Submitted:

06 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

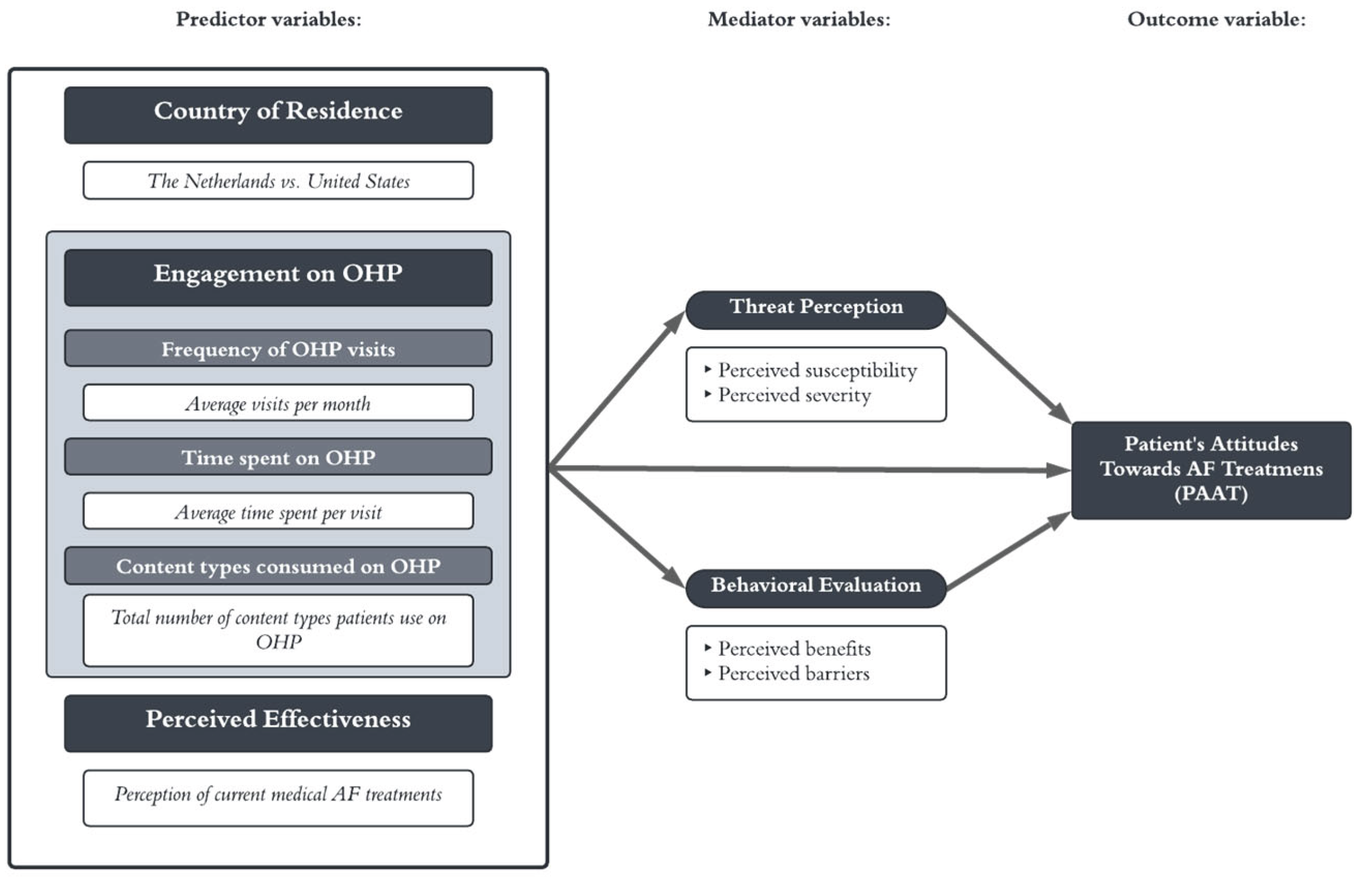

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Patient Attitudes toward AF Treatment

2.1.2 Health Belief Model

2.1.3. Treat Perception: Perceived Susceptibility

2.1.4. Threat perception: perceived severity

2.1.5. Behavioral evaluation: perceived benefits

2.1.6. Behavioral Evaluation: Perceived Barriers

2.1.7. Engagement with OHPs

2.1.8. Perceived effectiveness

| H1: |

|

| H2: |

|

| H3: |

|

| H4: |

|

| H5: |

|

| H6: |

|

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Sample size

2.2.2. Data collection

2.2.3. Analysis

2.2.4. Variables

3. Results

3.1. Data descriptives

3.2. Assumptions

3.3. Coefficients and Correlations

3.4. Structural Model

| Indirect through threat perception | Indirect through behavioral evaluation | Total indirect effect on patient attitudes towards AF treatments | ||||||||

| SD | SD | SD | Sig. | |||||||

| Content types consumed | .00864 | .010 | .377 | -.003823 | .006 | .160 | .004815 | .010 | .466 | No |

| Perceived Effectiveness | .00813 | .006 | .166 | -.029070 | .021 | .120 | -.020942 | .023 | .372 | No |

| Country of Residence | .17663 | .032 | <.001 | -.082527 | .030 | .006 | .094103 | .037 | .010 | Yes |

| Visits on OHP | .01778 | .009 | .055 | .011016 | .008 | .184 | .028796 | .010 | .006 | Yes |

| Time spent on OHP | .04191 | .015 | .005 | .011016 | .018 | .117 | .052926 | .018 | .004 | Yes |

| Total through M1 | .253 | .047 | <.000 | Yes | ||||||

| Total through M2 | -.093* | .029 | .001 | Yes | ||||||

| Total indirect effect on Y | .160* | .051 | .002 | Yes | ||||||

|

*. Correlation is significant at 0.05 level (two-tailed)123456 **. Correlation is significant at 0.01 level (two-tailed)123456 a. p > 0.05 | ||||||||||

| HYPOTHESES | RESULTS | |

| 1 | Higher perceived threat perception will result in a more positive PAAT. | Accepted |

| 2 | Higher perceived behavioral evaluation will result in a more positive PAAT. | Rejected |

| 3 | More frequent visits on the OHP will positively increase PAAT through both mediators perceived threat and perceived behavioral evaluation. | Accepted |

| 4 | Longer sessions on the OHP will positively increase PAAT through both mediators perceived threat perception and perceived behavioral evaluation. | Accepted |

| 5 | More content types consumed on the OHP will positively increase PAAT through both mediators perceived threat perception and perceived behavioral evaluation. | Rejected |

| 6 | Hhigher perceived effectiveness will positively increase PAAT through primarily perceived threat perception. | Rejected |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| HBM | Health Belief Model |

| PAAT | Patient attitudes toward AF treatments |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

References

- Brundel, B.J.J.M.; Ai, X.; Hills, M.T.; Kuipers, M.F.; Lip, G.Y.H.; de Groot, N.M.S. Atrial Fibrillation. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2022, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheen, M.H.H.; Tan, Y.Z.; Oh, L.F.; Wee, H.L.; Thumboo, J. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Primary Medication Non-Adherence in Chronic Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Clin Pract 2019, 73, e13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, C.; Qin, Y.; Cai, H.; Chen, B.; Cao, J. Factors Influencing Medication Knowledge and Beliefs on Warfarin Adherence among Patients with Atrial Fibrillation in China. Patient Preference and Adherence 2017, 11, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Heart Association Medication Adherence: Taking Your Meds as Directed Available online:. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/consumer-healthcare/medication-information/medication-adherence-taking-your-meds-as-directed (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Cutler, D.M. The Good and Bad News of Health Care Employment. JAMA 2018, 319, 758–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, E. Applying the Health Belief Model to Medication Adherence: The Role of Online Health Communities and Peer Reviews. Journal of Health Communication 2018, 23, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborn, C.Y.; Mayberry, L.S.; Wallston, K.A.; Johnson, K.B.; Elasy, T.A. Understanding Patient Portal Use: Implications for Medication Management. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2013, 15, e2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, A.; Qin, L.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, F.; Huang, P.; Xie, W. The Effect of Online Health Information Seeking on Physician-Patient Relationships: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2022, 24, e23354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aref-Adib, G.; O’Hanlon, P.; Fullarton, K.; Morant, N.; Sommerlad, A.; Johnson, S.; Osborn, D. A Qualitative Study of Online Mental Health Information Seeking Behaviour by Those with Psychosis. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanzi, T.M. Public Perceptions Towards Online Health Information: A Mixed-Method Study in Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. J Healthc Leadersh 2023, 15, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potpara, T.S.; Mihajlovic, M.; Zec, N.; Marinkovic, M.; Kovacevic, V.; Simic, J.; Kocijancic, A.; Vajagic, L.; Jotic, A.; Mujovic, N.; et al. Self-Reported Treatment Burden in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: Quantification, Major Determinants, and Implications for Integrated Holistic Management of the Arrhythmia. Europace 2020, 22, 1788–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihajlovic, M.; Simic, J.; Marinkovic, M.; Kovacevic, V.; Kocijancic, A.; Mujovic, N.; Potpara, T.S. Sex-Related Differences in Self-Reported Treatment Burden in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.-Q.; Chen, Y.; Dabbs, A.D.; Wu, Y. The Effectiveness of Smartphone App–Based Interventions for Assisting Smoking Cessation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2023, 25, e43242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zheng, B.; Fan, F.; Yi, T.; Zheng, Y.; He, P.; Fang, J.; Jia, J.; Zhu, Q.; et al. Effects on Adherence to a Mobile App-Based Self-Management Digital Therapeutics Among Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e32251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Kwan, Y.H.; Yap, W.L.; Lim, Z.Y.; Phang, J.K.; Loo, Y.X.; Aw, J.; Low, L.L. Factors Influencing Medication Adherence in Multi-Ethnic Asian Patients with Chronic Diseases in Singapore: A Qualitative Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, A.N.L.; Gawalko, M.; Dohmen, L.; van der Velden, R.M.J.; Betz, K.; Duncker, D.; Verhaert, D.V.M.; Heidbuchel, H.; Svennberg, E.; Neubeck, L.; et al. Mobile Health Solutions for Atrial Fibrillation Detection and Management: A Systematic Review. Clin Res Cardiol 2022, 111, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, P.; Horsley, L.; Metz, B. The Emerging World of Online Health Communities (SSIR) Available online:. Available online: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_emerging_world_of_online_health_communities (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Tonko, J.B.; Wright, M.J. Review of the 2020 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation—What Has Changed and How Does This Affect Daily Practice. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2021, 10, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, R.W.; Wolfe, M.S. Chapter 5 - Structure and Organization of the Pre-Travel Consultation and General Advice for Travelers. In Travel Medicine (Second Edition); Keystone, J.S., Kozarsky, P.E., Freedman, D.O., Nothdurft, H.D., Connor, B.A., Eds.; Mosby: Edinburgh, 2008; ISBN 978-0-323-03453-1. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz, K. CHAPTER 6 - Current Theoretical Bases for Nutrition Intervention and Their Uses. In Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease; Coulston, A.M., Rock, C.L., Monsen, E.R., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2001; ISBN 978-0-12-193155-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Education Monographs 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Education Quarterly 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhr, D. The Basics of Structural Equation Modeling.

- Frymier, A.B.; Nadler, M.K. Persuasion : Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice; 4th ed. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haddock, G.; Thorne, S.; Wolf, L.J. Attitudes and Behavior. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology; 2020 ISBN 978-0-19-023655-7.

- Zolnoori, M.; Fung, K.W.; Fontelo, P.; Kharrazi, H.; Faiola, A.; Wu, Y.S.S.; Stoffel, V.; Patrick, T. Identifying the Underlying Factors Associated With Patients’ Attitudes Toward Antidepressants: Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Patient Drug Reviews. JMIR Mental Health 2018, 5, e10726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, G.Y.H.; Keshishian, A.; Li, X.; Hamilton, M.; Masseria, C.; Gupta, K.; Luo, X.; Mardekian, J.; Friend, K.; Nadkarni, A.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Oral Anticoagulants Among Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Patients. Stroke 2018, 49, 2933–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, W.Y.; Fresco, P. Medication Adherence Measures: An Overview. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015, 217047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitolins, M.Z.; Rand, C.S.; Rapp, S.R.; Ribisl, P.M.; Sevick, M.A. Measuring Adherence to Behavioral and Medical Interventions. Controlled Clinical Trials 2000, 21, S188–S194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, S.E.; Mollborn, S. Social Determinants and Health Behaviors: Conceptual Frames and Empirical Advances. Current Opinion in Psychology 2015, 5, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, C.J. A Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Health Belief Model Variables in Predicting Behavior. Health Communication 2010, 25, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karl, J.A.; Fischer, R.; Druică, E.; Musso, F.; Stan, A. Testing the Effectiveness of the Health Belief Model in Predicting Preventive Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of Romania and Italy. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faculty of Business and Management, UCSI University Sarawak Campus, Malaysia; Hiew, L. -C.; Lee, A.H.; Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism Management, UCSI University Sarawak Campus, Malaysia; Leong, C.-M.; UCSI Graduate Business School, UCSI University, Kuala Lumpur Campus, Malaysia; Liew, C.-Y.; Faculty of Business and Management, UCSI University, Kuala Lumpur Campus, Malaysia; Soe, M.-H.; Malaysian Medical Association (MMA), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Do They Really Intend to Adopt E-Wallet? Prevalence Estimates for Government Support and Perceived Susceptibility. AJBR 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Ragazzoni, L.; Hubloue, I.; Barone-Adesi, F.; Valente, M. The Use of the Health Belief Model in the Context of Heatwaves Research: A Rapid Review. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2024, 18, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarinci, I.C.; Bandura, L.; Hidalgo, B.; Cherrington, A. Development of a Theory-Based (PEN-3 and Health Belief Model), Culturally Relevant Intervention on Cervical Cancer Prevention Among Latina Immigrants Using Intervention Mapping. Health Promotion Practice 2012, 13, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulos, D.N.K.; Hassan, A.M. Using the Health Belief Model to Assess COVID-19 Perceptions and Behaviours among a Group of Egyptian Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wei, L.; Liu, Z. Promoting COVID-19 Vaccination Using the Health Belief Model: Does Information Acquisition from Divergent Sources Make a Difference? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, Y.B.; Gautam, R.K. How Well the Constructs of Health Belief Model Predict Vaccination Intention: A Systematic Review on COVID-19 Primary Series and Booster Vaccines. Vaccines 2023, 11, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaMorte, W.W. Online MPH and Teaching Public Health | SPH Available online:. Available online: https://www.bu.edu/sph/online-mph-and-teaching-public-health/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Cho, M.-K.; Cho, Y.-H. Role of Perception, Health Beliefs, and Health Knowledge in Intentions to Receive Health Checkups among Young Adults in Korea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani-Dehbalaei, M.; Loripoor, M.; Nasirzadeh, M. The Role of Health Beliefs and Health Literacy in Women’s Health Promoting Behaviours Based on the Health Belief Model: A Descriptive Study. BMC Women’s Health 2021, 21, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Z.; Sun, X. Associations between Media Use, Self-Efficacy, and Health Literacy among Chinese Rural and Urban Elderly: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, A.; Abraham, C. Can the Effectiveness of Health Promotion Campaigns Be Improved Using Self-Efficacy and Self-Affirmation Interventions? An Analysis of Sun Protection Messages. Psychol Health 2011, 26, 799–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, L.J.; Prioreschi, A.; Bosire, E.; Cohen, E.; Draper, C.E.; Lye, S.J.; Norris, S.A. Environmental, Social, and Structural Constraints for Health Behavior: Perceptions of Young Urban Black Women During the Preconception Period-A Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative. J Nutr Educ Behav 2019, 51, 946–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andajani-Sutjahjo, S.; Ball, K.; Warren, N.; Inglis, V.; Crawford, D. Perceived Personal, Social and Environmental Barriers to Weight Maintenance among Young Women: A Community Survey. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2004, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Analysis of the Impact of Health Beliefs and Resource Factors on Preventive Behaviors against the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; van Heerde, H.J.; Moreau, C.P.; Palmatier, R.W. Marketing in the Health Care Sector: Disrupted Exchanges and New Research Directions. Journal of Marketing 2024, 88, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, T.; Larson, E.; Schnall, R. Unraveling the Meaning of Patient Engagement: A Concept Analysis. Patient Education and Counseling 2017, 100, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korda, H.; Itani, Z. Harnessing Social Media for Health Promotion and Behavior Change. Health Promotion Practice 2013, 14, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Fan, S.; Zhao, J.L. Community Engagement and Online Word of Mouth: An Empirical Investigation. Information & Management 2018, 55, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Health Behavior and Health Education : Theory, Research, and Practice; 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2008; ISBN 978-0-7879-9614-7.

- Rajpura, J.; Nayak, R. Medication Adherence in a Sample of Elderly Suffering from Hypertension: Evaluating the Influence of Illness Perceptions, Treatment Beliefs, and Illness Burden. JMCP 2014, 20, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrystyn, H.; Small, M.; Milligan, G.; Higgins, V.; Gil, E.G.; Estruch, J. Impact of Patients’ Satisfaction with Their Inhalers on Treatment Compliance and Health Status in COPD. Respiratory Medicine 2014, 108, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, J.; Fonseca, L.M. How Sample Size Influences Research Outcomes. Dental Press J. Orthod. 2014, 19, 27–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques; Wiley series in probability and mathematical statistics; 3. ed. Wiley: New York, NY, 1977; ISBN 978-0-471-16240-7. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, G.M.; Tomei, P.A.; Serra, B.; Mello, S. Differences in the Use of 5- or 7-Point Likert Scale: An Application in Food Safety Culture. Organizational Cultures: An International Journal 2021, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yao, T.; Wang, Y. Patient Engagement as Contributors in Online Health Communities: The Mediation of Peer Involvement and Moderation of Community Status. Behavioral Sciences 2023, 13, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Zhang, X.; Liu, L.; Ren, C. Converting Readers to Patients? From Free to Paid Knowledge-Sharing in Online Health Communities. Information Processing & Management 2021, 58, 102490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kim, H.J. Antecedents and Consequences of Information Overload in the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibanguay, N.; Chaiamnuay, S.; Asavatanabodee, P.; Narongroeknawin, P. Effect of Patient Education on Medication Adherence of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PPA 2019, 13, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Horne, R.; Hankins, M.; Chisari, C. The Medication Adherence Report Scale: A Measurement Tool for Eliciting Patients’ Reports of Nonadherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2020, 86, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitu, K.; Adugna, A.; Kassie, A.; Handebo, S. Application of Health Belief Model for the Assessment of COVID-19 Preventive Behavior and Its Determinants among Students: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0263568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebarajakirthy, C.; Das, M.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Ahmadi, H. Communication Strategies: Encouraging Healthy Diets for on-the-Go Consumption. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2022, 40, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. Understanding Online Health Community Users’ Information Adoption Intention: An Elaboration Likelihood Model Perspective. Online Information Review 2021, 46, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welton-Mitchell, C.; Dally, M.; Dickinson, K.L.; Morris-Neuberger, L.; Roberts, J.D.; Blanch-Hartigan, D. Influence of Mental Health on Information Seeking, Risk Perception and Mask Wearing Self-Efficacy during the Early Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Longitudinal Panel Study across 6 U.S. States. BMC Psychology 2023, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.D.-C.; Lui, J.N.-M. Factors Influencing Risk Perception during Public Health Emergencies of International Concern (PHEIC): A Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Yin, J.; Song, Y. An Exploration of Rumor Combating Behavior on Social Media in the Context of Social Crises. Computers in Human Behavior 2016, 58, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Schoen, C.; Schoenbaum, S.C.; Doty, M.M.; Holmgren, A.L.; Kriss, J.L.; Shea, K.K. MIRROR, MIRROR ON THE WALL: AN INTERNATIONAL UPDATE ON THE COMPARATIVE PERFORMANCE OF AMERICAN HEALTH CARE.

- Thompson, G.A.; Segura, J.; Cruz, D.; Arnita, C.; Whiffen, L.H. Cultural Differences in Patients’ Preferences for Paternalism: Comparing Mexican and American Patients’ Preferences for and Experiences with Physician Paternalism and Patient Autonomy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 10663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.M.; Scott Morton, F. Hospitals, Market Share, and Consolidation. JAMA 2013, 310, 1964–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, M.F.; Konus, U.; Brundel, B.J.J.M.; İlker Birbil, Ş. Communication Strategies Driving Online Health Community Patient Awareness and Engagement Investigated within Atrial Fibrillation Context. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayn, M.-G.; des Garets, V.; Rivière, A. Collective Empowerment of an Online Patient Community: Conceptualizing Process Dynamics Using a Multi-Method Qualitative Approach. BMC Health Services Research 2021, 21, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pick, C.M. OPEN Fundamental Social Motives Data Descriptor Measured across Forty-Two Cultures in Two Waves. Scientific Data.

| M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

| Threat Perception | 5.6797 | .9711 | (.709) | |||||||

| Behavioral Evaluation | 5.4174 | 1.065 | .242** | (.764) | ||||||

| Country of Residence | .5008 | .50042 | .407** | .304** | − | |||||

| Content types consumed (count) | 1.8509 | 1.0144 | .162** | -.001a | .114** | − | ||||

| Visits of OHP | 1.8183 | 1.1078 | .210** | .006a | .278** | .394** | − | |||

| Time spent on OHP | 1.64 | .732 | .182** | -.025a | .098* | .409** | .146** | − | ||

| Perceived Effectiveness | 5.38 | 1.841 | .129** | .377** | .213** | .028a | .022a | .001** | − | |

| Patients’ Attitudes | 4.3693 | 1.0470 | .390** | .009a | .344** | .390** | .438** | .284** | .165** | (.925) |

| Cronbach’s alphas are shown in the diagonals.123456 *. Correlation is significant at 0.05 level (two-tailed)123456 **. Correlation is significant at 0.01 level (two-tailed)123456 a. p > 0.05 | ||||||||||

| Path 1 (a1) | Path 2 (a2) | Path 3 (b1b2c’) | ||||||||

| Threat perception | Behavioral Evaluation | PAAT | ||||||||

| (SD) | (SD) | (SD) | ||||||||

| Constant | 4.664* | 31.775 | <.000 | 4.326* | 27.775 | <.000 | 2.070* | 7.449 | <.000 | |

| (.147) | − | − | (.156) | − | − | (.278) | − | − | ||

| Content on OHP | .034a | .802 | .442 | .025a | .555 | .579 | .197* | 4.955 | <.000 | |

| (.042) | − | − | (.045) | − | − | (.040) | − | − | ||

| Perceived Effectiveness | .0320a | 1.597 | .110 | .190* | 8.926 | <.000 | .083* | 4.124 | <.000 | |

| (.02) | − | − | (.021) | − | − | (.020) | − | − | ||

| Country of Residence | .695* | 8.972 | <.000 | .539* | 6.563 | <.000 | .340* | 4.234 | <.000 | |

| (.077) | − | − | (.082) | − | − | (.080) | − | − | ||

| Visits on OHP | .070a | 1.910 | .056 | -.072a | -1.834 | .067 | .239* | 6.839 | <.000 | |

| (.037) | − | − | (.039) | − | − | (.035) | − | − | ||

| Time spent on OHP | .165* | 3.025 | .002 | -.072a | -1.243 | .214 | .154* | 2.976 | <.000 | |

| (.054) | − | − | (.058) | − | − | (.052) | − | − | ||

| Threat Perception (M1) | .254* | 6.525 | <.000 | |||||||

| (.039) | − | − | ||||||||

| Behavioral Evaluation (M2) | -.153* | -4.159 | <.003 | |||||||

| (.037) | − | − | ||||||||

|

*. p < .05 a. p > .05 |

||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).