1. Introduction

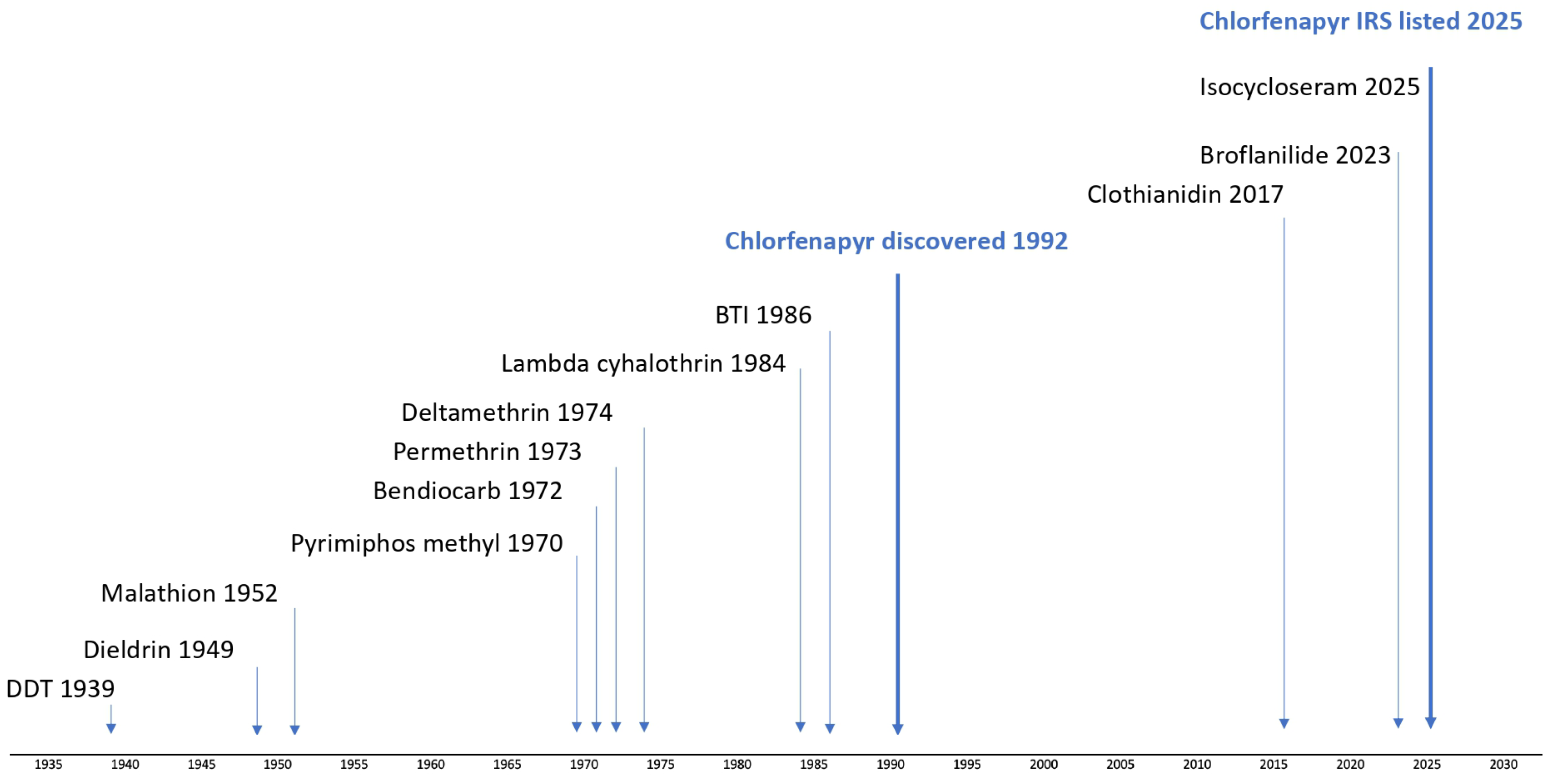

Indoor residual spray (IRS) has historically relied on neurotoxic, fast-acting insecticides: Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) in the 1940s, dieldrin in the 1950s, organophosphates in the 1960s, pyrethroids in the 1970s and carbamates in the 2000s (

Figure 1).

Consequently, IRS testing guidelines were designed around forced contact bioassays with short post-exposure observation periods [

1]. These methods did not capture the efficacy of insecticides with delayed modes of action. Chlorfenapyr, for example, showed little effect in standard cone tests but killed free-flying mosquitoes in experimental hut trials [

2], with higher mortality observed over longer holding times [

3,

4,

5]. This highlighted the need for additional bioassays to evaluate slow-acting insecticides or non- neurotoxic insecticide - a need that remains critical for future product development.

For Sylando

® 240SC (chlorfenapyr), standard IRS bioassays underestimated efficacy because they limit mosquito metabolism through restricted movement, daytime testing, and short post-exposure observation periods. Bioactivation of chlorfenapyr to its toxic metabolite is maximal when mosquito metabolism is elevated [

6]. In

Anopheles gambiae, approximately 20% of its transcriptome (2800 of known genes) is regulated by circadian rhythms [

7]. As a primarily nocturnal species,

Anopheles exhibit peak flight metabolism at dusk and night [

7,

8], coinciding with host-seeking activity [

9], and flight itself is supported by extremely high metabolic rates [

10,

11]. Experimental hut bioassays are generally regarded as the most representative proxy for IRS and insecticide treated net (ITN) performance against malaria vectors [

12,

13] as they allow free flying mosquitoes interact naturally with insecticide residues in the presence of a blood-host [

14]. Notably, results from experimental hut trials [

12] reflect the demonstrated clinical impact [

15,

16] of chlorfenapyr treated ITNs.

A standardized assay using defined numbers of laboratory reared mosquitoes of several species was still needed to verify the efficacy of IRS under controlled conditions. The Ifakara Ambient Chamber Test (I-ACT), originally developed to evaluate operationally aged ITNs [

17], also demonstrated the potential of chlorfenapyr ITNs for malaria control [

18]. Establishing a controlled IRS testing platform that allows overnight mosquito free flight in the presence of a blood-host, while incorporating delayed mortality measurements, offers the opportunity to reduce variability, increase statistical power and cost-effectively generate evidence comparable to hut trials. This study therefore aimed to assess whether Sylando

® 240SC was non-inferior to SumiShield

® 50WG when tested against malaria and dengue vectors in the I-ACT.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

A longitudinal semi-field evaluation of the entomological efficacy of Sylando® 240SC (chlorfenapyr) compared with SumiShield® 50WG was conducted over 12 months on mud, wood and concrete surfaces representative of those used in Tanzanian houses. Spraying took place in August 2022 and bioefficacy evaluations were performed monthly until September 2023.

The experiments were conducted in a semi-field tunnel called Ifakara ambient chamber test (I-ACT) [

17]. The I-ACT allows free-flying mosquitoes to interact with treated surfaces under controlled conditions. The primary endpoint was mosquito mortality at 72 hours as this is the standard holding time used for slow acting insecticides [

19]. Mortality was also measured at 24-hour intervals for up to 1 week (168 hours) post exposure as a secondary end-point. Blood feeding success was recorded, although IRS generally functions by killing mosquitoes that are resting after feeding [

20,

21]. The primary analysis is based on the three Afrotropical vectors for 12 months of evaluation following the predefined analysis plan.

Study Area

The study was conducted at the Kingani site of the Ifakara Health Institute, Bagamoyo (70km North of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; 6° 8’ S and 30° 37’ E). The district receives 800mm – 1000mm of rainfall annually, with mean temperatures of 24ºC-29ºC, and mean relative humidity at 73% due to its coastal location. Insectaries and insecticide testing laboratories are located on site.

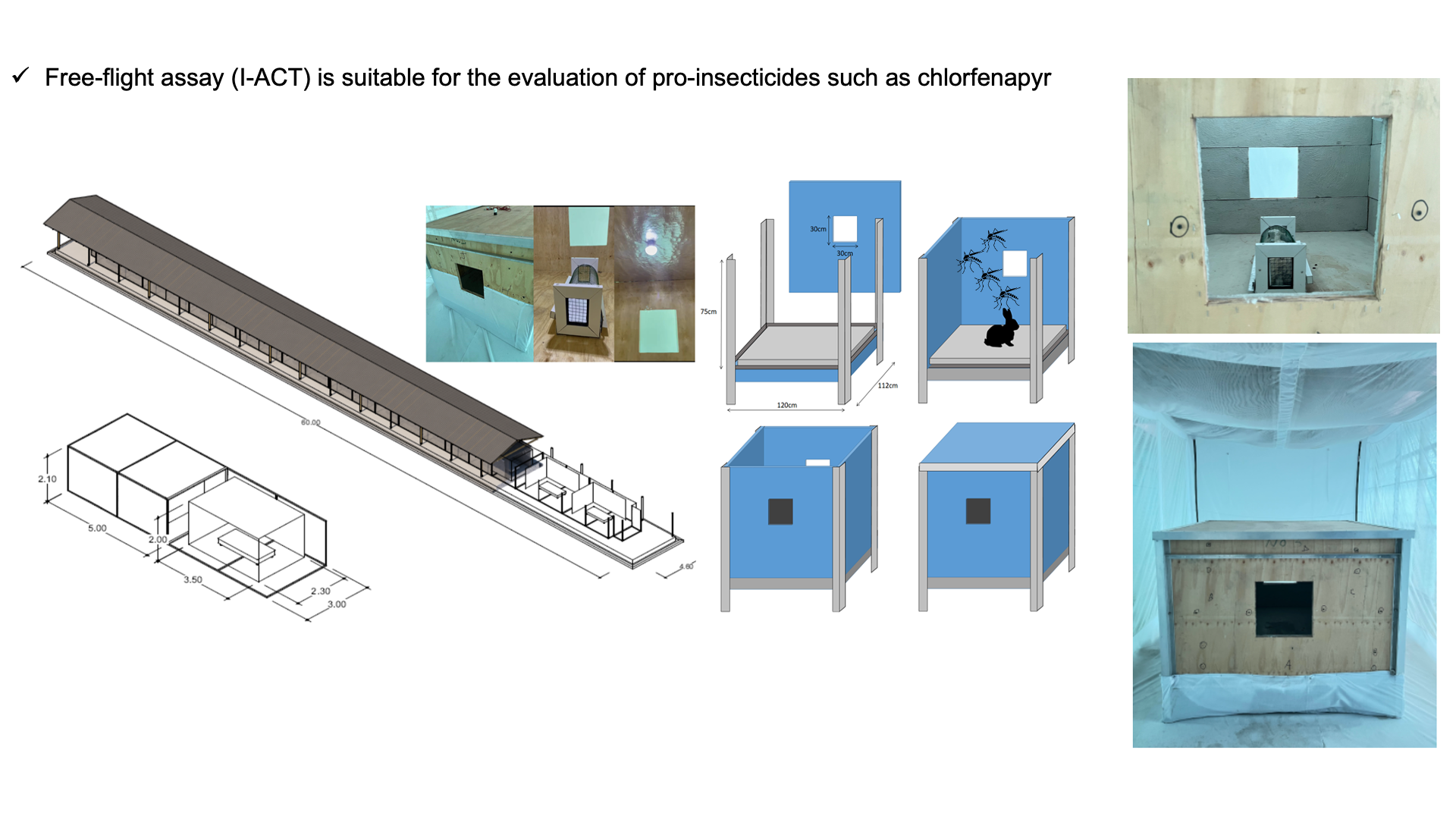

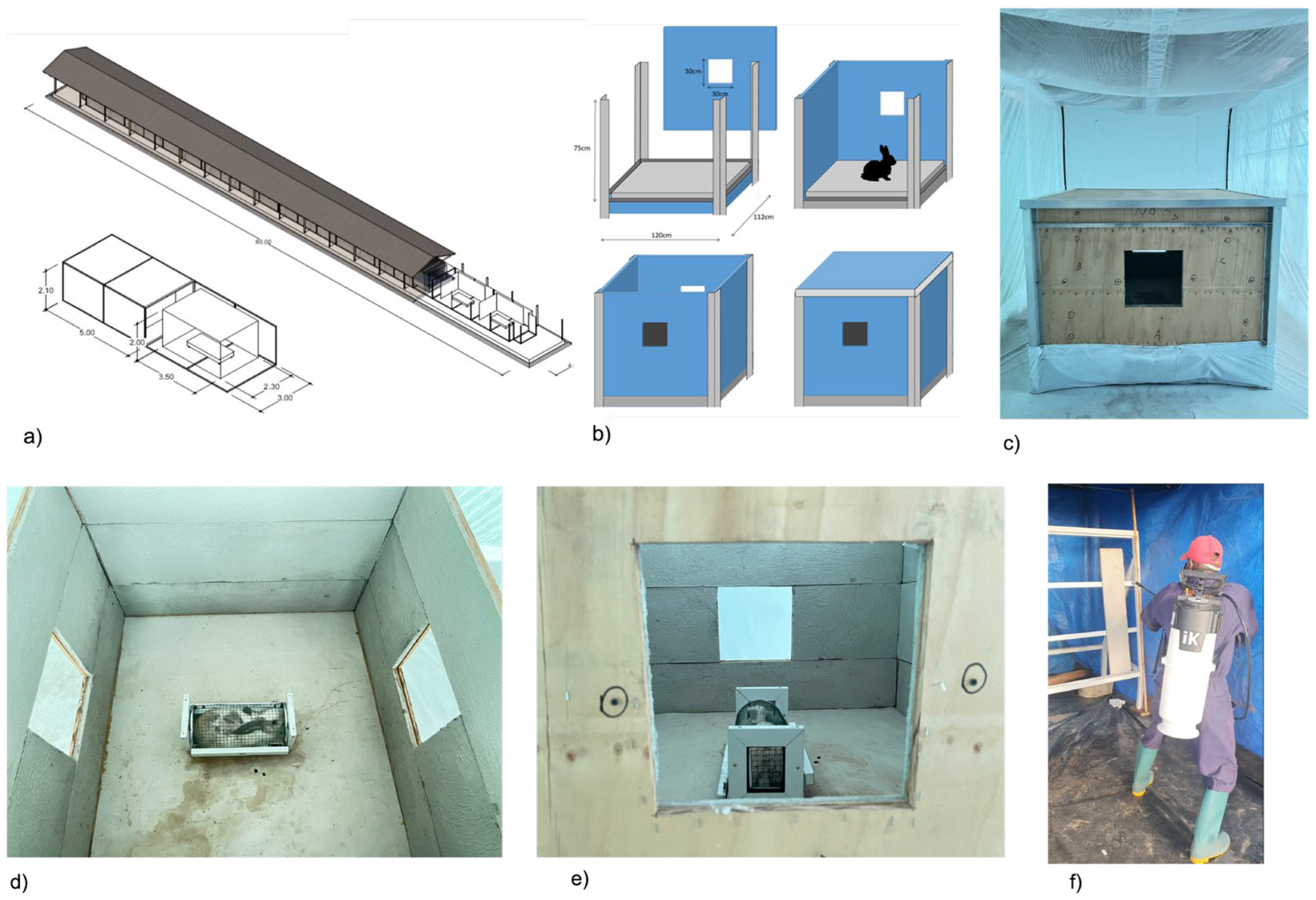

Ifakara Ambient Chamber Test for IRS Evaluation

The I-ACT has previously been used to evaluate IRS [

22]. Twelve experimental compartments were fitted with mini-experimental huts (MEH,

Figure 2a). Each MEH measures 120x112x75cm have square two openings (30x30cm) allowing mosquitoes entry and exit (

Figure 2b & 2c). The surface area to volume ratio is 3.3 approximately double that of East African (1.3) West African (1.3) Ifakara (1.2) and Rapley (1.5) huts, maximising probability of mosquito contact with a treated surface. Panels of each MEH are designed to fit standard track sprayers [

23].

Insecticides and Their Application

Sylando

® 240SC (chlorfenapyr, BASF) was applied at 250 mg/m

2. SumiShield

® 50WG (clothianidin 50% w/w, Sumitomo) was applied at 300 mg/m

2. Both products are WHO PQ-listed [

23]. Negative controls (water) were included.

IRS products were mixed per manufacturer instructions and applied using IK Vector Control Super 7.5.1 backpack sprayers (Goizper, Spain) with a 1.5-bar control flow valve (CFV; discharge rate 30 ml/min). Separate sprayers were used for each treatment to avoid cross-contamination. Sprayers were calibrated, and gravimetric checks were performed by weighing depressurized tanks before and after spraying.

Substrate Preparation and Spraying Procedures

Substrate blocks (1–1.5 cm thick) of wood, concrete and mud were prepared. Plywood was cut into blocks for wood panels. Concrete blocks were made from 3333 g cement (Twiga Plus Portland Concrete), 1667 g sieved sand and 1 L distilled water. Mud blocks were prepared from 1600 g sieved soil, 2400 g sand and 1 L distilled water. Sand and mud were collected from the Wami River at the Ruvu bridge. Each mixture was stirred in separate plastic bowls for five minutes to ensure uniformity, applied to the rectangular surfaces using a trowel, and left to dry. Blocks were dried (mud: 1 week; concrete: 1 month after curing in distilled water for 3 days). Environmental conditions during curing were median 29.7 °C (Interquartile Range (IQR) 28.8–33.1) and 81.6% Relative Humidity (RH) (IQR 75.5–87.5). pH values were within the acceptable range: 7 for wood and mud, 9–10 for concrete.

Panels were sprayed outside the chambers and fitted to huts the same day. Protected spray tents prevented drift (

Figure 2d). Application was standardised with metronomes to regulate spray speed and 45cm lances to ensure correct distance. Whatman

® No 1. filter papers were attached to panels for spray quality monitoring. Four substrate samples and eight filter papers were sent to CRA-W, Belgium, for chemical verification.

Mosquitoes

Colony maintenance:

Anopheles larvae were fed on Tetramin

® fish food and

Aedes larvae on cat biscuits; adults received blood meals (cow blood from a membrane feeder) 3 to 6 days after emergence and 10% sugar solution

ad libitum. Temperature and humidity within the insectary are maintained between 27ºC ± 2 ºC and 70% ± 25% following MR4 guidelines [

24].

The following strains were used:

- 1)

Anopheles arabiensis (Kingani), resistant to pyrethroids with mixed function oxidases

- 2)

An. funestus (Fumoz), resistant to pyrethroids with mixed function oxidases

- 3)

An. gambiae s.s. (Ifakara), fully pyrethroid-susceptible

- 4)

Culex quinquefasciatus (Bagamoyo), resistant to pyrethroids with mixed function oxidases

- 5)

Aedes aegypti (Bagamoyo strain), fully pyrethroid-susceptible

- 6)

Ae. aegypti (Kinondoni strain), resistant to pyrethroids and organophosphates

Resistance Profile: The resistance profiles of the five laboratory strains were confirmed at the time of testing (

Table S1) using both WHO tube assays [

25] and gene expression analysis associated with metabolic insecticide resistance in

An. arabiensis,

An. gambiae s.s., and

An. funestus. The presence of target-site mutations was assessed using qPCR [

26]. To investigate detoxification mechanisms, triplex RT-qPCR assays were conducted to evaluate the expression of seven cytochrome P450 detoxification genes (CYP6P3, CYP6M2, CYP9K1, CYP4G16, CYP6P4, CYP6P1, and CYP6Z1) and glutathione S-transferase epsilon 2 (GSTe2). Gene expression levels were compared against the ribosomal protein S7 (RPS7) reference gene. Following RNA extraction, RT-qPCR was performed to quantify gene expression. The detoxification genes exhibited low Ct values (<20) in the resistant

An. funestus and

An. arabiensis strains compared to the susceptible

An. gambiae Ifakara strain. Ct values for the

RPS7 reference gene remained consistent across all samples, supporting the conclusion that the lower Ct values reflect a specific upregulation of detoxification gene transcripts. Relative expression patterns of all genes were analyzed using REST 2009 software v1.0 (Qiagen).

Assay Conduct

A restrained rabbit served as bait in each MEH between 18.00 hrs to 09.00 hrs, covering host-seeking periods of

Anopheles and

Culex and early morning activity of

Ae. aegypti. For each replicate, 20 nulliparous 3-5-day old, sugar-fed, laboratory reared mosquitoes of each strain were aspirated into cups by laboratory staff released into each chamber outside the MEH by removing the net on the holding cups (

Figure 2e &

Figure 2f). Morphologically identical

Anopheles were dusted with fluorescent powder (Sigma Aldridge

®, Burlington, MA, USA) to distinguish them.

After the allotted experimental time, all mosquitoes within each of the compartments were removed by prokopack aspirators and syphons (with HEPA filter). Surviving mosquitoes were placed in paper cups (fed and unfed are placed in different cups to allow measurement of pre- and post-prandial mortality if desired), provided with 10% sucrose solution, and mortality was recorded at 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144 and 168 hours.

Environmental conditions inside the I-ACT during the experiment were median temperature 26.2°C ( [IQR]: 25.1, 29.8) and 81.5% median RH (IQR: 77.9, 85.8). The holding room was maintained at median temperature of 26.2°C (IQR: 25.6, 27.2) and a median RH of 77.3% (IQR: 74.3, 85.2) at the time of the experiment (

Figure S1).

Measures to Reduce Bias

Treatment allocation was randomised and coded with four-digit identifiers. Investigators recording outcomes were blinded until after database lock. Two huts per treatment arm improved precision. Huts were not rotated between chambers to preserve sprayed surfaces, but chambers were structurally identical and any residual variance was adjusted in analysis.

Sample Size

Sample size was estimated using the precision of the confidence interval of the mean, assuming 80% mortality, 90% power and 99% confidence to detect a 99% confidence interval of 5% of the mean. Each replicate consisted of 20 mosquitoes per strain. With two huts per substrate per treatment arm and five nights per hut, 200 mosquitoes per strain per substrate per month were tested for Sylando® 240SC. For positive and negative controls, 100 mosquitoes per strain per substrate per month were tested. In month 7, replication increased to eight nights to ensure adequate precision.

Statistical Analysis

Data were double-entered in excel and exported into STATA 17 software (StataCorp LLC, College Station TX, USA) for further cleaning and analysis. Mortality was summarised as arithmetic mean percentages with 95% CIs at 72 h and 168 h holding period for each treatment and species presented.

Multivariable mixed-effect logistic regression with binomial error and log link function was used to compare Sylando

® 240SC to SumiShield

® 50WG for each species. Treatment, chamber and day were fixed effects. For pooled analyses, substrate type was included as a fixed effect and for analyses of multiple strains combined, mosquito strain was also included as a fixed effect. The non-inferiority margin was 7%. Analyses were interpreted following CONSORT guidance [

27] with results reported as odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs over the 12-month period.

3. Results

3.1. Study Quality Check

Chemical analysis results of filter paper were within the target dose (

Table 1).

Over the entire 12 months of evaluation, mosquito mortality at 168 hours post spray in negative control huts for all strains and substrates was <15%, whilst blood feeding success was >88%.

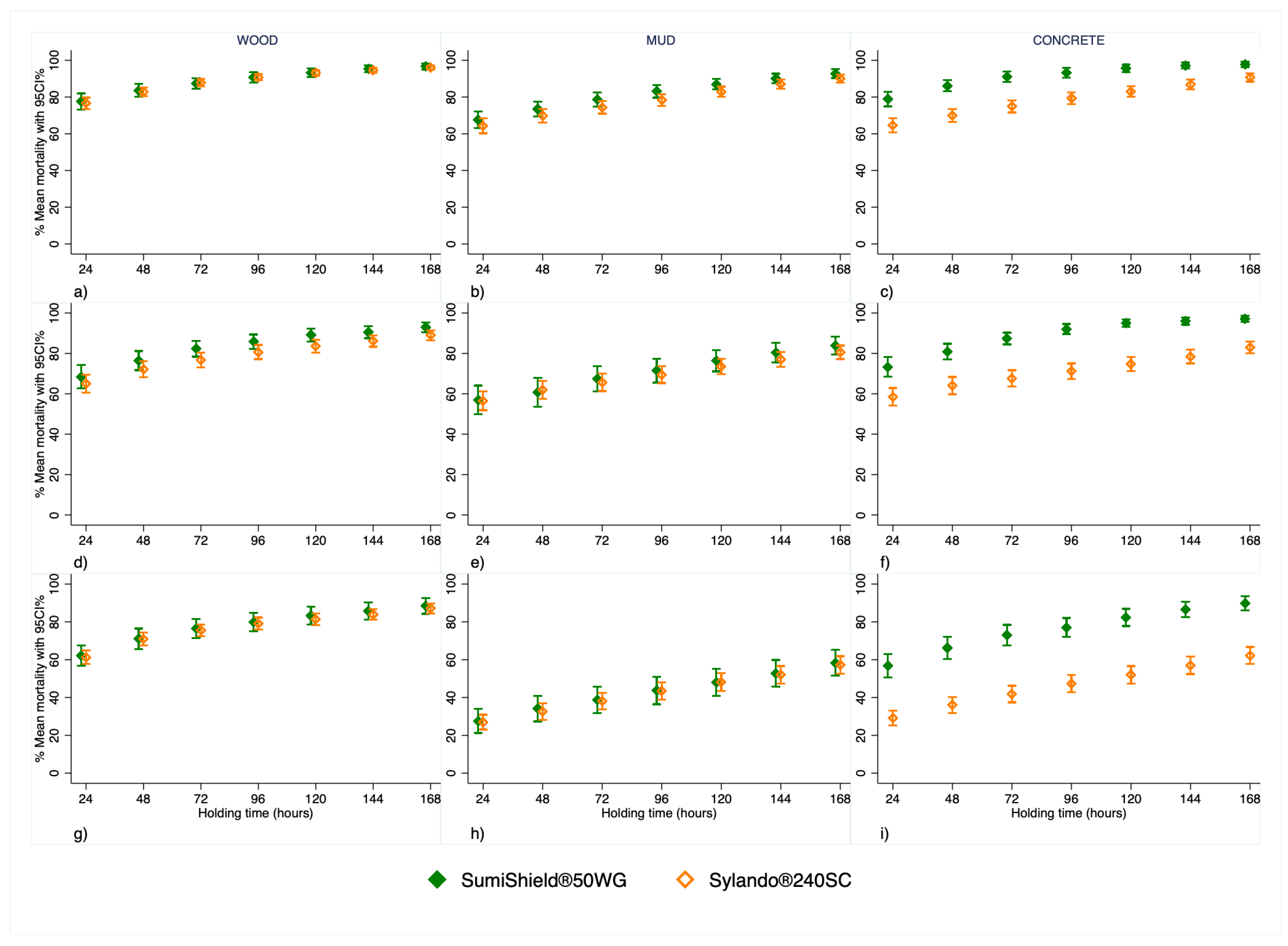

3.2. Overall Mosquitoes’ Mortality

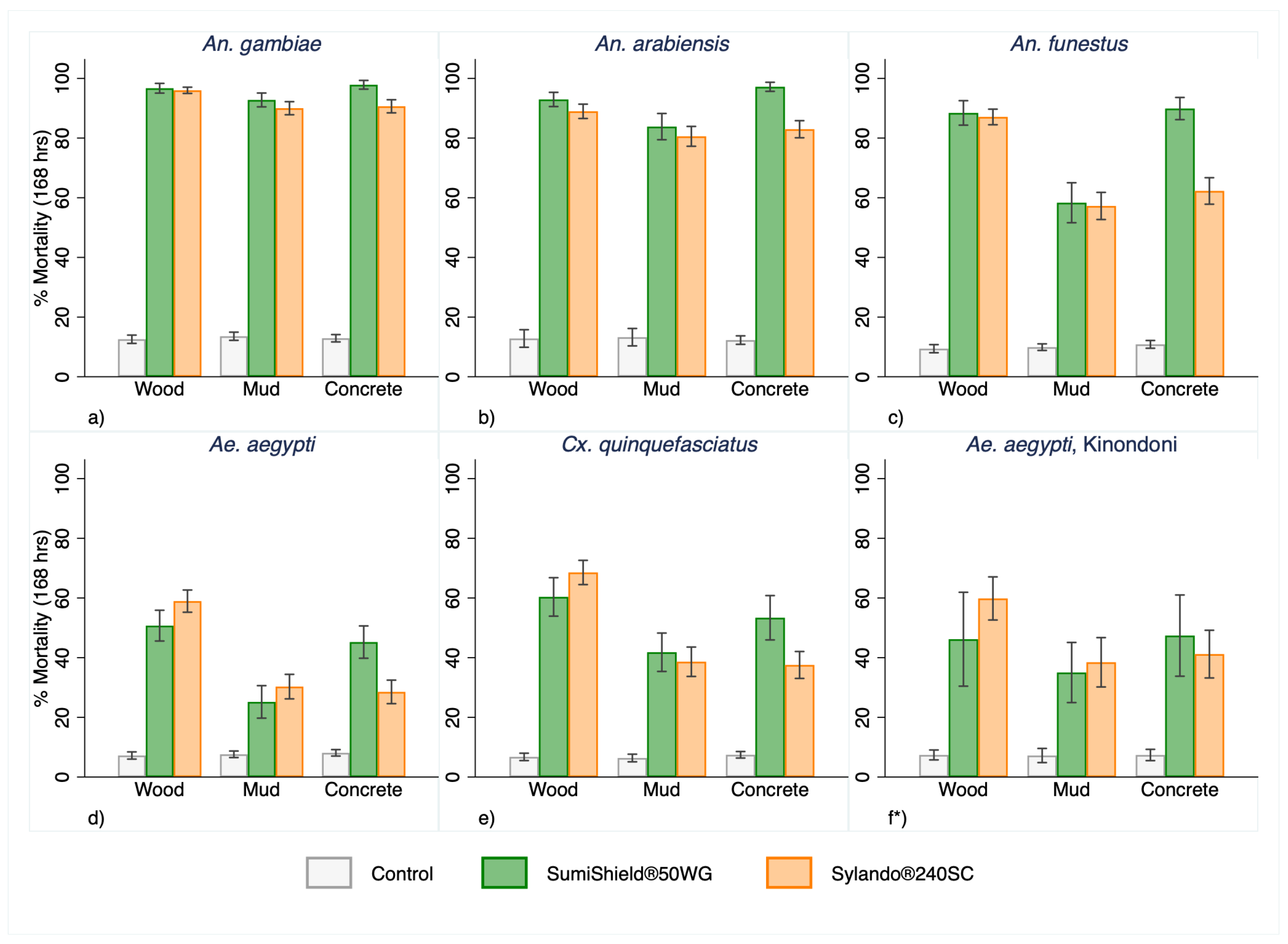

Both products exhibited comparable performance, with mortality increasing over longer holding times across all substrates for each malaria vector species (

Figure 3).

On wood and mud mortality was almost identical between products, whereas SumiShield

® 50WG induced higher mortality on concrete (

Figure 3 & Figure 4).

Malaria vectors consistently showed greater mortality than non-malaria vectors in both IRS treatment arms (

Figure 4). After 168 hours, mortality exceeded 80% for pyrethroid-susceptible

An. gambiae and pyrethroid-resistant

An. arabiensis on each substrate, and surpassed 60% for pyrethroid-resistant

An. funestus (

Figure 4). Full mortality data for each strain over the 12-month evaluation period, disaggregated by product and substrate, are provided in the supplementary materials (

Figure S2 and S3).

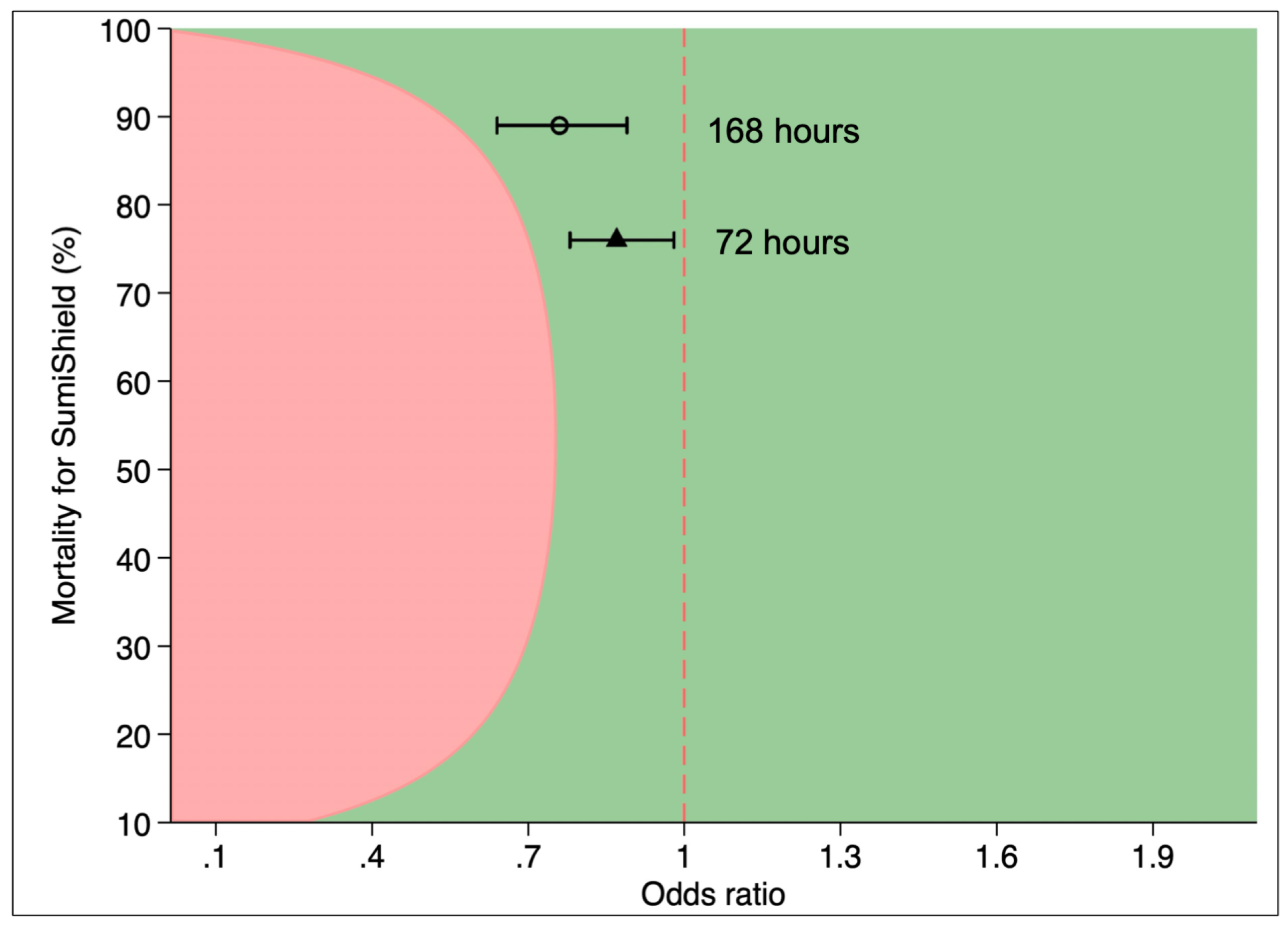

3.3. Non-Inferiority Testing of Sylando® 240SC and SumiShield® 50WG; Afrotropical Vectors Combined

Across all substrates combined and over the 12-months period, combined mortality at 72 hours

An. gambiae (pyrethroid-susceptible),

An. arabiensis (pyrethroid-resistant) and

An. funestus (pyrethroid-resistant) was 67% for Sylando

® 240SC compared to 76% in SumiShield

® [OR=0.86, 95%CI: 0.77, 0.97]. By 168 hrs mortality increased to 82% with Sylando

® 240SC and 89% with SumiShield

® 50WG [OR=0.74, 95%CI: 0.63, 0.87]. Using a 7% non-inferiority margin, Sylando

® 240SC was demonstrated to be non-inferior to SumiShield

® 50WG at both 72- and 168-hour holding times (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

Performance of Sylando® 240SC and the Case of Chlorfenapyr

The Ifakara Ambient Chamber Test (I-ACT) clearly demonstrated that when mosquitoes are given sufficient time for bioactivation—specifically the conversion of chlorfenapyr to its toxic metabolite tralopyril—mortality is significantly increased. This was also observed in earlier targeted IRS (TIRS) studies with

Aedes aegypti in Mérida, Mexico, where delayed intoxication was recorded during extended observation [

28].

The delayed metabolic action of chlorfenapyr is challenging. Apparent “resistance” could be misattributed [

29] if bioactivation is not complete due to low temperature, incorrect photoperiod or lack of mosquito movement [

30]. In addition, use of solvents that don’t interact well with chlorfenapyr can lower observed mortality [

29]. Mechanistically, chlorfenapyr is a pro-insecticide functioning as a protonophore. It accepts protons and facilitates their transport across the inner mitochondrial membrane, uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation. This process dissipates energy as heat, depletes Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and causes paralysis and death [

31]. While altered expression of metabolic genes—particularly cytochrome P450s such as CYP6P1, CYP6P3, CYP6Z1 and CYP4G16—can affect pyrethroid susceptibility, these do not necessarily reduce chlorfenapyr activity and may even promote pro-insecticidal conversion [

32]. However, detoxification via glutathione S-transferases (GSTs), notably GSTE2, could plausibly reduce susceptibility by conjugating halogenated compounds [

33,

34]. This underscores the need for nuanced interpretation of susceptibility changes rather than reliance on neurotoxic resistance markers.

Currently, WHO PQT/VCP (World Health Organization Prequalification Team – Vector Control Products) lists several IRS insecticides including alpha-cypermethrin, bifenthrin, bendiocarb, clothianidin, deltamethrin, etofenprox, lambda-cyhalothrin, pirimiphos-methyl, broflanilide, isocycloseram, and chlorfenapyr. However, widespread pyrethroid resistance has led most National Malaria Control Programmes (NMCPs) to abandon older compounds. New chemistries are under exploration but are not yet listed. Given declining donor support, countries must diversify IRS portfolios to sustain efficacy through chemical rotation, especially as chlorfenapyr is widely used in ITNs. The use of Sylando for dengue control should also be considered, especially because of the long-lasting efficacy observed here in addition to positive results from other trials [

28]

Comparative Assessment of Bioassay Methods for Chlorfenapyr

WHO Cone and Cylinder Bioassays

Cone and cylinder assays have long served as WHO standards due to their reproducibility, simplicity, and ability to harmonise results across laboratories and field sites [

25,

35,

36]. However, both were designed for fast-acting neurotoxins and rely on brief, confined exposures. Such conditions are poorly suited to insecticides like chlorfenapyr, which require sustained activity for metabolic activation [

6]. Confinement restricts movement, limiting uptake and underestimating efficacy [

2,

18,

37,

38,

39]. As a result WHO recommends overnight bottle assays for chlorfenapyr resistance monitoring with careful consideration of temperature and solvent [

40].

WHO Tunnel Bioassays

Tunnel assays introduced a more realistic environment, allowing mosquitoes to fly, seek hosts, and contact treated surfaces overnight [

41,

42]. This design improved evaluation of slow-acting chemistries, producing results more predictive of field outcomes than cone or cylinder tests. The tests are conducted overnight when metabolic enzymes that convert chlorfenapyr to tralopyril [

43] are upregulated [

8].

Experimental Hut Trials

Experimental huts, developed in West and East Africa, remain the benchmark for realistic evaluation of vector control interventions [

12,

13]. They enable direct observation of entry, feeding, resting, and mortality under conditions close to household environments. For chlorfenapyr, hut trials confirmed efficacy that laboratory assays had underestimated [

39,

44] and link well to observations from clinical trials.

Ifakara Ambient Chamber Test (I-ACT)

The I-ACT was developed to overcome these limitations by combining ecological realism with experimental control. It allows free-flying, overnight mosquito exposure in a defined volumetric space, under standardised conditions of surface type, application quality, temperature, and humidity. For chlorfenapyr, I-ACT highlighted the importance of extended post-exposure mortality, validated efficacy against resistant strains, and enabled testing of species unavailable for hut trials. Compared with experimental huts, I-ACT offers the option to use a range of vector strains, and releasing high numbers of mosquitoes each night offers greater statistical power, consistency, operational feasibility and cost-effectiveness while still reflecting more natural mosquito behaviour.

Table 2.

Vector Control Testing Methods for slow-acting insecticides like chlorfenapyr.

Table 2.

Vector Control Testing Methods for slow-acting insecticides like chlorfenapyr.

| Method |

Purpose |

Design & Conditions |

Strengths |

Limitations |

Suitability for Chlorfenapyr |

| WHO Cone Bioassay |

Lab-based efficacy testing |

Mosquitoes confined to a treated surface for 3 minutes |

Simple, reproducible, globally standardized |

Restricts movement; unsuitable for metabolic or repellent insecticides |

POOR underestimates efficacy due to limited exposure and bioactivation |

| WHO Cylinder Bioassay |

Resistance monitoring |

Mosquitoes exposed to insecticide-treated paper in a cylinder |

Standardized for resistance detection; easy to implement |

Same confinement issues as cones; surfactant/paper inconsistencies |

POOR

physical and chemical limitations affect chlorfenapyr performance |

| Tunnel Test |

Semi-controlled behavioural assay |

Mosquitoes fly through a tunnel to reach a host; exposure to treated netting |

Simulates host-seeking behaviour; multiple endpoints (mortality, deterrence, feeding) |

Still semi-artificial; limited exposure time |

MODERATE

better than cones, and useful laboratory assay for ITNs, though undeveloped for IRS |

| Ifakara Ambient Chamber Test (I-ACT) |

Controlled, semi-field evaluation |

Large walk-in chamber mimicking a room; mosquitoes fly freely overnight |

High realism, controlled environment, strong statistical power;

multiple endpoints (mortality, feeding) |

Requires infrastructure; relatively new method |

GOOD

Useful for exploring new slow-acting, metabolic non-repellent insecticides like chlorfenapyr |

| Experimental Hut Trials |

Field-realistic efficacy testing |

Free-flying mosquitoes interact with treated surfaces in a hut |

Realistic behaviour with wild mosquitoes; multiple endpoints (mortality, feeding) |

Operational variability; requires skilled personnel and equipment |

EXCELLENT captures effects of metabolic non-repellent insecticides like chlorfenapyr using wild mosquitoes that are highly active during host seeking |

5. Conclusions

Each method has contributed to understanding insecticidal efficacy, but the evaluation of chlorfenapyr highlights their limitations when applied rigidly. Cones and cylinders are useful for benchmarking neurotoxins but underestimate slow-acting pro-insecticide chemistries. Tunnels have not been adapted for testing IRS and attempts in this lab have failed. Huts provide behavioural realism but usually need to be run for prolonged periods, may only have one or two target species and sometimes face operational and reproducibility challenges. I-ACT with MEH bridges these gaps between the laboratory and gold-standard field studies, offering a platform for assessing novel, non-neurotoxic insecticides.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Resistance profile of tested strains, 24 hours mortality results: Q1-2023, Figure S1: The median temperature and humidity inside the IACT and holding room during the experiment over 12 months of evaluation. Figure S2: Percentage mortality at 168 hrs post exposure to substrates sprayed with Sylando®240SC and SumiShield®50WG in I-ACT chamber assay over 12 months of evaluation: a), b) and c) susceptible strain An. gambiae s.s; d), e) and f) pyrethroid resistant An. arabiensis; g), h) and i) pyrethroid resistant funestus; Figure S3: Percentage mortality at 168 hrs post exposure to substrates sprayed with Sylando®240SC and SumiShield®50WG in I-ACT chamber assay over 12 months of evaluation: a), b) and c) Aedes aegypti, fully pyrethroid-susceptible; d), e) and f) pyrethroid resistant Culex quinquefasciatus; g), h) and i) pyrethroid resistant Ae. aegypti

Author Contributions

UAK, SJM, SS and JWS Conceptualization; JJM, ABM, FSCT, DSK, PAK and MP methodology; RRK, JM and JBM software, RRK and JBM validation; SJM and UAK formal analysis; SHN, IM, IK, ABM, FSCT, and DSK investigation; SJM resources, JM, JBM and RRK data curation; JJM writing—original draft preparation; JJM and UAK writing—review and editing; UAK visualization; SJM supervision; RRK project administration; SJM funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by BASF Professional & Specialty Solutions. The funder had no role in data collection, analysis or the decision to publish.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and will be available upon request.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to the Vector Control and Product Testing Unit (VCPTU) management, administrators and colleagues who helped in organizing logistics and materials allowing smooth performance of the study as well as insectary staffs.

Conflicts of Interest

JJM, ABM, FSCT, MP, DK, SHN, DSK, IM, IB, JM, JBM, RRK, PAK, SJM and UAK conducts product evaluations for a number of companies including BASF. JWA is employed by BASF Corporation, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA. SS is employed by BASF SE, Ludwigshafen, Germany. BASF and its Professional & Speciality Solutions division is a manufacturer of vector control products.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATP |

Adenosine triphosphate |

| CFV |

Control Flow Valve |

| DDT |

Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane |

| IACT |

Ifakara Ambient Chamber Test |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| IRS |

Indoor residual spray |

| ITN |

Insecticide Treated Nets |

| MEH |

Miniature-experimental hut |

| NMCP |

National Malaria Control Programmes |

| qRT-qPCR |

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| RT-qPCR |

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| RH |

Relative Humidity |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| WHO PQT/VCP |

World Health Organization Prequalification Team – Vector Control Products |

References

- WHOPES: Guidelines for testing mosquito adulticides for indoor residual spraying and treatment of mosquito nets. WHO/CDS/NTD/WHOPES/GCDPP/2006.3. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Pesticide Evaluation Scheme; 2006.

- Ngufor C, Critchley J, Fagbohoun J, N’Guessan R, Todjinou D, Rowland M: Chlorfenapyr (A Pyrrole Insecticide) Applied Alone or as a Mixture with Alpha-Cypermethrin for Indoor Residual Spraying against Pyrethroid Resistant Anopheles gambiae sl: An Experimental Hut Study in Cove, Benin. PLoS One 2016, 11:e0162210. [CrossRef]

- Oxborough RM, Kitau J, Matowo J, Mndeme R, Feston E, Boko P, Odjo A, Metonnou CG, Irish S, N’Guessan R, et al.: Evaluation of indoor residual spraying with the pyrrole insecticide chlorfenapyr against pyrethroid-susceptible Anopheles arabiensis and pyrethroid-resistant Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2010, 104:639-645. [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra K, Barik TK, Sharma P, Bhatt RM, Srivastava HC, Sreehari U, Dash AP: Chlorfenapyr: a new insecticide with novel mode of action can control pyrethroid resistant malaria vectors. Malar J 2011, 10:16. [CrossRef]

- Oxborough RM, N’Guessan R, Jones R, Kitau J, Ngufor C, Malone D, Mosha FW, Rowland MW: The activity of the pyrrole insecticide chlorfenapyr in mosquito bioassay: towards a more rational testing and screening of non-neurotoxic insecticides for malaria vector control. Malaria Journal 2015, 14:124. [CrossRef]

- Black BC, Hollingworth RM, Ahammadsahib KI, Kukel CD, Donovan S: Insecticidal Action and Mitochondrial Uncoupling Activity of AC-303,630 and Related Halogenated Pyrroles. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology 1994, 50:115-128. [CrossRef]

- Rund SS, Gentile JE, Duffield GE: Extensive circadian and light regulation of the transcriptome in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. BMC Genomics 2013, 14:218. [CrossRef]

- Balmert NJ, Rund SS, Ghazi JP, Zhou P, Duffield GE: Time-of-day specific changes in metabolic detoxification and insecticide resistance in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. J Insect Physiol 2014, 64:30-39. [CrossRef]

- Das De T, Pelletier J, Gupta S, Kona MP, Singh OP, Dixit R, Ignell R, Karmodiya K: Diel modulation of perireceptor activity influences olfactory sensitivity in diurnal and nocturnal mosquitoes. Febs j 2025, 292:2095-2118. [CrossRef]

- Suarez RK: Energy Metabolism during Insect Flight: Biochemical Design and Physiological Performance. Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 2000, 73:765-771. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann C, Briegel H: Flight performance of the malaria vectors Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles atroparvus. J Vector Ecol 2004, 29:140-153.

- Churcher TS, Stopard IJ, Hamlet A, Dee DP, Sanou A, Rowland M, Guelbeogo MW, Emidi B, Mosha JF, Challenger JD, et al.: The epidemiological benefit of pyrethroid & pyrrole insecticide treated nets against malaria: an individual-based malaria transmission dynamics modelling study. The Lancet Global Health 2024, 12:e1973-e1983. [CrossRef]

- Sherrard-Smith E, Ngufor C, Sanou A, Guelbeogo MW, N’Guessan R, Elobolobo E, Saute F, Varela K, Chaccour CJ, Zulliger R, et al.: Inferring the epidemiological benefit of indoor vector control interventions against malaria from mosquito data. Nature Communications 2022, 13:3862. [CrossRef]

- Silver JB, Service MW: Chapter 16 Experimental Hut Techniques. In Mosquito Ecology: Field Sampling Methods. Springer; 2008: 1494.

- Mosha JF, Matowo NS, Kulkarni MA, Messenger LA, Lukole E, Mallya E, Aziz T, Kaaya R, Shirima BA, Isaya G, et al.: Effectiveness of long-lasting insecticidal nets with pyriproxyfen-pyrethroid, chlorfenapyr-pyrethroid, or piperonyl butoxide-pyrethroid versus pyrethroid only against malaria in Tanzania: final-year results of a four-arm, single-blind, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2023. [CrossRef]

- Accrombessi M, Cook J, Dangbenon E, Sovi A, Yovogan B, Assongba L, Adoha CJ, Akinro B, Affoukou C, Padonou GG, et al.: Effectiveness of pyriproxyfen-pyrethroid and chlorfenapyr-pyrethroid long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) compared with pyrethroid-only LLINs for malaria control in the third year post-distribution: a secondary analysis of a cluster-randomised controlled trial in Benin. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2024. [CrossRef]

- Massue DJ, Lorenz LM, Moore JD, Ntabaliba WS, Ackerman S, Mboma ZM, Kisinza WN, Mbuba E, Mmbaga S, Bradley J, et al.: Comparing the new Ifakara Ambient Chamber Test with WHO cone and tunnel tests for bioefficacy and non-inferiority testing of insecticide-treated nets. Malaria Journal 2019, 18:153. [CrossRef]

- Kibondo UA, Odufuwa OG, Ngonyani SH, Mpelepele AB, Matanilla I, Ngonyani H, Makungwa NO, Mseka AP, Swai K, Ntabaliba W, et al.: Influence of testing modality on bioefficacy for the evaluation of Interceptor® G2 mosquito nets to combat malaria mosquitoes in Tanzania. Parasites & Vectors 2022, 15:124. [CrossRef]

- WHO: Data requirements and protocol for determining comparative efficacy of vector control products. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2024.

- Gillies MT: Studies in house leaving and outside resting of Anopheles gambiae Giles and Anopheles funestus Giles in East Africa. II. The exodus from houses and the house resting population. Bull Ent Res 1954, 45:375.

- Hudson JE: Trials of mixtures of insecticides in experimental huts in East Africa. II. The effects of mixtures of DDT with malathion on the mortality and behaviour of Anopheles gambiae Giles in verandah trap huts. WHO/VBC/75.575. pp. 15: World Health Organisation; 1975:15.

- Ojo T: An assessment of novel methods for evaluating insecticide based methods of vector control. University of London, 2009.

- Snetselaar J, Lees RS, Foster GM, Walker KJ, Manunda BJ, Malone DJ, Mosha FW, Rowland MW, Kirby MJ: Enhancing the Quality of Spray Application in IRS: Evaluation of the Micron Track Sprayer. Insects 2022, 13:523. [CrossRef]

- MR4: Methods in Anopheles Research Manual 2015 edition. 2016.

- WHO: Test procedures for insecticide resistance monitoring in malaria vector mosquitoes – 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2016.

- Bass C, D. N, M.J. D, S. WM, H. R, A. B, J. V: Detection of knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations in Anopheles gambiae : a comparison of two new high- throughput assays with existing methods. Mal J 2007, 6:111. [CrossRef]

- Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Altman DG: Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. Jama 2012, 308:2594-2604. [CrossRef]

- Che-Mendoza A, González-Olvera G, Medina-Barreiro A, Arisqueta-Chablé C, Bibiano-Marin W, Correa-Morales F, Kirstein OD, Manrique-Saide P, Vazquez-Prokopec GM: Efficacy of targeted indoor residual spraying with the pyrrole insecticide chlorfenapyr against pyrethroid-resistant Aedes aegypti. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021, 15:e0009822. [CrossRef]

- Tchouakui M, Assatse T, Tazokong HR, Oruni A, Menze BD, Nguiffo-Nguete D, Mugenzi LMJ, Kayondo J, Watsenga F, Mzilahowa T, et al.: Detection of a reduced susceptibility to chlorfenapyr in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae contrasts with full susceptibility in Anopheles funestus across Africa. Sci Rep 2023, 13:2363. [CrossRef]

- Oxborough RM, Seyoum A, Yihdego Y, Chabi J, Wat’senga F, Agossa FR, Coleman S, Musa SL, Faye O, Okia M, et al.: Determination of the discriminating concentration of chlorfenapyr (pyrrole) and Anopheles gambiae sensu lato susceptibility testing in preparation for distribution of Interceptor® G2 insecticide-treated nets. Malar J 2021, 20:316. [CrossRef]

- David MD: The potential of pro-insecticides for resistance management. Pest Management Science 2021, n/a. [CrossRef]

- Tchouakui M, Ibrahim SS, Mangoua MK, Thiomela RF, Assatse T, Ngongang-Yipmo SL, Muhammad A, Mugenzi LJ, Menze BD, Mzilahowa T, Wondji CS: Substrate promiscuity of key resistance P450s confers clothianidin resistance. Cell Rep 2024, 43. [CrossRef]

- Riveron JM, Watsenga F, Irving H, Irish SR, Wondji CS: High Plasmodium Infection Rate and Reduced Bed Net Efficacy in Multiple Insecticide-Resistant Malaria Vectors in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. J Infect Dis 2018, 217:320-328. [CrossRef]

- Mavridis K, Wipf N, Medves S, Erquiaga I, Müller P, Vontas J: Rapid multiplex gene expression assays for monitoring metabolic resistance in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Parasit Vectors 2019, 12:9. [CrossRef]

- WHO: Guidelines for laboratory and field testing of long-lasting insecticidal mosquito nets WHO/CDS/WHOPES/GCDPP/2005.11. Geneva: World Health Organisation Pesticide evaluation scheme (WHOPES); 2005.

- Malima RC, Nkya TE, Magesa SM, Mboera LE, Kisinza WN: Evaluation of the WHO cone bioassay method for quality control of LLINs. Malar J 2017, 16:48.

- N’Guessan R, Ngufor C, Kudom AA, Boko P, Odjo A, Malone D, Rowland M: Mosquito Nets Treated with a Mixture of Chlorfenapyr and Alphacypermethrin Control Pyrethroid Resistant Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus Mosquitoes in West Africa. PLoS ONE 2014, 9:e87710. [CrossRef]

- N’Guessan R, Odjo A, Ngufor C, Malone D, Rowland M: A Chlorfenapyr Mixture Net Interceptor® G2 Shows High Efficacy and Wash Durability against Resistant Mosquitoes in West Africa. PLoS One 2016, 11:e0165925. [CrossRef]

- Ngufor C, Fongnikin A, Hobbs N, Gbegbo M, Kiki L, Odjo A, Akogbeto M, Rowland M: Indoor spraying with chlorfenapyr (a pyrrole insecticide) provides residual control of pyrethroid-resistant malaria vectors in southern Benin. Malar J 2020, 19:249. [CrossRef]

- WHO: Manual for monitoring insecticide resistance in mosquito vectors and selecting appropriate interventions. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2022.

- Darriet F, Carnevale P: Evaluation of insecticide-treated nets in the laboratory: Comparison of tunnel and free-flying room tests. Med Vet Entomol 1995, 9:357-362.

- Fatou M, Müller P: 3D video tracking analysis reveals that mosquitoes pass more likely through holes in permethrin-treated than in untreated nets. Sci Rep 2024, 14:13598. [CrossRef]

- Yunta C, Ooi JMF, Oladepo F, Grafanaki S, Pergantis SA, Tsakireli D, Ismail HM, Paine MJI: Chlorfenapyr metabolism by mosquito P450s associated with pyrethroid resistance identifies potential activation markers. Scientific Reports 2023, 13:14124. [CrossRef]

- Oxborough RM, Kitau J, Matowo J, Feston E, Mndeme R, Mosha FW, Rowland MW: ITN mixtures of chlorfenapyr (Pyrrole) and alphacypermethrin (Pyrethroid) for control of pyrethroid resistant Anopheles arabiensis and Culex quinquefasciatus. PLoS One 2013, 8:e55781. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).