1. Introduction

In modern engineering applications, composite materials, which are increasingly preferred, are synthetic, multi-phase systems produced by combining two or more different phases within a defined structure. In this context, both synthetic and natural fiber-reinforced composites are utilized [

1,

2]. Composites can simultaneously fulfill multiple functions in modern applications by combining the lightness and flexibility of the matrix with the superior properties of the reinforcing fillers [

3].

To meet specific requirements, the adjustment of electrical properties involves the selection of compression pressure, particle size, and composition. In these materials, there exists a clearly defined interface between phases, which provides enhanced performance characteristics that cannot be achieved by individual components alone. Due to their advantages such as lightness, high strength, flexibility, and environmental resistance, composites have gained strategic importance [

4,

5].

The effective and safe use of these materials is not limited to understanding the properties of their components but also requires an understanding of how these properties contribute to the overall material integrity. The behavior of composites becomes complex when subjected to variable external conditions such as impact, temperature fluctuations, vibration, and cyclic loading. Therefore, fiber-reinforced composites are widely preferred in aerospace and other engineering fields due to their excellent specific strength, stiffness, and corrosion resistance. At this point, the interfacial region that ensures load transfer within the material is of vital importance. The structural integrity of the interface enables efficient load transfer, while weaknesses in this region can negatively affect the overall durability of the structure [

6,

7].

Composites formed by combining phases with different physical and chemical properties in an orderly manner offer both structural and functional advantages in various engineering fields. These materials, which stand out for their high strength to weight ratio, formability, and resistance to environmental conditions, are widely used in aircraft and automotive industries, construction, energy systems, and defense technologies. In tribological applications, environmental conditions should also be considered when selecting GFRP and CFRP [

8,

9,

10].

In practical applications, fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites are commonly used in marine environments and wind turbine blades due to their lightweight structure and high structural strength. However, since most turbine blades consist of adhesively bonded composite parts, these regions may suffer damage over time due to environmental effects and fatigue. Therefore, understanding the deterioration of bonding surfaces and interfacial regions is critical for ensuring the long-term durability of the blades [

11,

12,

13]. The sustainability of structural integrity depends not only on the mechanical properties of the reinforcing fibers and matrix but also on the quality of their interaction, the homogeneity of the interface, and the accuracy of manufacturing techniques. Under dynamic loading, temperature variations, and wind effects, the behavior of the interface plays a decisive role. Particularly, fiber orientation directly affects load distribution, shaping the overall performance of the structure [

14].

Similarly, FRP structures used in marine environments are exposed to harsh conditions such as wave forces, the chemical effects of seawater, and thermal cycles; therefore, the strength of adhesive and interfacial regions constitutes a critical design issue in marine engineering as well [

15,

16]. Hence, comparing carbon fiber-reinforced composites with glass fiber-reinforced composites will enable a better understanding of their superior properties [

17].

Today, fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites are among the fundamental materials preferred in both wind turbine blades and marine structural components. In wind turbines, the lightweight and high-strength nature of large-span blades not only enhances energy efficiency but also challenges structural durability. Since these structures are mostly composed of multiple composite parts joined by adhesive bonding, interfacial and bonding regions are at risk of degradation over time under environmental effects and cyclic loading. Similarly, FRP structures used in marine environments face critical design challenges related to interface strength due to exposure to wave forces, saltwater, ultraviolet radiation, temperature changes, and repeated mechanical loads [

18,

19,

20].

In both application areas, the microstructural interactions in the interfacial region, load transfer mechanisms, and manufacturing quality are critical to maintaining structural integrity. Therefore, to ensure the long-term and reliable performance of composite structures in wind turbines and marine environments, comprehensive analyses and improvement strategies should be developed regarding the durability of adhesives and interfacial materials [

12]. A deep understanding of the damage formation mechanisms in interface regions under environmental stresses and cyclic mechanical loads is of vital importance for the sustainability and safety of these technologies.

In wind energy technologies, blade design represents a critical engineering challenge in terms of both structural strength and energy efficiency. The materials used in offshore wind turbine blades are selected to withstand harsh environmental conditions such as high humidity, salinity, temperature fluctuations, and repeated mechanical loads. In this context, glass fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) and carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites are widely preferred due to their specific strength, corrosion resistance, and ease of manufacturing [

21,

22].

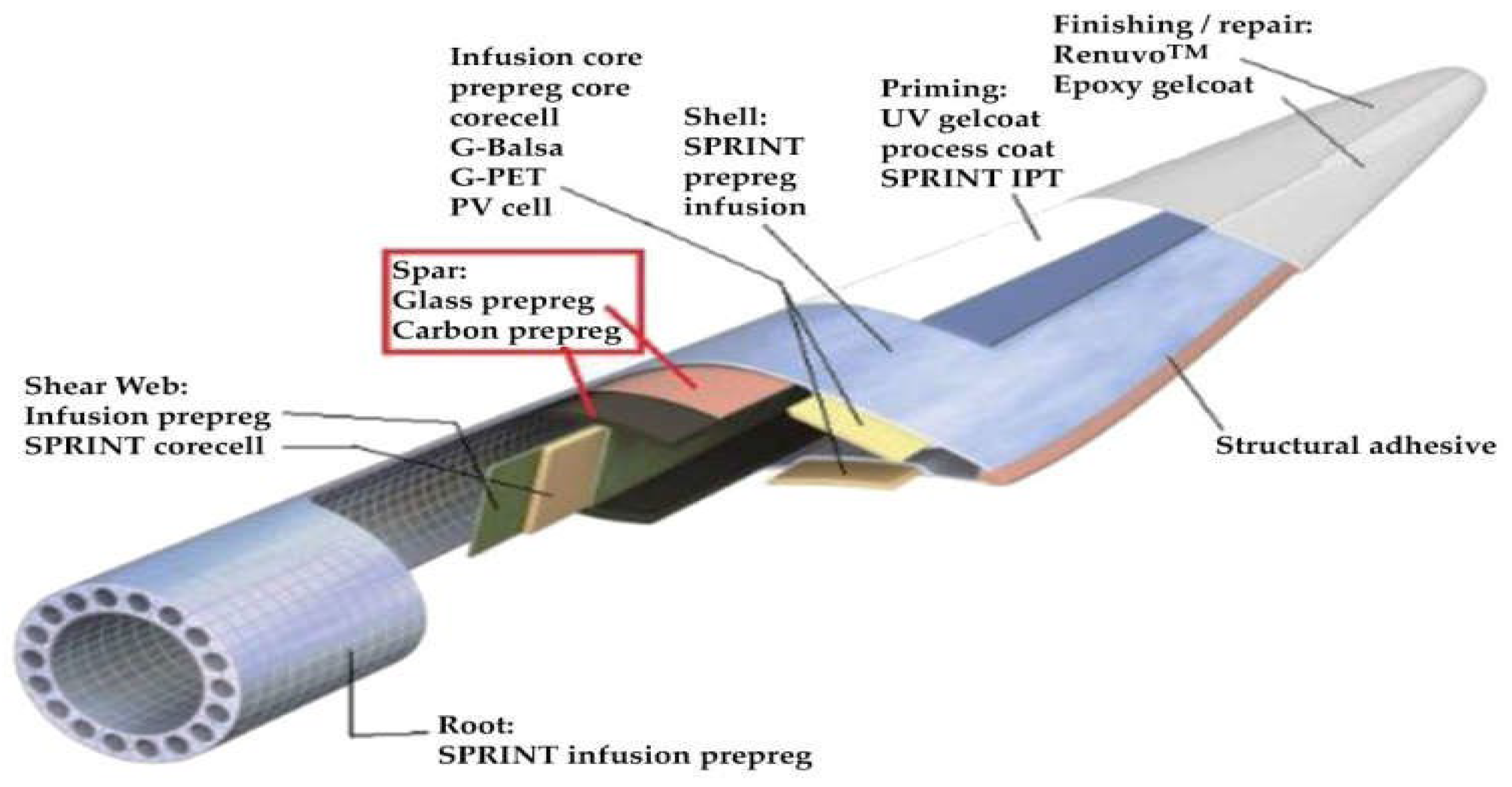

GFRP materials are generally used in the outer shell (skin) and surface layers of the blades due to their low density, high impact resistance, and cost-effective production advantages. In these regions, GFRP distributes the stresses generated by aerodynamic loads uniformly, maintaining the overall structural stability of the blade. In contrast, since the root and spar (main beam) sections of the blade require higher stiffness and bending strength, CFRP reinforcements are commonly employed. CFRP materials, with their high elastic modulus and fatigue resistance, contribute to reducing the overall weight of long blades and improving their vibration performance [

23,

24].

Figure 1 illustrates the types of materials preferred in different structural regions of a wind turbine blade.

Hybrid lamination strategies are increasingly being used in modern wing designs. In this approach, GFRP and CFRP layers are used together to achieve a balance between cost-effectiveness and mechanical performance. CFRP is used in high-load-bearing layers, particularly in spar skins or spar-cover transition areas, while GFRP is preferred for external surfaces. This helps control material costs and extends the fatigue life of the structure [

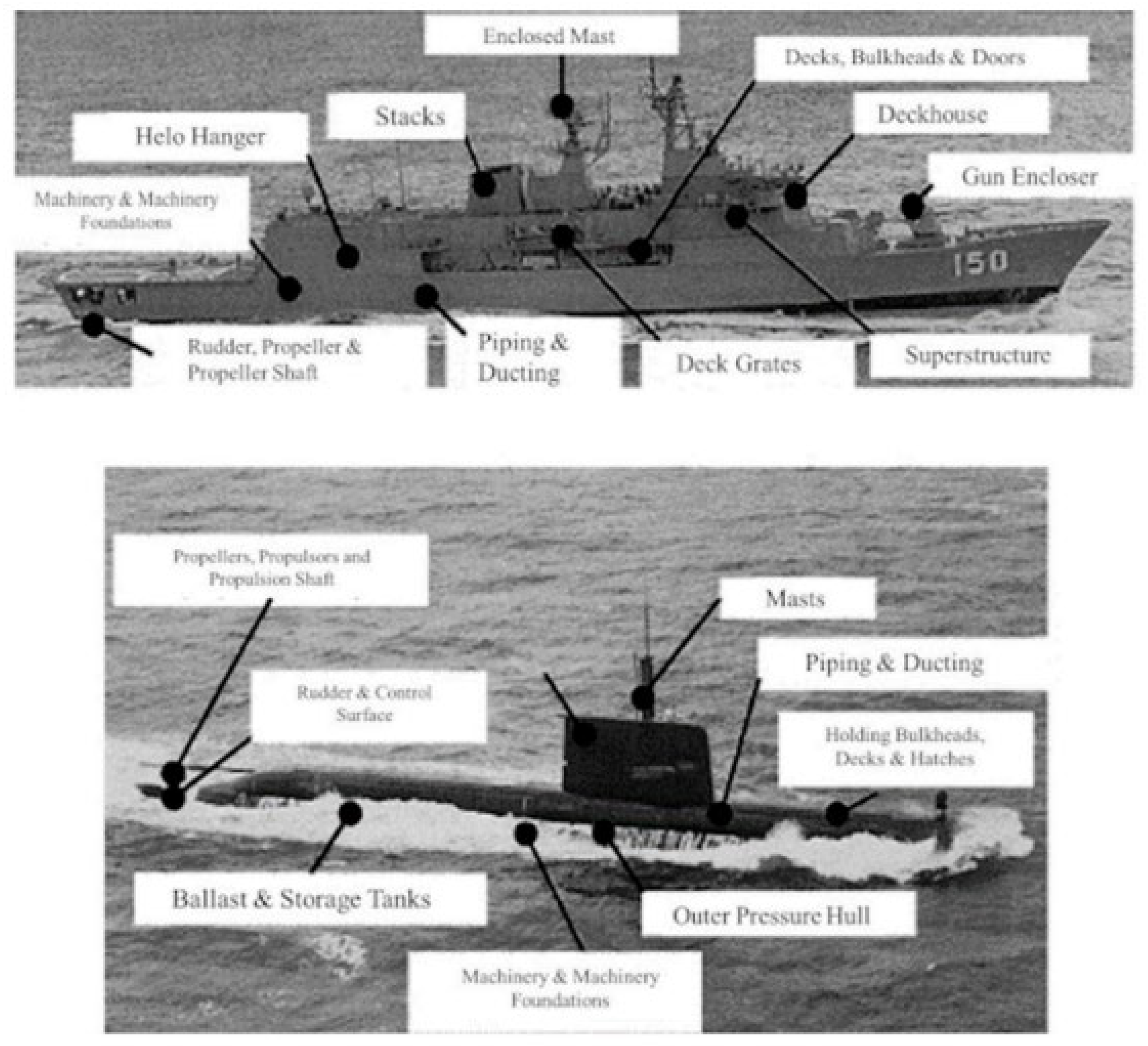

26]. In marine vessels, the use of composite materials has become widespread for reasons such as reducing structural weight, increasing corrosion resistance, and reducing maintenance costs. GFRP has become the standard material in the production of small and medium-sized vessels (yachts, boats, submarine hulls, etc.). Due to its ease of production, low cost, and high resistance to seawater, it is frequently used in hull panels, deck skins, and interior structural elements [

21].

Figure 2 shows the main applications of composite materials in marine vessels.

In contrast, CFRP is more commonly used in high-performance marine vessels. The high specific modulus of carbon fiber significantly reduces the weight of load-bearing structures, thereby improving speed and fuel efficiency. Moreover, the superior fatigue resistance of CFRP ensures long term stability under repetitive impact loads in high speed ships [

28]. However, due to its susceptibility to galvanic corrosion, CFRP should not be used in direct contact with aluminum or steel fasteners; in such cases, surface insulation coatings or interfacial materials are preferred [

29].

Consequently, GFRP and CFRP composite materials used in both offshore wind turbine blades and marine vessels are selected regionally according to engineering requirements. While GFRP provides advantages in terms of cost efficiency and impact tolerance, CFRP stands out with its higher stiffness and strength properties. Nevertheless, verifying these differences not only through theoretical evaluations but also through experimental studies is of great importance. Mechanical tests conducted under varying environmental conditions, loading types, and bonding methods are essential to more reliably determine the long-term performance of both materials.

In this study, single lap bonded specimens made from seven layer glass fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) and eight-layer carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) composite materials were immersed under controlled conditions in seawater obtained from the Aegean Sea, characterized by a temperature of 22 °C and salinity levels between 3.3–3.7%. To evaluate the mechanical strength of the samples, three-point bending tests were performed on composites used in marine environments, while four-point bending tests were conducted on composites applied in offshore wind turbine structures. After testing, microstructural damages and deformations in the interfacial regions of the materials were examined in detail using a high-resolution scanning electron microscope (SEM). The comparative analysis of the results enabled the identification of the initiation stages of microscopic damage in the adhesive interface and revealed in detail the time-dependent effects of the seawater environment on the mechanical properties of composite materials used in both offshore wind turbines and marine applications.

2. Materials and Methods

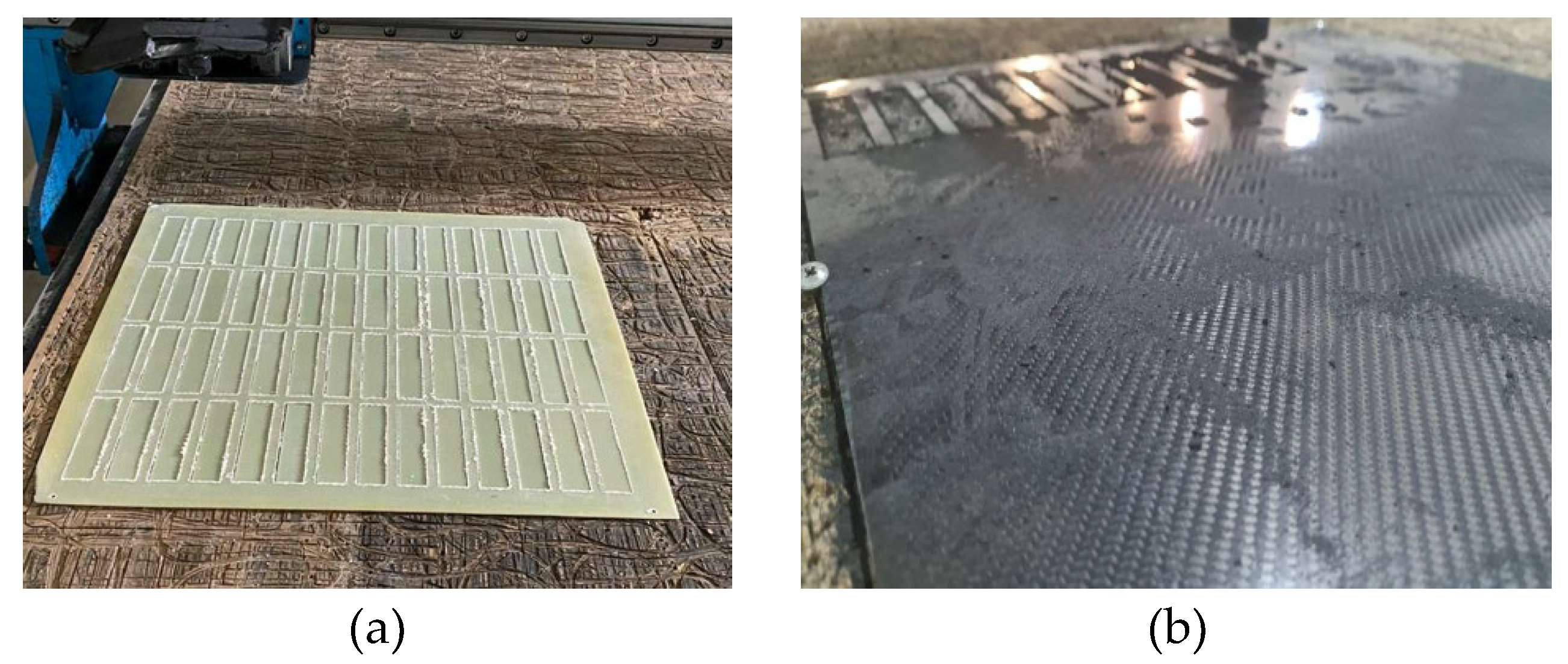

In this study, two types of composite materials glass fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP) and carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) were designed with a 0/90° fiber orientation and a twill weave pattern. The GFRP laminates consisted of seven layers of 390 g/m² glass fibers, while the CFRP laminates were composed of eight layers of 245 g/m² 3K carbon fibers. Both materials used the same epoxy-based resin system (F-RES 21 resin and F-Hard 22 hardener mixed at a 100:21 ratio) and were fabricated using the hand lay-up and hot press method at 120 °C under a pressure of 8–10 bar for 60 minutes.

Prepreg production was performed with a drum-type machine, and the fiber-reinforced sheets were manufactured by Fibermak Engineering Company, located in İzmir, Turkey. The composite laminates were cut into 500 mm × 500 mm sheets using CNC machining, and the final laminate thickness was set to 2 mm (

Figure 3). The mechanical properties of the laminates were determined as follows: tensile strength 80 MPa, tensile modulus 3300 MPa, flexural strength 125 MPa, and flexural modulus 3200 MPa.

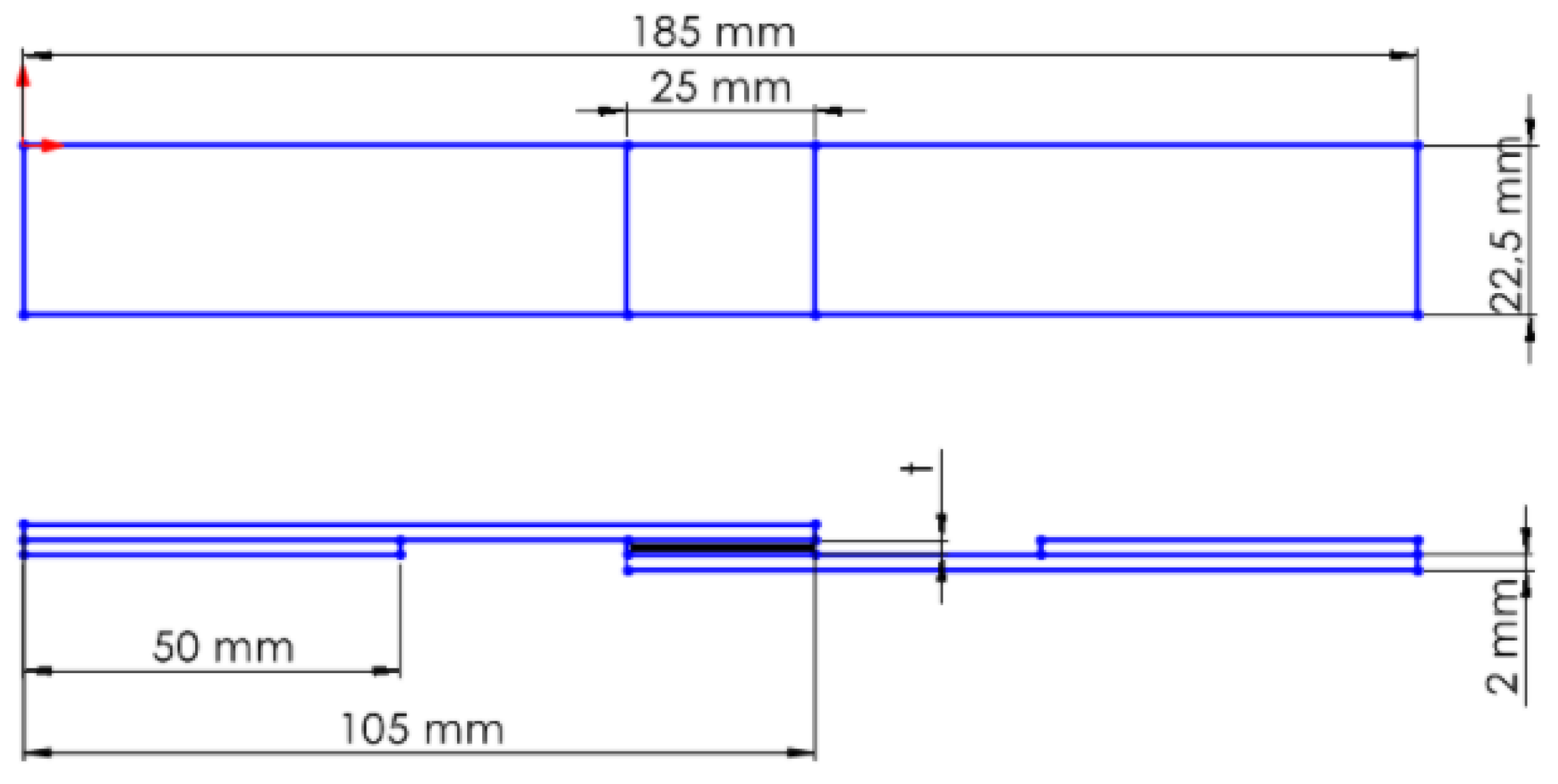

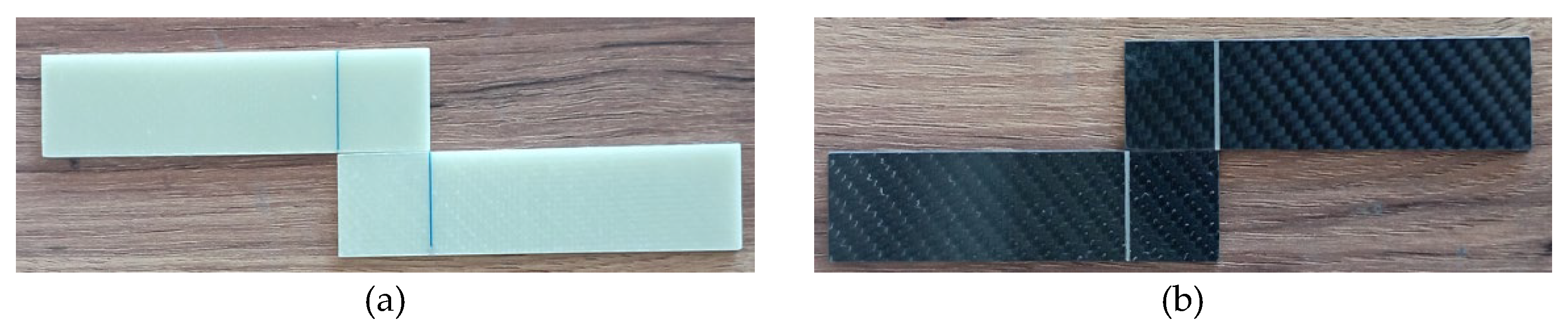

GFRP and CFRP specimens were then cut to the required dimensions in accordance with the ASTM D5868–01 standard [

30] (

Figure 4). Afterwards, 25 mm from the ends of the specimens were measured and marked (

Figure 5).

The samples were prepared by bonding solvent-cleaned surfaces with adhesive. Bonding was achieved with two-component Loctite Hysol-9466 (Alpanhidrolik, Eskişehir, Turkey) epoxy, cured at room temperature and mixed at a 2:1 ratio in the applicator gun (

Figure 6). Literature reports that adhesive layers of 0.1–0.3 mm thick provide high bond strength, while thicknesses greater than 0.6 mm reduce strength [

31].

This is attributed to the fact that thin layers provide more effective mechanical resistance. After bonding, the samples were cured at room temperature for 7 days, in accordance with the product data sheet, and then moved on to the testing phase. This is attributed to the thin adhesive layers’ ability to support mechanical loads more effectively. Application was carried out under a constant pressure of 0.1 MPa and a target thickness of 0.2 mm; the evenness of the adhesive layer was confirmed by measuring it with a digital caliper.

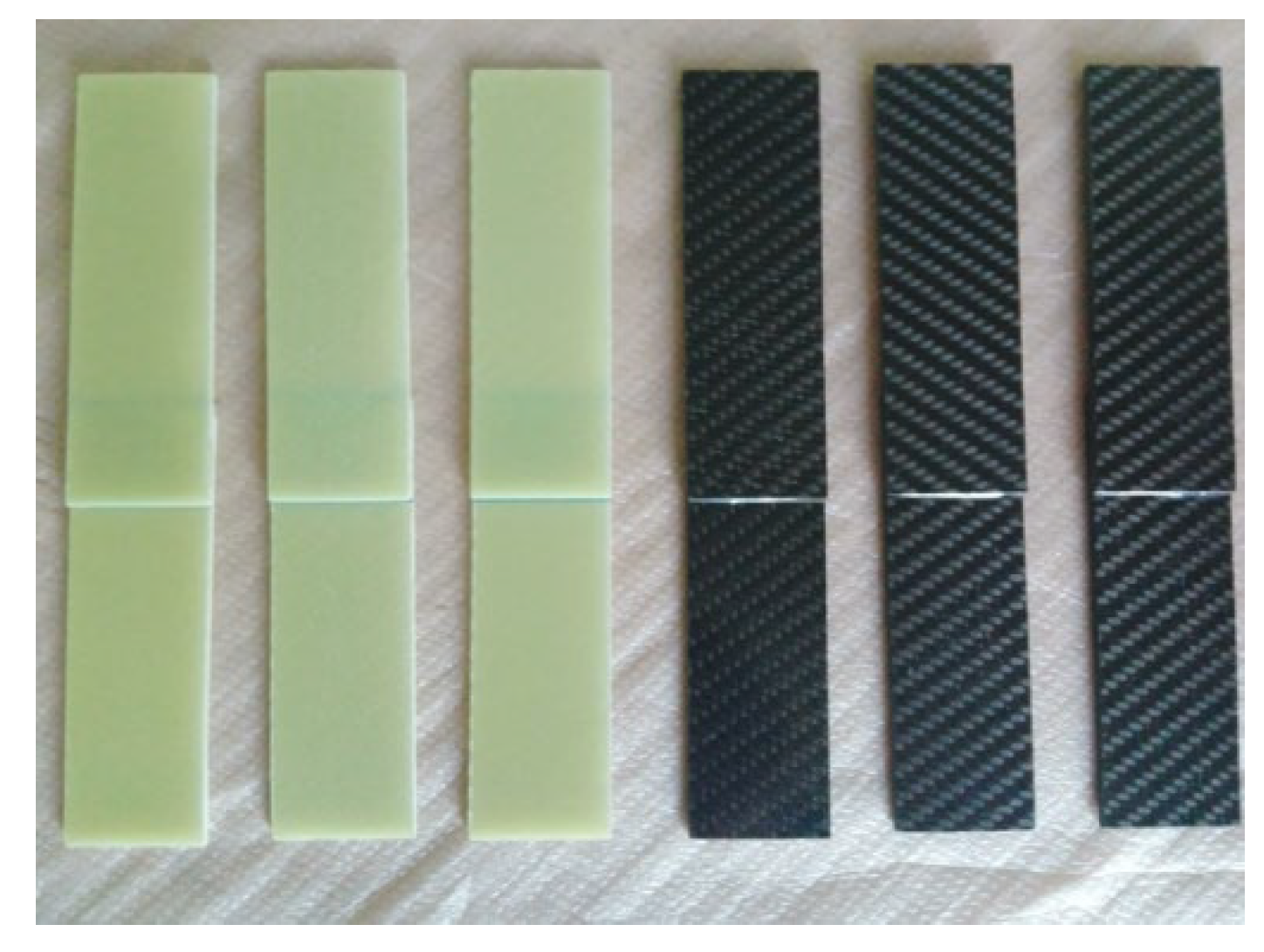

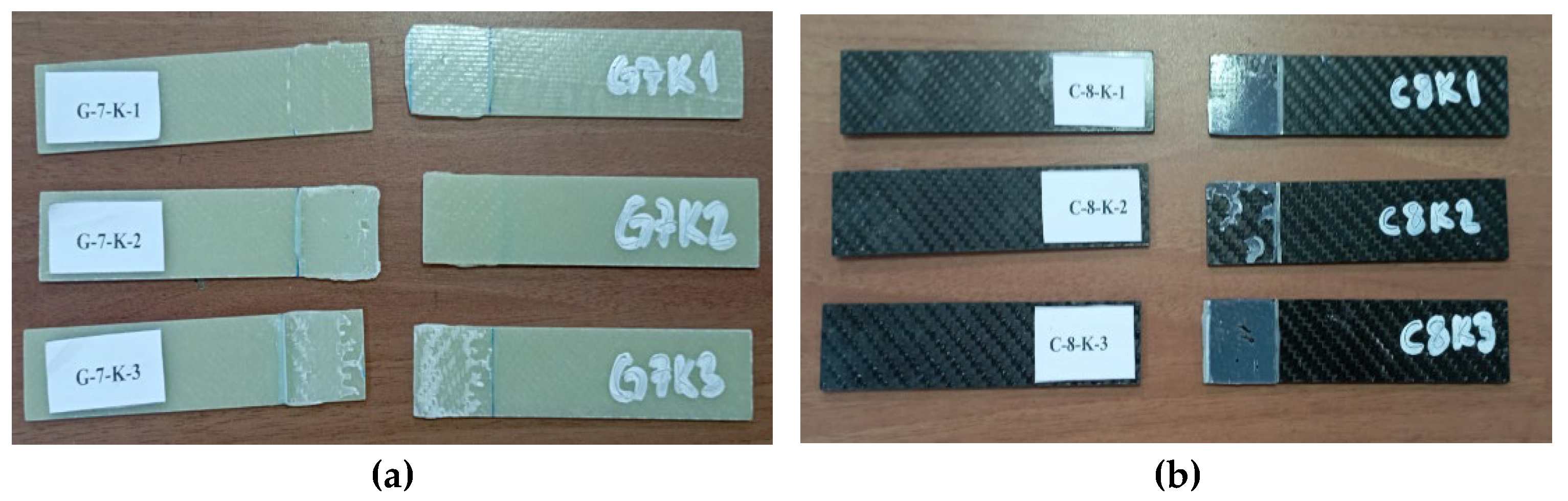

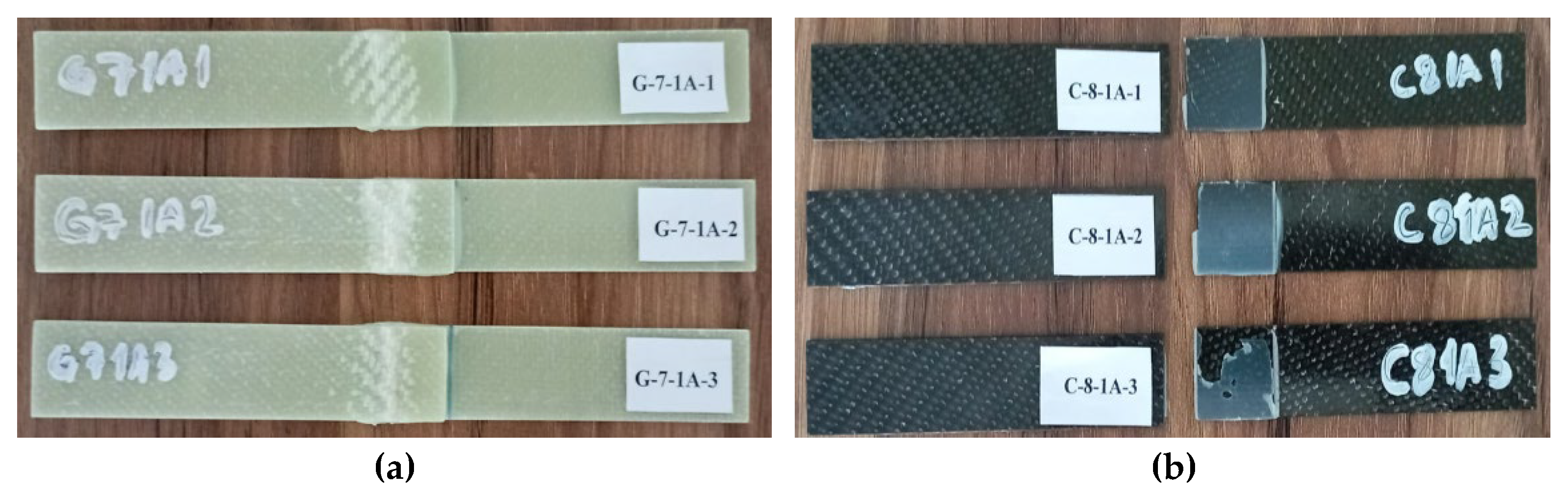

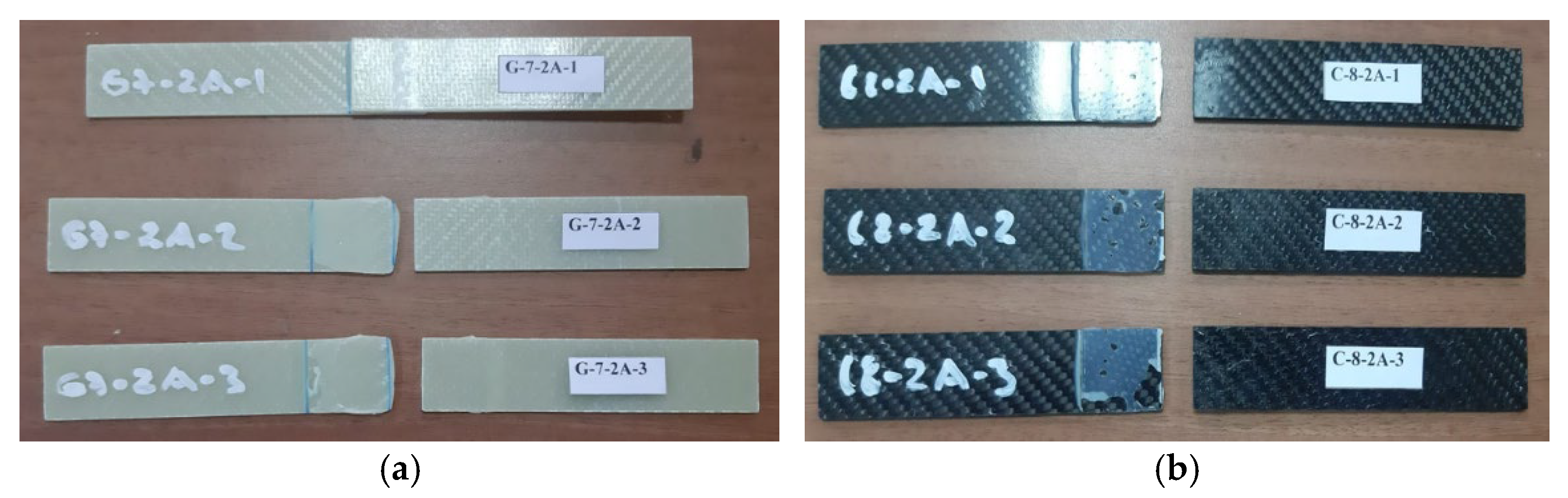

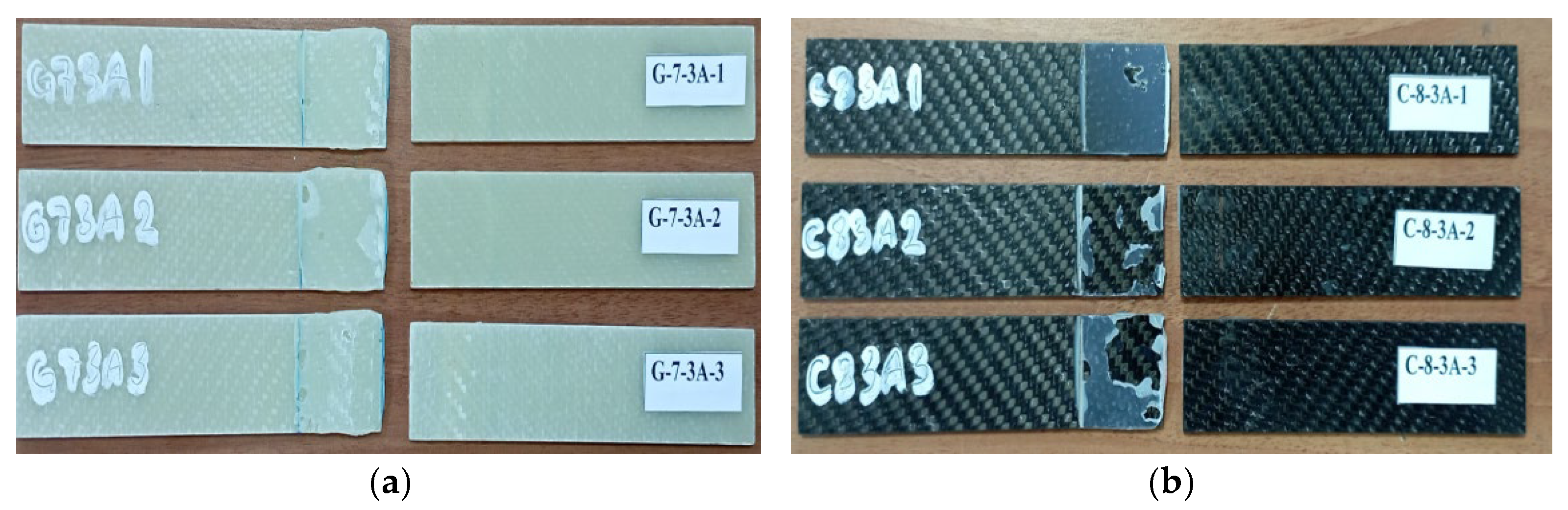

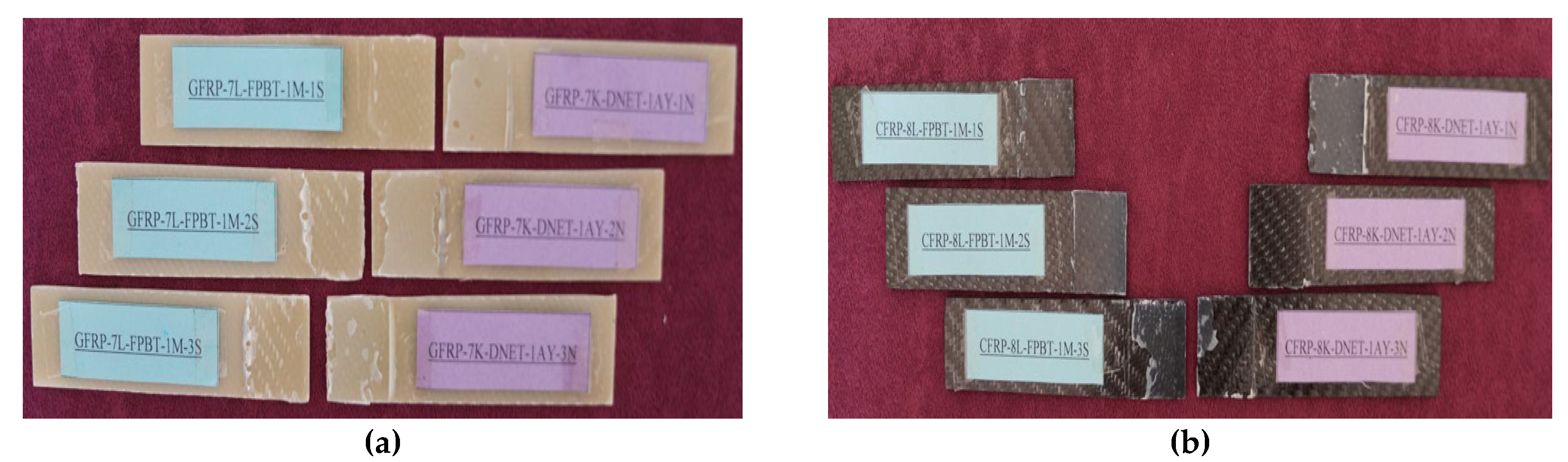

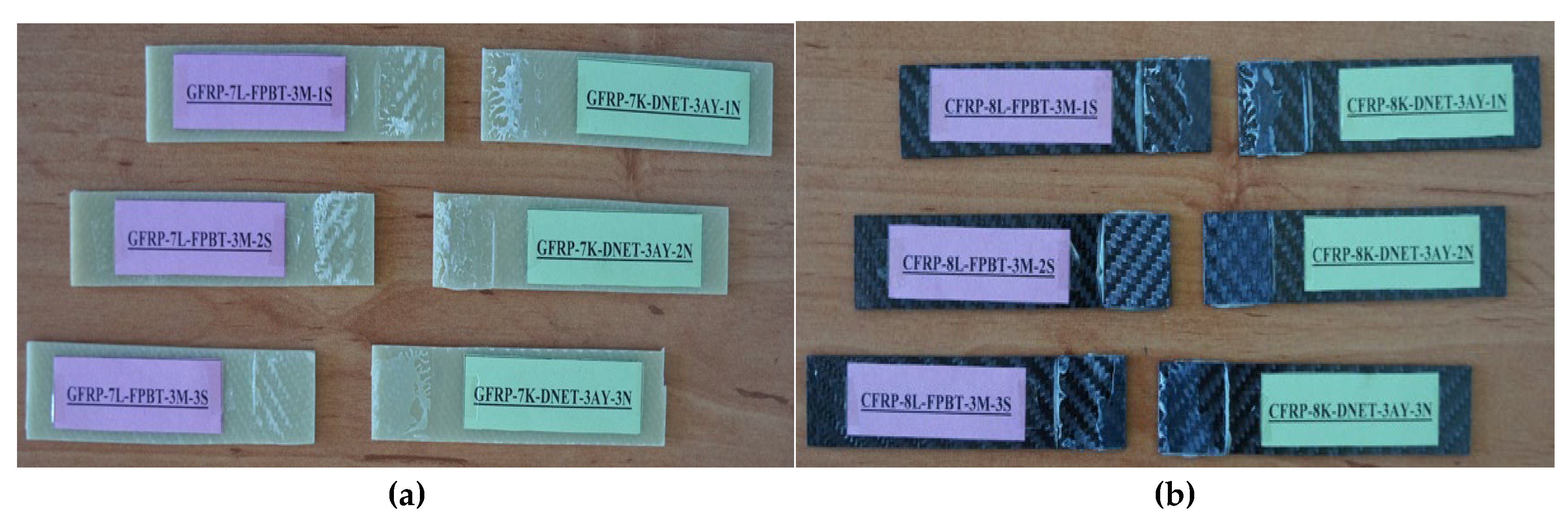

General views of the surface areas of the GFRP and CFRP samples bonded with Loctite Hysol-9466 epoxy adhesive before the three-point and four-point bending tests are presented in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, respectively. At this stage, it is observed that the adhesive layer is evenly distributed and a homogeneous bond is achieved between the samples.

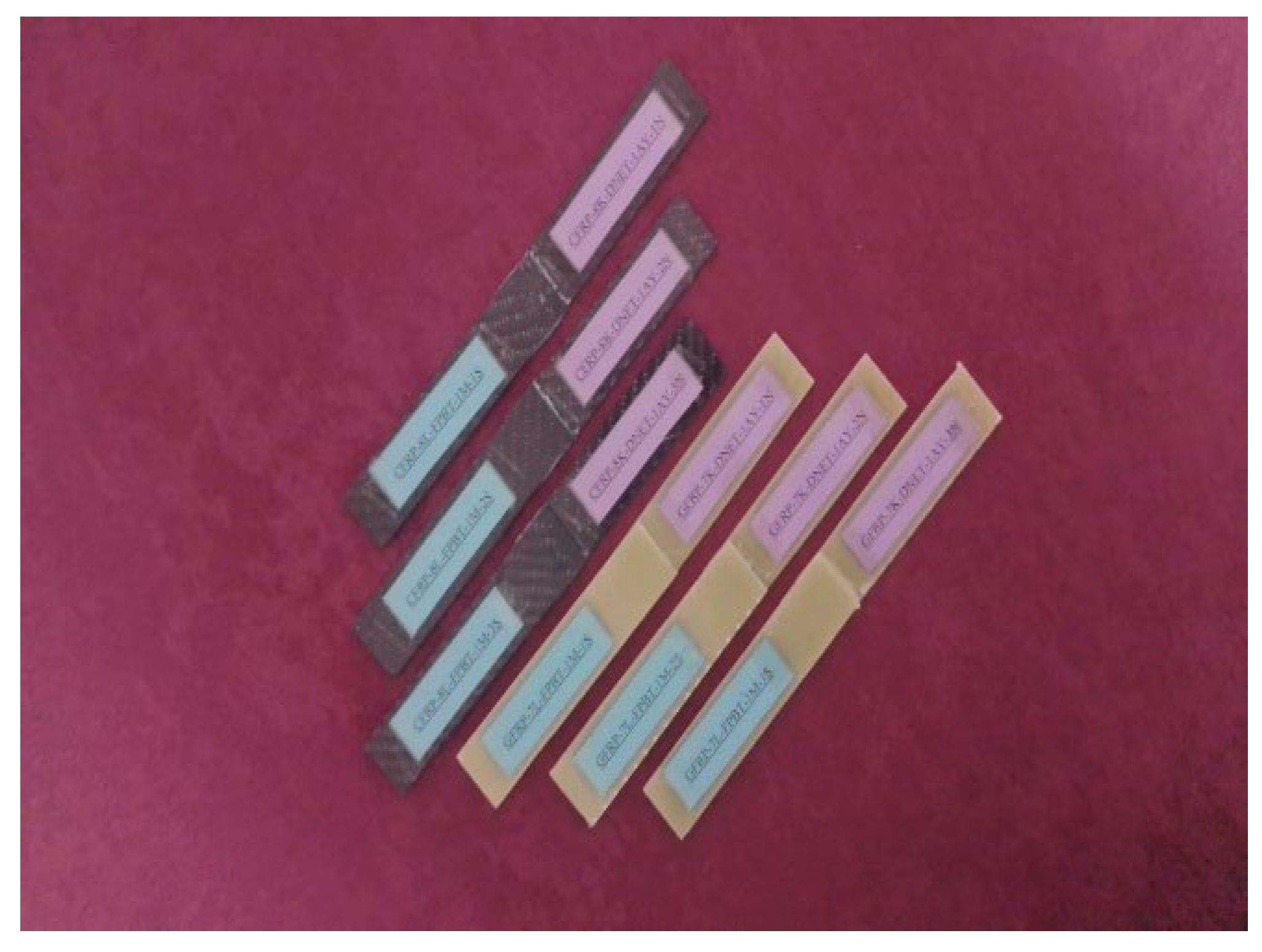

In order to ensure that the experiments were conducted systematically and without confusion, distinctive codes were assigned to each specimen. The coding system used for the specimens tested in the three-point and four-point bending tests was organized to include the material type, number of layers, environmental conditions, and specimen sequence number. The following table presents example codes and explains their meanings (

Table 1).

For instance, the code G-7-K-1 refers to the first specimen made of glass fiber, consisting of seven layers, and tested in a dry environment (not exposed to seawater). Similarly, G-7-1A-1 represents the first specimen with the same properties but exposed to seawater for one month before testing. For the specimens made of carbon fiber, C-8-K-1 denotes the first eight-layer specimen tested under dry conditions (

Figure 9).

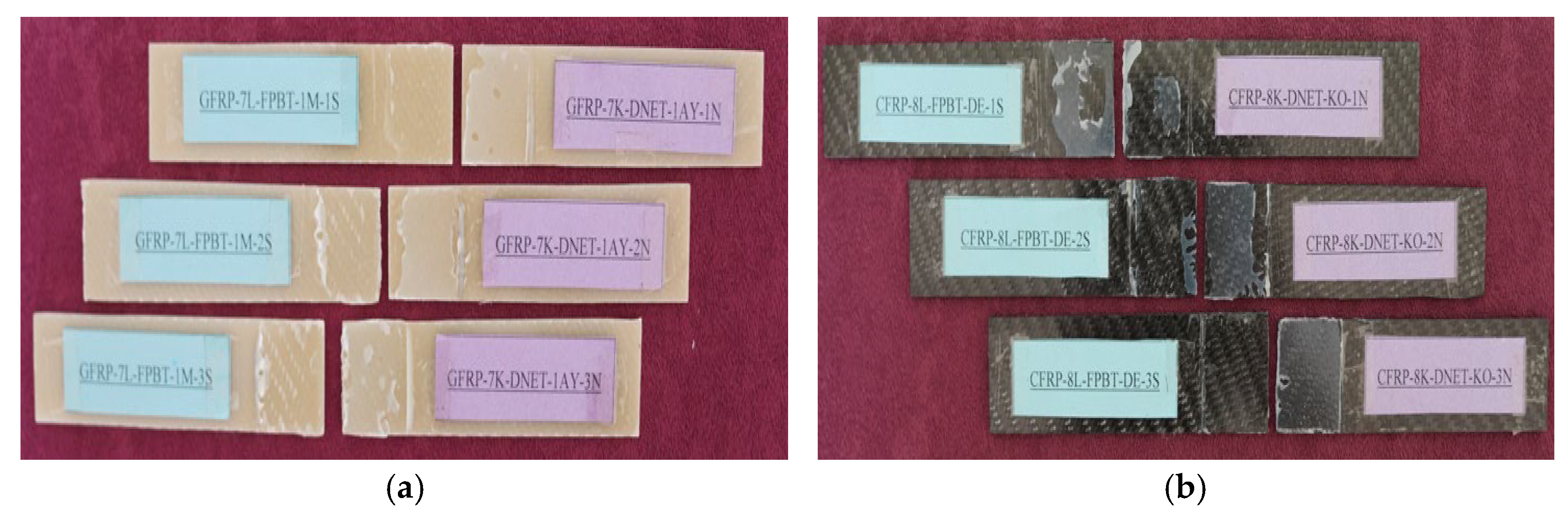

In the specimens subjected to the four-point bending test, the coding system was arranged as follows: for example, GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE-1S represents a specimen made of glass fiber-reinforced polymer (GFRP), consisting of seven layers (7L), tested under the four-point bending test (FPBT), kept in a dry environment (DE not exposed to seawater), and being the first specimen (1S). Similarly, GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M-1S indicates a specimen with the same structural features but immersed in seawater for two months (2M) before testing. For carbon fiber-reinforced specimens, CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE-1S denotes an eight-layer (8L) specimen tested under dry conditions (DE not exposed to seawater) and identified as the first specimen (1S) (

Figure 10).

Samples prepared using the single-lap method were first conditioned in a dry environment for three-point bending tests and then conditioned in seawater for periods of 1, 2, and 3 months, respectively. The same procedure was applied for the four-point bending tests. The seawater medium was prepared with a salinity range of 3.3–3.7% and a constant temperature of 22 °C, and all experiments were conducted under the same conditions (

Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Soaking GFRP and CFRP samples in sea water for 1, 2 and 3 months for three-point bending.

Figure 11.

Soaking GFRP and CFRP samples in sea water for 1, 2 and 3 months for three-point bending.

Figure 12.

Soaking GFRP and CFRP samples in sea water for 1, 2 and 3 months for four-point bending tests.

Figure 12.

Soaking GFRP and CFRP samples in sea water for 1, 2 and 3 months for four-point bending tests.

2.1. Comparative Analysis of Three and Four Point Bending Tests on GFRP and CFRP Composites in Marine Environment and Offshore Wind Turbine Blades

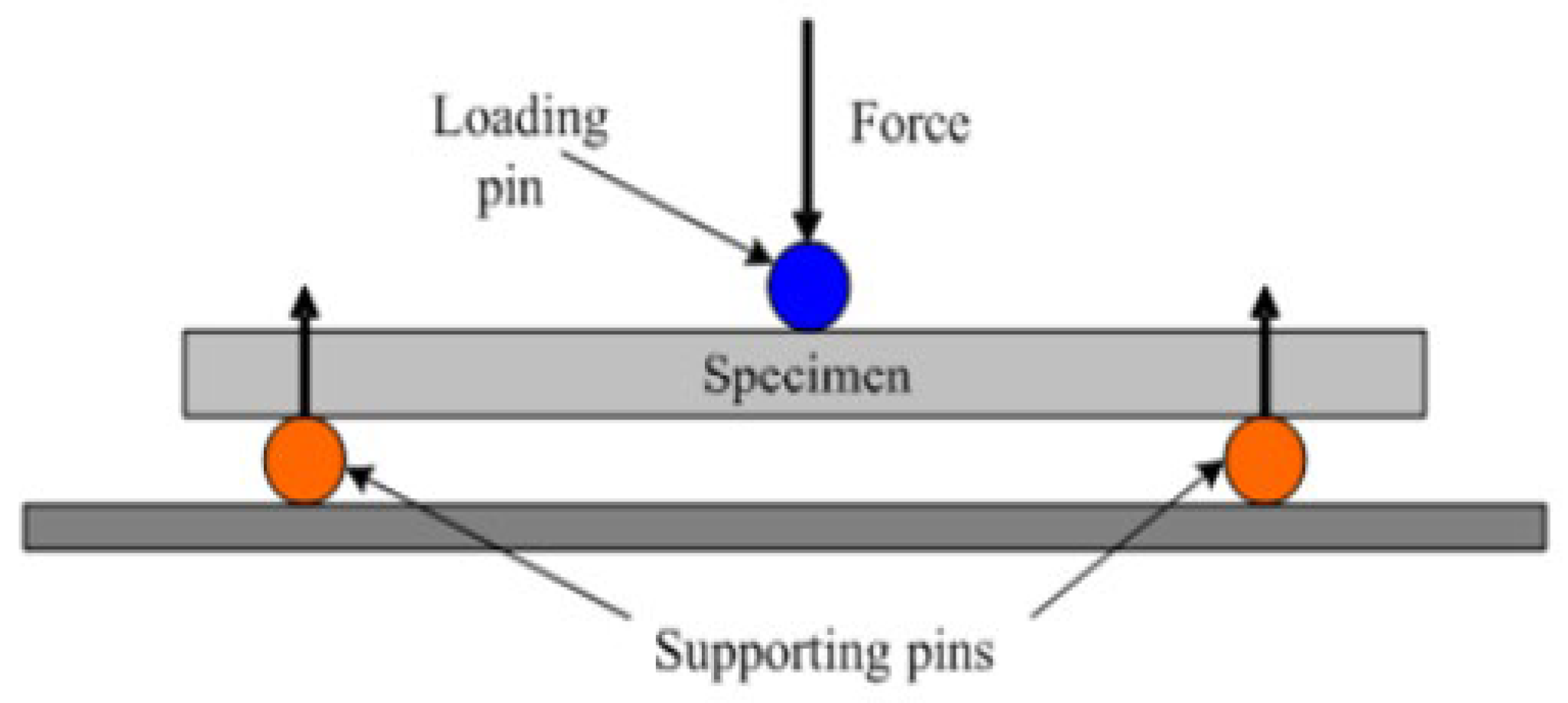

Flexural tests are commonly employed to evaluate the mechanical performance of materials and to determine their characteristic properties such as ductility, flexural strength, yield strength, elastic modulus, and fracture toughness. In the three-point bending test, the specimen is supported at both ends, and deformation is observed under a centrally applied load. This method allows the mechanical behavior of materials with different cross-sectional geometries to be analyzed under the assumption of a simple beam model, considering an ideal moment distribution and negligible shear stresses. In contrast, the four-point bending test involves supporting the specimen at both ends and applying two equal loads, thereby creating a constant moment region that enables a detailed examination of both elastic and plastic deformation behaviors.

In this study, the effects of adhesive type, joint geometry, and composite material type on mechanical performance were comprehensively investigated through both three-point and four-point bending tests. In the three-point bending test, the specimen was supported at both ends, and a load applied at the center generated maximum stress; this condition caused the highest stress to occur in the outermost fibers at the midspan of the beam, thus identifying the region most susceptible to failure under bending (

Figure 13). This test method is particularly useful for determining the damage mechanisms that occur in the adhesive interface and joint regions of single-lap GFRP and CFRP composite joints aged in marine environments, as well as for analyzing time-dependent variations in their mechanical properties.

On the other hand, the four-point bending test was applied to offshore wind turbine blade composites. The presence of a constant moment region enabled a detailed assessment of the specimen’s elastic and plastic behavior (

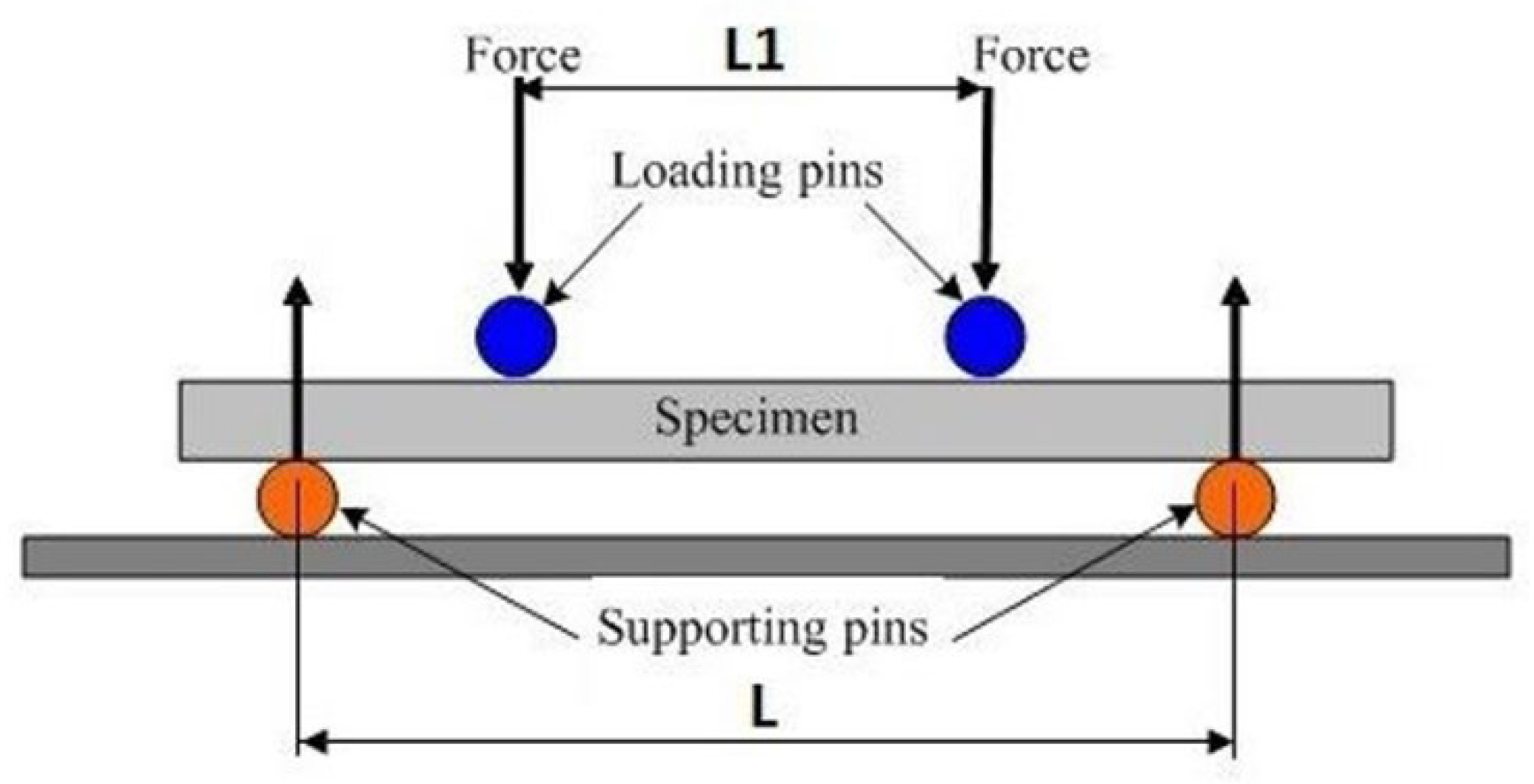

Figure 14). During this test, the maximum stress and strain values occurring at the center of the adhesive-bonded joint specimens were calculated at each load level, allowing for a reliable evaluation of the mechanical performance of the composite joints. Both testing methods provide a systematic and comprehensive approach to analyzing the behavior of different composite materials and bonding parameters under marine environmental conditions.

The following formula is applied to calculate the amount of stress at a particular point on the load-deflection curve.

: stress in the outer fibers at midpoint, MPa

P: load at a given point on the load-deflection curve, N

L: support span, mm

b: width of beam tested, mm

d: depth of beam tested, mm

: strain in the outer surface, mm/mm

D: maximum deflection of the center of the beam, mm

L: support span, mm

D: depth, mm

During the test, the stress and strain values at the center of the adhesively bonded joint specimen were determined at each loading step in the four-point bending test, thus evaluating the material’s mechanical performance.

The following formula is used to calculate the maximum stress value in the area between the loading points in the four-point bending test.

where:

L: Span between supports, mm

a the distance between the applied forces, mm

b: the specimen width, mm

h: the specimen thickness, mm

F: applied force, N

Strain,

the value is calculated using the following formula:

where:

: strain, mm/mm

h: thickness of the specimen, mm

L: support span, mm

a: half the loading span, mm

: deflection at the middle of the span, mm

Both the three-point and four-point bending tests were conducted in the Biomechanics Laboratory of Ege University, Department of Mechanical Engineering, using bending fixtures compatible with a 100 kN capacity Shimadzu AG-100 testing machine. The experiments were performed under a 5 kN load and a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min. All tests were carried out in accordance with the ASTM D790 standard [

26] on smooth GFRP and CFRP single-lap joint specimens with an adhesive thickness of 0.2 mm. The specimens were tested under both dry and seawater-conditioned environments to investigate the effects of environmental exposure on mechanical performance.

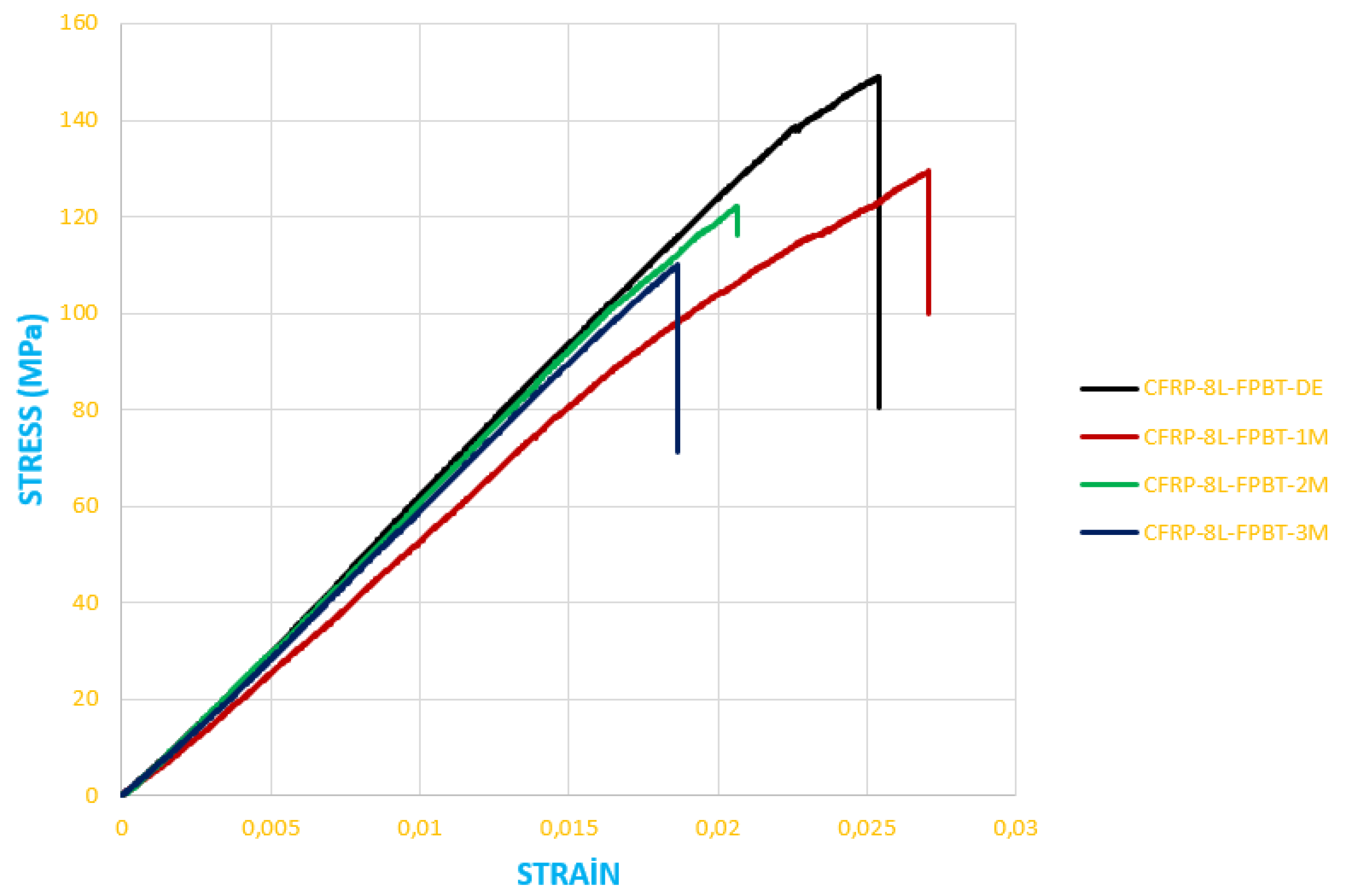

During the three-point bending tests, stress–strain curves were obtained and analyzed based on the experimental data. In the four-point bending tests, parameters such as applied load, test speed, and specimen geometry were defined on the testing system, and measurements were automatically recorded through the test software.

As a result, the influence of environmental factors on the flexural behavior of the adhesive interface was evaluated for all specimens, and variations in mechanical properties were comparatively analyzed based on the experimental findings.

Figure 15 shows the placement of the specimens in the testing machine during both the three-point and four-point bending tests.

A total of 24 connection samples were used within the scope of the experiment, 12 of which were used for the three-point bending test and 12 for the four-point bending test.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The strength of adhesively bonded single-lap GFRP and CFRP joints used in marine environments, particularly in offshore wind turbine blades, is critically dependent on long-term exposure to seawater. Existing studies have generally been conducted under single-material conditions and limited environmental scenarios, leaving the effects of different composite types and seawater exposure largely unexplored.

In this study, GFRP and CFRP specimens were stored both under dry conditions and in natural seawater collected from the Aegean Sea (22 °C, 3.3–3.7% salinity) for 1, 2, and 3 months. Their mechanical behavior and damage characteristics were comparatively evaluated through three-point and four-point bending tests.

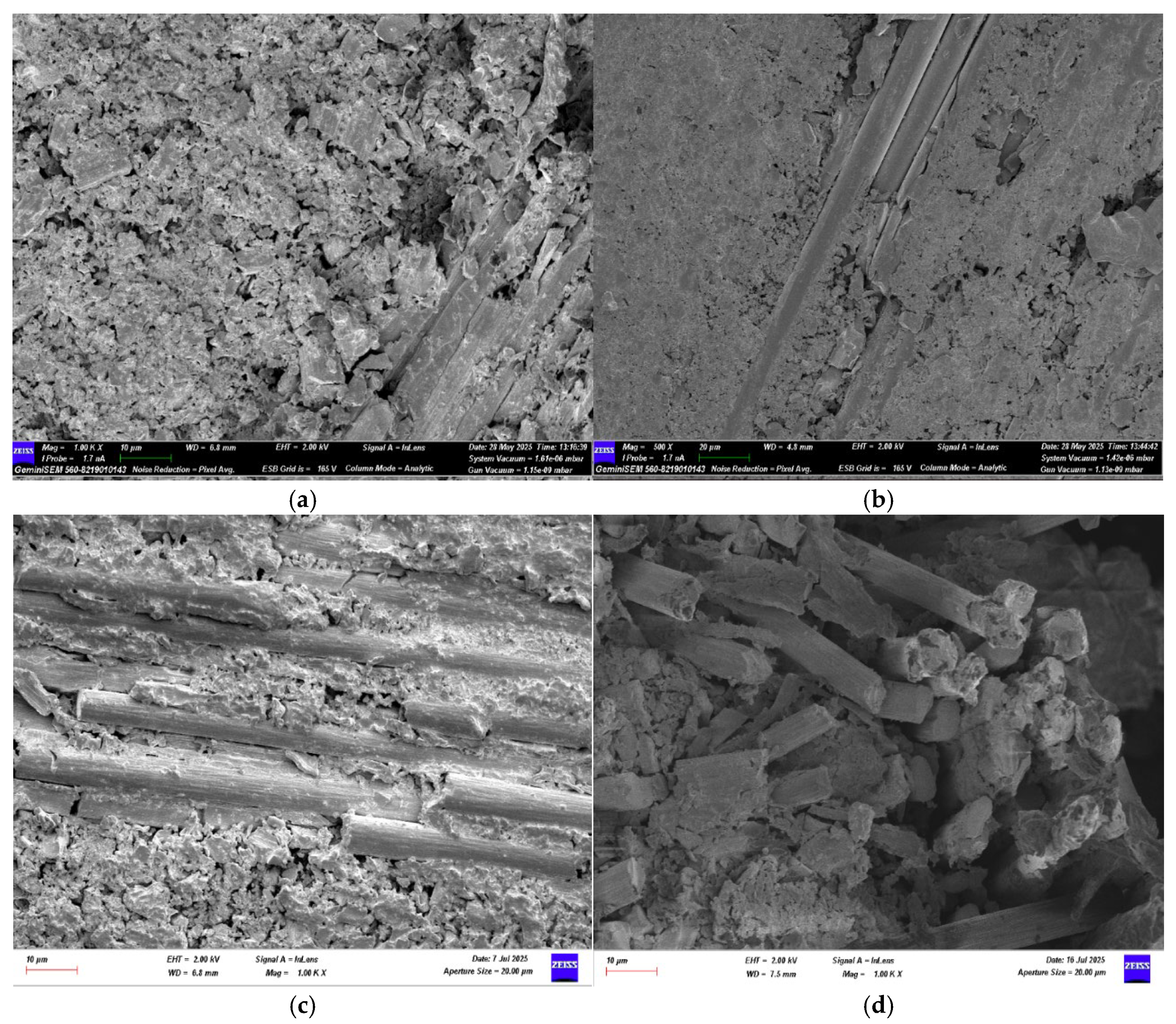

Results from the three-point bending tests showed that the Young’s modulus of GFRP decreased by approximately 13% after 3 months of seawater exposure, whereas the reduction in CFRP was limited to only 3.7%. In GFRP, micro-separations, partial fiber pull-outs, and matrix deformation were observed, while CFRP exhibited minimal damage, maintaining better structural strength. SEM analyses revealed that, in both materials, damage initiated in the matrix phase before propagating to the fiber phase, with CFRP maintaining a more uniform fiber–matrix interfacial bond compared to GFRP.

A similar trend was observed in the four-point bending tests. GFRP’s Young’s modulus decreased by 9.5%, whereas the reduction in CFRP remained limited to 3.5%. In GFRP, cracks and layer delaminations progressed gradually, whereas CFRP demonstrated more homogeneous load transfer and controlled fracture. Seawater exposure in GFRP led to interfacial weakening and microvoid formation, whereas the adhesive–layer bond in CFRP remained largely intact, resulting in fracture at higher load levels. The use of F-RES 21 epoxy resin and F-Hard 22 hardener contributed to preserving structural integrity in both material groups.

Overall, both three-point and four-point bending tests demonstrated that CFRP joints are more resistant to seawater exposure compared to GFRP, offering higher mechanical strength and structural stability. While stress concentration at a single point in three-point bending led to local and sudden damage, the broader load transfer in four-point bending allowed for more uniform distribution of damage.

Figure 1.

Material types according to structural components of wind turbine blade [

25].

Figure 1.

Material types according to structural components of wind turbine blade [

25].

Figure 2.

Applications of composite materials used in marine vessels [

27].

Figure 2.

Applications of composite materials used in marine vessels [

27].

Figure 3.

Machining of GFRP and CFRP Samples by CNC Router.

Figure 3.

Machining of GFRP and CFRP Samples by CNC Router.

Figure 4.

Schematic Representation of GFRP and CFRP single lap configurations.

Figure 4.

Schematic Representation of GFRP and CFRP single lap configurations.

Figure 5.

Marking of GFRP and CFRP single lap configurations.

Figure 5.

Marking of GFRP and CFRP single lap configurations.

Figure 6.

Bonding Process of GFRP and CFRP Specimens Using Loctite Hysol-9466.

Figure 6.

Bonding Process of GFRP and CFRP Specimens Using Loctite Hysol-9466.

Figure 7.

Visual observation of the surface morphology of GFRP and CFRP specimens prior to the three-point bending test.

Figure 7.

Visual observation of the surface morphology of GFRP and CFRP specimens prior to the three-point bending test.

Figure 8.

Visual observation of the surface morphology of GFRP and CFRP specimens prior to the four-point bending test.

Figure 8.

Visual observation of the surface morphology of GFRP and CFRP specimens prior to the four-point bending test.

Figure 9.

GFRP (a) and CFRP (b) specimen configurations used during the three-point bending test.

Figure 9.

GFRP (a) and CFRP (b) specimen configurations used during the three-point bending test.

Figure 10.

GFRP (a) and CFRP (b) specimen configurations used during the four-point bending test.

Figure 10.

GFRP (a) and CFRP (b) specimen configurations used during the four-point bending test.

Figure 13.

Schematic view of the three point bending test conditions.

Figure 13.

Schematic view of the three point bending test conditions.

Figure 14.

Schematic view of the four point bending test conditions.

Figure 14.

Schematic view of the four point bending test conditions.

Figure 15.

Placement of the sample in the three-point bending test (a), placement of the sample in the four-point bending test(b).

Figure 15.

Placement of the sample in the three-point bending test (a), placement of the sample in the four-point bending test(b).

Figure 16.

Views of the G-7-K sample after the three-point bending test (a) and the C-8-K sample after the test (b).

Figure 16.

Views of the G-7-K sample after the three-point bending test (a) and the C-8-K sample after the test (b).

Figure 17.

Views of the G-7-1A sample after the three-point bending test (a) and the C-8-1A sample after the test (b).

Figure 17.

Views of the G-7-1A sample after the three-point bending test (a) and the C-8-1A sample after the test (b).

Figure 18.

Views of G-7-2A sample (a) and C-8-1A sample (b) after three-point bending test.

Figure 18.

Views of G-7-2A sample (a) and C-8-1A sample (b) after three-point bending test.

Figure 19.

Views of G-7-3A sample (a) and C-8-3A sample (b) after three-point bending test.

Figure 19.

Views of G-7-3A sample (a) and C-8-3A sample (b) after three-point bending test.

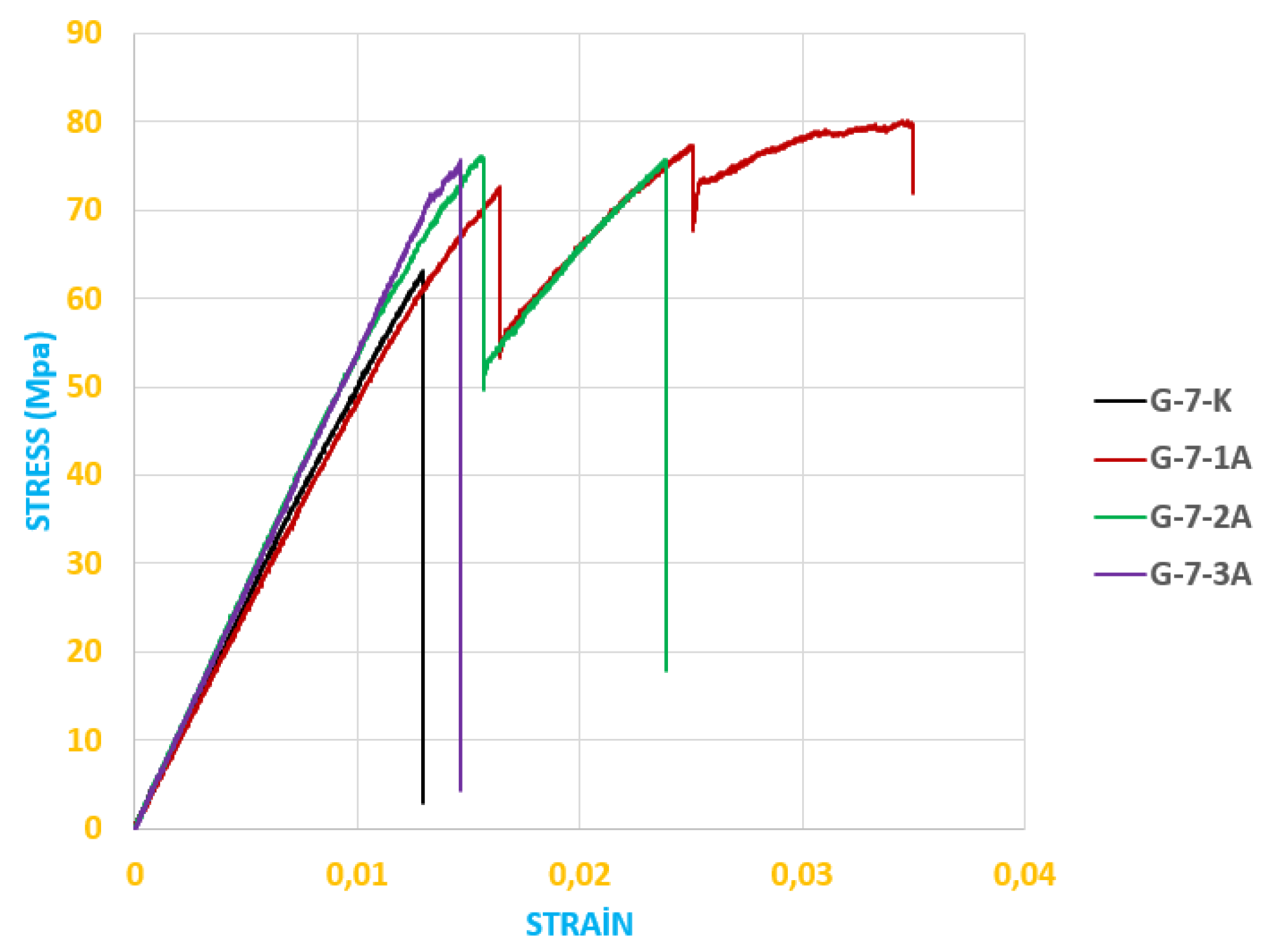

Figure 20.

Stress–strain curves of GFRP specimens exposed to seawater for different durations and stored under dry conditions.

Figure 20.

Stress–strain curves of GFRP specimens exposed to seawater for different durations and stored under dry conditions.

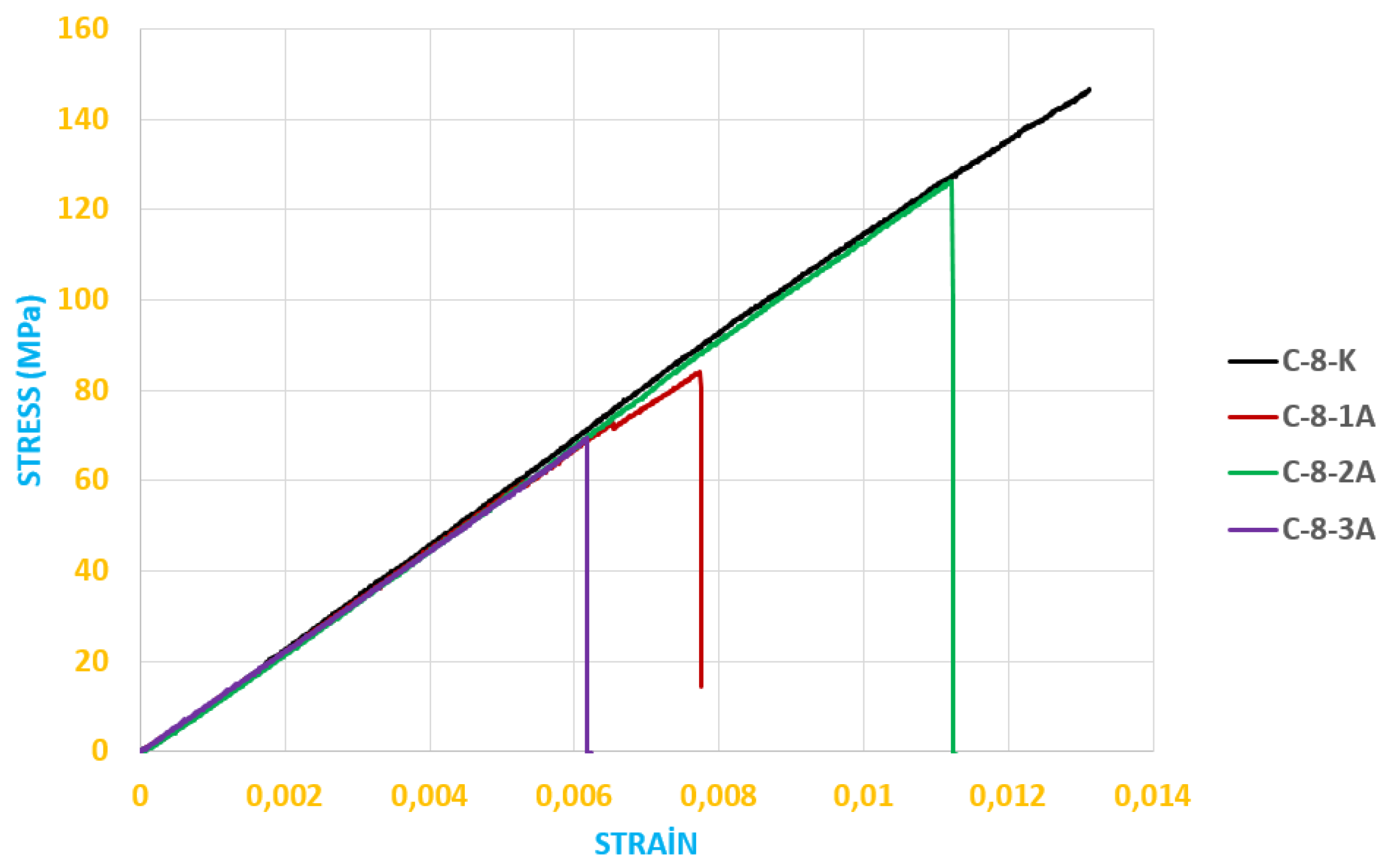

Figure 21.

Stress–strain curves of CFRP specimens exposed to seawater for different durations and stored under dry conditions.

Figure 21.

Stress–strain curves of CFRP specimens exposed to seawater for different durations and stored under dry conditions.

Figure 22.

Views of the GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE-1S specimen (a) and CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE-1S specimen (b) after the four-point bending test.

Figure 22.

Views of the GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE-1S specimen (a) and CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE-1S specimen (b) after the four-point bending test.

Figure 23.

GFRP-7L-FPBT-1M numunesi (a) ve CFRP-8L-FPBT-1M numunesinin (b) dört nokta eğme test sonrası görünümleri.

Figure 23.

GFRP-7L-FPBT-1M numunesi (a) ve CFRP-8L-FPBT-1M numunesinin (b) dört nokta eğme test sonrası görünümleri.

Figure 24.

Views of the GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M specimen (a) and CFRP-8L-FPBT-2M specimen (b) after the four-point bending test.

Figure 24.

Views of the GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M specimen (a) and CFRP-8L-FPBT-2M specimen (b) after the four-point bending test.

Figure 25.

Views of GFRP-7L-FPBT-3M specimen (a) and CFRP-8L-FPBT-3M specimen (b) after four-point bending test.

Figure 25.

Views of GFRP-7L-FPBT-3M specimen (a) and CFRP-8L-FPBT-3M specimen (b) after four-point bending test.

Figure 26.

Stress–strain curves of GFRP specimens exposed to seawater for different durations and stored under dry conditions.

Figure 26.

Stress–strain curves of GFRP specimens exposed to seawater for different durations and stored under dry conditions.

Figure 27.

Stress–strain curves of CFRP specimens exposed to seawater for different durations and stored under dry conditions.

Figure 27.

Stress–strain curves of CFRP specimens exposed to seawater for different durations and stored under dry conditions.

Figure 28.

Reference (dry condition) (a), 1 month (b), 2 months (b), 3 months (c) seawater-exposed GFRP specimens.

Figure 28.

Reference (dry condition) (a), 1 month (b), 2 months (b), 3 months (c) seawater-exposed GFRP specimens.

Figure 29.

Reference (dry condition) (a), 1 month (b), 2 months (b), 3 months (c) seawater-exposed CFRP specimens.

Figure 29.

Reference (dry condition) (a), 1 month (b), 2 months (b), 3 months (c) seawater-exposed CFRP specimens.

Figure 30.

Reference (dry condition) (a), 1 month (b), 2 months (c), 3 months (d) seawater-exposed GFRP specimens.

Figure 30.

Reference (dry condition) (a), 1 month (b), 2 months (c), 3 months (d) seawater-exposed GFRP specimens.

Figure 31.

Reference (dry condition) (a), 1 month (b), 2 months (c), 3 months (d) seawater-exposed CFRP specimens.

Figure 31.

Reference (dry condition) (a), 1 month (b), 2 months (c), 3 months (d) seawater-exposed CFRP specimens.

Table 1.

Coding System for GFRP and CFRP Specimens for Three and Four-Point Bending Tests.

Table 1.

Coding System for GFRP and CFRP Specimens for Three and Four-Point Bending Tests.

| Code |

Test Type |

Description

|

| G-7-K-1 |

Three-Point Bending |

Glass fiber (G), 7 layers, tested in dry condition(K), specimen 1 |

| G-7-1A-1 |

Three-Point Bending |

Glass fiber(G), 7 layers, conditioned in seawater for 1 month (1A), specimen 1 |

| C-8-K-1 |

Three-Point Bending |

Carbon fiber (C), 8 layers, tested in dry condition(K), specimen 1 |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE-1S |

Four-Point Bending |

Glass fiber (GFRP), 7 layers (7L), four-point bending test (FPBT), dry condition (DE), specimen 1(1S) |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M-1S |

Four-Point Bending |

Glass fiber (GFRP), 7 layers (7L), four-point bending test (FPBT), 2 months in seawater (2M), specimen 1 (1S) |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE-1S |

Four-Point Bending |

Carbon fiber (CFRP), 8 layers (8L), four-point bending test (FPBT), dry condition (DE), specimen 1(1S) |

Table 2.

Bending Stress and Strain Values of GFRP Specimens.

Table 2.

Bending Stress and Strain Values of GFRP Specimens.

| Specimen Code |

Exposure Time |

Flexural Stress (MPa) |

Strain (ε) |

Description/Status |

| G-7-K |

Dry (Reference) |

63.0726 |

0.0129 |

Maximum stress value |

G-7-1A

|

1 month

|

72.2704 |

0.0163 |

Initial stress |

| 54.4886 |

0.0113 |

Minimum stress |

| 80.0818 |

0.0347 |

Maximum stress |

G-7-2A

|

2 months |

75.8136 |

0.0156 |

Initial maximum stress |

| 50.8163 |

0.0094 |

Stress reduction |

| 75.6766 |

0.0154 |

Stress increase |

| G-7-3A |

3 months |

75.6723 |

0.0146 |

Initial maximum stress |

Table 3.

Bending Stress and Strain Values of CFRP Specimens.

Table 3.

Bending Stress and Strain Values of CFRP Specimens.

| Specimen Code |

Exposure Time |

Flexural Stress (MPa) |

Strain (ε) |

Description/Status |

| C-8-K |

Dry (Reference) |

146.5976 |

0.0131 |

Maximum bending stress |

C-8-1A |

1 month |

72.4395 |

0.0065 |

Initial stress |

| 83.6555 |

0.0077 |

Maximum stress |

| C-8-2A |

2 months |

126.2889 |

0.0112 |

Initial and maximum stress |

| C-8-3A |

3 months |

69.1586 |

0.0061 |

Bending stress |

Table 4.

Young’s Modulus (E) of GFRP and CFRP specimens.

Table 4.

Young’s Modulus (E) of GFRP and CFRP specimens.

| Sample Code |

Material Type |

Elastic Modulus (E) (GPa) |

Change Compared to Reference (%) |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE |

GFRP |

3.840 |

Dry environment (reference) |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-1M |

GFRP |

3.856 |

% 3.15 |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M |

GFRP |

3.843 |

% 6.42 |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-3M |

GFRP |

5.213 |

% 9.45 |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE |

CFRP |

6.270 |

Dry environment (reference) |

|

CFRP-8L-FPBT-1M

|

CFRP |

5.380 |

% 1.29 |

|

CFRP-8L-FPBT-2M

|

CFRP |

6.169 |

% 2.62 |

|

CFRP-8L-FPBT-3M

|

CFRP |

6.036 |

% 3.48 |

Table 5.

Bending Stress and Strain Values of GFRP Specimens.

Table 5.

Bending Stress and Strain Values of GFRP Specimens.

| Specimen Code |

Exposure Time |

Flexural Stress (MPa) |

Strain (ε) |

Description/Status |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE |

Dry (Reference) |

121.6930 |

0.0395 |

Maximum bending stress |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-1M |

1 month |

114.9519 |

0.0323 |

Initial stress |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M |

2 months |

92.6155 |

0.0244 |

Highest stress |

| GFRP-7L-FPBT-3M |

3 months |

72.7945 |

0.0146 |

Lowest stress |

Table 6.

Bending Stress and Strain Values of CFRP Samples.

Table 6.

Bending Stress and Strain Values of CFRP Samples.

| Specimen Code |

Exposure Time |

Flexural Stress (MPa) |

Strain (ε) |

Description/Status |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE |

Dry (Reference) |

148.5722 |

0.0254 |

Maximum bending stress |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-1M |

1 month |

12.2385 |

0.0270 |

Slight increase in flexibility at the beginning (matrix softening) |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-2M |

2 months |

121.9446 |

0.0206 |

Tendency of stress reduction |

| CFRP-8L-FPBT-3M |

3 months |

109.5578 |

0.0185 |

Noticeable mechanical degradation |

Table 7.

Young’s Modulus (E) of GFRP and CFRP specimens.

Table 7.

Young’s Modulus (E) of GFRP and CFRP specimens.

| Sample Code |

Material Type |

Elastic Modulus (E) (GPa) |

Change Compared to Reference (%) |

| G-7-K |

GFRP |

5.39 |

Dry environment (reference) |

| G-7-1A |

GFRP |

5.07 |

% 5.94 |

| G-7-2A |

GFRP |

4.91 |

% 8.90 |

| G-7-3A |

GFRP |

4.69 |

% 12.98 |

| C-8-K |

CFRP |

11.50 |

Dry environment (reference) |

| C-8-1A |

CFRP |

11.36 |

% 1.28 |

| C-8-2A |

CFRP |

11.11 |

% 3.39 |

| C-8-3A |

CFRP |

11.07 |

% 3.74 |

Table 8.

Comparison of the Results of Three-Point Bending and Four-Point Bending Tests.

Table 8.

Comparison of the Results of Three-Point Bending and Four-Point Bending Tests.

| Condition |

Three-Point Bending Results |

Four-Point Bending Results |

| Dry Environment (Reference) |

The G-7-K and C-8-K specimens were isolated from environmental effects. Damage occurred solely due to mechanical bending. In G-7-K, separations along the bond line caused by tensile stresses were observed. In the C-8-K specimens, surface gloss and integrity were preserved. |

In the GFRP-7L-FPBT-DE-1S and CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE-1S specimens, damage initiated at the bond line and progressed towards the surfaces. Gradual (not sudden) fracture was observed. Stress concentration was evident in the CFRP-8L-FPBT-DE-1S specimens. |

| Samples Soaked in Seawater for 1 Month |

G-7-1A: No significant rupture at the bond line, but microseparations (whitening) occurred at the fiber-matrix interface. G-7-1A demonstrated a certain degree of ductility. C-8-1A: Sudden and brittle ruptures were observed at the bond line, with adhesion partially preserved in some samples. |

GFRP-7L-FPBT-1M: Weakening, microcracks, and delamination occurred at the interface due to the ionization effect of seawater. CFRP-8L-FPBT-1M: Due to low water absorption, the bond line maintained its stability, but it exhibited brittle behavior at the time of fracture. |

| Samples Soaked in Seawater for 2 Months |

GFRP (G-7-2A): Significant fractures and bond weaknesses were observed along the bond line. CFRP (C-8-2A): Local cracks, adhesive separation, and partial voids were observed at the bond line. The structural integrity of the CFRP specimens was better preserved than that of the GFRP specimens. |

GFRP-7L-FPBT-2M: Adhesive residue was observed at the bond line and on the surfaces. Mixed failure (adhesive + cohesive) occurred. CFRP-8L-FPBT-2M: Similar mixed failure was observed. Fiber reinforcement provided more balanced load transfer. |

| Samples Soaked in Seawater for 3 Months |

GFRP (G-7-3A): Damage progressed directly along the bond line, decreasing bond line strength. The adhesive layer became plastic, creating microscopic voids. CFRP (C-8-3A): Similar damage but more limited; cohesive and adhesive failure were observed simultaneously. |

GFRP-7L-FPBT-3M: Damage was concentrated at the bond line, and the adhesive was observed to have partially adhered to both surfaces. Strength decreased due to seawater weakening the polymer structure. CFRP-8L-FPBT-3M: Similar fracture type but less severe damage. Bond quality was largely maintained. |

Table 9.

Performance Analysis of Three-Point and Four-Point Bending Test Results.

Table 9.

Performance Analysis of Three-Point and Four-Point Bending Test Results.

| Observation |

Three-Point Bending |

Four-Point Bending |

| Damage Initiation |

Typically initiates along the bond line, especially at the edge regions. |

Initiates at the bond line and propagates toward the surfaces. |

| Type of Damage |

Over time, adhesive and cohesive failures are observed simultaneously. |

Mixed-mode failure (adhesive + cohesive) is dominant. |

| Effect of Seawater |

Rapid degradation is seen in GFRP specimens, while the effect is limited in CFRP specimens. |

In GFRP specimens, chemical and physical degradation occurs, whereas in CFRP specimens, low water absorption helps preserve strength. |

| Fracture Behavior |

GFRP specimens exhibit ductile–mixed behavior; CFRP specimens show brittle behavior. |

GFRP: delamination observed; CFRP: sudden but controlled fracture observed. |

| Preservation of Structural Strength |

CFRP > GFRP |

CFRP > GFRP |

| Result of Long-Term Exposure |

Adhesive strength decreases significantly in GFRP specimens.

|

CFRP specimens maintain structural integrity for a longer period. |