Submitted:

10 November 2025

Posted:

11 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

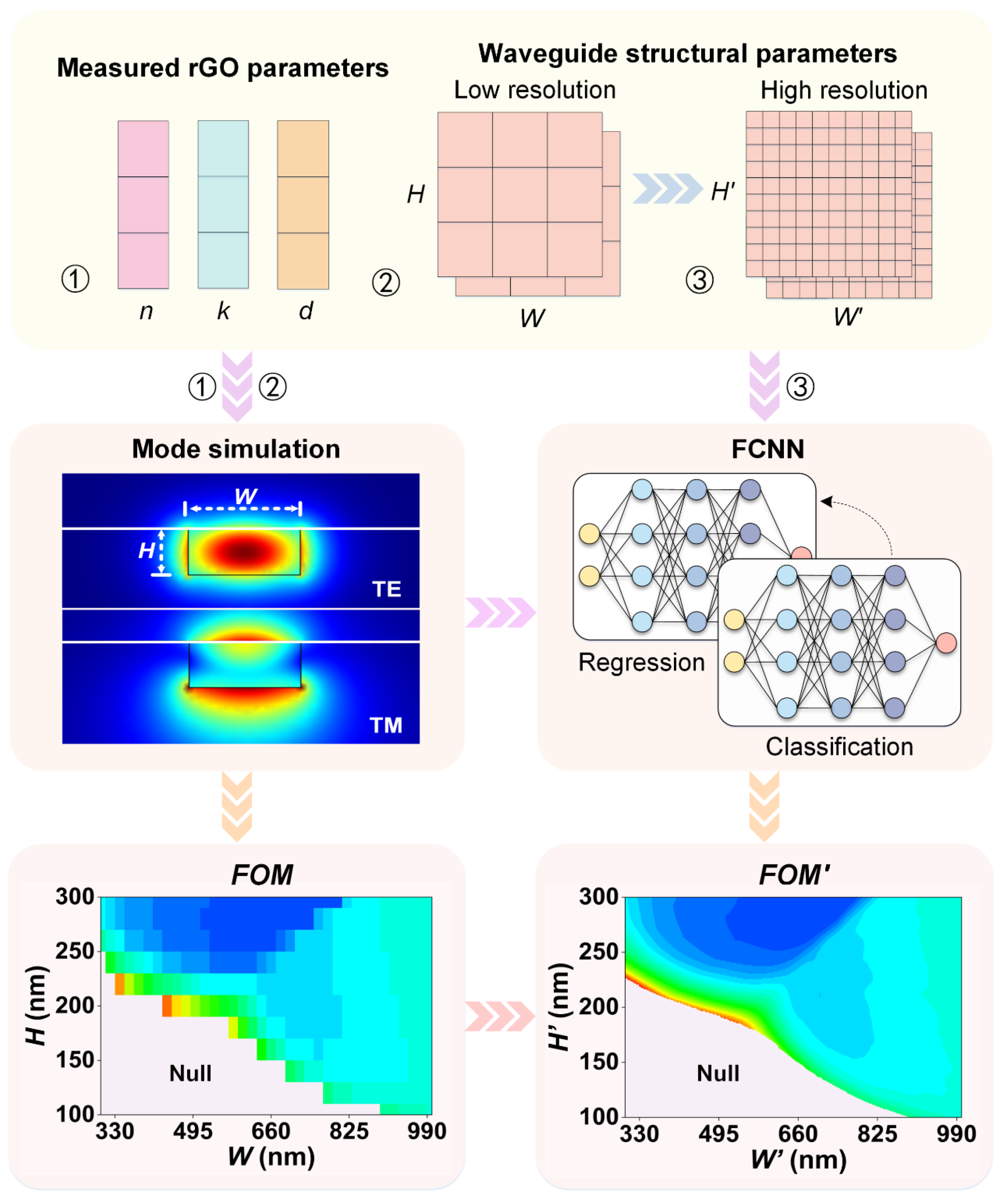

2. Device Structure

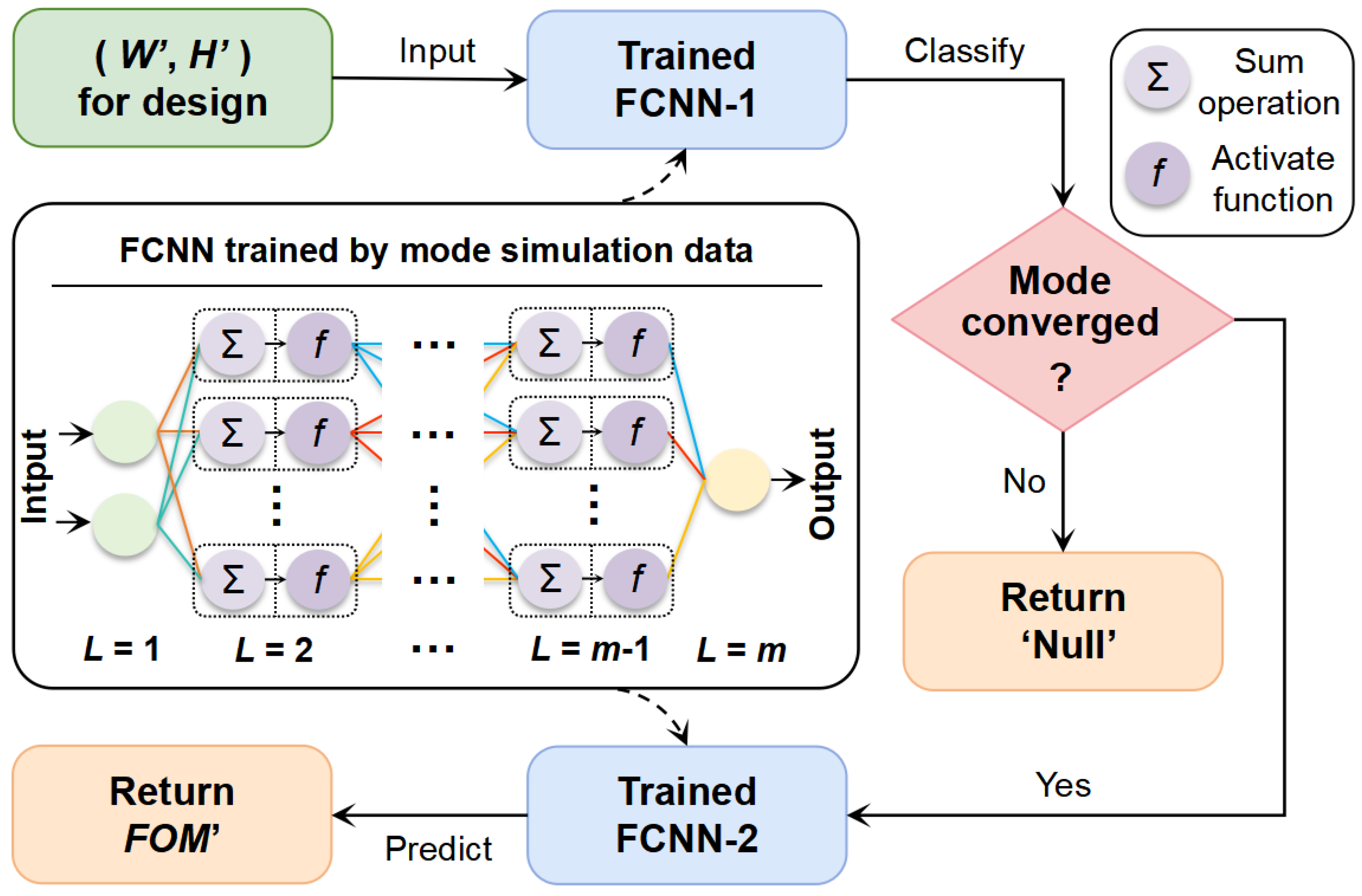

3. FCNN-Based Machine Learning Framework

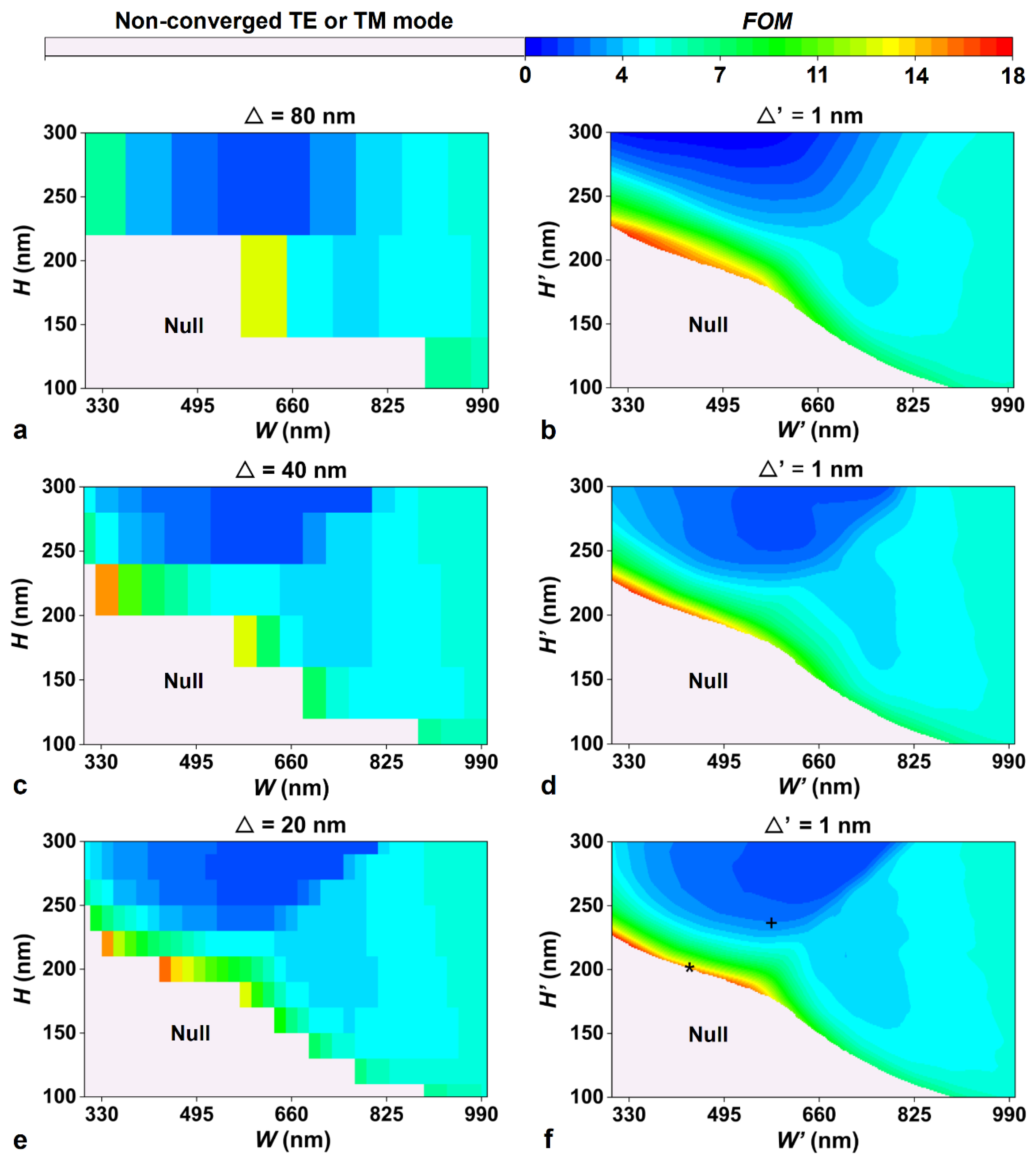

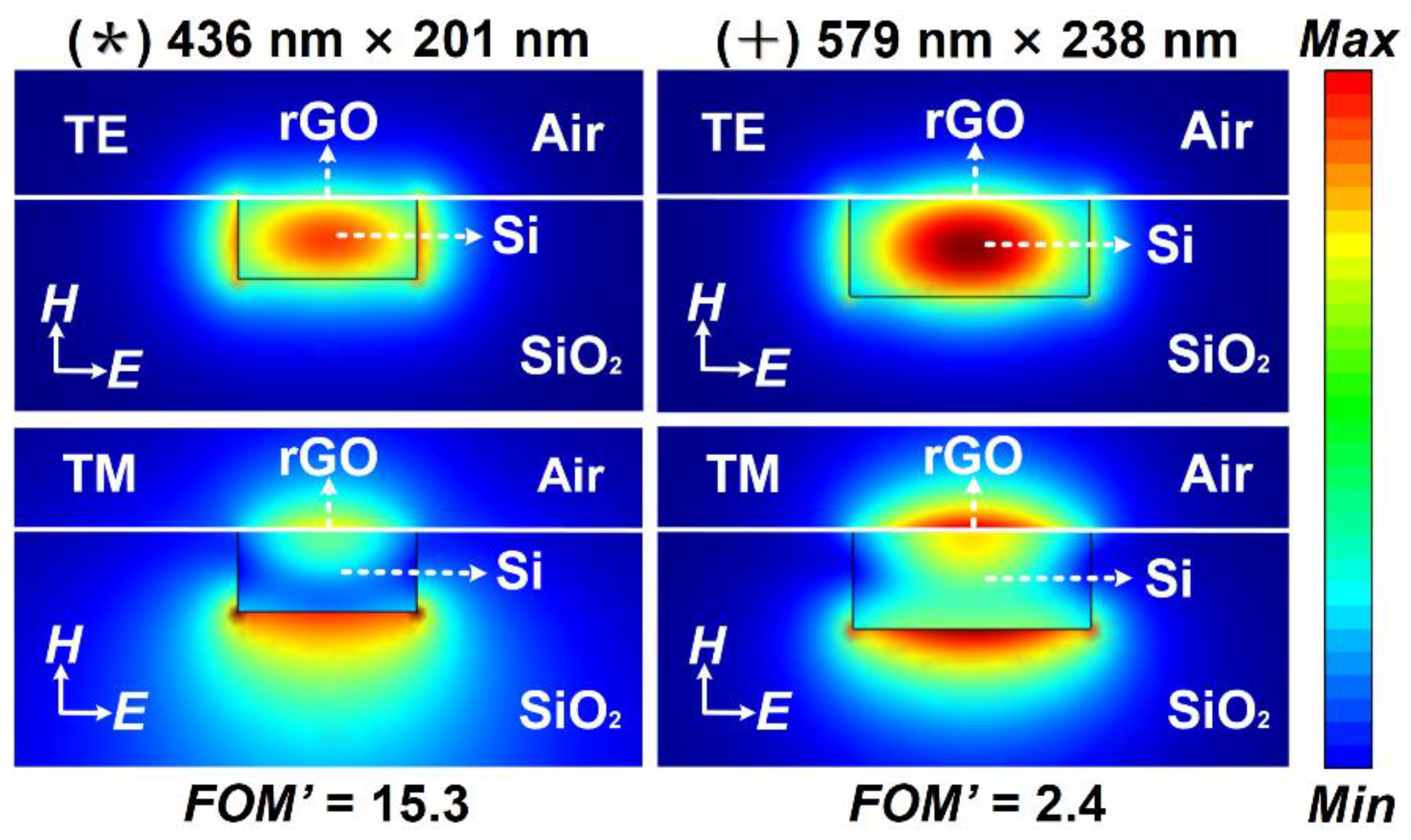

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D. Dai, L. Liu, S. Gao, D. X. Xu, and S. He, “Polarization management for silicon photonic integrated circuits,” Laser & Photonics Reviews, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 303-328, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. He, H. He, J. Chang, B. Chen, H. Ma, and M. J. Booth, “Polarisation optics for biomedical and clinical applications: a review,” Light: Science & Applications, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 194, 2021/09/22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Bao, H. Zhang, B. Wang, Z. Ni, C. H. Y. X. Lim, Y. Wang, D. Y. Tang, and K. P. Loh, “Broadband graphene polarizer,” Nature Photonics, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 411-415, 2011/07/01, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J. Wu, J. Linnan, D. Jin, B. Jia, X. Hu, D. Moss, and Q. Gong, “Advanced optical polarizers based on 2D materials,” npj Nanophotonics, vol. 1, 07/17, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. T. Kim, and H. Choi, “Polarization control in graphene-based polymer waveguide polarizer,” Laser & Photonics Reviews, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 1800142, 2018/10/01, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu, Y. Yang, Y. Qu, X. Xu, Y. Liang, S. T. Chu, B. E. Little, R. Morandotti, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Graphene oxide waveguide and micro--ring resonator polarizers,” Laser & Photonics Reviews, vol. 13, no. 9, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Lin, Y. Song, Y. Huang, D. Kita, S. Deckoff-Jones, K. Wang, L. Li, J. Li, H. Zheng, Z. Luo, H. Wang, S. Novak, A. Yadav, C.-C. Huang, R.-J. Shiue, D. Englund, T. Gu, D. Hewak, K. Richardson, J. Kong, and J. Hu, “Chalcogenide glass-on-graphene photonics,” Nature Photonics, vol. 11, no. 12, pp. 798-805, 2017/12/01, 2017.

- J. Hu, J. Wu, D. Jin, W. Liu, Y. Zhang, Y. Yang, L. Jia, Y. Wang, D. Huang, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Integrated photonic polarizers with 2D reduced graphene oxide,” Opto-Electronic Science, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 240032, 2025/02/26, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Hu, J. Wu, W. Liu, D. Jin, H. E. Dirani, S. Kerdiles, C. Sciancalepore, P. Demongodin, C. Grillet, C. Monat, D. Huang, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “2D graphene oxide: a versatile thermo--optic material,” Advanced Functional Materials, vol. 34, no. 46, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu, H. Lin, D. J. Moss, K. P. Loh, and B. Jia, “Graphene oxide for photonics, electronics and optoelectronics,” Nature Reviews Chemistry, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 162-183, 2023/03/01, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu, Y. Zhang, J. Hu, Y. Yang, D. Jin, W. Liu, D. Huang, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “2D graphene oxide films expand functionality of photonic chips,” Advanced Materials, vol. 36, no. 31, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Lin, B. C. P. Sturmberg, K.-T. Lin, Y. Yang, X. Zheng, T. K. Chong, C. M. de Sterke, and B. Jia, “A 90-nm-thick graphene metamaterial for strong and extremely broadband absorption of unpolarized light,” Nature Photonics, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 270-276, 2019/04/01, 2019. [CrossRef]

- K.-T. Lin, H. Lin, T. Yang, and B. Jia, “Structured graphene metamaterial selective absorbers for high efficiency and omnidirectional solar thermal energy conversion,” Nature Communications, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1389, 2020/03/13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, H. Lin, B. Y. Zhang, Y. Zhang, X. Zheng, A. Yu, M. Hong, and B. Jia, “Graphene-based multilayered metamaterials with phototunable architecture for on-chip photonic devices,” ACS Photonics, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 1033-1040, 2019/04/17, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J. Wu, L. Jia, Y. Qu, Y. Yang, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Graphene oxide for nonlinear integrated photonics,” Laser & Photonics Reviews, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 2200512, 2023/03/01, 2023. [CrossRef]

- O. Kovalchuk, S. Gong, H. Moon, and Y.-W. Song, “Graphene-advanced functional devices for integrated photonic platforms,” npj Nanophotonics, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 31, 2025/07/07, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen, and J. Wang, “Three-dimensional dispersive hybrid implicit-explicit finite-difference time-domain method for simulations of graphene,” Computer Physics Communications, vol. 207, pp. 211-216, 2016/10/01/, 2016. [CrossRef]

- W. Chen, and Q. Zhu, “FDTD algorithm for subcell model with cells containing layers of graphene thin sheets,” IEICE Electronics Express, vol. 21, no. 21, pp. 20240449-20240449, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. R. Wiecha, A. Arbouet, C. Girard, and O. L. Muskens, “Deep learning in nano-photonics: inverse design and beyond,” Photonics Research, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. B182-B200, 2021/05/01, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Yang, M. A. Guidry, D. M. Lukin, K. Yang, and J. Vučković, “Inverse-designed silicon carbide quantum and nonlinear photonics,” Light: Science & Applications, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 201, 2023/08/22, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Ma, Z. Liu, Z. A. Kudyshev, A. Boltasseva, W. Cai, and Y. Liu, “Deep learning for the design of photonic structures,” Nature photonics, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 77-90, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Molesky, Z. Lin, A. Y. Piggott, W. Jin, J. Vucković, and A. W. Rodriguez, “Inverse design in nanophotonics,” Nature Photonics, vol. 12, no. 11, pp. 659-670, 2018/11/01, 2018.

- J. Jiang, M. Chen, and J. Fan, “Deep neural networks for the evaluation and design of photonic devices,” Nature Reviews Materials, vol. 6, 12/17, 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. Malkiel, M. Mrejen, A. Nagler, U. Arieli, L. Wolf, and H. Suchowski, “Plasmonic nanostructure design and characterization via deep learning,” Light: Science & Applications, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 60, 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, M. Tan, B. Corcoran, J. Wu, A. Boes, T. G. Nguyen, S. T. Chu, B. E. Little, D. G. Hicks, R. Morandotti, A. Mitchell, and D. J. Moss, “11 tops photonic convolutional accelerator for optical neural networks,” Nature, vol. 589, no. 7840, pp. 44-51, 2021/01/01, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, X. Zhang, Y. Fu, and Y. Liu, “Interfacing photonics with artificial intelligence: A new design strategy for photonic structures and devices based on artificial neural networks,” Photonics Research, vol. 9, 02/05, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Peurifoy, Y. Shen, L. Jing, Y. Yang, F. Cano-Renteria, B. G. DeLacy, J. D. Joannopoulos, M. Tegmark, and M. Soljačić, “Nanophotonic particle simulation and inverse design using artificial neural networks,” Science Advances, vol. 4, no. 6, pp. eaar4206, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Dory, D. Vercruysse, K. Y. Yang, N. V. Sapra, A. E. Rugar, S. Sun, D. M. Lukin, A. Y. Piggott, J. L. Zhang, M. Radulaski, K. G. Lagoudakis, L. Su, and J. Vučković, “Inverse-designed diamond photonics,” Nature Communications, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 3309, 2019/07/25, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. He, J. R. Nolen, J. Nordlander, A. Cleri, N. S. McIlwaine, Y. Tang, G. Lu, T. G. Folland, B. A. Landman, and J.-P. Maria, “Deterministic inverse design of Tamm plasmon thermal emitters with multi-resonant control,” Nature materials, vol. 20, no. 12, pp. 1663-1669, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Mohammadi Estakhri, B. Edwards, and N. Engheta, “Inverse-designed metastructures that solve equations,” Science, vol. 363, no. 6433, pp. 1333-1338, 2019/03/22, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, D. Zhu, S. P. Rodrigues, K.-T. Lee, and W. Cai, “Generative model for the inverse design of metasurfaces,” Nano Letters, vol. 18, no. 10, pp. 6570-6576, 2018/10/10, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Zhu, Z. Zong, E. Li, Y. Lu, J. Zhang, H. Xie, Y. Li, W.-Y. Yin, and Z. Wei, “Frequency transfer and inverse design for metasurface under multi-physics coupling by Euler latent dynamic and data-analytical regularizations,” Nature Communications, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 2251, 2025/03/06, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhu, T. Qiu, J. Wang, S. Sui, C. Hao, T. Liu, Y. Li, M. Feng, A. Zhang, C.-W. Qiu, and S. Qu, “Phase-to-pattern inverse design paradigm for fast realization of functional metasurfaces via transfer learning,” Nature Communications, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 2974, 2021/05/20, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Ueno, J. Hu, and S. An, “AI for optical metasurface,” npj Nanophotonics, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 36, 2024/09/02, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Q. Fan, G. Zhou, T. Gui, C. Lu, and A. P. T. Lau, “Advancing theoretical understanding and practical performance of signal processing for nonlinear optical communications through machine learning,” Nature Communications, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 3694, 2020/07/23, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Genty, L. Salmela, J. M. Dudley, D. Brunner, A. Kokhanovskiy, S. Kobtsev, and S. K. Turitsyn, “Machine learning and applications in ultrafast photonics,” Nature Photonics, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 91-101, 2021/02/01, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Aparecido de Paula, I. Aldaya, T. Sutili, R. C. Figueiredo, J. L. Pita, and Y. R. R. Bustamante, “Design of a silicon Mach–Zehnder modulator via deep learning and evolutionary algorithms,” Scientific Reports, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 14662, 2023/09/05, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Oh, H. Kim, M. Meyyappan, and K. Kim, “Design and analysis of Near-IR photodetector using machine learning approach,” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 24, no. 16, pp. 25565-25572, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. A. W. Ayyubi, M. X. Low, S. Salimi, M. Khorsandi, M. M. Hossain, H. Arooj, S. Masood, M. H. Zeb, N. Mahmood, Q. Bao, S. Walia, and B. Shabbir, “Machine learning-assisted high-throughput prediction and experimental validation of high-responsivity extreme ultraviolet detectors,” Nature Communications, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 6265, 2025/07/07, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. B. Choi, J. S. Choi, H. S. Shin, J.-W. Yoon, Y. Kim, and J.-W. Kim, “Deep learning-developed multi-light source discrimination capability of stretchable capacitive photodetector,” npj Flexible Electronics, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 44, 2025/05/15, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. A. Kudyshev, V. M. Shalaev, and A. Boltasseva, “Machine learning for integrated quantum photonics,” ACS Photonics, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 34-46, 2021/01/20, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. A. Kudyshev, D. Sychev, Z. Martin, O. Yesilyurt, S. I. Bogdanov, X. Xu, P.-G. Chen, A. V. Kildishev, A. Boltasseva, and V. M. Shalaev, “Machine learning assisted quantum super-resolution microscopy,” Nature Communications, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 4828, 2023/08/10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Torlai, G. Mazzola, J. Carrasquilla, M. Troyer, R. Melko, and G. Carleo, “Neural-network quantum state tomography,” Nature Physics, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 447-450, 2018/05/01, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Eda, G. Fanchini, and M. Chhowalla, “Large-area ultrathin films of reduced graphene oxide as a transparent and flexible electronic material,” Nature Nanotechnology, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 270-274, 2008/05/01, 2008. [CrossRef]

- K. Erickson, R. Erni, Z. Lee, N. Alem, W. Gannett, and A. Zettl, “Determination of the local chemical structure of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide,” Advanced Materials, vol. 22, no. 40, pp. 4467-4472, 2010/10/25, 2010. [CrossRef]

- H. Feng, R. Cheng, X. Zhao, X. Duan, and J. Li, “A low-temperature method to produce highly reduced graphene oxide,” Nature Communications, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1539, 2013/02/26, 2013. [CrossRef]

- I. K. Moon, J. Lee, R. S. Ruoff, and H. Lee, “Reduced graphene oxide by chemical graphitization,” Nature Communications, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 73, 2010/09/21, 2010. [CrossRef]

- D. Voiry, J. Yang, J. Kupferberg, R. Fullon, C. Lee, H. Y. Jeong, H. S. Shin, and M. Chhowalla, “High-quality graphene via microwave reduction of solution-exfoliated graphene oxide,” Science, vol. 353, no. 6306, pp. 1413-1416, 2016/09/23, 2016.

- D. Jin, J. Wu, J. Hu, W. Liu, Y. Zhang, Y. Yang, L. Jia, D. Huang, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Silicon photonic waveguide and microring resonator polarizers incorporating 2D graphene oxide films,” Applied Physics Letters, vol. 125, no. 5, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. S. Chong, S. X. Gan, C. K. Lai, W. Y. Chong, D. Choi, S. Madden, R. M. D. L. Rue, and H. Ahmad, “Configurable TE- and TM-pass graphene oxide-coated waveguide polarizer,” IEEE Photonics Technology Letters, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 627-630, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Lim, Y. Yap, W. Chong, S. Pua, H. Ming, R. De La Rue, and H. Ahmad, “Graphene oxide-based waveguide polariser: from thin film to quasi-bulk,” Optics Express, vol. 22, pp. 11090-11098, 05/01, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Bagri, C. Mattevi, M. Acik, Y. J. Chabal, M. Chhowalla, and V. B. Shenoy, “Structural evolution during the reduction of chemically derived graphene oxide,” Nature Chemistry, vol. 2, no. 7, pp. 581-587, 2010/07/01, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Fatkullin, D. Cheshev, A. Averkiev, A. Gorbunova, G. Murastov, J. Liu, P. Postnikov, C. Cheng, R. D. Rodriguez, and E. Sheremet, “Photochemistry dominates over photothermal effects in the laser-induced reduction of graphene oxide by visible light,” Nature Communications, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 9711, 2024/11/09, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Qu, J. Wu, Y. Zhang, Y. Yang, L. Jia, H. E. Dirani, S. Kerdiles, C. Sciancalepore, P. Demongodin, C. Grillet, C. Monat, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Integrated optical parametric amplifiers in silicon nitride waveguides incorporated with 2D graphene oxide films,” Light: Advanced Manufacturing, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu, L. Jia, Y. Zhang, Y. Qu, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Graphene oxide for integrated photonics and flat optics,” Advanced Materials, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 2006415, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. P. Loh, Q. Bao, G. Eda, and M. Chhowalla, “Graphene oxide as a chemically tunable platform for optical applications,” Nature Chemistry, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 1015-1024, 2010/12/01, 2010. [CrossRef]

- V. C. Tung, M. J. Allen, Y. Yang, and R. B. Kaner, “High-throughput solution processing of large-scale graphene,” Nature Nanotechnology, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 25-29, 2009/01/01, 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. Y. N. Gengler, D. S. Badali, D. Zhang, K. Dimos, K. Spyrou, D. Gournis, and R. J. D. Miller, “Revealing the ultrafast process behind the photoreduction of graphene oxide,” Nature Communications, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 2560, 2013/10/04, 2013. [CrossRef]

- W. Jiang, J. Hu, J. Wu, D. Jin, W. Liu, Y. Zhang, L. Jia, Y. Wang, D. Huang, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Enhanced thermo-optic performance of silicon microring resonators integrated with 2D graphene oxide films,” ACS Applied Electronic Materials, vol. 7, no. 12, pp. 5650-5661, 2025/06/24, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Arianfard, S. Juodkazis, D. J. Moss, and J. Wu, “Sagnac interference in integrated photonics,” Applied Physics Reviews, vol. 10, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Jin, S. Ren, J. Hu, D. Huang, D. J. Moss, and J. Wu, “Modeling of complex integrated photonic resonators using the scattering matrix method,” Photonics, vol. 11, no. 12, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Fu, J. Zhang, R. Sun, Y. Huang, W. Xu, S. Yang, Z. Zhu, and H. Chen, “Optical neural networks: progress and challenges,” Light: Science & Applications, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 263, 2024/09/20, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, Z. Zhou, C. Qiu, Y. Chen, B. Liang, Y. Wang, L. Liang, Y. Lei, Y. Song, P. Jia, Y. Zeng, L. Qin, Y. Ning, and L. Wang, “The intelligent design of silicon photonic devices,” Advanced Optical Materials, vol. 12, no. 7, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. LeCun, Y. Bengio, and G. Hinton, “Deep learning,” Nature, vol. 521, no. 7553, pp. 436-444, 2015/05/01, 2015.

- N. Wu, Y. Sun, J. Hu, C. Yang, Z. Bai, F. Wang, X. Cui, S. He, Y. Li, C. Zhang, K. Xu, J. Guan, S. Xiao, and Q. Song, “Intelligent nanophotonics: when machine learning sheds light,” eLight, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 5, 2025/04/11, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Zhu, J. Zou, H. Zhang, Y. Z. Shi, S. B. Luo, N. Wang, H. Cai, L. X. Wan, B. Wang, X. D. Jiang, J. Thompson, X. S. Luo, X. H. Zhou, L. M. Xiao, W. Huang, L. Patrick, M. Gu, L. C. Kwek, and A. Q. Liu, “Space-efficient optical computing with an integrated chip diffractive neural network,” Nature Communications, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1044, 2022/02/24, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, “Delving deep into rectifiers: surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification,” IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), pp. 1026-1034, 2015.

- I. B. Goodfellow, Yoshua; Courville, Courville., Deep learning, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016.

- G. E. P. Box, and G. M. Jenkins, Time series analysis: Forecasting and control: Prentice Hall PTR, 1994.

- Y. Qu, J. Wu, Y. Zhang, L. Jia, Y. Liang, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Analysis of Four-Wave Mixing in Silicon Nitride Waveguides Integrated With 2D Layered Graphene Oxide Films,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 39, no. 9, pp. 2902–2910, 2021/05//, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J. Wu, Y. Qu, L. Jia, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Optimizing the Kerr Nonlinear Optical Performance of Silicon Waveguides Integrated With 2D Graphene Oxide Films,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 39, no. 14, pp. 4671–4683, 2021/07//, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu, Y. Yang, Y. Qu, L. Jia, Y. Zhang, X. Xu, S. T. Chu, B. E. Little, R. Morandotti, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “2D Layered Graphene Oxide Films Integrated with Micro-Ring Resonators for Enhanced Nonlinear Optics,” Small, vol. 16, no. 16, pp. 1906563, 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J. Wu, L. Jia, Y. Qu, Y. Yang, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Graphene Oxide for Nonlinear Integrated Photonics,” Laser & Photonics Reviews, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 2200512, 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Qu, J. Wu, Y. Yang, Y. Zhang, Y. Liang, H. El Dirani, R. Crochemore, P. Demongodin, C. Sciancalepore, C. Grillet, C. Monat, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Enhanced Four-Wave Mixing in Silicon Nitride Waveguides Integrated with 2D Layered Graphene Oxide Films,” Advanced Optical Materials, vol. 8, no. 23, pp. 2001048, 2020, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J. Wu, Y. Yang, Y. Qu, L. Jia, T. Moein, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Enhanced Kerr Nonlinearity and Nonlinear Figure of Merit in Silicon Nanowires Integrated with 2D Graphene Oxide Films,” ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, vol. 12, no. 29, pp. 33094–33103, 2020/07/22/, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yang, J. Wu, X. Xu, Y. Liang, S. T. Chu, B. E. Little, R. Morandotti, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Invited Article: Enhanced four-wave mixing in waveguides integrated with graphene oxide,” APL Photonics, vol. 3, no. 12, pp. 120803, 2018/10/24/, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Qu, J. Wu, Y. Zhang, Y. Yang, L. Jia, H. E. Dirani, S. Kerdiles, C. Sciancalepore, P. Demongodin, C. Grillet, C. Monat, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Integrated optical parametric amplifiers in silicon nitride waveguides incorporated with 2D graphene oxide films,” Light: Advanced Manufacturing, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 437, 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Junkai Hu, Jiayang Wu, Irfan H. Abidi, Di Jin, Yuning Zhang, Yijun Wang, Sumeet Walia, and David J. Moss, “Silicon photonic polarizers incorporating 2D MoS2 films”, Invited Paper, IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, VOL. 32, NO. 2, 6100111 (2026). DOI:10.1109/JSTQE.2025.3610438. [CrossRef]

- P. Demongodin, H. El Dirani, J. Lhuillier, R. Crochemore, M. Kemiche, T. Wood, S. Callard, P. Rojo-Romeo, C. Sciancalepore, C. Grillet, and C. Monat, “Ultrafast saturable absorption dynamics in hybrid graphene/Si <sub>3</sub> N <sub>4</sub> waveguides,” APL Photonics, vol. 4, no. 7, pp. 076102, 2019/07//, 2019.

- H. El Dirani, A. Kamel, M. Casale, S. Kerdiles, C. Monat, X. Letartre, M. Pu, L. K. Oxenløwe, K. Yvind, and C. Sciancalepore, “Annealing-free Si3N4 frequency combs for monolithic integration with Si photonics,” Applied Physics Letters, vol. 113, no. 8, pp. 081102, 2018/08/21/, 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Jia, J. Wu, Y. Zhang, Y. Qu, B. Jia, Z. Chen, and D. J. Moss, “Fabrication Technologies for the On-Chip Integration of 2D Materials,” Small Methods, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 2101435, 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J. Wu, Y. Yang, Y. Qu, H. E. Dirani, R. Crochemore, C. Sciancalepore, P. Demongodin, C. Grillet, C. Monat, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Enhanced Self-Phase Modulation in Silicon Nitride Waveguides Integrated With 2D Graphene Oxide Films,” IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics, vol. 29, no. 1: Nonlinear Integrated Photonics, 29 (1) 5100413 (2023). DOI: 2023/01//, 2023. DOI: 10.1109/JSTQE.2022.3177385,. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, J. Wu, Y. Yang, Y. Qu, L. Jia, H. E. Dirani, S. Kerdiles, C. Sciancalepore, P. Demongodin, C. Grillet, C. Monat, B. Jia, and D. J. Moss, “Enhanced Supercontinuum Generation in Integrated Waveguides Incorporated with Graphene Oxide Films,” Advanced Materials Technologies, vol. 8, no. 9, pp. 2201796, 2023/05//, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Hu et al., “Integrated waveguide and microring polarizers incorporating 2D reduced graphene oxide”, Opto-Electronic Science 4 240032 (2025).

- Y. Qu et al.,”Integrated optical parametric amplifiers in silicon nitride waveguides incorporated with 2D graphene oxide films”, Light: Advanced Manufacturing 4 39 (2023).

- J. Wu et al., “Novel functionality with 2D graphene oxide films integrated on silicon photonic chips”, Advanced Materials Vol. 36 2403659 (2024).

- Y. Zhang et al., “Enhanced spectral broadening of femtosecond optical pulses in silicon nanowires integrated with 2D graphene oxide films”, Micromachines Vol. 13 756 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “Design and optimization of four-wave mixing in microring resonators integrated with 2D graphene oxide films”, Journal of Lightwave Technology Vol. 39 (20) 6553-6562 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. et al., “Graphene oxide waveguide and micro-ring resonator polarizers”, Laser and Photonics Reviews Vol. 13, 1900056 (2019). [CrossRef]

- J. Wu et al., “Graphene oxide: versatile films for flat optics to nonlinear photonic chips”, Advanced Materials Vol. 33 (3) 2006415, 1-29 (2021).

- Y. Qu et al., “Photo thermal tuning in GO-coated integrated waveguides”, Micromachines Vol. 13 1194 (2022).

- J. Wu et al., “Graphene oxide for electronics, photonics, and optoelectronics”, Nature Reviews Chemistry 7 (3) 162–183 (2023).

- D. Jin et al., “Silicon photonic waveguide and microring resonator polarizers incorporating 2D graphene oxide films”, Applied Physics Letters, Vol. 125, 053101 (2024). [CrossRef]

- J. Hu et al., “2D graphene oxide: a versatile thermo-optic material”, Advanced Functional Materials 34 2406799 (2024). [CrossRef]

- D.J.Moss, J.Sipe, and H.van Driel, “ Empirical tight-binding calculation of dispersion in the second-order nonlinear optical constant for zinc-blende crystals”, Physical Review B 36 9708 (1987).

- D. Jin et al., “Thickness and Wavelength Dependent Nonlinear Optical Absorption in 2D Layered MXene Films”, Small Science 4 2400179 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “Advanced optical polarizers based on 2D materials”, npj Nanophotonics 1, 28 (2024). DOI:10.1038/s44310-024-00028-3. [CrossRef]

- L. Jia et al., “Third-order optical nonlinearities of 2D materials at telecommunications wavelengths”, Micromachines, 14 307 (2023). [CrossRef]

- L. Jia et. al., “Fabrication Technologies for the On-Chip Integration of 2D Materials”, Small: Methods Vol. 6, 2101435 (2022).

- L. Jia et al., “BiOBr nanoflakes with strong nonlinear optical properties towards hybrid integrated photonic devices”, Applied Physics Letters Photonics vol. 4 090802 vol. (2019).

- L. Jia et al. “Large Third-Order Optical Kerr Nonlinearity in Nanometer-Thick PdSe2 2D Dichalcogenide Films: Implications for Nonlinear Photonic Devices”, ACS Applied Nano Materials vol. 3 (7) 6876–6883 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang et al., “2D material integrated photonics: towards industrial manufacturing and commercialization”, Applied Physics Letters Photonics 10, 040903 (2025). [CrossRef]

- L. Razzari et al.,”CMOS compatible integrated optical hyper-parametric oscillator”, Nature Photonics 4 41-44 (2010).

- A. Pasquazi, et al., “Sub-picosecond phase-sensitive optical pulse characterization on a chip”, Nature Photonics, vol. 5, no. 10, pp. 618-623 (2011). [CrossRef]

- M Ferrera et al., “On-Chip ultra-fast 1st and 2nd order CMOS compatible all-optical integration”, Optics Express vol. 19 (23), 23153-23161 (2011).

- Bao, C., et al., Direct soliton generation in microresonators, Opt. Lett, 42, 2519 (2017). [CrossRef]

- M.Ferrera et al., “CMOS compatible integrated all-optical RF spectrum analyzer”, Optics Express, vol. 22, no. 18, 21488 - 21498 (2014).

- M. Kues, et al., “Passively modelocked laser with an ultra-narrow spectral width”, Nature Photonics, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 159, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Ferrera et al.”On-Chip ultra-fast 1st and 2nd order CMOS compatible all-optical integration”, Opt. Express, vol. 19, (23)pp. 23153-23161 (2011).

- D. Duchesne, M. Peccianti, M. R. E. Lamont, et al., “Supercontinuum generation in a high index doped silica glass spiral waveguide,” Optics Express, vol. 18, no, 2, pp. 923-930, 2010. [CrossRef]

- H Bao et al., “Turing patterns in a fiber laser with a nested microresonator: Robust and controllable microcomb generation”, Physical Review Research vol. 2 (2), 023395 (2020). [CrossRef]

- M. Ferrera, et al., “On-chip CMOS-compatible all-optical integrator”, Nature Communications, vol. 1, Article 29, 2010. [CrossRef]

- A. Pasquazi, et al., “All-optical wavelength conversion in an integrated ring resonator,” Optics Express, vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 3858-3863, 2010.

- A.Pasquazi et al., “Efficient wavelength conversion and net parametric gain via Four Wave Mixing in a high index doped silica waveguide,” Optics Express, vol. 18, no. 8, 7634-7641, 2010.

- M. Ferrera et al., “Low Power CW Parametric Mixing in a Low Dispersion High Index Doped Silica Glass Micro-Ring Resonator with Q-factor > 1 Million”, Optics Express, vol.17, no. 16, pp. 14098–14103 (2009).

- M. Peccianti, et al., “Demonstration of an ultrafast nonlinear microcavity modelocked laser”, Nature Communications, vol. 3, pp. 765, 2012.

- A.Pasquazi, et al., “Self-locked optical parametric oscillation in a CMOS compatible microring resonator: a route to robust optical frequency comb generation on a chip,” Optics Express, vol. 21, no. 11, pp. 13333-13341, 2013.

- A.Pasquazi, et al., “Stable, dual mode, high repetition rate mode-locked laser based on a microring resonator,” Optics Express, vol. 20, no. 24, pp. 27355-27362, 2012.

- Pasquazi, A. et al. Micro-combs: a novel generation of optical sources. Physics Reports 729, 1-81 (2018). [CrossRef]

- H. Bao, et al., Laser cavity-soliton microcombs, Nature Photonics, vol. 13, no. 6, pp. 384-389, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Cutrona et al., “High Conversion Efficiency in Laser Cavity-Soliton Microcombs”, Optics Express Vol. 30, Issue 22, pp. 39816-39825 (2022).

- M.Rowley et al., “Self-emergence of robust solitons in a micro-cavity”, Nature vol. 608 (7922) 303–309 (2022).

- A. Cutrona et al., “Nonlocal bonding of a soliton and a blue-detuned state in a microcomb laser”, Nature Communications Physics 6 Article 259 (2023). [CrossRef]

- A. A. Rahim et al., “Mode-locked laser with multiple timescales in a microresonator-based nested cavity”, APL Photonics 9 031302 (2024). DOI:10.1063/5.0174697. [CrossRef]

- A. Cooper et al., “Parametric interaction of laser cavity-solitons with an external CW pump”, Optics Express 32 (12), 21783-21794 (2024). [CrossRef]

- A. Cutrona et al., “Stability Properties of Laser Cavity-Solitons for Metrological Applications”, Applied Physics Letters vol. 122 (12) 121104 (2023); doi: 10.1063/5.0134147. [CrossRef]

- C.E. Murray et al., “Investigating the thermal robustness of soliton crystal microcombs”, Optics Express 31(23), 37749-37762 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun et al., “Enhancing laser temperature stability by passive self-injection locking to a micro-ring resonator”, Optics Express 32 (13) 23841-23855 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun et al., “Applications of optical micro-combs”, Advances in Optics and Photonics 15 (1) 86-175 (2023).

- X. Xu et al., “Reconfigurable broadband microwave photonic intensity differentiator based on an integrated optical frequency comb source,” APL Photonics, vol. 2, no. 9, 096104, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., et al., Photonic microwave true time delays for phased array antennas using a 49 GHz FSR integrated micro-comb source, Photonics Research, vol. 6, B30-B36 (2018). [CrossRef]

- X. Xu et al., “Microcomb-based photonic RF signal processing”, IEEE Photonics Technology Letters, vol. 31 no. 23 1854-1857, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Xu, et al., “Advanced adaptive photonic RF filters with 80 taps based on an integrated optical micro-comb source,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 1288-1295 (2019).

- X. Xu, et al., “Photonic RF and microwave integrator with soliton crystal microcombs”, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs, vol. 67, no. 12, pp. 3582-3586, 2020.

- X. Xu, et al., “High performance RF filters via bandwidth scaling with Kerr micro-combs,” APL Photonics, vol. 4 (2) 026102. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Tan, et al., “Microwave and RF photonic fractional Hilbert transformer based on a 50 GHz Kerr micro-comb”, Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 37, no. 24, pp. 6097 – 6104, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Tan, et al., “RF and microwave fractional differentiator based on photonics”, IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems: Express Briefs, vol. 67, no.11, pp. 2767-2771, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Tan, et al., “Photonic RF arbitrary waveform generator based on a soliton crystal micro-comb source”, Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 38, no. 22, pp. 6221-6226 (2020). [CrossRef]

- M. Tan et al., “RF and microwave high bandwidth signal processing based on Kerr Micro-combs”, Advances in Physics X, VOL. 6, NO. 1, 1838946 (2021).

- X. Xu, et al., “Advanced RF and microwave functions based on an integrated optical frequency comb source,” Opt. Express, vol. 26 (3) 2569 (2018). [CrossRef]

- M. Tan et al., “Highly Versatile Broadband RF Photonic Fractional Hilbert Transformer Based on a Kerr Soliton Crystal Microcomb”, Journal of Lightwave Technology vol. 39 (24) 7581-7587 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. et al., “RF Photonics: An Optical Microcombs’ Perspective”, IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics Vol. 24, 6101020, 1-20 (2018).

- T. G. Nguyen et al., “Integrated frequency comb source-based Hilbert transformer for wideband microwave photonic phase analysis,” Optics Express, vol. 23, no. 17, pp. 22087-22097, 2015. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, et al., “Broadband RF channelizer based on an integrated optical frequency Kerr comb source,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 36, no. 19, pp. 4519-4526, 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, et al., “Continuously tunable orthogonally polarized RF optical single sideband generator based on micro-ring resonators,” Journal of Optics, vol. 20, no. 11, 115701. 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, et al., “Orthogonally polarized RF optical single sideband generation and dual-channel equalization based on an integrated microring resonator,” Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 36, no. 20, pp. 4808-4818. 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, et al., “Photonic RF phase-encoded signal generation with a microcomb source”, J. Lightwave Technology, vol. 38, no. 7, 1722-1727, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, et al., Broadband microwave frequency conversion based on an integrated optical micro-comb source”, Journal of Lightwave Technology, vol. 38 no. 2, pp. 332-338, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Tan, et al., “Photonic RF and microwave filters based on 49GHz and 200GHz Kerr microcombs”, Optics Comm. vol. 465,125563, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, et al., “Broadband photonic RF channelizer with 90 channels based on a soliton crystal microcomb”, Journal of Lightwave Technology, Vol. 38, no. 18, pp. 5116 – 5121 (2020). [CrossRef]

- M. Tan et al., “Orthogonally polarized Photonic Radio Frequency single sideband generation with integrated micro-ring resonators”, IOP Journal of Semiconductors, Vol. 42 (4), 041305 (2021).

- M.Tan et al., “Photonic Radio Frequency Channelizers based on Kerr Optical Micro-combs”, IOP Journal of Semiconductors Vol. 42 (4), 041302 (2021).

- B. Corcoran, et al., “Ultra-dense optical data transmission over standard fiber with a single chip source”, Nature Communications, vol. 11, Article:2568, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu et al., “Photonic perceptron based on a Kerr microcomb for scalable high speed optical neural networks”, Laser and Photonics Reviews, vol. 14, no. 8, 2000070 (2020).

- X. Xu, et al., “11 TOPs photonic convolutional accelerator for optical neural networks”, Nature vol. 589, 44-51 (2021). [CrossRef]

- X. Xu et al., “Neuromorphic computing based on wavelength-division multiplexing”, IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 29 (2) 7400112 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Bai et al., “Photonic multiplexing techniques for neuromorphic computing”, Nanophotonics vol. 12 (5): 795–817 (2023). [CrossRef]

- C. Prayoonyong et al.,”Frequency comb distillation for optical superchannel transmission”, Journal of Lightwave Technology vol. 39 (23) 7383-7392 (2021).

- M. Tan et al., “Integral order photonic RF signal processors based on a soliton crystal micro-comb source”, IOP Journal of Optics vol. 23 (11) 125701 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun et al., “Optimizing the performance of microcomb based microwave photonic transversal signal processors”, Journal of Lightwave Technology vol. 41 (23) pp 7223-7237 (2023). [CrossRef]

- M. Tan et al., “Photonic signal processor for real-time video image processing based on a Kerr microcomb”, Nature Communications Engineering 2 94 (2023).

- M. Tan, et al., “Photonic RF and microwave filters based on 49GHz and 200GHz Kerr microcombs”, Optics Communications, vol. 465, Article: 125563 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Y. Sun et al., “Quantifying the Accuracy of Microcomb-based Photonic RF Transversal Signal Processors”, IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics vol. 29 no. 6, pp. 1-17, 7500317 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Li et al., “Processing accuracy of microcomb-based microwave photonic signal processors for different input signal waveforms”, Photonics 10, 10111283 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, et al., “Feedback control in micro-comb-based microwave photonic transversal filter systems”, IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics Vol. 30 (5) 2900117 (2024).

- W. Han et al., “Dual-polarization RF Channelizer Based on Microcombs”, Optics Express 32, No. 7, 11281-11295 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu et al., “Advances in Soliton Crystals Microcombs”, Photonics Vol. 11, 1164 (2024). [CrossRef]

- C. Mazoukh et al., “Genetic algorithm-enhanced microcomb state generation”, Nature Communications Physics Vol. 7, Article: 81 (2024). [CrossRef]

- S. Chen et al., “High-bit-efficiency TOPS optical tensor convolutional accelerator using micro-combs”, Laser & Photonics Reviews 19 2401975 (2025).

- W. Han et al., “TOPS-speed complex-valued convolutional accelerator for feature extraction and inference”, Nature Communications 16 292 (2025).

- L. di Lauro et al., “Optimization Methods for Integrated and Programmable Photonics in Next-Generation Classical and Quantum Smart Communication and Signal Processing”, Advances in Optics and Photonics Vol. 17 (3) 526 - 622 (2025).

- B. Corcoran et al., “Optical microcombs for ultrahigh-bandwidth communications”, Nature Photonics Volume 19 (5) 451 - 462 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Song, Y., Chen, S. et al. Integrated platforms and techniques for photonic neural networks. npj Nanophotonics 2, 40 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44310-025-00088-z. [CrossRef]

- M.Peccianti, M.Ferrera, D.Duchesne, L.Razzari, R.Morandotti, B.E Little, S.Chu and D.J Moss, “Subpicosecond optical pulse compression via an integrated nonlinear chirper”, Optics Express 18, (8) 7625-7633 (2010).

- M. Ferrera, L. Razzari, D. Duchesne, R. Morandotti, Z. Yang, M. Liscidini, J. E. Sipe, S. Chu, B. E. Little, and D. J. Moss, “Low-power continuous-wave nonlinear optics in doped silica glass integrated waveguide structures,” Nature Photonics, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 737–740, 2008/12//, 2008. [CrossRef]

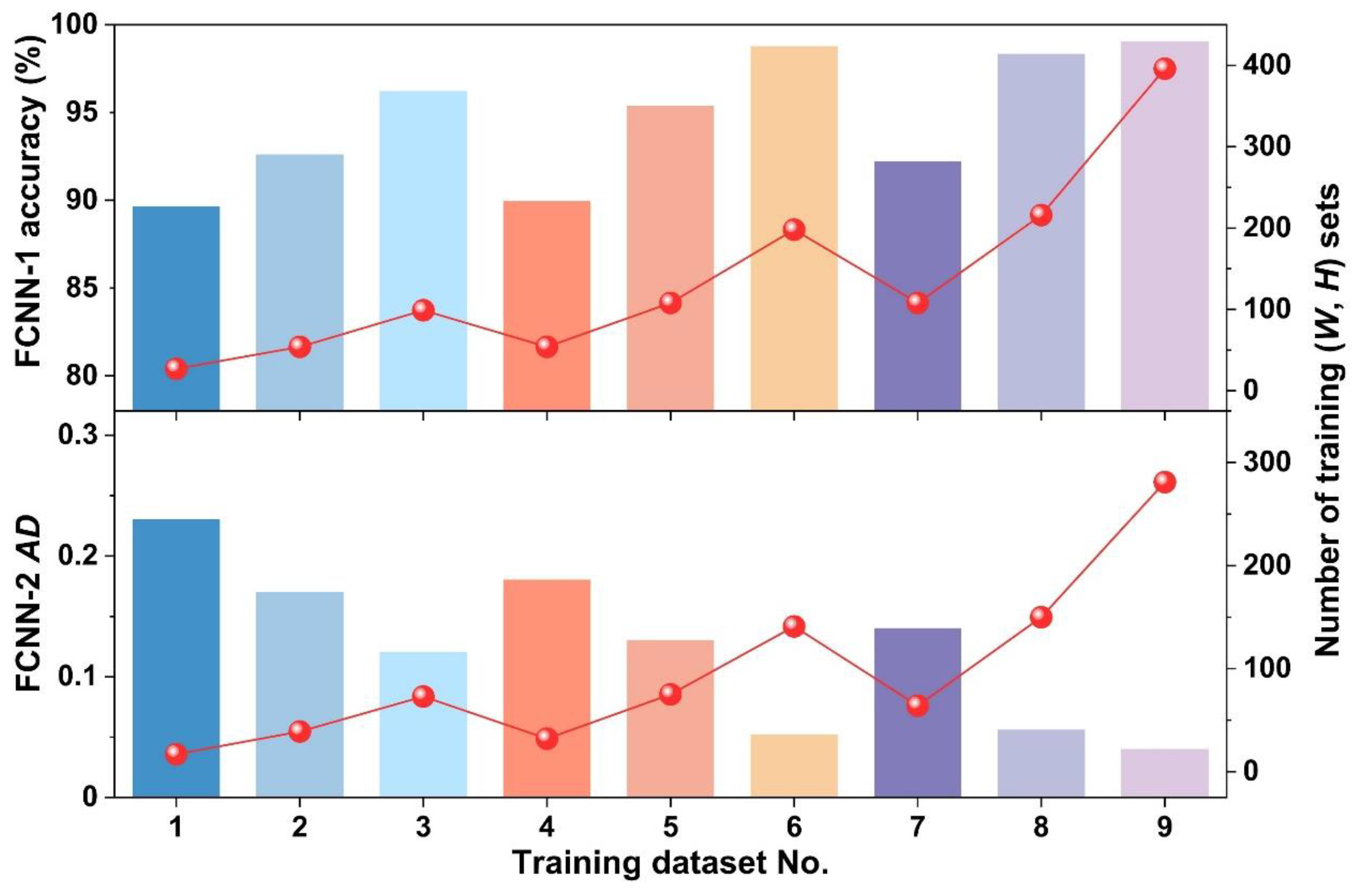

| Dataset No. | ΔH (nm)a | ΔW (nm)a | Number of training sets for FCNN-1 | Number of training sets for FCNN-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80 | 80 | 27 | 17 |

| 2 | 40 | 80 | 54 | 39 |

| 3 | 20 | 80 | 99 | 73 |

| 4 | 80 | 40 | 54 | 32 |

| 5 | 40 | 40 | 108 | 75 |

| 6 | 20 | 40 | 198 | 141 |

| 7 | 80 | 20 | 108 | 64 |

| 8 | 40 | 20 | 216 | 150 |

| 9 | 20 | 20 | 396 | 281 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).