Submitted:

01 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

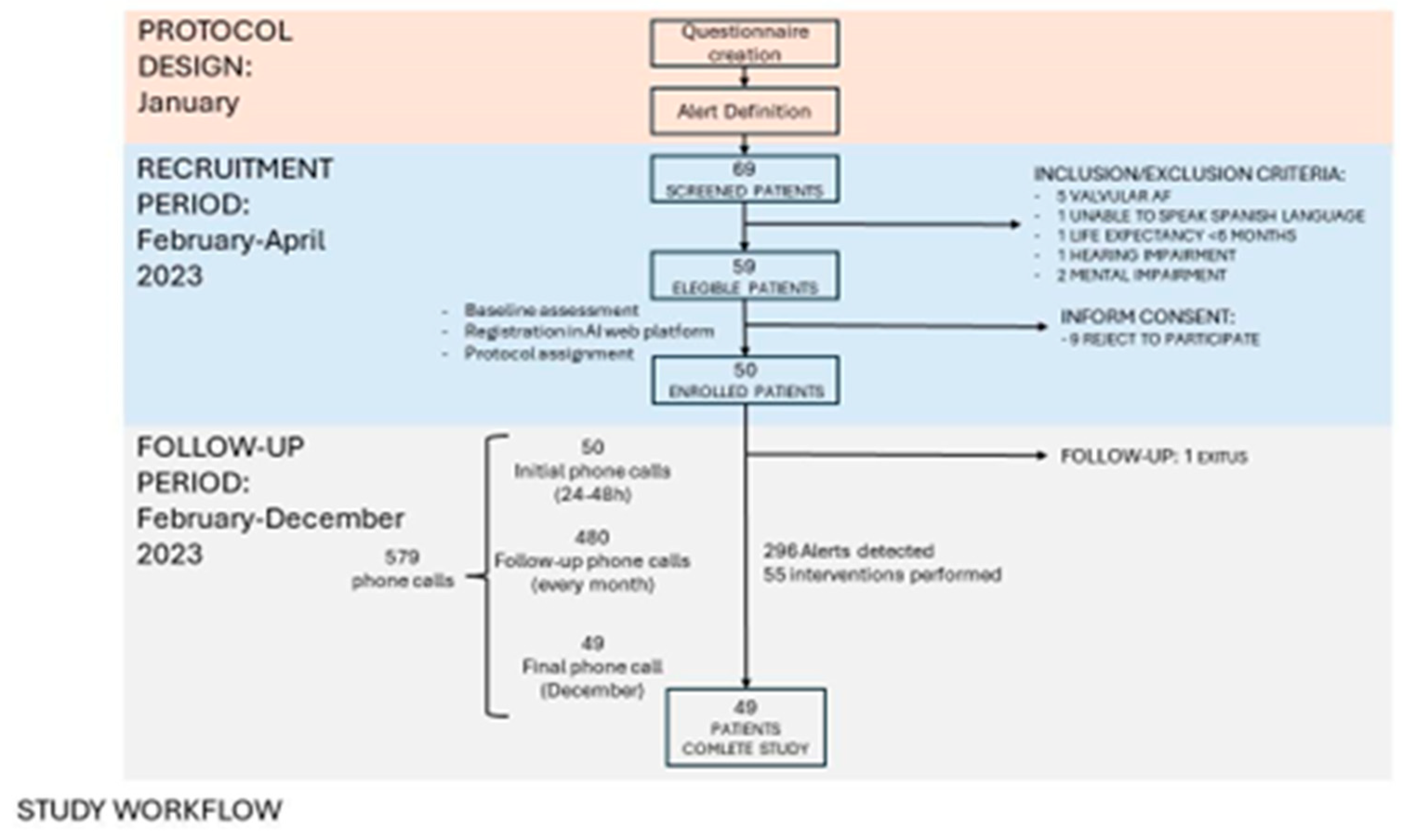

Material and Methods

Study Design and Population

Statistical Methods

Results

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F, Cervellin G. Global epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: An increasing epidemic and public health challenge. Int J Stroke Off J Int Stroke Soc. 2021 Feb;16(2):217–21.

- Krijthe BP, Kunst A, Benjamin EJ, Lip GYH, Franco OH, Hofman A, et al. Projections on the number of individuals with atrial fibrillation in the European Union, from 2000 to 2060. Eur Heart J. 2013 Sep 14;34(35):2746–51.

- Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association [Internet]. [cited 2024 Apr 17]. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659.

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Marin F, Camm AJ, Lip GYH. Stroke and Thromboembolism in Atrial Fibrillation: – Systematic Review of Stroke Risk Factors and Risk Stratification Schema –. Circ J. 2012;76(10):2289–304.

- Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jun 19;146(12):857–67.

- Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2021 Feb 1;42(5):373–498.

- Andrade JG, Aguilar M, Atzema C, Bell A, Cairns JA, Cheung CC, et al. The 2020 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society Comprehensive Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Can J Cardiol. 2020 Dec;36(12):1847–948.

- Lip GYH, Freedman B, De Caterina R, Potpara TS. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: Past, present and future: Comparing the guidelines and practical decision-making. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(07):1230–9.

- Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman EB, Deenadayalu N, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. The Lancet. 2014 Mar 15;383(9921):955–62.

- Steffel J, Verhamme P, Potpara TS, Albaladejo P, Antz M, Desteghe L, et al. The 2018 European Heart Rhythm Association Practical Guide on the use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2018 Apr 21;39(16):1330–93.

- Kotecha D, Chua WWL, Fabritz L, Hendriks J, Casadei B, Schotten U, et al. European Society of Cardiology smartphone and tablet applications for patients with atrial fibrillation and their health care providers. Eur Eur Pacing Arrhythm Card Electrophysiol J Work Groups Card Pacing Arrhythm Card Cell Electrophysiol Eur Soc Cardiol. 2018 Feb 1;20(2):225–33.

- Brieger D, Amerena J, Attia J, Bajorek B, Chan KH, Connell C, et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia and the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand: Australian Clinical Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation 2018. Heart Lung Circ. 2018 Oct 1;27(10):1209–66.

- Lowres N, Neubeck L, Salkeld G, Krass I, McLachlan AJ, Redfern J, et al. Feasibility and cost-effectiveness of stroke prevention through community screening for atrial fibrillation using iPhone ECG in pharmacies. The SEARCH-AF study. Thromb Haemost. 2014 Jun;111(6):1167–76.

- Hickey KT, Hauser NR, Valente LE, Riga TC, Frulla AP, Masterson Creber R, et al. A single-center randomised, controlled trial investigating the efficacy of a mHealth ECG technology intervention to improve the detection of atrial fibrillation: the iHEART study protocol. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016 Jul 16;16:152.

- Haberman ZC, Jahn RT, Bose R, Tun H, Shinbane JS, Doshi RN, et al. Wireless Smartphone ECG Enables Large-Scale Screening in Diverse Populations. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015 May;26(5):520–6.

- Lowres N, Mulcahy G, Gallagher R, Ben Freedman S, Marshman D, Kirkness A, et al. Self-monitoring for atrial fibrillation recurrence in the discharge period post-cardiac surgery using an iPhone electrocardiogram. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg Off J Eur Assoc Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2016 Jul;50(1):44–51.

- Ricci RP, Morichelli L, Santini M. Remote control of implanted devices through Home Monitoring technology improves detection and clinical management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Eur Pacing Arrhythm Card Electrophysiol J Work Groups Card Pacing Arrhythm Card Cell Electrophysiol Eur Soc Cardiol. 2009 Jan;11(1):54–61.

- Bajorek B, Magin P, Hilmer S, Krass I. A cluster-randomised controlled trial of a computerised antithrombotic risk assessment tool to optimise stroke prevention in general practice: a study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014 Feb 7;14:55.

- Wang Y, Bajorek B. Safe use of antithrombotics for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: consideration of risk assessment tools to support decision-making. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2014 Feb;5(1):21–37.

- Eckman MH, Wise RE, Naylor K, Arduser L, Lip GYH, Kissela B, et al. Developing an Atrial Fibrillation Guideline Support Tool (AFGuST) for shared decision making. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015 Apr;31(4):603–14.

- Guo Y, Chen Y, Lane DA, Liu L, Wang Y, Lip GYH. Mobile Health Technology for Atrial Fibrillation Management Integrating Decision Support, Education, and Patient Involvement: mAF App Trial. Am J Med. 2017 Dec 1;130(12):1388-1396.e6.

- Bubner TK, Laurence CO, Gialamas A, Yelland LN, Ryan P, Willson KJ, et al. Effectiveness of point-of-care testing for therapeutic control of chronic conditions: results from the PoCT in General Practice Trial. Med J Aust. 2009 Jun 1;190(11):624–6.

- Bereznicki LRE, Jackson SL, Peterson GM. Supervised patient self-testing of warfarin therapy using an online system. J Med Internet Res. 2013 Jul 12;15(7):e138.

- Stafford L, Peterson GM, Bereznicki LR, Jackson SL, Tienen EC van, Angley MT, et al. Clinical Outcomes of a Collaborative, Home-Based Postdischarge Warfarin Management Service. Ann Pharmacother. 2011 Mar 1;45(3):325–34.

- Toscos T, Coupe A, Wagner S, Ahmed R, Roebuck A, Flanagan M, et al. Engaging Patients in Atrial Fibrillation Management via Digital Health Technology: The Impact of Tailored Messaging. J Innov Card Rhythm Manag. 2020 Aug 1;11(8):4209–17.

- Desteghe L, Klutz K, Vijgen J, Koopman P, Dilling-Boer D, Schurmans J, et al. The Health Buddies App as a Novel Tool to Improve Adherence and Knowledge in Atrial Fibrillation Patients: A Pilot Study. JMIR MHealth UHealth. 2017 Jul 19;5(7):e7420.

- Klimis H, Thakkar J, Chow CK. Breaking Barriers: Mobile Health Interventions for Cardiovascular Disease. Can J Cardiol. 2018 Jul 1;34(7):905–13.

- Piette JD, List J, Rana GK, Townsend W, Striplin D, Heisler M. Mobile Health Devices as Tools for Worldwide Cardiovascular Risk Reduction and Disease Management. Circulation. 2015 Nov 24;132(21):2012–27.

- Pfaeffli Dale L, Dobson R, Whittaker R, Maddison R. The effectiveness of mobile-health behaviour change interventions for cardiovascular disease self-management: A systematic review. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016 May;23(8):801–17.

- Gandhi S, Chen S, Hong L, Sun K, Gong E, Li C, et al. Effect of Mobile Health Interventions on the Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. 2017 Feb;33(2):219–31.

- Cevasco KE, Morrison Brown RE, Woldeselassie R, Kaplan S. Patient Engagement with Conversational Agents in Health Applications 2016-2022: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Syst. 2024 Apr 10;48(1):40. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Posadzki P, Mastellos N, Ryan R, Gunn LH, Felix LM, Pappas Y, et al. Automated telephone communication systems for preventive healthcare and management of long-term conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Dec 14;2016(12):CD009921.

- Kassavou A, Sutton S. Automated telecommunication interventions to promote adherence to cardio-metabolic medications: meta-analysis of effectiveness and meta-regression of behaviour change techniques. Health Psychol Rev. 2018 Jan 2;12(1):25–42.

- Tsoli S, Sutton S, Kassavou A. Interactive voice response interventions targeting behaviour change: a systematic literature review with meta-analysis and meta-regression. BMJ Open. 2018 Feb 1;8(2):e018974.

- Tudor Car L, Dhinagaran D, Kyaw B, Kowatsch T, Joty S, Theng Y, Atun R. Conversational Agents in Health Care: Scoping Review and Conceptual Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(8):e17158. [CrossRef]

- . Milne-Ives M, de Cock C, Lim E, Shehadeh M, de Pennington N, Mole G, Normando E, Meinert E. The Effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence Conversational Agents in Health Care: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(10):e20346. [CrossRef]

- de Cock C, Milne-Ives M, van Velthoven MH, Alturkistani A, Lam C, Meinert E. Effectiveness of Conversational Agents (Virtual Assistants) in Health Care: Protocol for a Systematic Review. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020 Mar 9;9(3):e16934. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- McTear, M. F. (2002). Spoken dialogue technology: Enabling the conversational user interface. ACM Computing Surveys, 34(1), 90–169. [CrossRef]

- Lobo, Joana; Ferreira, Liliana; Ferreira, Aníbal JS (2017). CARMIE. International Journal of E-Health and Medical Communications, 8(4), 21–37. [CrossRef]

- A. Cheng, V. Raghavaraju, J. Kanugo, Y. P. Handrianto and Y. Shang, "Development and evaluation of a healthy coping voice interface application using the Google home for elderly patients with type 2 diabetes," 2018 15th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2018, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- García Bermúdez I, González Manso M, Sánchez Sánchez E, Rodríguez Hita A, Rubio Rubio M, Suárez Fernández C. Utilidad y aceptación del seguimiento telefónico de un asistente virtual a pacientes COVID-19 tras el alta [Usefulness and acceptance of telephone monitoring by a virtual assistant for patients with COVID-19 following discharge]. Rev Clin Esp. 2021 Oct;221(8):464-467. Spanish. Epub 2021 Feb 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dorado-Díaz PI, Sampedro-Gómez J, Vicente-Palacios V, Sánchez PL. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Cardiology. The Future is Already Here. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2019 Dec;72(12):1065-1075. Epub 2019 Oct 12 . [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni P, Mahadevappa M, Chilakamarri S. The Emergence of Artificial Intelligence in Cardiology: Current and Future Applications. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2022;18(3):e191121198124. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ledziński Ł, Grześk G. Artificial Intelligence Technologies in Cardiology. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2023 May 6;10(5):202. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pegoraro V, Bidoli C, Dal Mas F, et al. Cardiology in a Digital Age: Opportunities and Challenges for e-Health: A Literature Review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(13):4278. Published 2023 Jun 26. [CrossRef]

- Santamaria A, Antón Maldonado C, Sánchez-Quiñones B, Ibarra Vega N, Ayo González M, Gonzalez Cabezas P, Carrasco Moreno R. Implementing Telemedicine in Clinical Practice in the First Digital Hematology Unit: Feasibility Study. JMIR Form Res. 2023 Dec 4;7:e48987. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barrios V, Cinza-Sanjurjo S, García-Alegría J, Freixa-Pamias R, Llordachs-Marques F, Molina CA, Santamaría A, Vivas D, Suárez Fernandez C. Role of telemedicine in the management of oral anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation: a practical clinical approach. Future Cardiol. 2022 Sep;18(9):743-754. Epub 2022 Jul 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- aquero A. Net Promoter Score (NPS) and Customer Satisfaction: Relationship and Efficient Management. Sustainability. 2022; 14(4):2011. [CrossRef]

- Rotella P and Chulani, S. "Analysis of customer satisfaction survey data," 2012 9th IEEE Working Conference on Mining Software Repositories (MSR), Zurich, Switzerland, 2012, pp. 88-97. [CrossRef]

- Fatima B, Mohan A, Altaie I, Abughosh S. Predictors of adherence to direct oral anticoagulants after cardiovascular or bleeding events in Medicare Advantage Plan enrollers with atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2024 May;30(5):408-419. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Demographics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age (mean, range ) |

AVKs (n=16) | DOACs (n=33) | Total (n=49) | |||

| Male n=12 |

Female n=4 |

Male n=29 |

Female n=11 |

Male n=33 |

Female n=16 |

|

| Type of DOAC (n=33) | ||||||

| Edoxaban (n, %) | 7 (21%) | |||||

| Rivaroxaban (n, %) | 11 (33%) | |||||

| Apixaban (n, %) | 12 (36%) | |||||

| Dabigatran (n, %) | 3 (9%) | |||||

| OAT Adherence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication doses missed | AVKs (n =16) | DOACs (n=33) | Total (n=49) | |

| 0 | 10 (63%) | 18 (55%) | 28 (58%) | |

| 1 | 4 (25%) | 5 (15%) | 9 (18%) | |

| 2 | 1(6%) | 7 (21%) | 8 (16%) | |

| ≥3 | 1(6%) | 3 (9%) | 4 (8%) | |

| Health Events | Concordance (n, %) | |||

| ≥1 Bleeding event | 14 (88%) | 5(15%) | 19(39%) | 19 (100%) |

| Bridging therapy | 1(6%) | 8(24%) | 9(18%) | 9 (100%) |

| Renal function impairment (TFG <60) |

- | 14(42%) | NA | 8 (57%) |

| Unknown TRT | 15(94%) | NA | NA | 15 (100%) |

| TRT <65% | 12(75%) | NA | NA | 9 (75%) |

| Healthcare service use | ||||

| Emergency department | 5(31%) | 12(36%) | 17(35%) | 17 (100%) |

| Hospitalization | 0(0%) | 3(9%) | 3(6%) | 3 (100%) |

| Questionnaire | Result | Explanation |

| CSAT | 4.63/5 | all patients except 1 answered being satisfied or very satisfied with LOLA. 1 patient answered a 3 (neutral) |

| NPS | 44.73% | 38 patients answered this question. Only 5 of them gave a punctuation lower than 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).