Submitted:

11 November 2025

Posted:

12 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

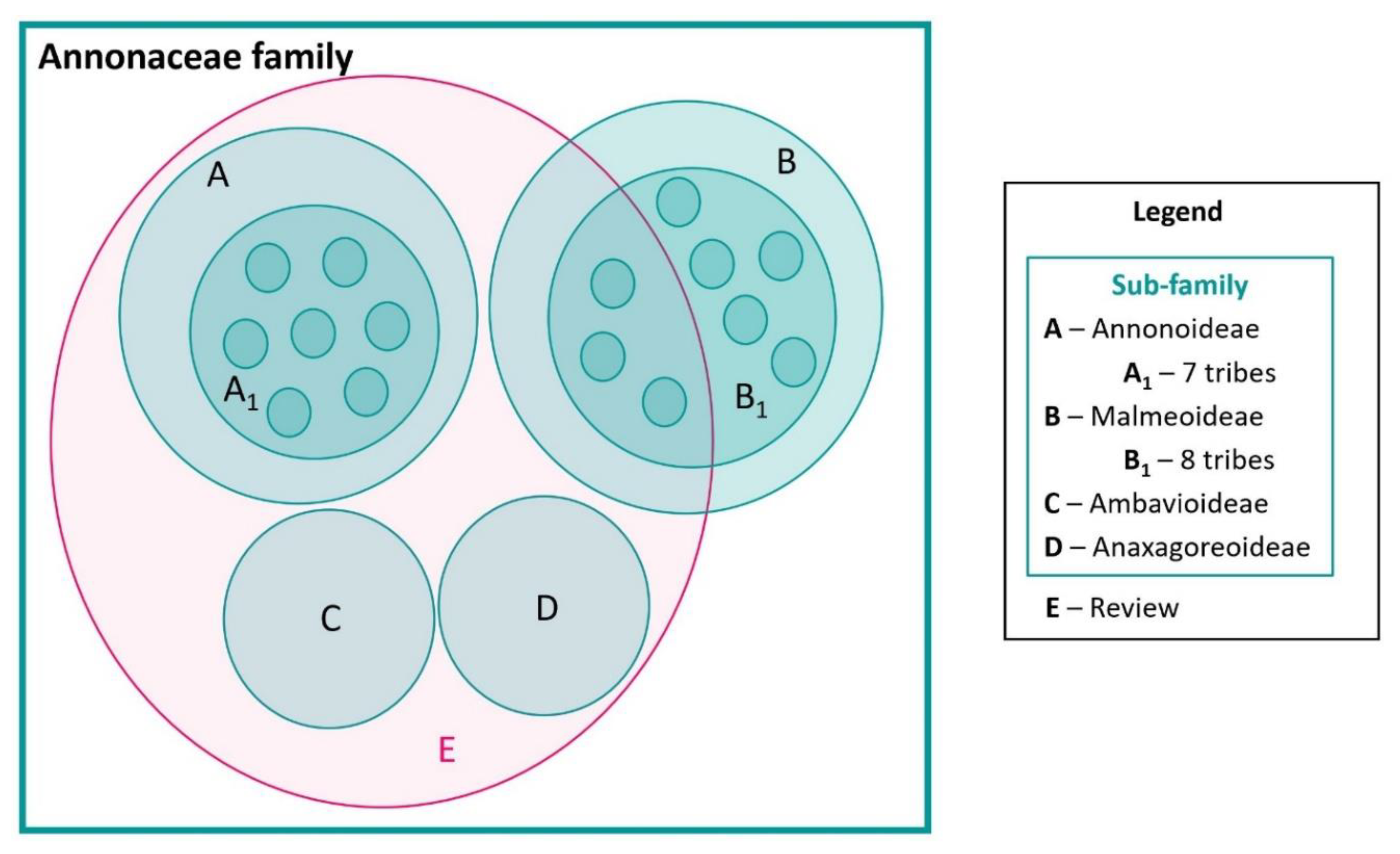

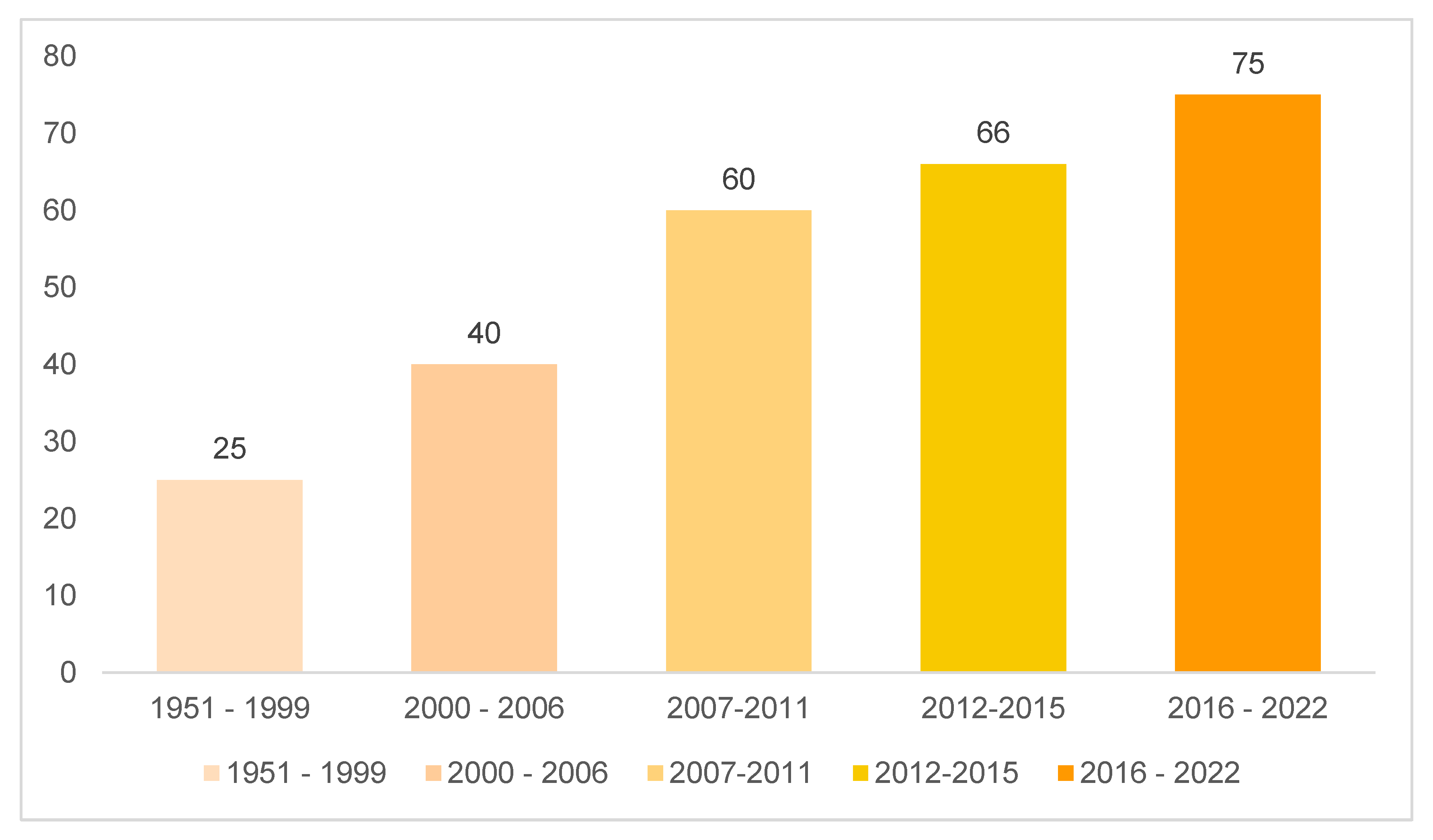

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

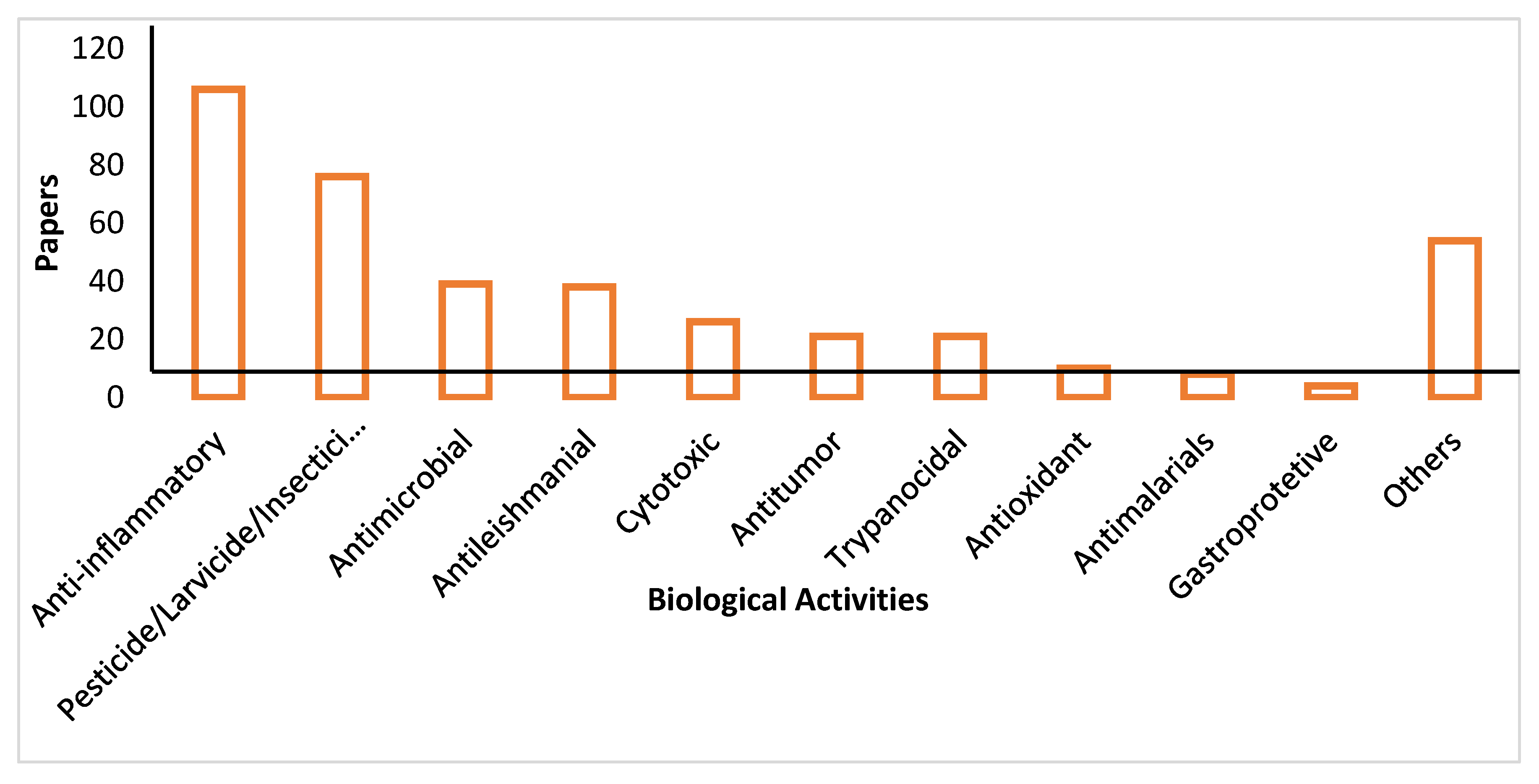

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Anti-Inflammatory

| Annonaceae Species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Methodology | Inhibition | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Annona cacans |

Leaves Pulp Seeds |

Hydromethanolic extract (HME) Ethyl acetate fraction (EAF) |

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity carrageenan-induced paw oedema | After 6 h, 28% (300 mg/kg HME-Leaves) 53% (100 mg/kg HME-Pulp) 58% (300 mg/kg HME-Pulp) 43% (30 mg/kg EAF), 51% (100 mg /kg EAF) |

(Volobuff et al. 2019) |

| Annona crassiflora | Fruit peel Leaves Leaves Leaves Leaves |

Polyphenol-enriched fraction (PEF) Methanolic extract Methanolic extract Methanolic extract Methanolic extract |

Wound closure in C57 mice Carrageenan-induced edema MPO activity Total leukocytes Carrageenan-induced leukocyte migration |

75% (2% PEF topical) 84%(6% PEF topical) 53% (100mg/kg) 47% (300mg/kg) 60% (100mg/kg) 78% (100mg/kg) 90% (300mg/kg) 43% (300mg/kg) |

(de Moura et al. 2019) (Rocha et al. 2016) (Rocha et al. 2016) (Rocha et al. 2016) (Rocha et al. 2016) (Rocha et al. 2016) |

| Annona glabra | Fruits | 7β,16α,17-trihydroxy-ent-kauran-19-oic acid | NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells | IC50= 0.39 ± 0.12 μM | (Nhiem et al. 2015) |

| Fruits | 16β,17-dihydroxy-ent-kauran-19-al | NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells | IC50 = 0.32 ± 0.04 μM | (Nhiem et al. 2015) | |

|

Annona muricata |

Fruits | Lyophilized extract | Xylene-induced ear edema | 34.04% (50μg/mL) 63.83(100μg/mL) 80.85(200μg/mL) |

(Ishola et al. 2014) |

| Annona muricata | Fruits | Lyophilized extract | Cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 activity | 39.44% (100μg/mL) | (Ishola et al. 2014) |

| Fruits | Lyophilized extract | Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 activity | 55.71% (100μg/mL) | (Ishola et al. 2014) | |

|

Annona nutans |

Fruits | Lyophilized extract | Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 activity | 55.71% (100μg/mL) | (Ishola et al. 2014) |

| Annonaceae Species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Methodology | Inhibition | Ref. |

|

Annona Senegalensis |

Seeds | N-cerotoyltryptamine | ROS production in zymosan stimulated human whole blood phagocytes | IC50 = 2.7 ± 0.1 μg/mL | (Tamfu et al. 2021) |

| Seeds | Methanolic extract | ROS production in zymosan stimulated human whole blood phagocytes | IC50 =8.7 ± 10.2 μg/mL | (Tamfu et al. 2021) | |

| Seeds | Acetogenin | NO production in lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated J774.2 mouse macrophages | IC50 = 3.9 ± 0.2 μg/mL | (Tamfu et al. 2021) | |

|

Annona squamosa |

Bark | Caryophyllene oxide | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | After 2 hours 45% (12.5mg/kg) 51% (25mg/kg) |

(Chavan et al. 2011) |

| Bark | Sesquiterpene fraction (copaene (35.40%), patchoulane (13.49%) and 1H-cycloprop(e)azulene (22.77%)) | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | After 2 hours 38% (12.5mg/kg) 34% (25mg/kg) |

(Chavan et al. 2012) | |

| Bark | 18-acetoxy-ent-kaur-16-ene | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | After 2 hours 51.6% (12.5mg/kg) 60.9% (25mg/kg) |

(Chavan et al. 2011) | |

| Annona vepretorum | Leaves | Ethanolic extract | leukocyte migration to the peritoneal cavity |

62%(25 mg/kg), 76% (50 mg/kg) 98% (100 mg/kg) |

(Silva et al. 2015) |

| Leaves | Ethanolic extract | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | After 2 hours 58%(25 mg/kg) 45% (50 mg/kg) 72% (100 mg/kg) |

(Silva et al. 2015) | |

| Annona vepretorum | Leaves | Ethanolic extract | Histamine-induced paw edema | After 1 hour >65% (100mg/kg) |

(Silva et al. 2015) |

| Cyathocalyx pruniferus | Leaves | Spathulenol Cyclopropa-azulene Polycarpol Koetjapic acid 2-Octaprenyl-benzoquinone 14-methylloctadec-1-ene 1-Docosene β-Sitosterol |

PGE2 | 71.4 (IC50 = 25.8) 8.6 (IC50 = -) 70.1 (IC50 = 24.7) 80.4 (IC50 = 13.1) 86.1 (IC50 = 11.2) 3.5 (IC50 = -) 5.8 (IC50 = -) 21.6 (IC50 = -) |

(Attiq et al. 2021) |

| Annonaceae Species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Methodology | Inhibition | Ref. |

| Cyathocalyx pruniferus | Leaves | α-Tocopherol 11-prenol Quercetin Epicatechin Chrysin Indomethacin (Positive control) |

PGE2 | 15.9 (IC50 = -) 2.1 (IC50 = -) 79.8 (IC50 = 15.4) 77.3 (IC50 =17.3) 73.8 (IC50 = 21.8 88.1 (IC50 = 11.8) |

(Attiq et al. 2021) |

| Cyathocalyx pruniferus | Leaves | Spathulenol Cyclopropa-azulene Polycarpol Koetjapic acid 2-Octaprenyl-benzoquinone 14-methylloctadec-1-ene 1-Docosene β-Sitosterol α-Tocopherol 11-prenol |

COX-2 |

21.1 (IC50 = -) 4.6 (IC50 = -) 29.6 (IC50 = -) 85.6 (IC50 = 8.1) 88.1 (IC50 = 6.6) 2.1 (IC50 = -) 2.4 (IC50 = -) 11.1 (IC50 = -) 10.5 (IC50 = -) |

(Attiq et al. 2021) |

| Cyathocalyx pruniferus | Leaves | Quercetin Epicatechin Chrysin Dexamethasone (Positive control) |

COX-2 | 3.3 (IC50 = -) 80.1 (IC50 = 10.3) 74.7 (IC50 =12.5) 70.5 (IC50 =15.7) 92.8 (IC50 = 5.1) |

(Attiq et al. 2021) |

|

Duguetia furfuracea |

stem bark | Essential oil | LPS-induced paw edema | After two hours 41.67% (3mg/kg) 86.11% (10mg/kg) |

(Saldanha et al. 2019) |

| stem bark | Essential oil | LPS-induced paw edema | After four hours 45.45% (1mg/kg) 63.64% (3mg/kg) 92.42% (10mg/kg) |

(Saldanha et al. 2019) | |

| Leaves | Methanolic extract | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | After two hours 39% (300mg/kg) 22% (100mg/kg) 17.5% (30mg/kg) |

(do Santos et al. 2018) | |

| Annonaceae Species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Methodology | Inhibition | Ref. |

| Duguetia furfuracea | Leaves | Methanolic extract | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | After four hours 40% (300mg/kg) 25% (100mg/kg) |

(do Santos et al. 2018) |

| Leaves | Dicentrinone | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | For 100 mg/kg 69.1% (2 hours) 50.4% (4 hours), |

(do Santos et al. 2018) | |

| Leaves | Methanolic extract | Zymosan-induced edema | 38.1% (300mg/kg) | (do Santos et al. 2018) | |

| Leaves | Dicentrinone | Zymosan-induced edema | 27.1% (300mg/kg) | (do Santos et al. 2018) | |

| Leaves | Enriched phenylpropanoid extract | LPS-induced paw edema | After two hours 90.91% (3mg/kg) 92.42% (10mg/kg) |

(Saldanha et al. 2021) | |

| Duguetia furfuracea | Leaves | Enriched phenylpropanoid extract | LPS-induced paw edema | After four hours 77.78% (1mg/kg) 77.78% (3mg/kg) 81.48% (10mg/kg) |

(Saldanha et al. 2021) |

| Leaves | α-asarone | LPS-induced paw edema | After two hours 62.12% (3mg/kg) 69.70% (10mg/kg) 69.70% (30mg/kg) |

(Saldanha et al. 2020) | |

| Leaves | α-asarone | LPS-induced paw edema | After four hours 72.22% (3mg/kg) 81.48% (10mg/kg) 81.48% (30mg/kg) |

(Saldanha et al. 2020) | |

|

Duguetia moricandiana |

Fruits | Discretamine | NO production in LPS-stimulated macrophages | Around 50%. (100 and 200 μg/mL) |

(Lemos et al. 2017) |

| Fruits | Discretamine | IL-6 production in LPS-stimulated macrophages | 74.1% (50μg/mL) 76.6% (100μg/mL) 75.1% (200 μg/mL) |

(Lemos et al. 2017) | |

| Fruits | Discretamine | IL1-b production in LPS-stimulated macrophages | 89.4% (50μg/mL) 87.4% (100μg/mL) 71.8% (200 μg/mL) |

(Lemos et al. 2017) | |

| Annonaceae Species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Methodology | Inhibition | Ref. |

|

Duguetia moricandiana |

Fruits | Discretamine | TNF-α production in LPS-stimulated macrophages | 61.0% (50μg/mL) 45.2% (100μg/mL) 52.6% (200 μg/mL) |

(Lemos et al. 2017) |

| Fruits | Discretamine | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | After one hour 42% (10mg/kg) 62% (20mg/kg) |

(Lemos et al. 2017) | |

| Fruits | Discretamine | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | After two hours 44% (10mg/kg) 67% (20mg/kg) |

(Lemos et al. 2017) | |

|

Duguetia moricandiana |

Fruits | Discretamine | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | After four hours 59% (5mg/kg) 49% (10mg/kg) 48% (20mg/kg) |

(Lemos et al. 2017) |

|

Duguetia staudtii |

Stem bark | Pachypodol | Myeloperoxidase dependent (luminol/zymosan) oxidative burst | IC50 = 8.32 μg/mL | (Ngouonpe et al. 2019) |

| Stem bark | Kumatakenin | Myeloperoxidase dependent (luminol/zymosan) oxidative burst | IC50 = 10.64 μg/mL | (Ngouonpe et al. 2019) | |

| Stem bark | 5,4′-dihydroxy-3,7,3′,5′-tetramethoxyflavone | Myeloperoxidase dependent (luminol/zymosan) oxidative burst | IC50 = 6.44 μg/mL | (Ngouonpe et al. 2019) | |

| Stem bark | Pachypodol | Myeloperoxidase independent (lucigenin/PMA) oxidative burst | IC50 = 11.04 μg/mL | (Ngouonpe et al. 2019) | |

| Stem bark | Kumatakenin | Myeloperoxidase independent (lucigenin/PMA) oxidative burst | IC50 = 14.13 μg/mL | (Ngouonpe et al. 2019) | |

| Stem bark | 5,4′-dihydroxy-3,7,3′,5′-tetramethoxyflavone | Myeloperoxidase independent (lucigenin/PMA) oxidative burst | IC50 = 8.55 μg/mL | (Ngouonpe et al. 2019) | |

| Enicosanthum membranifolium |

2β-methoxyhardwickiic acid (-)-Hardwicckiic acid 2β-acetoxyhardwickiic acid 2β-hidroxyhardwickiic acid 15-methozypatagonic acid Indomethacin (Positive control) |

NO production | IC50 μM 65.4 38.9 16.1 82.4 28.9 32.2 |

(Polbuppha et al. 2022) | |

| Annonaceae Species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Methodology | Inhibition | Ref. |

| Isolona dewevrei | Leaves | Essential oil Nordihydroguaiaretic (Positive control) |

Inhibit lipoxygenases (LOX) | 0.0020 (mg/mL) 0.013 (mg/ml) |

(Kambiré et al. 2021) |

| Melodorum fruticosum | Leaves | Melodamide A | Inhibition of superoxide anion generation | IC50 = 5.25 μM | (Chan et al. 2013) |

| Leaves | Melodamide A derivate (2-Cl) |

Inhibition of superoxide anion generation | IC50 = 7.49 μM | (Chan et al. 2013) | |

| Leaves | Melodamide A derivate (3-F) |

Inhibition of superoxide anion generation | IC50 = 5.59 μM | (Chan et al. 2013) | |

| Leaves | Melodamide A derivate (2-Br) |

Inhibition of superoxide anion generation | IC50 = 5.19 μM | (Chan et al. 2013) | |

|

Phaeanthus vietnamensis |

Leaves | spathulenol | NO production in LPS-stimulated BV2 cells | IC50 = 15.7 μM | (Nhiem et al. 2017) |

| Leaves | (8R,80R)-bishydrosyringenin | NO production in LPS-stimulated BV2 cells | IC50 = 25.3 μM | (Nhiem et al. 2017) | |

| Leaves | 1αH,5βH-aromandendrane-4α,10α-diol | NO production in LPS-stimulated BV2 cells | IC50 = 23.0 μM | (Nhiem et al. 2017) | |

| Leaves | 1βH,5βH-aromandendrane-4α,10β-diol | NO production in LPS-stimulated BV2 cells | IC50 = 22.6 μM | (Nhiem et al. 2017) | |

|

Polyalthia longifolia |

Seeds | 16-oxo-cleroda-3,13(14)E-dien-15-oic acid | COX-1, COX-2, and 5-LOX inhibitory activities | 62.85% (COX-2) 26.41% (LOX-5) |

(Nguyen et al. 2020) |

| Seeds | 16-hydroxy-cleroda-3,13-dien-15-oic acid | COX-1, COX-2, and 5-LOX inhibitory activities | 84.98% (COX-2) 30.51% (LOX-5) |

(Nguyen et al. 2020) | |

| Seeds | 16-hydroxy-cleroda-4(18),13-dien-16,15-olide | COX-1, COX-2, and 5-LOX inhibitory activities | 82.97% (COX-2) 12.73% (LOX-5) |

(Nguyen et al. 2020) | |

| Seeds | 3α,16α-dihydroxy-cleroda-4(18),13(14)Z-dien-15,16-olide | COX-1, COX-2, and 5-LOX inhibitory activities | 75.14% (COX-2) 14.38% (LOX-5) |

(Nguyen et al. 2020) | |

|

Polyalthia longifolia |

Seeds | 16α-hydroxy-cleroda-3,13(14)Z-dien-15,16-olide | COX-1, COX-2, and 5-LOX inhibitory activities | 92.94% (COX-1) 79.41% (COX-2) 16,94% (LOX-5) |

(Nguyen et al. 2020) |

| Bark |

16-oxocleroda-4(18),13-dien-15,16-olide |

fMLP/CB induced superoxide generation by neutrophils |

IC50 = 0.60 mg/mL |

(Chang et al. 2006) | |

| Annonaceae Species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Methodology | Inhibition | Ref. |

|

Diphenyleneiodonium (positive control) 16(R&S)-3,13-kolavadien-15,16-olide-2-one |

fMLP/CB induced superoxide generation by neutrophils Phorbol 12-myristate 13 acetate (PMA)-induced action |

IC50 = 0.11 mg/mL IC50 = 10μg/mL |

(Chang et al. 2006) | ||

| Stem bark | Ethyl acetate (EA) extract | Carrageenan-induced paw edema | After four hours 27.5%(50mg/kg) 39.1% (100mg/kg) |

(Kabir et al. 2019) | |

| Leaves | Diethyl ether extract | Xylene-induced ear edema | 42.70% (200mg/kg) 62.67% (400mg/kg) |

(Yasmen et al. 2018) | |

| Leaves | n-hexane extract | Xylene-induced ear edema | 48.54% (200mg/kg) 65.92% (400mg/kg) |

(Yasmen et al. 2018) | |

| Polyalthia viridis | Leaves Stem |

Leaf Essential oil Stem Essential oil Butein (Positive control) |

NO production in LPS stimulated BV2 cells | 80.8 (IC50 = 76.7 μg/mL) 87.2 (IC50 = 57.6 μg/mL) 91.8 (IC50 = 16.1 μg/mL) |

(Son et al. 2021) |

|

Uvaria flexuosa |

Leaves | Flexuvarol B | Superoxide anion generation assay | IC50 = 4.72 mM | (Hsu et al. 2016) |

| Leaves | Chrysin | Superoxide anion generation assay | IC50 = 2.25 mM | (Hsu et al. 2016) | |

| Leaves | Flexuvarol B | Elastase release assay | IC50 = 5.55 mM | (Hsu et al. 2016) | |

| Leaves | Chrysin | Elastase release assay | IC50 = 2.44 mM | (Hsu et al. 2016) | |

| Uvaria grandiflora | Stems | (-) zeylenol | EPP-induced rat ear edema | 90% (15min) 69% (30min) 52% (1 hour) 52% (2 hours) |

(Seangphakdee et al. 2013) |

|

Xylopia aethiopica |

Fruits | Methanolic extract | Prostaglandin synthetase activity | - | (Ezekwesili et al. 2010) |

| Fruits | Ethanolic extract | Mouse pinnal inflammation in carrageenan-induced paw oedema | 23% (30 μg/mL) 62% (300 μg/mL) |

(Obiri and Osafo 2013) | |

| Annonaceae Species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Methodology | Inhibition | Ref. |

| Xylopia aethiopica | Fruits | Extract 30 100 300 |

Superoxide dismutase (SOD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), catalase (CAT), myeloperoxidase (MPO) and malondialdehyde (MDA) activity | 23.06 40.91 62.83 |

(Osafo et al. 2016) |

| Leaves | Hydroethanolic extract | TNF-α in (Lipopolysaccharide) LPS challenged THP-1-derived macrophages | >90% (500 mg/kg) | (Macedo et al. 2020) | |

| Leaves | Hydroethanolic extract | Inhibition of IL-6 production, in a LPS challenged THP-1-derived macrophages, | 84.6% (250 μg/mL) 96.3% (500 μg/mL) |

(Macedo et al. 2020) | |

| Leaves | Hydroethanolic extract | Interferences of 5-LOX in a LPS challenged THP-1-derived macrophages | IC50 = 85 μg/mL | (Macedo et al. 2020) | |

| Fruits | Essential oil | NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells | - | (Alolga et al. 2019) | |

|

Xylopia parviflora |

Fruits | Volatile oil | NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells | 37% (12μg/mL) | (Woguem et al. 2014) |

|

Xylopia sericea |

Leaves | Ethanolic extract | NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells | 76% | (Gomes et al. 2022) |

| Leaves | Ethanolic extract | IL-6 production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells | 85% | (Gomes et al. 2022) |

3.2. Insecticidal, Larvicidal and Pesticidal

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% CL - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona atemoya | Seed | Seed extract | Trichoplusia ni (Lep.) | 197.67 | 301.30 | (de Cássia Seffrin et al. 2010) | |

| Annona squamosa | Seed | Seed extract | Trichoplusia ni (Lep.) | 382.37 | 167.48 | (de Cássia Seffrin et al. 2010) | |

|

Annona cherimola |

Seed |

Squamocin Molvizarin Almunequin Itrabin Deltamethrin (Positive control) |

Oncopeltus fasciatus |

0.16 0.34 11.23 14.91 7.4 |

(Colom et al. 2008) | ||

| Annona cherimola | Seed | Neoannonin Itrabin Almunequin Asimicin Squamocin Motrilin Cherimolin-1 Cherimolin-2 Tucumanin Control |

Spodoptera Frugiperda | 15.5 18.8 19.7 17.3 Instant death 18.0 14.0 17.7 14.7 12.1 |

10 30 30 30 100 20 0 10 20 10 |

0.90 0.59 1.10 0.77 0.16 1.19 0.91 0.97 0.81 1.02 |

(Alvarez Colom et al. 2007) |

| Annona coriaceae |

Seed |

Seed Extract |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

0.01 |

- |

- |

(Costa et al. 2012) |

| Annona coriaceae | Seed | 100 ppm 50 ppm DMSO 0.1% Água (Control) |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | 0.50 0.40 0.30 0.20 |

3.00 6.00 - - |

3.5 5.5 - - |

(Dill et al. 2012) |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods |

Ref. |

||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% CL - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona coriaceae | Seed | Seed Extract 0 ppm 50 ppm 100 ppm 200 ppm 300 ppm 400 ppm 500 ppm |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

0.0 0.7 0.7 1.0 2.2 4.5 6.2 |

0.0 7.5 7.5 10.0 22.5 45.0 62.5 |

10.0 9.25 9.25 9.00 7.75 5.50 3.75 |

(de Moraes et al. 2011) |

| Annona coriaceae | Seed | Seed Extract Methanol (des. Hexane) Hexane Dichloromethane Methanol (des. DCM) |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 |

100.0 100.0 58.75 0.0 |

0.007 0.007 0.805 0.0 |

(Costa, Marilza da Silva, Mônica Josene Barbosa Pereira, Simone Santos de Oliveira, Paulo Teixeira de Souza, Evandro Luiz Dall’oglio 2013) |

| Annona coriaceae | Seed | Diet | Anagasta kuehniella (Lep.) | 0.0 2.0 |

26.3 16.8 |

71.8 81.9 |

(Coelho et al. 2007) |

| Annona coriaceae | Seed | Diet | Corcyra Cephalonica (Lep.) | 0.0 2.0 |

23.16 32.25 |

69.7 49.3 |

(Coelho et al. 2007) |

| Annona coriaceae | Seed | Seed Extract Hexanic 8.0% 4.0% 2.0% 1.0% 0.5% Methanolic 8.0% 4.0% |

Dichelops melacanthus (Hem.) |

78.00 86.00 68.00 58.00 42.00 96.00 |

(Souza, E. M.; Cordeiro, J. R.; Pereira 2007) | ||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% CL - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona coriaceae | Seed | Seed Extract Methanolic 2.0% 1.0% 0.5% Ethanolic 8.0% 4.0% 2.0% 1.0% 0.5% Distilled water (Positive Control) C 01 C 02 |

94.00 94.00 70.00 40.00 100.00 100.00 90.00 84.00 80.00 6.00 4.00 6.00 12.00 0.00 2.00 |

(Souza, E. M.; Cordeiro, J. R.; Pereira 2007) | |||

| Annona coriaceae | Seed | Seed Extract Preview 2 Days 5 Days 7 Days DMSO 20% (Positive Control 01) Water (Positive Control 02) |

Euschistus heros (Hem.) |

3.0 4.6 3.4 3.7 3.1, 5.0, 3.4 and 5.0 4.1, 4.4, 2.8 and 5.2 |

- 8.91 - 26.73 - - |

(Da Silva et al. 2013b) | |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% CL - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona coriaceae | Seed | Seed Extract Methanolic 0.5 1.0 2.0 4.0 8.0 DMSO 20% Water |

Tuta absoluta (Lep.) |

- - - - - - - |

8.0 100 100 86.4 86.6 6.6 13.2 |

- - - - - - - |

(da Silva et al. 2007) |

| Annona cornifolia | Leaves | Leave extract 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 |

Anticarsia gemmantalis (Lep.) |

- - - - - |

0.41 0.38 -0.10 -0.25 0.01 |

- - - - - |

(Saito et al. 2004) |

| Annona cornifolia | Leaves | Leave extract 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 |

Spodoptera frugiperda (Lep.) |

- - - - - |

0.96 0.68 0.55 0.66 0.36 |

- - - - - |

(Saito et al. 2004) |

| Annona cornifolia | Leaves | Leave extract 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 |

Spodoptera frugiperda (Lep.) |

- - - - - |

0.96 0.68 0.55 0.66 0.36 |

- - - - - |

(Saito et al. 2004) |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% CL - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona cornifolia | Leaves | Leave extract 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 |

Spodoptera frugiperda (Lep.) |

- - - - - |

0.96 0.68 0.55 0.66 0.36 |

- - - - - |

(Saito et al. 2004) |

| Annona Crassiflora | Fruits/ Twigs/ Roots | Extract Hexanic SB RW RB Ethanolic RW RB |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

192.57 154.02 264.15 26.89 23.06 |

- - - - - |

- - - - - |

(Rodrigues et al. 2006) |

| Annona Crassiflora | Roots | Extract Root bark Root wood Stem |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

0.71 8.94 16.1 |

- - - |

- - - |

(de Omena et al. 2007) |

| Annona Crassiflora | Seeds | Seeds Extract Methanol (Des. DCM) Hexanic Hydroalcoholic Fraction Ethyl Acetate |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 |

0.0 91.25 0.0 0.0 |

- 0.433 - - |

(Costa, Marilza da Silva, Mônica Josene Barbosa Pereira, Simone Santos de Oliveira, Paulo Teixeira de Souza, Evandro Luiz Dall’oglio 2013) |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% CL - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona Crassiflora | Seeds | Fraction Chloroform Crude Methanolic |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

1.0 1.0 |

0.0 11.25 |

- 3.189 |

(Costa, Marilza da Silva, Mônica Josene Barbosa Pereira, Simone Santos de Oliveira, Paulo Teixeira de Souza, Evandro Luiz Dall’oglio 2013) |

| Annona Crassiflora | Seeds | Seeds Extract 1% 2% 4% DMSO 40% (Positive control) |

Euschistus heros (Hem.) |

481.50 542.00 372.00 683.00 |

1.25 1.50 2.00 1.25 |

353.00 396.00 306.00 309.20 |

(Oliveira and Pereira 2009) |

| Annona Crassiflora | Seeds | Seeds Extract Preview 2 Days 5 Days 7 Days DMSO 20% (Positive control 01) Water (Positive control 02) |

Euschistus heros (Hem.) |

2.4 4.1 3.0 4.2 3.1 5.0 3.4 5.0 4.1 4.4 2.8 5.2 |

17.82 13.04 16.83 - - - - - - - - |

(Da Silva et al. 2013b) |

|

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% CL - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona Crassiflora | Seeds | Seed Extract 24 h 8.0% 4.0% 2.0% 1.0% 0.5% 72 h 8.0% 4.0% 2.0% 1.0% 0.5% 120h 8.0% 4.0% 2.0% 1.0% 0.5% Water + Tween 80 (Positive Control 01) Water (Positive Control 02) |

Tibraca limbativentris (Hem.) |

70.0 64.0 44.0 20.0 6.0 78.0 72.0 54.0 30.0 10.0 81.0 76.0 58.0 34.0 10.0 2.0 4.0 9.0 0.0 2.0 6.0 |

4.46 3.30 |

4.34 3.16 |

(Krinski and Massaroli 2014) |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% CL - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona dioica | Seeds | Seeds Extract Fraction Dichloromethane Methanol |

Aedes Aegypti (Dip.) |

1.0 1.0 |

10.00 3.75 |

2.447 5.196 |

(Costa, Marilza da Silva, Mônica Josene Barbosa Pereira, Simone Santos de Oliveira, Paulo Teixeira de Souza, Evandro Luiz Dall’oglio 2013) |

| Annona dioica | Seeds | Seed Extract Topical application method 25 50 100 200 Cantate application method 25 50 100 200 |

Rhodnius neglectus (Hem.) |

6.2 85 90 100 88.2 91.6 95.6 96.0 |

(Carneiro 2010) | ||

| Annona diversifolia | Leaves/ Branches | Extract Stem Aqueous Ethanolic Leaf Aqueous Ethanolic |

Anastrepa ludens (Dip.) |

588.685 409.139 >1000 52.0284 |

(González-Esquinca et al. 2012) | ||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods |

Ref. |

||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% CL - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona foetida | Seeds | Seed Extract Methanolic 24h 48h |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

76.15 62.28 |

(Guarido 2009) |

||

| Annona foetida | Seeds | Hexanic 24h 48h Dichloromethanic 24h 48h |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

15.17 6.72 0.73 0.33 |

(Guarido 2009) |

||

| Annona glabra | Seeds | Seed Extract | Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | 0.06 | (de Omena et al. 2007) | ||

| Annona montana | Leaves/ Branches | Annonacin Cis-annonacin-10-one Densicomacin-1 Gigantetronenin Murihexocin-B Tucupentol Control |

Spodoptera frugiperda (Hem.) |

49.20 44.75 60.00 55.20 55.12 59.00 27.12 |

50 60 40 70 30 30 0.0 |

50 40 60 30 70 70 10 |

(Toto Blessing et al. 2010) |

| Annona mucosa | Fruits and branches | Ethanolic extract Rollinicin Rolliniastacin-1 |

Aedes aegypti |

2.60 0.78 0.43 |

- |

(Rodrigues et al. 2021) |

|

| Annona mucosa | Fruits and branches | Ethanolic extract Rollinicin Rolliniastacin-1 |

Aedes albopictus |

0.55 1.13 0.20 |

- |

(Rodrigues et al. 2021) |

|

| Annona mucosa | Seeds | Seed Extract 0.5 1.0 2.0 |

Chrysodeixis includens (Lep.) |

< 55% < 55% < 55% |

(Massaroli et al. 2013) |

||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods |

Ref. |

||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% CL - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona mucosa | Seeds | Seed Extract 4.0 8.0 |

Chrysodeixis includens (Lep.) |

86.6% 93.3% |

(Massaroli et al. 2013) | ||

| Annona mucosa | Seeds/ Branches/ Leaves | Extract Seeds 300 mg kg 1500 mg kg Leaves 300 mg kg 1500 mg kg Branches 300 mg kg 1500 mg kg Control |

Sitophilus zeamais (Col.) |

0.80 0.00 36.80 5.60 34.70 39.10 36.90 37.00 |

98.00 100.00 0.50 61.50 1.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 |

7.84 1.12 81.97 57.90 83.71 64.97 81.94 81.74 |

(Ribeiro et al. 2013) |

| Annona mucosa | Seeds | Seed Extract 24h 8.0% 4.0% 2.0% 1.0% 0.5% 72h 8.0% 4.0% 2.0% |

Timbraca limbativentris (Hem.) |

100.0 92.0 90.0 76.0 28.0 100.0 96.0 96.0 |

1.59 1.18 |

0.49 -0.24 |

(Krinski and Massaroli 2014) |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods |

Ref. |

||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona mucosa | Seeds | 1.0% 0.5% 120h 8.0% 4.0% 2.0% 1.0% 0.5% Water + Tween80 (Positive Control 01) Water (Positive Control 02) |

Timbraca limbativentris (Hem.) |

86.0 42.0 100.0 98.0 96.0 88.0 56.0 2.0 4.0 9.0 0.0 2.0 6.0 |

0.91 |

-0.76 |

(Krinski and Massaroli 2014) |

| Annona muricata | Seeds | Seed Extract | Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | 236.23 | 74.68 | - | (Morales et al. 2004) |

| Annona muricata | Seeds | Seed Extract 12h 24h 36h 48h |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

0.18 0.06 0.04 0.02 |

0.10 0.05 0.03 0.01 |

(Bobadilla et al. 2005) |

|

| Annona muricata | Seeds | Seed Extract | Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | 900.0 | 380.0 | (Henao et al. 2007) | |

| Annona muricata | Leaves/ Branches | Extract Leaves Ethanolic Aqueous |

Anastrepha ludens (Dip.) |

831.445 >1000 |

2058.3 3852.6 |

(González-Esquinca et al. 2012) | |

| Annona muricata | Leaves/ Branches | Stems Ethanolic Aqueous |

Anastrepha ludens (Dip.) |

865.0 >1000 |

4539 3984.2 |

(González-Esquinca et al. 2012) |

|

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods |

Ref. |

||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona muricata | Seed | Seed extract | Anopheles albimanus (Dip.) | 16.20 | 0.82 | (Morales et al. 2004) | |

| Annona muricata | Seed | Food consumption (%) Low dose Medium dose Water (Positive Control 01) 10% Ethanol (Positive Control 02) |

Anticarsia gemmantallis (Lep.) |

10.0 30.0 0.0 0.0 |

25.0 29.3 19.9 19.3 |

(Fontana et al. 1998) |

|

| Annona muricata | Seed | Parviflorin Asimicin Sylvaticin Bullatalicin Annomontacin Gigantetrocin A Cypermethrin Chlorpyrifos Hydramethylnon Propoxur Bendiocarb |

Blatella germanica (Blat.) |

0.6 1.8 1.5 6.5 3.6 4.1 0.003 0.3 5.6 39.9 43.2 |

6 10 8 23 23 34 6 3 12 - - |

(Alali et al. 1998) |

|

| Annona muricata | Leaves | Leaves Extract |

Culex Quinquefascintus |

20.87 | 56.47 | (Magadula et al. 2009) | |

| Annona muricata | Seed | Compounds 1 2 Rotenone |

Leptinotarsa dercemlineata (Col.) |

92.18 29.68 100 |

(Guadaño et al. 2000) |

||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods |

Ref. |

||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona muricata | Seeds | Seed Extract | Plutella xylostella (Lep.) | 43.0 | 60.0 | (Sinchaisri et al. 1991) | |

| Annona muricata | Seeds | Seed Extract Hexanic 24h 48h 72h Ethyl Acetathe 24h 48h 72h |

Sithophillus zeamais (Col.) |

11.447 - - - - - |

4.009 3.854 3.760 3.280 2.667 2.542 |

(Llanos et al. 2008) |

|

| Annona muricata | Seeds | Seeds Extract | Zabrotes subsfasciattus (Col.) | 46.0 | 39.1 | 36.4 | (Araújo 2010) |

| Annona reticulata | Seeds | Seed Extract (95% of Methanol) In two periods: 24h and 48h. g/l 2.5 g/l 5.0 g/l 7.5 g/l 10.0 g/l 15.0 g/l 20.0 g/l |

Epilachna vigintioctopunctata (Col.) |

(%) 24h and 48h 6.7 - 13.4 40.0 – 53.4 80.0 – 100 100 – 100 100 – 100 100 – 100 100 – 100 |

(Karunaratne and Arukwatta 2009) |

||

| Annona reticulata | Uninformed | Petroleum ether extract Ethanolic extract |

Rhodnius neglectus (Hem.) |

35.0 Not significant |

(Schmeda-Hirschmann and de Arias 1992) |

||

| Annona reticulata | Seeds | Methanolic extract | Spodoptera litura (Lep.) |

301.30 (259.15-326.33) |

50.0% |

167.48 (110.43-383.65) |

(de Cássia Seffrin et al. 2010) |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods |

Ref. |

||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona salzmannii | Barks |

Hexanic Extract (8,68 g (0,48%) Methanolic Extract 143,29 g (7,96%) CHCl3 alkaloid fraction – FCA |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

615.18 >700.00 163.53 |

(473.71 -981.44) (00.00-00.00) (107.90-238.82) (13.31-19.40) (130.00-218.00) (0.035-0.050) |

(Cruz 2011) |

|

| Annona salzmannii | Barks | Neutral CHCl3 fraction – FCN caryophyllene oxide Temephos |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

15.92 167.00 0.042 |

(Cruz 2011) |

||

| Annona senegalensis | Root | Root Extract Control |

Callosobruchus maculatus (Col.) | 18.7 4.7 |

3.7 98.0 |

0.1 79.5 |

(Aku et al. 1998) |

| Annona senegalensis | Fruits | Ethanolic extract | Culex quinquefascintus (Dip.) | 0.67 | 23.42 | 29.78 |

(Magadula et al. 2009) |

| Annona senegalensis | Uninformed | Extract | Sitophilus zeamais (Col.) | 220.71 | 0.19 – 0.06 | (LS et al. 2004) | |

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Aqueous extract (g/100 ml) 100.0 50.0 25.0 12.5 6.25 3.125 1.5625 Control |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) |

100.0 100.0 83.3 90.0 70.0 76.6 73.3 5.7 |

(Monzon et al. 1994) | ||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods |

Ref. |

||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (µg/ml) 1 |

Aedes albopictus (Dip.) |

388.3 |

397.4 |

486.6 |

(Kempraj and Bhat 2011) |

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (µg/ml) 2 4 6 8 10 20 |

Aedes albopictus (Dip.) |

231.3 162.3 114.0 64.9 45.6 0.0 |

240.3 163.8 112.0 72.4 47.8 0.0 |

268.5 185.4 121.1 84.9 56.3 0.0 |

(Kempraj and Bhat 2011) |

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Ethanol extract (mg/ml) at 24h, 48h and 72h. 5 10 20 30 |

Anopheles gambiae (Dip.) |

3.33 (24h) 6.67 (48h) 23.33 (72h) 16.67 (24h) 33.33 (48h) 63.33 (72h) 40.0 (24h) 66.67 (48h) 76.67 (72h) 53.33 (24h) 73.33 (48h) 90.0 (72h) |

(Allison et al. 2013) |

||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods |

Ref. |

||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Ethanol extract (mg/ml) at 24h, 48h and 72h. 40 |

Anopheles gambiae (Dip.) |

70.0 (24h) 90.0 (48h) 1000 (72h) |

(Allison et al. 2013) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Whole plant | Extract (ppm) 50 100 150 200 |

Anopheles stephensi (Dip.) | (%) 58 60 70 74 |

(%) 4 6 16 18 |

(%) 52 76 86 92 |

(Saxena et al. 1993) |

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Extract (mgl) 500 250 125 62.5 31.25 15.63 7.82 |

Anopheles subpictus (Dip.) | (%) 100 – 0.0 82.6 – 2.46 63.0 – 1.84 48.2 – 4.62 16.4 – 2.04 92.0 – 3.28 4.6 – 4.60 |

(Kamaraj et al. 2011) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Ethanolic extract Aqueous extract |

Bemisia tabaci (Hem.) |

100 – 0.0 99.3 – 1.05 |

(Cruz-Estrada et al. 2013) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (mg/ml) 0.01 0.03 0.05 |

Callasobruchus chinensis (Col.) | (%) 9.66 9.66 41.00 |

(Kotkar et al. 2002) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (mg/ml) 0.07 0.09 |

Callasobruchus chinensis (Col.) | % 81.33 99.00 |

(Kotkar et al. 2002) | ||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (mg/ml) 0.07 0.09 |

Callasobruchus chinensis (Col.) | % 81.33 99.00 |

(Kotkar et al. 2002) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (µg/cm2) Petroleo ether Ethanol Acethone Methanol |

Ceratitis capitata (Dip.) | (%) 0.031 0.632 0.591 4.038 |

(%) 198.57 614.26 1000.40 135.25 |

(Epino and Chang 1993) | |

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (%) 0.05 0.1 Deltamethrin |

Crocidiolomia pavonana (Lep.) |

10.4 ± 1.2 6.3 ± 2.7 11.0 ± 3.6 |

32.0 ± 6.9 69.0 ± 4.8 62.4 ± 5.2 |

(Dadang and Prijono 2009) | |

| Annona squamosa | Seeds |

Aqueous extract (25%) |

Culex quinquefasciatus (Dip.) |

33.6% |

(Pérez-Pacheco et al. 2004) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Ethanol extract (mg/ml) at 24h, 48h and 72h. 5 10 |

Culex quinquefasciatus (Dip.) | (%) 0.0 (24h) 13.33 (48h) 46.67 (72h) 33.33 (24h) 56.67 (48h) 73.33 (72h) |

(Allison et al. 2013) | ||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Ethanol extract (mg/ml) at 24h, 48h and 72h. 20 30 40 |

Culex quinquefasciatus (Dip.) |

56.67 (24h) 70.0 (48h) 90.0 (72h) 80.0 (24h) 96.67 (48h) 100 (78h) 93.33 (24h) 100 (48h) 1000 (72h) |

(Allison et al. 2013) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Aqueous extract (g/100 ml) 100.0 50.0 25.0 12.5 6.25 3.125 1.5625 |

Culex quinquefasciatus (Dip.) | (%) 100.0 60.0 50.0 36.7 26.7 33.3 10.0 |

(Monzon et al. 1994) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Extract | Culex quinquefasciatus (Dip.) | 0.64 | 14.69 | (Magadula et al. 2009) | |

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Methanol Extract (mg/l) 500 |

Culex tritaeniorhynchus (Dip.) | (%) 100.0 ± 00.0 |

(Kamaraj et al. 2011) | ||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Methanol Extract (mg/l) 250 125 62.5 31.25 15.63 7.82 |

Culex tritaeniorhynchus (Dip.) | (%) 88.4 ± 1.64 52.6 ± 4.63 34.2 ± 2.84 20.6 ± 1.67 12.4 ± 2.45 6.8 ± 1.87 |

(Kamaraj et al. 2011) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Diet (µg/2g) 48h |

Drosophila melanogaster (Dip.) |

62.5 |

(Kawazu et al. 1989) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (g/l) 1.0 2.5 5.0 10.0 15.0 20.0 |

Epilachna vigintioctopunctata (Col.) | 24h and 48h (%) 6.7 and13.4 40.0 and 53.4 80.0 and 53.4 100 and 100 100 100 |

(%) 64.8 83.4 92.3 95.9 95.9 100.0 |

(Karunaratne and Arukwatta 2009) | |

| Annona squamosa | Branches | Extract (%) | Musca domestica (Dip.) | 41.00 | (Sharma et al. 2011) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Extract (mg/l) 0 200 400 600 800 1000 |

Musca domestica (Dip.) |

(%) 100 80 65 50 30 0 |

(%) 100 62.5 53.85 40.0 33.33 0.0 |

(Begum et al. 2010) | |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Extract (% plant poder) 5 10 20 |

Oryctes rhinoceros (Col.) | (%) 10 30 50 |

(%) 10 20 20 |

(Sreeletha and Geetha 2012) | |

| Annona squamosa | Leaves | Extract (%) 100 75 50 25 10 5 0.1 |

Periplaneta americana (Blat.) | (%) 80 60 50 20 10 10 0 |

Average 4.00 ± 0.0 3.00 ± 0.0 2.5 ± 0.71 1.00 ± 0.0 0.5 ± 0.701 0.5 ± 0.701 0.0 ± 0.0 |

(Kesetyaningsih 2012) | |

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (mg/ml) 5 10 |

Plutella xylostella (Lep.) | (%) 46.7 70.0 |

(Sinchaisri et al. 1991) | ||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Aqueous extract Larval instar (Time h) 3rd: 24h 48h 72h 4th: 24 48 72 |

Plutella xylostella (Lep.) | (%) 5.2 (3.1-8.5); 1.7 (1.3-2.2); 0.9 (0.7-1.2). 8.7 (6.6-11.3); 4.2 (3.5-5.1); 2.0 (1.7-2.4). |

(%) 2.5 ± 1.4 10.0 ± 6.8 12.5 ± 6.0 0 1.3 ± 1.3 5.0 ± 2.0 |

(Leatemia and Isman 2004) | |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods |

Ref. |

||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Aqueous extract 1% 5% Control 1 (Acetone) Control 2 (Methanol) Control 3 (Without solvente) |

Sitophilus oryzae (Col.) | (LD 50 Min) 23.1 (22.1-23.9) 11.4 (10.7-12.2) 0.0 0.0 0.0 |

(% min) 39.6±1.4 14.5±1.1 - - - |

(Kumar et al. 2010) | |

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (%) 0.5 |

Spodoptera litura (Lep.) |

21.66±1.66 |

0.0 |

28.33±1.66 |

(Deshmukhe et al. 2010) |

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (%) 1 5 10 15 20 25 |

Spodoptera litura (Lep.) |

23.33±1.66 38.33±1.66 48.33±1.66 56.66±1.66 51.66±1.66 61.66±1.66 |

0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 1.66±1.66 1.66±1.66 |

33.33±1.66 51.66±1.66 58.33±1.66 78.33±3.33 75.00±0.0 80.00±0.0 |

(Deshmukhe et al. 2010) |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract Petroleum ether EtOH Acetone Methanol |

Tribolium castaneum (Col.) | LD50 (µg/cm2) 0.031 0.632 0.591 4.038 |

95% (Lower and Upper) 0.006 and 0.150; 0.315 and 1.265; 0.285 and 1.224; 1.727 and 9.440. |

(Khalequzzaman and Sultana 2006) | |

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extracts using two methods of application: Topical (µg/larva) Oral (ppm fresh weight in diet. |

Trichoplusia ni (Lep.) |

301.30 (259.15-326.33) |

167.48 (110.43-383.65) |

(de Cássia Seffrin et al. 2010) | |

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (ppm) Hexane extract 250 500 750 1000 1250 1500 Ethyl Acetate extract 50 250 500 750 1000 1250 |

Trogoderma granarium (Dip.) | (%) 10th day and 15th day 0.0 and 11.13 4.47 and 11.13 11.13 and 17.8 17.8 and 28.87 48.9 and 53.33 75.33 and 82.2 4.47 and 20.00 24.5 and 33.33 26.7 and 55.53 51.13 and 57.8 64.47 and 80.0 84.5 and 91.13 |

(mg) 10th day and 15th day. 66.1 and 80.5 75.1 and 84.6 64.9 and 70.9 63.6 and 71.8 64.9 and 70.1 58.3 and 61.5 73.0 and 86.2 65.6 and 73 72.4 and 81.0 62.9 and 69.5 59.8 and 66.0 56.0 and 61.0 |

(Rao et al. 2005) | |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Annona squamosa | Seeds | Extract (ppm) Methanol extract 500 750 1000 1250 1500 2000 Acetone control Control |

Trogoderma granarium (Dip.) | (%) 10th day and 15th day 6.67 and 8.87 13.34 and 17.8 22.2 and 24.47 20.0 and 26.67 48.87 and 57.7 66.67 and 77.7 0.0 and 0.0; 0.0 and 0.0. |

(mg) 10th day and 15th day. 78.0 and 96.6 74.1 and 93.1 75.2 and 98.2 74.6 and 92.4 58.0 and 85.0 53.4 and 62.5 100.9 and 150.6. 94.9 and 161.6. |

(Rao et al. 2005) | |

| Artabotrys odoratissimus | Bark | Larval instar and exposure periods (h) Second 12h 24h |

Culex quinquefascintus (Dip.) | LC50 52.92 42.03 |

95% (Lower and Upper) 33.59 and 83.87 26.18 and 67.47 |

(Kabir 2010) | |

| Artabotrys odoratissimus | Bark | Larval instar and exposure periods (h) Third 12h 24h Fouth 12h 24h |

Culex quinquefascintus (Dip.) |

110.03 99.13 170.12 110.41 |

72.51 and 166.9 60.2 and 163.29 137.6 and 210.26 89.6 and 135.95 |

(Kabir 2010) | |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Asimina triloba | Roots | Ethanolic extract (Fraction nº.) 017 018 019 020 021 Asimicin |

Acalymma vittatum (Col.) | LC50 (p.p.m.) 7.56 >1000 1.67 0.04 715 0.03 |

(Mikolajczak et al. 1988) |

||

| Cardiopetalum calophyllum | Seeds |

Methanolic extract (1.0 mg/mL) |

Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | (%) 5.00 |

(mg/mL) 1.789 |

(Costa, Marilza da Silva, Mônica Josene Barbosa Pereira, Simone Santos de Oliveira, Paulo Teixeira de Souza, Evandro Luiz Dall’oglio 2013) | |

| Dennettia tripetala | Leaves and roots | Ethanol extract (5mL/100g) in 1, 3 and 7 days. 0.0 |

Dermestes maculatus (Col.) | (%) In 1, 3 and 7 days. 0.0 ± 0.0 0.0 ± 0.0 0.0 ± 0.0 |

(Akinwumi et al. 2007) | ||

| Dennettia tripetala | Leaves and roots | Ethanol extract (5mL/100g) in 1, 3 and 7 days. 2.50 5.00 |

Dermestes maculatus (Col.) | (%) In 1, 3 and 7 days. 26.67 ± 0.88 71.67 ± 0.88 100.0 ± 0.0 26.67 ± 0.67 75.0 ± 1.16 100.0 ± 0.0 |

(Akinwumi et al. 2007) | ||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Dennettia tripetala | Leaves and roots | Ethanol extract (5mL/100g) in 1, 3 and 7 days. 7.50 10.0 |

Dermestes maculatus (Col.) | (%) In 1, 3 and 7 days. 48.33 ± 0.88 91.67 ± 0.33 100.0 ± 0.0 51.67 ± 0.66 98.33 ± 0.33 100.0 ± 0.0 |

(Akinwumi et al. 2007) | ||

| Dennettia tripetala | Seeds | Concentration of plant powder/25g fish Extract Untreated control |

Dermestes maculatus (Col.) | (%) 87.0 100 |

(g) 0.25 0.50 |

(Okonkwo and Okoye 2001) | |

| Dennettia tripetala | Uninformed | Extracts (ppm) 0 10 100 1000 |

Ostrinia nubialis (Lep.) |

5.79 3.13 3.87 3.84 |

(Ewete et al. 1996) | ||

| Dennettia tripetala | Seeds | Extract (ml/25g) 0.1 0.2 0.3 |

Necrobia rufipes (Col.) | (%) 100 100 100 |

(Okonkwo and Okoye 2001) | ||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Dennettia tripetala | Leaves and roots | Extract (%) at 24h, 48h and 72h. 0% |

Sitophilus zeamais (Col.) | (%) at 24h, 48h and 72h. 1.83 1.09 1.75 |

(Umeotok et al. 2013) | ||

| Dennettia tripetala | Leaves and roots | Extract (%) at 24h, 48h and 72h. 1% 5% 10% |

Sitophilus zeamais (Col.) | (%) at 24h, 48h and 72h. 1.50 2.09 2.58 1.50 2.09 3.08 2.83 3.58 4.67 |

(Umeotok et al. 2013) | ||

| Duguetia furfuraceae | Leaves/barks and roots | Extract | Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | (µg/ml) 56.6 |

(Rodrigues et al. 2006) | ||

| Duguetia furfuraceae | Leaves | Extract | Sitophilus zeamais (Col.) | (Proportion of insects in the treated area (SDM)) 0.500 (0.113) |

(Luciana et al. 2013) | ||

| Guatteria blephrophylla | Leaves | Extract (ppm) | Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | 85.74 | (74.05 – 112.78) | 4.48±0.89 | (Aciole et al. 2011) |

| Guatteria friesiana | Leaves | Extract (ppm) | Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | 52.60 | (50.11 – 55.17) | 6.48±0.55 | (Aciole et al. 2011) |

| Guatteria hispida | Leaves | Extract (ppm) | Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | 85.74 | (74.05 – 112.78) | 4.48±0.89 | (Aciole et al. 2011) |

| Mikilua fragans | Aerial parts | Essential oil | Anopheles gambiae (Dip.) |

RC75 (x10-5 mgcm-2) 481 (11, 145) |

(Odalo et al. 2005) | ||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Oxandra cf xylopioides | Leaves | Extract 24h 48h 72h |

Spodoptera frugiperda (Lep.) | ppm 319.61 311.47 294.13 |

(Rojano et al. 2007) | ||

| Rollinia occidentalis | Seeds | Extract (ppm) 50 100 250 |

Spodoptera frugiperda (Lep.) | (%) 5 35 50 |

(%) 30 45 50 |

(%) - 20 - |

(Tolosa et al. 2012) |

| Uvaria scheflerri |

Roots |

Essential oil 5% 1% 0.5% 0.1 |

Anisakis L3 |

- 5 - - |

(Anza et al. 2021) |

||

| Xylopia aethiopica | Leaves and Roots | Extract Ethanolic Water |

Anopheles gambiae (Dip.) | LC50 3.57 4.50 |

(%) 125 (34.72%) 106 (29.44%) |

(Aina et al. 2009) | |

| Xylopia aethiopica | Uninformed | Extract (ppm) 0 10 100 1000 |

Ostrinia nubilalis (Lep.) | (mg) 3.78 3.69 3.87 3.84 |

(Ewete et al. 1996) | ||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances / Extracts | Insect species (Order) | Methods | Ref. | ||

| Topical (LC50 µg/ larva) | Topical (LD50 – 95% LC - µg/nymph) | Oral (LC50 ppm fresh weight in diet) | |||||

| Xylopia aromatica | Leaves/Barks and Roots | Extract | Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | (µg/ml) 384.37 |

(Rodrigues et al. 2006) | ||

| Xylopia caudata | Leaves | Oil | Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | 29.83 (21.87-37.45) | 60.33 (48.04-82.47) | 4.19±0.69 | (Zaridah et al. 2006) |

| Xylopia ferruginea | Leaves | Oil | Aedes aegypti (Dip.) | 74.51 (68.39-86.52) | 106.45 (90.23-159.78) | 8.27±1.88 | (Zaridah et al. 2006) |

3.3. Antimicrobial

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Annona foetida |

Leaves |

Essential oil Chloramphenicol Nystatin (Positive control) |

ATCC 6538 200 20 - |

ATCC 10231 60 - 50 |

(Costa et al. 2009) |

|||||||||||||

|

Annona hypoglauca Mart. |

Bark |

Alkaloid phases FA5 (isoboldine) FA6 (actinodaphnine) |

ATCC 29213 70 70 |

ATCC 25922 - 90 |

ATCC 299212 70 80 |

(Rinaldi et al. 2017) |

||||||||||||

|

Annona muricata |

Leaves |

Dried leaf powder: AM0 (Size bands < 2000) AM1 (Size bands between 0.500 and 0.350) |

ATCC 25923 3120 1560 |

ATCC 25922 1560 1560 |

ATCC 27853 3120 3120 |

ATCC 4352 3120 3120 |

(de Andrade et al. 2019) |

|||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Annona senegalensis |

Root bark |

methanol-methylene chloride extract kaur-16-en-19-oic acid F1 (Subfraction) Ciprofloxacin Gentamicin (Positive controls) |

8750 150 - 1.18 0.23 |

1080 - 40 3.6 0.79 |

(Akah et al. 2012) |

|||||||||||||

|

Annona squamosa |

Leaves |

11-hydroxy-16-hentriacontanona + 10-hydroxy-hentricontanona Palmitone Ciprofloxacin (positive control) |

MTCC 96 25 12.5 0.78 |

MTCC 741 25 6.25 0.78 |

(Shanker et al. 2007) |

|||||||||||||

|

Annona vepretorum |

Leaves |

Crude ethanolic extract Hexanic extract |

ATCC 25923 3120 780 |

ATCC 25922 390 390 |

ATCC 19433 3120 3120 |

ATCC 13883 3120 3120 |

(Almeida et al. 2014) |

|||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Annona vepretorum |

Leaves |

Chloroform extract |

ATCC 25923 1560 |

ATCC 25922 780 |

ATCC 19433 12500 |

ATCC 13883 6250 |

(Almeida et al. 2014) |

|||||||||||

|

Annonidium mannii |

Root Bark |

Crude extract Ciproflocaxin (Positive control) |

ATCC 11296 64 2 |

(Ngangoue et al. 2020) |

||||||||||||||

|

Bocageopsis pleiosperma Maas |

Stem Bark |

Polycarpol Chloramphenicol (Positive control) Ketoconazole (Positive control) |

ATCC 6538 25 25 - |

ATCC 1228 50 50 - |

ATCC 10538 50 50 - |

ATCC 27853 - >500 - |

ATCC 10231 250 - 12.5 |

(da Silva et al. 2015) |

||||||||||

|

Bocageopsis multiflora (Mart.) R.E. Fr |

Leaves |

Essential oil |

ATCC 6538 190 |

ATCC 8739 1500 |

ATCC 9027 3000 |

ATCC 29212 90 |

(Alcântara et al. 2017) |

|||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Bocageopsis multiflora |

Aerial parts |

Essential oil TIENAM (Positive control) |

ATCC 33591 4.68 4.68 |

CDC-EDL 933-171-0157:H3 4.68 1.17 |

ATCC 29336 4.68 2.34 |

(Bay et al. 2019a) |

||||||||||||

|

Cananga odorata |

Essential oil Thymus vulgaris (reference oil) |

ATCC 48274 170 60 |

(Sacchetti et al. 2005) |

|||||||||||||||

|

Cleistopholis patens |

Leaves |

Cleistetroside-8 Cleistetroside-5 Cleistetroside-2 Vancomycin (positive control) |

ATCC 33591 8 8 0.5 1 |

(Hu et al. 2006) |

||||||||||||||

|

Cyathocalyx zeylanicus |

Leaves |

Essential oil Gentamycin Muconazol (Positive control) |

ATCC 25923 250 250 9.0 |

ATCC 25922 125 125 12.0 |

ATCC 37853 250 250 9.1 |

ATCC 27853 250 250 8.0 |

ATCC 90028 250 16 4.5 |

(Hisham et al. 2012) |

||||||||||

|

Annonaceae species |

Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) |

Ref. |

||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Cleistochlamys kirkii (Benth) Oliv. |

Root Bark |

Chamanetin Isochamanetin Dichamanetin Cleistenolide Acetylmelodorinol Amoxicillin Oxacillin Vancomycin (Positive control) |

S. aureus MSSA MRSA VISA ATCC ATCC ATCC FFHB ATCC CIP 6538 43866 9144 29593 700699 106760 7.5 15 30 - 125 15 62 125 250 30 62 62 2 2 1 4 2 2 30 30 7.5 15 30 30 >250 >250 125 >250 >250 >250 0.2 62 250 >250 250 250 0.2 125 125 250 250 250 0.2 0.4 0.4 0.8 2 4 |

VRE HB164 15 30 7.5 30 >250 - - 32 |

(Pereira et al. 2016) |

|||||||||||||

|

Dennetia tripetala Baker f. |

Seed |

Dried seeds essential oil Streptomycin Acriflavin (Positive control) |

NCIB 8586 3.13 - 0.13 |

NCIB 86 6.25 0.13 |

NCIB 950 25.0 1.0 |

NCCYC 6 6.25 - 2.0 |

(Oyemitan et al. 2019) |

|||||||||||

|

Desmopsis bibracteata Desmopsis macrocarpa |

Leaves Leaves |

Essential oil Essential oil |

ATCC 29213 625 1250 |

ATCC 259222 2500 1250 |

(Palazzo et al. 2009) |

|||||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Desmos chinensis |

Leaves |

Essential oil Gentamycin Muconazol (Positive control) |

ATCC 25923 250 250 9.0 |

ATCC 25922 125 125 12.0 |

ATCC 37853 250 250 9.1 |

ATCC 27853 250 250 8.0 |

ATCC 90028 250 16 4.5 |

(Hisham et al. 2012) |

||||||||||

|

Duguetia lanceolata |

Stem bark |

Essential oil (T2) Essential oil (T4) Chloramphenicol (positive control) |

ATCC 6538 60 125 2 |

ATCC 10231 60 100 15 |

(Sousa et al. 2012) |

|||||||||||||

|

Enantia chlorantha |

Stem bark |

Palmitin Chloramphenicol (positive control) |

ATCC 25923 32 8 |

E.C 136 32 32 |

K.L 128 16 32 |

(Etame et al. 2019) |

||||||||||||

|

Ephedranthus amazonicus R.E. Fr. |

Leaves |

Essential oil Chlorhexidine digluconate (Positive controls) |

ATCC 6538 90 6 |

ATCC 8739 1500 6 |

ATCC 9027 3000 10 |

ATCC 29212 190 90 |

(Alcântara et al. 2017) |

|||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Fissistigma kwangsiensis |

Leaves |

Essential oil Nystatine Streptomycin Cycloheximide (Positive controls) |

ATCC 25923 55.67 - 3.2 - |

ATCC 27853 3.45 8.0 - - |

ATCC 299212 33.62 2.07 - - |

ATCC 10231 16.45 - - 3.2 |

(Tsiang et al. 2022) |

|||||||||||

|

Fusaea longifolia |

Aerial parts |

Essential oil TIENAM (positive control) |

ATCC 33591 37.5 4.68 |

ATCC 29336 37.5 2.34 |

(Bay et al. 2019a) |

|||||||||||||

|

Greenwayodendron suaveolens subs. usambaricum |

Root Bark Roots |

Methanol extracts Pentacyclindole Polyalthenol Ciprofloxacin (Positive control) |

ATCC 25923 1000 4 4 2.5 |

(Christopher et al. 2018) (Williams et al. 2010) (Williams et al. 2010) (Christopher et al. 2018) |

||||||||||||||

|

Goniothalamus gracilipes |

Leaves |

Gracilipin C Streptomycin (Positive control) |

ATCC 25923 32 32 |

(Trieu et al. 2021) |

||||||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Goniothalamus longistipetes |

Bark |

(+)-altholactone ((2S,3R,3aS,7aS)-3-hydroxy-2-phenyl-2,3,3a,7a-tetrahydrobenzo-5(4H)-5-one) (2S,3R,3aS,7aS)-3-hydroxy-2-phenyl-2,3,3a,7a-tetrahydrobenzo-5(4H)-5-one) 2,6-dimethoxyisonicotinaldehyde alkenyl-5-hydroxyl-phenyl benzoic acid |

eMRSA – 15 64 128 128 8-16 |

NCTC 10418 256 512 256 512 |

NCTC 10662 500 512 256 128 |

NCTC 10662 256 512 256 128 |

(Teo et al. 2020) |

|||||||||||

|

Guatteria blepharophylla |

Leaves |

Essential oil Isomoschatoline Chlorhexidine digluconate Nystatin (Positive control) |

ATCC 6538 50 - 6 |

ATCC 8739 1500 - 6 |

ATCC 9027 1500 - 10 |

ATCC 29212 50 - 90 |

ATCC 10231 - 50.81 µM L-1 54 µM L-1 |

(Costa et al. 2011c; Alcântara et al. 2017) |

||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Guatteria costaricensis Guatteria diospyroides Guatteria oliviformis |

Leaves |

Essential oil Essential oil Essential oil |

ATCC 29213 1250 312 1250 |

ATC 25922 1250 1250 625 |

(Palazzo et al. 2009) |

|||||||||||||

|

Guatteria selowiana Guatteria latifolia Guatteria ferruginea Guatteria australis |

Aerial parts Aerial parts Aerial parts Aerial parts |

Essential oil Essential oil Essential oil Essential oil Chloramphenicol (Positive control) |

ATCC 11775 600 600 600 >1000 40 |

(Santos et al. 2017) |

||||||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Guatteria citriodora |

Leaves and Stem bark |

Crude hydroalcoholic extract of leaves Alkaloid fraction of leaves Alkalidic fraction of stem bark Imipenem (Positive control) |

250 - - 15.6 |

ATCC 4083 - 125 - 62.5 |

(Rabelo et al. 2014) |

|||||||||||||

|

Guatteria punctata |

Aerial parts |

Essential oil TIENAM (positive control) |

ATCC 33591 - 4.68 |

CDC-EDL 933-171-0157:H3 - 1.17 |

ATCC 29336 - 2.34 |

(Bay et al. 2019a) |

||||||||||||

|

Guatteriopsis hispida |

Essential oil Oxide caryophyllene |

ATCC 6538 >1000 - |

ATCC 12228 >1000 - |

ATCC 11775 >1000 - |

ATCC 133388 >1000 - |

ATCC 10231 >1000 600 |

(Costa et al. 2008) |

|||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Guatteriopsis blepharopylla Guatteriopsis friesiana |

seed |

Essential oil β-eudesmol Ƴ-eudesmol α-eudesmol Essential oil β - pinene α – pinene (E)- caryophyllene Chloramphenicol Nystatin (Positive control) |

ATCC 6538 1000 >1000 600 250 125 - - - 20 - |

ATCC 12228 >1000 600 700 700 100 - - - 40 - |

ATCC 11775 >1000 >1000 >1000 - 900 - - - 40 |

ATCC 133388 >1000 >1000 300 200 900 - - - 850 |

ATCC 10231 700 125 500 125 500 100 250 - 50 |

(Costa et al. 2008) |

||||||||||

|

Mitrephora celebica |

Leaves Stem bark Twigs |

Crude hydroalcoholic extract of leaves Crude hydroalcoholic extract Crude hydroalcoholic extract Ent-trachyloban-19-oic acid |

ATCC 43300 >100 12.5 >100 6.25 |

ATCC 27853 >100 >100 >100 >100 |

(Zgoda-Pols et al. 2002) |

|||||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Mitrephora celebica |

ent-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid Gentamycin Oxacillin Vancomycin (Positive control) |

ATCC 43300 >100 >50 6.2-12.5 0.8 |

ATCC 27853 >100 0.8 - - |

(Zgoda-Pols et al. 2002) |

||||||||||||||

|

Monodora myristica |

Fruits |

Cyclohexane extract Ethyl acetate extract |

25 25 |

25 50 |

- 50 |

12.5 12.5 |

6.3 12.5 |

(Mbosso et al. 2010) |

||||||||||

|

Polyalthia cinnamomea |

Leaves |

Leaf extract Vancomycine Streptomicyne Kanamycine (Positive control) |

ATCC 25923 4000 - 30 - |

4000 30 - - |

ATCC 10536 1000 - - 30 |

(Mahmud et al. 2018) |

||||||||||||

|

Polyalthia longifolia |

Stem bark |

Butanol fraction 3-o-methyl ellagic |

ATCC 29213/ 512 (MRSA) 320/320 80/160 |

ATCC 29212 320 80 |

ATCC 27853 160 80 |

(Jain et al. 2014) |

||||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Polyalthia longifolia |

Stem bark Roots Leaves |

Vancomycin Oxacillin Ciprofloxacin (Controle positive) Pendulamine A Pendulamine B Penduline Kanamycin sulfate (Control positive) Methanol extract 16(R and S)-hydroxy-cleroda-3,13(14)Z-dien-15,16-olide 16-oxo-cleroda-3,13(14)E-dien-15-oic acid |

ATCC 29213/ 512 (MRSA) 0.25/- -/8.0 - 0.2 0.2 12.5 0.31 125 7.8 500 |

ATCC 29212 - - 0.015 |

ATCC 27853 - - 0.25 2 - - 5 125 250 500 |

2 2 - 5 |

(Jain et al. 2014) (Jain et al. 2014) (Jain et al. 2014) (Faizi et al. 2003) (Faizi et al. 2003) (Faizi et al. 2003) (Faizi et al. 2003) (Faizi et al. 2008) (Faizi et al. 2008) (Faizi et al. 2008) |

|||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Toussaintia orientalis Verdc. |

Seeds |

Toussintine A Toussintine B Toussintine C Toussintine D Toussintine E Ampicilin (Positive control) |

ATCC 25923 - 10 - 5 - 2.5 |

DSM 1103 10 20 10 - - 2.5 |

(Samwel et al. 2011) |

|||||||||||||

|

Unonopsis duckei R.E. Fr. Unonopsis floribunda Diels Unonopsis rufescens (Baill.) R.E. Fr. Unonopsis stipitala Diels Onychopetalum amazonicum R.E. Fr. |

Stem Bark |

Polycarpol Chloramphenicol (Positive control) Ketoconazole (Positive control) |

ATCC 6538 25 25 - |

ATCC 1228 50 50 - |

ATCC 10538 50 50 - |

ATCC 27853 - >500 - |

ATCC 10231 250 - 12.5 |

(da Silva et al. 2015) |

||||||||||

|

Unonopsis costaricensis |

Leaves |

Essential oil |

ATCC 29213 625 |

ATCC 25922 1250 |

(Palazzo et al. 2009) |

|||||||||||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) | Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Uvaria hamiltonii |

Leaves |

Essential oil Nystatine Streptomycin Cycloheximide (Positive controls) |

ATCC 25923 20.34 - 1.07 - |

ATCC 27853 12.34 8.0 - - |

ATCC 29212 7.99 0.48 - - |

ATCC 10231 32.57 - - 3.2 |

(Tsiang et al. 2022) |

|||||||||||

|

Uvaria schefflera |

Leaves |

5,7,8-trimetoxiflavona 2’,6’-dihydroxy-4’-methoxychalcone and 5,7-dihydroxyflavone (mixture) Ampicillin Ketoconazole (positive control) |

NCTC 6571 - 125 0.01 |

NCTC 10418 125 - 0.25 |

HG 392 - 31.2 0.125 |

(Moshi et al. 2004) |

||||||||||||

|

Uvaria tanzaniae |

Root Bark |

Methanol extracts Ciprofloxacin (Positive control) |

ATCC 25923 1.25 2.5 |

(Christopher et al. 2018) |

||||||||||||||

|

Annonaceae species |

Used Material |

Substances/ Extracts |

Microorganisms / MIC (µg/mL) |

Ref. | ||||||||||||||

| S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | E. faecalis | K. pneumoniae | C. krusei | C. albicans | C. tropicalis | ||||||||||

|

Uvariodendron usambarense |

Leaves Stem Bark |

Methanol extracts Methanol extracts Ciprofloxacin (Positive control) |

ATCC 25923 8000 4000 2.5 |

ATCC 8740 500 - 0.63 |

(Christopher et al. 2018) |

|||||||||||||

|

Xylopia staudtii |

Bark |

Hydroethanolic extract Ciprofloxacin (Positive control) |

ATCC 25922 83.33 0.97 |

(Pouofo Nguiam et al. 2021) |

||||||||||||||

|

Xylopia aromatica (Lam.) Mart. |

Leaves |

Essential oil Chlorhexidine digluconate (Positive control) |

ATCC 6538 1200 6 |

ATCC 8739 3000 6 |

ATCC 9027 3000 10 |

ATCC 29212 50 90 |

(Alcântara et al. 2017) |

|||||||||||

|

Xylopia sericea |

Fruits |

Essential oil Chloramphenicol Ciprofloxacin (positive control) |

ATCC 6538 7.8 12.5 0.39 |

ATCC 10536 1000 6.25 1.56 |

ATCC 19433 1000 6.25 1.56 |

ATCC 4552 62.5 12.5 12.5 |

(Mendes et al. 2017) |

|||||||||||

3.4. Leishmanicidal

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Leishmania spp. | Parasite form | IC50 | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| µM | µg/ml | ||||||

| Anaxagorea dolichocarpa | root | Sampangine Imbiline 3 Imbiline 1 EupolaUramine |

L. donovani | Promastigote | 24.06 16.91 18.20 19.90 |

5.59 5.45 5.32 5.26 |

(Lorenzo et al. 2016) |

| Annickia kummeriae | leave | Methanolic extract Lysicamine Trivalvone Palmatine Jatrorrhizine Jatrorrhizinne/Columbamine Palmatine/Tetrahydro-palmetine |

L. donovani | Amastigote | 9.26 5.24 22.13 60.28 19.35 9.88 |

9.25 2.7 2.9 7.8 20.4 13.1 7.0 |

(Malebo et al. 2013b) |

| Annona crassiflora | Stem bark, stem wood, root bark and root wood | Ethanolic extract Stem bark Stem wood Root bark Root wood |

L. donovani | Promastigote |

12.4 8.3 3.7 8.7 |

(De Mesquita et al. 2005; Brígido et al. 2020) | |

| Annona coriaceae | leave | Essential oil | L. chagasi | Promastigote | 39.93 | (Siqueira et al. 2011) | |

| Annona cornifolia | seed | Annofolin Annotacin Extract |

L. amazonensis | Amastigote | 6.4 7.2 |

175.0 |

(Lima et al. 2014; Brígido et al. 2020) |

| Annona foetida | bark | Hexane extract Dichlorometahne extract Alkaloid fraction (Dichlorometane extract) Methanolic extract Alkaloid fraction (Methanolic extract) N-hydroxyanno-montine |

L. braziliensis and L. guyanensis | Promastigote |

911.3 and 1577.8 |

>160.0 and 42.7 23.0 and 2.7 23.0 and 2.7 40.4 and 23.6 24.3 and 9.1 252.7 and 437.5 |

(Costa et al. 2009; Brígido et al. 2020) |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Leishmania spp. | Parasite form | IC50 | Ref. | |

| µM | µg/ml | ||||||

| Annona foetida | Bark Leave |

O-methylmoschatolin Liriodenine Annomontine Essential oil |

L. braziliensis and L. guyanensis L. amazonensis, L. braziliensis, L. chagasi and L. guyanensis |

Promastigote | 998.35 and 322.7 212.52 and 78.10 >2346.15 |

320.8 and 103.7 58.5 and 21.5 34.8 and >613.0 16.2, 9.9, 27.2 and 4.1 |

(Costa et al. 2009; Brígido et al. 2020) |

| Annona glabra | leave | Hydroalcoolic extrac | L. amazonensis | Promastigote | 37.8 | (Brígido et al. 2020) | |

| Annona glauca | seed | Dichloromethane extract Hexane extract Annonacin A Goniothalamicin Glaucanisin Rolliniastatin-2 Squamocin Glaucafilin Molvizarin Parviflorin Annonacin |

L. braziliensis, L. amazonensis and L. donovani |

Promastigote |

16.75 8.37 40.13 40.13 40.13 41.88 >168.09 >168.09 21.61 |

IC100 25.0 >100.0 10.0 5.0 25.0 25.0 25.0 25.0 >100.0 >100.0 12.5 |

(Waechter et al. 1998) |

| Annona haematantha | root | Argentilactone | L. donovani, L. major and L. amazonensis | Promastigote | 51.47 | 10.0 | (Waechter et al. 1997) |

| Annona mucosa | Leave Seed |

Hexane extract Dichloromethane extrac Methanol extract Hexane extract Methanol extract Liriodenine |

L. amazonensis and L. braziliensis |

Promastigote |

5.19 and 203.15 |

24.24 and 65.17 9.32 and 27.42 28.32 and 44.74 44.2 and 170.15 46.54 and 133.8 1.43 and 55.92 |

(De Lima et al. 2012; Brígido et al. 2020) |

| Annona muricata | leave | Ethil acetate extract | L. amazonensis, L. donovani | Promastigote | 25.0 | (Osorio et al. 2007; Vila-Nova et al. 2011; Brígido et al. 2020) | |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Leishmania spp. | Parasite form | IC50 | Ref. | |

| µM | µg/ml | ||||||

| Annona muricata | Stem | Hexane extract Methanolic extrac Hexane extract Ethil acetate extract Methanolic extrac |

L. amazonensis, L. brasiliensis and L. donovani | Promastigote | >100.0 >100.0 98.6 63.2 98.6 |

(Osorio et al. 2007; Vila-Nova et al. 2011; Brígido et al. 2020) | |

| seeds | Annonacinone | L. chagasi | Promastigote and Amastigote | 63.20 and 22.69 | 37.6 and 13.5 | ||

| L. donovani, L. mexicana and L. major | Promastigote | 12.87, 13.44 and 11.29 | 7.66, 8.00 and 6.72 | ||||

| Corossolone | L. chagasi | Promastigote and Amastigote | 44.74 and 49.57 | 25.9 and 28.7 | |||

| L. donovani, L. mexicana and L. major | Promastigote | 32.35, 32.19 and 27.88 | 18.73, 18.64 and 16.14 | ||||

| Scoparone | L. donovani, L. mexicana and L. major | Promastigote | 133.42, 44.18 and 69.69 | 27.51, 9.11 and 14.37 | |||

| Annona purpurea | Bark Seed Leave |

Methanolic extract Aqueous extract Hydroalcoolic fraction |

L. donovani L. panamensis |

Promastigote | 113.24 28.57 289.0 0.961 |

(Brígido et al. 2020) | |

| Annona spinescens |

Bark Root |

Annonaine Liriodenine |

L. braziliensis L. amazonensis L. donovani L. braziliensis |

Promastigote |

188.45 94.22 376.91 363.29 |

IC100 50.0 25.0 100.0 100.0 |

(Emerson F. Queiroz et al. 1996) |

| Annona squamosa | leave | O-methylarmepavine C37 trihydroxy adjacent bistetrahydrofuran acetogenin |

L. chagasi | Promastigote and Amastigote | 71.16 and 77.58 42.44 and 40.67 |

23.3 and 25.4 26.4 and 25.3 |

(Vila-Nova et al. 2011) |

| Annona senegalensis | leave Stem |

Ethanolic extract | L. donovani | Promastigote | 10.8 27.8 |

(Ohashi et al. 2018; Brígido et al. 2020) | |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Leishmania spp. | Parasite form | IC50 | Ref. | |

| µM | µg/ml | ||||||

| Bocageopsis multiflora | leave | Essential oil | L. amazonensis | Promastigote | 14.6 | (Oliveira et al. 2014) | |

| Duguetia furfuracea | bark | Alkaloid extract Duguetine Duguetine β-N-oxide Dicentrinone N-methyltetrahydropalmatine N-methylglaucine |

L. braziliensis | Promastigote | 16.32 4.32 0.11 0.01 17.03 4.88 |

(da Silva et al. 2009) | |

| Duguetia lanceolata | leave | Glaucine | L. infatum | Amastigote and Promastigote |

21.10 and >281.37 | 7.5 and >100.0 | (Dantas et al. 2020) |

| Enantia chlorantha | stem bark | Aqueous extract | L. infatum | Promastigote | 10.08 | (Olivier et al. 2015) | |

| Guatteria amplifolia | leave | Xylopine Nornuciferine |

L. mexicana and L. panamensis | Promastigote | 3.0 and 6.0 14.0 and 28.0 |

(Montenegro et al. 2003) | |

| Guatteria australis | leave | Essential oil | L. infatum | Promastigote | 30.71 | (Siqueira et al. 2015) | |

| Guatteria boliviana | bark | Ethanolic extract Puertogaline A Puertogaline B Sepeerine |

L. amazonensis, L. braziliensis and L. donovani |

Promastigote |

177.74 177.74 168.15 |

100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 |

(Mahiou et al. 2000a) |

| Guatteria dumetorum | leave | Cryptodorine Normantenine |

L. mexicana and L. panamensis | Promastigote | 3.0 and 6.0 24.0 and 15.0 |

(Montenegro et al. 2003) | |

| Guatteria latifolia | branch | Crude extract Buthanolic fraction 1 Buthanolic fraction 2 |

L. amazonensis | Promastigote and Amastigote | 51.7 and 30.5 25.6 and 10.4 16.0 and 7.4 |

(Ferreira et al. 2017) | |

| Greenwayodendron suaveolens | Fruit, leave, root bark and stem bark | Dichlorometahne fraction rich in alkaloids Petroleum ether fraction rich in lipids and waxes Methanolic fraction rich in steroids and terpenes |

L. infatum | Promastigote | 24.05, 34.56, 0.63 and 20.32 24.05, 8.0, 27.27 and 5.04 40.32, 32.46, 7.51 and 6.82 |

(Muganza et al. 2016) | |

| Leave, root, stem bark | Crude ethanolic extract | 43.07, 8.11 and 24.05 | |||||

| Stem bark | Polycarpol Dihydropolycarpol Polyathenol |

3.2 8.0 8.1 |

|||||

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Leishmania spp. | Parasite form | IC50 | Ref. | |

| µM | µg/ml | ||||||

| Isolona hexaloba | Leave Root bark Stem bark |

Aqueous extract Methanolic extract Dichloromethane fraction Dichloromethane fraction |

L. infatum | Promastigote | 2.0 6.35 6.96 8.0 |

(Musuyu Muganza et al. 2015) | |

| Polyathia macropoda | Stem bark | (4S,9R,1OR) methyl 18- carboxy-labda-8, 1 3(E)-diene-15-oate |

L. donovani | Promastigote | 0.75 | (Richomme et al. 1991) | |

| Polyathia suaveolens | stem bark | Methanolic extract | L. infatum | Promastigote | 1.8 | (Lamidi et al. 2005) | |

| Porcelia macrocarpa | Seeds | Docos-13-yn-21-enoic acid 3-hydroxy-4-methylene-2-(eicos-11’-yn-19’-enyl)but-2-enolide 3-hydroxy-4-methylene-2-(octadec-9’-yn-17’-enyl)but-2-enolide 3-hydroxy-4-methylene-2-(hexadec-7’-yn-15’-enyl)but-2-enolide (2S,3R,4R)-3-hydroxy- 4-methyl-2-(eicos-11’-yn-19’-enyl)butanolide Miltefosine (positive control) |

L. infantum | Amastigotes | 48.5 9.2 10.4 11.0 29.9 17.8 |

(Brito et al. 2021) | |

| Porcelia macrocarpa | Seeds | (2S,3R,4R)-3-hydroxy- 4-methyl-2-(n-eicos-11’-yn-19’-enyl)butanolide (1) (2S,3R,4R)-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-2-(n-eicos-11’- ynyl)butanolide (2) Mixture of 1 and 2 2:1 1:1 1:2 |

L. infantum | Amastigotes |

29.9 Non active 8.4 13.6 19.4 |

(Brito et al. 2022) | |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Leishmania spp. | Parasite form | IC50 | Ref. | |

| µM | µg/ml | ||||||

| Porcelia macrocarpa | Seeds | (2S,3R,4R)-3-hydroxy-4-methyl-2-(n-eicosyl)butanolide (3) | L. infantum | Amastigotes | Non active | (Brito et al. 2022) | |

| Raimondia monoica | leave | (–)-argentilactone (6S)-(50-oxohepten-10E,30Edienyl)- 5,6-dihydro-2H-pyran-2-one (6R)- (50-oxohepten-10Z,30E-dienyl)-5,6-dihydro-2H-pyran-2-one |

L. panamensis | Promastigote | 51.47 9.2 2.03 |

10.0 1.9 0.42 |

(Carmona et al. 2003) |

| Rollinia emarginata | stem bark |

Hexanic extract Dichloromethane extract Methanolic extract Rollidecin B Rolliniastatin-1 Lirioresinol B Squamocin Liriodenine Sylvaticin |

L. braziliensis, L. amazonensis and L. donovani |

Promastigote |

78.25 8.02 >239.0 8.02 18.16 15.65 |

IC100 >100.0 100.0 >100.0 50.0 5.0 >100.0 5.0 5.0 10.0 |

(Février et al. 1999) |

| Rollinia exsucca | stem | Hexane extract |

L. amazonensis, L. braziliensis and L. donovani |

Promastigote | 20.8 | (Osorio et al. 2007) | |

| Rollina pittieri | leave | Hexane extract Ethyl acetate extract Metanolic extract |

L. amazonensis, L. braziliensis and L. donovani |

Promastigote | 12.6, 10.7 and 10.7 20.8 19.7, 31.4 and 43.8 |

(Osorio et al. 2007) | |

| stem | Hexane extract Ethyl acetate extract |

13.5, 15.1 and 15.1 20.8, 25.0 and 19.7 |

|||||

| Unonopsis buchtienii | Stem bark |

Petroleum ether extract Dichloromethane extract O-methylmoschatoline Lysicamine Fraction containing Unonopsine |

L. major and L. donovani | Promastigote |

155.61 85.82 |

IC100 50.0 100.0 50.0 25.0 25.0 |

(Waechter et al. 1999) |

| Annonaceae species | Used Material | Substances/Extracts | Leishmania spp. | Parasite form | IC50 | Ref. | |

| µM | µg/ml | ||||||

| Unonopsis buchtienii | Stem bark | β-Sitosterol Stigmasterol Liriodenine |

L. major and L. donovani | Promastigote | >241.13 >242.30 11.33 |

>100.0 >100.0 3.12 |

(Waechter et al. 1999) |

| Unonopsis duckei | Twigs, barks and leaves | Alkaloidal fraction | L. amazonensis | Promastigote | 155.61, 32.16 and 4.0 | (da Silva et al. 2012) | |

| Unonopsis guatteriodes | Twigs, barks and leaves | Alkaloidal fraction | L. amazonensis | Promastigote | 1.07, 1.90 and 2.79 | (da Silva et al. 2012) | |

| Uvaria afzelii | root | Bigervone | L. donovani and L. major | Promastigote | 38.9 and 44.4 | (Okpekon et al. 2015) | |

| Uvaria klaineana | stem | Klaivanolide | L. donovani | Promastigote | 1.75 | (Akendengue et al. 2002) | |

| Xylopia aromatica | leave | Methanolic extract |

L. amazonensis, L. braziliensis and L. donovani |

Promastigote | 20.8 | (Osorio et al. 2007) | |

| Xylopia discreta | Leave | Ethanol extract Ether petroleum extract Acetate extract Methanol extract Essential oil |