1. Introduction

Acute heart failure (AHF) is a clinical syndrome defined by the sudden onset or rapid worsening of heart failure (HF) symptoms that requires urgent medical intervention [

1]. It is a major cause of morbidity, mortality, and healthcare resource utilization worldwide, particularly among older adults, due to its high prevalence and frequent hospital admissions and readmissions.

The progressive aging of the population, together with improved survival from other cardiovascular diseases, has led to a sustained increase in the number of elderly patients with HF. The prevalence of HF doubles with each decade of life, from approximately 1% in individuals younger than 55 years to more than 10% in those over 70, and nearly 20% in those older than 80 years [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. By 2050, it is estimated that 17% of the global population will be older than 85 years [

7,

8,

9], anticipating a substantial rise in hospitalizations, demand for healthcare resources, and clinical complexity.

In older patients, HF is characterized by a distinct clinical and prognostic profile. It frequently coexists with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus (DM), atrial fibrillation (AF), and chronic kidney disease, which influence disease progression and therapeutic response [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Geriatric syndromes including frailty, sarcopenia, and cognitive decline further reduce physiological reserve and increase vulnerability to acute decompensation [

4,

16]. Polypharmacy, highly prevalent in this population, adds to the risk of drug interactions, adverse events, and poor adherence, complicating the application of guideline-directed pharmacological therapy [

17,

18].

These factors highlight the need for an individualized and multidisciplinary approach to HF management in the elderly, combining optimization of medical treatment with functional and cognitive assessment, and prioritizing quality of life and prevention of readmissions over strategies exclusively focused on survival.

Despite the predominance of older patients among those with HF, most available evidence derives from studies conducted in younger populations with fewer comorbidities. As a result, current therapeutic recommendations and prognostic models may not be fully applicable to elderly patients, in whom treatment goals must balance clinical efficacy with functionality and quality of life. This lack of representativeness limits the extrapolation of classical study results to clinical practice, particularly in the HED setting, where many episodes of acute decompensation are managed.

HED are the usual point of entry for elderly patients with AHF [

19]. Following initial evaluation and stabilization, most require hospital admission, mainly to Internal Medicine units [

20,

21,

22]. However, a considerable proportion experience early readmissions or die within the first weeks after discharge, underscoring the need for effective risk stratification tools from the earliest stages of care. Traditionally, risk stratification has relied on clinical and laboratory parameters [

23,

24,

25]. More recently, other determinants such as precipitating factors (PFs) have emerged, although they have received less attention despite their prognostic relevance [

26,

27].

The aim of the present study is to identify the main prognostic determinants of mortality in elderly patients treated for AHF in a HED, assessing their impact both in the short term (30 days) and in the long term (1 year). Given that the clinical course of HF in older adults may vary substantially depending on the stage of the disease, it is essential to understand which variables differentially influence early versus late outcomes.

This temporal approach aims to distinguish the clinical determinants that shape prognosis across different phases of the disease, thereby supporting more accurate risk stratification and individualized therapeutic planning. Ultimately, the goal is to optimize initial emergency care and enhance continuity of care by identifying those factors that warrant closer monitoring and follow-up in this highly vulnerable patient population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This study is based on a secondary analysis of the EAHFE (Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments) registry, an observational, multicenter, multipurpose, non-interventional analytical registry with prospective follow-up in 45 hospitals across Spain. For this analysis, only patients treated at the HED of the Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital (HUMV) in Cantabria were included.

The design and recruitment process of the EAHFE registry have been described previously [

28,

29,

30]. In brief, the registry prospectively included all consecutive who presented to the ED with a primary diagnosis of AHF, established according to Framingham clinical criteria, and who provided written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included inability to complete follow-up, a final hospital discharge diagnosis unrelated to AHF, and AHF occurring in the context of a concurrent ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The diagnosis was confirmed through review of the medical record and complementary test results by the principal investigator.

In accordance with the national protocol of the EAHFE registry, data collection was conducted prospectively following a standardized design based on short, predefined recruitment periods at the national level. These periods corresponded to the years 2007, 2009, 2011, 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2022. This methodology, established by the EAHFE project itself, ensured methodological consistency, temporal diversity, and representativeness of the cohort of patients with AHF [

28,

29,

30].

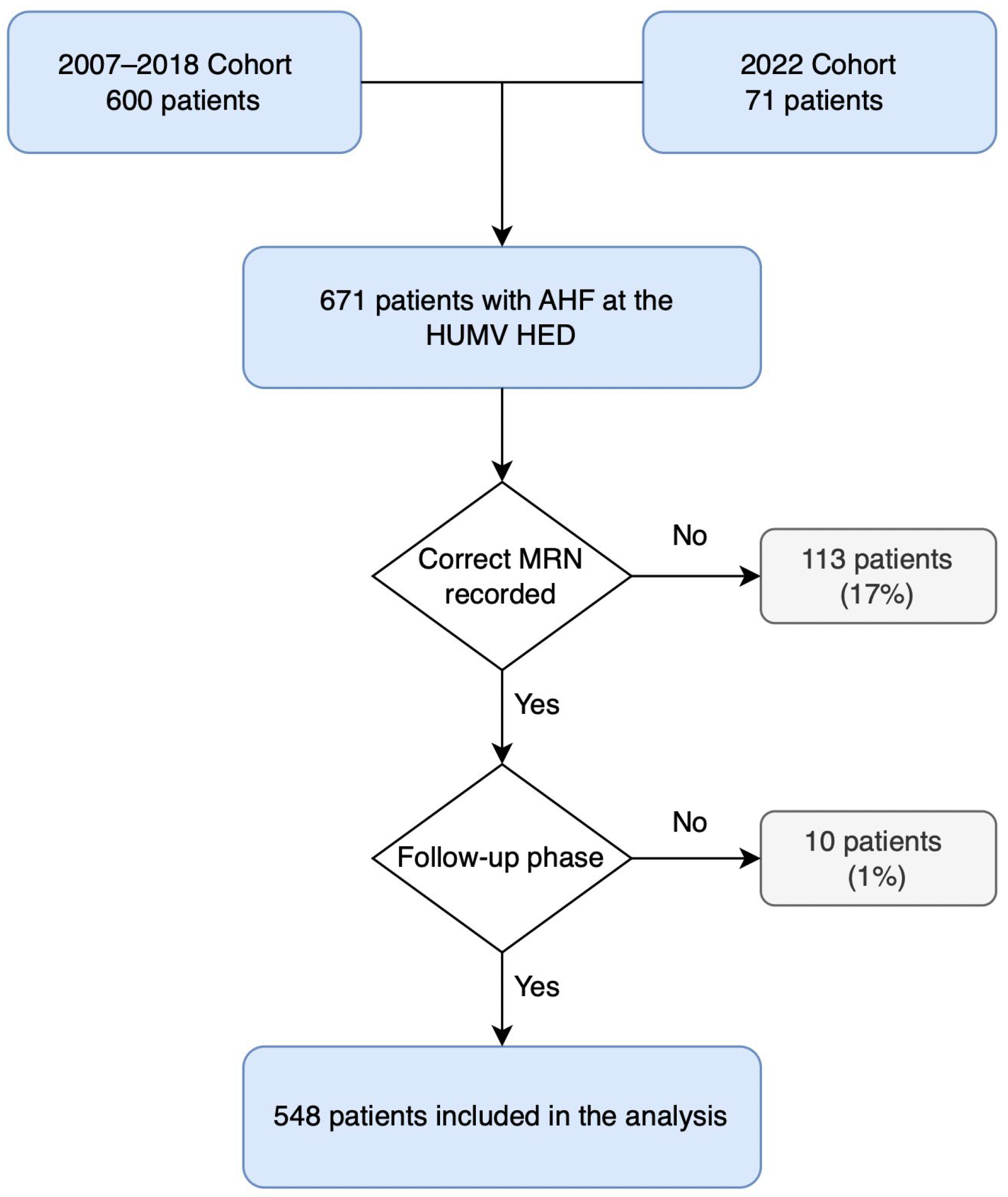

2.2. Participants

A total of 671 patients with AHF were registered, of whom 123 (18%) were excluded due to inability to complete follow-up, mainly because of missing medical record numbers (MRN) from the 2007 data collection period or residence outside the autonomous region. The final analyzed sample included 548 elderly patients with AHF. The flowchart detailing inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in

Figure 1.

2.3. Study Variables

A total of 36 independent variables were collected and grouped into different categories: two demographic variables (age and sex); 10 comorbidities (DM, ischemic heart disease, AF, atrial flutter, valvular heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], dementia, cirrhosis, prior HF, and New York Heart Association [NYHA] functional class); eight PFs for AHF (infection, rapid AF, rapid atrial flutter, anemia, hypertensive crisis, ACS, treatment non-adherence, and unknown); seven clinical variables at admission (respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, AHF type, low-output symptoms, lower-limb edema, third heart sound, and pulmonary crackles); five laboratory variables (hemoglobin, creatinine, potassium, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP], and troponin); one electrocardiographic (ECG) variable (left ventricular hypertrophy); and three ED management variables (use of intravenous nitroglycerin, use of non-invasive ventilation, and hospital admission).

The primary outcome variable was all-cause mortality at 30 days and 12 months, using the date of HED presentation as the index event.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were described as absolute and relative frequencies, and continuous variables as mean and standard deviation, or median and interquartile range (IQR), according to their distribution (assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test).

Group comparisons were performed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, as appropriate. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

To identify factors associated with mortality, logistic regression analysis was used. Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted independently for 30-day and 12-month mortality. A univariate analysis was performed to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the Wald statistic. Variables with a p-value > 0.25 in the univariate analysis were subsequently included in the multivariate analysis, following the criterion proposed by Hosmer and Lemeshow [

31], and supported by other reference authors [

32]. For model selection, an automatic variable selection procedure using the backward method was applied. Subsequently, several models were generated based on current knowledge and pathophysiological rationale, and compared with the initial models. To assess the predictive capacity of the different models, the area under the curve (AUC) was used.

Analyses were performed with SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc® v23.13 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975), revised in 2013, and with current regulations on personal data protection. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the EAHFE registry and to be contacted for follow-up.

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias on January 12, 2022 (project code: CEImPA No. 2022.015). This approval covers the continued use of data collected during previous phases of the EAHFE registry. In addition, the Ethics Committee of Cantabria (IDIVAL) issued a local ratification on January 28, 2022.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Profile of the Cohort

A total of 548 patients with a diagnosis of AHF were analyzed. The mean age was 80.7 years, and 49.6% were female. Most patients had multiple comorbidities, the most frequent being AF (35.8%), and ischemic heart disease (23.7%). Prior HF was present in 62.6% of cases, predominantly NYHA functional class I-II (67.70%). The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients included in this study have been previously described in detail by Ostolaza-Tazón et al. [

33] and are summarized in

Table 1.

On arrival, most patients had an oxygen saturation of 93.6%, and 6.8% presented with a respiratory rate exceeding 25 breaths/min. Congestive signs were common (78.1%), with the most frequent being peripheral edema (65.3%) and pulmonary crackles (67.0%). PFs were identified in 69.2% of cases, the most common of which were infection (34.7%) and rapid AF (17.3%). Mean hemoglobin was 12.4 g/dL, and mean creatinine was 1.4 mg/dL. Some of these clinical outcomes were also reported by Ostolaza-Tazón et al. [

33] and are reorganized here for the current analysis, as summarized in

Table 2.

3.2. In-Hospital Course and Mortality

Most patients evaluated in the HED for AHF required hospitalization (76.8%), mainly in Internal Medicine (44.3%), followed by Cardiology (19.9%) and the Short-Stay Unit (6.0%). A small percentage were admitted to Intensive or Coronary Care Units (1.9%) or to other services, such as Geriatrics (6.5%). Conversely, 21.4% of patients did not require admission and were discharged directly from the HED.

During follow-up, 11.1% of patients died within 30 days (61 patients), and the mortality rate increased to 29.9% at 1 year (164 patients) after the index episode. Baseline characteristics stratified by survival status at 30 days and 12 months are presented in

Supplementary Table S1.

3.3. Prognostic Factors for Mortality

Analysis of prognostic factors revealed significant associations between several clinical variables and mortality across different follow-up periods.

3.3.1. Univariate Analysis of 30-Day Mortality

In the univariate analysis of 30-day mortality, several factors were identified as being associated with an increased risk of death. Among them, advanced age (OR 1.08; 95% CI 1.04–1.12; p < 0.01), ischemic heart disease (OR 2.12; 95% CI 1.17–3.84; p = 0.01), valvular heart disease (OR 2.10; 95% CI 1.13–3.90; p = 0.02), and baseline NYHA class IV (OR 11.76; 95% CI 3.47–39.83; p < 0.01) stood out. Regarding the AHF episode, both the hypotensive form without shock (OR 6.58; 95% CI 1.81–23.89; p < 0.01) and the hypotensive form with cardiogenic shock (OR 14.33; 95% CI 1.84–111.44; p = 0.01), as well as episodes precipitated by ACS (OR 28.67; 95% CI 5.28–155.62; p < 0.01), were significantly associated with short-term mortality. Elevated creatinine levels (OR 1.39; 95% CI 1.16–1.67; p < 0.01) and lower oxygen saturation (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.91–0.98; p < 0.01) were also linked to poorer outcomes.

Some variables showed a trend toward association without reaching statistical significance, such as previous AHF episodes (OR 1.58; 95% CI 0.85–2.95; p = 0.15), respiratory rate >30 bpm (OR 2.08; 95% CI 0.65–6.61; p = 0.22), or hospital admission (OR 2.10; 95% CI 0.93–4.78; p = 0.08).

Other factors showed a trend toward a protective effect, although without statistical significance, such as a history of AF (OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.37–1.28; p = 0.23), AF as a PF (OR 0.58; 95% CI 0.24–1.40; p = 0.23), higher hemoglobin levels (OR 0.91; 95% CI 0.79–1.05; p = 0.18), and the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy on ECG (OR 0.30; 95% CI 0.04–2.23; p = 0.24).

Other comorbidities and clinical or analytical findings were not associated with short-term mortality, including DM (OR 1.35; 95% CI 0.76–2.39; p = 0.31) and COPD (OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.27–1.80; p = 0.44). Similarly, symptoms such as lower limb edema (OR 1.04; 95% CI 0.57–1.88; p = 0.91) or pulmonary crackles (OR 0.96; 95% CI 0.53–1.74; p = 0.88) did not reach statistical significance, nor did other potential PFs of the AHF episode, such as therapeutic non-adherence (not estimable) or hypertensive crisis (OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.07–4.15; p = 0.55).

3.3.2. Univariate Analysis of 12-Month Mortality

In the univariate analysis at 12 months, advanced age (OR 1.05; 95% CI 1.03–3.48; p < 0.01), valvular heart disease (OR 1.66; 95% CI 1.07–2.57; p = 0.02), and creatinine levels (OR 1.26; 95% CI 1.07–1.49; p < 0.01) remained significantly associated with mortality. Regarding NYHA functional classes, in addition to class IV, class III (OR 2.88; 95% CI 1.68–4.97; p < 0.01) reached statistical significance in long-term prediction, while class II (OR 1.70; 95% CI 1.01–2.88; p = 0.05) showed a trend toward significance without fully reaching it.

Additionally, new predictors emerged that had not reached statistical significance at 30 days, such as a history of previous AHF episodes (OR 2.05; 95% CI 1.37–3.07; p < 0.01) and hospital admission (OR 2.14; 95% CI 1.31–3.48; p < 0.01). Rapid AF as a PF (OR 0.57; 95% CI 0.34–0.97; p = 0.04), the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy on ECG (OR 0.33; 95% CI 0.11–0.96; p = 0.04), and hemoglobin levels (OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.77–0.92; p < 0.01) also reached statistical significance and were associated with lower mortality.

Other factors that were significant at 30 days, such as ischemic heart disease (OR 1.46; 95% CI 0.96–2.21; p = 0.08), ACS as a PF (OR 2.01; 95% CI 0.97–4.20; p = 0.06), or the hypotensive form with cardiogenic shock (OR 3.45; 95% CI 0.65–18.44; p = 0.15), showed a similar trend but did not reach significance at 12 months. Likewise, oxygen saturation, which had shown short-term association, lost significance at 12 months (OR 0.99; 95% CI 0.95–1.02; p = 0.39).

Potassium levels (OR 1.25; 95% CI 0.98–1.58; p = 0.07), which had shown a trend toward worse prognosis at 30 days, continued to show that trend without reaching statistical significance. Similarly, DM (OR 1.47; 95% CI 1.01–2.14; p = 0.05) showed a trend toward increased long-term mortality, without reaching statistical significance.

Other clinical findings such as lower limb edema (OR 1.12; 95% CI 0.76–1.65; p = 0.56) or pulmonary crackles (OR 0.97; 95% CI 0.66–1.43; p = 0.87), as well as most PFs (infection, anemia, hypertensive crisis, therapeutic non-adherence, or unknown cause), were not associated with long-term mortality.

Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 present the complete results of the univariate analyses corresponding to the 30-day and 12-month follow-up periods, respectively.

3.4. Multivariable Analysis of Prognostic Factors

Multivariable analysis confirmed similar associations to those observed in the univariate analysis.

3.4.1. Multivariate Analysis of 30-Day Mortality

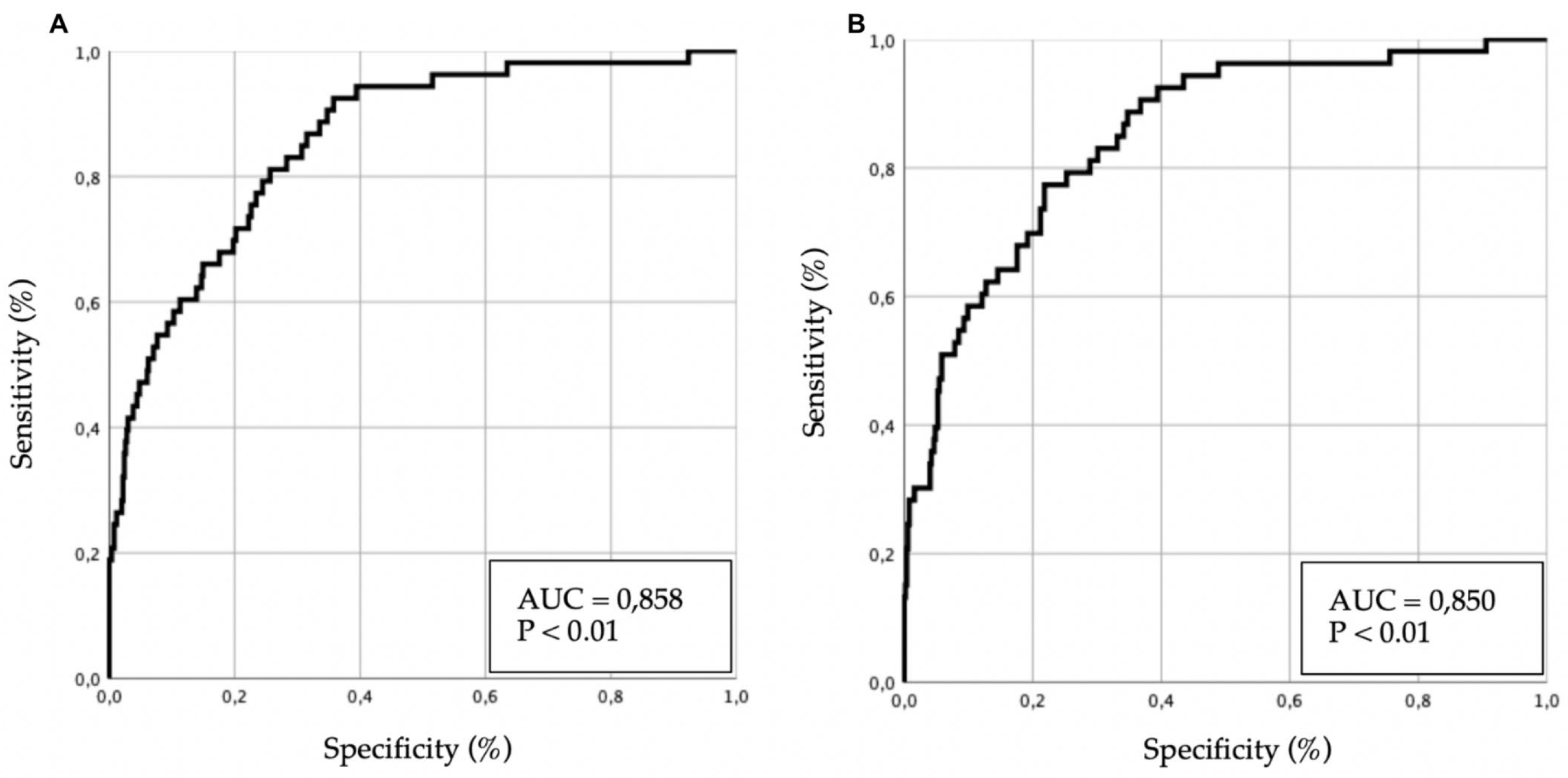

Several multivariate models were developed, and their results are presented in

Table 3. Predictive performance is illustrated in

Figure 2 (receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curves).

In the multivariate analysis of 30-day mortality, age, ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, and hypotensive forms of AHF (with or without cardiogenic shock) remained significant predictors. Among comorbidities, previous episodes of AHF showed a trend toward significance, although without reaching statistical relevance.

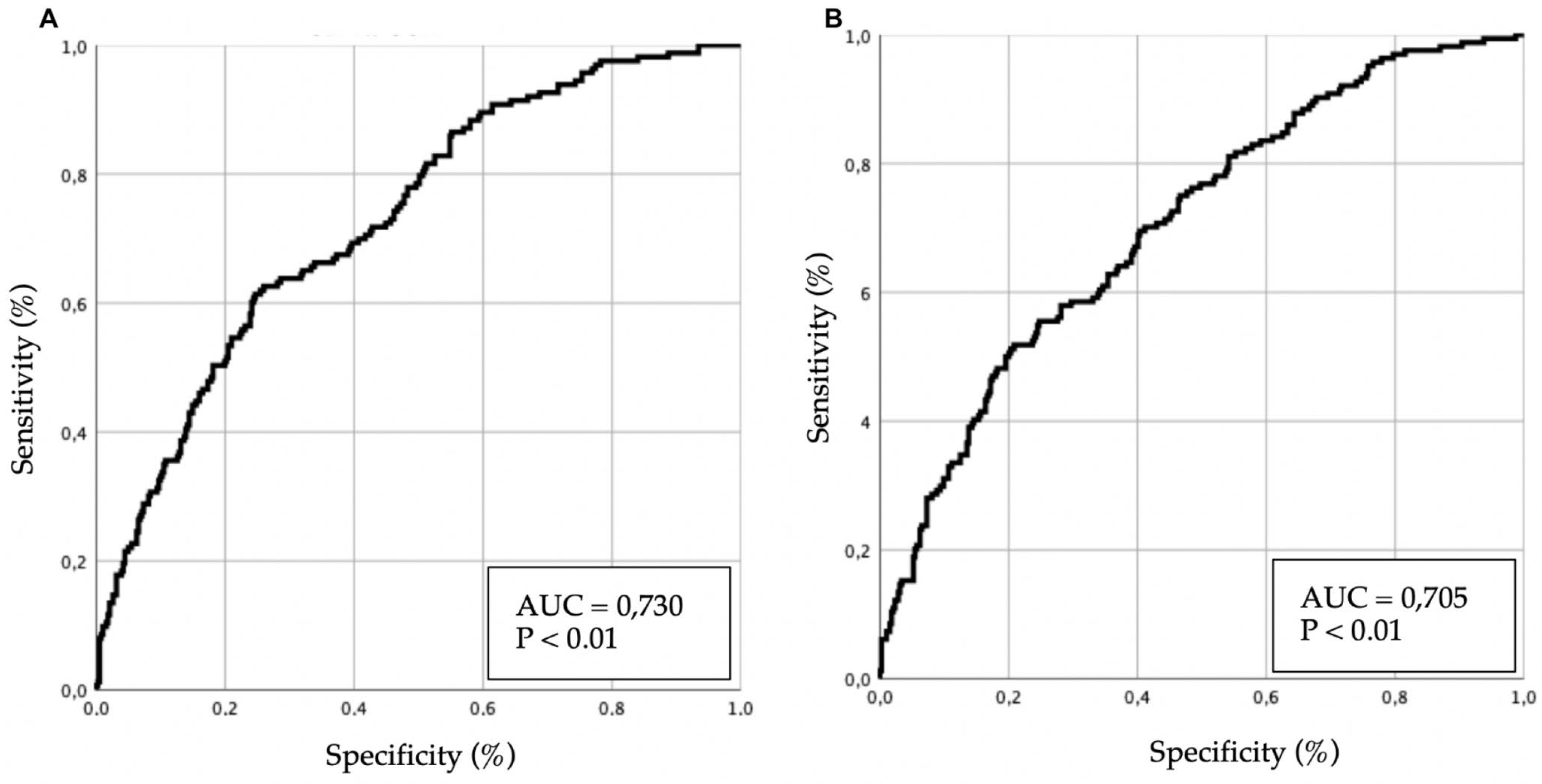

3.4.2. Multivariate Analysis of 12-Month Mortality

Several multivariate models were developed, and their results are presented in

Table 4. Predictive performance is illustrated in

Figure 3 (ROC curves).

In the 12-month analysis, age and previous episodes of AHF remained significantly associated with mortality, whereas valvular heart disease lost statistical significance. AF as a PF continued to show a trend toward a protective effect, although without reaching statistical significance.

Taken together, these findings highlight both shared and time-specific predictors of mortality. Age, NYHA functional class, and creatinine levels consistently emerged as significant prognostic factors across both short- and long-term follow-up. In contrast, ischemic heart disease, valvular heart disease, and ACS-related AHF were primarily associated with 30-day outcomes, while previous AHF episodes, hemoglobin levels, and post-episode hospital admission were more strongly linked to 12-month mortality.

4. Discussion

HF is a prevalent condition and one of the leading causes of hospitalization, with a significant impact on both patient quality of life and healthcare systems. In particular, AHF poses a clinical challenge due to its complexity and frequent need for hospital admission. Understanding the prognostic factors that influence its course is essential to optimize management and improve clinical outcomes, especially in older adults, where frailty and the coexistence of multiple comorbidities shape prognosis and therapeutic response.

Previous studies have shown that the prognostic factors of AHF vary significantly with age. In younger patients, cardiovascular determinants tend to predominate, whereas in older individuals, chronic comorbidities such as DM, ischemic heart disease, and renal disease carry greater prognostic weight [

34,

35,

36,

37]. These studies emphasize that age not only alters the prevalence of these conditions but also affects their clinical impact and interaction with decompensation mechanisms. In this context, the advanced mean age and high comorbidity burden of our cohort accurately reflect the profile of elderly patients with AHF treated in HED, reinforcing the validity of our findings within the geriatric setting.

Our cohort, with a mean age of 80.7 years and a high prevalence of comorbidities such as AF and ischemic heart disease, reflects the clinical profile reported by other hospitals participating in the EAHFE registry, as well as in national registries such as RICA [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The results confirm that various clinical and analytical factors are associated with increased mortality in AHF.

Age, dementia, and valvular heart disease emerged as consistent predictors across all follow-up periods, reinforcing the importance of comorbidities in risk stratification. In this context, advanced age functions not only as a biological marker but also as a clinical determinant that amplifies the impact of chronic conditions and PFs. Compared with large registries such as ADHERE [

43], OPTIMIZE-HF [

44], and ESC-HF-LT [

45], our cohort included older patients, in whom the prevalence and prognostic impact of comorbidities such as DM, ischemic heart disease, and dementia differ from those observed in younger populations. This finding is particularly relevant from a geriatric perspective, as age modifies the clinical expression of disease, alters therapeutic tolerance, and necessitates a multidimensional approach that integrates functional, cognitive, and social parameters. Age itself influences the expression and impact of these conditions, contributing to distinct clinical trajectories in older patients with AHF. Other comorbidities, such as a history of HF or prior hospitalization, showed prognostic relevance primarily in long-term follow-up, underscoring the need to differentiate the temporal impact of each variable.

Regarding clinical status at HED presentation, baseline NYHA functional class was a key prognostic determinant: class IV was associated with higher mortality at both 30 days and 1 year, while class III was linked only to long-term mortality. Hypoxemia and low-output symptoms at admission were associated with poorer 30-day outcomes but lost prognostic significance at 1 year. Similarly, the hypotensive form of AHF showed excess early mortality without long-term impact, consistent with studies on perfusion and cardiogenic shock [

46,

47]. These findings highlight the importance of considering the broader clinical context of elderly patients, in whom acute episodes represent only part of a chronic, evolving process marked by high physiological vulnerability [

48,

49].

PFs were identified in nearly 70% of patients, underscoring their high frequency and clinical relevance. Rapid AF was associated with lower long-term mortality, possibly reflecting better therapeutic response or a more favorable clinical phenotype [

13,

50,

51,

52]. An alternative explanation may be residual confounding related to baseline frailty or disease severity. In contrast, ACS was associated with higher mortality, particularly in the short term [

53,

54,

55]. These findings confirm that PFs not only trigger decompensation but also exert differentiated prognostic influence depending on the follow-up period. Infection did not reach statistical significance in our cohort, although it showed a similar trend consistent with previous studies [

56,

57]. Other PFs, such as atrial flutter, anemia, hypertensive crisis, or poor therapeutic adherence, were not significantly associated with mortality in our analysis. Although anemia and non-adherence have been identified as adverse prognostic indicators in other series [

58,

59], their lack of association in our study may be explained by sample size or specific population characteristics.

Among biomarkers, creatinine stood out as a robust predictor across all follow-up intervals, underscoring the role of renal function in AHF progression [

15]. In contrast, hemoglobin was associated with lower long-term mortality, suggesting that anemia may represent a modifiable factor, in line with recent evidence from studies such as ANEM-AHF [

60,

61]. In older patients, early identification and management of these biomarkers are particularly relevant, as they allow for tailored interventions aligned with physiological capacity and help reduce iatrogenesis from intensive treatments.

These findings reinforce the need to incorporate both comorbidities and PFs into the initial assessment. Current risk stratification models do not include PFs as prognostic variables [

62,

63,

64], despite their demonstrated value in our study. In elderly populations, a stratification model that integrates age, comorbidity, frailty, and PFs may enhance clinical decision-making, optimize hospital admissions, and guide interventions more proportionally to functional status and overall prognosis. Including these parameters alongside clinical variables may improve identification of high-risk patients and support more individualized management, enabling tailored therapies and follow-up strategies adapted to each patient’s clinical profile.

In conclusion, our results show that the prognostic impact of risk factors in AHF varies according to the temporal horizon, and that PFs play a relevant role that has often been underestimated. In elderly patients, this temporal approach is particularly important, as it allows for differentiation between determinants influencing the acute phase and those shaping chronic evolution. This framework adds value to risk stratification by identifying which patients require more intensive interventions during the acute phase and which need closer long-term follow-up. Future studies should focus on developing predictive models and therapeutic strategies specifically tailored to the geriatric population with AHF, integrating clinical, biological, and functional factors to support truly personalized care.

4.1. Study Limitations

This study presents several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, as it was conducted in a single hospital, extrapolation of the findings to other centers should be made with caution, given potential differences in emergency and inpatient care protocols. Second, it should be noted that, since the study is based on the EAHFE registry, it includes only patients treated in the HED, which may limit the comparability of our results with other registries, such as RICA, that are oriented toward patients hospitalized in Internal Medicine units.

In addition, the long follow-up period resulted in a substantial proportion of missing data for certain variables, particularly analytical parameters such as NT-proBNP and troponin, which were not available at our hospital during the initial years of data collection. The absence of these biomarkers may have affected the overall validity and accuracy of the predictive models. Similarly, it was not possible to include echocardiographic parameters, as echocardiography is not routinely performed in the HED. Some variables showed wide CI,, reflecting lower precision in the estimates due to the small number of events in certain categories, but were retained because of their clinical relevance and potential prognostic value.

Nevertheless, conducting the study in a single HED provided sample homogeneity and reduced variability in data collection and clinical management. Furthermore, since it was carried out in the emergency setting—the main gateway to the healthcare system—it yielded a broad and representative sample that strengthens the robustness of the findings and enables early identification of prognostic factors, which is essential for improving risk stratification and facilitating more efficient care transitions.

5. Conclusions

This study identified the main prognostic determinants of mortality in elderly patients hospitalized for AHF, emphasizing the added value of analyzing risk factors across distinct temporal horizons. Well-established predictors such as advanced age, valvular heart disease, and dementia consistently influenced outcomes throughout all follow-up periods. Other variables, including low-output symptoms, history of chronic HF, and baseline NYHA functional class, demonstrated prognostic relevance that varied depending on the time frame analyzed.

Importantly, PFs showed differentiated prognostic impact: ACS was associated with increased short-term mortality, whereas rapid AF emerged as a favorable marker during long-term follow-up.

These findings underscore the importance of incorporating the temporal dimension of prognostic determinants and integrating PFs into risk stratification models. Their inclusion in clinical decision-making may enhance the selection of candidates for intensive therapies, optimize hospitalization strategies, and strengthen continuity of care and long-term outcomes in older patients with AHF. From a geriatric perspective, it is essential to advance toward truly personalized management strategies that consider not only clinical parameters but also the functional, cognitive, and social status of each patient. This multidimensional approach may allow for tailored interventions, reduce unnecessary therapeutic burden, and improve quality of life in a highly vulnerable population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Baseline characteristics stratified by 30-day and 12-month mortality; Table S2: Univariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for 30-day mortality; Table S3: Univariate logistic regression analysis of risk factors for 12-month mortality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A.-V. and P.M.-C.; methodology, H.A.-V. and P.M.-C.; software, H.A.-V. and P.M.-C.; validation, H.A.-V.; formal analysis, P.M.-C.; investigation, H.A.-V., and I.O.-T.; resources, H.A.-V.; data curation, I.O.-T.; References writing—original draft preparation, I.O.-T.; writing—review and editing, I.O.-T., H.A.-V., and P.M.-C.; visualization, I.O.-T. and P.M.-C.; supervision, H.A.-V. and P.M.-C.; project administration, H.A.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975), revised in 2013, and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias on January 12, 2022, under project code CEImPA No. 2022.015. This approval covers the continued use of data collected during previous phases of the EAHFE registry. Additionally, the Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla obtained local ratification from the Ethics Committee of Cantabria (IDIVAL) on January 28, 2022, confirming that no further ethical review was required due to the existing national approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study for their participation in the registry and for follow-up contact, in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality and ethical restrictions. The information originates from the EAHFE registry and access is limited in accordance with current data protection regulations and the ethical agreements established by the relevant research committees.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACS |

Acute Coronary Syndrome |

| AF |

Atrial Fibrillation |

| AHF |

Acute Heart Failure |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| DM |

Diabetes Mellitus |

| EAHFE |

Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| HF |

Heart Failure |

| HED |

Hospital Emergency Department |

| HUMV |

Marqués de Valdecilla University Hospital |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| MRN |

Medical Record Number |

| NYHA |

New York Heart Association |

| NTproBNP |

N-terminal pro-B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| PF(s) |

Precipitating Factor(s) |

| RICA |

National Heart Failure Registry (Registro Nacional de Insuficiencia Cardiaca) |

| ROC |

Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; et al. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicras-Mainar, A.; Sicras-Navarro, A.; Palacios, B.; Varela, L.; Delgado, J.F. Epidemiology and treatment of heart failure in Spain: The HF-PATHWAYS study. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2022, 75, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.K.; Pinsky, J.L.; Kannel, W.B.; Levy, D. The epidemiology of heart failure: The Framingham Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1993, 22, 6A–13A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díez-Villanueva, P.; Alfonso, F. Heart failure in the elderly. J. Geriatr. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virani, S.S.; Alonso, A.; Aparicio, H.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Callaway, C.W.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e254–e743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortman, J.; Velkoff, V.; Hogan, H. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States; Population Estimates and Projections; U.S. Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Volume P25. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, A.; Carr, F.; Warriner, D. Cardiogeriatrics: The current state of the art. Heart 2024, 110, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Goodkind, D.; Kowal, P. An Aging World: 2015; U.S. Census Bureau: Suitland, MD, USA, 2016; Volume P95. [Google Scholar]

- West, L.; Cole, S.; Goodkind, D.; He, W. 65+ in the United States: 2010; U.S. Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Volume P23. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, C.; Palacios, B.; Gonzalez, V.; Gutiérrez, M.; Duong, M.; Chen, H.; et al. Evolution of Economic Burden of Heart Failure by Ejection Fraction in Newly Diagnosed Patients in Spain. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, G.Y.; Kremer, A.; Shochat, T.; Bental, T.; Korenfeld, R.; Abramson, E.; et al. The diversity of heart failure in a hospitalized population: The role of age. J. Card. Fail. 2012, 18, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comorbidities in heart failure: A key issue. Eur. J. Heart Fail. Suppl. 2009, 8 (Suppl. 1). [CrossRef]

- Ozierański, K.; Kapłon-Cieślicka, A.; Peller, M.; Tymińska, A.; Balsam, P.; Galas, M.; et al. Clinical characteristics and predictors of one-year outcome of heart failure patients with atrial fibrillation compared to heart failure patients in sinus rhythm. Kardiol. Pol. 2016, 74, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlay, S.M.; Givertz, M.M.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Chan, M.; Desai, A.S.; et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and heart failure: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2019, 140, e294–e324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Villanueva, P.; Jiménez-Méndez, C.; Pérez-Rivera, Á.; Barge Caballero, E.; López, J.; Ortiz, C.; et al. Different impact of chronic kidney disease in older patients with heart failure according to frailty. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 132, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorodeski, E.Z.; Goyal, P.; Hummel, S.L.; Krishnaswami, A.; Goodlin, S.J.; Hart, L.L.; et al. Domain management approach to heart failure in the geriatric patient: Present and future. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1921–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, E.; Lampert, B.C. Heart failure in older adults: Medical management and advanced therapies. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadziakiewicz, P.; Szczurek-Wasilewicz, W.; Szyguła-Jurkiewicz, B. Heart failure in elderly patients: Medical management, therapies and biomarkers. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Díez, M.P.; Llorens, P.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; Gil, V.; Jacob, J.; Herrero, P.; et al. Emergency Department Observation of Patients with Acute Heart Failure Prior to Hospital Admission: Impact on Short-Term Prognosis. Emergencias 2022, 34, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, Ò.; García Sarasola, A.; Fuenzalida, C.; Calderón, S.; Jacob, J.; Aguirre, A.; et al. Departments Involved during the First Episode of Acute Heart Failure and Subsequent Emergency Department Revisits and Rehospitalisations: An Outlook through the NOVICA Cohort. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 1231–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, F.; Martínez-Ibañez, L.; Pichler, G.; Ruiz, A.; Redon, J. Multimorbidity and Acute Heart Failure in Internal Medicine. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 232, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisado-Espartero, M.E.; Salamanca-Bautista, P.; Aramburu-Bodas, Ó.; Conde-Martel, A.; Arias-Jiménez, J.L.; Llàcer-Iborra, P.; et al. Heart Failure with Mid-Range Ejection Fraction in Patients Admitted to Internal Medicine Departments: Findings from the RICA Registry. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 255, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruigómez, A.; Michel, A.; Martín-Pérez, M.; García Rodríguez, L.A. Heart Failure Hospitalization: An Important Prognostic Factor for Heart Failure Re-Admission and Mortality. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 220, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisado-Espartero, M.E.; Salamanca-Bautista, P.; Aramburu-Bodas, Ó.; Manzano, L.; Quesada Simón, M.A.; Ormaechea, G.; et al. Causas de Muerte en Pacientes Hospitalizados en Servicios de Medicina Interna por Insuficiencia Cardíaca Según la Fracción de Eyección. Registro RICA. Med. Clin. (Barc) 2022, 158, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masip, J.; Formiga, F.; Comín-Colet, J.; Corbella, X. Short Term Prognosis of Heart Failure after First Hospital Admission. Med. Clin. (Barc) 2020, 154, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihara, Y.K.; Shiraishi, Y.; Kohsaka, S.; Nakano, S.; Nagatomo, Y.; Ono, T.; et al. Association of Pre-Hospital Precipitating Factors with Short- and Long-Term Outcomes of Acute Heart Failure Patients: A Report from the WET-HF2 Registry. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 389, 131161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, M.; Voors, A.A.; Girerd, N.; Billotte, M.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; et al. Heart Failure Etiologies and Clinical Factors Precipitating for Worsening Heart Failure: Findings from BIOSTAT-CHF. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 71, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Marcos, C.; Jacob, J.; Llorens, P.; Rodríguez, B.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; Herrera, S.; et al. Análisis de la efectividad y seguridad de las unidades de estancia corta en la hospitalización de pacientes con insuficiencia cardíaca aguda. Propensity Score UCE-EAHFE. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2022, 222, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, B.; Llorens, P.; Gil, V.; Rossello, X.; Jacob, J.; Herrero, P.; et al. Prognosis of acute heart failure based on clinical data of congestion. Rev. Clin. Esp. 2022, 222, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Marcos, C.; Espinosa, B.; Coloma, E.; San Inocencio, D.; Pilarcikova, S.; Guzmán-Martínez, S.; et al. Safety and efficiency of discharge to home hospitalization directly after emergency department care of patients with acute heart failure. Emergencias 2023, 35, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; Chapter 4, Model-Building Strategies and Methods for Logistic Regression; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 89–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe, J.M. Logistic Regression Models; Chapter 5, Model Development; Chapman & Hall/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; pp. 73–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ostolaza-Tazón, I.; Alonso-Valle, H.; Muñoz-Cacho, P. Identificación y prevalencia de factores precipitantes en la insuficiencia cardiaca aguda en un servicio de urgencias español y su pronóstico a corto y largo plazo. Rev. Esp. Urg. Emerg. 2025, 4, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamana, T.; Fujimoto, W.; Konishi, A.; Takemoto, M.; Kuroda, K.; Yamashita, S.; et al. Differences in Prognostic Factors among Patients Hospitalized for Heart Failure According to the Age Category: From the KUNIUMI Registry Acute Cohort. Intern. Med. 2022, 61, 3171–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.; Parenica, J.; Park, J.J.; Ishihara, S.; AlHabib, K.F.; Laribi, S.; et al. Clinical Presentation and Outcome by Age Categories in Acute Heart Failure: Results from an International Observational Cohort. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metra, M.; Mentz, R.J.; Chiswell, K.; Bloomfield, D.M.; Cleland, J.G.; Cotter, G.; et al. Acute Heart Failure in Elderly Patients: Worse Outcomes and Differential Utility of Standard Prognostic Variables. Insights from the PROTECT Trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp, J.; Shen, L.; Jhund, P.S.; Anand, I.S.; Carson, P.E.; Desai, A.S.; et al. Age-Related Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno-Miguel, A.; Gracia Gutiérrez, A.; Poblador-Plou, B.; Coscollar-Santaliestra, C.; Pérez-Calvo, J.I.; Divo, M.J.; et al. Multimorbidity Patterns in Patients with Heart Failure: An Observational Spanish Study Based on Electronic Health Records. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e033174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamana, T.; Fujimoto, W.; Konishi, A.; Takemoto, M.; Kuroda, K.; Yamashita, S.; et al. Differences in Prognostic Factors among Patients Hospitalized for Heart Failure According to the Age Category: From the KUNIUMI Registry Acute Cohort. Intern. Med. 2022, 61, 3171–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, K.; Minamisawa, M.; Motoki, H.; Teramoto, K.; Okuma, Y.; Kanai, M.; et al. Clinical Profile and Prognosis of Dementia in Patients with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: From the CURE-HF Registry. Circ. J. 2023, 88, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollenberg, S.M.; Warner Stevenson, L.; Ahmad, T.; Amin, V.J.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; et al. 2019 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Risk Assessment, Management, and Clinical Trajectory of Patients Hospitalized with Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1966–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miró, Ò.; Conde-Martel, A.; Llorens, P.; Salamanca-Bautista, P.; Gil, V.; González-Franco, Á.; et al. The Influence of Comorbidities on the Prognosis after an Acute Heart Failure Decompensation and Differences According to Ejection Fraction: Results from the EAHFE and RICA Registries. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 111, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonarow, G.C.; Heywood, J.T.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Lopatin, M.; Yancy, C.W.; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. Temporal Trends in Clinical Characteristics, Treatments, and Outcomes for Heart Failure Hospitalizations, 2002 to 2004: Findings from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE). Am. Heart J. 2007, 153, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonarow, G.C.; Abraham, W.T.; Albert, N.M.; Gattis, W.A.; Gheorghiade, M.; Greenberg, B.; O’Connor, C.M.; Yancy, C.W.; Young, J. Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF): Rationale and Design. Am. Heart J. 2004, 148, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Anker, S.D.; Maggioni, A.P.; Coats, A.J.; Filippatos, G.; Ruschitzka, F.; Ferrari, R.; Piepoli, M.F.; Delgado Jimenez, J.F.; Metra, M.; et al.; Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-Year Follow-Up Outcomes and Differences across Regions. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossello, X.; Bueno, H.; Gil, V.; Jacob, J.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; Llorens, P.; et al. Synergistic Impact of Systolic Blood Pressure and Perfusion Status on Mortality in Acute Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2021, 14, e007347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, C.P.; Sideris, K.; Taleb, I.; Maneta, E.; Hamouche, R.; Tseliou, E.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Suffering Acute Decompensated Heart Failure Complicated by Cardiogenic Shock. Circ. Heart Fail. 2024, 17, e011358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.B.; Lippmann, S.J.; DiBello, J.R.; Gorsh, B.; Curtis, L.H.; Sikirica, V.; et al. The Burden of Congestion in Patients Hospitalized with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 2019, 124, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, J.; Formiga, F.; Corbella, X.; Conde-Martel, A.; Llácer, P.; Álvarez Rocha, P.; et al. De Novo Acute Heart Failure: Clinical Features and One-Year Mortality in the Spanish Nationwide Registry of Acute Heart Failure. Med. Clin. (Barc) 2019, 152, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafrir, B.; Lund, L.H.; Laroche, C.; Ruschitzka, F.; Crespo-Leiro, M.G.; Coats, A.J.S.; et al. Prognostic Implications of Atrial Fibrillation in Heart Failure with Reduced, Mid-Range, and Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Report from 14,964 Patients in the European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 4277–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, M.K.; Park, J.J.; Lim, N.K.; Kim, W.H.; Choi, D.J. Impact of Atrial Fibrillation in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced, Mid-Range or Preserved Ejection Fraction. Heart 2020, 106, 1160–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rewiuk, K.; Wizner, B.; Fedyk-Łukasik, M.; Zdrojewski, T.; Opolski, G.; Dubiel, J.; et al. Epidemiology and management of coexisting heart failure and atrial fibrillation in an outpatient setting. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2011, 121, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, N.P.; Clare, R.M.; Harrington, J.L.; Badjatiya, A.; Wojdyla, D.M.; Udell, J.A.; et al. Morbidity and Mortality Associated with Heart Failure in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Pooled Analysis of 4 Clinical Trials. J. Card. Fail. 2023, 29, 1603–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, Ò.; Rossello, X.; Gil, V.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; Llorens, P.; Herrero-Puente, P.; et al. Predicting 30-Day Mortality for Patients with Acute Heart Failure in the Emergency Department: A Cohort Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 167, 698–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, J.; Martín-Sanchez, F.J.; Herrero, P.; Miró, Ò.; Llorens, P. Valor Pronóstico de la Troponina en Pacientes con Insuficiencia Cardiaca Aguda Atendidos en los Servicios de Urgencias Hospitalarios Españoles: Estudio TROPICA (TROPonina en Insuficiencia Cardiaca Aguda). Med. Clin. (Barc) 2013, 140, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, M.; Gayat, E.; Parenica, J.; Ishihara, S.; Zhang, J.; Choi, D.J.; et al. Precipitating Factors and 90-Day Outcome of Acute Heart Failure: A Report from the Intercontinental GREAT Registry. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Lin, H.W.; Lin, S.H.; Li, Y.H. Impact of Infection-Related Admission in Patients with Heart Failure: A 10 Years National Cohort Study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, S.W.; Ashok, T.; Patni, N.; Fatima, M.; Lamis, A.; Anne, K.K. Anemia and Heart Failure: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e27167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, N.; Johnson, J.; Patel, V.; Pekmezaris, R.; Seepersaud, H.; Kumar, P.; et al. Understanding Social Risk Factors in Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department for Acute Heart Failure: A Pilot Study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 84, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Los Ángeles Fernández-Rodríguez, M.; Prieto-García, B.; Vázquez-Álvarez, J.; Jacob, J.; Gil, V.; Miró, O.; et al. Prognostic Implications of Anemia in Patients with Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments: ANEM-AHF Study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e13712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berge, J.C.; Constantinescu, A.A.; van Domburg, R.T.; Brankovic, M.; Deckers, J.W.; Akkerhuis, K.M. Renal Function and Anemia in Relation to Short- and Long-Term Prognosis of Patients with Acute Heart Failure in the Period 1985–2008: A Clinical Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.P.; Jenkins, C.A.; Harrell, F.E.; Liu, D.; Miller, K.F.; Lindsell, C.J.; et al. Identification of Emergency Department Patients with Acute Heart Failure at Low Risk for 30-Day Adverse Events. JACC Heart Fail. 2015, 3, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiell, I.G.; Clement, C.M.; Brison, R.J.; Rowe, B.H.; Borgundvaag, B.; Aaron, S.D.; et al. A Risk Scoring System to Identify Emergency Department Patients with Heart Failure at High Risk for Serious Adverse Events. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2013, 20, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Acute Heart Failure Syndromes. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Evaluation and Management of Adult Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department with Acute Heart Failure Syndromes: Approved by ACEP Board of Directors, June 23, 2022. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2022, 80, e31–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).