1. Introduction

Global water scarcity has become one of the defining environmental challenges of the twenty-first century. With the global population expected to reach 9.9 billion by 2050, freshwater demand is projected to increase by 20–30% within the next three decades [

1,

2]. Presently, over two billion people already live in regions experiencing high water stress, a condition that is worsening due to the combined effects of urbanization, industrialization, and climate change [

3]. In addition to quantitative depletion, freshwater systems face serious qualitative degradation caused by the uncontrolled discharge of nutrient-rich effluents. These twin crises of scarcity and pollution demand sustainable approaches that conserve water while simultaneously recovering resources from waste streams.

Among the key contributors to nutrient pollution, the food service sector—particularly institutional kitchens, canteens, and restaurants—has expanded rapidly over the past two decades. This has led to a proportional increase in the generation of canteen wastewater (CW), characterized by high concentrations of biodegradable organic matter, fats, oils, and nutrients such as nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) [

4]. The nutrient and organic loads in CW are often higher than those in domestic sewage, containing proteins, starches, and detergents from dishwashing and food residues [

5]. If discharged untreated, CW contributes directly to eutrophication, algal blooms, and oxygen depletion in receiving water bodies [

6,

7]. In developing regions lacking centralized wastewater treatment infrastructure, direct disposal of canteen effluents is common, causing blockages from fats, oils, and grease (FOG) and aggravating both ecological and public health risks [

8,

9].

Despite its environmental burden, CW represents an underutilized resource due to its nutrient richness. The high concentrations of N and P make it a potential feedstock for biological valorization, especially through microalgae-based systems. Conventional synthetic culture media such as BG-11 or Zarrouk’s medium provide reliable results for laboratory-scale microalgal growth but are prohibitively expensive and resource-intensive for large-scale use [

10,

11]. Repurposing CW as an algal cultivation substrate can therefore achieve dual benefits—nutrient removal and biomass generation—while advancing the principles of the circular bioeconomy, in which waste is transformed into value-added products [

12,

13].

Microalgae have long been recognized as efficient agents for wastewater treatment because of their ability to assimilate inorganic nutrients while generating high-value biomass [

14,

15]. Compared with conventional treatment systems, algal-based processes are more energy-efficient, carbon-sequestering, and capable of producing a wide range of bioproducts such as pigments, lipids, and proteins. Among the various microalgal species, Spirulina (genus Arthrospira) stands out for its robustness, rapid growth, and exceptional biochemical composition [

19,

20]. It can tolerate wide fluctuations in pH, salinity, and ammonia, conditions that often limit the growth of other microalgae. Spirulina biomass typically contains 60–70% protein by dry weight, along with vitamins, essential amino acids, and bioactive pigments [

5]. Of particular interest are carotenoids, lipid-soluble antioxidants with applications in food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries [

21,

22]. Compounds such as β-carotene and zeaxanthin can constitute up to 1–1.5% of dry biomass under optimized conditions and are known for their role in vision health, immune regulation, and oxidative stress mitigation [

23]. Growing consumer demand for natural pigments has created a rapidly expanding global carotenoid market [

24], reinforcing the economic incentive to develop sustainable algal production systems.

Carotenoid accumulation in Spirulina is highly responsive to environmental and nutritional factors, including light intensity, nitrogen and phosphorus availability, and oxidative stress [

25,

26]. Hence, the nutrient-rich but variable composition of CW offers a unique opportunity to couple bioremediation with carotenoid enrichment through controlled cultivation. Previous studies have reported promising results using various wastewater sources—municipal, aquaculture, piggery, and dairy effluents—for Spirulina cultivation [

15,

16,

27]. However, systematic investigations of canteen wastewater remain scarce, despite its consistent composition and widespread availability in institutional settings [

4]. This research gap limits the practical deployment of algae-based systems for treating food-service wastewater.

Valorizing canteen wastewater via Spirulina cultivation offers distinct environmental and economic advantages. Conventional treatment technologies, including activated sludge and membrane bioreactors, are energy-intensive and often fail to recover valuable by-products [

28]. In contrast, algal cultivation can significantly reduce COD, BOD, nitrate, and phosphate concentrations while producing protein- and pigment-rich biomass [

4,

29]. Furthermore, photosynthetic Spirulina growth captures atmospheric CO₂, linking wastewater management with climate mitigation. Integrating such systems in institutional facilities—such as university canteens—can transform waste management into a resource recovery process that simultaneously alleviates environmental impacts and generates bioactive compounds for commercial use.

While extensive research exists on Spirulina growth in industrial or municipal effluents, the potential of canteen wastewater as a cultivation medium remains underexplored [

30,

31]. The predictable nutrient composition of CW and its availability in urban institutions present a consistent substrate for circular biotechnological applications. Moreover, the ability to achieve both nutrient remediation and carotenoid-rich biomass production in a single system has not been previously demonstrated.

Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the feasibility of using diluted canteen wastewater as a growth medium for Spirulina platensis and to compare its performance against the conventional BG-11 medium. Specifically, the work quantifies biomass productivity, nutrient removal efficiencies, and carotenoid yield under optimized light and dilution conditions. To the best of our knowledge, this represents the first integrated assessment of canteen wastewater as a dual-purpose substrate for Spirulina-based wastewater treatment and carotenoid enrichment, offering a scalable and sustainable model for institutional circular bioeconomy applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wastewater Collection and Pre-Treatment

Canteen wastewater was collected from the dining facility of the University of Moratuwa in sterile polyethylene containers, transported on ice, and processed within 24 h. Suspended solids were removed by filtration through a 0.45 µm nylon mesh (Millipore), and the clarified wastewater was used as the experimental medium. Preliminary screening experiments were conducted to determine optimal dilution and illumination conditions for Spirulina sp. cultivation. Based on these results, a 75% (v/v) dilution of wastewater with sterile distilled water was selected, with pH adjusted to 9.1 using 1 M NaOH (Sigma-Aldrich). The initial chemical oxygen demand (COD) of the diluted wastewater was 342.4 mg L⁻¹. BG11 medium (HiMedia, India) served as the control. Both media were sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 48 min.

2.2. Wastewater Characterization

Initial characterization of raw canteen wastewater was performed according to APHA Standard Methods (2017). All measurements were conducted in triplicate (n = 3). The following parameters were determined:

pH – using a benchtop pH meter (Mettler Toledo SevenCompact).

COD – open reflux titrimetric method with potassium dichromate digestion.

Nitrate (NO₃⁻–N) – UV absorbance at 220 nm with baseline correction at 275 nm.

Phosphate (PO₄³⁻–P) – molybdenum blue method, absorbance at 880 nm.

The characterized wastewater parameters were compared against national discharge standards (Central Environmental Authority, Sri Lanka, 2022). COD levels (420–480 mg L⁻¹) exceeded the permissible discharge limit of 250 mg L⁻¹, while nitrate (8–12 mg L⁻¹) and phosphate (5–7 mg L⁻¹) concentrations also surpassed thresholds for secondary-treated effluent (NO₃⁻ ≤ 5 mg L⁻¹; PO₄³⁻ ≤ 2 mg L⁻¹). These findings confirmed the necessity of nutrient remediation prior to discharge.

2.3. Microalgal Strain and Inoculum Preparation

A pure culture of Spirulina sp. was obtained from Progreen Laboratory, University of Moratuwa. Pre-cultures were grown in Zarrouk’s medium under controlled conditions (25 ± 2 °C, continuous illumination at 150 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ with cool-white LED lights, and aeration at 0.5 vvm sterile-filtered air) before being transferred to experimental flasks. Stationary-phase cultures were harvested, centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min, and inoculated into experimental media at an initial biomass concentration of 0.3 g L⁻¹ (dry weight).

2.4. Experimental Setup and Cultivation Conditions

2.4.1. Screening of Wastewater Dilution Factors

Four dilutions of canteen wastewater (25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% v/v) were prepared using distilled water, with 400 mL working volume in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. Initial pH (<9) was adjusted to 8.7 using NaOH. BG11 medium (400 mL) served as the control. Cultures were incubated at 32 °C under a 12:12 h light–dark cycle, aerated continuously, and illuminated at 100 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ (LED, cool-white). Biomass growth was monitored every 48 h by optical density (OD₆₀₀) and dry weight measurement. The 75% wastewater dilution supported the highest biomass accumulation and was selected for subsequent experiments.

2.4.2. Screening of Light Intensities

The effect of light intensity on biomass production was evaluated using the optimal 75% wastewater medium. Four light intensities (60, 120, 180, and 240 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹, LED, cool-white) were tested, with BG11 at 100 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ as the control. Cultures were incubated under the same conditions as Section 3.4.1. Biomass accumulation was monitored every 48 h. The results indicated that 180 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ supported the highest growth, which was selected for the main experiment.

2.4.3. Main Cultivation Experiment

The main batch cultivation was carried out in 2 L sterilized glass vessels with 1.5 L working volume, using either the selected 75% wastewater medium or BG11 control. Cultures were incubated at 32 °C under a 12:12 h light–dark photoperiod, aerated with sterile-filtered air pumps (Hailea ACO-9602, 0.22 µm filter), and illuminated with LED lights at 180 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹. Light intensity was monitored with a quantum sensor (LI-COR LI-250A).

2.5. Analytical Procedures

2.5.1. Biomass Concentration

Biomass growth was monitored every 48 h. Optical density (OD₆₀₀) was measured with a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800). For dry weight determination, 50 mL aliquots were filtered through pre-weighed glass fiber filters (Whatman GF/C, 0.2 µm), dried at 105 °C to constant weight, and expressed as g L⁻¹. Biomass productivity was calculated as:

where X

f and X

i are the final and initial biomass concentrations (g L⁻¹), and t is the cultivation period (days).

2.5.2. Nutrient and COD Removal

Water quality was analyzed before inoculation and throughout cultivation (n = 3). pH was measured using a multiparameter probe (Hanna HI98194). COD was determined by the open reflux titrimetric method [

33]. Nitrate and phosphate concentrations were determined as in

Section 2.2.

Nutrient removal efficiency (RE, %) was calculated as:

where (C

i) and (C

f) are initial and final concentrations (mg L⁻¹), respectively. COD removal efficiency was calculated similarly.

2.5.3. Analytical Validation

All analyses were performed in triplicate. UV–Vis measurements were calibrated with standard solutions (potassium nitrate, KH₂PO₄, and potassium hydrogen phthalate). Calibration curves showed excellent linearity (R² ≥ 0.996). Instrumental blanks were run for each batch to eliminate baseline drift.

2.6. Biomass Harvesting and Carotenoid Extraction

At the end of the 20-day cultivation period, biomass was harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 10 min (Eppendorf 5810R), washed twice with sterile distilled water, and oven-dried at 60 °C to constant weight [

34,

35]. For carotenoid extraction, 100 mg dried biomass was homogenized with 10 mL of analytical grade 95% ethanol (Merck), incubated in the dark at room temperature for 1 h, and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min. Absorbance of the supernatant was measured at 470 nm (Shimadzu UV-1800), and total carotenoid content was calculated using the extinction coefficient (E¹%₁cm = 2500 in ethanol) [

36]. Carotenoid yield was expressed as mg g⁻¹ dry weight.

where A is absorbance at 470 nm, E is extinction coefficient, d is path length (1 cm), and DW is dry biomass weight (g).

2.7. Biochemical Composition

2.7.1. Protein Content

Protein content was determined by the micro-Kjeldahl method [

37]. Dried biomass (0.1 g) was digested with concentrated H₂SO₄ and catalyst (K₂SO₄:CuSO₄, 10:1), distilled using a Kjeltec™ 8400 Analyzer (Foss), and titrated with standardized 0.1 N HCl. Total nitrogen was converted to protein using a factor of 6.25.

2.7.2. Carbohydrate Content

Total carbohydrates were determined using the phenol–sulfuric acid method [

38]. Dried biomass (0.1 g) was hydrolyzed in boiling water, centrifuged at 5000 rpm, and the supernatant reacted with phenol and concentrated H₂SO₄. Absorbance was recorded at 490 nm, and carbohydrate content (%) was calculated against a glucose calibration curve (10–100 mg L⁻¹).

2.7.3. Lipid Content

Lipids were quantified using the Bligh and Dyer method [

39]. Dried biomass (0.5 g) was homogenized in chloroform:methanol (2:1, v/v), phase-separated with saline solution, and the organic phase evaporated to dryness. Lipid content was gravimetrically determined and expressed as % dry weight.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3). Results are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA (Minitab 22, 2022 edition), with Tukey’s post hoc test for pairwise comparisons at p < 0.05. Normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test) were verified prior to analysis. Confidence intervals were reported at 95%.

3. Results

The growth performance of Spirulina sp. was evaluated under different wastewater dilutions, light intensities, and optimized culture conditions. Key parameters included optical density (OD₆₀₀), dry biomass concentration, pH variation, nutrient removal efficiency, biomass productivity, carotenoid yield, and biochemical composition.

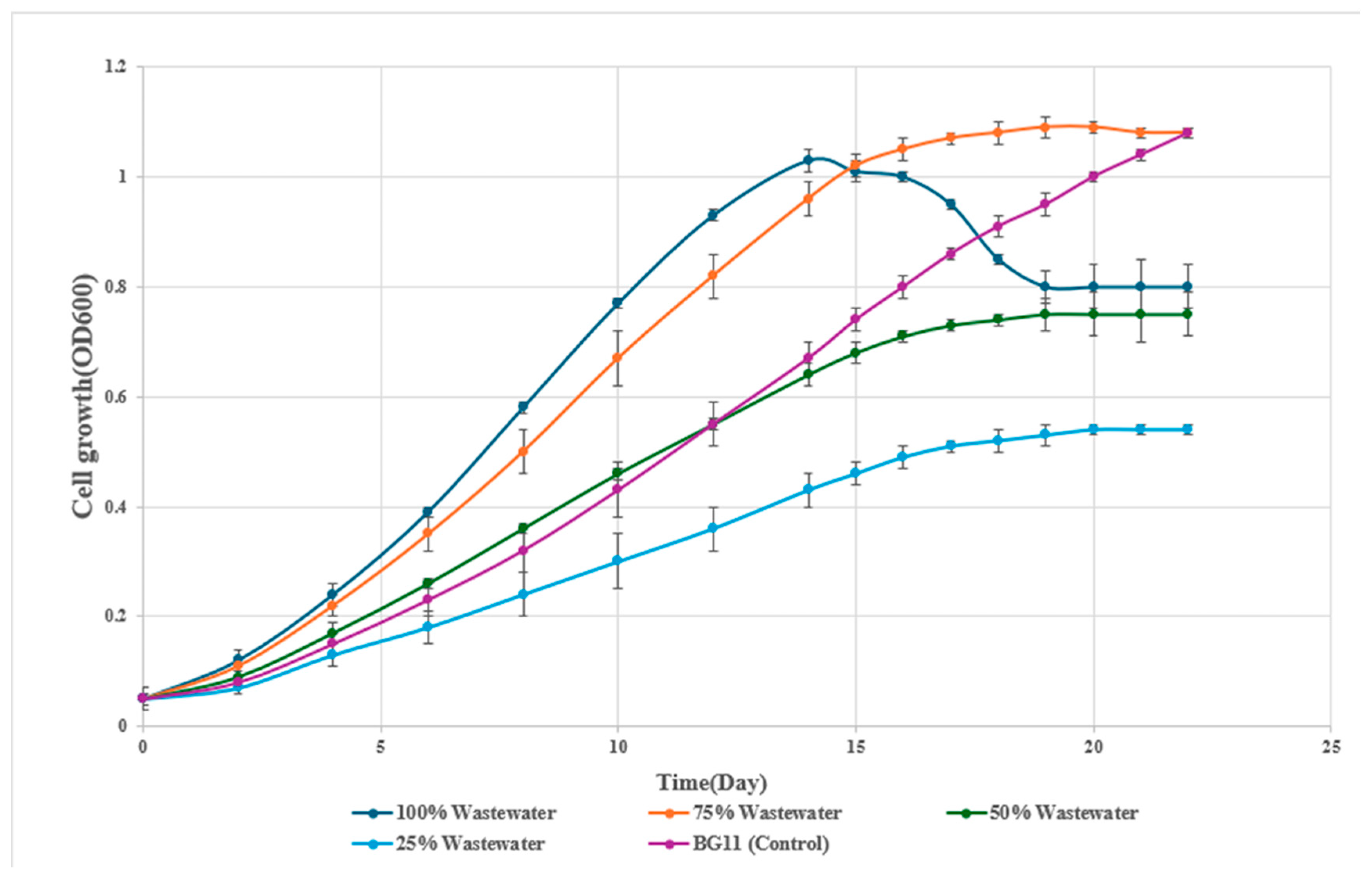

The OD₆₀₀ profiles demonstrated a typical sigmoidal growth pattern across wastewater dilutions (

Figure 1). The 75% wastewater dilution exhibited the most sustained growth, achieving an OD₆₀₀ of 1.09 by day 19 and maintaining it through day 22. The 100% wastewater condition peaked at 1.03 on day 14 but declined to 0.80 by day 22, while the BG11 control steadily increased to 1.08.

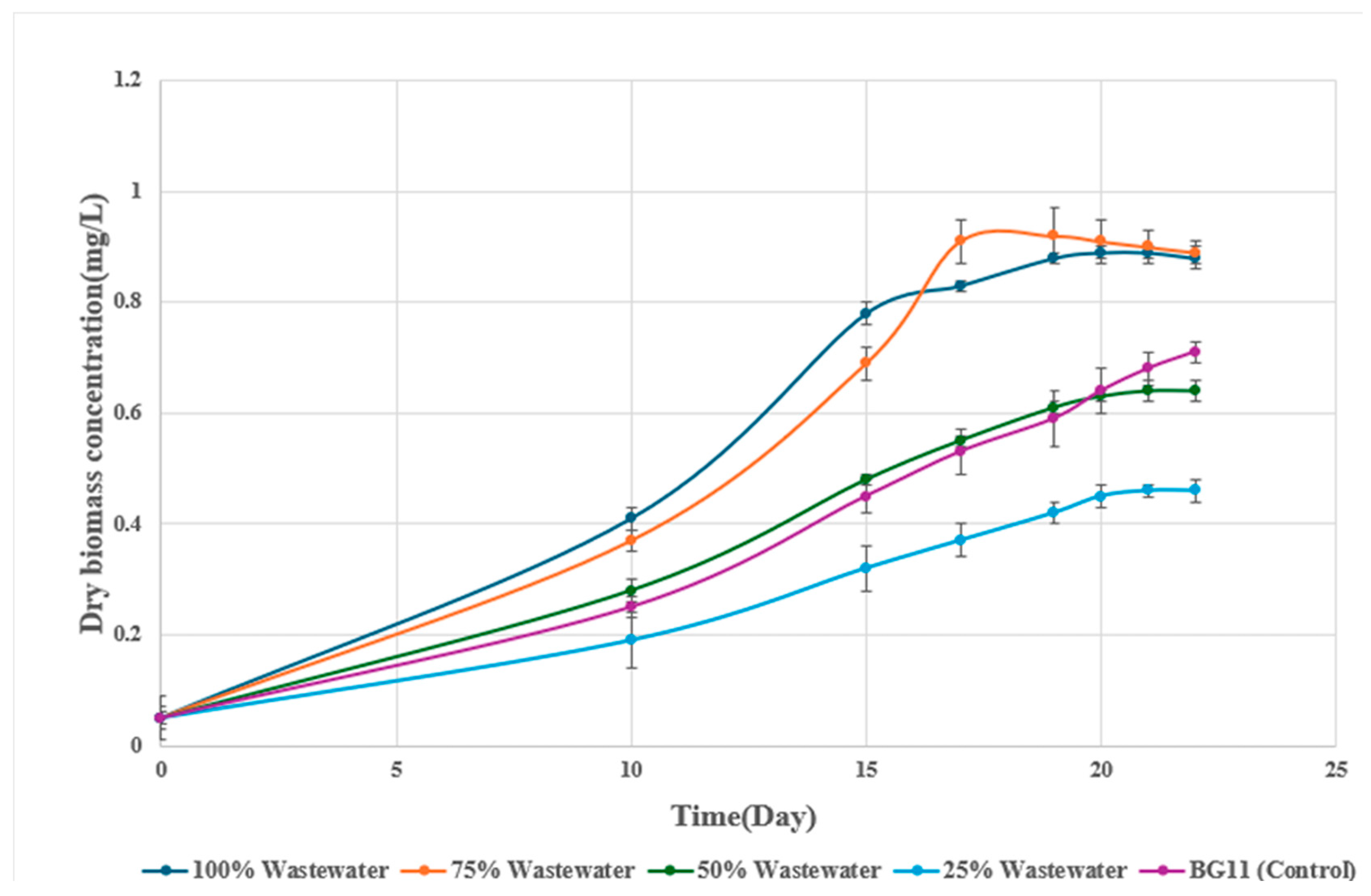

Dry biomass concentrations supported these findings (

Figure 2). The 75% wastewater culture reached a maximum of 0.92 g/L by day 19, significantly higher than the BG11 control (0.71 g/L, p < 0.05). The 100% wastewater treatment reached 0.88 g/L before declining, while the 25% and 50% dilutions supported only 0.46 and 0.64 g/L, respectively. Visual assessments further confirmed these results, with cultures in 75% wastewater showing a deep green color during exponential growth, while 25% and 50% dilutions remained pale and 100% wastewater cultures became dull green after day 17.

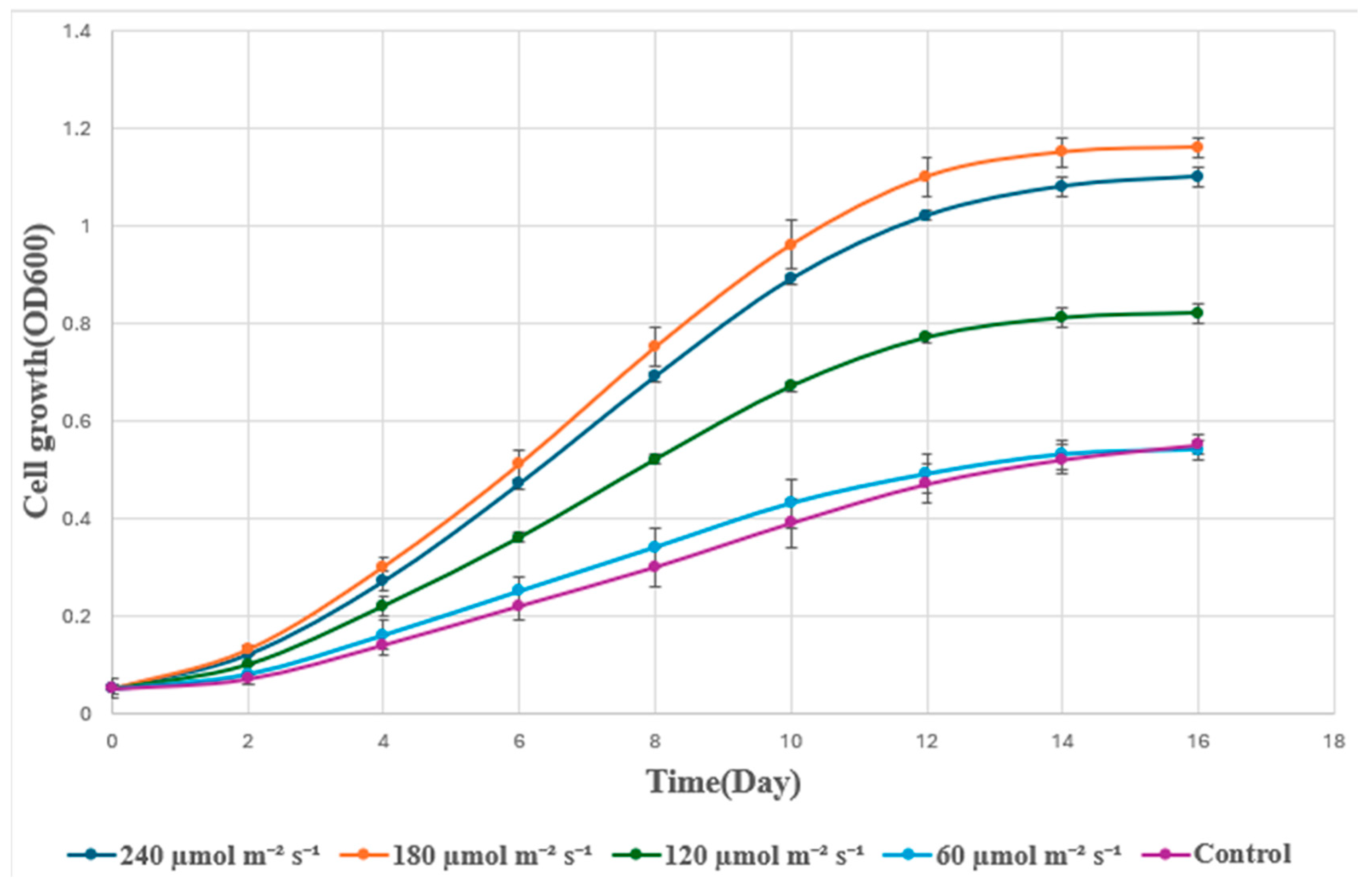

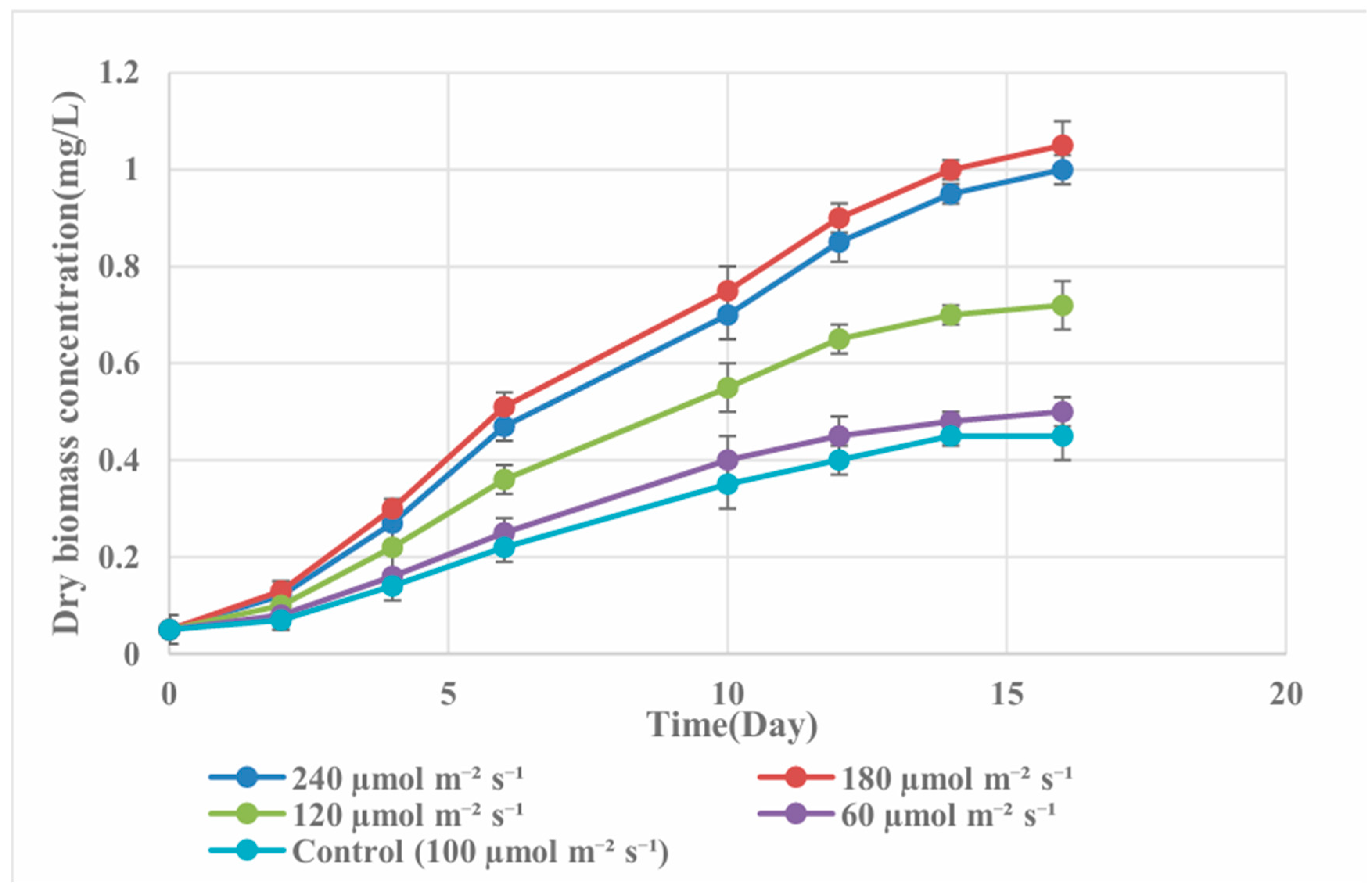

Light intensity exerted a strong influence on Spirulina growth in 75% wastewater (

Figure 3). Cultures grown under 180 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ attained the highest OD₆₀₀ (1.16 by day 16), followed closely by 240 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ (1.10). Lower light intensities (60 and 100 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹) produced significantly lower OD₆₀₀ values (0.54 and 0.55, respectively). Biomass measurements confirmed this trend (

Figure 4), with 180 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ achieving 1.05 g/L by day 16, which was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than other treatments.

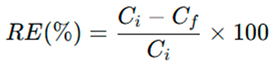

In the main experiment conducted under optimized conditions (75% wastewater and 180 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹), Spirulina achieved markedly higher growth compared with BG11 (Table 5). OD₆₀₀ increased from 0.05 ± 0.00 at inoculation to a peak of 1.88 ± 0.01 on day 18, stabilizing at 1.85 ± 0.01 on day 20. The BG11 control reached only 0.60 ± 0.01 by day 20, with significant differences between treatments at all time points (p < 0.05). Dry biomass concentrations followed a similar trend (

Figure 5; Table 1), reaching 1.47 ± 0.01 g/L in wastewater compared with 0.52 ± 0.01 g/L in BG11 (p < 0.05). Color differences were evident, with wastewater cultures developing a dense green pigmentation, while BG11 remained pale .

Table 1.

Optical Density (OD600) of Spirulina sp. cultivated in optimized canteen.

Table 1.

Optical Density (OD600) of Spirulina sp. cultivated in optimized canteen.

| Day |

75% Wastewater + 180 µmol |

Control BG11 |

| 0 |

0.05ᴶᵃ |

0.05ᴵᵃ |

| 2 |

0.18ᴵᵃ |

0.07ᴵᵇ |

| 4 |

0.50ᴴᵃ |

0.14ᴴᵇ |

| 6 |

0.90ᴳᵃ |

0.22ᴳᵇ |

| 8 |

1.30ᶠᵃ |

0.30ᶠᵇ |

| 10 |

1.55ᴱᵃ |

0.39ᴱᵇ |

| 12 |

1.72ᴰᵃ |

0.47ᴰᵇ |

| 14 |

1.80ᶜᵃ |

0.52ᶜᵇ |

| 16 |

1.85ᴮᵃ |

0.55ᴮᵇ |

| 18 |

1.88ᴬᵃ |

0.57ᴮᵇ |

| 20 |

1.85ᴮᵃ |

0.60ᴬᵇ |

Figure 5.

Dry biomass concentration of Spirulina sp. cultivated in main.

Figure 5.

Dry biomass concentration of Spirulina sp. cultivated in main.

Table 2.

Dry biomass concentration of Spirulina sp. cultivated in optimized canteen.

Table 2.

Dry biomass concentration of Spirulina sp. cultivated in optimized canteen.

| Day |

75% Wastewater + 180 µmol (g/L) |

Control BG11 (g/L) |

| 0 |

0.05 ± 0.00ᴱᵃ |

0.05 ± 0.00ᶠᵃ |

| 8 |

0.90 ± 0.01ᴰᵃ |

0.35 ± 0.01ᴱᵇ |

| 10 |

1.20 ± 0.01ᶜᵃ |

0.40 ± 0.01ᴰᵇ |

| 16 |

1.45 ± 0.01ᴮᵃ |

0.45 ± 0.01ᶜᵇ |

| 18 |

1.48 ± 0.01ᴬᵃ |

0.48 ± 0.01ᴮᵇ |

| 20 |

1.47 ± 0.01ᴬᴮᵃ |

0.52 ± 0.01ᴬᵇ |

The pH of wastewater-grown cultures rose from 7.51± 0.03 on day 0 to 9.73 ± 0.05 by day 16, remaining stable thereafter, while the BG11 control increased only from 7.50 ± 0.02 to 8.60 ± 0.04 (

Table 3). These differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05).

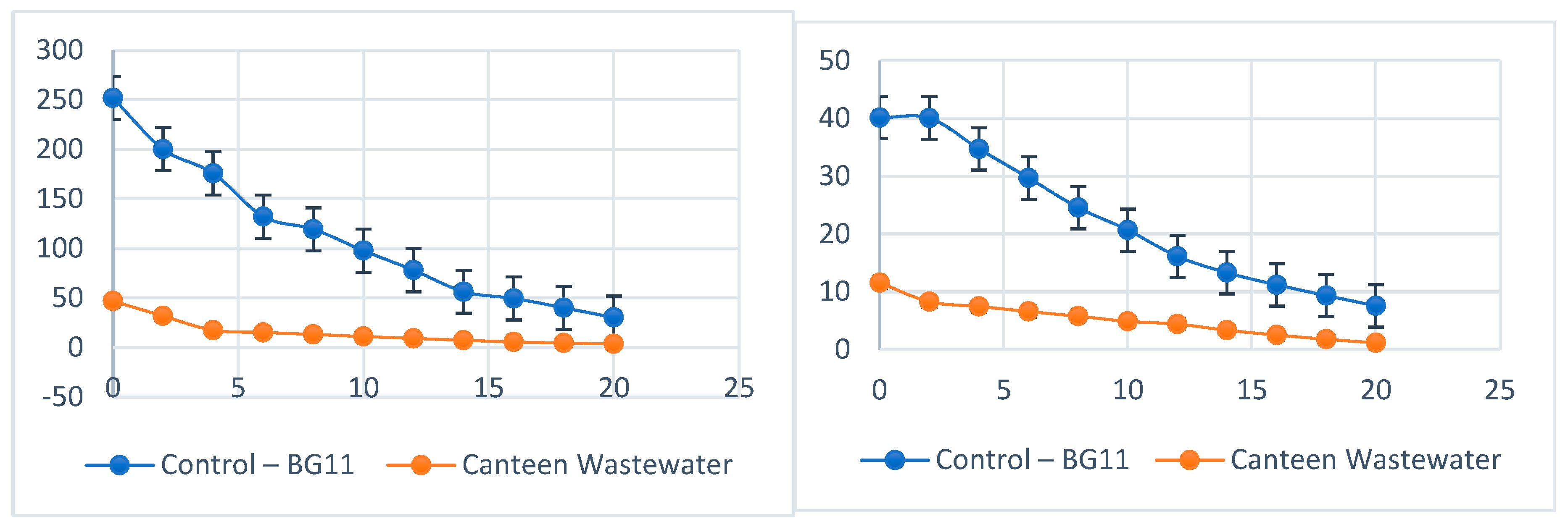

Nutrient removal efficiencies were high in wastewater cultures (

Figures 6;

Table 4). Phosphate decreased from 11.56 mg/L to 1.15 mg/L, corresponding to a removal efficiency of 90.05%, while nitrate declined from 46.87 mg/L to 3.7 mg/L (92.12% removal). In contrast, the BG11 control achieved 81.16% phosphate and 87.93% nitrate removal, with statistically significant differences observed (p < 0.05).

Biomass productivity in wastewater cultures was 0.071 g/L/day, nearly three times higher than BG11 at 0.023 g/L/day. Carotenoid yield under optimized conditions was 2.4 mg/L, equivalent to 21.81 mg/g DW. Biochemical composition analysis revealed a protein content of 54.3% and carbohydrate content of 13.8% in wastewater-grown Spirulina biomass (Section 3.7).

Collectively, these statistically validated results confirm that 75% canteen wastewater, under 180 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ light, supports significantly superior Spirulina growth, nutrient removal, biomass productivity, and biochemical quality compared with the BG11 synthetic medium.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates the feasibility of using diluted canteen wastewater (CW) as a nutrient-rich growth medium for Spirulina platensis, achieving enhanced biomass productivity, effective nutrient remediation, and enriched carotenoid accumulation. Optimization of wastewater dilution (75%) and light intensity (180 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹) produced results superior to those obtained in the standard BG-11 synthetic medium, confirming the dual potential of CW for sustainable wastewater treatment and bioproduct generation.

The screening experiments revealed that the degree of wastewater dilution critically influenced algal growth dynamics. Although undiluted (100%) CW initially supported rapid biomass accumulation, growth declined after day 14, reflecting nutrient and organic overload. This inhibition is attributable to excessive concentrations of free ammonia nitrogen, which is recognized as one of the main limiting factors in

Spirulina cultivation. Previous threshold studies have established that concentrations above 1.6 mM (0.027 g L⁻¹) impair growth and that levels above 2 mM (0.034 g L⁻¹) are toxic [

40]. Similarly, total ammonia nitrogen above 217–246 mg L⁻¹ induces cell death [

41]. These thresholds correspond well with the observed growth inhibition in the 100% CW treatment, where nutrient loads likely exceeded tolerance limits.

High organic loading (COD > 400 mg L⁻¹) also contributes to growth suppression by reducing light penetration and creating oxidative stress conditions unfavorable to photosynthesis [

42]. The decline in pigmentation and biomass after day 17 in undiluted CW further supports this effect. Conversely, the 75% CW dilution provided balanced nutrient availability while maintaining non-inhibitory levels of ammonia and organic matter. Maintaining ammonium below 50% of total nitrogen is reported to sustain stable

Spirulina growth [

43,

44,

45,

46]; this condition was met in the optimized treatment. Consequently, cultures in 75% CW achieved the highest OD₆₀₀ (1.09) and dry biomass (0.92 g L⁻¹), confirming that moderate dilution ensures sufficient nutrient supply while preventing toxicity.

Light intensity was another decisive parameter governing biomass yield and metabolite formation. The maximum growth obtained at 180 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ corresponds to the reported optimal range (150–200 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹) for photosynthetic efficiency in

Spirulina [

47]. At this irradiance, photosynthetic energy supply and metabolic demand were optimally balanced, maximizing chlorophyll and phycocyanin synthesis without inducing photoinhibition. The slightly reduced productivity at 240 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ indicates the onset of oxidative stress, corroborated by elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation under high light exposure [

48]. Under such conditions,

Spirulina activates antioxidant enzymes—superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidase—yet overall photosynthetic efficiency declines.

In contrast, cultures maintained at lower irradiances (60–100 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹) exhibited light limitation, where photon flux was insufficient to support optimal metabolic activity despite the organic carbon contribution of CW. These observations confirm that balanced irradiance is critical for achieving high biomass and pigment productivity in nutrient-rich media. The optimized 180 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ condition thus provides the best trade-off between light energy utilization and oxidative stress control.

Under optimized CW conditions,

Spirulina achieved nearly threefold higher biomass productivity (0.071 g L⁻¹ day⁻¹) than in BG-11 (0.023 g L⁻¹ day⁻¹). This value is comparable to or exceeds yields reported for various food-industry and agro-industrial wastewaters (0.06–0.08 g L⁻¹ day⁻¹) [

43,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. Table 1 summarizes productivity ranges from different wastewater-based

Spirulina systems and highlights the performance achieved in the present study.

Table 1.

Comparison of biomass productivity in Spirulina cultivation using different wastewater sources.

Table 1.

Comparison of biomass productivity in Spirulina cultivation using different wastewater sources.

| Scale / System Type |

Maximum Productivity (g L⁻¹ day⁻¹) |

System Volume / Area |

Key Performance Metrics |

Production Conditions |

Species / Strain |

Reference |

| Commercial raceway pond (605 m², strain 208) |

0.31 (18.7 g m⁻² day⁻¹) |

605 m² (industrial) |

18.7 g m⁻² day⁻¹ DW |

Semi-continuous, outdoor |

Spirulina 208 |

[54] |

| Commercial raceway pond (605 m², strain 220) |

0.22 (13.2 g m⁻² day⁻¹) |

605 m² (industrial) |

13.2 g m⁻² day⁻¹ DW |

Semi-continuous, outdoor |

Spirulina 220 |

[54] |

| Indoor raceway pond (4 m²) |

0.045 (44.75 mg L⁻¹ day⁻¹) |

4 m² |

Highest in strain 220 |

Controlled indoor, pH 9.5 |

Spirulina 220 |

[54] |

| Indoor raceway pond (4 m²) |

0.029 (29.20 mg L⁻¹ day⁻¹) |

4 m² |

pH 9.5 optimal |

Controlled indoor |

Spirulina 208 |

[56] |

| Pilot-scale cultivation (162 L) |

0.12 (0.84 g L⁻¹ biomass) |

162 L |

μ = 0.53 d⁻¹ (first 3 days) |

Seawater medium |

S. subsalsa |

[57] |

| Large-scale cultivation (10 L) |

0.21 (2.43 g L⁻¹ in 10 days) |

10 L |

2.43 g L⁻¹ biomass |

Batch, 10 days |

Spirulina sp. |

[58] |

| Lab-scale cultivation (1 L) |

0.23 (2.89 g L⁻¹ in 10 days) |

1 L |

2.89 g L⁻¹ biomass |

Batch, optimal |

Spirulina sp. |

[58] |

| Outdoor pilot (aquaculture WW) |

0.15–0.25 |

Pilot scale |

Weather-dependent |

Outdoor, variable |

Spirulina LEB 18 |

[59] |

| Raceway pond (1400 L) |

0.05 |

1400 L |

Modified Zarrouk |

Standard operation |

A. platensis |

[60] |

| Present study (canteen WW, 75% dilution) |

0.071 |

2 L (lab scale) |

Threefold higher than BG-11 |

180 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ light |

Spirulina sp. |

– |

The productivity achieved in this work positions CW within the lower-to-middle range of industrially relevant substrates. Considering its moderate nutrient load compared with dairy or brewery wastewaters, the result reflects efficient nutrient uptake and favorable light–nutrient synergy. The achieved yield also approaches the median productivity reported for pilot- and industrial-scale systems (0.095–0.161 g L⁻¹ day⁻¹), underscoring the scalability of the approach.

Nutrient removal efficiencies were equally remarkable: 90.05% for phosphate and 92.12% for nitrate. These values are comparable to or exceed removal rates reported for

Spirulina grown in swine effluent (94% nitrate, 85% phosphate) [

61] and align with mixed microalgal consortia treating secondary effluents (70–90% nitrate removal) [

44]. Such high efficiencies confirm that

Spirulina can effectively scavenge nutrients even from relatively dilute substrates such as CW, which typically exhibit a C:N:P ratio around 100:3–4:1 [

62].

The observed performance can be mechanistically explained by

Spirulina’s adaptable nutrient uptake kinetics and stoichiometric flexibility. Phosphate assimilation occurs preferentially and more rapidly than nitrate reduction, with maximum specific uptake rates (qₘₐₓ) of up to 6.5 mg PO₄-P g TSS⁻¹ h⁻¹ [

63]. Corresponding uptake constants range from 0.4–1.0 d⁻¹ for phosphorus and 0.2–1.8 d⁻¹ for nitrogen, consistent with the slightly higher phosphate removal observed in this study. Optimal pH (≈9.0) and short adaptation times further enhance uptake efficiency, enabling

Spirulina to maintain a relatively stable intracellular N:P ratio (10–16:1) even under variable external concentrations [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68]. These properties make the strain particularly suitable for treating effluents with unbalanced nutrient ratios.

The biochemical composition of CW-grown

Spirulina reflected nitrogen-replete conditions, with protein content of 54.3% and carbohydrate content of 13.8%. These values are consistent with reports for nutrient-rich wastewater cultures (protein 50–65%; carbohydrate 10–17%) [

68,

70], confirming efficient nitrogen assimilation. The high protein fraction indicates potential for use in functional foods, animal feed, or biofertilizer applications.

Carotenoid accumulation reached 21.81 mg g⁻¹ DW under optimized conditions—among the highest values reported for

Spirulina cultivated in waste-based media. This yield compares favorably with the typical range of 10–20 mg g⁻¹ DW [

71] and approaches the upper values achieved under optimized light and nutrient regimes [

72]. The enhanced carotenoid synthesis can be attributed to the synergistic effects of moderate irradiance and balanced N:P ratios, which maintain cellular redox homeostasis while activating pigment biosynthesis pathways [

68,

73]. Adequate nitrogen availability also supports the synthesis of pigment–protein complexes such as phycobiliproteins, crucial for light harvesting and photoprotection [

74]. Excessive light or nutrient stress may further increase carotenoid accumulation but usually compromises biomass yield, emphasizing the advantage of the balanced conditions identified in this study [

75].

From a sustainability perspective, integrating Spirulina cultivation into institutional wastewater management systems offers significant techno-economic benefits. Canteen wastewater is generated continuously and generally contains a balanced nutrient profile, reducing or eliminating the need for synthetic fertilizers. Utilizing such wastewater in photobioreactors or open raceway ponds can substantially lower medium preparation costs. Additionally, this approach contributes to carbon mitigation by enabling biomass to sequester CO₂, supporting institutional carbon neutrality targets. When combined with on-site renewable energy systems, such as biogas or solar, these phycoremediation frameworks can operate with minimal net energy input. Scaling up this strategy can therefore provide both economic and environmental co-benefits, aligning with circular bioeconomy principles and Sustainable Development Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

Collectively, these findings establish that diluted canteen wastewater can serve as an effective medium for Spirulina cultivation, achieving simultaneous wastewater remediation and high-value biomass production. The process exemplifies a circular bioeconomy approach, converting institutional food-service effluents into carotenoid-rich algal biomass while mitigating environmental pollution. With further pilot-scale validation, techno-economic evaluation, and integration of on-site CO₂ capture, this system can be scaled for institutional or municipal applications, linking wastewater management with nutraceutical and bioproduct manufacturing.

5. Conclusion

This study confirmed the feasibility of valorizing canteen wastewater (CW) as a sustainable growth medium for Spirulina platensis, demonstrating its dual potential in nutrient remediation and carotenoid-rich biomass production. The systematic optimization of dilution ratio and illumination intensity revealed that 75% CW dilution under 180 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ light intensity produced the most favorable results, achieving a biomass productivity of 0.071 g L⁻¹ day⁻¹, which was nearly three times higher than that obtained with the synthetic BG-11 medium (0.023 g L⁻¹ day⁻¹). The high nutrient content of CW provided an excellent substrate for algal growth, while moderate dilution effectively reduced the inhibitory effects of free ammonia and chemical oxygen demand (COD).

Nutrient removal efficiencies were notably high, with 92.12% nitrate and 90.05% phosphate reduction observed at the optimized conditions. These results confirm the strong phycoremediation capability of Spirulina and support the concept of integrating microalgal systems into institutional wastewater management frameworks. The study further demonstrated that Spirulina effectively utilizes both inorganic and organic nutrient fractions, maintaining stable growth while converting wastewater pollutants into valuable biochemical compounds.

Biochemical analyses revealed that the CW-grown biomass was enriched with 54.3% protein, 13.8% carbohydrates, and a remarkable carotenoid yield of 21.81 mg g⁻¹ DW—among the highest reported for Spirulina cultivated in real wastewater media. These findings highlight that CW not only supports rapid growth but also induces favorable stress responses that promote carotenoid biosynthesis without significant metabolic inhibition. The balanced N:P ratio and controlled oxidative stress likely triggered the activation of key enzymes in the carotenoid synthesis pathway, resulting in enhanced pigment accumulation.

The results collectively position canteen wastewater as a low-cost, nutrient-balanced, and sustainable substrate for large-scale Spirulina cultivation. The integration of such systems into university or industrial canteens provides a viable model for circular bioeconomy applications, where nutrient-rich effluents are transformed into marketable bioproducts while ensuring environmental protection. Unlike conventional wastewater treatment technologies, this approach combines pollution mitigation with value generation, aligning directly with the objectives of SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

Moving forward, scaling up this system to pilot and semi-commercial levels will be critical for assessing operational stability, hydraulic retention optimization, and energy efficiency. Further investigation into carotenoid extraction and purification techniques, life-cycle environmental assessment, and economic feasibility analysis will provide the foundation for industrial adoption. Future studies may also explore the integration of CO₂ capture and renewable energy inputs to further enhance process sustainability.

Overall, this study presents the first integrated experimental validation of canteen wastewater valorization through Spirulina platensis cultivation, demonstrating that environmental remediation and high-value bioproduct generation can coexist within a single biotechnological framework. The findings open a promising pathway for transforming institutional waste streams into renewable biological resources, contributing meaningfully to the advancement of sustainable algal biotechnology and resource recovery systems.

References

- Zhai, J.; et al. Optimization of biomass production and nutrients removal by Spirulina platensis from municipal wastewater. Ecological Engineering 2017, 108, 83–92. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. United Nations World Water Development Report 2020: Water and Climate Change; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, 2020.

- Zhou, W.; et al. Nutrients removal and recovery from saline wastewater by Spirulina platensis. Bioresource Technology 2017, 245, 10–17. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; et al. Coupling nutrient removal and biodiesel production by cultivation of Chlorella sp. in cafeteria wastewater: Assessment of the effect of wastewater disinfection. Desalination and Water Treatment 2023, 291, 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Ragaza, J.A.; et al. A review on Spirulina: Alternative media for cultivation and nutritive value as an aquafeed. Reviews in Aquaculture 2020, 12, 2371–2395. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Integration of Waste Valorization for Sustainable Production of Chemicals and Materials via Algal Cultivation. Topics in Current Chemistry 2017, 375, 89. [CrossRef]

- Ruslinda, Y.; et al. Characterization of Wastewater in The University Campus: A Case Study in Universitas Andalas, Indonesia. Dampak 2025, 21, 18–26. [CrossRef]

- Gude, V.G. Desalination and water reuse to address global water scarcity. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 2017, 16, 591–609. [CrossRef]

- Dada, E.O.; Agu, C.M.; Akinola, M.O. Physicochemical Quality and Genotoxic Potential of Wastewater Generated by Canteen Complex. ARO-The Scientific Journal of Koya University 2019, 7, 19. [CrossRef]

- Mohadi, R.; et al. The effect of metal ion Cd(II) concentration on the growth of Spirulina sp. cultured on BG-11 medium. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2020, 530, 012036. [CrossRef]

- Lukavský, J. Vonshak, A. (Ed.): Spirulina platensis (Arthrospira). Physiology, Cell Biology and Biotechnology. Photosynthetica 2000, 38, 552. [CrossRef]

- Olguín, E.J. Dual purpose microalgae–bacteria-based systems that treat wastewater and produce biodiesel and chemical products within a biorefinery. Biotechnology Advances 2012, 30, 1031–1046. [CrossRef]

- Lizzul, A.M.; et al. Expanding the economic viability of microalgae-based biofuels through wastewater cultivation and nutrient trading. Bioresource Technology 2014, 172, 269–274. [CrossRef]

- Pittman, J.K.; Dean, A.P.; Osundeko, O. The potential of sustainable algal biofuel production using wastewater resources. Bioresource Technology 2011, 102, 17–25. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, I.; et al. Dual role of microalgae: Phycoremediation of domestic wastewater and biomass production for sustainable biofuels production. Applied Energy 2011, 88, 3411–3424. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; et al. Cultivation of Spirulina platensis using raw piggery wastewater for nutrients bioremediation and biomass production: effect of ferrous sulfate supplementation. Desalination and Water Treatment 2020, 175, 60–67. [CrossRef]

- Christenson, L.; Sims, R. Production and harvesting of microalgae for wastewater treatment, biofuels, and bioproducts. Biotechnology Advances 2011, 29, 686–702. [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, L.; Oliveira, A.C. Microalgae as a raw material for biofuels production. Journal of Industrial Microbiology & Biotechnology 2009, 36, 269–274. [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, H.S.; Hashem, M.M. Microalgae as a source of carotenoids in foods, obstacles and solutions. Phytochemistry Reviews [Preprint] 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P. Microalgae as Nutraceutical for Achieving Sustainable Food Solution in Future. In Microbial Biotechnology: Basic Research and Applications; Singh, J., et al., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 91–125. [CrossRef]

- Medipally, S.R.; et al. Microalgae as Sustainable Renewable Energy Feedstock for Biofuel Production. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Marzorati, S.; et al. Carotenoids, chlorophylls and phycocyanin from Spirulina: supercritical CO2 and water extraction methods for added value products cascade. Green Chemistry 2020, 22, 187–196. [CrossRef]

- Wils, L.; et al. Alternative Solvents for the Biorefinery of Spirulina: Impact of Pretreatment on Free Fatty Acids with High Added Value. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 600. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.I.B.; et al. Mixotrophic cultivation of Spirulina platensis in dairy wastewater: Effects on the production of biomass, biochemical composition and antioxidant capacity. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0224294. [CrossRef]

- Motto, S.A.; Christwardana, M.; Hadiyanto. Potency of Yeast–Microalgae Spirulina Collaboration in Microalgae-Microbial Fuel Cells for Cafeteria Wastewater Treatment. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2018, 209, 012022. [CrossRef]

- Christwardana, M.; et al. Performance evaluation of yeast-assisted microalgal microbial fuel cells on bioremediation of cafeteria wastewater for electricity generation and microalgae biomass production. Biomass and Bioenergy 2020, 139, 105617. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; et al. Coupling nutrient removal and biodiesel production by cultivation of Chlorella sp. in cafeteria wastewater: Assessment of the effect of wastewater disinfection. Desalination and Water Treatment 2023, 291, 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Lodi, A.; et al. Nitrate and phosphate removal by Spirulina platensis. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2003, 30, 656–660. [CrossRef]

- Qadir, M.; et al. Global and regional potential of wastewater as a water, nutrient and energy source. Natural Resources Forum 2020, 44, 40–51. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, L.G.; et al. Spirulina sp. LEB 18 cultivation in outdoor pilot scale using aquaculture wastewater: High biomass, carotenoid, lipid and carbohydrate production. Aquaculture 2020, 525, 735272. [CrossRef]

- Saini, J.K.; et al. Integrated Lignocellulosic Biorefinery for Sustainable Bio-Based Economy. In Sustainable Approaches for Biofuels Production Technologies; Srivastava, N., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2019; pp. 25–46. [CrossRef]

- Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D.; Federation, W.E. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, 2017.

- Indrani, Mafasia; Gunawardana, Sriyani; Gunarathne. The Role of Central Environmental Authority in Managing Solid Waste in Sri Lanka. Journal of Accountancy & Finance 2024, 11, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A. Handbook of Microalgal Culture: Biotechnology and Applied Phycology; Blackwell Science Ltd.: Oxford, 2004.

- Vonshak, A.; Torzillo, G.; Tomaselli, L. Arthrospira (Spirulina). In The Ecology of Cyanobacteria; Whitton, B.A.; Potts, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, 2000; pp. 505–522. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: New York, 1987; Vol. 148, pp. 350–382.

- Michałowski, T.; Navas, M.J.; Asuero, A.G.; Wybraniec, S. An Overview of the Kjeldahl Method of Nitrogen Determination. Part I. Early History, Chemistry of the Procedure, and Titrimetric Finish. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2013, 43, 1–23.

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Roberts, P.A.; Smith, F. Phenol sulphuric acid method for carbohydrate determination. Ann. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–359.

- Pérez-Palacios, T.; Ruiz, J.; Martín, D.; Muriel, E.; Antequera, T. Comparison of different methods for total lipid quantification in meat and meat products. Food Chemistry 2008, 110, 1025–1029.

- Balseca, D.A.; Castro Reyes, K.S.; Maldonado Rodríguez, M.E. Optimization of an Alternative Culture Medium for Phycocyanin Production from Arthrospira platensis under Laboratory Conditions. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 63. [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A.; Hu, Q. Handbook of Microalgal Culture: Applied Phycology and Biotechnology, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2013.

- Spolaore, P.; Joannis-Cassan, C.; Duran, E.; Isambert, A. Commercial applications of microalgae. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2006, 101, 87–96. [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.W. Microalgae: Biotechnology and Microbiology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994.

- Richmond, A. Microalgal Biotechnology at the Turn of the Millennium: Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Microalgal Biotechnology; Elsevier Science B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003.

- Vonshak, A. Spirulina Platensis (Arthrospira): Physiology, Cell Biology and Biotechnology; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1997.

- Pulz, O.; Gross, W. Valuable products from biotechnology of microalgae. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2004, 65, 635–648. [CrossRef]

- Borowitzka, M.A. High-value products from microalgae—their development and commercialisation. Journal of Applied Phycology 2013, 25, 743–756. [CrossRef]

- Wijffels, R.H.; Barbosa, M.J. An outlook on microalgal biofuels. Science 2010, 329, 796–799. [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.W.; et al. Microalgae biorefinery: High-value products perspectives. Bioresource Technology 2017, 229, 53–62. [CrossRef]

- Norsker, N.H.; Barbosa, M.J.; Vermuë, M.H.; Wijffels, R.H. Microalgal production—a close look at the economics. Biotechnology Advances 2011, 29, 24–27. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; et al. A review on microalgae based biofuels and bioproducts: Sustainable source for energy and food security. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 62, 213–235. [CrossRef]

- Mata, T.M.; Martins, A.A.; Caetano, N.S. Microalgae for biodiesel production and other applications: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2010, 14, 217–232. [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.; Owende, P. Biofuels from microalgae—a review of technologies for production, processing, and extractions of biofuels and co-products. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2010, 14, 557–577. [CrossRef]

- Chisti, Y. Biodiesel from microalgae. Biotechnology Advances 2007, 25, 294–306. [CrossRef]

- Spolaore, P.; Joannis-Cassan, C.; Duran, E.; Isambert, A. Commercial applications of microalgae. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering 2006, 101, 87–96. [CrossRef]

- Huesemann, M.H.; et al. Large-scale algal cultivation for biofuels: Environmental and economic considerations. Biofuels 2014, 5, 23–38. [CrossRef]

- Markou, G.; Nerantzis, E. Microalgae for high-value compounds and biofuels production. In Handbook of Marine Microalgae: Biotechnology Advances; Elsevier: London, UK, 2013; pp. 185–207. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Nigam, P.S.; Murphy, J.D. Renewable fuels from algae: An answer to debatable land based fuels. Bioresource Technology 2011, 102, 10–16. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; et al. Microalgae for biofuels and bioproducts: A review. Biotechnology for Biofuels 2013, 6, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Borowitzka, M.A. Commercial production of microalgae: Ponds, tanks, and photobioreactors. Journal of Biotechnology 1999, 70, 313–321. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Singh, P. Effect of temperature and light on the growth of algae species: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 50, 431–444. [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.; Owende, P. Biofuels from microalgae—a review of technologies for production, processing, and extractions of biofuels and co-products. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2010, 14, 557–577. [CrossRef]

- Wijffels, R.H.; Barbosa, M.J. Microalgae for the production of bulk chemicals and biofuels. Trends in Biotechnology 2010, 28, 208–212. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, I.; Ranjith Kumar, R.; Mutanda, T.; Bux, F. Dual role of microalgae: Phycoremediation of domestic wastewater and biomass production for sustainable biofuels production. Applied Energy 2011, 88, 3411–3424. [CrossRef]

- Molina Grima, E.; Belarbi, E.H.; Acién Fernández, F.G.; Robles Medina, A.; Chisti, Y. Recovery of microalgal biomass and metabolites: Process options and economics. Biotechnology Advances 2003, 20, 491–515. [CrossRef]

- Safi, C.; et al. Microalgae and cyanobacteria: Biofuel production and prospects. Journal of Environmental Management 2014, 145, 152–160. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; et al. Microalgae-based biofuels: Challenges and opportunities. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 58, 79–93. [CrossRef]

- Chisti, Y. Constraints to commercialization of algal fuels. Journal of Biotechnology 2013, 167, 201–214. [CrossRef]

- Markou, G.; Nerantzis, E. Microalgae for high-value compounds and biofuels production. In Handbook of Marine Microalgae: Biotechnology Advances; Elsevier: London, UK, 2013; pp. 185–207. [CrossRef]

- Brennan, L.; Owende, P. Biofuels from microalgae—a review of technologies for production, processing, and extractions of biofuels and co-products. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2010, 14, 557–577. [CrossRef]

- Borowitzka, M.A.; Moheimani, N.R. Sustainable biofuels from algae. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2013, 18, 13–25. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, I.; Ranjith Kumar, R.; Mutanda, T.; Bux, F. Dual role of microalgae: Phycoremediation of domestic wastewater and biomass production for sustainable biofuels production. Applied Energy 2011, 88, 3411–3424. [CrossRef]

- Christwardana, M.; Motto, S.A.; Hadiyanto. Treatment of cafeteria wastewater with microalgae: Biomass production and nutrient recovery. Environmental Technology 2018, 39, 1186–1196. [CrossRef]

- Parry, A.; et al. Potential of wastewater-fed microalgae for nutrient recovery and biomass production. Bioresource Technology 2024, 382, 130602. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Yeh, K.L.; Aisyah, R.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, J.S. Cultivation, photobioreactor design and harvesting of microalgae for biodiesel production: A critical review. Bioresource Technology 2011, 102, 71–81. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).