Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

13 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

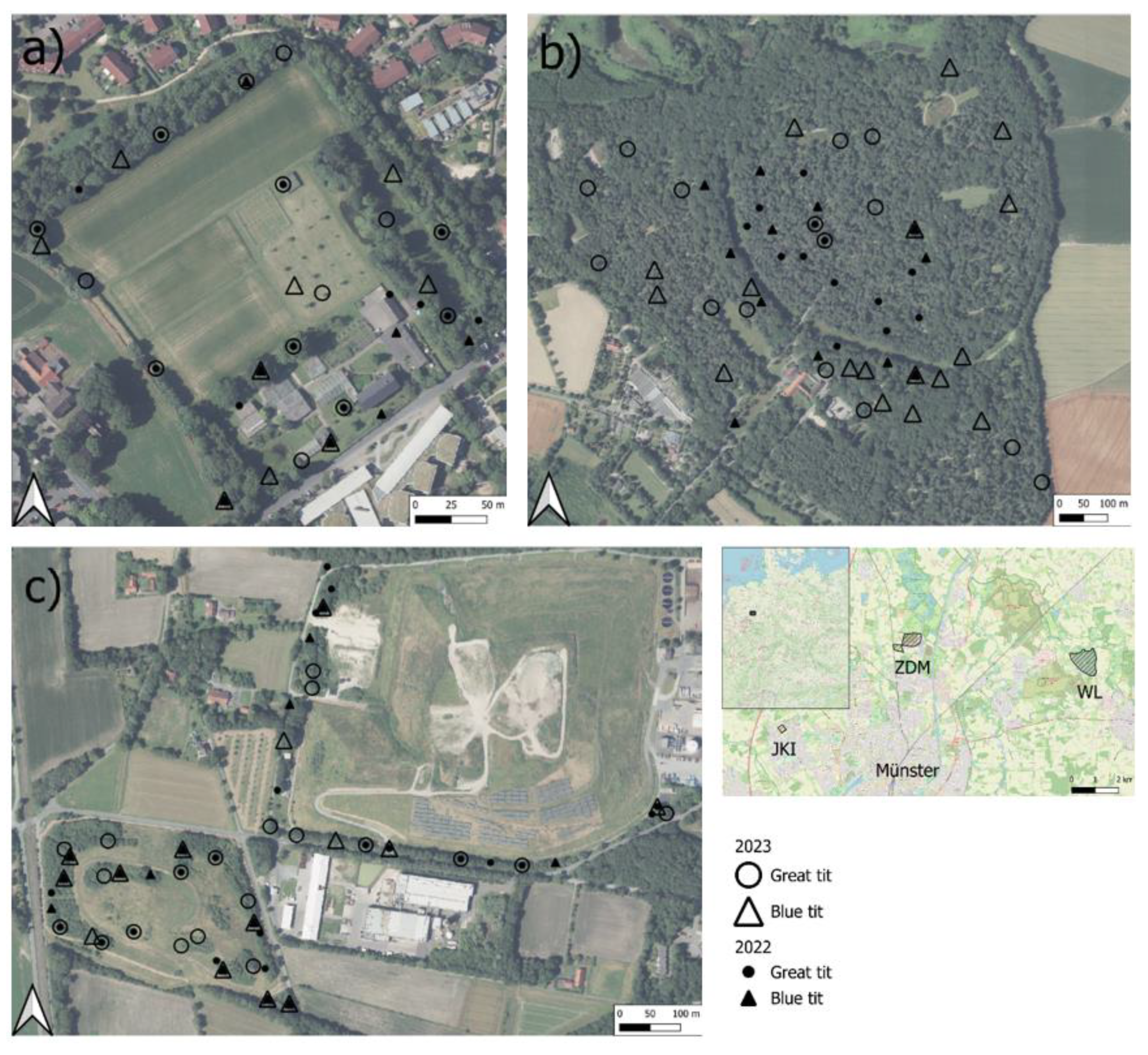

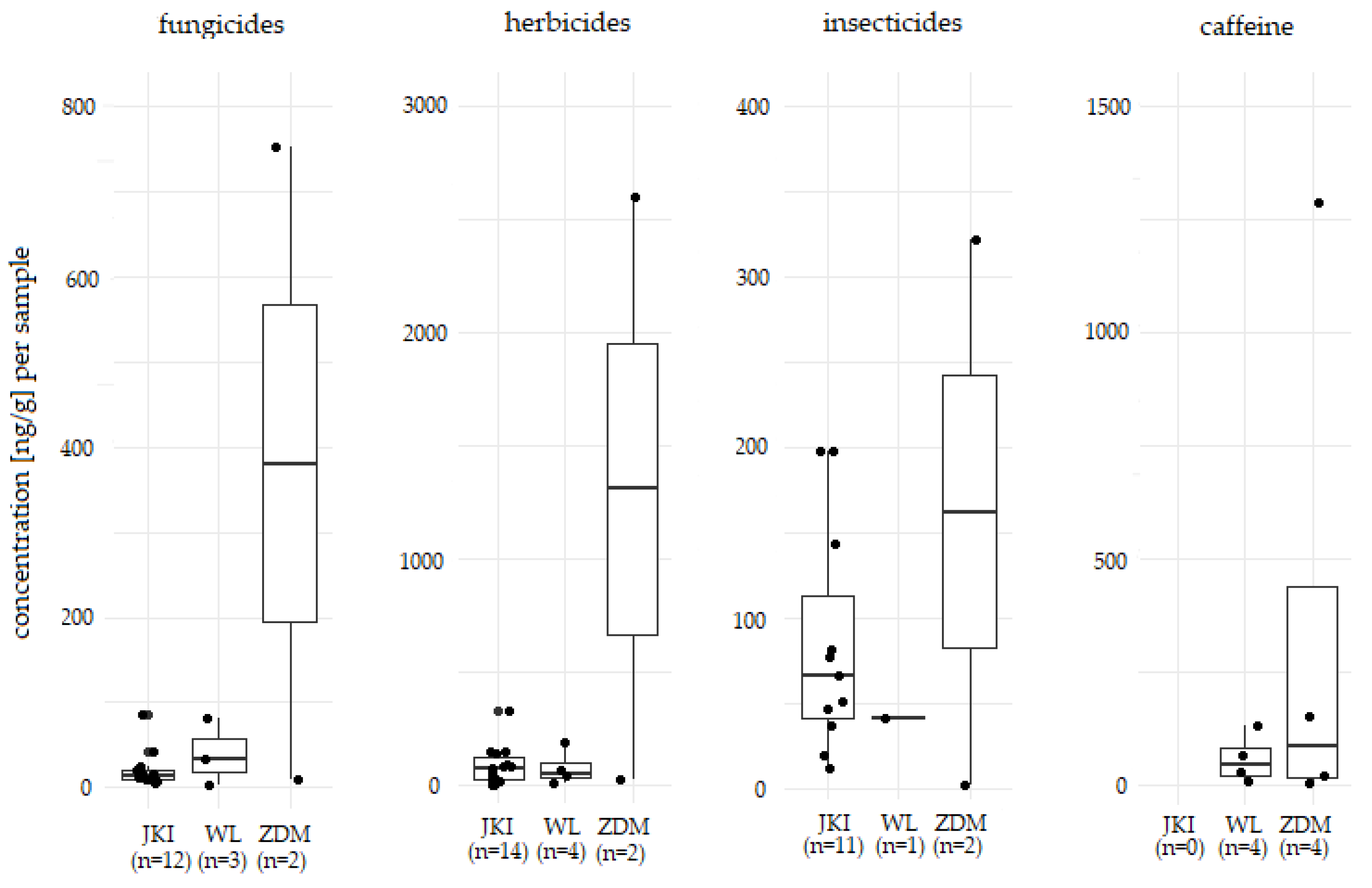

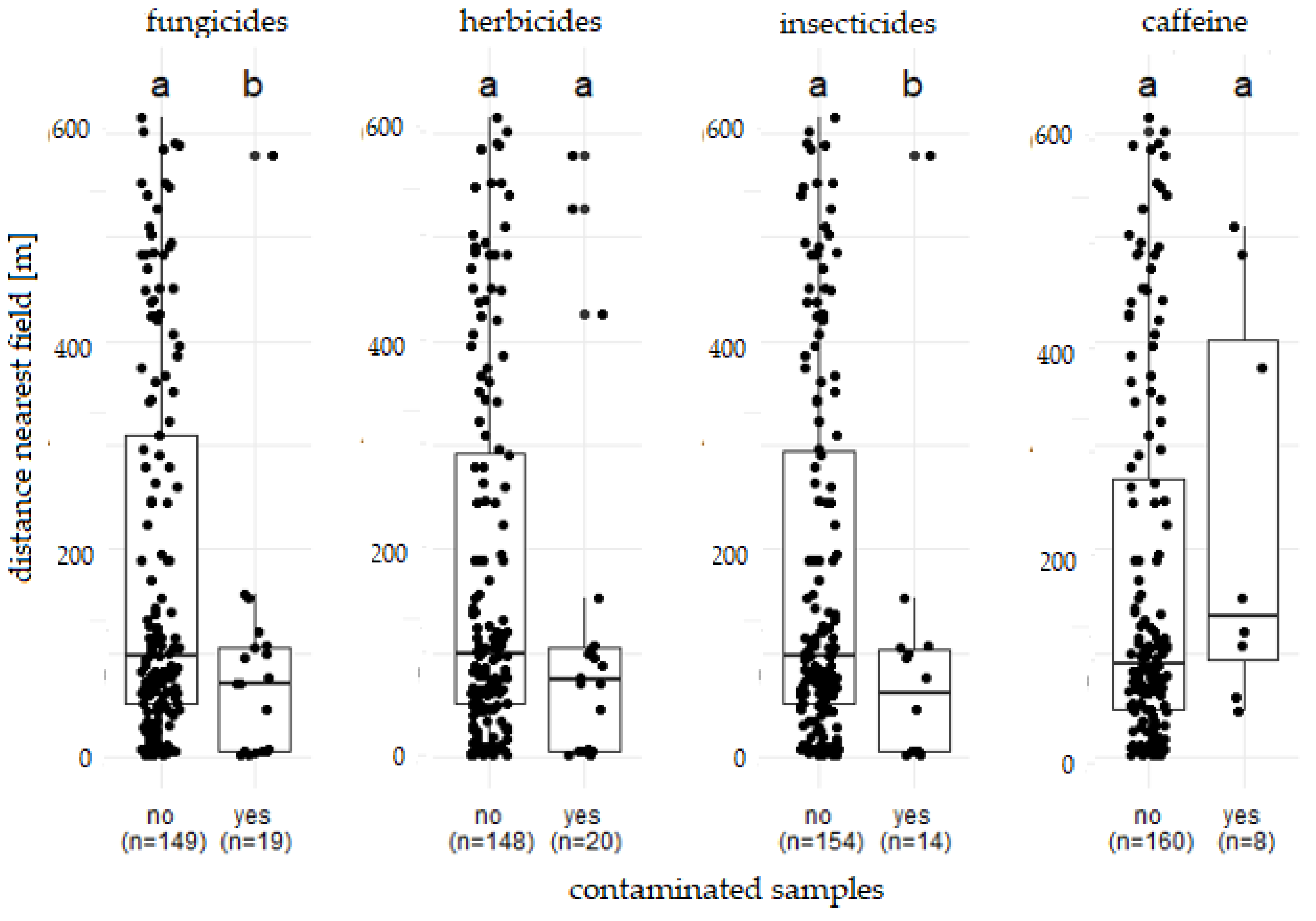

Pesticides remain among the most significant threats to biodiversity and natural ecosystems. Non-invasive methods, such as the analysis of bird faeces, have shown great potential for detecting pesticide exposure. In this study with a new approach, we analysed faecal sacs from nestlings of Blue tits (Cyanistes caeruleus) and Great tits (Parus major) to gain deeper insights into pesticide contamination during the breeding period. Samples were collected from three distinct sites near Münster, Germany. In total, we detected 65 substances from 57 different pesticides, as well as caffeine, with pesticides present in 16.07% of the 168 samples. Concentrations varied between species and sites and were higher for fungicides and insecticides in nests located closer to agricultural fields. While no direct effects on reproductive success were found, our results underscore the potential of faecal sac analysis as a valuable tool for spatially resolved pesticide monitoring. Importantly, we show that pesticide exposure also occurs in in nestlings and birds breeding outside of intensive farmland. To better understand the ecological consequences, future studies should incorporate environmental variables and conduct a separate analysis of urate and faeces of feacal sacs to precisely determine concentrations.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Sampling

Substance analysis

Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Residues in Blue and Great tits

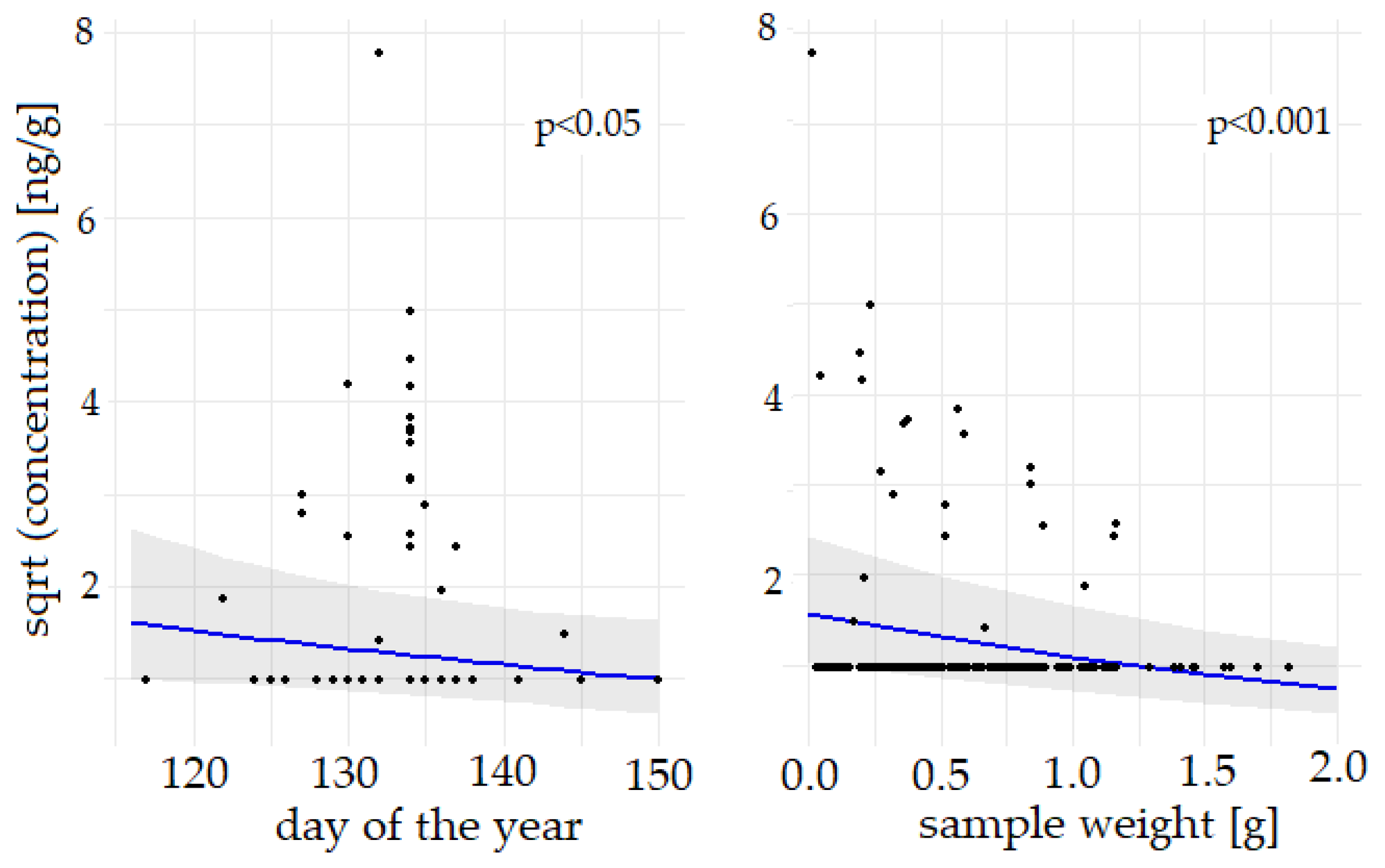

3.2. Influencing factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Residues in Blue and Great tits

4.2. Influencing factors

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

References

- Díaz, S.; Settele, J.; Brondízio, E.S.; Ngo, H.T.; Agard, J.; Arneth, A.; Balvanera, P.; Brauman, K.A.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Chan, K.M.A.; et al. Pervasive Human-Driven Decline of Life on Earth Points to the Need for Transformative Change. Science 2019, 366, eaax3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Ryo, M.; Lehmann, A. Classifying Human Influences on Terrestrial Ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 2273–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavanja, M.C.R. Introduction: Pesticides Use and Exposure, Extensive Worldwide. Rev. Environ. Health 2009, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Md Meftaul, I.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Dharmarajan, R.; Annamalai, P.; Megharaj, M. Pesticides in the Urban Environment: A Potential Threat That Knocks at the Door. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 134612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruse-Plaß, M.; Hofmann, F.; Wosniok, W.; Schlechtriemen, U.; Kohlschütter, N. Pesticides and Pesticide-Related Products in Ambient Air in Germany. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojiri, A.; Zhou, J.L.; Robinson, B.; Ohashi, A.; Ozaki, N.; Kindaichi, T.; Farraji, H.; Vakili, M. Pesticides in Aquatic Environments and Their Removal by Adsorption Methods. Chemosphere 2020, 253, 126646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.; Gai, L.; Harkes, P.; Tan, G.; Ritsema, C.J.; Alcon, F.; Contreras, J.; Abrantes, N.; Campos, I.; Baldi, I.; et al. Pesticide Residues with Hazard Classifications Relevant to Non-Target Species Including Humans Are Omnipresent in the Environment and Farmer Residences. Environ. Int. 2023, 181, 108280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassin De Montaigu, C.; Goulson, D. Identifying Agricultural Pesticides That May Pose a Risk for Birds. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brühl, C.A.; Bakanov, N.; Köthe, S.; Eichler, L.; Sorg, M.; Hörren, T.; Mühlethaler, R.; Meinel, G.; Lehmann, G.U.C. Direct Pesticide Exposure of Insects in Nature Conservation Areas in Germany. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, C.A.; Foppen, R.P.B.; Van Turnhout, C.A.M.; De Kroon, H.; Jongejans, E. Declines in Insectivorous Birds Are Associated with High Neonicotinoid Concentrations. Nature 2014, 511, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigal, S.; Dakos, V.; Alonso, H.; Auniņš, A.; Benkő, Z.; Brotons, L.; Chodkiewicz, T.; Chylarecki, P.; De Carli, E.; Del Moral, J.C.; et al. Farmland Practices Are Driving Bird Population Decline across Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120, e2216573120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, A.P. Parallel Declines in Abundance of Insects and Insectivorous Birds in Denmark over 22 Years. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 6581–6587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, C.J.; Wenny, D.G.; Marquis, R.J. Ecosystem Services Provided by Birds. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1134, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, J.E.G.; Fernie, K.J. Avian Wildlife as Sentinels of Ecosystem Health. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 36, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagi, T.; Fujisawa, T. Acute Toxicity and Metabolism of Pesticides in Birds. J. Pestic. Sci. 2021, 46, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badry, A.; Schenke, D.; Treu, G.; Krone, O. Linking Landscape Composition and Biological Factors with Exposure Levels of Rodenticides and Agrochemicals in Avian Apex Predators from Germany. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, E.; Gaffard, A.; Rodrigues, A.; Millet, M.; Bretagnolle, V.; Moreau, J.; Monceau, K. Neonicotinoids: Still Present in Farmland Birds despite Their Ban. Chemosphere 2023, 321, 138091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelier, F.; Prouteau, L.; Brischoux, F.; Chastel, O.; Devier, M.-H.; Le Menach, K.; Martin, S.; Mohring, B.; Pardon, P.; Budzinski, H. High Contamination of a Sentinel Vertebrate Species by Azoles in Vineyards: A Study of Common Blackbirds (Turdus Merula) in Multiple Habitats in Western France. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 316, 120655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esther, A.; Schenke, D.; Heim, W. Noninvasively Collected Fecal Samples as Indicators of Multiple Pesticide Exposure in Wild Birds. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2022, 41, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, H.Q.P.; Baillie, S.R.; Leech, D.I. The UK Nest Record Scheme: Its Value for Science and Conservation. Bird Study 2003, 50, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Cerda, F.; Bohannan, B.J.M. The Nidobiome: A Framework for Understanding Microbiome Assembly in Neonates. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2020, 35, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilman, H.; Belmaker, J.; Simpson, J.; De La Rosa, C.; Rivadeneira, M.M.; Jetz, W. EltonTraits 1.0: Species-level Foraging Attributes of the World’s Birds and Mammals: Ecological Archives E095-178. Ecology 2014, 95, 2027–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Álamo, J.D.; Rubio, E.; Soler, J.J. Evolution of Nestling Faeces Removal in Avian Phylogeny. Anim. Behav. 2017, 124, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eeva, T.; Raivikko, N.; Espín, S.; Sánchez-Virosta, P.; Ruuskanen, S.; Sorvari, J.; Rainio, M. Bird Feces as Indicators of Metal Pollution: Pitfalls and Solutions. Toxics 2020, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santema, P.; Kempenaers, B. Complete Brood Failure in an Altricial Bird Is Almost Always Associated with the Sudden and Permanent Disappearance of a Parent. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, F.-J.; Southern, I.; Gigauri, M.; Bellini, G.; Rojas, O.; Runde, A. Warning on Nine Pollutants and Their Effects on Avian Communities. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 32, e01898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Peñuela, J.; Santamaría-Cervantes, C.; Fernández-Vizcaíno, E.; Mateo, R.; Ortiz-Santaliestra, M.E. Integrating Adverse Effects of Triazole Fungicides on Reproduction and Physiology of Farmland Birds. J. Avian Biol. 2024, e03313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Santos, F.; Dingemanse, N.J. Weather Effects on Nestling Survival of Great Tits Vary According to the Developmental Stage. J. Avian Biol. 2020, 51, jav.02421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, S.; Van Noordwijk, A.J.; Álvarez, E.; Barba, E. A Recipe for Postfledging Survival in Great Tits Parus Major : Be Large and Be Early (but Not Too Much). Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 4458–4467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Breeding Bird Atlas; European bird census council, Ed.; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, 2020; ISBN 978-84-16728-38-1.

- Grüneberg, C.; Nordrhein-Westfälische Ornithologengesellschaft Die Brutvögel Nordrhein-Westfalens; 1. unveränd. Nachdruck.; LWL-Museum für Naturkunde: Münster, 2014; ISBN 978-3-940726-24-7.

- Odderskær, P.; Sell, H. Survival of Great Tit (Parus Major) Nestlings in Hedgerows Exposed to a Fungicide and an Insecticide: A Field Experiment. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1993, 45, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.A.; Peris, S.J. Effects of Forest Spraying with Two Application Rates of Cypermethrin on Food Supply and on Breeding Success of the Blue Tit ( Parus Caeruleus ). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1992, 11, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.A. No Effects of a Forest Spraying of Malathion on Breeding Blue Tits ( Parus Caeruleus ). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1994, 13, 1127–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonneris, E.; Gao, Z.; Prosser, A.; Barfknecht, R. Selecting Appropriate Focal Species for Assessing the Risk to Birds from Newly Drilled Pesticide-treated Winter Cereal Fields in France. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2019, 15, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamonica, D.; Charvy, L.; Kuo, D.; Fritsch, C.; Coeurdassier, M.; Berny, P.; Charles, S. A Brief Review on Models for Birds Exposed to Chemicals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Open Street Map contributors Map Data for Muenster 2025.

- Minot, E.O.; Perrins, C.M. Interspecific Interference Competition--Nest Sites for Blue and Great Tits. J. Anim. Ecol. 1986, 55, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- italic>Methodenstandards zur Erfassung der Brutvögel Deutschlands; Südbeck, P., Ed.; DDA Verlag: Steckby, 2005; ISBN 978-3-00-015261-0.

- Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas. Teil 4,[1]: Passeriformes Muscicapidae—Paridae. In; Haffer, J., Glutz von Blotzheim, U.N., Niethammer, G., Eds.; Aula-Verl: Wiesbaden, 1993 ISBN 978-3-89104-022-5.

- Südbeck, P.; Andretzke, H.; Fischer, S.; Gedeon, K.; Pertl, C.; Linke, T.J.; Georg, M.; König, C.; Schikore, T.; Schröder, K.; et al. Methodenstandards zur Erfassung der Brutvögel Deutschlands; 1. überarbeitete Auflage.; Eigenverlag DDA: Münster, 2025; ISBN 978-3-9819703-3-3. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas, N.B.; Henry, P.F.P.; Binkowski, Ł.J.; Hladik, M.L.; Gross, M.S.; Schroeder, M.A.; Davis, D.M. Persistence of Pesticide Residues in Weathered Avian Droppings. Environ. Res. 2024, 259, 119475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Environment Agency Corine Land Cover Change CLC+ Backbone 2018 (Raster 10 m), Europe, 3-Yearly, Feb. 2023 2023.

- QGIS Development Team QGIS Geographic Information System, Version 3. 34.6 2024.

- Naef-Daenzer, B. Patch Time Allocation and Patch Sampling by Foraging Great and Blue Tits. Anim. Behav. 2000, 59, 989–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comité Européen de Normalisation DIN EN 15662:2018-07, Pflanzliche Lebensmittel_- Multiverfahren Zur Bestimmung von Pestizidrückständen Mit GC Und LC Nach Acetonitril-Extraktion/Verteilung Und Reinigung Mit Dispersiver SPE_- Modulares QuEChERS-Verfahren; Deutsche Fassung EN_15662:2018; 2018. [CrossRef]

- Trau, F.N.; Fisch, K.; Lorenz, S. Habitat Type Strongly Influences the Structural Benthic Invertebrate Community Composition in a Landscape Characterized by Ubiquitous, Long-Term Agricultural Stress. Inland Waters 2023, 13, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umweltbundesamt Umsetzung Des Nationalen Aktionsplans Zur Nachhaltigen Anwendung von Pestiziden Teil 2: Konzeption Eines Repräsentativen Monitorings Zur Belastung von Kleingewässern in Der Agrarlandschaft; Dessau-Roßlau, 2019.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2024.

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package 2001, 2.6-10.

- Brooks, M., E.; Kristensen, K.; Benthem, K., J.; van; Magnusson, A.; Berg, C., W.; Nielsen, A.; Skaug, H., J.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B., M. glmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-Inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. R J. 2017, 9, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdecke, D. Ggeffects: Create Tidy Data Frames of Marginal Effects for “ggplot” from Model Outputs 2017, 2.0.0.

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Use R!; Second edition.; Springer international publishing: Cham, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sabin, L.B.; Mora, M.A. Ecological Risk Assessment of the Effects of Neonicotinoid Insecticides on Northern Bobwhites ( Colinus Virginianus ) in the South Texas Plains Ecoregion. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2021, 18, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, M.L.; Stutchbury, B.J.M.; Morrissey, C.A. A Neonicotinoid Insecticide Reduces Fueling and Delays Migration in Songbirds. Science 2019, 365, 1177–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.A.; Tzilivakis, J.; Warner, D.J.; Green, A. An International Database for Pesticide Risk Assessments and Management. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2016, 22, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.S.; Bean, T.G.; Hladik, M.L.; Rattner, B.A.; Kuivila, K.M. Uptake, Metabolism, and Elimination of Fungicides from Coated Wheat Seeds in Japanese Quail ( Coturnix Japonica ). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1514–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K.E.; Ramsay, S.L.; Henderson, L.; Larcombe, S.D. Seasonal Variation in Diet Quality: Antioxidants, Invertebrates and Blue Tits Cyanistes Caeruleus: ANTIOXIDANTS IN INVERTEBRATES AND CHICKS. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2010, 99, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Navas, V.; Ferrer, E.S.; Sanz, J.J. Prey Selectivity and Parental Feeding Rates of Blue Tits Cyanistes Caeruleus in Relation to Nestling Age. Bird Study 2012, 59, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Davies, E.; Sanz, J.J. Habitat Structure Modulates Nestling Diet Composition and Fitness of Blue Tits Cyanistes Caeruleus in the Mediterranean Region. Bird Study 2017, 64, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadra, G.R.; Paranaíba, J.R.; Vilas-Boas, J.; Roland, F.; Amado, A.M.; Barros, N.; Dias, R.J.P.; Cardoso, S.J. A Global Trend of Caffeine Consumption over Time and Related-Environmental Impacts. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; He, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Hu, X. Risks of Caffeine Residues in the Environment: Necessity for a Targeted Ecopharmacovigilance Program. Chemosphere 2020, 243, 125343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamely, M.; Karimi Torshizi, M.A.; West, J.; Niewold, T. Impacts of Caffeine on Resistant Chicken’s Performance and Cardiovascular Gene Expression. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 106, 566–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamely, M.; Torshizi, M.A.K.; Rahimi, S.; Wideman, R.F. Caffeine Causes Pulmonary Hypertension Syndrome (Ascites) in Broilers. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedghi, S.; Mosleh, N.; Shomali, T.; Dabiri, S.A.H. A Study on Acute Oral Caffeine Intoxication and Its Treatment Strategies in Domestic Pigeons Columba Livia Domestica). Vet. Res. Forum 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzan, M.B.; Weinstein, B.G.; Grasty, M.R.; Kohrn, B.F.; Hendrickson, E.C.; Arredondo, T.M.; Thompson, P.G. Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (micro-UAVs, Drones) in Plant Ecology. Appl. Plant Sci. 2016, 4, 1600041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, P.O.; Benediktsson, J.A.; Sveinsson, J.R. Random Forests for Land Cover Classification. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, M.M. The Food of Titmice in Oak Woodland. J. Anim. Ecol. 1955, 24, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landesbetrieb Information und Technik Nordrhein Westfalen Ackerland Der Landwirtschaftlichen Betriebe in NRW Nach Kulturarten 2022 Und 2023 (Ergebnisse Für Regierungsbezirke); Düsseldorf, 2023.

- Bouvier, J.-C.; Delattre, T.; Boivin, T.; Musseau, R.; Thomas, C.; Lavigne, C. Great Tits Nesting in Apple Orchards Preferentially Forage in Organic but Not Conventional Orchards and in Hedgerows. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 337, 108074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassin De Montaigu, C.; Glauser, G.; Guinchard, S.; Goulson, D. High Prevalence of Veterinary Drugs in Bird’s Nests. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 964, 178439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Blue tit (n=73) | Great tit (n=95) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| substance | det. Freq. (%) | median (ng/g) | max (ng/g) | det. Freq (%) |

median (ng/g) | max (ng/g) |

| Caffeine | 6.85 | 65.71 | 152.45 | 3.16 | 19.41 | 1287.70 |

| Carbendazim, fungicide | 5.48 | 5.48 | 9.63 | 8.42 | 6.07 | 15.02 |

| Chlorantraniliprole, insecticide | 4.11 | 19.60 | 21.69 | 7.37 | 11.11 | 44.72 |

| Chloridazon, herbicide | 1.37 | 1.89 | 1.89 | 6.32 | 12.03 | 31.93 |

| Diflufenican, herbicide | 4.11 | 8.76 | 14.18 | 5.26 | 2.46 | 89.85 |

| Dimefuron, herbicide | 5.48 | 12.46 | 25.61 | 10.53 | 5.80 | 208.92 |

| Diuron, herbicide | 4.11 | 8.04 | 17.14 | 4.21 | 4.49 | 207.23 |

| Fenuron, herbicide | 2.74 | 13.43 | 20.92 | 5.26 | 4.20 | 11.33 |

| Fluopicolide, fungicide | 5.48 | 11.17 | 36.38 | 6.32 | 2.65 | 135.70 |

| Flupyrsulfuron-methyl, herbicide | 4.11 | 35.34 | 74.18 | 7.37 | 30.86 | 92.36 |

| Foramsulfuron, herbicide | 4.11 | 1.96 | 31.67 | 1.05 | 5.49 | 5.49 |

| Imidacloprid, insecticide | 1.37 | 3.04 | 3.04 | 3.16 | 1.42 | 18.11 |

| Methiocarb, insecticide | 4.11 | 55.19 | 111.53 | 7.37 | 27.20 | 111.19 |

| Prosulfuron, herbicide | 1.37 | 1.94 | 1.94 | 6.32 | 4.53 | 171.08 |

| Terbuthylazine-2-hydroxy-desethyl, herbicide | 2.74 | 5.66 | 6.22 | 3.16 | 12.45 | 140.46 |

| Terbuthylazine-desethyl, herbicide | 4.11 | 7.60 | 31.04 | 5.26 | 9.11 | 134.92 |

| Thiacloprid, insecticide | 2.74 | 18.27 | 26.53 | 6.32 | 10.55 | 36.22 |

| Thiacloprid-Amid, insecticide | 4.11 | 16.43 | 40.90 | 8.42 | 5.02 | 206.46 |

| Zoxamide, fungicide | 4.11 | 6.84 | 7.88 | 6.32 | 6.90 | 14.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).