1. Introduction

Archeology is, in its etymology, the discourse of origin (Santos & Soares, 2019), which in contemporary times has established itself as a scientific field dedicated to the study of human history through the investigation of material remains (Ashmore & Sharer, 2010). The validation of archaeological research involves an iterative process that culminates in the publication of results, both for researchers and for a wider audience (Ashmore & Sharer, 2010). Thus, as mentioned by Laato & Laato (2020), the presentation of results should cover three areas: scientific information about what the artifacts represent, reconstructions of the artifacts, and the artifacts themselves. However, it should be noted that the archaeological exhibition process is complex and often there is not the capacity to address all three areas, especially when the setting is the site of the discovery.

Since it inherently involves a set of ethical commitments, such as the protection of artifacts, respect for individuals from the past and present (Ashmore & Sharer, 2010), and the preservation of sites and regions (Timothy & Boyd, 2006), which must be taken into consideration, leading to the careful selection of the means used to structure and materialize the presentation.

In this sense, Augmented Reality (AR) technology stands out, allowing digital content to be superimposed on real environments, with the aim of combining the physical and virtual worlds to create the sensation in the user that the two exist simultaneously (Azuma, 1997). In addition, the fundamental characteristics of this technology include real-time interactivity and the spatial and temporal recording of virtual elements (Azuma, 1997; Azuma et al., 2001). AR has the potential to stimulate all human senses (Azuma, 1997; Craig, 2013) and to provide varying degrees of interactivity (Craig, 2013).

AR was first used in an outdoor archaeological context in 2001, in the Archeoguide project, a portable system that allowed visitors to move around archaeological sites and view reconstructions of ancient structures (Vlahakis et al., 2002). However, at the beginning of the millennium, the development of portable AR applications meant that users had to carry around a set of large devices, which was uncomfortable and limited in terms of access. However, since the advent of smartphones and smart tablets with the necessary hardware to implement AR, the development of AR mobile applications (apps) on these devices has begun to proliferate (Azuma et al., 2001). In addition to providing the technical conditions, they are also familiar to users, do not require extra monetary investment, and can be used anywhere and anytime (Craig, 2013).

In this context, the implementation of AR apps for archaeological presentation offers a number of advantages, such as the possibility of adding information to the site and restoring and/or supplementing artifacts (Laato & Laato, 2020), without, depending on the recording process, involving actions in the physical environment.

However, AR is still considered a recent medium, which is only expected to reach its potential and establish itself with new technological developments, so the current moment is classified as a period of experimentation (Craig, 2013; Pangilinan et al., 2019).

Therefore, considering the potential of AR and the benefits it brings to archaeological discourse exposed to a general audience, it is important to understand how AR has been studied and applied in this context. To this end, the overall objective of this review is to survey AR apps developed for the archaeological context of sites and/or regions over the last five years. Specific objectives include identifying the extent to which the potential of AR is being exploited, particularly in terms of human senses and dimensions of interaction (Sharp et al., 2019; Lueg et al., 2019), and verifying which practices and guidelines have been developed and validated, so that researchers or those interested in this area can use them as a reference.

Thus, the research question that this review aims to answer is: How have mobile AR applications been used in the archaeological presentation of sites and/or regions?

2. Methodology

This literature review is conducted according to the latest 2020 guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol (Page et al., 2021), which provides a checklist of seven basic sections and a three-step flowchart as tools. In order to ensure the transparency and reproducibility of the study, both instruments were used, employing the sections and topics of the checklist with minor adaptations. The flowchart was used to determine the results to be considered for analysis, which then led to the results and discussion.

This section presents the database search strategies, the eligibility criteria to which the documents were subjected, how the data from the selected documents were extracted, the approaches used for data analysis, and the possible risk of bias that may be associated with the study.

2.1. Search strategy

The documents to be included in the review were identified in two databases, SciVerse Scopus and Web of Science (WoS), using a query referring to the three main areas of the study: archaeology, apps, and AR. Thus, to represent archaeology, three terms were defined: archaeological, archaeology, and archeology. The latter is a variant less commonly used in the academic domain; however, in order not to exclude possible results relevant to the study, it was included in the combination. In the context of apps, the words mobile application and the abbreviation app were established.

The terms augmented reality and its acronym AR were determined as references to AR. In order to obtain results in which AR was the central theme, terms related to it were searched in the databases by title only, while words related to archaeology and apps could be included in the title, abstract, or keywords. It was also decided to use a single query, as it was considered sufficiently expressive and adequate for the study, whereas more queries could lead to excessive and unnecessary results.

Thus, the search combination is: ((archeology) OR (archaeolog*)) AND ((“mobile application*”) OR (app)) AND ((“augmented reality”) OR (ar)).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

In order to identify the most relevant documents for the study, a set of eight criteria was defined to which the collected documents had to respond, namely: time interval, language, case study, Digital Platform (DP) and AR technology, archaeological context, communication, publication status, and document type. With the intention of maintain the integrity of the process and select documents in a consistent and clear manner, it was decided that documents that meet the following statements, which correspond to the inclusion criteria, should be included in the review analysis:

Time interval: The document was published between 2017 and the date of the database search (January 9, 2022).

Language: The document is written in Portuguese, English, or Spanish.

Case study: The document refers to a case study relevant to the study, which presents the decision-making process.

DP and AR technology: The DP used is an app that integrates AR technology, and the central theme of the document is AR.

Archaeological context: The document refers to a case study at the original location of the archaeological artifact.

Communication: DP mediates communication between former visitors, visitors, or potential visitors and heritage sites, with a focus on external communication.

Publication status: The document has already been published (final status).

Document type: The document is an article, conference paper, or proceedings paper.

At the same time, because there are inclusion criteria that create room for uncertainty, the following statements have been defined, which represent the exclusion criteria:

DP and AR technology: The document presents a case in which AR technology is not incorporated into an app, or shares its focus with other technologies. Example: Head-mounted display (HMD), WebAR, or sharing the study with Virtual Reality (VR).

Archaeological context: The document presents a case study where the artifact is not located in its place of origin.

Communication: DP serves internal communication between employees and/or assets. Example: Presentation of an AR app in the archaeological context that assists archaeologists in the dating process.

2.3. Data collection

The data collection from the documents selected for analysis was guided by a table (Appendix 1) that uses the following fields: author(s), year of publication, language, document type, title, objectives, archaeological context, AR, interaction, methods or instruments, main results, risk of bias, and notes. Data relating to year of publication, language, and document type were used to provide a broad overview of eligible documents. Fields relating to objectives, archaeological context, AR, interaction, methods or instruments, main results, and notes were used to extract more detailed information for the synthesis and discussion. It is also considered appropriate to add the field of bias risk as a means of weighing the individual quality of each document.

2.4. Data analysis and synthesis

The data collected from the documents eligible for analysis were processed using quantitative and narrative synthesis approaches. The quantitative approach was used to support the preparation of the overview of the documents, and the narrative synthesis process was applied to systematically organize the main findings identified, given that the documents analyzed fall within a broad field of research (Popay et al., 2006). In order to achieve a reliable and methodical review, the narrative synthesis was guided by the technique of textual description, which summarizes each document selected for analysis as a preliminary way of presenting and comparing them, seeking to recognize and distinguish the decisions made in each one.

2.5. Risk of bias

The documents were reviewed by the author, who consulted other researchers in cases of doubt. Thus, the documents underwent a rigorous selection process based on established eligibility criteria, in which all documents were initially screened based on their title, abstract, and keywords , excluding those that did not meet the defined inclusion criteria and moving on to the next selection phase, which involved reading the documents in full, those that met the inclusion criteria and those that raised doubts. After reading all the documents in full, it was determined which ones should be included in the analysis and data collection was carried out using the table outlined above. At the time of data collection, the quality of each document was also assessed, following the recommendations of Cochrane (Higgins et al., 2021). An assessment was carried out based on domains, which were established according to the characteristics of the review, reflecting the depth of each project's presentation, it is possible evaluation and results. Each domain was associated with a low risk of bias, some concerns, and a high risk of bias.

It should also be noted that the databases selected for the research are respected in the field of research and are considered benchmarks by peers. In Scopus, all indexed publications are peer-reviewed (Scopus, n.d.), and in WoS, the largest number of indexed publications is also associated with peer-reviewed documents (Clarivate, 2018), which increases the reliability and transparency of eligible documents.

3. Results

This section presents the procedure for selecting documents according to the defined eligibility criteria, as well as the identification of studies to be included in the review and the respective data collection and presentation of information based on a quantitative overview and a narrative summary of textual descriptions.

3.1. Document selection

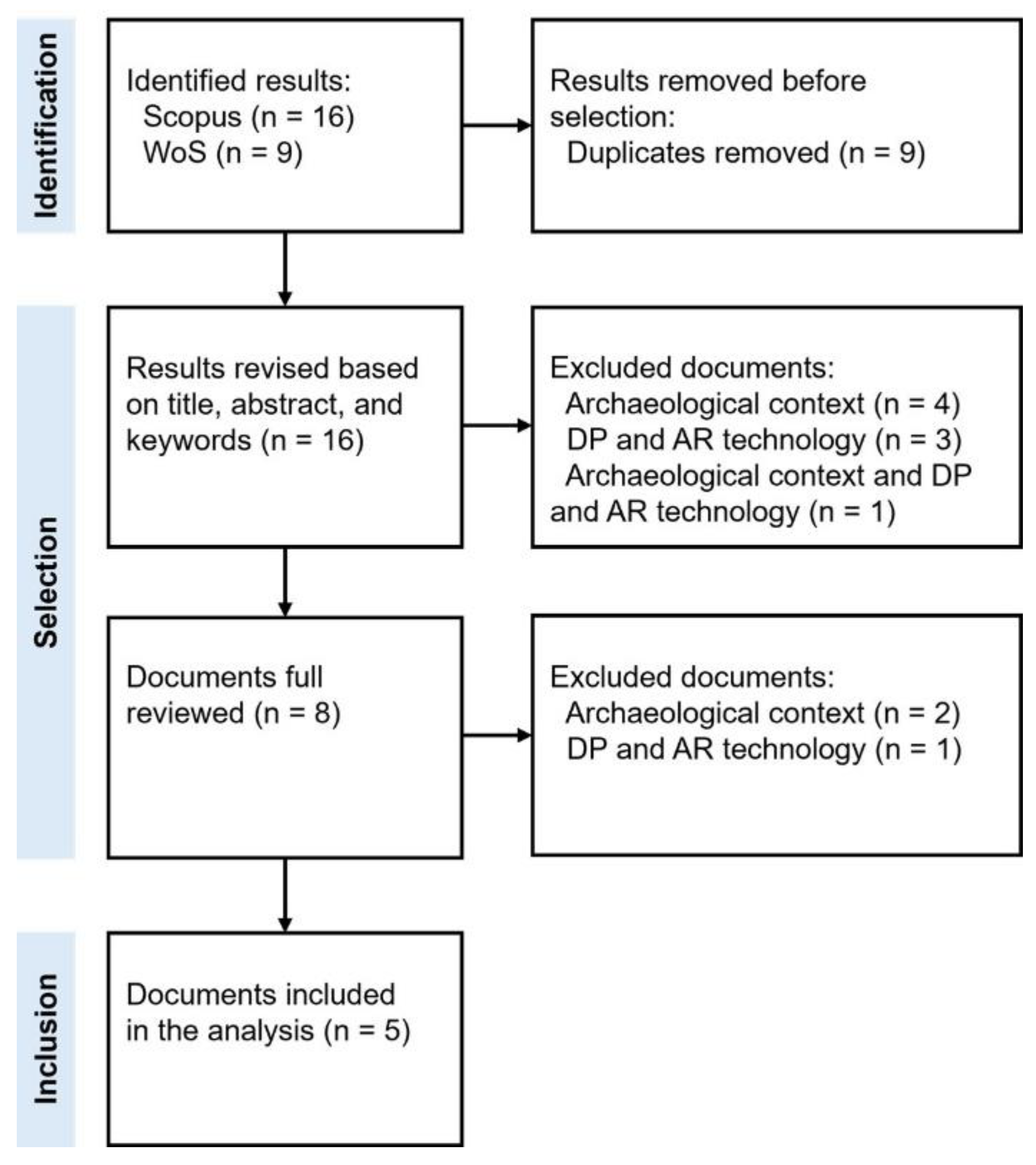

In the identification phase of the document selection process (

Figure 1), limiting the query defined to the established inclusion criteria of time interval, language, document publication status, and document type, 16 results were obtained from the Scopus database and 9 results from WoS, with the 9 results from WoS being duplicates of documents already collected from Scopus.

Thus, in the first selection phase, 16 documents were reviewed based on their title, abstract, and keywords, of which 8 were excluded, 4 of them (Abate et al., 2018; Barrile, Fotia, Bilotta, et al., 2019; Barrile, Fotia, Candela, et al., 2019; Barrile, Fotia, Ponterio, et al., 2019) because they did not meet the inclusion criterion of archaeological context, given that they presented solutions for archaeological artifacts exhibited in museums and not in their original location. Three did not meet the DP and AR technology criteria, since one of them (Botrugno et al., 2017) divided the core of the research between AR and unmanned aerial vehicles (drones), one (Fritsch & Klein, 2017) focused on exploring 3D and 4D models for AR and VR, and the other (Nawaf et al., 2021) divided the study between AR and VR. Finally, one of the eight (Seidametova et al., 2021) did not meet the inclusion criteria of archaeological context or DP and AR technology, as it presented a comparative analysis of software development kits and the project's area of activity was architecture, since archaeology was only mentioned in a list of AR application contexts.

In the second selection stage, three of the eight documents reviewed in full were excluded, two of which (Antoniou et al., 2020; Cisternino et al., 2018) did not meet the inclusion criterion of archaeological context, since the experiments developed in these projects did not refer to the original locations of the artifacts. The third (Blanco-Pons et al., 2019) did not meet the criteria for DP and AR technology, presenting an analysis between the Vuforia and ARToolkit libraries.

This resulted in a set of five documents to be included in the analysis, the data collection and systematization of which is presented in the next subsection – 3.2.

3.2. Selected documents and characteristics

The five documents selected for analysis meet all the inclusion criteria, and the total number of documents refers to case studies presenting a prototype or final product of an app that incorporates AR technology to superimpose one or more layers of digital content onto the physical world, in a specific archaeological context and in situ, i.e., at the original location where an event took place or where there are historical artifacts or traces of them.

For the analysis of the documents, the following textual descriptions of each study were made, in order to provide an initial comparison between them.

Document 1, Augmented Reality Storytelling Submerged. Dry Diving to a World War II Wreck at Ancient Phalasarna, Crete (Liestøl et al., 2021), presents the prototype of the Phalasarna 1941 AR app, whose purpose is to establish a contrast between the present and past of Phalasarna (Greece) and reconstruct the sinking of the Tank Landing Craft A6 during World War II. In terms of AR, an indirect approach was used, a location-based (LB) registration process, and the senses augmented by the technology were sight and hearing. In terms of interaction, learning and leisure were identified as contexts for the activity, and the dimensions of interaction employed were instruction, manipulation, and exploration. For the design of the project, the media design method was also applied, and a usability evaluation of the prototype was carried out on site.

Document 2, Design and implementation of an augmented reality application for rock art visualization in Cova dels Cavalls (Spain) (Blanco-Pons et al., 2019), refers to the prototype of an app that aims to reconstruct compositions of cave paintings from the Cova dels Cavalls Cave (Spain). A direct approach was used for AR, the recording process was LB, and the augmented sense was vision. Regarding interaction, the contexts of the activity are learning and leisure, and the types of interaction applied were instruction and exploration. To verify whether the project increased users' understanding of the paintings, a usability assessment was carried out on site.

Document 3, Scaffolding augmented reality inquiry learning: the design and investigation of the TraceReaders location-based, augmented reality platform (Kyza & Georgiou, 2019), presents two case studies, one of which, Young Archaeologists, refers to a prototype application that aims to assist in the informal learning process of primary school students about the archaeological site of Choirokoitia (Cyprus). In terms of AR, a direct approach was used, the selected recording process was LB, and the augmented sense was vision. Regarding interaction, the activity context is learning, and the dimensions employed were instruction, manipulation, exploration, and response. To assess whether the project contributed to information retention and student learning, two empirical studies were conducted, using and comparing the results between an experimental group that used the application during the site visit and a control group that experienced the standard site visit.

Document 4, Avebury Portal – A Location-Based Augmented Reality Treasure Hunt for Archaeological Sites (Shakouri & Tian, 2019), refers to the prototype of the Avebury Portal app, which aims to provide a layer of informative contextualization of the Neolithic stone circle at Avebury (England) through a “treasure hunt.” A direct approach was applied to AR, the registration process was LB, and the augmented sense was vision. In terms of interaction, the contexts of the activity were learning and leisure, and the types adopted were exploration and response. To determine whether the prototype served its purpose, a triangulation methodology was applied, where potential users used the app, followed by an individual interview and completion of a survey.

Document 5, Augmented reality for the enhancement of archaeological heritage: A Calabrian experience (Berlino et al., 2019), presents an implemented product, an app for enhancing points of interest (PoI) in the Castiglione di Paludi Archaeological Park (Italy). In terms of AR, a direct approach was selected, using the marker-based (MB) registration process and augmented vision. Regarding interaction, the activity contexts are learning and leisure, and the dimension used was exploration. Although this is a final product, no reference was made in the document to a possible evaluation with users.

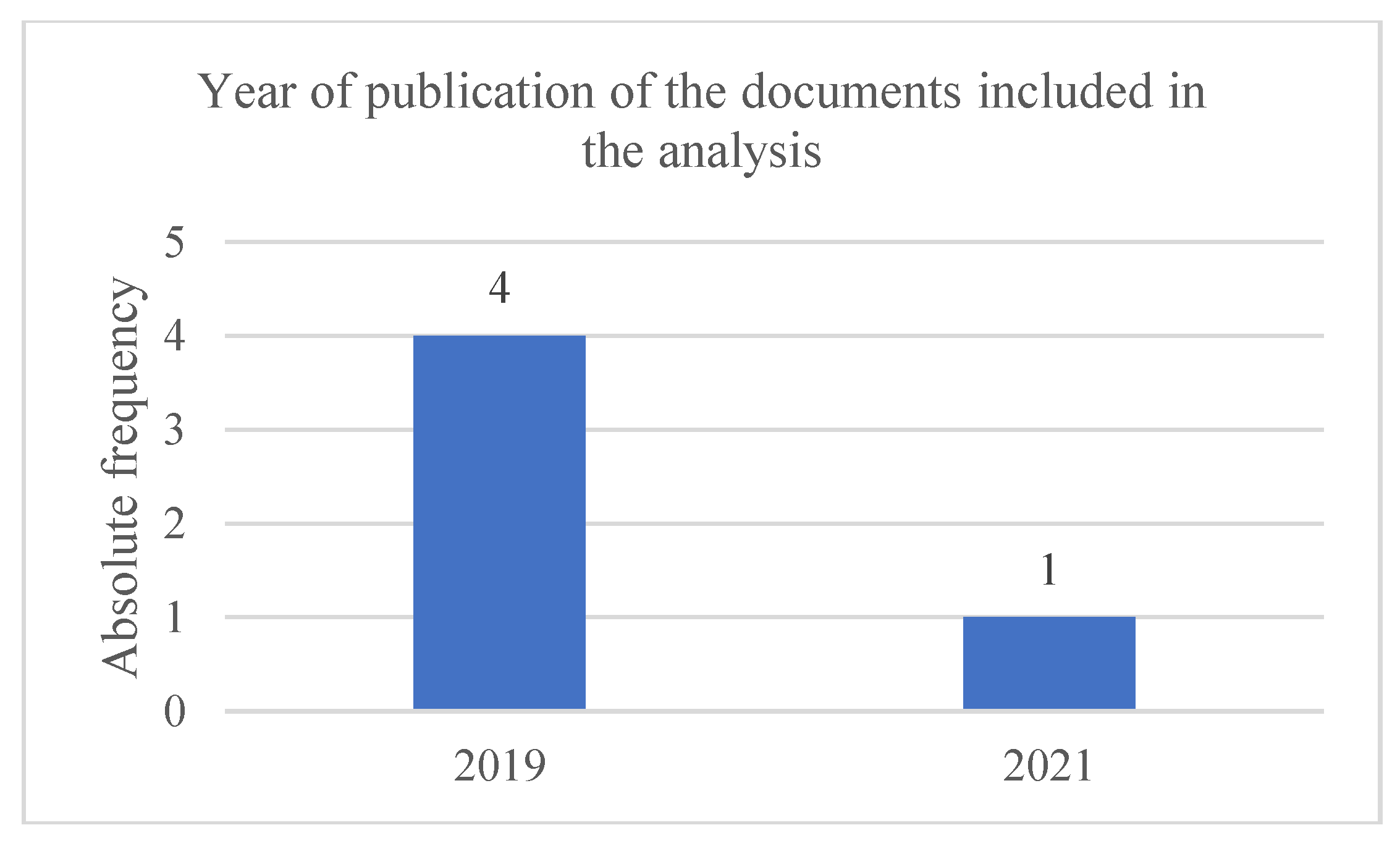

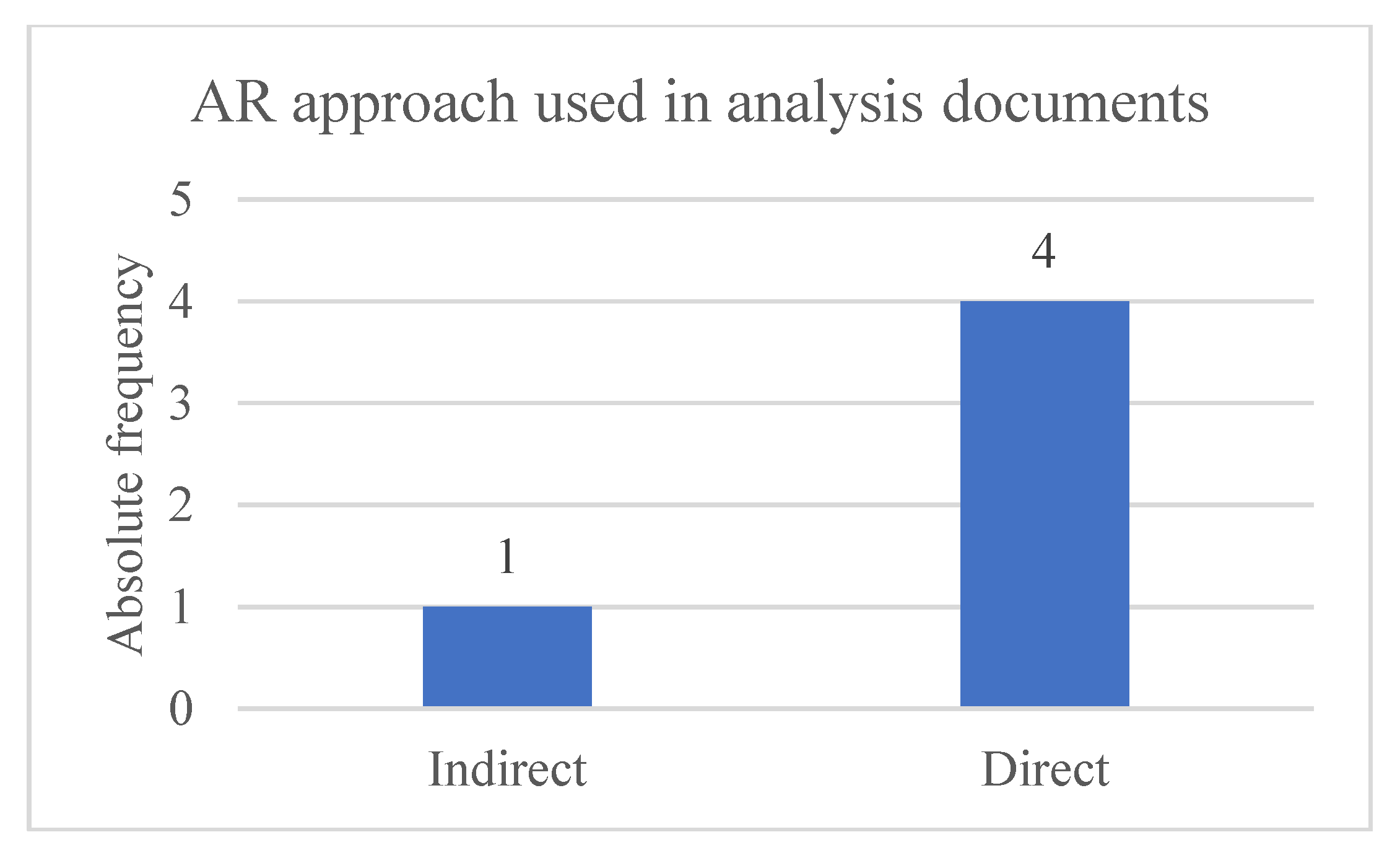

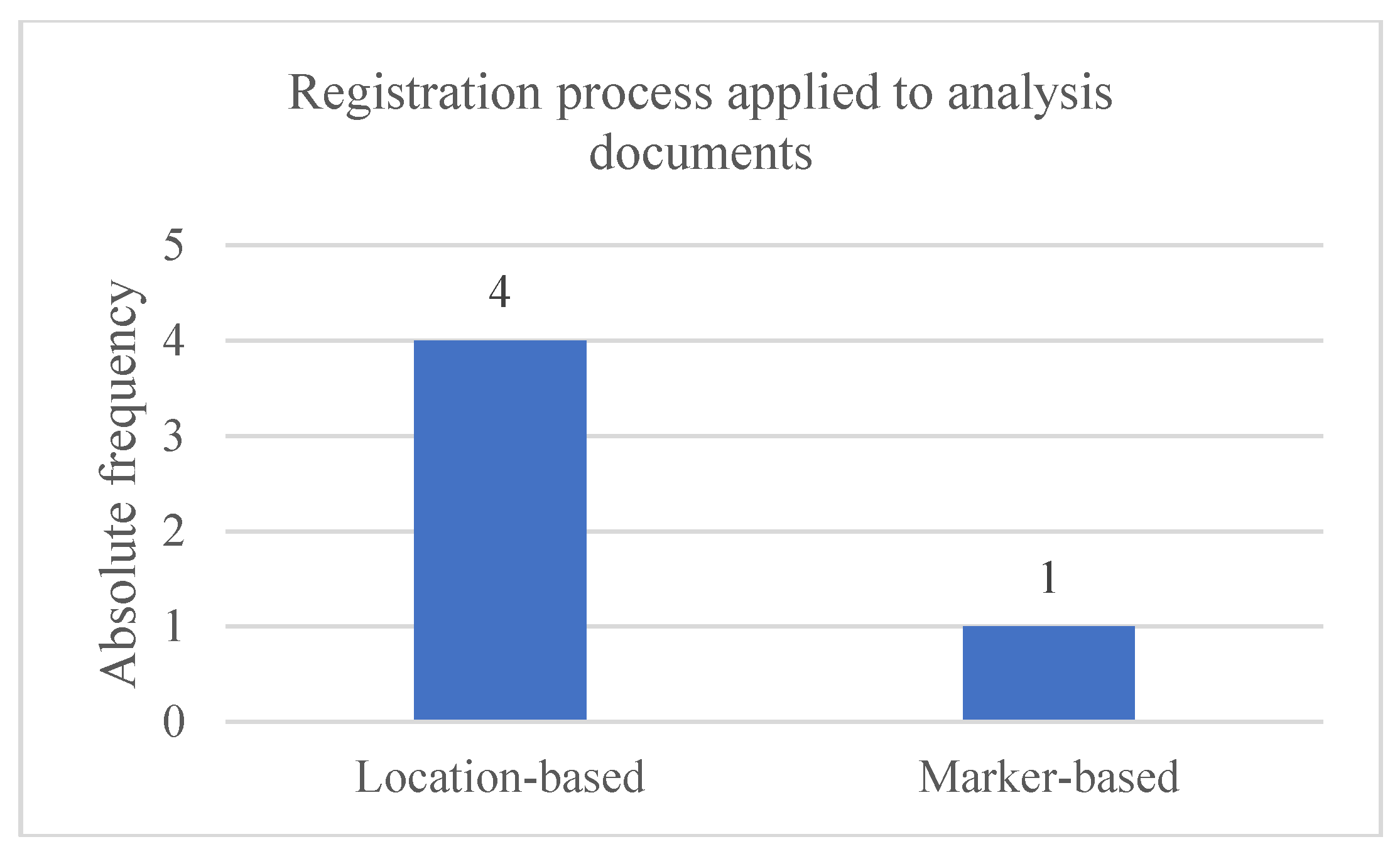

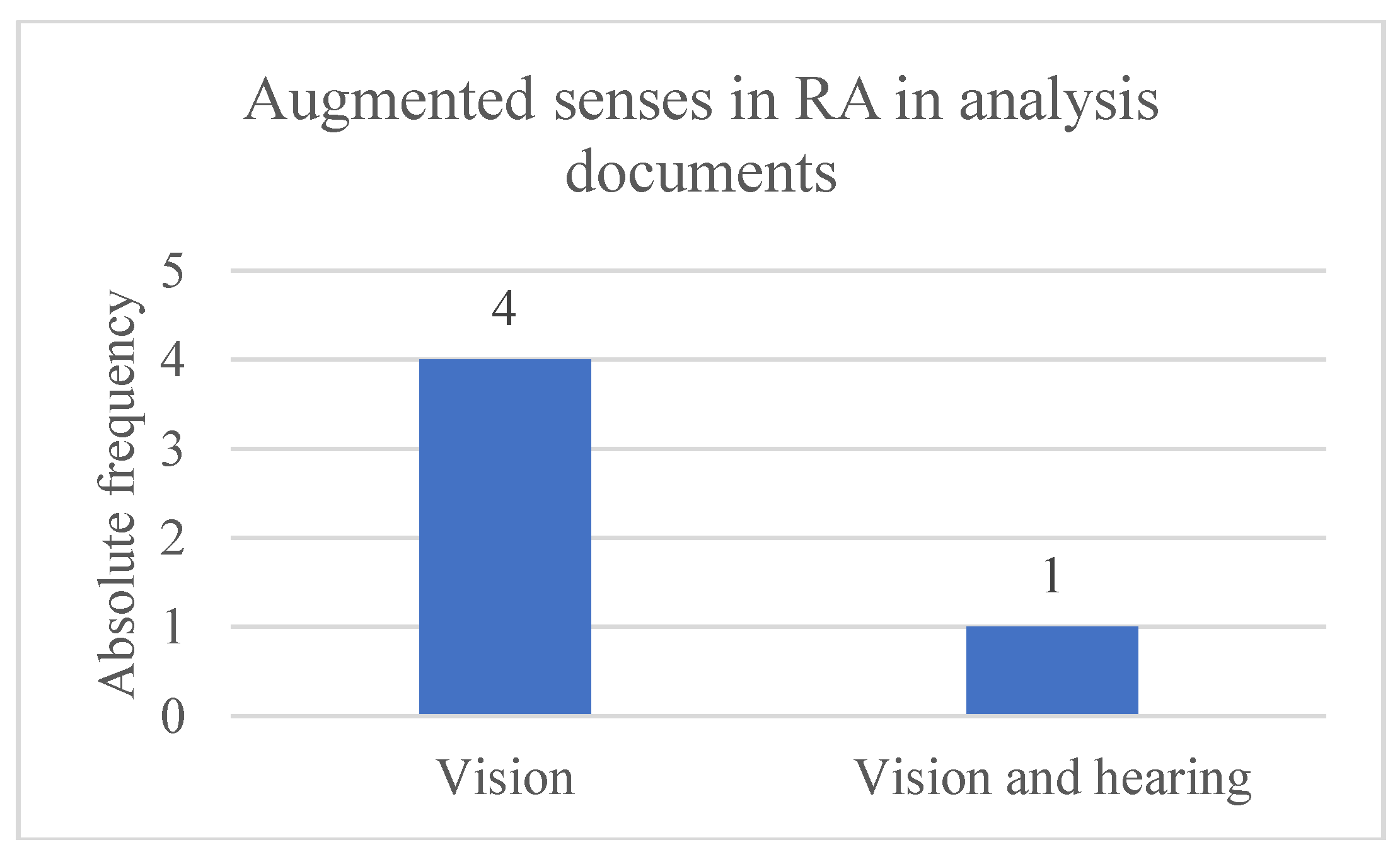

Thus, based on the textual descriptions, it is possible to outline a general overview of the studies, thereby 80% (4) of the documents were published in 2019 and 20% (1) in 2021. Concerning AR technology, 20% (1) of the projects used an indirect approach versus 80% (4) that opted for the direct approach as a form of registration process. 20% (1) applied the MB technique and 80% (4) applied the LB technique. It was found that 80% (4) only augmented the sense of sight, while 20% (1) augmented both sight and hearing.

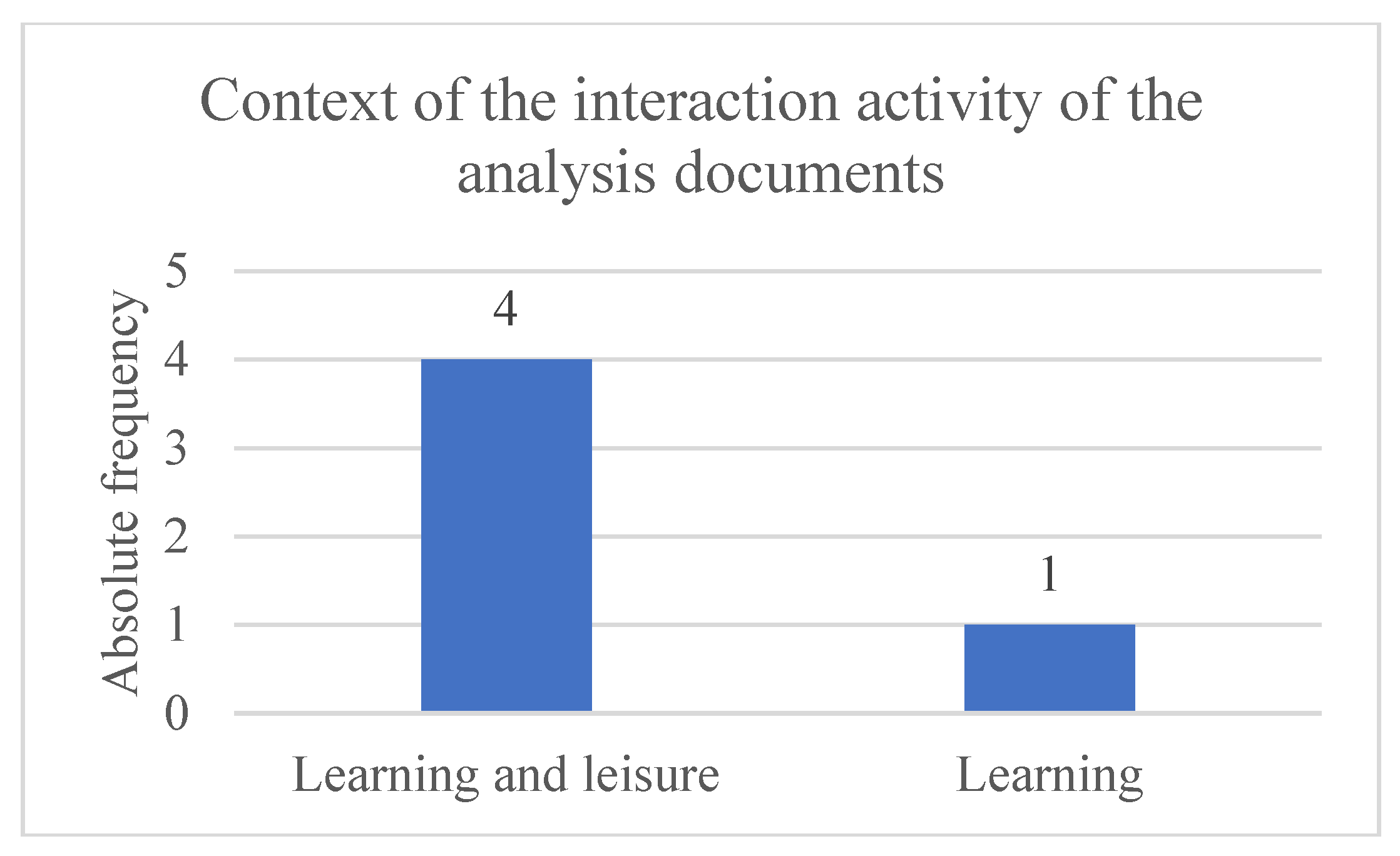

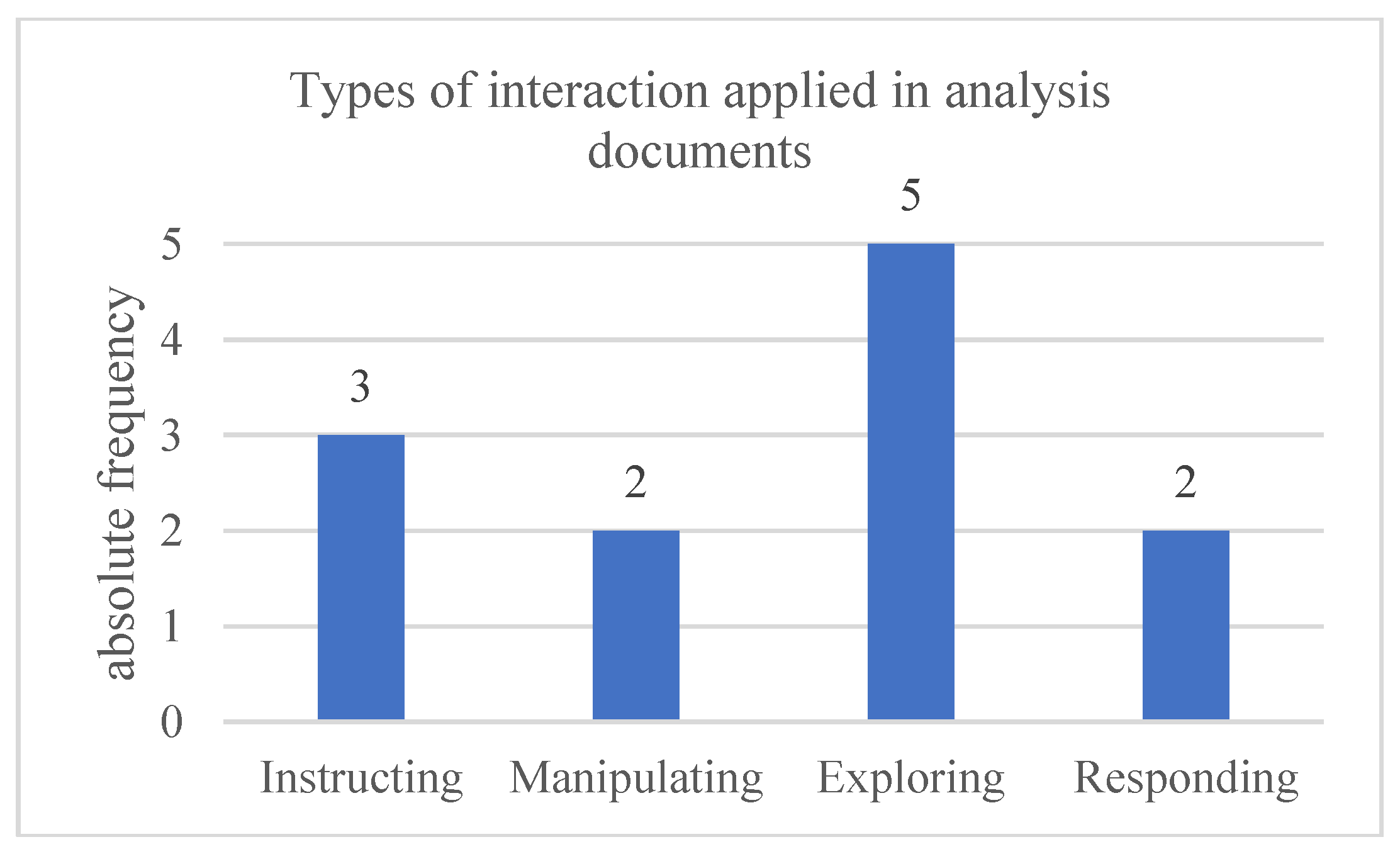

Regarding the area of interaction, it was found that 80% (4) of the studies encompassed the contexts of learning and leisure activities, and 20% (1) only learning. It was also found that the type of interaction most used in the projects was exploration, employed in 100% (5) of cases, followed by instruction (60% - 3 studies), manipulation (40% - 2 studies), and response (40% - 2 studies).

Related to methods and instruments, in addition to case studies, it was found that each project integrated different methods, namely, one applied media design and usability assessment methods, one applied usability assessment only, one developed an empirical study, one adopted triangulation methodologies, and the rest did not mention any other methods except case studies.

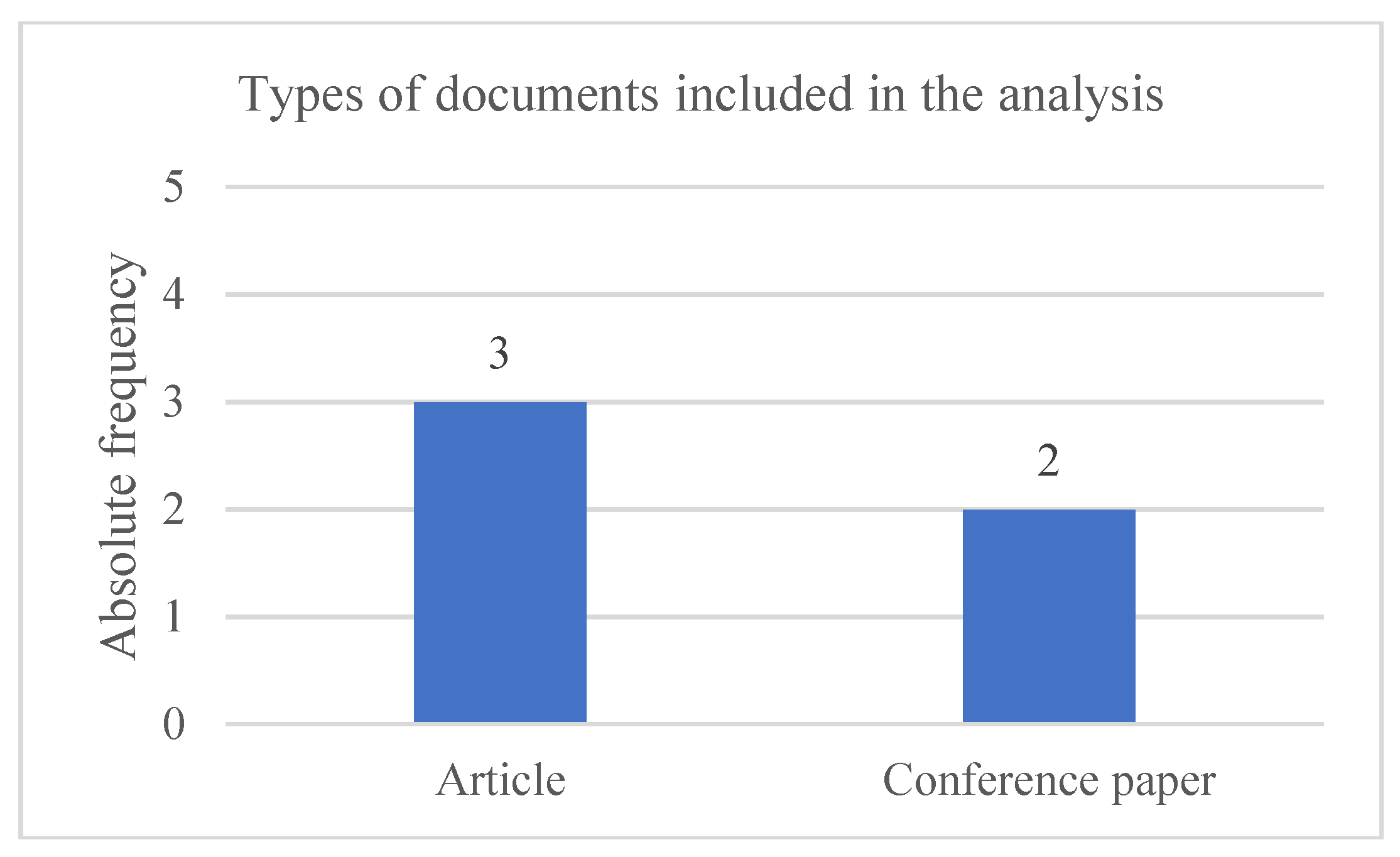

Based on the data collected and processed (Appendices 1 and 2), it should also be added to this scenario that 60% (3) of the documents are articles and 40% (2) are conference papers. Documents 1, 2, 3, and 4 were associated with a low risk of bias, while document 5 raised some concerns, given that, despite being an implemented product, it does not provide any justification for the highlighted advantages of using the app.

4. Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this review was to investigate the practices that have been adopted in the development of AR apps in the archaeological context in situ between January 1, 2017, and January 9, 2022. To this end, a search was conducted in the Scopus and WoS databases, using a query that included a set of terms related to archaeology, apps, and AR, which yielded a total of 16 documents, excluding duplicates. The 16 documents underwent two selection phases with the aim of identifying studies that met the defined eligibility criteria. The first phase was based on reading the title, abstract, and keywords, and the second on a comprehensive review of the study, resulting in a total of five documents eligible for analysis.

The five documents correspond to case studies, where in 80% (4) the application of methods and instruments for collecting data from potential end users was verified, such as usability assessment, empirical study, and triangulation methodology. The need to resort to these reflects researchers' concern with evaluating and validating proofs of concept developed for the corresponding audiences, that is, to try to create an image of the system that is in line with users' needs and objectives, which is fundamental to good behavioral design (Norman, 2004).

In studies 1, 2, 4, and 5, it was considered that the AR projects developed enrich the user experience and promote learning, and in study 3, that the use of AR for informal learning can increase information retention.

In terms of augmented human senses, it was found that vision was the sense explored in all projects, with only study 1 also incorporating hearing. Although vision is the most augmented sense when DP is an app (Craig, 2013), it was expected that, at a time of experimentation, projects would attempt to integrate more senses. However, in addition to the technical limitations that AR is subject to in apps, it should be noted that, considering the archaeological context in situ, the authors of the projects may have chosen not to explore other senses, namely hearing, which to a certain extent can be considered the second easiest sense to enhance in apps, so that users could enjoy the richness of the real environment and thus make the experience more realistic.

With regard to content, it should be noted that all projects adopted a reinforcing narrative strategy, in that they were developed for a specific location, which has inherent value in itself, and the AR content merely seeks to complement and enrich the visitor's experience (Azuma, 2015).

Among the techniques applied to the content, the narrative voice-over style used in study 1 stands out, used to inform users and unify the three moments of the experience. To apply this technique, the authors studied the already established medium of cinema, particularly the documentary genre. This process of studying other media when creating content for a new medium is recommended, as established media have already validated practices that can serve as a reference (Craig, 2013; Jenkins, 2006).

Thus, voice-over narration was identified by end users as a positive strategy that engaged them with the environment and helped them retain information. However, it was noted that the female tone used was not very stimulating or appealing for the experience.

About interaction, it should be noted that in all studies, learning was considered the context of the activity, exclusively in study 3, aimed at supporting the basic education curriculum, and in the other projects, shared with the leisure scenario. This fact can be understood by the fact that the presentation of archaeological heritage requires scientific justification and that the expectations of visitors/users of these sites are more than just enjoyment. From the documents where users were evaluated together (1, 2, 3, and 4), the results indicated that the proof of concept developed helped users better understand the history of the site and retain information. Of the studies developed with practices aimed at serving learning, document 3 stands out, in which the Young Archaeologists project was designed with the purpose of increasing informal learning about the site. The most interesting aspect of this study is the fact that the system begins with a question about the site, which students must answer through video research using the tools provided by the app. In this case, AR helps explore the space through the Data Capture tool, which allows users to interact with the physical environment by superimposing virtual information onto it.

Still in the context of learning, study 4 stands out, where a serious games approach is incorporated into the Avebury Portal app to try to engage users with heritage. In this context, users solve puzzles and riddles through the site's PoI to receive AR content rewards.

Regarding the types of interaction, considering the five defined by Lueg et al. (2019) and Sharp et al. (2019), namely instruction, conversation, manipulation, exploration, and response, it was found that exploration was used in all projects, that is, there was a concern to make the user move through the physical and/or virtual space. In the case of documents 1, 3, and 4, there were predefined paths that users were required to follow to access new information and AR content. And in the case of studies 2 and 5, the exploration took place in front of the reconstruction of the artifact, which allowed the user to approach it to view it from different perspectives and access details.

The second most used interaction was the instruction, in documents 1, 2, and 3, employed thru virtual buttons on the interface and/or gesture commands, which were used to change functionality or stop and resume the AR experience. This dimension of interaction is classified as a way to give the user control over the experience (Liestøl et al., 2021), and it is noted that, although no form of instruction was indicated in documents 4 and 5, it does not mean that it is not integrated into the projects, since virtual buttons are one of the most basic forms of interaction in AR (Craig, 2013).

The manipulation and response were both used in two studies each, with the manipulation in documents 1 and 3 being at different degrees. Particularly in study 1, it was shared with the instruction, given that the manipulable 3D elements were buttons that led the user to another PoI, thus considering that here the manipulation was applied to a mild degree. While in project 3 the manipulation was used in a richer and more optimized way, allowing users to create digital content to overlay on the real environment.

In the case of the response, which appears in studies 3 and 4, it was introduced to encourage the user to use the app and incorporate the experience. In study 3, the project begins with this type of interaction, and in study 4, it appears based on the user's location and proximity to PoI thru haptic feedback, which serves to alert and encourage the resolution of proposed challenges. In the case of study 4, this type of interaction was considered by the evaluation participants as a positive aspect of the project.

The systematic review highlights the importance of developing AR apps for the on-site archeological context, alongside the exploration of the potential of AR media and strategies that have been granted for this specific scenario. However, it is necessary to mention that the study is subject to certain limitations, which include the limited types of documents included; the analysis based on the data presented in the documents, which is representative of the authors' perspective, being confined to what they consider most relevant; and in turn, the author's own perspective of the review, who despite attempting to weave an objective and rigorous analysis, structured it according to what she considers most pertinent to the study.

| 1 |

Efstathiou, I.; Kyza, E. A.; & Georgiou, Y. (2018). An inquiry-based augmented reality mobile learning approach to fostering primary school students’ historical reasoning in non-formal settings. Interactive Learning Environments, 26(1), 22–41. doi:10.1080/10494820.2016.1276076. |

Appendices

| No. |

Author(s) and Year |

Document language and typology |

Title and Objective(s) |

Archaeological context |

AR |

Interaction |

Methods or instruments |

Main results |

Risk of bias |

Notes |

| 01 |

Liestøl et al. (2021) |

Language: English

Document typology: article |

Title:Augmented Reality Storytelling Submerged. Dry Diving to a World War II Wreck at Ancient Phalasarna, Crete

Objective(s): An app using AR, called Phalasarna 1941 AR, aims to contextualize the location of Phalasarna and reconstruct the event related to the sinking of the Tank Landing Craft (TLC) A6 during World War II, to enhance historical understanding. Additionally, it intends to explore the technique of "dry diving" using AR technology. |

Site of the historic shipwreck of the vessel TLC A6 during World War II (Phalasarna, Greece) |

AR approach: Indirect augmented reality (IRA)

Registration process: location-based

Augmented senses: sight and hearing |

Activity context:

Learning and leisure

Type(s) of interaction:

Instructing – The user can pause and resume the AR experience using buttons and hand gestures.

Manipulating – During the "dry dive" scene, when you are on the wreckage of the vessel, the user can interact with elements that identify the most important milestones of this experience (note that this dimension is shared with the instruction, since the interaction is mostly through commands, i.e., the user clicks on that element and is taken to a new stop/piece of information).

Exploring – The user moves through the physical space to reach the location of the experience while listening to a narration of information about the space. And during the "dry dive" technique and the reconstruction of the event that led to the shipwreck in AR, the user can explore a virtual environment. |

- Case study, prototype

- Media design (adaptation of elements from the documentary genre and non-diegetic narration)

- Usability test with the app on-site.

There was a first attempt in June 2021, but it was canceled because it was too hot and there were problems with the brightness of the devices.

The second time, in October 2021, the evaluation took place with a sample of 6 participants/visitors. One of the project researchers accompanied the visitors throughout the project to observe and answer any questions that arose. At the end, the participants answered a questionnaire. |

- Adding sound effects to the experience can be very positive;

- Narration helped to unify the various moments of the experience;

- The narration voice was not very engaging with the experience;

- The experience helped users to better understand and engage with the story of the place. |

Low risk of bias: The article presents the complete process of development and evaluation of the project, as well as the concerns present throughout. |

|

| 02 |

Blanco-Pons et al. (2019) |

Language: English

Document typology: article |

Title: Design and implementation of an augmented reality application for rock art visualization in Cova dels Cavalls (Spain)

Objective(s): Develop an app that integrates AR for Cova dels Cavalls, in order to assist general visitors during guided tours of the site, so that they have more knowledge and sensitivity to the site.

Use AR for the reconstruction of compositions of rock art motifs. |

Cova dels Cavalls Cave (Tirig, Castellón, Spain), which is part of the group of rock art sites in the Mediterranean basin of the Iberian Peninsula, classified as a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). |

AR approach: Direct augmented reality (DAR)

Registration process: location-based

Augmented senses: sight |

Activity context:

Learning and leisure (guided tour)

Type(s) of interaction:

Instructing – There are three buttons that allow the user to access the current state, original state, and information about the paintings.

Exploring – Users can move around in the physical space and observe the paintings from different perspectives using AR.

|

- Case study, prototype

- On-site usability evaluation

Objective: To understand whether visitors without prior knowledge of cave paintings can better perceive the scenes depicted in the paintings, and to verify the quality and suitability of the app's design and functionality.

Sample: 11 volunteers, minimum age 31, almost all participants had university degrees (90.9%).

Participants tested the AR app in the cave and completed a survey. The survey was divided into two parts: 1 – Pre-questionnaire, to collect information from participants; 2 – AR app evaluation questionnaire, consisting of 15 questions. The scale used was the Likert scale, with 5 points, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. |

- AR improves the visualization, understanding, and recognition of rock art sites;

- The app was found to be easy to use during the evaluation;

- Great acceptance of AR as a tool for disseminating information about the paintings and improving the site visit experience;

- The app has increased interest in the site and its history;

- It allows attracting different groups of visitors;

- It raises awareness of the importance of preserving cultural heritage (concern about the deterioration of paintings and the need to conserve them). |

Low risk of bias: The article addresses the various stages, the problem, and the solution. A usability evaluation was conducted with volunteer end-users. |

It does not specify whether the questions used in the questionnaire were written by the authors or whether they were based on an existing framework. |

| 03 |

Kyza & Georgiou (2019) |

Language: English

Document typology: article |

Title: Scaffolding augmented reality inquiry learning: the design and investigation of the TraceReaders location-based, augmented reality platform

Objective(s): The document presents the TraceReaders platform, which refers to two case studies: “Young Archaeologists” and “Mystery at the Lake”. For this review, only the first, “Young Archaeologists”, will be considered, as it meets the archaeological criterion. Thus, the objective of this study was to develop an app using AR technology to enrich the teaching of primary school students, in an informal learning approach. |

Neolithic archaeological site of Choirokoitia (Lárnaca, Cyprus), considered a World Heritage Site by UNESCO |

AR approach: DAR

Registration process: location-based

Augmented senses: sight |

Activity context:

Learning (students have to create a video investigation that answers the question posed by the system)

Type(s) of interaction:

Instructing – There are at least seven buttons that allow access to the app's main features. (Notepad, Mission button, Data folder, Concept mapping tool, Chat tool, Hotspot map, Data capture tool).

Manipulating – The Data Capture feature allows students to interact with the physical space by adding layers of virtual information on top of the real world.

Exploring – There are five hotspots that guide students to the answer. Whenever they approach one of these points, they receive extra information about Neolithic practices.

Responding – The app begins with a video presenting a problem scenario with one question; in this case, the question was "Why did people in the Neolithic era decide to stay in this specific location?". The system poses the challenge/question, which students can accept or reject. |

- Case study

- Empirical/field study

Two studies were conducted, both following methods such as Efstathiou, Kyza, and Georgiou (2018)1

1st study

Sample: Experimental group: 24 third-grade students using the AR app. Control group: 29 third-grade students (from a different school than the experimental group), following the standard process of a field trip accompanied by teachers.

Objective: to assess historical empathy and conceptual understanding.

2nd study

Sample: A class of 23 fourth-grade students was studied. The students were divided into an experimental group of 12 students using an AR app that incorporated a concept mapping tool to help organize their ideas, and a control group of 11 students using the AR app without this functionality.

Objective: to investigate the role of functionality concept mapping. |

-Results of the 1st study: There is greater historical empathy for the students in the experimental group, and learning was superior compared to the control group.

-Results of the 2nd study: Indicate that the experimental group with the concept map managed to gather a superior set of notions related to the problem than the control group. The concept map facilitated collaborative discourse among the students and the reflective construction of knowledge. |

Low risk of bias: The app is well explained and provides a detailed assessment of the impacts of AR. |

|

| 04 |

Shakouri & Tian (2019) |

Language: English

Document typology: conference paper |

Title: Avebury Portal – A Location-Based Augmented Reality Treasure Hunt for Archaeological Sites

Objective(s): Development of an AR-based app, called Avebury Portal, considered a fantasy game for users aged 16 to 24. The app aims to provide information using contextual learning, encouraging the user to explore and discover ancient artifacts on site, following a logic of finding virtual treasures at the location.

The system uses location to provide clues throughout the narrative, create puzzles, and guide the user with a "smart map" that displays points of interest (PoI). |

Avebury, a Neolithic stone circle (Wiltshire, England), is a UNESCO World Heritage Site |

AR approach: DAR

Registration process: location-based

Augmented senses: sight |

Activity context:

Learning and leisure (visit to the site)

Type(s) of interaction:

Exploring – The user moves around the physical site, and when they pass near a Point of Interest (POI), the app notifies them to scan the site and solve the puzzle or riddle. The reward for solving the challenge is informative AR content.

Responding – Initially, the app advises the user to move to the start of the treasure hunt (first Point of Interest). The system then notifies the user whenever they approach a Point of Interest, using haptic feedback.

|

- Case study, prototype

- Triangulation methodology

Data collection: The participants had to complete the treasure hunt in 1 hour, with the understanding that they could quit whenever they wanted. At the end, the participants were interviewed and filled out a questionnaire.

Sample: 18 participants.

12 of the 18 participants had visited Avebury before, and 5 participants were archaeologists working at the site.

|

-Participants responded positively to all statements in the questionnaire, except for the statement "I am lost," a negative aspect that was reinforced by the researcher's observation that identified signs in the participants that they were confused and frustrated when trying to locate the PoI (which means that the alternative could be to end the "smart map" and implement a navigation system in the app to better guide users);

- The app is considered to have had a positive impact on the user experience when visiting Avebury;

- Participants praised the AR content and agreed that it encouraged their visit to the site;

- The information given as clues was clear to users, and they felt that the animations and puzzles were informative and engaging.-O sistema deve ser melhorado em termos de tracking markeless 3D, para criar uma dimensão virtual com que os utilizadores interajam. |

Low risk of bias: The article presents the development, identified strengths and weaknesses. |

There could have been more data regarding the assessment performed, and the sample could have been segmented into participants who were already familiar with the site, participants who were unfamiliar with the site, and experts in the field. They don't explain how they selected the participants. |

| 05 |

Berlino et al. (2019) |

Language: English

Document typology: conference paper |

Title: Augmented reality for the enhancement of archaeological heritage: A Calabrian experience

Objective(s): Mobile application for promoting PoI (Protected Historical Sites) in the archaeological park.

Reconstruction of the site's ancient structures. |

Castiglione di Paludi Archaeological Park (Paludi, Italy) |

AR approach: DAR

Registration process: Marker-based (fiducial markers in PoI)

Augmented senses: sight |

Activity context:

Learning and leisure (visit to the site)

Type(s) of interaction:

Exploring – The user moves through the PoI in physical space and, via fiducials, accesses a layer of information, 3D content, that allows them to observe what the environment was like in perfect condition. And when approaching the virtual reconstruction, they can observe details and view the model from different perspectives as they move through physical space. |

- Case study, implemented product

- Does not mention any evaluation conducted with end users. |

- To contribute to highlighting/enhancing cultural tourism.

- To promote PoI (Protected Design of Life) in the archaeological park. |

Some concerns: the document describes how the app is used on the site and its contribution to tourism development, but it does not mention any studies or evaluations that corroborate the advantages of implementing the app. |

|

Table 1.

Year of publication of the documents included in the analysis

Table 1.

Year of publication of the documents included in the analysis

| Year of publication |

Absolute frequency |

Relative frequency |

| 2019 |

4 |

80% |

| 2021 |

1 |

20% |

Graphic 1.

Year of publication of the documents included in the analysis

Graphic 1.

Year of publication of the documents included in the analysis

Table 2.

Types of documents included in the analysis

Table 2.

Types of documents included in the analysis

| Types of documents |

Absolute frequency |

Relative frequency |

| Article |

3 |

60% |

| Conference paper |

2 |

40% |

Graphic 2.

Types of documents included in the analysis

Graphic 2.

Types of documents included in the analysis

Table 3.

AR approach used in analysis documents

Table 3.

AR approach used in analysis documents

| AR approach |

Absolute frequency |

Relative frequency |

| Indirect |

1 |

20% |

| Direct |

4 |

80% |

Graphic 3.

AR approach used in analysis documents

Graphic 3.

AR approach used in analysis documents

Table 4.

Registration process applied to analysis documents

Table 4.

Registration process applied to analysis documents

| Registration process |

Absolute frequency |

Relative frequency |

| Location-based |

4 |

80% |

| Marker-based |

1 |

20% |

Graphic 4.

Registration process applied to analysis documents

Graphic 4.

Registration process applied to analysis documents

Table 5.

Augmented senses in RA in analysis documents

Table 5.

Augmented senses in RA in analysis documents

| Augmented senses |

Absolute frequency |

Relative frequency |

| Vision |

4 |

80% |

| Vision and hearing |

1 |

20% |

Graphic 5.

Augmented senses in RA in analysis documents

Graphic 5.

Augmented senses in RA in analysis documents

Table 6.

Context of the interaction activity of the analysis documents

Table 6.

Context of the interaction activity of the analysis documents

| Context of the interaction |

Absolute frequency |

Relative frequency |

| Learning and leisure |

4 |

80% |

| Learning |

1 |

20% |

Graphic 6.

Context of the interaction activity of the analysis documents

Graphic 6.

Context of the interaction activity of the analysis documents

Table 7.

Types of interaction applied in analysis documents

Table 7.

Types of interaction applied in analysis documents

| Types of interaction |

Absolute frequency |

Relative frequency |

| Instructing |

3 |

60% |

| Manipulating |

2 |

40% |

| Exploring |

5 |

100% |

| Responding |

2 |

40% |

Graphic 7.

Types of interaction applied in analysis documents

Graphic 7.

Types of interaction applied in analysis documents

References

- Abate, A.F.; Barra, S.; Galeotafiore, G.; Díaz, C.; Aura, E.; Sánchez, M.; Mas, X.; & Vendrell, E. (2018). An Augmented Reality Mobile App for Museums: Virtual Restoration of a Plate of Glass (pp. 539–547). [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, A.; Lepouras, G.; Kastritsis, A.; Diakoumakos, J.; Aggelakos, Y.; & Platis, N. (2020, September 29). “Take me Home”: AR to Connect Exhibits to Excavation Sites. AVI 2CH 2020.

- Ashmore, W.; & Sharer, R. (2010). Discovering Our Past: A Brief Introduction to Archaeology (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Azuma, R. A Survey of Augmented Reality. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 1997, 6, 355–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, R.; Baillot, Y.; Behringer, R.; Feiner, S.; Julier, S.; & MacIntyre, B. Recent advances in augmented reality. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications 2001, 21, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, R.T. (2015). Location-Based Mixed and Augmented Reality Storytelling. In W. Barfield (Ed.), Edition of Fundamentals of Wearable Computers and Augmented Reality (2nd ed., pp. 259–276). CRC Press.

- Barrile, V.; Fotia, A.; Bilotta, G.; & de Carlo, D. Integration of geomatics methodologies and creation of a cultural heritage app using augmented reality. Virtual Archaeology Review 2019, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrile, V.; Fotia, A.; Candela, G.; & Bernardo, E. Geomatics Techniques for Cultural Heritage Dissemination in Augmented Reality: Bronzi di Riace Case Study. Heritage 2019, 2, 2243–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrile, V.; Fotia, A.; Ponterio, R.; Mollica Nardo, V.; Giuffrida, D.; & Mastelloni, M.A. A combined study of art works preserved in the archaeological museums: 3d survey, spectroscopic approach and augmented reality. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, XLII-2/W11, 201–207. [CrossRef]

- Berlino, A.; Caroprese, L.; Marca, A.; Vocaturo, E.; & Zumpano, E. (2019). Augmented Reality for the Enhancement of Archaeological Heritage: a Calabrian Experience. VIPER 2020.

- Blanco-Pons, S.; Carrión-Ruiz, B.; & Lerma, J.L. Augmented reality application assessment for disseminating rock art. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2019, 78, 10265–10286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Pons, S.; Carrión-Ruiz, B.; Luis Lerma, J.; & Villaverde, V. Design and implementation of an augmented reality application for rock art visualization in Cova dels Cavalls (Spain). Journal of Cultural Heritage 2019, 39, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botrugno, M.C.; D’Errico, G.; & de Paolis, L.T. (2017). Augmented Reality and UAVs in Archaeology: Development of a Location-Based AR Application (pp. 261–270). [CrossRef]

- Cisternino, D.; Gatto, C.; & de Paolis, L.T. (2018). Augmented Reality for the Enhancement of Apulian Archaeological Areas (pp. 370–382). [CrossRef]

- Clarivate. (2018, June 27). Web of Science Core Collection: Explanation of peer reviewed journals. Clarivate. https://support.clarivate.com/ScientificandAcademicResearch/s/article/Web-of-Science-Core-Collection-Explanation-ofpeer-reviewed-journals?language=en_US.

- Craig, A. (2013). Understanding Augmented Reality. Morgan Kaufmann. http://digilib.stmik-banjarbaru.ac.id/data.bc/12. Enterprise Architecture/12. Enterprise Architecture/2013 Understanding Augmented Reality.

- Fritsch, D.; & Klein, M. (2017). 3D and 4D modeling for AR and VR app developments. 2017 23rd International Conference on Virtual System & Multimedia (VSMM), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Savović, J.; Page, M.; Elbers, R.; & Sterne, J. (2021). Chapter 8: Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies. In J. Higgins, J. Thomas, J. Chandler, M. Cumpston, T. Li, M. Page, & V. Welch (Eds.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Vol. version 6.2. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://training.cochrane.

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press.

- Kyza, E.A.; & Georgiou, Y. Scaffolding augmented reality inquiry learning: the design and investigation of the TraceReaders location-based, augmented reality platform. Interactive Learning Environments 2019, 27, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laato, S.; & Laato, A. Augmented Reality to Enhance Visitors’ Experience at Archaeological Sites. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing 2020, 1160, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liestøl, G.; Bendon, M.; & Hadjidaki-Marder, E. Augmented Reality Storytelling Submerged. Dry Diving to a World War II Wreck at Ancient Phalasarna, Crete. Heritage 2021, 4, 4647–4664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueg, C.; Banks, B.; Michalek, J.; Dimsey, J.; & Oswin, D. Close Encounters of the Fifth Kind: Recognizing System-Initiated Engagement as Interaction Type. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2019, 70, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaf, M.; Drap, P.; Ben-Ellefi, M.; Nocerino, E.; Chemisky, B.; Chassaing, T.; Colpani, A.; Noumossie, V.; Hyttinen, K.; Wood, J.; Gambin, T.; & Sourisseau, J.C. Using Virtual or Augmented Reality for the Time-based Study of Complex Underwater Archaelogical Excavations. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, VIII-M-1–2021, 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Norman, D.A. (2004). Emotional design: why we love (or hate) everyday things. Basic Books.

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; … Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pangilinan, E.; Lukas, S.; & Mohan, V. (2019). Creating Augmented and Virtual Realities: Theory and Practice for Next-Generation Spatial Computing. O’Reilly Media.

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster University. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; & Soares, A. (2019, December). O fim e o princípio. Electra 8, 5–9. https://www.fundacaoedp.pt/sites/edpmaat/files/2020-04/Electra%208%20PT.pdf.

- Scopus. (n.d.). About Scopus. Scopus. Retrieved January 2, 2022, from https://blog.scopus.com/about.

- Seidametova, Z.; Abduramanov, Z.; & Seydametov, G. (2021, May 11). Using augmented reality for architecture artifacts visualizations. AREdu 2021: 4th International Workshop on Augmented Reality in Education.

- Shakouri, F.; & Tian, F. (2019). Avebury Portal – A Location-Based Augmented Reality Treasure Hunt for Archaeological Sites. Edutainment 2018: The 12th International Conference on E-Learning and Games, 39–49. [CrossRef]

- Sharp, H.; Preece, J.; & Rogers, Y. (2019). Interaction Design: beyond human-computer interaction (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Timothy, D.J.; & Boyd, S.W. Heritage Tourism in the 21st Century: Valued Traditions and New Perspectives. Journal of Heritage Tourism 2006, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlahakis, V.; Ioannidis, M.; Karigiannis, J.; Tsotros, M.; Gounaris, M.; Stricker, D.; Gleue, T.; Daehne, P.; & Almeida, L. Archeoguide: An Augmented Reality Guide for Archaeological Sites. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications 2002, 22, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).