1. Introduction

Malaria remains an important public health problem globally. Approximately 247 million malaria cases and 619,000 deaths were recorded globally in 2023, where sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 95% of global malaria deaths, with children under five and pregnant women being disproportionately affected by the disease WHO, 2024 [

1]. However, considerable progress was made between 2000 and 2015, in which the annual deaths decreased from 841 000 to 542 000 [

2].

Much of this success has been attributed to the scale-up of vector control interventions, particularly the scale-up of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and the use of indoor residual spraying (IRS) of insecticides [

3]. Since 2015, however, increasing case incidence in several high-burden countries has been documented, implying stagnation in the progress of malaria reduction [

2]. Furthermore, the continued success of malaria vector control in sub- Saharan Africa is threatened by the spread of mosquito resistance to insecticides (used for ITNs and IRS) [

4]. Resistance to pyrethroids and other insecticide classes has been documented in multiple regions of Tanzania [

5]. Indeed, sustained malaria transmission has been recorded in areas with high resistance to multiple insecticides [

6,

7,

8].

The next-generation ITN products (dual-active-ingredient ITNs) have been developed as an alternative tool against pyrethroid-resistant mosquitoes [

9,

10]. The first new class of dual-active-ingredient ITNs were treated with a mixture of a pyrethroid (PY) and a synergist, piperonyl butoxide (PBO). PBO is a synergist that enhances insecticide toxicity by inhibiting the activity of metabolic enzymes (cytochrome P450metabolic enzymes)_that are commonly overexpressed in resistant vector populations and which often play a key role in metabolic resistance [

11,

12,

13].

PBO-ITNs received the WHO recommendation following cluster-RCTs in Tanzania, [

14] and Uganda [

15], where improved efficacy of two products (Olyset® Plus and PermaNet® 3.0) to reduce malaria cases in areas with resistant populations of malaria vectors was documented. With metabolic resistance being a more worrying and stronger mechanism than other mechanisms such as target site mutation, there has been a drive by the industry to manufacture PBO-ITNs. Between 2018 and 2023, seven PBO-ITNs received full WHO recommendation and these include Olyset® Plus (2018), PermaNet®3.0 (2018), Tsara Boost (2018), Tsara Plus (2018), Veeralin (2018), DuraNet Plus (2020), and Yorkool G3 (2023) [

16]. / During the same period, a total of 404 million of PBO-ITNs were delivered to sub-Saharan Africa, and in 2023, PBO-ITNs accounted for 58% of the nets delivered [

17].

The present study evaluated the efficacy of YAHE 4.0, a pyrethroid-PBO net against wild, free-flying, host-seeking pyrethroid-resistant Anopheles arabiensis s in experimental huts in Lower Moshi, north-eastern Tanzania.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Trial Site and Hut Design

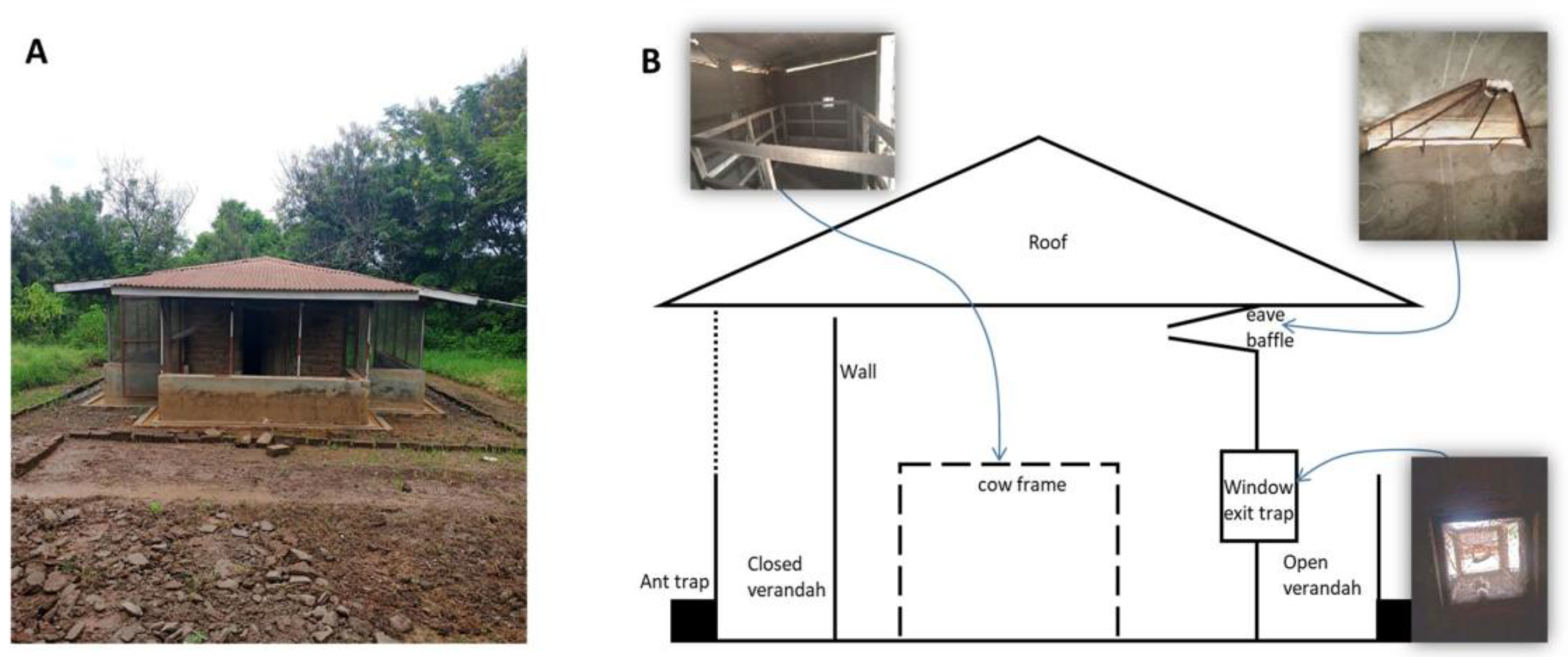

The study was carried out at Pasua field station, one of the Pan African Malaria Vector Research Consortium (PAMVERC) field stations located in the Lower Moshi area (3021'S, 37020'E). The area is located a few kilometers from Moshi town, and 800meters above sea level, south of Mount Kilimanjaro. Most of the population in the area is engaged in agriculture with irrigated rice, and sugar cultivation is the main crop. The non-irrigated crops include maize, beans, and bananas. Two rivers, namely Njoro and Rau, provide water which is used for irrigation. Livestock in this area are mainly cattle, goats, sheep, and (poultry. Irrigation activities provide an important breeding site for Anopheles arabiensis, the predominant malaria vector in the area22-28.

The type of huts where the trial was carried out is the standard traditional East African veranda trap-hut design, with brick walls plastered with mud on the inside, a wooden ceiling lined with hessian sackcloth, a corrugated iron roof, open eaves, with window traps and veranda traps on each side. The huts are surrounded by a water-filled moat to deter the entry of scavenging ants. There are two screened veranda traps on opposite sides of the huts to capture any mosquitoes that exit via the open eaves. The eaves of the two open verandas were baffled inwardly to allow the host-seeking mosquitoes into the hut and deter exiting through the openings.

2.2. Description of the Test Product

The test item (YAHE 4.0 LLIN) is an alpha-cypermethrin pyrethroid+PBO (incorporated into polyethylene) LLIN made of monofilament yarn (120 denier), fabric weight of 37.8g/m2, containing 6.6 ±25% g/kg alpha-cypermethrin and 2.4 ±25% g/kg PBO. The YAHE 4.0 LLIN was compared to three controls: an untreated net as a negative control, and two positive control nets, Interceptor® LLINs (BASF Corporation) and DuraNet Plus (Shobikaa Impex Private Limited, India). Both positive control nets are recommended for use in malaria prevention and control by the WHO Prequalification Team – Vector Control (Interceptor®: Prequalification reference number 002-002; DuraNet Plus: Prequalification reference number 006-003).

Description of control nets is as follows: Untreated polyester nets (size:180 cm W × 190 cm L × 150 cm H), Interceptor® polyester LLIN (size: 160 cm W × 180 cm L × 180 cm H; 100D AI: 5.0 g/kg Alpha-cypermethrin), fabric weigh of 40 g/m2, and DuraNet Plus polyethylene nets (size: 160 cm W × 180 cm L × 150 cm H; 150D; AI: 6.0 g/kg Alpha-cypermethrin + 2.2 g/kg PBO, fabric weigh of 36g/m2.

2.3. Preparation of Nets and Washing Procedure

From one unwashed YAHE 4.0 LLIN, one unwashed Interceptor®, and one unwashed DuraNet Plus, six 30 × 30 cm pieces were cut from positions as suggested in the WHO Pesticide Evaluation Scheme (WHOPES) LLIN testing guideline [

19]. Five net pieces from one unwashed negative control net were cut. One unwashed and one 20-times-washed net piece cut from adjacent positions were archived, and the other net pieces were used in cone bioassays before shipment for chemical analysis, with the exception of the unwashed negative control net piece.

Six whole YAHE 4.0 nets remained unwashed, while another six were washed 20 times. Similarly, six nets from each of the positive control nets (Interceptor® and DuraNet Plus) remained unwashed, while another six were washed 20 times. Six nets from the negative control remained unwashed. Whole nets were washed using Savon de Marseille soap and tap water. In brief, LLINs were washed for a total of 10 minutes, using a wooden paddle. They were manually stirred at a rate of 20 rotations per minute for 3 minutes; left to soak for 4 minutes; then manually stirred again as before for 3 minutes. After washing, the LLINs were rinsed twice in 10 liters of clean water following the same procedure. After rinsing, they were removed from the water and dried horizontally in the shade, and stored at ambient temperature. Before the nets were sent to the Pasua experimental hut site, all nets had 6 holes cut in them to simulate the conditions of a damaged net following the WHO 2013 WHOPES guidelines [

19].

2.4. Cone Bioassays

The first series of cone bioassays was run on the unused test item and positive control net piece unwashed and washed 20 times, as well as the unwashed negative control; 2 replicates per net piece and 5 An. gambiae s.s. Kisumu and An. gambiae Muleba-kis per replicate.

Similarly, 2 replicates per net piece and 5

An. arabiensis KGB and wild F1

An. arabiensis per replicate. In total 50 mosquitoes of each strain were used to test each unwashed and 20 times net piece of the untreated net, Interceptor® LLIN, DuraNet Plus LLIN and YAHE 4.0 LLIN. The second series of cone bioassays was run on net pieces acquired from hut-used unwashed and 20 times washed test item and positive control nets as well as an unwashed negative control

. Similar replicates per net piece, as well as the number and strain of mosquitoes, to the first series of cone bioassays were used. In total, 50 mosquitoes of each of the four strains were used to test each hut-used unwashed and washed Interceptor® LLIN, DuraNet Plus LLIN, and YAHE 4.0 LLIN. Cone bioassays followed the standard WHO procedures [

20]. Five 3-day female mosquitoes (sugar-fed) were introduced into each cone and exposed for 3 min. Mean knockdown at 60 minutes post-exposure and mortality at 24h post-exposure was calculated for each net. A mosquito was classified as knocked down or dead if it was immobile or unable to stand or take off, or fly in an uncoordinated manner at 60 minutes or 24 hours, respectively.

2.5. Experimental Hut Trial

Washed and unwashed candidate LLINs were evaluated using 7 East African experimental huts for their effects on the wild pyrethroid-resistant An. arabiensis mosquitoes.

The following 6 treatment arms were compared:

Unwashed YAHE 4.0 LLIN

Unwashed Interceptor® LLIN

Unwashed DuraNet Plus

YAHE 4.0 LLIN washed 20 times

Interceptor® LLIN washed 20 times

DuraNet Plus LLIN washed 20 times

Untreated polyester net

Treatment arms were listed from 1 to 7, then, using

https://hamsterandwheel.com/grids/index2d.php, the treatments were randomly put in a Latin square. Seven nets were used per treatment arm, and each of the 7 nets was tested for one night during the 7 consecutive nights. At the end of the 7 nights, the huts were carefully cleaned and aired to remove potential contamination.

The treatment arm was then rotated to a different hut to account for possible location bias i.e., differences between huts. The study was performed for 7 rounds over 7 weeks to ensure complete rotation through the huts. In the present Experimental hut trial study, we used the method by JD Challenger found at

https://github.com/JDChallenger/WHO_NI_Tutorial. to assess whether the study had sufficient power.

Proportional outcomes, including mortality and blood-feeding, were compared using mixed effects logistic regression where huts, cows, net replicates, and nightly observational error were included as random or fixed effects.

The primary outcomes measured in experimental huts were:

Deterrence (reduction in hut entry relative to the control huts fitted with untreated nets)

Induced exiting (the proportion of mosquitoes that are found in exit traps and verandahs relative to control)

Blood-feeding inhibition (the reduction in blood-feeding relative to the control)

Mortality (the proportion of mosquitoes killed)

Personal protection, which can be estimated by the calculation of:

Personal protection (%) =100 (Bu – Bt)/Bu, where Bu is the total number of blood-fed in the huts with untreated nets, and Bt is the total number of blood-fed in the huts with LLIN-treated nets

The overall killing effect of the treatment was estimated by the calculation:

Insecticidal effect (%) =100 (Kt – Ku)/Tu, where Kt is the number killed in the huts with LLIN-treated nets, Ku is the number dying in the huts with untreated nets, and Tu is the total collected from the huts with untreated nets.

2.6. WHO Insecticide Susceptibility Tests

During the hut trial, the susceptibility tests were carried out using wild female An. arabiensis mosquitoes that emerged from rearing of larvae which were collected from the breeding sites (rice paddies) near to experimental huts. The tests were carried out following the standard WHO protocol [

20], using the test kits and insecticide-impregnated papers. Batches of 25 mosquitoes in four replicates were exposed to insecticide-impregnated papers with diagnostic concentrations of Alpha-cypermethin (0.05%), cypermethrin (0.05%), and pirimiphos-methyl (0.25%), for 1 h in WHO test kits. The knockdown effects for all tested insecticides were recorded at 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 min. A control in two replicates (50 female Anopheles mosquitoes were used for each insecticide), each with an equal number of mosquitoes, were exposed to papers impregnated with oil and run concurrently. At the end of the exposure period, mosquitoes were transferred into holding tubes (lined with untreated papers) and provided with a 10% sugar solution in a cotton wool which was placed on top of the holding tube. Mortality was scored 24 h post-exposure. The susceptibility tests were carried out in a room with 25 ± 2 °C temperatures and 80 ± 10% humidity.

2.7. Chemical Analysis

At the conclusion of the hut study, a total of 60 pieces of netting, 30 × 30 cm in size, used in cone bioassays, individually wrapped in aluminium foil, labelled with the test or reference item code on the outside were shipped to Walloon Agricultural Research Centre (CRA-W), Carson Building, RueduBordia,11, B-5030–Gembloux, Belgium, for chemical analysis. These net pieces include 20 pieces of each the Interceptor® LNs, DuraNet Plus LNs, and YAHE 4.0 LNs as indicated in

Table 1.

The fabric weight and the active substances / synergist content were measured on the net samples of YAHE® 4.0, Interceptor®, and DuraNet® Plus. The alpha-cypermethrin and piperonyl butoxide content in net samples of YAHE® 4.0 and DuraNet® Plus was determined using the combined CRA-W internal methods PA-U10-RESSM016 and PA-U10-RESSM026 with extraction with n-heptane using dicyclohexyl phthalate as internal standard and determination by Gas Chromatography with Flame Ionisation Detection (GC-FID). The alpha-cypermethrin content in net samples of Interceptor® was determined using the adapted CIPAC 454/LN/M2/3with extraction with n-heptane using dicyclohexyl phthalate as internal standard and determination by Gas Chromatography with Flame Ionisation Detection (GC-FID).The fabric weight (mass of net per m²) was determined on net samples using the CRA-W method PA-U10-NET001 based on the ISO 3801 method in order to convert the active substance content from g/kg into mg/m². The performance of the analytical methods was controlled during the analysis of samples in order to validate the analytical results.

2.8. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using STATA version 16.1. Proportions of mosquitoes knocked down and dead were calculated for all experiments. Logistic regression was used for proportional data (adjusting for the effect of hut and cow) and Poisson regression for numerical data. The odds ratios obtained from a logistic regression were used to determine the non-inferiority of the test item to the positive control (DuraNet Plus LN / Interceptor® LN). Variance estimates were adjusted for clustering by each hut night of collection. The primary criteria in the evaluation were blood-feeding inhibition and mortality. Non-inferiority analysis was conducted following WHO guidelines taking an odds ratio corresponding to 7% non-inferiority margin [

21].The results of the susceptibility tests were evaluated as recommended by WHO criteria [

20], as follows: 98–100% mortality indicates susceptibility, 90–97% mortality indicates a possible resistance candidate, and less than 90% mortality suggests resistance.

3. Results

3.1. Cone Bioassay Tests Before the Hut Trial

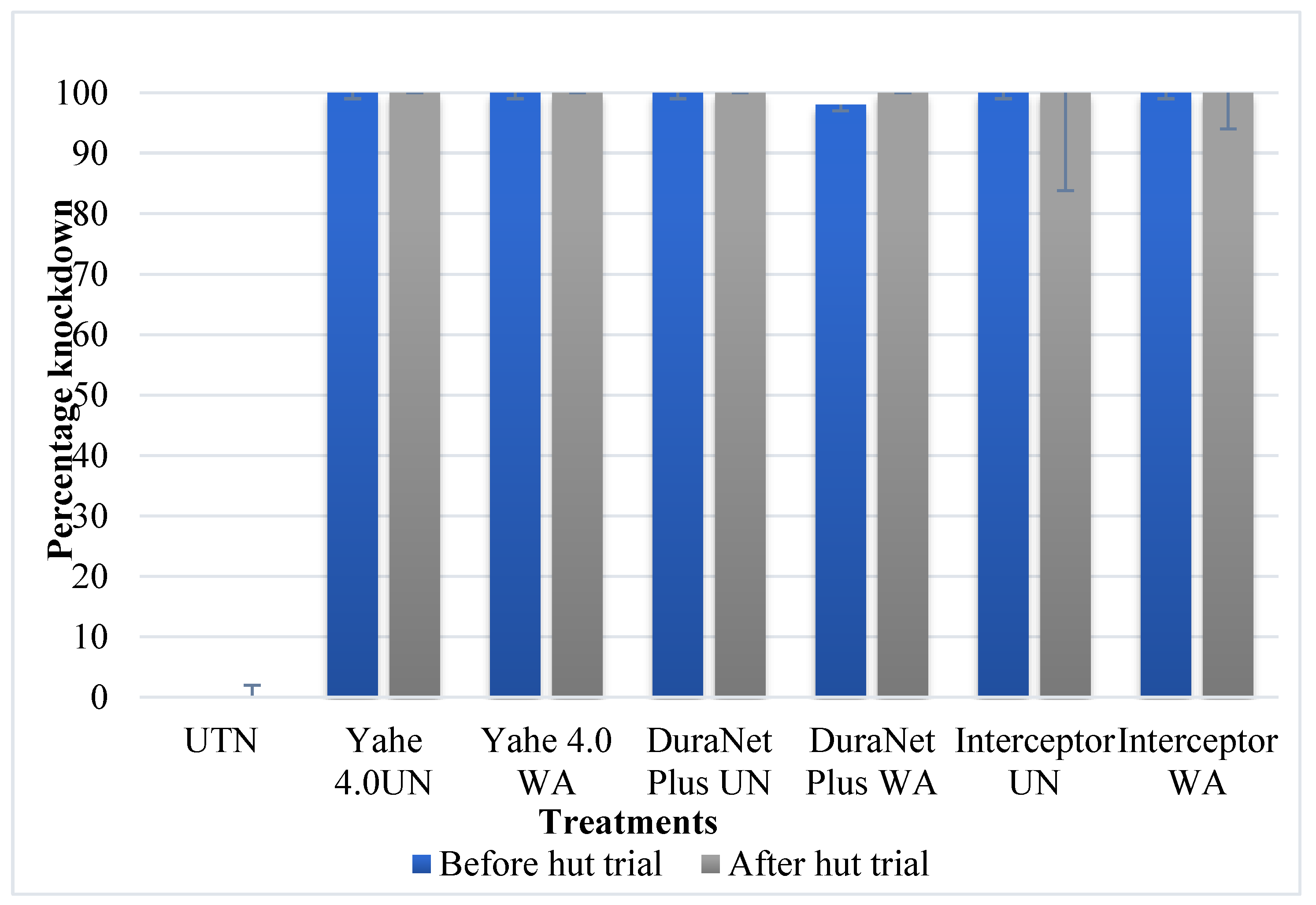

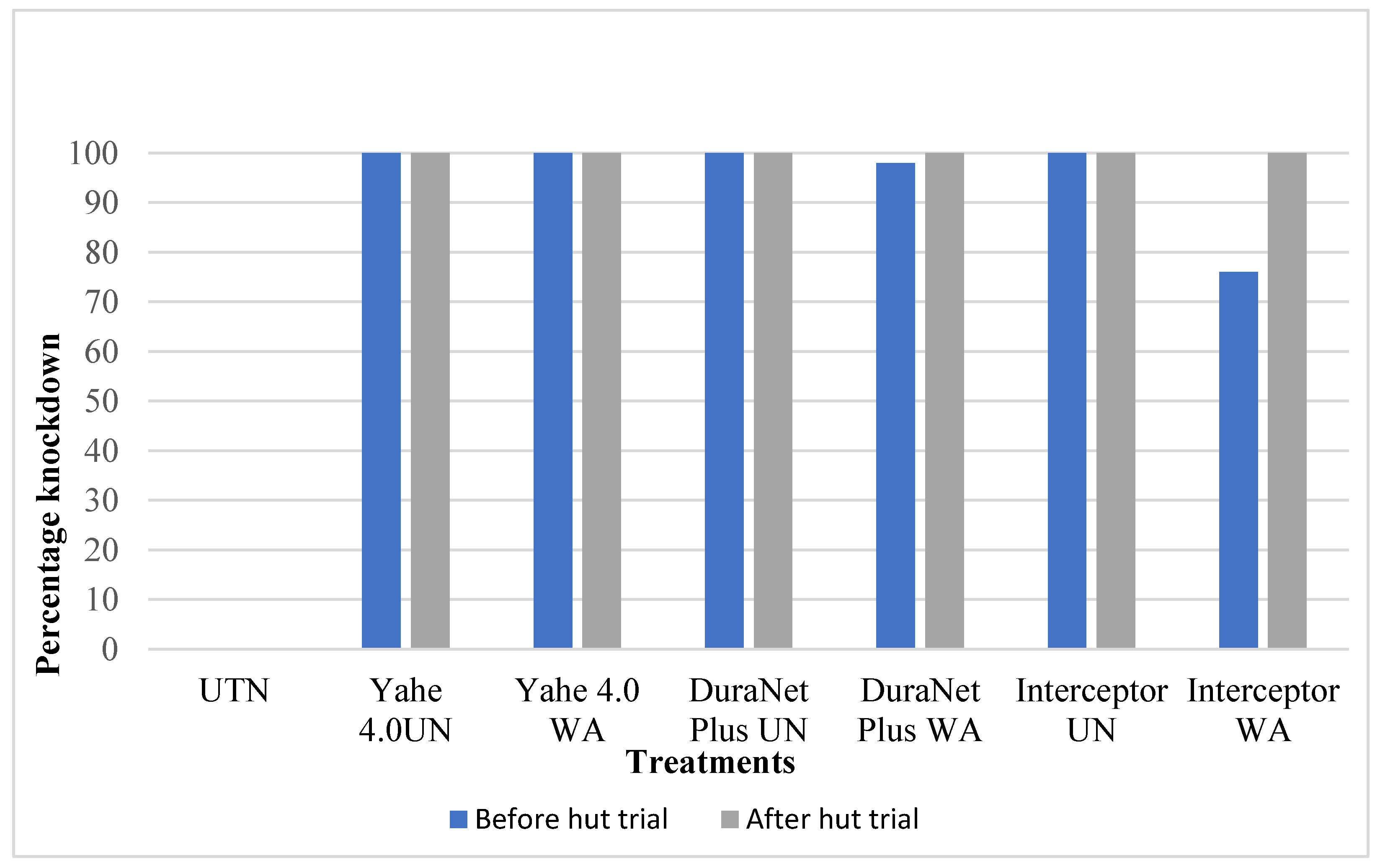

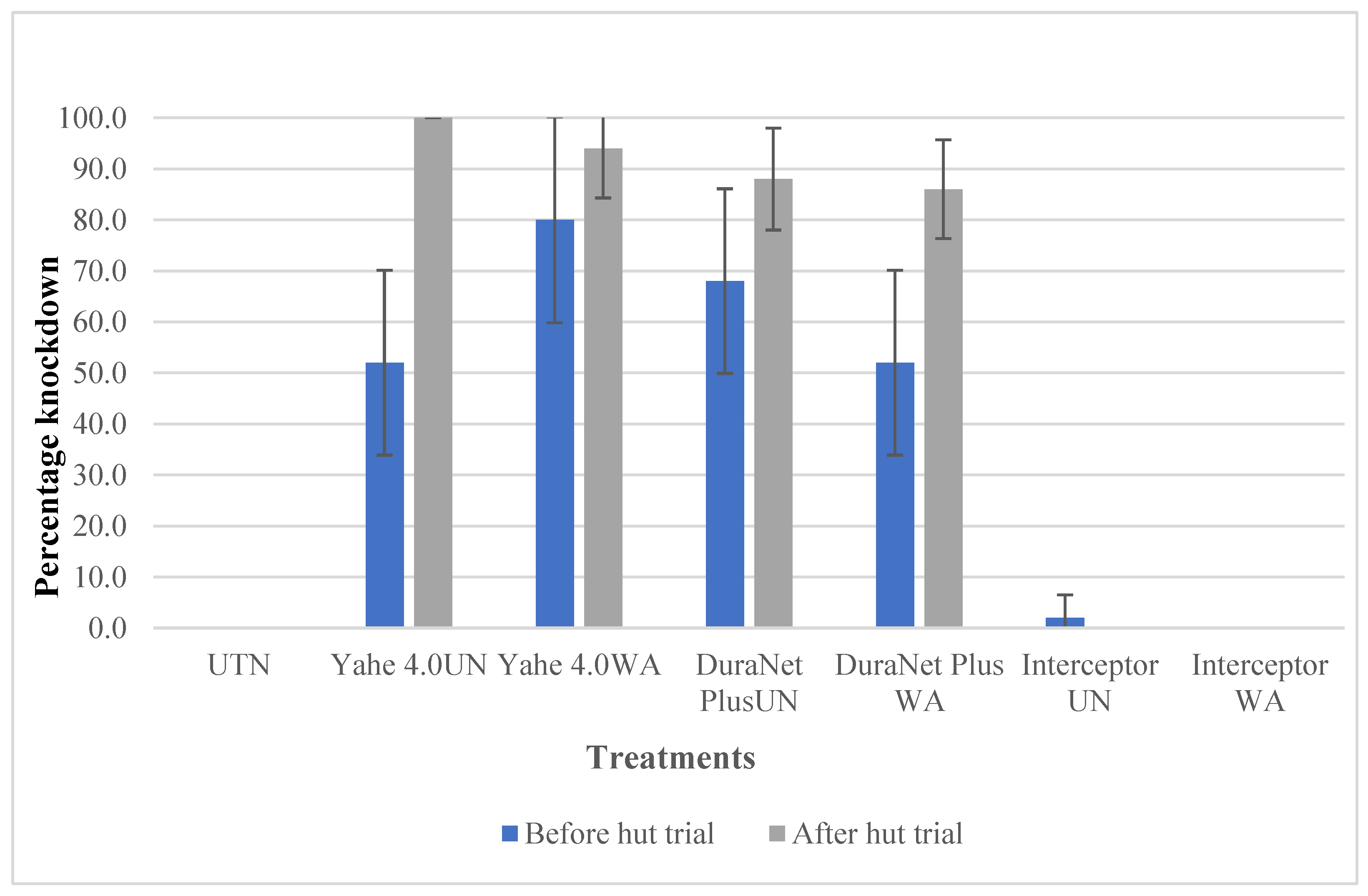

Before the hut trial, the 1-h knockdown was 100% for all treatment susceptible strains except for DuraNet Plus washed 20 times (98%), for both Kisumu and KGB strains, and Interceptor washed 20 times (76%) for the KGB strain. Low to high knockdown was recorded for pyrethroid-resistant strains of Muleba-Kis and wild Anopheles arabiensis across all LLIN types, ranging from 0% for washed Interceptor LLIN with Muleba-Kis to 100% for both unwashed DuraNet Plus wild An. arabiensis and 20× washed YAHE 4.0 LLIN with Muleba-Kis. (Figures 1a–4a).

Figure 1a.

Knockdown rates during cone bioassays before hut trial and after experimental hut trials using laboratory susceptible An. gambiae s.s Kisumu strain (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

Figure 1a.

Knockdown rates during cone bioassays before hut trial and after experimental hut trials using laboratory susceptible An. gambiae s.s Kisumu strain (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

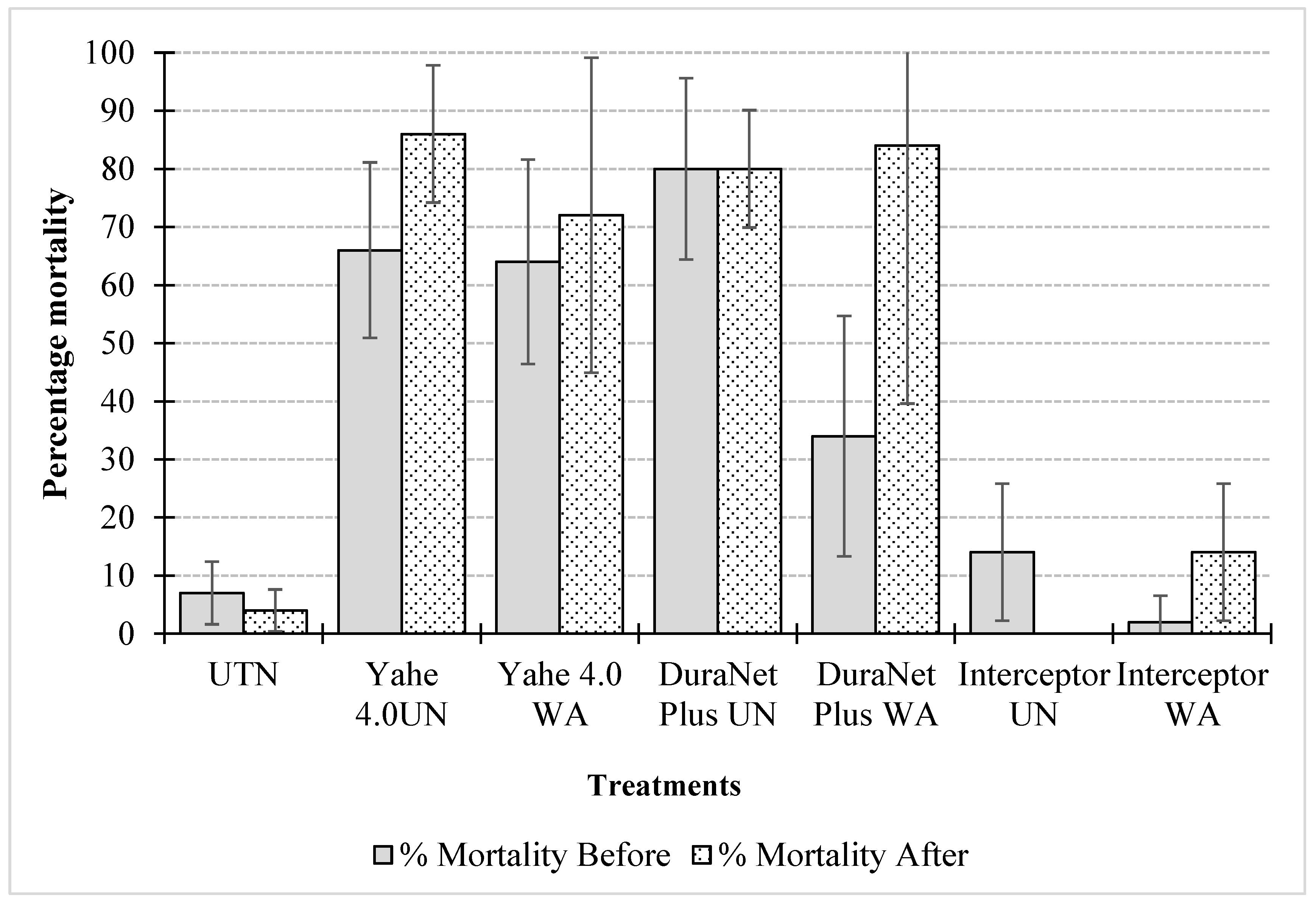

Figure 1b.

Mortality rates during cone bioassays before the hut trial and after the hut trial using Kisumu strain UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

Figure 1b.

Mortality rates during cone bioassays before the hut trial and after the hut trial using Kisumu strain UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

Figure 2a.

Knockdown rates during cone bioassays before hut trial and after experimental hut trials using laboratory susceptible An. arabiensis KGB strain (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

Figure 2a.

Knockdown rates during cone bioassays before hut trial and after experimental hut trials using laboratory susceptible An. arabiensis KGB strain (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

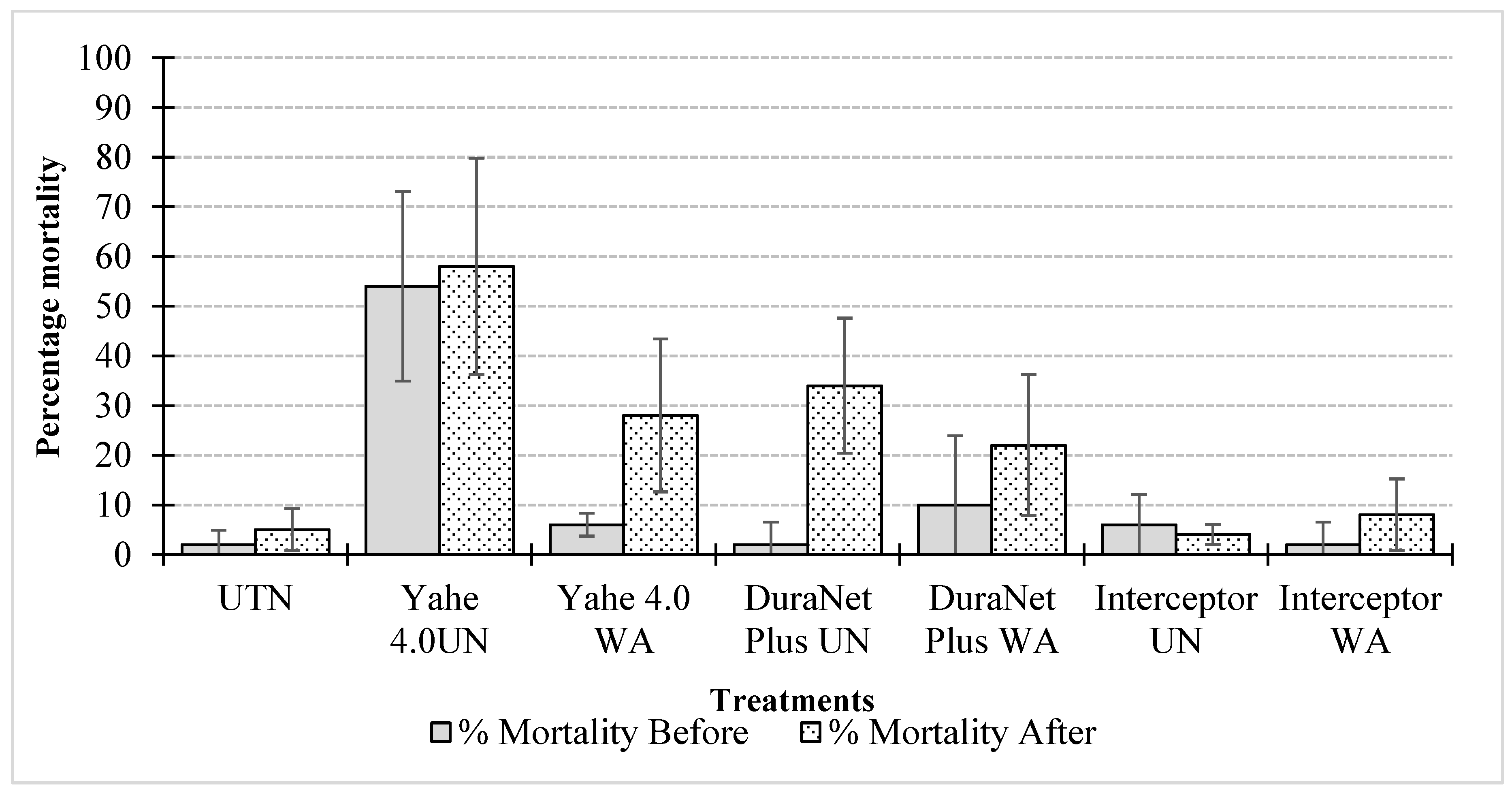

Figure 2b.

Mortality rates during cone bioassays before the hut trial and after the hut trial using susceptible An. arabiensis KGB strain (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

Figure 2b.

Mortality rates during cone bioassays before the hut trial and after the hut trial using susceptible An. arabiensis KGB strain (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

Figure 3a.

Knockdown rates during cone bioassays before hut trial and after experimental hut trials using laboratory reared pyrethroid-resistant An. gambiae s.s Muleba-Kis strain (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

Figure 3a.

Knockdown rates during cone bioassays before hut trial and after experimental hut trials using laboratory reared pyrethroid-resistant An. gambiae s.s Muleba-Kis strain (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

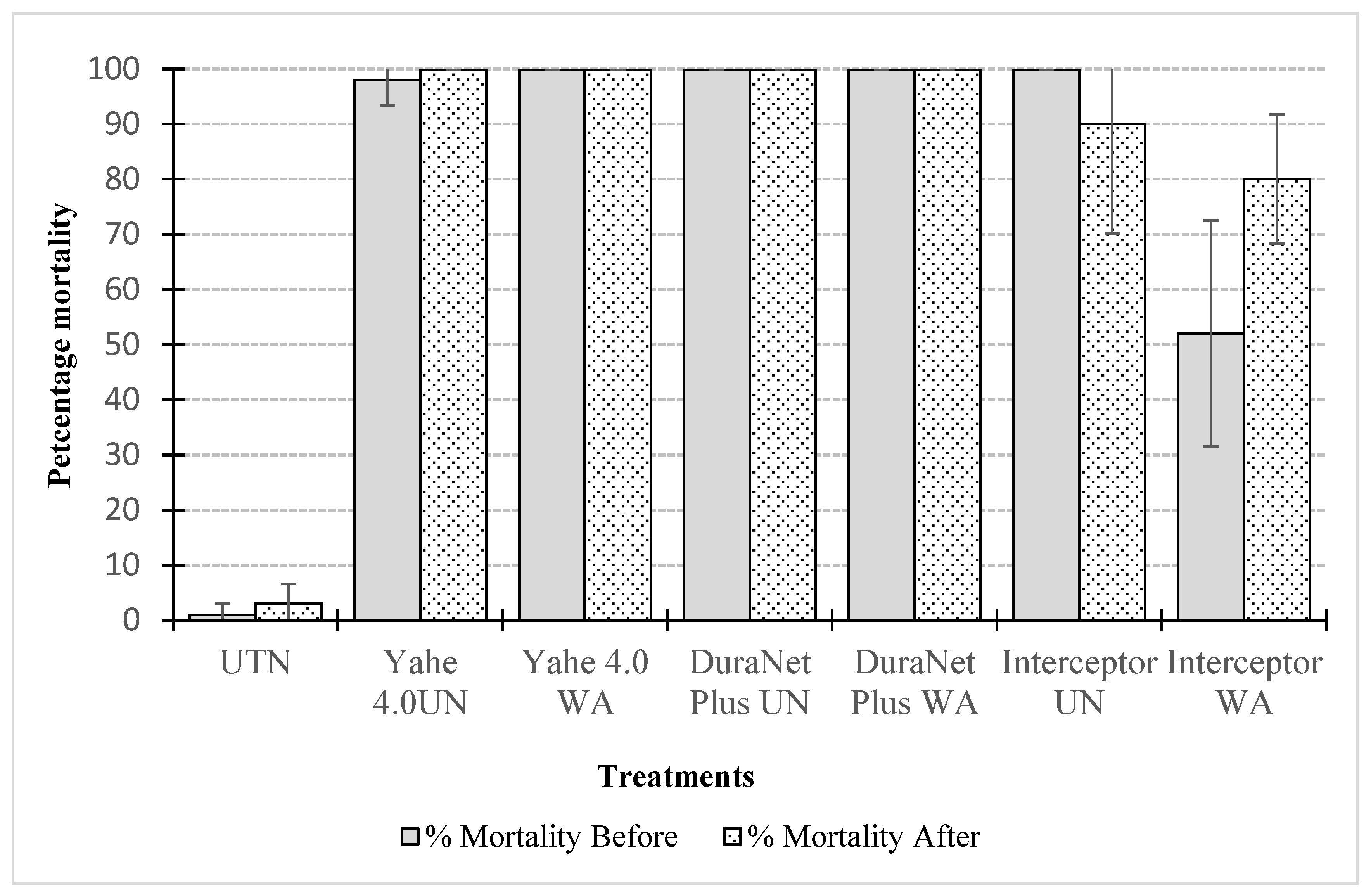

Figure 3b.

Mortality rates during cone bioassays before the hut trial and after the hut trial using laboratory-reared pyrethroid resistant Muleba-Kis strain UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

Figure 3b.

Mortality rates during cone bioassays before the hut trial and after the hut trial using laboratory-reared pyrethroid resistant Muleba-Kis strain UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

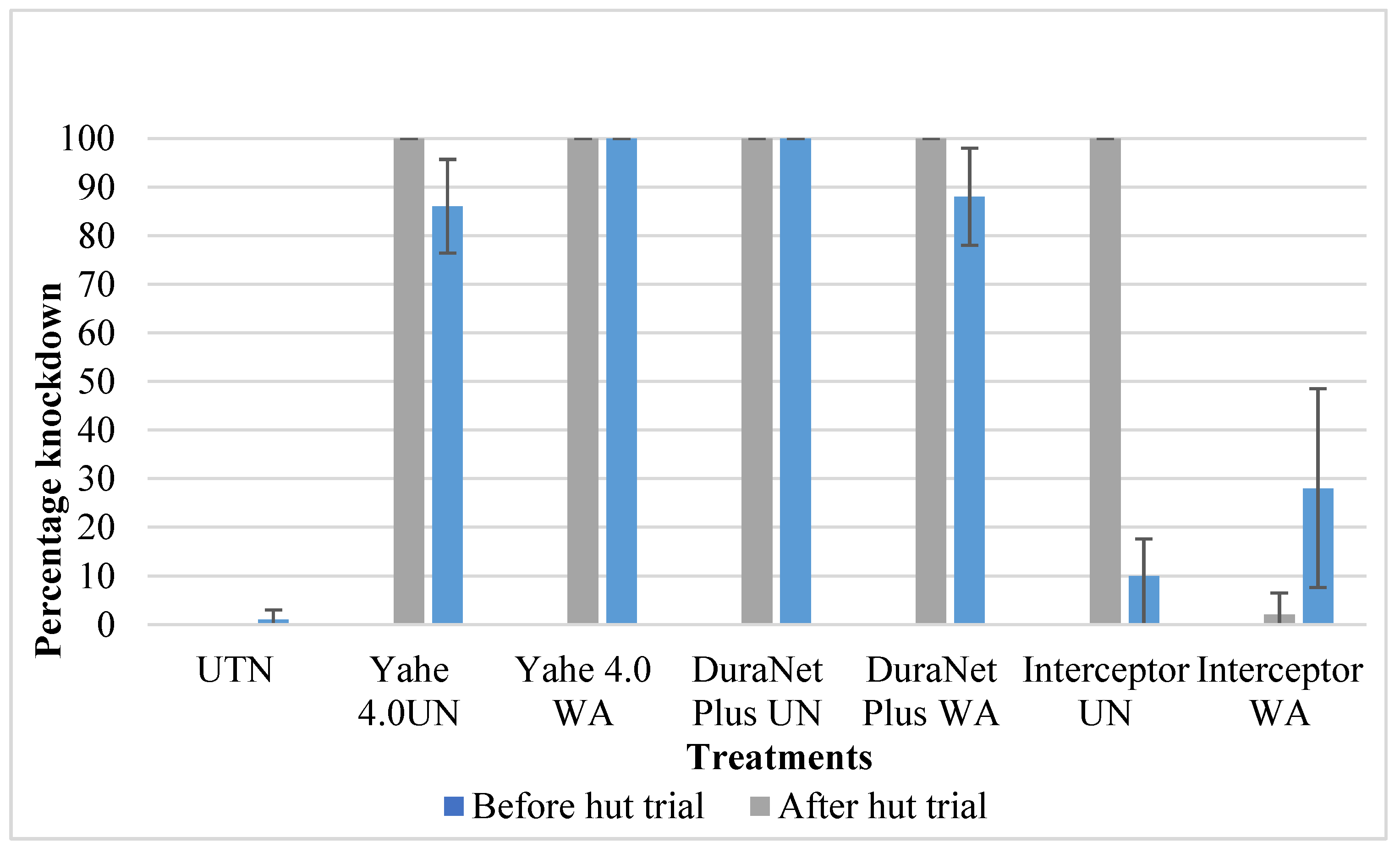

Figure 4a.

Knockdown rates during cone bioassays before hut trial and after experimental hut trials using wild pyrethroid-resistant An. arabiensis from the study area (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

Figure 4a.

Knockdown rates during cone bioassays before hut trial and after experimental hut trials using wild pyrethroid-resistant An. arabiensis from the study area (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

For susceptible strains, the mortality rates were 100%. However, it is strange that for Kisumu strain, Interceptor LLINs induced mortality rates of 76% and 96% for unwashed and washed, respectively. Furthermore, the Interceptor LLIN washed 20× induced only a 52% mortality rate with the KGB susceptible strain.For Muleba-Kis, low to moderate mortality rates were recorded for resistant strains, ranging from 2% (-0.3%-6.5%) for washed interceptor LLIN to 80% (64.4%-96.5%) for unwashed DuraNet Plus LLIN. However, the mortality for the unwashed DuraNet Plus LLIN was ot significantly different from that of unwashed YAHE 4.0 LLIN, 66% (50.8%-81.1%) and that of washed YAHE 4.0 LLIN, 64% (46.4%-81.5%). For the wild An. arabiensis, very low mortality rates were recorded except for unwashed YAHE 4.0 LLIN, which induced a mortality rate of 54% (34.9-73.1%). (Figures 1b–4b).

Figure 4b.

Mortality rates during cone bioassays before the hut trial and after the hut trial using wild pyrethroid resistant An. arabiensisfrom the study area (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

Figure 4b.

Mortality rates during cone bioassays before the hut trial and after the hut trial using wild pyrethroid resistant An. arabiensisfrom the study area (UTN=Untreated net; UN=Unwashed; WA=Washed).

3.2. Cone Bioassays After the Hut Trial

After the hut trial, the 1-h knockdown was 100% for all treatments with both susceptible strains (Kisumu and KGB) (Figures 1a and 2a). This was the same for the resistant Muleba-Kis strain that induced 100% knockdown, except for the washed Interceptor LLIN, which induced only a 1% knockdown rate. For resistant wild An.arabiensis, there was no significant difference between the knockdown rates of washed and unwashed LLINs.

However, the highest knockdown rates were recorded for YAHE LLINs (94% and 100%), while the moderate knockdown rates were recorded for the DuraNet Plus LLINs (86% and 88%). The knockdown rates for Interceptor LLINs were 0% with wild An.arabiensis (Figure 3a, 3a).

The mortality rates were high (100%) for susceptible strains, except Interceptor LLINs induced mortality rates of 84% and 68% for unwashed and washed nets, respectively. For the susceptible KGB strain, Interceptor LLIN induced higher mortality rates than those of Kisumu strain, i.e.90% for unwashed net and 80% washed net. (Figure 1b, 2b).

For resistant strains, the mortality rates were less than 90%. For Muleba-Kis, the highest mortality rate was 86% (74.2% - 97.8%) for the YAHE 4.0 unwashed LLIN, while the lowest was 0% for the Interceptor unwashed LLIN. There was no significant difference between the mortality rates of Muleba-Kis exposed to washed YAHE 4.0 LLIN 72% (44.8%-99.1%) and washed DuraNet Plus 84% (39.6%-128.4%). However, there was a significant difference between the mortality rates of Muleba-Kis exposed to unwashed YAHE 4.0 LLIN 86% (74.2% - 97.8%) and unwashed DuraNet Plus 30% (19.9%-40.1%). For the pyrethroid- resistant wild An. arabiensis, the mortality rates remained consistently low after the trial, ranging from 4% to 8% for interceptor LLINs to 58% for unwashed YAHE 4.0 LLIN (Figures 3b and 4b).

3.3. Hut Trial Results

3.3.1. Number of Mosquitoes Collected from Huts and Exiting Rates

Both

Anopheles arabiensis, predominant malaria vector in the study area and

Culex quinquefasciatus were (s.l.) were collected from experimental huts. The

Culex quinquefasciatus data have not been included in this report. A total of 2,901 female

An. arabiensis were collected over a period of 112 nights. The average (geometric mean) number of

An. arabiensis mosquitoes per treatment arm per night ranged from 2.6 to 6.3 and all trial arms recorded high

An. arabiensis exiting rates of > 82 % (

Table 1).

3.3.2. Blood-Feeding

The blood-feeding rates for YAHE 4.0 nets (32.1% and 32.8%) before and after being washed 20×, respectively, were lower than other treatments except Interceptor LLINs washed 20×, where blood feeding success was 30.4% (

Table 1). Blood-feeding rates recorded in all treatment arms were significantly lower than the untreated control arm, except for washed DuraNet Plus (AOR = 1.0; 95% CI = 0.7 – 1.3; p = 0.765; Z = -0.30). Blood feeding inhibition was highest in the washed Interceptor arm followed by the unwashed and washed YAHE 4.0 arms (

Table 1). The non-inferiority analysis showed that unwashed YAHE 4.0 was non-inferior and superior to unwashed Interceptor while washed YAHE 4.0 was non-inferior to washed Interceptor in terms of blood feeding (

Table 2). Furthermore, unwashed YAHE 4.0 was non-inferior to unwashed DuraNet Plus while washed YAHE 4.0 was superior to washed DuraNet Plus (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Exiting, blood feeding and mortality of wild free-flying Anopheles arabiensis in experimental huts.

Table 2.

Exiting, blood feeding and mortality of wild free-flying Anopheles arabiensis in experimental huts.

| Variables |

Type of LLIN |

| Untreated |

YAHE 4.0 |

YAHE 4.0 |

Interceptor |

Interceptor |

DuraNet Plus |

DuraNet Plus |

| No of washes |

0 |

0 |

20 |

0 |

20 |

0 |

20 |

| Total females caught |

374 |

343 |

326 |

492 |

709 |

287 |

370 |

Mean females

caught/night |

3.3 |

3.1 |

2.9 |

4.4 |

6.3 |

2.6 |

3.3 |

| Total females exited |

312 |

284 |

268 |

424 |

594 |

248 |

304 |

% Exophily

(95% CI) |

83.4

(79.6 – 87.1) |

82.8

(78.8 – 86.8) |

82.2

(78.1 – 86.4) |

86.2

(83.1 – 89.2) |

83.8

(81.1 – 86.5) |

86.4

(82.4 – 90.4) |

82.2

(78.3 – 86.1) |

| Total females blood fed |

171 |

110 |

107 |

188 |

216 |

101 |

167 |

% Blood fed

(95% CI) |

45.7

(40.6 – 50.8) |

32.1

(27.1 – 37.0) |

32.8

(27.7 – 37.9) |

38.2

(33.9 – 42.5) |

30.4

(27.1 – 33.8) |

35.2

(29.7 – 40.7) |

45.1

(40.1 – 50.2) |

Blood feeding AOR

(95% CI)

P-value; z-value |

1.0 |

0.5

(0.3 – 0.7)

< 0.000; -4.19 |

0.6

(0.4 – 0.8)

0.001; -3.22 |

0.7

(0.5 – 1.0)

0.044; -2.02 |

0.6

(0.5 – 0.8)

0.001; -3.28 |

0.6

(0.4 – 0.9)

0.009; -2.62 |

1.0

(0.7 – 1.3)

0.765; -0.30 |

| % Blood feeding inhibition |

0 |

29.9 |

28.2 |

16.4 |

33.4 |

23.0 |

1.3 |

| Total females dead |

17 |

159 |

162 |

238 |

313 |

155 |

206 |

% Mortality

(95% CI) |

4.5

(2.4 – 6.6) |

46.4

(41.1 – 51.6) |

49.7

(44.3 – 55.1) |

48.4

(44.0 – 52.8) |

44.1

(40.5 – 47.8) |

54.0

(48.2 – 59.8) |

55.7

(50.6 – 60.7) |

Mortality AOR

(95% CI)

P-value; Z-value |

1 |

66.9

(22.7 – 197.4)

< 0.000; 7.62 |

74.9

(25.4 – 220.9)

< 0.000; 7.82 |

51.9

(17.7 – 151.8)

< 0.000; 7.21 |

54.6

(18.7 – 159.1)

< 0.000; 7.32 |

83.1

(27.9 – 247.1)

< 0.000; 7.95 |

60.6

(20.6 – 178.3)

< 0.000; 7.45 |

| % Overall killing effect |

0 |

38.0 |

38.8 |

59.1 |

79.1 |

36.9 |

50.5 |

Table 3.

Non-inferiority analysis of unwashed and washed Interceptor, DuraNet Plus and YAHE 4.0 ITNs in terms of Blood feeding.

Table 3.

Non-inferiority analysis of unwashed and washed Interceptor, DuraNet Plus and YAHE 4.0 ITNs in terms of Blood feeding.

| Outcome |

Reference net |

Candidate net |

AOR |

95% CI

(p-value, Z- value) |

Non

inferiority

margin |

Test outcome |

Primary: Mortality

(72 hours) |

Unwashed Interceptor™ |

Unwashed YAHE 4.0 |

0.66 |

0.48 – 0.92

(0.014, -2.47) |

1.33 |

Non-inferior and superior |

| Washed Interceptor™ |

Unwashed YAHE 4.0 |

0.93 |

0.68 – 1.27

(0.665, -0.43) |

1.37

|

Non-inferior and not superior |

| Unwashed DuraNet Plus |

Unwashed YAHE 4.0 |

0.78 |

0.54 – 1.13

(0.194, -1.30) |

1.34

|

Non-inferior and not superior |

| Washed DuraNet Plus |

Washed YAHE 4.0 |

0.64 |

0.47 – 0.85

(0.004, -2.91) |

1.32

|

Non – inferior and superior |

Pooled unwashed and washed non-inferiority analysis showed that YAHE 4.0 was non-inferior and superior to both Interceptor (AOR= 0.80; 95% CI = 0.64 – 1.00; non-inferiority margin, NIM= 1.35; p-value = 0.049) and DuraNet Plus (OR=0.67; 95% CI=0.52 – 0.86; NIM=1.33; p-value= 0.002) in terms of blood feeding.

3.3.3. Mortality

The likelihood of

An. arabiensis mortality in all treated arms was significant (AOR ≥ 17.7; P <0.000) , ranging from 44.1% to 55.7% compared to the mortality of the control arm (4.5%) (

Table 2). The percentage mortality recorded for unwashed YAHE 4.0 LLIN was 46.4% (41.1 – 51.6%) while that of 20 times washed YAHE 4.0 LLIN was higher, 49.7% (44.3 – 55.1). However, percentage mortality recorded for DuraNet Plus unwashed and 20 times washed was 54.0% (48.2 – 59.8%) and 55.7% (50.6 – 60.7%) respectively, while that of Interceptor LLIN unwashed and 20 times washed was 48.4% (44.0-52.8) and 44.1% (40.5-47.8%) respectively (Figure 5).

Table 4.

Non-inferiority analysis of unwashed and washed Interceptor, DuraNet Plus and YAHE 4.0 ITNs in terms of Mortality.

Table 4.

Non-inferiority analysis of unwashed and washed Interceptor, DuraNet Plus and YAHE 4.0 ITNs in terms of Mortality.

| Outcome |

Reference net |

Candidate net |

OR |

95% CI

(p-value, Z- value) |

Non

inferiority

margin |

Target outcome |

Test outcome |

Primary: Mortality

(72 hours) |

Unwashed Interceptor™ |

Unwashed YAHE 4.0 |

1.29 |

0.90 – 1.84

(0.161, 1.40) |

0.75 |

Superiority |

Non-inferior and not superior |

| Washed Interceptor™ |

Unwashed YAHE 4.0 |

1.37 |

0.98 – 1.91

(0.061, 1.87) |

0.75

|

Superiority |

Non-inferior and not superior |

| Unwashed DuraNet Plus |

Unwashed YAHE 4.0 |

0.80 |

0.54 – 1.20

(0.290, -1.06) |

0.76

|

Non-inferiority |

Non-inferiority not shown |

| Washed DuraNet Plus |

Washed YAHE 4.0 |

1.24 |

0.86 – 1.78

(0.257, 1.13) |

0.76

|

Non-inferiority |

Non – inferior and not superior |

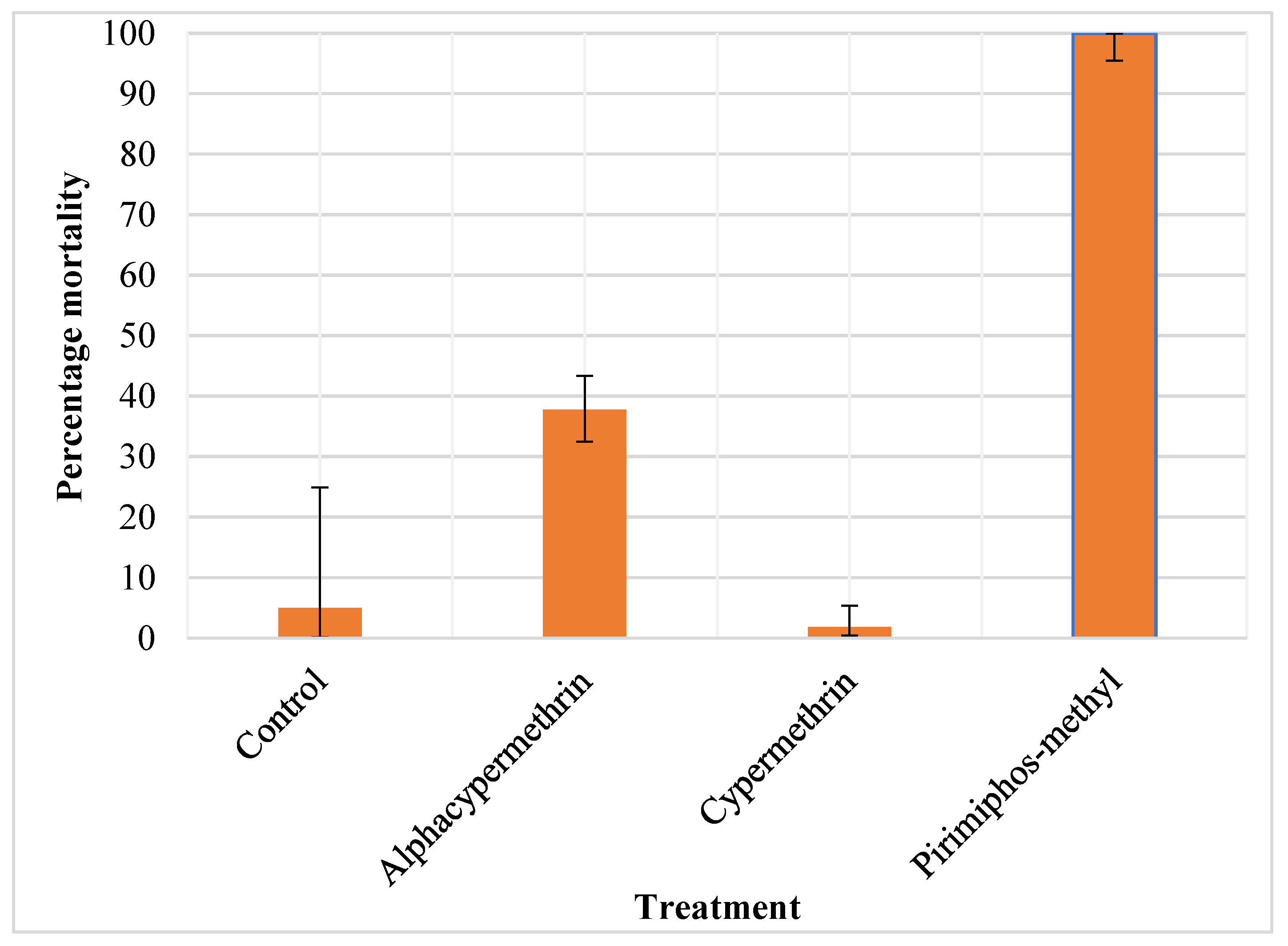

3.4. WHO Susceptibility Tests

The mortality rates of wild

An. arabiensis exposed to different insecticides are summarized in

Figure 6. Briefly, the mortality rate for the wild

An.arabiensis exposed to 0.0.5% alphacypermethrin papers was found to be 38% while the mortality rate for cypermethrin was 2%, and that of pirimiphos-methyl was 100%. Control mortality of the

An. arabiensis exposed to untreated paper was 5%.

Figure 6.

Mortality rates of wild An. arabiensis to alpha-cypermethrin, cypermethrin and pirimiphos-methyl.

Figure 6.

Mortality rates of wild An. arabiensis to alpha-cypermethrin, cypermethrin and pirimiphos-methyl.

Figure 7.

East African style experimental hut (

A) and schematic diagram of its set up in this study (

B).

Source: Mbewe et al. (2025) [

18].

Figure 7.

East African style experimental hut (

A) and schematic diagram of its set up in this study (

B).

Source: Mbewe et al. (2025) [

18].

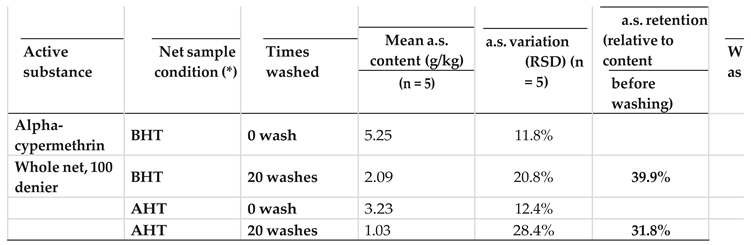

3.5. Chemical Analysis

The analytical results regarding the determination of the active substance / synergist content on incorporated net samples of YAHE® 4.0 LN and DuraNet® Plus LN and on coated net sample Interceptor® LN are summarized in Table 2a-e.

The amount of Alpha-cypermethrin in the YAHE® 4.0 LN before washing and before the trial was found to be 8.70 g/kg. Once the net was washed 20 times, the amount dropped to 8.25 g/kg. After the trial, the amount of Alpha-cypermethrin in unwashed YAHE® 4.0 LN was 8.33 g/kg, slightly lower than the amount that was observed before the trial, while the amount of Alpha- cypermethrin after 20 washes was 7.75 g/kg (Table 2a). Likewise, the amount of PBO in the YAHE® 4.0 LN before washing and before the trial was found to be 3.46 g/kg . Once the net was washed 20 times, the amount dropped to 3.08 g/kg. After the trial, the amount of PBO in unwashed YAHE® 4.0 LN was 3.11 g/kg, slightly lower than the amount that was observed before the trial, while the amount of PBO after 20 washes was 2.73g/kg (Table 2a). Also, the YAHE® 4.0 LN had a very high wash resistance index to Alpha-cypermethrin (̴100%) with very high retention of 94.9% and 93% before the hut trial and after the hut trial, respectively (Table 2a). The wash resistance index for the PBO was also very high, i.e.99.4% before the hut trial and 99.3% after the hut trial. However, the retention of PBO was slightly lower than that of Alpha-cypermethrin, 88.9% before the hut trial and 87.7% after the hut trial (Table 2b).

For the active positive comparator, the DuraNet® Plus LN, the amount of Alpha-cypermethrin before washing and before the trial was found to be 6.11 g/kg. Once the net was washed 20 times, the amount dropped to 5.53 g/kg. After the trial, the amount of Alpha-cypermethrin in unwashed DuraNet® Plus LN was 5.91 g/kg, slightly lower than the amount that was observed before the trial, while the amount of Alpha-cypermethrin after 20 washes was 5.55 g/kg (Table 7a). Likewise, the amount of PBO in the DuraNet® Plus LN before washing and before the trial was found to be 1.86 g/kg. Once the net was washed 20 times, the amount dropped to 1.66 g/kg. After the trial, the amount of PBO in unwashed DuraNet® Plus LN was 1.71 g/kg, slightly lower than the amount that was observed before the trial, while the amount of PBO after 20 washes was 1.61g/kg (Table 2c). The wash resistance index for Alpha-cypermethrin was also very high (̴ 100%), with its retention being slightly lower than that of Alpha-cypermethrin in the YAHE® 4.0 LN (Table 2c). Likewise, the wash resistance index to PBO in the DuraNet® Plus LN was approximately 100% as for the YAHE® 4.0 LN. However, retention of PBO in the DuraNet® Plus LN was 89.2% and 93.9% before the hut trial and after the hut trial, respectively, while the retention of PBO in the YAHE® 4.0 LN was 89.9% and 87.7% before the hut trial and after the hut trial, respectively (Table 2d).

For the standard positive comparator, the Interceptor® LN, the amount of Alpha-cypermethrin before washing and before the trial was found to be 5.25 g/kg. Once the net was washed 20 times, the amount dropped significantly to 2.09 g/kg.

After the trial, the amount of Alpha-cypermethrin in unwashed had already dropped significantly to 3.23 g/kg, compared to the amount that was observed before the trial, while the amount of Alpha-cypermethrin after 20 washes was 1.03 g/kg only (Table 2e). The wash resistance index for Alpha-cypermethrin was 95.5% and 94.4% before the hut trial and after the hut trial respectively while its retention was significantly lower, 39.9% and 31.8% (Table 2e), than that of YAHE® 4.0 LN.

Table 2a.

Mean concentration of Alpha-cypermethrin in YAHE® 4.0 LN.

Table 2a.

Mean concentration of Alpha-cypermethrin in YAHE® 4.0 LN.

| Active substance |

Net sample condition (*) |

Times washed |

Mean a.s. content (g/kg)

(n = 5) |

a.s. variation (RSD)

(n = 5) |

a.s. retention (relative to content before washing) |

Wash resistance

index (%) |

| Alpha-cypermethrin |

BHT |

0 wash |

8.70 |

4.4% |

|

|

| Whole net, 120 denier |

BHT |

20 washes |

8.25 |

1.9% |

94.9% |

99.7% |

| |

AHT |

0 wash |

8.33 |

1.9% |

|

|

| |

AHT |

20 washes |

7.75 |

1.1% |

93.0% |

99.6% |

Table 2b.

Mean concentration of Piperonyl butoxide in YAHE® 4.0 LN.

Table 2b.

Mean concentration of Piperonyl butoxide in YAHE® 4.0 LN.

| Synergist |

Net sample condition (*) |

Times washed |

Mean a.s. content (g/kg)

(n = 5) |

a.s. variation (RSD)

(n = 5) |

a.s. retention (relative to content before washing) |

Wash resistance

index (%) |

| Piperonyl butoxide |

BHT |

0 wash |

3.46 |

2.5% |

|

|

| Whole net, 120 denier |

BHT |

20 washes |

3.08 |

1.1% |

88.9% |

99.4% |

| |

AHT |

0 wash |

3.11 |

1.9% |

|

|

| |

AHT |

20 washes |

2.73 |

1.6% |

87.7% |

99.3% |

Table 2c.

Mean concentration of Alpha-cypermethrin in DuraNet® Plus LN.

Table 2c.

Mean concentration of Alpha-cypermethrin in DuraNet® Plus LN.

| Active substance |

Net sample condition (*) |

Times washed |

Mean a.s. content (g/kg)

(n = 5) |

a.s. variation (RSD)

(n = 5) |

a.s. retention (relative to content before washing) |

Wash resistance

index (%) |

| Alpha-cypermethrin |

BHT |

0 wash |

6.11 |

0.8% |

|

|

| Whole net, 150 denier |

BHT |

20 washes |

5.53 |

1.0% |

90.5% |

99.5% |

| |

AHT |

0 wash |

5.91 |

2.3% |

|

|

| |

AHT |

20 washes |

5.55 |

2.5% |

93.9% |

99.7% |

Table 2d.

Mean concentration of Piperonyl butoxide in DuraNet® Plus LN.

Table 2d.

Mean concentration of Piperonyl butoxide in DuraNet® Plus LN.

| Synergist |

Net sample condition (*) |

Times washed |

Mean a.s. content (g/kg)

(n = 5) |

a.s. variation (RSD)

(n = 5) |

a.s. retention (relative to content before washing) |

Wash resistance

index (%) |

| Piperonyl butoxide |

BHT |

0 wash |

1.86 |

4.5% |

|

|

| Whole net, 150 denier |

BHT |

20 washes |

1.66 |

3.0% |

89.2% |

99.4% |

| |

AHT |

0 wash |

1.71 |

4.6% |

|

|

| |

AHT |

20 washes |

1.61 |

3.5% |

93.9% |

99.7% |

Table 2e.

Mean concentration of Alpha-cypermethrin in Interceptor® LN.

Table 2e.

Mean concentration of Alpha-cypermethrin in Interceptor® LN.

4. Discussion

Pyrethroid–PBO LLINs are recommended for the control of pyrethroid-resistant mosquitoes because the addition of

Piperonyl Butoxide (PBO) to pyrethroid net imposes a blockade on metabolic resistance mechanisms in these mosquitoes, thereby partially restoring susceptibility to pyrethroid [

14,

22,

23]. Several experimental hut trials across Africa PBO LLINs have demonstrated PBO LLINs to be a strategy to overcome pyrethroid resistance especially in areas where resistance is driven by overexpression of P450 enzymes known to metabolize pyrethroids [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. The Olyset® Plus LLINs are the first-in-class (FIC) LLINs that received a World WHO policy recommendation [

28], following its demonstrated impact on malaria reduction in cluster randomized trials [

14,

15]. However, there is a need for more PBO nets on the market [

14], and other manufacturers of LLINs have produced pyrethroid–PBO nets that differ from Olyset® Plus in terms of design and specifications.

The present study was designed to investigate the efficacy of the YAHE 4.0 LLIN (alpha-cypermethrin & PBO treated LLIN), after twenty washes according to the WHO standardized washing procedure [

29]. The evaluation trial was conducted in an area dominated by

An. arabiensis [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. The assessment of the laboratory-based knockdown effect (using susceptible

An. gambiae s.s. Kisumu strain and

An.arabiensis-KBG strain) before washing, after 20 washes before and after hut trials has shown high knockdown induced by the YAHE 4.0. In general, the YAHE 4.0 LLINs have induced > 80% mortality in all test mosquitoes up to 20 washes, thus meeting WHO wash-fastness criteria for a LLIN.

The deterrence effect observed for the YAHE 4.0 LLIN unwashed (8.3%) was found to be lower than that of Veeralin unwashed, which induced a deterrence effect of 14.7%. Nevertheless, after 20 washes, the YAHE 4.0 LLIN induced a higher deterrence effect (12.8%) than that of Veeralin with 20 washes (2.7%). Veeralin is another alpha-cypermethrin & PBO LLIN that was recently evaluated in Tanzania [

37]. Elsewhere in Côte d’Ivoire, the deterrence effect of YAHE LLIN (unwashed) was 50.4% which decreased to 11.5% after 20 washes [

38]. Th e difference in the experimental hut deterrence from Côte d’Ivoire and Tanzania might be attributed mainly to the differences in hut designs.

All LLINs (unwashed and washed 20 times had similar exophily rates of about 80%. The pyrethroid nets with PBO (YAHE 4.0 and DuraNet Plus) and pyrethroid-only LLIN (Interceptor) induced higher exophily in this study than in a similar study conducted in Muheza, Tanga, where Veeralin washed 20 times had an exophily effect of 75.7% and unwashed had 70% exophily effect; PermaNet 3.0 unwashed induced exophily of 70%, and 64.3% for PermaNet 3.0 washed 20 times, while unwashed DuraNet had an exophily effect of 76.4% [

37]. In another study by Kweka et al. (2019) [

39], the exophily for DuraNet was 78.4%.

This is similar to the exophily of Interceptor LLIN in this study, with an exophily of 78.8%. However, for DuraNet, the alphacypermethrin is incorporated into the fibers, while for Interceptor LLIN, the alpha-cypermethrin is surface-coated.

In this study, YAHE 4.0 LLIN induced significant blood-feeding inhibition of 35.7% (unwashed) and 37.4% (20 washes). This was lower than that of Veeralin LLIN, 48.1% (unwashed) and 62.6% (20 washes). Such a difference could be due to the fact that the present study was conducted in an area where An.arabiensis is predominant, while Veeralin was tested against An. funestus. The two species differ in terms of behaviour.

The percentage mortality corrected for control was found to be less than 50% in all treatments, ranging from 36.8% to 47.9%. This is probably due to the fact that the

An.arabiensis in the study area is resistant to pyrethroids [

36,

37]. The YAHE 4.0 LLINs and DuraNet Plus are PBO LLINs, while the Interceptor LLIN is a non-PBO LLIN. Surprisingly, similar mortalities of pyrethroid-resistant

An. arabiensis were recorded by the PBO LLINs and the non-PBO net. Recently, significantly higher mortalities of pyrethroid-resistant An. funestus (s.l.) were recorded by the unwashed and 20 times washed Veeralin compared to DuraNet LLIN in the experimental hut, where the incorporation of PBO in Veeralin has shown increased mortality impact than in non-PBO DuraNet LLIN [

30]. Similar killing effect of WHO-approved standard PBO LLINs against pyrethroid-resistant mosquitoes has been recorded by Veeralin elsewhere in C^ote dʼIvoire [

40]. PBO is a chemical that inhibits mixed function oxidases that confer resistance to pyrethroids. The findings of this study imply that other metabolic enzymes may be responsible for the observed pyrethroid resistance, as previously reported by Matowo et al. (2010) [

34].

A candidate LLIN meets the WHO PQT phase II efficacy criteria if it performs as well as or better than the reference LLIN when washed 20 times in terms of blood-feeding inhibition and mortality. Results of the susceptibility tests have confirmed the high-level resistance to alpha-cypermethrin and cypermethrin insecticides in

An. arabiensis population in the study area. Previous studied in the same study area by Matowo et al. (2010, 2014) [

34,

35], reported resistance of the

An. arabiensis to other pyrethroids including permethrin, deltamethrin and lambda cyhalothrin but susceptible to pirimiphos-methyl (organophosphate). Similar to the previous studies, the

An. arabiensis remains susceptible to pirimiphs-methyl.

According to Matowo et al. (2010) [

30], pre-exposure of

An. arabiensis to PBO followed by exposure to diagnostic dose of permethrin in CDC bottle bioassays resulted in partial restoration of the susceptibility, implying involvement other resistance mechanism especially the β-esterases.

Based on the results of the chemical analysis, the amounts of Alpha-cypermethrin and PBO in the YAHE® 4.0 LN seem to be well above the declared amounts. However, these are equivalent to the amounts that were provided in the Certificate of Analysis (CoA). The declared (nominal) active ingredient and synergist content were 6.25 g/kg ±25% Alpha-cypermethrin and 2.2 g/kg±25% Piperonyl butoxide with 38 g/m² for the density. The results also show that amounts of Alpha-cypermethrin and PBO in the YAHE® 4.0 LN are much higher compared to the amounts of Alpha-cypermethrin and PBO in the active positive comparator, the DuraNet® Plus LN. However, the amount of Alpha-cypermethrin in the standard net, the Interceptor® LN, was even lower than that of DuraNet® Plus LN, and it decreased significantly with time and washing compared to the YAHE® 4.0and DuraNet® Plus LNs. This is probably due to the fact that the AIs in the two LNs are incorporated into polyethylene while the Alpha- cypermethrin is coated onto polyester of the Interceptor® LN.

5. Study Limitation

For the Standard Comparator we used Interceptor LLIN with surface-coated. alphacypermethrin because the standard LLINs with alphacypermethrin incorporated into the fibers such as DuraNet, Veeralin® LN, MAGNet LN, and MiraNet LN (which would match the test net and the active comparator) were not available.

6. Conclusions

The findings of this study have shown that blood-feeding rates recorded for 20 times washed YAHE 4.0 LLIN were statistically similar to those of the 20 times washed PQT-approved PBO/pyrethroid (DuraNet Plus) and a positive control in this trial. Also, the mortality induced by 20 times-washed YAHE 4.0 LLIN was statistically similar to that recorded for the 20 times-washed DuraNet Plus LLIN. In addition, the mortality and knockdown rates for the YAHE 4.0 LLIN against susceptible strains exceeded the WHO bio efficacy cut-offs of ≥ 80% mortality or ≥ 95% knockdown.

This provides evidence that YAHE 4.0 LLIN has met WHO PQT efficacy criteria for long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs). The amounts of Alpha-cypermethrin and PBO in the YAHE® 4.0 LN were higher than the declared (nominal) active ingredient and synergist (PBO) amounts. The amounts of Alpha- cypermethrin and PBO in the YAHE® 4.0 LN were higher than the declared (nominal) active ingredient and synergist (PBO) amounts. Based on the bio efficacy and wash resistance findings of the YAHE LLIN, we recommend YAHE 4.0 LLIN to be considered a suitable tool for protection against pyrethroid-resistant malaria vectors and should be added to the pool of PBO LLNs. However, further studies are needed to investigate the field durability of YAHE 4.0 in the community.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, J.M, N.J.M, S.A, R.K and F.M; Methodology, J.M, N.J.M, S.A, R.K, E.K, A.M, S.C, O.S, S.M, and F.E; Software, A.J and F.T; Validation, A.J, F.T and J.M; Formal Analysis, A.J, N.J.M, F.T, and J.M; Investigation, J.M, N.J.M, S.A, R.K and F.M; J. Resources, F.M; Data Curation, A.J, F.T, N.K and N.J.L; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, J.M and N.J.M; Writing – Review & Editing, S.A, R.K, B.M (Benson Mawa),G.S, and B.S; Visualization, N.J.M; Supervision, J.M, O.M, B.M (Baltazar Manunda), E.F; Project Administration, J.M. and N.J.M; Funding Acquisition, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fujian Yamei Industry &Trade Co. Ltd, Hongxing business building, No.56. Changle south road, Taijiang District, Fuzhou City, Fujian Province, China.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR) (NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol.IX/4835) on 13th February 2025.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Evod Tillya and Paul Anthony for washing the whole nets; the PAMVERC Insectary team including Hosian J Mo, Iptysam Ally, and Bakari Muhudhar who ensured the test systems were available on time; PAMVERC data clerks, Naomi Lyimo and Monica Joseph for entering the Project data. Our special thanks to Lilian Mollel, Fridah Temba and Mohamed Laizer for their financial management and administrative roles.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AOR |

Adjusted odds ratio |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| IRS |

Indoor residual spraying |

| ITNs |

Insecticide treated nets |

| LLINs |

Long-lasting insecticidal nets |

| NIM |

Non-inferiority margin |

| NIMR |

National Institute for Medical Research |

| PAMVERC |

Pan African Malaria Vector Research Consortium |

| PBO |

Piperonyl butoxide |

| RCTs |

Randomized control trials |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| WHOPES |

World Health Organization Pesticides Evaluation Scheme |

| WHOPQT |

World Health Organization Pre-qualification team |

References

- WHO. World Health Organization. World malaria report 2024: Addressing inequity in the global malaria response. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2024.

- WHO. World malaria World malaria report report 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization 2023. 283 p. Available from: https://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/%0Ahttps://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2023.

- Bhatt, S.; Weiss, D.J.; Cameron, E.; Bisanzio, D.; Mappin, B.; Dalrymple, U.; Battle, K.E.; Moyes, C.; Henry, A.; Eckhoff, P.A. et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature. 2015, 526, 207–11. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/nature15535.

- Hancock, P.A.; Hendriks, C.J.M.; Tangena, J.-A.; Gibson, H.; Hemingway, J.; Coleman, M.; Gething, P.W.; Cameron, E.; Bhatt, S.; Catherine, L.; Moyes, C.L. Mapping trends in insecticide resistance phenotypes in African malaria vectors. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matiya, D.J.; Philbert, A.B.; Kidima, W.; Matowo, J.J. Dynamics and monitoring of insecticide resistance in malaria vectors across mainland Tanzania from 1997 to 2017: a systematic review. Malar J. 2019, 18, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surendran, S.N.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Thiruchenthooran, V.; Santhirasegaram, S.; Sivabalakrishnan, K.; Raveendran, S.; Ramasamy, R. Anopheline bionomics, insecticide resistance and transnational dispersion in the context of controlling a possible recurrence of malaria transmission in Jaffna city in northern Sri Lanka. Parasit Vectors. 2020, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartilol, B.; Omedo, I.; Mbogo, C.; Mwangangi, J.; Rono, M.K. Bionomics and ecology of Anopheles merus along the East and southern Africa coast Parasit. Vectors. 2021, 14, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, D.D.; Zogo, B.; Hien, D.F.d.; Hien, A.S.; Kabore, D.A.; Kientega, M.; Ouédraogo, A.G.; Pennetier, C.; Koffi, A.A.; Moiroux, N.; et al. Insecticide resistance status of malaria vectors Anopheles gambiae (s.l.) of southwest Burkina Faso and residual efficacy of indoor residual spraying with microencapsulated pirimiphos-methyl insecticide. Parasit Vectors. 2021, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosha, J.F.; Kulkarni, M.A.; Lukole, E.; Matowo, N.S.; Pitt, C.; Messenger, L.; Mallya, E.; Jumanne, M.; Aziz, T.; Kaaya, R.; et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness against malaria of three types of dual-active-ingredient long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) compared with pyrethroid-only LLINs in Tanzania: a four-arm, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2022, 399, 1227–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovi, A.; Adoha, C.J.; Yovogan, B.; Cross, C.L.; Dee, D.P.; Konkon, A.K.; Sidick, A.; Accrombessi, M.; Ahouandjinou, M.J.; Osse, R.; et al. The effect of next-generation, dual-active-ingredient, long-lasting insecticidal net deployment on insecticide resistance in malaria vectors in Benin: results of a 3-year, three-arm, cluster-randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2024, 8, e894–e905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, G.; Strode, C.; Tran, L.; Khoa, P.T.; Jamet, H.P. Can piperonyl butoxide enhance the efficacy of pyrethroids against pyrethroid-resistant Aedes aegypti? Trop Med Int Health. 2011, 16, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleave, K.; Lissenden, N.; Chaplin, M.; Choi, L.; Ranson, H. Piperonyl butoxide (PBO) combined with pyrethroids in insecticide- treated nets to prevent malaria in Africa. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschmidt, I.; Rowland, M. Insecticides and malaria. In: Koenraadt, C.J.M.; Spitzen, J.; Takken, W. editors. Innovative strategies for vector control- Ecology and control of vector-borne diseases [Internet]. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers; 2021, p. 17–32. Available from: https://www.wageningenacademic.com/doi/10.3920/978-90-8686-895-7_2.

- Protopopoff, N.; Mosha, J.F.; Lukole, E.; Charlwood, J.D.; Wright, A.; Mwalimu, C.D.; Manjurano, A.; Mosha, F.W; Kisinza, W.; Kleinschmidt, I.; et al. Effectiveness of a long-lasting piperonyl butoxide-treated insecticidal net and indoor residual spray interventions, separately and together, against malaria transmitted by pyrethroid-resistant mosquitoes:a cluster, randomised controlled, two-by-two factorial design trial. Lancet. 2018, 391, 1577–88. [Google Scholar]

- Staedke, S.G.; Gonahasa, S.; Dorsey, G.; Kamya, M.R.; Maiteki-Sebuguzi, C.; Lynd, A.; Katureebe, A.; Kyohere, M.; Mutungi, P.; Kigozi, S.P.; et al. Effect of long-lasting insecticidal nets with and without piperonylbutoxide on malaria indicators in Uganda (LLINEUP): a pragmatic, cluster-randomised trial embedded in a national LLIN distribution campaign. Lancet 2020, 395, 1292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Prequalified vector control products. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2025. Available at https://extranet.who.int/prequal/vector-control-products/prequalified-product-list (Accessed on 2025 August 31).

- Oxborough, R. M.; Chilito, K. L. F.; Tokponnon, F.; Messenger, L.A. Malaria vector control in sub-Saharan Africa: complex trade-offs to combat the growing threat of insecticide resistance. The Lancet Planetary Health 2024, 8, e804–e812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbewe, N.J.; Azizi, S.; Rowland, M.W.; Kirby, M.J.; Ezekia, K.; Manunda, B.; Shayo, M.F.; Portwood, N.M.; Mosha, F.W.; Matowo, J. Assessments of Anopheles arabiensis behaviour around bed nets using partial adhesive treatments. Sci. Rep., 2025, 15, 20966 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Conditions for Deployment of Mosquito Nets Treated With a Pyrethroid and Piperonyl Butoxide Geneva: World Health Organization Global Malaria Program. 2017.

- WHO. Test procedures for insecticide resistance monitoring in malaria vector mosquitoes. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2016. https://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241511575/en/ [Google Scholar.

- WHO. Technical consultation to assess comparative efficacy of vector control products: meeting report, 5 and 9 June 2023. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2023 (http://iris.who.int/handle/10665/372841, accessed 10 October 2023).

- Matowo, J.; Weetman, D.; Pignatelli, P.; Wright, A.; Charlwood, J.D.; Kaaya, R.; Shirima, B.; Moshi, O.; Lukole, E.; Mosha, J.; et al. Expression of pyrethroid metabolizing P450 enzymes characterizes highly resistant Anopheles vector species targeted by successful deployment of PBO-treated bednets in Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2022, 17, e0249440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- N'Guessan, R.; Asidi, A.; Boko, P.; Odjo, A.; Akogbeto, M.; Pigeon, O.; Rowland, M. An experimental hut evaluation of PermaNet(®) 3.0, a deltamethrin-piperonyl butoxide combination net, against pyrethroid-resistant Anopheles gambiae and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes in southern Benin. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.2010, 104, 758-65. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.08.008. Epub 2010 Oct 16. PMID: 20956008.

- Tungu, P.; Magesa, S.; Maxwell, C.; Malima, R.; Masue, D.; Sudi, W.; Myamba, J.; Pigeon, O.; Rowland, M. Evaluation of PermaNet 3.0 a deltamethrin-PBO combination net against Anopheles gambiae and pyrethroid resistant Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes: an experimental hut trial in Tanzania. Malar J. 2010, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Koudou, B.G.; Koffi, A.A.; Malone, D.; Hemingway, J. Efficacy of PermaNet® 2.0 and PermaNet® 3.0 against insecticide-resistant Anopheles gambiae in experimental huts in Côte d’Ivoire. Malar J. 2011, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennetier, C.; Bouraima, A.; Chandre, F.; Piameu, M.; Etang, J.; Rossignol, M.; Sidick, I.; Zogo, B.; Lacroix, M.-N.; Yadav, R.; et al. Efficacy of Olyset® Plus, a new long-lating insecticidal net incorporating permethrin and piperonyl-butoxide against multi-resistant malaria vectors. PLoS ONE. 2023, 8, e75134. [Google Scholar]

- Toe, K.H.; Müller, P.; Badolo, A.; Traore, A.; Sagnon, N.; Dabiré, R.K.; Ranson, H. Do bednets including piperonyl butoxide offer additional protection against populations of Anopheles gambiae s.l. that are highly resistant to pyrethroids? An experimental hut evaluation in Burkina Fasov. Med Vet Entomol. 2018, 32, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Conditions for Deployment of Mosquito Nets Treated With a Pyrethroid and Piperonyl Butoxide Geneva: World Health Organisation Global Malaria Program,.2017.

- WHO. Guidelines for laboratory and field-testing of long-lasting insecticidal nets. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2013.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/80270 [Google Scholar].

- Matowo, J.; Kulkarni, MA.; Mosha, F.W.; Oxborough, R.M.; Kitau, J.; Tenu, F.; Rowland, M. Biochemical basis of permethrin resistance in Anopheles arabiensis from Lower Moshi, north-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2010, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matowo, J.; Kitau, J.; Kabula, B.; Kavishe, R.A.; Oxborough, R.M.; Kaaya, R.; Francis, P.; Chambo, A.; Mosha, F.W.; Rowland, M. Dynamics of insecticide resistance and the frequency of kdr mutation in the primary malaria vector Anopheles arabiensis in rural villages of Lower Moshi, North Eastern Tanzania. J Parasitol and Vector BioloL. 2014, 6, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Oxborough, R.; Kiau, J.; Re Jones, R.; Feston, E.; Matowo, J.; Mosha F.W.; Rowland M. Long-Lasting Control of Anopheles arabiensis by a Single Spray Application of Microencapsulated Pirimiphos-methyl (Actellic(R) 300 CS) Mala J. 2014, 13, 37.

- Kitau J, Oxborough R, Kaye A, Chen-Hussey V, Isaacs E, Matowo J, Magesa SM, Mosha F, Rowland M and Logan J. Long-lasting insecticide treated blanket for protection against Anopheles arabiensis and Culex quinquefasciatus: an experimental hut evaluation in Tanzania Parasit Vectors 2014, 7, 129.

- Mosha, F.W.; Lyimo, I.N.; Oxborough, R.M.; Malima, R.; Tenu, F.; Matowo, J.; Feston, E.; Mndeme, R.; Magesa, S.M.; Rowland, M. Experimental evaluation of the pyrolle insecticide chlorfenapyr on bed nets for the control of Anopheles arabiensis and Culex quinquefasciatus. Trop Med & Inter Health. 2008, 13, 644–652. [Google Scholar]

- Mosha, F.W.; Lyimo, I.N.; Oxborough, R.M.; Matowo, J.; Malima, R.; Feston, E.; Mndeme, R.; Tenu, F.; Kulkarni, M.; Maxwell, C.A.; Magesa, S.M.; Rowland, M.W. Comparative efficacies of permethrin-, deltamethrin- and alpha-cypermethrin-treated nets, against Anopheles arabiensis and Culex quinquefasciatus in northern Tanzania. Ann Trop Med &Parasitol. 2008, 102, 367–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mahande, A.M.; Msangi, S.; Lyaruu, L.J.; Kweka, E.J. Bio-efficacy of DuraNet® long-lasting insecticidal nets against wild populations of Anopheles arabiensis in experimental huts. Trop. Med. Health. 2028, 46, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungu, P.K.; Waweru, J.; Karthi, S.; Wangai, J.; Kweka, E.J. Field evaluation of Veeralin, an alpha-cypermethrin + PBO long-lasting insecticidal net, against natural populations of Anopheles funestus in experimental huts in Muheza, Tanzania. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis. 2021, 1, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegban, C.M.Y.; Camara, S.; Koffi, A.A.; Ahoua Alou, L.P.; Kouame, J.K.; Koffi, A.F.; Kouassi, P.K.; Moiroux, N. Evaluation of Yahe® and Panda® 2.0 long-lasting insecticidal nets against wild pyrethroid-resistant Anopheles gambiae s.l. from Côte d’Ivoire: an experimental hut trial. Parasit Vectors. 2021, 14, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweka, E.J.; Tungu, P.K.; Mahande, A.M.; Mazigo, H.D.; Sayumwe, S.; Msangi, S.; Lyaruu.; Waweru, J.; Kisinza, W.; Wangai, J. Bio-efficacy and wash resistance of MAGNet long-lasting insecticidal net against wild populations of Anopheles funestus in experimental huts in Muheza, Tanzania. Malar J. 2019, 18, 335. [CrossRef]

- Oumbouke, W.A.; Rowland, M.; Koffi, A.A.; Alou, L.A.; Camara, S.; NʼGuessan, R. Evaluation of an alpha-cypermethrin plus PBO mixture long-lasting insecticidal net VEERALIN® LN against pyrethroid resistant Anopheles gambiae s.s.: an experimental hut trial in M’be, central C^ote dʼIvoire. Parasit. Vectors. 2019, 12, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Summary of net samples that were used for chemical analysis.

Table 1.

Summary of net samples that were used for chemical analysis.

| LN type |

LN status |

No. of pieces to cut |

No. pieces to test in Cones |

No. of pieces for chemical analysis |

Total pieces for chemical analysis/ LN type |

| DuraNet Plus |

Before washing* |

5 |

5 |

5 |

20 |

| After 20 washes– before hut trial* |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| After hut trial - Olyset® Plus unwashed |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| After hut trial - Olyset® Plus washed 20X |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Interceptor® LN |

Before washing* |

5 |

5 |

5 |

20 |

| After 20 washes– before hut trial* |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| After hut trial - Interceptor® unwashed |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| After hut trial - Interceptor® washed 20X |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| YAHE 4.0 |

Before washing* |

5 |

5 |

5 |

20 |

| After 20 washes– before hut trial* |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| After hut trial – YAHE 4.0 unwashed |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| After hut trial – YAHE 4.0 washed 20X |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| |

|

|

|

Total |

60 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).