1. Introduction

Myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) is the most common cardiac disease in domestic dogs. The disease is characterized by slow progressive degenerative valvular changes, resulting in mitral valve prolapse and regurgitation. Subsequently, left atrial and ventricular dilatation might develop [

1]. In some affected dogs, long-standing left-sided volume overload will ultimately progress to congestive heart failure [

2]. Although the process of the disease has been well described, the underlying causes and mechanisms involved in the development and progression remain incompletely understood.

The Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (CKCS) is reported to be one of the most heavily bottlenecked domestic dog breeds, presumably because of multiple decades of closed population breeding and a small founder population [

3]. As a result, CKCSs carry up to 13% more derived alleles than other dog breeds [

3]. This is believed to contribute to high-risk states for certain diseases, including MMVD [

4]. Murmur probability and severity, which indicate disease progression, have been suggested to be heritable in the CKCS [

4,

5]. Pedigree analysis suggests a polygenic inheritance [

5].

Genetic variation in allele frequencies between several breeds has been demonstrated using whole genome sequencing data [

3]. In CKCSs, a higher frequency was found of ten allele variants, of which six variants were located within the heart-specific Nebulette (NEBL) gene. It was demonstrated that several of the NEBL variants had regulatory potential in heart-derived cell lines and were associated with reduced NEBL isoform nebulette expression in papillary muscle. Additionally, this study found that the genotype for one of the NEBL risk variants (NEBL3) was a significant predictor of graded MMVD disease status in the Dachshund.

Although these allele variants seemed fixed in the CKCS, wild-type (healthy) alleles at NEBL have likewise been demonstrated. A separate research group looked at risk variants in a large group of Australian CKCSs with different stages of MMVD [

6]. The homozygous NEBL1-3 variants were associated with more severe cardiac dilatation, compared to the heterozygous genotypes. This finding suggests that dogs that carry the NEBL1-3 wildtype have less severe disease. In this study, the prevalence of the heterozygous genotype was low (3.4%).

Breeding restrictions have been shown to decrease the prevalence of MMVD [

7,

8], therefore, breeding programs require or advise yearly auscultation or echocardiography for screening of heart murmurs in CKCSs. In the Netherlands, for example, yearly auscultation is obligatory to obtain a registration number. Dogs that develop a murmur before 5 years of age are excluded from breeding in the Netherlands, with the intention of increasing the age of disease onset.

Identification of breed-specific genetic mutations can alter breeding and screening recommendations for CKCSs. It could help to develop more effectively targeted screening and risk stratification. Understanding the frequency of these NEBL variants allows for more informed breeding practices to potentially reduce the severity of MMVD while maintaining genetic variability. The frequency of the wild-type allele in the asymptomatic breeding population is, however, unknown. On one hand, severity of MMVD in the registered CKCS breed population could be reduced by selective breeding with dogs that carry the wild-type allele. On the other hand, if the wild-type frequency in the breeding population is very low and the NEBL variant is proven as causative for MMVD risk and/or severity, cross-breeding would likely be required to breed out severe MMVD in the CKCS.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the wild-type allele frequency through prospective genetic testing in a large sample of CKCS that were intended for breeding.

2. Animals, Materials and Methods

2.1. Blood Sampling

Blood samples were prospectively obtained from healthy CKCSs of the Dutch and the Australian breeding population that were presented by the breeder for auscultation. Irrespective of the auscultation status, blood was collected in all dogs, and DNA was extracted for genotyping of the NEBL risk alleles. Sampling and screening were performed by an ECVIM-cardiology Diplomate, under ethical approval by the Dutch “Instantie voor Dierenwelzijn Utrecht” (protocol number 16205-1-04) or the approval of the University of Sydney Animal Ethics Committee (approval numbers 2015/902 and 2018/1449). Each sample consisted of 1 to 2 ml whole blood in EDTA tubes and was stored at -18°C.

2.2. DNA Extraction

For the Dutch samples, an automated extraction system (MagCore®) was used for extracting total DNA from whole blood samples. DNA quality was assessed with a NanoDrop® spectrophotometer.

For the Australian samples, 15 - 40 µL of thawed whole blood was incubated with 45 µL QuickExtract TM at 65 °C for 15 minutes then 98 °C for 5 minutes, and diluted with water to a volume of 450 µL. Samples were centrifuged at high speed (approximately 15,000 g) for one minute to pellet the cell fragments and PCR was carried out using the supernatant.

2.3. Genetic Testing

For the Dutch samples, the primers for the Nebulette variants NEBL1, NEBL2, and NEBL3 were extrapolated from previous research [

6] and are shown in

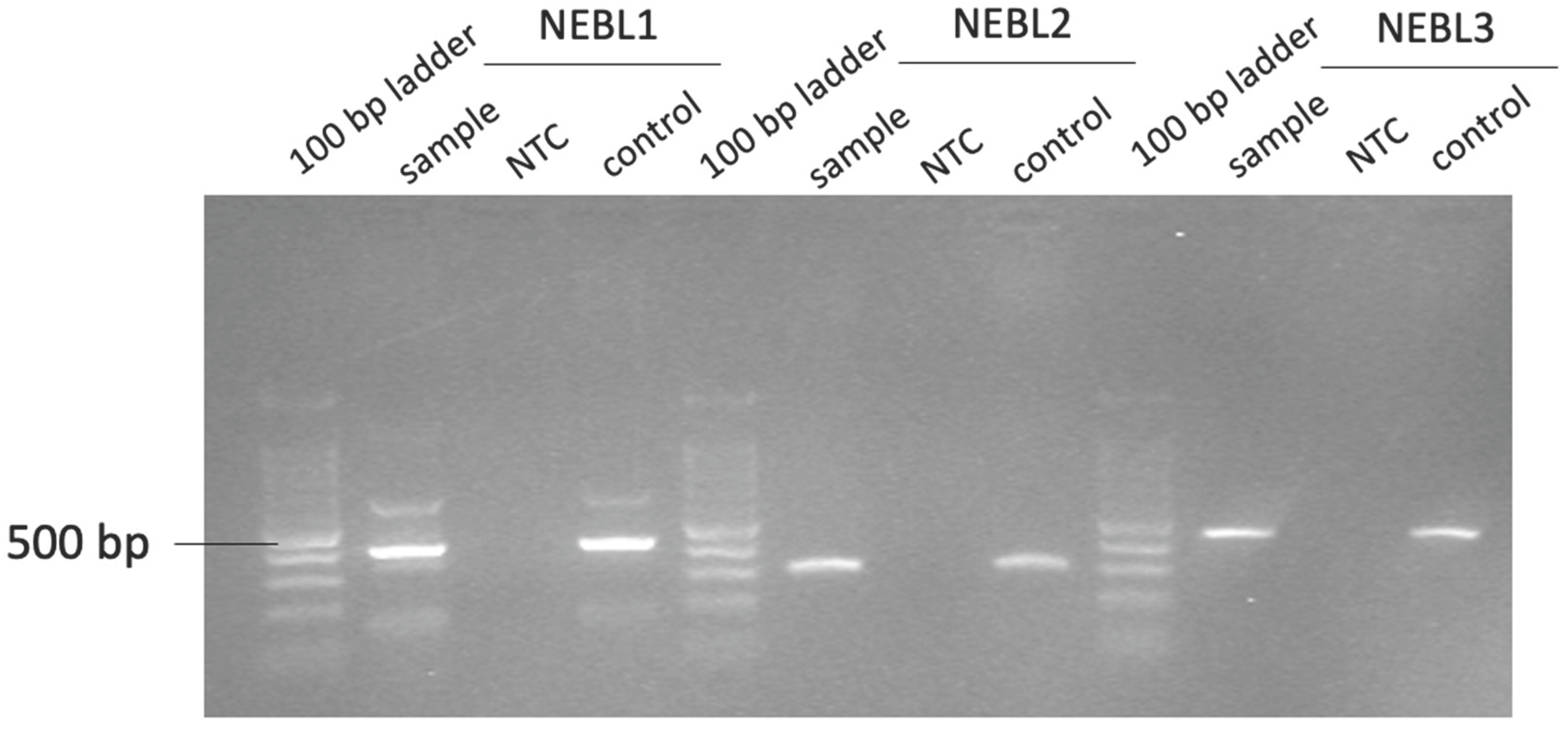

Table 1. For each Nebulette variant a mastermix, using Platinum Taq polymerase, was made with the respective primers. Twenty-five ng/µl of the extracted DNA was added to the mix. A no template control (NTC) was added as a negative control, and a known sample was used as a positive control. The PCR program consisted of: 5 min of denaturation at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of amplification for 30s at 95°C, 30s at 57°C (annealing temperature), and 30s at 72°C, followed by elongation for 10 min at 72°C. The PCR product was checked for contamination using agarose gel electrophoresis.

The PCR products were purified (to remove leftover primers) by adding 2U/µl exonuclease I and incubated at 37°C for 45 min followed by deactivation of the enzyme by incubating at 75°C for 15 min. Next, a BigDye sequencing reaction was performed by using 1.5 µL BigDye Terminator 5X Sequencing buffer, 0.8 µL BigDye™ Terminator v3.1 Ready Reaction Mix, 4.7 µL of MilliQ, 2 µL of purified PCR-product, and 3.2 pmol of NEBL1 reverse primer and a NEBL2 and 3 forward primer. The PCR program consisted of: 5 min of denaturation at 96°C, followed by 35 cycles of amplification for 30s at 95°C, 15s at 55°C, and 30s at 60°C. This was followed by a purification step to remove unincorporated nucleotides using a gel filtration medium (Sephadex G-50). Sanger DNA sequencing was performed using the ABI 3500XL Genetic Analyzer. Data were analyzed using Lasergene Seqman Pro software.

For the Australian samples, analysis was performed after the results of the Dutch samples were known. Since functionally significant variants of NEBL1-3 are in perfect LD based on earlier research [

6], as confirmed by the results from the Dutch samples, only the NEBL3 variant was analyzed. A PCR was performed with 7 µL supernatant combined with 7 µL primer mixture and 11 µL EconoTaq PLUS GREEN 2X master mix, and 32 cycles of competitive endpoint PCR were carried out with an annealing temperature of 52°C. All animals were tested anonymously in location-randomised duplicate, and in all cases, there was agreement between the genotype indicated by the two duplicates.

The primer mixture (

Table 2) consisted of three primers, including a common reverse primer and two allele-specific forward primers. An extra “tail” was added to one of the allele-specific primers to create a larger fragment which in turn facilitated discriminating between the two alleles either by gel electrophoresis or mass spectrometry. The SNP being tested for, was the final base on the 3’ end of the two forward primers. An additional mismatch to the genomic sequence was added within the 5 bases at the 3’ end of the primer. The deliberate inclusion of a mismatch in this manner greatly increases the specificity of each allele-specific primer and allows them to be tested in a competitive manner in a single PCR reaction. The fragment lengths in this assay were 74bp/94bp.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with commercially available software (Microsoft® Excel). Normality was visually assessed using a Q-Q plot and histogram. Results are reported as median values with interquartile ranges (IQRs). Correlation between cohort type and genotype was analyzed with a Chi-square test.

3. Results

3.1. Dutch Cohort

A total of 175 samples of CKCS with an unknown genetic status owned by 38 different breeders were included. The majority was female (36 male / 140 female). The median age was 4 years with an interquartile age range between 2–6 years. A left apical systolic murmur indicative of MMVD was identified in 24 dogs (murmur prevalence 13.7%). A total of 174 dogs were found to be homozygous for the NEBL1-3 risk allele. Only one individual was heterozygous for NEBL1-3, this was an 8-year-old female CKCS without a murmur. The heterozygosity prevalence in the Dutch breeding population was therefore 0.57%. No dog was homozygous for the wild-type variant. This resulted in a NEBL1-3 risk variant allele frequency of 99.7%.

Figure 1.

Gel electrophoresis with a 1.5% agarose gel and a 100 base pair ladder, under an ultraviolet light transilluminator (gel doc). Fragment NELB1 is ±417 base pairs long, NEBL2 is ±277 base pairs long, and NEBL3 is ±429 base pairs long. NEBL, nebulette; NTC, negative control; control, positive control.

Figure 1.

Gel electrophoresis with a 1.5% agarose gel and a 100 base pair ladder, under an ultraviolet light transilluminator (gel doc). Fragment NELB1 is ±417 base pairs long, NEBL2 is ±277 base pairs long, and NEBL3 is ±429 base pairs long. NEBL, nebulette; NTC, negative control; control, positive control.

3.2. Australian Cohort

A total of 196 samples of CKCS with an unknown genetic status owned by 66 different breeders were analyzed. One sample was excluded after DNA testing due to suspected contamination. Their age distribution was similar to the Dutch cohort, with a median of 4 years and an interquartile age range between 2–6 years. The majority was female (56 male/ 139 female). A left apical systolic murmur indicative of MMVD was identified in 57 dogs (murmur prevalence 29.2%). Of those 195 dogs, 9 were heterozygous for the NEBL3 risk allele. The heterozygosity prevalence in the Australian breeding population was therefore 4.6%. No dogs were homozygous for the wild type variant. The NEBL3 risk variant allele frequency of the Australian cohort was 97.7%.

The NEBL wild type variant allele frequency of the Australian breeding population was higher compared to the frequency in the Dutch population (p value 0.0088). Likewise, the prevalence of heterozygous dogs in the Australian breeding population was higher compared to the prevalence in the Dutch breeding population (p value 0.017).

4. Discussion

Although small differences exist between different breeding populations, this study shows a high NEBL risk variant allele frequency and homozygosity in CKCS breeding dogs in both the Netherlands and Australia. This is not surprising given the international character of dog breeding and since dog breeds are created by a small number of founders combined with closed studbooks [

9]. When a population size decreases for one or more generations, this is called a genetic “bottleneck”. From this small founder group, a new population is created that possesses reduced genetic variation with different allele frequencies compared to the ancestral population [

10]. Deleterious recessive alleles will not show in heterozygous animals (the so-called masked load), but selection in small populations will increase homozygosity, which leads to more expression of deleterious recessive alleles. The masked load becomes a “realized load” with expression of diseases [

11]. Therefore, dogs generally carry more deleterious alleles in a homozygous state than wolves [

12].

Formation of the CKCS breed has been linked to significant allele frequency shifts [

3],

with a percentage of inbreeding that has been estimated at about 40% [

9,

13]. The CKCS breed has been revived in the United Kingdom in the 1920’s with the aim of recreating the dogs shown in the paintings of King Charles II. Many CKCS kennel clubs and books refer to Roswell Eldridge who held a competition in 1926, looking for dogs as shown in the pictures of King Charles II [

14]. Few dogs were selected to fit the standard. Details on the original gene pool and evidence on how the breed was recreated are lacking. In 1928 several breeders created the first CKCS kennel club in the United Kingdom. Descendants of these dogs spread through the world, forming the breeding populations in both the Netherlands and Australia, which are likely to have the same genetic characteristics.

Nebulette is a cytoskeletal structural protein found only in cardiac myocytes at the Z-discs of the thin filaments [

15]. Decreased expression has been shown to disrupt the stability and shortening of the actin thin filament, while also decreasing the cardiac beating frequencies [

16]. The NEBL risk variants are associated with decreased nebulette expression in the papillary muscle, suggesting that the papillary muscle function has an important role in development and/or progression of the disease [

3]. Weakening of the papillary muscle could lead to mitral valve prolapse during systole, which is an important finding in MMVD.

The results of our study agree with the previous findings that heterozygous NEBL1-3 genotypes are rare [

3,

6]. These dogs still develop MMVD, yet with less severe heart enlargement. It seems likely that there are other contributing genetic factors, as previous research has also suggested that it is a polygenic disease [

5]. To better understand the genetic cause of this disease, further research is required. In this context, a recent study identified nine candidate genes that are associated with longevity in CKCS dogs, the NEBL gene not being one of them [

17]. A variant in COL19A1 was found, which encodes for a protein involved in cartilage strength and function. Collagen has been shown to play a crucial role in the development of MMVD. The health status of these dogs was not evaluated, so they did not compare dogs with MMVD with those without.

This study has several limitations. First, the NEBL risk variant allele frequency in breeding CKCS from only the Netherlands and Australia was investigated. Although unlikely given the common ancestry and international character of dog breeding, it is possible that in other countries or regions the prevalence of the wildtype NEBL variants is higher. Second, analysis was performed using genetic variants at the NEBL locus. A causative mutation in the NEBL gene has not been identified yet, which should be a more tightly correlated marker.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, although small differences between countries exist, this study shows a high NEBL risk allele frequency and homozygosity in CKCS breeding dogs. Therefore, selective breeding for the wild-type NEBL allele status alone in this population is impossible as it will result in the formation of a severe genetic bottleneck, i.e. a focus on selecting of this variant alone may increase the incidence of other health problems in the breed. Selection of breeding CKCS on wildtype NEBL variants should not be used on its own due to the low prevalence in this breed and due to the polygenic character of the disease.

Funding

This study was supported by the European College of Veterinary Internal Medicine - Companion Animals (ECVIM-CA) Purina Institute Resident Research Award (PUR2023-08).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the breeders who volunteered their pets for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose. Parts of this study will be presented as an oral abstract at the 2025 ECVIM-CA Congress.

Ethics Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the Animal Welfare Body of Utrecht University (registered protocol number 16205-1-04) as well as the University of Sydney Animal Ethics Committee (Approval numbers: 2015/902 and 2018/1449). Informed client consent was obtained from all pet owners.

References

- Fox, P.R. Pathology of myxomatous mitral valve disease in the dog. J. Vet. Cardiol. 2012, 14, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgarelli, M.; Savarino, P.; Crosara, S.; Santilli, R.A.; Chiavegato, D.; Poggi, M.; Bellino, C.; La Rosa, G.; Zanatta, R.; Haggstrom, J.; Tarducci, A. Survival characteristics and prognostic variables of dogs with mitral regurgitation attributable to myxomatous valve disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2008, 22, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelsson, E.; Ljungvall, I.; Bhoumik, P.; Conn, L.B.; Muren, E.; Ohlsson, Å.; Olsen, L.H.; Engdahl, K.; Hagman, R.; Hanson, J.; Kryvokhyzha, D.; Pettersson, M.; Grenet, O.; Moggs, J.; Del Rio-Espinola, A.; Epe, C.; Taillon, B.; Tawari, N.; Mane, S.; Hawkins, T.; Hedhammar, Å.; Gruet, P.; Häggström, J.; Lindblad-Toh, K. The genetic consequences of dog breed formation-Accumulation of deleterious genetic variation and fixation of mutations associated with myxomatous mitral valve disease in cavalier King Charles spaniels. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, T.; Swift, S.; Woolliams, J.A.; Blott, S. Heritability of premature mitral valve disease in Cavalier King Charles spaniels. Vet. J. 2011, 188, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swenson, L.; Häggström, J.; Kvart, C.; Juneja, R.K. Relationship between parental cardiac status in Cavalier King Charles spaniels and prevalence and severity of chronic valvular disease in offspring. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1996, 208, 2009–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, S.E.; Beijerink, N.J.; O’Brien, M.; Wade, C.M. Genetic Variants at the Nebulette Locus Are Associated with Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease Severity in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. Genes 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkegård, A.C.; Reimann, M.J.; Martinussen, T.; Häggström, J.; Pedersen, H.D.; Olsen, L.H. Breeding Restrictions Decrease the Prevalence of Myxomatous Mitral Valve Disease in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels over an 8- to 10-Year Period. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2016, 30, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, S.; Baldin, A.; Cripps, P. Degenerative Valvular Disease in the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel: Results of the UK Breed Scheme 1991-2010. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2017, 31, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannasch, D.; Famula, T.; Donner, J.; Anderson, H.; Honkanen, L.; Batcher, K.; Safra, N.; Thomasy, S.; Rebhun, R. The effect of inbreeding, body size and morphology on health in dog breeds. Canine Med. Genet. 2021, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templeton, A.R. The reality and importance of founder speciation in evolution. Bioessays 2008, 30, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dussex, N.; Morales, H.E.; Grossen, C.; Dalén, L.; van Oosterhout, C. Purging and accumulation of genetic load in conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2023, 38, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsden, C.D.; Ortega-Del Vecchyo, D.; O’Brien, D.P.; Taylor, J.F.; Ramirez, O.; Vilà, C.; Marques-Bonet, T.; Schnabel, R.D.; Wayne, R.K.; Lohmueller, K.E. Bottlenecks and selective sweeps during domestication have increased deleterious genetic variation in dogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016, 113, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreger, D.L.; Rimbault, M.; Davis, B.W.; Bhatnagar, A.; Parker, H.G.; Ostrander, E.A. Whole-genome sequence, SNP chips and pedigree structure: building demographic profiles in domestic dog breeds to optimize genetic-trait mapping. Dis. Model. Mech. 2016, 9, 1445–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coile, D.C. Cavalier King Charles Spaniel (Complete Pet Owner’s Manuals); B.E.S. Publishing: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 1998; p. 120. ISBN 0764102273. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, M. Katz, M.D. Physiology of the Heart, 5th ed.; LWW: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010; p. 576. ISBN 978-1-60831-171-2. [Google Scholar]

- Moncman, C.L.; Wang, K. Targeted disruption of nebulette protein expression alters cardiac myofibril assembly and function. Exp. Cell Res. 2002, 273, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korec, E.; Ungrová, L.; Kalvas, J.; Hejnar, J. Identification of genes associated with longevity in dogs: 9 candidate genes described in Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. Veterinary and Animal Science 2025, 27, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Sequences for primers used in PCR for the samples collected and analysed in the Netherlands.

Table 1.

Sequences for primers used in PCR for the samples collected and analysed in the Netherlands.

| Primer |

Sequence 5’-3’ |

| NEBL1_Forward |

5’- GGAAGCAGGCTCAGACTCTC -3’ |

| NEBL1_Reverse |

5’- AACCTGACCAGTCCTTGGTG -3’ |

| NEBL2_Forward |

5’- GCAGAAGGGCAACACTCTCT -3’ |

| NEBL2_Reverse |

5’- TCTCTTTCTTTTGCCGCCCT -3’ |

| NEBL3_Forward |

5’- AGCCCTCCTTCTGTGCTTTA -3’ |

| NEBL3_Reverse |

5’- CTCCAAGGAGCCATCACATT -3’ |

Table 2.

Sequences for primers used in PCR for the samples collected and analyzed in Australia.

Table 2.

Sequences for primers used in PCR for the samples collected and analyzed in Australia.

| Primer |

Sequence 5’-3’ |

| NEBL3_Forward (wildtype allele) |

5’-CAGCAGACCCCAGCAGAGCG-3' |

| NEBL3_Forward (risk allele) |

5’-AACTGATAGATCGGAATGGTCAGCAGACCCCAGCAGAATA-3' |

| NEBL3_Reverse |

5’-TACAGAGTTTCAGTCCTGCCAAA-3' |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).