1. Introduction

The diffusion of aluminium (Al) in copper (Cu) and Cu-based alloys plays a critical role in the processing and performance of these materials [

1,

2]. Aluminium bronzes [

3], widely used for their excellent mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, and thermal stability, rely on a controlled diffusion behaviour to achieve uniform microstructures and desired phase distributions. Understanding the diffusion kinetics is also essential for electronic applications [

4], where interdiffusion at Cu/Al interfaces can lead to the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds, increased electrical resistance, and potential device failure. Moreover, the Al diffusion is important for industrial applications such as resistance spot welding of technical alloys like AlMg3 [

5]. The associated formation of brittle intermetallic phases in combination with pronounced aluminium oxide layers may result in unwanted heat generation due to high current densities during welding. The rapid degradation of copper welding electrodes represents the main challenge when processing aluminium materials using resistance spot welding. Consequently, a fundamental knowledge of Al diffusion in Cu and technical Cu alloys is of importance.

The diffusion in metals has been studied for various reasons for almost two centuries [

6], underpinning phenomena such as homogenization, precipitation, aging, and deterioration [

7]. While Al tracer diffusion in pure Cu was investigated at temperatures above 700 °C, this is not the case for lower temperatures. Also, the influence of the native duplex oxide layer (Cu

2O/CuO) [

8] that invariably forms at copper surfaces is less clear. In the present case, we focus on Al tracer diffusion in a technical copper alloy containing approximately 0.5 – 1.2 wt.-Cr and 0.03 - 0.3 wt.-% Zr (CuCr1Zr) [

9], which is commonly used as electrodes for resistance spot welding of alloys like AlMg3. Here, diffusion processes at the contact area and into the Cu alloy play an important role. With an increasing number of weld cycles, reactive diffusion processes occur at the contact area. This results in a significant reduction of the electrical and thermal conductivity of the electrode working faces. This is due to the formation of alloys and intermetallic phases in the Al-Cu system with high electrical resistances and a continuous degradation of the electrode. Consequently, reliable diffusion data at temperatures around 600 °C, relevant for the welding process, have to be known for a deepened understanding.

The aim of the present paper is the study of Al diffusion in the CuCr1Zr alloy and the comparison to literature data for Cu at higher temperatures. Consequently, we carried out Al tracer diffusion experiments between 500 – 700 °C (773 – 973 K) and analysed the resulting concentration profiles with Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (SIMS).

Up to now, classical tracer diffusion experiments of Al in Cu are not known. Solid-state interdiffusion studies in the Cu-rich solid solution range of the Al-Cu system were performed above ~ 700 °C to achieve practical experimental timescales allowing the use of Energy-dispersive X-ray Analysis (EDX) line scans [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Matsuno and Oikawa [

10] measured interdiffusion coefficients of Cu-rich fcc alloys using a Cu/Cu – 12.2 at.% Al diffusion couples between 700 – 1000 °C and extracted Al tracer diffusivities from the results. Oikawa et al. [

12] did similar experiments. Laik et al. [

13] examined solid-state diffusion in the Cu-rich solid solution using a single-phase bulk diffusion couple (Cu versus Cu – 10 at.% Al) within the range of 750 – 950 °C. Notably, the Al diffusivities extracted from the interdiffusion experiments reported at the same temperature (e.g., ~ 800 °C) and at the same composition differ not much for the given studies. However, due to the Arrhenius law temperature dependence of the diffusivities, inconsistencies may emerge when extrapolation to lower temperatures is done. By conducting Al tracer diffusion experiments between 500 – 700 °C, discrepancies with high-temperature literature can be revealed. Further, possible differences between diffusion in pure Cu and the CuCr1Zr alloy can be detected.

2. Basic Considerations

The migration of aluminium atoms through a copper lattice is a thermally activated process governed by the availability of vacant lattice sites and a concentration gradient. In face-centered cubic (fcc) metals like copper, the substitutional vacancy mechanism is dominant for similarly sized atoms like aluminium [

15]. This process occurs when a diffusing atom moves into an adjacent, empty lattice site, known as a vacancy. The overall diffusion rate is therefore dependent on both, the concentration of vacancies and the frequency of atomic jumps into these vacancies. This atomic flux is macroscopically described by Fick's first law, which states that the net movement of atoms is proportional to the concentration gradient d

c/d

x [

6]. To analyse how the concentration profile evolves over time, Fick's second law is used. For a diffusion couple, where a limited source of aluminium atoms diffuse into a much larger extended copper substrate, a semi-infinite solution to Fick's second law can be applied to describe experimental concentration profiles and extract the diffusivity,

D [

6]. The strong dependence of the diffusivity on temperature (

T) is quantified by the Arrhenius relationship

D =

D0·exp(−

DH/(k

T)), where

D0 is the pre-exponential factor,

DH is the activation enthalpy of diffusion and

k is the Boltzmann constant. The activation enthalpy represents the energy barrier for the diffusion process, combining the enthalpy for the formation of a vacancy and for the migration of it. This relationship is consistently used to model diffusion in Cu–Al systems, where

D is determined at various temperatures to calculate

DH from an Arrhenius plot [

6].

At the surface of pure copper or of a copper-rich technical alloy, a duplex oxide layer is commonly developing in air [

8]. It consists of an inner cuprous oxide (Cu

2O) and an outer cupric oxide (CuO), whose composition and stability are highly dependent on thermal history. At ambient temperatures, a native oxide primarily composed of Cu

2O forms over time [

16]. Thermal oxidation promotes the growth of the bilayer, with the relative thickness of each phase controlled by temperature and time. Oxidation at temperatures around 300 °C produce a passivating mixed layer of Cu

2O and CuO [

17]. Thermodynamically, both copper oxides are susceptible to reduction at elevated temperatures, a critical consideration for the Al–Cu interface. Given the strong affinity Al to O, it possible to readily reduce interfacial copper oxides present during diffusion annealing, forming a stable aluminium oxide (Al

2O

3) layer and metallic copper at the interface. Under the assumption that the diffusion in each of the possible oxide layers is low [

18,

19], the layer might be an obstacle for the atoms reaching the Cu layer. The overall diffusion flux across a multi-layered structure can therefore be modelled as a series of resistances, where a single thin layer with low diffusivity can act as the rate-limiting barrier. When a dense interfacial oxide is present, the overall diffusion of Al into Cu might be controlled not by bulk diffusion in the metal, but by the significantly lower atomic transport rates through the oxide barrier.

3. Experimental

Cylindrical specimens (15 mm diameter, 1 mm thickness) were cut from an extruded CuCr1Zr stock by wire erosion. The material is polycrystalline with grain sizes of 80 – 200 μm. Both faces were ground, and one face was polished with a 1 μm diamond suspension to serve as the tracer deposition surface. After contact of the CuCr1Zr sample with air a native oxide layer is expected to be formed. The natural oxide chemistry was verified by X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy on Cu [

20]. The thickness of the native oxide layer is commonly assumed to be a few nanometres [

21]. In addition, samples with a thermally grown oxide layer were produced by exposing them to oxygen (O

2 flow of 40 ml/min) at 300 °C for 20 min. Commonly, this results in an oxide layer with at least several tens to one hundred of nanometre [

22] .

On top of the polished surface, a 100 – 200 nm Cu – 8.8 at.% Al tracer layer was deposited by ion-beam sputter deposition (IBSD; Gatan Model 681) using a high-purity target (> 99.99%). This layer with an Al concentration within the solid solubility range of Cu severs as a tracer layer.

The samples with the tracer layer were annealed between 500 – 700 °C for durations of 30 s up to 5130 s. For T ≤ 600 ° C, a rapid thermal annealing system (MBE Komponenten AO 600, up to 50 K/s ramp rate) was used. Treatments at 700 °C were done using a muffle furnace (Nabertherm LE 1/11/R6) located in an Ar filled glove-box. All anneals were conducted in flowing argon to prevent oxidation of the whole samples.

SIMS depth profiling (CAMECA IMS–3F) was used to measure depth-dependent elemental distributions of Al and Cu. An O− primary ion beam at 15 keV and ~100 – 150 nA was scanned over an area of 250 μm × 250 μm. Secondary ions were collected from the central 60 μm × 60 μm area to reduce crater-edge effects. Ion signals were recorded as a function of time in a double-focused mass spectrometer. Depth scales were established by measuring the sputter crater depth with a mechanical profilometer (Tencor Alphastep D 500), enabling conversion from acquisition time to sputter depth. It is assumed that the secondary ion SIMS signal is proportional to the Al concentration. We are aware that this assumption is only approximate, while matrix effects associated with different ionization probability and the changing sputter yield of secondary ions may play an important role by sputtering across multi-layer samples and interfaces. However, the absolute values of Al concentration are not relevant for the extraction of diffusivities as will be shown below.

For an analysis of the Al SIMS depth profiles, the diffusion of a thin tracer layer of initial thickness h on top of a semi-infinite sample was applied. Within in this model, the concentration profile c(x, t) after time t at sputter depth x is given by [

6]

where c

1 is the initial surface concentration of Al and c

0 is the bulk concentration of Al in the CuCr1Zr sample, which is very close to zero. Instead of concentration we used the normalized SIMS secondary signal for analysis. The diffusion length R is determined from this equation as a fit parameter by comparing as-deposited (R) and annealed sample (R). The diffusivity can be calculated using D = (R

2 – R

02)/(4 t) without knowledge of the concentrations.

4. Results and Discussion

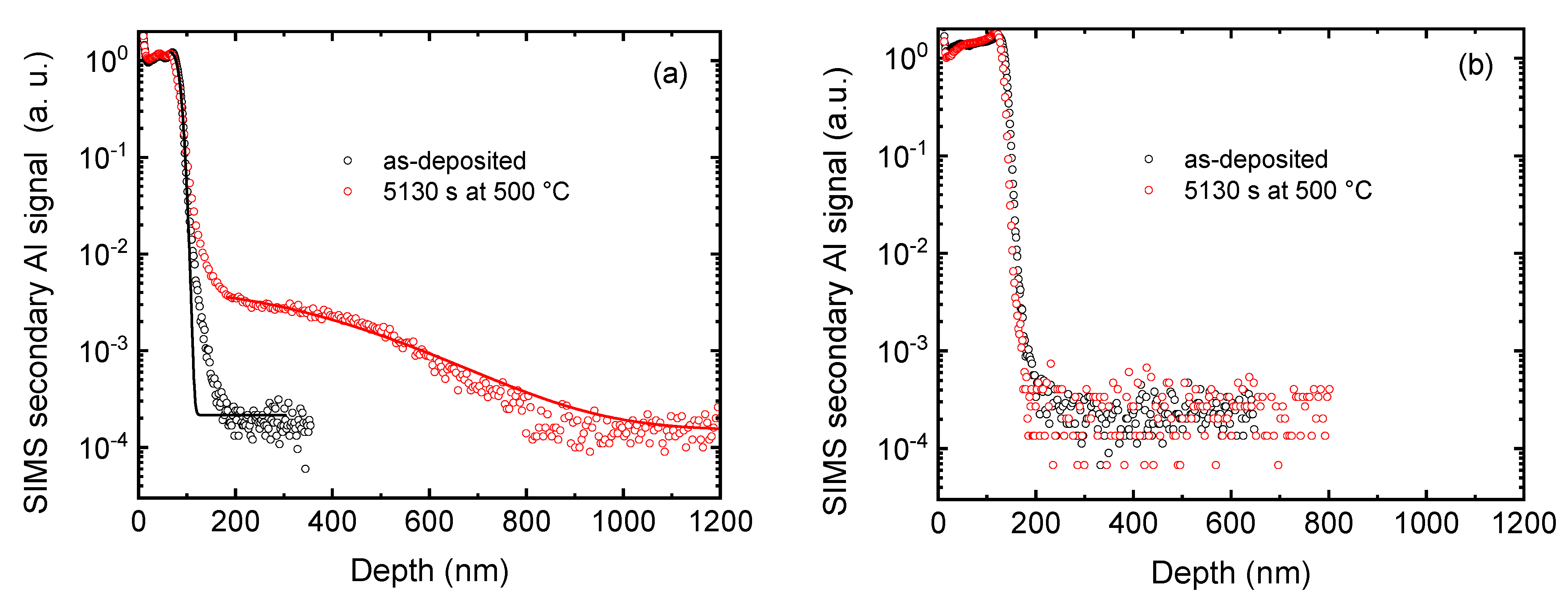

A typical SIMS depth profile of Al after deposition and after annealing is shown in

Figure 1(a). The Al rich tracer layer in the as-deposited state is clearly visible in a surface region of about 100 nm. After annealing, Al penetrates into the Cu alloy sample. However, this does not occur over the whole Al concentration range but is limited to low concentrations below 1 % of the maximum concentration. The rest of the profile is nearly unchanged. We interpret this behaviour to be the result of the oxide layer located at the surface with a thickness of several single manometer. This metal oxide layer slows down Al diffusion inside, limiting the transport across the surface as discussed above. However, the Al atoms crossing the surface layer can freely migrate into the Cu alloy, what can be detected by SIMS. For a deeper investigation we carried out an experiment where a thicker oxide layer of several tens of nanometre was thermally grown at the surface. The result is shown in

Figure 1(b). For the same diffusion time we observe no diffusion at all, emphasizing the blocking effect of the oxide layer due to slow diffusion. The Al atoms cannot cross the thicker barrier in the given time period.

The profiles of

Figure 1(a) are fitted using equation (1). The fitting curves are also shown in

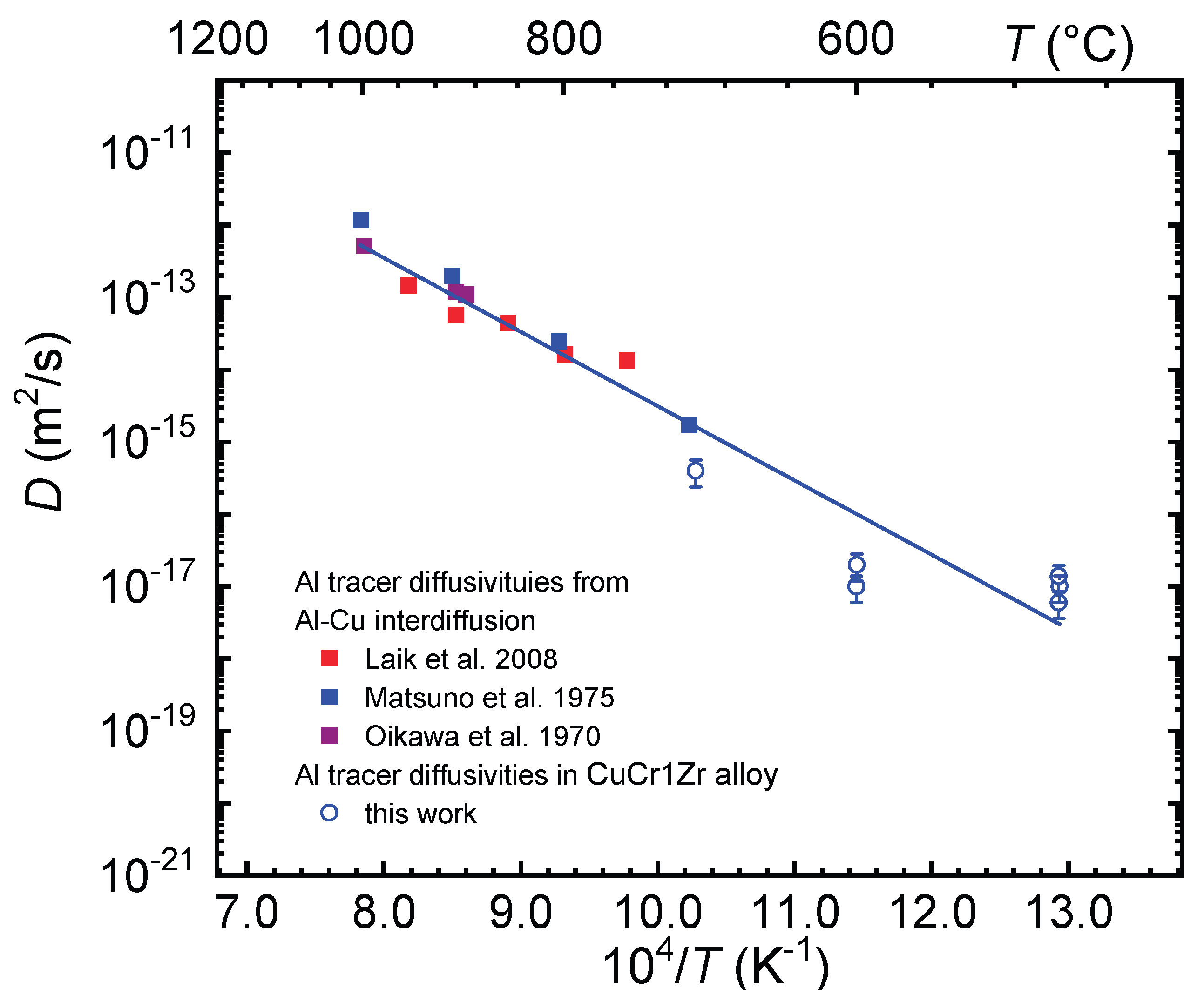

Figure 1(a) as solid lines. For the annealed sample only the part of the profile where diffusion in the Cu alloy occurs is fitted, while the initial thickness of the Al layer h is kept constant. As a result, we obtain the diffusivities as given in the Arrhenius plot in

Figure 2. The Al diffusivities increase with growing temperature.

Figure 2 also correlates our diffusivity results to literature data on Al tracer diffusivities extracted from interdiffusion data of Cu – Al alloys above 700 °C [

10,

12,

13]. These tracer diffusivities correspond to pure Cu or Al-poor Cu-Al alloys as indicated in the caption of

Figure 2. When comparing literature datasets only within a limited, high-temperature range between 700 and 1000 °C, the reported diffusivities are nearly identical within a factor of only three within normal experimental scatter.

For further comparison we use the data of Matsuno et al. [

10]. These diffusivities are also strongly temperature dependent. The diffusivities derived in the present study, agree best with the extrapolation of the data of Matsuno et al. A combination of these data with the tracer diffusivities obtained in this work can be well described with the Arrhenius law

A common fitting of both data sets gives an activation enthalpy of H = (2.0 ± 0.2) eV and a pre-exponential factor of D

0 = 3.9 x 10

-5 m

2/s (error: ln (D

0 /(m

2/s)) = -4.4 ± 1.16). Such an activation enthalpy is typical for substitutional diffusion in Cu [

23]. These findings confirm that Al diffusion in CuCr1Zr is governed by the same thermally activated vacancy mechanism as observed in pure copper. The relatively large scatter of our data around the Arrhenius line has to be further investigated.

5. Conclusions

This study provides insight into the atomic-scale diffusion behaviour of aluminium in CuCr1Zr alloys, which are commonly used as electrodes in resistance spot welding applications. Through SIMS based Al tracer diffusion experiments and the use of literature data, it was established that Al diffusion follows a clear temperature dependence consistent with the Arrhenius law between 500 and 1000 °C. An activation enthalpy of approximately 2 eV is derived. These findings confirm that Al diffusion in CuCr1Zr is governed by a thermally activated vacancy mechanism similar to those observed in pure copper. Moreover, the observed influence of the surficial oxide layer highlights the importance of surface conditions in controlling diffusion kinetics.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) in the framework of the project SCHM 1569/40-1 and WE 2846/31-1 (number: 464385838) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- K. Liu, H. Yu, X. Li, S. Wu, Study on diffusion characteristics of Al-Cu systems and mechanical properties of intermetallics, J. Alloys Compd. 874 (2021) 159831. [CrossRef]

- D. Kim, K. Kim, H. Kwon, Investigation of Formation Behaviour of Al–Cu Intermetallic Compounds in Al–50vol%Cu Composites Prepared by Spark Plasma Sintering under High Pressure, Materials 14 (2021) 266. [CrossRef]

- U. Donatus, J.A. Omotoyinbo, I.M. Momoh, Mechanical Properties and Microstructures of Locally Produced Aluminium-Bronze Alloy, J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng. 11 (2012) 1020.

- J. Ling, T. Xu, R. Chen, O. Valentin, C. Luechinger, Cu and Al-Cu composite-material interconnects for power devices, in: 2012 IEEE 62nd Electron. Compon. Technol. Conf., 2012: pp. 1905–1911. [CrossRef]

- S. Brechelt, H. Wiche, J. Junge, R. Gustus, H. Schmidt, V. Wesling, Increase of electrode life in resistance spot welding of aluminum alloys by the combination of surface patterning and thin-film diffusion barriers, Weld. World 67 (2023) 2703–2714. [CrossRef]

- H. Mehrer, Diffusion in Solids: Fundamentals, Methods, Materials, Diffusion-Controlled Processes, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2007. https://books.google.de/books?id=IUZVffQLFKQC.

- D. Liu, L. Zhang, Y. Du, H. Xu, S. Liu, L. Liu, Assessment of atomic mobilities of Al and Cu in fcc Al–Cu alloys, Calphad 33 (2009) 761–768. [CrossRef]

- G. Garnaud, The formation of a double oxide layer on pure copper, Oxid. Met. 11 (1977) 127–132. [CrossRef]

- M. Karlík, P. Haušild, P. Pilvin, D. Carron, Evolution of the Microstructure of a CuCr1Zr Alloy during Direct Heating by Electric Current, Metals 11 (2021) 1074. [CrossRef]

- N. Matsuno, H. Oikawa, Interdiffusion in copper-base Cu-AI solid solutions, Metall. Trans. A 6 (1975) 2191. [CrossRef]

- H. Oikawa, T. Obara, S. Karashima, Interdiffusion coefficients in copper-rich aluminum solid solutions, Metall. Trans. 1 (1970) 2969–2970. [CrossRef]

- H. Oikawa, S. Karashima, On the self-diffusion coefficients of aluminum in copper (rich)-aluminum solid solutions, Trans. Jpn. Inst. Met. 11 (1970) 431–433.

- Laik, K. Bhanumurthy, G.B. Kale, Diffusion in Cu (Al) solid solution, in: Defect Diffus. Forum, Trans Tech Publ, 2008: pp. 63–69. https://www.scientific.net/DDF.279.63 (accessed November 20, 2024).

- T. Takahashi, M. Kato, Y. Minamino, T. Yamane, Interdiffusion in α Solid Solutions of Cu–Al–Zn System, Trans. Jpn. Inst. Met. 26 (1985) 462–472. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Ven, H.-C. Yu, G. Ceder, K. Thornton, Vacancy mediated substitutional diffusion in binary crystalline solids, Prog. Mater. Sci. 55 (2010) 61–105. [CrossRef]

- J.J. Díaz León, D.M. Fryauf, R.D. Cormia, N.P. Kobayashi, Study of the formation of native oxide on copper at room temperature, in: N.P. Kobayashi, A.A. Talin, M.S. Islam, A.V. Davydov (Eds.), San Diego, California, United States, 2016: p. 99240O. [CrossRef]

- V.-H. Castrejón-Sánchez, A.C. Solís, R. López, C. Encarnación-Gomez, F.M. Morales, O.S. Vargas, J.E. Mastache-Mastache, G.V. Sánchez, Thermal oxidation of copper over a broad temperature range: towards the formation of cupric oxide (CuO), Mater. Res. Express 6 (2019) 075909. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Rebane, N.V. Yakovlev, D.S. Chicherin, Y. d Tretyakov, L.I. Leonyuk, V.G. Yakunin, An experimental study of copper self-diffusion in CuO, Y2Cu2O5 and YBa2Cu3O7–x by secondary neutral mass spectrometry, J. Mater. Chem. 7 (1997) 2085–2089. [CrossRef]

- A.H. Heuer, Oxygen and aluminum diffusion in α-Al2O3: How much do we really understand?, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 28 (2008) 1495–1507. [CrossRef]

- V. Udachin, L. Wegewitz, S. Dahle, W. Maus-Friedrichs, Reduction of copper surface oxide using a sub-atmospheric dielectric barrier discharge plasma, Appl. Surf. Sci. 573 (2022) 151568.

- P. Keil, D. Lützenkirchen-Hecht, R. Frahm, Investigation of Room Temperature Oxidation of Cu in Air by Yoneda-XAFS, AIP Conf. Proc. 882 (2007) 490–492. [CrossRef]

- S.R. Esa, R. Yahya, A. Hassan, G. Omar, Nano-scale copper oxidation on leadframe surface, Ionics 23 (2017) 319–329. [CrossRef]

- G. Neumann, C. Tuijn, Self-diffusion and Impurity Diffusion in Pure Metals: Handbook of Experimental Data, Elsevier, 2011.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).