1. Introduction

Elastin is an essential extracellular matrix protein in all jawed vertebrates by providing extensibility and elastic recoil in various organs like blood vessels, skin, lungs and ligaments. The elastin fibers consist of a microfibrillar mantle surrounding the insoluble elastin core, which is formed by self-assembly of the soluble tropoelastin monomers (onwards named elastin) followed by covalent crosslinking of the elastin aggregates [

1,

2]. The extreme hydrophobicity together with the multiple crosslinks are pivotal for the insolubility, proteolytic resistance, and exceptional stability and longevity of elastin with a half-time of about 70 years in man [

2,

3]. The elastin protein consists of alternating hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains, which usually correspond to the individual exons in the genetic sequence [

4]. The hydrophobic domains interact in the self-assembly, or coacervation, process and are particularly rich in non-polar amino acids typically occurring in repeated motifs [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The hydrophilic cross-linking domains are subdivided into KA and KP types, which consist of alanine and proline residues, respectively, between pairs of lysine and form highly stable crosslinks by the action of lysyl oxidases [

4,

9,

10]. The KA and KP types can be covalently crosslinked with each other, and substitution of KP for KA crosslinks had little effect on the tensile mechanical properties of elastin-like proteins[

10,

11]. The conserved C-terminal end contains a tetrabasic motif and a cysteine pair of importance for the interactions with other matrix components [

12,

13,

14].

The elasticity of blood vessels is crucial for smoothing the pulsatile blood flow generated by the heart to provide continuous perfusion of peripheral tissues [

15]. The large amounts of elastin fibres in the aortic wall create the arterial elasticity below and at physiological pressure, while the collagen fibres provide arterial stiffness to withstand the force of high blood flow [

16]. The expanding energy from the blood pressure is temporarily stored in the elastic arteries when the walls are stretched during the systolic phase and is returned to the blood flow when the elastin recoils during diastole [

17]. This “Windkessel” effect also occurs in the elastic bulbus arteriosus of the teleost heart acting as an damping chamber to provide a more even flow through the gill lamellae for efficient gas exchange and for protecting the delicate gill capillaries [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. The bulbus likely emerged in teleosts after the whole genome duplication about 300 million years ago, and the subsequent divergence of the duplicated

eln genes resulted in the neofunctionalization of ElnB [

23,

24]. This paralog is predominantly expressed in the bulbus and plays a key role in the development of the bulbus by promoting the differentiation of cardiac precursor cells into smooth muscle [

24]. ElnB was recently shown to confer the uniquely low stiffness of the bulbus in zebrafish, thus contrasting with the high stiffness of the ventricle [

25]. Accordingly, the long hydrophobic domains in zebrafish ElnB were predicted to have implications for the decreased elastic modulus assuming a rubber model for the elasticity of elastin [

4,

23].

The mechanism underlying the reversible elasticity of elastin has been controversial for decades and was recently concluded to be primarily driven by the hydrophobic effect that was suggested to accounts for elastin’s low stiffness and high resilience [

26]. An evolutionary trend towards increased overall hydrophobicity in vertebrate arterial elastin was suggested to be an adaptive advantage in homeothermic vertebrates related to the higher blood pressure in the more advanced circulatory systems [

27,

28,

29], or by lowering the coacervation temperature to facilitate elastin formation in mammals, birds and alligators [

30]. The structural and functional properties of elastin should be investigated in a broad range of vertebrates to better understand the evolution of this unique protein and the relationship with different physiological adaptations and functional requirements among species. Many fish species are living in extreme environments, such as Antarctic icefish permanently inhabiting ice-cold water and are apparently lacking bulbar elastin [

21]. Deep-sea snailfish has developed unique adaptations to withstand the extreme hydrostatic pressure at depths below 8000 meters in the Mariana trench [

31,

32]. The Greenland shark has the longest lifespan in any known vertebrate of several hundred years that may be reflected in elastin stability and longevity. Here, w

e examine the diversity of elastins in a variety of primitive and advanced fish species spanning about 450 million years of evolution. Elastin gene duplications and subsequent divergence of the paralogs were investigated in tetraploid cyprinids and salmonids, including rainbow trout exhibiting three elastin genes with differential cardiac expression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Characterization of Fish Elastins

We searched for

eln genes in sequenced fish genomes available at NCBI’s Genome Resources (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/home/genomes) using the Blast tool (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The adjacent

limk1 and

septin4 genes were used to confirm the identify of uncharacterized or misnamed

eln genes. A phylogenetic tree of the elastins in tetraploid salmonid and cyprinid species was made by alignment of the amino acid sequence data using the ClustalW algorithm implemented in the software package MEGA (version 12) [

33]. MEGA was also used to perform a Neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic analysis with a Poisson model substitution matrix and uniform rates among sites. Bootstrapping with 500 pseudoreplicates was used to assess tree robustness.

Kyte-Doolitte hydrophobicity [

34] (

https://www.peptide2.com/N_peptide_hydrophobicity_hydrophilicity.php) was calculated for the full length Eln isoform coded by the complete transcript. Repeated hydrophobic motives and crosslinking domains were identified by manually searching the sequences. Graphpad Prism 10.4.1 was used to visualize hydrophobicity (%), and to compare elastin hydrophobicity (%) and mean ventral aortic blood pressure (kPa).

2.2. Fish Hold and Heart Sampling

Rainbow trout eggs and milt were supplied by AquaGen breeding company, and fertilized eggs were incubated at 10°C at the Aquaculture Research Station at Sunndalsøra, Norway, from 22. March 2023. The hatched larvae were transported before start feeding to Svanøy Havbruk at Svanøy island on the west coast of Norway. During the freshwater growth phase, the fish were raised at 10°C under constant light in fiberglass tanks from 16 to 280 m3. The oxygen levels were monitored continuously, and the fish were fed daily with commercial pellets. Pit-tagged fish were transferred to sea water at 15. Dec. 2023 and were kept in net pens until slaughtering at body weight of about 3500 gr at 12. Dec. 2024.

Twenty fish were sampled for histology and qPCR analysis of cardiac expression of eln genes during the freshwater phase at body weight of about 1 gr (22. May 2023), 10 gr (18. Aug. 2023), and 100 gr (01. Dec. 2023), and finally at about 700 gr in sea water (13. May 2024). The fish were anesthetized with MS-222 (tricaine methanesulfonate, 150 mg·L⁻¹) and killed with a blow to the head. The heart was removed and was stored in RNA-later until extraction of RNA from the dissected bulbus and ventricle. Larvae of 1 gr were fixated in 10 % PFA before histology and staining.

The study was conducted in accordance with the European Union Directive 2010/63/EU and the National Guidelines for Animal Care and Welfare established by the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. The Norwegian Food Safety Authority approved the experiment (FOTS ID 29083). Key personnel involved in the fish trial held FELASA C certification.

2.3. Histology

Formalin-fixed larvae (n = 10) were processed overnight in Tissue Processor (Logos; Milestone). Paraffin embedded tissues were sectioned (2 μm) using a rotary microtome (Leica) and stained with Elastin Van Gieson (EVG) staining kit (Atom Scientific Ltd, UK) according to manufacturer's instructions. The slides were then analyzed using light microscopy and the QuPath (Quantitative Pathology & Bioimage Analysis) software.

2.4. Molecular Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from heart tissue using Proteinase K digestion followed by Agencourt RNAadvanced Tissue Kit® (Beckman Coulter Inc., USA) using the Biomek 4000® robotic workstation according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a Nanodrop 8000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from mRNA using the Qiagen QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit® (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and then diluted 1:10 for qPCR analysis. No enzyme control and no template control were included as negative controls. The PCR mix consisted of 0.5 uL forward primer (10 uM), 0.5 uL reverse primer (10 uM), 5 uL PowerUp SYBR green (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and 4 uL diluted cDNA. The qPCR conditions were: 50 °C/2 min, 95 °C/20 sec; 40 cycles of 95°C/1 sec, 60 °C/20 sec. The melting curve conditions were 95°C/1 sec, 60 °C/20 sec, 95°C/1 sec. Specificity of all primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Eurofins genomics) of amplicons (

Table 1).

ef1a and b-act were evaluated as reference genes using RefFinder [

35], and the relative gene expression level was calculated according to the ΔΔCt method [

36] using

ef1a as reference gene. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05).

3. Results

We identified up to four different

eln genes in the sequenced genomes from 51 jawed fish species including cartilaginous fishes, basal ray-finned fishes, teleost fishes, and lobe-finned fish (

Table S1). All jawed fish genomes examined contain a syntenic block comprising

eln,

septin4/septin5 and

limk1, except for the more distant position of common carp

elnb2 to the other genes, while no tarpon

elnb is linked to

septin5 and

limk1 on chromosome 3. Examination of the jawless fish genomes revealed no

eln gene close to the hagfish

septin5 (LOC137430108), lamprey

septin4 (LOC116957768) and lamprey

limk1 (LOC116958416).

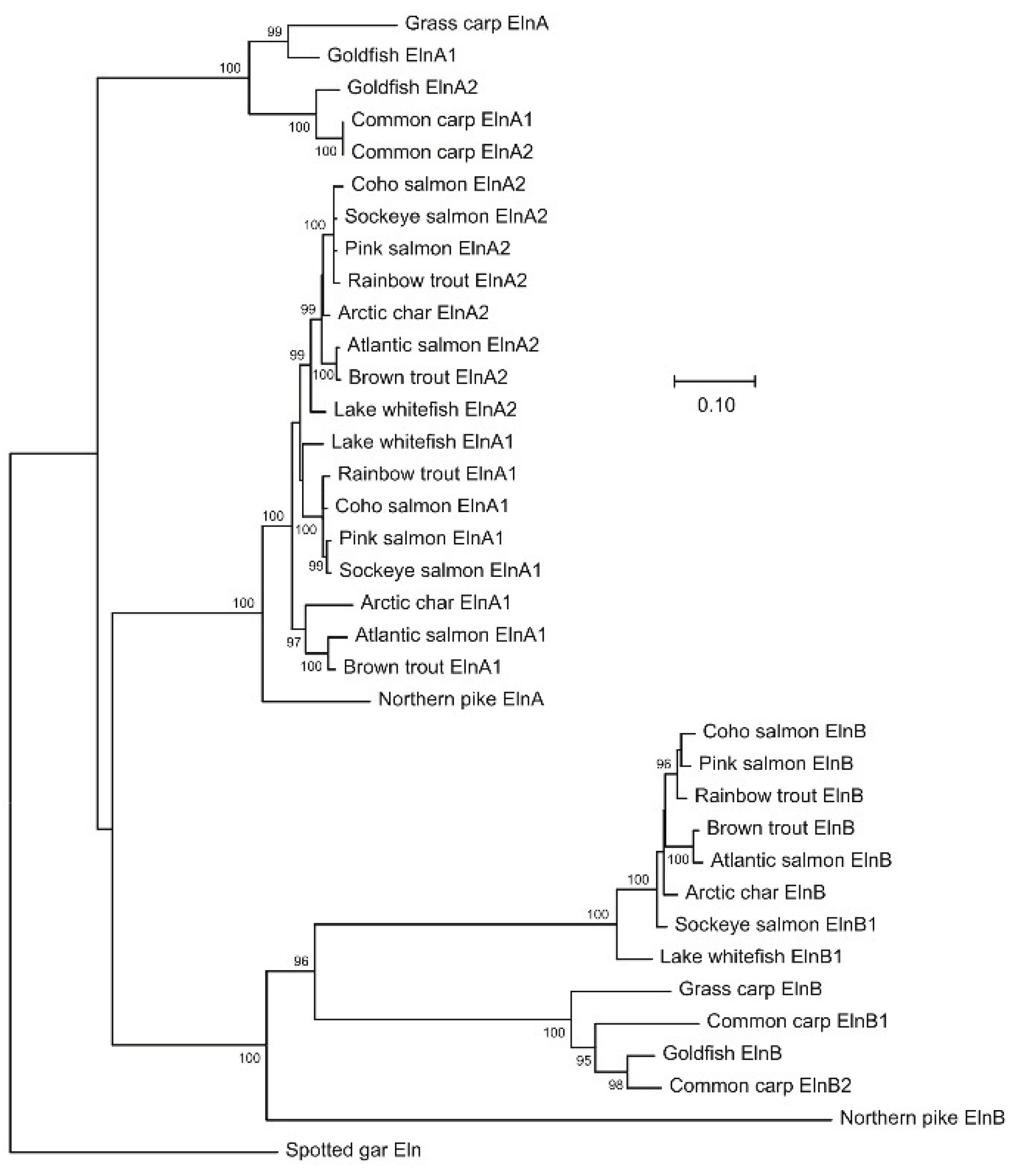

All non-teleost genomes contain a single

eln gene, whereas duplicated

elna and

elnb genes were found in teleosts, including Northern pike and grass carp, which are close relatives to tetraploid salmonids and cyprinids, respectively. The salmonids examined have duplicated

elna1 and

elna2 paralogs, but only a single

elnb gene, except for the tandem duplicated

elnb1 and

elnb2 genes in sockeye salmon and lake whitefish (

Figure 1). Common carp has four

eln genes named

elna1,

elna2,

elnb1 and

elnb2 located on separate chromosomes, while only

elna1,

elna2 and

elnb were identified in goldfish.

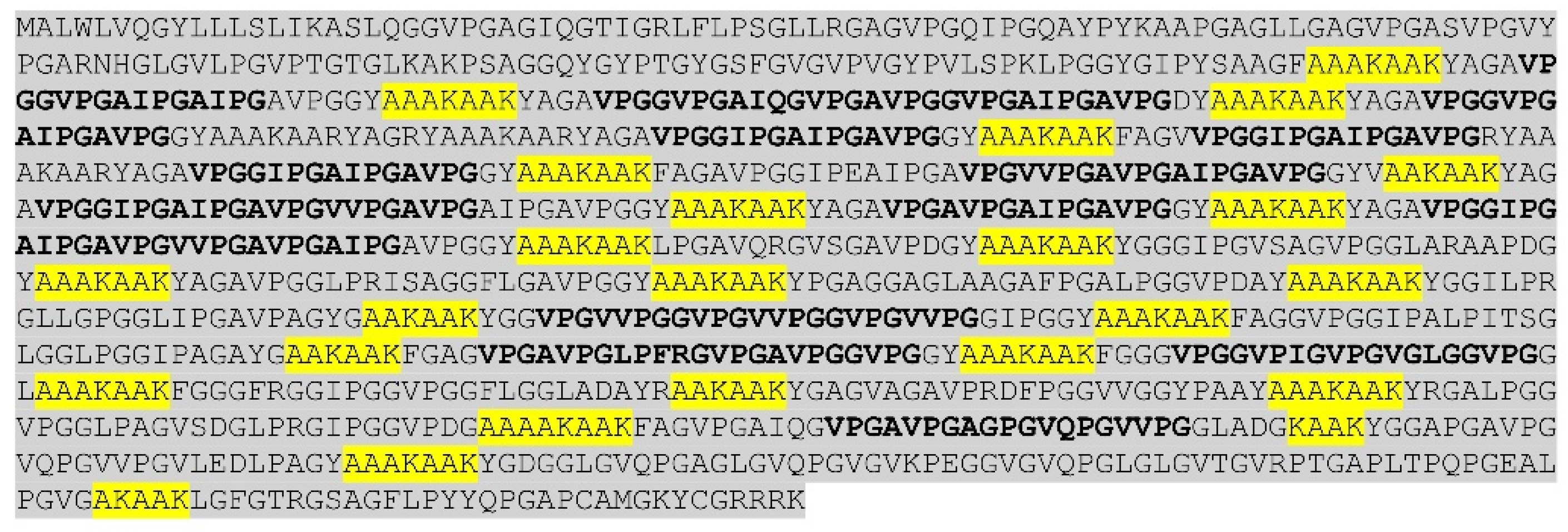

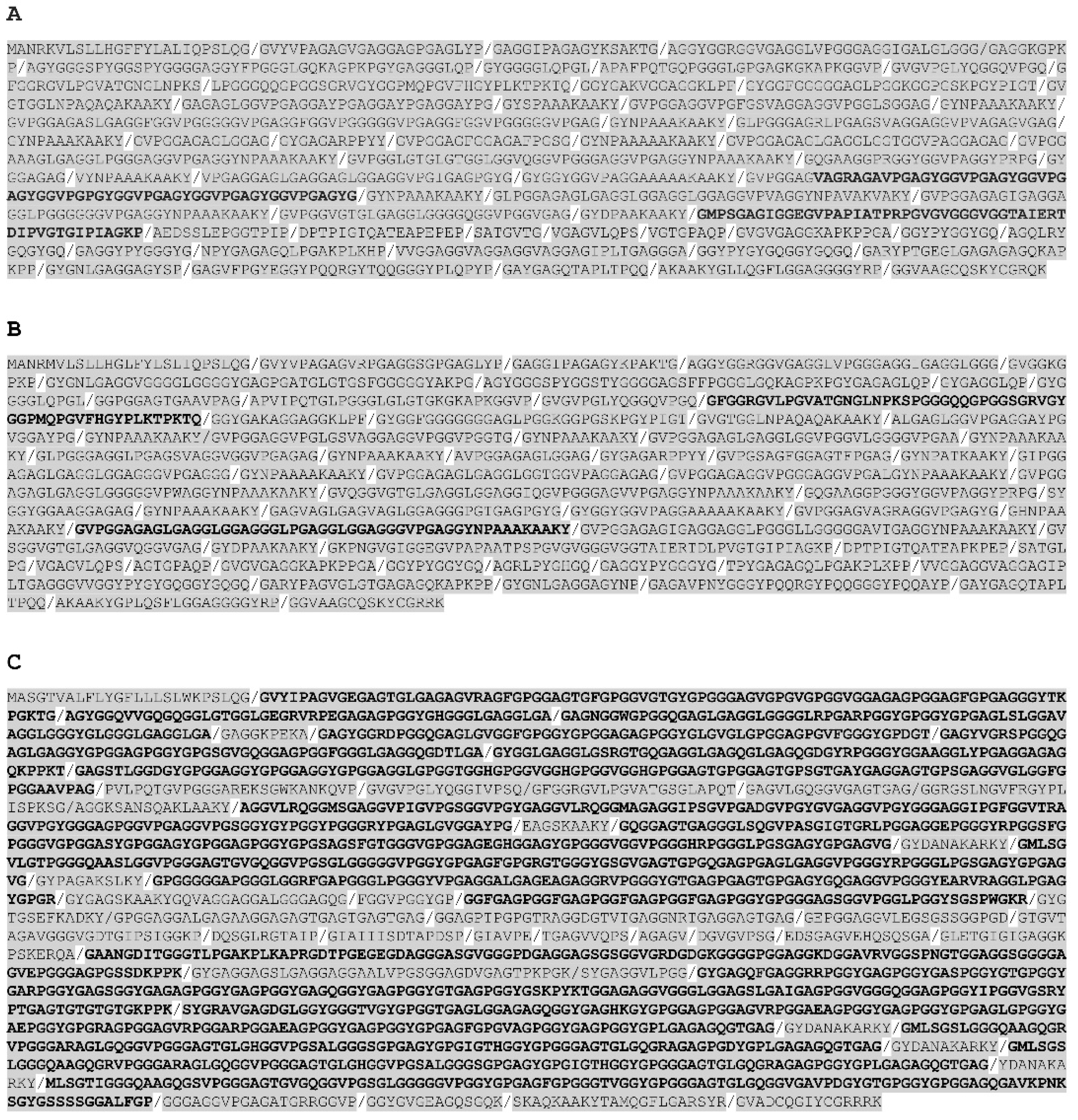

All fish

eln genes were found to contain multiple hydrophilic and hydrophobic exons, but the exon length varied considerably among the species and between the paralogs. Probably the most remarkable genetic structure is found in the lesser devil ray

eln gene, which consists of 70 exons containing multiple copies of 36-nt and 48-nt long exons coding for alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic domains, respectively (

Figure 2,

Figure S1). Similarly, the teleost

elna gene comprises multiple short exons, whereas the

elnb paralog consists of considerably larger hydrophobic exons. For example, yellow tuna ElnA of 1096 aa has 52 short exons, and the partial ElnB of 1433 aa is coded by 31 longer exons. The genetic structure also differs between the

elna and

elnb genes in the

tetraploid salmonids and cyprinids. The three

eln genes in rainbow trout have about the same number of exons, but the 2441-aa long ElnB consists of much longer hydrophobic domains compared to ElnA1 and ElnA2 of 1357 and 1403 aa, respectively (

Figure 3).

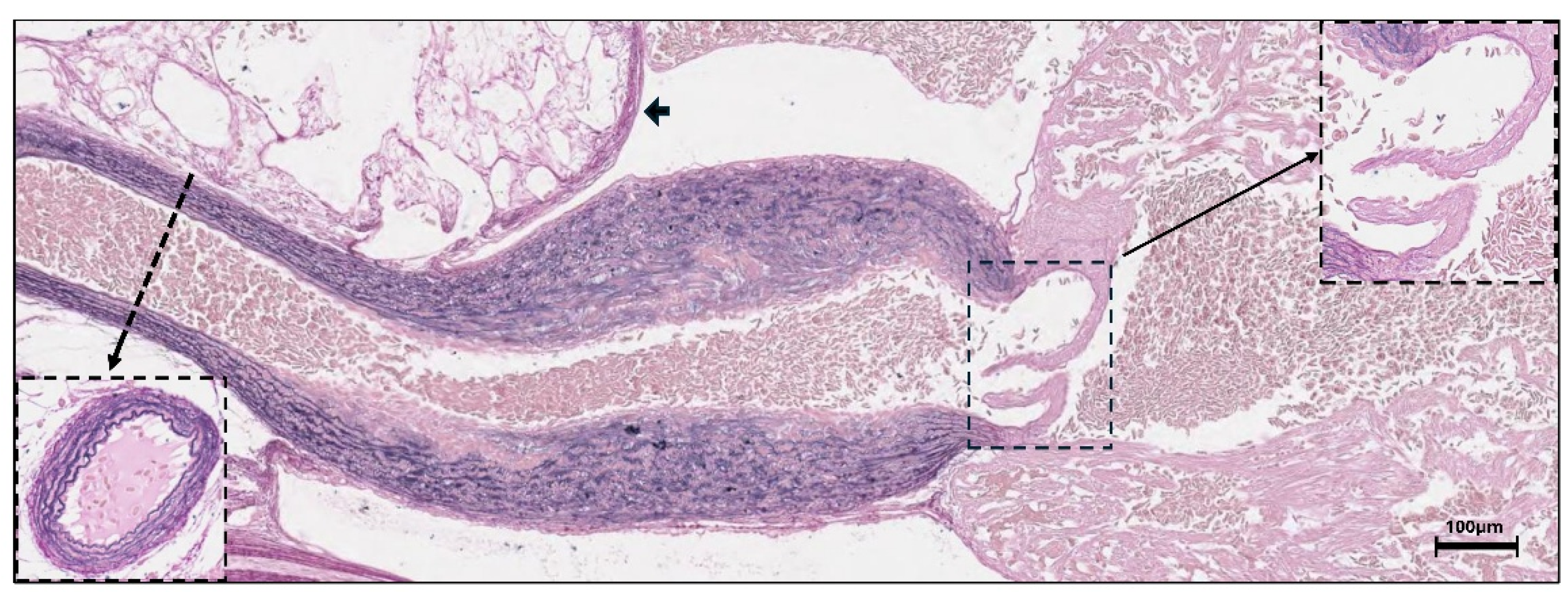

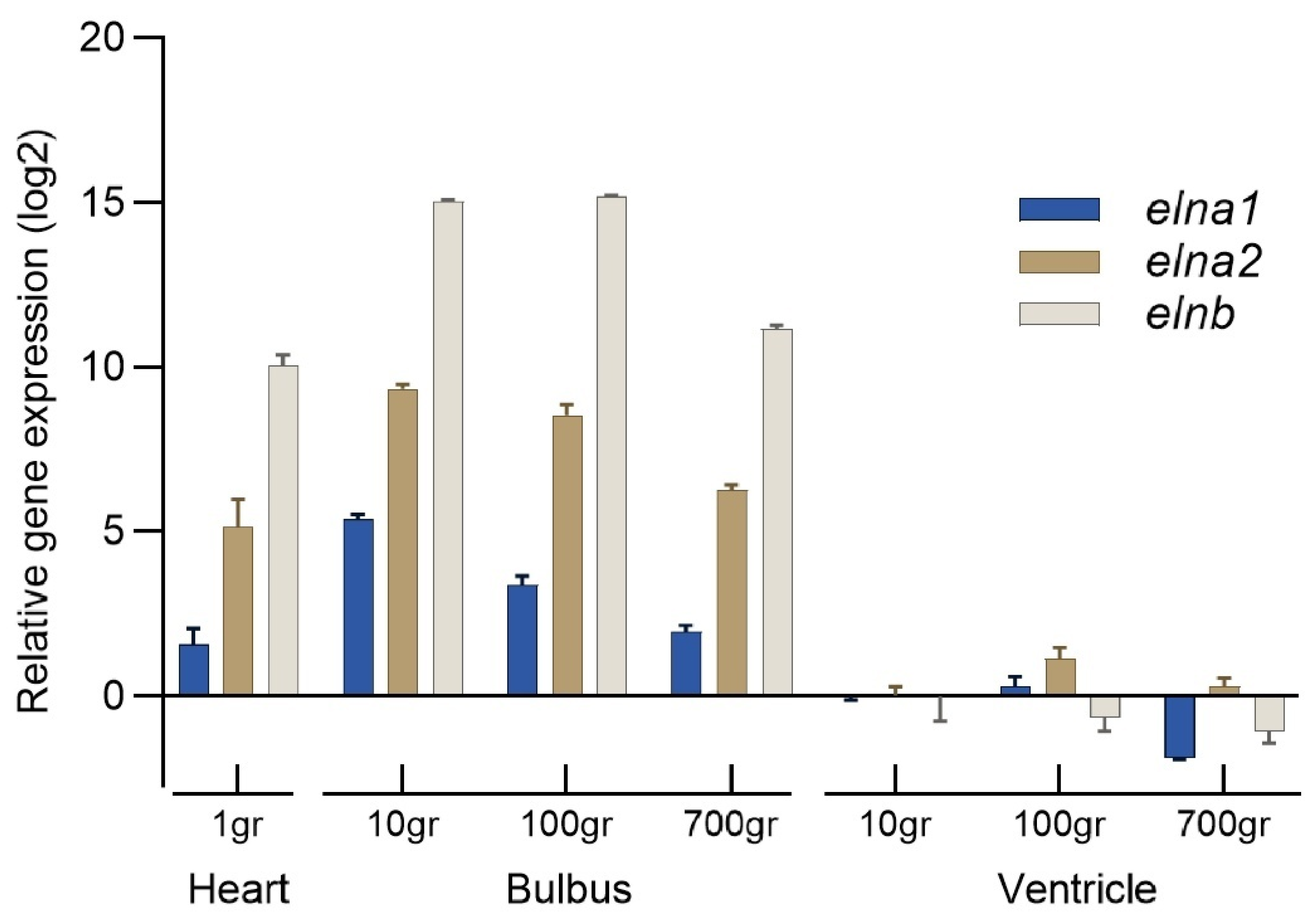

Histochemical analysis of 2-months old rainbow trout larvae revealed strong elastin staining in the bulbus and ventral aorta (

Figure 4). Elastin was weakly stained in the bulboventricular valve and in the pericardium, but was not found in the ventricle. qPCR quantification of the relative expression levels of the three

eln genes showed that

elnb dominated in the larval heart, and the

elnb mRNA levels were up to 15 times higher in the bulbus than in the ventricle of juvenile and adult fish (

Figure 5). The expression of

elna1 and

eln2 genes was lower than

elnb, but at significantly higher levels in bulbus than in ventricle.

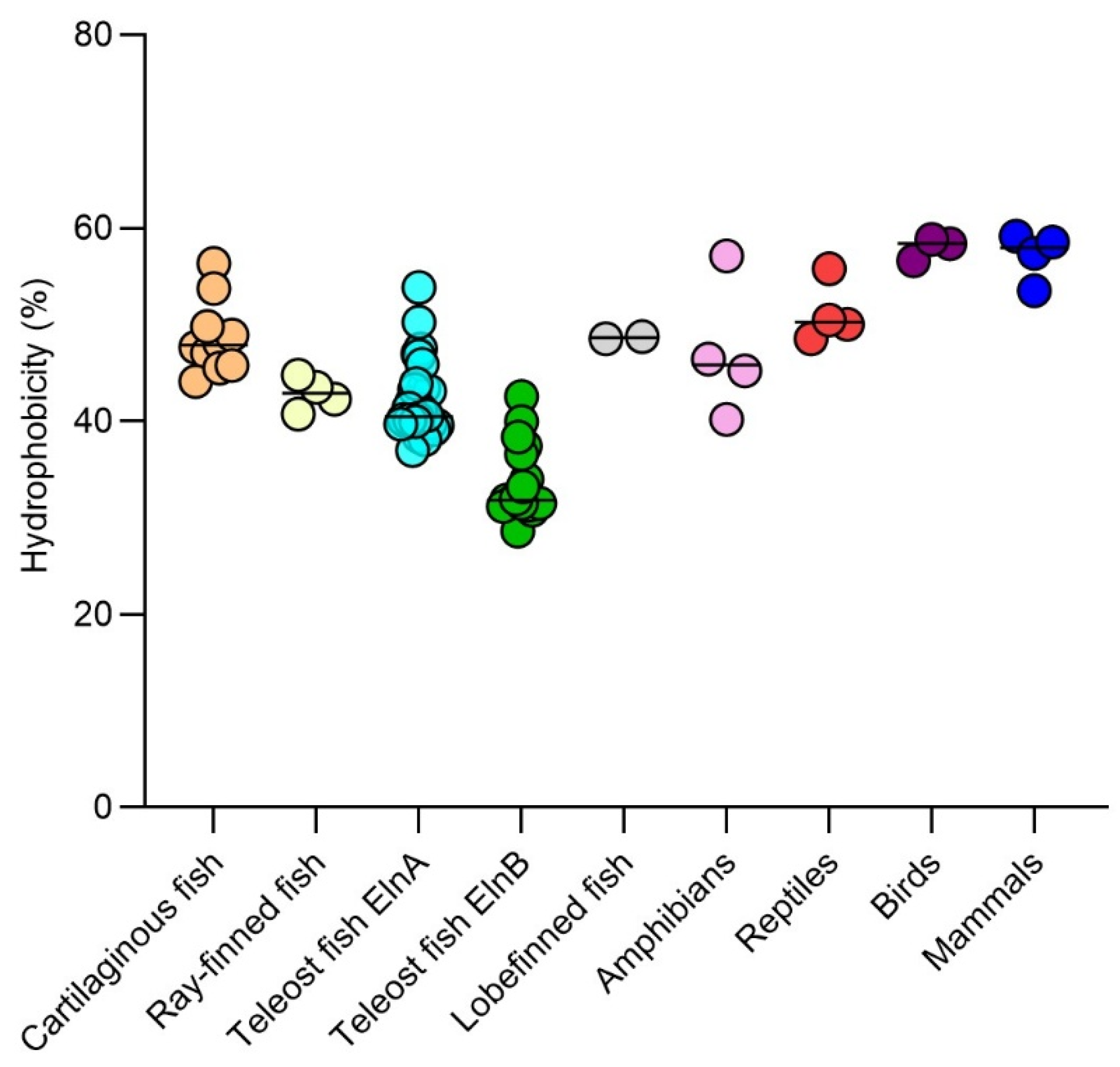

The overall hydrophobicity of fish elastin varies largely among species ranging from 28.6 % in the ElnB paralog of Emerald rockcod to 56.3% in the lesser devil ray Eln. Highly hydrophobic elastin was consistently found in cartilaginous and also in lobe-finned fish, while teleost ElnB paralogs are less hydrophobic (

Figure 6). The hydrophobicity of the elastin of the reptiles, birds and mammals examined suggested higher levels in tetrapods than in bony fish.

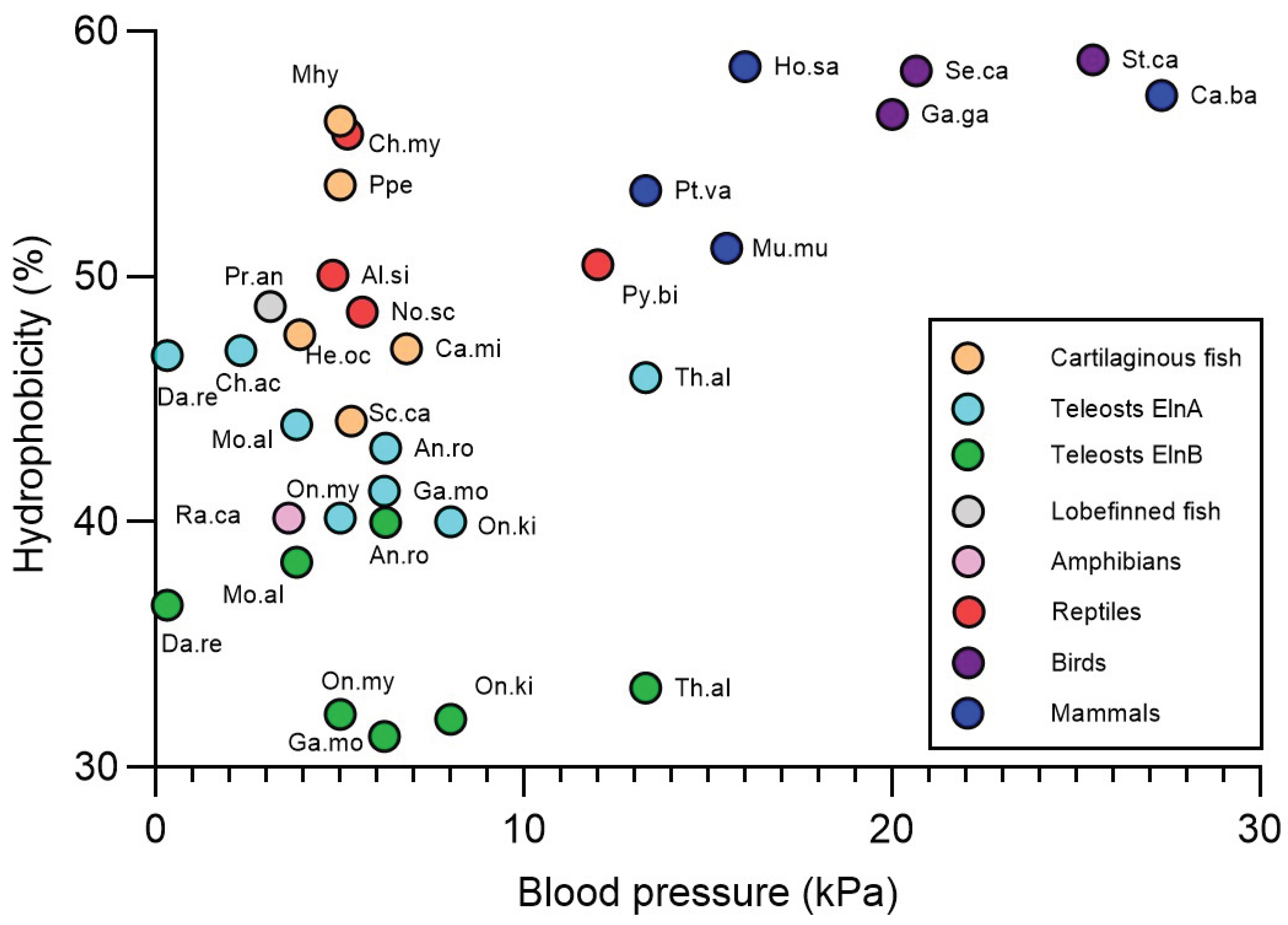

The relationship between the mean ventral aortic blood pressure and the overall elastin hydrophobicity was examined in various fish species. No correlation was found between the blood pressure levels and the hydrophobicity levels of non-teleost Eln and teleost ElnA (

Figure 7). Moreover, the overall hydrophobicity of the teleost ElnB paralog showed no relationship with the blood pressure in the bulbus, where pressure levels were derived from the strong correlation between bulbar plateau pressure and ventral aortic pressure [

37]. In comparison, the tetrapod species examined possessed high elastin hydrophobicity and high blood pressure levels (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

The systematic survey of elastin genes in the sequenced genomes from diverse fish species identified up to four different elastins in the jawed species sharing the characteristic properties of multiple alternating hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains with a Cys pair in the negatively charged C-terminal end. Whereas the linear sequence of the single elastin in sharks and rays has been well conserved during almost 450 million years of evolution, teleost ElnA and ElnB have diverged considerably in agreement with the subfunctionalization of the paralogs in zebrafish [

23,

24,

25]. Consistent with the differential expression of

elna and

elnb in the developing zebrafish heart, the expression of rainbow trout

elnb dominated in the larval heart and in the bulbus of juvenile and adult fish. The different expression patterns of teleost

elna and

elnb may have diverged in parallel with the divergence in the genetic structure comprising multiple short exons in

elna similar to non-teleost

eln, while teleost

elnb contains considerably longer hydrophobic domains exons. Accordingly, the low stiffness imparted by ElnB for proper bulbus cell fate and function was predicted to be the result of the long hydrophobic domains in ElnB [

4,

23,

25]. The high distensibility and resilience of the bulbus have consistently been reported in various teleost species, and was calculated to account for 25% of the blood flow in rainbow trout at rest [

38]. Intriguingly, thermal remodeling of the rainbow trout heart during cold acclimation resulted in decreased elastin-to-collagen ratio and increased stiffness in the bulbus [

39].

The Antarctic icefish ElnB paralog has very low overall hydrophobicity, such as the red-blooded Emerald rockcod, which together with the white-blooded crocodile icefish are lacking bulbar elastin [

40,

41]. The low hydrophobicity and few cross-links support the suggested inability of the bulbar elastin in Antarctic icefish to aggregate into larger units at freezing temperatures [

40]. In human elastin, disruptions of the hydrophobic domains were shown to be detrimental to the self-assembly process, and mutated human elastin required much higher temperatures than the normal physiological temperature to achieve full coacervation [

42]. On the other hand, the absence of elastin fibers in Antarctic fish could be simply the result of extreme morpho-functional adaptation to constant sub-zero temperatures [

21]. The Antarctic icefishes have very large hearts, high blood volumes and low blood pressure, and smooth muscle cells may contribute to the elastic properties of the bulbus maintaining constant aortic flow in the large branchial vessels [

41,

43,

44,

45].

Except for Antarctic icefishes, the various fish species examined revealed no relation between elastin hydrophobicity and blood pressure. Cartilaginous fish exhibit the most hydrophobic elastin among jawed fish, but slow-mowing sharks have low ventral aortic blood pressure below 4 kPa, while blood pressure around 7 kPa has been recorded in fast-mowing sharks that is probably similar in rays [

46,

47,

48,

49]. In comparison, lobe-finned fish exhibited relative high elastin hydrophobicity, while low blood pressure of 3.1 kPa was measured in West-African lungfish [

50]. Similarly, the primitive sterlet sturgeon showed the highest elastin hydrophobicity of 44.8% among non-teleostean ray-finned fish, but blood pressure less than 3 kPa was reported in white sturgeon [

51]. Except for tarpon and baby whalefish, all teleost elastins examined have hydrophobicity below 50 %, but show large differences in ventral aortic blood pressure varying from 0.3 to 13 kPa in zebrafish and tuna fish, respectively [

52,

53]. While the overall hydrophobicity of ElnA is higher than ElnB in the two species, the importance of the long hydrophobic domains in zebrafish ElnB for the elasticity [

4,

23] should be further investigated in other teleost species. On the other hand, the athletic tuna fish has thick aortic elastin lamella and bulbar elastin fibres, in contrast to the low amounts of elastin in zebrafish [

22,

23,

53]. Consistently, the higher elastin content in some species than in others probably gives higher tissue compliance and elasticity [

19,

21,

38,

54,

55].

Deep sea snailfish possess diverse adaptations to withstand the extreme pressures of the deep ocean. Their blood pressure is in equilibrium with the immense external pressure partly due to the incompressible nature of their body fluids and tissues preventing them from being crushed. Deep-diving mammals have significantly stiffer arteries than other mammals that is presumably an adaptation to high hydrostatic pressure [

56]. Elastin in whales and dolphins were found to contain unusual high amount of acidic amino acids (0.7-0.8%) that may reduce the elastic modulus of the elastin polymer by forming stable salt bridges [

57]. In comparison, snailfish ElnB has more than 1% Glu and Asp residues that may contribute to surviving the high pressure by making the blood vessels stiffer. However, it should be noted that the number of acidic amino acids varies greatly in fish elastins ranging from a single residue in elephant shark to 52 residues (4.5%) in the little skate, while both species are living in shallow waters down to 100-200 m.

5. Conclusions

The single elastin in non-teleosts has been well conserved during 450 million years of evolution, but structural differences among species may be related to dissimilar adaptations and functional requirements. In teleosts, the differential expression and subfunctions of the duplicated ElnA and ElnB during cardiac development probably evolved together with the divergence in the genetic structure leading to the enlarged hydrophobic domains in the ElnB paralog.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, Ø.A. and T.K.Ø; molecular analysis, T.K.Ø.; writing manuscript, Ø.A.; review and editing, Ø.A. and T.K.Ø.

Funding

The study received funding from the Norwegian Research Council managing “Skattefunn” (Tax Deduction for Research and Development Projects).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the European Union Directive 2010/63/EU and the National Guidelines for Animal Care and Welfare established by the Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. The Norwegian Food Safety Authority approved the experiment (FOTS ID 29083). Key personnel involved in the fish trial held FELASA C certification.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and in

Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Table S1 gives the accession numbers of the fish elastin examined.

Figure S1 gives the alignment of the multiple copies encoding alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic domains in the lesser devil ray elastin.

Figure S2 shows the elastin proteins with crosslinks in ray-finned and lobe-finned fishes.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Miroslava Hansen for the excellent histochemical work and Torstein Tengs for performing the phylogenetic analysis. Marianne H. S. Hansen and Mari A. Braaten are greatly acknowledged for the qPCR quantification of elastin gene expression in rainbow trout heart.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- Sato, F.; Wachi, H.; Ishida, M.; Nonaka, R.; Onoue, S.; Urban, Z.; Starcher, B.C.; Seyama, Y. Distinct steps of cross-linking, self-association, and maturation of tropoelastin are necessary for elastic fiber formation. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 369, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmelzer, C.E.; Hedtke, T.; Heinz, A. Unique molecular networks: formation and role of elastin cross-links. Iubmb Life 2020, 72, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.; Endicott, S.; Province, M.; Pierce, J.; Campbell, E. Marked longevity of human lung parenchymal elastic fibers deduced from prevalence of D-aspartate and nuclear weapons-related radiocarbon. The Journal of clinical investigation 1991, 87, 1828–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.I.; Miao, M.; Stahl, R.J.; Chan, E.; Parkinson, J.; Keeley, F.W. Sequences and domain structures of mammalian, avian, amphibian and teleost tropoelastins: Clues to the evolutionary history of elastins. Matrix biology 2006, 25, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, D.W.; Starcher, B.; Partridge, S. Coacervation of solubilized elastin effects a notable conformational change. Nature 1969, 222, 795–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.A.; Starcher, B.C.; Urry, D.W. Coacervation of tropoelastin results in fiber formation. J. Biol. Chem. 1974, 249, 997–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauscher, S.; Baud, S.; Miao, M.; Keeley, F.W.; Pomes, R. Proline and glycine control protein self-organization into elastomeric or amyloid fibrils. Structure 2006, 14, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozel, B.A.; Mecham, R.P. Elastic fiber ultrastructure and assembly. Matrix Biology 2019, 84, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedell-Hogan, D.; Trackman, P.; Abrams, W.; Rosenbloom, J.; Kagan, H. Oxidation, cross-linking, and insolubilization of recombinant tropoelastin by purified lysyl oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 10345–10350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schräder, C.U.; Heinz, A.; Majovsky, P.; Mayack, B.K.; Brinckmann, J.; Sippl, W.; Schmelzer, C.E. Elastin is heterogeneously cross-linked. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 15107–15119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Sitarz, E.; Bellingham, C.M.; Won, E.; Muiznieks, L.D.; Keeley, F.W. Sequence and domain arrangements influence mechanical properties of elastin-like polymeric elastomers. Biopolymers: Original Research on Biomolecules 2013, 99, 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonaka, R.; Sato, F.; Wachi, H. Domain 36 of tropoelastin in elastic fiber formation. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2014, 37, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bax, D.V.; Rodgers, U.R.; Bilek, M.M.; Weiss, A.S. Cell adhesion to tropoelastin is mediated via the C-terminal GRKRK motif and integrin αVβ3. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 28616–28623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozel, B.A.; Wachi, H.; Davis, E.C.; Mecham, R.P. Domains in tropoelastin that mediate elastin depositionin vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 18491–18498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, W.; Guo, D.; Veldtman, G.; Tan, W. Effect of viscoelasticity on arterial-like pulsatile flow dynamics and energy. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering 2020, 142, 041001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faury, G. Function–structure relationship of elastic arteries in evolution: from microfibrils to elastin and elastic fibres. Pathol. Biol. 2001, 49, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, G.G. Elastic properties and Windkessel function of the human aorta. Cardiovascular drugs and therapy 1995, 9, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, D. Functional morphology of the heart in fishes. Am. Zool. 1968, 8, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licht, J.H.; Harris, W.S. The structure, composition and elastic properties of the teleost bulbus arteriosus in the carp, Cyprinus carpio. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology 1973, 46, 699–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A. The Wind-Kessel effect of the bulbus arteriosus in trout. Journal of Experimental Zoology 1979, 209, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icardo, J.; Colvee, E.; Cerra, M.C.; Tota, B. The bulbus arteriosus of stenothermal and temperate teleosts: a morphological approach. J. Fish Biol. 2000, 57, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.H.; Brill, R.W.; Gosline, J.M.; Jones, D.R. Form and function of the bulbus arteriosus in yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares): dynamic properties. J. Exp. Biol. 2003, 206, 3327–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, M.; Bruce, A.; Bhanji, T.; Davis, E.; Keeley, F. Differential expression of two tropoelastin genes in zebrafish. Matrix Biology 2007, 26, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriyama, Y.; Ito, F.; Takeda, H.; Yano, T.; Okabe, M.; Kuraku, S.; Keeley, F.W.; Koshiba-Takeuchi, K. Evolution of the fish heart by sub/neofunctionalization of an elastin gene. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuki, S.; Inoue, Y.; Watanabe, R.; Mitsui, T.; Moriyama, Y. Extracellular stiffness regulates cell fate determination and drives the emergence of evolutionary novelty in teleost heart. bioRxiv, 2005; 2025.2005. 2013.653630. [Google Scholar]

- Jamhawi, N.M.; Koder, R.L.; Wittebort, R.J. Elastin recoil is driven by the hydrophobic effect. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2304009121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sage, H. Structure-function relationships in the evolution of elastin. J Invest Dermatol 1982, 79, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, H.; Gray, W. Studies on the evolution of elastin—III. The ancestral protein. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Comparative Biochemistry 1981, 68, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, H.; Gray, W. Studies on the evolution of elastin--I. Phylogenetic distribution. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. B, Comparative biochemistry 1979, 64, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, G.; Gosline, J.; Lillie, M. The hydrophobicity of vertebrate elastins. J. Exp. Biol. 1999, 202, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Shen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Gan, X.; Liu, G.; Hu, K.; Li, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhu, L.; Yan, G. Morphology and genome of a snailfish from the Mariana Trench provide insights into deep-sea adaptation. Nature ecology & evolution 2019, 3, 823–833. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Zhu, C.; Gao, X.; Wu, B.; Xu, H.; Hu, M.; Zeng, H.; Gan, X.; Feng, C.; Zheng, J. Chromosome-level genome assembly of hadal snailfish reveals mechanisms of deep-sea adaptation in vertebrates. Elife 2023, 12, RP87198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Suleski, M.; Sanderford, M.; Sharma, S.; Tamura, K. MEGA12: Molecular Evolutionary Genetic Analysis version 12 for adaptive and green computing. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41, msae263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyte, J.; Doolittle, R.F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J. Mol. Biol. 1982, 157, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Xiao, P.; Chen, D.; Xu, L.; Zhang, B. miRDeepFinder: a miRNA analysis tool for deep sequencing of plant small RNAs. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012, 80, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W. Quantification strategies in real-time PCR. In A–Z of Quantitative PCR, Bustin, S.A., Ed.; International University Line: La Jolla, CA, 2004; pp. 87–120. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.R.; Perbhoo, K.; Braun, M.H. Necrophysiological determination of blood pressure in fishes. Naturwissenschaften 2005, 92, 582–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priede, I.G. Functional morphology of the bulbus arteriosus of rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri Richardson). J. Fish Biol. 1976, 9, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, A.N.; Mackrill, J.J.; Gardner, P.; Shiels, H.A. Compliance of the fish outflow tract is altered by thermal acclimation through connective tissue remodelling. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2021, 18, 20210492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icardo, J.M.; Colvee, E.; Cerra, M.C.; Tota, B. Bulbus arteriosus of the antarctic teleosts. I. The white-blooded Chionodraco hamatus. The Anatomical Record: An Official Publication of the American Association of Anatomists 1999, 254, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icardo, J.M.; Colvee, E.; Cerra, M.C.; Tota, B. Bulbus arteriosus of the Antarctic teleosts. II. The red-blooded Trematomus bernacchii. The Anatomical Record 1999, 256, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toonkool, P.; Jensen, S.A.; Maxwell, A.L.; Weiss, A.S. Hydrophobic domains of human tropoelastin interact in a context-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 44575–44580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloop, G. The cardiovascular system of Antarctic Icefish appears to have been designed to utilize hemoglobinless blood. BIO-Complexity 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidell, B.D.; O'Brien, K.M. When bad things happen to good fish: the loss of hemoglobin and myoglobin expression in Antarctic icefishes. J. Exp. Biol. 2006, 209, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zummo, G.; Acierno, R.; Agnisola, C.; Tota, B. The heart of the icefish: bioconstruction and adaptation. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research= Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas 1995, 28, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, E.; Short, S.t.; Butler, P. The role of the cardiac vagus in the response of the dogfish Scyliorhinus canicula to hypoxia. J. Exp. Biol. 1977, 70, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, N.C.; Korsmeyer, K.E.; Katz, S.; Holts, D.B.; Laughlin, L.M.; Graham, J.B. Hemodynamics and blood properties of the shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus). Copeia 1997, 1997, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speers-Roesch, B.; Brauner, C.J.; Farrell, A.P.; Hickey, A.J.; Renshaw, G.M.; Wang, Y.S.; Richards, J.G. Hypoxia tolerance in elasmobranchs. II. Cardiovascular function and tissue metabolic responses during progressive and relative hypoxia exposures. J. Exp. Biol. 2012, 215, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadwick, R.E.; Bernal, D.; Bushnell, P.G.; Steffensen, J.F. Blood pressure in the Greenland shark as estimated from ventral aortic elasticity. J. Exp. Biol. 2018, 221, jeb186957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szidon, J.P.; Lahiri, S.; Lev, M.; Fishman, A.P. Heart and circulation of the African lungfish. Circul. Res. 1969, 25, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Braga, V.H.; Armelin, V.A.; Noll, I.G.; Florindo, L.H.; Milsom, W.K. Cardiorespiratory reflexes in white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus): Lack of cardiac baroreflex response to blood pressure manipulation? Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2024, 288, 111554. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, N.; Yost, H.J.; Clark, E.B. Cardiac morphology and blood pressure in the adult zebrafish. The Anatomical Record: An Official Publication of the American Association of Anatomists 2001, 264, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, M.H.; Brill, R.W.; Gosline, J.M.; Jones, D.R. Form and function of the bulbus arteriosus in yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares), bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus) and blue marlin (Makaira nigricans): static properties. J. Exp. Biol. 2003, 206, 3311–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A.; Cobb, J. A comparative study on the innervation and the vascularization of the bulbus arteriosus in teleost fish. Cell Tissue Res. 1979, 196, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, M.; Norman, D.; Santer, R.; Scarborough, D. Histological, histochemical and ultrastructural studies on the bulbus arteriosus of the sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus and Pungitius pungitius (Pisces: Teleostei). J. Zool. 1983, 200, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillie, M.; Piscitelli, M.; Vogl, A.; Gosline, J.; Shadwick, R. Cardiovascular design in fin whales: high-stiffness arteries protect against adverse pressure gradients at depth. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 216, 2548–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, F.W. Evolutionary constraints on positional sequence, collective properties and sequence style of tropoelastin dictated by fundamental requirements for formation and function of the extracellular elastic matrix. bioRxiv, 2003; 2012. 2003.626628. [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson, M.; Farrell, A.P. Coronary blood flow in vivo in the coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch). American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 1993, 264, R963–R971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.G.; Oudit, G.Y.; Cadinouche, M.Z. Angiotensin I-and II-and norepinephrine-mediated pressor responses in an ancient holostean fish, the bowfin (Amia calva). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1995, 98, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.J.; Rodnick, K.J. Pressure and volume overloads are associated with ventricular hypertrophy in male rainbow trout. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 1999, 277, R938–R946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.; Elfwing, M.; Elsey, R.M.; Wang, T.; Crossley II, D.A. Coronary blood flow in the anesthetized American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2016, 191, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.; Nielsen, J.M.; Axelsson, M.; Pedersen, M.; Löfman, C.; Wang, T. How the python heart separates pulmonary and systemic blood pressures and blood flows. J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranjape, V.V.; Gatson, B.J.; Bailey, K.; Wellehan, J.F. Cuff size, cuff placement, blood pressure state, and monitoring technique can influence indirect arterial blood pressure monitoring in anesthetized bats (Pteropus vampyrus). Am. J. Vet. Res. 2023, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, N.K.; Bayley, M.; Wang, T. Autonomic control of the heart in the Asian swamp eel (Monopterus albus). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 2011, 158, 485–489. [Google Scholar]

- Seymour, R.S.; Blaylock, A.J. The principle of Laplace and scaling of ventricular wall stress and blood pressure in mammals and birds. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2000, 73, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).