1. Introduction

A Josephson junction consists of two superconductors separated by a thin insulating layer [

1]. Josephson predicted that Cooper pairs could quantum-tunnel through the insulator between the superconductors, generating a spontaneous critical current without an external electric field; with an external field applied, the current exhibits periodic oscillation—effects fully validated by experiments [

2,

3,

4]. However, Josephson’s framework relies on the BCS theory wave function, which is not a rigorous derivation from quantum or quantum field theory but rather an intuition-based conjecture [

5]. Critically, BCS theory only applies to conventional superconductors, whereas the Josephson effect is ubiquitous in junctions with both conventional and unconventional superconductors—indicating Josephson’s theory is not fundamental, and a more intrinsic physical mechanism must underpin the effect. Further, the wave function describes probability amplitude evolution, but the “Cooper pair tunneling” hypothesis lacks dynamic depiction of how pairs traverse the insulator or intuitive explanation of their microscopic interaction with the insulator. Notably, no experimental evidence confirms Cooper pairs actually cross the insulator, necessitating a re-examination of the Josephson effect’s essence.

As a material particle with radius, mass, and charge, an electron cannot traverse an insulator without interaction or energy loss, but its massless electric field easily penetrates ultra-thin insulators. Thus, the Josephson current is likely a displacement current (generated by tiny electron displacements, as varying electric fields induce magnetic fields), rather than involving wavefunction or Cooper pair traversal—these are replaced by electromagnetic waves and electron-hole pairs, respectively, in our new framework. The 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics recognized John Clarke, Michel H. Devoret, and John M. Martinis for discovering macroscopic quantum tunneling and energy quantization in Josephson junction circuits [

6,

7,

8]; our study, however, demonstrates the microscopic Josephson effect is a microelectronic circuit phenomenon, where the junction acts as a microcapacitor. Specifically, the effect originates from opposite induced charges on the insulator’s two sides, driven by symmetry breaking of electronic states in the superconductors.

Building on the superconductivity theory centered on real-space localized electron-hole pair symmetry breaking—one that has successfully predicted and explained nearly all high-temperature superconductivity experiments [

9,

10]—this paper highlights that the elementary charge

e (with intrinsic material and interaction properties) is more suitable than Planck’s constant

h as the quantum constant for describing microscopic quantum phenomena. This is rooted in

e’s inherent quantization: any natural charge

Q can be expressed as

(

). Under this new paradigm, key concepts (electric dipoles, capacitance, magnetic flux, displacement current, magnetic monopoles) are unified, providing a consistent explanation for the intrinsic origins of three core condensed matter phenomena: flux quantization, the quantum Hall effect, and the Josephson effect. Without invoking wavefunctions or Cooper pair tunneling, we derive the DC and AC Josephson current equations via strict analytical deductions.

This study carries profound implications for physics: 1) It theoretically identifies electrons as magnetic monopoles, resolving the nearly century-long puzzle of magnetic monopole existence; 2) It clarifies that magnetism arises from electron-hole pair symmetry breaking, unrelated to any electron motion; 3) It achieves mathematical symmetry in Maxwell’s equations. We contend this work will trigger a paradigm shift, reshaping understanding of fundamental laws in condensed matter phase transitions, electrodynamics, and quantum mechanics.

2. Electron-Hole Pair Crystals and Symmetry-Breaking Phase Transitions

In the previous series of articles [

9,

10], we proposed a new paradigm of quantum well-localized electrons, successfully addressing numerous high-temperature superconductivity issues. In fact, the most fundamental characteristic of solid-state materials is electrical neutrality. The total positive and negative charges of the material are strictly equal, which simplifies the study of phase transitions in superconducting materials. As shown in

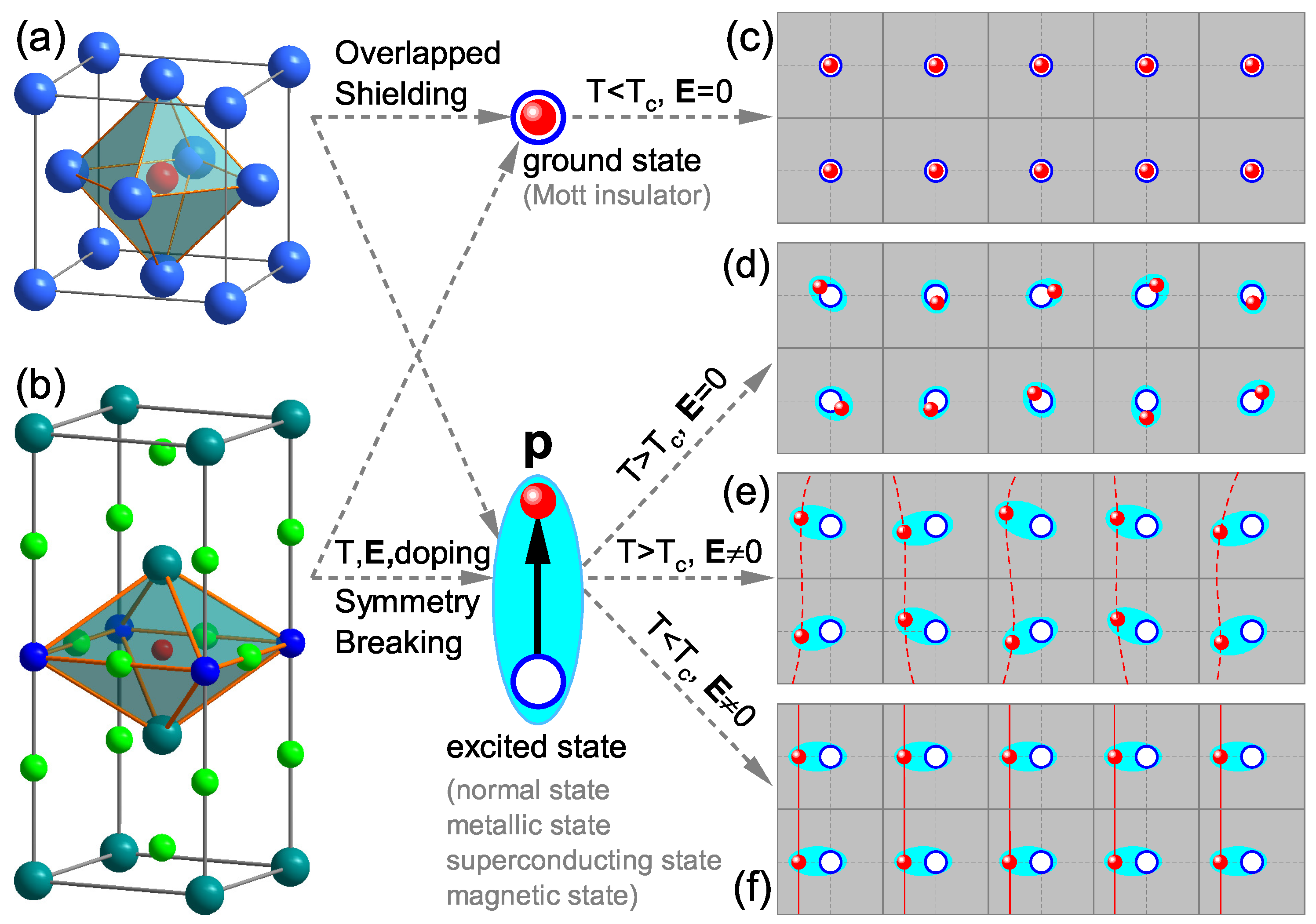

Figs. 1(a) and (b), whether for simple elemental superconductors or complex high-temperature superconductors, valence electrons are not free but localized in a polyhedral quantum well (see the inserted schematic in the middle). The unit cell of the lattice structure can be simplified as an equivalent positive charge hole (blue circles).

Electrons exist in only two possible states: (1) the ground state (Mott insulating state) [

11], where electrons and holes are fully coincident (the inset up diagram in the middle of

Fig. 1); (2) the excited state, where electrons and holes are separated by symmetry breaking (characterized by the electric dipole moment vector

which can act as the order parameter for phase transitions [

12]; note that textbooks typically adopt

, the inset down diagram). In the ground state, electrons are completely screened by holes, with the corresponding crystal structure corresponding to the Mott insulator illustrated in

Fig. 1(c). Electrons can transition from the ground state to the excited state via temperature adjustment, external electric field application, doping, or pressure loading. As shown in

Fig. 1(d), when

, without an external electric field, electrons undergo random thermal oscillations around holes—this constitutes the origin of black-body radiation. As depicted in

Fig. 1(e), upon applying an external electric field to the state in

Fig. 1(d), electrons exhibit both directional displacement and random thermal motion, leading to the coexistence of electric current and resistance. As presented in

Fig. 1(f), applying an electric field to the insulating state in

Fig. 1(c) or cooling the metallic state in

Fig. 1(e) results in a superconducting state, wherein perfect symmetry breaking occurs along the direction of the electric field. Here, resistance vanishes, and the current transforms into a lossless superconducting displacement current. Additionally,

Fig. 1(f) can describe the magnetic state: unlike the superconducting state, symmetry breaking in magnetic materials is spontaneous, which will be discussed in detail in the subsequent chapter.

3. Magnetic Monopoles and the Nature of Magnetism

To explain the origin of magnetism, Paul Dirac first predicted the existence of magnetic monopoles in 1931 [

13]. Nearly a century later, scientists have searched for them repeatedly via meteorite analysis, particle accelerator experiments, cosmic ray detection and lunar rock examinations, yet no conclusive evidence has been found [

14,

15,

16]. Magnetism is a common, pervasive natural phenomenon. Clearly, if magnetic monopoles truly existed, their discovery should be relatively straightforward. Why, then, have they eluded capture to this day? This section unravels this century-old mystery.

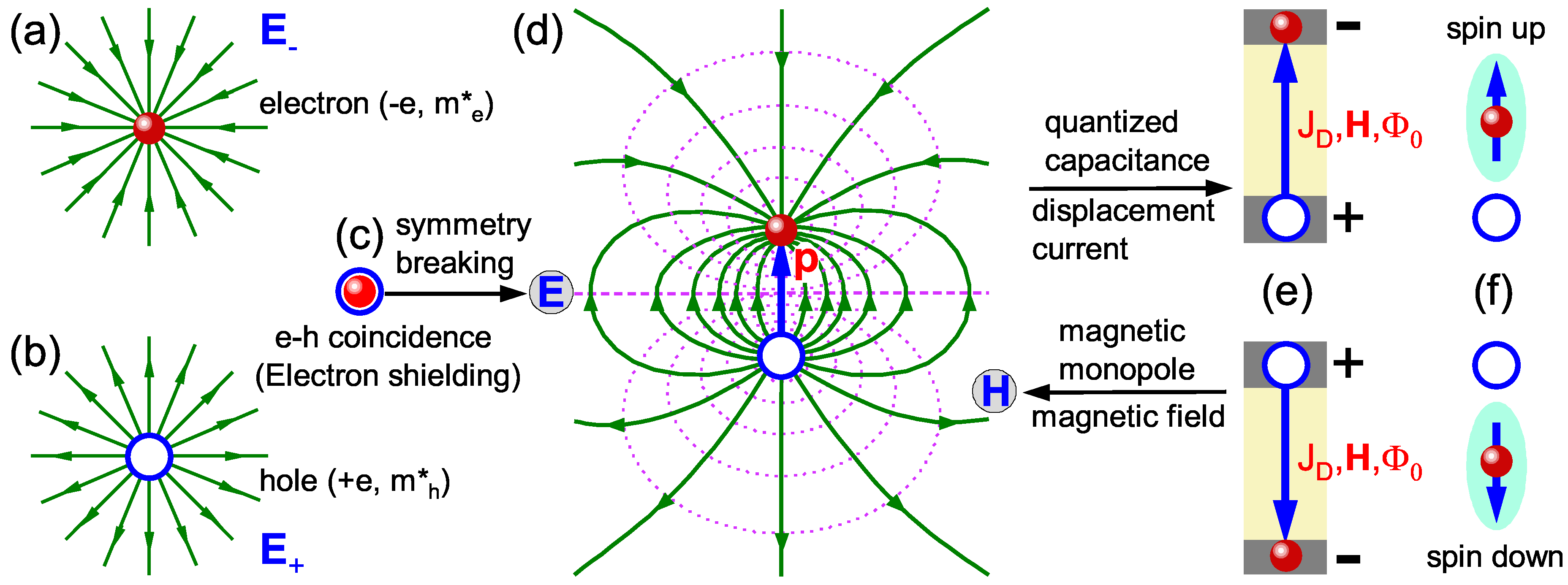

According to

Fig. 1, any material consists of two elementary components: electrons with negative charge and effective mass

(see

Fig. 2(a)), and holes with positive charge and effective mass

(see

Fig. 2(b)), each independently generating an electric field.

Fig. 2(c) shows that full overlap of electrons and holes leads to complete screening of electrons by holes. This makes the electron’s electronic, magnetic and other physical properties vanish. As shown in

Fig. 2(d), when the electron and hole separate, symmetry breaking occurs, leading to the emergence of various physical phenomena and quantities. The first to appear is the antidipole vector

and the corresponding electric field. In fact, the electron-hole pair is not only an electric dipole but also an important capacitor in electronic devices (see

Fig. 2(e)). Associated with the capacitor is the Maxwell displacement current, and the current generates a magnetic field and quantized magnetic flux

(where

represents the electron-hole pairing) [

17,

18]. Therefore, through simple logical reasoning, it is not difficult to conclude that the electron-hole pair actually generates a magnetic field, meaning that electrons and holes are the magnetic monopoles predicted by Dirac. Furthermore, since the hole is a quasiparticle, for convenience, the magnetic properties of the electron-hole dipole can be fully assigned to the electron. According to the direction of symmetry breaking, there are two electronic states with spin up and down:

[

19].

The scientific validity and self-consistency of the inferences in

Fig. 2 can be further verified by established theories and experimental facts. As Maxwell’s statement suggests, a changing electric field produces a magnetic field, which is given by

as follows:

where

is the speed of light and

is the vacuum permeability.

The formula reflects the dual transformation and symmetry between electric and magnetic fields, where the two are equivalent in status and share the same essence or physical origin—i.e., the electric dipole electric field is the magnetic field. Meanwhile, changes in electromagnetic field properties are manifested through the speed of light c, requiring no additional motion of electrons (translation, rotation, spin, etc.). This result can also be verified by Dirac’s magnetic monopole theory, which proposed that electric and magnetic charges could coexist and satisfy the following quantization condition [

13]:

where

e and

are the electric and magnetic charges, respectively,

is the Plank’s constant, and

being the integers.

To better illustrate the material nature of quantum, using the dimensionless fine-structure constant

, Eq. (

2) can be re-expressed as:

where

.

Eq. (

3) leads to a key conclusion: the so-called magnetic monopoles are in fact nothing but dressed electrons and holes. This implies that the magnetic monopoles sought for decades have finally been identified, and they are none other than the electrons we are most familiar with.

4. The Origin of Quantization, h or e?

In 1900, to resolve the “ultraviolet catastrophe” contradiction in black-body radiation, Planck boldly proposed a hypothesis: the energy of black-body radiation is not emitted or absorbed continuously, but in discrete quanta with

(where

) [

20]. While the Planck constant (

) can explain many quantum behaviors, its origin and essence remain an unsolved puzzle. Quantum field theory interprets it as the minimum action unit for field quantum fluctuations and particle interactions, yet we argue this is not the final answer. As a physical constant reflecting a universal phenomenon in the objective material world, the quantum constant must satisfy three conditions: (1) it must be an intrinsic property and possess materiality; (2) be related to electromagnetic interactions; (3) be associated with electromagnetic energy radiation. Results from Eq. (

3) have indicated that the only quantity meeting all three conditions and possessing intrinsic quantum nature is the elementary charge

.

The development of condensed matter physics has been accompanied by the emergence of numerous artificial concepts and quasiparticles, such as early ones including holes, spins, phonons, excitons, and magnetic monopoles, as well as current popular topological quasiparticles, Weyl fermions, Majorana fermions, and others. New quasiparticle concepts continue to be proposed relentlessly. In fact, these concepts or particles do not facilitate a better understanding of nature; instead, they trap scientific theories in a “metaphysical” predicament. Taking electron spin as an example, although it seemingly explains important experimental phenomena like magnetism, the essence of spin remains incompletely clarified to this day. This is essentially shifting the problem rather than solving it.The previous chapter has demonstrated that both magnetic monopoles and magnetism originate from the symmetry breaking of electron-hole pairs, and the quantized elementary charge plays a decisive role in quantum phenomena. This chapter will further clarify that the essence of all quantum phenomena lies in the quantization of charge. By replacing the Planck constant h (which lacks material properties) with the elementary charge e (which possesses materiality), almost all condensed matter physics problems can be satisfactorily explained.

Owing to the existence of the elementary charge

e, any macroscopic or microscopic charge

Q is inherently quantized, following

where

n is an integer (

). Since all known quantum-related physical phenomena are determined by the intrinsic properties of microscopic electrons (and other charged particles), it can be inferred that all quantum phenomena originate from charge quantization. Consequently, quantum phenomena should be scaled by the elementary charge

e rather than the Planck constant

h. Next, considering flux quantization, substituting the fine-structure constant

(in lieu of

h) into the relevant theoretical framework similarly yields:

where

.

Similar to the magnetic monopoles in Eq. (

3), the essence of flux quantization in Eq. (

4) is still charge quantization, which also constitutes the fundamental origin of the superconducting vortex state [

21]. By the same token, the conductance of the integer quantum Hall effect can also be expressed as:

where

. Furthermore, the electron spin can be re-expressed as:

The above equation indicates that spin is an inherent property of the electron’s charge, and there is no physical process to “split” an electron for the separation of charge from spin [

22]. Consequently, charge-spin separation does not truly exist. Furthermore, it must be emphasized here that both quantum flux and spin are generated by electron-hole pairs. Independent or free electrons do not possess intrinsic spin properties; therefore, the spin property of electrons can only be observed in atoms or crystalline materials. We know that modern physics proposes electron spin based on the atomic fine spectral structure and the Stern-Gerlach silver atomic beam experiment [

23]. These experiments also indicate that magnetic moments exist in atoms such as silver or hydrogen (i.e., electron-hole pairs), rather than in free electrons.

Based on the above discussion, quantum behaviors in the microscopic world are not mysterious. Phenomena such as electric fields, magnetic fields, electric currents, spin, magnetic flux, magnetic monopoles, and the quantum Hall effect are all determined by the elementary charge—the smallest charge in nature. These phenomena involve tiny electron displacements and the symmetry breaking of electron-hole pairs, with no other forms of electron motion involved. Since the measurement of electromagnetic signals relies on time-averaged accumulation, electron motion can blur and distort quantum information. To fully demonstrate quantum properties, experimental measurements must strive to obtain stable electromagnetic signals from individual electrons, thus requiring four conditions: (1) electrons are localized within the material; (2) an extremely low-temperature environment; (3) a low-dimensional electron system; and (4) weak external electromagnetic fields. Taking the quantum Hall effect as an example, in weak magnetic fields, the nearest-neighbor integer quantum Hall effect can be observed; in strong magnetic fields, however, the nearest-neighbor integer quantum behavior is disrupted, and electron signals from next-nearest neighbors and beyond form the fractional quantum effect.

5. The Symmetry of Maxwell’s Equations

Maxwell’s equations are elegant but not invariant under duality transformation. Is this asymmetry between electric and magnetic fields a true reflection of nature, or a consequence of our incomplete understanding of the electromagnetic field’s essence? Historically, many scientists have attempted to achieve the symmetry of Maxwell’s equations through mathematical means, including Dirac’s magnetic monopole hypothesis. This paper has demonstrated that magnetic monopoles are essentially electrons, and magnetic fields are generated by electron-hole pairs. Conduction current is no longer required for magnetic field production. Thus, the conditions for achieving the perfect symmetry of Maxwell’s equations are now fully satisfied.

Maxwell’s first equation

and the second equation

are completely independent of each other, so strictly speaking, the electromagnetic field is not unified. Here, we will show that the second equation can be derived from the first. For a electron-hole pair with coordinates

and

, and an inverse electric dipole moment vector

, substituting the electric fields excited by the electron and hole into Eq. (

1) yields:

Under a far-field approximation

, then

, Eq. (

7) means that the right-hand side of the second Maxwell’s equation is not exactly zero. Furthermore, our assumption has ruled out the presence of the conduction current (

). Thus far, we can now present the modified Maxwell’s equations:

Eq. (

8) has two breakthroughs: (1) the new first and second equations are linked, describing the electric and magnetic fields respectively; (2) the absence of conduction current leads to symmetry in the third and fourth equations. Based on the first and second equations of Eq. (

8), a crystal composed of electron-hole pairs can be regarded as an ultra-large-scale integrated capacitor. With the third and fourth equations, the current is interpreted as an electromagnetic wave. Consequently, the Josephson junction is a capacitor, and the Josephson effect is no longer the quantum tunneling of Cooper pairs but the lossless transmission of simple electromagnetic waves (displacement current) in a medium (the capacitor). The next section will investigate the current variation law of the Josephson effect.

6. The Microscopic Mechanism of the Josephson Effects

The Josephson effect is typically explained via wavefunction superposition and interference in the two superconductors [

1]. Notably, John Clarke et al. showed through experiments that it can be realized in macroscopic circuits [

6,

7,

8]. Here, we demonstrate that the microscopic Josephson effect is also circuit-related: it arises not from wavefunction superposition, but from the superposition of electron electrostatic fields and electromagnetic interactions induced by symmetry breaking of electronic states in the two superconductors due to the weak link.

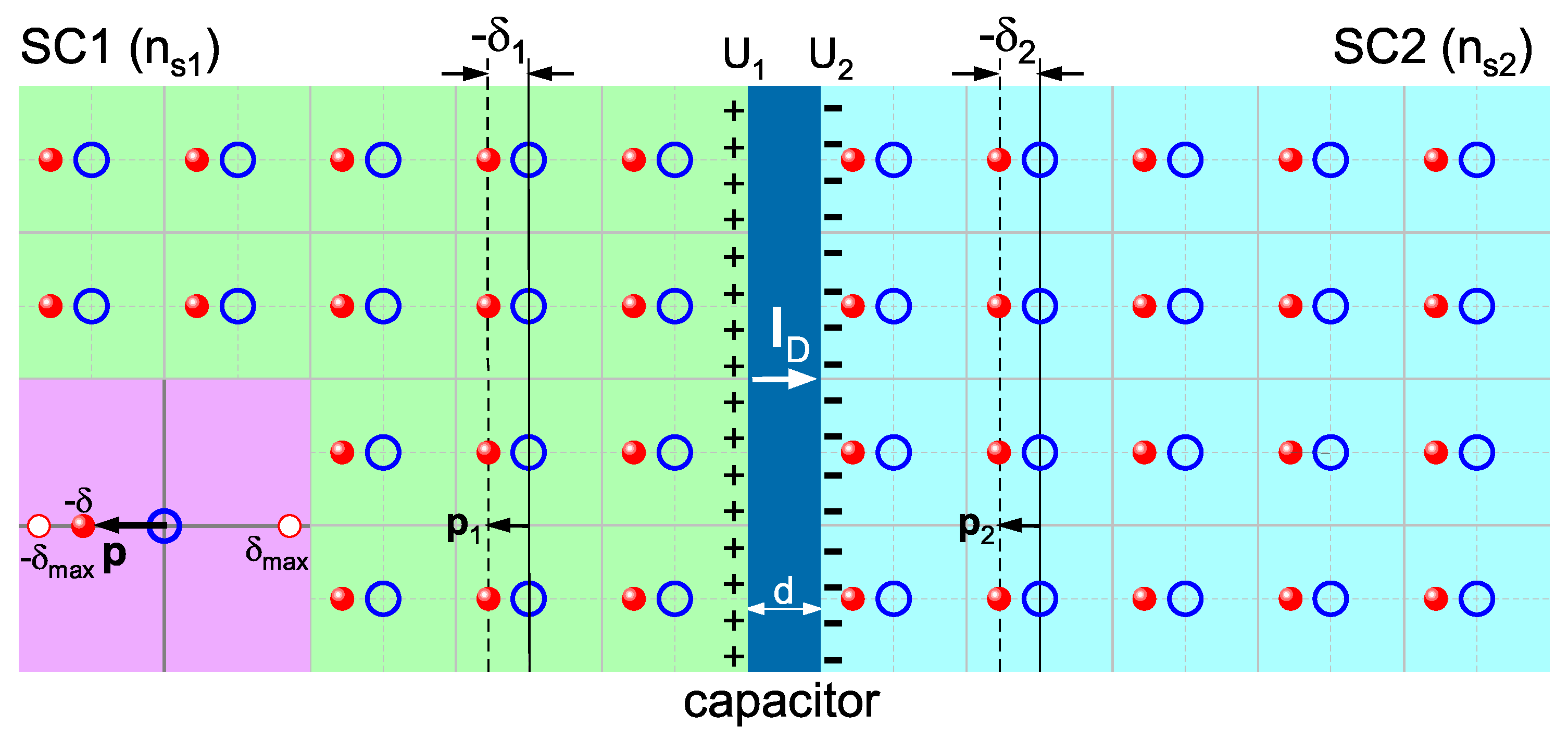

The ground state of the superconductor is a Mott insulator without symmetry breaking (see

Fig. 1(c)). As shown in

Fig. 3, when superconductor 1 (SC1) and superconductor 2 (SC2) are connected through a thin insulating layer, their electron densities are denoted as

and

respectively. In this case, the electronic electric fields in the two superconductors will penetrate the insulating layer and generate Coulomb repulsion, which further induces the symmetry breaking of the rigid Mott electronic state. Mathematically, this process can be described by the overall displacement of electrons in the superconductors. These displacements are marked as

(for SC1) and

(for SC2), and their magnitudes are proportional to the electron densities

and

of the two superconductors respectively. Such electron displacement inevitably gives rise to electric potentials

and

on both sides of the insulating layer. This phenomenon is equivalent to inducing opposite charges on the two surfaces of the insulating layer, which makes the insulating layer function like a parallel-plate capacitor. A displacement current

is thus generated across this capacitor-like structure.

As shown in the purple inset at the lower left of

Fig. 3, we assume for simplicity that SC1 and SC2 are made of the same material, so

and

. The physical effect induced by symmetry breaking can be described by the vector

. Since this is a typical harmonic oscillator problem in a central force field, the displacement

has a maximum value

. Even without vibration, the variation of

can be expressed as a static sine function:

where,

is called the phase difference, ranging from -

to

. It depends on properties such as the superconducting material and insulating layer thickness, determining the magnitude and direction of the electric dipole, as well as the induced potential and tunneling current.

The BCS theory wave function adopted by Josephson can be expressed as

. By comparing it with Eq. (

9), it is not difficult to find that the two are actually consistent. That is to say, the so-called superconducting wave function is merely the displacement variation of electron harmonic oscillation. This also explains why the BCS wave function can qualitatively describe experimental phenomena. Since the potentials

and

generated by the electric dipoles on the surface of the insulating layer are both proportional to the vector

, using Eq. (

9), the potential difference across the insulating layer satisfies the following relationship:

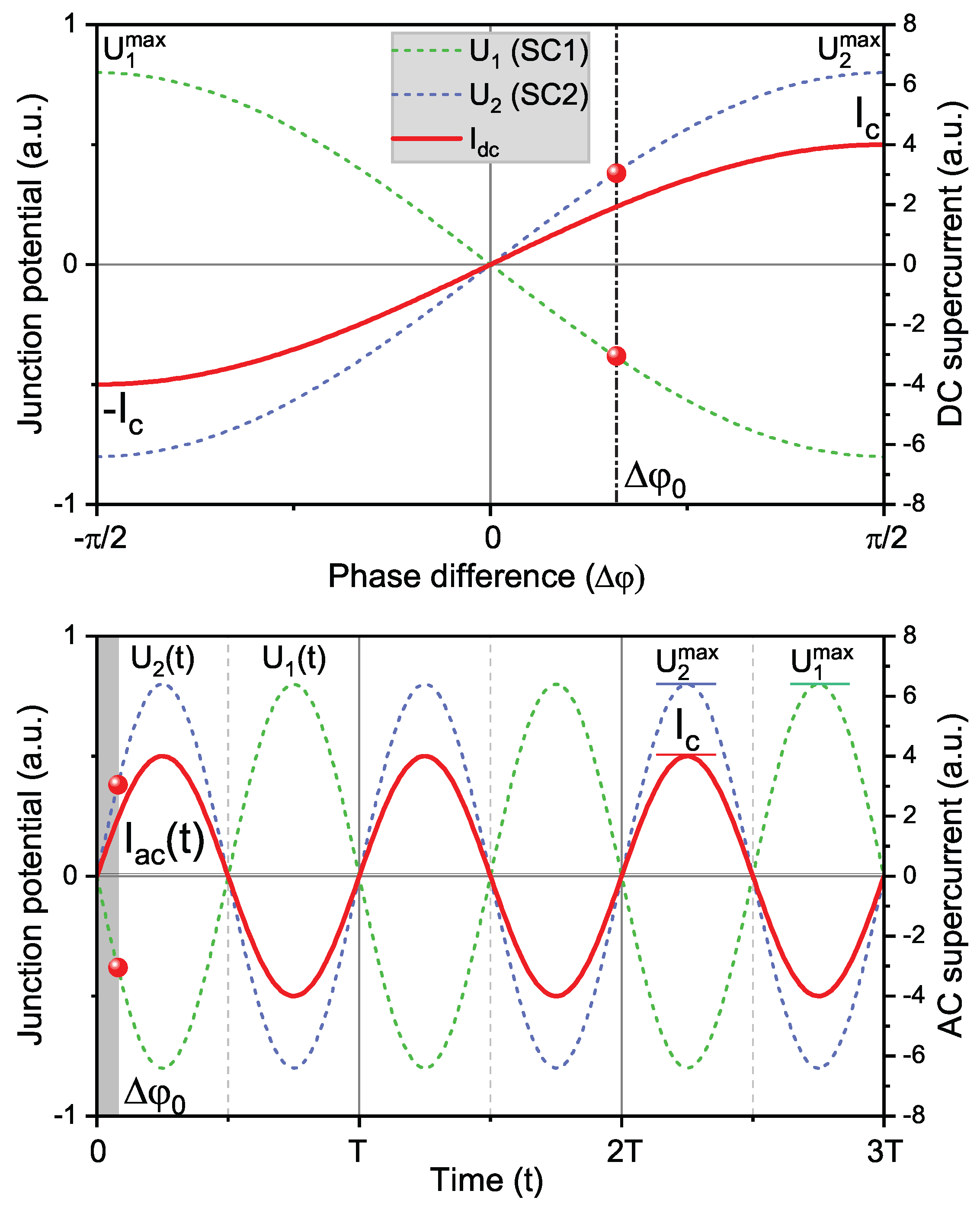

In the above equation,

corresponds to the maximum displacement of electron-hole pairs. Assuming the insulating layer has a resistivity

, area

, and thickness

d, as shown in

Fig. 4(a), the DC Josephson effect can be directly derived from Eq. (

10) as:

For insulators, although their resistivity

is very large, the extremely small thickness

d ensures that the critical

in Eq. (

11) is non-zero. This means that the DC Josephson current is essentially a displacement current, without the need for direct tunneling of Cooper pairs.

Instead, applying a direct current (DC) voltage across a Josephson junction induces an alternating superconducting current, and the traditional theory attributes this phenomenon to the phase evolution of the macroscopic quantum wavefunction. In our framework, the AC Josephson effect is simply a plasmon oscillation: superconducting electrons undergo simple harmonic oscillations around the equilibrium position (full overlap of electrons and holes) by absorbing external field energy and radiating electromagnetic energy. Its frequency

is uniquely determined by energy conservation. As is well-known, the harmonic oscillator energy satisfies the quantization relation:

From the above equation, the ground state energy (

) of the electron-hole dipole harmonic oscillator and the external electric field

V satisfy:

As shown in

Fig. 4(b), the electrons oscillation cause periodic variations in

and

, and the corresponding displacement current or AC Josephson current changes synchronously as:

Remarkably, the above derivation relies solely on basic electromagnetic principles, without involving any wavefunction or Cooper pair assumptions, yet it still yields results fully consistent with experiments. This further confirms that electric current does not require the directional movement of electrons or the quantum tunneling of Cooper pairs, and that both microscopic and macroscopic Josephson effects are circuit problems.

7. Concluding Remarks

Based on the validated superconductivity theory centered on the symmetry breaking of real-space localized electron-hole pairs, this study analytically resolves the long-standing puzzle of the Josephson effect from a classical dynamics perspective without invoking the assumption of wavefunction or Cooper pair tunneling. Specifically, the quantum-mechanically indeterminate long-range motion and tunneling of electron wavefunctions and Coulomb-repulsive Cooper pairs are replaced by the deterministic electromagnetic fields of electrons and the short-range displacement symmetry breaking of Coulomb-attractive electron-hole pairs. We propose a new quantum paradigm where the elementary charge e, which is endowed with intrinsic material and electromagnetic interaction properties as well as quantization (, ), replaces Planck’s constant h as the core quantum constant.

The key achievement of this research is the unification of physical concepts such as electric dipoles, capacitance, magnetic flux, displacement current, and magnetic monopoles, providing a self-consistent explanation for the physical origins of magnetic flux quantization, the quantum Hall effect, and the Josephson effect. The study clarifies that a Josephson junction is essentially a microcapacitor: the effect arises from symmetry breaking-induced opposite-sign charges (DC component) and externally driven charge oscillations (AC component). The analytically derived DC/AC Josephson current equations are in perfect agreement with experimental results, bridging classical electrodynamics and macroscopic quantum behaviors. Furthermore, it must be noted that the wavefunction of the BCS theory adopted by Josephson is not a true theoretical solution derived via the Schrödinger equation or quantum field theory methods. It is an artificial conjecture, essentially the plasmon vibration equation of the condensation of numerous harmonic oscillators. What truly tunnels through the Josephson junction is the electromagnetic field, not the wavefunction or Cooper pairs.

Furthermore, this research holds profound significance: (1) it confirms that the magnetic monopole is the electron, solving a century-old conundrum in the academic community; (2) it reveals that magnetism originates from the symmetry breaking of electron-hole pairs, independent of electron motion; (3) it achieves the mathematical perfect symmetry of Maxwell’s equations. These findings are expected to trigger a paradigm shift in fields such as condensed matter physics, electrodynamics, and quantum mechanics. By exploring the connection between the elementary charge and quantum phenomena, this study provides a more solid physical foundation for the development of quantum technologies and fundamental physics.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the supplementary.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

References

- B. D. Josephson. Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling. Physics Letters 1(7), 251–53 (1962). [CrossRef]

- P. W. Anderson, J. M. Rowell. Probable observation of the Josephson superconducting tunneling effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 10(6), 230–232 (1963). [CrossRef]

- S. Shapiro. Josephson currents in superconducting tunneling: The effect of microwaves and other observations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 11(2), 80 (1963). [CrossRef]

- R. L. Fagaly. Superconducting quantum interference device instruments and applications. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 77(10), 103101 (2006). [CrossRef]

- J. Bardeen, L. N. Cooper, J. R. Schrieffer. Microscopic theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 106, 162 (1957).

- J. M. Martinis, M. H. Devoret, J. Clarke. Energy-level quantization in the zero-voltage state of a current-biased Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55(15), 1543–1546 (1985). [CrossRef]

- M. H. Devoret, J. M. Martinis, J. Clarke. Measurements of macroscopic quantum tunneling out of the zero-voltage state of a current-biased Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55(18), 1908–1911 (1985). 10.1103/physrevlett.55.1908.

- J. M. Martinis, M. H. Devoret, J. Clarke. Experimental tests for the quantum behavior of a macroscopic degree of freedom: The phase difference across a Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. B 35(10), 4682 (1987). 10.1103/physrevb.35.4682.

- X. Huang. Visualized high-Tc superconducting mechanism of polyhedral quantum wells confined electrons. PREPRINT (Version 1), Research Square. (2024). [CrossRef]

- X. Huang. Planckian Quantization to Superconductivity: A Two-Step Path. Prepr. (2025). [CrossRef]

- N. F. Mott, R. Peierls. Discussion of the paper by de Boer and Verwey. Proc. Phys. Soc. Lond. 49(4s), 72 (1937). [CrossRef]

- V. L. Ginzburg, L. D. Landau. On the theory of superconductivity. Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 20, 1064 (1950).

- P. A. M. Dirac. Quantised singularities in the electromagnetic field. Proc. R. Soc. A 133, 60 (1931). [CrossRef]

- M. Chen. et al. A synthetic monopole source of Kalb-Ramond field in diamond. Science 375(6584), 1017–1020 (2022). [CrossRef]

- X. L. Qi, R. Li, J. Zang, S. C. Zhang. Inducing a magnetic monopole with topological surface states. Science 323(5918), 1184–1187 (2009). [CrossRef]

- C. Castelnovo, R. Moessner, S. L. Sondhi. Magnetic monopoles in spin ice. Nature 451(7174), 42–45 (2008). [CrossRef]

- B. Lischke. Direct observation of quantized magnetic flux in a superconducting hollow cylinder with an electron interferometer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 22(25), 1366-1368 (1969). [CrossRef]

- B. Deaver, W. Fairbank. Experimental evidence for quantized flux in superconducting cylinders. Phys. Rev. Lett. 7(2), 43 (1961). [CrossRef]

- G. E. Uhlenbeck, S. Goudsmit. Spinning electrons and the structure of spectra. Nature 117, 264–265 (1926).

- M. Planck. On the theory of the energy distribution law of the normal spectrum. Ann. Phys. 4(3), 553–563 (1901).

- A. A. Abrikosov. Type II superconductors and the vortex lattice. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 975 (2004).

- C. Kim, et al. Observation of Spin-Charge Separation in One-Dimensional SrCuO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 4054 (1996).

- J. Peter Toennies, et al. Otto Stern (1888–1969): The founding father of experimental atomic physics. Annalen der Physik 523(12), 1045–1070 (2011). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).