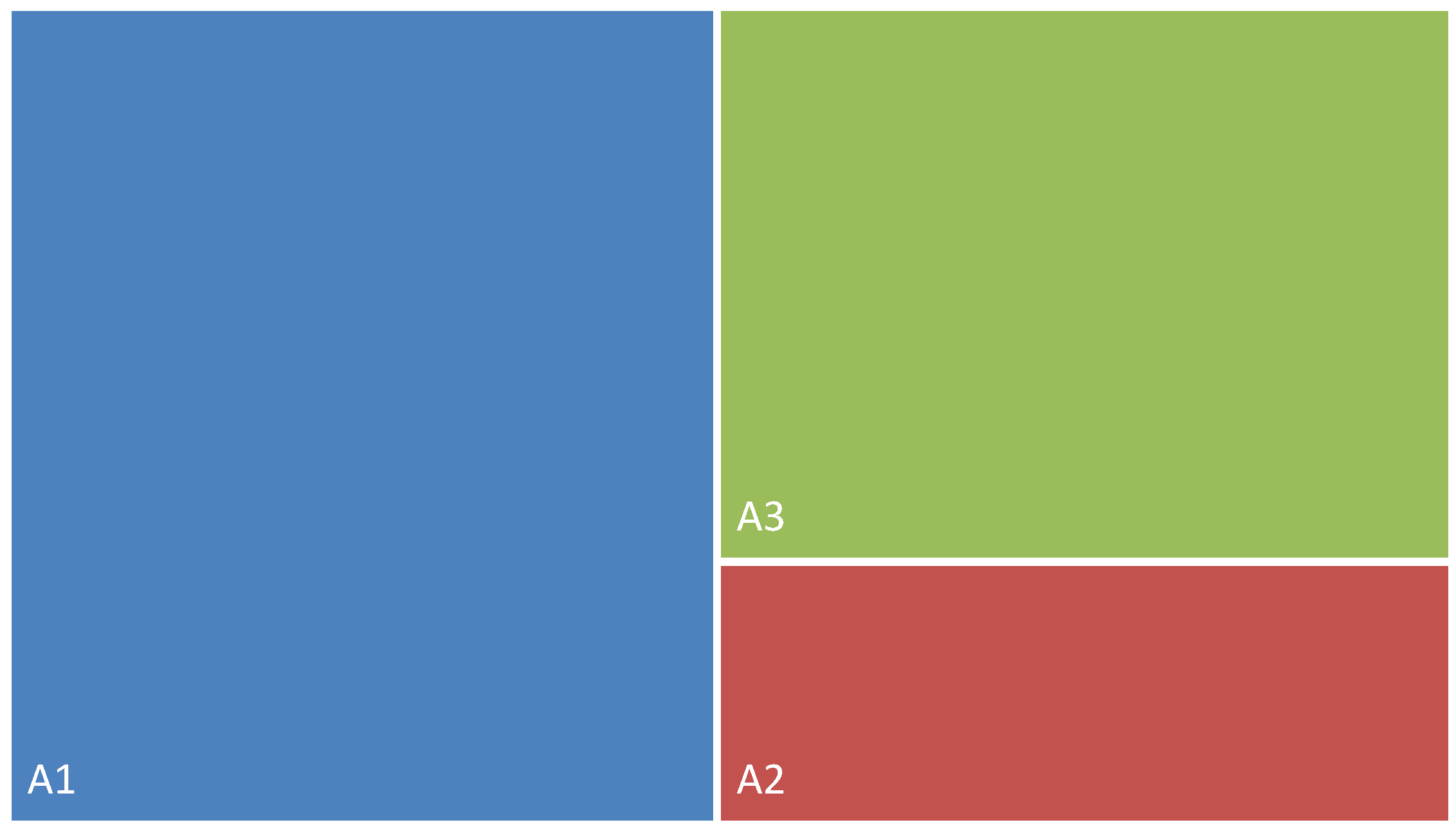

| Categories 2 and 3. Computational tools and evaluation metrics used for predicting BEV energy consumption | Number of articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Computational tools | A1 | Matlab | [25,34,81,82,83,84,86,88,119,121,124] | 11 |

| A2 | FASTSim | [33] | 1 | |

| A3 | SPSS | [41,78,110,120] | 4 | |

| A4 | Python | [39,94,99,101,102,105,106,112,117,119] | 10 | |

| A5 | SUMO | [93,104,114] | 3 | |

| A6 | Cruise | [92] | 1 | |

| A7 | GT-Suite | [93] | 1 | |

| A8 | R | [44,108] | 2 | |

| B: Evaluation metrics | B1 | RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) | [13,33,39,98,100,102,103,104,105,106,109,111,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,121,123] | 21 |

| B2 | MAE (Mean Absolute Error) | [33,39,85,93,100,103,105,106,109,111,115,116,117,118,119,123] | 16 | |

| B3 | r (Pearson Correlation Coefficient) | [25,33,91,119] | 4 | |

| B4 | MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error) | [13,25,34,36,78,79,82,84,87,88,89,90,102,105,111,112,113,114,115,117,118,120,124] | 23 | |

| B5 | Relative error | [32,41,92,93,97,107,108] | 7 | |

| B6 | R² (Coefficient of Determination) | [13,25,39,41,96,99,100,101,105,106,108,109,110,115,120,121,122] | 17 | |

| B7 | MSE (Mean Squared Error) | [39,101,105,116,117,122] | 6 | |

| B8 | Variable correlation matrix | [105] | 1 | |

| B9 | MASE (Mean Absolute Scaled Error) | [44] | 1 | |

| B10 | AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) | [122] | 1 | |

| B11 | SMAPE (Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error) | [95,96] | 2 | |

| B12 | EVS (Explained Variance Score) | [117] | 1 | |

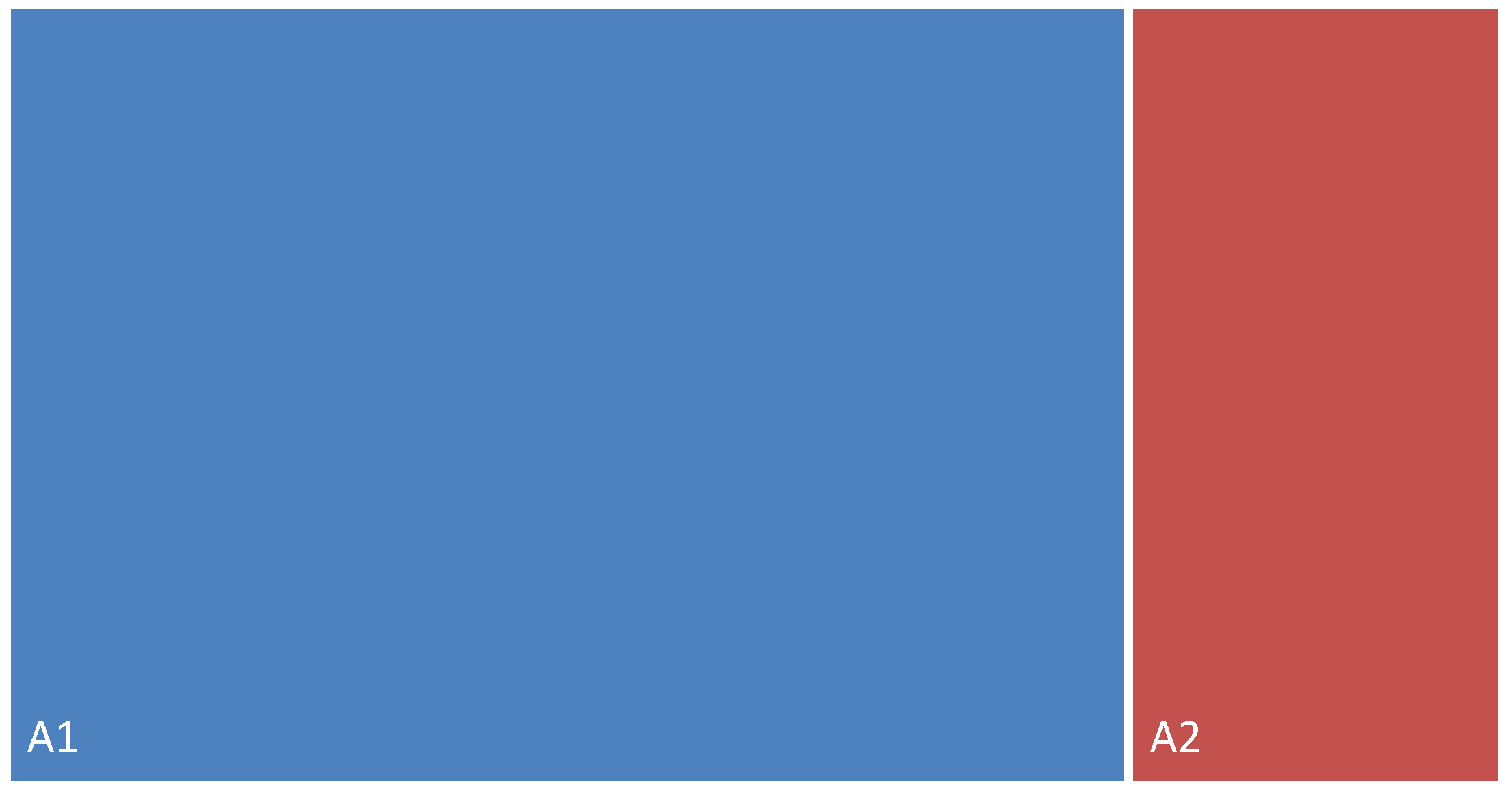

| A1 Vehicle-intrinsic | A2 Environment | A3 Operational | A4 Driving style | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1.1 Related to BEV dynamics | A1.2 Related to BEV components | A2.1 Ambient conditions | A2.2 Road characteristics | ||

| Rolling resistance coefficient Aerodynamic drag coefficient Speed Acceleration Frontal área Vehicle mass Dynamic radius Longitudinal slip ratio Wheel angular speed |

Battery capacity Electric motor efficiency Transmission efficiency Inverter efficiency SoC Range Regenerative braking factor Regeneration power HVAC system power Battery current, voltage, resistance, and power Electric motor voltage and current Accelerator pedal opening percentage Battery temperatura Cabin temperatura Auxiliary loads power: infotainment RPM Recharging time Gear ratio Mass factor Battery specific heat capacity Battery mass Battery emissivity |

Temperature Wind speed Wind direction Precipitation Humidity Air density Visibility |

Road gradient Elevation Road length Road curvature Road night-time lighting Number of route turns Pavement type (asphalt, concrete, dirt, etc.) |

Traffic index Travelled distance (odometer) Driving time (peak/off-peak hours, day or night) Travel time Position (geographical coordinates) Speed limit Traffic signalisation Number of stops Day of the week Road type (urban, highway, primary, residential, or secondary) |

Speed Acceleration Traction torque Braking torque PKE NKE |

| Categories 2 and 3. Sampling frequency and analysis period of variables used for predicting BEV energy consumption | Number of articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Sampling frequency | A1 | < 1 s | [33,97,115,118,119] | 5 |

| A2 | 1 s | [13,25,32,34,36,41,44,78,79,81,82,83,84,85,86,90,91,92,93,95,96,101,102,103,108,109,112,113,114,120,121,123,124] | 33 | |

| A3 | > 1 s y ≤ 1 min | [100,105,111,122] | 4 | |

| A4 | > 1 min | [94,99,104] | 3 | |

| B: Analysis period | B1 | < 1 año | [13,25,36,39,41,44,84,85,91,95,96,101,110,118,120,123,124] | 17 |

| B2 | 1 año | [94,100,105,111,113,115,117,122] | 8 | |

| B3 | > 1 año | [88,103,108,109] | 4 | |

| Modelling scales used for predicting BEV energy consumption | Number of articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Modelling scale | A1 | Microscopic | [25,32,33,34,44,78,79,81,82,83,84,85,86,88,89,91,92,93,97,101,111,118,119,120,121,123,124] | 27 |

| A2 | Mesoscopic | [36,39,41,95,96,98,102,107,114] | 9 | |

| A3 | Macroscopic | [13,87,90,94,99,100,103,104,105,106,108,109,110,112,113,115,116,117,122] | 19 | |

| Data source of the models used for predicting BEV energy consumption | Number of articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Data source | A1 | Real-world data | [13,25,34,36,39,41,44,79,84,85,87,88,90,91,92,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,120,121,122,123,124] | 45 |

| A2 | Simulated data | [32,33,36,78,81,82,83,86,89,91,93,96,101,119,121] | 15 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).