1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

The vast ocean is rich in resources, including oil and gas, minerals, biological and renewable energy, and the development and utilization of these resources are of great significance to the sustainable development of human society. The core tools for carrying out underwater exploration tasks are underwater robots, whose development level directly decides the depth, width and efficiency of underwater exploration. Underwater robots are mainly divided into Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROV) and Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV) based on whether they are controlled in real time or not [

1]. ROVs rely on cables and real-time control by operators. Although they have a certain degree of intuitiveness in operation, their range of motion is limited due to the existence of this cable. In contrast, AUVs have a high degree of autonomy and can independently complete a series of complex tasks such as navigation, obstacle avoidance, reconnaissance and sampling based on the information sensed by the sensors they carry and the preset mission objectives, greatly expanding the depth, breadth and duration of underwater operations [

2] It is playing an increasingly important role in areas such as Marine resource exploration and scientific research.

1.2. The Development History of AUV Intelligent Decision-Making Systems

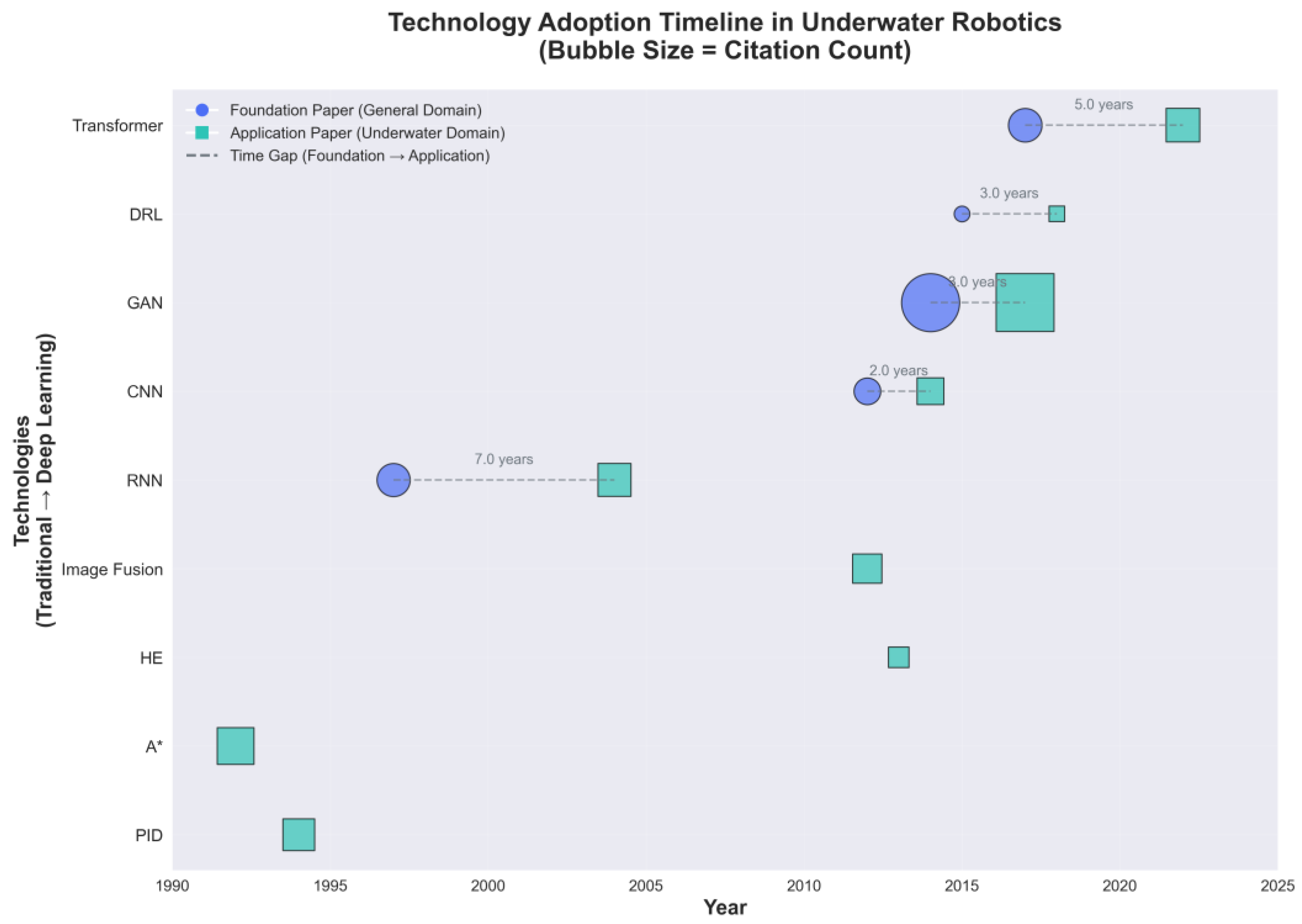

Figure 1 shows the gradual yet impactful integration of deep learning into underwater robotics, typically requiring 2-7 years for technologies to transition from foundational computer science breakthroughs to specialized marine applications.

The underwater environment has many unique physical characteristics that pose a serious challenge to traditional control methods based on precise physical models and explicit rules [

4,

5]. In terms of light, there is severe light attenuation in the underwater environment, where light is rapidly absorbed and scattered as it propagates in water, resulting in severe degradation of visual information. This makes it difficult for vision-dependent underwater robots to obtain clear images and accurate visual information underwater, and they cannot use vision for precise target recognition and navigation as they do on land.

Acoustically, underwater acoustic multipath effects cause distortion of sonar data. When sound waves travel through water, they encounter various obstacles and interfaces, resulting in multiple reflections and refractions, causing the received sonar signal to contain information from multiple paths and thus generating multipath interference. This interference makes the sonar image blurry, making it difficult to accurately identify the position and shape of the target, which seriously affects the target detection and positioning capabilities based on sonar.

In addition, the strong uncertainty brought by strong ocean currents and unstructured seabed topography is also a major challenge for traditional control methods. Strong ocean currents can have a huge impact on the movement of underwater robots, altering their intended trajectories and postures, and traditional control methods often struggle to compensate for such external disturbances in real time and effectively. The complexity of unstructured seabed topography, such as mountains, canyons, reefs, etc., poses great challenges for underwater robots in path planning and obstacle avoidance, and traditional path planning algorithms based on static environment assumptions are difficult to adapt to this dynamic and complex terrain.

In recent years, artificial intelligence technologies represented by deep learning (DL) have revolutionized the decision-making system of underwater robots with their outstanding ability to handle high-dimensional, nonlinear data, and have become the key technology to break through the constraints of the underwater environment and achieve the true intelligence of AUV [

6]. DL algorithms can automatically extract effective features from complex sensor data, avoiding the cumbersome manual feature extraction process in traditional methods and greatly improving the efficiency and accuracy of data processing.

In underwater image and video processing, DL techniques can enhance, de-scatter and denoising underwater images through models such as convolutional neural networks (CNN), effectively overcoming the effects of light attenuation and scattering on visual information, thereby improving image quality and recognizability[

7]. In terms of sonar data processing, DL algorithms can analyze and interpret complex sonar signals, accurately identify target objects, and improve the resolution of sonar images and the accuracy of target recognition.

The application of DL technology has facilitated the leap of underwater robot decision-making systems from static, model-based control logic to dynamic, data-driven autonomous learning paradigms, greatly enhancing the intelligence level of underwater robots. Through DL algorithms, underwater robots can autonomously learn and adjust behavioral strategies based on real-time perceived environmental information, achieving more flexible and efficient task execution [

8].

In terms of path planning, deep reinforcement learning (DRL) algorithms enable underwater robots to learn by trial and error through continuous interaction with the environment, autonomously generating optimal paths and behavioral strategies based on different environmental conditions and task requirements, thereby better adapting to complex and changeable underwater environments such as dynamic obstacles and complex ocean currents. In terms of target recognition and classification, deep learning models can identify and classify various underwater targets with high precision, providing accurate information support for the mission decision-making of underwater robots.

1.3. Current Status

Currently, DL is being widely applied in various modules of underwater robot decision-making systems [

9]. In the information processing module, DL techniques are used for end-to-end underwater image enhancement, de-scattering and sonar image denoising. By training DL models, noise and interference in underwater images and sound signals can be effectively removed, improving the quality and availability of data. In the information understanding module, CNNs are widely used for high-precision identification of underwater targets and geomorphic semantic segmentation. By leveraging CNN’s powerful feature extraction capabilities, key features can be extracted from underwater images and data to achieve accurate identification of underwater targets and scene classification.

In the information analysis module, the DRL breaks the static limitations of traditional geometric programming, enabling the AUV to autonomously generate optimal paths and behavioral strategies adapted to the dynamic environment through interactive learning with the environment. In some complex underwater environments, AUV can use DRL algorithms to dynamically adjust their paths and behaviors based on real-time perceived environmental information, achieving efficient obstacle avoidance and task execution.

1.4. Existing Problems

Although some progress has been made in the application of DL to decision-making systems for underwater robots, there are still some shortcomings in the current research. In terms of comprehensive analysis, the current review articles of the same type [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] lack a comprehensive and integrated analysis of the AUV control system, either not focusing on the particular robot form of AUV [

12], or only introducing a single field separately, lacking an in-depth analysis of the AUV decision-making system as a whole [

10,

11]. It is difficult to meet the needs of scholars who need to build and improve AUV control systems.

On the other hand, the development of DL has had a profound impact on intelligent decision-making systems for underwater robots. This makes the review of control systems based on traditional model analysis no longer suitable for the current stage of development. Due to the particularity of underwater robots, their DL applications have always lagged behind those of onshore quadruped/biped robots, and their intelligent decision-making system architectures are often limited to improvements and fine-tuning of onshore solutions [

14]. This pattern of development is not adapted to the special dynamics and decision-making environment of underwater robots. As larger onshore models [

15] gradually become less suitable for the computing power conditions underwater where it is difficult to deploy large models in real time through communication, it is foreseeable that in the future there will be efficient architectures and standalone systems focused on underwater autonomous control systems. There is a lack of articles in the academic community that analyze and predict the nascent stage of developing autonomous control systems for underwater robots.

In terms of module relationship sorting, with the development of the multi-module consolidation wave led by end-to-end large models, how to sort out the relationships of different modules according to application requirements and thereby achieve better configuration and integration of the perception end and control end of the autonomous system has become an urgent problem to be solved. However, there is currently a lack of comprehensive analysis and sorting of different modules and their complex relationships within the profession, leaving researchers lacking effective references when designing and optimizing AUV decision-making systems.

In the study of DL architectures adapted to underwater environments, simply transplanting the DL framework of ground robots is not sufficient to solve the problem of autonomous decision-making of AUV, and there are relatively few studies of DL architectures tailored to the characteristics of underwater environments at present. There is a particular lack of articles focusing on the impact of DL on autonomous decision-making systems (ADS).

1.5. The Purpose of this Article

This paper aims to address the deficiencies and systematically sort out the role and impact of DL in the AUV intelligent decision-making system in the order of four modules, construct a scientifically classified “four-scenario” deconstruction analysis framework, and deeply explore the specific application and technology selection of DL in each link of the AUV decision-making chain. To provide a comprehensive, detailed and forward-looking analytical perspective for researchers in the intersection of underwater robotics and artificial intelligence.

1.6. Paper Structure Arrangement

This paper is divided into five sections, each of which closely revolves around the theme of DL empowering decision-making systems for underwater robots. The first section is the introduction, which elaborates on the research background, significance, existing problems and the purpose of this study.

Section 2 will define and explain the deconstruction and analysis framework of the “four modules” of the AUV intelligent decision-making system, respectively showing the division of labor in the information processing, information understanding, information judgment and output modules, laying a theoretical foundation for the subsequent in-depth exploration of the application of DL in each module.

Section 3, as an overview of core technologies, reviews the technological evolution and role of DL in the four modules one by one, analyzes the integration trends of different modules, elaborates in detail how DL technology plays a key role in each module, and the integration development trends among different modules.

Section 4 will divide the application environment into four typical scenarios based on task complexity and environmental uncertainty, and analyze one by one the challenges each scenario poses to the intelligent decision-making system and the contribution of DL algorithms in addressing these challenges. Through the analysis of actual scenarios, the advantages and adaptability of DL in different application scenarios will be further revealed.

Section 5 summarizes the core challenges and cutting-edge trends in the current field and looks forward to future developments, comprehensively sorting out the problems and future development directions in the field of DL-enabled decision-making systems for underwater robots at present.

2. Definition and Module Division of Intelligent Decision-Making Systems

2.1. Intelligent Decision Systems: Definitions, Paradigms, and Autonomous Cores

The Intelligent Decision System is the core of achieving a high degree of autonomy in AUV and is recognized as the brain of AUV. The essence lies in the system’s ability to integrate real-time perceptual data to autonomously analyze environmental conditions, assess mission risks, and select and generate optimal action strategies in highly complex, dynamic, and information-constrained underwater environments, in order to efficiently and robustly complete scheduled or emergent tasks.

In general, before the rise of the deep learning wave, the decision-making systems of AUV were mainly based on the rule-driven paradigm, which relied on precise models, preset expert systems, and classical control theory[

16]. The flaw of this approach lies in its inherent vulnerability: once the environmental model changes significantly or the task scenario goes beyond the preset range, the system performance will deteriorate sharply [

17].

The introduction of DL marks a fundamental paradigm shift in IDS, that is, a leap towards data-driven autonomous learning systems. DL models can automatically extract deep features from high-dimensional, nonlinear, high-noise sensor data and establish complex perception-decision mapping relationships [

18], and can make decisions autonomously. This shift enables AUV to break away from over-reliance on precise physical models and to have the ability to perform autonomous cognition and strategy adaptation in unstructured, partially observable real Marine environments.

2.2. The Four-Module Deconstruction and Deep Learning Function of the Intelligent Decision-Making System

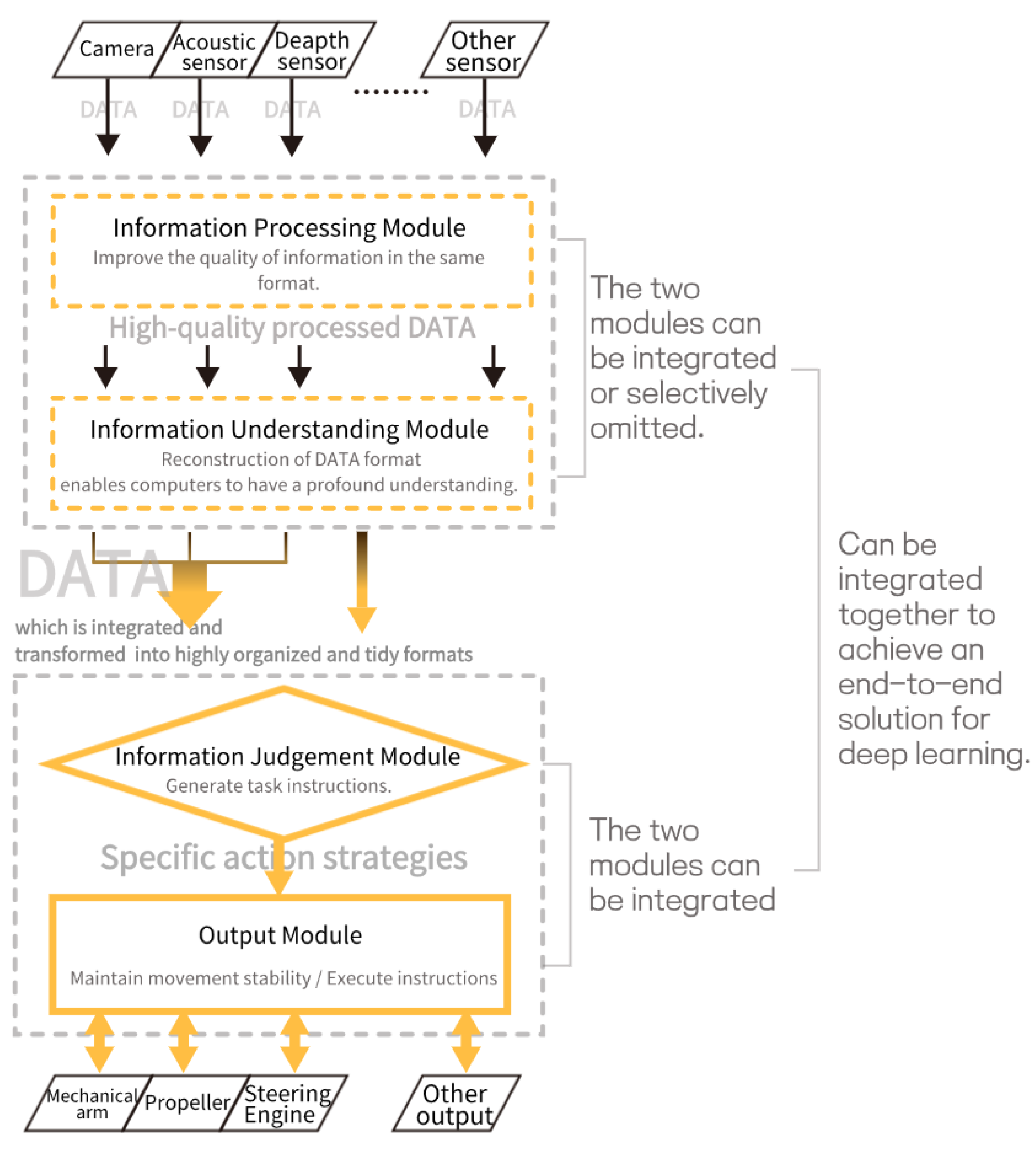

To precisely sort out the impact of deep learning technology on the autonomous decision-making process of AUV, as

Figure 2 shows, this paper uses the logic of information flow to innovatively deconstruct the intelligent decision-making system into four core modules: the information processing module, the information understanding module, the information analys module, and the output module. This division aims to establish a clear analytical framework that enables us to closely track the specific functions and contributions of deep learning technology in each link of the information transformation chain.

2.2.1. Information Processing Module

This module is the starting point of the information flow, and its core function is to receive the raw data flow from various sensors of the AUV, and use advanced algorithms to preprocess and optimize it to purify and enhance the information. For example, underwater image processing, sonar signal denoising, etc. fall within the scope of this module. It optimizes the inforation through technical means. This is different from the information understanding module, which improves the quality of information in the same format and essentially purifies and optimizes the same kind of information.

2.2.2. The Information Understanding Module

Building on the high-quality data provided by the information processing module, the Information Understanding Module is responsible for converting low-level sensor data into high-level environmental cognition that computers can understand, such as semantic segmentation, SLAM mapping, etc. Its function lies in the understanding and transformation of information, that is, using deep learning to transform and understand processed data into high-level semantic information, to extract a small amount of easily understandable single-dimensional simple information from the complex multi-dimensional information that is difficult for the judgment module to understand. It is essentially a reconfiguration of the information format.

2.2.3. Information Judgment Module

The information judgment module is the core hub of the entire Intrusion Detection System (IDS), responsible for translating the environmental cognition and task objectives provided by the Information understanding module into specific action strategies. This module is an embodiment of AUV autonomy and must have the ability to generate optimal decisions in complex and uncertain environments.

In order to better cover intelligent decision-making systems, the information analysis module in this paper is defined as generating simple tasks from information without being responsible for directly converting the tasks into motor pulse signals or rotation angles. After the task instructions are produced by the information analysis module, the output module is responsible for the specific implementation of the lower computer.

2.2.4. Output Module

As mentioned above, the output module is equivalent to the reflex center of the AUV, mainly handling real-time micro-decisions at the tactical, kinematic or dynamic levels. Its core function is to maintain stability while ensuring that instructions from the advanced planning layer can be safely, smoothly and efficiently converted into execution actions. Deep learning is mainly used at this layer to model the real world for predictive adjustment of actions, such as using deep learning for efficient obstacle avoidance strategies and adaptive motion control to make up for the shortcomings of traditional geometric programming algorithms in dynamic environments.

In many articles, the output module and the judgment module are mixed and defined as decision modules, and the concepts of monolithic models and split models are generated based on the degree of fusion [

19]. In decision systems, whether to integrate the output module and the information judgment module together is a very different technical approach. This article will also delve deeper into this issue later on.

Many review articles thus analyze the output module and the information analysis module as a whole. This does not provide a comprehensive review of the components of an intelligent decision-making system. Because there are many architectural designs that handle the design of two separate modules in a specialized hierarchical architectural design model. For example, Article [

20] has a clear hierarchical structure: the AI agent is responsible for cognition and planning, and the underlying controller is responsible for execution. Combining the two modules for analysis can lead to ambiguous semantics and an inability to clearly define trends, and related scholars tend to overlook the architecture scheme of separating control when designing the architecture. So although there are some overlaps in the examples, this article specifically summarizes the two separately.

2.3. The flexibility of Deconstructing Intelligent Decision-Making Systems

Although this paper presents a four-module analytical framework covering information processing, information understanding, information judgment, and output, it must be made clear that the framework aims to provide a theoretical path for information transformation rather than strictly limiting the engineering implementation of all intelligent decision-making systems. In fact, it is the incorporation of deep learning technology that has greatly facilitated the integration of different modules. Because deep learning has a natural end-to-end tendency, many cutting-edge intelligent decision-making systems, especially those that pursue end-to-end learning, will naturally exhibit selective omitting or deep integration of modules. For example, due to the limited computing power of AUV hardware or the pursuit of real-time decision-making, there are often systems that skip the information processing stage and directly feed the raw sensor data without denoising or enhancement into the subsequent information understanding or judgment module . The advantage of this approach is that it avoids the delay caused by preprocessing, but at the cost of significantly increasing the robustness and generalization difficulty of subsequent modules in dealing with high-noise, low-signal-to-noise ratio data.

More aggressive fusion trends are seen in single-layer decision models represented by Vision-Language-Action (VLA) large models. These models are designed to establish a direct mapping from complex sensor inputs to action outputs [

21]. In this architecture, the information processing module and the information understanding module are often embedded or implicitly integrated into a single, giant feature extraction layer of the model, thereby eliminating explicit module boundaries at the system architecture level. For example, Transformer-based VLA[

22] models can directly receive the raw image and output path points or control thrust, bypassing traditional semantic middleware. While this design retains the maximum richness of input information, it also significantly increases the learning difficulty and the amount of data required for the information judgment module.

Although fusion schemes seem to be the current trend, this paper still analyzes them separately according to the four-module theory. Because end-to-end solutions have not yet become a consensus in the industry due to their shortcomings [

23], at the same time, there are still many improvements in deep learning solutions for specific modules being proposed. Separate research will make the technical route clearer and also provide more professional insights and summaries for readers who need to design AUV intelligent decision-making systems. This paper summarizes the greatest innovation points of the multi-module deeply integrated technical solutions in the academic field, and then references and analyzes them in a targeted manner based on the modules where the greatest innovation points are located.

It is also worth noting that, regardless of how the system structure is simplified or integrated, an intelligent decision-making system must contain two core and indispensable modules: the information analysis module and the output module. Without the information analysis module, the system will lose its ability to make autonomous decisions. Without an output module, decision-making strategies cannot be translated into practical actions, and ADS loses its engineering value and task-driven significance. Of course, there are many cases of integration between the output module and the information analysis module, but its presence in the overall intelligent decision-making system makes it impossible for either to be omitted.

2.4. Module Collaboration and System Integration

The four modules of an intelligent decision-making system do not work in isolation but form a complete cognitive decision-making loop through close collaboration. The information flows through the modules in an orderly manner, forming a complete chain from perception to action.

In a typical workflow, the information processing module cleans and enhances the raw sensor data to provide high-quality input for the understanding module. The understanding module semantically parses the processed data to generate a highly clean environment description. The judgment module formulates decision-making strategies based on the environment description and task requirements. The output module eventually converts the strategy into control instructions to drive the actuator to perform the corresponding actions. The execution results of each module form a closed loop through sensor feedback, enabling continuous optimization of the system.

Module interface design and data specification affect system performance. For example, the information understanding module needs to provide an environment description with an appropriate level of abstraction for the information judgment module. Excessive detail increases the computational burden, while excessive simplicity results in the loss of decision-making information. To address this, Li et al. [

24] explored the temporal semantic communication paradigm. They integrated the ISC3 (Integrated Sensing, Computing, Communication, and Control) architecture, using SFE (Semantic Feature Extractor) at the transmitting end to identify the temporal series correlation of control information to adjust the information update strategy, and using SFR (Semantic Feature Reconstructor) at the receiving end to predict and reconstruct untransmitted control information, ensuring control accuracy while reducing communication overhead. It provides a new approach to solving the communication efficiency problem of real-time control systems.

The performance of intelligent decision-making systems is ultimately reflected in their ability to complete complex tasks. A well-designed system should be able to achieve optimal task performance under resource constraints, which requires collaborative optimization of modules and a well-designed overall architect.

3. Modules for Autonomous Decision-Making Empowered by Deep Learning

3.1. Information Processing Module

3.1.1. The Development and Evolution of Technical Solutions

AUV collect information in a wide range of forms. Among the different types of information collected, optical and acoustic information, which are the most commonly used, are often distorted underwater. As a result, the information processing module of the AUV focuses more on these two types of information restoration. As the perceptual front end of the decision-making system, the evolution of the information processing module clearly reflects the shift from relying on prior physical assumptions to embracing data-driven learning.

Before the advent of deep learning, the field was dominated by schemes based on physical models and traditional filtering. For example, the recovery of underwater visual information has long relied on the reverse solution of the physical process of light propagation in water, such as the classic Jaffe-McGlamery[

25] model. These methods attempt to restore images by modeling effects such as forward scattering, backscattering, and absorption, but their performance is highly dependent on precise estimates of the optical parameters of the water body, which leads to limited generalization ability of the models [

26]. Parallel to this are signal processing-based enhancement techniques such as contrast stretching [

27], Retinex theory [

28], and Wiener filtering for acoustic signals [

29]. These methods have low computational overhead and do not rely on complex physical models, but by nature they adjust based on the statistical characteristics of the image, often amplifying noise or losing details, and are difficult to cope with non-uniform complex degradation.

With the increase in computing power and the emergence of large datasets, deep learning-based processing solutions have become mainstream [

30]. CNNs, with their powerful feature extraction capabilities, were first used to construct mappings from degraded images to clear ones. As Wang et al. [

31] first introduced CNN into the field of underwater image enhancement and proposed UIE-Net, the core of which is the co-optimization of color correction and defogging through dual-task joint training. The network consists of a shared feature extraction layer S-Net and two branches. The CC-Net outputs a three-channel attenuation coefficient to correct color distortion, and the defogging network HR-Net outputs a single-channel transmission image to enhance contrast. At the same time, pixel scrambling strategies are used to suppress local texture interference. They randomly shuffle the pixels of the image blocks to improve convergence speed and accuracy. However, there is a problem of color oversaturation in some high-frequency regions, and the reliance on image block overlap tests results in high computational overhead.

Subsequently, the introduction of Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) improved the efficiency of information processing. WaterGAN, as introduced by Li et al. [

32], generates networks through unsupervised adversarial training to generate paired training data, alleviating the scarcity problem of underwater datasets. Since then, applications of unpaired image models such as CycleGAN[

33] have enabled model training without the need for strictly corresponding pairs of clear-degenerate image pairs, lowering the threshold for data acquisition. To address the problem that traditional deep learning methods require a large amount of paired data for underwater image enhancement, UW-CycleGAN [

34] introduced the CycleGAN framework to solve this challenge. It enables the model to perform image-to-image transformation learning between unpaired degradation and clear image sets by training two generators and two discriminators, using cyclic consistency loss to ensure reversibility of image transformation and content retention, achieving high-quality underwater image enhancement without explicitly pairing data and expanding the application boundaries of deep learning in underwater image processing.

The same technical approach has also been successfully applied to the problem of sonar image processing. Du et al [

35] showed that even a four-layer CNN network outperforms traditional techniques in sonar information augmentation. Wang et al. [

36] delved into and compared the application effects of multiple deep learning denoising algorithms designed for optical images on underwater sonar images. Notably, they treated images processed by different denoising algorithms as multi-frame data of the same scene and fused them using multi-frame denoising techniques, achieving good results.

While deep learning has achieved impressive results in denoising and information augmentation, there are also different voices. For example, Huang et al. [

37] clearly pointed out the limitations of deep learning-based denoising algorithms in AUV applications when exploring speckle noise denoising in underwater sonar images. They noted that although deep learning methods typically outperform traditional methods in terms of denoising performance, their huge computational load, long training time, and strict requirements for large-scale raw image datasets make it difficult to deploy efficiently under the limited computing resources and storage space of AUV. This is indeed a huge constraint on the application of deep learning in current modules.

3.1.2. Applications of Deep Learning in Information Processing

Comparing deep learning-based schemes with traditional ones, the differences are reflected in the fundamental differences between data-driven and model-driven [

38]. The traditional approach attempts to solve a well-defined inverse problem through precise mathematical modeling and the inversion of physical laws. The advantage of this approach lies in its solid theoretical foundation and strong interpretability, but its effectiveness is greatly compromised when there is a huge gap between the model assumptions and the complex reality. Deep learning solutions bypass the complex intermediate modeling process and view information processing as a high-dimensional pattern recognition and mapping problem. By learning from massive amounts of data, it summarizes the empirical rules of how to recover from degraded patterns to clear patterns. This data-driven paradigm gives the system unprecedented generalization ability and robustness, enabling it to adaptively handle previously unseen, complex degradation scenarios [

35].

Of course, the acquisition of this capability comes at a cost: the large amount of computation required by deep learning schemes does not meet the inherent requirements of AUV information processing models for speed and low consumption, and its black box nature makes the decision-making process lack transparency, a problem that current research is striving to solve.

3.1.3. Development Summary and Future Projections

The core objective of the information understanding module: to maximize the fidelity and information content of the signal in an underwater environment with highly uncertain information.

Looking ahead, the development of this module will present three major trends. One of them is the multimodal generative sensing. Future systems will no longer be limited to information enhancement of a single sensor, but will be based on generative AI fusing multi-source heterogeneous data such as vision and acoustics [

39]. It can not only restore signals, but also infer and predict missing information based on context to construct locally coherent information input [

40]. The second is the deep integration of physical knowledge and data-driven approaches. For example, the extensive application of physical information neural networks (PINN) in dynamic modeling, as mentioned in article [

41], shows great potential. PINN embeds the physical model of optical or acoustic propagation as an inductive bias into the neural network structure or loss function, avoiding the results that are against common sense due to pure data-driven, thereby enhancing the model stability and interpretability of the algorithm. Thirdly, given the scarcity of underwater labeled data, self-supervised and weakly supervised learning will be the key technology, and the model will acquire powerful feature representations by learning the intrinsic structure of the data itself.

Table 1.

The relevant technologies of the information processing module section1.

Table 1.

The relevant technologies of the information processing module section1.

| Traditiona/DL |

Name |

Technology |

Summary of the technical route |

| Solution based on physical models and traditional filtering |

Jaffe-McGlamery Model [31] |

Physics-based model for underwater vision recovery |

Recovers images by inversely solving the physical process of light propagation in water, modeling forward scattering, backscattering, and absorption effects. |

| Contrast Stretching [33] |

Signal processing enhancement technique |

Enhances image contrast based on statistical properties, with low computational cost and no reliance on complex physical models. |

| Retinex Theory [34] |

Signal processing enhancement technique |

Enhances image quality based on statistical properties, with low computational cost and no reliance on complex physical models. |

| Wiener Filtering [35] |

Signal processing enhancement technique (for acoustic signals) |

Denoises acoustic signals based on statistical properties, with low computational cost and no reliance on complex physical models. |

| Deep learning solution |

UIE-Net [37] |

CNN for underwater image enhancement |

Achieves synergistic optimization of color correction and defogging through dual-task joint training, marking an early application of CNNs in this field. |

| WaterGAN [38] |

GAN for underwater image processing |

Generates paired training data through unsupervised adversarial training, effectively addressing the scarcity of underwater datasets. |

| CycleGAN [39] |

Non-paired image model |

Lowers data acquisition barriers by enabling model training without strictly corresponding paired clear-degraded image sets. |

| UW-CycleGAN [40] |

CycleGAN framework for underwater image enhancement |

Enables high-quality underwater image enhancement without explicit paired data by learning image-to-image translation between unpaired degraded and clear image sets, using cyclic consistency loss. |

| Multi-frame denoising technique with OPD[42] |

Multi-frame denoising for underwater sonar images |

Fuses multi-frame data, treated as images processed by different denoising algorithms, to achieve better denoising results in underwater sonar imaging. |

| PINN (Physics-Informed Neural Networks)[47] |

Neural network with embedded physical models |

Embeds physical models (e.g., optical or acoustic propagation) as inductive biases into neural network structures or loss functions, enhancing model stability and interpretability by preventing physically unrealistic outcomes. |

3.2. Information Understanding Module

3.2.1. The Evolution of Technical Solutions

The role of the information understanding module can be summed up in two applications: first is transformation, that is, converting information into a form understood by the computer through semantic analysis or ranging, etc. The second is integration extraction, which involves analyzing and organizing information from multiple sensors and extracting it as state estimation or pose inference. The role of both applications is to perform information entropy reduction, thereby obtaining highly refined information forms to provide information for subsequent modules. The information understanding module is at the core of AUV’s cognitive ability.

The original technical solution relied heavily on human experts’ insights into specific problems. Researchers need to manually design feature extractors for specific tasks, such as using descriptors like SIFT (Scale-Invariant Feature Transform) and HOG (Histogram of Oriented Gradients) to capture local gradients or texture information of images [

42], and then input these low-dimensional feature vectors into classifiers like SVM (Support Vector Machine) or Adaptive Boosting for discrimination. The essence of this approach is to reduce the dimension of a complex perceptual problem to a linearly separable or approximately separable mathematical problem through feature engineering. It works in structured scenes where the target features are clear and the background is simple, but feature design is time-consuming, laborious and not universal, highly sensitive to changes in lighting, perspective, occlusion, and almost unable to capture the abstract semantic concept of the target.

Deep learning, especially deep convolutional neural networks, can automatically learn feature representations from the original pixels [

43].

In underwater classification tasks, models focus on identifying specific species or targets. For example, MLR-VGGNet[

44] based on the CNN architecture and improved methods based on mResNet [

45] both achieved superior classification accuracy of over 96% on the Fish4Knowledge dataset, DAMNet[

46] and MCANet[

47] used advanced attention mechanisms to handle complex biological image classification and achieved good results.

In the field of underwater object detection and segmentation, detection and segmentation frameworks in various deep learning domains are widely applied, ranging from two-stage methods such as Faster R-CNN to single-stage methods such as YOLO [

48]. It is notable that the YOLO algorithm has taken the mainstream position in underwater object monitoring due to its simplicity, openness and ease of deployment. A wealth of improved algorithms based on YOLO has emerged in the field [

49,

50,

51]. The industry has developed more sophisticated architectures for small targets such as underwater garbage, such as FocusDet[

52] which focuses on small object monitoring and MLDet[

53] which focuses on underwater garbage monitoring.

In terms of semantic segmentation: Models have evolved from classic fully convolutional networks FCN [

54] to more complex Encoder-Decoder architectures such as MTHI-Net[

55] and BCMNet[

56]. A notable frontier trend is the use of the underlying models that many scholars are using to solve the problem of underwater fine segmentation, that is, to make underwater specific improvements starting from onshore algorithms. For example, Meta’s Segment Anything Model (SAM) [

57] has given rise to underwater specialized variants such as Dual-SAM [

58].

Deep learning has also revolutionized underwater SLAM and 3D reconstruction techniques. Traditional visual SLAM relies heavily on geometric features such as corners in the environment and is prone to failure in underwater weakly textured scenes [

59]. Traditional hand-designed features perform poorly when underwater image quality deteriorates, while deep learning can learn feature descriptions that are more invariant to lighting and blurring, significantly improving the accuracy and robustness of feature matching. Advanced features that are more robust to light and blur, such as those learned by SuperPoint [

60], have directly led to more robust visual odometry and pose estimation networks, such as DeepVO and PoseNet. Furthermore, at the back end of SLAM, deep learning has also brought breakthroughs to loopback detection, a key step in eliminating cumulative errors. For example, RCNN[

61] borrowed the idea of probabilistic appearance recognition to determine whether the AUV had returned to the previously passed area and achieved good results.

Further, deep learning has driven the development of multimodal sensor fusion and semantic SLAM. For example, S2L-SLAM[

62] converts sonar data into LiDAR point clouds through deep learning models, enabling existing LiDAR SLAM algorithms to continue to work accurately in complex environments where traditional sensors fail, achieving dynamic selection and fusion of sensor modalities. And the Sonar-CAD for Underwater Semantic 3D Mapping method proposed by Guerneve et al. [

63] not only effectively fuses visual and SONAR heterogeneous data, but also gives high-level semantic information to the map through semantic segmentation and target recognition techniques. This makes the final output of the information understanding module no longer a simple geometric point cloud, but a understood three-dimensional environment model, providing an unprecedented advanced cognitive input for the subsequent information judgment module.

3.2.2. Applications of Deep Learning in Information Understanding

Table 2.

Technologies related to the information understanding module section.

Table 2.

Technologies related to the information understanding module section.

| Traditiona/DL |

Name |

Technology |

Summary of the technical route |

| Traditional Solution |

SIFT, HOG [10] |

Hand-designed feature extractor |

Extracts simple, predefined features for basic environmental understanding. |

| Traditional Visual SLAM |

Geometric feature-based SLAM |

Relies on geometric features like corners, prone to failure in weak-texture scenes. |

| Deep Learning Solution |

MLR-VGGNet [50] |

CNN architecture |

Combining the VGGNet backbone with multi-layer residual, asymmetric and depthwise separable convolutions to optimize fish classification and reduce model parameters. |

| The method based on mResNet[51] |

CNN architecture |

Underwater target recognition method based on mResNet and optimized feature engineering. |

| DAMNet [52] |

CNN with attention mechanism |

Utilizes advanced attention mechanisms for complex biological image classification. |

| MCANet [53] |

CNN with attention mechanism |

Utilizes advanced attention mechanisms for complex biological image classification. |

| Faster R-CNN [54] |

Two-stage deep learning detection framework |

Widely applied for underwater object detection and segmentation. |

| YOLO improved variants [10,55,56] |

Deep learning detection framework |

Mainstream for underwater object monitoring due to simplicity, open-source nature, and ease of deployment. |

| FocusDet [57] |

Fine-grained architecture for small object detection |

Specialized for monitoring small objects like underwater trash. |

| MLDet [58] |

Fine-grained architecture for small object detection |

Specialized for monitoring underwater trash. |

| MTHI-Net [60] |

Encoder-Decoder architecture |

By using multi-task learning to hierarchically segment images, performance is enhanced, demonstrating innovation and potential in the field of image segmentation. |

| BCMNet [61] |

Encoder-Decoder architecture |

Through bidirectional contrastive representation learning, more effective motion representations can be extracted from multimodal data, |

| Dual-SAM [63] |

Specialized foundation model for segmentation |

Underwater-specific variant for fine-grained segmentation base on SAM. |

| SuperPoint [65] |

Feature learning network |

Learns robust high-level features for improved visual odometry and pose estimation. |

| RCNN[66] |

Deep learning for loop closure detection |

Breaks through in loop closure detection by using probabilistic appearance recognition to eliminate cumulative errors in SLAM. |

| S2L-SLAM [67] |

Deep learning model for multimodal sensor fusion |

Converts sonar data to LiDAR point clouds, enabling LiDAR SLAM in challenging environments and dynamic sensor selection. |

| SONAR-CAD for Underwater Semantic 3D Mapping[68] |

Deep learning for multimodal sensor fusion and semantic SLAM |

Fuses visual and sonar data, adding high-level semantic information to maps through segmentation and object recognition. |

Traditional schemes are based on artificially designed features and are essentially based on template or statistical matching. Deep learning schemes build a deep, hierarchical internal representation of the world through data-driven learning, which contains object geometry and texture information, as well as abstract categories and context relationships. As a result, deep learning schemes have a qualitative leap in robustness and generalization, and can handle more complex and variable scenarios. However, its powerful representation learning ability relies on massive labeled data, and the unexplainability of the decision logic limits its application in some areas with high security requirements.

3.2.3. Development Summary and Future Predictions

The core of the information understanding module is the continuous evolution from low-level description of data to high-level understanding of the world.

In the future, the focus of research in this field will be on the following aspects. The first is to build large underwater base models by constructing general underwater scene representation models through large-scale self-supervised pre-training on massive multi-source underwater data. Second, due to the contradiction between the complexity of the underwater environment and the limitations of a single sensor, multi-source fusion is an inevitable path. In the future, information understanding modules will no longer handle isolated data streams, but rather, based on attention architectures such as Transformer, achieve feature-level attention allocation and semantic-level deep fusion of multimodal information such as visual, sonar, and laser point clouds, generating more robust, complete, and information-dense environmental cognition. Ultimately, it provides higher-level cognitive support for the long-term autonomous operation of AUV.

3.3. Information Analysis Module

The fundamental task of the information analysis module is to transform abstract task objectives into specific, safe and efficient sequences of physical actions in highly uncertain, dynamic and information-constrained underwater environments and hand them over to the output module for implementation.

Overall, the decision-making logic of the information analysis module can be roughly deconstructed into two closely coupled but functionally distinct levels: kinematic decision-making and task-driven decision-making.

It is notable that DRL and its derived framework are important directions for the application research of information judgment modules and are expected to endow AUV information judgment modules with cognitive planning capabilities [

64,

65]. Reinforcement learning (RL) involves the core agent interacting with the environment and performing action A in the state for reward R to learn the optimal strategy aimed at maximizing the expected long-term cumulative return [

66]. However, traditional RL methods (such as Q-Learning [

67]) rely on tables to store the value of state-action pairs and encounter the curse of dimensionality when facing the high-dimensional or even continuous state space of AUV sensors, making storage and computation infeasible. The introduction of DL has addressed [

68] this problem. DRL is an organic combination of DL and RL, which uses high-capacity deep neural networks as function approximators [

69] to distill high-dimensional, noisy raw sensor data received by the AUV into low-dimensional, information-intensive, task-relevant feature vectors. Based on this, DRL directly learns end-to-end mappings through the network, either state-to-value mappings (like DQN[

70]) or state-to-action direct mappings which is similar to Policy Gradients in RL [

71].

It is foreseeable that DRL is being deeply integrated into information judgment systems in AUV intelligent decision-making systems [

72,

73].

3.3.1. The Evolution of Kinematic Decision-Making Schemes

Kinematic decisions are the physical basis on which AUV perform all tasks. Before deep learning intervened, this field was dominated by traditional planning algorithms based on precise models.For instance, Article [

74] describes a model that utilized graph search algorithms, including the A* algorithm, for global path planning. It also combined these with the dynamic window approach or the artificial potential field method for local, real-time obstacle avoidance.These schemes are essentially a kind of deductive logic [

75], that is, the optimal motion trajectory is solved through optimized computation given an exact environmental model and dynamic model. In an unstructured real Marine environment, the assumption of model accuracy is broken, and the robustness of the algorithm drops sharply [

76]. At the same time, building a completely real and complex decision-making model requires elaborate mathematical modeling, which further increases the difficulty of making correct decisions.

DRL provides a completely different inductive logic for this. The DRL scheme bypasses the difficulty of precisely modeling the world and instead learns a mapping from perception to action directly from high-dimensional, noisy raw sensor data through massive environmental interaction trial and error [

77]. The goal is to generalize an optimal strategy that maximizes long-term cumulative returns, a strategy functionally similar to a highly optimized driving intuition.

DRL has developed different mainstream algorithms for different action Spaces: Deep Q-networks perform well for discrete actions such as turn left rudder, turn right rudder, go straight [

77]. DCMAC[

78] approximates Q values through neural networks, enabling AUV to judge the long-term value of performing each discrete action from high-dimensional perception. Algorithms based on the Actor-Critic architecture, such as Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient [

79] and Proximal Policy Optimization [

80], are more applicable to continuous action Spaces that are more common in AUV kinematic decision-making, such as precise rudder angles or thruster speeds. They output continuous control instructions directly through an Actor network and evaluate the quality of the instructions through a Critic network [

81], thus efficiently learning smooth and robust motion strategies in complex continuous Spaces.

The transplantation of VLM algorithms in the field of decision-making also shows great value. OceanPlan[

82] pioneered an innovative Large Language Model (LLM) task - motion planning and re-planning framework aimed at addressing the core challenge of efficient and robust navigation of AUV through natural language instructions in vast unknown Marine environments. The core lies in a hierarchical planning system that includes LLM planners, HTN mission planners and DQN motion planners, complemented by a comprehensive re-planner to address the uncertainty of the underwater environment. Likewise, Autonomous Vehicle Maneuvering[

90] integrates cognitive, decision-making, path planning and control functions to achieve real-time environmental adaptive LLM-guided path planning. Yang et al [

83] also reported on a VLM-powered ASV navigation system that enhances success in dynamic marine environments through improved path planning.

This data-driven paradigm essentially shifts reliance on precise models to reliance on massive data. The core advantage lies in its ability to implicitly encode high uncertainty in unstructured environments into policy networks, evolving the kinematic decisions of AUV from static trajectory tracking to dynamic, real-time feedback environmental adaptation [

84].

3.3.2. The Evolution of Task-Driven Decision-Making Schemes

Task decision systems involve the significance of AUV. In traditional schemes, this level is typically handled by expert systems such as finite state machines or behavior trees. For example, HUXLEY [

85] is a typical implementation based on hierarchical expert systems. The system uses a modular control hierarchy and internally organizes task flows through predefined state machines and behavior trees, enabling the AUV to perform reliable behavior switching in accordance with the sequence of rules set by the engineer when it is executed.

The introduction of DRL is historic: its learning paradigm makes it naturally suitable for the complex task-driven decision-making of AUV. It allows AUV to break away from reliance on human expert rules, no longer requiring precise physical models, and instead be able to self-learn how to perform complex tasks directly from interactions with the environment. DRL enables AUV to perform exploratory complex tasks. For example, DRL-guided Autonomous Exploration with Waypoint Navigation[

86] enables AUV to train in completely unknown underwater cave simulation environments, using DRL agents to start from the points of interest perceived by the environment Autonomously plan waypoints and carry out exploration. Without any prior maps, you can eventually complete full coverage exploration in complex three-dimensional cave structures.

At the same time, VLM models are gradually getting involved in the control system to deal with more advanced complex tasks. DREAM[

88] has developed a VLM-driven autonomous underwater monitoring system that integrates multimodal perception, chain-based cognitive planning, and low-level control to enable underwater robots to conduct efficient and comprehensive long-term exploration and target monitoring without human intervention. It builds dedicated maps to provide environmental memory and uses carefully designed prompts to guide the VLM to generate humanoid navigation strategies, demonstrating outstanding efficiency and coverage in both simulation and real-world experiments.

A lot of useful work has also been produced in using VLMS to optimize AUV operations. Word2Wave[

89] enables real-time programming and parameter configuration of AUV tasks through natural language, for example. Its proposed W2W framework includes a novel set of language rules and command structures, a GPt-based prompt engineering module for generating training data, and a sequence-to-sequence learning pipeline based on the T5-Small small language model for generating task commands from human speech or text. And a user interface for 2D task map visualization and human-computer interaction. Thus reducing task programming time and enhancing the user experience, designed for future AUV task programming without manual operation.

In terms of multi-agent decision-making, multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) provides a core framework for collaborative decision-making in multi-AUV clusters, enabling them to autonomously learn task allocation, formation flight, and collaborative confrontation strategies. UW-MARL [

90] uses multi-agent RL to achieve adaptive sampling of AUVs, first exploring the environment through distributed Q-learning, collecting data and calculating variance as rewards to construct the initial environment map; Then, in the second stage, tasks are assigned based on priority index, allowing the vehicle to be finely reconfigured within the MARL framework. Data sharing and collaboration are achieved through a customized communication protocol, and underwater environment monitoring is completed efficiently and economically. Similar HA-MRAL [

91] focuses on the coordination, stability, convergence speed and high winning rate of wireless data sharing, and designs intelligent game strategies for multi-AUV underwater network systems.

3.3.3. Applications of Deep Learning in Information Analysis

The value of DL in the information judgment module lies in providing a completely new solution for the decision-making logic of AUV. Conventional planning algorithms follow deductive logic and rely on precise environmental and dynamic models to find the optimal solution, showing strong vulnerability in the highly uncertain conditions of the underwater unstructured environment. DRL provides inductive logic, circumventing the difficulty of precise modeling, learning end-to-end mapping with massive interactive data, transforming reliance on precise models into reliance on massive data, and facilitating the evolution of AUV decision-making from trajectory tracking to environmental adaptation.

Table 3.

Some related technologies of the information analysis and judgment module.

Table 3.

Some related technologies of the information analysis and judgment module.

| Whether to integrate the two modules |

Traditiona/DL |

Name |

Technology |

Summary of the technical route |

| No |

Traditional |

Huxley [90] |

Hierarchical expert system (state machines, behavior trees) |

Organizes task flows using modular control layers with predefined state machines and behavior trees. |

| A* Path Planning Approach[79] |

Graph search algorithm

DWA

APF |

Used for local real-time obstacle avoidance in traditional approaches. |

| Deep Learning |

DRL-Guided Autonomous Exploration with Waypoint Navigation[91] |

DRL agent |

Autonomously plans waypoints and performs exploration in unknown underwater cave environments without prior maps. |

| Word2Wave[94] |

VLM

SLM |

Real-time programming and parameter configuration for AUV tasks. |

| DREAM[93] |

VLM |

The VLM-driven underwater autonomous monitoring system integrates multimodal perception, cognitive planning based on thought chains, and low-level control |

| RL Adaptive Underwater Arm Control[92] |

Actor-Critic structure with DNNs |

Demonstrates that RL controllers can outperform MPC in fine physical interaction. |

| UW-MARL[95] |

Q-learning

MARL |

MARL with distributed Q-learning for adaptive underwater sampling, coordinating autonomous vehicles via shared Q-values. |

| HA-MARL[96] |

APF

MAPPO |

It enhances multi-AUV data sharing by integrating APF for path planning and a Tabu-Search task scheduler into MAPPO. |

| UnderwaterVLA[28] |

VLM

VLA |

The dual-brain architecture and zero-data training enable robust autonomous navigation of underwater VLA. |

| Yes |

OceanPlan [87] |

LLM planner, HTN task planner, DQN motion planner, replanner |

Addresses efficient and robust AUV navigation in unknown oceans via natural language instructions. |

| Autonomous Vehicle Maneuvering [90] |

LLM-guided path planning |

Achieves real-time environmental adaptive LLM-guided path planning by integrating cognitive, decision-making, path planning, and control functions. |

On this basis, DL unlocks advanced cognitive and interaction tasks that are difficult to complete with traditional solutions. Traditional expert systems are restricted by preset rules and cannot handle unknown situations. DRL gives AUV self-learning capabilities, enabling them to master complex task strategies through autonomous trial and error. In addition, DL provides the core technical support for more advanced decision-making architectures. Breakthroughs in the robustness and stability of multi-agent control make deep interaction with multiple agents possible.

3.3.4. Development Summary and Future Projections

Despite the great potential of DRL and VLM, there are three core challenges on the way to high-reliability applications. One is the issue of sample efficiency. Learning requires massive interaction data, which is costly and risky in underwater environments [

92]. The second is the black box problem, where the strategy decision-making logic is hidden in neural network parameters, and stability and security are difficult to analyze and verify, which is unacceptable in critical tasks. The third issue is deployment failure. Because simulators have difficulty precisely simulating real physics [

92], strategies trained in simulation environments often experience performance degradation or even failure when deployed to physical entities.

In response to these challenges, we believe that the information judgment module will make progress and develop in several areas in the future. First: A strong combination of AUV and VLM. According to Wang et al [

23], existing VLA models are roughly divided into three architecturally: Discrete Token VLAs, Generative Action Head VLAs, and Custom Architecture VLAs. In fact, almost all existing VLAs in the field of underwater robotics are based on Discrete tokens. The Discrete Token VLAs architecture has many limitations [

23]. So we think that the subsequent combination of AUV and VLA is bound to turn to the other two for better adaptability and resolution. The second is the expected wide application of Offline RL and Sim2Real technology in the AUV field. Because AUV are at a disadvantage in terms of sample efficiency and safe trial and error, using massive offline navigation log data for policy learning will become an important training method. Third, future research will focus on setting safe boundaries for its decision-making, quantifying behavioral uncertainty, developing explainable tools to make its black box attributes transparent to some extent.

3.4. Output Module

The output module is responsible for maintaining system stability and performing simple tasks assigned by the judgment module. Advanced control schemes empowered by deep learning do not attempt to completely subvert classical control theory, but rather infuse it with powerful adaptive and learning capabilities through ingenious integration.

3.4.1. Evolution of Technical Solutions

The core objective of classical control theory is to ensure the stability of the system and the precise tracking of the preset trajectory. At the motion control level, the PID controller has been widely used for a long time because of its simplicity and effectiveness [

93]. But with the increasing demands for accuracy and robustness in tasks, modern robust control methods such as SMC[

94] were later introduced to better suppress external disturbances such as ocean currents. At the operational control level, for AUV with robotic arms, traditional methods mainly rely on inverse kinematics to calculate joint trajectories and track them through PID controllers in the joint space [

95]. This approach shows rigidity and vulnerability when in contact with the environment or when facing an uncertain target position, making it difficult to complete fine physical interactions [

95]. It can be concluded that the evolution of the output module is first reflected within traditional control theory, that is, from classical stability to robust trajectory tracking, and from fixed motion to closed-loop adaptive motion with admittance/impedance control introduced. Then comes the introduction of deep learning.

One core direction in dynamic stabilization is using neural networks for model identification and adaptive control. The hydrodynamic model of the AUV is highly nonlinear and time-varying, making it difficult to model precisely. In recent years, dynamic neural networks have been proposed to address the modeling uncertainty and parameter perturbation problems of AUV, such as DNCS[

96] which online learns the unknown dynamics of the system and adjusts the control gain in real time by constructing a parallel identifier structure based on Lyapunv stability. The advantage of this scheme is that it can achieve high-precision trajectory tracking without relying on precise hydrodynamic parameters and has strong robustness against unknown perturbations; However, the computational load is high, and the sensitivity of neural network weight initialization may lead to a decrease in convergence speed, which may be limited in tasks with extremely high real-time requirements. Cortez et al. [

97] embedded fluid mechanics prior knowledge into the network structure to enhance the generalization ability of the model by constrains the evolution law of the state space. This approach significantly reduces training data requirements in low-speed cruise scenarios while maintaining physical consistency of dynamic characteristics; However, it has shortcomings such as insufficient adaptability to high-speed maneuvers or strong turbulence conditions, and the stability of the numerical solution of the differential equation is limited by the step size.

Operationally, the introduction of deep learning enables the output module to be more deeply integrated with the information judgment module. For example, Cimurs et al [

87] presents a DRL controller based on the Actor-Critic architecture, which directly takes joint position, velocity, and target state as inputs and outputs torque instructions for precise position control. A closed-loop operation of the output module and the information analysis module is achieved. However, it is worth noting that it has not been applied in the field and still has a lot of room for development. The LLM model proposed by Kim and Choi [

84] is directly and deeply integrated into an algorithmic program, while integrating PINN’s environmental awareness network module and incorporating flow field data into the state space of the AUV to achieve iterative optimization of the AUV structure and control strategy, thereby significantly improving the adaptability and mission performance of the AUV in complex underwater environments.

3.4.2. Applications of Deep Learning in Information Output

For kinematic stability maintenance tasks, traditional control schemes are rooted in rigorous mathematical derivations. The integration of deep learning, through the powerful nonlinear function approximation ability of neural networks, enables the fusion scheme to identify and compensate for unmodeled dynamics and parameter uncertainties in traditional models online. This will avoid the huge amount of work of designing algorithms manually. It would be almost impossible to design a computational formula that is so well-considered without the involvement of DL. This is, of course, at the expense of some efficiency, which is also the advantage of the traditional control of the output module - manual algorithms still maintain their efficiency advantage within an acceptable margin of error, which is exactly what the computationally scarce underwater robot values.

On the other hand, DL does not have a significant impact on the output module in terms of task implementation. For complex tasks, the difficulty mainly lies in understanding and breaking down the tasks. The simple tasks that are broken down can actually be done very well with the traditional approach. This does not mean that DL is of no value in the output module. In fact, integrating the output module with the information analysis module to form a unified architecture similar to the VLA model has its unique value, but there are also corresponding shortcomings, and how to make trade-offs will be analyzed in detail in the next subsection.

Table 4.

Output module-related technologies.

Table 4.

Output module-related technologies.

| Whether to integrate the two modules |

Traditiona/DL |

Name |

Technology |

Summary of the technical route |

| No |

Traditional |

PID Controller [99] |

PID |

Provides simple and effective stable tracking for predefined paths. |

| SMC [100] |

Sliding Mode Control |

Offers robust control to suppress external disturbances like sea currents. |

| Inverse Kinematics + PID [101] |

Inverse Kinematics, PID |

Calculates and follows joint trajectories for manipulator arms. |

| Deep Learning |

DNCS [102] |

DNN |

Online learning of unknown system dynamics to adaptively adjust control gains for tracking. |

| Domain-aware Control-oriented Neural Models for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles[103] |

Physics-Informed Neural Network |

Embeds hydrodynamic priors into the network to improve generalization. |

| RL Adaptive Underwater Arm Control [92] |

Actor-Critic structure with DNNs |

Demonstrates that RL controllers can outperform traditional MPC for fine physical interaction. |

| Yes |

OceanPlan [87] |

LLM planner, HTN task planner, DQN motion planner, replanner |

Addresses efficient and robust AUV navigation in unknown oceans via natural language instructions. |

| Autonomous Vehicle Maneuvering [90] |

LLM-guided path planning |

Achieves real-time environmental adaptive LLM-guided path planning by integrating cognitive, decision-making, path planning, and control functions. |

3.4.3. Integration and Separation of Output Modules and Information Analysis Modules

It is notable that many of the cases cited in the introduction of the information judgment module are end-to-end solutions that combine the output module with the information judgment module. The RL strategy proposed by Kim and Choi [

84] directly outputs the underlying speed and Angle control instructions. In fact, it takes advantage of the easy fusion feature of DL to integrate the output module with the information judgment module as a whole. There are also many options that handle the information analysis module and the output module separately. For example, Carlucho et al [

98] reported a model which has a clear hierarchy where the RL is responsible for high-level task decision-making and the S-Surface controller is responsible for low-level real-time control. It can be seen that whether the information judgment and output modules are integrated can be used as a criterion to divide two different technical solutions. This is analyzed and explained in

Section 2.4.

DL inherently has an end-to-end tendency [

99]. Based on whether the algorithm can be clearly split into an information analysis end and an output end, current solutions can be roughly divided into two technical paradigms: hierarchical decision architecture and end-to-end decision architecture. A review of these two approaches constitutes the core of understanding the evolution of current intelligent decision-making technologies.

The hierarchical architecture does not fully embrace DL solutions and does not thoroughly reflect the end-to-end technical inclination of DL. It can also clearly decouple complex decision-making problems, allowing different levels of strategy to be designed, trained, and debugged independently. Because of its operational semantic sub-objectives, high-level decisions are highly interpretable, and low-level skills can be reused in different tasks after being learned, with good combinatorial generalization ability. However, the challenges are obvious: the interaction between the lower and higher levels significantly reduces resolution, and when dealing with complex problems, it is less efficient and professional than the end-to-end model.

The theoretical charm of the end-to-end approach lies in the fact that it minimizes the injection of human prior knowledge and avoids the loss and potential suboptimal decomposition problems caused by the transmission of information between modules in a hierarchical architecture. This is precisely the drawback of the hierarchical architecture. In theory, an end-to-end model deep enough and data-rich enough could potentially discover more efficient control strategies beyond human intuition. Its technical implementation relies entirely on DRL, particularly algorithms capable of handling high-dimensional continuous input and output, such as PPO[

100], SAC[

101] and other RL algorithms.

However, the practical challenges of end-to-end learning are huge. The first is the astonishing sample complexity. Due to the lack of guidance and supervision from intermediate targets, agents have to blindly explore in a vast state-action space, resulting in an extremely slow learning process that requires massive amounts of interaction data, which is almost unrealistic in a real underwater environment. Next comes the serious black box problem. The entire decision-making process takes place within an unresolvable neural network, and when the system malfunctions, it is almost impossible to diagnose whether the problem lies in the perception part, the decision-making logic part, or any other link. This unexplainability greatly limits its application in safety-critical tasks. Finally, the strategies learned end-to-end are often highly overfitted to their training environment and tasks. An end-to-end strategy trained for the pipeline tracking task may be completely unable to handle the docking task because it does not learn any transferable, modular knowledge and shows poor task generalization ability.

The choice between the two architectures is often related to the pattern of decision-making.

Applications of AUV kinematic algorithms often adopt an end-to-end approach [

102,

103]. Because its output is relatively straightforward, it is suitable for end-to-end deployment in all aspects. The advantage also lies in the high extraction efficiency that surpasses manual design. For example, an end-to-end AUV navigation strategy might directly learn from the fan-shaped scan of the forward-looking sonar to extract implicit information about the distance, orientation, and movement trend of the obstacle, and map it directly to the thrust difference between the left and right thrusters, thereby achieving reactive obstacle avoidance. But there are also different schemes, such as UnderwaterVLA[

22] which uses a layered motion structure and achieves good results as well.

It is different in the field of task implementation. End-to-end solutions are not gaining an overwhelming advantage nowadays because of their data problems and black box issues. Scholars tend to selectively choose based on the complexity of the target operation.

3.4.4. Development Summaries and Future Projections

The technological evolution of the output module is the physical basis for the development of the AUV from a simple active platform to an intelligent agent capable of precisely and skillfully interacting with the environment. At its core is the shift from passive instruction execution to active task completion.

Looking ahead, we believe the future trend for output modules is to generate AUV-specific end-to-end models. Due to the specificity of the underwater environment, the AUV domain will produce end-to-end models specifically for this purpose. The output module and the information analysis module are deeply integrated and moving towards deep integration.

4. Application Analysis and Technology Selection of AUV Intelligent Decision-Making System Empowered by Deep Learning

The previous section systematically dissects the development of the four major modules in the context of DL. However, the vitality of technology is ultimately reflected in its ability to solve practical problems. Therefore, we will go beyond the limitations of traditional classifications based on application domains ,such as scientific expedition or military defense, as such divisions tend to blur the commonalities of underlying technical requirements. Instead, this paper proposes to systematically deconstruct the application scenarios of AUV with “task complexity” and “environmental uncertainty” as two mutually orthogonal core dimensions. The superiority of this division lies in the fact that it directly relates to two fundamental determinants of the level of intelligence required by the decision-making system: the depth of the internal decision-making logic and the difficulty of external perception adaptation, and can provide more precise theoretical basis and practical insights for technology selection under the four-module architecture.

4.1. Division Criteria: Orthogonal Deconstruction of Task Complexity and Environmental Uncertainty

The first dimension, task complexity, measures the requirements of the task for the AUV’s advanced cognition, long-term planning, and fine physical interaction capabilities. It is divided into two levels.

Simple tasks: These are tasks with a single objective, whose sequences of actions are mostly predefined, and whose interaction logic with the environment is relatively clear.

Complex tasks involve multi-objective collaboration, continuous interaction in dynamic environments, decision chains that require long-duration reasoning, or understanding and decomposing high-level abstract semantic instructions.

The second dimension, environmental uncertainty, measures the pressure exerted by the AUV operating environment on the decision-making system from the perspective of external challenges. Structured environment: refers to scenarios with relatively stable and predictable environmental features and abundant prior information, such as inland lakes, aquaculture cages, ports with clear underwater structures, etc. In these environments, the changes in Marine dynamics such as light and water flow are relatively gentle, and the degradation of perceived information is within a relatively controllable range.