1. Introduction

Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) is a secreted pentameric glycoprotein (524 kDa) predominantly present in cartilage, but also expressed in other connective tissues such as tendon and skin [

1,

2,

3]. Functional studies have shown that COMP regulates collagen fibrillogenesis, contributes to ECM organisation, and can modulate growth factor signalling [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Structurally, COMP consists of an N-terminal coiled-coil domain, four epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains, eight calcium binding type 3 repeats (T3) and a C-terminal domain which acts as a site of collagen binding [

5,

9].

Mutations in COMP lead to two different, but clinically related, rare skeletal dysplasias; pseudoachondroplasia (PSACH) and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia (MED) [

10,

11]. The majority of

COMP mutations are located in the T3 repeats, including the p.D469del mutation, which is found in approximately 30% of all PSACH cases [

12], but is not seen in MED. Notably, PSACH is caused exclusively by mutations in

COMP, whereas autosomal-dominant forms of MED can also be caused by mutations in matrilin-3 (

MATN3) and type IX collagen (

COL9A1, COL9A2, COL9A3) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], other constituents of the cartilage ECM that have all been shown to interact directly with COMP [

5,

7,

18].

In PSACH-MED mutant COMP and mutant matrilin-3 are retained within the chondrocyte endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [

19,

20,

21], triggering ER-stress. Indeed, induction of ER-stress alone is sufficient to induce a chondrodysplasia-like phenotype [

24,

25] in mice. Interestingly, previous studies identified three MED-causing COMP variants that have been described to exhibit incomplete mutant protein retention [

22,

23].

To restore ER homeostasis, in response to ER stress, and allow the survival of the cell, the unfolded protein response (UPR) drives a global reduction in protein translation and synthesis whilst enhancing the folding capacity of the ER by increasing chaperone protein and foldase levels (extensively reviewed in [

26,

27]). Despite initially acting as a pro-survival mechanism, persistent ER-stress and continuous activation of all three branches of the UPR (controlled by IRE1, PERK and ATF6) can induce apoptosis. In contrast to mutations in

MATN3, in which activation of the UPR has been unequivocally demonstrated in cell and mouse models [

20,

28,

29], the role of the UPR for mutations in

COMP is less clear [

30,

31,

32]. Most studies to date have focused on the relatively common p.D469del COMP mutation and have proposed that inflammation and oxidative stress play a bigger role than the UPR [

30,

32,

33].

Drug repurposing has emerged as a promising approach to treat skeletal diseases, which are often individually rare. For metaphyseal chondrodysplasia type Schmid (MCDS), caused by mutations in type X collagen, the identification of the UPR as a therapeutic target has driven the development of novel treatment strategies [

34,

35] and the repurposed drug carbamazepine (CBZ) has been tested in a clinical trial for children with MCDS [

34]. Unfortunately, CBZ was unable to reduce the activation of the UPR following mutant matrilin-3 expression in cell models [

36], highlighting the importance of appropriate model systems and drug screening strategies for distinct skeletal dysplasias. A recent study has shown that with the use of an ER-stress reporter in which an ER-stress response element drives luciferase expression, curcumin was successful at reducing ER-stress caused by mutant matrilin-3 accumulation by stimulating its degradation [

37]. This discovery highlights that in order to facilitate large-scale drug screenings

in vitro, biomarkers are required that allow the efficient evaluation of compounds.

In this study, we aimed to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying COMPopathies using our in vitro model system in order to find a biomarker that could then be used to support drug repurposing/development. We demonstrate that MMP9 expression is specifically upregulated in PSCAH and MED cell models of COMPopathies and that, in contrast, MED causing mutant matrilin-3 does not affect MMP9 expression. MMP9 could therefore be used as a readout when screening for drugs to correct the molecular defect that occurs in COMPopathies.

2. Results

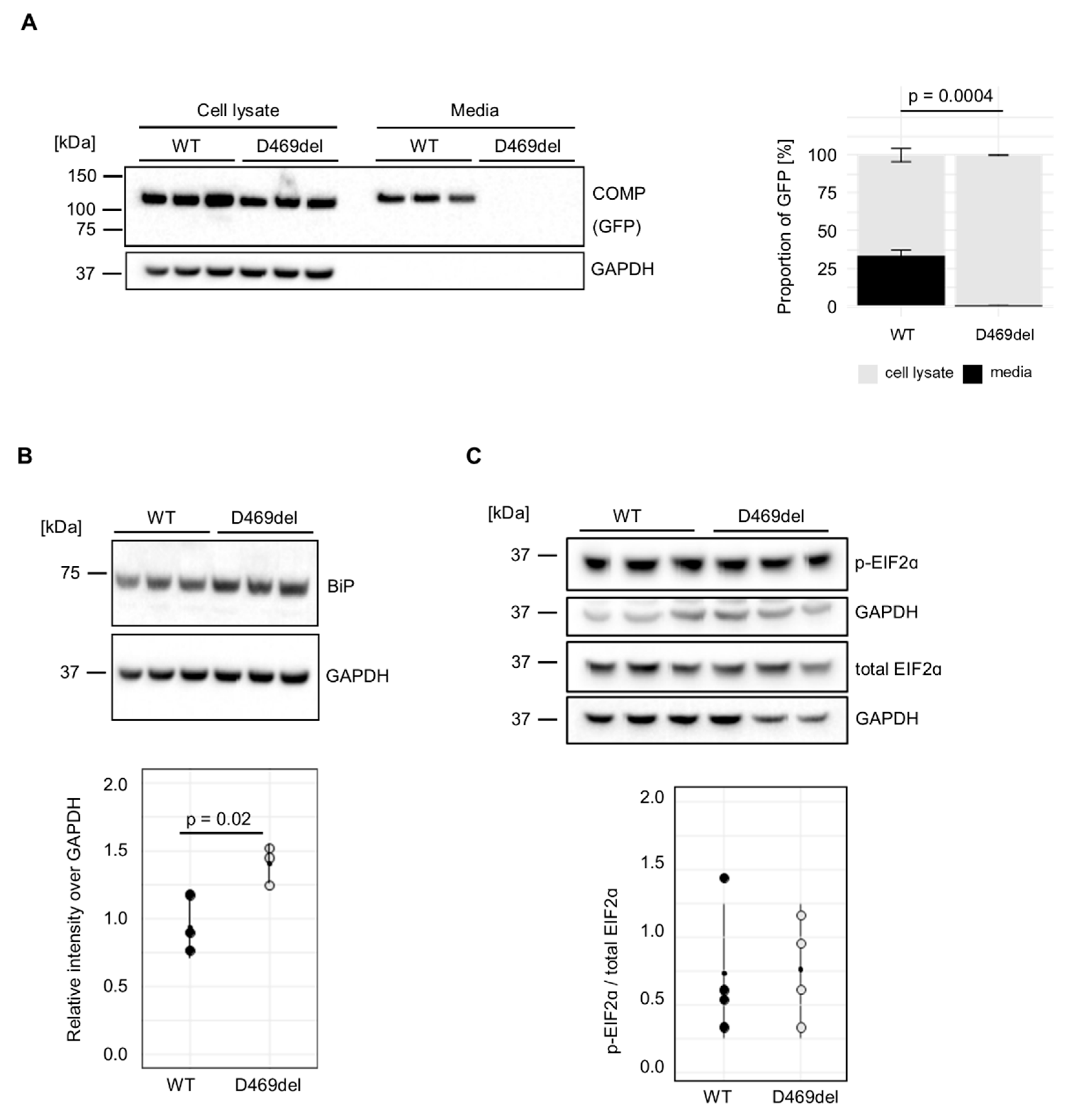

2.1. D469del COMP HT1080 Cells Are an In Vitro Model of COMPopathy

We have previously reported that GFP-tagged p.D469del COMP is retained intracellularly when expressed recombinantly in HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells, in contrast to GFP-tagged wild-type (WT) COMP [

32]. In agreement with our previous report, COMP was equally detected in the cell lysates of both wild type (WT) and p.D469del GFP-tagged COMP overexpressing cells (

Figure 1A). When extracellular COMP levels were evaluated, WT COMP was readily detected in conditioned media, whereas p.D469del COMP was totally absent, (

Figure 1A). In the murine growth plate, the intracellular accumulation of p.D469del COMP disrupts chondrocyte proliferation and both increases and dysregulates apoptosis without triggering a conventional UPR [

32]. In order to investigate if the UPR is triggered when overexpressing pD469del COMP in human cells, markers of the three UPR branches were examined. When analysed by western blotting the levels of the chaperone BiP, the master regulator of the UPR, were slightly, but significantly, increased in the p.D469del COMP cell model (

Figure 1B), whilst phosphorylation of the UPR PERK-effector eiF2α was not affected by p.D469del COMP (

Figure 1C). Calnexin levels were also mildly elevated (

Figure S1A), whilst

XBP1 splicing, which is induced by IRE1/ERN1 during activation of the UPR, was reduced in p.D469del COMP cells (

Figure S1B). Despite no prominent activation of UPR signalling, levels of apoptosis were significantly increased (8.5 ± 0.2 % vs 4.0 ± 0.8 %) in p.D469del COMP cells as demonstrated by TUNEL staining (

Figure S1C). Together, these findings replicate previous observations seen in mouse models of human COMPopathies [

32,

33] and thus demonstrate that cells overexpressing p.D469del COMP mimic the major aspects of PSACH pathology

in vitro.

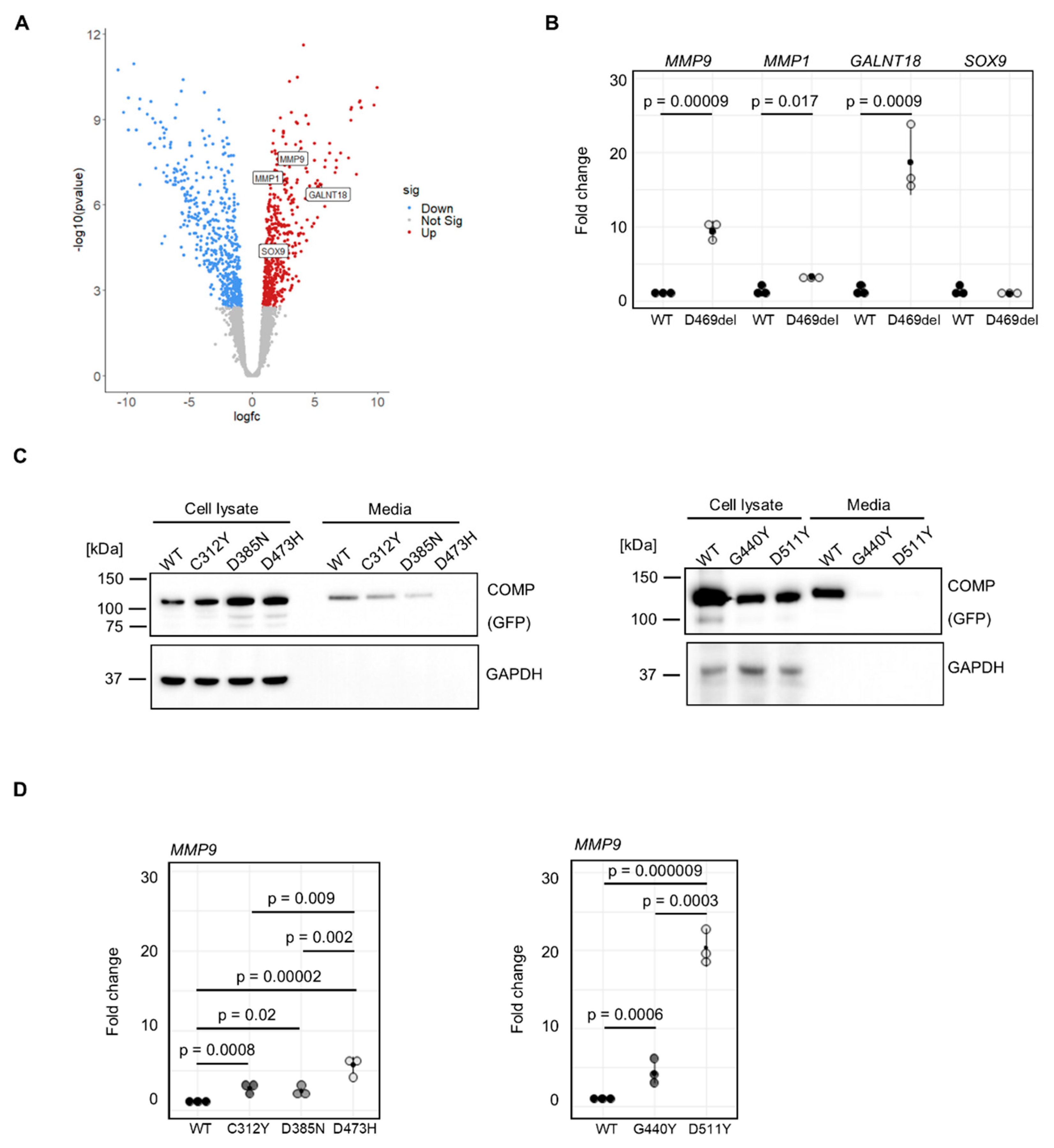

2.2. Transcriptomic Analysis of COMPopathy Cell Model

We aimed to employ our

in vitro model system to identify potential biomarkers and or gene signatures that are specific to COMPopathy and not present in skeletal dysplasias caused by other ECM proteins. Therefore, mRNA sequencing was performed on p.D469del and WT COMP cells. Out of the total of 12487 genes expressed in these cells (transcripts per million (TPM) > 2), 465 genes were upregulated and 524 were downregulated with a false discovery rate of < 0.05 and a fold change > 1.5 (

Supp. Table 1). KEGG pathway analysis was performed on all differentially expressed genes and revealed dysregulated cytokine signalling, including tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-17 pathways; regulation of TRP channels by inflammatory mediators, and complement and coagulation cascades. ECM-receptor interaction, focal adhesion, organisation of actin cytoskeleton and cellular senescence were also amongst significantly enriched KEGG pathways (

Table 1). To validate our mRNA sequencing, qRT-PCR was performed including

MMP9 and

MMP1 encoding matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that function to breakdown the cartilage matrix,

GALNT18 that has recently been implicated in ER homeostasis [

41] and

SOX9 encoding a transcription factor that is an established regulator of chondrogenesis [

42] (

Figure 2A & 2B). Interestingly, elevated MMP activity was demonstrated in an inducible mouse model of COMP [

38]. Furthermore, their expression and activity is known to be exacerbated in inflammatory signalling that has previously been suggested to play a role in the pathology of COMPopathies. [

39,

40]. In agreement with RNA sequencing findings, qRT-PCR confirmed that

MMP9, MMP1 and

GALNT18 were significantly upregulated in D469del COMP cells (9.4-, 3.3- and 18.7-fold, respectively); in contrast,

SOX9 expression was not changed. (

Figure 2A). Our data therefore demonstrate that, similar to observations made in PSACH mouse models, p.D469del COMP cells display dysregulated cytokine signalling that could be responsible for a more inflammatory response than the classical ER-stress mediated UPR.

2.3. MMP9 Is Upregulated in Multiple COMPopathy Cell Models

The p.D469del mutation in COMP is responsible for approximately 30 % of PSACH cases [

12] and is therefore often used to study the molecular mechanisms underlying COMPopathies caused by mutations within the T3 repeats of COMP. Other mutations in these repeats, causing either PSACH or MED, remain less well characterised. We therefore analysed a selection of disease-causing COMP missense mutations to determine if they had a similar effect on MMPs: the MED p.C312Y and p.D385N mutations and the PSACH mutations p.D473H (that is located within the same sequence of five aspartic acid residues as p.D469), p.G440R and p.D511Y.[

12,

43]. When COMP protein levels were examined by western blotting the amount of extracellular COMP was significantly reduced by all PSACH-causing mutations and the MED-causing p.D385N mutation, but not by p.C312Y (

Figure 2B,

Figure S2A). Unlike the findings from the p.D469del COMP, none of the selected mutations resulted in elevated levels of BiP or calnexin (

Figure S2B, C). We then investigated the effect of these mutations on

MMP9 expression using qRT-PCR (

Figure 2C). Overexpression of all selected mutations resulted in an upregulation of

MMP9 expression. Strikingly, we did not only observe a significant difference between wild type and mutant COMP-overexpressing cells, but also a mutation-dependent increase in

MMP9 expression. The MED-causing COMP mutations p.C312Y and p.D385N led to 2.8- and 2.4-fold elevated

MMP9 expression respectively, whilst for the PSACH-causing mutations p.D473H, p.G440R and p.D511Y,

MMP9 expression was elevated 5.7-, 4.3- and 20.4-fold, respectively. This also resulted in enhanced MMP9 activity in conditioned media of p.C312Y, p.D385N and p.D473H and p.D511Y COMP cells, with a tendency for increased MMP9 activity in p.G440R COMP expressing cells (

Figure S3A).

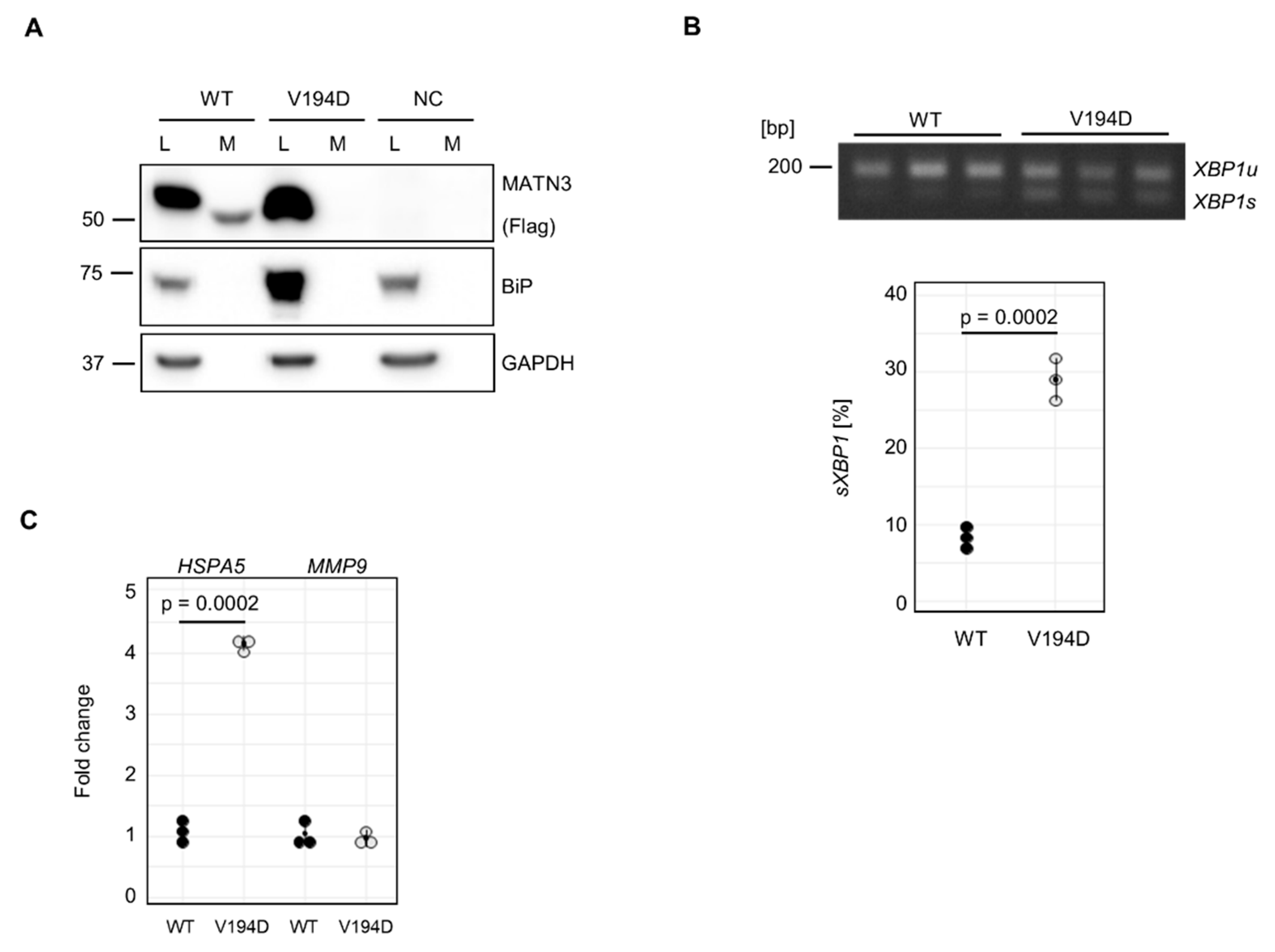

2.4. A Disease-Causing Matrilin-3 Mutation Does Not Cause Increased MMP9 Expression

Having demonstrated that

MMP9 expression is elevated in several

in vitro models of COMPopathies, we next asked whether

MMP9 expression is altered in a model of another, closely related, skeletal dysplasia. To address this, we transiently overexpressed FLAG-tagged wild type (WT) and mutant (p.V194D) matrilin-3 in HT1080 cells. The p.V194D variant of matrilin-3 is a typical MED-causing mutation and has been extensively characterised using both mouse and cell models [

28,

29,

36]. In contrast to mutant COMP, p.V194D matrilin-3 has been demonstrated to activate a typical UPR in response to ER-stress, both

in vivo and

in vitro.

When evaluated by western blotting, WT matrilin-3 was present in cell lysates as well as conditioned media of transfected cells, whilst mutant p.V194D (VD) matrilin-3 was absent from conditioned media (

Figure 3A). In untransfected cells (negative control, NC), no FLAG-tagged protein was observed in either cell lysate or conditioned media (

Figure 3A). Consistent with previous reports, expression of mutant p.V194D matrilin-3 resulted in a significant increase in BiP protein levels compared to WT matrilin-3 and untransfected cells (

Figure 3A).

XBP1 splicing was also assessed to confirm activation of the IRE1 branch of the UPR (

Figure 3B). In agreement with previous findings,

XBP1 splicing was significantly increased in mutant p.V194D compared to WT matrilin-3 (

Figure 3B).

The increase of BiP protein levels was reflected in a significant upregulation of

HSPA5, the gene that encodes BiP (

Figure 3C). Thus, our model system appeared to reliably mimic previously described features of

MATN3-MED pathology. When we examined

MMP9 expression we did not observe any changes (

Figure 3C) compared to WT MATN3-Flag expressing cells; therefore, suggesting that

MMP9 is specifically elevated in response to mutant COMP, but not mutant matrilin-3.

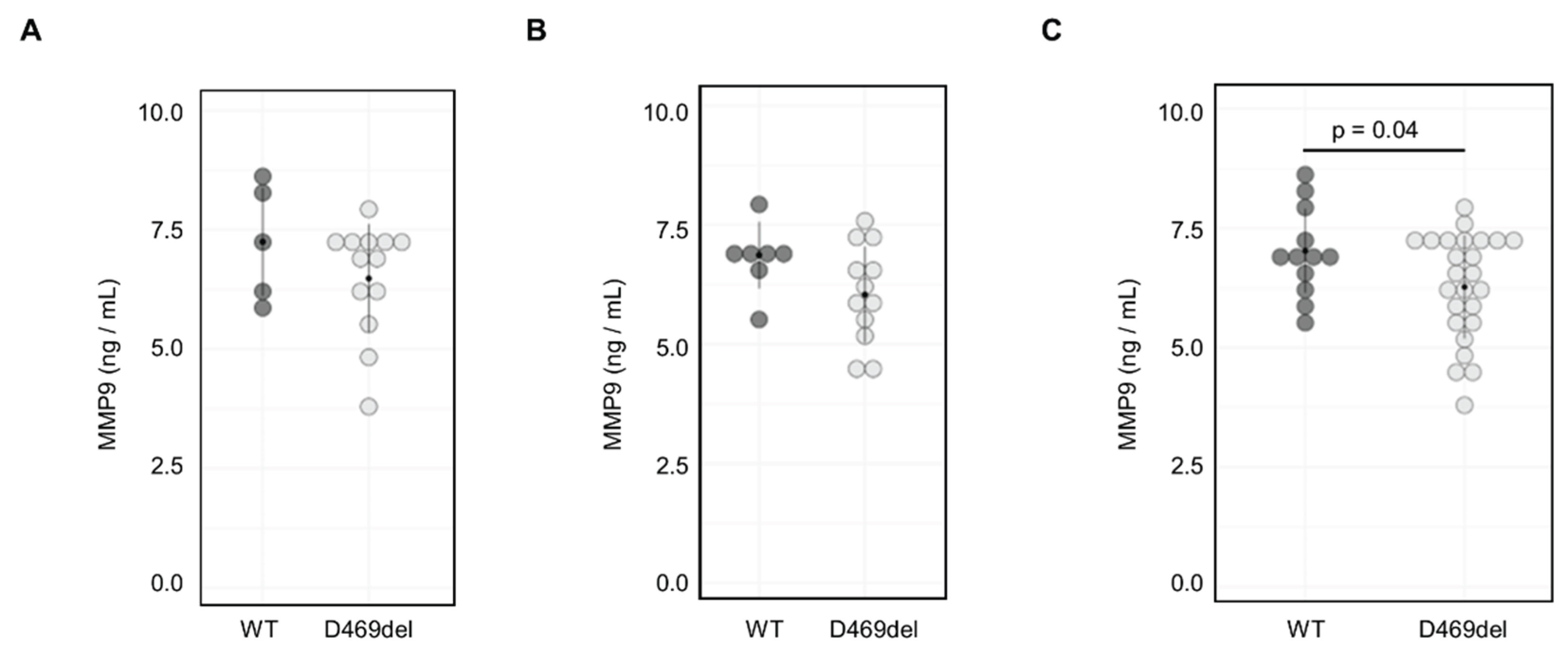

2.5. MMP9 Serum Levels in D469del COMP PSACH Mouse Model Are Not Altered

We next aimed to determine whether MMP9 levels were elevated in serum from a PSACH knock-in mouse model with the p.D469del COMP mutation [

32]. However, there were no significant sex differences in MMP9 serum levels from either genotype (

Figure S3B, C) and in contrast to our findings

in vitro, we did not detect a significant increase in MMP9 serum levels from either female or male mice (

Figure 4A and B). Indeed, when data from both sexes were combined, MMP9 levels were significantly decreased (mean ng/ml in WT and Y ng/ml in D469del) in the D469del COMP PSACH mouse model (

Figure 4C).

3. Discussion

Skeletal dysplasias are individually rare diseases; however, together they affect approximately one in 4000 people. The characterisation of disease mechanisms, and the identification of ER-stress as a crucial component have driven the development of novel treatment approaches. Never-the-less, to perform large-scale drug screenings suitable (bio)markers need to be available.

In contrast to mutations in COL10A1 and MATN3, the UPR pathways appear to be largely unaffected by the retention of mutant COMP in the ER in animal models of MED and PSACH causing COMP mutations(ref). Herein we demonstrate the absence of pronounced activation of the UPR in human cells overexpressing the the archetypal p.D469del COMP mutation as well as for several missense mutations, which renders components of the UPR unsuitable as biomarkers for COMPopathies.

The specific reason why mutant matrilin-3 and type X collagen but not COMP trigger the UPR remains to be elucidated in future studies. Similar findings have been reported for mutations in

COL1A1 and

COL1A2 that cause osteogenesis imperfecta, and whilst some mutations trigger the UPR, others do not [

44,

45]. It is tempting to speculate that for collagens, the location of the mutation is crucial, and that mutations in the pro-peptide of type I collagen trigger increased binding of chaperones such as BiP, whilst mutations in the triple-helical region do not. Why mutant COMP would not be recognised by chaperones in the same way as matrilin-3 or various collagens remains to be investigated.

Our study used transcriptomic analysis and multiple mutant COMP variants to discover potential biomarkers of COMPopathies. Our reported upregulation of

MMP9 in COMPopathy cell models compliments previous observations from mouse models, which have described a more inflammation-mediated disease mechanism and generally elevated MMP activity [

32,

33,

38]. In agreement with this, MMP9 expression has been described to be stimulated in chondrocytes and synoviocytes by the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNFα [

46]. However, we found MMP9 serum levels in D469del COMP PSACH mice to be reduced compared to WT mice rather than elevated. This discrepancy could be caused by several factors. MMP9 levels may be increased locally, but this may not be detectable in serum. Since some cartilage matrix molecules have a long half-life and most cartilage is actively built and remodelled during the growth period, it is also possible that the physiological expression levels of p.D469del COMP do not stimulate MMP9 expression in young adult mice. Additionally, other mechanisms that control MMP9 levels may interfere with or even counteract the stimulation of MMP9 expression by mutant COMP accumulation

in vivo.

In the absence of a complete understanding of the disease mechanism, the ability to perform drug screenings of large compound libraries remains ever more important. Our work demonstrates that several MED/PSACH-causing COMP mutations result in increased MMP9 expression. Increased MMP9 expression was even observed in cells expressing the p.C312Y COMP mutation which did not affect COMP secretion significantly. Importantly, MMP9 expression was unaffected by expression of MED causing p.V194D matrilin-3 mutation. suggesting it is specifically differentially regulated in cell models of COMPopathies. Since MMP9 is known to be involved in inflammatory processes, it is our hope that our findings will lead to the discovery of compounds that can reduce inflammation and improve chondrocyte pathology in COMPopathies. Since PSACH and MED are rare diseases, and resources are often limited, our work suggests that MMP9 expression could act as a suitable RNA biomarker for compound screenings independently of the specific COMP mutation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Generation and Culture of Wild Type and Mutant COMP Cell Lines

FACS-sorted pEGFP-N3 hCOMP wild type (WT) and p.D469del COMP HT1080 cells have been described previously [

32]. HT1080 cells were obtained from ATCC (ATCC, Manassas, VA USA; ATCC CCL0121). All other constructs (p.C312Y, p.D385N, p.D473H, p.G440R and p.D511Y) were generated using pEGFP-N3 hCOMP construct as template, primers containing the desired mutations (see

Supplementary Table 1) and the QuikChange Site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies UK Ltd., Edinburgh, UK) according to manufacturer’s instructions. HT1080 cells were maintained, transfected and selected as described previously [

32].

4.2. SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

Cell lysates and conditioned media were collected 72 h after confluency. Conditioned medium was collected and briefly centrifuged to remove debris before 5 x SDS loading buffer (625 mM Tris-base, 50 % (v/v) Glycerol, 10 % (w/v) SDS, 0.025 (w/v) Bromophenol blue pH 6.8) was added. Cell layers were washed with sterile PBS and scraped in 2 X SDS loading buffer containing protease inhibitors (F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, Basel, Switzerland). Lysates were passed through an insulin-syringe and centrifuged for 10 min at 13 000 x g at 4 degrees. DTT was added to lysates and conditioned media before samples were boiled. Samples were loaded onto a pre-cast Novex NuPAGE 4-12 % Bis-Tris gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MS, USA) and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was stained with Ponceau staining solution for 2 min and, after imaging, blocked in 3 % BSA/TBS-T for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Incubation with primary antibody was carried out overnight at 4ºC in blocking solution using the appropriate dilution (see

Supplementary Table 2). Incubation with secondary antibody was carried out for 1h at RT in 5 % skimmed milk/TBS-T. Proteins of interest were detected using SuperSignal West Pico Plus Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Band intensities were quantified in ImageJ/Fiji (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) using GAPDH as loading control.

4.3. TUNEL Assay

Apoptosis was analysed using DeadEnd fluorometric TUNEL assay (Promega, Southampton, UK) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Nuclei were stained with Fluoroshield mounting medium with DAPI (Abcam, Cambridge, UK).

4.4. RNA Sequencing

RNA was isolated from p.D469del and WT COMP cells using the EZNA DNA/RNA extraction kit (Omega Bio-tek, Inc, Norcross, GA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions before purified RNA was treated with DNA-free kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc) to remove DNA contamination.

RNA sequencing was performed by the Genomic Core Facility at Newcastle University using the NextSeq500 platform. Transcriptome analysis was then performed as described previously [

47] using hg38 as reference, and with genes exhibiting a log

2 fold change larger than +/- 0.58 (= 1.5-fold change) and adjusted

p-value smaller than 0.05 considered significantly differentially expressed. KEGG pathway analysis was carried out using the Enrichr tool [

48].

4.5. Gene Expression Analysis by qRT-PCR

RNA was extracted from cells using the ReliaPrep RNA Mini prep kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 1 µg of RNA was transcribed into cDNA using the GoScript RT kit (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions. After cDNA synthesis, samples were treated with 1 U RNaseH (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) for 20 min at 37ºC. Gene expression was measured using PowerUp SYBR green master mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) according to manufacturer’s instructions using the primers specified below (see

Supplementary Table 4).

For XBP1 splicing analysis, BioMix Red master mix (Bioline Reagents Ltd, London, UK) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Long and short form of XBP1 transcript were visualised using agarose gel electrophoresis.

4.6. In-Gel Zymography

1 mL of serum-free cell culture supernatant was concentrated to 25 µL using VivaSpin columns (Sigma Aldrich Ltd, Haverhill, UK) with a molecular weight cut-off of 10 kDa for 10 min at 12 000 x g. The concentrated sample was then mixed with the appropriate amount of 5 x SDS loading buffer (without DTT) and incubated for 10 min at RT. Non-reducing SDS-PAGE was performed on ice using 7.5 % SDS polyacrylamide gels containing 0.3 % gelatine. After washing in 0.25 % Triton-X100, the zymogram was incubated overnight at 37ºC and 60 rpm in digestion buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM CaCl2, 0.2 % NaN3). The reaction was stopped by staining the zymogram in Coomassie staining solution (40 % Methanol, 10 % acetic acid, 0.2 % Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250) for 60 min. An identical gel without gelatine was run in parallel, stained with Coomassie solution and band intensities used as loading control.

4.7. Serum MMP9 ELISA

Blood samples were extracted from 8 week old unfastened wild-type and p.D469del mutant COMP mice (described in detail in [

32]) by terminal cardiac puncture under anaesthesia. Briefly, blood was drawn from the left ventricle using a 25G needle and 1 mL syringe and transferred directly into a BD Microtainer

TM serum separator tube containing anti-coagulant. Whole blood was allowed to clot for 30 min at room temperature before being centrifuged at 1500 x g, 4ºC for 20 min. The level of MMP9 in the resulting serum was then deduced using the R&D Systems Mouse Total MMP9 Quantikine ELISA kit (Biotechne Ltd. Abingdon, UK) according to manufacturer’s instructions. All

in vivo work was carried out under project license PPL60/4525 in compliance with the Animals Scientific Procedures Act (ASPA) 1986 according to Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in R studio using either unpaired two-tailed student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc test (for multiple groups). For gene expression analysis, fold changes were first converted into log2 fold changes prior to statistical analysis. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

KP, LR, DY and MB designed the study. HD, EPD, BG, LR, DY and MB designed experiments. HD, EPD, FJSB and BG conducted experiments and acquired data. HD, EPD, BG, LR, DY and MB analysed and interpreted the data. LR, DY and MB provided reagents. HD, EPD, LR, DY and MB wrote and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the EU Horizon 2020 under grant agreement number 754825 (MCDS-Therapy project) and the Medical Research Council (MR/X001873/1).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Animal protocols were carried out under UK Home Office Project license PP8481100 and Newcastle University local ethical approval was provided under The Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (ASPA) 1986. This approval is granted from 15th June 2023 until 14th June 2028.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Dan J Hayman for technical support with in-gel zymography. We would also like to thank the Genomics Core Facility and the BioImaging Unit at Newcastle University for their excellent technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Dodge GR, Hawkins D, Boesler E, Sakai L, Jimenez SA. Production of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) by cultured human dermal and synovial fibroblasts. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1998 Nov;6(6):435–40. [CrossRef]

- Hedbom E, Antonsson P, Hjerpe A, Aeschlimann D, Paulsson M, Rosa-Pimentel E, et al. Cartilage matrix proteins. An acidic oligomeric protein (COMP) detected only in cartilage. J Biol Chem. 1992 Mar 25;267(9):6132–6. [CrossRef]

- Smith RKW, Zunino L, Webbon PM, Heinegård D. The distribution of Cartilage Oligomeric Matrix Protein (COMP) in tendon and its variation with tendon site, age and load. Matrix Biology. 1997 Nov 1;16(5):255–71. [CrossRef]

- Haudenschild DR, Hong E, Yik JHN, Chromy B, Mörgelin M, Snow KD, et al. Enhanced activity of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) bound to cartilage oligomeric matrix protein. J Biol Chem. 2011 Dec 16;286(50):43250–8. [CrossRef]

- Holden P, Meadows RS, Chapman KL, Grant ME, Kadler KE, Briggs MD. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein interacts with type IX collagen, and disruptions to these interactions identify a pathogenetic mechanism in a bone dysplasia family. J Biol Chem. 2001 Feb 23;276(8):6046–55. [CrossRef]

- Ishida K, Acharya C, Christiansen BA, Yik JHN, DiCesare PE, Haudenschild DR. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein enhances osteogenesis by directly binding and activating bone morphogenetic protein-2. Bone. 2013 Jul;55(1):23–35. [CrossRef]

- Mann HH, Ozbek S, Engel J, Paulsson M, Wagener R. Interactions between the cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and matrilins. Implications for matrix assembly and the pathogenesis of chondrodysplasias. J Biol Chem. 2004 Jun 11;279(24):25294–8. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg K, Olsson H, Mörgelin M, Heinegård D. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein shows high affinity zinc-dependent interaction with triple helical collagen. J Biol Chem. 1998 Aug 7;273(32):20397–403. [CrossRef]

- Hansen U, Platz N, Becker A, Bruckner P, Paulsson M, Zaucke F. A secreted variant of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein carrying a chondrodysplasia-causing mutation (p.H587R) disrupts collagen fibrillogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Jan;63(1):159–67. [CrossRef]

- Briggs MD, Hoffman SM, King LM, Olsen AS, Mohrenweiser H, Leroy JG, et al. Pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia due to mutations in the cartilage oligomeric matrix protein gene. Nat Genet. 1995 Jul;10(3):330–6. [CrossRef]

- Hecht JT, Nelson LD, Crowder E, Wang Y, Elder FF, Harrison WR, et al. Mutations in exon 17B of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) cause pseudoachondroplasia. Nat Genet. 1995 Jul;10(3):325–9. [CrossRef]

- Briggs MD, Brock J, Ramsden SC, Bell PA. Genotype to phenotype correlations in cartilage oligomeric matrix protein associated chondrodysplasias. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014 Nov;22(11):1278–82. [CrossRef]

- Bönnemann CG, Cox GF, Shapiro F, Wu JJ, Feener CA, Thompson TG, et al. A mutation in the alpha 3 chain of type IX collagen causes autosomal dominant multiple epiphyseal dysplasia with mild myopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Feb 1;97(3):1212–7. [CrossRef]

- Chapman KL, Mortier GR, Chapman K, Loughlin J, Grant ME, Briggs MD. Mutations in the region encoding the von Willebrand factor A domain of matrilin-3 are associated with multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Nat Genet. 2001 Aug;28(4):393–6. [CrossRef]

- Czarny-Ratajczak M, Lohiniva J, Rogala P, Kozlowski K, Perälä M, Carter L, et al. A mutation in COL9A1 causes multiple epiphyseal dysplasia: further evidence for locus heterogeneity. Am J Hum Genet. 2001 Nov;69(5):969–80.

- Muragaki Y, Mariman EC, van Beersum SE, Perälä M, van Mourik JB, Warman ML, et al. A mutation in the gene encoding the alpha 2 chain of the fibril-associated collagen IX, COL9A2, causes multiple epiphyseal dysplasia (EDM2). Nat Genet. 1996 Jan;12(1):103–5. [CrossRef]

- Paassilta P, Lohiniva J, Annunen S, Bonaventure J, Le Merrer M, Pai L, et al. COL9A3: A third locus for multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 1999 Apr;64(4):1036–44. [CrossRef]

- Thur J, Rosenberg K, Nitsche DP, Pihlajamaa T, Ala-Kokko L, Heinegård D, et al. Mutations in cartilage oligomeric matrix protein causing pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia affect binding of calcium and collagen I, II, and IX. J Biol Chem. 2001 Mar 2;276(9):6083–92. [CrossRef]

- Cotterill SL, Jackson GC, Leighton MP, Wagener R, Mäkitie O, Cole WG, et al. Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia mutations in MATN3 cause misfolding of the A-domain and prevent secretion of mutant matrilin-3. Hum Mutat. 2005 Dec;26(6):557–65. [CrossRef]

- Hartley CL, Edwards S, Mullan L, Bell PA, Fresquet M, Boot-Handford RP, et al. Armet/Manf and Creld2 are components of a specialized ER stress response provoked by inappropriate formation of disulphide bonds: implications for genetic skeletal diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2013 Dec 20;22(25):5262–75. [CrossRef]

- Maddox BK, Keene DR, Sakai LY, Charbonneau NL, Morris NP, Ridgway CC, et al. The Fate of Cartilage Oligomeric Matrix Protein Is Determined by the Cell Type in the Case of a Novel Mutation in Pseudoachondroplasia *. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997 Dec 5;272(49):30993–7. [CrossRef]

- Chen TLL, Posey KL, Hecht JT, Vertel BM. COMP mutations: domain-dependent relationship between abnormal chondrocyte trafficking and clinical PSACH and MED phenotypes. J Cell Biochem. 2008 Feb 15;103(3):778–87. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz M, Becker A, Schmitz A, Weirich C, Paulsson M, Zaucke F, et al. Disruption of extracellular matrix structure may cause pseudoachondroplasia phenotypes in the absence of impaired cartilage oligomeric matrix protein secretion. J Biol Chem. 2006 Oct 27;281(43):32587–95. [CrossRef]

- Kung LHW, Rajpar MH, Preziosi R, Briggs MD, Boot-Handford RP. Increased classical endoplasmic reticulum stress is sufficient to reduce chondrocyte proliferation rate in the growth plate and decrease bone growth. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0117016. [CrossRef]

- Gualeni B, Rajpar MH, Kellogg A, Bell PA, Arvan P, Boot-Handford RP, et al. A novel transgenic mouse model of growth plate dysplasia reveals that decreased chondrocyte proliferation due to chronic ER stress is a key factor in reduced bone growth. Dis Model Mech. 2013 Nov;6(6):1414–25.

- Wang M, Kaufman RJ. Protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum as a conduit to human disease. Nature. 2016 Jan;529(7586):326–35. [CrossRef]

- Briggs MD, Dennis EP, Dietmar HF, Pirog KA. New developments in chondrocyte ER stress and related diseases. F1000Res. 2020 Apr 24;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-290. [CrossRef]

- Leighton MP, Nundlall S, Starborg T, Meadows RS, Suleman F, Knowles L, et al. Decreased chondrocyte proliferation and dysregulated apoptosis in the cartilage growth plate are key features of a murine model of epiphyseal dysplasia caused by a matn3 mutation. Hum Mol Genet. 2007 Jul 15;16(14):1728–41. [CrossRef]

- Nundlall S, Rajpar MH, Bell PA, Clowes C, Zeeff LAH, Gardner B, et al. An unfolded protein response is the initial cellular response to the expression of mutant matrilin-3 in a mouse model of multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2010 Nov;15(6):835–49. [CrossRef]

- Bell PA, Wagener R, Zaucke F, Koch M, Selley J, Warwood S, et al. Analysis of the cartilage proteome from three different mouse models of genetic skeletal diseases reveals common and discrete disease signatures. Biol Open. 2013 Aug 15;2(8):802–11. [CrossRef]

- Posey KL, Coustry F, Veerisetty AC, Liu P, Alcorn JL, Hecht JT. Chop (Ddit3) Is Essential for D469del-COMP Retention and Cell Death in Chondrocytes in an Inducible Transgenic Mouse Model of Pseudoachondroplasia. Am J Pathol. 2012 Feb;180(2):727–37. [CrossRef]

- Suleman F, Gualeni B, Gregson HJ, Leighton MP, Piróg KA, Edwards S, et al. A novel form of chondrocyte stress is triggered by a COMP mutation causing pseudoachondroplasia. Hum Mutat. 2012 Jan;33(1):218–31. [CrossRef]

- Posey KL, Coustry F, Veerisetty AC, Hossain M, Alcorn JL, Hecht JT. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents mitigate pathology in a mouse model of pseudoachondroplasia. Hum Mol Genet. 2015 Jul 15;24(14):3918–28. [CrossRef]

- Mullan LA, Mularczyk EJ, Kung LH, Forouhan M, Wragg JM, Goodacre R, et al. Increased intracellular proteolysis reduces disease severity in an ER stress-associated dwarfism. J Clin Invest. 2017 Oct 2;127(10):3861–5.

- Wang C, Tan Z, Niu B, Tsang KY, Tai A, Chan WCW, et al. Inhibiting the integrated stress response pathway prevents aberrant chondrocyte differentiation thereby alleviating chondrodysplasia. Rosen CJ, editor. eLife. 2018 Jul 19;7:e37673. [CrossRef]

- Dennis EP, Greenhalgh-Maychell PL, Briggs MD. Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia and related disorders: Molecular genetics, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic avenues. Developmental Dynamics. 2021;250(3):345–59. [CrossRef]

- Dennis EP, Watson RN, McPate F, Briggs MD. Curcumin Reduces Pathological Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress through Increasing Proteolysis of Mutant Matrilin-3. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Jan 12;24(2):1496. [CrossRef]

- Hecht JT, Veerisetty AC, Wu J, Coustry F, Hossain MG, Chiu F, et al. Primary Osteoarthritis Early Joint Degeneration Induced by Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Is Mitigated by Resveratrol. Am J Pathol. 2021 Sep;191(9):1624–37. [CrossRef]

- Di Girolamo N, Indoh I, Jackson N, Wakefield D, McNeil HP, Yan W, et al. Human mast cell-derived gelatinase B (matrix metalloproteinase-9) is regulated by inflammatory cytokines: role in cell migration. J Immunol. 2006 Aug 15;177(4):2638–50. [CrossRef]

- Xue M, March L, Sambrook PN, Jackson CJ. Differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and matrix metalloproteinase 9 by activated protein C: relevance to inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Sep;56(9):2864–74. [CrossRef]

- Shan A, Lu J, Xu Z, Li X, Xu Y, Li W, et al. Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 18 non-catalytically regulates the ER homeostasis and O-glycosylation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 2019 May 1;1863(5):870–82. [CrossRef]

- Akiyama H, Chaboissier MC, Martin JF, Schedl A, de Crombrugghe B. The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes Dev. 2002 Nov 1;16(21):2813–28. [CrossRef]

- Jackson GC, Mittaz-Crettol L, Taylor JA, Mortier GR, Spranger J, Zabel B, et al. Pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia: A 7-year comprehensive analysis of the known disease genes identify novel and recurrent mutations and provides an accurate assessment of their relative contribution. Human Mutation. 2012;33(1):144–57. [CrossRef]

- Duran I, Zieba J, Csukasi F, Martin JH, Wachtell D, Barad M, et al. 4-PBA treatment improves bone phenotypes in the Aga2 mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research [Internet]. 2022 Jan 8 [cited 2022 Jan 22];n/a(n/a). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jbmr.4501.

- Scheiber AL, Wilkinson KJ, Suzuki A, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Kaito T, Cheah KS, et al. 4PBA reduces growth deficiency in osteogenesis imperfecta by enhancing transition of hypertrophic chondrocytes to osteoblasts. JCI Insight. 2022 Feb 8;7(3):e149636. [CrossRef]

- Ray A, Bal BS, Ray BK. Transcriptional Induction of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 in the Chondrocyte and Synoviocyte Cells Is Regulated via a Novel Mechanism: Evidence for Functional Cooperation between Serum Amyloid A-Activating Factor-1 and AP-1. The Journal of Immunology. 2005 Sep 15;175(6):4039–48. [CrossRef]

- Duxfield A, Munkley J, Briggs MD, Dennis EP. CRELD2 is a novel modulator of calcium release and calcineurin-NFAT signalling during osteoclast differentiation. Sci Rep. 2022 Aug 16;12(1):13884.

- Kuleshov MV, Jones MR, Rouillard AD, Fernandez NF, Duan Q, Wang Z, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 Jul 8;44(Web Server issue):W90–7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).