1. Introduction

Volleyball is classified as a high-intensity intermittent sport [

1,

2] that requires players to repeatedly perform explosive actions such as jumping, sprinting, braking, directional shifts, and forceful spiking [

1,

3]. Furthermore, since these skills must be intermittently repeated over extended periods, muscular endurance also plays a crucial role for volleyball players in maintaining a high level of performance [

2]. In this regard, it is crucial to consider the ability to maintain or increase muscle power and endurance during the competitive season to optimize performance [

4].

Several training strategies, most notably resistance and plyometric modalities, have been implemented to enhance both maximal and explosive strength, aiming particularly to improve vertical jump performance in volleyball athletes [

4,

5,

6]. Newton et al. [

5] observed an ~6% increase in jump performance among national-level male volleyball players after they engaged in either squats or dumbbell jump squats for a duration of 8 weeks. However, it is important to note that this study was conducted during the pre-season, and in-season training necessitates additional considerations. Training regimens should be adjusted during this period, considering factors such as training type, volume, and intensity, to align with the neuromuscular stress associated with competition. In this regard, Newton et al. [

4] investigated whether an 11-week periodized program combining traditional and ballistic resistance training could counteract the typical in-season decline in jump performance among volleyball players. Freitas-Junior et al. [

6] showed a significant improvement on vertical jump and COD after 6-weeks using different training strategies with weight vests with additional weight of 7.5% of individual weight in male volleyball players. When weight training was combined with plyometrics or ballistic training, vertical jump height increased [

7], suggesting that this combined approach may provide a greater stimulus for increasing vertical jump height compared to either weights or plyometric/ballistic training alone [

8]. Collectively, these results emphasize that vertical jump ability is multifactorial; therefore, training programs integrating multiple modalities are likely to promote broader neuromuscular adaptations across the components of jump performance [

9].

In team sports, most actions or movements require three-dimensional deceleration and acceleration, particularly during COD maneuvers and short displacements [

10,

11]. In volleyball, these maneuvers are evident in various movements, such as adjusting the body position before jumping during blocking actions or assuming a defensive stance. Hence, these tasks frequently demand unilateral force production, with a notable emphasis on the eccentric (ECC) phase of multidirectional movements [

12,

13]. In this regard, ECC strength training has been suggested as the primary determinant for COD and agility performance [

14]. However, in team sports like volleyball, strength training has typically mirrored traditional individual-sports training, focusing on bilateral weightlifting, which emphasizes a high degree of stimulation during the concentric (CON) phase. Consequently, it seems that ECC contractions are under-activated, and its benefits are not fully explored [

15,

16]. In this context, rotatory inertial devices have been developed to offer maximal resistance load throughout the CON phase of the movement, coupled with a significantly higher ECC load compared to traditional free weight exercises [

17]. Building upon this, Tous-Fajardo et al. [

12] demonstrated that strength training, with a focus on the ECC phase of movement using inertial devices, resulted in enhanced capabilities in COD, linear speed, and reactive jumping. This alternative approach can complement the traditional strength-training program, which typically emphasizes the vertical components of movements [

13,

18].

This is crucial because while most exercises emphasize movement in the vertical plane, most sports demand primarily horizontal movements, such as sprinting and changing direction. This has been cited as a potential reason for the limited transfer of traditional strength-power training effects to typical sports-related dynamic tasks [

19]. Gonzalo-Skok et al. [

13] examined the effects of two different programs, one involving repetitive bilateral-vertical movement (squat) and the other incorporating various unilateral-multidirectional movements (backward lunges, defensive steps, side-steps, crossover cutting, lateral crossover cutting and lateral squats), both utilizing an inertial conical device. The authors showed that unilateral-multidirectional training resulted in more substantial improvements in combined COD tests and lateral/horizontal jumping, whereas the opposite effect was observed in the bilateral-vertical dimension, particularly concerning linear sprinting and vertical jumping. Contreras et al. [

20] indicated that hip thrust exercise is executed in a manner where the force vector is oriented in the anteroposterior direction relative to the human body. Therefore, according to the force vector hypothesis, the hip thrust may be better tailored for sports that rely on horizontal force production, such as acceleration and sprinting [

20]. The authors showed a potentially advantageous effect in the hip thrust group compared to the front squat group in 10 m and 20 m sprint times, in a study involving adolescent athletes. However, the front squat group exhibited greater improvement in their vertical jump performance in comparison to the hip thrust group.

Considering the complexity of volleyball movements, the aim of this study is to examine the effects of a comprehensive strength-training regimen incorporating unilateral and bilateral actions, as well as multidirectional, vertical, and horizontal exercises (such as back squats, loaded countermovement jumps, hip thrusts, and lateral crossover cutting using a conical pulley) on various performance indicators among young elite volleyball players.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

Twenty young elite Spanish male volleyball players (U-16, age 15 ± 1.0 years, height 176.11 ± 0.09 cm, weight 67.47 ± 12.46 kg, body mass index 21.62 ± 2.7 kg·m2) voluntarily agreed to participate in this study. Data collection took place during the two last months of the season. The players participated in the play-offs of the Spanish league, and none of them had previously engaged in any strength-training program. All participants were involved in the typical volleyball routines with a similar weekly training volume (3-4 technical-tactical sessions/week of 60-90 min and 1 match per week). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol received approval from the local research ethics committee. After a detailed explanation of the aims, benefits, and risks involved in this study, all participants and their parents provided written informed assent and consent, respectively.

Study Design and Procedures

Using a randomized controlled study design (teams and not players), players from two different teams were divided into an experimental group (EXP, n = 12) and a control group (CON, n = 8). Participants in the CON group continued with their regular technical/tactical training, refraining from participating in strength training throughout the entire session. Players in the EXP group, alongside their regular volleyball training, participated in an additional strength-training program 1 or 2 times per week, consistently scheduled in the afternoon (6–8 PM) and separated by 48 hours, for a duration of 5 weeks. This program was centered on exercises such as the back squat, loaded countermovement jump, hip thrust, and lateral crossover step utilizing a vertical cone-shaped flywheel device. All participants underwent a standardized specific warm-up, consisting of 5 minutes of low intensity running, followed by 5 minutes of active dynamic stretching. Subsequently, they performed 3-4 submaximal countermovement jumps (CMJs) and 3-4 submaximal sprints over 30 meters, gradually increasing intensity until reaching maximum velocity. Rest intervals of 90 seconds were implemented between exercises. In the week prior to the commencement of the training protocol, a countermovement jump, 5-meter and 10-meter acceleration test, and COD test were conducted in sequence. Each test was separated by a 3-minute rest period. During these sessions, a full explanation of the experimental protocol and recommendations were given to the participants. After 5 weeks, 72 h after the last session, a post-test was performed under the same conditions as the pre-test.

Strength Training Exercises

Squat & Hip Thrust. Both exercises consisted of 2-3 sets of 4 repetitions at 40-60% 1RM (back squat: 1.28-0.98 m·s-1; hip thrust: 0.96-0.72 m·s-1).

Table 1 shows the programs and load progression for both exercises. The concentric phase was performed as fast as possible, while the eccentric phase was completed over ~2 seconds. The rest period between each set was 3 minutes. The mean propulsive velocity (MPV) of the first repetition was measured to fine-tune the load to the actual daily performance during each session. MPV is widely accepted as a reliable metric for estimating relative load intensity (%1RM), allowing accurate prescription and real-time monitoring of resistance training sessions [

21].

Loaded Countermovement jump. In relation to this exercise, each player adhered to the training program with an individualized load over the course of the 5 weeks. The load used in each week was as follows: i) weeks 1-2, a percentage of body mass (%BM) resulting in a 10% reduction of unloaded maximum height (Hmax); ii) weeks 3-4, a %BM with 15% reduction of Hmax ; and iii) week 5, a %BM with 20% reduction of Hmax. The players consistently completed 4 repetitions per set, with either 2 sets (weeks 1, 3, and 5) or 3 sets (weeks 2 and 4). Rest intervals were maintained at 15 seconds between repetitions and 3 minutes between sets.

Crossover step. Participants performed this exercise using a conical pulley (VersaPulley, Costa Mesa, CA), with the load set to elicit the maximum individual power for each player [

22]. The protocol began with 2 sets of 4+4 repetitions (right and left legs) in the first week, progressing to 2 sets of 6+6 repetitions in weeks 2 and 3, 3 sets of 4+4 repetitions in week 4, and finally, 3 sets of 6+6 repetitions during the last week (week 5). Recovery time between sets was 3 minutes. With these devices the “load” is given by the inertia of a rotating mass, which in turn depends on its geometrical (e.g., diameter and thickness) and physical properties (e.g., density of the material). To determine the to be used during the exercise, an assessment with inertias 2, 4 and 6 (0.11, 0.14, and 0.18 kg/m2, respectively) was conducted during the familiarization week. This assessment involved 4 repetitions per inertia with a 3-minute inter-inertia recovery period. The inertia that achieved the highest power output was selected. The protocol was performed using a specific analysis feature in a performance-measurement system compatible with this device (SmartCoachTM, SmartCoach Europe AB, Stockholm, Sweden) along with associated SmartCoach software (SmartCoach® v.5.2.0.5).

Performance Test

Physical performance tests were carried out on two different days, 1 week before starting the training period. On the first day, both groups underwent the CMJ test, followed by the 10 m acceleration test and the crossover step test. Players rested for at least 48 hours between each testing session. On the second day, the EXP group performed the loaded CMJ, followed by the crossover step in the conical pulley device, and then the incremental full-squat load and the barbell hip thrust test, in this specific order. Every assessment session took place at the same time of day (6–8 PM), thereby minimizing disruptions in circadian rhythms, and under similar environmental conditions.

An incremental loading test was conducted one week prior to the start of the training intervention and included both the back squat and the barbell hip thrust exercises. During the full squat, participants were allowed to perform plantar flexion at the end of the movement but were instructed not to leave the ground [

23]. Following the procedures described by Contreras et al. [

24], the barbell hip thrust was executed with the participant’s upper back resting on a bench. The feet were placed slightly wider than shoulder-width, with toes oriented either forward or slightly outward. A padded barbell was positioned directly over the hips, and subjects were instructed to extend the hips forcefully while maintaining a neutral spine and pelvis alignment.

For each load, MPV during the concentric phase of the squat was recorded (coefficient of variation [CV] = 2.9–4.0%; intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.92–0.94). Mechanical data were obtained using an isoinertial dynamometer (T-Force Dynamic Measurement System; Ergotech, Murcia, Spain), consisting of a linear velocity transducer connected to a personal computer through a 14-bit analog-to-digital interface and dedicated software. The system operated at a sampling frequency of 1000 Hz, allowing the direct recording of instantaneous vertical velocity. The propulsive phase was defined as the portion of the concentric action during which the measured acceleration exceeded the acceleration due to gravity (≥ 9.81 m·s⁻²) [

21]. This testing approach was adapted according to the methodology described by López-Segovia et al. [

25]. Testing began with an initial load of 20 kg, subsequently increased in 10-kg increments until MPV values of approximately 1.10 m·s⁻¹ for the full squat and 0.75 m·s⁻¹ for the hip thrust were reached. Thereafter, increments of 5 kg were applied. The number of repetitions at each load was determined from the MPV of the first repetition. Participants performed three repetitions when the bar velocity was ≥ 1.00 m·s⁻¹ in the back squat or ≥ 0.70 m·s⁻¹ in the hip thrust. When velocities were lower than these thresholds, only two repetitions were executed. Passive recovery periods of 4 minutes were provided between loading conditions. The test concluded once the MPV fell below 0.85 m·s⁻¹ and 0.60 m·s⁻¹ for the squat and hip thrust, respectively. For subsequent analyses, only the fastest repetition achieved at each load was retained as the representative value [

21].

Regarding the loaded countermovement jump, each participant completed an individualized assessment following the procedure described by Carlos-Vivas et al. [

26]. The test was performed using a weighted vest (Kettler®, Germany) with progressive external loads to examine variations in spatiotemporal performance parameters. Each athlete executed both unloaded jumps and loaded conditions equivalent to 5%, 10%, and 15% of their body mass. For every load condition, two maximal attempts were carried out, resulting in a total of six trials. A 90-second passive recovery period was provided between trials to prevent fatigue.

The CMJ height was measured using infrared-ray cells integrated into the OptoGait System (Microgate, Bolzano, Italy). Participants performed five trials of the CMJ exercise, with 20 seconds of rest between each trial. Throughout the CMJ trial, participants maintained their hands on the hips and performed a continuous countermovement consisting of knee extension followed by flexion to roughly a 90° angle before immediately initiating the upward jump to achieve maximal take-off height. Jump height, representing the vertical displacement of the center of gravity, was computed from flight time using the ballistic equation H = tv2 · g ·8–1 (m); where

g corresponds to gravitational acceleration (9.81 m·s⁻²) [

21]. The best and worst values of the five jumps were excluded from the calculation. The mean of three remaining CMJs was recorded for subsequent analysis.

Sprint time was measured using a dual-beam electronic timing gate (Witty, Microgate, Bolzano, Italy). A linear sprint assessment covering 10 meters was administered, including an intermediate 5-meter split to record partial and total times. Participants initiated each sprint from a standing start, positioning the front foot approximately 1 meter behind the initial timing gate. Dual-beam photocell systems were set at 0.83 m for the start line and 1.16 m for both the midpoint and finish lines. All trials were executed on an indoor synthetic surface while wearing standard volleyball footwear to ensure consistency. Each athlete completed two maximal-effort sprints, separated by at least 3 minutes of passive rest to minimize fatigue. The fastest time achieved across both trials was used for subsequent statistical analysis.

The COD ability was assessed by analyzing a specific movement performed in front of the volleyball net. This movement involved a lateral step followed by a cross step and a block jump. The contact time during the second step (crossover step) was measured using a contact platform (OptoGait, Microgate, Bolzano, Italy). Each test (right and left; COD-R and COD-L, respectively) was conducted twice, with 45 seconds of recovery between trials, and the best repetition was recorded (CV = 3.1–4.4%; ICC = 0.89–0.92).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), accompanied by the corresponding effect size and its qualitative interpretation. The normality of the dataset was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test before conducting inferential analyses. Differences across time (within-subjects) and between groups (between-subjects) were examined through a two-way repeated measures design. When significant effects were detected, paired t-tests were performed to evaluate specific time effects within each group. Statistical significance was established at p < 0.05. Effect sizes were calculated to estimate the magnitude of observed changes. For repeated-measures comparisons, partial eta-squared (η²p) was computed and categorized as trivial (<0.01), small (0.01–0.06), moderate (0.06–0.15), or large (>0.15). Cohen’s d was used to assess simple effects, following these qualitative thresholds: trivial (<0.1), small (0.1–0.3), moderate (0.3–0.5), large (0.5–0.7), very large (0.7–0.9), and nearly perfect (>0.9). All statistical analyses were conducted using JASP software (v0.11.1; JASP Team, 2019).

3. Results

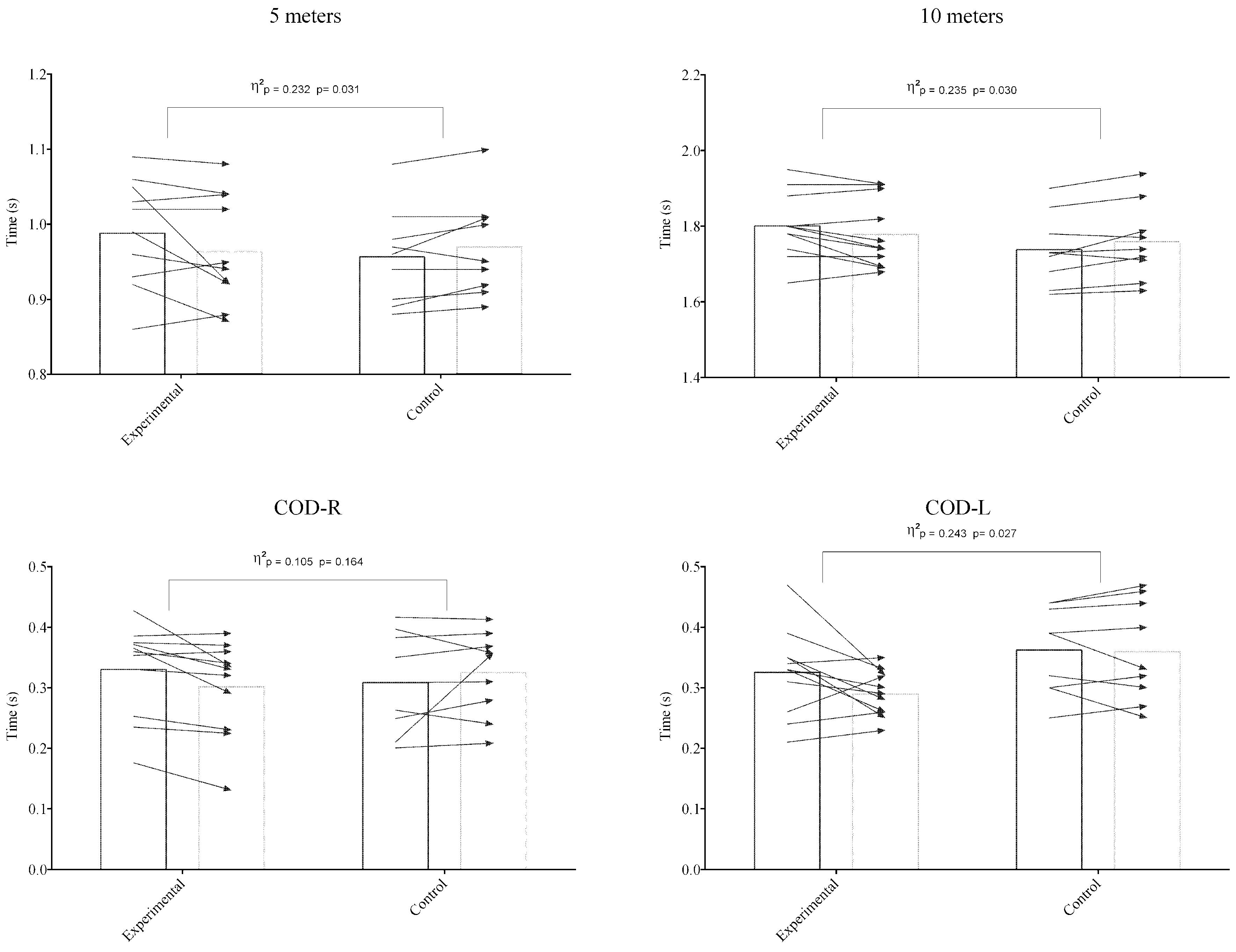

Figure 1 presents descriptive values and interactions effects for the variables over time, while Figure 2 displays descriptive values for CMJ results. There were significant Time by Group interactions in the 5 m (F18,1= 5.541, p= 0.030, η²p = 0.235, QUAL= large) and 10 m sprint time (F18,1= 8.113, p= 0.011, η²p = 0.311, QUAL: large), CMJ height (F18,1= 5.788, p= 0.027, η²p = 0.243, QUAL: large) and COD-R (F18,1= 5.451, p= 0.031, η²p = 0.232, QUAL: large). No statistically significant Time x Group interaction (F18,1 = 2.11; p = 0.164; partial η²p = 0.11—moderate) was found in COD-L time. This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

4. Discussion

This study, to our knowledge, is the first to investigate the effects of a combined resistance training program tailored specifically for young male volleyball players. The primary objective of this study was to assess the impact of a 5-week, in-season regimen comprising combined exercises such as back squat, barbell hip thrust, loaded countermovement jump, and crossover step using a conical pulley device on the lower body performance of young male volleyball players. The main finding of this study was that the EXP group showed a distinct change in performance compared to the CON group. Specifically, the EXP group presented a very large improvement in countermovement jump height and in COD-R time. In addition, the EXP group showed an improving trend in the sprint time and COD-L, while the CON group exhibited a decreasing trend.

Jumping ability represents a key performance determinant in volleyball, underpinning crucial offensive and defensive movements such as spiking and blocking [

27,

28]. Moreover, the ability to maintain or increase jumping performance during the competitive season is a vital consideration [

4]. A lengthy competitive season, characterized by intensive skills training and frequent competitions, has been noted to negatively impact the power output of volleyball players [

29]. Building upon this observation, our study revealed a significant Time by Group interaction, with vertical jump height displaying a large and significant effect (η²p = 0.243). More specifically, we noted an increase of jump performance in the EXP training group (3.75±4.64%), while a decrease was observed in the CON group found (-0.97±3.35%), consistent with the findings of Newton et al. [

4]. In their study, they reported an increase in CMJ power output (3.0% and 5.5% for peak and average, respectively) following a ballistic training period (loaded jump squats on the Smith machine) lasting 4 weeks. Moreover, these authors [

29] hypothesized that if the resistance exercise program was implemented, it could mitigate or eliminate the declines in jump performance observed over the competitive season in volleyball athletes. Our results support this hypothesis, as the CON group showed a moderate decrease in the CMJ test (ES: -0.22), while the EXP group demonstrated a very large improvement after the periodized strength-training program (ES: 0.79).

Regarding sprint ability, significant Time by Group interactions were observed in both distances, indicating differences between the groups over time. However, neither group demonstrated a significant change in sprint time. Of note, the EXP group showed a large improvement in their 5 m (2.40±4.40%; ES:0.55) and 10 m times (1.25±2.18%; ES:0.59), while the CON group displayed a large to very large impairment in both tests (-1.41±2.09% [ES: -0.67] and -1.21±1.58% [ES: -0.76], respectively). Hence, we are tempted to attribute the finding of no increase in linear acceleration to the modest emphasis on hamstring muscle use in our program. Notably, the generation of hip extensor force plays a central role in upward and forward propulsion, especially during acceleration and sprint phases [

30]. In this sense, Tous-Fajardo et al. [

12] suggested that resistance exercise favoring eccentric overload of this muscle group should be incorporated, as they serve as a potent stimulus for improving linear sprint speed. On the other hand, the hip thrust exercise used in the current study elicits a high hamstring [

31]. Additionally, the positioning of the load during the barbell hip thrust across the hips encourages reliance on the biceps femoris for complete hip extension, as the load applies downward force against the hips [

31]. Furthermore, previous findings have suggested that the barbell hip thrust is equally as effective as the Romanian deadlift for isolating the hip extensors [

31]. However, other studies have demonstrated that to effectively enhance acceleration ability with this exercise, a higher load is required [

20]. Contreras et al. [

20] demonstrated how a hip thrust exercise improved performance in the 10 m sprint test using a higher load (65-85% 1RM) following a 6-week training program. Thus, it seems that when the duration of the program is short, greater intensity is required to achieve improvements in acceleration ability.

In multidirectional team sports, including volleyball, football, handball, rugby, and basketball, the capacity to perform quick COD is widely recognized as a decisive element influencing competitive performance [

32]. COD maneuvers involve eccentric muscle activation during braking, immediately succeeded by concentric contraction to produce the propulsive impulse required for reacceleration [

33]. Strong eccentric capacity is essential in sports that demand frequent directional changes, as athletes must decelerate quickly, control body posture, and then accelerate explosively toward a new trajectory [

34]. In addition, COD is a unilateral and multidirectional skill, making these factors significant when selecting exercises to enhance it [

13]. Since volleyball actions involve multidirectional accelerations and decelerations, incorporating cone-shaped flywheel devices or pulley systems may enhance performance by enabling resistance across multiple movement planes [

35]. Resistance training using inertial flywheel systems has been shown to produce superior improvements in muscle power output compared with conventional weight-stack modalities [

36]. In this regard, our results showed that the EXP group experienced a very large improvement in COD-R, while in COD-L they showed a greater tendency to improve compared to the CON group. Our results align with findings from Gonzalo-Skok et al. [

13], who observed significant improvements after an 8-week strength training program incorporating tridimensional exercises using a conical pulley device among amateur/semiprofessional team-sport players (Effect Size: 0.61) .

Finally, we acknowledge several limitations within our study. Due to the inclusion of four distinct combined training exercises in the current program, it is challenging to determine which one might have had a more significant impact on the results. Moreover, although the young players tested in this study were highly trained in volleyball, they were novices in terms of in-season high-intensity strength training. Thus, extrapolating the current results to more experienced athletes in terms of strength training should be approached with caution.

5. Conclusions

The current study demonstrates that a five-week, in-season combined resistance training program integrating bilateral and unilateral exercises in multiple planes of movement—such as back squat, loaded countermovement jump, hip thrust, and lateral crossover step using a vertical cone-shaped flywheel device—can effectively enhance lower-body performance in young male volleyball players. Specifically, EXP group exhibited significant improvements in CMJ height and COD ability to the right, as well as positive trends in sprint performance. These findings suggest that incorporating multidirectional and eccentric-overload exercises using inertial devices into traditional in-season training routines may optimize neuromuscular adaptations, contributing to better agility and explosive performance in youth volleyball players. Future research should explore longer intervention periods, varied inertial loads, and different age groups or competition levels to confirm the generalizability and long-term effects of this training approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., B.S. and A.M.; methodology, M.H. and M.R.; software, A.M.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, M.H., F.J.N., B.S. and M.R.; resources, M.H.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H.; writing—review and editing, F.Y.N., L.C., B.S and F.J.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Universidad CEU Fernando III (06-25 UF3-PI; 03/11/25) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the collaboration and support of the volleyball clubs, CV Fuentes and CV Arahal, whose participation was essential for the successful completion of this study. We would also like to express our sincere appreciation to all the players for their commitment, effort, and dedication throughout the training and testing procedures. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COD |

Change of direction |

| ECC |

Eccentric |

| CON |

Control group |

| EXP |

Experimental group |

| CMJ |

Countermovement Jump |

| Hmax |

Maximun height |

| CV |

Coefficient of variation |

| ICC |

Intraclass coefficient of correlation |

| MPV |

Mean propulsive velocity |

| COD-R |

Change of direction on the right side |

| COD-L |

Change of direction on the left side |

| SD |

Standar Desviation |

References

- Marques, M.; González-Badillo, J.; Cunha, P.; Resende, L.; Santos, M.D.P. Changes in strength parameters during twelve competitive weeks in top volleyball athletes. Int J Volley Res 2004,7:23–28.

- Stojanović, E.; Ristić, V.; McMaster, D.T.; Milanović, Z. Effect of Plyometric Training on Vertical Jump Performance in Female Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport Med 2017,47(5):975–986.

- Cardoso-Marques, M.A.; González-Badillo, J.J.; Kluka, D.A. In-Season Resistance Training for Professional Male Volleyball Players. Strength Cond J 2006,28(6):16–27.

- Newton, R.U.; Rogers, R.A.; Volek, J.S.; Häkkinen, K.; Kraemer, W.J. Four Weeks of Optimal Load Ballistic Resistance Training at the End of Season Attenuates Declining Jump Performance of Women Volleyball Players. J Strength Cond Res 2006,20(4):955-961.

- Newton, R.U.; Kraemer, W.J.; Häkkinen, K. Effects of ballistic training on preseason preparation of elite volleyball players. Med Sci Sport Exerc 1999,31(2):323–330.

- Freitas-Junior, C.G.; Fortes, L.S.; Santos, T.M.; Batista, G.R.; Gantois, P.; Paes, P.P. Effects of different training strategies with a weight vest on countermovement vertical jump and change-of-direction ability in male volleyball athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitnes. 2021,61(3):343–349.

- Lyttle, A.D.; Wilson, G.J.; Ostrowski, K.J. Enhancing Performance: Maximal Power Versus Combined Weights and Plyometrics Training. J Strength Cond Res 1996,10(3):173-179.

- Adams, K.: O’Shea, J.P., O’Shea, K.L., Climstein, M. The effect of six weeks of squat, plyometric and squat-plyometric training on power production. J Strength Cond Res 1992,6(1):36–41.

- Newton, R.K.W. Developing explosive muscular power: implications for a mixed methods training strategy. Strength Cond J 1994,16(5):20–31.

- Ben Abdelkrim, N.; Chaouachi, A.; Chamari, K.; Chtara, M.; Castagna, C. Positional Role and Competitive-Level Differences in Elite-Level Menʼs Basketball Players. J Strength Cond Res 2010,24(5):1346–155.

- Stolen, T.; Chamari, K.; Castagna, C.; Wisloff, U. Physiology of Soccer. Sport Med 2005,35(6):501–536.

- Tous-Fajardo, J.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Arjol-Serrano, J.L.; Tesch, P. Enhancing Change-of-Direction Speed in Soccer Players by Functional Inertial Eccentric Overload and Vibration Training. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2016,11(1):66–73.

- Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Tous-Fajardo, J.; Valero-Campo, C.; Berzosa, C.; Bataller, A.V.; Arjol-Serrano, J.L., et al. Eccentric-Overload Training in Team-Sport Functional Performance: Constant Bilateral Vertical Versus Variable Unilateral Multidirectional Movements. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2017,12(7):951–958.

- Spiteri, T.; Newton, R.U.; Binetti, M.; Hart, N.H.; Sheppard, J.M.; Nimphius, S. Mechanical Determinants of Faster Change of Direction and Agility Performance in Female Basketball Athletes. J Strength Cond Res 2015,29(8):2205–2214.

- Norrbrand, L.; Fluckey, J.D.; Pozzo, M.; Tesch, P.A. Resistance training using eccentric overload induces early adaptations in skeletal muscle size. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007 Nov 29;102(3):271–81.

- Norrbrand, L.; Pozzo, M.; Tesch, P.A. Flywheel resistance training calls for greater eccentric muscle activation than weight training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010 Nov 30;110(5):997–1005.

- Núñez, F.J., Suarez-Arrones, L.J.; Cater, P.; Mendez-Villanueva, A. The High-Pull Exercise: A Comparison Between a VersaPulley Flywheel Device and the Free Weight. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2017 Apr;12(4):527–32.

- Vladimir, M.; Zatsiorsky, W.J.K. Science and practice of strength training. Human Kinetics. Champaign, IL; 2006.

- Young, W.B. Transfer of Strength and Power Training to Sports Performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2006 Jun;1(2):74–83.

- Contreras, B.; Vigotsky, A.D.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Beardsley, C.; McMaster, D.T.; Reyneke, J.H.T., et al. Effects of a Six-Week Hip Thrust vs. Front Squat Resistance Training Program on Performance in Adolescent Males. J Strength Cond Res. 2017.

- González-Badillo, J.J.; Sánchez-Medina, L. Movement Velocity as a Measure of Loading Intensity in Resistance Training. Int J Sports Med. 2010 May 23;31(05):347–52.

- de Hoyo, M.; Pozzo, M.; Sañudo, B.; Carrasco, L.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Domínguez-Cobo, S. et al. Effects of a 10-Week In-Season Eccentric-Overload Training Program on Muscle-Injury Prevention and Performance in Junior Elite Soccer Players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2015 Jan;10(1):46–52.

- De Hoyo, M.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Sañudo, B.; Carrascal, C.; Plaza-Armas, J.R.; Camacho-Candil, F.; et al. Comparative effects of in-season full-back squat, resisted sprint training, and plyometric training on explosive performance in U-19 elite soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2016 Feb 1;30(2):368–77.

- 24. Contreras, B.; Cronin, J.; Schoenfeld, B. Barbell Hip Thrust. Strength Cond J. 2011 Oct;33(5):58–61.

- 25. López-Segovia, M.; Palao Andrés, J.M.; González-Badillo, J.J. Effect of 4 Months of Training on Aerobic Power, Strength, and Acceleration in Two Under-19 Soccer Teams. J Strength Cond Res. 2010 Oct;24(10):2705–14.

- 26. Carlos-Vivas, J.; Freitas, T.T.; Cuesta, M.; Perez-Gomez, J.; De Hoyo, M.; Alcaraz, P.E. New Tool to Control and Monitor Weighted Vest Training Load for Sprinting and Jumping in Soccer. J Strength Cond Res. 2019 Nov;33(11):3030–8.

- Thissen-Milder, M.; Mayhew, J. Selection and classification of high school volleyball players from performance tests. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1991;31(3):380–4.

- Rousanoglou, E.N.; Georgiadis, G.V.; Boudolos, K.D. Muscular Strength and Jumping Performance Relationships in Young Women Athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2008 Jul;22(4):1375–8.

- Häkkinen, K. Changes in physical fitness profile in female volleyball players during the competitive season. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 1993;33(3):223–32.

- Neumann, D.A. Kinesiology of the Hip: A Focus on Muscular Actions. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2010 Feb;40(2):82–94.

- Delgado, J.; Drinkwater, E.J.; Banyard, H.G.; Haff, G.G.; Nosaka, K. Comparison Between Back Squat, Romanian Deadlift, and Barbell Hip Thrust for Leg and Hip Muscle Activities During Hip Extension. J Strength Cond Res. 2019 Oct;33(10):2595–601.

- Bourgeois, F.A.; McGuigan, M.R.; Gill, N.D.; Gamble, P. Physical Characteristics and Performance in Change of Direction Tasks: a Brief Review and Training Considerations. J Aust Strength Cond. 2017;25(5):104–17.

- Castillo-Rodríguez, A.; Fernández-García, J.C.; Chinchilla-Minguet, J.L.; Carnero, E.Á. Relationship Between Muscular Strength and Sprints with Changes of Direction. J Strength Cond Res. 2012 Mar;26(3):725–32.

- Chaabene, H.; Prieske, O.; Negra, Y.; Granacher, U. Change of Direction Speed: Toward a Strength Training Approach with Accentuated Eccentric Muscle Actions. Sport Med. 2018 Aug 28;48(8):1773–9.

- Chiu, L.Z.F.; Salem, G.J. Comparison of Joint Kinetics during Free Weight and Flywheel Resistance Exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2006;20(3):555.

- Maroto-Izquierdo, S.; García-López, D.; Fernandez-Gonzalo, R.; Moreira, O.C.; González-Gallego, J.; de Paz, J.A. Skeletal muscle functional and structural adaptations after eccentric overload flywheel resistance training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 2017 Oct;20(10):943–51.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).