1. Introduction

The fresh-cut fruit and vegetable industry has experienced remarkable economic expansion in recent years, showing an annual growth rate of approximately 5–10% over the past decade. Lettuce-based products alone account for nearly 50% of this market segment. However, tissue browning remains one of the most critical physiological disorders limiting the visual quality and consumer acceptance of fresh-cut lettuce [

1] (Charles et al., 2018). Although enzymatic discoloration at cut surfaces is part of the plant’s natural wound-healing response, the development of pink or brown hues is perceived by consumers as a visual defect and a sign of deterioration [

2] (Peng and Simko, 2023).

Cutting operations trigger the oxidation of phenolic compounds by polyphenol oxidase (PPO), resulting in tissue browning and rapid quality degradation. Mechanical injury accelerates respiration and enzymatic activity, significantly shortening shelf life. To mitigate browning and preserve postharvest quality, several chemical and physical strategies have been explored, including reducing agents, enzyme inhibitors, modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) systems [

3] (Choi et al., 2021), heat treatments, ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, and continuous or intermittent light exposure. In recent years, environmentally sustainable alternatives such as salicylic acid (SA) and calcium (Ca) treatments have gained increasing attention due to their effectiveness and low chemical residue concerns.

Salicylic acid is a naturally occurring phenolic signaling molecule that plays a pivotal role in regulating plant growth, development, and defense responses to both biotic and abiotic stresses [

4] (Morillo et al., 2025). During the postharvest period, SA has been shown to delay senescence and softening by modulating multiple physiological and biochemical pathways and enhancing antioxidant activity [

5] (Abdelkader et al., 2022). Nawarathna and Eeswara [

6] (2025) reported that applying 100 mg L⁻¹ SA to lettuce effectively maintained higher levels of phenolic compounds and reduced deterioration after seven days of storage at 4°C.

Similarly, exogenous calcium treatments are widely used to preserve tissue firmness in fresh-cut produce. Calcium strengthens cell wall integrity by cross-linking pectin molecules in the middle lamella, forming calcium pectates that maintain cellular cohesion. Consequently, calcium application helps preserve firmness, minimize chlorophyll and protein degradation, and delay tissue senescence during storage [

7] (De Corato, 2020). Morillo et al. [

4] (2025) further demonstrated that applying 2% CaCl₂ + 2 mM SA significantly reduced weight loss in minimally processed lettuce, whereas CaCl₂ alone effectively delayed the decline in total Chl and vitamin C content.

Recently, nano-sized calcium formulations have emerged as promising alternatives to conventional calcium salts. Cid-López et al. [

8] (2021) reported that calcium nanoparticles (CaNPs) enhanced surface brightness, reduced weight loss, and maintained the physicochemical and visual quality of cucumber fruits. Similarly, the combined application of 2 mM CaNPs and SA minimized weight loss and electrolyte leakage, thereby maintaining overall postharvest quality [

5] (Abdelkader et al., 2022). Despite these advances, studies examining the effects of SA and CaNPs on fresh-cut lettuce remain limited, and no research has yet investigated their combined effects.

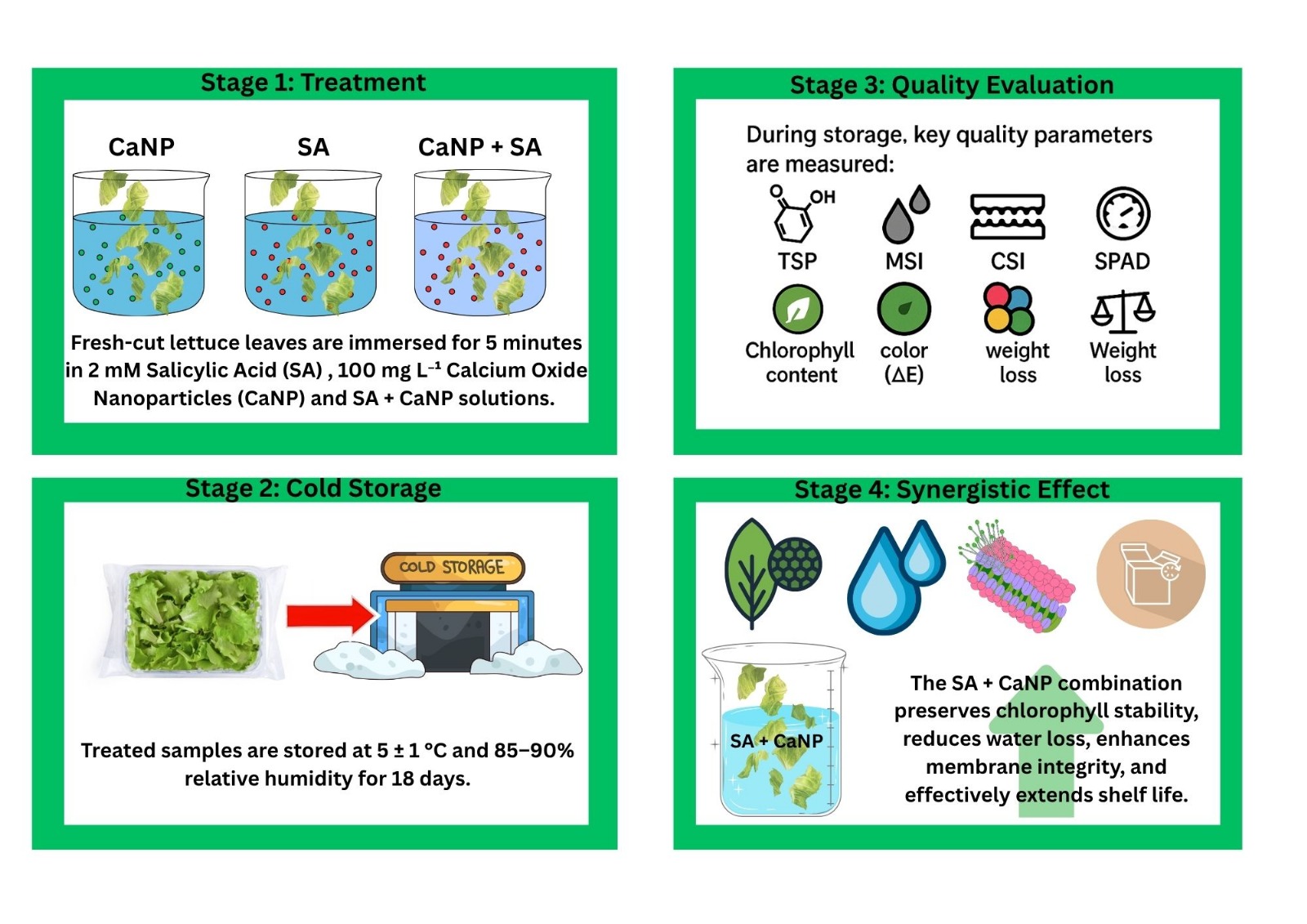

The present study aimed to evaluate the individual and synergistic effects of salicylic acid and calcium nanoparticles on the visual and biochemical quality attributes of fresh-cut lettuce during storage at 5°C. This work represents one of the first attempts to elucidate the combined influence of SA and CaNPs on minimally processed lettuce and provides novel insights into their potential to enhance quality retention and extend shelf life in fresh-cut vegetables.

2. Materials and Methods

Plant Material

In this study, the curly lettuce (

Lactuca sativa L. var.

crispa) cultivar was used as the plant material. The lettuce plants were grown under soilless culture conditions using the deep flow technique (DFT) hydroponic system. A nutrient solution specifically formulated for lettuce, whose composition is presented in

Table 1, was used throughout the cultivation period. During the experiment, the pH of the nutrient solution was maintained at 6.5 by adjusting with diluted hydrochloric acid (HCl).

Chemicals Used

In this study, calcium oxide nanoparticles (CaNP) with a purity of 99.95% and a particle size range of 10–70 nm were obtained from PARS Chemical Co. (Turkiye). Salicylic acid (SA) with 99% purity (CAS No: 69-72-7; EC No: 200-712-3) was used for the treatments.

Fresh-Cutting Process and Treatments

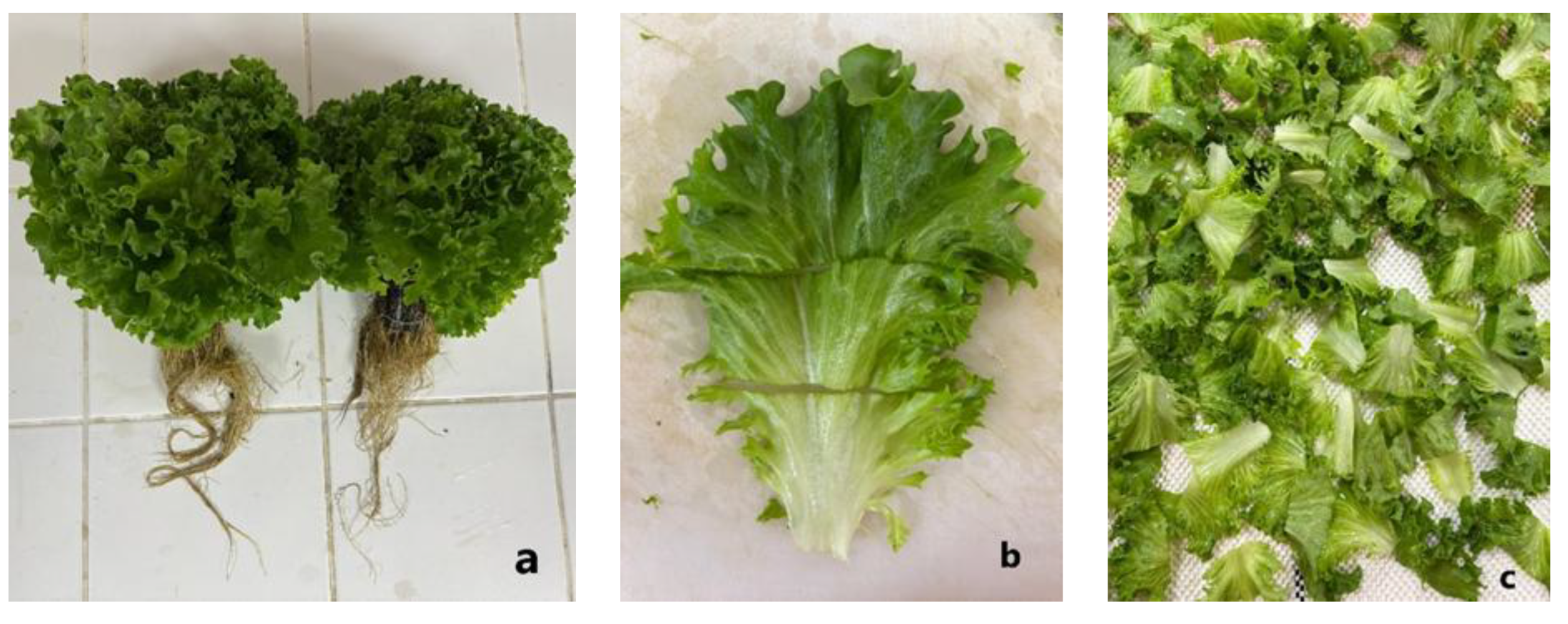

After harvest, the lettuce heads were immediately transported to the laboratory. The outer yellowish leaves at the basal part of the plants were carefully removed (

Figure 1a). Subsequently, the outer leaves surrounding the developing inner leaves were transversely cut at approximately 4 cm intervals (

Figure 1b). Following the cutting process, the lettuce leaves were subjected to the treatments described below and then air-dried at room temperature (

Figure 1c).

Table 2.

Description of postharvest treatments applied to fresh-cut lettuce samples prior to cold storage.

Table 2.

Description of postharvest treatments applied to fresh-cut lettuce samples prior to cold storage.

| Treatment |

: |

Description |

| Control (C) |

: |

Fresh-cut lettuce leaves were immersed in tap water for 5 min and then air-dried at room temperature. |

| Salicylic acid (SA) |

: |

Fresh-cut lettuce leaves were immersed in 2 mM SA solution for 5 min and then air-dried at room temperature. |

| Calcium Nanoparticle (CaNP) |

: |

Fresh-cut lettuce leaves were immersed in 100 mg L⁻¹ CaNP solution for 5 min and then air-dried at room temperature. |

| SA+CaNP |

: |

Fresh-cut lettuce leaves were immersed in a combined solution containing 2 mM SA and 100 mg L⁻¹ CaNP for 5 min and then air-dried at room temperature |

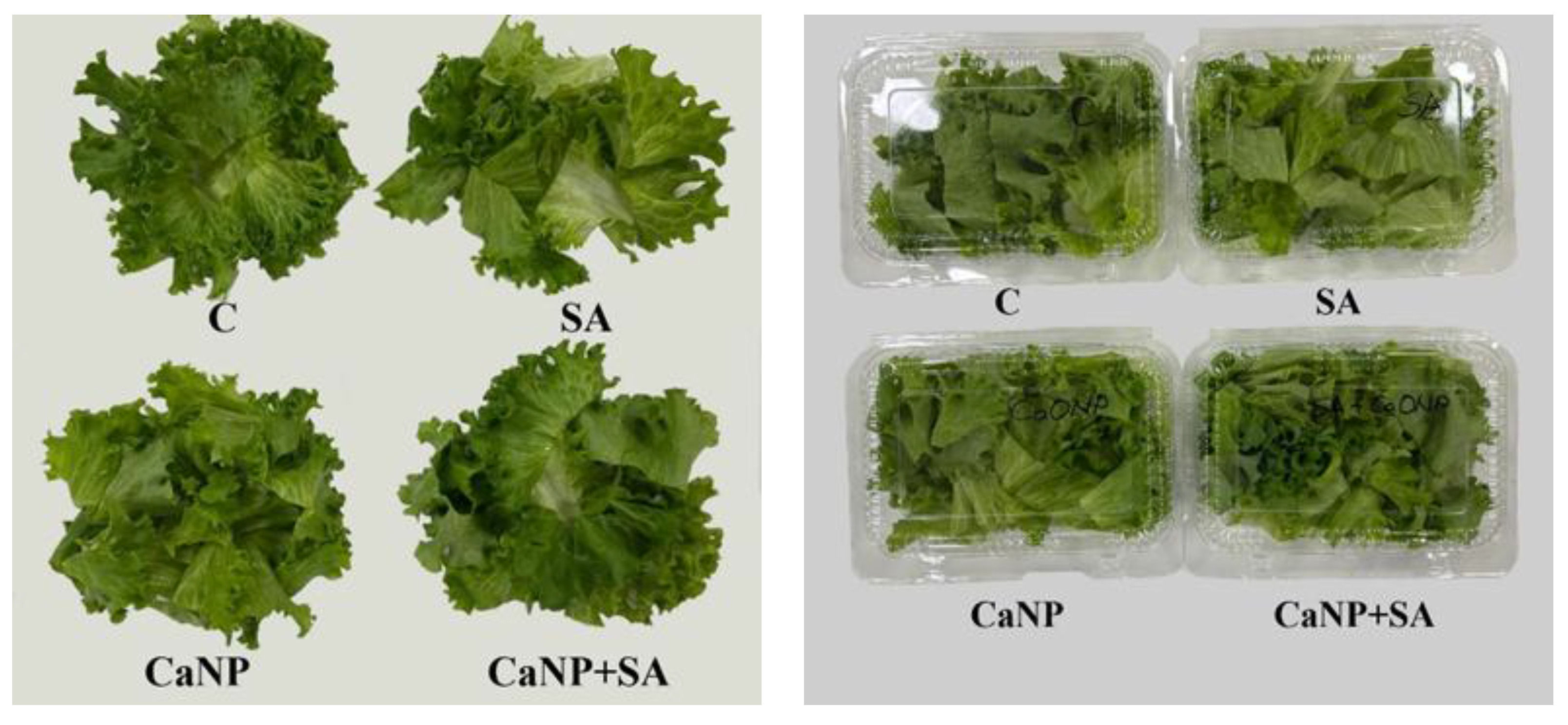

Packaging and Cold Storage Conditions

After air-drying at room temperature, fresh-cut lettuce leaves from all treatments were placed into lidded PET containers (dimensions: 8.5×9.0×6.5 cm), each containing 50 g of sample (

Figure 2). The containers were then stored in a cold room at 5±1°C and 85–90% relative humidity for 18 days. During the storage period, samples were taken on days 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 for subsequent quality analyses.

Total Soluble Phenolic Content (TSP)

After extracting the juice from the lettuce leaves, 150 µL of the extract was mixed with 2400 µL of distilled water and 150 µL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (1:10 dilution). The mixture was vortexed for 30–40 s and allowed to stand for 4 min. Subsequently, 300 µL of 1 N sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) was added, and the samples were incubated for 2 h at room temperature in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 725 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. The total phenolic content was expressed as mg caffeic acid equivalent (CAE) per 100 mL of extract [

10] (Chavez-Santiago et al., 2021).

Membrane Stability Index (MSI)

The Membrane Stability Index (MSI) was determined to assess the degree of cell membrane injury caused by freezing–thawing stress, based on the method described by Nabati et al. [

11] (2023). Leaf discs were taken from each treatment and rinsed twice with 50 mL of distilled water. The samples were then incubated in 50 mL of distilled water for 2 h at room temperature, and the initial electrical conductivity (C₁) was recorded. Subsequently, the samples were frozen at –18°C for 24 h, thawed at room temperature, and when the solution temperature exceeded 18°C, the second conductivity (C₂) was measured. The MSI (%) was calculated using the following formula:

The obtained MSI values were evaluated as an indicator of membrane permeability. Higher MSI values indicate better preservation of membrane integrity, while lower values correspond to increased membrane injury. All measurements were conducted in triplicate, and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Cutting Resistance (N)

To evaluate the effect of treatments on maintaining leaf turgor at the beginning and throughout the storage period, the cutting resistance of fresh-cut lettuce leaves was measured. For each replicate, three leaf samples were analyzed using a texture analyzer (Shimadzu EZ-LX, Shimadzu Corp., Japan) equipped with a Warner–Bratzler cutting blade. The force required to cut the leaf surface was recorded in Newtons (N) and used as an indicator of tissue firmness or crispness.

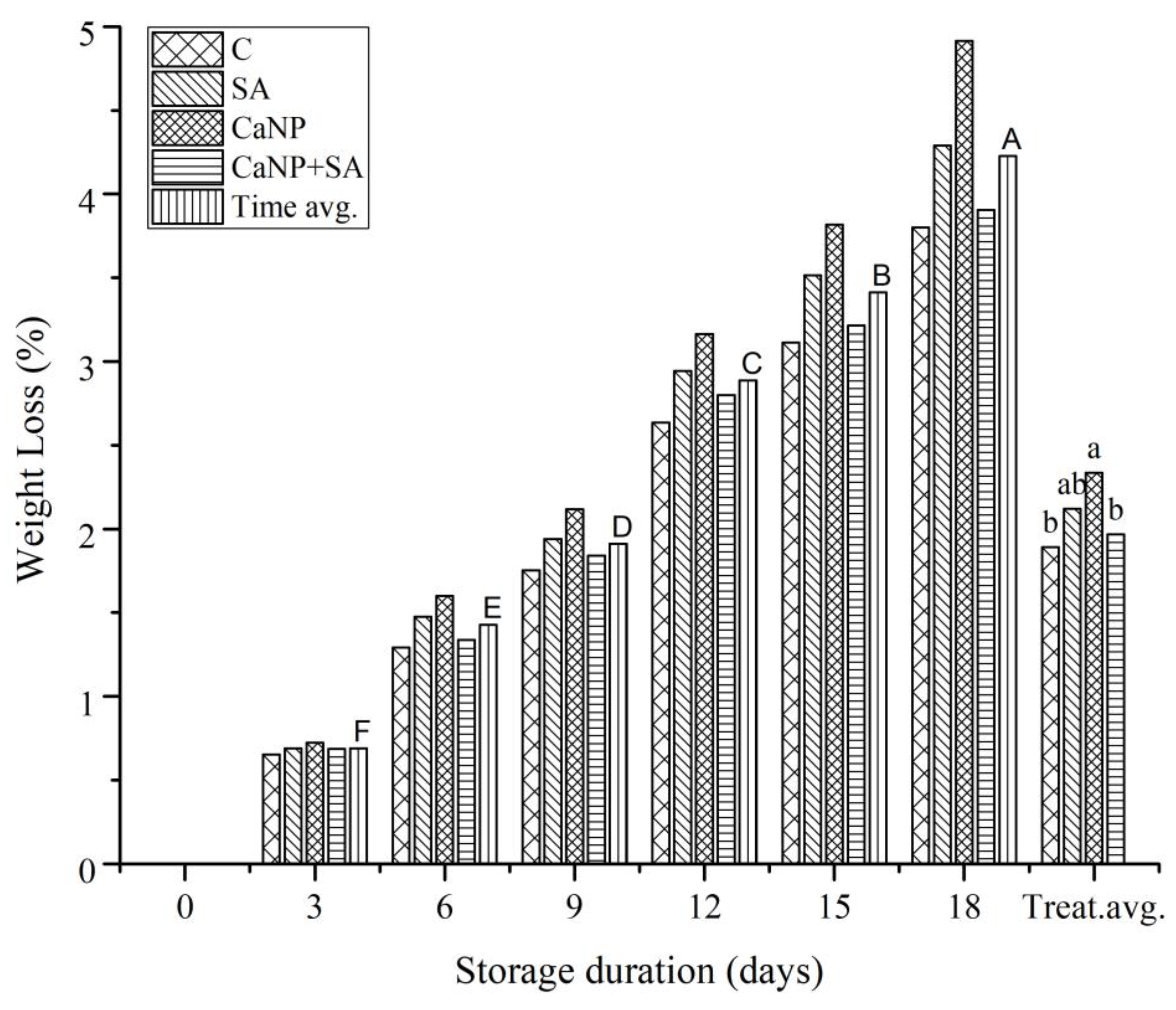

Weight Loss (%)

Weight measurements were performed on the same samples at each sampling interval for all treatments. The percentage of weight loss during storage was calculated using the following equation:

where W₀ is the initial sample weight and Wₜ is the sample weight at each storage interval.

Total Soluble Solids (TSS) Content

For the determination of total soluble solids (TSS), juice extracted from lettuce leaves of each treatment group was analyzed using a digital refractometer (Atago Co., Ltd., Japan). The TSS content was expressed as a percentage (%).

Chlorophyll a, b, and Total Chlorophyll Content

Fresh lettuce samples (0.5 g) were homogenized with 10 mL of 80% acetone. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected for analysis. Absorbance was measured at 645 nm and 663 nm using a spectrophotometer, and the chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll contents were calculated using the equations described by Ngcobo et al. [

12] (2024).

The chlorophyll (chl-a, chl-b and total chl) concentration (mg g⁻¹ FW) was calculated using the absorbance readings obtained from the spectrophotometer according to the following equation:

where: C represents the chlorophyll (Chl)

a, Chl

b, and total Chl content (mg g⁻¹ FW), V is the volume of extract (L), and FW denotes the fresh weight of the sample (g).

Chlorophyll Stability Index (CSI, %)

The Chlorophyll Stability Index (CSI) was determined to evaluate the extent of degradation of chlorophyll pigments during the postharvest storage period, following the method of Ngcobo et al. [

12] (2024). The CSI was calculated based on the difference between the chlorophyll content of freshly cut samples and those measured at each storage interval (3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 days). A higher CSI value indicates greater chlorophyll stability and, consequently, better maintenance of green color during storage.

Relative Chlorophyll Content (SPAD)

The relative chlorophyll content of fresh-cut lettuce was determined using a SPAD-502 Plus chlorophyll meter (Konica Minolta, Inc., Osaka, Japan). Measurements were taken from one point on each of five leaves per replicate, and the mean SPAD value was recorded for each treatment.

Color Measurements

The surface color of lettuce leaves was measured using a colorimeter (Minolta CR-400, Minolta Co., Osaka, Japan). Measurements were taken from the adaxial surface of five leaf samples per replicate, and color parameters were expressed as L* (lightness), a* (red–green), and b* (yellow–blue) values. Based on these primary color coordinates, hue angle (°), Chroma (C), total color difference (ΔE), and yellowness index (YI) were calculated using the following equation:

where: L* (lightness), a* (red–green), and b* (yellow–blue) values.

Statistical Analysis

The experiment was conducted in a completely randomized design (CRD) with three replicates. For each replicate, three packages of fresh-cut lettuce were used, and each package contained a constant weight of 50 g of lettuce leaves. The obtained data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using SPSS software version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences among treatment means were determined using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT) at a significance level of p<0.05. Additionally, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Pearson correlation analyses were performed using Python software (v.3.13) to evaluate the relationships among quality parameters and treatment effects throughout the storage period.

4. Conclusions

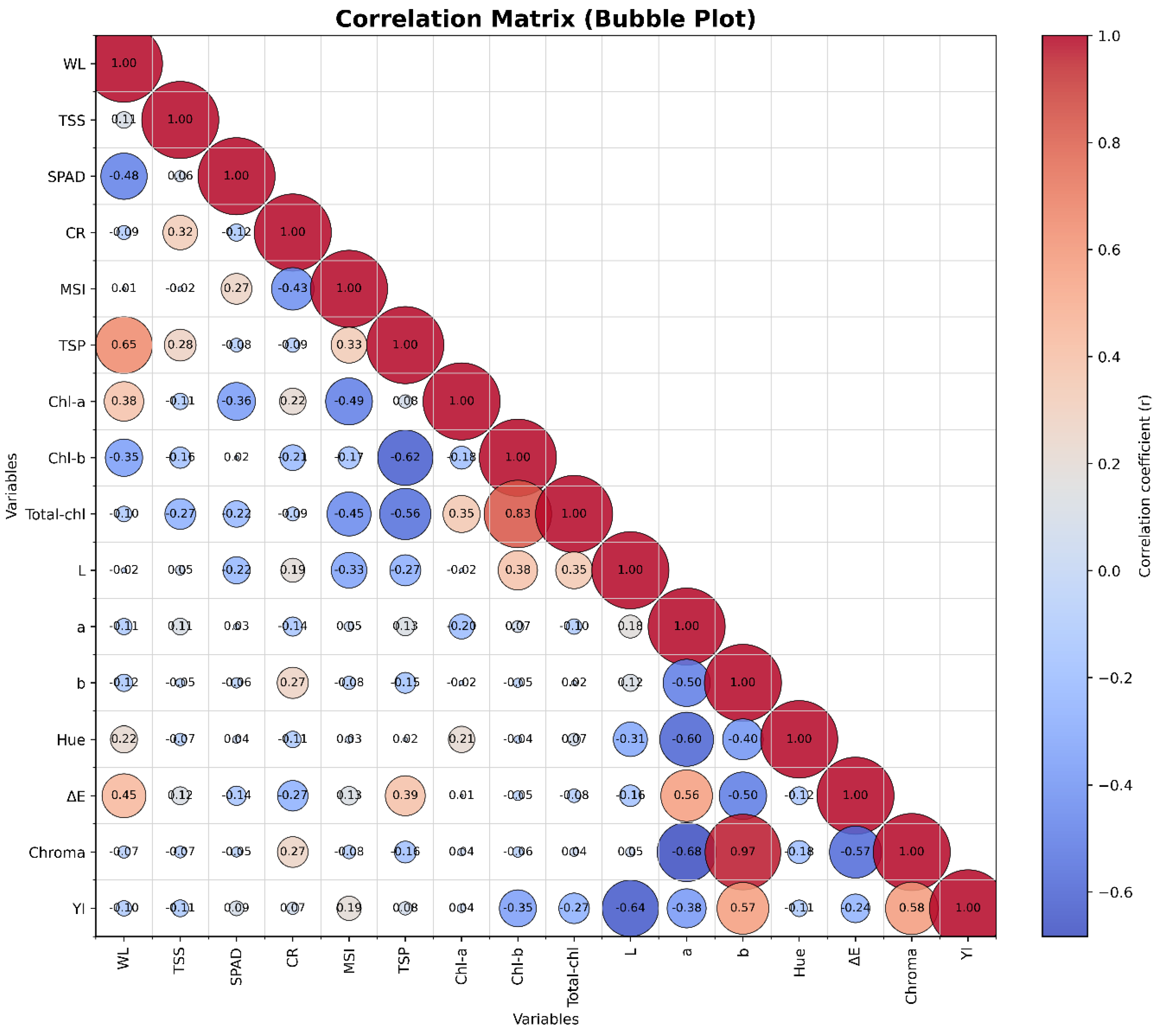

This study demonstrated that the application of 2 mM salicylic acid (SA) and 100 mg L⁻¹ calcium oxide nanoparticles (CaNP) effectively preserved the physiological and biochemical quality of fresh-cut lettuce during 18 days of cold storage. Treatments with SA and CaNP + SA maintained higher total soluble phenolic contents, thereby limiting oxidative degradation, while preserving chlorophyll pigments, SPAD values, and the chlorophyll stability index (CSI) to ensure color integrity and photosynthetic stability. The CaNP + SA combination showed the lowest weight loss and the highest membrane stability index (MSI), indicating improved membrane integrity and reduced cellular water loss. Positive correlations among SPAD, CSI, and MSI, along with their negative correlations with weight loss and cutting resistance, confirmed that these treatments maintained tissue elasticity and water balance throughout storage. Overall, the combined use of SA and CaNP effectively supported membrane stabilization, pigment preservation, and water retention, slowing postharvest deterioration in fresh-cut lettuce. This combination emerges as a promising postharvest strategy to extend shelf life and maintain both the visual and physiological quality of minimally processed leafy vegetables.

The findings of this study clearly demonstrate that the application of 2 mM SA and 100 mg L⁻¹ CaNP, either individually or in combination, effectively preserved the physiological, biochemical, and visual quality of fresh-cut lettuce during 18 days of cold storage at 5±1 °C.Both SA and CaNP+SA treatments markedly reduced postharvest senescence and oxidative damage by maintaining higher levels of TSP, which are closely associated with the antioxidant defense system and phenylpropanoid metabolism. The combination of both treatments (CaNP+SA) provided the most balanced protection, reflected by the lowest weight loss, the highest MSI, and the greatest CSI, suggesting enhanced cellular integrity and delayed pigment degradation.

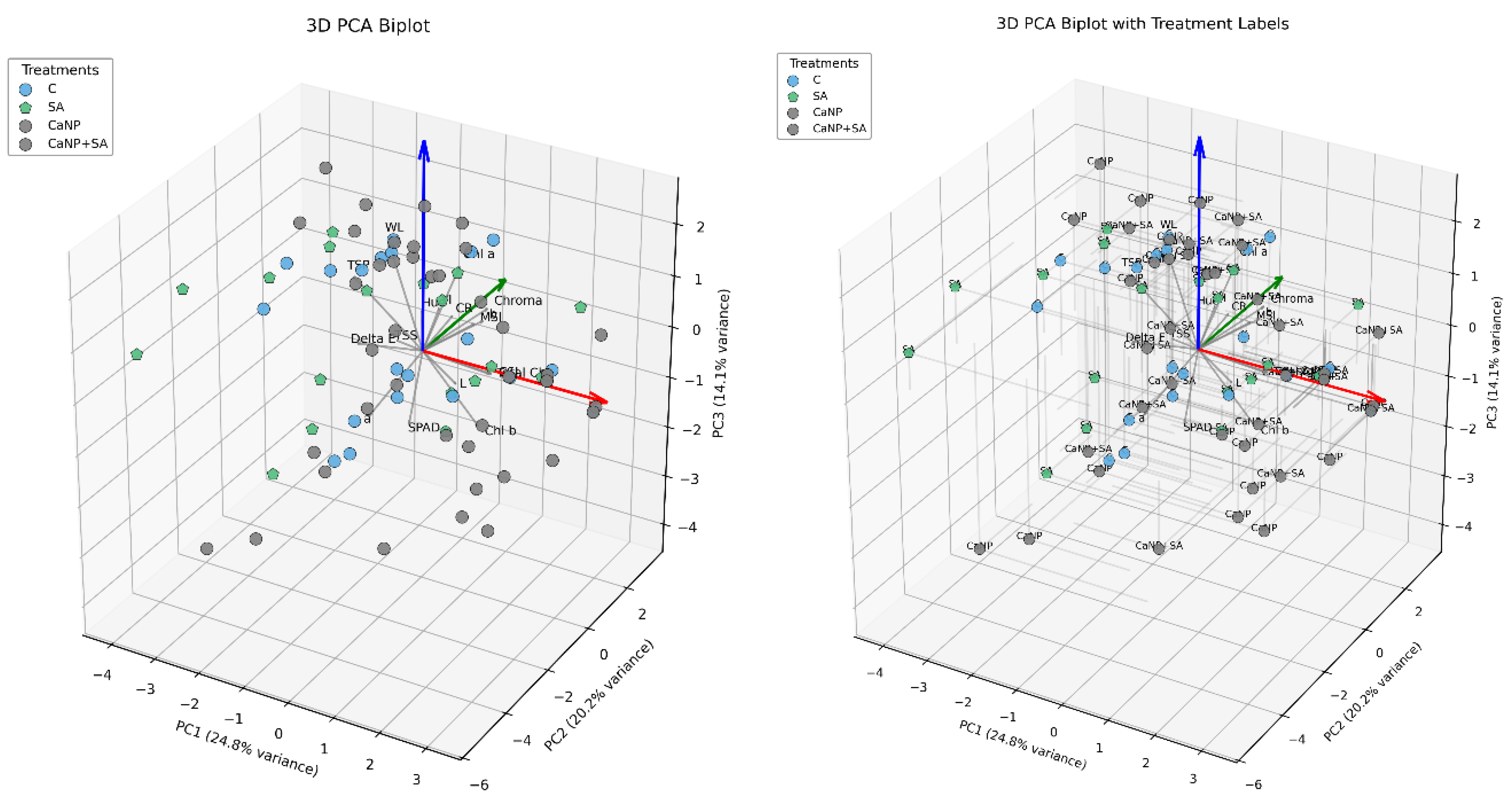

Strong positive correlations among SPAD, CSI, and MSI, coupled with their negative correlations with weight loss and cutting resistance, confirmed that these treatments maintained tissue elasticity, water retention, and pigment stability throughout storage. The synergistic interaction between CaNP and SA appears to strengthen membrane structure and reduce electrolyte leakage, thereby improving the lettuce’s ability to resist chilling-induced oxidative stress. Principal component analysis (PCA) supported these findings, showing that SA and CaNP+SA treatments clustered together near variables related to pigment stability and antioxidant capacity, whereas CaNP alone was associated more closely with mechanical resistance parameters.

Overall, the combined use of SA and CaNP successfully delayed chlorophyll degradation, mitigated water loss, and preserved phenolic integrity, leading to prolonged shelf life and improved postharvest performance. This integrated treatment strategy may represent a practical and eco-friendly approach to maintaining the physiological and sensory quality of minimally processed leafy vegetables, offering promising potential for sustainable postharvest management in the fresh-cut produce industry.

Figure 1.

Appearance of lettuce samples: (a) Harvesting, (b) Cutting process, (c) Air-drying process.

Figure 1.

Appearance of lettuce samples: (a) Harvesting, (b) Cutting process, (c) Air-drying process.

Figure 2.

Packaging of fresh-cut lettuce samples in lidded PET containers prior to cold storage.

Figure 2.

Packaging of fresh-cut lettuce samples in lidded PET containers prior to cold storage.

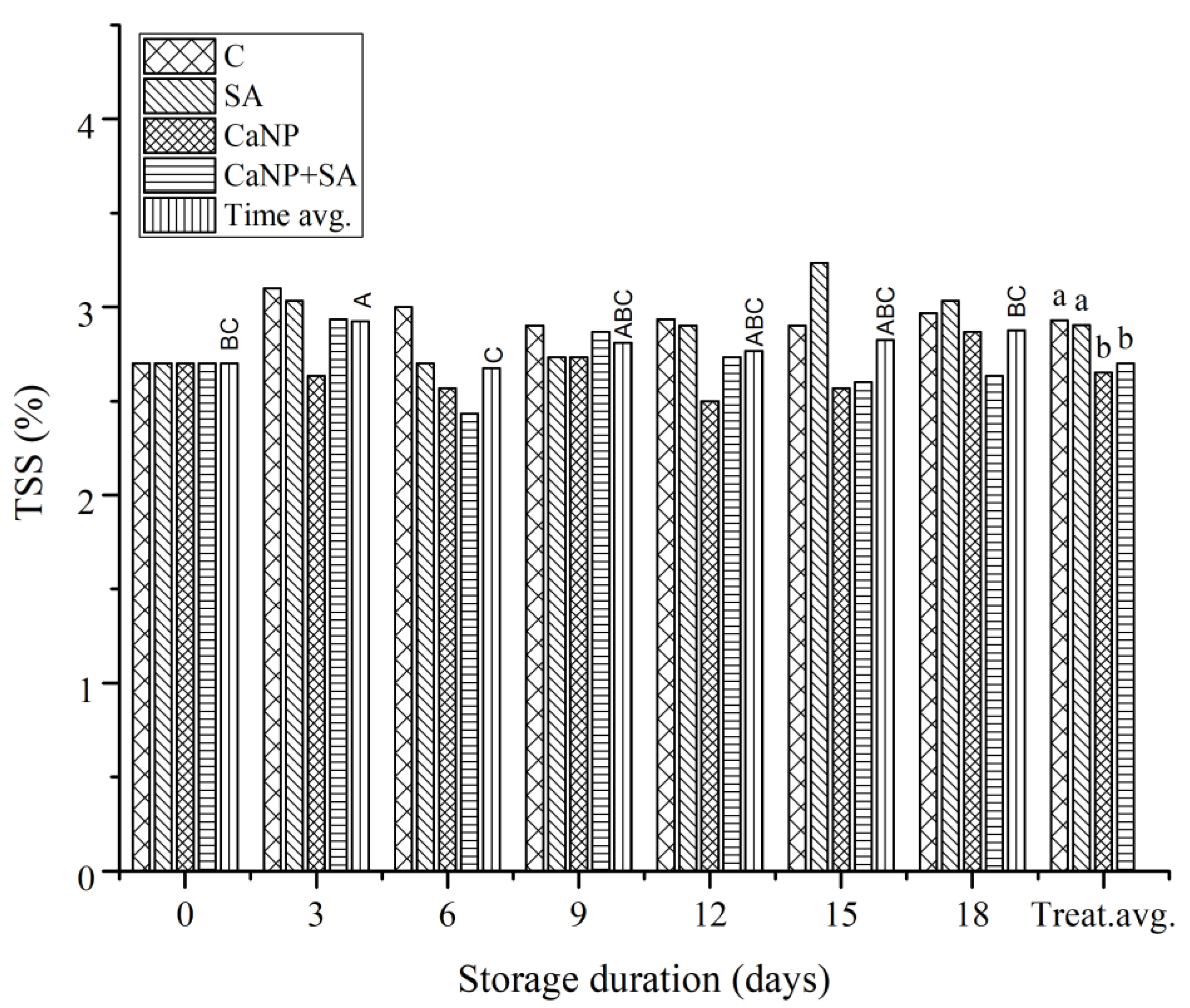

Figure 4.

Changes in TSS (%) of fresh-cut lettuce as influenced by calcium nanoparticles (CaNP) and salicylic acid (SA) treatments during cold storage (4±1 °C). Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among storage days (p<0.05), and different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p<0.05) according to DMRT (n = 3).

Figure 4.

Changes in TSS (%) of fresh-cut lettuce as influenced by calcium nanoparticles (CaNP) and salicylic acid (SA) treatments during cold storage (4±1 °C). Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among storage days (p<0.05), and different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among treatments (p<0.05) according to DMRT (n = 3).

Figure 5.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) biplot showing the relationships among quality parameters of fresh-cut lettuce subjected to different treatments (Control, SA, CaNP, CaNP+SA) during 18 days of cold storage. The PCA model explained 59.18% of the total variance (PC1: 24.8%, PC2: 20.2%, PC3: 14.1%). Vectors pointing in the same direction indicate strong positive correlations among variables such as SPAD, Chl a, Chl b, Total Chl, CSI, and MSI, while opposite directions represent negative relationships with weight loss (WL) and cutting resistance (CR). SA and CaNP+SA treatments were clustered close to stability-related parameters, indicating improved pigment and membrane integrity compared to other treatments.

Figure 5.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) biplot showing the relationships among quality parameters of fresh-cut lettuce subjected to different treatments (Control, SA, CaNP, CaNP+SA) during 18 days of cold storage. The PCA model explained 59.18% of the total variance (PC1: 24.8%, PC2: 20.2%, PC3: 14.1%). Vectors pointing in the same direction indicate strong positive correlations among variables such as SPAD, Chl a, Chl b, Total Chl, CSI, and MSI, while opposite directions represent negative relationships with weight loss (WL) and cutting resistance (CR). SA and CaNP+SA treatments were clustered close to stability-related parameters, indicating improved pigment and membrane integrity compared to other treatments.

Figure 6.

Correlation matrix (bubble plot) illustrating Pearson correlation coefficients among physicochemical and physiological parameters of fresh-cut lettuce stored for 18 days under different treatments. Positive correlations are indicated in red and negative in blue. Strong positive associations were observed among SPAD, Chl-a, Chl-b, Total-chl, CSI, and MSI (r > 0.70), whereas weight loss (WL) and cutting resistance (CR) showed significant negative correlations with these parameters (r < –0.50). The results confirm the consistency between PCA and correlation analysis in identifying the synergistic effects of SA and CaNP+SA treatments on maintaining leaf quality.

Figure 6.

Correlation matrix (bubble plot) illustrating Pearson correlation coefficients among physicochemical and physiological parameters of fresh-cut lettuce stored for 18 days under different treatments. Positive correlations are indicated in red and negative in blue. Strong positive associations were observed among SPAD, Chl-a, Chl-b, Total-chl, CSI, and MSI (r > 0.70), whereas weight loss (WL) and cutting resistance (CR) showed significant negative correlations with these parameters (r < –0.50). The results confirm the consistency between PCA and correlation analysis in identifying the synergistic effects of SA and CaNP+SA treatments on maintaining leaf quality.

Table 1.

The chemical composition and concentrations of the nutrient solution used for hydroponic lettuce cultivation under deep flow technique (DFT) conditions [

9] (Hoagland and Arnon, 1954).

Table 1.

The chemical composition and concentrations of the nutrient solution used for hydroponic lettuce cultivation under deep flow technique (DFT) conditions [

9] (Hoagland and Arnon, 1954).

| Concentration |

Source |

| 5 mM |

Calcium nitrate tetrahydrate [Ca(NO₃)₂·4H₂O] |

| 5 mM |

Potassium nitrate (KNO₃) |

| 2 mM |

Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (MgSO₄·7H₂O) |

| 1 mM |

Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH₂PO₄) |

| 45.5 µM |

Boric acid (H₃BO₃) |

| 44.7 µM |

Ferrous sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO₄·7H₂O) |

| 30.0 µM |

Sodium chloride (NaCl) |

| 9.1 µM |

Manganese sulfate monohydrate (MnSO₄·H₂O) |

| 0.77 µM |

Zinc sulfate heptahydrate (ZnSO₄·7H₂O) |

| 0.32 µM |

Copper sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO₄·5H₂O) |

| 0.10 µM |

Ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate [(NH₄)₆Mo₇O₂₄·4H₂O] |

| 54.8 µM |

Disodium EDTA dihydrate (Na₂EDTA·2H₂O) |

Table 3.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the effects of treatment, storage time, and their interaction (Treatment × Time) on the physicochemical and physiological quality parameters of fresh-cut lettuce during 18 days of cold storage.

Table 3.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for the effects of treatment, storage time, and their interaction (Treatment × Time) on the physicochemical and physiological quality parameters of fresh-cut lettuce during 18 days of cold storage.

| Parameter |

Treatment |

Time |

Treatment × Time |

| Total soluble phenolics (TSP) |

100.236*** |

4318.678*** |

61.724*** |

| Membrane stability index (MSI) |

17.099*** |

43.033*** |

2.876** |

| Cutting resistance (CR) |

22.30*** |

9.108** |

1.733ns

|

| Weight loss (WL) |

5.731**4 |

197.426*** |

0.665ns

|

| Total soluble solids content (TSS) |

9.265*** |

2.171ns

|

1.533ns

|

| Chlorophyll a (Chl a) |

5.572** |

176.179*** |

8.617*** |

| Chlorophyll b (Chl b) |

5.844** |

34.946*** |

3.088*** |

| Total Chlorophyll (Total Chl) |

8.895*** |

41.024*** |

4.917*** |

| Chlorophyll stability index (CSI) |

5.944** |

764.772*** |

2.886** |

| Relative chlorophyll content (SPAD) |

25.176*** |

107.225*** |

17.844*** |

| Color coordinates (L, a, b) |

13.189*** |

20.797*** |

7.653*** |

| Hue angle (hue) |

2.944* |

2.215* |

1.326* |

| Color difference (ΔE) |

2.646ns

|

13.583*** |

5.082*** |

| Color saturation (Choma) |

1.930ns

|

3.504** |

2.043* |

| Yellowing index (YI) |

1.964ns

|

46.491*** |

20.061*** |

Table 4.

Changes in total soluble phenolic content (mg GAE 100 g⁻¹ FW) of fresh-cut lettuce as influenced by treatments and storage duration at 4 ± 1 °C.

Table 4.

Changes in total soluble phenolic content (mg GAE 100 g⁻¹ FW) of fresh-cut lettuce as influenced by treatments and storage duration at 4 ± 1 °C.

| |

Storage Duration (Days) |

|

| Treartments |

0 |

3 |

6 |

9 |

12 |

15 |

18 |

Treat Avg. |

| C |

136.8 ± 2.71ns |

298.9 ± 5.83b |

168.1 ± 5.37b |

199.1 ± 2.13a |

386.6 ± 5.56b |

311.7 ± 5.52c |

330.0 ± 5.82a |

261.6 b |

| SA |

136.8 ± 2.71ns |

331.1 ± 5.95a |

157.0 ± 4.83c |

187.0 ± 5.72b |

401.0 ± 4.90a |

340.8 ± 2.89a |

313.2 ± 3.42b |

266.7 a |

| CaNP |

136.8 ± 2.71ns |

238.3 ± 4.18c |

191.6 ± 5.17a |

191.8 ± 5.44ab |

330.4 ± 3.35d |

314.5 ± 4.20c |

300.5 ± 5.43c |

243.4 d |

| CaNP+SA |

136.8 ± 2.71ns |

308.2 ± 5.68b |

175.2 ± 3.32b |

199.2 ±1.71a |

347.6 ± 5.87c |

323.7 ± 4.58b |

293.6 ± 5.61c |

254.9 c |

| Time avg. |

136.8 F |

294.1 D |

173.0 F |

194.3 E |

366.4 A |

322.7 B |

309.3 C |

|

Table 5.

Effects of salicylic acid (SA, 2 mM) and calcium nanoparticles (CaNP, 100 mg L⁻¹) on the membrane stability index (MSI, %) of fresh-cut lettuce during 18 days of cold storage (4 ± 1 °C).

Table 5.

Effects of salicylic acid (SA, 2 mM) and calcium nanoparticles (CaNP, 100 mg L⁻¹) on the membrane stability index (MSI, %) of fresh-cut lettuce during 18 days of cold storage (4 ± 1 °C).

| |

Storage Duration (days) |

|

| Treatments |

0 |

3 |

6 |

9 |

12 |

15 |

18 |

Treat avg. |

| C |

97.71 ± 0.59ns |

94.70 ± 0.79a |

97.33 ± 0.76a |

97.05 ± 0.78b |

96.68 ± 1.19ns |

95.98 ± 0.63a |

97.37 ± 0.33a |

96.69 a |

| SA |

97.71 ± 0.59ns |

93.12 ± 1.29ab |

97.22 ± 0.44a |

98.93 ± 0.04a |

97.07 ± 0.55ns |

96.71 ± 0.52a |

97.27 ± 0.67ab |

96.86 a |

| CaNP |

97.71 ± 0.59ns |

90.90 ± 1.90b |

95.37 ± 0.15b |

97.49 ± 0.50b |

96.82 ± 0.75ns |

93.59 ± 1.59b |

94.42 ± 0.18 c |

95.18 b |

| CaNP+SA |

97.71 ± 0.59ns |

93.96 ± 1.71a |

96.55 ± 0.76a |

98.51 ± 0.31a |

96.22 ± 0.87ns |

96.14 ± 0.50a |

96.34 ± 0.66 b |

96.49 a |

| Time avg. |

97.71 A |

93.17 D |

96.62 B |

97.99 A |

96.70 B |

95.61 C |

96.35 B |

|

Table 6.

Effect of salicylic acid (SA) and calcium oxide nanoparticles (CaNP) on cutting resistance (N) of fresh-cut lettuce during cold storage.

Table 6.

Effect of salicylic acid (SA) and calcium oxide nanoparticles (CaNP) on cutting resistance (N) of fresh-cut lettuce during cold storage.

| |

Storage Dluration (days) |

|

| Treatments |

0 |

3 |

6 |

9 |

12 |

15 |

18 |

Treat avg. |

| C |

13.8 ± 0.94ns |

12.5 ± 1.28a |

11.7 ± 1.48ab |

12.8 ± 1.84a |

13.8 ± 1.73a |

12.2 ± 1.71ns |

14.7 ± 1.30a |

13.1 a |

| SA |

13.8 ± 0.94ns |

11.6 ± 1.32ab |

12.8 ± 1.35a |

11.8 ± 0.91a |

10.7 ± 1.44ab |

12.2 ± 1.56ns |

11.9 ± 1.27b |

12.1 b |

| CaNP |

13.8 ± 0.94ns |

8.5 ± 0.78c |

7.8 ± 0.58c |

8.5 ± 1.46b |

10.7 ± 1.35b |

9.7 ± 0.59ns |

10.9 ± 0.28b |

9.9 c |

| CaNP+SA |

13.8 ± 0.94ns |

9.9 ± 1.04bc |

10.7 ± 0.88b |

11.5 ± 1.22a |

12.2 ± 1.99ab |

10.5 ± 1.56ns |

12.6 ± 1.91ab |

11.5 b |

| Time avg. |

13.8 A |

10.6 C |

10.7 C |

11.1 C |

11.7 BC |

11.2 C |

12.5 B |

|

Table 7.

Effect of salicylic acid (SA) and calcium oxide nanoparticles (CaNP) on Chl a, chl b, total Chl, CSI and SPAD values of fresh-cut lettuce during cold storage.

Table 7.

Effect of salicylic acid (SA) and calcium oxide nanoparticles (CaNP) on Chl a, chl b, total Chl, CSI and SPAD values of fresh-cut lettuce during cold storage.

| |

Treatments |

Storage Duration (days) |

Treat Avg. |

| |

0 |

3 |

6 |

9 |

12 |

15 |

18 |

| Chl a |

C |

0.461 ± 0.007ns |

0.379 ±0.018ns |

0.366 ± 0.35b |

0.458 ± 0.001ns |

0.471 ± 0.002a |

0.446 ± 0.010b |

0.447 ± 0.008b |

0.433 b |

| SA |

0.459 ± 0.007ns |

0.348 ± 0.018ns |

0.446 ± 0.005a |

0.456 ± 0.002ns |

0.464 ± 0.000b |

0.459 ± 0.002a |

0.454 ± 0.001ab |

0.441 a |

| CaNP |

0.460 ± 0.007ns |

0.351 ±0.012ns |

0.438 ± 0.000a |

0457 ± .002ns |

0.463 ± 0.001b |

0.460 ± 0.002a |

0.461 ± 0.001a |

0.442 a |

| CaNP+SA |

0.459 ± 0.007ns |

0.364 ±0.017ns |

0.424 ± 0.002a |

0457 ± 0.000ns |

0.465 ± 0.001b |

0.459 ± 0.002a |

0.459 ± 0.003a |

0.444 a |

| Time avg. |

0.460 AB |

0.361 D |

0.424 C |

0.457 AB |

0.465 A |

0.456 B |

0.455 |

|

| Chl b |

C |

0.460 ± 0.042ns |

0.414 ± 0.011ns |

0.397 ± 0.025c |

0.473 ± 0.020ns |

0.328 ± 0.011ns |

0.351 ± 0.009ns |

0.458 ± 0.015a |

0.412 b |

| SA |

0.458 ± 0.042ns |

0.424 ± 0.045ns |

0.485 ± 0.022b |

0.494 ± 0.030ns |

0.349 ± 0.024ns |

0.382 ± 0.050ns |

0.448 ± 0.022ab |

0.434 a |

| CaNP |

0.459 ± 0.044ns |

0.439 ± 0.020ns |

0590 ± 0.011a |

0.531 ± 0.068ns |

0.374 ± 0.026ns |

0.359 ± 0.041ns |

0.401 ± 0.029b |

0.450 a |

| CaNP+SA |

0.459 ± 0.043ns |

0.438 ± 0.044ns |

0.498 ± 0.040b |

0.524 ± 0.015ns |

0.353 ± 0.029ns |

0.417 ± 0.034ns |

0.436 ± 0.030ab |

0.447 a |

| Time avg. |

0.459 B |

0.429 C |

0.493 A |

0.505 A |

0.351 D |

0.377 D |

0.436 BC |

|

| Total Chl |

C |

0.921 ± 0.035ns |

0.793 ± 0.029ns |

0.763 ± 0.026c |

0.930 ± 0.019ns |

0.800 ± 0.009ns |

0.797 ± 0.016b |

0.905 ± 0.018ns |

0.844 b |

| SA |

0.918 ± 0.038ns |

0.772 ± 0.063ns |

0.931 ± 0.017b |

0.950 ± 0.028ns |

0.813 ± 0.024ns |

0.841 ± 0.046ab |

0.902 ± 0.021ns |

0.875 a |

| CaNP |

0.919 ± 0.040ns |

0.790 ± 0.030ns |

1.028 ± 0.011a |

0.988 ± 0.066ns |

0.837 ± 0.025ns |

0.820 ± 0.039ab |

0.862 ± 0.028ns |

0.892 a |

| CaNP+SA |

0.918 ± 0.039ns |

0.803 ± 0.060ns |

0.94 ± 0.039b |

0.981 ± 0.015ns |

0.817 ± 0.029ns |

0.876 ± 0.032a |

0.896 ± 0.027ns |

0.891 a |

| Time avg. |

0.919 B |

0.789 D |

0.917 B |

0.962 A |

0.817 CD |

0.834 C |

0.891 B |

|

| CSI |

C |

100 ± 0 |

85.92 ± 5.50ns |

83.61 ± 4.57b |

99.85 ± 4.13ns |

86.86 ± 3.20ns |

86.62 ± 4.10ns |

97.14 ± 0.75ns |

91.43 b |

| SA |

100 ± 0 |

84.34 ± 2.88ns |

100.13 ± 5.91a |

103.02 ± 5.62ns |

88.75 ± 4.86ns |

91.39 ± 8.02ns |

97.26 ± 5.40ns |

94.98 a |

| CaNP |

100 ± 0 |

85.66 ± 5.12ns |

110.60 ± 3.64a |

106.65 ± 4.53ns |

90.35 ± 1.97ns |

88.68 ± 7.9ns |

93.19 ± 1.87ns |

96.45 a |

| CaNP+SA |

100 ± 0 |

86.73 ± 2.51ns |

102.47 ± 6.80a |

105.97 ± 4.97ns |

88.77 ± 5.50ns |

95.15 ± 7.08ns |

97.13 ± 1.35ns |

96.60 a |

| Time avg. |

100.00 B |

85.66 D |

99.20 B |

103.87 A |

88.68 CD |

90.46 C |

96.18 B |

|

| SPAD |

C |

26.2 ± 0.46ns |

27.2 ± 0.86bc |

24.3 ± 0.61a |

23.2 ± 0.44b |

21.5 ±0.72c |

20.5 ± 0.87b |

21.1 ± 0.90c |

23.4 c |

| S |

26.2 ± 0.46ns |

26.1 ± 0.68c |

23.0 ± 0.31a |

22.2 ± 0.68b |

27.2 ± 0.67a |

25.7 ± 0.64a |

23.8 ± 0.70b |

24.9 a |

| CNP |

26.2 ± 0.46ns |

29.4 ± 0.55a |

23.8 ± 0.87ab |

24.5 ± 0.64a |

26.5 ± 0.56a |

21.3 ± 0.91b |

23.5 ± 0.47b |

25.0 a |

| CNP+S |

26.2 ± 0.46ns |

28.4 ± 0.93ab |

21.9 ±0.76b |

22.9 ± 0.60b |

24.2 ± 0.68b |

20.4 ± 0.72b |

25.2 ± 0.72a |

24.2 b |

| |

Time avg. |

26.2 B |

27.8 A |

23.3 D |

23.2 D |

24.9 C |

22.0 E |

23.4 D |

|

Table 8.

Effect of salicylic acid (SA) and calcium oxide nanoparticles (CaNP) on color parameters of fresh-cut lettuce during cold storage.

Table 8.

Effect of salicylic acid (SA) and calcium oxide nanoparticles (CaNP) on color parameters of fresh-cut lettuce during cold storage.

| |

|

Storage Duration (days) |

|

| |

Treatments |

0 |

3 |

6 |

9 |

12 |

15 |

18 |

Treat avg. |

| L values |

C |

52.4 ± 0.84ns |

52.9 ± 1.05ns |

53.56 ± 1.19a |

53.5 ± 1.28b |

54.1 ± 1.21a |

53.5 ± 0.36a |

54.3 ± 1.54ns |

53.47 a |

| SA |

52.4 ± 0.84ns |

51.7 ± 1.38ns |

51.1 ± 1.03b |

53.9 ± 1.12b |

46.4 ± 1.60b |

50.8 ± 1.65b |

54.2 ± 1.24ns |

51.49 b |

| CaNP |

52.4 ± 0.84ns |

51.8 ± 0.86ns |

53.3 ± 1.15b |

55.4 ± 1.42ab |

51.4 ± 1.70a |

46.4 ± 1.57c |

53.5 ± 1.10ns |

52.02 b |

| CaNP+SA |

52.4 ± 0.84ns |

51.0 ± 0.75ns |

51.8 ± 0.67ab |

57.0 ± 1.28a |

52.2 ± 0.88a |

52.7 ± 0.34ab |

54.1 ± 0.79ns |

53.03 a |

| |

Time avg. |

52.39 C |

51.87 CD |

52.45 C |

54.94 A |

51.02 DE |

50.82 E |

54.01 B |

|

| Hue |

C |

118.4 ± 1.25

|

115.2 ± 1.88

|

117.9 ± 0.71

|

118.5 ± 1.48

|

117.6 ± 0.89

|

118.0 ± 0.61

|

118.8 ± 1.72

|

117.8 b |

| SA |

118.4 ± 1.25

|

117.36 ± 0.64

|

118.9 ± 1.58

|

119.0 ± 0.61

|

119.3 ± 0.72

|

118.6 ± 1.59

|

119.9 ± 0.31

|

118.8 a |

| CaNP |

118.4 ± 1.25

|

119.5 ± 1.29

|

118.7 ± 0.21

|

117.4 ± 1.71

|

118.8 ± 0.58

|

118.3 ± 1.73

|

119.1 ± 0.97

|

118.6 a |

| CaNP+SA |

118.4 ± 1.25

|

118.2 ± 0.59

|

118.7 ± 0.39

|

116.6 ± 2.88

|

118.4 ± 0.41

|

118.1 ± 0.78

|

119.3 ± 0.71

|

118.2 ab |

| |

Time avg. |

118.4 AB |

117.6 B |

118.5 AB |

117.9 B |

118.5 AB |

118.2 AB |

119.3 A |

|

| Delta E |

C |

0 |

2.68 ± 1.66ns |

2.82 ± 1.12ns |

2.51 ± 0.63bc |

3.47 ± 1.96b |

2.05 ± 0.66b |

4.08 ± 1.62ns |

2.52 b |

| SA |

0 |

2.84 ± 1.63ns |

3.05 ± 0.36ns |

2.09 ± 1.11c |

7.74 ± 2.43a |

2.53 ± 1.71b |

3.20 ± 1.27ns |

3.06 ab |

| CaNP |

0 |

3.77 ± 1.55ns |

2.63 ± 1.57ns |

4.57 ± 0.97ab |

2.32 ± 0.57b |

6.23 ± 1.24a |

3.82 ± 2.24ns |

3.33 a |

| CaNP+SA |

0 |

2.29 ± 1.07ns |

2.40 ± 0.31ns |

5.64 ± 1.70a |

1.03 ± 0.79b |

1.01 ± 0.37b |

4.45 ± 0.51ns |

2.40 b |

| |

Time avg. |

0 |

2.89 AB |

2.72 B |

3.70 AB |

3.64 AB |

2.95 AB |

3.89 A |

|

| Chroma |

C |

34.7 ± 0.60ns |

34.9 ± 1.77a |

33.1 ± 1.56ns |

33.1 ± 0.97ns |

32.2 ± 1.81ab |

33.2 ± 0.75ns |

34.3 ± 1.48ns |

33.6 ab |

| SA |

34.7 ± 0.60ns |

32.9 ± 1.75ab |

32.3 ± 0.76ns |

33.8 ± 1.2ns |

29.9 ± 1.68b |

33.4 ± 0.74ns |

33.2 ± 0.72ns |

32.9 b |

| CaNP |

34.7 ± 0.60ns |

31.2 ± 1.92b |

32.3 ±1.41ns |

32.4 ± 1.25ns |

34.1 ± 0.90a |

34.0 ± 1.64ns |

34.5 ± 1.61ns |

33.3 ab |

| CaNP+SA |

34.7 ± 0.60ns |

34.0 ± 1.82ab |

34.4 ± 1.90ns |

32.1 ± 1.75ns |

34.0 ± 0.40a |

34.4 ± 0.97ns |

33.2 ± 1.94ns |

33.8 a |

| |

Time avg |

34.7 A |

33.2 B |

33.0 A |

32.8 B |

32.6 B |

33.8 AB |

33.8 AB |

|

| YI |

C |

83.2 ± 1.15ns |

85.2 ± 1.44a |

77.9 ± 1.47bc |

77.7 ± 1.84a |

75.3 ± 1.04b |

78.3 ± 1.68c |

79.1 ± 1.93ab |

79.54 b |

| SA |

83.2 ± 1.15ns |

80.5 ± 1.69b |

79.1 ± 1.43b |

78.3 ± 1.29a |

80.4 ± 1.66a |

82.6 ± 1.49b |

75.9 ± 1.78b |

80.02 ab |

| CaNP |

83.2 ± 1.15ns |

74.9 ± 1.85c |

76.1 ± 1.24c |

74.1 ± 1.57b |

83.0 ± 1.68a |

92.6 ± 1.29a |

80.4 ± 1.76a |

80.62 a |

| CaNP+SA |

83.2 ± 1.15ns |

84.0 ± 1.69a |

83.2 ± 1.08a |

71.8 ± 1.51b |

81.9 ± 1.26a |

82.4 ± 1.99b |

75.8 ± 1.52b |

80.33 ab |

| |

Time avg. |

83.24 A |

81.16 B |

79.10 C |

75.49 E |

80.15 BC |

83.96 A |

77.80 D |

|