1. Introduction

Cultural heritage in regions prone to earthquakes faces growing challenges due to climate change, urban development, and increased human activities, which heighten disaster risks (Cvetković, Gole, Renner, Jakovljević, & Lukić, 2024; Grozdanić, Cvetković, Lukić, & Ivanov, 2024; Shi, Visschers, & Siegrist, 2015). International guidelines such as the Sendai Framework and UNESCO/ICOMOS emphasize the importance of integrating seismic safety into heritage preservation policies (Beli, Renner, Cvetković, Ivanov, & Gačić, 2025; Cvetković, 2024; Cvetković, Lipovac, Renner, Stanarević, & Raonić, 2025; Cvetković & Šišović, 2024; Cvetković, Sudar, Ivanov, Lukić, & Grozdanić, 2024). Enhancing community awareness and institutional preparedness is crucial for maintaining both the cultural value and structural soundness of historic monuments (Barik, Bhuyan, & Hodam, 2025; Cvetković, Renner, & Jakovljević, 2024; Desalit, Duque, Edradan, Enciso, Enriquez, & Pan, 2025; Hanspal & Behera, 2024; Kaur & Singh, 2024; Mokhele, 2024; Sudar, Cvetković, & Ivanov, 2024; Tout, Rebouh, Dinar, Benzid, & Zouak, 2024). However, in Southeastern Europe, the relationship between how communities perceive heritage and their seismic preparedness has not been thoroughly examined; emerging evidence suggests that cultural values and community cohesion can influence disaster readiness.

Cultural heritage sites, such as historic buildings, monuments, and urban centers, are particularly susceptible to earthquake damage due to factors including age, construction materials, the lack of seismic safeguards, and ongoing decay (D’Alpaos & Valluzzi, 2020; Longobardi & Formisano, 2022; Sallam, Hassan, Sayed, Hafiez, Zahra, & Salem, 2023; Shabani, Alinejad, Teymouri, Costa, Shabani, & Kioumarsi, 2021). Masonry and timber structures, which are frequently found at these sites, are particularly vulnerable due to their brittleness, inferior materials, and outdated construction techniques. Earthquakes can cause structural failures, collapses, and the destruction of valuable architectural and artistic elements, while secondary effects, such as ground fractures, can further increase the risk (Narita et al., 2016; Sallam et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2023).

Numerous destructive earthquakes in Italy, Turkey, and Greece have resulted in the loss of invaluable historical assets, underscoring the urgent need for targeted mitigation measures to safeguard vast cultural and historical heritage from natural disasters. Many case studies worldwide have documented substantial damage: the 2021 Maduo earthquake in China and the 2023 Kahramanmaras earthquake in Turkey resulted in noticeable deformations and visible destruction of heritage sites, even far from the epicenters (Boyoğlu, Chike, Caspari, & Balz, 2023; Zhu et al., 2023). On the other side, in Italy, repeated seismic events have led to the permanent loss of irreplaceable cultural assets in historic centers (Cardani & Garavaglia, 2024; Giuliani, De Falco, & Cutini, 2022; Longobardi & Formisano, 2022). The 2015 Gorkha earthquake in Nepal caused widespread destruction and significant damage to heritage structures, with only a few avoiding substantial harm (Pan, Wang, Guo, & Yuan, 2018).

Research from other parts of Europe shows that actively involving communities with cultural heritage can build resilience by enhancing social bonds and promoting collaborative disaster risk strategies (Narita et al., 2016; Shabani et al., 2021; Taffarel, Da Porto, Valluzzi, & Modena, 2018; Zhu et al., 2023). Still, there is a gap in operational approaches that directly connect how people perceive heritage to their earthquake preparedness, with most initiatives focusing on overall community resilience rather than specific actions for earthquakes (Cacciotti et al., 2021; D’Alpaos & Valluzzi, 2020; Fabbricatti, Boissenin, & Citoni, 2020). There is an acknowledged need for participatory management tools and shared governance frameworks that incorporate heritage values into disaster risk reduction strategies. The literature emphasizes the necessity for further research to understand how perceptions of heritage can be utilized to enhance seismic preparedness within communities (Appleby--Arnold, Brockdorff, Jakovljev, & Zdravković, 2020; Avvisati et al., 2019; Cacciotti et al., 2021; Fabbricatti, Boissenin, & Citoni, 2020).

Based on previous mentions, adequate protection relies on comprehensive vulnerability assessments that integrate structural analysis, site-specific emergency planning, and intervention prioritization (D’Alpaos & Valluzzi, 2020; Ferrari, 2024; Ožić, Markić, Moretić, & Lulić, 2023; Shabani et al., 2021). Quick assessment methods and coordinated emergency response strategies are essential to balance safety, conservation, and limited resources. However, challenges remain in large-scale risk evaluation and developing non-invasive, effective retrofitting techniques (Ožić et al., 2023; Shabani et al., 2021; Taffarel et al., 2018).

The European south, with the Balkan Peninsula, lies in zones of very pronounced seismic activity. According to U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) data for 1990–2023, in the Southern Europe region, comprising 12 countries, 343 earthquakes with magnitudes 3.5-7.8 on the Richter scale were recorded. By comparison, this is significantly more than other European regions, where for the same period, 46 earthquakes were recorded in Northern Europe and 31 in Eastern Europe. The Bay of Kotor stands out for its exceptional cultural and historical heritage, including UNESCO-listed medieval cores such as Kotor, Perast, and Risan. At the same time, the Montenegrin and southern Croatian coasts lie in one of Europe’s most earthquake-prone regions. Past destructive earthquakes, notably the 1667 Dubrovnik earthquake and the 1979 Montenegro earthquake, caused widespread damage to historic masonry structures and cultural monuments. These events revealed long-standing structural vulnerabilities and reinforced the need to strengthen community preparedness and institutional protection systems. During the 1979 earthquake, seismic intensity in Dubrovnik reached VII on the MCS scale, resulting in damage to 1,071 buildings, including 33 fortification structures, 106 religious buildings, 45 buildings of various public uses, and 885 residential and commercial buildings. The most affected areas included Konavle, Župa Dubrovačka, the historic core with the Pile and Ploče zones, Rijeka Dubrovačka, Slano, and Ston, illustrating the severe exposure of cultural heritage to seismic hazards.

In Croatia there are two areas of heightened seismic activity: from the border with Slovenia to the west of the country through Medvednica to Zagreb and the surrounding area and Bilogora to the east of the country, and south of the border with Slovenia toward the coast to Dubrovnik, with prominent zones of the Rijeka–Senj littoral, Dalmatian hinterland, and the Dubrovnik and Konavle areas. In the risk zone are, therefore, historically important towns with rich cultural-historic heritage such as Trogir, Split, and Dubrovnik (Bejić, 2024). Throughout history, Croatia has experienced several devastating earthquakes, including one on Pag Island in 361 and one in Dubrovnik in 1667. Both earthquakes were of magnitude 10 on the Mercalli scale. It is estimated that around 3,000 people died in Dubrovnik. Destructive earthquakes also occurred in the following years: 1511 – Slunj (9–10 MCS), 1757 – Virovitica (9 MCS), 1880 – Zagreb (8 MCS), 1909 – Pokolje (8–9 MCS), 1942 – Imotski (9), 1962 – Makarska (9 MCS), 1979 – Montenegrin coast (7 MCS), 1996 – Ston (8 MCS), 2020 – Zagreb (7 MCS), 2020 – Sisak-Mose region (8 MCS) (Vuljak, 2022).

This study aims to: (i) explore residents’ perceptions of cultural–historical heritage and earthquake risk in the Bay of Kotor (Montenegro) and the Dubrovnik Littoral (Croatia); (ii) evaluate perceived preparedness and institutional capacity; and (iii) analyze how sociodemographic factors—such as gender, age, education, and residence—affect these perceptions. Using a cross-sectional survey of 540 participants (split evenly) and a multi-method approach—including descriptive statistics, t-tests, ANOVA, Pearson correlations, and multiple regression on a combined “Cultural-Heritage and Seismic Preparedness Attitudes” index—the research aims to identify gaps between cultural valuation and practical readiness, ultimately offering evidence-based suggestions to improve coordination, public training, and seismic safety measures compatible with heritage preservation.

1.1. Literature Review

Cultural heritage monuments pose distinctive challenges for seismic risk assessment due to their unique architectural features, construction methods, and priceless historical and artistic elements (Formisano & D’Amato, 2021; Maio, Estêvão, Ferreira, & Vicente, 2020; S, S, A, & A, 2025; Shabani et al., 2021). Unlike regular buildings, they are often centuries old, lack seismic design considerations, and must preserve their original fabric, limiting structural modifications. Consequently, traditional engineering assessment methods often fall short in accurately determining their vulnerability (D’Alpaos & Valluzzi, 2020; Lagomarsino & Cattari, 2014; Lourenço & Karanikoloudis, 2019; Spyrakos, 2018; Torelli, D’Ayala, Betti, & Bartoli, 2019; Zizi, Rouhi, Chisari, Cacace, & De Matteis, 2021).

To overcome these issues, recent research highlights the need for specialized, multi-layered assessment approaches tailored to heritage sites. Performance-based and displacement-based methods are frequently recommended because they provide more accurate predictions of structural response by accounting for both load-bearing and artistic components (Lagomarsino & Cattari, 2014; Torelli et al., 2019; Zizi et al., 2021).

Additionally, decision-making tools that employ multiple criteria and hierarchical structures, such as the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), are used to prioritize conservation efforts effectively. They do so by integrating cultural, historical, and social values with engineering data (D’Alpaos & Valluzzi, 2020; Sevieri et al., 2020). For larger regions, rapid visual inspections and vulnerability index approaches facilitate quick initial assessments, enabling practitioners to identify monuments requiring more detailed analysis (Chieffo, Ferreira, Da Silva Vicente, Lourenço, & Formisano, 2023; Formisano & D’Amato, 2021; Maio et al., 2020; Sevieri et al., 2020). At the same time, organizations such as ICOMOS, ISO, and national heritage agencies have established guidelines to support systematic evaluation and planning for interventions. Nonetheless, these standards still need adaptation to accommodate different typologies, historical circumstances, and local hazard conditions (Bartoli, Betti, & Vignoli, 2016; Lagomarsino & Cattari, 2014; Torelli et al., 2019; Zizi et al., 2021).

Cultural heritage monuments around the world are at considerable risk from earthquakes because of their age, distinctive construction, and priceless value. Evaluating and reducing seismic danger for these structures is challenging, demanding tailored approaches that ensure safety while maintaining their historical and cultural significance (Bartoli, Betti, & Vignoli, 2016; D’Alpaos & Valluzzi, 2020; Lourenço & Karanikoloudis, 2019; Ravankhah, Schmidt, & Will, 2017; Sevieri et al., 2020).

Based on various statistical data originating from the countries of the European Union, Asia, South and North America, a modern list of natural disasters has been made, ranked according to the relative frequency and extent of damage to cultural heritage. In that list, the first place has been assigned to earthquakes, followed by floods, hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones (which unite with each other), followed by landslides, storms, tornadoes, tsunamis and, finally, volcanic eruptions (Kurtović-Folić & Folić, 2020).

In Montenegro and Croatia, research focusing specifically on the seismic vulnerability of cultural and historical heritage, community risk perception, and evidence-based approaches to reducing disaster risk for heritage assets remains limited. Existing studies tend to address only particular segments of this multifaceted issue. For instance, Grozdanić and Cvetković (2024), in their monograph Exploring Multifaceted Factors Influencing Community Resilience to Earthquake-Induced Geohazards: Insights from Montenegro, examine key determinants of seismic resilience and prerequisites for planning and implementing effective disaster-risk reduction strategies. Their interdisciplinary framework connects demographic, socioeconomic, and psychosocial components to understand better how local communities perceive and respond to earthquake hazards.

Technical aspects of heritage vulnerability have also been partially studied. Tomanović et al. (2021) analyzed medieval and early-modern masonry structures (12th–19th century) in the Bay of Kotor, identifying critical structural weaknesses and proposing protective and retrofitting measures. Their analysis included several listed cultural-heritage monuments and provided valuable engineering insights applicable to earthquake-prone coastal urban areas.

At the regional level, Grozdanić et al. (2024) conducted a comparative quantitative study on earthquake disaster preparedness across Southeast Europe—including Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia—and found that demographic characteristics such as age, education level, and gender significantly contribute to preparedness behaviors and risk awareness. Complementing this, Cvetković et al. (2024) provided a qualitative perspective on seismic resilience in Montenegro. Through semi-structured interviews conducted in the country’s most hazard-exposed municipalities (Nikšić, Podgorica, Bar, Kotor, Cetinje, Budva, Herceg Novi, and Berane), they highlighted context-specific challenges and capacities shaping community response and preparedness.

Despite these contributions, the intersection of cultural-heritage preservation and seismic risk management remains under-researched in both countries. A systematic integration of engineering, sociocultural, and governance perspectives remains largely absent, underscoring the need for more comprehensive, transdisciplinary studies in the region. A recent qualitative study conducted in Montenegro offers an important perspective on seismic resilience in the Western Balkans context. By conducting semi-structured interviews with residents of the most hazard-exposed municipalities, the authors collected insights into institutional preparedness, community response capacity, and individual awareness levels (Cvetković et al., 2024). The findings highlight substantial gaps in both governance mechanisms and household preparedness practices, underscoring the need for locally tailored preparedness programs, improvements in structural retrofitting, and more systematic public-risk communication to enhance overall resilience.

In Croatia, research efforts have increasingly focused on the seismic vulnerability of UNESCO-protected heritage sites, most notably the historic core of Dubrovnik. Paneva et al. (2023) developed a Rehabilitation Strategy for the Rector’s Palace—one of the Old City’s most culturally significant structures exposed to high seismic risk. This 13th-century monument has undergone multiple architectural transformations triggered by destructive events, including the 1435 fire, the 1463 gunpowder explosion, and major earthquakes in 1520, 1667, and 1979. Drawing on archival documentation, previous investigations, field surveys, and laboratory testing, the authors identified critical structural weaknesses typical of historic masonry buildings in Mediterranean seismic environments.

Likewise, Azair et al. (2023) assessed the seismic performance of the 18th-century Jesuit College in Dubrovnik’s Old City, as part of the Croatian Science Foundation project Assessment of Seismic Risk for Cultural Heritage in Croatia — SeisRICHerCRO. Their findings indicated that material degradation, architectural configuration, and localized structural deficiencies influence the building’s seismic performance, underscoring the urgent need for dedicated conservation strategies. In Italy, the architectural heritage was seriously affected by the earthquake that occurred on April 6, 2009 in the Abruzzo region. Keystone of the operating process was the standardization of the damage survey and of its immediate and correct interpretation, through dedicated survey forms for churches and palaces. The experience in the field of temporary safety measures was extremely interesting: ideas for engineering the process were developed, in cooperation with the work of the fire brigade men, that are highly experienced technicians in the “emergency” field. Finally, monitoring plans for some important monuments have been set up for the control of the damage progression and the analysis of the structural behavior of buildings after the earthquake (Claudio et al., 2010). On a broader theoretical level, Pecchioli et al. (2020) emphasize the strong synergy between cultural-heritage protection, seismology, archaeoseismology, geophysics, and structural engineering, underscoring the value of interdisciplinary approaches in seismically active cultural landscapes.

Outside the Adriatic region, global experiences further contribute to knowledge in this area. For example, Dogangun and Sezen (2012) investigated seismic damage to monumental masonry structures in Turkey affected by the 1999 earthquake, revealing the high vulnerability of domed buildings and tall minarets and identifying common factors in structural deterioration. In Greece, Sboras et al. (2017) developed a GIS-based decision-support tool that integrates geological, geotechnical, and cultural heritage data to assess seismic hazard for monuments and archaeological sites, representing a significant technological advancement in heritage protection. The Wenchuan earthquake, which happened on May 12th, 2008, caused severe damage to settlements of the Qiangs in the upper reaches of Min River, including the ‘‘Tangping Qiang village,’’ which plays a prominent role in Qiang stockaded villages. The paper discusses and establishes measures to protect these facilities. (Chen, 2012). Risks to Cultural Heritage in Western and Central Asia is a study that examines and categorizes risks (natural and unnatural) to cultural heritage in West and Central Asia (Hejazi, 2018). Collectively, these studies illustrate both the complexity of safeguarding cultural heritage in earthquake-prone environments and the necessity of combining community preparedness, engineering assessment, and conservation science in an integrated risk-reduction framework.

2. Methods

This study investigates the seismic safety of cultural and historical monuments in the Bay of Kotor (Montenegro) and the Dubrovnik Littoral (Croatia)—two coastal regions of exceptional cultural, architectural, and historical importance. Both areas are UNESCO-listed and exposed to recurrent seismic activity due to their position along the Adriatic-Ionian seismic belt. The research focuses on assessing levels of awareness, preparedness, and institutional response regarding the seismic vulnerability of heritage structures, and on identifying gaps in current protection measures and community perceptions.

2.1. Aims and Objectives

The main aim of this research is to examine how cultural heritage stakeholders—local communities, professionals, and institutions—perceive and address seismic risks in heritage preservation contexts. Specific objectives include:

To analyze public and expert perceptions regarding the seismic vulnerability of cultural monuments.

To evaluate existing institutional frameworks, technical measures, and community-based practices for heritage protection.

To identify challenges in implementing seismic risk mitigation in historical urban areas.

To develop recommendations for improving seismic resilience and integrating heritage protection into disaster risk reduction strategies.

2.2. Hypotheses

The following hypotheses guide the study:

H1: The level of awareness among residents and professionals about the seismic vulnerability of cultural monuments in the Bay of Kotor and the Dubrovnik Littoral is relatively low.

H2: Current protection and restoration measures do not adequately reflect the actual seismic risk levels of the studied areas.

H3: Perceptions of seismic risk are influenced by demographic factors such as education, age, and professional background.

H4: Institutional coordination and intersectoral cooperation (between heritage institutions, local authorities, and civil protection) are insufficient, which reduces the overall effectiveness of risk reduction strategies.

H5: Strengthening education, communication, and technical reinforcement measures can significantly improve the resilience of cultural and historical monuments against earthquakes.

2.3. Sample

The total sample included 540 respondents, evenly split between the Bay of Kotor and the Dubrovnik Littoral (50% each), ensuring balanced regional representation. Gender distribution was nearly equal, with 51.7% female and 48.3% male, reflecting the general population in both areas. The age distribution showed the largest group was aged 46–55 years (19.6%), followed by those aged 36–45 (18.3%), while younger participants (under 18 and 18–25 years) together made up about 30%, indicating a wide generational range and enabling comparisons across different age groups. In education, most respondents had secondary education (53.3%), with a significant portion holding higher education degrees (44.1%), and only 2.6% reporting primary education. This profile suggests that the sample primarily comprises adults with strong educational backgrounds, likely enhancing their understanding of heritage preservation and disaster risk awareness (

Table 1).

2.4. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire consisted of 15 Likert-scale statements (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) addressing: (i) heritage valuation—covering tourist resource, national resource, identity, record of diverse influences, and preservation importance; (ii) risk awareness—both personal and community; (iii) preparedness intentions—interest in training; and (iv) institutional/structural protection—government protection, institutional capacity, code compliance, community measures, and training organization. Additionally, two items referenced the 1979 earthquake, focusing on learning and impacts on monuments. To represent overall attitude, we averaged these 15 items into a single index, Cultural-Heritage and Seismic Preparedness Attitudes (CHSPA), with higher scores indicating a more favorable view of heritage and a stronger preparedness orientation. We assessed the index’s internal consistency using Cronbach’s α, examined item–total correlations, and performed sensitivity analyses to evaluate the index’s robustness with and without negatively valenced items.

2.5. Study Area

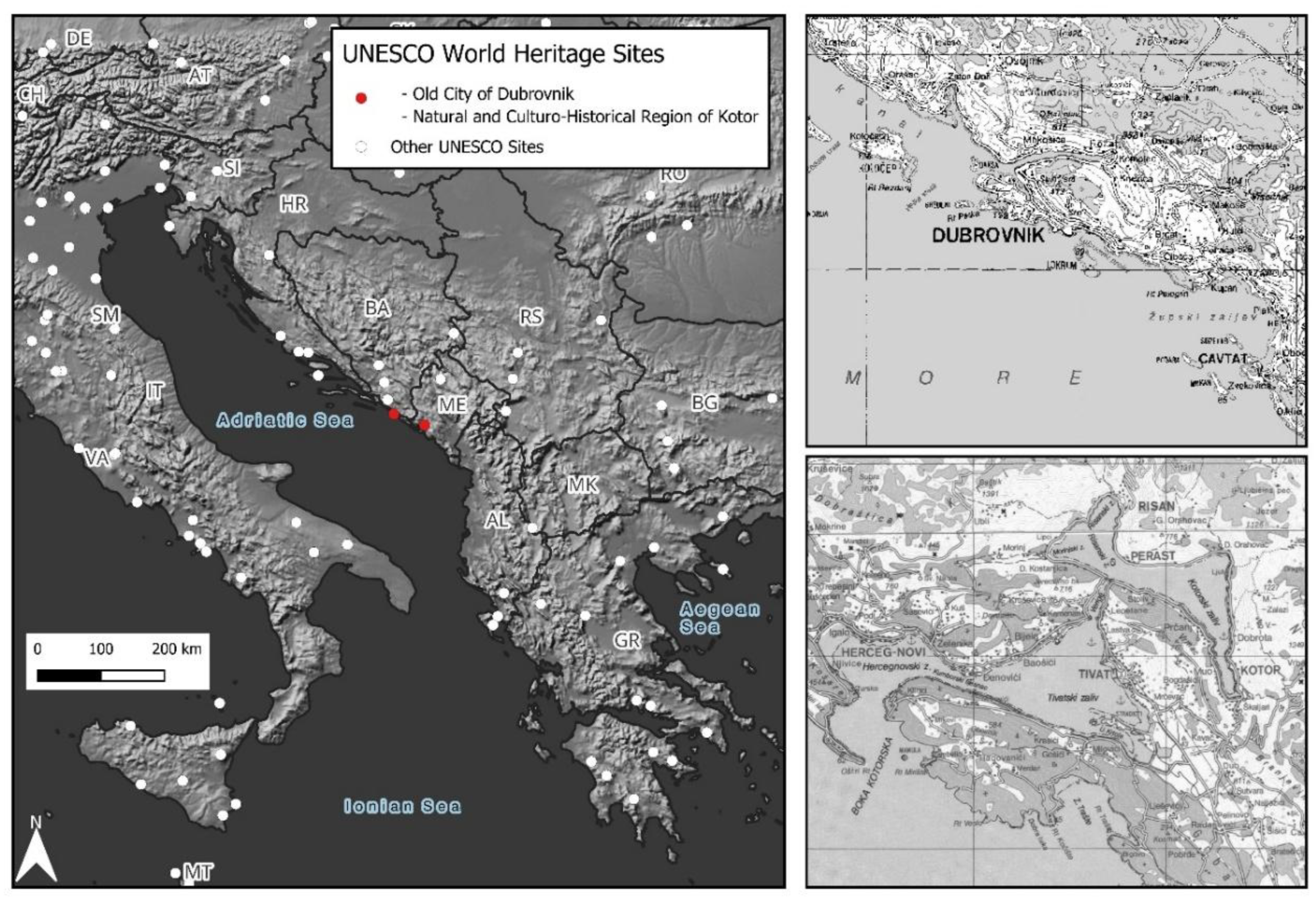

The Bay of Kotor, situated in southwestern Montenegro (see

Figure 1), is a highly complex and distinctive part of the Adriatic coast, characterized by its unique geotectonic, morphological, and hydrographic features (Radojičić, 2008). This internal bay is notably intricate and dispersed, with its shape evolving from the entrance at Boka—between the Lustica Peninsula and Cape Oštro—to Kotor, where it features five inner bays and two straits in a sequence of expansions and contractions. Recognized as one of the most complicated bays along the Adriatic and among the most diverse in Europe (Nikolić, 2000), it attracts many researchers and nature enthusiasts due to its mild Mediterranean climate, rich Mediterranean and subtropical vegetation, and diverse animal life (Radojičić, 2015). Boka Kotorska can be rightly described as a highly complex, authentic, endlessly captivating, and unique relief-hydrographic and cultural-historical phenomenon (Radović, 2010). The Dubrovnik coast is the southeasternmost section of Croatia’s shoreline (see

Figure 1). It features complex geology, primarily carbonate rocks, and a Dinaric orientation. The landscape features elevated areas and depressions arranged in parallel, with karst terrain prevailing.

The current land-sea configuration resulted from post-Pleistocene glacio-eustatic sea-level rise (Friganović, 1974). Continuous wave action (abrasion) has shaped various coastal features, such as bays, coves, sandy and gravel beaches, and cliffs (Marić, 2009). The region’s tectonic structure is quite unstable, as indicated by numerous rock traces and earthquake records (Friganović, 1974). Due to the limestone and dolomite composition, permeability is high, preventing significant surface water flows; instead, water infiltrates underground and reappears as submarine springs along the coast and beneath the sea (Marić, 2009). The Mediterranean climate, combined with rich flora and fauna and numerous natural and cultural-historical sites, strongly supports tourism development.

The coastal regions along the Bay of Kotor in Montenegro and the Dubrovnik Littoral in Croatia are renowned for their remarkable cultural and architectural heritage, much of which originates from the medieval and Renaissance eras. Nonetheless, these zones are also among Southeastern Europe’s most seismically active areas. The challenge of balancing heritage preservation with seismic risk mitigation has become a vital issue for local governments, researchers, and global organizations like UNESCO and ICOMOS. Despite past earthquakes that caused significant destruction, many monuments still face structural vulnerabilities, and awareness of seismic dangers among residents and officials remains limited. It is crucial to understand community perceptions of seismic threats better and to evaluate the effectiveness of existing safety measures.

The coastal part of Montenegro, the Podgorica–Skadar Basin, and the Berane Basin are located in seismically unstable areas. The entire Montenegrin coast is within a risk zone for destructive earthquakes. The cities of Boka Kotorska stand out for their rich cultural and historical heritage from various historical periods (Kotor, Perast, Risan, Herceg Novi). The Kotor–Risan Bay, with the city of Kotor, is inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List for natural and cultural heritage (Grozdanic & Cvetković, 2024; Radojičić, 2015).

The first reports of a strong earthquake in Montenegro that caused significant damage to Epidaurum (modern-day Cavtat) and Boka Kotorska date back to 373 AD. From that time until 1520, another 14 devastating earthquakes were recorded. Notably powerful earthquakes include the 444 AD quake that destroyed Ulcinj, and the 518 AD quake that toppled Duklja, an ancient Roman settlement near today’s Podgorica, founded in the 1st century. Mighty and destructive earthquakes struck Kotor in 1520, 1537, 1559, and 1563. The earthquake on June 13, 1563, destroyed and severely damaged all settlements in the Boka Kotorska area (estimates suggest it had a magnitude of 10 on the Mercalli scale). Kotor and its surroundings were heavily affected.

In Kotor, 180 of 750 houses were destroyed. About 150 residents lost their lives. A series of earthquakes was recorded in the 17th century: significant destruction occurred in 1608 and 1610, and several successive earthquakes in 1631 affected Herceg Novi, Kotor, Budva, and other settlements, resulting in significant material damage and the deaths of around a thousand people. The earthquake of April 9, 1667, which severely impacted Dubrovnik, Croatia, and is thus called the “Dubrovnik earthquake,” also left heavy consequences for the towns and settlements of Boka Kotorska. Kotor, Perast, Risan, Herceg Novi, and other cities outside the modern Montenegrin coast—Budva, Bar, and Ulcinj—were destroyed. Data on the number of casualties from these earthquakes include approximately 200 deaths in Kotor, 40 in Perast, and 70 in Budva. In Kotor, two-thirds of the houses, all churches, palaces, and city walls were destroyed or damaged.

The most monumental religious monument in Kotor, the Romanesque cathedral of St. Tripun, built in 1166, was heavily damaged when its entire western facade, two bell towers, and the bell tower tympanum collapsed. In Budva, only five houses remained undamaged. Earthquakes of magnitude 9 or higher on the Mercalli scale were recorded along the Montenegrin coast in 1780 and 1830, while significant earthquakes also struck in 1711, 1746, and 1881; however, detailed information about their intensity, material damage, and casualties is lacking. Strong earthquakes were also recorded in the Podgorica–Skadar Basin in 1905, 1926, and 1927, and a major quake hit the Berane Basin in 1928. The 1968 earthquake caused extensive material damage in Petrovac and Bar (Marković & Vujičić, 1997; Radojičić, 2015; Belan, 2011; Abramović & Karadžić, 2017).

The last major earthquake to affect the entire territory of Montenegro occurred on April 15, 1979. On the Montenegrin coast, it registered a magnitude of 9 on the Mercalli scale, around Podgorica 8, in Nikšić 7, while in the northeast of Montenegro it measured 6 (Radojičić, 2015). The earthquake struck, among other things, a vast cultural heritage, especially in towns with old urban cores such as Herceg Novi, Kotor, Budva, Bar, Ulcinj, and Cetinje, which are about 13 km from the sea. The quake affected 1,641 immovable and 30,000 movable cultural monuments (Marković & Vujičić, 1997). In this earthquake, 101 residents of Montenegro lost their lives, around 1,700 were injured, both lightly and severely, and 35 people perished in neighboring Albania. The estimated material damage amounted to 4.5 billion dollars, which, according to data from the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank (Fed) as of 2024, would be equivalent to about 19 billion current U.S. dollars (

https://www.bbc.com/serbian/lat/balkan-68758421).

2.6. Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS (versions 28 and 29) on the entire sample (N = 540). Furthermore, for example, fifteen Likert-scale items (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) were examined for polarity. It has been found that one required reverse coding and averaging to create a composite score, the Cultural-Heritage and Seismic Preparedness Attitudes (CHSPA), where higher scores indicate greater heritage value and preparedness. Predictors were coded as follows: gender (0 = male, 1 = female), residence (0 = Dubrovnik Littoral, 1 = Bay of Kotor), education level (1 = primary, 2 = secondary, 3 = higher; based on AUTORECODE/RECODE), and age (treated as ordered categories approximating interval data for correlation and regression analyses). Missing data were minimal, and listwise deletion was used for each analysis. Descriptive statistics (mean, SD, range) were calculated for each item and for CHSPA. Results are reported as two-tailed tests with α = 0.05, including exact p-values (0.000 shown as 0.001), 95% confidence intervals, and effect sizes.

Group differences were tested with independent-samples tests for gender and residence, and one-way ANOVA for education, with Tukey HSD or Games–Howell post hoc tests when variances were unequal. Associations with age were assessed using Pearson’s r (two-tailed), supplemented by Spearman’s ρ when nonlinearity or outliers were suspected. Effect sizes were interpreted using standard benchmarks. To identify independent predictors of overall attitudes, a multiple linear regression was conducted with CHSPA as the dependent variable and gender, residence, education, and age entered simultaneously. Results include B, SE(B), β, t, p, 95% CI, and model fit indices (R, R², adjusted R², standard error, F). Assumptions such as normality, homoscedasticity, and linearity were evaluated with Q–Q plots, Levene’s test, and residual/partial plots; multicollinearity was checked via tolerance and VIF (all VIFs ≈ near 1), and influence was assessed with Cook’s D and studentized residuals (no cases altered conclusions). Due to the confirmatory approach and comprehensive effect size reporting, the alpha level remained at. .05 without multiple correction, emphasizing the magnitude and precision of effects over significance alone.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistical Results Analysis

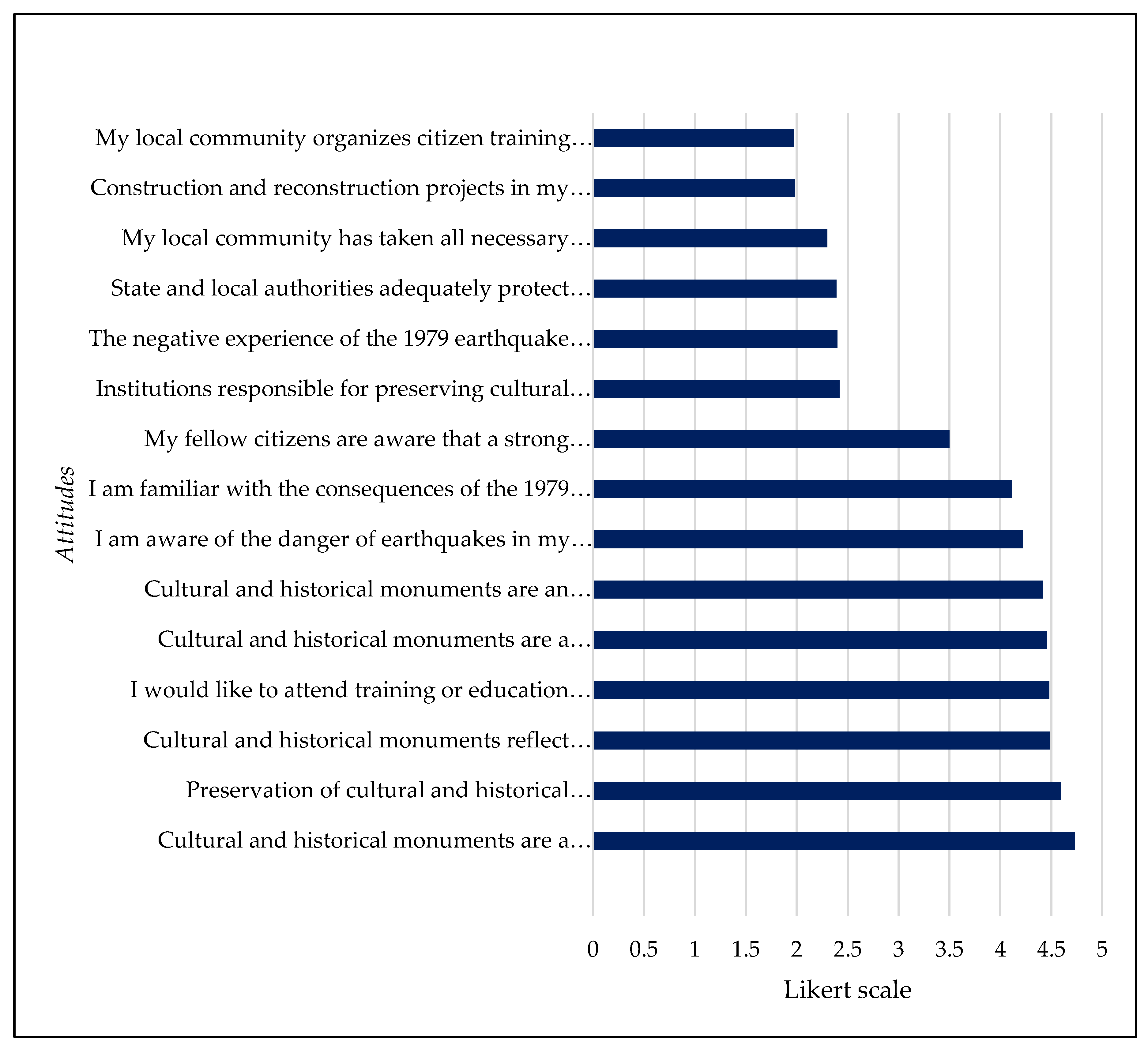

Table 2 provides a detailed overview of how people perceive the significance of cultural and historical monuments and their connection to seismic safety in the Bay of Kotor and Dubrovnik Littoral. The findings reveal a strong emotional and cultural connection to heritage, but also highlight a lack of institutional preparedness and community initiatives for earthquake risk mitigation. Respondents mostly agreed that “Cultural and historical monuments are a valuable tourist resource” (M = 4.73, SD = 0.505, Rank = 1), indicating awareness of heritage’s economic and cultural role in tourism and development. They also strongly supported “Preservation of cultural and historical monuments is important” (M = 4.59, Rank = 2), reflecting a deep understanding of heritage conservation. Scores for statements highlighting the symbolic and identity importance of monuments were also high. People agreed that “Cultural and historical monuments reflect diverse cultural, civilizational, and religious influences throughout history” (M = 4.49, Rank = 3) and that they are “a national resource connecting generations through history” (M = 4.46, Rank = 5). These views show that cultural heritage is seen not just as architecture but as a testament to collective memory, identity, and continuity (

Table 1).

Interestingly, many respondents expressed a personal willingness to learn and participate, agreeing with “I would like to attend training or education related to earthquake protection” (M = 4.48, Rank = 4), indicating openness to disaster preparedness initiatives. Meanwhile, awareness of natural hazards is high—“I am aware of the danger of earthquakes in my place of residence” (M = 4.22, Rank = 7)—but perceptions of community readiness are lower. The statement “My fellow citizens are aware that a strong earthquake could occur in our town or village” scored moderately (M=3.50, Rank=9), suggesting uneven awareness in the community. Historical experience influences perceptions; many respondents knew about “the consequences of the 1979 earthquake on cultural and historical monuments” (M = 4.11, Rank = 8), but did not see this event as prompting significant improvements in preparedness.

The statement “The negative experience of the 1979 earthquake contributed to increased protection levels in my local community” scored low (M= 2.40, Rank=11), indicating a disconnect between historical awareness and institutional learning. Regarding capacities, results reveal concern: confidence that “Cultural and historical monuments are adequately protected by state and local authorities in case of an earthquake” (M= 2.39, Rank=12) and that “Institutions have sufficient expertise and resources for seismic protection” (M= 2.42, Rank=10) remain low. Even lower scores relate to community measures, such as “My local community has taken all necessary measures to protect people and property” (M= 2.30, Rank=13), and “Construction and reconstruction projects respect building regulations for earthquake-prone areas” (M= 1.98, Rank=14).

The lowest-rated statement was “My local community organizes citizen training or education on how to react in the event of an earthquake” (M = 1.97, Rank = 15), highlighting an urgent need for public education, drills, and capacity-building. Overall, the results reveal a paradox: strong community pride in monuments and identity exists, but practical protection from earthquakes is limited. Cultural values are deeply rooted, yet translating this awareness into concrete preparedness and risk mitigation remains a challenge. Bridging this gap between emotional attachment and modern risk practices is essential. Improving institutional coordination, offering specialized training, and engaging citizens can turn high cultural awareness into resilient, proactive heritage protection along the Adriatic (

Table 1 and

Figure 2).

Table 3 provides a detailed overview of how respondents from Boka Kotorska and Dubrovnik Littoral perceive the importance of cultural and historical monuments and their connection to seismic safety. The findings reveal a strong emotional and cultural attachment to heritage, alongside a weak perception of institutional readiness and local community action. Overall, responses are pretty similar across the two regions, with Dubrovnik Littoral respondents slightly more aware of earthquake risks and Boka Kotorska respondents showing more confidence in community capabilities.

Respondents largely agree that cultural and historical monuments are a valuable societal asset. The statement “Cultural and historical monuments are a valuable tourist resource” received the highest average ratings in both areas (Boka: M = 4.74, SD = 0.48; Dubrovnik: M = 4.71, SD = 0.53), indicating that heritage is seen as fundamental to tourism and economic identity. Likewise, strong support for “Preservation of cultural and historical monuments is important” (Boka M = 4.57; Dubrovnik M = 4.60) reflects widespread acknowledgment of the moral and civic duty to protect cultural heritage. Respondents also agree that “Cultural and historical monuments are an important national resource that connects and defines generations across history on specific territory” (Boka M = 4.49; Dubrovnik M = 4.44) and that “Cultural and historical monuments are a significant material resource reflecting influences from various cultures, civilizations, and religions that have shaped the preserved material heritage” (Boka M = 4.49; Dubrovnik M = 4.48). These results emphasize that the symbolic, identity, and historical aspects of heritage are equally recognized in both regions. The statement “Cultural and historical monuments are an important source for understanding contemporary identity” (Boka M = 4.41; Dubrovnik M = 4.43) further reinforces the view that monuments are not just relics of the past but dynamic elements of collective identity.

Awareness of natural hazards is also high across both regions. Respondents mostly agree with “I am aware of the danger of earthquakes in my place of residence” (Boka M = 4.17; Dubrovnik M = 4.26), indicating that citizens recognize the risks associated with living in seismically active zones. However, agreement drops for “My fellow citizens are aware that a strong earthquake could occur in our village/town” (Boka M = 3.56; Dubrovnik M = 3.44), suggesting a gap between personal awareness and perceptions of communal preparedness. This indicates that although individuals feel informed, they are less confident in the broader community’s readiness.

Institutional and community preparedness received low ratings. The statement “My local community has taken all necessary measures to protect people and property from possible earthquakes” scored low in both regions (Boka M = 2.37; Dubrovnik M = 2.22), as did “My local community organizes citizen training/education on how to respond during earthquakes” (Boka M = 2.08; Dubrovnik M = 1.86), which had the lowest overall mean score. These results indicate a lack of systematic education, training, or drills in disaster preparedness. Despite this, participants showed a high level of interest in such activities, as evidenced by the very high agreement with the statement “I would like to attend some form of training/education related to earthquake protection” (Boka M = 4.47; Dubrovnik M = 4.49). This reveals a paradox: high interest and awareness coexist with limited institutional support and initiatives.

History also influences perception. Most respondents are familiar with the impacts of the 1979 earthquake, as shown by “I am familiar with the consequences that the 1979 earthquake had on cultural/historical monuments in my area” (Boka M = 4.09; Dubrovnik M = 4.14). However, they show little belief that this event led to real safety improvements, evidenced by low agreement with “The negative experience from the 1979 earthquake contributed to increasing protection against earthquakes in my community” (Boka M = 2.41; Dubrovnik M = 2.39). This indicates that although the disaster’s memory remains strong, it has not resulted in ongoing institutional learning or structural changes.

Perceptions of institutional protection and enforcement of regulations are notably low. The statement “Cultural and historical monuments are adequately protected by the state and local government during an earthquake” received low scores (Boka M = 2.36; Dubrovnik M = 2.41), as did “Institutions responsible for preserving cultural and historical monuments have sufficient expertise and resources for seismic protection” (Boka M = 2.39; Dubrovnik M = 2.46). Even lower were ratings of construction practices; for instance, “During the construction or reconstruction of buildings, regulations for areas with higher earthquake risk are followed” scored some of the lowest (Boka M = 2.09; Dubrovnik M = 1.87). These findings reveal ongoing institutional weaknesses, a lack of technical enforcement, and low public confidence in heritage protection systems.

Overall, the results show a dual reality: both Boka Kotorska and Dubrovnik Littoral residents exhibit strong cultural pride, heritage awareness, and willingness to learn, yet remain skeptical about institutional competence and preparedness. Respondents from Dubrovnik Littoral are slightly more aware of risks, while participants in Boka Kotorska have somewhat more confidence in the community’s response capacity. Both regions display a shared pattern—deep cultural consciousness coexisting with limited disaster preparedness. Addressing this gap involves strengthening institutional coordination, enforcing seismic regulations, and promoting education and citizen involvement. Turning cultural awareness into active preparedness is critical for ensuring that heritage in these Dalmatian regions remains protected and resilient against future seismic events (

Table 3).

3.2. Correlation Statistical Results Analysis

The Independent Samples T-Test (

Table 3) examined gender differences in respondents’ attitudes towards the importance of cultural-historical monuments and their perceptions of seismic safety. Results across all fifteen statements showed no statistically significant differences between male and female participants (all p > 0.05), indicating strong agreement across genders on cultural and safety-related issues.

Both male (M = 4.61, SD = 0.52) and female (M = 4.57, SD = 0.56) respondents highly agreed that preserving cultural and historical monuments is essential (t = 0.758, p = 0.449). The statement that cultural and historical monuments are a valuable tourist resource received the highest mean scores among all items (M_male = 4.75, SD = 0.47; M_female = 4.70, SD = 0.53), with no significant gender difference (t = 1.285, p = 0.199). Similar patterns appeared for views that monuments connect generations through history (M_male = 4.49, SD = 0.57; M_female = 4.44, SD = 0.58; t = 0.851, p = 0.395), and that they reflect diverse cultural, civilizational, and religious influences (M_male = 4.51, SD = 0.57; M_female = 4.47, SD = 0.64; t = 0.834, p = 0.405). Both genders agreed that cultural and historical monuments help understand contemporary identity (M_male = 4.39, SD = 0.60; M_female = 4.45, SD = 0.59; t = −1.045, p = 0.296).

Perceptions of earthquake awareness and risk were similar across genders. Males (M = 4.18, SD = 0.73) and females (M = 4.25, SD = 0.65) both demonstrated high personal awareness of earthquake danger (t = −1.133, p = 0.258). Agreement was lower on whether their community’s citizens are aware that a strong earthquake could occur (M_male = 3.49, SD = 0.99; M_female = 3.51, SD = 1.00; t = −0.216, p = 0.829). Respondents of both genders expressed limited confidence that local communities have implemented adequate protective measures (M_male = 2.35, SD = 1.12; M_female = 2.25, SD = 1.03; t = 1.138, p = 0.256) or that citizen training in disaster response is regularly organized (M_male = 2.02, SD = 0.97; M_female = 1.92, SD = 0.87; t = 1.190, p = 0.234).

Despite strong willingness to attend earthquake protection training (M_male = 4.51, SD = 0.68; M_female = 4.46, SD = 0.77; t = 0.927, p = 0.355), both genders were skeptical about improvements since the 1979 earthquake (M_male = 2.41, SD = 1.00; M_female = 2.40, SD = 0.98; t = 0.055, p = 0.956). Awareness of the earthquake’s impact on cultural heritage was similarly high (M_male = 4.10, SD = 0.80; M_female = 4.13, SD = 0.78; t = −0.432, p = 0.666).

Perceptions of institutional and governmental protection measures were consistent between genders. Men (M = 2.43, SD = 1.00) and women (M = 2.35, SD = 0.97) expressed low confidence that authorities adequately protect monuments during earthquakes (t = 0.916, p = 0.360). Both groups also perceived limited compliance with seismic construction regulations (M_male = 2.03, SD = 0.92; M_female = 1.93, SD = 0.83; t = 1.357, p = 0.175). Additionally, perceptions of institutional expertise and resources for seismic monument protection showed no significant gender difference (M_male = 2.45, SD = 1.00; M_female = 2.39, SD = 0.98; t = 0.719, p = 0.472).

Overall, the findings confirm that men and women share almost identical views on the cultural and social value of heritage and the importance of disaster risk reduction for earthquakes. Although the mean differences slightly favor men for heritage items and women for awareness statements, these differences are not statistically significant. The results show that both genders have high cultural awareness but consider institutional and community preparedness for seismic risks inadequate (

Table 4).

In the Independent Samples T-Test comparing place of residence (Boka Kotorska vs. Dubrovnik Littoral; N = 540), only two statements exhibited statistically significant differences. Respondents from Boka Kotorska expressed greater agreement that their local community organizes citizen training and education for earthquake response (M = 2.08, SD = 1.06) than those from the Dubrovnik Littoral (M = 1.86, SD = 0.74), t(≈478.66) = 2.827,

p = 0.005. Additionally, they showed greater agreement that seismic safety regulations are adhered to in new or reconstructed buildings (Boka Kotorska: M = 2.09, SD = 1.00; Dubrovnik Littoral: M = 1.87, SD = 0.71), t(≈486.34) = 2.968,

p = 0.003. All other items did not demonstrate statistically significant differences based on location (all p > 0.05) (

Table 5).

The Pearson correlation analysis between age and respondents’ views on cultural-historical monuments and seismic safety (see

Table 4) reveals several notable patterns. As age increases, appreciation for heritage also grows: older individuals are more likely to agree that preservation is vital (r = 0.249,

p = 0.001), that monuments serve as important tourist attractions (r = 0.158,

p = 0.001), and that they act as a national link connecting generations (r = 0.253,

p = 0.001).

Additionally, older respondents tend to see monuments as reflecting diverse cultural, civilizational, and religious influences (r = 0.248, p = 0.001) and believe they aid in understanding contemporary identity (r = 0.187, p = 0.001). Age also correlates positively with risk awareness: older participants report greater personal understanding of earthquake dangers (r = 0.365, p = 0.001) and perceive a higher community awareness of potential strong earthquakes (r = 0.145, p = 0.001). Knowledge of history aligns with this trend—older individuals are more familiar with the impact of the 1979 earthquake on monuments (r = 0.297, p = 0.001).

Conversely, age negatively influences proactive engagement and confidence in protection systems. Willingness to participate in earthquake preparedness training decreases with age (r = −0.195, p = 0.001), and older respondents are somewhat less convinced that the 1979 earthquake enhanced protection in their community (r = −0.094, p = 0.029*). They also show lower confidence that authorities sufficiently protect monuments during an earthquake (r = −0.135, p = 0.002**) and that institutions have enough expertise and resources for seismic safety (r = −0.109, p = 0.012*). Three items exhibit no significant correlation with age: perceived implementation of community safety measures (r = −0.044, p = 0.308), citizen training organization (r = 0.047, p = 0.278), and adherence to seismic building codes (r = 0.023, p = 0.594).

Older respondents exhibit stronger cultural values, greater risk awareness, and greater historical knowledge. Still, they are slightly less willing to engage in training and have lower trust in institutional and governmental seismic protection measures (

Table 6).

Education level consistently influences perceptions of heritage valuation and seismic safety. The ANOVA results show significant effects of education on various factors, including the importance of preservation (F = 35. 90, p = 0.00), monuments as tourist attractions (F = 37. 55, p = 0.00), and as a national resource (F = 29. 68, p = 0.00). It also affects views on monuments as records of diverse influences (F = 41. 41.72, p = 0.00), their role in understanding contemporary identity (F = 28. 28.83, p = 0.00), awareness of earthquake risks at home (F = 21. 91, p = 0.00), willingness to attend earthquake safety training (F = 23. 58, p = 0.00), and belief that the 1979 earthquake enhanced local protection (F = 3. 29, p = 0. 04). Additionally, familiarity with the earthquake’s impact on monuments (F = 31. 68, p = 0.00) and opinions on whether monuments are adequately protected (F = 4. 37, p = 0. 01) are influenced by education. No significant differences were found regarding perceptions of fellow- citizen awareness (p = 0. 09), community safety measures (p = 0. 76), citizen training organization (p = 0. 56), compliance with seismic laws in construction (p = 0. 08), or institutional seismic capacity (p = 0. 21). Welch and Brown- Forsythe tests support these results, especially where variance homogeneity is in question.

Descriptive data and Tukey post hoc tests reveal a clear trend: respondents with higher levels of education tend to agree more strongly with the importance of heritage and show greater awareness and preparedness for seismic risks. For instance, average scores increase with education for preservation (3. 79; 4. 49; 4. 76), monuments as tourist assets (3. 79; 4. 67; 4. 85), national resources (3. 79; 4. 35; 4. 64), and earthquake awareness (3. 64; 4. 08; 4. 42). The willingness to participate in earthquake safety training is also higher among more educated respondents (3. 21; 4. 51; 4. 52). Similarly, familiarity with the 1979 earthquake effects rises with education (3. 14; 3. 95; 4. 37). Conversely, higher education correlates with more critical views of institutional protection: ratings for adequate protection by authorities decrease as education increases (2. 64; 2. 49; 2. 25), and belief that the 1979 event resulted in increased safety measures is lower among the educated (2. 79; 2. 48; 2. 29). Overall, education correlates positively with attitudes favoring heritage preservation and disaster preparedness, while also fostering more critical evaluations of institutional learning and current safety measures (

Table 7).

3.3. Multiple Regression Analysis

The multiple regression analysis investigated if key sociodemographic factors—such as gender, residence, education level, and age—predict attitudes toward cultural heritage and seismic preparedness (see

Table 8). The overall model accounts for a small yet significant portion of the variance in the dependent variable (R² = 0.022; Adjusted R² = 0.015), explaining about 1.5% of the variance after adjusting for the number of predictors. Although the effect size is modest, the model is statistically significant (R = 0.149; F(4, 535) = 3.024,

p = 0.017; SE_est = 0.408), indicating that the predictors collectively influence respondents’ attitudes.

Among the variables, only education level shows a significant independent effect. Interestingly, higher education correlates with slightly lower scores on the attitude scale (B = −0.346, β = −0.134, t = −3.126, p = 0.002), with a 95% confidence interval from −0.563 to −0.129. This may suggest that more educated individuals are more critical and aware of risks when evaluating cultural heritage protection and seismic preparedness.

Conversely, gender, residence, and age do not significantly predict attitudes. Their coefficients are small, nonsignificant (all p > 0.32), and their confidence intervals cross zero, implying these factors are not meaningful in explaining variation in preparedness attitudes within this sample.

All predictors show low multicollinearity (VIF ≈ 1), indicating stable parameter estimates and no redundancy among variables. However, the small amount of variance explained highlights that attitudes toward cultural heritage and seismic readiness are likely influenced by other psychosocial or contextual factors not included in this model, such as risk perception, past disaster experience, institutional trust, or cultural values.

Overall, the findings suggest that higher educational levels are associated with more cautious or critical views on heritage protection and seismic preparedness, whereas fundamental demographic factors have limited influence. Future research should include additional cognitive and experiential variables to understand better what drives these attitudes, especially in regions prone to seismic activity and rich in cultural heritage.

4. Discussions

The findings largely confirm a dual reality in the Bay of Kotor and the Dubrovnik Littoral: a strong cultural attachment to monuments exists alongside limited confidence in seismic preparedness and protection systems. These findings are consistent with previous research showing that cultural heritage in seismically active coastal regions faces growing threats from climate change, rapid urbanization, and increased human pressures, which collectively elevate disaster risks (Cvetković et al., 2024; Grozdanić et al., 2024; Shi et al., 2015). Regarding the first hypothesis (low awareness), results are mixed. While personal awareness of earthquake risks is high (M ≈ 4.22) and increases with age (r = 0.365, p = 0.001), knowledge of the 1979 earthquake’s effects is also significant (M ≈ 4.11; r = 0.297, p = 0.001). However, community awareness is perceived as moderate (M ≈ 3.50), with the lowest scores for organized citizen training (M ≈ 1.97) and practical local protective measures (M ≈ 2.30). Therefore, H1 is partly supported: individuals are aware, but community-level awareness is fragmented and poorly translated into systematic preparedness. Similar findings were reported in regional studies, highlighting that fragmented institutional capacities and weak public risk communication hinder local seismic resilience in Montenegro and Croatia (Grozdanić et al., 2024; Cvetković et al., 2024). Also practices are present around the world, individuals are partially or fully informed about earthquake hazards, but the community and system are not strong enough to take adequate measures to protect cultural and historical heritage (Sutrisn et al., 2025; Santangelo et al., 2022; Ginzarly & Teller, 2025).

On the other side, the second hypothesis (insufficient protection/restoration measures) receives strong support. Respondents lack confidence that authorities adequately protect monuments during earthquakes (M ≈ 2.39) or that they possess sufficient expertise and resources (M ≈ 2.42). Perceptions of compliance with seismic building regulations are also low (M ≈ 1.98). ANOVA results by education level show that heritage valuation increases with education. However, more educated respondents are more critical of institutional capacity, reflected in lower scores for “adequate protection” and skepticism about lessons from 1979 improving safety. The t-test by residence reveals only two significant differences: Boka Kotorska perceives more training and better code adherence, indicating that while some areas show stronger perceptions, overall institutional capacity is seen as weak in both regions. This reinforces international evidence from Italy, Turkey, China, and Nepal, where major earthquakes have repeatedly demonstrated the extreme vulnerability of unreinforced historic masonry and the consequences of delayed retrofitting interventions (Boyoğlu et al., 2023; Zhu et al., 2023; Longobardi & Formisano, 2022). Additionally, despite the availability of engineering tools such as perpetuate guidelines and vulnerability indexing, their application in heritage environments remains limited, thereby affecting the effectiveness of risk mitigation (Lagomarsino & Cattari, 2014; Formisano & D’Amato, 2021).

When we analyze the third hypothesis (demographic influences), it receives partial support. Analyze the third hypothesis, which is non-significant across all statements (all p > 0.05), indicating a broad consensus across genders on the importance of heritage and related aspects of risk. Conversely, age and education play significant roles. Age shows a positive correlation with heritage valuation and risk awareness (e.g., preservation, r = 0.249; tourist value, r = 0.158; personal risk awareness, r = 0.365; all p = 0.001), but a negative correlation with willingness to attend training (r = −0.195, p = 0.001) and confidence in institutional protection. Education influences responses in ANOVA for many items (e.g., preservation, F = 35.90, p < 0.01; tourist value, F = 37.55, p < 0.01; awareness, F = 21.91, p < 0.01). In the multiple regression analysis of the composite “Cultural-Heritage and Seismic Preparedness Attitudes,” education is the only significant predictor (B = −0.346, β = −0.134, p = 0.002), indicating that higher education correlates with higher standards and greater skepticism towards institutions. Place of residence has limited effects (only two items), and gender shows no effect. These demographic patterns mirror international studies, in which education significantly shapes preparedness attitudes, while gender differences in cultural-heritage risk perception remain negligible in European seismic contexts (Narita et al., 2016; Taffarel et al., 2018).

The literature increasingly emphasizes that community engagement with cultural heritage can strengthen disaster resilience; however, operational models that translate heritage perception into earthquake preparedness remain underdeveloped in practice (Appleby-Arnold et al., 2020; Fabbricatti et al., 2020). It is emphasized that the possibilities are great, but that the mechanisms are still under development — awareness is present, but the challenge is to translate it into concrete action models. (Fabbricatti et al., 2020; Ginzarly & Teller, 2025). Demir & Turan (2025) address post-earthquake interventions in historic urban areas—looking at how reconstruction, shared memories, traditions, and shared participation can be integrated into heritage restoration. Although the focus is on the post-disaster period, rather than directly on preparedness before an earthquake, the same challenge emerges: mechanisms exist but are often reactive (repair, reconstruction) rather than preventive and systematic.Cultural and historical heritage has the potential to strengthen resilience, but practice is often fragmented and requires new governance mechanisms and cooperation between different actors (e.g., local communities + institutions) to translate community awareness into systematic preparedness. Based on the results, transforming high cultural pride into readiness would require establishing regular community training sessions, such as annual drills and museum or school workshops, and publicly monitoring participation. Second, improve the transparency of code enforcement activities, including inspections, certifications, and sanctions, to build trust. Third, focus on risk communication that is tailored to different age groups: younger people are more willing to engage, while older people have greater awareness but less interest in training, so create short, easy-to-understand formats for them. Fourth, integrate heritage-specific seismic retrofitting guidelines that align with conservation principles, and test them at key sites to demonstrate their practicality. Fifth, formalize collaboration among sectors by establishing standing working groups that involve heritage, civil protection, and local government, with shared indicators and clear, transparent reporting.

The cross-sectional approach restricts the ability to draw causal conclusions; self-reports might also be biased by social desirability or recall issues. The relatively low variance explained in the regression suggests that factors such as prior training, building stock condition, and enforcement of local policies are likely more influential and should be directly measured. Future research should integrate surveys with administrative data on training frequency, inspection records, retrofit investments, and damage or risk assessments. Longitudinal studies could help monitor changes following interventions. Overall, the findings support targeted, scalable strategies to bridge the gap between cultural appreciation and practical seismic preparedness in both regions.

The recommendations below translate the study’s empirical findings into practical actions for heritage authorities, civil protection agencies, and local governments. Each point links a specific challenge with related evidence from our data and outlines targeted interventions to enhance preparedness, enforcement, and community capacity. Implementing these measures—especially those that combine conservation principles with seismic engineering, transparent code enforcement, and customized public education—should significantly reduce risks to heritage assets while fostering trust and engagement among stakeholders (

Table 9).